1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a commensal and opportunistic pathogen that extensively contributes to hospital-acquired infections worldwide. The WHO has listed on the class-2 priority list of pathogens and grouped it among serious bacterial pathogens known as ESKAPE [

1]. The growing challenge posed by multi drug-resistant bacteria such as methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) demands new agents or alternative therapy (such as combination). It’s becoming increasingly difficult to develop new antibiotics, and the emergence of drug-resistance to last resort of antibiotics calls for urgent attention to tackle methicillin-resistant

S. aureus (MRSA) strains [

2]. Combination therapy has received a lot of attention in the effort to resensitize bacteria that are resistant to traditional or clinically used antibiotics [

2,

3,

4].

There are multiple resistance mechanisms involved in drug-resistant

S. aureus [

5]. As a first line of defense mechanism, the

S. aureus genome encodes several transporters that efflux noxious compounds to detoxify cells [

6]. Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) proteins such as NorA, NorB, NorC contribute extensively to confer fluoroquinolone resistance (e.g., Norfloxacin), and to dye

s such as ethidium bromide in

S. aureus [

6]. The other transporters proteins that are involved in NOR resistance are MdeA, SdrM of MFS family, and MepA of the toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family, however, their specificity to fluoroquinolones is weak [

6,

7]. Other mechanism attributing drug resistance in

S. aureus includes enzymatic inactivation of the antibiotics (e.g., penicillinase), target alteration (e.g., resistance to methicillin by expression of a novel penicillin-binding protein, PBP-2a, a product of

mecA gene), and mutations in the cellular targets (e.g., mutant topoisomerase and DNA gyrase for fluoroquinolone resistance, and

rpoB gene for rifampin resistance) [

5,

8].

Natural molecules with antimicrobial activity and synergistic properties can be promising alternatives that can help repurpose old drugs that have become ineffective due to the gain of drug-resistant mechanisms in bacteria. Usnic acid (UA) is a secondary metabolite found in Lichens sp. and present in two natural enantiomers, (+)− or (−)−, and exerts antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antiviral activity, as well as anti-cancer activity [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, the molecular mechanism of antibacterial action requires further investigation. Hence more studies are required to decipher underlying molecular mechanisms of antibacterial and synergistic activity to find precise targets to develop alternative therapeutics.

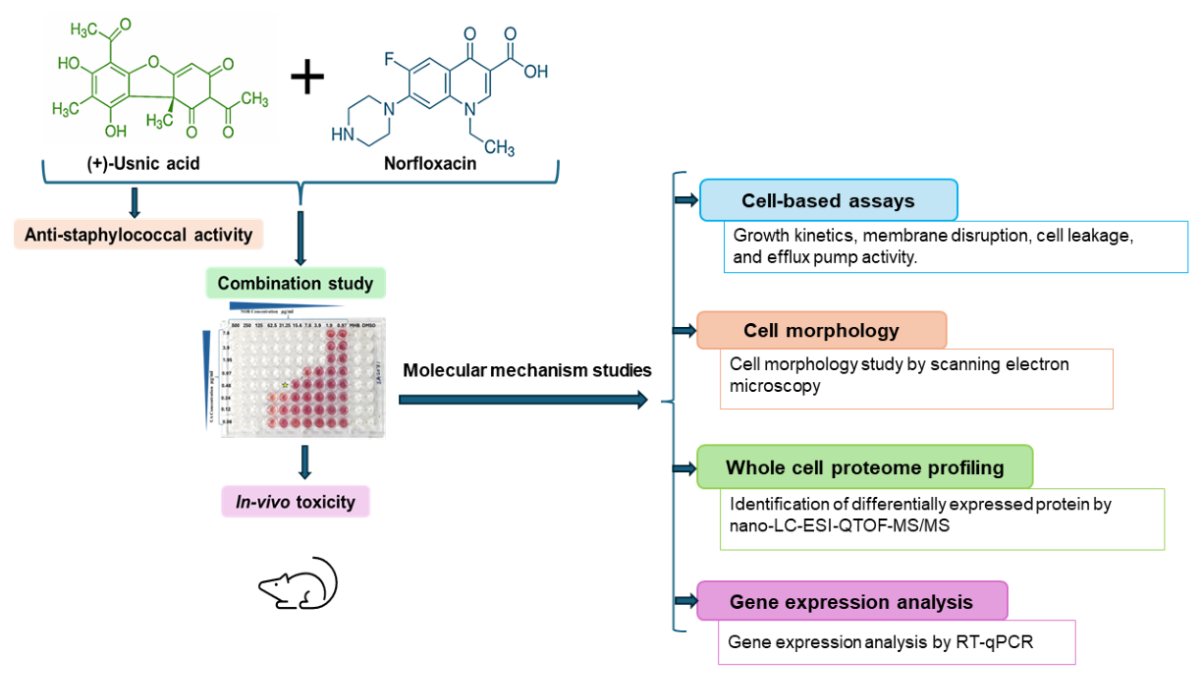

In this work different cell-based assays, gene expression analysis, and whole-cell proteome analysis were performed to delineate the molecular mechanism of anti-staphylococcal activity of UA as well as synergy mechanism with NOR. In addition, an in-vivo study was undertaken to assess the toxicity and efficacy of UA using Swiss-albino mice model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Culture Conditions, Chemicals, and Enzymes

S. aureus reference strain MTCC 96 (ATCC 9144) and MRSA clinical isolates [

15,

16] were maintained and cultured in standard Mueller-Hinton agar and cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth media (MHA and CAMHB, Hi-Media, Mumbai, India). UA, NOR, iodonitrotetrazolium chloride, phosphate-buffered saline, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), thiourea, and lysostaphin was procured from Sigma- Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States). UA stock solution (2 mg/mL) was prepared in DMSO. Trypsin Gold of mass spectrometry grade was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, United States). Taq DNA polymerase, cDNA synthesis kit, and SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

2.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC)

MIC of UA and clinically used antibiotics (of various classes) were evaluated against MRSA clinical isolates [

16] using the broth microdilution assay as per CLSI guidelines (CLSI, 2018). DMSO was used as a control.

S. aureus MTCC 96 (ATCC 9144) was used as a reference strain.

2.3. In-Vitro Synergy of UA with Different Antibiotics

The Checkerboard method was used as described previously [

17]. Briefly, UA was tested in combination with various groups of antibiotics including beta-lactams (Oxacillin, Cefoxitin, Cefazolin), fluoroquinolone (Norfloxacin, Ciprofloxacin), protein synthesis inhibitors (Tetracycline, Erythromycin, Streptomycin), and glycopeptide (Vancomycin) against MRSA clinical isolates. Assay was performed using sterile 96-well ‘U’-bottom plates (Genaxy, USA). Antibiotics ranging from 1000 to 7.8 µg/mL were used in combination with UA (7.8 to 0.03 µg/mL) in a two-fold serial dilution. In addition, each well, except for the negative control, was inoculated with a bacterial culture of 5 × 10

6 CFU (colony-forming units)/mL (exponential growth phase) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) was calculated as follows: FICI = FIC of drug A + FIC of drug B (FIC

A MIC of drug A in combination/ MIC of drug A alone, and FIC

B= MIC of Drug B in combination/ MIC of Drug B alone). The FICI was interpreted as follows: ≤ 0.5 Synergy; >0.5-1.0 additive; >1.0 to <4.0 No interaction; and >4.0 Antagonism [

18].

2.4. Growth Kinetics Study of MRSA 2071

Growth kinetics was performed to assess the effect of NOR, UA, and in- combination NOR+UA on a clinical isolate of MRSA 2071 as per the method described previously [

16].

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

MRSA 2071 cells were treated with 1/2 MIC of NOR, UA, and a combination of UA+NOR and were cultured grew mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6) at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm). Samples were prepared as described previously [

16]. Samples were gold coated with a Q150TES sputter coater (Quorum Technology, UK) and observed by a Scanning Electron Microscope (FEI Quanta 250 FEG-SEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.6. Cytoplasmic Leakage Assay

MRSA 2071 was cultured in 25 mL MHB and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h with shaking (200 rpm). After incubation, the bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Cell pellets were washed twice and resuspended in sterile normal 1X PBS. Cells concentration adjusted to ~106 CFU/mL. Suspensions of bacterial culture were challenged with different concentrations of NOR alone, UA alone, and the combinations of NOR+UA (1/2MIC to 4MIC, each) except control (only cells). Suspensions were shaken for 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min at 37 °C. The absorbance of supernatants was measured at 260 nm and 280 nm using a spectrofluorometer (FLUOStar Omega BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany).

2.7. Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) Efflux Assay

To identify the role of efflux-mediated drug resistance in MRSA 2071, the fluorometric determination of ethidium bromide (EtBr) efflux was performed as per the method described elsewhere [

19]. See supplementary details.

2.8. Relative Expression of Efflux Pump Genes

First, the inducibility of NOR (1/2MIC, 1/4MIC, 1/8MIC, and 1/16MIC) on the transcript (mRNA) levels of efflux pumps related genes

norA, norC, mdeA, and

abcA was analysed in cells grown for mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6) at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm) in presence of different concentration. The relative expression (RQ) of target genes of interest were analysed using

∆∆Ct values compared to untreated control as described earlier [

16]. UA, and combination UA+NOR on the gene expression of efflux transporters was carried out under similar conditions.

2.9. Proteome Profiling for Identification of Differentially Expressed Protein by Nano-LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS

Protein extraction was performed from the cells grown (MRSA 2071) with and without treatments with NOR (1/4 MIC of NOR alone), UA (1/4 MIC of UA alone), and a combination of UA+NOR (1/4 MIC of combination) in 25 ml flasks for mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6) at 37 °C with shaking (200 rpm). (extraction method is provided in supplementary file) [

20]. Trypsin digestion and protein identification was performed as described earlier [

16,

21].

2.10. Validation of Identified Protein through RT-qPCR

Expression levels of the differentially expressed proteins found on MRSA 2071 exposed to NOR (1/4 MIC), UA (1/4 MIC), and NOR+UA (1/4 MIC of combination) using gene-specific primers

(Table 4) as described previously [

14]

2.11. Effect of Thiourea on Survival of MRSA 2071

Pre-grown overnight cells were inoculated (~ 106 CFU/mL) in fresh sterile MHB media (with and without thiourea added), and a set of cultures were challenged with different concentrations of UA, NOR, and UA+NOR (1/4MIC to MIC, each). The cultures were incubated for 12 h at 37 °C in shaking, and optical density (OD600 nm) was measured every 1 h with a 96-well microplate reader (Thermo, USA). Each test was carried out in triplicate, averaged, and graphed using OD600 nm on the Y-axis, and time on the X-axis.

2.12. In-Vivo Efficacy Using Swiss Albino Mice Model

UA alone (2 mg/kg body weight), and NOR alone (5 mg/kg body weight) and in the combinations of NOR+UA (5+2 mg/kg body weight) was tested, and a positive control (vancomycin 1 mg/kg body weight) and a negative control (vehicle) were included (n=5). The infection was accomplished through the intra-venous (i.v.) route with 1×10

6 CFU/mL of

S. aureus (MTCC 96). The mice were sacrificed after 7 days of therapy to determine the microbial load per gram of spleen and liver tissue using the plate dilution method followed by Gupta et al, 2012 [

15].

