1. Introduction

Vertigo and balance disorders are some of the most frequent reasons for consultation in Primary Care and Otorhinolaryngology. Dizziness is suggested to handicap the patients significantly, especially on daily activities. Moreover, the fluctuating occurrence of symptoms combined with an unpredictable evolution of balance disorders over time explain a higher hazard in patients with certain occupations (e.g. road hauliers, bus drivers or workers at heights) or, at least, emotional distress related to this risk.

We hypothesized that not only clinical variables (e.g. severity, duration and frequency of vertigo attacks) and associated symptoms (e.g. nausea, vomiting, hearing loss, headache and photophobia) but also environmental factors influence the quality of life in patients who experience vertigo or disequilibrium. Might these factors (such as diet, weather changes, marital status, stress and anxiety, or occupation) influence clinical features, emotional functioning, quality of life, and even the ability to carry out their work activities? As these factors are external variables, the introduction of measures to change some of them is relatively easy. However, other ones are not likely to be modified. Recent studies on putative relationship between caffeine consumption [

1], alcohol consumption [

2], atmospheric pressure changes [

3] or stress [

4], and clinical features of Menière’s disease were published.

It is known that balance disorders involve occupational hazards, even life-threatening ones. To date, however, the inverse relationship (between certain occupations and an increased incidence of vertigo or dizziness) has been scarcely studied.

It is well known that the exposition to dangerous working environmental factors at certain workplaces may result in diseases, so-called “occupational diseases”. In Spain, “noise-induced hearing loss” is the only occupational disease related to the inner ear recognized. There are scarcely studies on a putative relationship between occupation and vertigo. Consistent with this situation, no balance disorder has been recognized as “occupational disease”. However, we believe that the putative association must be studied to improve the knowledge of balance disorders and to introduce measures to encourage improvements in the safety, health and clinical management of patients affected. Moreover, we consider that further studies are required to evaluate the association between noise exposure and vestibular damage because this question has been little studied [5─8]. Recent studies suggest an exposure-response association between exposure to strong static magnetic fields and transient symptoms such as vertigo among healthcare and research staff [

9]. In vivo animal models confirmed that some utricular and saccular afferents can be evoked by both air conducted sound and bone conducted vibration [

10]. This is in accordance with the physiopathological basis of vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs); air conducted sound or bone conducted vibration stimulation are used in the clinic to evoke vestibular responses, which can be recorded and measured. Several cases of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo have been reported in skeet shooters and hunters [

11], considering that the transmission of impulsive and vibratory energy from the shoulder may be responsible of the otoconia detachment. In an extensive review conducted on the adverse health effects associated with occupational exposure to vibration [

12], the presence of dizziness and motion sickness was described, but without describing any specific association between vibrations and vestibular diseases. In addition, we hypothesized that exposure to mechanically-generated vibrations might be also associated to balance disorders by mechanistic origin (e.g. benign paroxysmal positional vertigo because of detachment of otoconia). There are very few publications that study this relationship [

13].

Based on previously mentioned, the main objective of our study was to analyze the occupation of a group of patients with vertigo, compared to economically active general population; specifically, we intend to study whether the group of patients showed occupations that require greater physical activity or exposure to potentially aggressive external factors (and that could be etiological agents of vertigo). As secondary objectives, we proposed to analyze the prevalence of occupational noise-exposure and occupational vibration-exposure in patients with vertigo and to compare it to that observed in economically active population, and to evaluate the aforementioned data jointly, including women and men, distinguishing by gender.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This is a cross-sectional, observational, case-control study. Data were prospectively recorded for three years. All participants were recruited from patients affected by vertigo who had been referred to the Neurotology Unit of a tertiary hospital.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Patients with definite diagnosis of any of the following four disorders were asked to participate in the study:

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

Patients <18 years old;

Patients with vertigo of two or more causes simultaneously;

Patients with systemic diseases or locomotor pathologies that had conditioned the choice of their occupations;

Patients affected by severe cognitive decline that prevented from obtaining informed consent.

2.4. Methodology

In order to establish a diagnosis, all participants with vertigo underwent a complete neuro-otologic examination, including otoscopy, basic neurologic exploration, observation (and, in some cases, record) of spontaneous nystagmus, head-impulse test, positional tests (Dix and Hallpike, McClure, and cephalic hyperextension tests), and pure tone audiometry. When they were necessary, videonystagmography (with caloric tests) and vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) were performed. All patients diagnosed of Menière’s disease underwent encephalic MRI with the aim of excluding other causes of their symptoms.

