Submitted:

24 July 2024

Posted:

26 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

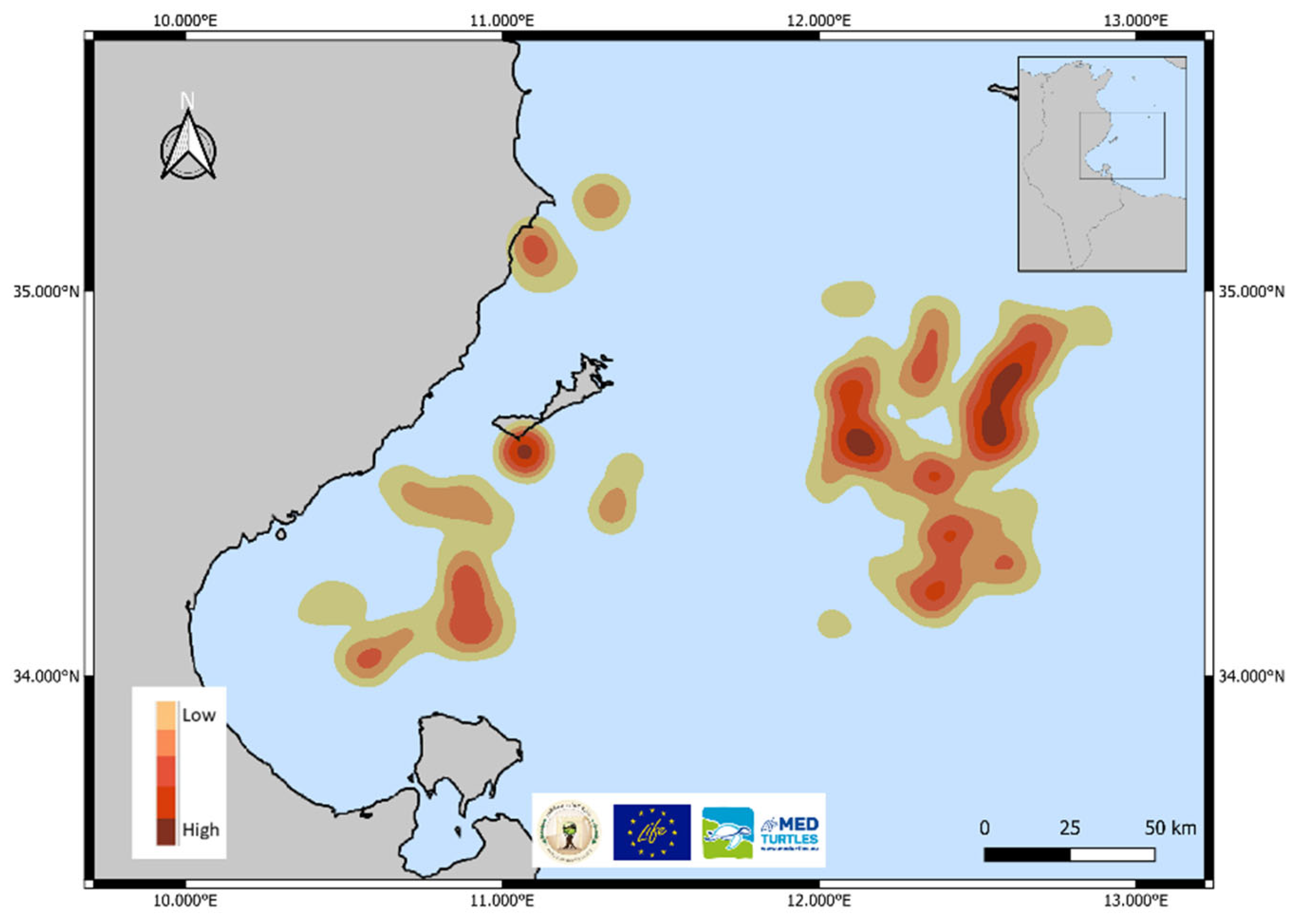

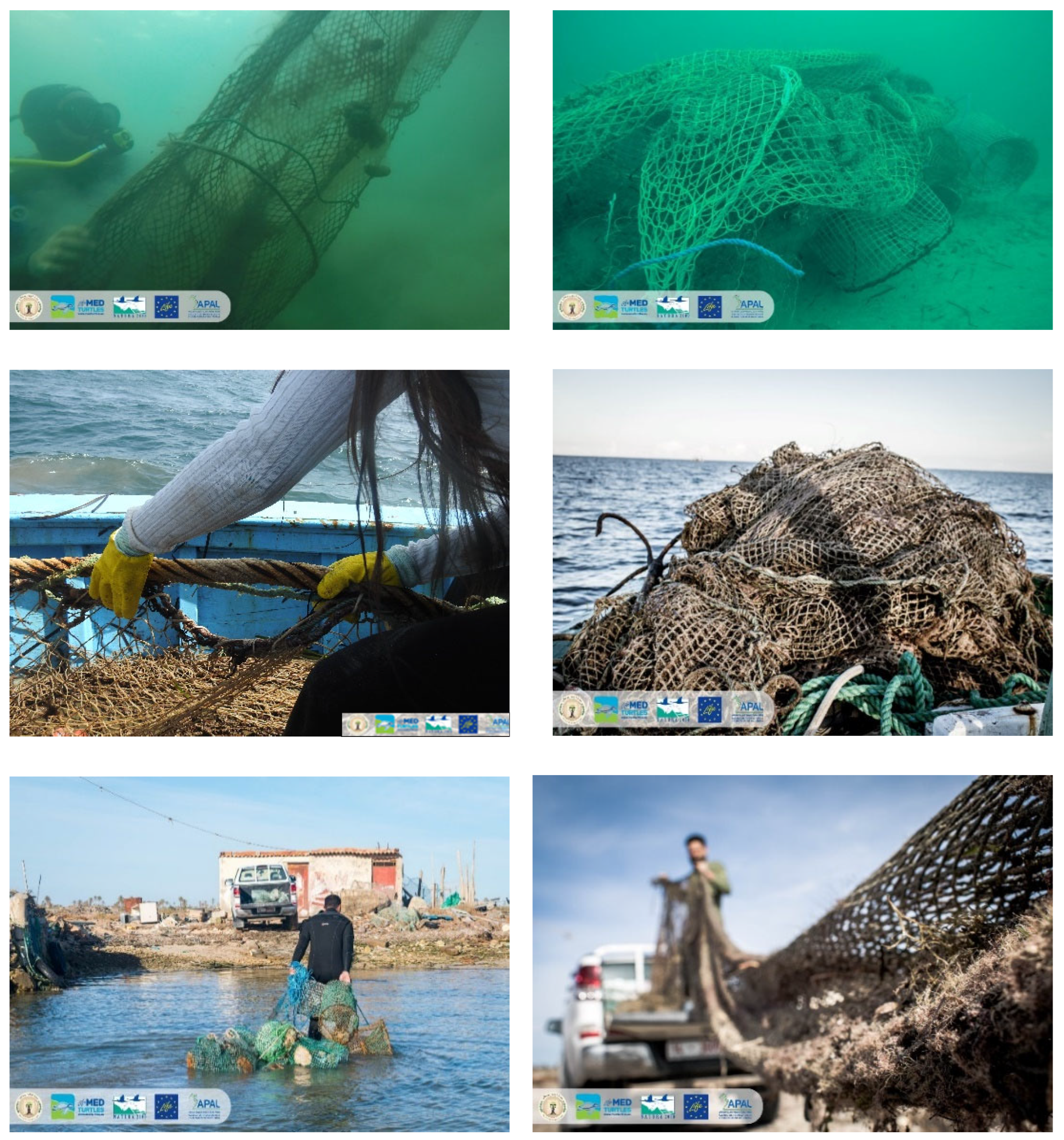

1. Ghost Gear in the Gulf of Gabès: The call for a social standard

2. Towards a code of conduct for ghost gear management in Tunisia

2.1. Key principles and objectives

2.2. Be aware of regulations

2.3. General principles of a code of conduct for the management of ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès (Tunisia)

- 1.1.

- This Code of Conduct aims to establish guidelines for responsible fishing practices, gear management, and collaborative efforts to mitigate the impact of ghost gear in Tunisia. It applies to all stakeholders, including fishermen, gear manufacturers, NGOs, and government agencies.