2.13. In-Vivo Toxicity Assessment of UA

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) test guideline No. 423 was followed to evaluate

in-vivo toxicity in Swiss albino mice [

15]. Doses of UA, NOR, and a combination of NOR+UA was administered as above. Blood was collected for various physiological and biochemical markers after the animals were examined for body weight changes. The animals were sacrificed to perform large organ necropsy and the calculation of relative organ weights. Biochemical changes were examined by the method followed by Gupta et al, 2012 [

15].

2.13.1. Ethical Clearance

The ethical clearance was received by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee under the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experimentation on Animal (CPCSEA) Ministry of Environment, Government of India. In this study, Swiss albino mice were chosen only when necessary. Approved protocol number by the animal ethics committee of the institute for various in-vivo testing were (i) In-vivo efficacy- CIMAP/IAEC/2016-19/07, and (ii) In-vivo toxicity- CIMAP/IAEC/2016-19/01.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel 365 and GraphPad Prism software. The controls and test data were acquired in triplicates and expressed in the form of mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (ns, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 control vs treatment).

3. Results

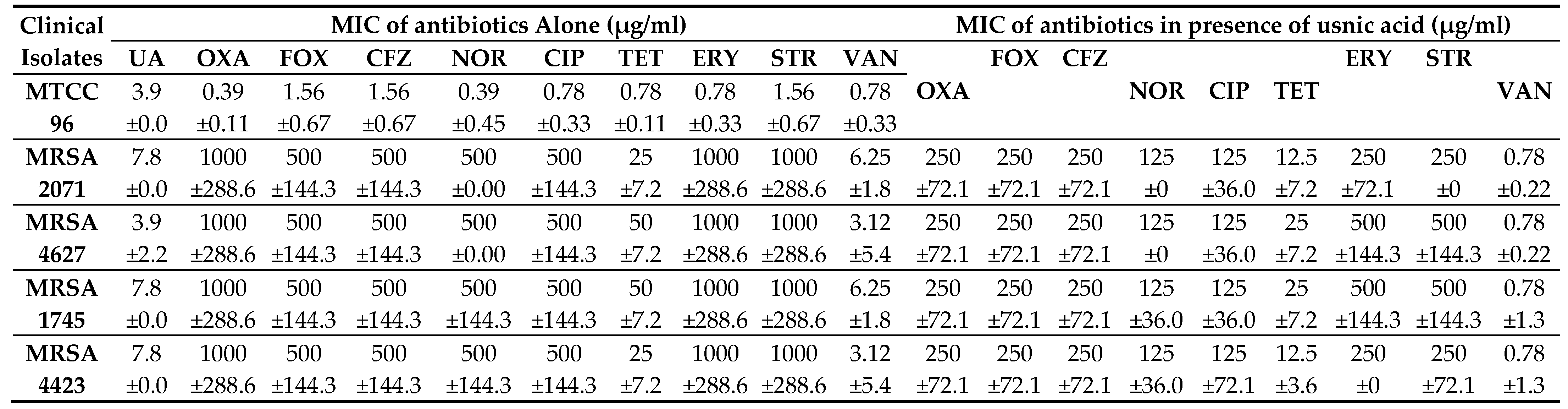

3.1. Anti-Staphylococcal Activity of UA and Its Synergy with Antibiotics

MIC of UA was found to be 7.8 µg/ml against MRSA clinical isolates and 3.9 µg/ml against a drug-sensitive strain, MTCC 96 (

Table 1). In combination study, UA in combination with NOR (NOR+UA) showed synergistic interaction against all MRSA clinical isolates and reduced MICs by 4-fold. (

Table 1). UA reduced the MIC by 2-4 folds of Oxacillin, Cefoxitin, Cefazolin, Ciprofloxacin, Tetracycline, Erythromycin, Streptomycin, and by 4-8 folds of Vancomycin (

Table 2). The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) was calculated to identify whether the interactions of UA with the various tested antibiotics are synergistic or additive (

Table 2). It was found that the combination of NOR+UA showed synergy against all MRSA clinical isolates, therefore the combination of NOR+UA was considered for further study.

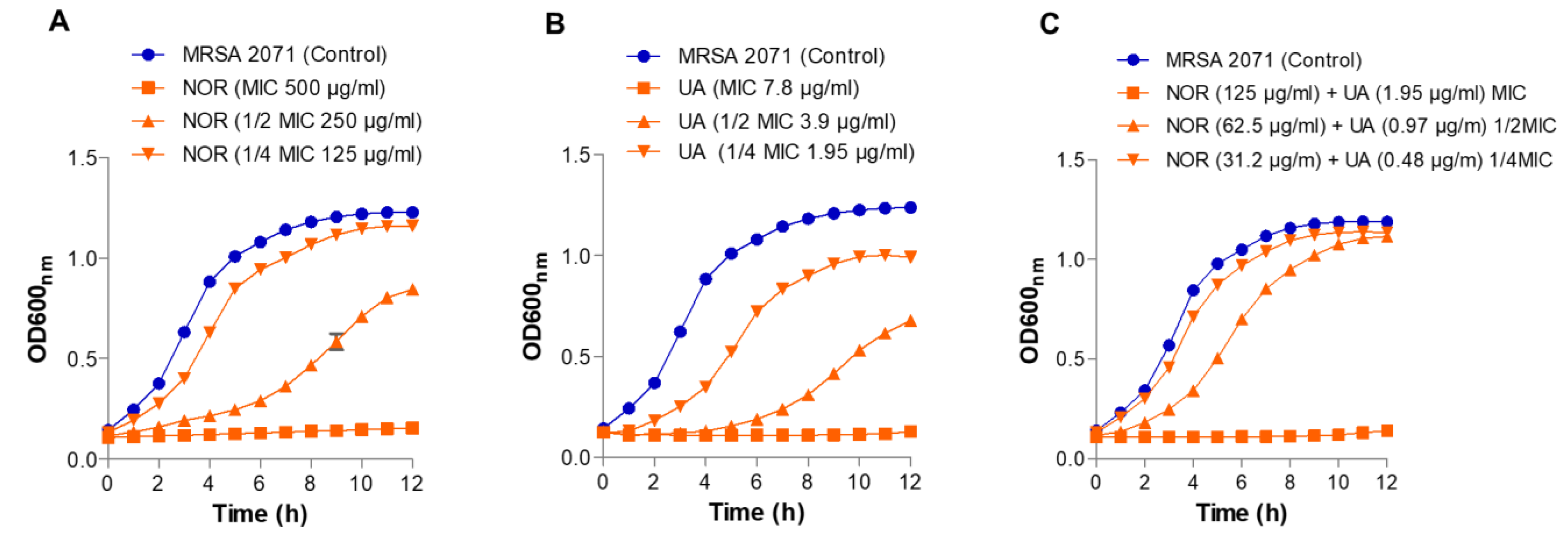

3.2. Growth Kinetics Study

As expected, there was no growth observed in MRSA 2071 at MIC levels of both UA and NOR (

Figure 1). Sublethal doses (1/2 MIC and ¼ MIC) of both UA and NOR partially inhibited growth and increased the lag period of MRSA 2071 in a dose-dependent manner compared to untreated cells. In combination, NOR+UA required only ¼ MIC levels of both UA and NOR alone to completely inhibit the growth of MRSA 2071 (

Figure 1).

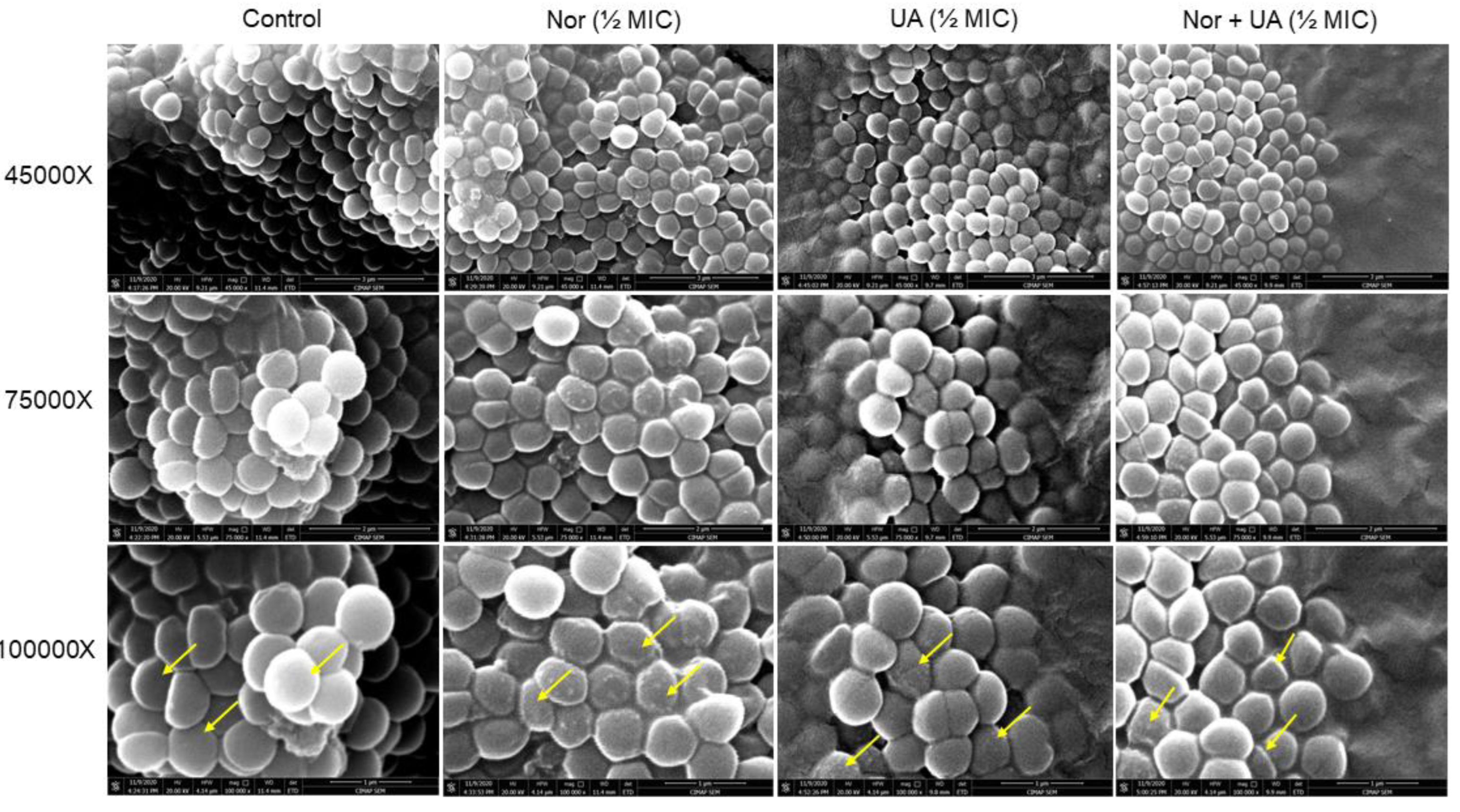

3.3. Cell Morphology Study by Scanning Electron Microscopy

UA treatment showed the development of rough cell morphology however, the observed effect was subtle than NOR treatments (

Figure 2). The combination of both NOR+UA also showed rough cell morphology which indicated a possible membrane damage/cell leakage of cells in presence of treatments.