Variables obtained and studied from all patients were the following:

Age;

Sex;

Diagnosis.

Occupation. Anamneses included occupational history. The participants were asked about all their jobs throughout their lives (not just their current one). The main job (that one to which they had dedicated the most time of their working life) was registered;

Occupational exposure to noise;

Occupational exposure to vibrations.

Occupations of patients and control subjects were classified into ten major groups according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations, 2008 (ISCO-08) and its Spanish version (National Classification of Occupations NCO-11 2010) [

17]. This occupational classification system distinguishes ten major groups (

Table 1).

In addition to these ten groups, other group was added in our study. This new group included “housewives, students, and unemployed people”. On the other hand, retired people were also included in the study, recording the main occupation in their working lives. In Spain, the Social Security National Institute (SSNI) published in 2014 the third edition of “Occupational Evaluation Guide” [

18], including 502 specific descriptions of all occupations recognized by NCO-11. These 502 data sheets provide information on a broad range of issues, including “risk factors and specific working conditions”. These factors and conditions were classified into three categories (possible risks from the work environment, possible risks from the use of tools or machinery, and specific circumstances of the workplace). We select the following:

Possible risks from the work environment. Our study assessed one of them: “exposure to noise”;

Possible risks from the use of tools or machinery. Our study selected “exposure to vibrations from tools or machinery”.

Data on exposure or no exposure to occupational noise were obtained in all participants. We assumed that a subject was exposed to occupational noise if this exposure was included as a risk of the work environment, in the SSNI specifications corresponding to his occupation. For all patients, information related to possible occupational exposure to mechanically-generated vibrations was also obtained from SSNI datasheet of each occupation.

2.5. Sample Size Estimation

For the estimation of the sample size, we used the percentage of individuals with occupational exposure to noise as a reference, which was 28% in the control group. Considering that the exposure to noise in no case could be a protective factor against the appearance of vertigo, we estimate as significant a difference of 10% of exposed individuals comparing both groups. With a 95% confidence level (1-α) and a 90% statistical power, for a unilateral hypothesis test, a total of 377 subjects was deemed the number necessary in each of the two groups.

2.6. Sample

A total of 461 patients were included in the study sample (220 with MD, 73 with VM, 28 with VN, and 140 with BPPV). The sample comprised 310 women and 151 men. The mean age of patients was 58.6 ± 14.594 years (range: 20.2–91.5 years). Data of sex and age of all participants distributed into the four diagnostic groups studied are shown in

Table 2.

It was assumed as control group, the national sample of the 6th EWCS-Spain [

19], which corresponds to the 2015 edition of the National Survey on Working Conditions and is part of the “Sixth European Working Conditions Survey” carried out by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). In 2015, Eurofound carried out the sixth survey in the series (in operation since 1991). The sixth EWCS was developed in 35 countries. In Spain, this survey interviewed 3,364 workers (1,714 men and 1,650 women) [

19]. The mean age of the participants was 43.46 ± 38.513 years. The interviewed working people were randomly selected, comprising a cross-section of society. Survey findings provide information on a broad range of issues, including exposure to physical risks. In the 6th EWCS-Spain, occupations were coded according to ISCO-08 and its Spanish version (NCO-11). This national survey shows a wide-ranging picture of Spanish economically active population, including distribution of workers by occupational category.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data were collected and entered into a database created especially for the purpose. Statistical analysis of results was performed with SPSS version 15.0 for Windows software program. To evaluate if continuous variables showed a normal distribution, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied. When normality could be assumed, relationships between those variables and the discrete variables were checked by t-Student test. When continuous variables did not show a normal distribution, Mann-Whitney non-parametric test was applied to analyze these relationships. The Chi-square test was applied to analyze relationships between discrete variables, and Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze 2x2 tables, with the calculation of the odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. The level of statistical significance for all tests was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

The control group included 3,364 participants. 461 patients affected by vertigo were recruited in the current study. With the aim of both groups were comparable in terms of registered occupation, those participants of control group whose data of occupation were not available, were excluded. We also excluded 67 patients for corresponding to the category of “housewives, students and unemployed people”, because this category had not been included in the control group (economically active population). Therefore, 394 patients with vertigo were compared to 3,362 subjects in control group.

