Submitted:

31 July 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. What is TMB?

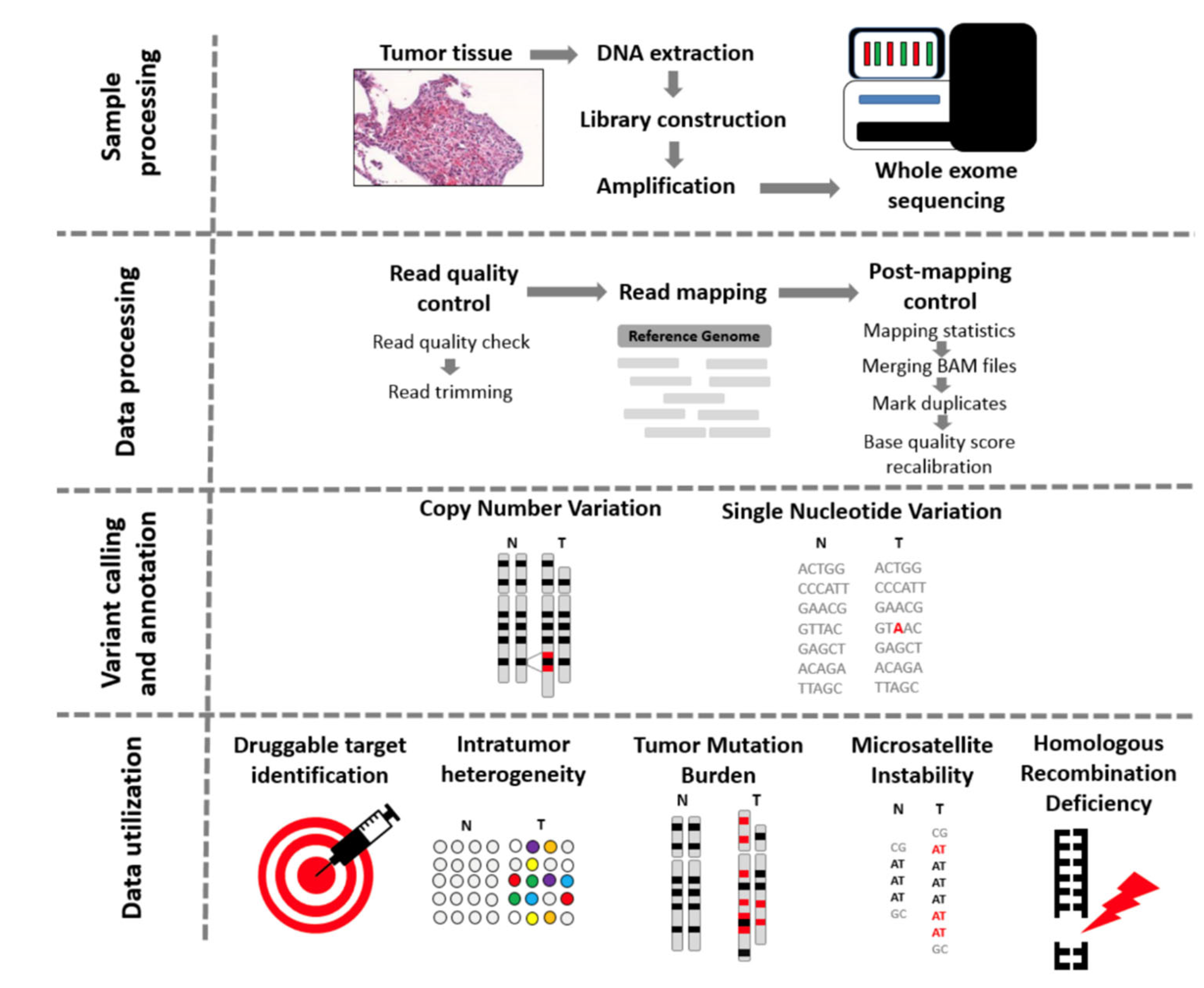

3. Testing Method: WES

4. Corelation between TMB and Immuntherapy

5. The interpretation and reporting the TMB value

- Tumour purity: this represents the overall percentage of cancerous cell within a tumour sample. This measurement is analyst-dependent and also can lead to errors due to the fact that the used sample may not represent the tumour's region which will be analysed.

