1. Introduction

Since its identification in the 1970s, "burnout" has become a focal point within occupational health discourse, amassing over 1.44 million mentions in scholarly research as of January 2024 (Google Academic search). The profound impact of burnout on everyday functioning led the World Health Organization to categorize burnout syndrome in its 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as specifically linked to occupational contexts [

1]. The exigencies of the COVID-19 pandemic brought this issue into sharper focus, revealing an escalation in mental health challenges during lockdowns, particularly highlighting the vulnerability of healthcare workers to burnout [

2,

3].

Burnout affects not only the mental and physical health of individuals, potentially leading to conditions such as depression and anxiety [

4], but also their job performance. Its repercussions extend to reduced organizational commitment, increased turnover, and absenteeism [

5,

6], all of which challenge the sustainability of educational systems and institutions.

Efforts to mitigate and address burnout encompass person-centered and situation-centered strategies, with recommendations ranging from modifying work patterns and reducing workloads, to fostering skills in coping, time management, and conflict resolution. Enhancing overall health through balanced lifestyle choices, nutrition, and exercise, alongside understanding employee personalities and needs, are crucial components [

7].

Measurement of burnout employs various tools, including the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [

8] and alternatives like the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, and the Professional Quality of Life Measure (ProQoL5). Emerging technological approaches include sensors for monitoring physiological markers like cortisol, and wearables for assessing wellness and preventing burnout [

9,

10,

11].

Innovations utilizing Artificial Intelligence (AI) and fuzzy logic have brought about holistic and multi-criteria approaches for detecting burnout [

12], analyzing personality traits and their responses to stressors, thus facilitating early intervention and contributing to educational sustainability [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Burnout syndrome has been first identified in the context of health-related workers and continues to primarily affect them [

5], [

17,

18,

19], but it also affects professionals from other fields such as: education [

20,

21,

22], legal and justice system [

23], software development [

24,

25,

26] and many other [

27,

28].

Recent concerns regarding burnout in the field of education have as subjects both students and teachers. Students as subjects are addressed in studies related to well-being, behavior and attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic period [

29,

30], burnout and the teaching-learning environment perceptions [

31], and include all types of students including PhD candidates in medicine [

32]. Teachers as subjects include different educational cycles such as primary school [

33], secondary school [

34], high school [

35,

36] and higher education [

37]. Comparative analyses before vs. during the COVID-19 pandemic are also reported together with comparison with other occupational categories [

38].

The studies dedicated to school principals are not so numerically significant. Nevertheless, the ability of students, teachers, parents, and principals to cope during the COVID-19 pandemic was the focus of a study by [

39] that looked at three latent profiles of school principals' stress.

Our research introduces a novel, culturally specific methodology for assessing burnout among Bedouin school principals in Israel, examining the interplay between organizational climate and physiological stress indicators like heart rate (HR). It proposes a fuzzy tool that integrates HR and organizational climate data, aiming to enhance the resilience and sustainability of educational leadership in challenging times.

The issue of school principals’ burnout has garnered increasing attention in recent years, particularly in the context of sustainable education. Sustainable education emphasizes long-term, holistic approaches to learning that consider environmental, social, and economic factors. However, the pressures associated with implementing these comprehensive strategies can contribute significantly to principals’ burnout. The complexity of the principalship has increased, with added responsibilities such as managing diverse student needs, navigating bureaucratic systems, and maintaining high academic standards [

40]. These demands often lead to mental and physical exhaustion, which is exacerbated by the lack of adequate support from central office administrators and school boards.

Despite the critical role that principals play in fostering sustainable education, the incidence and implications of their burnout have not been sufficiently studied. The literature indicates that principal burnout can lead to high turnover rates, which in turn disrupts the continuity and effectiveness of school leadership. This disruption can negatively impact the implementation of sustainable education initiatives, as new principals may lack the experience or knowledge to continue these programs effectively. Furthermore, burnout among principals can diminish their capacity to support teachers and students, thereby undermining the overall educational environment [

41].

Given the significant implications of principal burnout, it is essential to explore strategies to mitigate this issue [

42]. Research suggests that providing principals with more robust support systems, including professional development opportunities and mental health resources, can help alleviate some of the stressors associated with their role. Additionally, fostering a collaborative school culture where principals feel supported by their peers and superiors can also reduce feelings of isolation and burnout. However, more empirical studies are needed to understand the full extent of principal burnout and to develop effective interventions tailored to the unique challenges of sustainable education.

The limited focus on principal burnout may stem from broader research trends that typically group various educational leadership roles together, without distinguishing the unique challenges faced by principals. Existing studies often generalize findings across educational leadership without considering the specific contexts and demands faced by school principals. Moreover, the nuanced impact of burnout on principals—such as its effect on decision-making, leadership effectiveness, and school climate—is not well-documented in the literature. This gap in research is concerning because the well-being of principals is intrinsically linked to the operational health of schools and the educational experiences of both students and teachers. Addressing this oversight in future research could lead to more targeted interventions designed to support principals specifically, thereby enhancing the overall sustainability and effectiveness of educational institutions.

Our research presents a new approach regarding the burnout syndrome that targets a community with a high degree of specificity given the profile of the school principal in the Bedouin area of Israel, consists of a study carried out to observe how the organizational climate and the physiological parameter heartrate (HR) is reflected in the state of stress and proposes the application of a fuzzy tool, which has as inputs HR values and the relevant dimensions of the organizational climate in the context of the studied community.

Through this study, we seek to contribute to the existing literature on educational burnout by providing insights into a critical yet overlooked area of educational leadership, with the goal of enhancing the sustainability and effectiveness of educational systems through more targeted interventions for school principals in very specific area, namely Bedouin area from Southern Israel.

The novelty of this research lies in its integration of fuzzy logic modeling with the assessment of stress levels in educational leaders, specifically school principals, a focus that has been less explored in existing literature. Unlike traditional analytical approaches, the use of a fuzzy logic system allows for the processing of uncertain and imprecise data, reflecting the complex and often subjective nature of stress and its triggers. By incorporating identified key organizational climate dimensions as inputs, the model adeptly handles the nuanced interactions between these factors and their impact on stress, predicting stress outcomes in scenarios where data may not be strictly binary or uniformly measured. The approach can lead to more personalized and effective solutions in combating burnout and enhancing institutional sustainability.

The two main objectives of our research are:

Develop and implement a fuzzy logic model for stress estimation, based on the complex relationships between climate dimensions identified in a prior research, physiological parameter heartrate and stress levels. By employing the Mamdani fuzzy model, the research intends to handle the imprecision and variability inherent in human emotional responses, providing a tool for predicting stress levels based on organizational climate inputs.

Validate the fuzzy logic model through synthetical data. By applying the model to full range of possible scenarios within school environments, the research seeks to ensure the model's reliability and accuracy in predicting stress, thereby enhancing its practical application in developing targeted interventions for stress management among school principals.

