Submitted:

24 July 2024

Posted:

26 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Prenatal Nutritional Deficiency

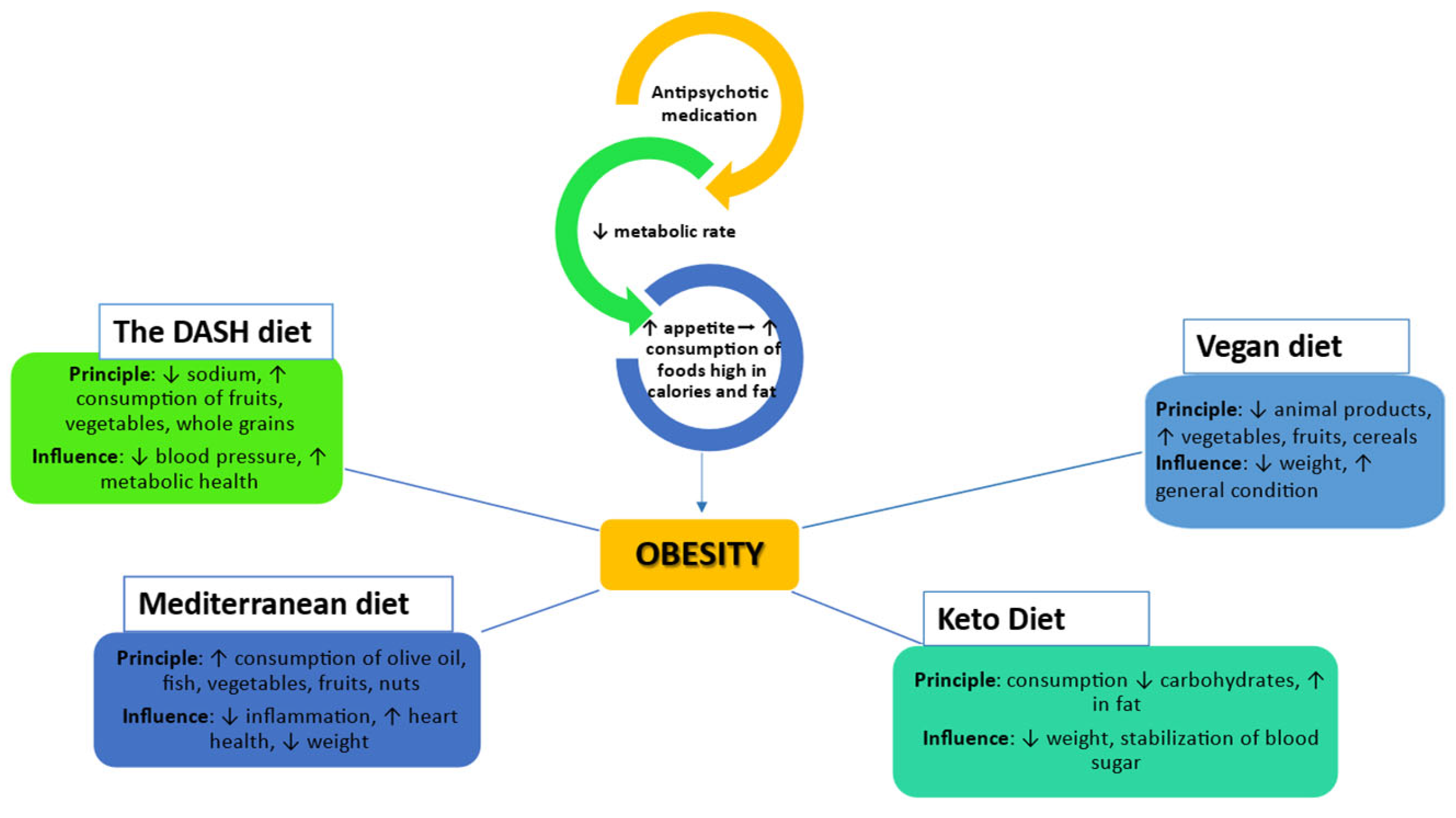

3. Obesity in schizophrenia: the role of diet and antidepressants

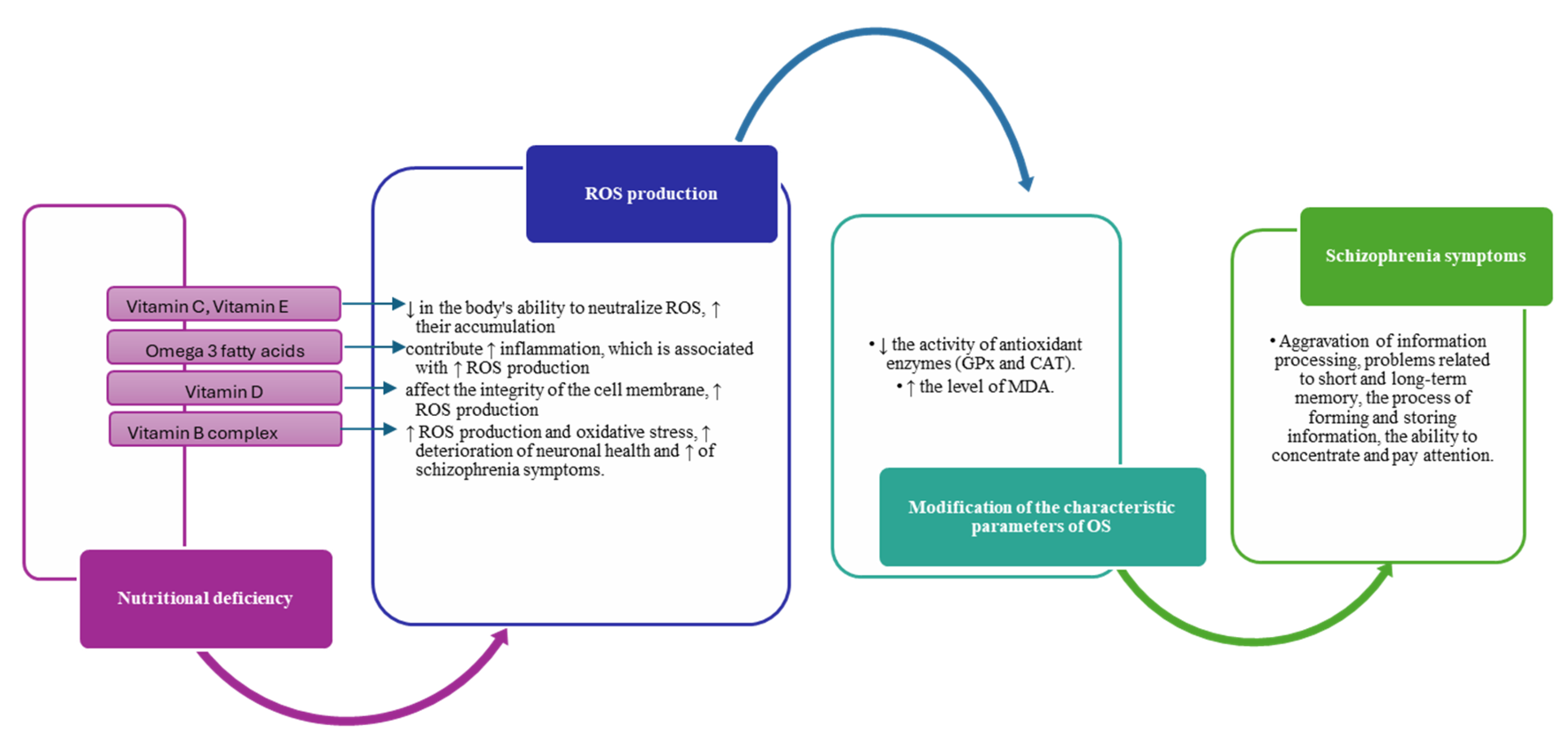

4. Impact of diet on oxidative stress and inflammation in schizophrenia

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jacka, F.N.; Mykletun, A.; Berk, M. Moving towards a Population Health Approach to the Primary Prevention of Common Mental Disorders. BMC Med. 2012, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaolapo, O.J.; Onaolapo, A.Y. Nutrition, Nutritional Deficiencies, and Schizophrenia: An Association Worthy of Constant Reassessment. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.Y.; Tee, S.F.; Su, K.P. Editorial: The Link between Nutrition and Schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Kirat, H.; Khattabi, A.; Khalis, M.; Belrhiti, Z. Effects of Physical Activity and Nutrient Supplementation on Symptoms and Well-Being of Schizophrenia Patients: An Umbrella Review. Schizophr. Res. 2023, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth, J.; Veronese, N.; Cotter, J.; Shivappa, N.; Hebert, J.R.; Ee, C.; Smith, L.; Stubbs, B.; Jackson, S.E.; Sarris, J. What Is the Role of Dietary Inflammation in Severe Mental Illness? A Review of Observational and Experimental Findings. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarris, J. Nutritional Psychiatry: From Concept to the Clinic. Drugs 2019, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.; Corfe, B. The Role of Diet and Nutrition on Mental Health and Wellbeing. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, B.; Shen, C.; Sahakian, B.J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, J.; Cheng, W. Associations of Dietary Patterns with Brain Health from Behavioral, Neuroimaging, Biochemical and Genetic Analyses. Nat. Ment. Heal. 2024, 2, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, M. Diet, Diabetes and Schizophrenia: Review and Hypothesis. In Proceedings of the British Journal of Psychiatry; 2004; Vol. 184.