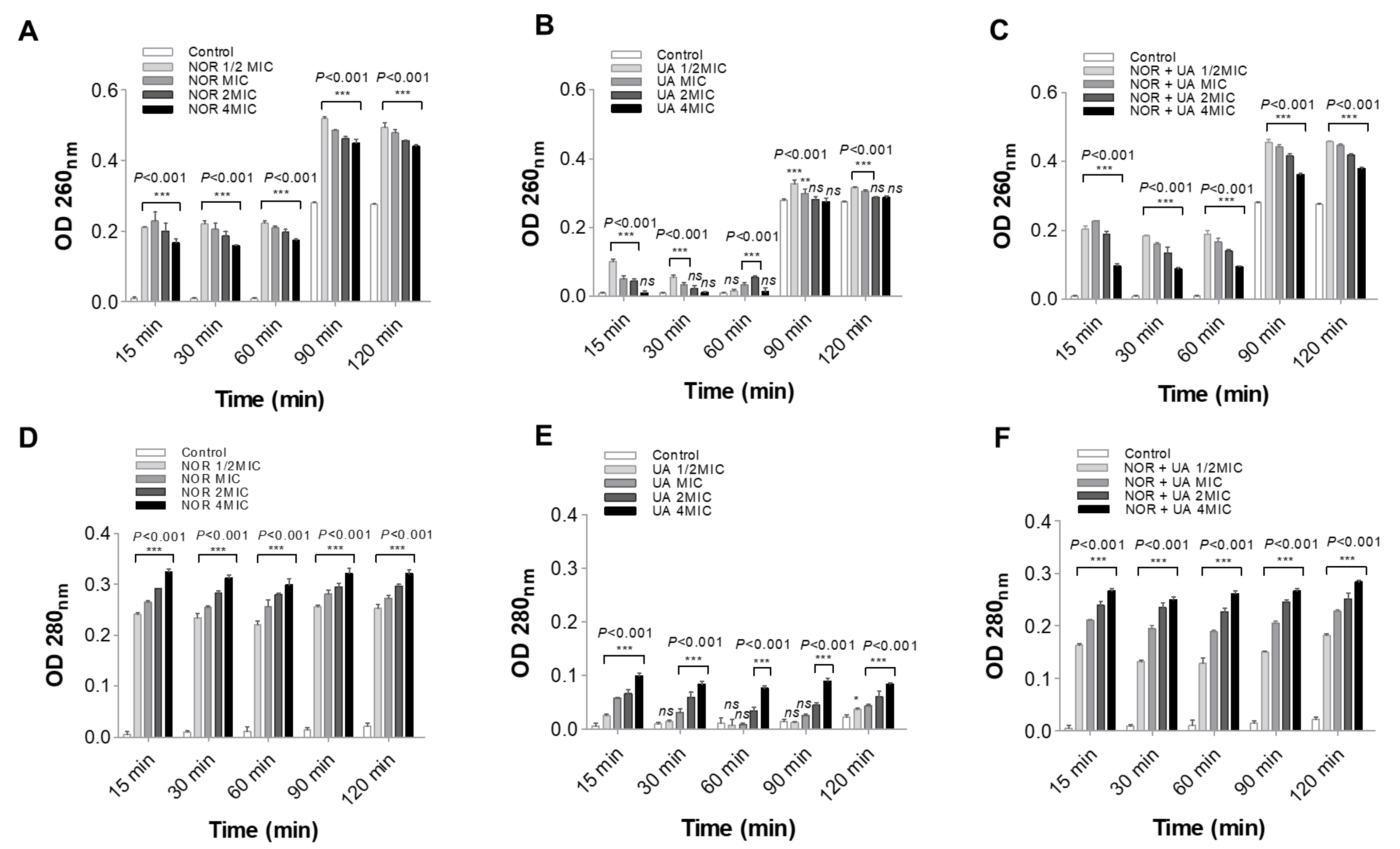

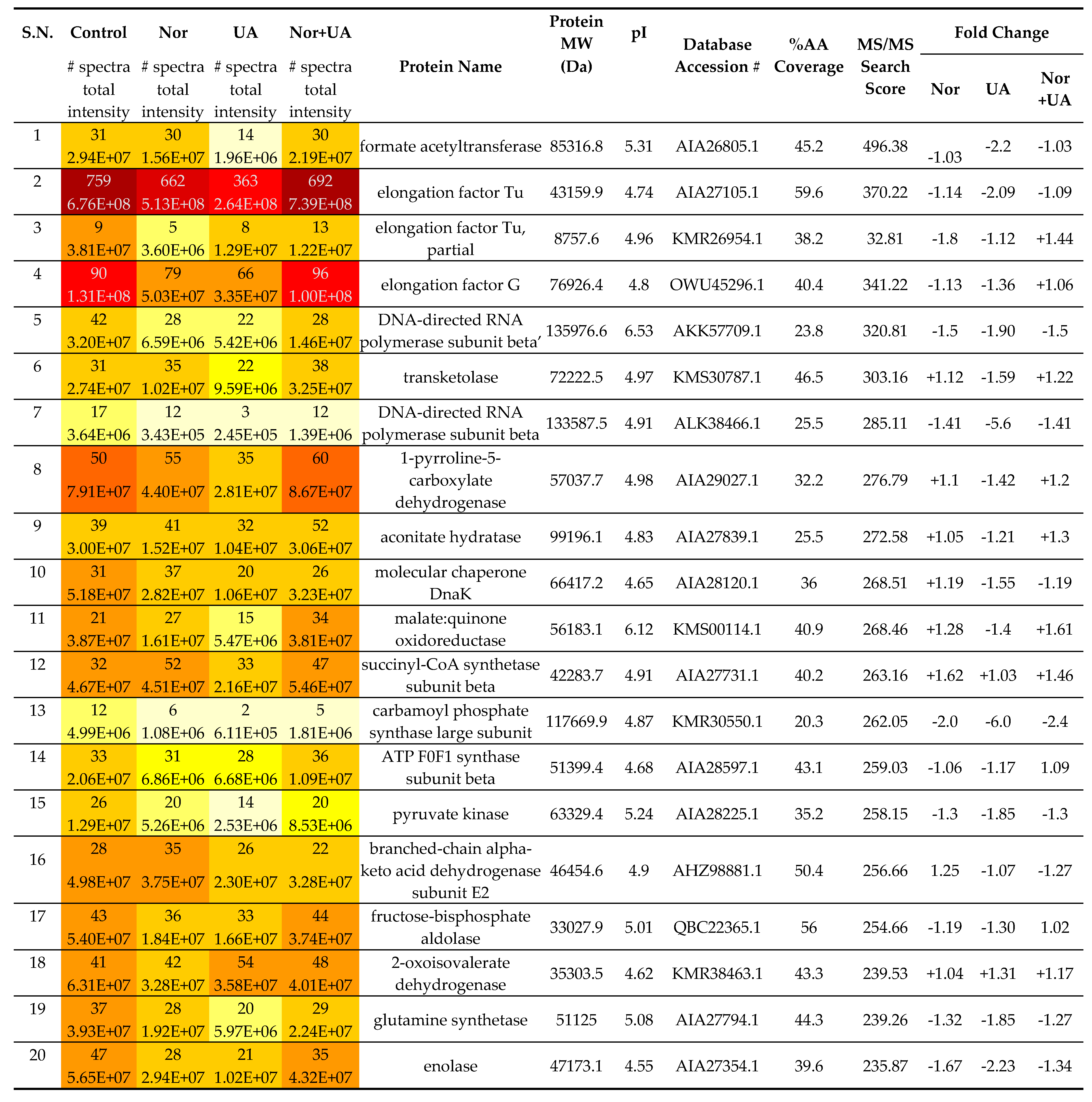

3.4. Cell Leakage Assay

NOR and UA caused leakage of cellular components (protein and nucleic acid) in the medium was found higher in treatment sets than control samples (

Figure 3). Similarly, the combination of NOR+UA also led to leakage of cell contents.