The structure of the paper is designed to systematically address the research objectives identified. It begins with a comprehensive Introduction that presents an extensive literature review, leading to the research problem, identification of gaps, and formulation of specific research objectives. Following the introduction, the 'Materials and Methods' section elaborates on the research approach and methodology, detailing the experimental protocol, data collection, and preprocessing methods used in the study. This section prepares the components of the experiment design, which introduces the Fuzzy Intelligent System, explaining its operational framework and role in the study. The robustness and effectiveness of this system are then examined in the 'Results and Discussion' section, where the system's validation is discussed, illustrating how it meets the study's initial objectives. The paper ends with the 'Conclusion' section, which summarizes the findings and their implications and outlines the limitations encountered during the research and suggests potential areas for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

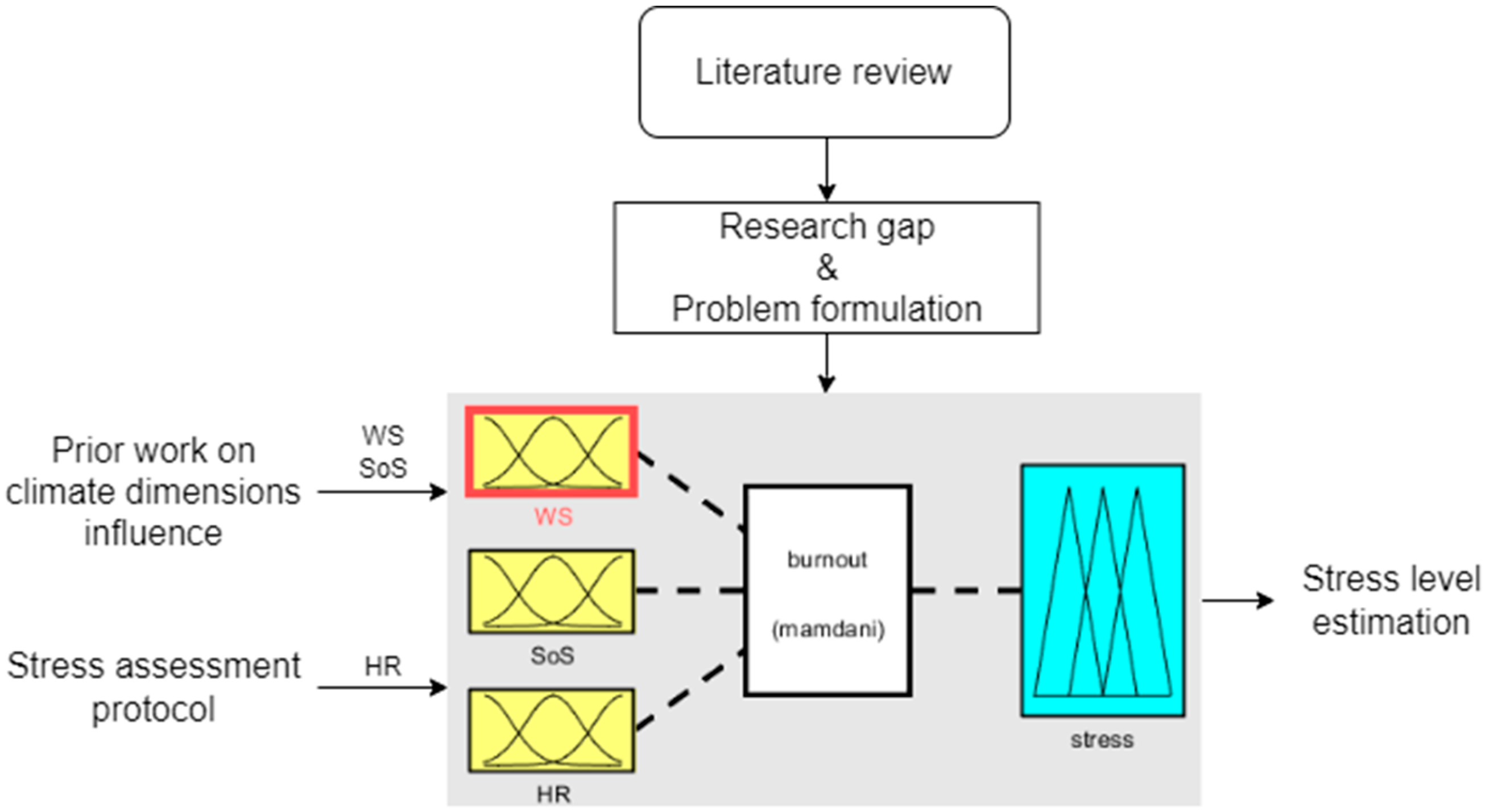

The research methodology depicted in

Figure 1 is designed to assess stress levels by integrating both psychological and physiological factors focusing on school principals. The process begins with an extensive literature review aimed at understanding the existing body of knowledge on stress, burnout, and their determinants within educational settings. This comprehensive review helps identify existing gaps, leading to a clear formulation of the research problem, which in this study concentrates on how workplace conditions such as Work Satisfaction (WS) and Sense of Security (SoS), along with physiological indicators like Heart Rate (HR), contribute to burnout and stress levels.

Building on this foundation, the research methodology incorporates insights from prior studies on the influence of organizational climate dimensions—such as WS and SoS—on stress and burnout. These factors have been historically linked to psychological outcomes and are crucial for understanding the environmental impact on stress levels. In conjunction with this, the methodology employs a stress assessment protocol that includes the measurement of HR as a physiological indicator of stress, reflecting the direct impact of both environmental and biological factors on an individual's stress levels.

Central to the methodology is the use of a fuzzy logic inference system, which is particularly suited for handling the imprecisions and uncertainties inherent in human factors research such as stress assessment. The model processes input variables (WS, SoS, and HR) through fuzzy sets that allow for varying degrees of association rather than binary states, using a set of rules derived from expert knowledge and empirical data to map out how these inputs interact to influence stress levels.

The output from the model provides a fuzzy estimation of stress levels, which can be converted into a crisp, practical value representing the stress level on a continuous scale. This approach not only enhances the understanding of how different factors interact to impact stress but also aids in the development of targeted interventions and support mechanisms tailored to the specific needs of educational leaders. By bridging theoretical research with practical applications, the methodology offers a comprehensive tool for addressing the complexities of stress in educational settings.

The initiation of the research from the current paper was prompted by observations from a school psychologist who, through deep familiarity with the Bedouin community in southern Israel, identified a prevalent issue of stress potentially leading to burnout among school principals. This observation underpinned the need for a systematic approach to quantify and analyze these stress levels scientifically.

2.1. Settings for the Experiment

The empirical phase of our study began in a prior work [

43] with a statistical examination of burnout among school principals, utilizing a sample of 30 out of the total 35 school principals in the Bedouin area. This assessment was conducted using the Principal's Burnout Scale [

44] which includes 22 items categorized into three major dimensions: burnout, isolation, and dissatisfaction with others. Alongside this, we administered a questionnaire to evaluate the school organizational climate, derived from the Meitzav evaluation system. This questionnaire assesses various factors including Work Satisfaction, Satisfaction on Management, Sense of Security, Conditions of Prolonged Stay, Professional Development, Teamwork, Autonomy of Teachers, and Leadership.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated the adaptation of our study into a longitudinal format, extending our observations to capture data during and post-pandemic periods. This transition allowed us to gather comparative insights across three distinct time frames. Analysis of this longitudinal data revealed a significant negative correlation between the principals’ perceived organizational climate and their burnout levels, aligning with findings from prior studies on climate-burnout relationships [

21].

Further investigation focused on the relationship between the leadership approach of principals, using the Bolman and Deal model [

45], and their levels of burnout. Measurements across the four frames of this model—structural, human resource, political, and symbolic—showed negative correlations with burnout levels. The results obtained from the study on the 30 school principals in the context of the conceptual approach proposed by Bolman and Deal [

45] showed the average values for each of the four frameworks: structural (M=3.10), human resource (M=2 .38), political (M=2.87) and symbolic (M=2.80) and negative correlations with burnout level. In terms of managerial effectiveness and leadership, 84% and 79%, respectively, rated themselves as effective compared to other managers, of which 37% and 36%, respectively, ranked in the top 20%. Despite the fact that a high percentage of principals self-rated as effective in leadership and management (84% and 79%, respectively), our analysis indicated that these self-assessments did not necessarily correlate with lower burnout levels [

46].