- Elman, I.; Borsook, D.; Lukas, S.E. Food Intake and Reward Mechanisms in Patients with Schizophrenia: Implications for Metabolic Disturbances and Treatment with Second-Generation Antipsychotic Agents. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Georgieff, M.K. Advocacy for Improving Nutrition in the First 1000 Days to Support Childhood Development and Adult Health. Pediatrics 2018, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderami, A.; Zarghami, M.; Darvishi-Khezri, H. The Effects and Potential Mechanisms of Folic Acid on Cognitive Function: A Comprehensive Review. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maekawa, M.; Watanabe, A.; Iwayama, Y.; Kimura, T.; Hamazaki, K.; Balan, S.; Ohba, H.; Hisano, Y.; Nozaki, Y.; Ohnishi, T.; et al. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Deficiency during Neurodevelopment in Mice Models the Prodromal State of Schizophrenia through Epigenetic Changes in Nuclear Receptor Genes. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Chen, G.; Guo, C.; Wen, X.; Song, X.; Zheng, X. Long-Term Effect of Prenatal Exposure to Malnutrition on Risk of Schizophrenia in Adulthood: Evidence from the Chinese Famine of 1959–1961. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susser, E.; St Clair, D. Prenatal Famine and Adult Mental Illness: Interpreting Concordant and Discordant Results from the Dutch and Chinese Famines. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.; Brown, A.; St Clair, D. Prevention and Schizophrenia - The Role of Dietary Factors. Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Eyre, H.; Jacka, F.N.; Dodd, S.; Dean, O.; McEwen, S.; Debnath, M.; McGrath, J.; Maes, M.; Amminger, P.; et al. A Review of Vulnerability and Risks for Schizophrenia: Beyond the Two Hit Hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lally, J.; Gaughran, F. Vitamin D in Schizophrenia and Depression: A Clinical Review. BJPsych Adv. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenrock, S.A.; Tarantino, L.M. Developmental Vitamin D Deficiency and Schizophrenia: The Role of Animal Models. Genes, Brain Behav.

- Cha, H.Y.; Yang, S.J. Anti-Inflammatory Diets and Schizophrenia. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.S.; Whiting, S.J.; Barton, C.N. Vitamin D Intake: A Global Perspective of Current Status. In Proceedings of the Journal of Nutrition; 2005; Vol. 135.

- Wassif, G.A.; Alrehely, M.S.; Alharbi, D.M.; Aljohani, A.A. The Impact of Vitamin D on Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewison, M.; Bouillon, R.; Giovannucci, E.; Goltzman, D.; Meyer, M.; Welsh, J.E. Feldman and Pike’s Vitamin D: Volume Two: Disease and Therapeutics; 2023.

