1. Introduction

Dengue fever is an arthropod-borne zoonotic viral infectious disease caused by the dengue virus (DENV) and is transmitted by anthropophilic mosquitoes [

1]. Two transmission cycles are recognized: the urban cycle and the sylvatic cycle. The urban cycle, well-documented in the Americas, involves humans as hosts and Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus as vectors. The sylvatic cycle is restricted to West Africa and Southeast Asia, involving non-human mammals (primates and other mammals) as hosts and various species of Aedes mosquitoes as vectors [

2].

In Argentina, cases of dengue caused by the DENV-1 and DENV-2 serotypes are reported annually, with only sporadic cases of DENV-3 and DENV-4. The Northwest and Northeast regions of the country have traditionally experienced the highest incidence [

3]. Based on epidemiological patterns and mosquito biology, dengue has not been considered endemic in Argentina, necessitating annual reintroductions from tropical regions such as Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia through viremic migrant individuals. However, an analysis of historical circulation dynamics reveals a sustained increase in the number and frequency of cases with which dengue epidemics occur in the country [

3]. Currently, Argentina is experiencing its largest dengue epidemic since the virus was reintroduced in 1997 [

4], with a total of 730,862 reported cases from epidemiological weeks 31/2023 to 22/2024 [

3]. For the first time, human cases were reported throughout the year in the northern subtropical area of the country. The increasing occurrence of indigenous dengue cases suggests a potential process of endemicity for the dengue virus. This scenario is evident when considering that 90% of the cases from the 2023-2024 outbreak are indigenous [

3].

One of the mechanisms through which DENV can become endemic is by establishing maintenance cycles in peri-urban and wild areas, involving other species of mammal hosts and mosquito vectors. Indeed, DENV and other zoonotic viruses have been detected in various sylvatic hosts [

5]. After rodents and primates, bats are the third group of mammals with the highest proportion of zoonotic viruses and have received significant attention as potential viral reservoirs [

6]. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the presence of the dengue virus in sylvatic populations of bats through a serological survey as an indicator of DENV spillback from urban to wild areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

