1. Introduction

Culinary tourism, also widely recognized as food tourism, represents an evolving and increasingly significant segment of the global travel industry, capturing the interest of destination managers, academics, and marketing professionals. As a vital element of the tourist experience, gastronomy wields considerable influence over travelers’ decision-making processes and their perception of destinations [

1,

2]. The allure of distinctive culinary experiences draws tourists to explore new destinations, driven by the desire to engage with local cuisines that serve as gateways to understanding community identity, culture, and traditions [

3,

4]. Gastronomy, thus, functions not only as a component of sensory exploration but also as a medium of symbolic communication, revealing insights into a community’s values and way of life [

5,

6]. Among others, the United Nations World Tourism Organization [

7] recognizes that gastronomy tourism constitutes a core driver of the attractiveness and competitiveness of travel destinations. Such an emerging interest in food experiences reflects shifting tastes among tourists – who increasingly look for absorbing and novel cultural experiences away from standard tourism offerings [

8,

9]. Inasmuch as gastronomic experiences contribute to the overall tourism experience, systematic research has not been conducted as to how culinary preferences and experiences influence tourist behavior and destination choices. Differences in understanding gastronomy also point to the complexities associated with such emotional attachments and hence their limited impact on tourist behaviour [

10,

11]. Although national cuisines can attract culinary tourists, several limitations can affect their success in travel promotion. One major issue is the risk of cultural misrepresentation. National cuisines are typically rich and varied, with distinct regional and historical influences. Simplifying these cuisines to appeal to tourists can strip away their authenticity, potentially leading to dissatisfaction among those seeking genuine culinary experiences [

12]. Another challenge is the seasonal availability of certain ingredients. Many traditional dishes depend on fresh, locally sourced ingredients that may not be accessible year-round, impacting the quality and consistency of the culinary experiences offered [

13]. Additionally, certain traditional foods are linked to specific cultural or religious festivals, making them unavailable at other times, which could disappoint tourists visiting outside these periods [

14]. Health and safety concerns also arise, as tourists may not be familiar with local food preparation practices, potentially leading to food safety issues [

3]. Furthermore, promoting national cuisines must consider the diverse dietary restrictions and preferences of international tourists, which may not always align with traditional dishes [

15]. Addressing these limitations requires a thoughtful approach that balances authenticity with tourist expectations and needs. The present study tries to overcome this limitation by examining the direct and/or moderated relationships among gastronomic involvement and knowledge, past experiences, and their joint impact on perceived gastronomic and destination attractiveness, and hence on tourist satisfaction and willingness to recommend. More specifically, the present research focuses on Northern Cyprus and the motivations of culinary tourists and the implications that these have for destination marketing strategies. As shown above, recent research has highlighted the many and varied aspects of culinary tourism. Bessiere and Tibere [

16] examined how local food contributes to the narratives of home and away, while Kim, Eves, and Scarles [

17] investigated how sensory food experiences increase travelers’ destination loyalty. Such research underscores destination needs for exploiting their differential culinary endowments primarily to enhance the experience and satisfaction of their tourists [

18].

The current research has three main objectives: The first is to outline the relationships between gastronomic factors and destination appeal. The second is to analyze how gastronomic appeal influences tourist satisfaction and recommendation intentions. The third is to provide insights for attracting culinary tourists to Northern Cyprus.

No study has been found in the existing literature that elucidates the intricate interplay between gastronomic involvement, gastronomic knowledge, past gastronomic experiences, gastronomic attractiveness, destination attractiveness, tourist satisfaction, and the intention to revisit, encompassing all these variables together. In this regard, it is believed that this research will make a significant contribution to the mainstream literature.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gastronomy Involvement Gastronomy Attractiveness and Destination Attractiveness

Consumer behavior helps in understanding processes through which decisions are made concerning products, brands, and services. In this context, involvement, particularly with gastronomy, is associated with the degree to which people are willing to get involved, their experiences, and their likes [

19,

20]. Gastronomy involvement is conceived as the subjective personal relevance and importance perceived by an individual in at least some dimensions between food and culinary experiences that account for or shape the predisposition and styles of individual life in the daily decisions and behavior [

21].

The tourism destinations are realizing the power of gastronomy in this competitive scenario as a unique selling proposition to drive and retain. Studies have revealed a positive relationship between the level of satisfaction shown by tourists with culinary experiences and their intention to revisit a destination. Here the service elements, such as food quality, the efficiency of the service delivery, and other types of service, including parking, play a very important role in enhancing the tourism value proposition [

22].

The global tourism space is increasingly witnessing demand for the authentic local gastronomy experiences that represent the cultural and gastronomic landscape of various destinations. Unique and indigenous cuisines have the power of turning local food to attractive tourism products, which then augments the appeal of the destination for tourists [

23,

24]. This reflects the trend of changing consumer preference to experiences, which translates into deep understanding of local culture and lifestyle; almost mediated using gastronomy.

Tourist gastronomic involvement (GI) refers to the degree to which individuals engage with and value culinary experiences during their travels. High levels of GI indicate that tourists are more willing to invest time and effort into experiencing the local food culture, which, in turn, enhances their appreciation and enjoyment of these culinary experiences. Research indicates that tourists who are highly involved in gastronomic activities tend to develop a deeper understanding and appreciation of the local cuisine, leading to a heightened perception of its attractiveness. This positive relationship suggests that as tourists become more engaged with the local food scene, they are more likely to view the destination’s gastronomy as a key attractive feature [

25,

26].

Perceived destination attractiveness (DA) refers to the overall appeal of a destination, encompassing various attributes such as natural beauty, cultural heritage, and culinary offerings. Gastronomy is a crucial component of the destination’s appeal, and tourists’ involvement in gastronomic activities can significantly influence their overall perception of the destination. Studies have shown that tourist gastronomic involvement (GI) positively impacts DA by enhancing tourists’ experiences and satisfaction with the destination’s culinary offerings. When tourists actively engage in and enjoy the local gastronomy, they are more likely to develop favorable attitudes toward the destination [

27,

28].

This involvement creates memorable and meaningful experiences that contribute to a positive overall impression of the destination. The quality and uniqueness of the local food, coupled with the enjoyment derived from culinary experiences, can significantly enhance the destination’s attractiveness. As such, destinations that effectively promote and leverage their culinary heritage can increase their overall appeal to tourists [

1,

15]. Thus, we consider the following hypotheses:

H1a: Tourist gastronomic involvement (GI) is positively associated with perceived gastronomy attractiveness (GA).

H1b: Tourist gastronomic involvement (GI) is positively associated with perceived destination attractiveness (DA).