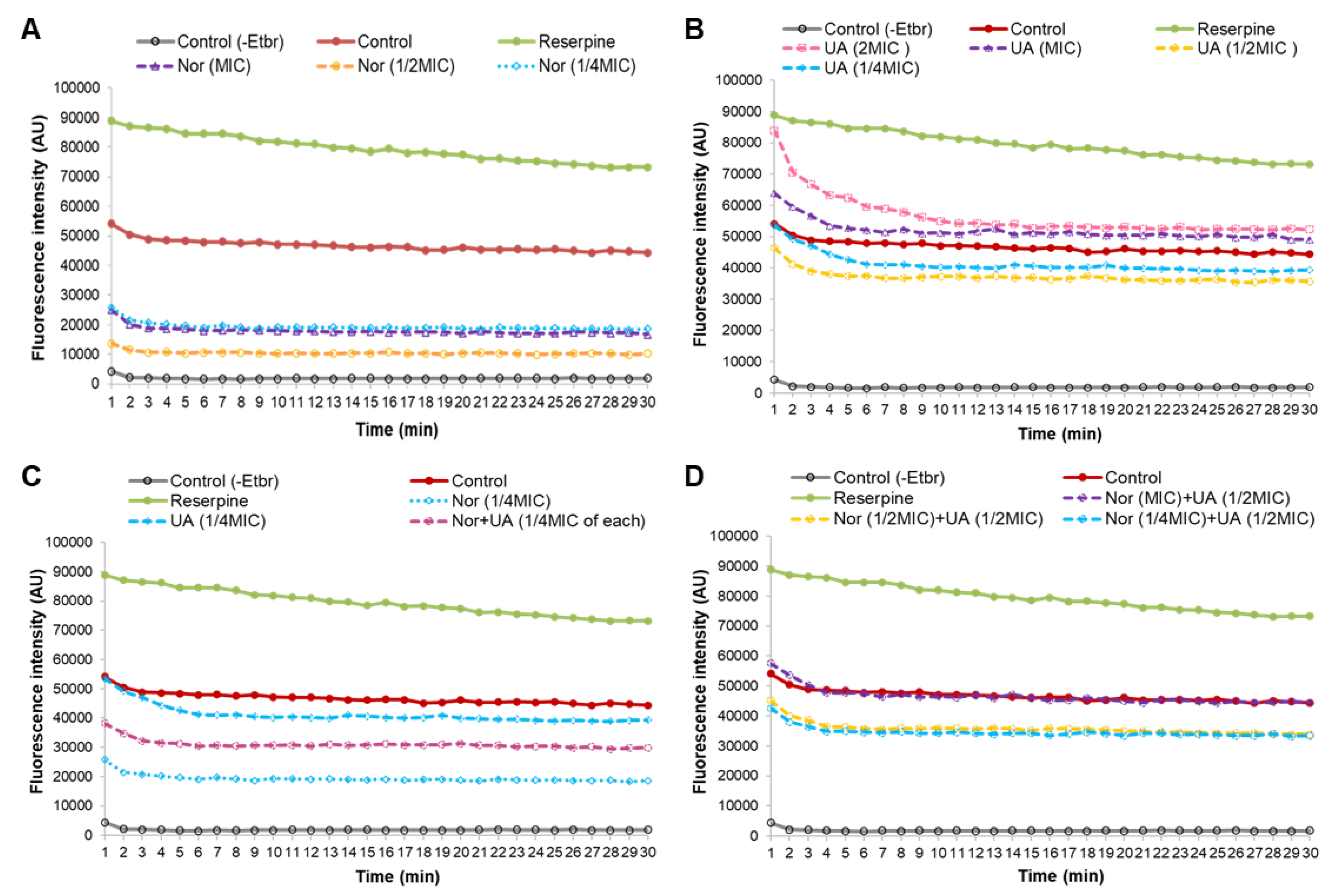

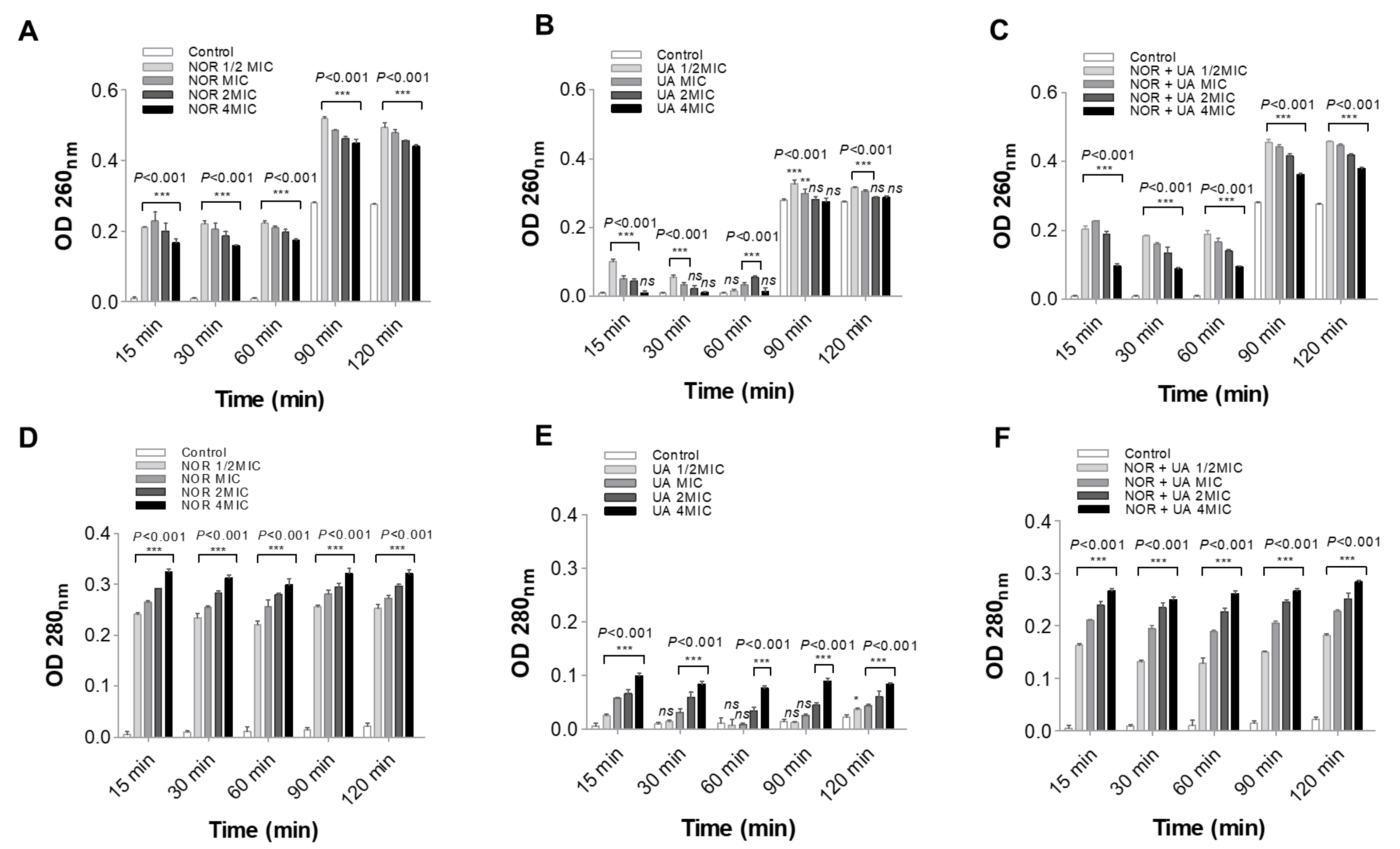

3.4. Efflux Pump Assay

EtBr fluorescence measurements found that treatment of MRSA 2071 with EtBr (+EtBr control) can produce fluorescence compared to non-treated samples (-EtBr control) (

Figure 4A). Reserpine, a well-known efflux pump inhibitor, was used as positive control which showed higher fluorescence in comparison to the EtBr control (+EtBr) (

Figure 4A). Sublethal concentrations of NOR (1/4 MIC, for 1 h) showed a decrease in fluorescence as compared to control (+EtBr), which suggests that NOR can induce efflux pump activity in MRSA 2071. Further decreased fluorescence or in other words enhanced efflux activity (~2 folds) was detected when the concentration of NOR was increased to ½ MIC. However, increasing NOR concentration to MIC and 2MIC did not increase the efflux activity further, yet surprisingly slightly reduced efflux activity as observed fluorescence was increased compared to ½ MIC of NOR. It suggests that NOR at sublethal (1/4 MIC and ½ MIC) induces an efflux system but a lethal concentration of NOR (MIC and 2MIC) damages the efflux pump proteins activity (

Figure 5A).

UA (1/4 and ½ MIC, 1 h) slightly induced efflux activity. However, inducibility in efflux activity due to UA was found to be much lower compared to NOR treatment (

Figure 4B). Importantly, it was observed that increased concentration of UA (MIC and 2 MIC) strongly inhibited efflux activity (

Figure 4B). These findings suggest that UA, above a critical concentration, potentially damages or blocks efflux-pump activity. Efflux study in combination (NOR+UA) clearly showed that UA is able to decrease the NOR dependent induced efflux pump activity as a higher fluorescence was observed in cells treated with UA+NOR at ¼ MIC of combination (

Figure 4C). Further UA (1/2 MIC) was able to completely neutralize the inducible effect of NOR (MIC) on efflux pump action, as the observed fluorescence was reversed back to the level of control (

Figure 4D).

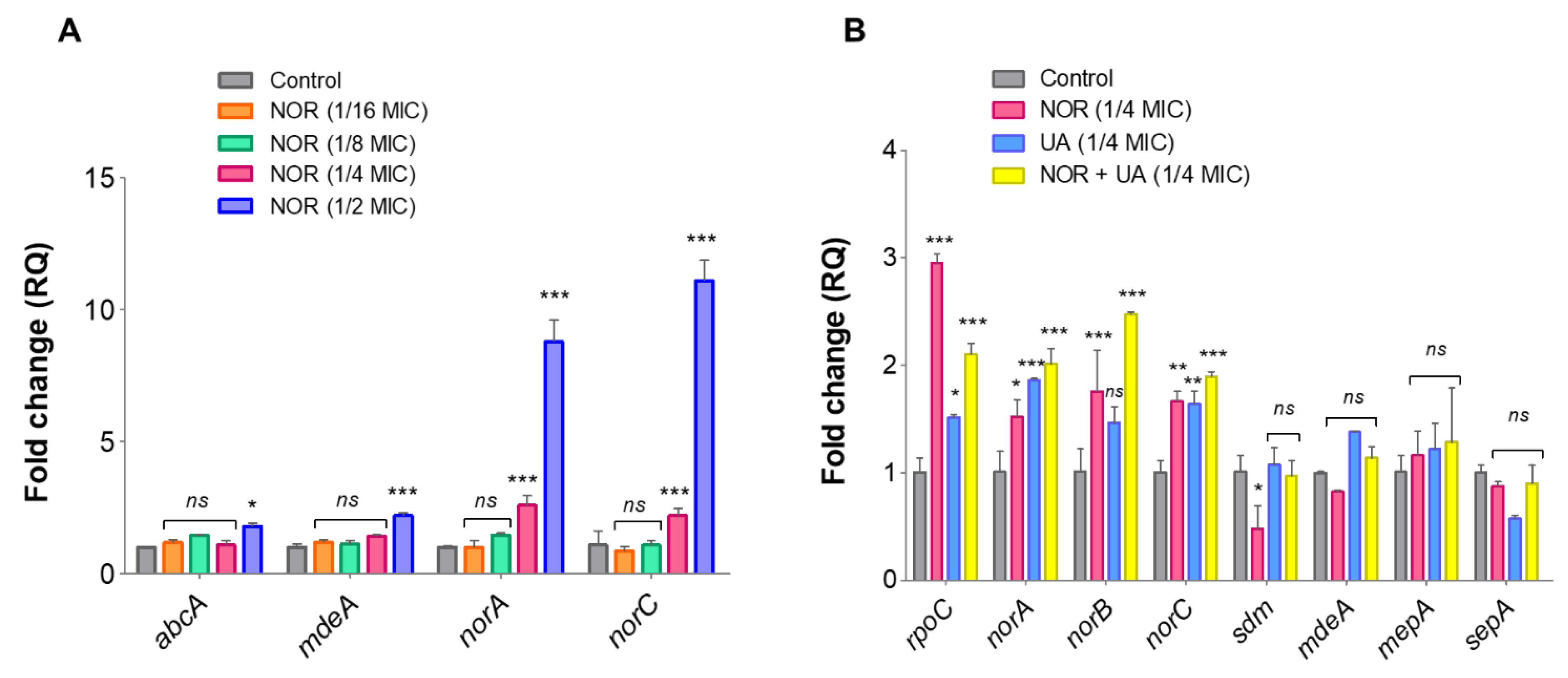

3.5. Expression Analysis of Efflux Pump Genes and Drug Transporters through RT-qPCR

Compared to untreated control, NOR treatment caused induced expression of efflux pump related genes in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 5A). Furthermore, treatment of UA and NOR+UA on the expression of these efflux pump genes was compared to untreated controls, and findings suggest that exposure to a sublethal dose of UA+NOR (1/4 MIC of combination) can induce the expression of efflux pump genes in MRSA 2071 (

Figure 5B). Interestingly, UA treatment (1/4 MIC) also induced expression of NorA and NorC but lesser than NOR (1/4 MIC) or in combination (NOR+UA). Increased expression of efflux pump genes at tested concentration was found in accordance with the EtBr assay

, where the addition of sublethal concentration (1/4 MIC) of NOR and UA induced efflux activity (Figures 4A and 4B).