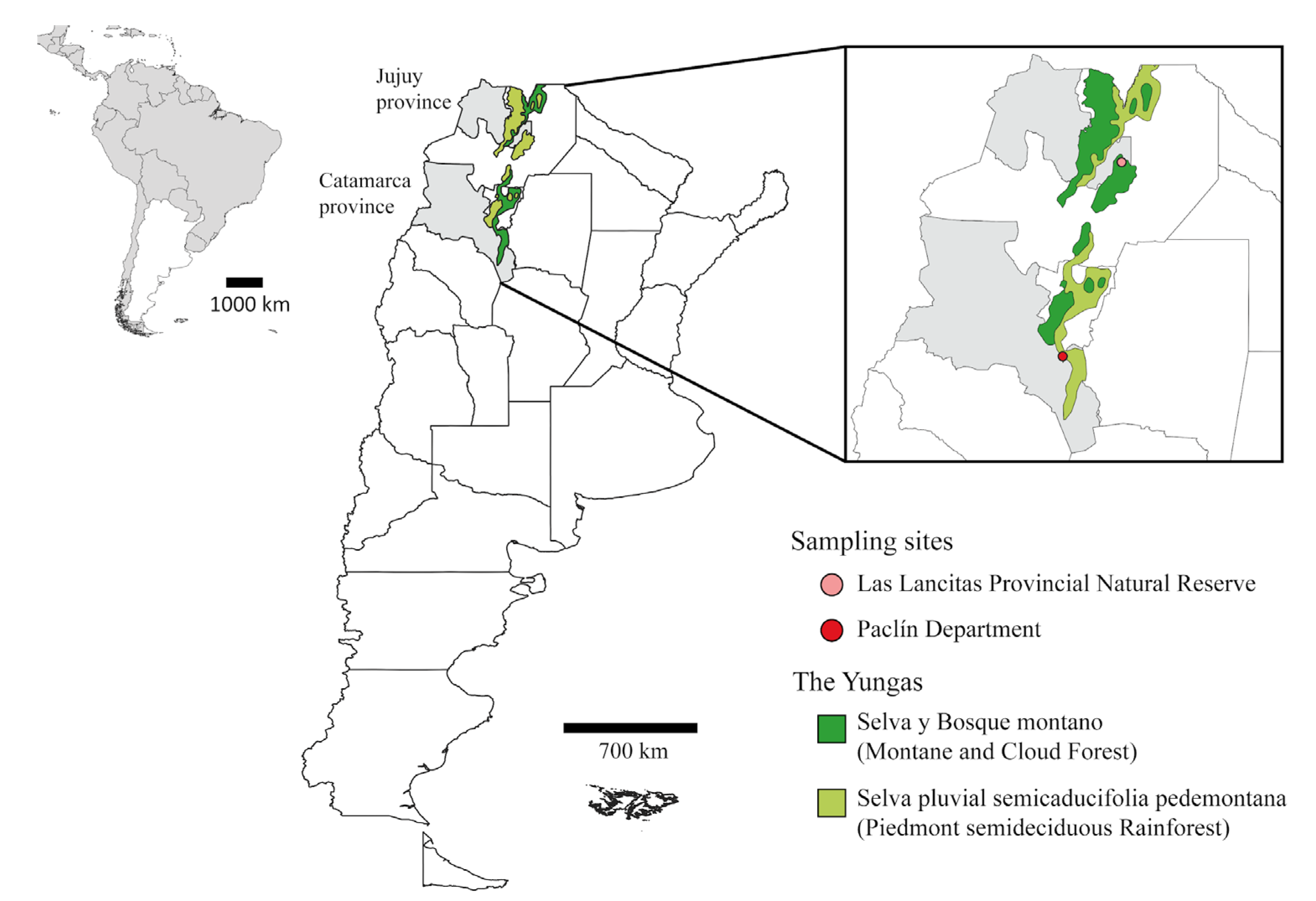

This study was conducted in the southern Yungas biogeographic province, located within the Jujuy and Catamarca provinces of Argentina. The Yungas biogeographic province is situated in the northwest of Argentina, encompassing the provinces of Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, and Catamarca. This area is characterized by a warm and humid climate, with average annual precipitation ranging between 900 and 1300 mm, mostly during the warm season [

7]. It is a narrow and highly biodiverse strip of subtropical rainforest that extends north to south across northwest Argentina for approximately 700 km [

8]. The region spans an altitudinal range of 400 to 3,000 meters above sea level, across various mountain ranges parallel to the Andes. In the southernmost part, the jungles and forests become fragmented, and their richness decreases until they are replaced by Chaco and Monte environments in the mountain ranges of the central-western Argentine Pampas [

7]. The mountainous structure creates a pronounced altitudinal gradient that influences climatic factors, resulting in altitudinal vegetation zones: the foothill forests and the cloud forests, characterized by various vegetation strata and abundant epiphytes, lianas, and support trees [

8]. This area hosts one of the richest biodiversity collections of bats, marsupials, rodents, and other mammals in Argentina. Among bats, most species belong to the family Phyllostomidae, including species such as

Sturnira lilium, S. erythromos, Artibeus planirostris, and

Desmodus rotundus. Notable marsupials include

Marsopa constantiae and

Thylamys sponsorius. Rodents, along with bats, are among the most represented orders, with more than eight genera and a dozen species. Some notable rodent species include

Akodon budini, Oligoryzomys brendae, and

Oxymycterus paramensis [

9].

2.2. Bat Capture and Sample Collection

Two sampling campaigns were conducted: one in April 2021 at wild locations within the “Las Lancitas Provincial Natural Reserve” (Jujuy province), and another in April 2022 at peri-urban and wild locations within the Paclín Department (Catamarca province) (

Figure 1). Bat capture was carried out using eight mist nets (9 m length × 2.5 m height, 36 mm mesh) placed at different sites and operated during sunset and night. Field sampling was performed for four consecutive days during each sampling event. The species and sex of each individual bat were recorded. Before release, blood-sampled bats were rehydrated with sugar water. Whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture using a 29 G needle. Bats weighing less than 10 grams were not blood-sampled. From each captured bat, a 100-200 µl blood sample was collected before being released. Blood was placed into a centrifuge tube containing 0.45 mL or 0.9 mL (depending on the blood sample volume: 0.1 ml or 0.2 ml, respectively) of Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) for an approximate 1:10 serum dilution. The samples were held at ambient temperature for 20–30 minutes for coagulation and then placed into coolers. In the laboratory, samples were centrifuged at 5,000g for 15 minutes to separate the serum. Sera were stored at -20°C.