2.2.1. Destination Attractiveness and Gastronomy Knowledge

The dissemination of tourism information is vital in shaping tourists’ perceptions and choices, divided into formal sources like marketing materials and informal sources like word-of-mouth and online content [

29]. Local gastronomy significantly impacts destination information, influencing tourists’ expectations and interest in culinary exploration [

30]. Understanding a destination’s culinary offerings enhances the travel experience and satisfaction [

26], contributing to a deeper cultural appreciation [

10]. Studies show that gastronomic knowledge increases the attractiveness of both culinary experiences and the destination [

31,

32]. Leveraging this knowledge strategically can enhance tourist engagement and satisfaction [

33]. Tourists Knowledge of Gastronomy (GK): Measured by familiarity with local dishes, ingredients, and cooking methods. Perceived Destination Attractiveness (DA): Assessed through a composite evaluation of the destination’s natural beauty, cultural attractions, infrastructure, and the quality of gastronomic experiences.

Given gastronomy’s importance in tourism, it’s essential to explore how gastronomic involvement impacts perceptions of gastronomic and destination attractiveness. This research suggests that greater gastronomic involvement positively influences these perceptions, contributing to a fulfilling travel experience.

In this context, two hypotheses are posited to examine the relationship between gastronomic knowledge and its impact on destination appeal:

H2a: Tourists’ knowledge of gastronomy (GK) is positively associated with their perceived gastronomy attractiveness (GA).

H2b: Tourists’ knowledge of gastronomy (GK) is positively associated with their perceived destination attractiveness (DA).

2.2.2. Past Gastronomy Experience Gastronomy and Destination Attractiveness

The basic pattern between a tourist’s relationship with specific activities and the ensuing perceptions and behaviors is an essential element of tourism studies. Trauer [

34] argues the relationship of a “love system” explains that a particular activity or element of destination is subject to a tourist’s love when a combination of involvement, knowledge, and prior experiences has been accrued. This model can be easily transferable to gastronomy tourism because the tourists’ engagement and their ensuing experiences with the local cuisine deliver signals upon which to base a positive predilection toward the destination’s gastronomic attractiveness.

A final spate understanding the role of prior gastronomic experiences has more specifically been defined on the destination perception of a tourist. A tourist’s prior experiences not only enhance their knowledge but contribute to a deeper relationship with the destination, and that relationship is held to be more attractive from the tourists’ perceptions about the destination [

25,

35]. Such experiences further consolidate a positive cyclical relationship—a model in which enriched gastronomic knowledge and positive prior experiences increase a tourist’s satisfaction with the destination’s offerings. Previous Gastronomic Experiences (PGE): Assessed based on the frequency and type of gastronomic activities previously undertaken and the satisfaction derived from those experiences.

National literature extensively investigates the key elements of customers’ gastronomic experiences, such as the quality of the physical environment, food, and service [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Furthermore, the connection between gastronomic experiences and factors like loyalty, satisfaction, gastronomic appeal, gastronomic image, and revisit intentions is also widely studied [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

In this vein, the study proposes two hypotheses to explore the influence of previous gastronomic experiences on perceptions of gastronomy and destination attractiveness:

H3a: A tourist’s previous gastronomic experiences (PGE) are positively associated with their perceived gastronomy attractiveness (GA).

H3b: A tourist’s previous gastronomic experiences (PGE) are positively associated with their perceived destination attractiveness (DA).

2.2.3. Gastronomy Attractiveness and Destination Attractiveness

A traveler’s perceptions and feelings about a destination’s ability to meet their vacation desires form the concept known as destination attractiveness. This construct encompasses expectations, preferences, and evaluations regarding the destination’s capacity to provide a fulfilling holiday experience [

50]. Related to this is destination competitiveness, which reflects a destination’s ability to offer superior products and experiences compared to others [

51].

Scholarly discussions on destination attractiveness typically fall into three main frameworks. The first framework uses a broad perspective to define competitiveness through general characteristics and dynamic factors [

52]. The second framework adopts a resource-based view, focusing on inherent assets and capabilities [

53]. The third situational approach identifies specific attributes relevant to different research contexts [

54].

The importance of destination attractiveness has been emphasized in various studies for its role in attracting tourists, balancing tourism supply and demand, and aiding strategic tourism planning [

53,

54,

55]. The World Economic Forum’s Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI) further underscores this concept by offering a comparative analysis of global destination performance [

56].

Gastronomy also plays a significant role in enhancing destination attractiveness. As Brillat-Savarin [

57] suggested, the enjoyment of gastronomy goes beyond sensory pleasure, engaging individuals in a cultural narrative that reflects a civilization’s customs and uniqueness [

58]. Thus, the connection between gastronomy and destination attractiveness is deeply rooted in cultural expression and experience.

Considering this, the following hypothesis is proposed to explore the relationship between gastronomy attractiveness and destination attractiveness:

H4: The perceived attractiveness of gastronomy (GA) is positively associated with the perceived attractiveness of the destination (DA).

2.2.4. Gastronomy Attractiveness Destination Attractiveness and Satisfaction

The satisfaction gap concept highlights the difference between consumers’ expectations before a purchase and their actual experiences afterward, acting as an indicator of how satisfied they are with products and services [

59]. The assessment of customer satisfaction involves a thorough analysis of perceptions and experiences, providing valuable insights into the quality and appeal of offerings [

60]. In the tourism sector, gastronomy is increasingly recognized not merely as a supplementary experience but as a core element contributing significantly to overall tourist satisfaction [

61].

Chen and Huang [

62] assert that the impact of gastronomy on creating memorable tourist experiences should not be underestimated, echoing the sentiment that novelty in culinary experiences often piques human interest and can serve as a potent motivator for travel [

63]. Meler and Cerovic [

64] note that travelers often seek unique and unexpected culinary experiences that differ from their usual diets. Discovering new cuisines can enhance the perceived attractiveness of a destination and create a sense of engagement and attachment [

65]. Local cuisine, an essential element of the tourism experience, significantly influences tourist satisfaction [

66]. This indicates that both the allure of gastronomy and the overall appeal of a destination are crucial in shaping tourists’ satisfaction levels.

In view of the above, this study posits two hypotheses to examine the direct influence of perceived gastronomy attractiveness (GA) and destination attractiveness (DA) on tourist satisfaction (TS):

H5: Perceived gastronomy attractiveness (GA) is positively associated with tourist satisfaction (TS).

H6: Perceived destination attractiveness (DA) is positively associated with tourist satisfaction (TS).

