Submitted:

24 July 2024

Posted:

26 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

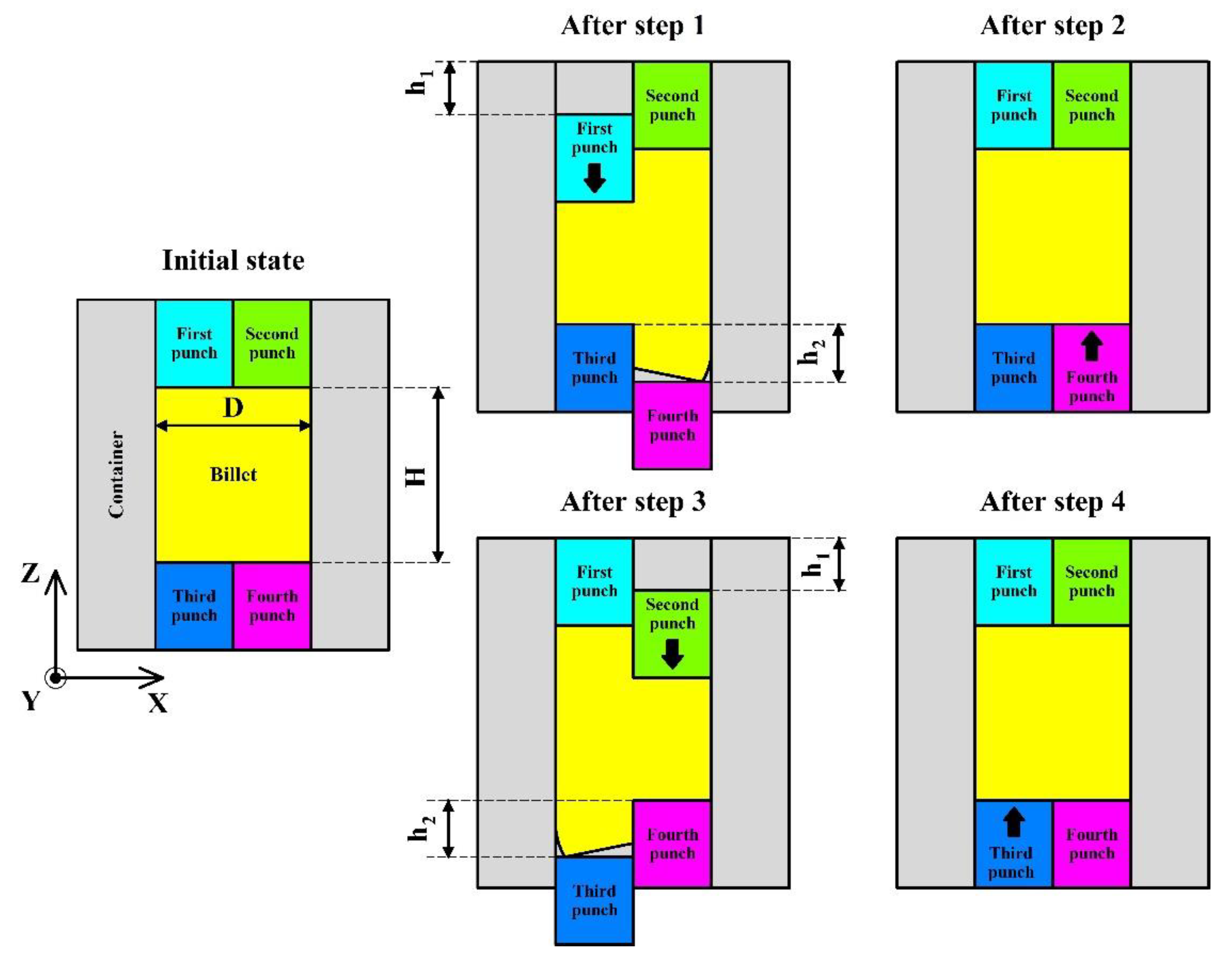

2.1. Process Principle

