Submitted:

26 July 2024

Posted:

29 July 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Topic Modeling for Public Health

2.2. Social Media for Disaster Relief

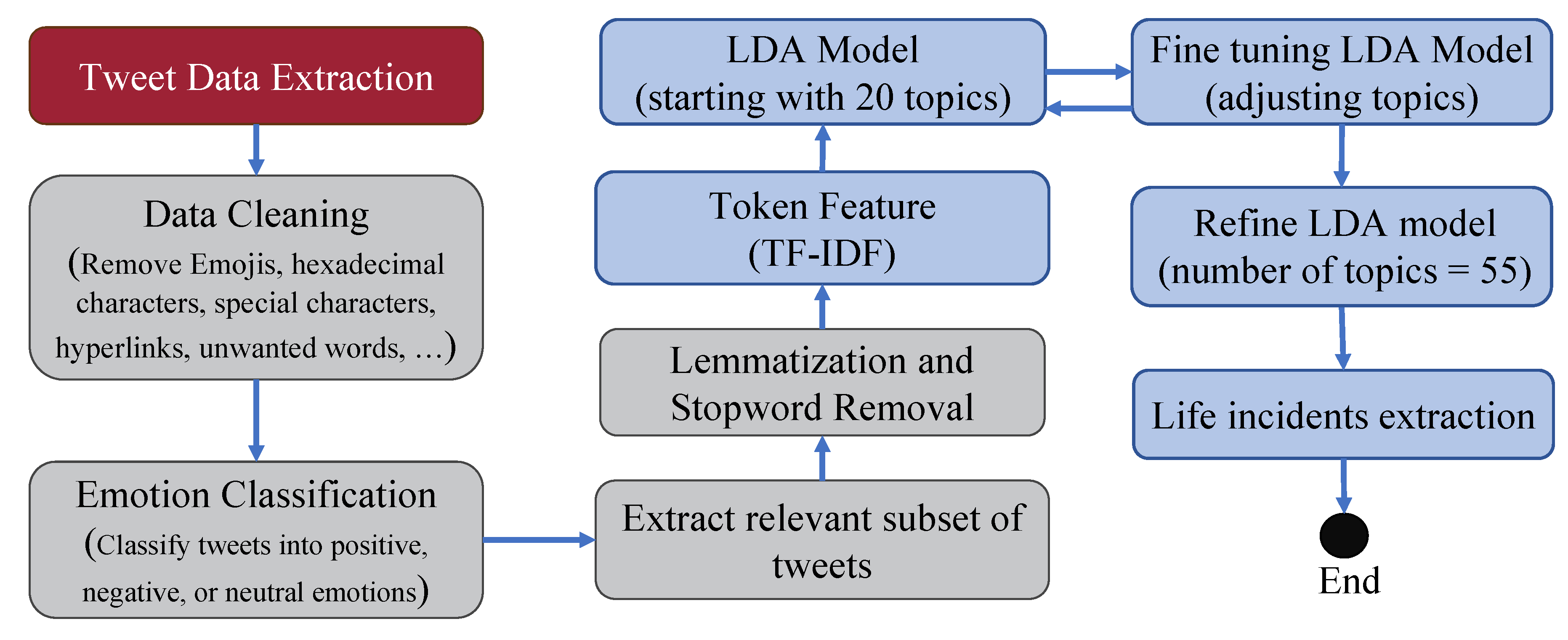

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Data Pre-Processing and Feature Engineering

