1. Introduction

Considerations on Central Nervous System Tumors

The classification of CNS (Central Nervous System) tumors is defined according to WHO (World Health Organization) criteria, which since the 4th edition published in 2016, uses molecular parameters in addition to the histopathological ones already employed for diagnosing the wide range of tumor entities [

1,

2].

These tumors are clinically and biologically disparate, encompassing a broad spectrum from benign neoplasms to highly malignant tumors. Benign tumors (WHO CNS grade 1) are mostly characterized by low mitotic rate, cellular uniformity, and slow growth, and often can be treated surgically. Malignant tumors vary in prognostic grades (WHO CNS grades 2-4) and are characterized by rapid and uncoordinated proliferation, being additionally stratified based on mitotic index and presence of necrosis or microvascular proliferation. They are generally treated with a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy [

2,

3,

4].

The main categories of CNS tumors are Gliomas, encompassing astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and ependymomas; Glioneuronal and neuronal tumors such as gangliogliomas; Embryonal tumors such as medulloblastomas; Meningiomas; and others (

Table 1) [

2,

5,

6].

All categories have subcategories and specific criteria that must be strictly met to assign a tumor to a given group, making diagnosis challenging in rare or atypical cases. Previous studies have reported interobserver variability in the histopathological diagnosis of many CNS tumors, with diffuse gliomas, ependymomas, and embryonal tumors standing out [

2,

3,

4].

Studies demonstrate that methylation profiling offers greater diagnostic precision compared to traditional methods, allowing for detailed stratification of tumor subclasses and providing critical information on copy number variations (CNV) and other genetic alterations. This level of detail is essential for developing more effective and personalized therapeutic strategies. The correlation of previous histological results with methylation-based classification will be conducted using the MolecularNeuropathology.org platform to obtain accurate classification and compare it with previously performed histological diagnoses [

7,

8].

This study aimed to implement and standardize the technique for constructing DNA methylation profiles of Central Nervous System (CNS) tumors in the Cytogenomics laboratory at the Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, evaluating the DNA methylation profile in 16 samples of CNS tumors, specifically medulloblastomas and ependymomas.

The implementation of this technique within the context of the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS), despite being laborious and costly, promises great benefits. The ability to refine the diagnosis and provide a detailed molecular profile of CNS tumors is invaluable for clinical practice. Moreover, the robustness and reproducibility of the results highlight the potential of the methylation methodology to become a standard in the diagnosis of CNS tumors, significantly improving patient prognosis and quality of life.