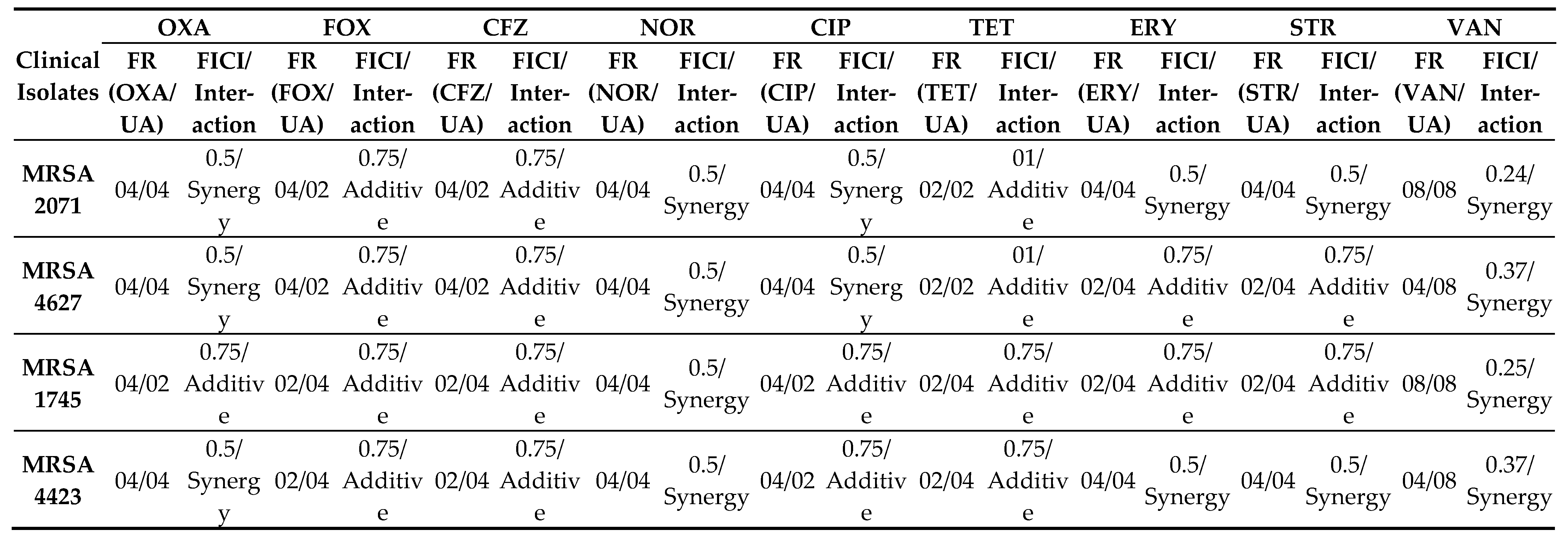

3.6. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Proteins by Nano-LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS

Treatment of sublethal concentrations (1/4 MIC) of UA and NOR caused up- and down-regulation of several specific and common proteins. Numerous proteins including metabolic pathways, chaperones, and redox homeostasis related functions were identified in MRSA 2071 and a list of all proteins (MS/MS Score >100) is summarized in

Table 3, Table S1. Exposure of UA significantly downregulated the abundance of various proteins such as formate acetyltransferase, DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta (RpoB), and subunit beta’ (RpoC), translation elongation factors (EF-Tu), translation initiation factors (IF-2, IF-3), heat shock chaperone (DnaK), glutamine synthetase, and other metabolic enzymes such as enolase, glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Notably, compared to control, both UA and NOR significantly upregulated proteins related to the oxidative stress and cell homeostasis such as peroxidase (Tpx-1), alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AphC), and general stress protein (UspA). The presence of NOR, and NOR+UA increased the abundance of the citric acid cycle and other metabolic pathway related enzymes including succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit alpha, pyruvate kinase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and malate:quinone oxidoreductase. There were also a few common proteins such as carbamoyl phosphate synthase large subunit that were significantly downregulated in presence of both NOR and UA.

NOR+UA exerted a similar or more intense response than NOR or UA did alone which again confirms the synergy between two. For example- upregulation of proteins such as malate:quinone oxidoreductase (

Table 3, Table S1). Overall, comparative proteomic analysis suggests that most of the upregulated proteins, in response to UA and NOR, include stress and cell homeostasis-related proteins while most of the other identified proteins were found to be downregulated in comparison to the control. Important to note that individual concentrations of NOR and UA was reduced in combination, and thus proteins that were up- or down-regulated in response to either NOR alone or UA alone showed trend reversal in NOR+UA treatment, while proteins that remained up- or down-regulated in response to the NOR+UA are likely targeted by the synergistic action of both.

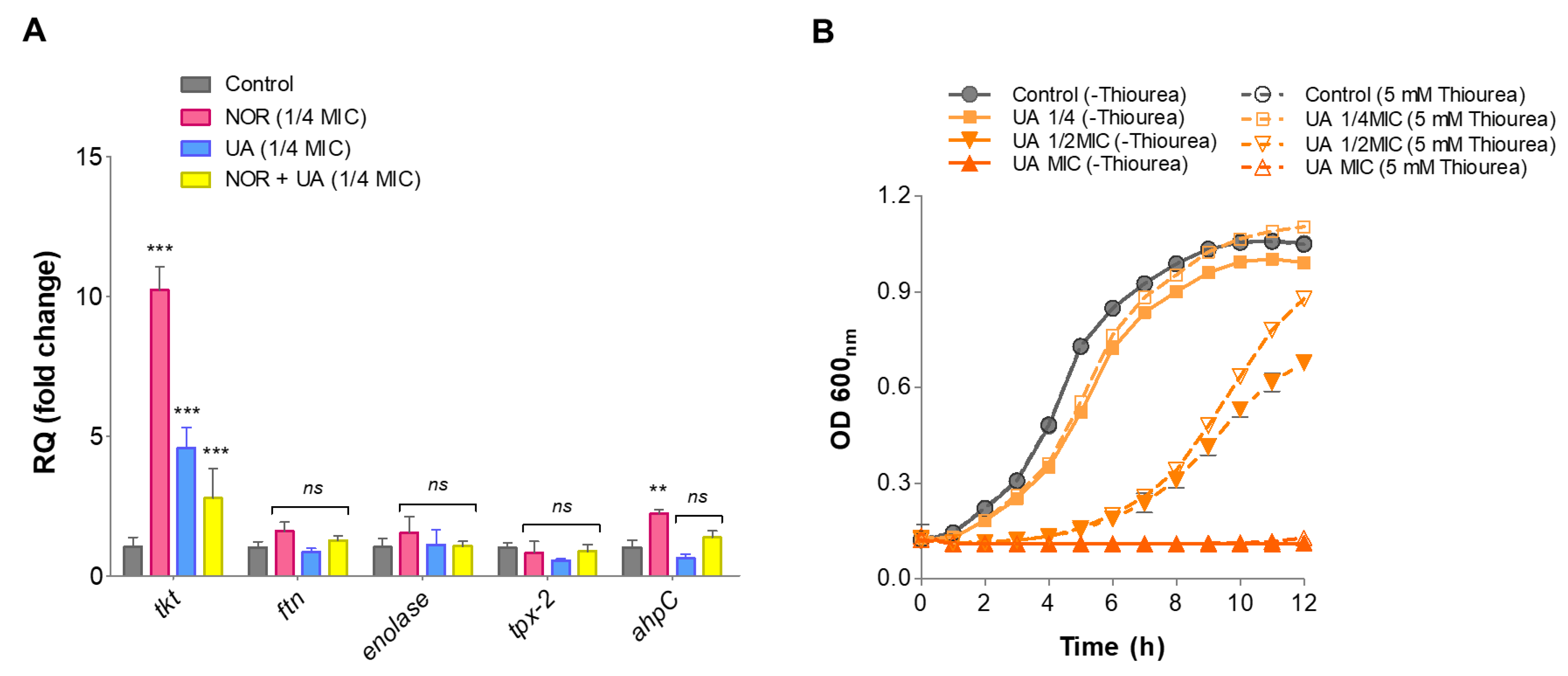

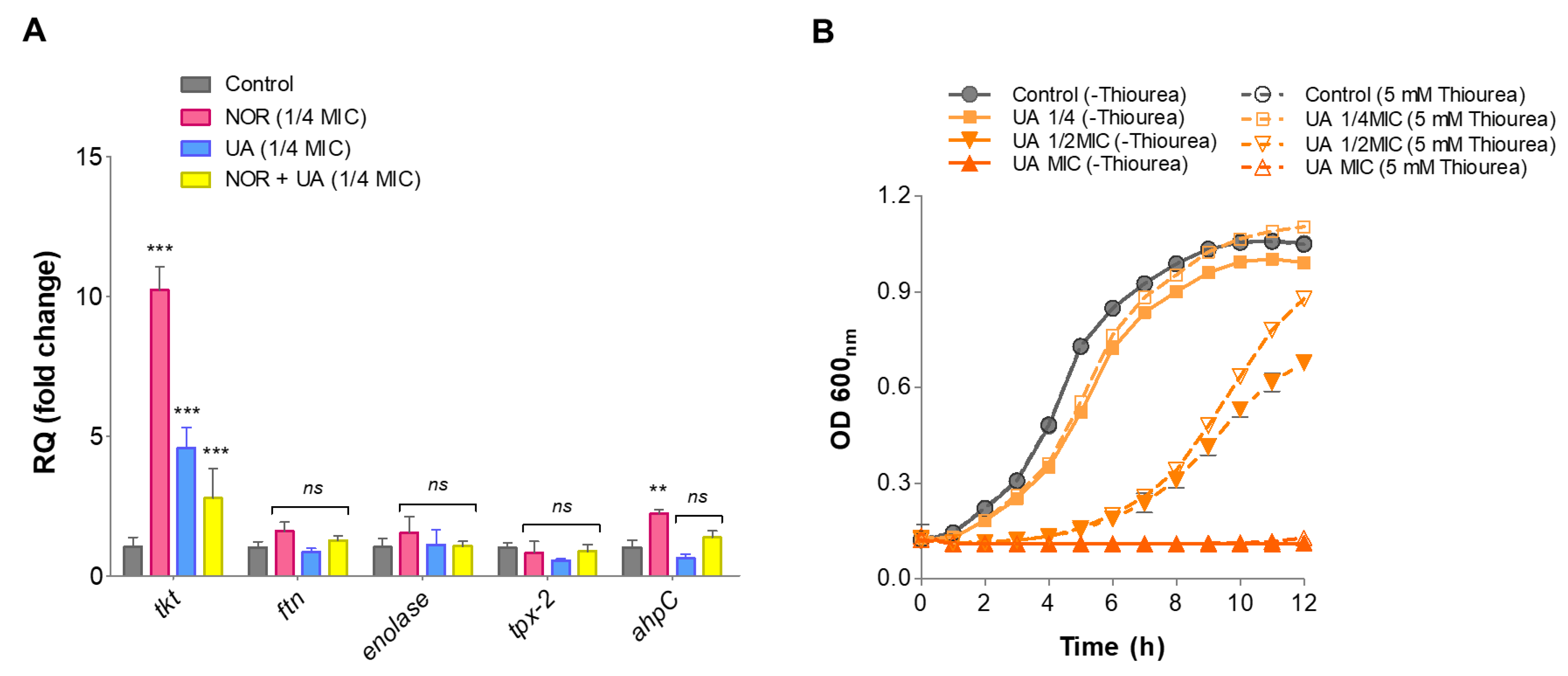

3.7. Gene Expression Analysis of Identified Protein through RT-qPCR

Relative gene expression of proteins identified through LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS was validated by RT-qPCR under the same treatments conditions. The identified genes involved in oxidative stress defense (

ahpC, tpx, ftn), and a few metabolic enzymes (

eno, tkt) were selected for this analysis. Compared to the control, NOR treatment significantly induced expression levels of oxidative stress-responsive genes such as

ahpC (~2.2-fold) and metabolic enzymes

tkt (~10.0-fold) (

Figure 6A). NOR+UA (1/4 MIC of combination) also induced expression of these gene but to a lower extent than NOR treatment (

Figure 6A).