- Cui, X.; McGrath, J.J.; Burne, T.H.J.; Eyles, D.W. Vitamin D and Schizophrenia: 20 Years On. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Leeuw, C.; De Witte, L.D.; Stellinga, A.; Van Der Ley, C.; Bruggeman, R.; Kahn, R.S.; Van Os, J.; Marcelis, M. Vitamin D Concentration and Psychotic Disorder: Associations with Disease Status, Clinical Variables and Urbanicity. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häfner, H.; Nowotny, B. Epidemiology of Early-Onset Schizophrenia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1995, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.C.; Huang, Y.S.; Ouyang, W.C. Beneficial Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation in Schizophrenia: Possible Mechanisms. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Erp, T.G.M.; Hibar, D.P.; Rasmussen, J.M.; Glahn, D.C.; Pearlson, G.D.; Andreassen, O.A.; Agartz, I.; Westlye, L.T.; Haukvik, U.K.; Dale, A.M.; et al. Subcortical Brain Volume Abnormalities in 2028 Individuals with Schizophrenia and 2540 Healthy Controls via the ENIGMA Consortium. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, K.D.; Zsombok, A.; Eckel, R.H. Lipid Processing in the Brain: A Key Regulator of Systemic Metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocking, R.J.T.; Assies, J.; Ruhé, H.G.; Schene, A.H. Focus on Fatty Acids in the Neurometabolic Pathophysiology of Psychiatric Disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedelin, M.; Löf, M.; Olsson, M.; Lewander, T.; Nilsson, B.; Hultman, C.M.; Weiderpass, E. Dietary Intake of Fish, Omega-3, Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Vitamin D and the Prevalence of Psychotic-like Symptoms in a Cohort of 33 000 Women from the General Population. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, K.W. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Mental Health. Glob. Heal. J. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amminger, G.P.; Schäfer, M.R.; Schlögelhofer, M.; Klier, C.M.; McGorry, P.D. Longer-Term Outcome in the Prevention of Psychotic Disorders by the Vienna Omega-3 Study. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzatello, P.; De Rosa, M.L.; Rocca, P.; Bellino, S. Effects of Omega 3 Fatty Acids on Main Dimensions of Psychopathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourre, J.M.; Faivre, A.; Dumont, O.; Nouvelot, A.; Loudes, C.; Puymirat, J.; Tixier-Vidal, A. Effect of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Fetal Mouse Brain Cells in Culture in a Chemically Defined Medium. J. Neurochem. 1983, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourre, J.M.; Pascal, G.; Durand, G.; Masson, M.; Dumont, O.; Piciotti, M. Alterations in the Fatty Acid Composition of Rat Brain Cells (Neurons, Astrocytes, and Oligodendrocytes) and of Subcellular Fractions (Myelin and Synaptosomes) Induced by a Diet Devoid of N-3 Fatty Acids. J. Neurochem. 1984, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourre, J.-M. Acides Gras ω-3 et Troubles Psychiatriques. médecine/sciences 2005, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasbalg, T.L.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Ramsden, C.E.; Majchrzak, S.F.; Rawlings, R.R. Changes in Consumption of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids in the United States during the 20th Century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caffrey, A.; McNulty, H.; Irwin, R.E.; Walsh, C.P.; Pentieva, K. Maternal Folate Nutrition and Offspring Health: Evidence and Current Controversies. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Nutrition Society; 2019; Vol. 78.

- Cusick, S.E.; Georgieff, M.K. The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the “First 1000 Days. ” J. Pediatr. 2016, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryar-Williams, S.; Strobel, J.; Clements, P. Molecular Mechanisms Provide a Landscape for Biomarker Selection for Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Psychosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Miss, M. del R.; Pérez-Mutul, J.; López-Canul, B.; Solís-Rodríguez, F.; Puga-Machado, L.; Oxté-Cabrera, A.; Gurubel-Maldonado, J.; Arankowsky-Sandoval, G. Folate, Homocysteine, Interleukin-6, and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alfa Levels, but Not the Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase C677T Polymorphism, Are Risk Factors for Schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, N.; Ayedi, I.; Sidhom, O.; Kallel, A.; Rafrafi, R.; Jomaa, R.; Melki, W.; Feki, M.; Kaabechi, N.; El Hechmi, Z. Plasma Homocysteine in Schizophrenia: Determinants and Clinical Correlations in Tunisian Patients Free from Antipsychotics. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Sun, X.Y.; Zhang, C.B.; Yan, J.J.; Zhao, Q.Q.; Yang, S.Y.; Yan, L.L.; Huang, N. hua; Zeng, J.; Liao, J.Y.; et al. Association between B Vitamins and Schizophrenia: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, R.; Venketeswaramurthy, N.; Sambath Kumar, R. A Critical Review on Hypothesis, Pathophysiology of Schizophrenia, and Role of Vitamins in Its Management. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susser, E.; Neugebauer, R.; Hoek, H.W.; Brown, A.S.; Lin, S.; Labovitz, D.; Gorman, J.M. Schizophrenia after Prenatal Famine Further Evidence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1996, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffma, R.J.L.; Lamberti, S.; Achtyes, E.; Macklin, E.A.; Galendez, G.; Raeke, L.; Silverstein, N.J.; Tuinstra, D.; Hill, M.; Goff, D.C. A Multi-Center Investigation of Folate plus B12 Supplementation in Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C.J.; Crane, N.T.; Wilson, D.B.; Yetley, E.A. Estimated Folate Intakes: Data Updated to Reflect Food Fortification, Increased Bioavailability, and Dietary Supplement Use. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.O. B Vitamins and the Brain: Mechanisms, Dose and Efficacy—A Review. Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayabandara, M.; Hanwella, R.; Ratnatunga, S.; Seneviratne, S.; Suraweera, C.; de Silva, V.A. Antipsychotic-Associated Weight Gain: Management Strategies and Impact on Treatment Adherence. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Van Winkel, R.; Yu, W.; Correll, C.U. Metabolic and Cardiovascular Adverse Effects Associated with Antipsychotic Drugs. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R.I.G. The Management of Obesity in People with Severe Mental Illness: An Unresolved Conundrum. Psychother. Psychosom. 2019, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhacker, W.W.; Cetkovich-Bakmas, M.; De Hert, M.; Hennekens, C.H.; Lambert, M.; Leucht, S.; Maj, M.; McIntyre, R.S.; Naber, D.; Newcomer, J.W.; et al. Comorbid Somatic Illnesses in Patients with Severe Mental Disorders: Clinical, Policy, and Research Challenges. In Proceedings of the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry; 2008; Vol. 69.