- 1.2.

- This code was developed as part of the Life MedTurtles project. The first paper on this topic in the framework of the project [3] provides essential insights into the impact of ghost gear in the Gulf of Gabès and a call for fisheries management, conservation and sustainable practices in the area. However, certain parts of it are based on relevant rules of international law, including those reflected in Towards G7 Action to Combat Ghost Fishing Gear. The Code also contains provisions that may be or have already been given binding effect by means of other obligatory legal instruments, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Environment Directorate (ENV) and the OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate (TAD), in consultation with the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

- 1.3.

- The Code is locally tailored the Gulf of Gabès area of Tunisia, aimed at conserving the marine Mediterranean biodiversity by reducing the number of incidental entanglement and death of sea turtles, cetaceans, sharks and other megafauna found in this area.

- 2.1.

- Establish principles, in accordance with the relevant international guidelines, to promote sustainable and environmentally-friendly fishing practices to minimize gear loss and its impact on marine species, particularly in the Gulf of Gabès, taking into account all its relevant biological, technological, economic, social, environmental and commercial aspects;

- 2.2.

- Serve as an instrument of reference to help national authorities to establish or to improve the legal and institutional framework required for the exercise of responsible fishing and in the formulation and implementation of appropriate measures encouraging accountability and responsible behavior among all stakeholders;

- 2.3.

- Foster cooperation among fishermen, manufacturers, NGOs, and regulatory bodies to address ghost gear issues;

- 2.4.

- Support the development and use of innovative technologies and practices for preventing and recovering lost gear.

- 2.5.

- Ensure open reporting and monitoring of ghost gear incidents and management activities.

- 3.1.

- In 2009 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) stated in a report that, globally, waste fishing gear comprised some 640,000 tonnes per annum, or 10% of the overall marine plastics problem (FAO, 2009).

- 3.2.

- A separate analysis was highlighted in a report published by UNEP that 70%, by weight, of floating macro plastic debris, in the open ocean, was fishing-related (UNEP, 2015).

- 3.3.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimated that 5-30% of global harvestable fish stocks are impacted by ghost gear every year, depending on the region, making ghost gear a significant threat to coastal economies and global food security.

- 3.4.

- Established in 2015 as program within World Animal Protection and later transitioning its affiliation to Ocean Conservancy in 2019, the GGGI is the world’s largest cross-sectoral alliance dedicated to address the global issue of ghost gear. As stated in its 2019 and 2023 Annual Report ghost gear is identified as the most harmful form of marine debris [17,38].

- 3.5.

- In November 2019, Greenpeace produced a report entitled “Ghost gear: the abandoned fishing nets haunting our oceans” [39]. The report stated that 12 million tons of plastic end up in the oceans every year, with abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear inadvertently killing a significant variety of marine wildlife.