3.8. Thiourea Rescued Growth Inhibition by UA

Thiourea is a potent hydroxyl radical scavenger, and it was showed to protect against antibiotics stress including NOR antibiotic [

20]. Therefore, to investigate if thiourea as an antioxidant can protect from UA-induced radical stress, the growth of MRSA 2071 was assessed in presence various concentrations of thiourea. It was found that the addition of 5 mM of thiourea is non-inhibitory itself but can significantly rescue growth inhibition caused by UA (

Figure 6B)

3.9. In-Vivo Anti-Staphylococcal Efficacy and Toxicity Assessment

The infected, untreated group exhibited a high microbial load, while UA alone (0.5 mg/kg, 01 mg/kg, 05 mg/kg, and 10 mg/kg), NOR alone (01 mg/kg, 05 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, and 20 mg/kg, and combination of NOR+UA (NOR, 05 mg/kg+UA, 01 mg/kg; NOR, 10 mg/kg+UA, 01 mg/kg; NOR, 05 mg/kg+UA, 02 mg/kg, and NOR, 10 mg/kg+UA, 02 mg/kg) treatment significantly (p <0.001) reduced the microbial load in a dose-dependent manner as compared to the untreated control (Figure S1). However, the microbial load was found slightly higher than that of standard antibiotic vancomycin which was used as a positive control.

To assess the effect of UA on healthy and infected mice, the toxicity studies were separated into two major groups, each with relevant controls. There were no significant changes in body weight in the healthy group who were given an effective dose in a combination of NOR with UA (NOR+UA) continuously for 07 days. The oral acute toxicity profile between treated and untreated mice, there were no significant differences in behavioural, haematological, or serum biochemical markers (Table 5). Based on observation, UA can be considered safe.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that UA exhibits potent activity (MIC, 3.9 - 7.8 µg/ml) against clinical isolates (

mecA+) of MRSA that are resistant to several classes of antibiotics including beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, and protein biosynthesis inhibitors. Interestingly, UA could re-sensitize MRSA isolates to the different conventional antibiotics in combination. (

Table 1)

. Combination of NOR and UA (NOR+UA) showed synergism against all tested MRSA isolates (

Table 2). Growth kinetics study also confirmed the interaction between NOR and UA (

Figure 1). SEM analysis of MRSA 2071 in the presence of NOR and UA showed rough cell morphology (

Figure 2). Cell leakage assay showed the presence of proteins and nucleic acids which suggested damaged cell membranes in MRSA 2071 (

Figure 3). [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

EtBR efflux assays suggest that UA interferes with efflux pumps mechanism, and which can re-sensitize MRSA 2071 to NOR [

29]. EtBr is a common substrate for many transporters such as NorA, NorB, NorC, MepA, and SepA in

S. aureus [

30]. It was found that NOR, at all tested concentrations, can induce efflux activity (decreased fluorescence) as compared to control (cells +EtBr) (

Figure 4A). Interestingly, MIC and 2MIC of NOR showed reduced efflux activity compared to 1/2 MIC which suggests that stress caused by NOR at higher concentrations can damage efflux pump (

Figure 4A). UA also modulated efflux action and its effect varied greatly based on concentration. A sublethal concentration of UA slightly induced the efflux activity but higher concentration (MIC/2MIC) of UA was found to be highly deleterious compared to MIC and 2MIC of NOR exposure (

Figure 4B). The combination of both (NOR+UA) damaged efflux activity more strongly which further confirms synergistic activity against MRSA 2071 (

Figure 4D).

The RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that NOR induces expression of efflux pump genes specifically

norA and

norC. Expression of these genes has been implicated in fluoroquinolones resistance in

S. aureus [

31,

32]. UA at lower concentrations also induced expression of efflux genes

norA, and

norC (

Figure 5A). Hence, exposure to sublethal concentrations of NOR and UA showed a positive correlation between observed efflux pump activity and gene expression (mRNA) pattern in MRSA 2071. Both efflux assay and RT-qPCR experiments suggest that NOR can induce efflux activity in a dose dependent manner and UA could damage efflux pump activity at higher concentrations (MIC and 2MIC) and showed synergy with NOR.

Furthermore, to analyze the global response induced by NOR, UA, and a combination of both, proteome profiling was carried out. A significant up-regulation in various oxidative stress-related proteins such as peroxidase, alkyl-hydroperoxidase, universal stress protein UspA, and ribosomal proteins such as L25, S2 suggested ROS accumulation in response to both NOR, and UA (

Table 3).

S. aureus and other bacteria express various redox balancing or ROS scavenging systems to escape from the oxidative threat. Some other up-regulated proteins in response to NOR and NOR+UA included TCA cycle enzymes such as malate:quinone oxidoreductase, succinyl-CoA synthetase subunits (alpha and beta), acetate kinase, isocitrate dehydrogenase. Up-regulation of TCA enzymes under antibiotic stress produces oxidative stress in bacteria [

24,

33]. Treatment of NOR and NOR+UA also up-regulated an iron-scavenging protein, ferritin, that is reported to be induced under oxidative stresses in bacteria [

34,

35].

In response to UA and NOR treatments, many of the identified proteins were down regulated. UA potentially down regulated the abundance of some proteins such as DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta (RpoB), molecular chaperone (GroEL), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and carbamoyl phosphate synthase large subunit, a stationary stage stress protein (

Table 3). DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunits (RpoB and RpoC) are reported to contribute to the development of methicillin resistance phenotype in

S. aureus as well as multi-drug resistance in several other deadly pathogens like

Mycobacterium sp [

36,

37,

38]. Proteins that were more highly affected by UA than NOR could be specific targets of UA. An earlier study suggested that certain proteins are more likely to get induced or damaged by oxidative stresses [

22]. Thus, under the conditions of treatments, reduced levels of transcription, translation, and ribosomal proteins might be responsible for the low abundance of other proteins in MRSA 2071. Several common proteins affected by both treatments were also regulated similarly in combination of NOR+UA.

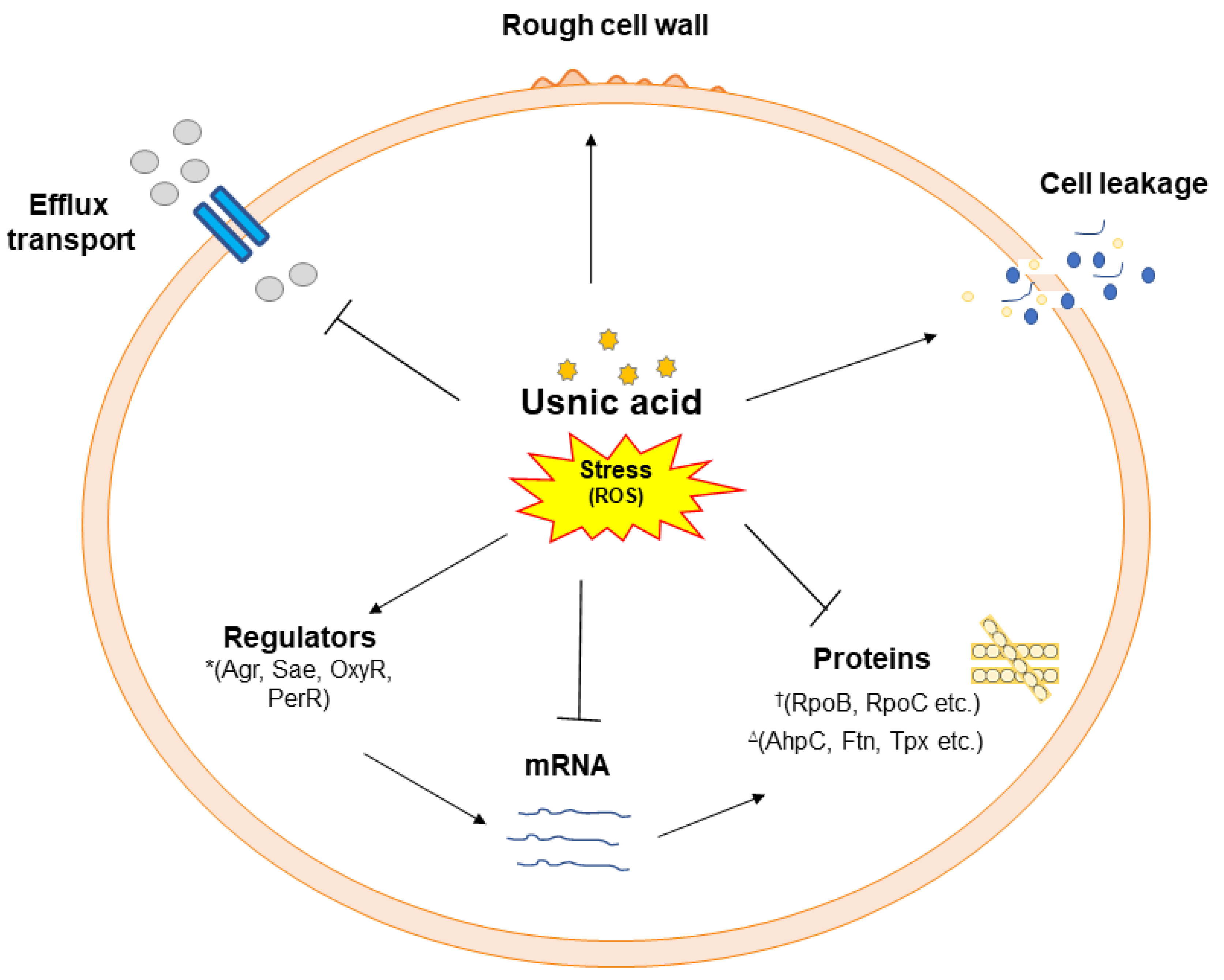

The thiourea experiment further confirms that oxidative stress is caused by UA in MRSA 2071 [

22,

39]. A study by Kohanski et al. 2007 also suggested that antibiotics can produce hydroxyl radicals and addition of thiourea could rescue cell damage caused by antibiotics stress [

24]. The findings of this study are consistent and suggest that UA targets various cellular components by inducing a stress response which leads to cell death (

Figure 7).

In-vivo study for toxicity assessment and anti-bacterial efficacy considered UA was safe under the tested conditions.

5. Conclusion

In the present study, it was found that UA exerts strong inhibitory action against MRSA and shows synergy with antibiotics such as NOR. UA could affect the efflux system and cause cell leakage. Proteome analysis found several specific targets of UA that can provide new insights to design and develop novel therapeutics against MSRA. This study revealed several yet unreported targets of UA such as DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunits (RpoB and RpoC) which causes methicillin resistant phenotype. Differential protein expression and growth rescue by thiourea suggest that UA imbalance cells redox status. Furthermore, an in-vivo study suggests that UA can be safely used to develop phytopharmaceuticals. Combination of UA with antibiotics such as NOR can help reduce the dose, lower the cost and reuse old antibiotics that have become ineffective against MRSA and other drug-resistant bacteria.