Finally, our study confirmed that demographic variables such as gender, age, seniority in school, overall work experience, and educational level did not significantly impact the burnout levels and thus were excluded from further consideration in the analysis. The longitudinal aspect of the study reinforced the importance of Work Satisfaction and Sense of Security as consistent predictors of burnout, demonstrating that Leadership and Satisfaction on Management did not have a substantial impact on burnout levels [

43]. This insight directs future research to focus on these stable dimensions within the organizational climate as crucial factors in managing and understanding burnout among school principals.

Considering the results of the longitudinal study from the pre- to the post-pandemic period, which highlight a negative correlation between burnout and the same two dimensions of the organizational climate for the analysed target group, between October 22nd and November 15th 2022, the following study was carried out in order to identify the role of the HR physiological parameter in determining the state of stress. This parameter, together with the two dimensions of the organizational climate, will constitute the input elements in the fuzzy system for estimating the state of the subject.

2.2. Experiment Description

The study had the following attributes:

Participation was made on a voluntary basis, the elements of confidentiality of personal data being mutually agreed upon.

The maximum discussion duration set was 60 minutes, but relevant data was collected in an average of 30-40 minutes.

The team that carried out the study included:

A certified psychologist, who conducted the discussion part with each subject and recorded the minute and second of each moment in which the stress or calming of the subject took place.

Two technicians, who monitored the subject's physiological HR fluctuations.

The study was carried out in two stages within the unstructured interview:

Stage 1 consisted of a survey that allowed the psychologist to identify emotional topics that cause stress or calm/relaxation. In this way, one topic of stress and 2-3 topics of relaxation were identified, based on the mimicry of the subjects, the physical discomfort displayed or expressed in the communication with the psychologist.

Stage 2 consisted in using these elements for alternating moments. The psychologist chose strong stimuli for de-stressing, as it is known that elements of stress are always strongly felt, but it is more difficult to calm down the subject after a stressful situation. Given the field of activity of the studied group, discussions related to the thirst for knowledge, successes/happy moments that led to the fulfilment of wishes or plans of subjects with a positive impact for them were discussed as calming elements. Also, within this stage, to succeed in the transition to the period of calming the subjects, the psychologist used the ways in which they managed to face difficult situations from the past as moments of awareness. In fact, the subjects found for themselves that although the narrated situation had a strong negative impact, they found the necessary strength to overcome it. This awareness helped a lot in many of the situations where the subjects remained anchored in increased stress.

The study did not start with a standard calming or stress session, but the discussion with each subject was left free to eliminate the feeling of a laboratory experiment. The subject was allowed to speak freely, and the psychologist "pressed" the identified buttons related to the discussion held and adapted to the openness of each subject. Elements of stress alternated with elements of calming.

At the end of the experiment, the psychologist and the technician correlated the recorded data.

In total, during the experiment, from the 6 volunteer subjects over 5000 raw data were acquired using the same HR measuring devices for all the subjects. These raw data were cleaned and labelled, with the states Normal, Joy, Stress, according to the observations of the psychologist during the experiment. Only one subject had a single fluctuation Normal-Stress during the experiment, all the others had up to 6. Summing up, an average of 4 fluctuations were identified during the session's average duration of 33 minutes.

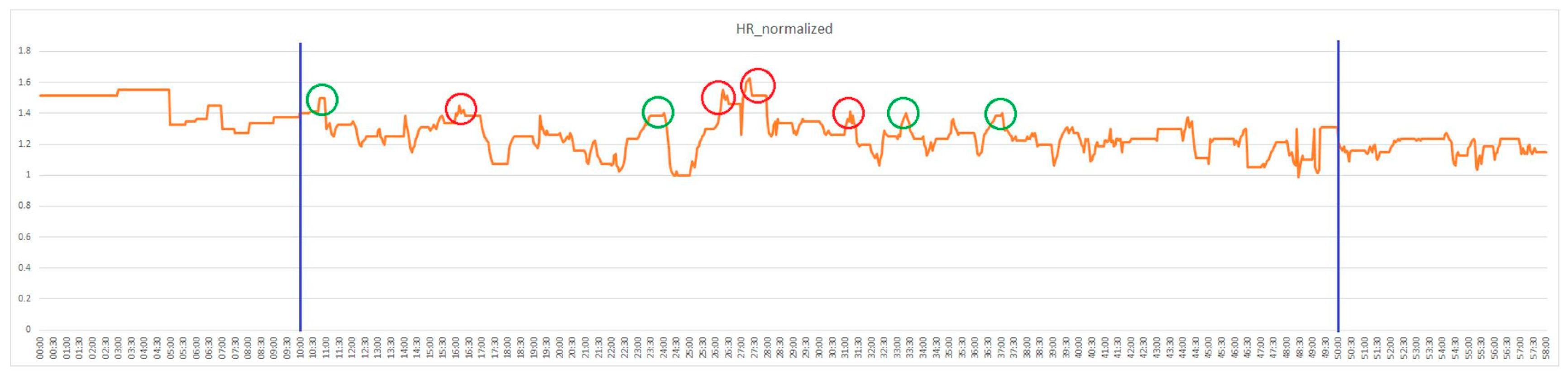

Figure 2 shows an example of labelled data collected for one of the subjects, in which the HR fluctuations during the experiment can be seen. It was graphically represented the percentage of change of the measured HR compared to the base HR. The base HR levels that were used in the processing of the acquired data are those established in the specialized literature differentiated by gender of the subject. Such normalization is common in studies focusing on physiological responses over time, allowing for clearer insights into patterns and anomalies.

Important findings are:

More than 80% of the collected data show a correlation between psychological observations and the level of the physiological parameter HR.

For about 15% of the data, a constant delay was observed between the psychological observation and the measured HR level, which is related to the fact that certain subjects have a harder time transitioning from stress to relaxation.

The remaining data were not validated. Reasons may be the lack of harmony with the discussions generated during the interview.

A very important finding is the fact that the subjects reacted by increasing HR to moments of strong emotion, both to moments of stress and to moments of great joy. It is therefore not possible to differentiate between great joy and stress based on HR alone. Therefore, the research will consider organizational climate elements to differentiate between the two.

3. Fuzzy Intelligent System

The Fuzzy intelligent system (FIS) was designed in the following three steps:

Step 1: Selection of the inputs and output linguistic variables.

The inputs that have been identified in the previous research as relevant for the assessment of burnout state for the school principals from the southern Israel are: Work satisfaction and Sense of security, both variables of the organizational climate, and HR physiological parameter, in a normalized form, as follows:

The output is the variable level-of-stress, evaluated for alarming the subject regarding the current state to find coping techniques to prevent reaching burnout.

Step 2: Defining the fuzzy sets for each of the variables.

Each linguistic variable has a membership function, which maps elements from the variable’s range of values to values within the interval [0,1]. This research uses triangular and trapezoidal fuzzy sets for the inputs, due to their simplicity.

The membership function of triangular fuzzy set (a, m, b) can be calculated according to the following equation:

Where a and b are values related to the range of values of the input and m is in the [a,b] interval.

Similarly, can be calculated the membership function of trapezoidal fuzzy set.

For the output there was used trapezoidal fuzzy sets due both to their simplicity and the fact that we need intervals of values represented.