- Maayan, L.; Correll, C.U. Management of Antipsychotic-Related Weight Gain. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, J.G. Induction of Obesity by Psychotropic Drugs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Dekker, J.M.; Wood, D.; Kahl, K.G.; Holt, R.I.G.; Möller, H.J. Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes in People with Severe Mental Illness Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), Supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Psychiatry 2009, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, D.B.; Mentore, J.L.; Heo, M.; Chandler, L.P.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Infante, M.C.; Weiden, P.J. Antipsychotic-Induced Weight Gain: A Comprehensive Research Synthesis. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.L.; Wang, T.N.; Lin, T.Y.; Shao, W.C.; Chang, S.H.; Chou, J.Y.; Ho, Y.F.; Liao, Y.T.; Chen, V.C.H. Differential Effects of Olanzapine and Clozapine on Plasma Levels of Adipocytokines and Total Ghrelin. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ader, M.; Kim, S.P.; Catalano, K.J.; Ionut, V.; Hucking, K.; Richey, J.M.; Kabir, M.; Bergman, R.N. Metabolic Dysregulation with Atypical Antipsychotics Occurs in the Absence of Underlying Disease: A Placebo-Controlled Study of Olanzapine and Risperidone in Dogs. Diabetes 2005, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverstone, T.; Smith, G.; Goodall, E. Prevalence of Obesity in Patients Receiving Depot Antipsychotics. Br. J. Psychiatry 1988, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yang, S.J.; Kim, H.H.; Jo, A.; Jhon, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Ryu, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kweon, Y.R.; Kim, S.W. Effects of Dietary Habits on General and Abdominal Obesity in Community-Dwelling Patients with Schizophrenia. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hägg, S.; Söderberg, S.; Ahrén, B.; Olsson, T.; Mjörndal, T. Leptin Concentrations Are Increased in Subjects Treated with Clozapine or Conventional Antipsychotics. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabeau, L.; Lavens, D.; Peelman, F.; Eyckerman, S.; Vandekerckhove, J.; Tavernier, J. The Ins and Outs of Leptin Receptor Activation. FEBS Lett. 2003, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohan, F.C.; Grasberger, J.C.; Lowell, F.M.; Johnston, H.T.; Arbegast, A.W. Relapsed Schizophrenics: More Rapid Improvement on a Milk- and Cereal-Free Diet. Br. J. Psychiatry 1969, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigalou, C.; Konstantinidis, T.; Paraschaki, A.; Stavropoulou, E.; Voidarou, C.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Mediterranean Diet as a Tool to Combat Inflammation and Chronic Diseases. An Overview. An Overview. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrosielski, D.A.; Papandreou, C.; Patil, S.P.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Diet and Exercise in the Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsman, S.L.; Vining, E.P.G.; Quaskey, S.A.; Mellits, D.; Freeman, J.M. Efficacy of the Ketogenic Diet for Intractable Seizure Disorders: Review of 58 Cases. Epilepsia 1992, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarnyai, Z.; Kraeuter, A.K.; Palmer, C.M. Ketogenic Diet for Schizophrenia: Clinical Implication. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; Hinderliter, A.; Watkins, L.L.; Craighead, L.; Lin, P.H.; Caccia, C.; Johnson, J.; Waugh, R.; Sherwood, A. Effects of the DASH Diet Alone and in Combination with Exercise and Weight Loss on Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Biomarkers in Men and Women with High Blood Pressure: The ENCORE Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wallin, A.; Wolk, A. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet and Incidence of Stroke. Stroke 2016, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.R.; Erlinger, T.P.; Young, D.R.; Jehn, M.; Charleston, J.; Rhodes, D.; Wasan, S.K.; Appel, L.J. Results of the Diet, Exercise, and Weight Loss Intervention Trial (DEW-IT). Hypertension 2002, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurusamy, J.; Gandhi, S.; Damodharan, D.; Ganesan, V.; Palaniappan, M. Exercise, Diet and Educational Interventions for Metabolic Syndrome in Persons with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2018, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostock, E.C.S.; Kirkby, K.C.; Taylor, B.V.M. The Current Status of the Ketogenic Diet in Psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntalkitsi, S.; Efthymiou, D.; Bozikas, V.; Vassilopoulou, E. Halting the Metabolic Complications of Antipsychotic Medication in Patients with a First Episode of Psychosis: How Far Can We Go with the Mediterranean Diet? A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraeuter, A.K.; Loxton, H.; Lima, B.C.; Rudd, D.; Sarnyai, Z. Ketogenic Diet Reverses Behavioral Abnormalities in an Acute NMDA Receptor Hypofunction Model of Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2015, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorić, T.; Mavar, M.; Rumbak, I. The Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet on Metabolic Syndrome in Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, S.B.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Watkins, A.; Curtis, J.; Kalucy, M.; Samaras, K. A Nutrition Intervention Is Effective in Improving Dietary Components Linked to Cardiometabolic Risk in Youth with First-Episode Psychosis. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, M.