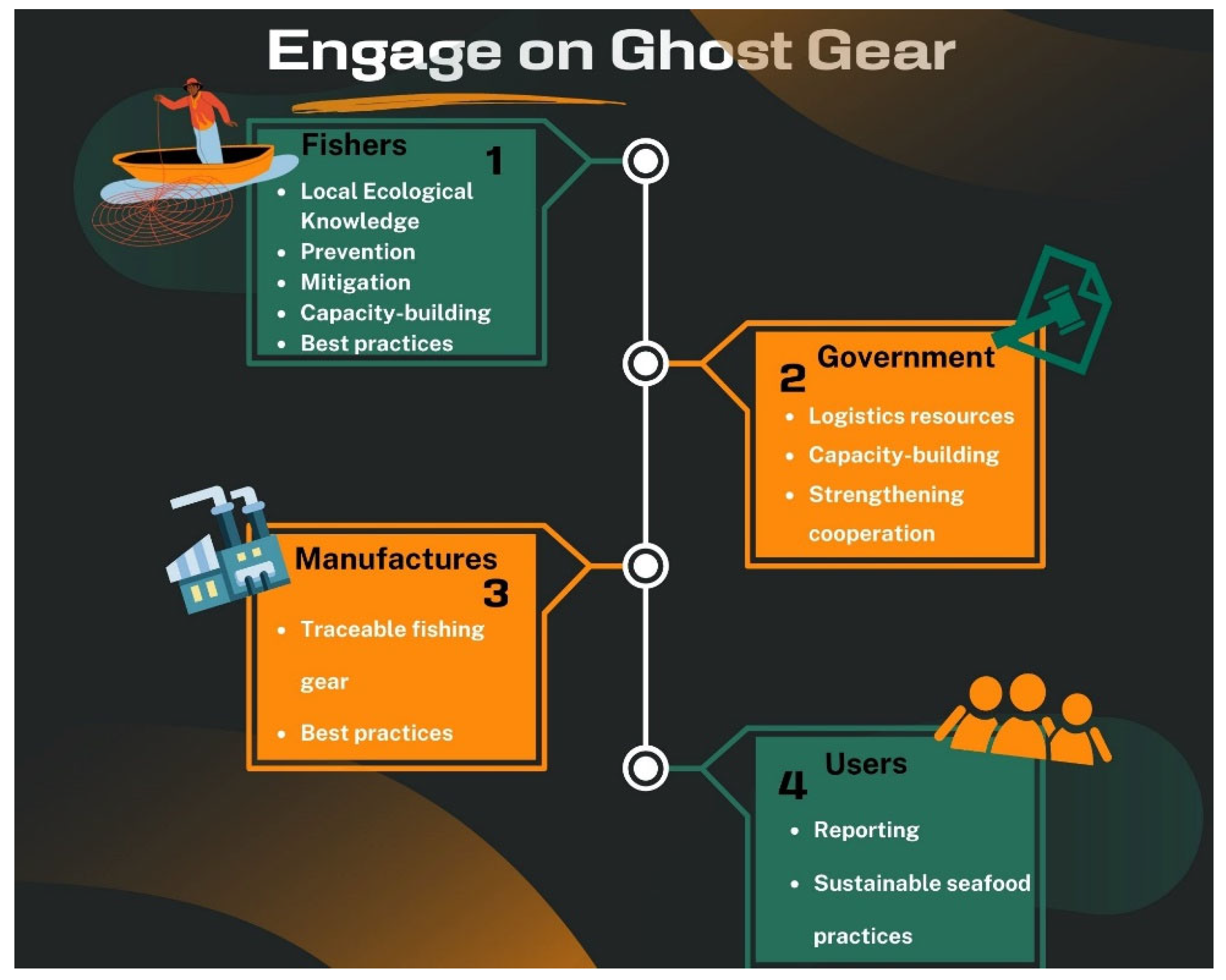

- 4.1.

- Fishers can collaborate in testing new fishing gear designs and technologies to minimize gear loss and improve sustainability. Three particular areas for gear improvement include: marking and tracking technologies, escape cords and panels and excluder devices (mechanisms that prevent entanglement). Escape cords and panels can help to stop ghost fishing from lost traps and pots in particular. Biodegradable materials and gear modifications to facilitate animals’ self-release after entanglement may reduce the impacts of gear loosed. Fishing operators should be marking fishing gear to prevent gear loss and assists in recovery if lost. A system for the marking of fishing gear is a key good practice to prevent and retrieve ghost fishing gear. Using surface markers, such as buoys, helps to locate the position of gear thus reduce losses and prevent conflict between different types of gears. Location trackers, such as satellite buoys, assist in finding and recovering gear when it is lost. Finally, marking gear to its owner(s), including underwater marking, helps to identify recovered ghost gear [30].

- 4.2.

- Reporting and retrieval policies help to address unavoidable gear loss. Immediate retrieval is the best solution to prevent all types of harm but requires training and on-board equipment. When immediate retrieval is not possible, due for example to adverse weather conditions that could threaten human safety, obligations to report lost gear might help in its relocation, avoidance of other vessels’ entanglement and later recovery.

- 4.3.

- Campaigns raising awareness of the consequences and of the magnitude of the issue of ghost gear such as pilot removals or workshops with fishers might therefore influence fishers’ behavior and increase their compliance with voluntary measures. Awareness campaigns can be run either through reports and media articles describing the problem and impacts of ghost gear or by showing stakeholders and particularly fishermen, the magnitude of the problem, with projects involving citizens into the collection and measurement of waste from the beach or underwater. This type of citizen-science programs has many benefits: they remove litter from the beach; they help build an extensive database of the problem of marine litter, and help increase citizens’ awareness of the problem.