2.2.5. Satisfaction and Intention to Re-Visit

Tourist satisfaction, a critical predictor of traveler loyalty, is often gauged by post-trip behaviors such as the intention to revisit or recommend a destination. Existing research underlines that satisfaction plays a significant role in influencing a tourist’s likelihood to engage in positive word-of-mouth and to consider revisiting a destination, thereby bolstering its reputation [

67].

Customer satisfaction is widely acknowledged to foster repeat patronage and amplify word-of-mouth referrals, crucial drivers for a destination’s sustained success [

68]. While Bigné et al. [

69] could not establish a direct causal relationship between satisfaction and revisit intention, they did note a positive correlation between satisfaction and the propensity to recommend a destination. Hui, Wan, and Ho [

70] provided an insight that tourists satisfied with their overall journey are more likely to recommend the destination rather than revisit, perhaps due to the inherent desire for novel experiences. This highlights that satisfaction may not invariably result in repeat visitation but can significantly impact referral intentions [

71,

72]. Tourist Satisfaction (TS): Represented by overall contentment with experiences at the destination, including accommodation, activities, and culinary experiences.

Tourists with positive gastronomic experiences are more inclined to revisit the same destination in the future [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. Additionally, tourist satisfaction positively influences their likelihood of recommending the destination to others [

75,

78,

79], generating a beneficial domino effect for the destination’s gastronomic tourism. The success in achieving tourist satisfaction in gastronomy tourism not only encourages plans for future visits but also prompts tourists to recommend the destination to others. Sutiadiningsih et.al.[

80], supports this finding, demonstrating that satisfied tourists are more likely to plan return visits and recommend gastronomy tourism destinations to others.

Loyalty, or the propensity to return, remains a cornerstone of the service industry, with a clear understanding of consumer behavior motives being imperative for tourism managers aiming to build a positive brand image and enhance marketing efforts [

81]. Tourists’ intentions to return or recommend are influenced by their previous experiences, with satisfaction from past visits being a salient indicator [

82].

The interplay of satisfaction with behavioral intentions, such as recommending and revisiting, is fundamental to tourism management. Word-of-mouth referrals, considered one of the most trustworthy and efficient marketing tools, rely on the credibility granted by personal endorsements from fellow travelers, friends, and family [

83]. As such, tourist satisfaction is a pivotal factor in shaping these influential behaviors.

Considering the discussions, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H7: Tourist satisfaction (TS) positively influences their intention to revisit (REI).

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Attitude Theory

Attitude theory has been essential in understanding consumer behavior, especially in tourism, where attitudes significantly influence travel decisions. Based on mid-20th-century expectancy-value models, it posits that individuals form attitudes from their beliefs about behavior outcomes and their valuations of these outcomes [

84]. This theory explains how subjective probabilities and evaluations shape attitudes, assessed indirectly through beliefs and outcomes.

Recent studies in tourism explore how attitudes influence behaviors, such as revisiting or recommending destinations. While indirect measures offer insights into cognitive processes, direct measures more effectively predict behaviors [

84]. The immediacy principle asserts that direct measures, closely linked to behavioral intentions and actions, are stronger predictors of outcomes [

85]. Understanding attitudes’ direct impact is crucial for destination marketers. Allport [

86] highlighted that attitude, shaped by experience, direct actions toward stimuli.

In today’s context, attitudes toward tourism destinations are shaped by past experiences, perceived value, and emotional connections, leading to recommendations or revisits [

87].

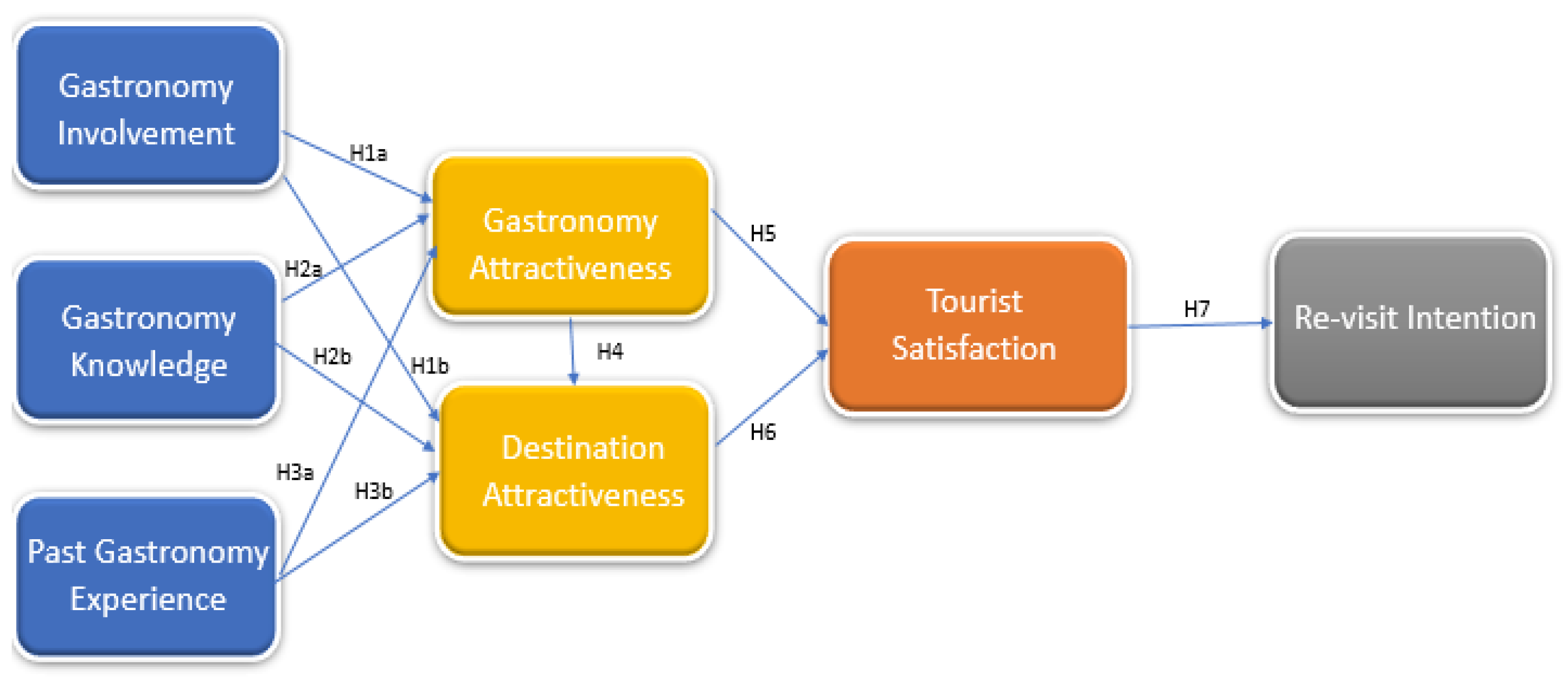

The proposed model demonstrating the hypothesized relationships is presented in

Figure 1.