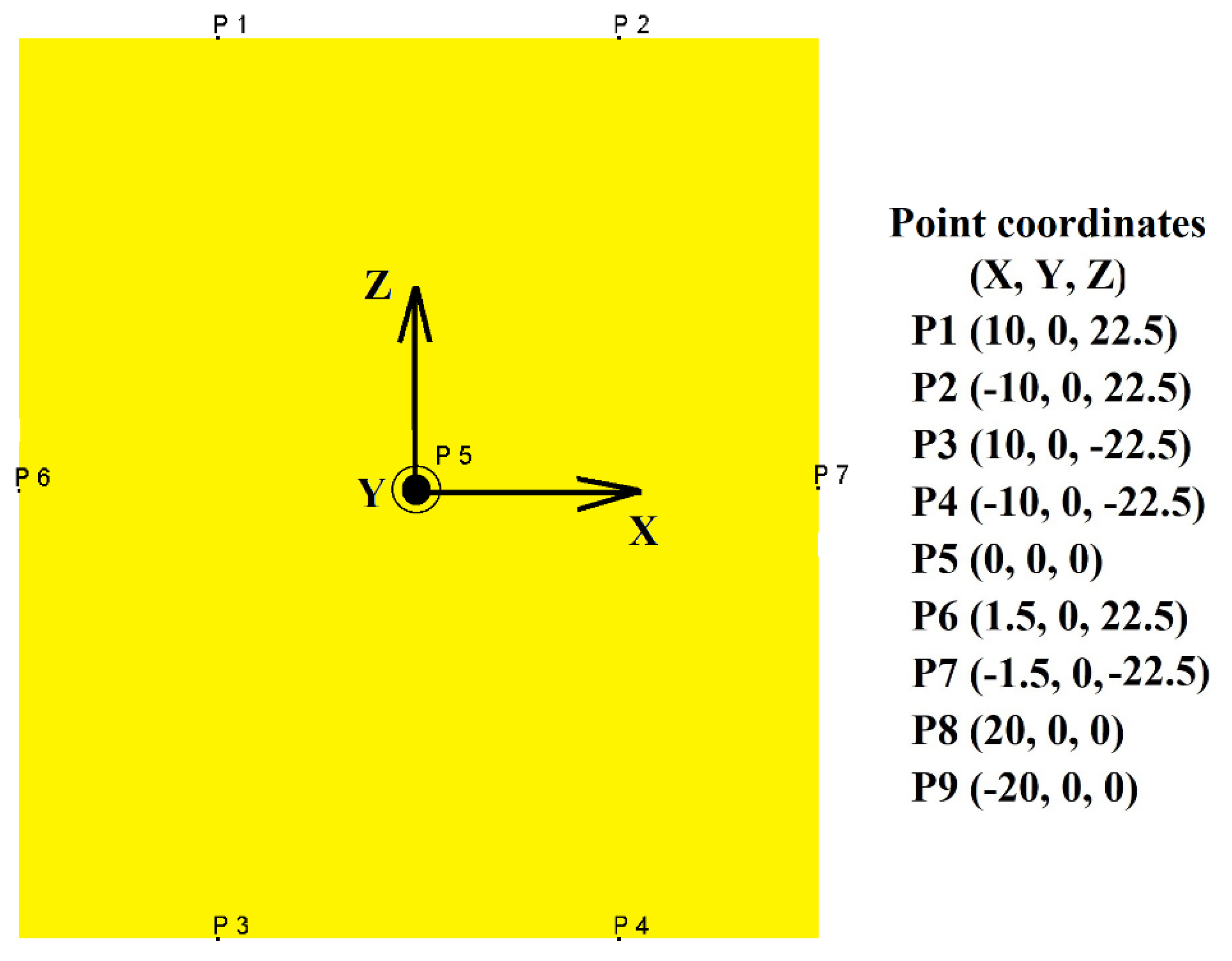

2.2. Numerical Simulation Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

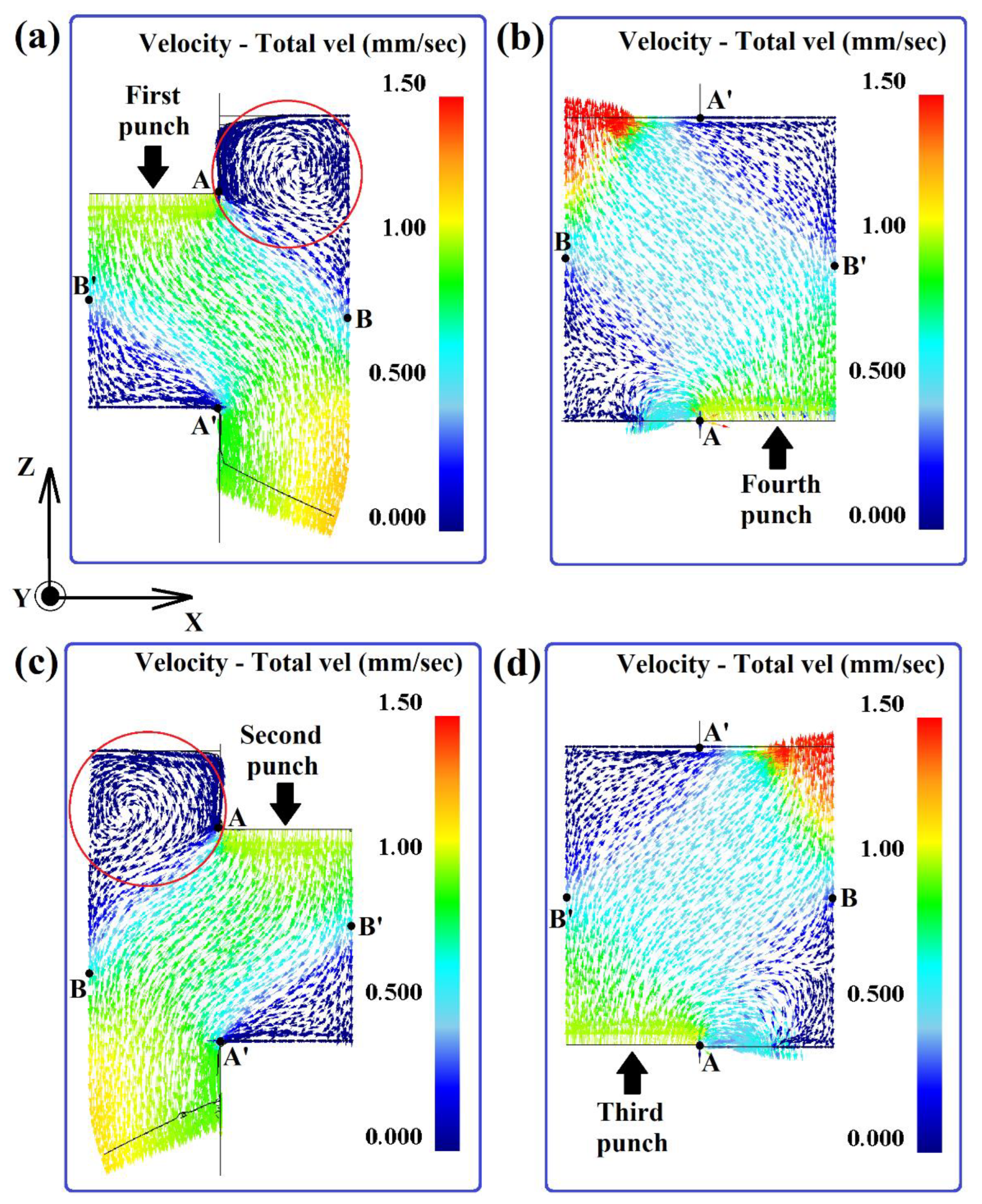