Results

Methodology Implementation

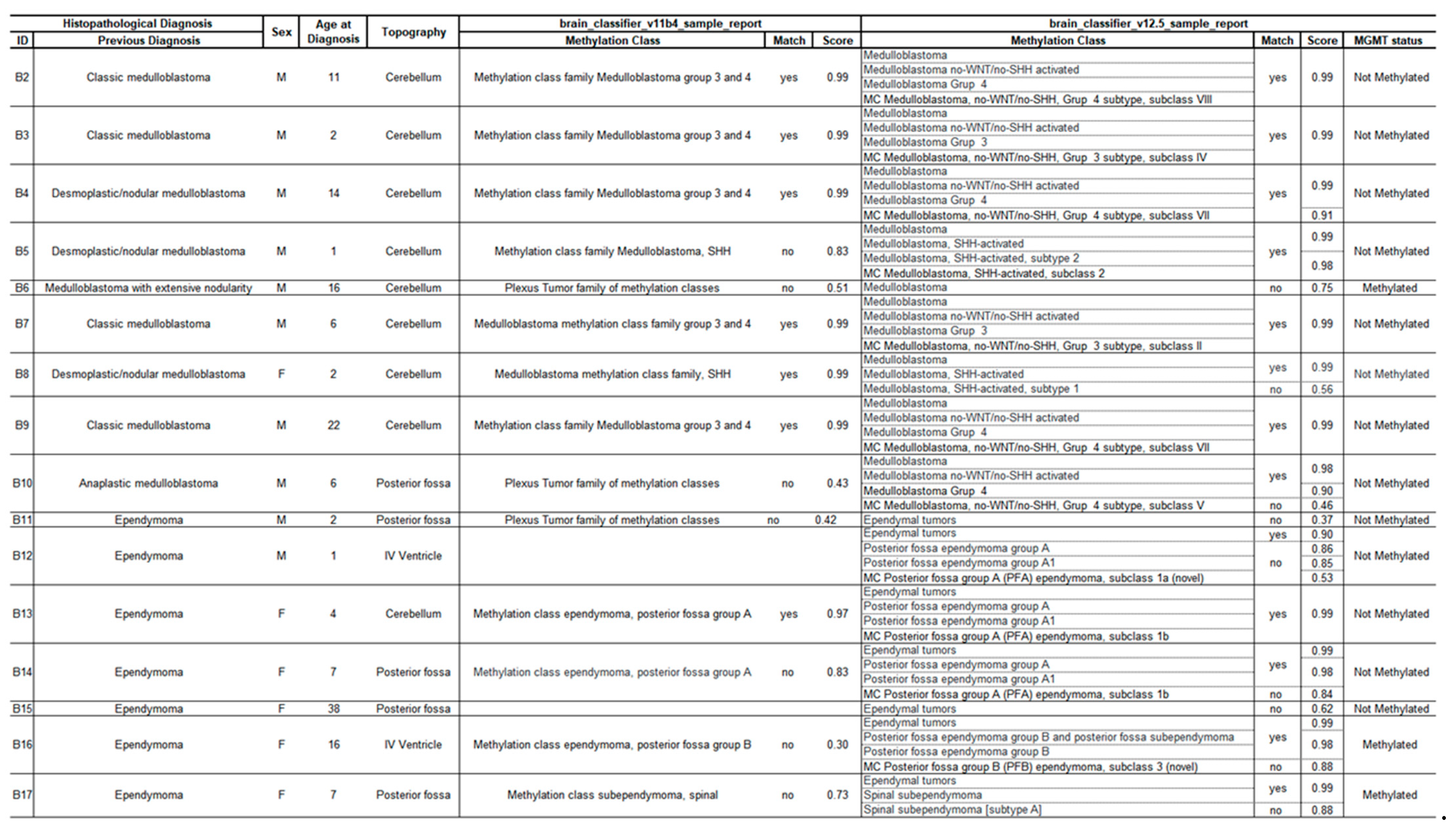

The classification of CNS tumors based on methylation profiling was performed on 16 retrospective cases encompassing two tumor entities: medulloblastomas and ependymomas, including 9 and 7 samples, respectively. More clinical and histopathological information is detailed in

Table 2.

The first step for implementation was the extraction of DNA from FFPE tissues. Tissue resection is subject to material evaluation by a certified pathologist, the tumor region was identified, and its content was confirmed to be above 60%. Accordingly, we standardized the use of 5 sections of 10 µm thickness from tissue fixed in 10% buffered formalin for DNA extraction. The concentrations obtained ranged from 10.5 to 478 ng/µl, with an average of 166 ng/µl and a median of 92.6 ng/µl. The DNA input was standardized at 250 ng for the bisulfite conversion assay, and all samples had sufficient quantification for the methylome assay.

Comparison between Previous Diagnosis and Epigenetic Classification

We compared the classifier score results with histopathological findings according to the recommendations of Capper et al [

3,

4]. A match with a score above 0.9 was obtained in 13/16 cases (81%) in at least one version of the classifier.

In total, 7/16 cases (44%) were classified in both versions (v11b4 and v12.5), including one ependymoma and six medulloblastomas; 6/16 cases (37%) matched only in the most recent version (v12.5), including four ependymomas and two medulloblastomas, and 3/16 cases (19%), composed of two ependymomas and one medulloblastoma, did not achieve a sufficient score for classification (<0.9).

The classifier result was consistent with the initial diagnosis in all classified cases (whether adequately scored or not).

Of the 13 classified cases, the subclass was defined in seven (54%), five cases (38%) were stratified to the subtype, and one (8%) to the family. Of the 16 samples analyzed, 13 did not have a methylated

MGMT gene promoter (

Table 2).