3. Methodology

3.1. Collection of Data

Data were gathered from surveys conducted with 326 respondents between January 5, 2022, and April 22, 2022. After excluding incomplete responses, 300 valid surveys were used in this study. The survey included two sections: one for the main research variables and the other for demographic data and destination experiences.

Proper identification of the population is critical in scientific research since it determines the research criteria for the validity of the entire document. In this regard, the population was the 300 international tourists visiting the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). At the same time, a sample was drawn using the non-probability random sampling technique wherein the sample was selected by chance without using any predetermined methods and, at the same time, the population is not pre-defined. The survey was based on a 5-point Likert scale, wherein the responses ranged from (1) “Strongly Disagree” to (5) “Strongly Agree.” At the same time, 15 questions were included in the survey to capture the demographic characteristics and destination experiences of the respondents.

The questionnaire was served in English and Turkish. While adapting scales from another language, it is imperative that the translations should be in parallel with the language and culture of the sample group. The questionnaire was developed through a rigorous process, including item selection, translation by bilingual academics, back-translation for accuracy, and pre-testing. Constructs were measured using items adapted from previously published studies.

3.2. Data Analysis Methods

Analysis SPSS was employed to analyze the collected data. The first step taken was to determine the frequency of identification to obtain the demographic characteristics of the participants. Convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs was determined by use of CFA in relation to what Anderson and Gerbing [

88] proposed. The inter-construct relationships in the research model analyzed through CFA were done by using Pearson’s correlation analysis. CFA was also adopted to contribute to determining the construct validity in terms of reliability and the discriminant and convergent validity of the research model. This was because the measurement levels concept of Fornell and Larcker [

89] were used to do this. The estimates provided were taken based on the IFI and the normalized chi-square (χ²/df) from specified standards to determine the goodness-of-fit of the model.

3.3. Measurement

Several constructs were measured using items; the items were sourced from previously published empirical studies. Gastronomy Involvement (GI) was assessed using an 8-item scale adapted from Bell and Marshall [

90]. Gastronomy Knowledge-related attributes were measured using a 5-item scale adapted from Guan and Jones [

91]. Past Gastronomy Experience (PGE) was measured using a 4-item scale adapted from Kivela and Crotts [

26]. Gastronomy Attractiveness (GA) was evaluated using a 16-item scale adapted from Hu and Ritchie [

50]. Tourist Satisfaction (TS) was assessed using a 4-item scale adapted from Meng and Han [

92]. Revisit Intention (REI) was measured using a 3-item scale adapted from Han, Hsu, and Lee [

93].

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. The data shows that the participants were primarily female (29.0%), single (49.7%), high school graduates (0.7%), between the ages of 18 and 25 (34.7%), making between 1000 and 2500 USD per month and working in the private sector (32.8 %).

The sample represented the demographics of tourists in Northern Cyprus. In the study, the majority of participants are in the “2,500 $- 5,000 $” income level bracket (58.7%) and the “26-35” age group (40.7%).

4.2. Measure Reliability and Validity

In this research, the reliability and validity of the constructs were assessed using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Refinements to the model were made, leading to the achievement of satisfactory goodness-of-fit indices. The outcomes of the factor analysis are presented in

Table 2, which delineates the dimensions, items, factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE).

The table presents the measurement properties of various variables used in the study, including Involvement (I), Knowledge (K), Past Experience (PE), Gastronomy Attractiveness (GA), Destination Attractiveness (DA), Satisfaction (S), and Re-visit Intention (RE). Each variable’s measurement items show standardized loadings, indicating the strength of the relationship between the items and their respective constructs. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values, which measure the amount of variance captured by the construct versus the amount due to measurement error, range from .549 to .814, suggesting varying degrees of convergent validity. Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s Alpha (α) values, which assess the internal consistency of the constructs, generally exceed the threshold of .70, indicating good reliability. Notably, the CR and α values for most variables are above .80, confirming strong internal consistency, except for Past Experience (PE), which shows lower values. This comprehensive evaluation highlights the robustness of the measurement model in capturing the intended constructs effectively.

The internal consistency of the constructs was gauged using the CR. According to the reliability criteria, alpha coefficients are expected to exceed 0.7 to be acknowledged as exhibiting “high reliability” [

94,

95], while the CR values should surpass the 0.6 benchmark [

96]. The constructs within this study have surpassed these thresholds and are therefore regarded as reliable.

Moreover, factor loadings are recommended to exceed 0.5 to confirm internal consistency [

95], a standard that has been met by the constructs in this study.

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

SEM was used to investigate the proposed model. The model fit indices indicated a good match: χ²/df = 2.811, GFI = 0.872, AGFI = 0.839, NFI = 0.832, TLI = 0.865, CFI = 0.883, and RMSEA = 0.067. These indices meet the recommended thresholds, indicating a well-fitting model [

97].

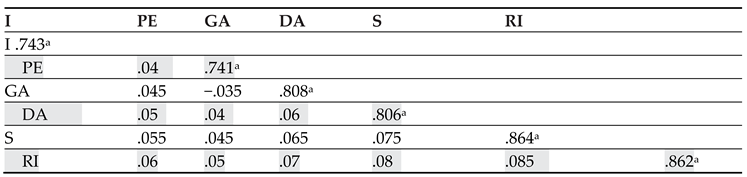

Table 3 effectively showcases the discriminant validity of the constructs within the model, with each construct demonstrating more variance with its indicators than with other constructs, a foundational principle for establishing the reliability and validity of a theoretical model in SEM analysis. Involvement (I) has a substantial relationship with itself, as expected, with a high square root of AVE value (.743), suggesting good internal consistency. Its correlations with other constructs are relatively low, indicating distinctiveness Past Experience (PE) and Gastronomy Attractiveness (GA) show negative correlations, which is unusual and may indicate inverse relationships or potentially issues within the dataset or model specifications. Satisfaction (S) and Re-visit Intention (RI) exhibit the highest square root of AVE values (.864 and .862, respectively), highlighting strong internal consistency. Their increasing correlations with other constructs, especially as we move from Involvement (I) to Re-visit Intention (RI), suggest these constructs have stronger relationships with others in the context of this model.

