Submitted:

29 July 2024

Posted:

01 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Superquadrics

2.2. Small-Angle Scattering

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Models

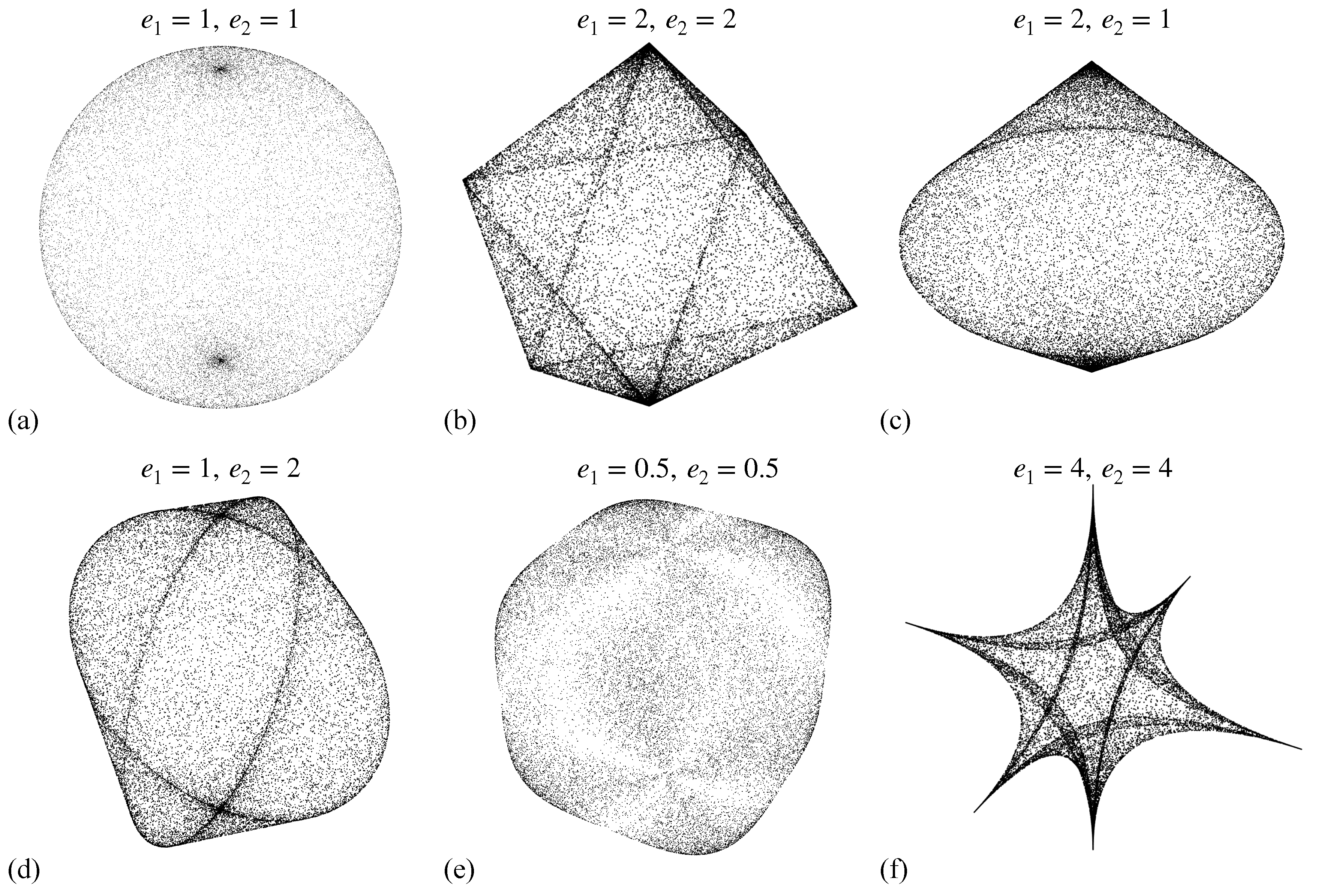

- Ellipsoid: When both and equal 1, the superquadric takes on the form of an ellipsoid. This shape is characterized by its uniform curvature and is commonly used to model objects with spherical or ellipsoidal characteristics.