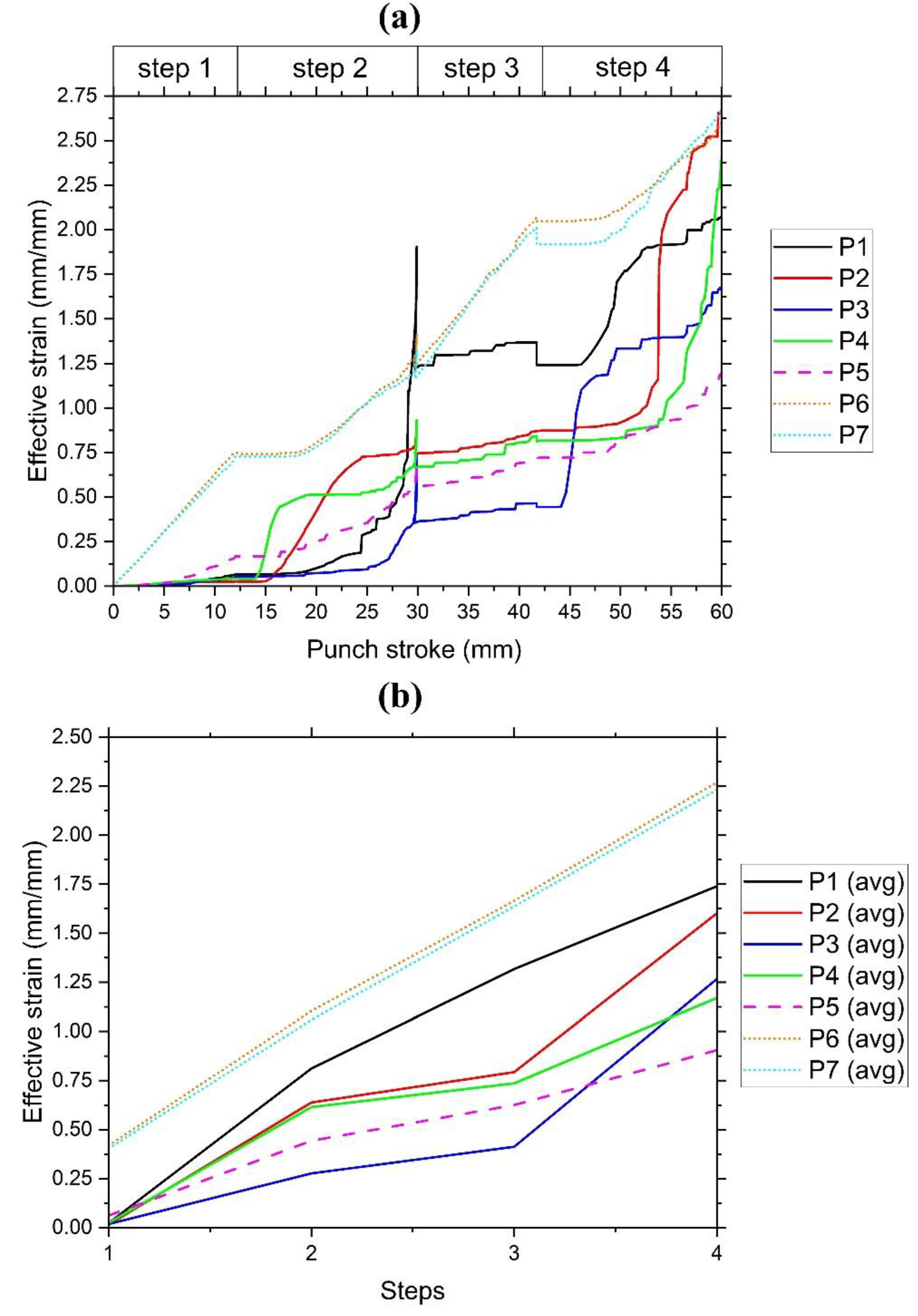

3.1. Metal Flow