H1a and H1b: Gastronomy involvement (GI) positively influences both gastronomy attractiveness (GA) and destination attractiveness (DA). The results indicate that tourists’ engagement with gastronomic activities enhances their perception of the gastronomy’s appeal (β = .242, p < .01) and the overall allure of the destination (β = .263, p < .01). This underscores the pivotal role of active gastronomic engagement in enriching the tourism experience.

H2a and H2b: Gastronomy knowledge (GK) significantly impacts the attractiveness of gastronomy and the destination. The results show that informed tourists, or those with prior knowledge about local gastronomy, have a heightened appreciation for both gastronomic offerings (β = .257, p < .01) and the destination (β = .234, p < .01). This suggests that enhancing tourists’ knowledge about local cuisine can be a strategic tool in destination marketing.

H3a and H3b: Past gastronomy experiences (PGE) have a significant effect on the perceived attractiveness of gastronomy and the destination. The analyses validate these hypotheses, showing that positive past experiences with local cuisine significantly contribute to tourists’ current perceptions of gastronomy (β = .291, p < .01) and destination attractiveness (β = .265, p < .01). These findings highlight the lasting impact of memorable gastronomic experiences on tourist perceptions.

H4: The perceived attractiveness of gastronomy strengthens destination attractiveness. This hypothesis is strongly supported (β = .253, p < .01), highlighting the interdependence between gastronomy’s appeal and the broader appeal of the destination.

H5: Gastronomy attractiveness enhances travel satisfaction (TS). This was confirmed (β = .249, p < .01), indicating that satisfying gastronomic experiences are integral to overall travel contentment.

H6 and H7: Destination attractiveness (DA) directly influences tourist satisfaction and the intention to revisit or recommend the destination (REI). The findings affirm these links, with destination attractiveness significantly affecting tourist satisfaction (β = .286, p < .01) and their propensity to recommend the destination (β = .275, p < .01).

5. Conclusions

This study provides comprehensive insights into the pivotal role of gastronomy in enhancing tourist experiences and boosting destination attractiveness, specifically in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). It establishes that gastronomic involvement, knowledge, and past experiences are integral to shaping tourists’ perceptions and overall satisfaction. Tourists who actively engage with and possess prior knowledge about local cuisine are more likely to find the destination appealing and satisfying, which significantly influences their likelihood of revisiting or recommending the destination to others.

One of the key findings is the critical impact of positive past gastronomic experiences on tourists’ perceptions. These experiences are not just about the act of eating but involve a deeper, multidimensional engagement with the local culture, including learning about culinary traditions, participating in food-related activities, and experiencing the sensory aspects of local cuisine. Such interactions contribute to a more profound appreciation of the destination, enhancing the overall travel experience.

The study also reveals that gastronomic attractiveness has a substantial effect on overall travel satisfaction. Satisfying food experiences contribute significantly to tourists’ contentment with their trip, which in turn enhances their likelihood of returning to the destination or recommending it to others. This highlights the integral role of food in the broader tourism experience and underscores the importance of high-quality, authentic culinary offerings.

From a marketing perspective, these findings emphasize the value of incorporating gastronomic elements into destination promotion strategies. Highlighting local culinary attractions and providing educational content about local cuisine can effectively engage tourists seeking authentic and immersive experiences. Investments in developing and promoting gastronomic attributes, such as organizing food festivals, culinary tours, and cooking classes, can yield substantial benefits in terms of increased tourist satisfaction and destination appeal.

Moreover, the study underscores the importance of authenticity and quality in gastronomic offerings. Tourists are increasingly looking for genuine and memorable food experiences that reflect the local culture and traditions. By focusing on the authenticity and uniqueness of local cuisine, destinations can create a strong gastronomic identity that sets them apart from competitors.

The research also points to the need for destinations to adopt a holistic approach in their marketing and development strategies. Gastronomic tourism should be integrated with other cultural and recreational offerings to provide a comprehensive and attractive package for tourists. This integrated approach can enhance the overall appeal of the destination and contribute to higher levels of tourist satisfaction.

Additionally, the findings have important implications for destination management organizations. By focusing on enhancing the overall quality of the tourist experience, both gastronomic and non-gastronomic, destinations can ensure high levels of satisfaction and foster positive word-of-mouth recommendations. Seeking feedback from tourists and engaging them through social media and other platforms can also provide valuable insights into their preferences and help in tailoring offerings to meet their expectations.

This study highlights the significant potential of gastronomy tourism in enhancing tourist satisfaction and destination attractiveness. By offering authentic, high-quality, and engaging culinary experiences, destinations can attract and retain tourists, thereby contributing to the overall success and sustainability of the tourism industry. The research provides a framework for understanding the complex relationships between gastronomic factors and tourist behaviors, offering valuable insights for both theory and practice. Future research should explore these dynamics in diverse cultural and gastronomic contexts to further enrich our understanding of gastronomy tourism and its impact on the tourism industry.

6. Discussion

Eating is an essential need for tourists, setting it apart from other activities [

98]. Consequently, tourists always allocate part of their budget for food and beverages. When visiting a destination, tourists are likely to sample the local cuisine. Gastronomy plays a pivotal role in showcasing destination culture, as it is shaped by social, natural, and cultural influences, reflecting local traditions through unique culinary values [

99]. This culinary element attracts tourists eager to explore other cultures through local food and drink [

98]. Additionally, local gastronomy serves as a major draw for tourists and significantly impacts their overall experience [

1]. Therefore, establishing strong credibility in gastronomy tourism is crucial for enhancing tourist satisfaction and increasing visits [

80].

Investigating the phenomenon of gastronomic tourism in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) at the level of the relationships between gastronomic involvement, gastronomic knowledge, previous gastronomic experiences, and their impact on gastronomy and destination appeal significantly develops the existing literature and contributes to understandings of how tourist satisfaction and the intent to revisit or recommend are formed. The findings reveal several key insights into the role of gastronomy in tourism. First, gastronomic involvement and knowledge are crucial in shaping tourists’ perceptions of both the gastronomy and the destination itself. This suggests that tourists who actively engage with and have prior knowledge about local cuisine are more likely to find the destination appealing. This is consistent with modern tourism trends where travelers seek authentic and immersive experiences, often centered around local culinary traditions.

The positive impact of past gastronomic experiences further underscores the importance of providing memorable food-related experiences. Tourists with positive past interactions with local cuisine are more likely to view both the gastronomy and the destination favorably. This aligns with the concept that food experiences are not merely about consumption but are multidimensional, encompassing learning and sensory engagement with the local culture.

Moreover, the significant relationship between gastronomy attractiveness and overall travel satisfaction highlights the integral role of food experiences in the broader tourism experience. Satisfying gastronomic experiences contribute significantly to tourists’ overall contentment with their trip, which in turn enhances their likelihood of revisiting or recommending the destination.