3.3. Emotion Prediction and Life Incident Extraction

3.3.1. Text Vectorization

3.3.2. Emotion Prediction Model

3.3.3. LDA Topic Modeling Based Life Incident Extraction

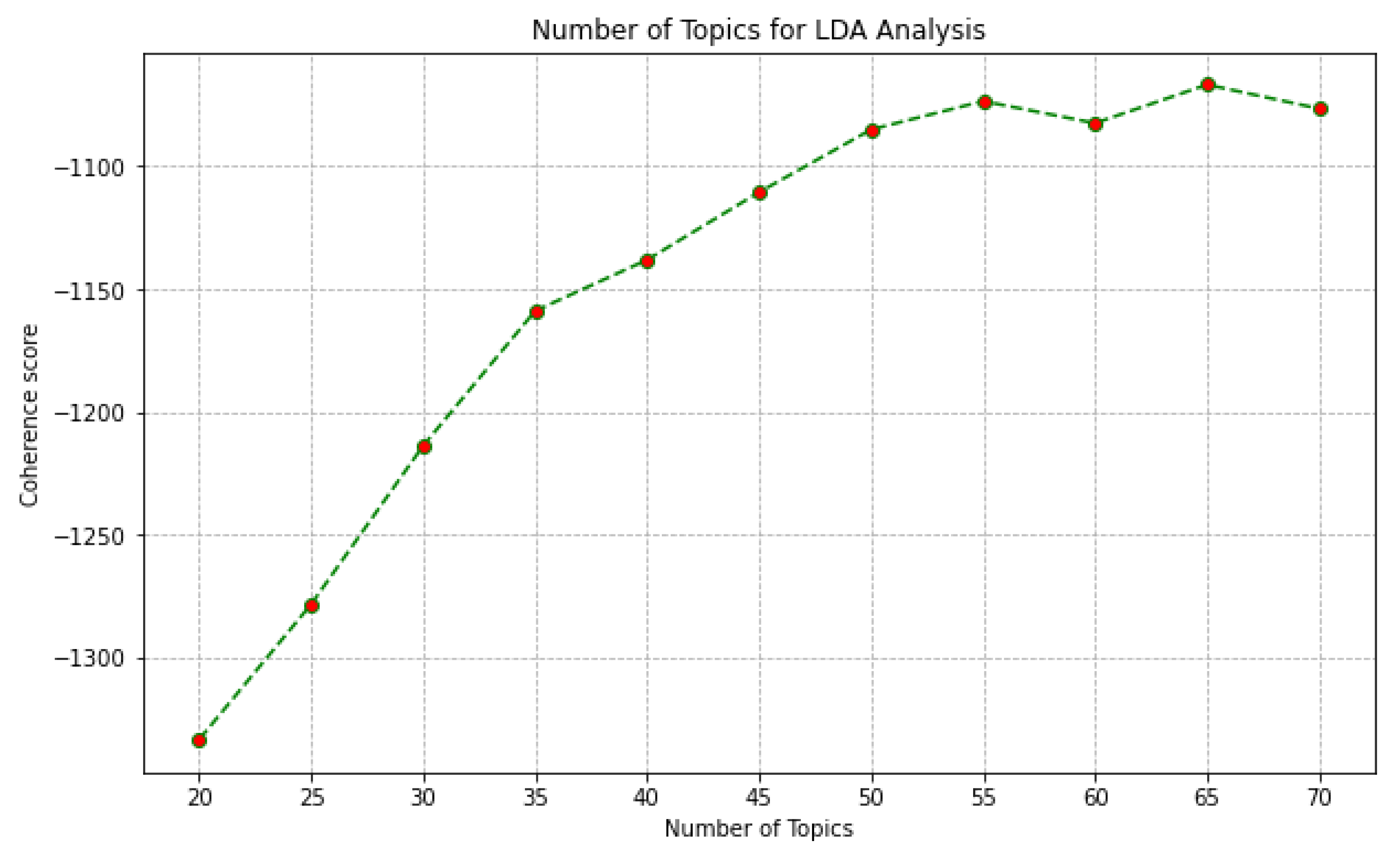

Topics Identification for Optimal Number:

Life Incident Extraction from the Identified Topics:

4. Results

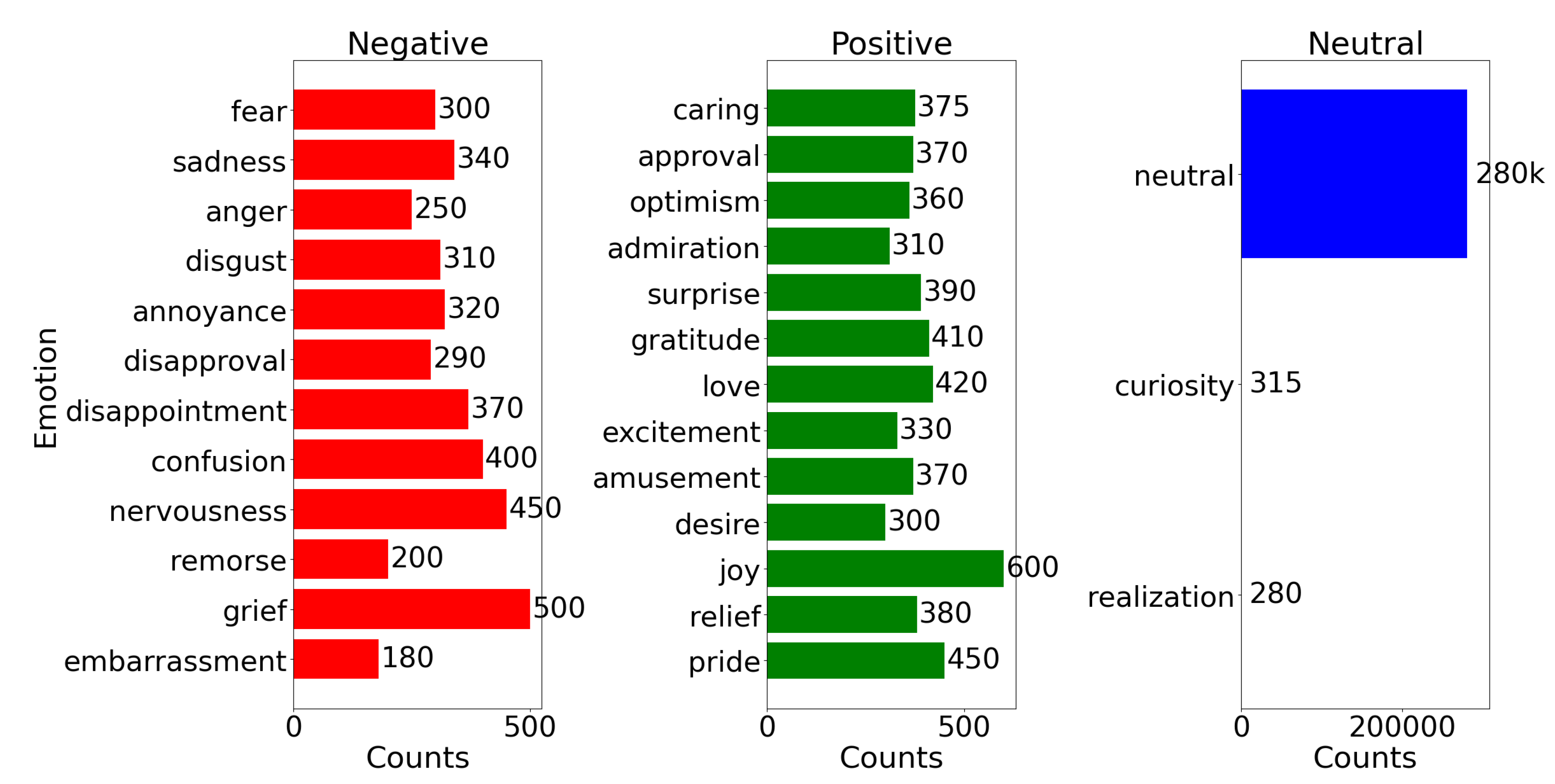

4.1. Emotion Prediction Results

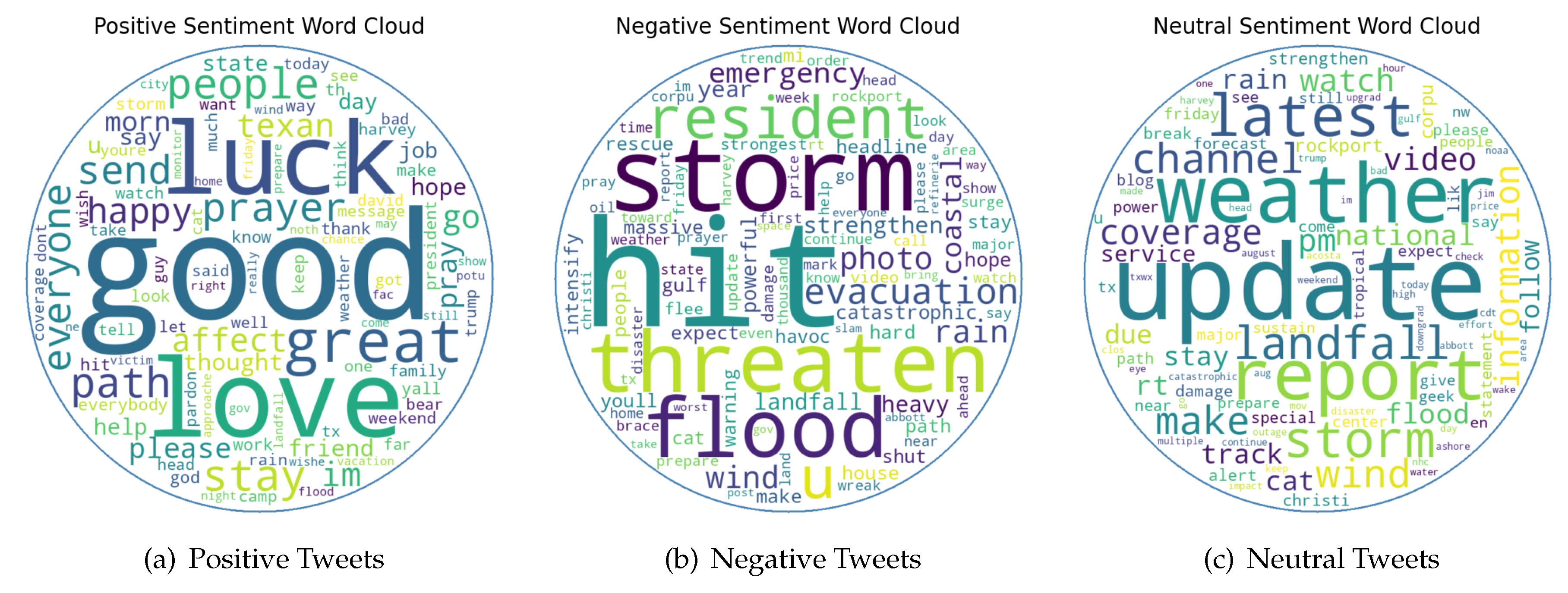

4.2. Tweets Summary by Emotions

| Positive | Neutral | Negative |

|---|---|---|

| good | update | hit |

| love | weather | storm |

| luck | report | threaten |

| great | latest | flood |

| stay | storm | resident |

| people | landfall | u |

| path | channel | evacuation |

| prayer | wind | photo |

| send | make | rain |

| everyone | information | wind |

| happy | coverage | emergency |

| im | watch | coastal |

| texan | pm | strengthen |

| go | video | year |

| affect | national | heavy |

| safe | hurricane | warning |

| wonderful | track | horrible |

| blessed | system | damage |

| joy | gov | destruction |

| support | cnn | disaster |

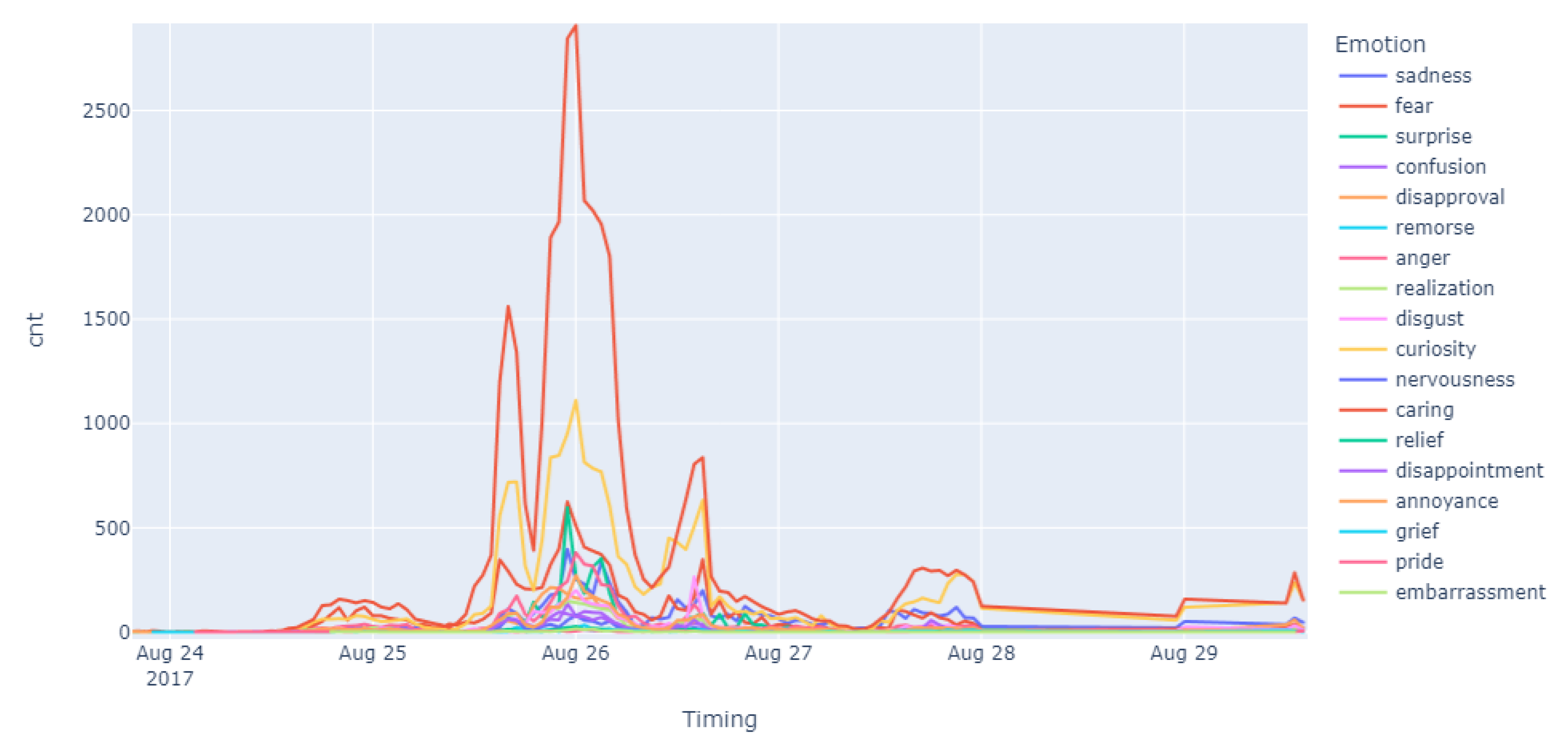

4.3. Emotions Distribution and Evolution

4.4. Life Incident Extraction Results

Life Incidents Insight Analysis