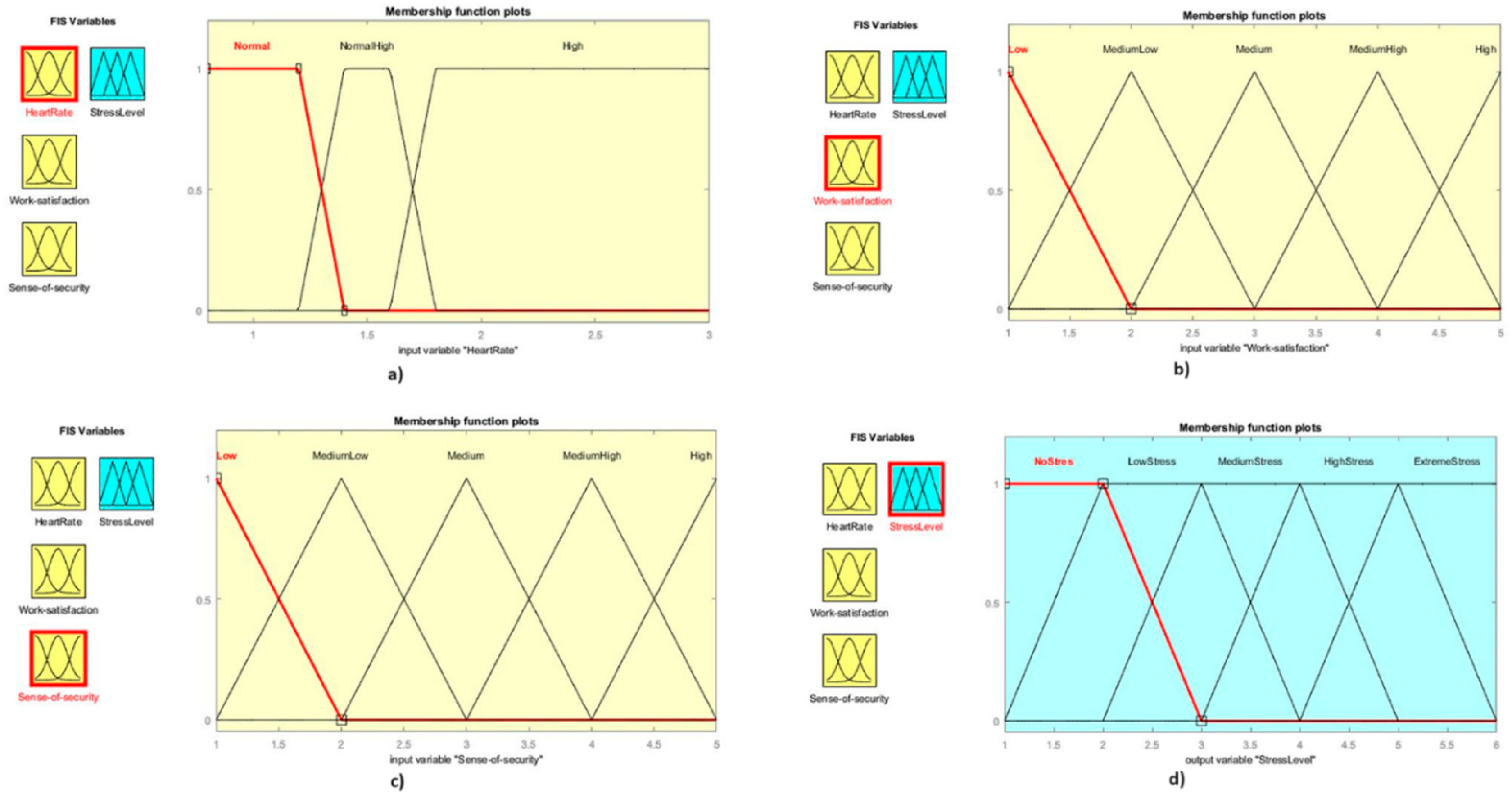

In

Figure 3 are presented the elements of the fuzzy system.

Figure 3A presents the membership function for HR input. There were considered two linguistic values that denote normal HR, that are Normal for HR around the HR

base and Normal-High that presents a slight growth of the HR above HR

base, around the 1.2 of HR

base. The High HR is considered above 1.5 of HR

base.

Figure 3B,C present the membership functions for the relevant variables that characterize the organizational climate, that are Work satisfaction and Sense of security. For both, there were considered five linguistic values that are related to the five Likert scale, from 1 – Low to 5 – High.

The trapezoidal fuzzy sets for stress level are presented in

Figure 3D being defined based on the Friedman scoring.

All the membership functions were calibrated manually, through tests, to get an appropriate system response.

Step 3: Defining the fuzzy rules that associate fuzzy inputs to fuzzy output

Linguistic rules used in the FIS design are expressed in the form ‘If premise then consequent’, where premises represent values of the FIS input variables and consequent are associated with the FIS output value. The number of the FIS inputs and output determine the number of rules based also on the number of elements in the premises and consequents. The rules on how to assess the stress state were derived based on the organizational climate assessment questionnaires and the stress assessment protocol based on HR.

For Low Work satisfaction and Low Sense of security, regardless the Heartrate, the Stress level is considered Extreme. For High Work satisfaction and Low Sense of security, regardless the Heartrate, the Stress level is considered Medium, that is also the case for Medium Work satisfaction and Medium Sense of security.