2.3. Serological Assay

Serum samples were analyzed to detect neutralizing antibodies (NTAb) against dengue virus serotype 1 (DENV-1 Puerto Rico strain) using the Plaque-Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT) in the Vero Cl76 cell line (ATCC CRL-587). Positive samples were also tested against St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV CbaAr-4005 strain), West Nile virus (WNV E/7229/06 strain), and Yellow Fever virus (YFV vaccine 17D-YEL strain), as these flaviviruses circulate in the country and could potentially yield false positives. Prior to analysis, serum samples were heat-inactivated for 30 minutes at 56°C to inactivate non-specific inhibitors of virus neutralization. A suspension of approximately 100 plaque-forming units (PFU) of virus in 75 μL of MEM was added to an equal volume of bat serum, resulting in a final serum dilution of 1:20. The mixture was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Vero cell monolayers grown in 24-well culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) were inoculated with 0.1 mL of the serum-virus mixture and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C, 5% CO2. On the seventh day post-inoculation, inoculated cells were fixed with a 10% formalin solution for 1 hour. Finally, cells were stained with crystal violet solution, and viral PFU were counted by visual inspection. Serum samples that neutralized ≥ 80% of the inoculated PFUs were considered positive and were further titrated to determine NTAb titers. Six serial two-fold dilutions of serum were prepared, resulting in final dilutions of 1:20, 1:40, 1:80, 1:160, 1:320, and 1:640. Endpoint titers were assigned as the reciprocal of the maximum dilution yielding ≥ 80% reduction in the number of plaques [

10].