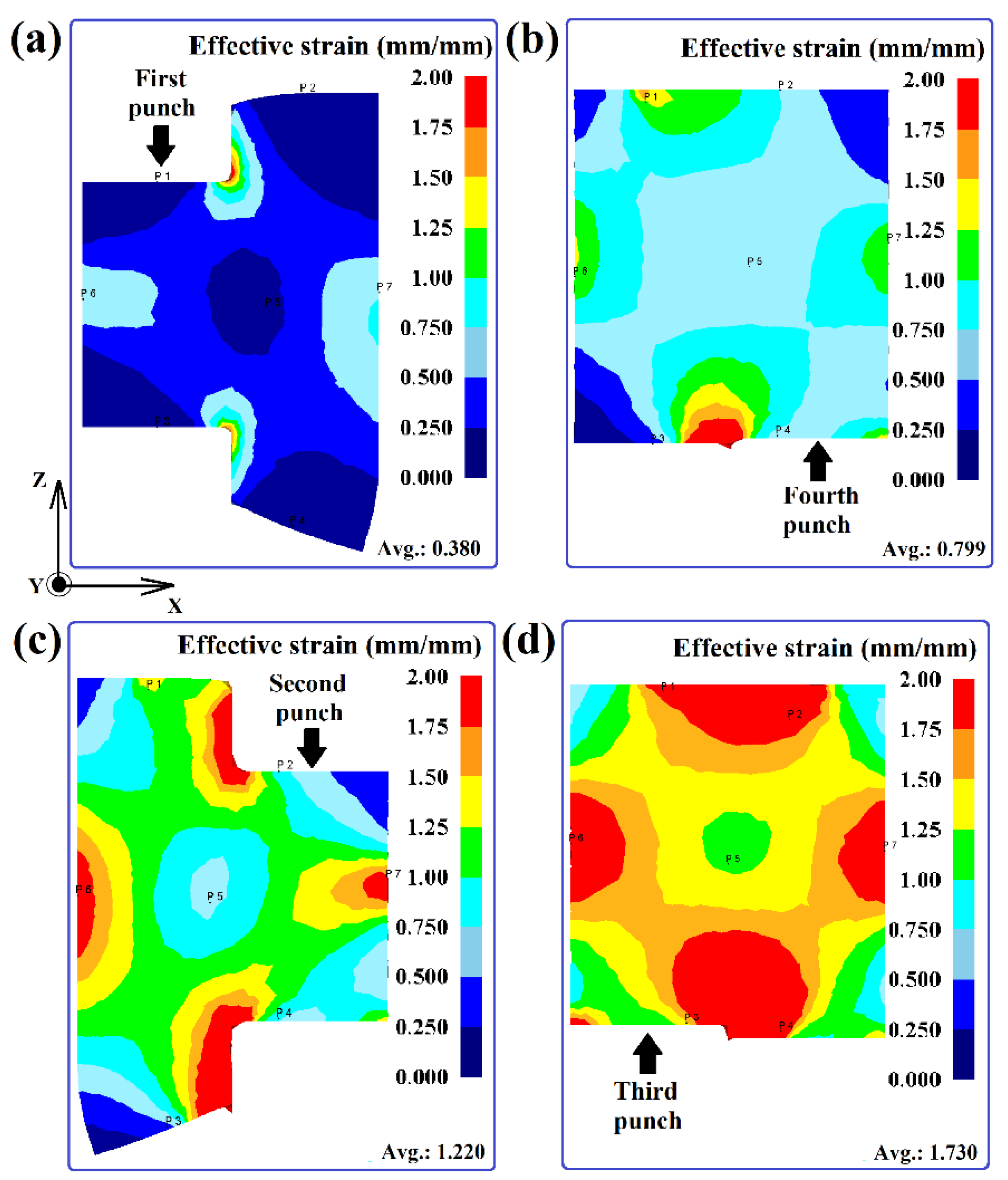

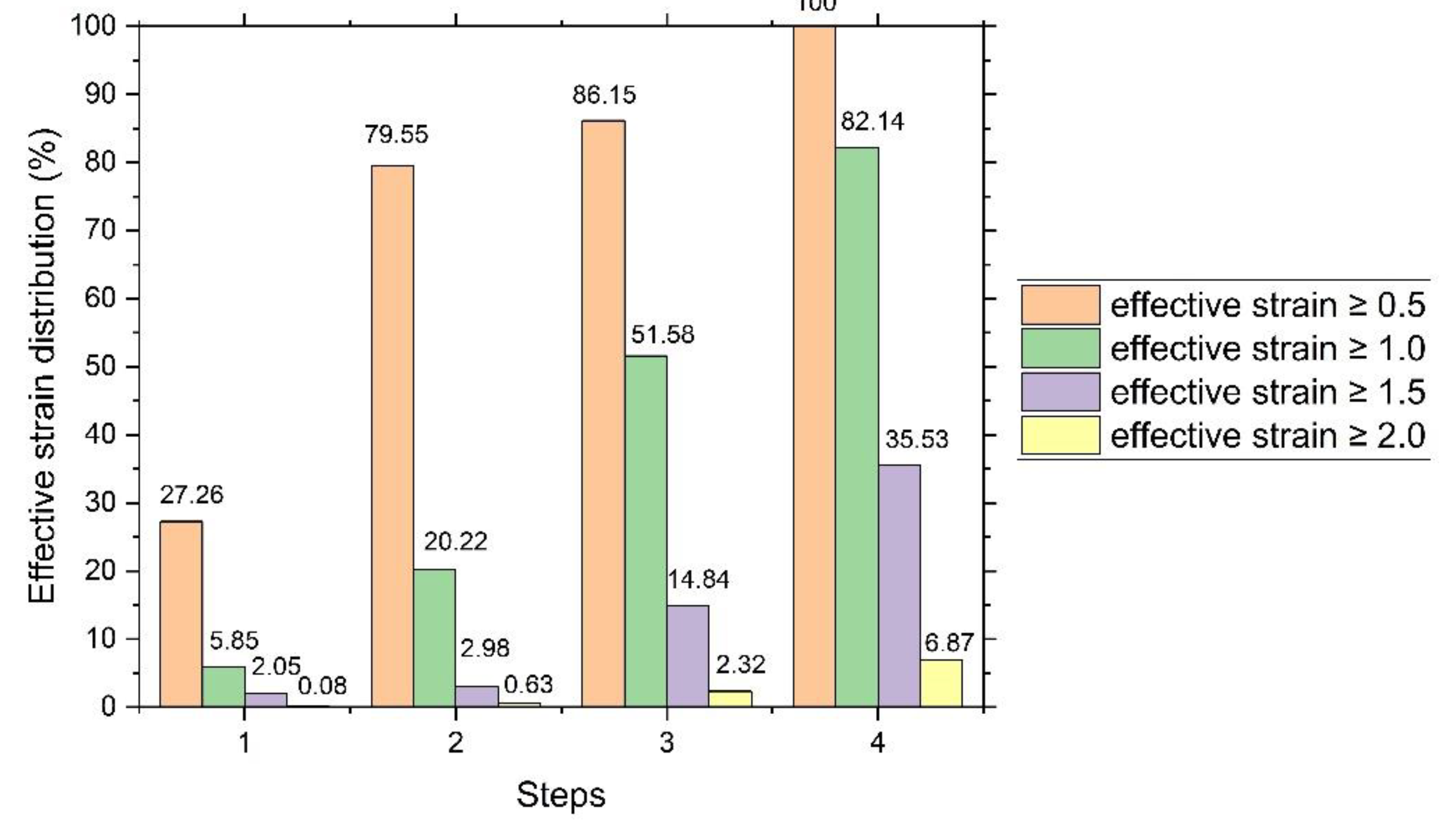

3.2. Effective Strain

