Submitted:

30 July 2024

Posted:

31 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

3. Serum/Plasma Biomarkers in IPF

4. miRNAs, Biogenesis, and Mechanism of Action

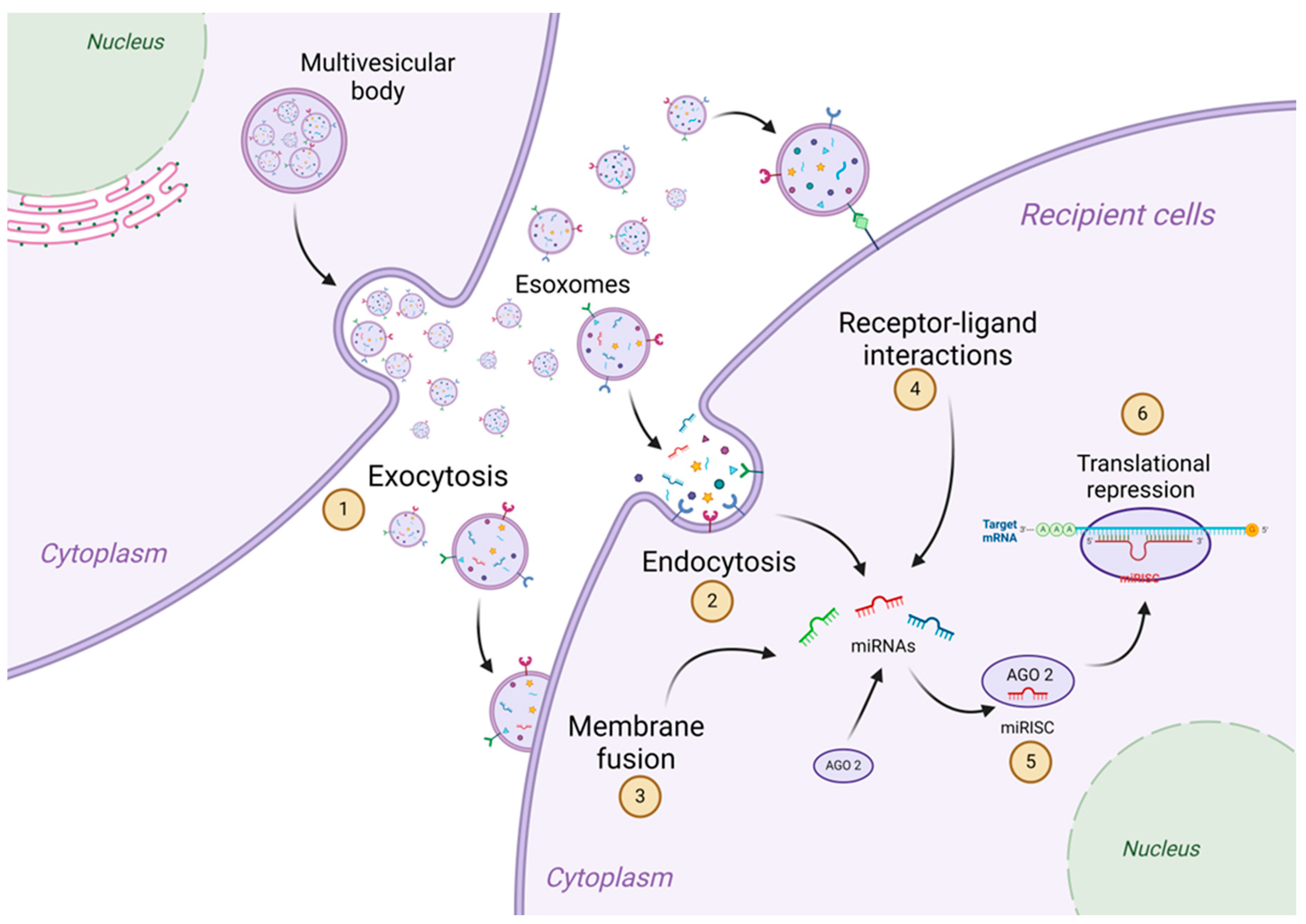

5. Circulation of Exosomes and Their Mechanism of Action

6. Upregulated Serum/Plasma miRNAs in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- miR-21

- miR-155

- miR-590-3p

- miR-199a-5p and miR-200c

7. Downregulated Serum/Plasma miRNAs in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- Let-7a

- and Let-7d.