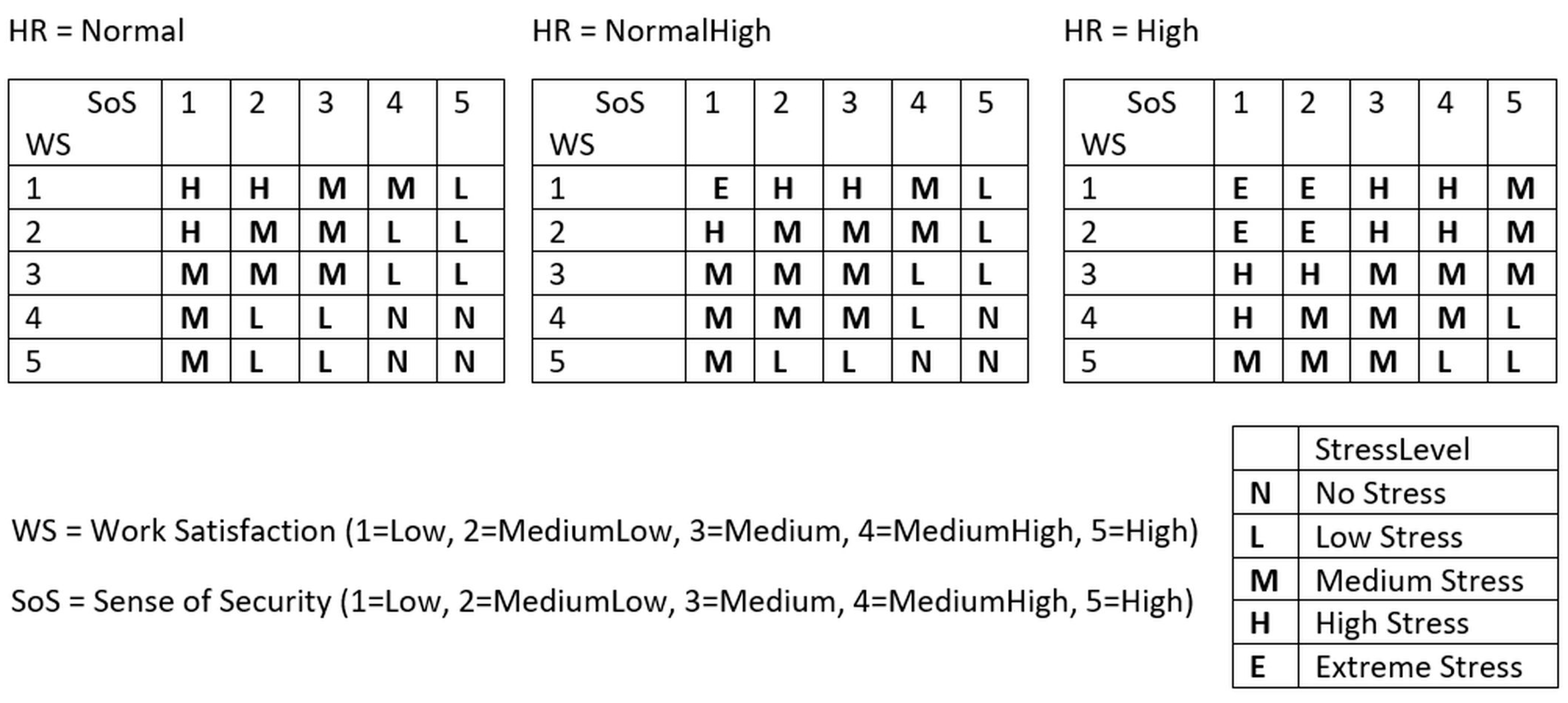

The other rules are derived from the identified matrixes from

Figure 4, used for estimating stress levels based on the interaction between heart rate (HR) conditions and two key workplace variables: Work Satisfaction (WS) and Sense of Security (SoS). Each table corresponds to a different HR condition—Normal, NormalHigh, and High— and outlines the predicted stress level from No Stress (N) to Extreme Stress (E) based on the combination of WS and SoS scores, both of which range from 1 (low) to 5 (high).

In the "HR = Normal" scenario, the stress levels predominantly range from No Stress to Medium, indicating a generally lower stress level when the heart rate is within normal ranges. As the HR condition intensifies to "NormalHigh," the occurrence of higher stress levels becomes more prevalent, with stress levels such as High (H) and even Extreme (E) beginning to appear, especially at lower levels of Work Satisfaction and Sense of Security. In the "HR = High" condition, the matrix shows a clear shift towards higher stress levels across almost all combinations of WS and SoS, with Extreme Stress (E) appearing most frequently when both WS and SoS are at their lowest levels. This systematic approach demonstrates how varying HR conditions, combined with differing levels of work satisfaction and security, can significantly influence the perceived stress levels, suggesting a complex interplay between physiological responses and workplace environment factors in determining overall stress.

4. Results and Discussions

The validation of the fuzzy model through synthetic data provides a robust method for examining the model's efficacy and accuracy in predicting stress levels based on varying inputs. In this approach, the fuzzy surfaces generated for the three primary inputs—Heart Rate (HR), Work Satisfaction (WS), and Sense of Security (SoS)—play a crucial role. By systematically altering these input values across a pre-defined range and observing the corresponding outputs, we can visualize how the model responds to different levels of HR, WS, and SoS. This method effectively simulates a wide array of real-world conditions, offering a detailed view of the model’s behaviour under controlled, yet comprehensive, scenarios. The surface plots derived from these simulations illustrate the complex interactions between the inputs and their cumulative impact on stress levels, thereby providing a visual and quantitative method to validate the model's predictions.

Further enhancing the validation process, the synthetic data allows for the exploration of edge cases and boundary conditions that may not be frequently encountered in real-world data sets but are critical for testing the model's limits and robustness. For instance, extremely high or low values of HR combined with varying degrees of WS and SoS can reveal the model’s sensitivity and performance under extreme stress scenarios. These tests help to ensure that the output is both accurate and reliable across all possible input combinations. Such a comprehensive validation approach proves the model’s practical utility in predicting stress levels with significant accuracy and underscores its adaptability and scalability to different educational settings where stress factors might differ.