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Han, P.; Lv, L.; Yang, C.; Han, Y. Calorie-Restricted Diet Mitigates Weight Gain and Metabolic Abnormalities in Obese Women with Schizophrenia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, L.M.; Ravussin, E. Caloric Restriction in Humans: Impact on Physiological, Psychological, and Behavioral Outcomes. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2011, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrzycki, A.; Cierpka-Kmiec, K.; Kmiec, Z.; Wronska, A. The Role of Low-Calorie Diets and Intermittent Fasting in the Treatment of Obesity and Type-2 Diabetes. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy, H.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Astrup, A.; Wycherley, T.P.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Woods, S.C.; Mattes, R.D. The Role of Protein in Weight Loss and Maintenance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, F.; Gennusa, J. V.; Stallings, C.; Origoni, A.; Katsafanas, E.; Sweeney, K.; Campbell, W.W.; Yolken, R. Protein Intake Is Associated with Cognitive Functioning in Individuals with Psychiatric Disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, R.N.; Kim, S.P.; Hsu, I.R.; Catalano, K.J.; Chiu, J.D.; Kabir, M.; Richey, J.M.; Ader, M. Abdominal Obesity: Role in the Pathophysiology of Metabolic Disease and Cardiovascular Risk. Am. J. Med. 2007, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free Radicals: Properties, Sources, Targets, and Their Implication in Various Diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G.; Conquer, J. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2005, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.K.; Keshavan, M.S. Antioxidants, Redox Signaling, and Pathophysiology in Schizophrenia: An Integrative View. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2011, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndhlala, A.R.; Moyo, M.; Van Staden, J. Natural Antioxidants: Fascinating or Mythical Biomolecules? Molecules 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvindakshan, M.; Ghate, M.; Ranjekar, P.K.; Evans, D.R.; Mahadik, S.P. Supplementation with a Combination of ω-3 Fatty Acids and Antioxidants (Vitamins E and C) Improves the Outcome of Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2003, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, H.; Osnes, K.; Refsum, H.; Solberg, D.K.; Bøhmer, T. A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of an Omega-3 Fatty Acid and Vitamins E+C in Schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.E.; Roffman, J.L. Vitamin Supplementation in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 2014, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobica, A.; Padurariu, M.; Dobrin, I.; Stefanescu, C.; Dobrin, R. Oxidative Stress in Schizophrenia - Focusing on the Main Markers. Psychiatr. Danub. 2011, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Buosi, P.; Borghi, F.A.; Lopes, A.M.; da Silva Facincani, I.; Fernandes-Ferreira, R.; Oliveira-Brancati, C.I.F.; Do Carmo, T.S.; Souza, D.R.S.; da Silva, D.G.H.; de Almeida, E.A.; et al. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Treatment-Responsive and Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia Patients. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Othmen, L.; Mechri, A.; Fendri, C.; Bost, M.; Chazot, G.; Gaha, L.; Kerkeni, A. Altered Antioxidant Defense System in Clinically Stable Patients with Schizophrenia and Their Unaffected Siblings. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyazuddin, M.; Azmi, S.A.; Islam, N.; Rizvi, A. Oxidative Stress and Level of Antioxidant Enzymes in Drug-Naive Schizophrenics. Indian J. Psychiatry 2014, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, V.; Lazarevic, D.; Cosic, V.; Knezevic, M.; Djordjevic, V. Age-Related Changes of Superoxide Dismutase Activity in Patients with Schizophrenia. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2017, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjević, V. V.; Kostić, J.; Krivokapić, Ž.; Krtinić, D.; Ranković, M.; Petković, M.; Ćosić, V. Decreased Activity of Erythrocyte Catalase and Glutathione Peroxidase in Patients with Schizophrenia. Med. 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawryluk, J.W.; Wang, J.F.; Andreazza, A.C.; Shao, L.; Young, L.T. Decreased Levels of Glutathione, the Major Brain Antioxidant, in Post-Mortem Prefrontal Cortex from Patients with Psychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.K.; Leonard, S.; Reddy, R. Altered Glutathione Redox State in Schizophrenia. Dis. Markers 2006, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, A.J.; Rogers, J.C.; Katshu, M.Z.U.H.; Liddle, P.F.; Upthegrove, R. Oxidative Stress and the Pathophysiology and Symptom Profile of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich-Muszalska, A.; Kwiatkowska, A. Generation of Superoxide Anion Radicals and Platelet Glutathione Peroxidase Activity in Patients with Schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, T.M.; Thome, J.; Martin, D.; Nara, K.; Zwerina, S.; Tatschner, T.; Weijers, H.G.; Koutsilieri, E. Cu, Zn- And Mn-Superoxide Dismutase Levels in Brains of Patients with Schizophrenic Psychosis. J. Neural Transm. 2004, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, D.S.P.; Monteiro, H.P.; Oliveira, J.A.C.; Bechara, E.J.H. Activities of Superoxide Dismutase and Glutathione Peroxidase in Schizophrenic and Manic-Depressive Patients. Clin. Chem. 1986, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjević, V. Superoxide Dismutase in Psychiatric Diseases. In; 2022.