3. Results

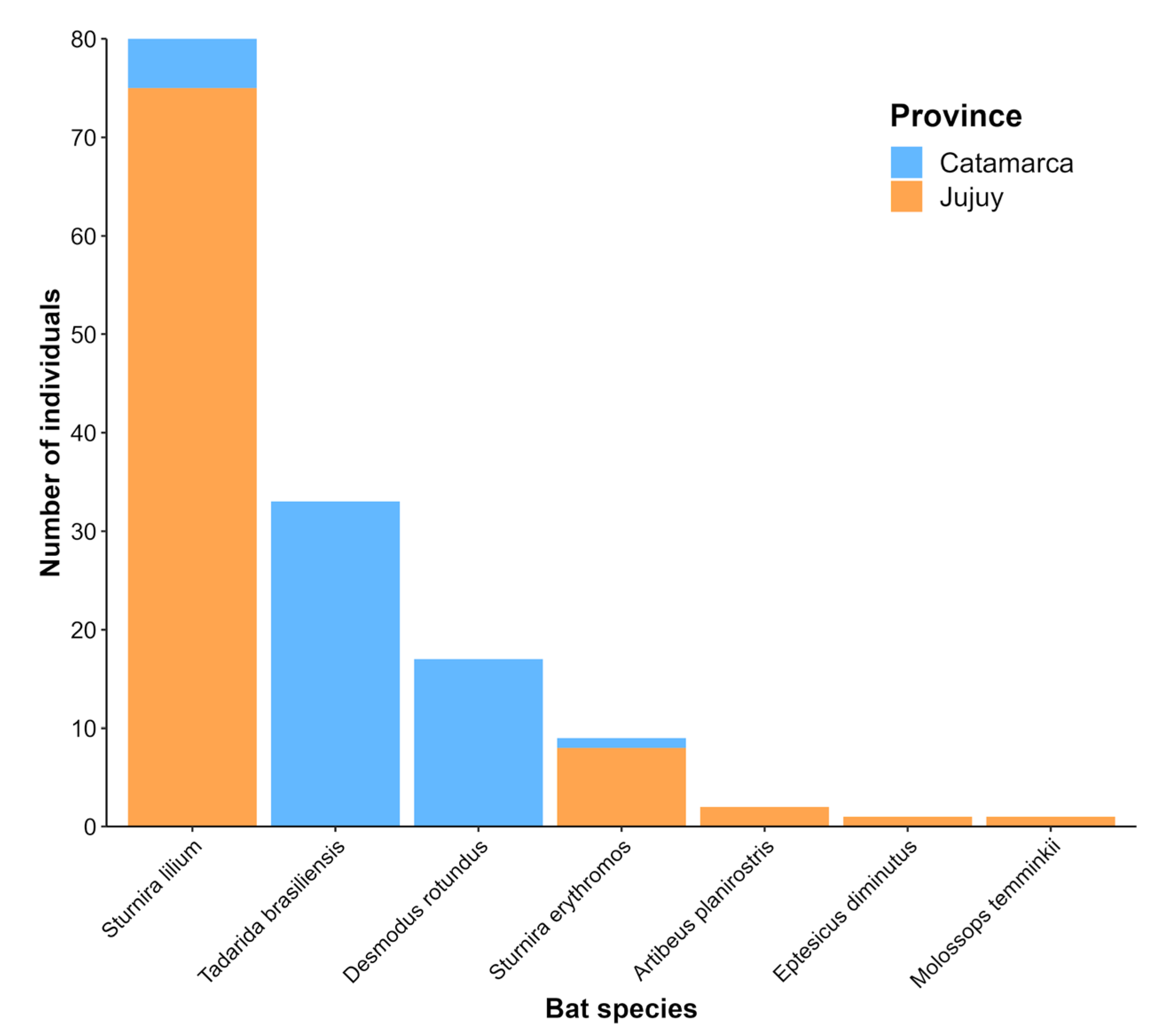

A total of 143 bats (83 males, 57 females, and 3 individuals not sexed) representing 2 families (Phyllostomidae and Molossidae) and 7 species were captured during the sampling sessions. A total of 87 individuals (61%) were captured in Jujuy in April 2021, and 56 individuals (39%) were captured in Catamarca in April 2022. The most abundant species were

Sturnira lilium (56%),

Tadarida brasiliensis (23%),

Desmodus rotundus (12%), and

Sturnira erythromos (6%). The remaining 3% comprised the species

Artibeus planirostris, Eptesicus diminutus, and

Molossops temminckii. The distribution of species abundance by province is shown in

Figure 2. The overall seroprevalence of NTAb for DENV-1 was 2.8% (4/143), with positive results found in four species:

S. lilium, S. erythromos, and

A. planirostris from Jujuy, and

T. brasiliensis from Catamarca (

Table 1). Although the highest seroprevalence was detected in

A. planirostris, it should be noted that this result is based on a small sample size (n=2) (

Table 1). The seroprevalence in Jujuy province was 3.5% (3/87, 95% CI: [0.7-9.7]), while in Catamarca province it was 1.8% (1/56, 95% CI: [0.04-9.5]). All positive samples were from sylvatic habitats and corresponded to frugivorous (

S. lilium, S. erythromos, A. planirostris) and insectivorous (

T. brasiliensis) bat species. The DENV-1 antibody titers were 20 for

S. lilium and

S. erythromos, and 40 for

A. planirostris and

T. brasiliensis. Only one of the four positive samples (

T. brasiliensis from Catamarca) exhibited a heterotypic reaction, also testing positive for SLEV and WNV with a titer of 40. Additionally, three serum samples from Catamarca, belonging to

T. brasiliensis individuals, were cytotoxic, making it impossible to determine their serological status.

4. Discussion

In South American bats, DENV serotypes 1-4 have been found circulating in both endemic and non-endemic areas, suggesting a spillback process of DENV from humans to wild mammals. This could potentially trigger the establishment of independent enzootic cycles involving unknown mammal species, such as bats or rodents [

11]. Spillback implies the possibility that urban strains might spread to forest areas during severe epidemics and infect wild mammals and mosquitoes, facilitated by activities like hunting, logging, or tourism, a transmission dynamic previously suspected in other pathogens, such as

Plasmodium falciparum [

12]. The presence of enzootic cycles is supported by the identification of DENV strains in wild hosts and vectors, either distinct from or similar to those found during human epidemics, discovered at various times in peri-urban and forested areas with limited human contact [

12]. Moreover, enzootic transmission foci can act as a source for urban dengue transmission.

Robles-Fernández et al. [

13] performed an analysis using machine learning to predict which mammal species in the Americas are most susceptible to DENV infection and could potentially act as hosts for the virus. Surprisingly, the top ten most DENV-susceptible species were all bats, highlighting species such as

S. lilium, confirmed in our study to be positive for DENV NTAb, and

Desmodus rotundus, a species occurring in Argentina that was captured in our sampling campaigns but tested negative. Additionally, another group identified as highly likely to be DENV carriers includes marsupials and possibly rodents. These data underscore the need to study the presence of DENV directly or indirectly in a wide spectrum of mammals, including but not limited to Chiroptera.