- Octahedron: As and increase beyond 1, the superquadric becomes more box-like with sharper edges. This configuration resembles an octahedron and is suitable for representing objects with angular features.

- Elliptic bicone: When is greater than 1 and equals 1, the superquadric exhibits the appearance of two cones sharing a common elliptical base. This shape is well-suited for modeling objects with conical attributes

- Elliptic pillow: Conversely, when equals 1 and is greater than 1, the superquadric takes on a form reminiscent of four half-regions with common elliptical bases. This configuration is useful for objects that possess pillow-like structures.

- Near-cube: When both and are between 0 and 1, the superquadric approaches a cube-like shape. It is an ideal choice for representing objects that are nearly cubic in nature.

- Star: Finally, by setting both and greater than 2, the superquadric exhibits concave features resembling a star-like shape. This configuration is valuable for modeling objects with intricate concavities.

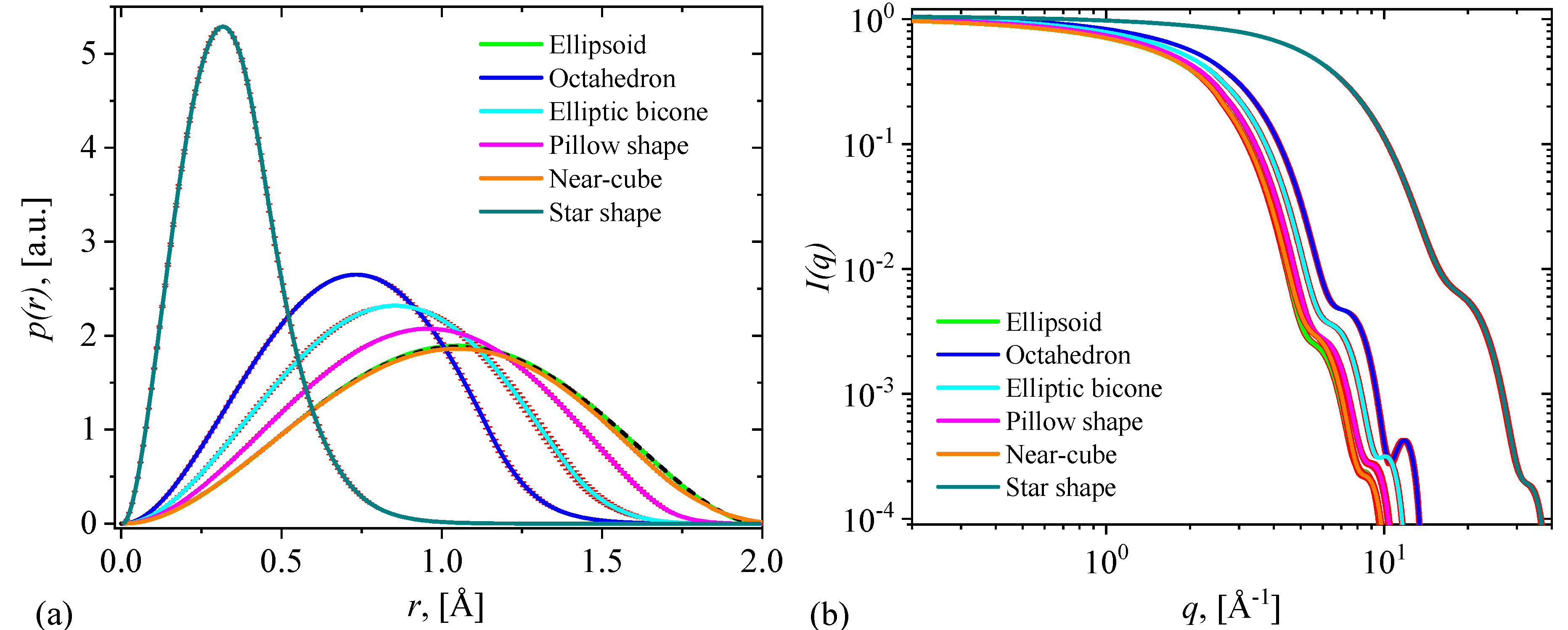

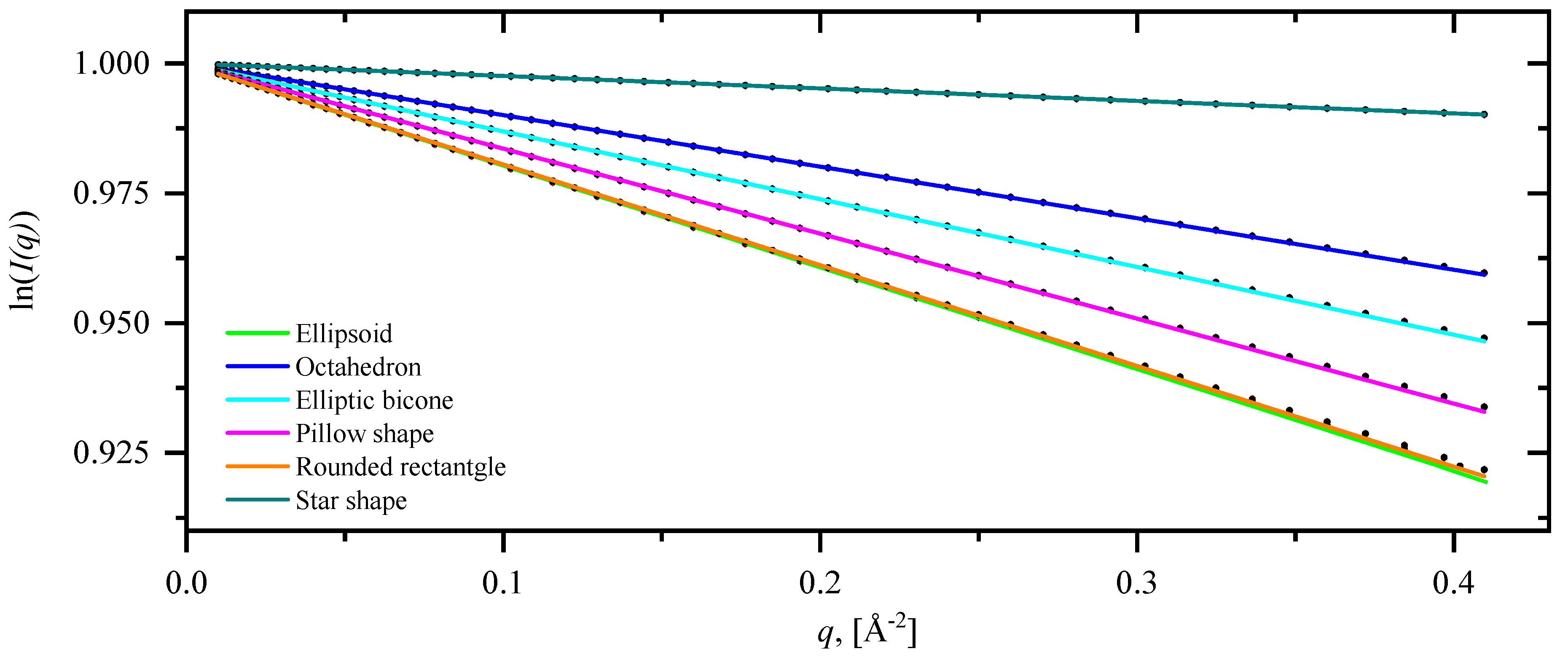

3.2. Pair-distance distribution functions and scattering intensities

3.3. Application: Analysis of Small-angle X-ray Scattering Data from a Chimeric Protein complex

4. Conclusions

Declarations

References

- Vaskevicius, N.; Birk, A. Revisiting Superquadric Fitting: A Numerically Stable Formulation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 41, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, G.; Pattacini, U.; Natale, L. A grasping approach based on superquadric models. Proc. - IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom, 2017, pp. 1579–1586. [CrossRef]

- Torres-DÃ az, I.; Hendley, R.S.; Mishra, A.; Yeh, A.J.; Bevan, M.A. Hard superellipse phases: particle shape anisotropy & curvature. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Burugadda, P.; Likhith Kumar Reddy, S.; Govardhan Kumar, S.; Katakam, G.; Prashanth Kumar, Y. Parametrization of 3D shapes using Superquadrics. Proc. - IEEE Int. Conf. Smart Electron. Commun., 2020, pp. 620–624.