From a destination marketing perspective, these findings emphasize the value of incorporating gastronomic elements into marketing campaigns. Promoting local culinary attractions can effectively engage tourists seeking authentic and deep cultural experiences. The results suggest that investments in developing and promoting gastronomic attributes can yield substantial benefits in terms of destination appeal and tourist satisfaction.

Nowadays, gastronomy is not a side feature of a travel experience. Instead, it can be defined as an independent aggregator of tourist activity, attracting considerable attention of travelers and motivating their choice of the destination [

100]. Such an approach to gastronomy is consistent with modern tourists’ preferences for deep and authentic experiences. According to Hall et al. [

101], tourists increasingly seek genuine experiences during their trips, which often direct them to a country’s culinary traditions. This understanding is also consistent with the current findings about the positive impact of both gastronomic involvement and knowledge on destination appeal[

102]. This research explores the factors influencing tourists’ consumption of local food and how these experiences enhance their perception of the destination.

The importance of these dimensions does not lie only in the consumption experience. As suggested by Bessière [

12] and further elaborated by Robinson and Getz [

2], local cuisines offer a broad sensory experience that facilities learning about the identity and traditions of a foreign culture. With reference to the studied framework, this idea encompasses the understanding that gastronomic tourism is a complex experience. This understanding refers to the notion that food experiences are multidimensional and include several dimensions beyond consumption [

103]. From this perspective, the proposed construct of gastronomic affection discussed in this research may be considered a new field of study. In this context, the developed framework of leisure specialization, normally applied to outdoor activities [

104,

105] but also enabled for the study of gastronomic tourism, explains how deep interaction with local food culture impacts expectations tourism. Thus, the study reveals the importance of creating memorable gastronomic experiences to improve destination appeal and tourist satisfaction.

From the domain of destination marketing, the developed insights associated with gastronomy are useful in proving the value of this image component. Specifically, the study emphasizes that marketing campaigns that integrate gastronomic attributes are more likely to engage customers searching for authentic culinary experiences [

6]. At the same time, the findings on the significant positive effects of food components present an additional reason to invest in the development and promotion of this component [

106].

Thus, the study can be supplemented with subsequent explorations of sustainability problems. Approaches may focus on how these local practices can be sustained and developed so that they contribute to both tourists and residents [

31,

107]. Secondly, the study can include a section on the importance of digital media to form personalities. From this approach, it is interesting to understand how the information represented in review platforms or social media affects the determination and behavior of tourists [

108,

109].

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Concretely, this research substantially adds to the body of existing knowledge of gastronomy tourism by building a more elaborate understanding of the multifaceted relationships that gastronomic involvement, knowledge, past experiences, attractiveness, and their combined impact create with destination attractiveness and tourist behavioral intentions. At a theoretical level, the applied framework extends the leisure specialization framework developed by McIntyre and Pigram [

105] and Bryan [

110] into the context of gastronomy tourism, highlighting how tourists’ affection for gastronomy-related involvement, knowledge, and past experiences shape perceptions and experiences within this realm. The implication is that the theoretical underpinnings of tourism studies are enriched by an illustration of the complexity of tourist behavior in the context of gastronomic tourism.

On the other hand, the inclusion of constructs such as gastronomy attractiveness and destination attractiveness in a larger framework also reveals the interdependent nature of these factors and their influence on tourist satisfaction and intentions to revisit or recommend. Such an approach also provides a more holistic view of the gastronomy tourism experience, highlighting the importance of destination appeal and tourist satisfaction. Finally, they indicate that conceivably affects tourist behavior is very wide and more detail understanding of them is required beyond that which realises the existing models, which focussed on singular aspects of the tourist experience.

6.2. Practical Implications

The insights from this research are useful for destination marketers and management organizations. Specifically, it has been shown that by promoting tourists’ gastronomic involvement and knowledge, their being more involved and knowledgeably involved has a positive and statistically significant impact on the attractiveness both of gastronomy and the destination. This suggests that the marketing of a destination should not only emphasize the uniqueness of the gastronomic experience to be had in the region but also provide educational information about local cuisine in general to engage potential visitors. To benefit from a positive impact of past gastronomic experiences, destinations should pay special attention to the creation of memorable and enjoyable culinary experiences. This may include different activities like food festivals, culinary tours, and cooking classes that will allow tourists to fully integrate into local gastronomic culture. Enhancing the quality of food service and emphasizing the authenticity and uniqueness of the local cuisine can further enhance gastronomy attractiveness.

Given that the gastronomic dimension has great importance in the potential attractiveness of a destination and the satisfaction of tourists, destinations should consider it as a fundamental pillar in the set of values that it projects globally. Within this programming, the gastronomic offering must be promoted in an integrated manner with other cultural and recreational tourist values, to constitute a global attractive offer. This study clearly reveals that tourist satisfaction plays a crucial role in impacting the intention to revisit the destination or recommend it to others. Destinations should thus pay attention to the overall quality of the tourist experience, both gastronomic and non-gastronomic, with the aim of ensuring high levels of satisfaction. Seeking feedback and involving tourists through social media and other platforms can also facilitate a better understanding of tourist preferences and help in offering improved experiences.

This research has important theoretical and practical implications for the field of gastronomy tourism. The work establishes a graspable and integrative structure that holds the potential of gastronomy in adding value to the attractiveness of the destination and the satisfaction of tourists through the relationships of various gastronomy-related factors with the impression of tourist perception and behavior.

6.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The study, although presenting interesting insights in how gastronomy tourism influences tourist behaviors and attractiveness at the destinations, is not exempt from the following limitations. Since the study focused predominantly on the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, the research findings may be inapplicable at other destinations facing different cultural or gastronomic landscapes. The study focused on large dimensions of gastronomy involvement, knowledge, and experiences, without capturing the analytic differences in the tourists’ gastronomy preferences or restrictions in their gastronomy, for example by dietary needs or ethical considerations.

Future research opportunities may provide for studies at varied destinations to offer a universal understanding of the gastronomy tourism dynamics. Second, some of the moderators in dietary preference, ethic food choice, and cultural influence on gastronomy tourism are likely roles that can give further insight and increase theoretical and practical value of the findings in different tourism contexts.

Author Contributions

T.G. completed the introduction and theoretical background sections. R.K. wrote the methodology and results sections. M.Ş. contributed to reviewing the recent literature and wrote the hypotheses development sections. All authors have written discussion parts and checked the last version of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Henderson, J.C. Food tourism reviewed. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.; Getz, D. Profiling potential food tourists: an Australian study. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 690–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. , & Avieli, N. (2004). Food in tourism: Attraction and impediment. Annals of tourism Research, 31(4), 755-778.