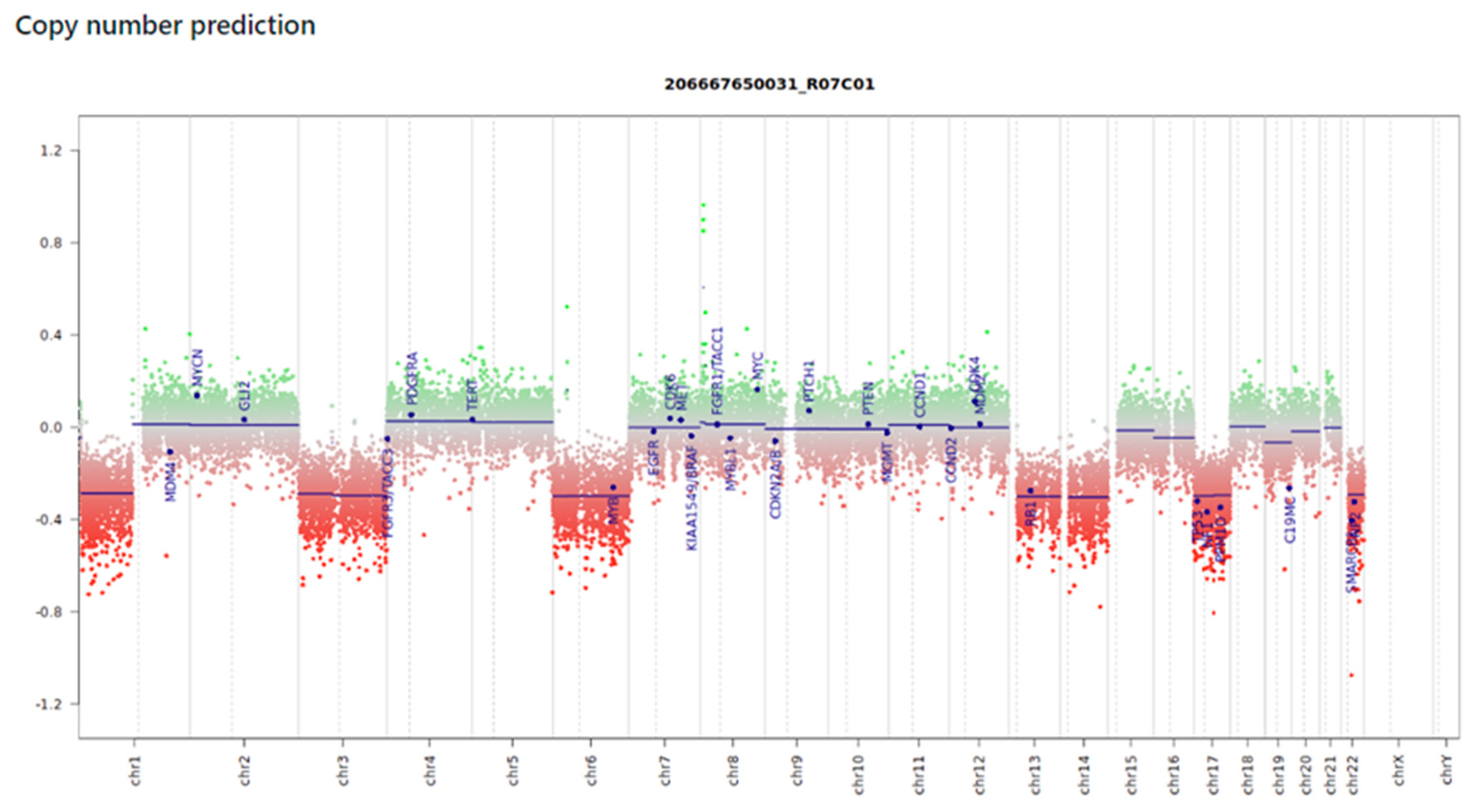

Evaluation of Copy Number Variation (CNV) Data

The platform also offers estimates of copy number gains and losses, gene amplification, and fusions. We investigated the CNV profiles for each case and were able to obtain informative graphs in 87% of them. In two samples that did not achieve a classification score (B6 and B11), the graphs showed scattered probes and were unreliable for the intended analysis, while the last case (B15) presented a clean and noise-free graph, allowing the identification of 1p deletion, deletions of chromosomes 3, 6, 13, 14, 17, and 22, and the

C19MC gene (

Figure 1).