Author Contributions

BG, SK, and MPD conceived the idea and wrote the manuscript. BG and SK performed cell-based assays, RT-qPCR, and proteomics studies, and analyzed the data. BG and PK performed the in-vivo study under the guidance of AP. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The Biological Central Facility and encouragement provided by Director, CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow is gratefully acknowledged. The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Prof. K. N. Prasad, Laboratory of Clinical Microbiology, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences (SGPGIMS), Lucknow, India for providing methicillin-resistant clinical isolates of S. aureus. The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Dr. Rajendra P. Patel, CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow, India for operating nano-LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS & collection of MS/MS data, and Dr. Pooja Singh, CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow, India for SEM micrography. Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, India is gratefully acknowledged for providing Senior Research Fellowship (award number 80/875/2014-ECD-I) to BG. This work was part of CSIR Network Project BSC-0203 and MLP-06 of CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow, India.

References

- Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, Pulcini C, Kahlmeter G, Kluytmans J, Carmeli Y, Ouellette M, Outterson K, Patel J, Cavaleri M, Cox EM, Houchens CR, Grayson ML, Hansen P, Singh N, Theuretzbacher U, Magrini N; WHO Pathogens Priority List Working Group. 2018. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 18: 318-327. [CrossRef]

- Rincón, S., Panesso, D., Díaz, L., Carvajal, L. P., Reyes, J., Munita, J. M., & Arias, C. A. 2014. Resistencia a antibióticos de última línea en cocos Gram positivos: la era posterior a la vancomicina [Resistance to „last resort” antibiotics in Gram-positive cocci: The post-vancomycin era]. Biomedica : revista del Instituto Nacional de Salud, 34 Suppl 1(0 1), 191–208.

- Coates ARM, Hu Y, Holt J, Yeh P. 2020. Antibiotic combination therapy against resistant bacterial infections: synergy, rejuvenation, and resistance reduction. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 18:5-15. [CrossRef]

- Khare T, Anand U, Dey A, Assaraf YG, Chen ZS, Liu Z, & Kumar, V. 2021. Exploring phytochemicals for combating antibiotic resistance in microbial pathogens. Frontiers in pharmacology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Foster TJ. 2017. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 41(3), 430-449. [CrossRef]

- Costa SS, Viveiros M, Amaral L, & Couto I. 2013. Multidrug Efflux Pumps in Staphylococcus aureus: an Update. Open Microbiol J, 7, 59-71. [CrossRef]

- Dashtbani-Roozbehani A, and Melissa HB. 2021. „Efflux Pump Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance by Staphylococci in Health-Related Environments: Challenges and the Quest for Inhibition” Antibiotics 10, no. 12: 1502. [CrossRef]

- Kakoullis L, Papachristodoulou E, Chra P, & Panos G. 2021. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Important Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens and Novel Antibiotic Solutions. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland), 10(4), 415. [CrossRef]

- Dieu A, Mambu L, Champavier Y, Chaleix V, Sol V, Gloaguen V. 2020. Antibacterial activity of the lichens Usnea florida and Flavoparmelia caperata (Parmeliaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. 34: 3358–3362. [CrossRef]

- Galanty A, Paśko P, & Podolak I. 2019. Enantioselective activity of UA: A comprehensive review and future perspectives. Phytochemistry Reviews, 18(2), 527-548. [CrossRef]

- Francolini I, Norris P, Piozzi A, Donelli G, & Stoodley P. 2004. UA, a natural antimicrobial agent able to inhibit bacterial biofilm formation on polymer surfaces. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 48(11), 4360-4365. [CrossRef]

- Maciąg-Dorszyńska M, Węgrzyn G, & Guzow-Krzemińska B. 2014. Antibacterial activity of lichen secondary metabolite UA is primarily caused by inhibition of RNA and DNA synthesis. FEMS microbiology letters, 353(1), 57-62. [CrossRef]

- Nithyanand P, Shafreen RMB, Muthamil S, & Pandian SK. 2015. UA inhibits biofilm formation and virulent morphological traits of Candida albicans. Microbiological research, 179, 20-28. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar B, Kumar S, Darokar MP. 2022. UA: A Potential Natural Anti-Staphylococcal Agent. Ann Clin Pathol 9(1): 1156.

- Gupta VK, Verma S, Gupta S, Singh A, Pal A, Srivastava SK, Srivastava PK, Singh SC & Darokar MP. 2012. Membrane-damaging potential of natural L-(-)-UA in Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 31(12), 3375-3383. [CrossRef]

- Gangwar B, Kumar S, & Darokar M P. 2020. Glabridin averts biofilms formation in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by modulation of the surfaceome. Frontiers in microbiology, 11, 1779. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Novales G, Leaños-Miranda B E, Vilchis-Pérez M, & Solórzano-Santos F. 2006. In vitro activity effects of combinations of cephalothin, dicloxacillin, imipenem, vancomycin and amikacin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. strains. Annals of clinical microbiology and antimicrobials, 5, 25. [CrossRef]

- Aelenei P, Rimbu CM, Horhogea CE, Lobiuc A, Neagu AN, Dunca SI, Motrescu I, Dimitriu G, Aprotosoaie AC, & Miron A. 2020. Prenylated phenolics as promising candidates for combination antibacterial therapy: Morusin and kuwanon G. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 28(10), 1172-1181. [CrossRef]

- Viveiros M, Rodrigues L, Martins M, Couto I, Spengler G, Martins A, Amaral L. 2010. Evaluation of efflux activity of bacteria by a semi-automated fluorometric system. Methods Mol Biol. 642:159-72. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Rai AK, Mishra MN, Shukla M, Singh PK, Tripathi AK. 2012. RpoH2 sigma factor controls the photooxidative stress response in a non-photosynthetic rhizobacterium, Azospirillum brasilense Sp7. Microbiology 158: 2891-2902. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Sadygov RG & Yates JR. 2004. A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem, 76, 4193-4201. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S. , Gupta VK, Kumar P, Kumar R, Joshi R, Pal A, & Darokar MP. 2019. UA modifies MRSA drug resistance through down-regulation of proteins involved in peptidoglycan and fatty acid biosynthesis. FEBS open bio, 9(12), 2025-2040. [CrossRef]

- Pompilio A, Riviello A, Crocetta V, Di Giuseppe F, Pomponio S, Sulpizio M. 2016. Evaluation of antibacterial and antibiofilm mechanisms by UA against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Future Microbiol. 11: 1315-1338. [CrossRef]

- Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, & Collins JJ. 2007. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell, 130, 797-810. [CrossRef]

- Brynildsen MP, Winkler JA, Spina CS, MacDonald IC, & Collins JJ. 2013. Potentiating antibacterial activity by predictably enhancing endogenous microbial ROS production. Nature biotechnology, 31, 160-165. [CrossRef]

- Su HL, Chou CC, Hung DJ, Lin SH, Pao IC, Lin JH, Huang FL, Dong RX & Lin JJ. 2009. The disruption of bacterial membrane integrity through ROS generation induced by nanohybrids of silver and clay. Biomaterials, 30, 5979-5987. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, & Drlica K. 2014. Reactive oxygen species and the bacterial response to lethal stress. Current opinion in microbiology, 21, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Wong F, Stokes JM, Cervantes B, Penkov S, Friedrichs J, Renner LD & Collins JJ. 2021. Cytoplasmic condensation induced by membrane damage is associated with antibiotic lethality. Nature Communications, 12, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz FJ, Fluit A C, Luckefahr M, Engler B, Hofmann B, Verhoef J, Heinz HP, Hadding U, and Jones ME. 1998. The effect of reserpine, an inhibitor of multidrug efflux pumps, on the in vitro activities of ciprofloxacin, sparfloxacin and moxifloxacin against clinical isolates of S. aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42: 807-810. [CrossRef]

- Martins M, McCusker MP, Viveiros M, Couto I, Fanning S, Pagès JM, & Amaral, L. 2013. A Simple Method for Assessment of MDR Bacteria for Over-Expressed Efflux Pumps. The open microbiology journal, 7: 72–82. [CrossRef]

- Costa SS, Viveiros M, Rosato AE. 2015. Impact of efflux in the development of multidrug resistance phenotypes in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol 15:232. [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, Onodera Y, Lee JC, & Hooper DC. 2008. NorB, an efflux pump in Staphylococcus aureus strain MW2, contributes to bacterial fitness in abscesses. Journal of bacteriology, 190(21), 7123–7129. [CrossRef]

- Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, & Collins JJ. 2010. How antibiotics kill bacteria: from targets to networks. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 8(6), 423-435. [CrossRef]

- Touati, D. 2000. Iron and oxidative stress in bacteria. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics, 373, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Smith, JL. 2004. The physiological role of ferritin-like compounds in bacteria. Critical reviews in microbiology, 30, 173-185. [CrossRef]

- Panchal VV, Griffiths C, Mosaei H, Bilyk B, Sutton JAF, Carnell OT, Hornby DP, Green J, Hobbs JK, Kelley WL, Zenkin N, Foster SJ. Evolving MRSA: High-level β-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with RNA Polymerase alterations and fine tuning of gene expression. PLoS Pathog. 2020 16:e1008672. [CrossRef]

- de Vos M, Müller B, Borrell S, Black PA, van Helden PD, Warren RM, Gagneux S, Victor TC. Putative compensatory mutations in the rpoC gene of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis are associated with ongoing transmission. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 57:827-32. [CrossRef]

- Laurent JM, Vogel C, Kwon T, Craig SA, Boutz DR, Huse HK, Nozue K, Walia H, Whiteley M, Ronald PC & Marcotte EM. 2010. Protein abundances are more conserved than mRNA abundances across diverse taxa. Proteomics, 10, 4209–4212. [CrossRef]

- Munita JM, Arias CA. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiol Spectr. 2016 4: 10.1128. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Growth kinetics study of MRSA 2071 under control and treated with different concentration of (A) Norfloxacin (NOR, MIC 500 µg/ml, ½MIC 250 µg/ml and, ¼MIC 125 µg/ml), (B) Usnic acid (UA MIC 7.8 µg/ml, ½MIC 3.9 µg/ml and, ¼MIC 1.95 µg/ml), and (C) Norfloxacin+Usnic acid (combination) (NOR+UA MIC of combination, NOR 125 µg/ml+ UA 1.95 µg/ml, ½MIC of combination, NOR 62.5 µg/ml+ UA 0.97 µg/ml and ¼MIC of combination, NOR 31.2 µg/ml+ UA 0.48 µg/ml). Data represents the average value obtained from three independent. Graph represents average value from three independent assays and errors bar shows standard deviation (±SD).

Figure 1.

Growth kinetics study of MRSA 2071 under control and treated with different concentration of (A) Norfloxacin (NOR, MIC 500 µg/ml, ½MIC 250 µg/ml and, ¼MIC 125 µg/ml), (B) Usnic acid (UA MIC 7.8 µg/ml, ½MIC 3.9 µg/ml and, ¼MIC 1.95 µg/ml), and (C) Norfloxacin+Usnic acid (combination) (NOR+UA MIC of combination, NOR 125 µg/ml+ UA 1.95 µg/ml, ½MIC of combination, NOR 62.5 µg/ml+ UA 0.97 µg/ml and ¼MIC of combination, NOR 31.2 µg/ml+ UA 0.48 µg/ml). Data represents the average value obtained from three independent. Graph represents average value from three independent assays and errors bar shows standard deviation (±SD).