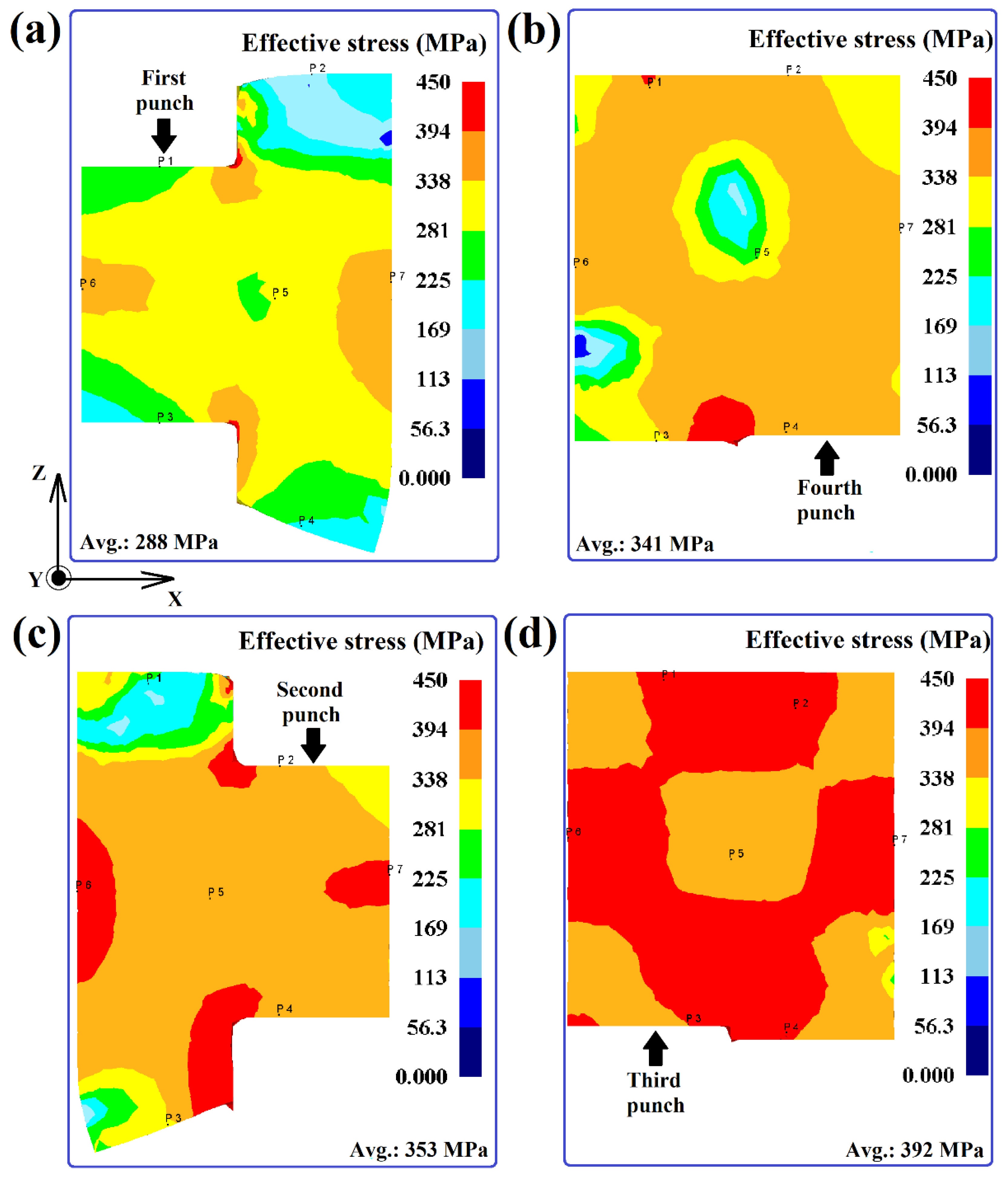

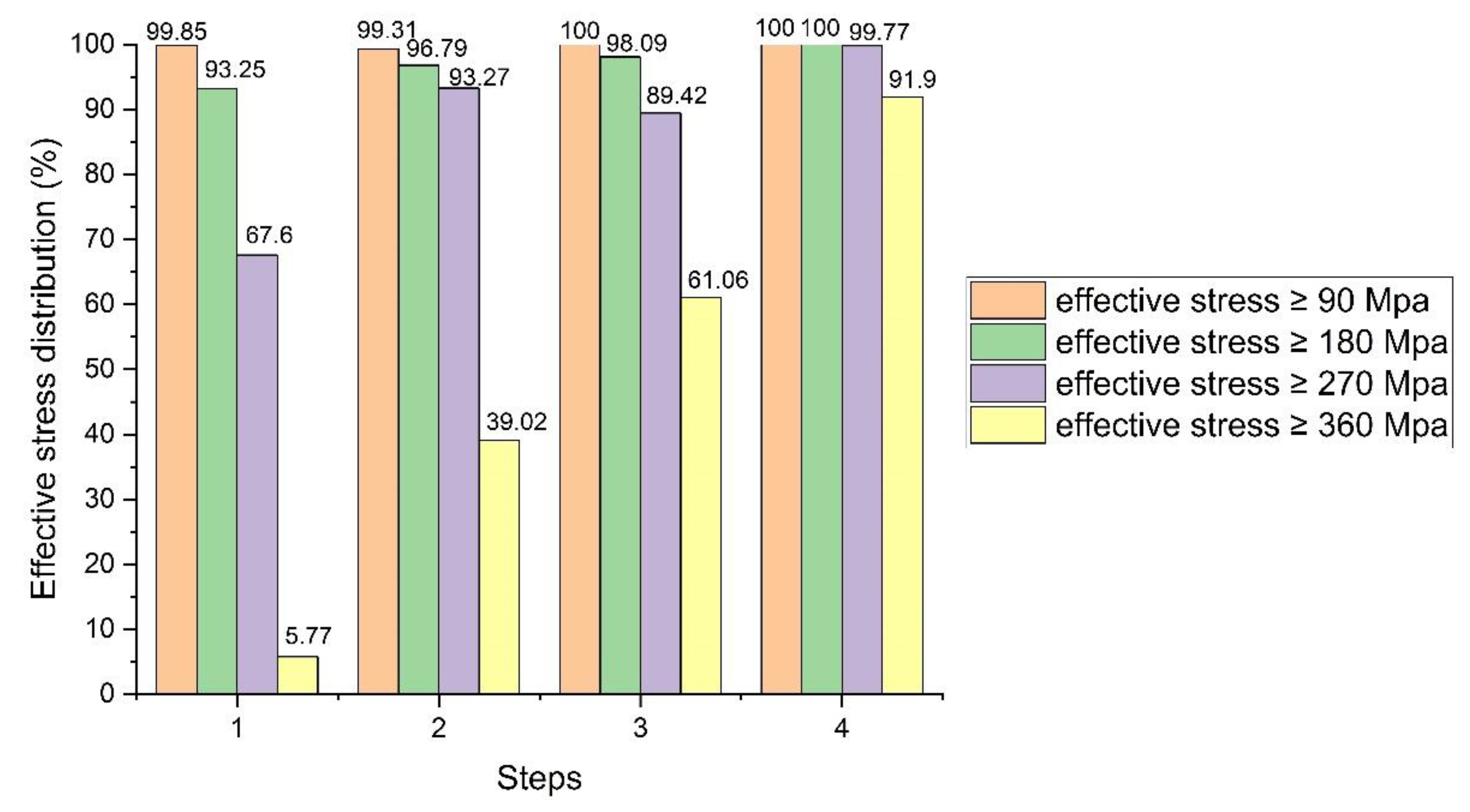