- Hurşitoğlu, O.; Orhan, F.Ö.; Kurutaş, E.B.; Doğaner, A.; Durmuş, H.T.; Kopar, H. Diagnostic Performance of Increased Malondialdehyde Level and Oxidative Stress in Patients with Schizophrenia. Noropsikiyatri Ars. 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmini, M.S.; D’Souza, B.; D’Souza, V. Superoxide Dismutase and Catalase Activities and Their Correlation with Malondialdehyde in Schizophrenic Patients. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2004, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarandol, A.; Kirli, S.; Akkaya, C.; Altin, A.; Demirci, M.; Sarandol, E. Oxidative-Antioxidative Systems and Their Relation with Serum S100 B Levels in Patients with Schizophrenia: Effects of Short Term Antipsychotic Treatment. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surapaneni, K.; Venkataramana, G. Status of Lipid Peroxidation, Glutathione, Ascorbic Acid, Vitamin E and Antioxidant Enzymes in Patients with Osteoarthritis. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2007, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, H.; Tang, W.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, F.X.; Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Elevated Plasma Superoxide Dismutase in First-Episode and Drug Naive Patients with Schizophrenia: Inverse Association with Positive Symptoms. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Zhao, R.; Yang, B. Superoxide Dismutase Activity and Malondialdehyde Levels in Patients with Travel-Induced Psychosis. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2012, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Xiu, M.H.; Guan, X.N.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, J.; Leung, E.; Zhang, X.Y. Altered Antioxidant Defenses in Drug-Naive First Episode Patients with Schizophrenia Are Associated with Poor Treatment Response to Risperidone: 12-Week Results from a Prospective Longitudinal Study. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, K.Q.; Bovet, P.; Cuenod, M. Schizophrenia: Glutathione Deficit as a New Vulnerability Factor for Disconnectivity Syndrome. Schweizer Arch. fur Neurol. und Psychiatr. 2004, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffa, M.; Atig, F.; Mhalla, A.; Kerkeni, A.; Mechri, A. Decreased Glutathione Levels and Impaired Antioxidant Enzyme Activities in Drug-Naive First-Episode Schizophrenic Patients. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langbein, K.; Hesse, J.; Gussew, A.; Milleit, B.; Lavoie, S.; Amminger, G.P.; Gaser, C.; Wagner, G.; Reichenbach, J.R.; Hipler, U.C.; et al. Disturbed Glutathione Antioxidative Defense Is Associated with Structural Brain Changes in Neuroleptic-Naïve First-Episode Psychosis Patients. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaniyappan, L.; Park, M.T.M.; Jeon, P.; Limongi, R.; Yang, K.; Sawa, A.; Théberge, J. Is There a Glutathione Centered Redox Dysregulation Subtype of Schizophrenia? Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, Y.; Nakajima, S.; Plitman, E.; Truong, P.; Bani-Fatemi, A.; Caravaggio, F.; Kim, J.; Shah, P.; Mar, W.; Chavez, S.; et al. Glutathione Levels and Glutathione-Glutamate Correlation in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. Open 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhale, G.N.; Khanzode, S.D.; Khanzode, S.S.; Saoji, A. Supplementation of Vitamin C with Atypical Antipsychotics Reduces Oxidative Stress and Improves the Outcome of Schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarandol, A.; Sarandol, E.; Acikgoz, H.E.; Eker, S.S.; Akkaya, C.; Dirican, M. First-Episode Psychosis Is Associated with Oxidative Stress: Effects of Short-Term Antipsychotic Treatment. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunes, M.; Camkurt, M.A.; Demir, S.; Ibiloglu, A.; Kaya, M.C.; Bulut, M.; Atli, A. Serum Malonyldialdehyde Levels of Patients with Schizophrenia. Klin. Psikofarmakol. Bul. 2015, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kropp, S.; Kern, V.; Lange, K.; Degner, D.; Hajak, G.; Kornhuber, J.; Rütlier, E.; Emrich, H.M.; Schneider, U.; Bleich, S. Oxidative Stress during Treatment with First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2005, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.M.N.; Sultana, F.; Uddin, M.G.; Dewan, S.M.R.; Hossain, M.K.; Islam, M.S. Effect of Antioxidant, Malondialdehyde, Macro-Mineral, and Trace Element Serum Concentrations in Bangladeshi Patients with Schizophrenia: A Case-Control Study. Heal. Sci. Reports 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.Z.; Yun, L.T.; Dong, F.Z.; Lian, Y.C.; Gui, Y.W.; Haile, C.N.; Kosten, T.A.; Kosten, T.R. Disrupted Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Elevated Lipid Peroxidation Products in Schizophrenic Patients with Tardive Dyskinesia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fartusie, F.S.; Al-Bairmani, H.K.; Al-Garawi, Z.S.; Yousif, A.H. Evaluation of Some Trace Elements and Vitamins in Major Depressive Disorder Patients: A Case–Control Study. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myken, A.N.; Ebdrup, B.H.; Sørensen, M.E.; Broberg, B. V.; Skjerbæk, M.W.; Glenthøj, B.Y.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Nielsen, M. Lower Vitamin C Levels Are Associated with Less Improvement in Negative Symptoms in Initially Antipsychotic-Naïve Patients with First-Episode Psychosis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subotičanec, K.; Folnegović-Šmalc, V.; Korbar, M.; Meštrović, B.; Buzina, R. Vitamin C Status in Chronic Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 1990, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Xiu, M.; Wu, F.; Zhang, X. Total Antioxidant Capacity, Obesity and Clinical Correlates in First-Episode and Drug-Naïve Patients with Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2024, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Weidinger, E.; Leitner, B.; Schwarz, M.J. The Role of Inflammation in Schizophrenia. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Inflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.J.; Goldsmith, D.R. Inflammatory Biomarkers in Schizophrenia: Implications for Heterogeneity and Neurobiology. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatry 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhuo, M.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xiong, D.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Altered Gut Microbiota Associated with Symptom Severity in Schizophrenia. PeerJ 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deledda, A.; Annunziata, G.; Tenore, G.C.; Palmas, V.; Manzin, A.; Velluzzi, F. Diet-Derived Antioxidants and Their Role in Inflammation, Obesity and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The type of diet | Description | Effects on obesity | Mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketogenic Diet | High in fat, moderate in protein, low in carbohydrates | Weight loss, reductions in visceral adipose tissue, glycosylated hemoglobin and triglycerides | Mood stabilization and cognitive function | [74] |