Figure 2.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis of MRSA 2071 treated with Norfloxacin, Usnic acid, and Norfloxacin+Usnic acid. Exposure of Norfloxacin (1/2MIC 250 μg/ml), and to lesser extent with Usnic acid (UA, ½MIC 3.9 μg/ml), caused rough cell morphology compared to untreated control (indicated by arrows). In combination of both Norfloxacin and Usnic acid at lower concentration (NOR+UA ½MIC of combination, NOR 62.5+ UA 0.975 μg/ml) also showed rough morphology compared to control.

Figure 2.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis of MRSA 2071 treated with Norfloxacin, Usnic acid, and Norfloxacin+Usnic acid. Exposure of Norfloxacin (1/2MIC 250 μg/ml), and to lesser extent with Usnic acid (UA, ½MIC 3.9 μg/ml), caused rough cell morphology compared to untreated control (indicated by arrows). In combination of both Norfloxacin and Usnic acid at lower concentration (NOR+UA ½MIC of combination, NOR 62.5+ UA 0.975 μg/ml) also showed rough morphology compared to control.

Figure 3.

Spectrophotometer based measurement of cytoplasmic leakage of nucleic acid at 260 nm and proteins at 280 nm in extracellular medium of MRSA 2071. Leakage shows relative abundance of protein and Nucleic acid (A & D) respectively in presence of Norfloxacin alone at various concentration (NOR ½MIC=250 µg/ml, MIC=500 µg/ml, 2MIC=1000 µg/ml and 4MIC=2000 µg/ml), (B & E) respectively in presence of Usnic acid alone (UA ½MIC=3.9 µg/ml, MIC=7.8 µg/ml, 2MIC=15.6 µg/ml and 4MIC=31.2 µg/ml), (C & F) respectively in presence of Norfloxacin and Usnic acid in combination (NOR+UA ½MIC of combination; NOR 62.5 µg/ml + UA 0.97 µg/ml, MIC of combination; NOR 125 µg/ml+ UA 1.95 µg/ml, 2MIC of combination; NOR 250 µg/ml+ UA 3.9 µg/ml, and 4MIC of combination; NOR 500 µg/ml+ UA 7.8 µg/ml). Graph represents average value from three independent experiment and Error bars represent ± SEM, two-way ANOVA (ns, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 control vs treatment). The experiments were repeated at least twice with n = 3 per experiment. .

Figure 3.

Spectrophotometer based measurement of cytoplasmic leakage of nucleic acid at 260 nm and proteins at 280 nm in extracellular medium of MRSA 2071. Leakage shows relative abundance of protein and Nucleic acid (A & D) respectively in presence of Norfloxacin alone at various concentration (NOR ½MIC=250 µg/ml, MIC=500 µg/ml, 2MIC=1000 µg/ml and 4MIC=2000 µg/ml), (B & E) respectively in presence of Usnic acid alone (UA ½MIC=3.9 µg/ml, MIC=7.8 µg/ml, 2MIC=15.6 µg/ml and 4MIC=31.2 µg/ml), (C & F) respectively in presence of Norfloxacin and Usnic acid in combination (NOR+UA ½MIC of combination; NOR 62.5 µg/ml + UA 0.97 µg/ml, MIC of combination; NOR 125 µg/ml+ UA 1.95 µg/ml, 2MIC of combination; NOR 250 µg/ml+ UA 3.9 µg/ml, and 4MIC of combination; NOR 500 µg/ml+ UA 7.8 µg/ml). Graph represents average value from three independent experiment and Error bars represent ± SEM, two-way ANOVA (ns, P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 control vs treatment). The experiments were repeated at least twice with n = 3 per experiment. .

Figure 4.

Ethidium bromide assay for efflux pump activity of MRSA 2071 under control and treated with different concentrations of Norfloxacin, Usnic acid, and combination of Norfloxacin+Usnic acid. (A) Fluorescence of EtBr in presence of different concentration of Norfloxacin (NOR 2MIC 500 µg/ml, ½MIC 250 µg/ml, ¼MIC 125µg/ml) in comparison to control. (B) Dose dependent inhibition or activation of efflux activity observed under different concentration of Usnic acid (UA 2MIC 15.6 µg/ml, MIC 7.8 µg/ml, ½MIC 3.9 µg/ml, ¼MIC 1.95 µg/ml), (C) Reduced efflux activity in combination of NOR (1/4MIC of combination 31.25 µg/ml) + UA (1/4MIC of combination 0.48 µg/ml) (D) Inhibitory effect of UA (1/2MIC of combination 3.9 µg/ml) on NOR induced efflux activity at various concentration (1/4MIC to MIC of NOR in combinations).

Figure 4.

Ethidium bromide assay for efflux pump activity of MRSA 2071 under control and treated with different concentrations of Norfloxacin, Usnic acid, and combination of Norfloxacin+Usnic acid. (A) Fluorescence of EtBr in presence of different concentration of Norfloxacin (NOR 2MIC 500 µg/ml, ½MIC 250 µg/ml, ¼MIC 125µg/ml) in comparison to control. (B) Dose dependent inhibition or activation of efflux activity observed under different concentration of Usnic acid (UA 2MIC 15.6 µg/ml, MIC 7.8 µg/ml, ½MIC 3.9 µg/ml, ¼MIC 1.95 µg/ml), (C) Reduced efflux activity in combination of NOR (1/4MIC of combination 31.25 µg/ml) + UA (1/4MIC of combination 0.48 µg/ml) (D) Inhibitory effect of UA (1/2MIC of combination 3.9 µg/ml) on NOR induced efflux activity at various concentration (1/4MIC to MIC of NOR in combinations).

Figure 5.

qRT-PCR analysis showing relative expression of genes. (A) Relative expression of efflux pump genes in response to different concentration of Norfloxacin (NOR ½MIC 250 µg/ml, ¼MIC 125 µg/ml, 1/8MIC 62.5 µg/ml, 1/16MIC 31.25 µg/ml) in comparison to control. (B) Relative expression of efflux transporter related genes in response to Usnic acid (UW ¼MIC 1.95 µg/ml), and Norfloxacin+Usnic acid (1/4MIC of NOR+UA in combination 31.25 µg/ml+0.48 µg/ml) in MRSA 2071.

Figure 5.

qRT-PCR analysis showing relative expression of genes. (A) Relative expression of efflux pump genes in response to different concentration of Norfloxacin (NOR ½MIC 250 µg/ml, ¼MIC 125 µg/ml, 1/8MIC 62.5 µg/ml, 1/16MIC 31.25 µg/ml) in comparison to control. (B) Relative expression of efflux transporter related genes in response to Usnic acid (UW ¼MIC 1.95 µg/ml), and Norfloxacin+Usnic acid (1/4MIC of NOR+UA in combination 31.25 µg/ml+0.48 µg/ml) in MRSA 2071.

Figure 6.

qRT-PCR analysis showing relative expression of genes identified in proteome analysis of MRSA 2071. (A) Relative expression of genes encoding protein biosynthesis and metabolic enzymes and oxidative defense in presence of Norfloxacin (NOR 1/4MIC 125 µg/ml), Usnic acid (UA 1/4MIC 1.95 µg/ml), and combination of NOR+UA (1/4MIC of NOR in combination = 31.25 µg/ml+ 1/4MIC of UA in combination 0.48 µg/ml) (B) Growth kinetics of MRSA 2071 grown with or without thiourea and treated with different concentration of Usnic acid (UA MIC 7.8 µg/ml, 1/2MIC=3.9 µg/ml and 1/4MIC=1.95 µg/ml), Samples with 5 mM thiourea (a scavenger of hydroxyl radicals) showed growth recovery in MRSA 2071 exposed to sublethal concentration of treatments (dashed curves) compared to control samples lacking thiourea (solid line curves). No thiourea (-thiourea) control was used to show no inhibition due to 5 mM thiourea itself in culture medium. Data represents the average value obtained from three independent. Graph represents average value from three independent assays and errors bar shows standard deviation (±SD).

Figure 6.

qRT-PCR analysis showing relative expression of genes identified in proteome analysis of MRSA 2071. (A) Relative expression of genes encoding protein biosynthesis and metabolic enzymes and oxidative defense in presence of Norfloxacin (NOR 1/4MIC 125 µg/ml), Usnic acid (UA 1/4MIC 1.95 µg/ml), and combination of NOR+UA (1/4MIC of NOR in combination = 31.25 µg/ml+ 1/4MIC of UA in combination 0.48 µg/ml) (B) Growth kinetics of MRSA 2071 grown with or without thiourea and treated with different concentration of Usnic acid (UA MIC 7.8 µg/ml, 1/2MIC=3.9 µg/ml and 1/4MIC=1.95 µg/ml), Samples with 5 mM thiourea (a scavenger of hydroxyl radicals) showed growth recovery in MRSA 2071 exposed to sublethal concentration of treatments (dashed curves) compared to control samples lacking thiourea (solid line curves). No thiourea (-thiourea) control was used to show no inhibition due to 5 mM thiourea itself in culture medium. Data represents the average value obtained from three independent. Graph represents average value from three independent assays and errors bar shows standard deviation (±SD).

Figure 7.

A schematic of usnic acid stress response and regulation of various targets identified by different cell based and proteome analysis in MRSA 2071. Usnic acid inhibits efflux transport, downregulates enzymes (such as RNA polymerase subunits, RpoB and RpoC)†, and norfloxacin responsive regulators (Agr, Sae etc.)*, however, usnic acid induce oxidative responsive proteins (AhpC, Ftn, and Tpx etc.)∆ and cell leakage possibly by enhancing reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl ions (OH-).

Figure 7.

A schematic of usnic acid stress response and regulation of various targets identified by different cell based and proteome analysis in MRSA 2071. Usnic acid inhibits efflux transport, downregulates enzymes (such as RNA polymerase subunits, RpoB and RpoC)†, and norfloxacin responsive regulators (Agr, Sae etc.)*, however, usnic acid induce oxidative responsive proteins (AhpC, Ftn, and Tpx etc.)∆ and cell leakage possibly by enhancing reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl ions (OH-).

Table 1.

Interactions of Usnic acid in combination with antibiotics against clinical isolates of MRSA.

Table 1.

Interactions of Usnic acid in combination with antibiotics against clinical isolates of MRSA.

Table 2.

Fold Reduction in the MIC of different antibiotics in combination with usnic acid, FICI, and Interactions between usnic acid and antibiotics against clinical isolates of MRSA.

Table 2.

Fold Reduction in the MIC of different antibiotics in combination with usnic acid, FICI, and Interactions between usnic acid and antibiotics against clinical isolates of MRSA.

Table 3.

Showing comparative analysis of proteins (top 20 hits) under treatment conditions than control (without treatment).

Table 3.

Showing comparative analysis of proteins (top 20 hits) under treatment conditions than control (without treatment).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).