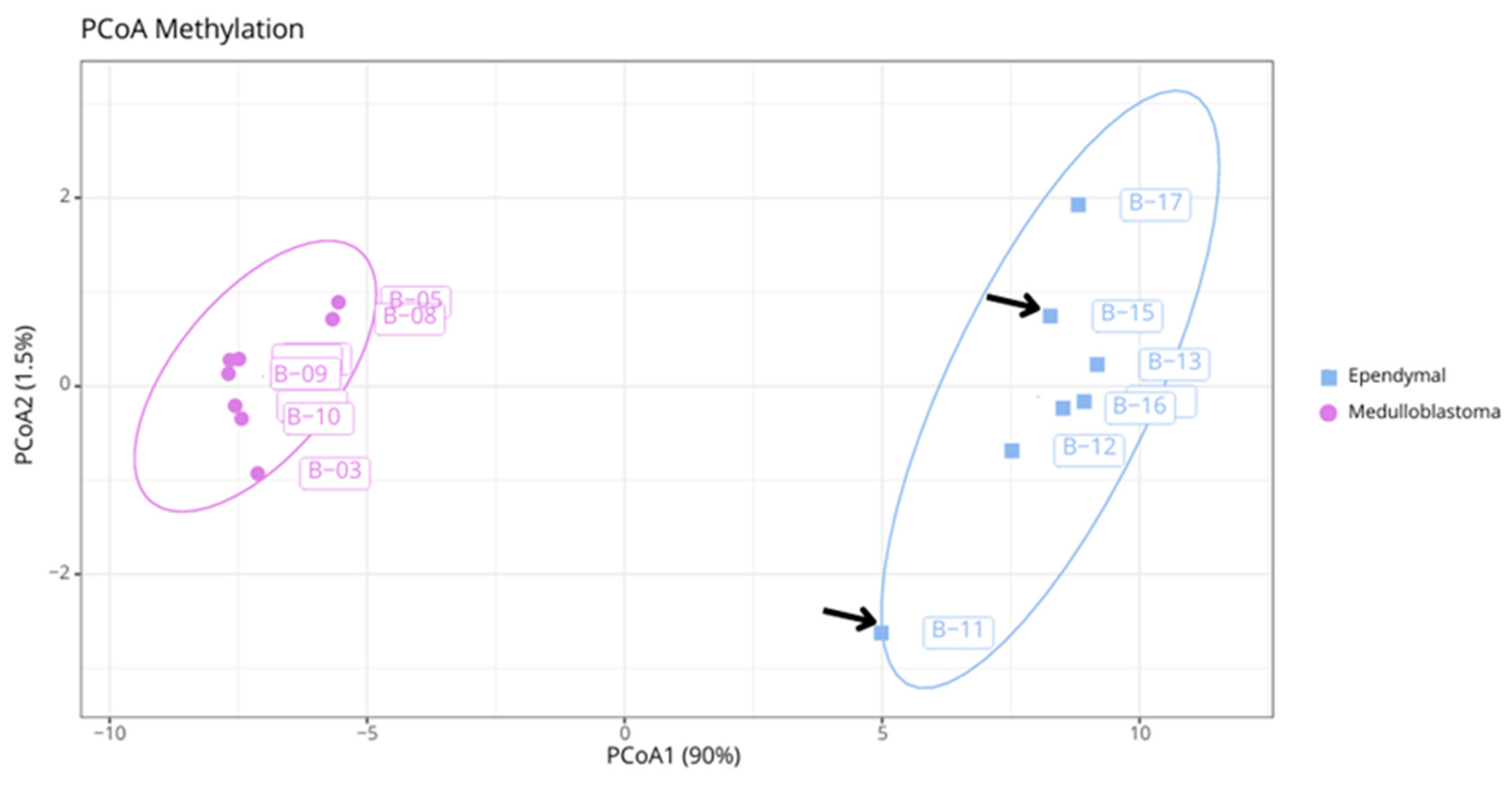

Additional Analyses

We also performed additional bioinformatics analyses. From a dissimilarity matrix, we conducted a principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) using the top 1,000 differentially methylated probes between medulloblastomas and ependymomas. The two tumor entities were linearly separable and highly dissimilar, with homogeneous aggregation by group. Samples B6, B11, and B15 did not achieve the necessary score for classification using the Heidelberg Classifier; however, the segregation of B11 and B15 with other ependymomas can be observed (

Figure 2). Sample B6 did not present sufficient quality for additional analysis.