| Mediterranean diet | Rich in vegetables, fruits, fish, olive oil, whole grains | Reduces the risk of obesity and improving metabolism | Improves metabolic and immunity outcomes | [75,76] |

| Diet DASH | Rich in vegetables, fruits, low-fat dairy products, whole grains | lowers triglycerides, lowers fasting blood glucose and improves insulin resistance | Reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, improve vascular and metabolic function. | [77,78] |

| Calorie restriction diet | Caloric restriction with balanced intake of macronutrients | Improves weight and metabolic markers | Reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, improve insulin sensitivity and metabolic health. | [79] [80,81] |

| High Protein Diet | Includes animal and vegetable protein sources | Maintain muscle mass, reducing body fat | Stabilizing blood sugar, reducing inflammation and improving neural function. | [82,83] |

| Gluten-free diet | Exclude all foods containing gluten | Improvements in negative symptoms | Reducing inflammatory responses | [64] |

| Parameter category | Evaluated parameter | The level found relative to the normal range | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant enzyme | GPx | Normal level | [93] |

| Low level | [94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101] | ||

| SOD | Low level | [93,95,101,102] | |

| Increased level | [103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110] | ||

| CAT | Increased level | [93,105,106,111] | |

| Low level | [97,102] | ||

| GSH | Low level | [112][113,114,115,116] | |

| Biomarkers | MDA | Increased level | [93,95,97,105,108,110,117,118,119,120,121,122] |

| Antioxidants | Vitamin E | Low level | [108,121,123] |

| Vitamin C | Low level | [117,121,124,125] | |

| CAT, catalase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GSH, glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD = superoxide dismutase. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).