5. Limitation

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amadeo, K. Hurricane Harvey facts, damage and costs. The Balance 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, S.; Hutchings, P.; Butterworth, J.; Joseph, S.; Kebede, A.; Parker, A.; Terefe, B.; Van Koppen, B. Environmental associated emotional distress and the dangers of climate change for pastoralist mental health. Global Environmental Change 2019, 59, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, Y.; Shrestha, S.; Sharma, J. Household water insecurity, depression and quality of life among postnatal women living in urban Nepal. Journal of water and health 2016, 14, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, E.G.; Greene, L.E.; Maes, K.C.; Ambelu, A.; Tesfaye, Y.A.; Rheingans, R.; Hadley, C. Water insecurity in 3 dimensions: an anthropological perspective on water and women’s psychosocial distress in Ethiopia. Social science & medicine 2012, 75, 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. Young people and global climate change: Emotions, coping, and engagement in everyday life. Geographies of global issues: Change and threat 2016, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, E.; Wüstenhagen, R. Leading organizations through the stages of grief: The development of negative emotions over environmental change. Business & society 2017, 56, 186–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.; Hannah, A.; Madria, S.; Nabaweesi, R.; Levin, E.; Wilson, M.; Nguyen, L. Emotional Health and Climate-Change-Related Stressor Extraction from Social Media: A Case Study Using Hurricane Harvey. Mathematics 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J. Using tf-idf to determine word relevance in document queries. Proceedings of the first instructional conference on machine learning. Citeseer, 2003, Vol. 242, pp. 29–48.