- Library construction and sequencing: this is represented by DNA fragments with a defined length which will be analysed using various bioinformatics programs.

- The pipeline used to call mutations: represents the algorithm used to remove germline variants. This is a vital step in the identification of different somatic mutations which are responsible for producing tumour neo-antigens. These antigens will be eventually recognised as non-self by the immune system.

- The capacity to extrapolate TMB values from the restricted genomic space sampled by gene panels: this step is based on the in silico analysis performed on samples to determine the concordance between WE- based TMB and panel-based TMB [1].

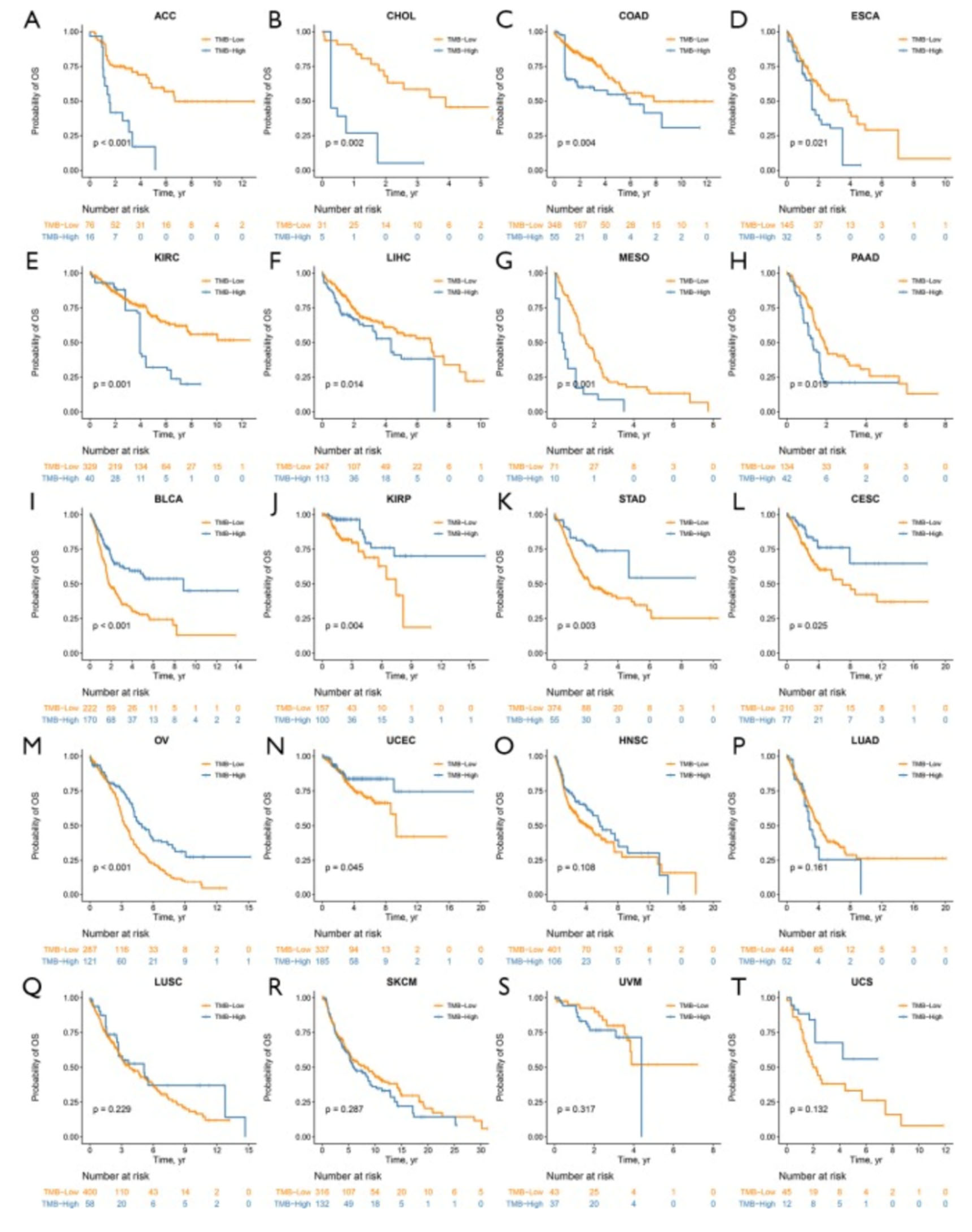

6. Can We Use TMB as a Predictive Biomarker?

7. Next we will evaluate the association between TMB and different types of cancers: melanoma+ lung vs. prostate+ breast

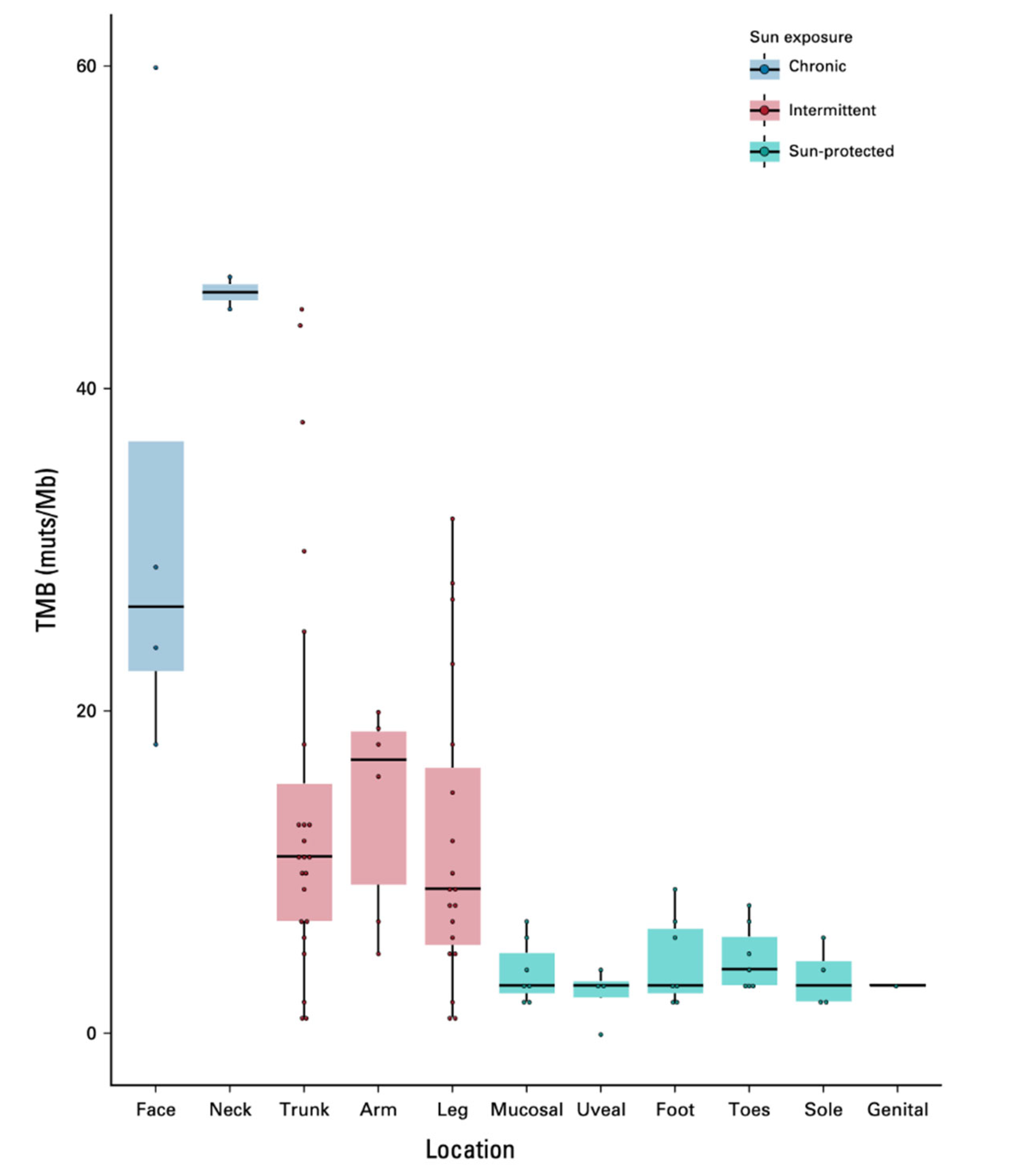

7.1. Melanoma and TMB evaluation

7.2. Lung cancer and TMB evaluation

7.3. Prostate +breast cancers and TMB evaluation

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

References

- Addeo, Alfredo et al. “TMB or not TMB as a biomarker: That is the question.” Critical reviews in oncology/hematology vol. 163 (2021): 103374. [CrossRef]