- miR-16

- miR-25-3p and miR-142-5p

- miR-101-3p

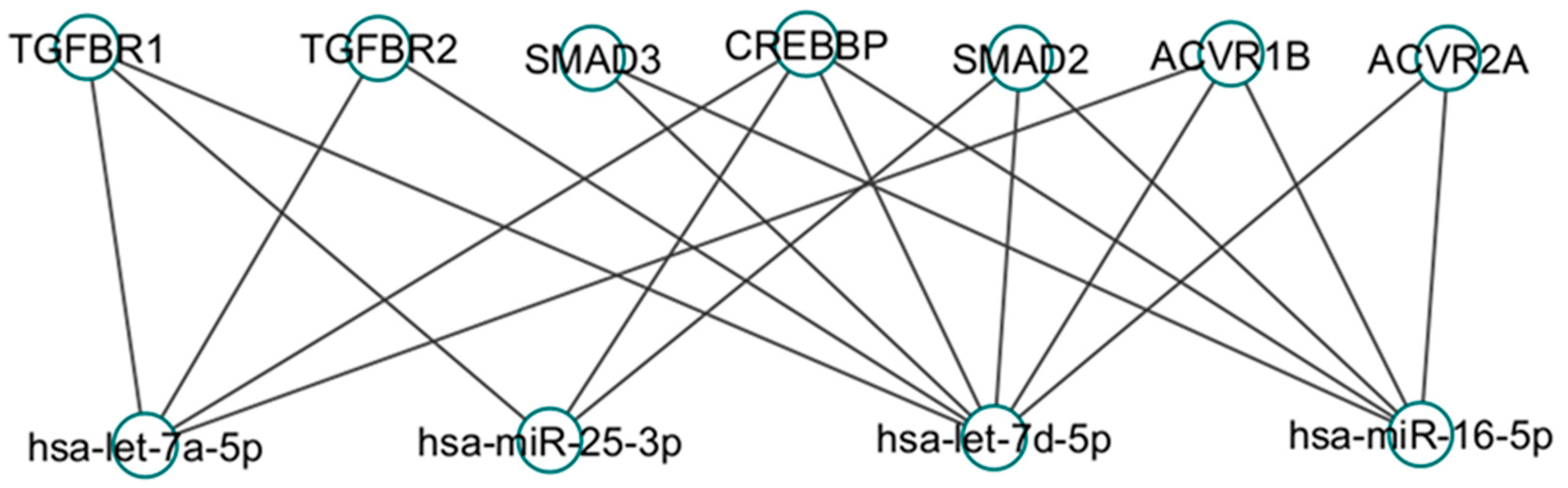

8. Common Targets in TGF beta-1 Signaling Pathways

9. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nho, R.S. Alteration of Aging-Dependent MicroRNAs in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Drug Dev Res 2015, 76, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guler, S.A.; Corte, T.J. Interstitial Lung Disease in 2020: A History of Progress. Clin Chest Med 2021, 42, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarelli, A.V.; Tonelli, R.; Marchioni, A.; Bruzzi, G.; Gozzi, F.; Andrisani, D.; Castaniere, I.; Manicardi, L.; Moretti, A.; Tabbi, L.; et al. Fibrotic Idiopathic Interstitial Lung Disease: The Molecular and Cellular Key Players. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A. Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006, 3, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Velikoff, M.; Canalis, E.; Horowitz, J.C.; Kim, K.K. Activated alveolar epithelial cells initiate fibrosis through autocrine and paracrine secretion of connective tissue growth factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2014, 306, L786–L796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniades, H.N.; Bravo, M.A.; Avila, R.E.; Galanopoulos, T.; Neville-Golden, J.; Maxwell, M.; Selman, M. Platelet-derived growth factor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 1990, 86, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A. The leading role of epithelial cells in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Signal 2020, 66, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, M.; King, T.E.; Pardo, A.; American Thoracic, S.; European Respiratory, S.; American College of Chest, P. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med 2001, 134, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.J.; Collard, H.R.; Pardo, A.; Raghu, G.; Richeldi, L.; Selman, M.; Swigris, J.J.; Taniguchi, H.; Wells, A.U. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A.; Selman, M. The Interplay of the Genetic Architecture, Aging, and Environmental Factors in the Pathogenesis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2021, 64, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishaba, T. Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, K.; Bailey, N.W.; Yang, J.; Steel, M.P.; Groshong, S.; Kervitsky, D.; Brown, K.K.; Schwarz, M.I.; Schwartz, D.A. Molecular phenotypes distinguish patients with relatively stable from progressive idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). PLoS One 2009, 4, e5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas, I.O.; Richards, T.J.; Konishi, K.; Zhang, Y.; Gibson, K.; Lokshin, A.E.; Lindell, K.O.; Cisneros, J.; Macdonald, S.D.; Pardo, A.; et al. MMP1 and MMP7 as potential peripheral blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med 2008, 5, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, K.E.; King, T.E., Jr.; Kuroki, Y.; Bucher-Bartelson, B.; Hunninghake, G.W.; Newman, L.S.; Nagae, H.; Mason, R.J. Serum surfactant proteins-A and -D as biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2002, 19, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamai, K.; Iwamoto, H.; Ishikawa, N.; Horimasu, Y.; Masuda, T.; Miyamoto, S.; Nakashima, T.; Ohshimo, S.; Fujitaka, K.; Hamada, H.; et al. Comparative Study of Circulating MMP-7, CCL18, KL-6, SP-A, and SP-D as Disease Markers of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Dis Markers 2016, 2016, 4759040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eduardo, M.; Ivette, B.R.; Gabriela, D.P.; Veronica, M.A.; Victor, R. Evaluation of Renin and Soluble (Pro)renin Receptor in Patients with IPF. A Comparison with Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. Lung 2019, 197, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Ashurst, J.L.; Bradley, A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res 2004, 14, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Han, J.; Yeom, K.H.; Lee, S.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, V.N. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J 2004, 23, 4051–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jeon, K.; Lee, J.T.; Kim, S.; Kim, V.N. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J 2002, 21, 4663–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Ahn, C.; Han, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, J.; Yim, J.; Lee, J.; Provost, P.; Radmark, O.; Kim, S.; et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature 2003, 425, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, R.I.; Yan, K.P.; Amuthan, G.; Chendrimada, T.; Doratotaj, B.; Cooch, N.; Shiekhattar, R. The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 2004, 432, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohnsack, M.T.; Czaplinski, K.; Gorlich, D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. RNA 2004, 10, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, R.; Qin, Y.; Macara, I.G.; Cullen, B.R. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev 2003, 17, 3011–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, R.I.; Chendrimada, T.P.; Cooch, N.; Shiekhattar, R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell 2005, 123, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takimoto, K.; Wakiyama, M.; Yokoyama, S. Mammalian GW182 contains multiple Argonaute-binding sites and functions in microRNA-mediated translational repression. RNA 2009, 15, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabian, M.R.; Sonenberg, N. The mechanics of miRNA-mediated gene silencing: a look under the hood of miRISC. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012, 19, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chendrimada, T.P.; Gregory, R.I.; Kumaraswamy, E.; Norman, J.; Cooch, N.; Nishikura, K.; Shiekhattar, R. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature 2005, 436, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, A.D.; Jaskiewicz, L.; Zhang, H.; Laine, S.; Sack, R.; Gatignol, A.; Filipowicz, W. TRBP, a regulator of cellular PKR and HIV-1 virus expression, interacts with Dicer and functions in RNA silencing. EMBO Rep 2005, 6, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomari, Y.; Matranga, C.; Haley, B.; Martinez, N.; Zamore, P.D. A protein sensor for siRNA asymmetry. Science 2004, 306, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eulalio, A.; Huntzinger, E.; Izaurralde, E. Getting to the root of miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Cell 2008, 132, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevillet, J.R.; Kang, Q.; Ruf, I.K.; Briggs, H.A.; Vojtech, L.N.; Hughes, S.M.; Cheng, H.H.; Arroyo, J.D.; Meredith, E.K.; Gallichotte, E.N.; et al. Quantitative and stoichiometric analysis of the microRNA content of exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 14888–14893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasser, C.; Alikhani, V.S.; Ekstrom, K.; Eldh, M.; Paredes, P.T.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Gabrielsson, S.; Lotvall, J.; Valadi, H. Human saliva, plasma and breast milk exosomes contain RNA: uptake by macrophages. J Transl Med 2011, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraszti, R.A.; Didiot, M.C.; Sapp, E.; Leszyk, J.; Shaffer, S.A.; Rockwell, H.E.; Gao, F.; Narain, N.R.; DiFiglia, M.; Kiebish, M.A.; et al. High-resolution proteomic and lipidomic analysis of exosomes and microvesicles from different cell sources. J Extracell Vesicles 2016, 5, 32570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thery, C.; Zitvogel, L.; Amigorena, S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol 2002, 2, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, P.G.; Futter, C.E. Multivesicular bodies: co-ordinated progression to maturity. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2008, 20, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.D.; Donaldson, J.G. Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuffers, S.; Sem Wegner, C.; Stenmark, H.; Brech, A. Multivesicular endosome biogenesis in the absence of ESCRTs. Traffic 2009, 10, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenberg, J.; van der Goot, F.G. Mechanisms of pathogen entry through the endosomal compartments. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006, 7, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.L.; Urbe, S. The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guduric-Fuchs, J.; O’Connor, A.; Camp, B.; O’Neill, C.L.; Medina, R.J.; Simpson, D.A. Selective extracellular vesicle-mediated export of an overlapping set of microRNAs from multiple cell types. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zernecke, A.; Bidzhekov, K.; Noels, H.; Shagdarsuren, E.; Gan, L.; Denecke, B.; Hristov, M.; Koppel, T.; Jahantigh, M.N.; Lutgens, E.; et al. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal 2009, 2, ra81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, N.; Iguchi, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takeshita, F.; Matsuki, Y.; Ochiya, T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 17442–17452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathivanan, S.; Lim, J.W.; Tauro, B.J.; Ji, H.; Moritz, R.L.; Simpson, R.J. Proteomics analysis of A33 immunoaffinity-purified exosomes released from the human colon tumor cell line LIM1215 reveals a tissue-specific protein signature. Mol Cell Proteomics 2010, 9, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhao, G.Q.; Chen, T.F.; Chang, J.X.; Wang, H.Q.; Chen, S.S.; Zhang, G.J. Serum miR-21 and miR-155 expression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Asthma 2013, 50, 960–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makiguchi, T.; Yamada, M.; Yoshioka, Y.; Sugiura, H.; Koarai, A.; Chiba, S.; Fujino, N.; Tojo, Y.; Ota, C.; Kubo, H.; et al. Serum extracellular vesicular miR-21-5p is a predictor of the prognosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2016, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, H.; Chu, H.; Chang, J.; Zang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Du, Y.; et al. Expression analysis of serum microRNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Mol Med 2014, 33, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Guan, S. A novel molecular mechanism of microRNA-21 inducing pulmonary fibrosis and human pulmonary fibroblast extracellular matrix through transforming growth factor beta1-mediated SMADs activation. J Cell Biochem 2018, 119, 7834–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottier, N.; Maurin, T.; Chevalier, B.; Puissegur, M.P.; Lebrigand, K.; Robbe-Sermesant, K.; Bertero, T.; Lino Cardenas, C.L.; Courcot, E.; Rios, G.; et al. Identification of keratinocyte growth factor as a target of microRNA-155 in lung fibroblasts: implication in epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, D.; Yao, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, S.; Gao, X.; Cai, W.; Mao, N.; Jin, F.; Li, Y.; et al. Inhibition of miR-155-5p Exerts Anti-Fibrotic Effects in Silicotic Mice by Regulating Meprin alpha. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020, 19, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Kang, Y.; Xue, S.; Zou, J.; Xu, J.; Tang, D.; Qin, H. In vivo therapeutic success of MicroRNA-155 antagomir in a mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin. Korean J Intern Med 2021, 36, S160–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christmann, R.B.; Wooten, A.; Sampaio-Barros, P.; Borges, C.L.; Carvalho, C.R.; Kairalla, R.A.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.; Ziemek, J.; Mei, Y.; Goummih, S.; et al. miR-155 in the progression of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artlett, C.M.; Sassi-Gaha, S.; Hope, J.L.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A.; Katsikis, P.D. Mir-155 is overexpressed in systemic sclerosis fibroblasts and is required for NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated collagen synthesis during fibrosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2017, 19, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Z.; Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Bai, C.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, P.K. MiRNA-155-5p inhibits epithelium-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by targeting GSK-3beta during radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Arch Biochem Biophys 2021, 697, 108699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirol, H.; Toylu, A.; Ogus, A.C.; Cilli, A.; Ozbudak, O.; Clark, O.A.; Ozdemir, T. Alterations in plasma miR-21, miR-590, miR-192 and miR-215 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their clinical importance. Mol Biol Rep 2022, 49, 2237–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Pan, J.; Wen, L.; Gong, B.; Li, J.; Gao, H.; Tan, W.; Liang, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. MiR-590-3p regulates proliferation, migration and collagen synthesis of cardiac fibroblast by targeting ZEB1. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.I.; Khaled, G.M.; Amleh, A. Functional role and epithelial to mesenchymal transition of the miR-590-3p/MDM2 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A.; Cabrera, S.; Maldonado, M.; Selman, M. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2016, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Friggeri, A.; Yang, Y.; Milosevic, J.; Ding, Q.; Thannickal, V.J.; Kaminski, N.; Abraham, E. miR-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. J Exp Med 2010, 207, 1589–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, H.; Abdollah, S.; Qiu, Y.; Cai, J.; Xu, Y.Y.; Grinnell, B.W.; Richardson, M.A.; Topper, J.N.; Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; Wrana, J.L.; et al. The MAD-related protein Smad7 associates with the TGFbeta receptor and functions as an antagonist of TGFbeta signaling. Cell 1997, 89, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, A.; Goldstein, R.H. The effect of transforming growth factor-beta on cell proliferation and collagen formation by lung fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 1987, 262, 3897–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Du, Y.; Shen, Y.; He, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, Z. TGF-beta 1 induced fibroblast proliferation is mediated by the FGF-2/ERK pathway. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012, 17, 2667–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, B.C.; Liebler, J.M.; Luby-Phelps, K.; Nicholson, A.G.; Crandall, E.D.; du Bois, R.M.; Borok, Z. Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells by transforming growth factor-beta1: potential role in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2005, 166, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Kubo, H.; Ota, C.; Takahashi, T.; Tando, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Fujino, N.; Makiguchi, T.; Takagi, K.; Suzuki, T.; et al. The increase of microRNA-21 during lung fibrosis and its contribution to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary epithelial cells. Respir Res 2013, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhu, M.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, P. MiRNA-21 functions in ionizing radiation-induced epithelium-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by downregulating PTEN. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2019, 8, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Xiao, T.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Sun, J.; Cheng, C.; Ma, H.; Xue, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A.; et al. miR-21 in EVs from pulmonary epithelial cells promotes myofibroblast differentiation via glycolysis in arsenic-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Environ Pollut 2021, 286, 117259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Chen, F.; Wang, K.; Song, Y.; Fei, X.; Wu, B. miR-15a/miR-16 cluster inhibits invasion of prostate cancer cells by suppressing TGF-beta signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 104, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z. Discovery and validation of extracellular/circulating microRNAs during idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis disease progression. Gene 2015, 562, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, M.; Reimann, T.; Hempel, U.; Wenzel, K.W.; Bierhaus, A.; Schuh, D.; Dimmer, V.; Haroske, G.; Muller, M. Loss of caveolin expression in type I pneumocytes as an indicator of subcellular alterations during lung fibrogenesis. Histochem Cell Biol 1998, 109, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.M.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, H.P.; Zhou, Z.