- Blei, D.M.; Lafferty, J.D. Topic models. Text mining: classification, clustering, and applications 2009, 10, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Grassia, M.G.; Marino, M.; Mazza, R.; Misuraca, M.; Stavolo, A. Topic modeling for analysing the Russian propaganda in the conflict with Ukraine. ASA 2022, 2023; 245. [Google Scholar]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic, Topic Modeling with a class-base for TF-IDF procedure. Frontiers in Sociology 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Karas, B.; Qu, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Q. Experiments with LDA and Top2Vec for embedded topic discovery on social media data—A case study of cystic fibrosis. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2022, 5, 948313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, I.; Georges, D.; de Carvalho, T.M.; Saraswati, L.R.; Bhandari, P.; Kataria, I.; Siddiqui, M.; Muwonge, R.; Lucas, E.; Berkhof, J.; others. Evidence-based impact projections of single-dose human papillomavirus vaccination in India: a modelling study. The Lancet Oncology 2022, 23, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmundson, G.J.; Taylor, S. Coronaphobia: Fear and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. Journal of anxiety disorders 2020, 70, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikonda, L. Analysis and Decision-Making with Social Media; Arizona State University, 2019.

- Kaplan, A.M. Social Media, Definition, and History. In Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining; Alhajj, R., Rokne, J., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; pp. 2662–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Barbier, G.; Goolsby, R. Harnessing the crowdsourcing power of social media for disaster relief. IEEE intelligent systems 2011, 26, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, B.R. Social Media and Disasters: Current Uses, Future Options, and Policy Considerations. Technical report, Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service, 2011.

- Du, H.; Nguyen, L.; Yang, Z.; Abu-Gellban, H.; Zhou, X.; Xing, W.; Cao, G.; Jin, F. Twitter vs news: Concern analysis of the 2018 california wildfire event. 2019 IEEE 43rd Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference (COMPSAC). IEEE, 2019, Vol. 2, pp. 207–212.

- Nguyen, L.H.; Hewett, R.; Namin, A.S.; Alvarez, N.; Bradatan, C.; Jin, F. Smart and connected water resource management via social media and community engagement. 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM). IEEE, 2018, pp. 613–616.

- Yang, Z.; Nguyen, L.; Zhu, J.; Pan, Z.; Li, J.; Jin, F. Coordinating disaster emergency response with heuristic reinforcement learning. 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM). IEEE, 2020, pp. 565–572.

- Nguyen, L.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Pan, Z.; Cao, G.; Jin, F. Forecasting people’s needs in hurricane events from social network. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2019, 8, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, F.; Kumar, S.; Liu, H.; Maciejewski, R. Visualizing social media sentiment in disaster scenarios. Proceedings of the 24th international conference on world wide web, 2015, pp. 1211–1215.

- Kryvasheyeu, Y.; Chen, H.; Obradovich, N.; Moro, E.; Van Hentenryck, P.; Fowler, J.; Cebrian, M. Rapid assessment of disaster damage using social media activity. Science advances 2016, 2, e1500779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurricane Harvey Tweets. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dan195/hurricaneharvey, 2017 (Accessed Aug 06, 2023).