- Büttner, Reinhard et al. “Implementing TMB measurement in clinical practice: considerations on assay requirements.” ESMO open vol. 4,1 e000442. 24 Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA announces approval, CMS proposes coverage of first breakthrough-designated test to detect extensive number of cancer biomarkers. 2017. Available from: https://www.fda. gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm587273.htm.

- FDA. FDA unveils a streamlined path for the authorization of tumor profiling tests alongside its latest product action. 2018. Available from: https://www. fda. gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm585347.htm.

- Bartha Á, Győrffy B. Comprehensive Outline of Whole Exome Sequencing Data Analysis Tools Available in Clinical Oncology. Cancers. 2019; 11(11):1725. [CrossRef]

- Schaub, M.A.; Boyle, A.P.; Kundaje, A.; Batzoglou, S.; Snyder, M. Linking disease associations with regulatory information in the human genome. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minde, D.P.; Anvarian, Z.; Rudiger, S.G.; Maurice, M.M. Messing up disorder: How do missense mutations in the tumor suppressor protein APC lead to cancer? Mol. Cancer 2011, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnarra, J.R.; Tory, K.; Weng, Y.; Schmidt, L.; Wei, M.H.; Li, H.; Latif, F.; Liu, S.; Chen, F.; Duh, F.M.; et al. Mutations of the VHL tumour suppressor gene in renal carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 1994, 7, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, H.; McCabe, N.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.N.; Johnson, D.A.; Richardson, T.B.; Santarosa, M.; Dillon, K.J.; Hickson, I.; Knights, C.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921.

- Torgovnick, A.; Schumacher, B. DNA repair mechanisms in cancer development and therapy. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 157.

- Luchini, C.; Bibeau, F.; Ligtenberg, M.J.L.; Singh, N.; Nottegar, A.; Bosse, T.; Miller, R.; Riaz, N.; Douillard, J.Y.; Andre, F.; et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: A systematic review-based approach. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med Oncol. 2019.

- Pongor, L.; Kormos, M.; Hatzis, C.; Pusztai, L.; Szabo, A.; Gyorffy, B. A genome-wide approach to link genotype to clinical outcome by utilizing next generation sequencing and gene chip data of 6697 breast cancer patients. Genome Med. 2015, 7, 104.

- Hargadon, K.M.; Johnson, C.E.; Williams, C.J. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 62, 29–39.