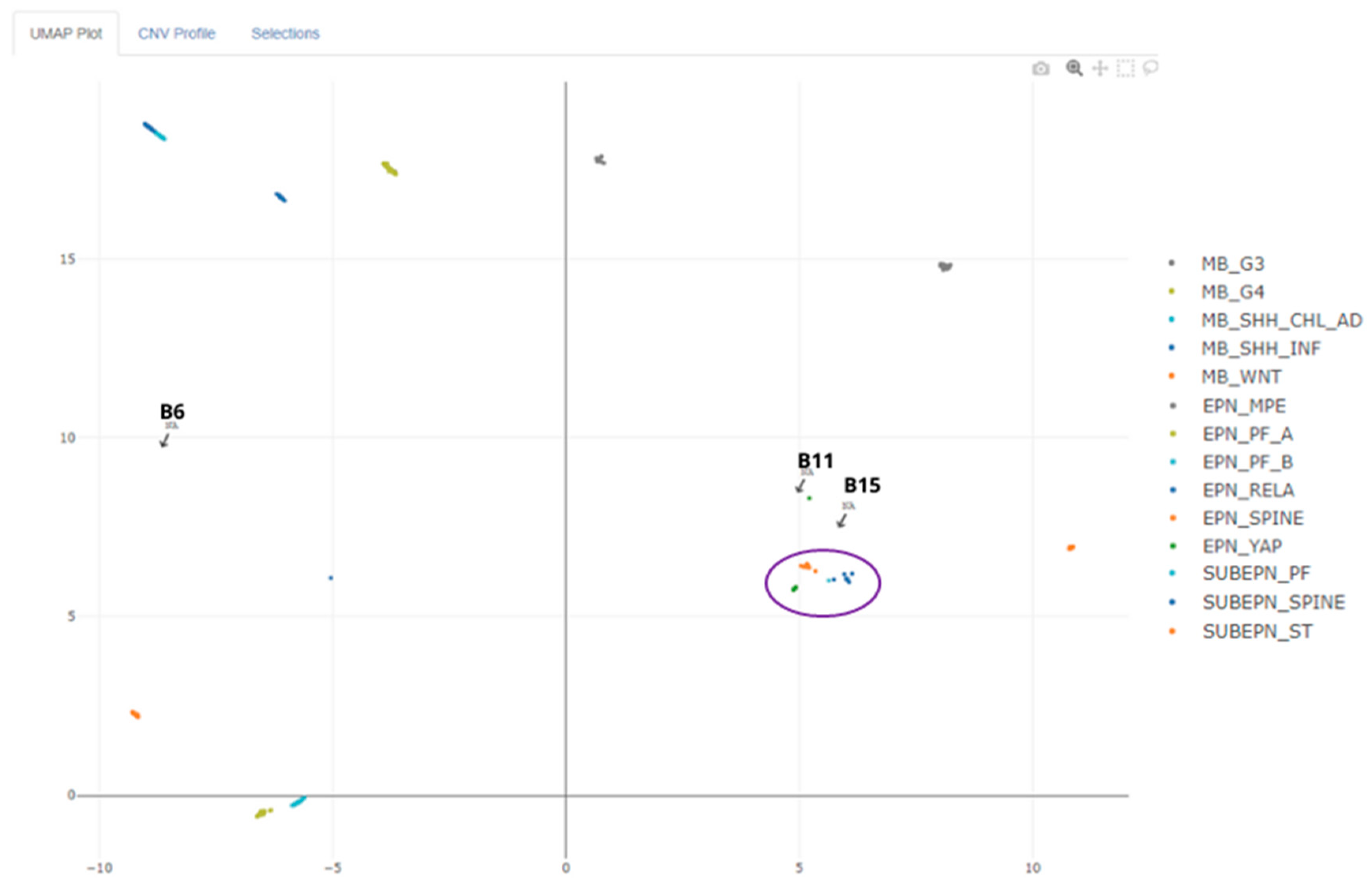

In an attempt to clarify the unclassified cases, we submitted the raw data to EpiDiP for UMAP mapping with thousands of already known tumor entities. Case B6 did not approach any group, while B11 and B15 approximated the ependymoma group, as shown in

Figure 3.