- Hind Saleh, A.A.; Moria, K. Detection of Hate Speech using BERT and Hate Speech Word Embedding with Deep Model. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2023, 37, 2166719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Lakra, S.; Kaur, M. Study on BERT Model for Hate Speech Detection. 2020 4th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), 2020, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- D’Sa, A.G.; Illina, I.; Fohr, D. BERT and fastText Embeddings for Automatic Detection of Toxic Speech. 2020 International Multi-Conference on: “Organization of Knowledge and Advanced Technologies” (OCTA), 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.; Bihorac, O.A.; Rouces, J. Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis using BERT. Proceedings of the 22nd Nordic Conference on Computational Linguistics; Hartmann, M., Plank, B., Eds.; Linköping University Electronic Press: Turku, Finland, 2019; pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pota, M.; Ventura, M.; Catelli, R.; Esposito, M. An Effective BERT-Based Pipeline for Twitter Sentiment Analysis: A Case Study in Italian. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.C.; Li, T.; Liu, Q.; Ling, Z.H.; Su, Z.; Wei, S.; Zhu, X. Speaker-Aware BERT for Multi-Turn Response Selection in Retrieval-Based Chatbots. Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; CIKM’20; pp. 2041–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, P. Using BERT-Based Textual Analysis to Design a Smarter Classroom Mode for Computer Teaching in Higher Education Institutions. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET) 2023, 18, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, Q.G.; To, K.G.; Huynh, V.A.N.; Nguyen, N.T.Q.; Ngo, D.T.N.; Alley, S.J.; Tran, A.N.Q.; Tran, A.N.P.; Pham, N.T.T.; Bui, T.X.; Vandelanotte, C. Applying Machine Learning to Identify Anti-Vaccination Tweets during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Weng, F.; Zhuang, M.; Lu, X.; Tan, X.; Lin, S.; Zhang, R. Revealing Public Opinion towards the COVID-19 Vaccine with Weibo Data in China: BertFDA-Based Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahali, A.; Akhloufi, M.A. MalBERT: Using Transformers for Cybersecurity and Malicious Software Detection, 2021, [arXiv:cs.CR/2103.03806].

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 2019.

- Demszky, D.; Movshovitz-Attias, D.; Ko, J.; Cowen, A.; Nemade, G.; Ravi, S. GoEmotions: A Dataset of Fine-Grained Emotions, 2020, [arXiv:cs.CL/2005.00547].

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, 2019, [arXiv:cs.CL/1810.04805].

- Chen, T.H.; Thomas, S.W.; Hassan, A.E. A survey on the use of topic models when mining software repositories. Empirical Software Engineering 2016, 21, 1843–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, T. Probabilistic latent semantic indexing. Proceedings of the 22nd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, 1999, pp. 50–57.

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of machine Learning research 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Mimno, D.; Wallach, H.M.; Talley, E.; Leenders, M.; McCallum, A. Optimizing Semantic Coherence in Topic Models. Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics: USA, 2011; EMNLP’11; pp. 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike, R. Who belongs in the family? Psychometrika 1953, 18, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; Vanderplas, J.; Passos, A.; Cournapeau, D.; Brucher, M.; Perrot, M.; Duchesnay, E. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

| Layer (Type) | Output Shape | Number of Parameter |

|---|---|---|

| input_ids | (None, 50) | 0 |

| token_type_ids | (None, 50) | 0 |

| roberta | (32, 50, 768) | 124,055,040 |

| emotion | (28, 1) | 612,124 |

| Life Incidents | Important Terms |

|---|---|

| Evacuation Plan | shelter, emergency, evacuee, free, offer, flood, help, continue, rescue, order |

| Concerns For Animals | help, dog, relief, food ,donate, cross, bag, support, away, affect |

| Climate Change Policy | video, like, change, climate, show, Twitter, en, satellite, stream, approach |

| Safety Update | update, latest, report, president, disaster, city, head, wake, great, state |

| Danger | wind, periscope, gust, day, damage, crazy, got, last, cat |

| Warnings | power, track, follow, story, top, without, bear, potential, map, update |

| Disaster response | disaster, gulf, open, border, first, patrol, brace, major, face, natural |

| Heavy Rain | rain, watch, tx, eye, Rockport, water, bring, wind, barrel, wall |

| Care of Family and Friends | stay, everyone, please, hope, friend, good, path, ready, family, roar |

| Oil and Gas Price Rise | price, prepare, gas, oil ,damage, major, san, governor, rise, cause |

| Help | space, station, seen, nasa, international,cupola, victim, help, view, donation |

| Fake News | path, look, like, monitor, David,camp, closely, fake, reporter, arrive |

| Flood | flood, hit, coverage, weather, house, week, channel, miss, hope, next |

| Praying | prayer, pray, affect, path, thought, everyone, people, god, go, know |