- Chalmers, Zachary R et al. “Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden.” Genome medicine vol. 9,1 34. 19 Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- FoCR. Friends of Cancer Research Announces Launch of Phase II TMB Harmonization Project; FoCR: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Goodman, Aaron M et al. “Tumor Mutational Burden as an Independent Predictor of Response to Immunotherapy in Diverse Cancers.” Molecular cancer therapeutics vol. 16,11 (2017): 2598-2608. [CrossRef]

- Wu HX, Wang ZX, Zhao Q, Chen DL, He MM, Yang LP, Wang YN, Jin Y, Ren C, Luo HY, Wang ZQ, Wang F. Tumor mutational and indel burden: a systematic pan-cancer evaluation as prognostic biomarkers. Ann Transl Med. 2019 Nov;7(22):640. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dousset, Léa et al. “Positive Association Between Location of Melanoma, Ultraviolet Signature, Tumor Mutational Burden, and Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy.” JCO precision oncology vol. 5 PO.21.00084. 16 Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bravaccini S, Bronte G, Ulivi P. TMB in NSCLC: A Broken Dream? Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 18;22(12):6536. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wankhede D, Grover S, Hofman P. The prognostic value of TMB in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023 Aug 31;15:17588359231195199. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greillier, Laurent et al. “The clinical utility of tumor mutational burden in non-small cell lung cancer.” Translational lung cancer research vol. 7,6 (2018): 639-646. [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Cs ̋oszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833.

- Hellmann, M.D.; Paz-Ares, L.; Bernabe Caro, R.; Zurawski, B.; Kim, S.W.; Carcereny Costa, E.; Park, K.; Alexandru, A.; Lupinacci, L.; de la Mora Jimenez, E.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2020–2031.

- Young Kwang Chae, Andrew A. Davis, Sarita Agte, Alan Pan, Nicholas I. Simon, Wade T. Iams, Marcelo R. Cruz, Keerthi Tamragouri, Kyunghoon Rhee, Nisha Mohindra, Victoria Villaflor, Wungki Park, Gilberto Lopes, Francis J. Giles, Clinical Implications of Circulating Tumor DNA Tumor Mutational Burden (ctDNA TMB) in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, The Oncologist, Volume 24, Issue 6, June 2019, Pages 820–828. [CrossRef]

- Mei, P., Freitag, C.E., Wei, L. et al. High tumor mutation burden is associated with DNA damage repair gene mutation in breast carcinomas. Diagn Pathol 15, 50 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Nanda R, Chow LQ, Dees EC, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced triple-negative breast Cancer: phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2460–7.

- Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2108–21.

- Wang L, Pan S, Zhu B, Yu Z, Wang W. Comprehensive analysis of tumour mutational burden and its clinical significance in prostate cancer. BMC Urol. 2021 Feb 25;21(1):29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu Y, Ye D. Chinese Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (2019 Update). Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:2127–40.

- Graf RP, Fisher V, Weberpals J, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors vs. Chemotherapy by Tumor Mutational Burden in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e225394. [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis ES, Piulats JM, Gross-Goupil M, et al. Pembrolizumab for treatment-refractory metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: multicohort, open-label phase II KEYNOTE-199 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38 (5):395-405. [CrossRef]

- Donisi C, Pretta A, Pusceddu V, Ziranu P, Lai E, Puzzoni M, Mariani S, Massa E, Madeddu C, Scartozzi M. Immunotherapy and Cancer: The Multi-Omics Perspective. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(6):3563. [CrossRef]

- Ma X, Zhang Y, Wang S, Yu J. Predictive value of tumor mutation burden (TMB) with targeted next-generation sequencing in immunocheckpoint inhibitors for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;12(2):584-594. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berland L, Heeke S, Humbert O, et al. Current views on tumor mutational burden in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Thorac Dis. 2019; 11(Suppl 1): S71-S80.

- Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015; 348: 124-128.

- Klempner SJ, Fabrizio D, Bane S, et al. Tumor Mutational Burden as a Predictive Biomarker for Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Review of Current Evidence. Oncologist. 2020; 25(1): e147-e159.

- Eckardt, J., Schroeder, C., Martus, P. et al. TMB and BRAF mutation status are independent predictive factors in high-risk melanoma patients with adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 149, 833–840 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pedro Barata, Reagan Barnett, Albert Jang et al. Assessment of blood-based tumor mutational burden on clinical outcomes in advanced breast and prostate cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 28 May 2024, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. 28 May. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).