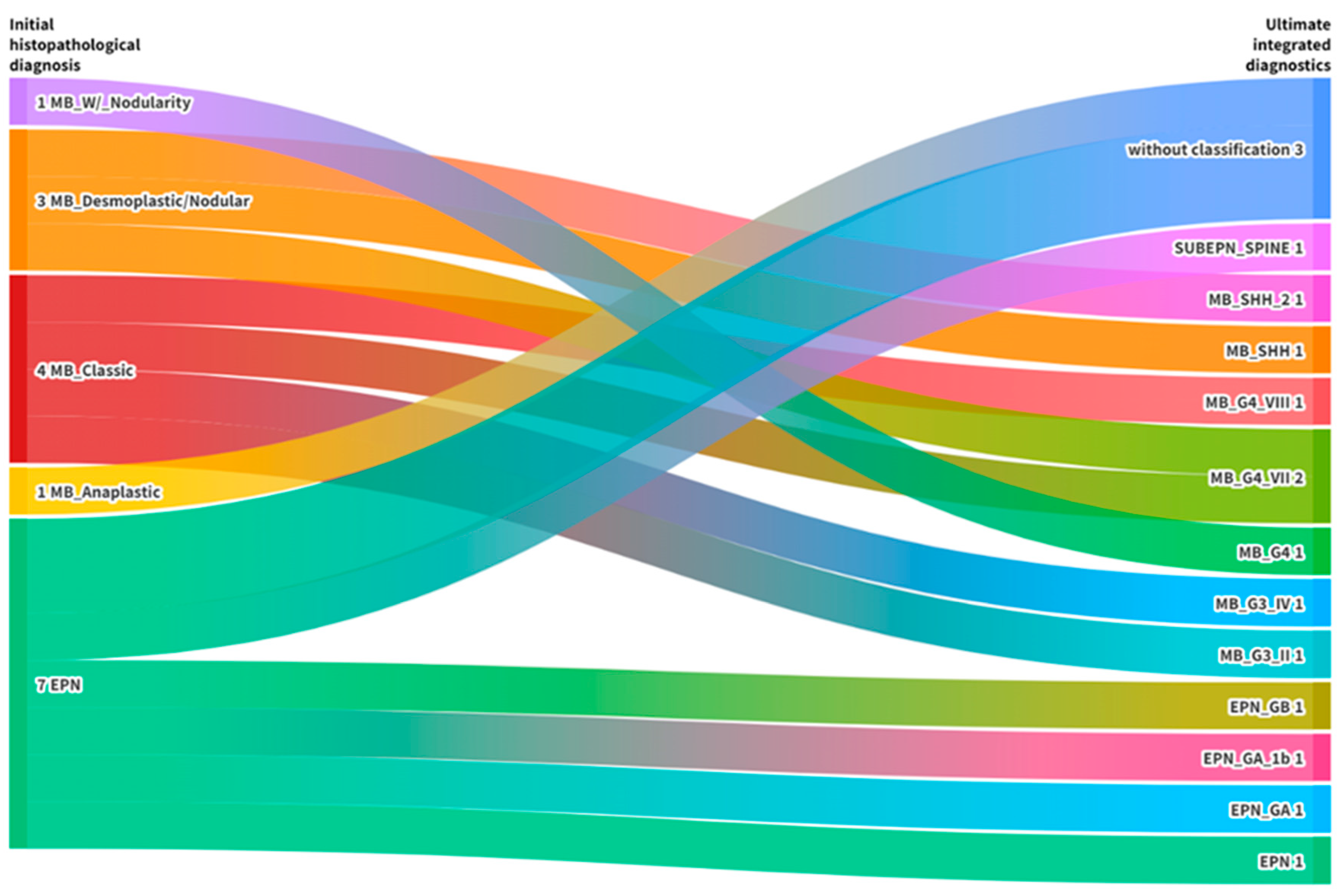

Integration of Results

Finally, it was possible to confirm and refine the initial diagnosis in 13/16 proposed cases (81%). Three tumors (19%) did not achieve the necessary score for classification but were correctly identified regarding the represented entities (

Table 1). Details on the classifications are represented in the alluvial diagram (

Figure 4).

Discussion

CNS tumors is invaluable for clinical practice receives patients with suspected CNS tumors based on imaging diagnosis.

After biopsy, all tumors are subject to histopathological evaluation, and some, such as medulloblastomas and ependymomas, to immunohistochemistry. This information composes the histopathological report, released by the pathologist within 15 days from the date of material entry. Access to molecular techniques such as FISH (Fluorescence in situ hybridization) and massive parallel sequencing is extremely rare, and therapeutic approaches are subject to the limited scenario.

DNA methylation profiling significantly contributed to refining CNS tumor diagnoses, adding depth to their classification. This tool has become essential for diagnosing atypical cases in various reference centers worldwide. Pediatric tumors, such as medulloblastomas and ependymomas, are laboriously classified through conventional histopathology, still being subject to interobserver bias [

3,

4,

9,

10]. Our study demonstrated the method’s ability to refine diagnosis and provide more information about the molecular profile of CNS tumors from samples with different DNA qualities.

Challenges in Implementation of the Methodology

The implementation of the methodology involved the use of five different commercial kits, in addition to the EPIC array assay, in a continuous workflow of at least 11 days for the total processing of one or more samples. Moreover, obtaining satisfactory amounts of DNA from FFPE samples is a challenge for clinical laboratories.

Thus, the use of CNS tumor methylation profiling within the SUS scope in the current public health scenario would be better employed in challenging cases without consensus on diagnosis, presenting unusual characteristics or conflicting morphomolecular data [

9,

11].

Medulloblastomas

The three samples that did not achieve reliable classification, including one medulloblastoma (B6) and two ependymomas (B11 and B15), were subjected to additional analyses for possible clarification. Case B6 was excluded in the quality control stage of additional analyses; however, we submitted the sample to the classifier to evaluate the platform’s performance in different scenarios.

Despite having adequate quantification (85.4 ng/µl), an electrophoresis run after the experiment revealed a high degree of fragmentation of the extracted DNA. This may be directly related to the material collection time (2014), storage, and reagents used for embedding. All these aspects can directly interfere with the sample quality, leading to suboptimal classifier performance [

3,

4]. The resulting CNV graph from the classification was not informative; however, version 12.5 of the classifier was able to correctly interpret the sample as a medulloblastoma, with a score of 0.75 (

Table 2).

While histopathology divides medulloblastomas into three subgroups (WNT, SHH, and Non-WNT/Non-SHH), the methylome separates them into four clinically relevant subgroups (WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4), and can still be stratified into several subclasses [

12,

13].

Ependymomas

Cases B11 and B15 were within the stipulated quality parameters. Sample B11, embedded in 2018, was slightly more degraded than B15, embedded in 2022. This discrepancy was also seen in the CNV analysis. While B11 presented a noisy and difficult-to-interpret graph, B15 presented a clean graph with clearly delineated gains and losses (

Figure 1) that could be used by the pathologist for case understanding.