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, S. GPU-based Parallel Algorithm for Super-Quadric Discrete Element Method and Its Applications for Non-Spherical Granular Flows. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2021, 151, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Introduction. In Small-Angle Scattering (Neutrons, X-Rays, Light) from Complex Systems: Fractal and Multifractal Models for Interpretation of Experimental Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. , X-Rays, Light) from Complex Systems: Fractal and Multifractal Models for Interpretation of Experimental Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 33–63. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-26612-7_3.Technique. In Small-Angle Scattering (Neutrons, X-Rays, Light) from Complex Systems: Fractal and Multifractal Models for Interpretation of Experimental Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamley, I.W. Small-Angle Scattering: Theory, Instrumentation, Data, and Applications, 1st ed.; Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021.

- Melnichenko, Y.B.; Wignall, G.D. Small-angle neutron scattering in materials science: Recent practical applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102, 021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Structural Properties of Molecular Sierpinski Triangle Fractals. Nanomaterials 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Small-Angle Scattering from Fractional Brownian Surfaces. Symmetry 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, D.A.; Trewhella, J. Small-angle scattering for structural biologyâExpanding the frontier while avoiding the pitfalls. Protein Sci. 2010, 19, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svergun, D.I.; Koch, M.H.J. Small-angle scattering studies of biological macromolecules in solution. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2003, 66, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M.; Slyamov, A. Structural characterization of chaos game fractals using small-angle scattering analysis. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Small-Angle Scattering and Multifractal Analysis of DNA Sequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. α-SAS: an integrative approach for structural modeling of biological macromolecules in solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 2022, 78, 1046–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Fractal Analysis of DNA Sequences Using Frequency Chaos Game Representation and Small-Angle Scattering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Integrating machine learning with -SAS for enhanced structural analysis in small-angle scattering: applications in biological and artificial macromolecular complexess. Eur. Phys. J. E 2024, 47, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, G.; Bergmann, A.; Glatter, O. Evaluation of small-angle scattering data of charged particles using the generalized indirect Fourier transformation technique. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9733–9740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Structural Properties of Janus Particles with Nano- and Mesoscale Anisotropy. Nanomaterials 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Structural characterization of Janus nanoparticles with tunable geometric and chemical asymmetries by small-angle scattering. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, A.Y.; Anitas, E.M.; Osipov, V.A. Dense random packing with a power-law size distribution: The structure factor, massâradius relation, and pair distribution function. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 044114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, A.Y.; Anitas, E.M.; Vladimirov, A.A.; Osipov, V.A. Dense random packing of disks with a power-law size distribution in thermodynamic limit. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 160, 024107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M.; Slyamov, A.M. Emergence of Surface Fractals in Cellular Automata. Ann. Phys. 2018, 530, 1800187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M.; Slyamov, A. Structural Properties of Additive Nano/Microcellular Automata. Ann. Phys. 2018, 530, 1800004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Small-angle scattering from fat fractals. Eur. Phys. J. B 2014, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Fractals: Definitions and Generation Methods. In Small-Angle Scattering (Neutrons, X-Rays, Light) from Complex Systems: Fractal and Multifractal Models for Interpretation of Experimental Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Small-Angle Scattering from Fractals. In Small-Angle Scattering (Neutrons, X-Rays, Light) from Complex Systems: Fractal and Multifractal Models for Interpretation of Experimental Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 65–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Conclusions and Outlook. In Small-Angle Scattering (Neutrons, X-Rays, Light) from Complex Systems: Fractal and Multifractal Models for Interpretation of Experimental Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitas, E.M. Small-Angle Scattering from Fractals: Differentiating between Various Types of Structures. Symmetry 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, J.S. Analysis of small-angle scattering data from colloids and polymer solutions: modeling and least-squares fitting. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 70, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernetti, M.; Bussi, G. Comparing state of- the-art approaches to back-calculate saxs spectra from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. Eur. Phys. J. B 2021, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresen, D.; Qdemat, A.; Ulusoy, S.; Mees, F.; Zákutná, D.; Wetterskog, E.; Kentzinger, E.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Disch, S. Neither Sphere nor CubeâAnalyzing the Particle Shape Using Small-Angle Scattering and the Superball Model. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 23356–23363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielis, J. A generic geometric transformation that unifies a wide range of natural and abstract shapes. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fougerolle, Y.D.; Gribok, A.; Foufou, S.; Truchetet, F.; Abidi, M.A. Rational supershapes for surface reconstruction. Eighth International Conference on Quality Control by Artificial Vision; Fofi, D.; Meriaudeau, F., Eds. SPIE, 2007, Vol. 6356, p. 63560M.