There were statistically significant differences between both groups in relation to age (Mann-Whitney test, p=4.08 e-81). Subjects of control group were younger (mean age: 42.28 ± 11.276 years) than patients with vertigo (mean age: 57.42 ± 14.189 years). These differences of age are due to group of patients with vertigo includes retired people, as described above.

We also observed differences in distribution by sex (Fisher’s exact test, p=8.74 e-7; OR=1.708, CI95% (1.378;2.117)). In the control group, the number of females was similar to that of males (1,649 females vs 1,713 males; female/male ratio 0.96/1), while in the group of patients with vertigo the proportion of women was higher (245 females vs 149 males; female/male ratio 1.6/1). For this reason, differences in variables were analyzed not only in total sample but also separately by sex.

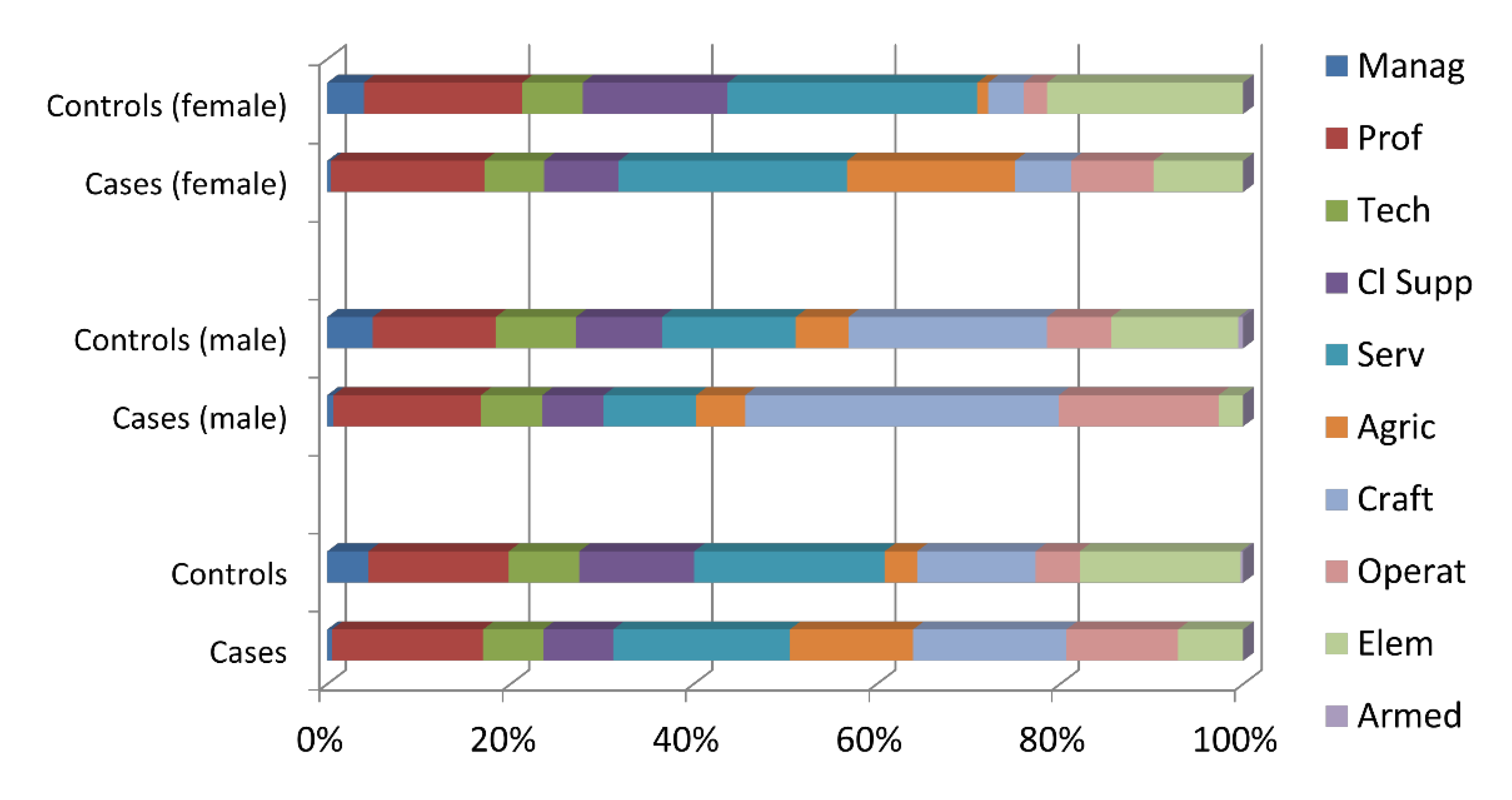

Regarding occupation of participants, statistically significant differences were detected between group of patients with vertigo and control group (Chi-square, p=6.142 e

-30). As can be seen in

Figure 1, occupations included in “clerical support workers” and “elementary occupations” categories showed a lower percentage among patients with vertigo than general population. By contrast, occupations of “skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers”, “craft and related trades workers” and “plant and machine operators and assemblers” categories showed a higher percentage among patients with vertigo (cases) than general population (control group). As seen in

Figure 1, differences between both groups (cases and controls) were also observed when these were separated and assessed by sex. These differences were statistically significant (Chi-square, p=3.468 e

-8, in male; p=5,927 e

-48, in female).

When occupational exposure to noise was analyzed, statistically significant differences were also observed between both (cases and control) groups (Fisher’s exact test, p=8.19 e-12; OR=2,127, CI95% (1.720;2.630)). Patients with vertigo were much more exposed to noise (177 patients, 44.9% of patients were exposed) than participants in control group (932 subjects, 27.7% of participants were exposed). When exposure by sex was analyzed, it could be observed that males experienced greater occupational exposure to noise than females. An important percentage of men affected by vertigo in our sample was occupationally exposed to noise (61%, a total of 92 men), while the women with vertigo exposed to noise accounted for 27% (a total of 85 women). Based on this fact, exposure to noise in men and women was studied separately, comparing cases vs controls for each sex. Males suffering from vertigo had higher noise exposures (92 from 149, 61.7 %) than control males (627 from 1713, 36.6 %); these differences were statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p=3.81 e-9; OR=2.796, CI95% (1.981;3.946)). Similar findings were observed among women: 34.7% (85 from 245) of women with vertigo were exposed to noise, whereas only 18.5% of control women were exposed (305 from 1649). Differences between both groups of women were also statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p=3.95 e-8; OR=2.341, CI95% (1.750;3.132)).

Statistically significant differences were also found when occupational exposure to vibrations was studied (Fisher’s exact test, p=1.11 e-12; OR=2.288, CI95% (1.835;2.853)); this exposure was more frequent among patients with vertigo (147 patients, 37.3% of patients were exposed) than in control group (694 subjects, 20.6% of subjects were exposed). Again, gender differences in occupational vibration exposure were found. Males were also more exposed to this risk (72 men, 48% of all men included in our sample) than females (75 women, 24% of all women included in our sample). Therefore, differences between cases and control were analyzed by gender. In men, 72 from 149 males suffering from vertigo were exposed to vibrations (48.3%), whereas control participants were exposed 548 from 1703 (32%). This difference was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p=8.65 e-5; OR=1.988, CI95% (1.419;2.784)). In women, proportion of those exposed to vibration was higher in women with vertigo (30.6%, 75/245) than in control women (8,9%, 146/1649). Again, these observed differences were statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p=6.32 e-15; OR=4.542, CI95% (3.296;6.257)).

4. Discussion

Vertigo and balance disorders are relatively common in general population and affect both the quality of life and the development of the occupational activities of patients. Several studies reported that lifestyle of patients and related factors may influence the clinical features of vertigo. The aim of our study was to advance in the knowledge of these factors and its association with balance disorders. The relationship between occupation and balance disorders has been scarcely studied, and to date, there have been published few studies analyzing only very specific occupations [

9]. Occupational noise-induced hearing loss is a recognized work-related illness, according to Spanish List of Occupational Diseases. Recently, it has been proposed that exposure to noise might affect vestibular system. Regarding mechanical vibrations, association between this physical risk factor and vestibular symptoms remains unknown. The purpose of this study was to analyze the putative relationship between occupation and related factors, and vertigo.