- 4.4.

- Conduct national risk assessments to identify priority areas where there may be a higher amount of ghost fishing gear due to fishing practices or weather conditions, or impacts to particularly sensitive habitats, incorporating cost-benefit analysis in order to help focus interventions and identify information gaps.

- 4.5.

- Ensure the physical and policy context for environmentally sound waste management of fishing gear. This includes provision of sufficient port reception facilities to ease collection and transport of end-of-life gear, and policy measures to facilitate and encourage reuse and recycling. Set requirements or incentives (including conditioning fisheries support) for vessel owners to retrieve lost gear (and net scraps) and maintain on board space for retrieved gear. Regulations that limit gear removal to the gear owner can hinder well-intentioned removal efforts.

- 5.1.

- Enforcement of national regulations and compliance with international standards to prevent, reduce, and mitigate the impacts of abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) on marine ecosystems. The Tunisian government needs to implement fisheries management plans that include measures to reduce ALDFG, such as gear marking, reporting lost gear, and using more sustainable fishing practices.

- 5.2.

- The government, through its maritime and fisheries authorities, conducts regular surveillance and monitoring activities to ensure compliance with regulations related to fishing gear. There are legal penalties for fishers who do not comply with regulations regarding the proper use and disposal of fishing gear. The Polluter Pays Principle (PPP) is a fundamental concept in environmental policy. It ensures that those who cause pollution bear the costs associated with it, including the expenses related to prevention, control, and remediation. The PPP is essential for promoting sustainable practices and ensuring that environmental costs are borne by those responsible for pollution.

- 5.3.

- Government should foster partnerships with international organizations, such as the FAO, RFMOs, GGGI and UNEP, and participate in regional fisheries management organizations to align with global best practices. Tunisia participates in RFMOs, which play a significant role in the regional management of fisheries and the mitigation of ghost gear. In this context, the Tunisian State, in cooperation with the regional authorities, is invited to develop and implement training programs for personnel in techniques for reducing and mitigation fishing gear pollution, as well as training programs and simulation exercises. The Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) has set up a robust technical cooperation program to help countries build their capacity. As a first step, in 2024, the Faculty of Sciences of Sfax and the Tunisian Taxonomy Association ATUTAX have joined the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) in order to coordinate with international bodies in the fight against ghost fishing and to help implementing international legislation at national level in Tunisia.

- 5.4.

- Public awareness campaigns should be supported to educate fishers and communities about the importance of sustainable fishing practices and the dangers of ghost gear. Additionally, government should take various measures to encourage initiatives to preserve the cultural heritage of fishing communities include promoting traditional fishing practices such as charfia fishing in the Kerkennah Islands, drift nets (Jebbia), hand lines and long lines (Senhadja), traps and pots (gargoulettes), and beach seines (charfia nets). These programs often involve collaborations with cultural organizations and local communities. The government recognizes and sometimes provides awards or special statuses to communities and individuals who excel in using and preserving traditional fishing gear.

- 5.5.

- Supporting research programs that localize ghost gear and study their impacts on marine ecosystems is crucial to explore innovative solutions to mitigate these impacts. Encourage start up and industries to design special boats equipped with screen and mesh filters to collect floating wastes contaminating Tunisian coasts. Supporting interaction between industry and scientists to propose innovative waste reduction and biodegradable, recyclable, non-toxic materials. These should retain the catching effectiveness of traditional equipment and be both practical and cost effective.

- 6.1.

- Manufacturers can design fishing gear using durable materials that reduce the likelihood of gear loss and biodegradable materials that minimize environmental impact if lost. Developing eco-friendly and sustainable fishing gear options that align with environmental standards and regulations.

- 6.2.

- Invest in research and development (R&D) to explore innovative solutions for reducing the environmental impact of fishing gear and participate in pilot projects aimed at testing new materials and incorporating technologies such as RFID (Radio Frequency Identification, tags that uses radio waves to communicate between a tag and a reader), GPS trackers, and other smart technologies to monitor and retrieve lost gear.

- 6.3.