Investigating CNVs can highlight alterations that assist the pathologist in establishing diagnoses that provide prognostic information or could be of interest for precision medicine [

9]. According to Capper et al [

3,

4], the final diagnostic interpretation can be independently influenced by CNV analysis results and methylation classifier results, as both are considered independent of each other.

During the dissimilarity matrix analysis, it was observed that B11 and B15 grouped with the other ependymomas (

Figure 2), demonstrating the robustness of the methylation profile as a classification method [

3,

4,

9]. However, to verify whether this was a spurious association or a real grouping, the cases were subjected to UMAP analysis using EPiDiP. This revealed the proximity of these cases to other known ependymomas (

Figure 3). Similar to B6, the classification score for these ependymomas was too low and not considered as valid. Nevertheless, version 12.5 of the classifier was able to identify them as ependymal tumors.

It is important to note that methylation analysis in ependymal tumors results in a complete overhaul of the classification system. This approach eliminates the need for additional classifications since the individual methylation categories can already identify more homogeneous patient groups in terms of prognosis compared to the previous WHO classification. A notable feature of ependymomas is the observation that tumors in different locations appear to represent distinct entities, despite having similar histology [

3,

4].

Even though advances in the ependymoma methylome are evident, there are still aspects to be clarified. According to Capper et al. [

4], some tumors with morphology suggestive of ependymoma did not correspond to any ependymal methylation class in the classifier. This likely indicates the existence of other classes with histological characteristics of ependymomas that have not yet been defined, which could explain the unclassifiable cases in our cohort.

The Classifier

The Classifier is subject to continuous updates, recognizing more tumor entities with each new version. This evolution is promising, as our understanding of new classes and entities advances, the scope of the Classifier expands concomitantly [

3,

4]. Thus, we can say that the broader classification potential of version 12.5 is empirically related to deep learning training and improved quality controls, making it more stringent.

Challenges in SUS routine diagnostics

The results demonstrate that DNA methylation profiling is valuable for the clinical diagnosis of CNS tumors in the Brazilian public health system. However, the high costs and extended processing time associated with methylation arrays pose challenges for their routine use in Brazil. These factors limit their adoption, necessitating further evaluation and consideration before widespread implementation in the SUS framework.

Materials and Methods

Case Selection

All 16 FFPE blocks were obtained from the archives of the Division of Pathology at the Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, and correspond to CNS tumors from patients treated at the hospital. The samples included cases of medulloblastoma and ependymoma, whose molecular subclassification has diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic relevance. We excluded cases without a prior diagnosis for comparison and samples outside quality parameters. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Project Analysis of the Clinical Directorate of Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo (Approval Number: 5.537.550).

Epigenomic Arrays

Bisulfite conversion was performed using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research®) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with the alternative cycling suggested for methylation array assays (95ºC for 30 seconds, 50ºC for 60 minutes) x 16 cycles. After conversion, the samples underwent a pre-array restoration step as indicated by the manufacturer, Illumina. The process used the Infinium HD FFPE Restore Kit (Illumina®) and the ZR-96 Genomic DNA Clean & Concentrator Kit (Zymo Research®). Together, they perform an isothermal PCR restoring the genomic regions covered by the BeadChip array and of clinical interest. The DNA was processed using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation EPIC BeadChip array (Illumina®) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The BeadChip was scanned by iScan, generating raw data in .idat format.

Data Analysis

The raw data files generated after scanning (.idat) were submitted to the online DNA methylation classifier for CNS tumors at

https://www.molecularneuropathology.org. A report was generated for each tumor in versions v11b4 (created in 2017) and v12.5 (created in 2022), providing prediction scores for methylation classes and CNV estimation graphs. All samples were compared with histopathological findings, as proposed by Capper and colleagues in 2018 [

4].

In parallel, we conducted additional analyses in R Studio (v4.3.2), following the pipeline proposed by Maksimovic et al [25], with modifications. This allowed us to perform more accurate data quality control, verifying the quality of extraction and the performance of the array technique. The processing involved normalizing raw data and quality control. Raw signal intensities were obtained from .idat files using the minfi Bioconductor R package (v1.48.0). Quality control involved the average detection p-value, flagging as low signal quality for averages >0.01. Filtering criteria included the removal of probes targeting the X and Y chromosomes, probes containing SNPs (Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms), and cross-reactive probes.