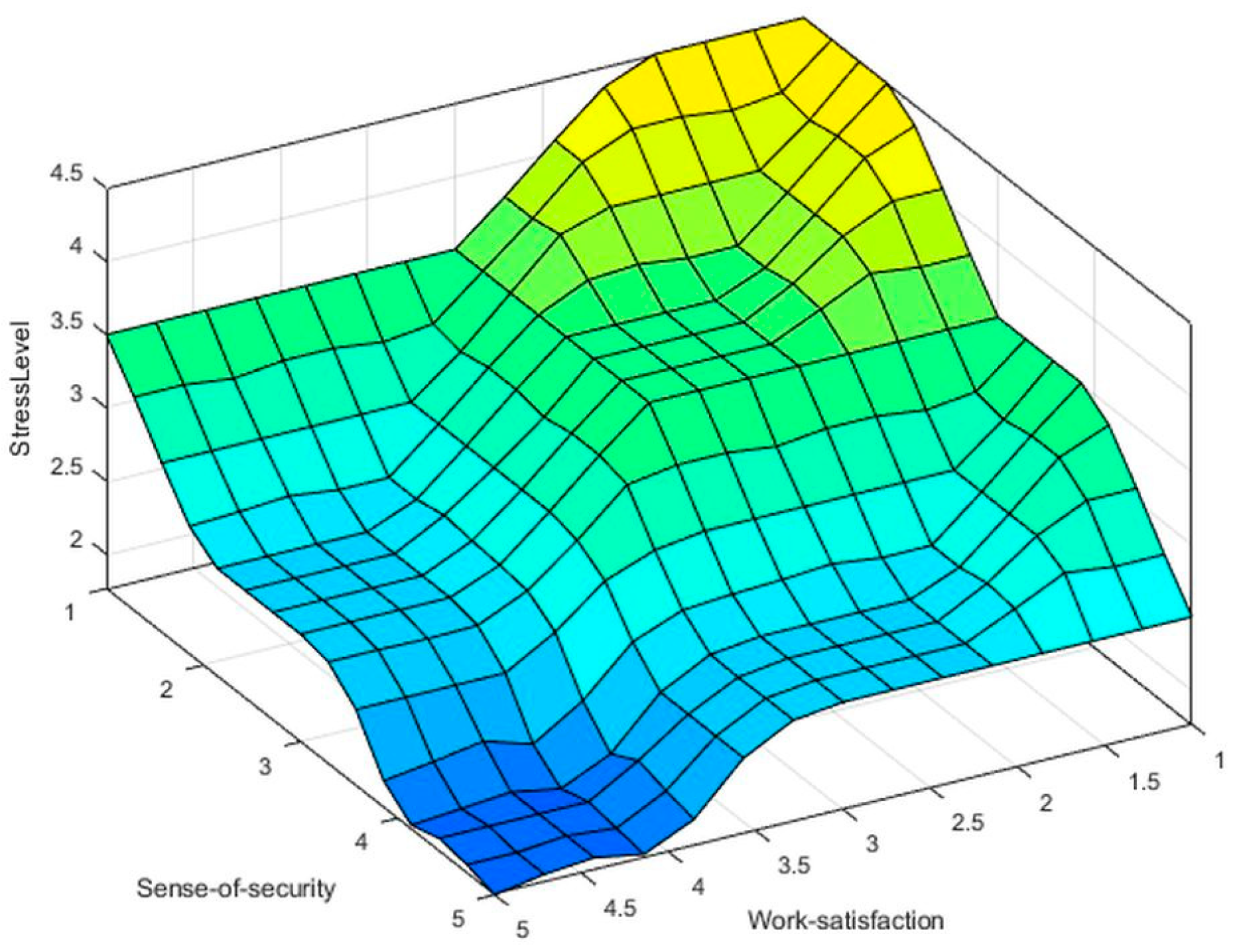

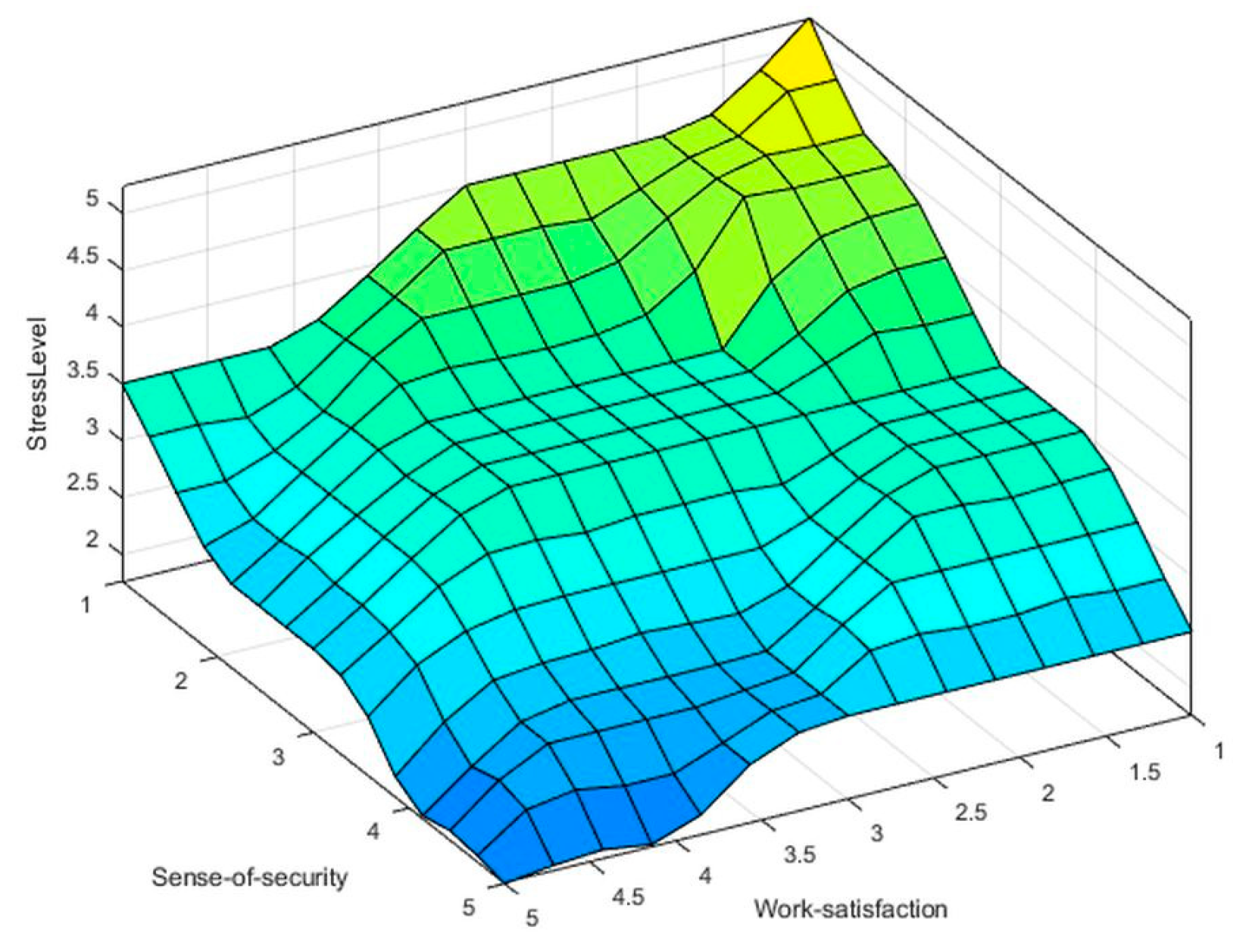

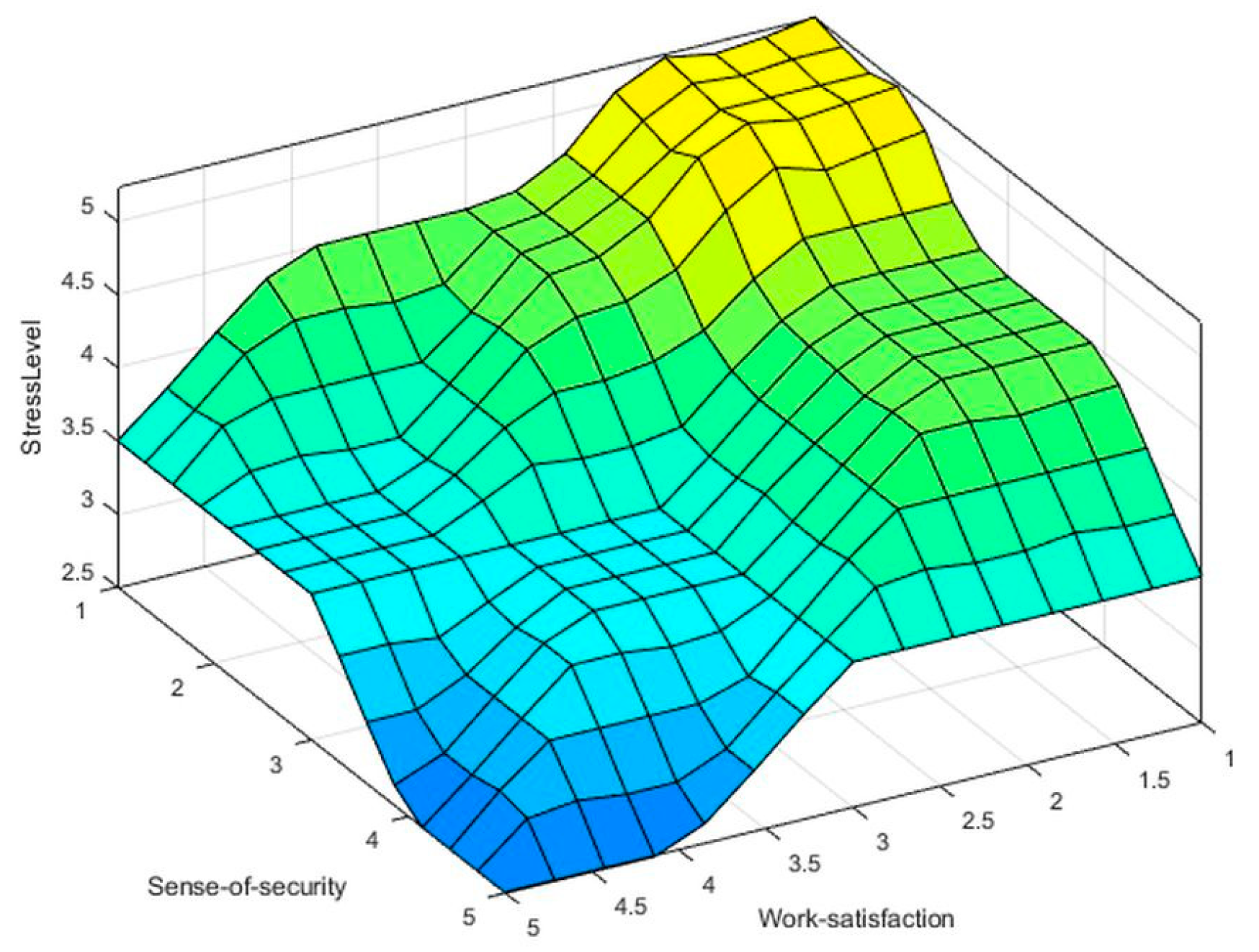

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the Stress Level as function of Work satisfaction and Sense of security for different values of HR. In

Figure 5 HR is considered Normal, in

Figure 6 HR is NormalHigh and in

Figure 7 HR is High. There are presented these three surfaces to validate the fuzzy rules with the tables from

Figure 4.