Our study sample comprised a total of 461 patients with vertigo, 310 women and 151 men (female/male ratio=2.05/1). The mean age of patients was 58.6 years old. Excluded from the study sample the “housewives, students and unemployed people” group (formed by 97% women), the female/male ratio was still showing a female predominance among patients with vertigo (1.6/1), while the number of women in control group was similar to men. The female predominance observed in our study is in accordance with the findings previously reported in several balance disorders. In Menière’s disease, almost all publications reported a higher prevalence of females, with percentages ranged from 53.2% [

20] to 80% [

21]. In vestibular migraine, similar findings were reported; it was observed that 84% of patients with vestibular migraine were women [

22], according to our results (75% of our patients were women). In BPPV, this higher prevalence of women was also reported (two-fold higher than that of men) [

23].

Differences in mean age were observed between patients with vertigo and control group. Our patients were older (mean age: 57 years old) than the control subjects (mean age: 42 years old). This difference must be assessed with caution, considering that the control group recruited only economically active subjects, while study sample also included retired people.

Statistically significant differences were observed when analyzing exposure to noise between men (61% exposed) and women (27% exposed). Consistent with the results of other studies [

24], in our sample, men experienced greater exposure to noise at work than women. Similar results were obtained when studying occupational exposure to vibrations; men were two-fold more exposed to vibrations (48%) than women (24%). Both physical risk factors are related to occupational categories of patients, and so, these differences in exposure to noise and vibrations are likely due to differences in distribution of occupational categories among males and females. These findings are in accordance with the results of other studies. Worldwide, occupational risks are not distributed evenly among all workers [

24]. Males remain represented at higher rates than females in certain occupations with high noise/vibrations exposures. According to the 6th EWCS findings, differences in terms of gender and occupation are still significant in Europe. Our study also indicates that differences regarding “work at heights” are even greater between men and women, being exceptional among women. As a consequence of this finding, not only differences between all cases and controls but also differences by gender (cases vs controls in females, and cases vs controls in males) were analyzed.

When demographic characteristics and occupation of patients with vertigo (excluding the group “housewives, students and unemployed people”, in order to be comparable) were compared to general population, in addition to the aforementioned differences by gender, there were also observed statistically significant differences in the occupation of the subjects. We consider these findings relevant since they were obtained once the “housewives, students and unemployed people” group was excluded, taking into account that this group represents a high proportion of patients with vertigo (14.5%) and it is mostly comprised by women. “Clerical support workers” and “elementary occupations” are occupational groups represented at lower rates among patients with vertigo, compared to general population; by contrast, “skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers”, “craft and related trades workers” and “plant and machine operators and assemblers” are occupational groups more represented in patients with vertigo than in general population. These results seem to indicate that overall, the prevalence of vertigo may be higher in occupations involving greater physical efforts and handling machinery, whereas more sedentary occupations may be considered as “protective” from suffering vertigo.

Patients with vertigo were more exposed to noise (44.9%) than control subjects (27.7%), which seems to indicate that noise might induce or modulate vestibular pathology. Occupational exposure to vibrations were also more prevalent among patients with vertigo (37.3%), compared to general population (20.6%). These differences were also detected in the analysis carried out for each of the two sexes separately. This finding may be likely due to those occupations involving noise exposure also require the use of tools and machinery that generate vibrations, and even and likely more important, may be due to tools and machinery generating vibrations also produce noise. The influence of occupational exposure to noise and vibrations on vestibular damage has so far been very little studied. There are papers that analyze the damage produced in the auditory system, but without reference to possible vestibular injuries [

25]. In our opinion, the relationship that we found between vibrations and vertigo is especially relevant. Although occupational exposure to vibrations has been reported to cause dizziness and motion sickness [

12], to our knowledge, there are very few manuscripts that suggest the existence of a relationship between vibrations in the workplace and some vestibular diseases [

13].

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the control group included only economically active population (although several participants in this group were over eighty years old); that made difficult to compare our study sample and the control group by age. However, we considered that the study sample must include retired people because they are a very important subgroup of patients attended at the Neurotology Units.