- Tsai, C. T. S., & Wang, Y. C. Experiential value in branding food tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2017, 6, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Civitello, L. (2011). Cuisine and culture: A history of food and people (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: an illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2003, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Unwto), U.N.W.T.O.; Blomberg-Nygard, A.; Anderson, C.K. United Nations World Tourism Organization Study on Online Guest Reviews and Hotel Classification Systems: An Integrated Approach. Serv. Sci. 2016, 8, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, N. (2012). Flavors of Modernity: Food and the Novel. Princeton University Press.

- Stanley, M. , & Stanley, T. (2015). The Science of Taste: Exploring the Culinary Mind. Oxford University Press.

- Guan, J.; Jones, D.L. The Contribution of Local Cuisine to Destination Attractiveness: An Analysis Involving Chinese Tourists' Heterogeneous Preferences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 20, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J. , & Horner, S. (2007). Consumer behaviour in tourism. Routledge.

- Bessière, J. Local Development and Heritage: Traditional Food and Cuisine as Tourist Attractions in Rural Areas. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Costello, C. Culinary tourism: Satisfaction with a culinary event utilizing importance-performance grid analysis. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.M. and Richards, G. (2002) Tourism and Gastronomy. London and New York: Routledge.

- Okumus, B.; Okumus, F.; McKercher, B. Incorporating local and international cuisines in the marketing of tourism destinations: The cases of Hong Kong and Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2006, 28, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, J. , & Tibère, L. (2018). Tourisme et expérience alimentaire. Le cas du Sud-Ouest français. Téoros. Revue de recherche en tourisme, 35(35, 2).

- Ahani, A.; Nilashi, M.; Ibrahim, O.; Sanzogni, L.; Weaven, S. Market segmentation and travel choice prediction in Spa hotels through TripAdvisor’s online reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Nicolau, J.L. Price determinants of sharing economy based accommodation rental: A study of listings from 33 cities on Airbnb.com. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 62, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. , & Marshall, S. (2013). Tourism and its impact on local communities: A study on the changing landscape. Journal of Tourism Studies, 22(4), 245-259.

- Chang, Y.-C.; Ku, C.-H.; Chen, C.-H. Using deep learning and visual analytics to explore hotel reviews and responses. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H., Scott, N., & Packer, J. (2020). Traveler food involvement and culinary tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 59(8), 1454-1468. [CrossRef]

- Sari, R.T.; Wirawan, P.E. Analysis on Promotion and the Influence of Social Media in Restaurant Industry, Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. J. Bus. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 3, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltescu, C. A. (2016). Culinary experiences as a key tourism attraction. Case Study: Brasov County. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Series V: Economic Sciences, 107-112.

- Björk, P. , & Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. (2020). Local food: A source for destination attraction. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(1), 367-384. [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Crotts, J.C. Tourism and Gastronomy: Gastronomy's Influence on How Tourists Experience a Destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 27.

- Lin, Y.-C.; Pearson, T.E.; Cai, L.A. Food as a form of Destination Identity: A Tourism Destination Brand Perspective. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A. , & Wall, G. (1982). Tourism, economic, physical and social impacts. Longman.

- Charters, S.; Ali-Knight, J. Who is the wine tourist? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Slocum, S.L. Food and tourism: an effective partnership? A UK-based review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçar, A.; Arisoy, M.; Çakiroglu, F.P.; Candar, S. Presence ofEnterobius vermicularisinfections and food hygiene knowledge levels among catering industry personnel. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauer, B. Conceptualizing special interest tourism—frameworks for analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trupp, A.; Sunanta, S. Gendered practices in urban ethnic tourism in Thailand. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 64, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.D. Koçbek. Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in Food and Beverage Sector: A Research on Ethnic Restaurants Anadolu University Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Business Administration, Master’s Thesis, Eskişehir (2005).

- Y. Bilgin. The effect of service quality, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty on word-of-mouth marketing in restaurant businesses J. Bus. Res., 9 (4) (2017), pp.

- Y. Bilgin, Ö. Kethüda The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction and loyalty in restaurant businesses: the case of oba restaurant Journal of Çankırı Karatekin University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, 7 (2) (2017), pp.

- Bengül, S. ; Güven, Z. The Effects of Physical Environment Quality, Food Quality and Service Quality on The Perceived Value, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty in Food and Beverage Businesses. 2019, 22, 375–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Yalçınkaya. The Effect of Dining Experience Service Quality Perception on Customer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions: The Case of Çanakkale Province Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli University Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Tourism Management, Nevşehir (2020).

- E. Yalçın. The Effect of Food and Service Quality and Restaurant Image on Price, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty, the Effect of Food and Service Quality and Restaurant Image on Price, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty Ankara Hacı Bayram Veli University Institute of Postgraduate Education, Department of Gastronomy and Culinary Arts, Ankara (2021).

- H. Ceviz, E. Erul, A. Uslu. A comparative study of the effects of hotel and restaurant customers’ behavior on image, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Journal of Gastronomy, Hospitality, and Travel, 5 (1) (2022), pp. 193-210.

- M. Bayram, H. Burgazoğlu, S. Hızal, A. Gülden. The role of customer satisfaction between food and beverage service quality and brand loyalty and brand image MANAS Journal of Social Research, 12 (1) (2023), pp. 224-239.

- M. Kaşlı, B. Demirci, Ü. Kement. The effect of gastronomic experiences on revisit intention the case of Eskişehir. Presented at the 15th National Tourism Congress (2014) (Ankara).

- S. Eren, Ö. Demir. A research on the relationship between the use of traditional desserts in touristic restaurants and online gastronomy image and gastronomy experience. Presented at the 4th International Gastronomy Tourism Research Congress, vol. 128 (2019).

- B. Kaçar, A. Yarış. The effect of gastronomy experience elements on revisit intention. Journal of Tourism & Gastronomy Studies, 10 (3) (2022), pp. 2713-2734.

- Bi̇lgi̇li̇, R.; Koçoğlu, C.M. GASTRONOMİ ÇEKİCİLİĞİNİN GASTRONOMİ DENEYİMİ VE TEKRAR ZİYARET ETME NİYETİ ÜZERİNDEKİ ETKİSİ: AMASYA ÖRNEĞİ (THE EFFECT OF GASTRONOMY ATTRACTIVENESS ON GASTRONOMY EXPERIENCE AND REVISIT INTENTION: THE CASE OF AMASYA). J. Gastron. Hosp. Travel (JOGHAT) 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Şahin, S. S. Şahin, S.İ. Şahin, K. Koçak. The effect of physical evidence and gastronomy experience on satisfaction: a research in diyarbakır. Journal of Academıc Tourısm Studıes, 4 (2) (2023), pp. 82-98.