Furthermore, a dissimilarity matrix plotted in a PCoA (Principal Coordinate Analysis) graph was generated post-processing to compare the methylation profiles of medulloblastomas and ependymomas. All graphs were created using the ggplot2 package (v3.4.4) in R Studio. Additionally, we submitted the entire case series to EpiDiP (Epigenomic Digital Pathology), an online platform developed by the Institute of Medical Genetics and Pathology, University Hospital Basel, and the University of Basel, Switzerland. EpiDiP was designed to assist in the diagnosis of brain tumors through methylation data analysis, complementing the Heidelberg Classifier. The platform considers only .idat files generated from Illumina Infinium Methylation 450K and EPIC arrays to plot CNV profiles and amplifications and fusions of genes relevant for rapid and accurate visualization. EpiDiP is available at

https://www.epidip.org.

Considerations

In this study, DNA methylation profiling effectively confirmed and refined the diagnosis in 81% of cases initially evaluated by histopathology. This robust method provides a valuable diagnostic tool, particularly for challenging CNS tumors. Further refinement and validation of this approach could increase its clinical utility in the Brazilian public healthcare system, offering a more accurate and detailed understanding of CNS tumors and providing greater accuracy and depth in tumor classifications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans.

Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Cytogenomics Laboratory team and the Division of Pathological Anatomy of HCFMUSP for their support and contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of the manuscript entitled “ Implementation of methylation profiling of central nervous system tumors at largest public health center in Brazil” declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this work. All authors confirm that they have not received any funding or support from any institution or organization that could influence or have the potential to influence the content or interpretation of the results presented in this article. Furthermore, there are no financial, personal, or professional interests that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; Von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, B.; Priesterbach-Ackley, L.; Petersen, J.; Wesseling, P. Molecular pathology of tumors of the central nervous system. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, D.; Jones, D.T.W.; Sill, M.; Hovestadt, V.; Schrimpf, D.; Sturm, D.; Koelsche, C.; Sahm, F.; Chavez, L.; Reuss, D.E.; et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 2018, 555, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, D.; Stichel, D.; Sahm, F.; Jones, D.T.W.; Schrimpf, D.; Sill, M.; Schmid, S.; Hovestadt, V.; Reuss, D.E.; Koelsche, C.; et al. Practical implementation of DNA methylation and copy-number-based CNS tumor diagnostics: the Heidelberg experience. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, D.; Orr, B.A.; Toprak, U.H.; Hovestadt, V.; Jones, D.T.; Capper, D.; Sill, M.; Buchhalter, I.; Northcott, P.A.; Leis, I.; et al. New Brain Tumor Entities Emerge from Molecular Classification of CNS-PNETs. Cell 2016, 164, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovestadt, V.; Remke, M.; Kool, M.; Pietsch, T.; Northcott, P.A.; Fischer, R.; Cavalli, F.M.G.; Ramaswamy, V.; Zapatka, M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. Robust molecular subgrouping and copy-number profiling of medulloblastoma from small amounts of archival tumour material using high-density DNA methylation arrays. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome — biological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pages, M.; Uro-Coste, E.; Colin, C.; Meyronet, D.; Gauchotte, G.; Maurage, C.-A.; Rousseau, A.; Godfraind, C.; Mokhtari, K.; Silva, K.; et al. The Implementation of DNA Methylation Profiling into a Multistep Diagnostic Process in Pediatric Neuropathology: A 2-Year Real-World Experience by the French Neuropathology Network. Cancers 2021, 13, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, D.; Capper, D.; Andreiuolo, F.; Gessi, M.; Kölsche, C.; Reinhardt, A.; Sievers, P.; Wefers, A.K.; Ebrahimi, A.; Suwala, A.K.; et al. Multiomic neuropathology improves diagnostic accuracy in pediatric neuro-oncology. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, J.V.A.; Kulikowski, L.D.; Wolff, B.M.; Natalino, R.; Carraro, D.M.; Torrezan, G.T.; Neto, C.S.; Amancio, C.T.; Canedo, F.S.N.A.; Feher, O.; et al. Strong OLIG2 expression in supratentorial ependymoma, ZFTA fusion-positive: A potential diagnostic pitfall. Neuropathology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.D.; Northcott, P.A.; Korshunov, A.; Remke, M.; Cho, Y.-J.; Clifford, S.C.; Eberhart, C.G.; Parsons, D.W.; Rutkowski, S.; Gajjar, A.; et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 123, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, M.; Mobark, N.; Bashawri, Y.; Abu Safieh, L.; Alowayn, A.; Aljelaify, R.; AlSaeed, M.; Almutairi, A.; Alqubaishi, F.; AlSolme, E.; et al. Methylation Profiling of Medulloblastoma in a Clinical Setting Permits Sub-classification and Reveals New Outcome Predictions. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksimovic J, Phipson B, Oshlack A. A cross-package Bioconductor workflow for analysing methylation arraydata. F1000Res. 2016 Jun 8; 5:1281.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).