Secondly, we included in our study a new group (different to those recognized by ISCO-08) not defined in the control group: “housewives, students and unemployed people”. If this group had been excluded, an important part of the patients who come to the consultation had been eliminated. In the case of “housewives”, we think that it is in fact an occupational group even though they are unpaid workers. However, to minimize bias, the study was conducted not only including this group but also excluding it (in this last case, to compare to economically active population). Our study sample did not recruit any patient included in “armed forces occupations”, which are represented in control group. We hypothesize that it is due to this occupational group, at least in Spain, is located only in certain geographical places different to geographical areas attended by our hospital.

Thirdly, occupations with higher risk or that require more physical activity could be somewhat oversized in the group of patients with vertigo. These people may be more diligent in seeking medical attention than those with a more sedentary work activity.

Fourthly, the division between exposed and unexposed (to noise and/or vibrations) is perhaps somewhat simple. Exposure dosing and characteristics (noise level, vibration frequency, acceleration, anatomical region or surface exposed…) would be needed to properly document if exposure risk is elevated. But, in our opinion, our study allows a first approximation to establish a possible etiological relationship between vertigo and exposure to noise and vibrations, which is the essential objective of this study. Once this association has been established, it will be necessary to specify in more detail, in future studies, which are the exposure thresholds (in intensity, in time, in body surface ...) that may favor the development of vertigo and vestibular dysfunction.