Some experimental studies have been conducted to evaluate the susceptibility of bats to DENV, but the findings have been contradictory. It is often stated that bats may not be ideal reservoir hosts due to their inability to sustain virus replication at levels high enough to infect blood-feeding mosquitoes, as shown in

A. intermedius and

A. jamaicensis [

14,

15]. However, infected

Myotis lucifugus exhibited symptoms of DENV infection, suggesting viral replication [

16]. Given that only three bat species have been studied experimentally and considering the vast diversity of bats and their unique immune systems that promote viral tolerance [

17], more research is necessary to definitively determine whether bats are reservoirs for DENV and other arboviruses.

In Argentina, DENV reemerged in 1997 in the province of Salta, near the study area [

4]. Since then, human cases have been reported annually, especially in the northern region of the country. In recent years, the number of cases and frequency of DENV outbreaks have dramatically increased, indicating the possibility of endemicity for the virus in this region. One ecological strategy for the virus to become endemic is to establish wild transmission networks outside urban areas (spillback process). The presence of virus exposure in wild mammals such as bats and the detection of the virus in wild mosquitoes can be indicators of virus spillback. This study confirms that sylvatic bat populations in Argentina are exposed to DENV and that the virus is potentially maintained in wild areas. Although DENV has been detected in over 80 bat species globally, this research is the first to confirm exposure in

S. erythromos and

T. brasiliensis. However, the presence of DENV NTAb in

T. brasiliensis should be interpreted with caution, as it also had NTAb for SLEV and WNV, indicating possible cross-reaction or sequential infection.

These results raise the question of which mammals could be acting as agents for the circulation of DENV in sylvatic environments. In Argentina, a previous study was conducted in the northeast to detect NTAb against several flaviviruses (DENV, WNV, SLEV, ILHV -Ilheus virus-, BSQV -Bussuquara virus-, and YFV) in sylvatic populations of black howler monkeys (

Alouatta caraya), a non-human primate (NHP), in the provinces of Chaco and Corrientes [

18]. Of the 108 sera analyzed from the black howlers, approximately 30% (32/108) tested positive for DENV, indicating a possible sylvatic circulation of DENV in wild environments in northeastern Argentina. However, the howler monkey populations tested were established close to human dwellings [

18].

In conclusion, this study represents a step forward in demonstrating DENV infections in wild bat populations; however, further research is necessary to determine the role of these mammals as reservoirs for DENV and their impact on virus endemicity. Additionally, a greater focus on vector biology is essential to assess mosquito diversity in sylvatic areas, their feeding patterns, and particularly their vector competence, to determine whether sylvatic mosquitoes are susceptible and competent vectors of the dengue virus [

19].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F., A.A.S., J.H.U. and A.D.; methodology, I.F., M.C.C., A.A.S., J.H.U. and A.D.; software, K.A.R. and A.D.; validation, all; formal analysis, K.A.R. and A.D.; investigation, K.A.R., J.A., A.A.F. and L.S.; resources, I.F., M.C.C. and A.D.; data curation, all; writing—original draft preparation, all; writing—review and editing, all; visualization, all; supervision, I.F. and A.D.; project administration, I.F. and A.D.; funding acquisition, I.F. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Programa ImpaCT.AR Desafío N°83 (Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación -MINCyT-), PICT 2018-01172 and PICT 2021-00545 (Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica -FONCYT-MINCYT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The capture, manipulation, blood collection, and transport of samples were approved by the Secretaría de Biodiversidad y Ambiente of Jujuy province (Res. N° 040/2017-SB) and by the Secretaría de Medio Ambiente of Catamarca province (DISPC-2024-172-E-CAT-SEMA#MAEMA). Bat captures and handling were carried out in accordance with the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986, and associated guidelines, EU Directive2010/63/EU for animal experiments. All methods and procedures complied with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

To Oscar Peinado (Instituto de Ecorregiones Andinas (INECOA- CONICET-UNJu) for the technical support of the institutional vehicle. We would like to thank Agustin Quaglia and Melisa D’Occhio for their assistance in field work, and Franco Haehnel, Lucia Prieto, and Leticia Daugero for their help in laboratory work. Also, we would like to thank Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Virales Humanas (INEVH) “Dr. Julio I. Maiztegui”, Pergamino, Argentina for providing the DENV-1 strain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Weaver, S.C.; Vasilakis, N. Molecular evolution of dengue viruses: contributions of phylogenetics to understanding the history and epidemiology of the preeminent arboviral disease. Infect Genet Evol 2009, 9, 523–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Santos, A.; Moreira-Soto, A.; Soto-Garita, C.; Chaverri, L.G.; Chaves, A.; Drexler, J.F.; Morales, J.A.; Alfaro-Alarcón, A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, B.; Corrales-Aguilar, E. Neotropical Bats That Co-Habit with Humans Function as Dead-End Hosts for Dengue Virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud de la República Argentina. Boletín Epidemiológico Nacional 2024, 2024.