- Engage in awareness campaigns to educate fishers about the importance of preventing gear loss, benefits of using sustainable gear and share data insights on gear loss rates and causes with relevant authorities and stakeholders to help formulate effective policies

- 6.4.

- Implement programs to buy back old or damaged gear from fishers, encouraging the use of new, more sustainable gear and offer discounts or subsidies on eco-friendly gear to incentivize fishers to transition to more sustainable options.

- 6.5.

- Adopt and promote voluntary industry standards for sustainable gear design and production to ensure that all manufactured gear complies with national and international regulations regarding environmental impact and sustainability

- 6.6.

- Launch CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) initiatives focused on marine conservation, such as funding clean-up operations or supporting community-based projects aimed at reducing ghost gear and seek environmental certifications for products to demonstrate a commitment to sustainability and attract environmentally.

- 7.1.

- Start by raising awareness among fishers and other marine users about the impact of ghost gear on marine life and ecosystems. Implement also programs that incentivize fishers to retrieve lost gear. This can include offering rewards or discounts for returning ghost gear to designated collection points or participating in clean-up activities.

- 7.2.

- Divers can participate in the ghost gear management strategy along Tunisia's coastline by reporting ghost gear sightings so professionals can remove the ghost gear, contributing to better waste and fisheries management. Report ghost gear sightings while enjoying recreational diving allows professionals to remove the gear and helps develop improved waste management and fisheries management programs.

- 7.3.

- Encourage projects involving NGOs and citizens into the collection and measurement of gear waste from the beach or underwater. Mobile app, a web portal and a public database offers tools to collect and share comparable data on marine litter on beaches which help to build a harmonized database of marine litter and it increases citizens’ awareness of the issue. Ghost Gear Reporter is an app developed in partnership with the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI), which allows citizens to report details and locations of lost gear that might come across.

- 7.4.

- Share information, infographics, and success stories related to ghost gear on social media platforms such as (TunSea facebook group) to reach a wider audience.

- 7.5.

- Consumers can also make a difference by supporting sustainable seafood choices and advocating for responsible fishing practices. By opting for seafood products with certification from organizations or government, consumers actively support sustainable fishing practices. Consumers can influence the seafood industry by patronizing restaurants that prioritize sustainable seafood.

3. Recommendations and next steps

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Richardson, K.; Asmutis-Silvia, R.; Drinkwin, J.; Gilardi, K.V.; Giskes, I.; Jones, G.; Barco, S. Building evidence around ghost gear: Global trends and analysis for sustainable solutions at scale. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suka, R.; Huntington, B.; Morioka, J.; O'Brien, K.; Acoba, T. Successful application of a novel technique to quantify negative impacts of derelict fishing nets on Northwestern Hawaiian Island reefs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaouar, H.; Boussellaa, W.; Jribi, I. Ghost Gears in the Gulf of Gabès: Alarming Situation and Sustainable Solution Perspectives. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.; Wilcox, C. Global estimates of fishing gear lost to the ocean each year. Sci Adv. 2022, 8, eabq0135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Ghost Gear Initiative. GGGI 2022 Annual Report; pp. 1–31. Available online: https://www.ghostgear.org/annual-report-2022 (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Van der Hoop, J.; Moore, M.; Fahlman, A.; Bocconcelli, A.; Gearge, C. Behavioral Impact of Disentanglement of a Right Whale under Sedation and the Energetic Costs of Entanglement. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2013, 30, 282–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orós, J.; Montesdeoca, N.; Camacho, M.; Arencibia, A.; Calabuig, P. Causes of Stranding and Mortality, and Final Disposition of Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta) Admitted to a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Gran Canaria Island, Spain (1998-2014): A Long-Term Retrospective Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfadyen, G.; Huntington, T.; Cappell, R. Abandoned, Lost or Otherwise Discarded Fishing Gear; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2009; No. 523. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, C.; Mallos, N.J.; Leonard, G.H.; Rodriguez, A.; Hardesty, B.D. Using Expert Elicitation to Estimate the Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Marine Wildlife. Mar. Policy 2016, 65, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M.; Hudgins, J.; Sweet, M.A. Review of Ghost Gear Entanglement amongst Marine Mammals, Reptiles and Elasmobranchs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiros, J.P.; Raykov, V.S. Lethal lesions and amputation caused by plastic debris and fishing gear on theloggerhead turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758). Three case reports from Terceira Island, Azores (NEAtlantic). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 86, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, E.M.; Botterell, Z.L.R.; Broderick, A.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Lindeque, P.K.; Nuno, A.; Godley, B.J. A Global Review of Marine Turtle Entanglement in Anthropogenic Debris: A Baseline for Further Action. Endang. Species Res. 2017, 34, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, K.; Galloway, T.; Godley, B. Global Review of Shark and Ray Entanglement in Anthropogenic Marine Debris. Endanger. Species Res. 2019, 39, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Protecting Whales & Dolphins Initiative. Using Acoustic Sonar Technology to Locate and Tackle Ghost Gear. Available online: https://wwfwhales.org/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Widjaja, S.L.; Tony, W.; Hassan, V.A.; Hennie, B.; Per, E. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Drivers. Available online: https://www.oceanpanel.org/bluepapers/illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing-and-associated-drivers (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- FAO. Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries; FAO: Rome, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- GGGI. Global Ghost Gear Initiative Annual Report; Global Ghost Gear Initiative, 2019; pp. 1–29.