As can be seen in the surfaces in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the Stress Level is evaluated as No Stress only in case of HR being Normal or Normal High. In the case of High HR the Stress Level lowest value is Low Stress. Also, the Stress Level is evaluated as Extreme Stress only in case of HR being Normal High or High. In the case of Normal HR the Stress Level highest value is High Stress.

The figures provided illustrate the dynamic interplay between Heart Rate (HR) conditions—Normal, NormalHigh, and High—and the stress levels as influenced by variations in Work Satisfaction (WS) and Sense of Security (SoS). These 3D surface plots distinctly visualize how stress levels adjust in response to changes in these two key workplace variables under different physiological states.

Figure 5 (HR = Normal) showcases the lowest stress levels among the three scenarios. Here, stress levels generally hover around 'No Stress' to 'Medium Stress' across various combinations of WS and SoS. The graph reveals a significant dip in stress levels, particularly where both WS and SoS are high. This suggests that under normal HR conditions, favorable workplace environments characterized by high job satisfaction and security significantly mitigate stress.

Figure 6 (HR = NormalHigh) represents a moderate HR condition and shows a noticeable shift in stress levels towards 'Medium Stress' and 'High Stress' across similar ranges of WS and SoS. The peak areas (indicating higher stress levels) expand, especially in regions where WS or SoS are lower. This implies that even slightly elevated HR conditions can exacerbate stress responses in less ideal work settings, highlighting the sensitivity of stress levels to physiological changes amplified by suboptimal workplace conditions.

Figure 7 (HR = High) marks the most pronounced stress responses, with no areas falling into the 'No Stress' category and an extensive spread into 'High Stress' and 'Extreme Stress' zones. In this scenario, even high levels of WS and SoS are unable to counteract the influence of a high HR condition, which significantly elevates stress levels. This suggests that when HR is high, perhaps indicative of acute physiological stress or exertion, the protective effects of job satisfaction and security are markedly reduced.

The progression across these figures clearly illustrates how physiological states (as indicated by HR) interact with perceived job-related factors to shape an individual's stress landscape. These results corroborate the fuzzy logic rules applied in

Figure 4, validating the model's utility in predicting stress levels under varying conditions of HR, WS, and SoS. It's evident that both work environment factors and physiological states play crucial roles in determining overall stress levels, with significant implications for workplace health management and individual well-being strategies.

The fuzzy system is useful for evaluating at a given moment the state of stress, which is a “quantity” that cannot be measured, based on the measurable inputs HR by using sensors, Work satisfaction and Sense of security by using questionnaires. The surfaces are suggestive visual forms of highlighting the evolution of the stress level according to the values measured for the 3 inputs.

For the fuzzy system to be useful in preventing the occurrence of chronic stress that leads to burnout, the state of stress is monitored over time and chronic stress can be diagnosed based on the levels detected and the sequences that appear.

Following the study carried out to identify the link between HR and stress, it was concluded that a high HR is a sign of high stress, but it can also be of a great joy moment. In the developed fuzzy system, we included in the fuzzy rules the discrimination between the state of joy and the state of stress by evaluating the inputs Work satisfaction and Sense of security. It can be seen in the three surfaces in

Figure 5–7 that if Work satisfaction and Sense of security are High or Medium High, even if HR increases to High, the Stress Level does not exceed Medium Stress.

An interesting way to continue the research is the application of the research steps on a community of high school principals from Romania, by making the identification of the elements of the organizational climate with an impact on the state of stress, and the refinement of the fuzzy rules considering the new inputs related to the dimensions of the climate. An important step in reproducing the research is the correct identification of the climate assessment questionnaires. All the other steps are like those in the present research.

To successfully replicate this research, it is imperative to meticulously identify the organizational climate dimensions that significantly influence stress levels, which will serve as crucial inputs for the fuzzy system. Understanding and selecting these key factors are mandatory to determine which aspects of the work environment most directly affect psychological well-being. For instance, factors such as Work Satisfaction (WS) and Sense of Security (SoS) have been determined in our study as having profound impact on stress levels among educational leaders, but for other groups other factors could have greater impact.

Once these dimensions are identified, they need to be precisely quantified and incorporated into the fuzzy logic model. This involves setting up parameters and linguistic variables that accurately capture the nuances of these factors. For instance, WS and SoS can be measured on a scale and then translated into fuzzy terms like low, medium, and high. This translation is crucial as it allows the fuzzy system to process the data in a manner that reflects the complexity and ambiguity inherent in human emotional responses.

Moreover, to enhance the fidelity of the research replication, the method of collecting data on these climate dimensions must be standardized. This must involve using validated questionnaires or established scales that are consistent across different studies and settings. Ensuring consistency in data collection methods helps in accurately comparing results across different scenarios and enhances the reliability of the fuzzy model outputs.

Additionally, it is beneficial to continuously update the fuzzy rule set based on new findings and feedback from ongoing research. This iterative process helps refine the model's accuracy and adaptability, ensuring that it remains sensitive to the evolving dynamics of workplace environments. Thus, by systematically identifying and integrating critical climate dimensions into the fuzzy logic framework, researchers can effectively reproduce and extend the study, potentially leading to more targeted interventions that reduce stress and improve overall organizational health in educational settings.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically explored the interrelationship between physiological states, represented by Heart Rate (HR), and workplace variables—Work Satisfaction (WS) and Sense of Security (SoS)—to assess their combined effect on stress levels among school principals from southern Israel Bedouin area. Employing fuzzy logic to model stress responses, our findings elucidate how varying HR conditions can significantly amplify or mitigate the impact of workplace environment factors on stress levels. Under normal HR conditions, high levels of WS and SoS effectively reduce stress, suggesting that a supportive organizational climate is crucial in maintaining low stress levels. As HR increases to NormalHigh and High, the protective effects of positive work conditions diminish, indicating that physiological arousal associated with increased heart rates may predispose individuals to higher stress regardless of job satisfaction or security perceptions.

The progression from Normal to High HR conditions demonstrates a clear escalation in stress levels, with the most pronounced stress responses observed when HR is high. These outcomes highlight the critical interplay between an individual's physiological state and their work environment, underscoring the need for integrated approaches in managing workplace stress that consider both health status and organizational factors.

Our study, however, is not without limitations. One significant constraint is the exclusion of HR changes due to physical effort, as our research focused on school principals, a group typically engaged in work that involves minimal physical exertion. Consequently, the stress level assessments might differ under conditions where physical activity is a regular component of the job. Additionally, the results are inherently specific to the group studied, derived from organizational climate dimensions tailored to the specific context of school principals. These dimensions were extracted from specialized questionnaires, indicating that similar studies aimed at different professional groups would require a reevaluation and customization of the organizational climate assessment tools to ensure relevance and accuracy.