- Avilés, G.; Rangeón, G.; Vorndam, V.; Briones, A.; Baroni, P.; Enria, D.; Sabattini, M.S. Dengue Reemergence in Argentina. Emerg Infect Dis 1999, 5, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwee, S.X.W.; St John, A.L.; Gray, G.C.; Pang, J. Animals as Potential Reservoirs for Dengue Transmission: A Systematic Review. One Health 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Aguilar, I.; Lorenzo, C.; Santos-Moreno, A.; Gutiérrez, D.N.; Naranjo, E.J. Current Knowledge and Ecological and Human Impact Variables Involved in the Distribution of the Dengue Virus by Bats in the Americas. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2021, 21, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkart, R.; Bárbaro, N.O.; Sánchez, R.O.; Gómez. Daniel, O. Eco-Regiones de La Argentina; Administración de Parques Nacionales: Buenos Aires, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arana, M.D.; Natale, E.; Ferretti, N.; Romano, G.; Oggero, A.; Martínez, G.; Posadas, P. ; Morrone, Juan. J. Esquema Biogeográfico de La República Argentina; Opera Lilloana: San Miguel de Tucumán, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alurralde, S.G.; Berrizbeitia, M.F.L.; Barquez, R.M.; Díaz, M.M. Diversity and Richness of Small Mammals at a Well-Conserved Site of the Yungas in Jujuy Province, Argentina. Mammalia 2016, 80, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L.A.; Quaglia, A.I.; Konigheim, B.S.; Boris, A.S.; Aguilar, J.J.; Komar, N.; Contigiani, M.S. Activity Patterns of St. Louis Encephalitis and West Nile Viruses in Free Ranging Birds during a Human Encephalitis Outbreak in Argentina. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0161871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoisy, B. De; Lacoste, V.; Germain, A.; Muñoz-Jordán, J.; Colón, C.; Mauffrey, J.F.; Delaval, M.; Catzeflis, F.; Kazanji, M.; Matheus, S.; et al. Dengue Infection in Neotropical Forest Mammals. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2009, 9, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volney, B.; Pouliquen, J.F.; De Thoisy, B.; Fandeur, T. A Sero-Epidemiological Study of Malaria in Human and Monkey Populations in French Guiana. Acta Trop 2002, 82, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Fernández, Á.L.; Santiago-Alarcon, D.; Lira-Noriega, A. American Mammals Susceptibility to Dengue According to Geographical, Environmental, and Phylogenetic Distances. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 604560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Martínez, L.; Moreno-Sandoval, H.N.; Moreno-Altamirano, M.M.; Salas-Rojas, M.; García-Flores, M.M.; Aréchiga-Ceballos, N.; Tordo, N.; Marianneau, P.; Aguilar-Setién, A. Experimental Infection of Artibeus intermedius Bats with Serotype-2 Dengue Virus. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2013, 36, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Romo, S.; Recio-Totoro, B.; Alcalá, A.C.; Lanz, H.; Del Angel, R.M.; Sánchez-Cordero, V.; Rodríguez-Moreno, A.; Ludert, J.E. Experimental Inoculation of Artibeus jamaicensis Bats with Dengue Virus Serotypes 1 or 4 Showed No Evidence of Sustained Replication. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014, 91, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reagan, R.L.; Brueckner, A.L. Studies of Dengue Fever Virus in the Cave Bat (Myotus Lucifugus). J Infect Dis 1952, 91, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, M.; Yovel, Y. Revising the Paradigm: Are Bats Really Pathogen Reservoirs or Do They Possess an Efficient Immune System? iScience 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, M.A.; Fabbri, C.M.; Zunino, G.E.; Kowalewski, M.M.; Luppo, V.C.; Enría, D.A.; Levis, S.C.; Calderón, G.E. Detection of the Mosquito-Borne Flaviviruses, West Nile, Dengue, Saint Louis Encephalitis, Ilheus, Bussuquara, and Yellow Fever in Free-Ranging Black Howlers (Alouatta caraya) of Northeastern Argentina. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0005351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, L.D.; Ebel, G.D. Dynamics of Flavivirus Infection in Mosquitoes. Adv Virus Res 2003, 60, 187–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).