5. Conclusions

There was a relevant difference in occupational groups distribution observed in patients with vertigo, compared to general population. There was an association between vertigo and certain occupations involving physical efforts and a higher exposure to certain risks factors such as noise and vibrations. We consider that collective and individual preventive and protective measures must be improved to safeguard the health of workers and ensure a high degree of protection against noise or vibrations (e.g. reducing the time of exposure). We propose that these protective and preventive measures might reduce the incidence or improve the evolution of certain diseases that cause vertigo.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.SS. and A.SV.; methodology, I.SS. and A.SV.; software, A.SV.; formal analysis, A.SV.; investigation, I.SS. and A.SV.; resources, I.SS. and A.SV.; data curation, I.SS. and A.SV.; writing—original draft preparation, A.SV.; writing—review and editing, I.SS.; visualization, I.SS.; supervision, A.SV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Independent Ethics Committee (protocol code 2018/527, approval date: December 19, 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sánchez-Sellero, I.; San-Román-Rodríguez, E.; Santos-Pérez, S.; Rossi-Izquierdo, M.; Soto-Varela, A. Caffeine intake and Menière’s disease: Is there relationship? Nutr Neurosci 2018, 21, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Sellero, I.; San-Román-Rodríguez, E.; Santos-Pérez, S.; Rossi-Izquierdo, M.; Soto-Varela, A. Alcohol consumption in Menière’s disease patients. Nutr Neurosci 2020, 23, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürkov, R.; Strobl, R.; Heinlin, N.; Krause, E.; Olzowy, B.; Koppe, C.; Grill, E. Atmospheric Pressure and Onset of Episodes of Menière’s Disease - A Repeated Measures Study. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0152714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, N.L.; White, M.P.; Ronan, N.; Whinney, D.J.; Curnow, A.; Tyrrell, J. Stress and Unusual Events Exacerbate Symptoms in Menière’s Disease: A Longitudinal Study. Otol Neurotol 2018, 39, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, N.; Ila, K.; Soylemez, E.; Ozdek, A. Evaluation of vestibular system with vHIT in industrial workers with noise-induced hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2018, 275, 2659–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, P.; Scarpa, A.; Pisani, D.; Petrolo, C.; Aragona, T.; Spadera, L.; De Luca, P.; Gioacchini, F.M.; Ralli, M.; Cassandro, E.; Cassandro, C.; Chiarella, G. Sub-Clinical Effects of Chronic Noise Exposure on Vestibular System. Transl Med UniSa 2020, 22, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Soylemez, E.; Mujdeci, B. Dual-task performance and vestibular functions in individuals with noise induced hearing loss. Am J Otolaryngol 2020, 41, 102665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.E.; Holt, A.G.; Altschuler, R.A.; Cacace, A.T.; Hall, C.D.; Murnane, O.D.; King, W.M.; Akin, F.W. Effects of Noise Exposure on the Vestibular System: A Systematic Review. Front Neurol 2020, 11, 593919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, K.; Christopher-de Vries, Y.; Mason, C.K.; de Vocht, F.; Portengen, L.; Kromhout, H. Occupational exposure of healthcare and research staff to static magnetic stray fields from 1.5–7 Tesla MRI scanners is associated with reporting of transient symptoms. Occup Environ Med 2014, 71, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastras, C.J.; Curthoys, I.S.; Brown, D.J. Dynamic response to sound and vibration of the guinea pig utricular macula, measured in vivo using Laser Doppler Vibrometry. Hear Res 2018, 370, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, E.; Napolitano, B.; Di Girolamo, S.; De Padova, A.; Alessandrini, M. Paroxysmal positional vertigo in skeet shooters and hunters. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007, 264, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajnak, K. Health effects associated with occupational exposure to hand-arm or whole body vibration. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 2018, 21, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, N.; Ila, K. Effect of vibration on the vestibular system in noisy and noise-free environments in heavy industry. Acta Otolaryngol 2019, 139, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Carey, J.; Chung, W.H.; Goebel, J.A.; Magnusson, M.; Mandalà, M.; Newman-Toker, D.E.; Strupp, M.; Suzuki, M.; Trabalzini, F.; Bisdorff, A.; Classification Committee of the Barany Society; Japan Society for Equilibrium Research; European Academy of Otology and Neurotology (EAONO); Equilibrium Committee of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS); Korean Balance Society. Diagnostic criteria for Menière's disease. J Vestib Res 2015, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Newman-Toker, D. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 2012, 22, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Brevern, M.; Bertholon, P.; Brandt, T.; Fife, T.; Imai, T.; Nuti, D.; Newman-Toker, D. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 2015, 25, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda. Royal Decree 1591/2010, November 26, which approves the National Classification of Occupations 2011. BOE 2010, 306, 104040–104060. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2010/11/26/1591 (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Carbajo-Sotillo, M.D. Occupational Evaluation Guide, 3rd ed.; Instituto Nacional de la Seguridad Social: Madrid, Spain, 2014; pp. 1–1137, Available on: http://www.seg-social.es/wps/wcm/connect/wss/661ab039-b938-4e50-8639-49925df2e6bf/GUIA_VALORACION_PROFESIONAL_2014_reduc.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID= (accessed on 24 November 2021). [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH or INSHT). Department of Employment and Social Security. National Survey on Working Conditions 6ª EWCS-Spain; Instituto Nacional de Seguridad e Higiene en el Trabajo (INSHT): Madrid, Spain, 2015; pp. 1–134, Available on: https://www.insst.es/documents/94886/96082/Encuesta+Nacional+de+Condiciones+de+Trabajo+6%C2%AA+EWCS/abd69b73-23ed-4c7f-bf8f-6b46f1998b45 (accessed on 24 November 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Celestino, D.; Ralli, G. Incidence of Menière’s disease in Italy. Am J Otol 1991, 12, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaku, H.; Watanabe, Y. The prevalence of definite cases of Menière’s disease in the Hida and Nishikubiki districts of central Japan: a survey of relatively isolated areas of medical care. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1997, 528, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Teggi, R.; Colombo, B.; Albera, R.; Asprella Libonati, G.; Balzanelli, C.; Batuecas Caletrio, A.; Casani, A.P.; Espinosa-Sanchez, J.M.; Gamba, P.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Lucisano, S.; Mandalà, M.; Neri, G.; Nuti, D.; Pecci, R.; Russo, A.; Martin-Sanz, E.; Sanz, R.; Tedeschi, G.; Torelli, P.; Vannucchi, P.; Comi, G.; Bussi, M. . Clinical Features of Headache in Patients with Diagnosis of Definite Vestibular Migraine: The VM-Phenotypes Projects. Front Neurol 2018, 9, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Varela, A.; Santos-Perez, S.; Rossi-Izquierdo, M.; Sanchez-Sellero, I. Are the three canals equally susceptible to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Audiol Neurootol 2013, 18, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masterson, E.A.; Deddens, J.A.; Themann, C.L.; Bertke, S.; Calvert, G.M. Trends in worker hearing loss by industry sector, 1981-2010. Am J Ind Med 2015, 58, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rempel, D.; Antonucci, A.; Barr, A.; Cooper, M.R.; Martin, B.; Neitzel, R.L. Pneumatic rock drill vs. electric rotary hammer drill: Productivity, vibration, dust, and noise when drilling into concrete. Appl Ergon 2019, 74, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).