- WWF, 2020. Ghost gear is the deadliest form of marine plastic debris. Stop Ghost Gear: The Most Deadly Form of Marine Plastic Debris | Publications | WWF (worldwildlife.org).

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines on the Marking of Fishing Gear. Directives Volontaires sur le Marquage des Engins de Pêche. Directrices Voluntarias sobre el Marcado de las Artes de Pesca; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; pp. 1–88, Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Jribi, I.; Bradai, M.N.; Bouain, A. Loggerhead Turtle Nesting Activity in Kuriat Islands (Tunisia): Assessment of Nine Years Monitoring. Mar. Turtle Newsl. 2006, 112, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bradai, M.N.; Saidi, B.; Enajjar, S. Overview on Mediterranean Shark’s Fisheries: Impact on the Biodiversity. In Marine Ecology: Biotic and Abiotic Interactions; Türkoğlu, M., Önal, U., Ismen, A., Eds.; INTEC: London, UK, 2018; pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, B.; Enajjar, S.; Karaa, S.; Echwikhi, K.; Jribi, I.; Bradai, M.N. Shark Pelagic Longline Fishery in the Gulf of Gabes: Inter-Decadal Inspection Reveals Management Needs. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2019, 20, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradai, M.N.; Saidi, B.; Bouaïn, A.; Guelorget, O.; Capapé, C. The Gulf of Gabès (Southern Tunisia, Central Mediterranean): A Nursery Area for Sandbar Shark, Carcharhinus plumbeus (Nardo, 1827) (Chondrichthyes: Carcharhinidae). Ann. Ser. Historia Naturalis 2005, 15, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Enajjar, S.; Saidi, B.; Bradai, M.N. Elasmobranchs in Tunisia: Status, Ecology, and Biology. In Sharks Past, Present and Future; Bradai, M.N., Saidi, B., Enajjar, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, 2022; pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Louhichi, M.; Girard, A.; Jribi, I. Fishermen Interviews: A Cost-Effective Tool for Evaluating the Impact of Fisheries on Vulnerable Sea Turtles in Tunisia and Identifying Levers of Mitigation. Animals 2023, 13, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anonyme. Annuaire des Statistiques des Pêches et de l’Aquaculture en Tunisie (Année 2020); Direction Générale de la Pêche et de l’Aquaculture: Tunisia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IMO. IMO Action Plan on Reducing Marine Litter from Ships. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/20marinelitteractionmecp73.aspx#:~:text=The%20action%20plan%20supports%20IMOsentangled%20in%20propellers%20and%20rudders (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- OECD. Towards G7 Action to Combat Ghost Fishing Gear. Policy Perspectives, OECD Environment Policy Paper 2021, 25.

- NOAA. Marine Debris Program. Accomplishments Report; Office of Response: USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GGGI. Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear: June 2021 Update; Global Ghost Gear Initiative: Canada, 2021; Available online: https://www.ghostgear.org (accessed on 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution 76/71. Sustainable Fisheries, Including through the 1995 Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, and Related Instruments; United Nations: New York, NY, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Marine Stewardship Council (MSC). Preventing Lost and Abandoned Fishing Gear (Ghost Fishing). Available online: https://www.msc.org/what-we-are-doing/preventing-lost-gear-and-ghost-fishing (accessed on 2022).