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A.; Liu, F.; Ifedigbo, E.; Xu, X.; Oury, T.D.; Kaminski, N.; et al. Caveolin-1: a critical regulator of lung fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med 2006, 203, 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odajima, N.; Betsuyaku, T.; Nasuhara, Y.; Nishimura, M. Loss of caveolin-1 in bronchiolization in lung fibrosis. J Histochem Cytochem 2007, 55, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino Cardenas, C.L.; Henaoui, I.S.; Courcot, E.; Roderburg, C.; Cauffiez, C.; Aubert, S.; Copin, M.C.; Wallaert, B.; Glowacki, F.; Dewaeles, E.; et al. miR-199a-5p Is upregulated during fibrogenic response to tissue injury and mediates TGFbeta-induced lung fibroblast activation by targeting caveolin-1. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Yin, E.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Dong, Z.; Tai, W. CDKN2B antisense RNA 1 expression alleviates idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by functioning as a competing endogenouse RNA through the miR-199a-5p/Sestrin-2 axis. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 7746–7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.; Lyu, X.; Liu, Y.; Peng, N.; Tan, S.; Dong, L.; Zhang, X. Eupatilin inhibits pulmonary fibrosis by activating Sestrin2/PI3K/Akt/mTOR dependent autophagy pathway. Life Sci 2023, 334, 122218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Han, Q.; Hong, Y.; Li, W.; Gong, G.; Cui, J.; Mao, M.; Liang, X.; Hu, B.; Li, X.; et al. Inhibition of miR-199a-5p rejuvenates aged mesenchymal stem cells derived from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and improves their therapeutic efficacy in experimental pulmonary fibrosis. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, R.; Zheng, J.; Li, N.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, G. DZNep, an inhibitor of the histone methyltransferase EZH2, suppresses hepatic fibrosis through regulating miR-199a-5p/SOCS7 pathway. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.H.; Geng, L.; Wang, Y.; Sui, C.J.; Xie, F.; Shen, R.X.; Shen, W.F.; Yang, J.M. microRNA-199a-5p protects hepatocytes from bile acid-induced sustained endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yu, H.; Ding, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Fu, R. Molecular mechanism of ATF6 in unfolded protein response and its role in disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, W.T.; Blackwood, E.A.; Azizi, K.; Kaufman, R.J.; Glembotski, C.C. The ER Unfolded Protein Response Effector, ATF6, Reduces Cardiac Fibrosis and Decreases Activation of Cardiac Fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Banerjee, S.; de Freitas, A.; Sanders, Y.Y.; Ding, Q.; Matalon, S.; Thannickal, V.J.; Abraham, E.; Liu, G. Participation of miR-200 in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2012, 180, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yao, W.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, J.; Yan, W.; Xu, T.; Ji, X.; Ni, C. Long non-coding RNA-ATB promotes EMT during silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis by competitively binding miR-200c. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2018, 1864, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moimas, S.; Salton, F.; Kosmider, B.; Ring, N.; Volpe, M.C.; Bahmed, K.; Braga, L.; Rehman, M.; Vodret, S.; Graziani, M.L.; et al. miR-200 family members reduce senescence and restore idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis type II alveolar epithelial cell transdifferentiation. ERJ Open Res 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wilson, J.M.; Harvel, N.; Liu, J.; Pei, L.; Huang, S.; Hawthorn, L.; Shi, H. A systematic evaluation of miRNA:mRNA interactions involved in the migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. J Transl Med 2013, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, D.J.; Wu, M.; Le, T.T.; Cho, S.H.; Brenner, M.B.; Blackburn, M.R.; Agarwal, S.K. Cadherin-11 contributes to pulmonary fibrosis: potential role in TGF-beta production and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. FASEB J 2012, 26, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.; Milewski, D.; Le, T.; Ren, X.; Xu, Y.; Kalinichenko, V.V.; Kalin, T.V. FOXF1 Inhibits Pulmonary Fibrosis by Preventing CDH2-CDH11 Cadherin Switch in Myofibroblasts. Cell Rep 2018, 23, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, E.N.; Cochrane, D.R.; Richer, J.K. Targets of miR-200c mediate suppression of cell motility and anoikis resistance. Breast Cancer Res 2011, 13, R45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennard, S.I.; Crystal, R.G. Fibronectin in human bronchopulmonary lavage fluid. Elevation in patients with interstitial lung disease. J Clin Invest 1982, 69, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, H.; Jackstadt, R.; Hunten, S.; Kaller, M.; Menssen, A.; Gotz, U.; Hermeking, H. miR-34 and SNAIL form a double-negative feedback loop to regulate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 4256–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, K.V.; Corcoran, D.; Yousef, H.; Yarlagadda, M.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Gibson, K.F.; Konishi, K.; Yousem, S.A.; Singh, M.; Handley, D.; et al. Inhibition and role of let-7d in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010, 182, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Ma, C. Let-7a suppresses glioma cell proliferation and invasion through TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling pathway by targeting HMGA2. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 8107–8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgarra, R.; Pegoraro, S.; Ros, G.; Penzo, C.; Chiefari, E.; Foti, D.; Brunetti, A.; Manfioletti, G. High Mobility Group A (HMGA) proteins: Molecular instigators of breast cancer onset and progression. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2018, 1869, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Wu, D.; Ni, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Xiang, Y.; Dai, K.; Chen, X.; Li, X. MicroRNA let-7a regulates angiogenesis by targeting TGFBR3 mRNA. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, N.; Wen, L.; Peng, R.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Peng, H.; Sun, Y.; Wu, T.; Chen, L.; Duan, Q.; et al. Naringenin Ameliorated Kidney Injury through Let-7a/TGFBR1 Signaling in Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res 2016, 2016, 8738760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Gao, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.C.; Jia, M.W.; Peng, F.; Meng, Q.H.; Wang, Y.C. Low let-7d exosomes from pulmonary vascular endothelial cells drive lung pericyte fibrosis through the TGFbetaRI/FoxM1/Smad/beta-catenin pathway. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 13913–13926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homma, S.; Nagaoka, I.; Abe, H.; Takahashi, K.; Seyama, K.; Nukiwa, T.; Kira, S. Localization of platelet-derived growth factor and insulin-like growth factor I in the fibrotic lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 152, 2084–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.N.; Chen, W.W.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Xue, J.; Zhang, P.J.; Jiang, A.L. The miRNA let-7a1 inhibits the expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) in prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Asian J Androl 2013, 15, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, C.B.; Duffey, N.; Peyvandi, S.; Barras, D.; Martinez Usatorre, A.; Coquoz, O.; Romero, P.; Delorenzi, M.; Lorusso, G.; Ruegg, C. Gain of HIF1 Activity and Loss of miRNA let-7d Promote Breast Cancer Metastasis to the Brain via the PDGF/PDGFR Axis. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, H.; Allen, J.T.; Mason, R.M.; Kamimura, T.; Zhang, Z. TGF-beta1 induces human alveolar epithelial to mesenchymal cell transition (EMT). Respir Res 2005, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. The crucial role of activin A/ALK4 pathway in the pathogenesis of Ang-II-induced atrial fibrosis and vulnerability to atrial fibrillation. Basic Res Cardiol 2017, 112, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacedonia, D.; Scioscia, G.; Soccio, P.; Conese, M.; Catucci, L.; Palladino, G.P.; Simone, F.; Quarato, C.M.I.; Di Gioia, S.; Rana, R.; et al. Downregulation of exosomal let-7d and miR-16 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med 2021, 21, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Y. Exosomes derived from miR-16-5p-overexpressing keratinocytes attenuates bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021, 561, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Xiao, E.; Ning, H.; Li, K.; Shang, J.; Kang, Y. MiR-15b and miR-16 suppress TGF-beta1-induced proliferation and fibrogenesis by regulating LOXL1 in hepatic stellate cells. Life Sci 2021, 270, 119144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Xing, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liang, J.; Lin, Q.; Huang, M.; Chen, Y.; Lin, B.; Xu, X.; Chen, W. MiR-16-5p suppresses myofibroblast activation in systemic sclerosis by inhibiting NOTCH signaling. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 13, 2640–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, D.; D’Angelo, D.; Valentino, T.; De Martino, I.; Ferraro, A.; Wierinckx, A.; Fedele, M.; Trouillas, J.; Fusco, A. Downregulation of HMGA-targeting microRNAs has a critical role in human pituitary tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2012, 31, 3857–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamorro-Jorganes, A.; Araldi, E.; Penalva, L.O.; Sandhu, D.; Fernandez-Hernando, C.; Suarez, Y. MicroRNA-16 and microRNA-424 regulate cell-autonomous angiogenic functions in endothelial cells via targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and fibroblast growth factor receptor-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011, 31, 2595–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G.D.; Wang, H.S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.M.; Cai, X.H. miR-16 inhibits cell proliferation by targeting IGF1R and the Raf1-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 pathway in osteosarcoma. FEBS Lett 2013, 587, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Fan, S.; Song, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Cai, H.; Yi, L.; Dai, J.; Gao, Q. Plasma microRNAs are associated with acute exacerbation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Diagn Pathol 2016, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Wen, Y.H.; Pan, R.; Yang, J.; Yan, Y.M.; Zhao, A.Z.; Zhu, J.N.; Fang, X.H.; Shan, Z.X. Dickkopf 3: a Novel Target Gene of miR-25-3p in Promoting Fibrosis-Related Gene Expression in Myocardial Fibrosis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2021, 14, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genz, B.; Coleman, M.A.; Irvine, K.M.; Kutasovic, J.R.; Miranda, M.; Gratte, F.D.; Tirnitz-Parker, J.E.E.; Olynyk, J.K.; Calvopina, D.A.; Weis, A.; et al. Overexpression of miRNA-25-3p inhibits Notch1 signaling and TGF-beta-induced collagen expression in hepatic stellate cells. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, N.; McCuaig, S.; O’Sullivan, M.J.; Martin, J.G. Serotonin augments smooth muscle differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cell Res 2014, 12, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiot, J.; Cambier, M.; Boeckx, A.; Henket, M.; Nivelles, O.; Gester, F.; Louis, E.; Malaise, M.; Dequiedt, F.; Louis, R.; et al. Macrophage-derived exosomes attenuate fibrosis in airway epithelial cells through delivery of antifibrotic miR-142-3p. Thorax 2020, 75, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narasimhan, M.; Patel, D.; Vedpathak, D.; Rathinam, M.; Henderson, G.; Mahimainathan, L. Identification of novel microRNAs in post-transcriptional control of Nrf2 expression and redox homeostasis in neuronal, SH-SY5Y cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Yang, H.; Pan, L.; Wei, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, R.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, X. Ginkgo biloba Extract 50 (GBE50) Exerts Antifibrotic and Antioxidant Effects on Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice by Regulating Nrf2 and TGF-beta1/Smad Pathways. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Q.; Ren, L. The SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway mediates the anti-pulmonary fibrosis effect of liquiritigenin. Chin Med 2024, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Xiao, X.; Yang, Y.; Mishra, A.; Liang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yang, X.; Xu, D.; Blackburn, M.R.; Henke, C.A.; et al. MicroRNA-101 attenuates pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and activation. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 16420–16439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuga, L.J.; Ben-Yehudah, A.; Kovkarova-Naumovski, E.; Oriss, T.; Gibson, K.F.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.; Kaminski, N. WNT5A is a regulator of fibroblast proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009, 41, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.R.; Sills, W.S.; Hanrahan, K.; Ziegler, A.; Tidd, K.M.; Cook, E.; Sannes, P.L. Expression of WNT5A in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Its Control by TGF-beta and WNT7B in Human Lung Fibroblasts. J Histochem Cytochem 2016, 64, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lu, Y.; Lin, Y.Y.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Fang, J.H.; He, S.; Zhuang, S.M. Vascular mimicry formation is promoted by paracrine TGF-beta and SDF1 of cancer-associated fibroblasts and inhibited by miR-101 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett 2016, 383, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulito-Cueto, V.; Genre, F.; Lopez-Mejias, R.; Mora-Cuesta, V.M.; Iturbe-Fernandez, D.; Portilla, V.; Sebastian Mora-Gil, M.; Ocejo-Vinyals, J.G.; Gualillo, O.; Blanco, R.; et al. Endothelin-1 as a Biomarker of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Interstitial Lung Disease Associated with Autoimmune Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, I.; Fireman, E.; Topilsky, M.; Grief, J.; Schwarz, Y.; Kivity, S.; Ben-Efraim, S.; Spirer, Z. Effect of endothelin-1 on alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and on alveolar fibroblasts proliferation in interstitial lung diseases. Int J Immunopharmacol 1999, 21, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, M.A.; Katwa, L.; Spadone, D.P.; Myers, P.R. The effects of endothelin-1 on collagen type I and type III synthesis in cultured porcine coronary artery vascular smooth muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1996, 28, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, M.; Carpi, S.; Bellini, A.; Patalano, F.; Mattoli, S. Endothelin-1 induces increased fibronectin expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996, 220, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Hu, Y. TGFbeta1: Gentlemanly orchestrator in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Review). Int J Mol Med 2021, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Dong, N.; Fang, X.; Wang, X. Regulatory mechanisms of TGF-beta1-induced fibrogenesis of human alveolar epithelial cells. J Cell Mol Med 2016, 20, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, T.; Jiang, C.; Liu, G.; Miyata, T.; Antony, V.; Thannickal, V.J.; Liu, R.M. PAI-1 Regulation of TGF-beta1-induced Alveolar Type II Cell Senescence, SASP Secretion, and SASP-mediated Activation of Alveolar Macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2020, 62, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, U.I.; Munoz, E.F.; Flanders, K.C.; Roberts, A.B.; Sporn, M.B. Colocalization of TGF-beta 1 and collagen I and III, fibronectin and glycosaminoglycans during lung branching morphogenesis. Development 1990, 109, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, J.P.; Melder, D.C.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Modulation of collagen gene expression by cytokines: stimulatory effect of transforming growth factor-beta1, with divergent effects of epidermal growth factor and tumor necrosis factor-alpha on collagen type I and collagen type IV. J Lab Clin Med 1997, 130, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, N.J.; Ward, R.W.; McGrew, G.; Last, J.A. TGF-beta1 causes airway fibrosis and increased collagen I and III mRNA in mice. Thorax 2003, 58, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupsky, M.; Fine, A.; Kuang, P.P.; Berk, J.L.; Goldstein, R.H. Regulation of type I collagen production by insulin and transforming growth factor-beta in human lung fibroblasts. Connect Tissue Res 1996, 34, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Masta, S.; Meyers, D.; Narayanan, A.S. Collagen synthesis by normal and fibrotic human lung fibroblasts and the effect of transforming growth factor-beta. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989, 140, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmouliere, A.; Geinoz, A.; Gabbiani, F.; Gabbiani, G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 1993, 122, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Phan, S.H. Inhibition of myofibroblast apoptosis by transforming growth factor beta(1). Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999, 21, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesano, R.; Orci, L. Transforming growth factor beta stimulates collagen-matrix contraction by fibroblasts: implications for wound healing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988, 85, 4894–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoufos, G.; Kakoulidis, P.; Tastsoglou, S.; Zacharopoulou, E.; Kotsira, V.; Miliotis, M.; Mavromati, G.; Grigoriadis, D.; Zioga, M.; Velli, A.; et al. TarBase-v9.0 extends experimentally supported miRNA-gene interactions to cell-types and virally encoded miRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D304–D310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.M.; McCann, F.E.; Cabrita, M.A.; Layton, T.; Cribbs, A.; Knezevic, B.; Fang, H.; Knight, J.; Zhang, M.; Fischer, R.; et al. Identifying collagen VI as a target of fibrotic diseases regulated by CREBBP/EP300. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 20753–20763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, Y.; Kahn, M.; Ann, D.K.; Han, A.; Wang, H.; Nguyen, C.; Flodby, P.; Zhong, Q.; Krishnaveni, M.S.; et al. Interactions between beta-catenin and transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathways mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition and are dependent on the transcriptional co-activator cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP). J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 7026–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specks, U.; Nerlich, A.; Colby, T.V.; Wiest, I.; Timpl, R. Increased expression of type VI collagen in lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 151, 1956–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Pina, G.; Rubio, K.; Ordonez-Razo, R.M.; Barreto, G.; Montes, E.; Becerril, C.; Salgado, A.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H.; Aquino-Galvez, A.; Carlos-Reyes, A.; et al. ADAR1 Isoforms Regulate Let-7d Processing in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.; Xie, H.; Jin, Q.; Zhao, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Huang, X.; Sun, Y.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from neural EGFL-Like 1-modified mesenchymal stem cells improve acellular bone regeneration via the miR-25-5p-SMAD2 signaling axis. Bioact Mater 2022, 17, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Suo, L.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Wan, G.; Han, X. Activin a promotes myofibroblast differentiation of endometrial mesenchymal stem cells via STAT3-dependent Smad/CTGF pathway. Cell Commun Signal 2019, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, T.D.; Plumers, R.; Fischer, B.; Schmidt, V.; Hendig, D.; Kuhn, J.; Knabbe, C.; Faust, I. Activin A-Mediated Regulation of XT-I in Human Skin Fibroblasts. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, C.; Tan, C.; Zhang, J. Predictive biomarkers of disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Ryerson, C.J.; Myers, J.L.; Kreuter, M.; Vasakova, M.; Bargagli, E.; Chung, J.H.; Collins, B.F.; Bendstrup, E.; et al. Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis in Adults. An Official ATS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020, 202, e36–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, J.D.; Chevillet, J.R.; Kroh, E.M.; Ruf, I.K.; Pritchard, C.C.; Gibson, D.F.; Mitchell, P.S.; Bennett, C.F.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Stirewalt, D.L.; et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 5003–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, L.; Batte, K.; Wang, Y.; Wisler, J.; Piper, M. Analyzing the circulating microRNAs in exosomes/extracellular vesicles from serum or plasma by qRT-PCR. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 1024, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomos, I.; Roussis, I.; Matthaiou, A.M.; Dimakou, K. Molecular and Genetic Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Where Are We Now? Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainer, A.; Faverio, P.; Busnelli, S.; Catalano, M.; Della Zoppa, M.; Marruchella, A.; Pesci, A.; Luppi, F. Molecular Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: State of the Art and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, I.S.; Zagganas, K.; Paraskevopoulou, M.D.; Georgakilas, G.; Karagkouni, D.; Vergoulis, T.; Dalamagas, T.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G. DIANA-miRPath v3.0: deciphering microRNA function with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, W460–W466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quillet, A.; Saad, C.; Ferry, G.; Anouar, Y.; Vergne, N.; Lecroq, T.; Dubessy, C. Improving Bioinformatics Prediction of microRNA Targets by Ranks Aggregation. Front Genet 2019, 10, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L. Interaction of long noncoding RNAs and microRNAs in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Physiol Genomics 2015, 47, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, G.; Morris, K.V. All I’s on the RADAR: role of ADAR in gene regulation. FEBS Lett 2018, 592, 2860–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).