- Sudarev, V.; Gette, M.; Bazhenov, S.; Tilinova, O.; Zinovev, E.; Manukhov, I.; Kuklin, A.; Ryzhykau, Y.; Vlasov, A. Ferritin-based fusion protein shows octameric deadlock state of self-assembly. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 690, 149276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, A. Superquadrics and Angle-Preserving Transformations. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 1981, 1, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzopoulos, D.; Metaxas, D. Dynamic 3D models with local and global deformations: deformable superquadrics. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1991, 13, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Kambhamettu, C. Extending Superquadrics with Exponent Functions: Modeling and Reconstruction. Graph. Models 2001, 63, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Marmysh, D.; Ji, S. Construction of irregular particles with superquadric equation in DEM. Theor. App. Mech. Lett. 2020, 10, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ji, S. A unified level set method for simulating mixed granular flows involving multiple non-spherical DEM models in complex structures. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 393, 114802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosey, C.A.; Tainer, J.A. Evolving SAXS versatility: solution X-ray scattering for macromolecular architecture, functional landscapes, and integrative structural biology. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 58, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatter, O.; May, R. Small-angle techniques. Int. Tabl. Cryst. 2006, C, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bracewell, R.N. The Fourier Transform & Its Applications, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill, Singapore, 1999.

- Rayleigh, L. On the Diffraction of Light by Spheres of Small Relative Index. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A-Contain. Pap. Math. Phys. 1914, 90, 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Glatter, O. The interpretation of real-space information from small-angle scattering experiments. J. Appl. Cryst. 1979, 12, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratky, O. Die Abhängigkeit der Röntgen-Kleinwinkelstreuung von Größe und Form der kolloiden Teilchen in verdünnten Systemen. Monatsh. Chem. 1947, 76, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinier, A.; Fournet, G. SMall-angle scattering of X-rays; John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA, 1955.

- Kohlbrecher, J.; Breßler, I. Updates in SASfit for fitting analytical expressions and numerical models to small-angle scattering patterns. J. Appl. Cryst. 2022, 55, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, A.Y.; Anitas, E.M.; Osipov, V.A.; Kuklin, A.I. The structure of deterministic mass and surface fractals: theory and methods of analyzing small-angle scattering data. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 12748–12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammouda, B. A new Guinier–Porod model. J. Appl. Cryst. 2010, 43, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, J.S.; Posselt, D.; Mortensen, K. Analytical treatment of the resolution function for small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 1990, 23, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W.S. Robust Locally Weighted Regression and Smoothing Scatterplots. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikhney, A.G.; Borges, C.R.; Molodenskiy, D.S.; Jeffries, C.M.; Svergun, D.I. SASBDB: Towards an automatically curated and validated repository for biological scattering data. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar]

| Ellipsoid | Octahedron | Elliptic bicone | Elliptic pillow | Near-cube | Star | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.03 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 0.32 | |

| -0.19 | -0.10 | -0.13 | -0.16 | -0.19 | -0.02 | |

| 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).