- Drinkwin, J. Report. Retrieving Lost Fishing Gear: Recommendations for Developing an Effective Program; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.J.; Brillant, S.; Walker, T.R.; Bailey, M.; Callaghan, C. A Ghostly Issue: Managing Abandoned, Lost and Discarded Lobster Fishing Gear in the Bay of Fundy in Eastern Canada. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 181, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczenski, B.; Vargas Poulsen, C.; Gilman, E.L.; Musyl, M.; Geyer, R.; Wilson, J. Plastic Gear Loss Estimates from Remote Observation of Industrial Fishing Activity. Fish. Fish. 2022, 23, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Plastic Debris in the Ocean. In UNEP Year Book 2014: Emerging Issues Update; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- GGGI. Global Ghost Gear Initiative Annual Report; Global Ghost Gear Initiative, 2023; pp. 1–37.

- Greenpeace, 2019. Annual Report for Stichting Greenpeace Council, 31 pp.

| Legal instrument | Relevance to ghost gear |

| International Instruments | |

| FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries | This code provides principles and standards for responsible fishing practices, including measures to prevent the loss of fishing gear and to mitigate the impacts of ghost gear. |

| MARPOL Annex V | The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) includes provisions in Annex V that regulate the discharge of garbage from ships, including fishing gear. It prohibits the disposal of plastics, including synthetic fishing nets, into the sea. |

| The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) | UNCLOS sets out the legal framework for marine and maritime activities. It includes obligations for states to protect and preserve the marine environment, which can extend to measures addressing ghost gear. |

| The Global Ghost Gear Initiative(GGGI): | An international alliance that aims to address the problem of ghost gear on a global scale through collaboration, innovation, and advocacy. |

| Regional Instruments | |

| European Union Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) | This directive requires EU member states to achieve Good Environmental Status (GES) of their marine waters by 2020, which includes measures to address marine litter, including ghost gear. |

| The OSPAR Convention: | The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR) includes measures to reduce marine litter, including initiatives to prevent, retrieve, and manage ghost gear. |

| National Instruments | |

| U.S. Marine Debris Act: | This act provides a framework for identifying, assessing, reducing, and preventing marine debris, including ghost gear, in U.S. waters. |

| Canada's Oceans Act: | This act includes provisions for the protection and preservation of the marine environment, which can be used to address ghost gear. |

| Australia's National Plan of Action on Marine Litter | This plan includes measures to prevent and manage ghost gear as part of broader efforts to reduce marine litter. |

| Non-Governmental Initiatives | |

| World Animal Protection: | An organization that works globally to address the issue of ghost gear through projects, advocacy, and partnership with stakeholders. |

| The Ocean Cleanup: | A non-profit organization developing advanced technologies to rid the oceans of plastic, which includes efforts to tackle ghost gear. |

| Tunisian Instruments useful to combat ghost gear | |

| Law no. 95-73 of 24 July 1995 | This law defines the public maritime domain as all maritime areas under Tunisian jurisdiction, including the seabed, subsoil, and overlying waters, extending to the high seas within the boundaries established by international law. |

| Law no. 95-72 of 24 July 1995 | The law establishes the Coastal Protection and Management Agency (APAL) in Tunisia for the protection, preservation, and sustainable development of Tunisia's coastal zones. |

| Law no. 49-2009 of 20 July 2009 | The law concerns the National Environmental Protection Agency (ANPE) in Tunisia, updates and enhances the mandate and functions of the agency originally established in 1988. This law aims to strengthen the framework for environmental protection and sustainable development in Tunisia. |

| Law of 3 April 1996 | The law constitutes a national emergency response plan to combat marine pollution incidents. |

| Ban on single-use plastic bags | The ban, announced through a decree issued by the Ministry of Local Affairs and Environment, aims to reduce plastic waste and its harmful effects on the environment |

| Tunisia's post-2020 National Environmental Protection Strategy | Strategy developed to strengthen the legal and institutional framework for environmental protection in Tunisia. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).