| Catastrophe | flood, catastrophic, post, due, flee, thousand, storm, rainfall, intensifies, upgrade |

| Evacuation news | center, national, say, pm, forecast, dog, number, one, threat, evacuate |

| Landfall Preparedness | landfall, make, corpus, storm, christi, near, made, hit, could, southeast |

| Mindsets | people, pardon, dont, Arpaio, evacuate, think, racist, good, would, coldplay |

| Hurricane Downgrade | storm, wind, strengthen, cat, break, toward, threaten, downgrade, year, high |

| Life Incidents | Important Terms |

|---|---|

| Updated report | report, update, video, track, special, alert, lik, price, satellite, watch |

| Weather Update | weather, see, update, bad, report, could, story, rain, top, latest |

| Channel | weather, channel, coverage, blog, geek, video, lik, due, condition, severe |

| Statement | power, en, weather, update, outage, report, wake, el, statement |

| Hurricane Report | report, weather, storm, hurricane, damage, rain, southeast, lash, help, wind |

| Weather Channel | weather, report, stay, channel, people, watch, go, pray, due, reporter |

| Updates | report, prepare, effort, jim, multiple, acosta, ignore, apparently, update, continue |

| Catastrophic Flood Updates | update, report, follow, latest, catastrophic, flood, expect, rockport, damage, due |

| Information | update, pm, strengthen, storm, aug, report, cdt, information, wind, cat |

| Weatherforecast | weather, information, forecast, best, track, last, predict, update, aug, know |

| National Updates | update, report, txwx, weather, periscope, jeffpiotrowski, center, beach, national, add |

| Weather Report | update, wind, weather, report, cat, kt, stay, mov, tonight, mb |

| Statement Report | update, latest, statement, pm, watch, report, day, gulf, et, without |

| Latest Information | report, corpus, information, christi, near, tx, landfall, latest, make, update |

| Damages Updates | update, latest, major, please, water, damage, stay, br, wind, weather |

| Latest Report | update, storm, downgrade, tropical, report, latest, Saturday, flood, head, toward |

| Landfall Updates | update, landfall, latest, make, weather, service, national, storm, expect, made |

| Storm Report | wind, weather, sustain, report, update, storm, max, maximum, cat, eye |

| Safety Statement | update, come, center, storm, ashore, upgrade, weather, noaa, safety, statement |

| Alerts | update, give, Friday, abbot, break, greg, school, alert, August, gov |

| Life Incidents | Important Terms |

|---|---|

| Great Day | good, weather, great, dog, show, food, day, side, many, bag |

| Relief | great, would, love, help, could, relief, storm, change, climate, like |

| Happy Friday | good, day, pardon, friday, happy, great, arpaio, real, im, though |

| Luck | good, morn, luck, gulf, people, wish, cat, storm, love, rain |

| Good Coverage | good, far, im, happy, coverage, great, watch, power, get, keep |

| Wishes | good, luck, everybody, bear, wish, like, love, hit, bad, im |

| Farewell | good, luck, prepare, ahead, heartless, bid, farewell, shareblue, love, hear |

| Good Vacation | head, good, vacation, fac, luck, great, yell, crassly, love, stay |

| Great Government | great, state, work, city, noth, gov, monitor, chance, federal, closely |

| Good Job/Help | love, job, great, good, director, handle, bug, laud, agency, help |

| Helping | good, luck, love, help, victim, better, dont, deserve, near, go |

| Good Camp | good, luck, great, tell, camp, david, way, president, watch, doesnt |

| Prayer | love, prayer, stay, send, path, everyone, thought, affect, good, people |

| Good Message | good, luck, path, message, people, everybody, approach, say, said, word |

| Blessing | god, love, great, good, hit, bless, help, thank, die, pray |

| Birthday | happy, love, thank, birthday, take, keep, great, ill, wait, away |

| Good Luck | good, luck, get, corpu, go, th, look, people, like, say |

| Happy Weekend | weekend, great, good, im, love, happy, let, go, cover, look |

| Wind | good, great, make, landfall, go, love, impact, still, morn, wind |

| Praying | pray, good, everyone, love, affect, hop, first, day, great, night |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).