Moving forward, it is essential to extend this research framework to diverse occupational groups, including those involving varying degrees of physical activity, to broaden the applicability and generalizability of our findings. Further studies could also integrate real-time monitoring of physiological indicators alongside dynamic assessments of workplace environments to develop more nuanced understandings of stress triggers. Such comprehensive approaches will enhance the predictive power of stress models and inform more effective stress management strategies, ultimately contributing to healthier workplace environments across various sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I., M.L. and R.S.; methodology, A.I.; software, M.L. and R.S.; validation, Y.N., S.C. and A.D.; formal analysis, A.D.; investigation, Y.N.; resources, A.I. and M.L.; data curation, Y.N. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, A.D.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, A.I.; project administration, M.L.; funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, G.; Sharma, G. Burnout: A Risk Factor Amongst Mental Health Professionals During COVID-19. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launer, J. Burnout in the Age of COVID-19. Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 96, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsimani, P.; Montgomery, A.; Georganta, K. The Relationship Between Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in Nursing: A Theoretical Review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 41, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Goldberg, J. Prevention of Burnout: New Perspectives. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 1998, 7, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding Burnout - New Models. In The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Health Europa. Detecting Burnout Through Sweat with a Wearable Sensor. Available online: https://www.healtheuropa.com/detecting-burnout-through-sweat-with-a-wearable-sensor/105742/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Penn State College of Medicine. Researchers to Use Wearable Device to Measure Resident Wellness, Prevent Burnout. Available online: https://www.newswise.com/articles/researchers-to-use-wearable-device-to-measure-resident-wellness-prevent-burnout (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Riurean, S.; Leba, M.; Ionica, A.; Nassar, Y. Technical Solution for Burnout, the Modern Age Health Issue. In Proceedings of the Conference; Palermo, Italy, 2020; pp. 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Barbounaki, S.; Vivilaki, V.G. A Fuzzy Intelligent System to Assess Midwives’ Burnout Conditions. Eur. J. Midwifer 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Cucchi, A. Technostress Creators, Personality Traits, and Job Burnout: A Fuzzy-Set Configurational Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammady, P.; Mirzaei, R.; Sadeghi, J. The Effects of Demographic Factors on Job Burnout in Governmental Service Organizations; An Application of Neural-Fuzzy Analysis in Recognition of Behavioral Models, 2013, s.n.

- Sancholi, A.; Salarzehi, H.; Yaqubi, M. Identifying and Prioritising Job Burnout Factors Using an Integrated Fuzzy DEMATEL and Fuzzy ANP: An Empirical Study in Paramedical Society. Int. J. Bus. Excellence 2017, 12, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopowicz, P.; Mikołajewski, D. Fuzzy Approach to Computational Classification of Burnout—Preliminary Findings. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah MK, Gandrakota N, Cimiotti JP, Ghose N, Moore M, Ali MK. Prevalence of and Factors Associated With Nurse Burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036469.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Nedelec, L.; Carlasare, L.E.; Shanafelt, T.D. Resilience and Burnout Among Physicians and the General US Working Population. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e209385.

- Amanullah, S.; Shankar, R.R. The Impact of COVID-19 on Physician Burnout Globally: A Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 421, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T. Factors Contributing to Teacher Burnout During COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, Y., Ionica, A.C., Leba, M., Riurean, S., Rocha, Á. Research Regarding the Burnout State Evaluation: The Case of Principals from Arab Schools from South Israel. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Montenegro, 2020.

- Bezliudnyi, O.; Kravchenko, O.; Maksymchuk, B.; Mishchenko, M.; Maksymchuk, I. Psycho-correction of Burnout Syndrome in Sports Educators. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2019, 19, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. Burned-Out. Hum. Relat. 1976, pp. 16–20.

- N. Raman, M. Cao, Y. Tsvetkov, C. Kästner and B. Vasilescu, "Stress and Burnout in Open Source: Toward Finding, Understanding, and Mitigating Unhealthy Interactions," 2020 IEEE/ACM 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: New Ideas and Emerging Results (ICSE-NIER), Seoul, Korea (South), 2020, pp. 57-60.

- Mäntylä, M., Adams, B., Destefanis, G., Graziotin, D., Ortu, M. Mining Valence, Arousal, and Dominance – Possibilities for Detecting Burnout and Productivity?. IEEE Software: Special Issue on Sentiment and Emotion in Software Engineering, 2019, s.n.

- Mellblom, E.; Arason, I.; Gren, L.; Torkar, R. The Connection Between Burnout and Personality Types in Software Developers. IEEE Software: Special Issue on Sentiment and Emotion in Software Engineering, 2019.

- Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, Rosales RC, Guille C, Sen S, Mata DA. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2018 Sep 18;320(11):1131-1150.

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician Burnout: Contributors, Consequences and Solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmann, M.; Scheepers, R.; Nieboer, A.; Hilverda, F. Study-Related Wellbeing, Behavior, and Attitudes of University Students in the Netherlands During Emergency Remote Teaching in the Context of COVID-19: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1056983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A.K. Parental Burnout and Child Maltreatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Fam. Violence, n.d.

- Yin, Y.; Toom, A.; Parpala, A. International Students’ Study-Related Burnout: Associations with Perceptions of the Teaching-Learning Environment and Approaches to Learning. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, L.; Pyhältö, K.; Bujacz, A.; Nieminen, J. Study Engagement and Burnout of the PhD Candidates in Medicine: A Person-Centered Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 727746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, D. Burnout Among Public Primary School Teachers in Dire Dawa Administrative Region, Ethiopia. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 994313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masluk B, Gascón-Santos S, Oliván-Blázquez B, Bartolomé-Moreno C, Albesa A, Alda M, Magallón-Botaya R. The role of aggression and maladjustment in the teacher-student relationship on burnout in secondary school teachers. Front Psychol. 2022 Nov 24;13:1059899.

- Figueiredo-Ferraz, H.; Gil-Monte, P.; Grau-Alberola, E.; Libeiro do Couto, B. The Mediator Role of Feelings of Guilt in the Process of Burnout and Psychosomatic Disorders: A Cross-Cultural Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 751211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Yamamura, S. The Relationship Between Long Working Hours and Stress Responses in Junior High School Teachers: A Nationwide Survey in Japan. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 775522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gamble, J. Teacher Burnout and Turnover Intention in Higher Education: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and the Moderating Role of Proactive Personality. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1076277. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, A.; Kalinowski, E.; Hoferichter, C.; Vock, M. K−12 Teachers' Stress and Burnout During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 920326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadyaya, K.; Toyama, H.; Salmela-Aro, K. School Principals’ Stress Profiles During COVID-19, Demands, and Resources. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 731929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMatthews, D. E., Carrola, P. A., Reyes, P., & Knight, D. S. (2021). Principal burnout and job-related stress: A national study. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(2), 209-240. [CrossRef]

- Better Leaders Better Schools. The impact of principal turnover on school performance. Journal of Educational Leadership, 2023, 45, 123–145. [CrossRef]

- Edutopia. (2022). Supporting school leaders: Strategies to reduce burnout. Educational Leadership Review, 34(1), 67-82. [CrossRef]

- Nassar, Y.; Ionica, A. Burnout – evaluation from the relational perspective with the organizational climate through an innovative solution, Universitas, Petrosani. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, I. Multipathways to Burnout: Cognitive and Emotional Scenarios in Teacher Burnout. Anxiety, Stress Coping 1996, 9, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolman, L.; Deal, T. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership, 7th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arar, O.; Bar-Am, R. Impact of a Principal’s Leadership Style on School Organizational Climate in an Arab School in Israel. Chinese Bus. Rev. 2016, 15, 538–546. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).