- B.Z. Hüsem, Ü. Kement, A. Şengöz. The effect of destination image and gastronomic experience on destination loyalty: the case of ayvalık. Ahi Evran University Journal of Institute of Social Sciences, 9 (3) (2023), pp. 840-859.

- Hu, Y.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Measuring Destination Attractiveness: A Contextual Approach. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L., & Kim, C. (2003). Destination competitiveness and bilateral tourism flows between Australia and Korea. Journal of tourism studies, 14(2), 55-67.

- Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. Harvard Business Review, 68(2), 73-93.

- Gunn, C. A. (1994). Tourism Planning: Basics, Concepts, Cases. Routledge.

- Formica, S.; Uysal, M. Destination attractiveness based on supply and demand evaluations: An analytical framework. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Huang, R.-J.; Zhang, R.; Tie, X.; Li, G.; Cao, J.; Zhou, W.; Shi, Z.; Han, Y.; Gu, Z.; et al. Severe haze in northern China: A synergy of anthropogenic emissions and atmospheric processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 8657–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World economic forum 2019: globalization 4.0–A better version. Strategic Impact, (72+ 73), 79-82.

- Brillat-Savarin, J. A. (1825). The Physiology of Taste: Or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, trans. MFK Fisher, New York, Everyman’s Library.

- Anderson, J. R. (2005). Gastronomy and Culinary Arts: Exploring Food Culture. Culinary Press.

- Parker, C.; Mathews, B.P. Customer satisfaction: contrasting academic and consumers’ interpretations. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2001, 19, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin Jr, J. J. , & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. Journal of marketing, 56(3), 55-68.

- Horng, J.; Tsai, C. (. Culinary tourism strategic development: an Asia-Pacific perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 14, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., & Huang, S. (2016). The impact of leadership styles on employee engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 123-135.

- Rust, R. T. , & Oliver, R. L. (2000). Should we delight the customer?. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28, 86-94.

- Meler, M.; Cerovic´, Z. Food marketing in the function of tourist product development. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.J.; Brown, G. An empirical structural model of tourists and places: Progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; López-Guzmán, T. Gastronomy as a tourism resource: profile of the culinary tourist. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of marketing, 60(2), 31-46.

- Bigné, J.E.; Sánchez, M.I.; Sánchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behaviour: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Sánchez, I.; Andreu, L. The role of variety seeking in short and long run revisit intentions in holiday destinations. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 3, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.K.; Wan, D.; Ho, A. Tourists’ satisfaction, recommendation and revisiting Singapore. Tour. Manag. 2006, 28, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist Satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an Off-Season Holiday Destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Mekker, M.; De Vos, J. Linking travel behavior and tourism literature: Investigating the impacts of travel satisfaction on destination satisfaction and revisit intention. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babolian Hendijani, Roozbeh. “Effect of food experience on tourist satisfaction: the case of Indonesia.” International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 10.3 (2016): 272-282.

- Joo, Dongoh, et al. “Destination loyalty as explained through self-congruity, emotional solidarity, and travel satisfaction.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45 (2020): 338-347.

- Loi, L.T.I.; So, A.S.I.; Lo, I.S.; Fong, L.H.N. Does the quality of tourist shuttles influence revisit intention through destination image and satisfaction? The case of Macao. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 32, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, D.; Solano-Sánchez, M. .; López-Guzmán, T.; Moral-Cuadra, S. Gastronomic experiences as a key element in the development of a tourist destination. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 25, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunel, M.C.; Erkurt, B. Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humagain, P.; Singleton, P.A. Exploring tourists' motivations, constraints, and negotiations regarding outdoor recreation trips during COVID-19 through a focus group study. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 36, 100447–100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutiadiningsih, A.; Mahfud, T.; Dang, V.H.; Purwidiani, N.; Wati, G.R.; Dewi, I.H.P. THE ROLE OF GASTRONOMY TOURISM ON REVISIT AND RECOMMENDATION INTENTIONS: THE MEDIATION ANALYSIS OF TOURIST SATISFACTION. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 52, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Tsai, D.C. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining Future Travel Behavior from Past Travel Experience and Perceptions of Risk and Safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 798-844). Clark University Press.

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The Role of Emotions in Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C. , & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological bulletin, 103(3), 411.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Bell, R.; Marshall, D.W. The construct of food involvement in behavioral research: scale development and validation☆. Appetite 2003, 40, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X., & Jones, T. (2015). The culinary art and science of modern gastronomy. Journal of Culinary Arts and Sciences, 10(3), 145-159.

- Meng, B.; Han, H. Working-holiday tourism attributes and satisfaction in forming word-of-mouth and revisit intentions: Impact of quantity and quality of intergroup contact. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.J.; Lee, J.-S. Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry Hinton, D. , Hinton, P. R., McMurray, I., & Brownlow, C. (2004). SPSS explained. Routledge.

- Hair, J. F. , Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16, 74-94.

- Schumacker, R. E. , & Lomax, R. G. (2016). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Kumar, G.M.K. Gastronomic tourism- A way of supplementing tourism in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 16, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordin, V.; Trabskaya, J.; Zelenskaya, E. The role of hotel restaurants in gastronomic place branding. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. , & Park, E. (2016). Exploring the role of food tourism in destination branding: A case study of Seoul, Korea. Journal of Tourism Studies, 28(2), 123-139.

- Hall, C. M. , & Sharples, L. (2003). The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In C. M. Hall, L. Sharples, & R. Mitchell (Eds.), Food Tourism Around The World. Routledge.

- Kim, S. , Eves, A., & Scarles, C. (2009). Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(3), 423-This research explores the factors influencing tourists’ consumption of local food and how these experiences enhance their perception of the destination.

- Kim, Y.G.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Shafer, C.S. Recreational Specialization: A Critical Look at the Construct. J. Leis. Res. 2001, 33, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.; Pigram, J.J. Recreation specialization reexamined: The case of vehicle-based campers. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.N.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A.; Chang, R.C.Y. The effects of food-related personality traits on tourist food consumption motivations. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “war over tourism”: challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I. P. , & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2009). Mediating tourist experiences: Access to places via shared videos. Annals of tourism research, 36(1), 24-40.

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a Scale to Measure Memorable Tourism Experiences. J. Travel Res. 2010, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, H. Leisure Value Systems and Recreational Specialization: The Case of Trout Fishermen. J. Leis. Res. 1977, 9, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).