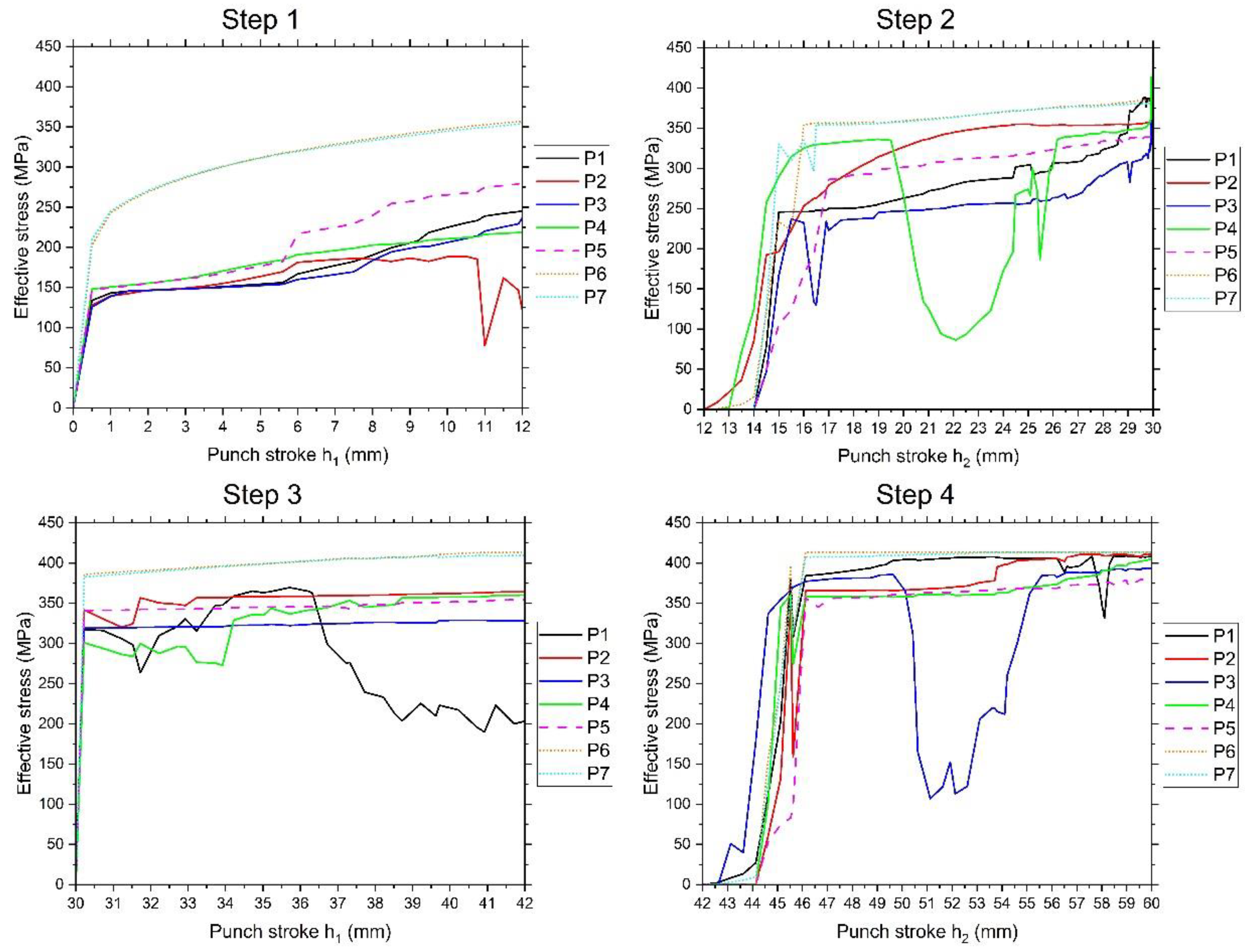

3.3. Effective Stress

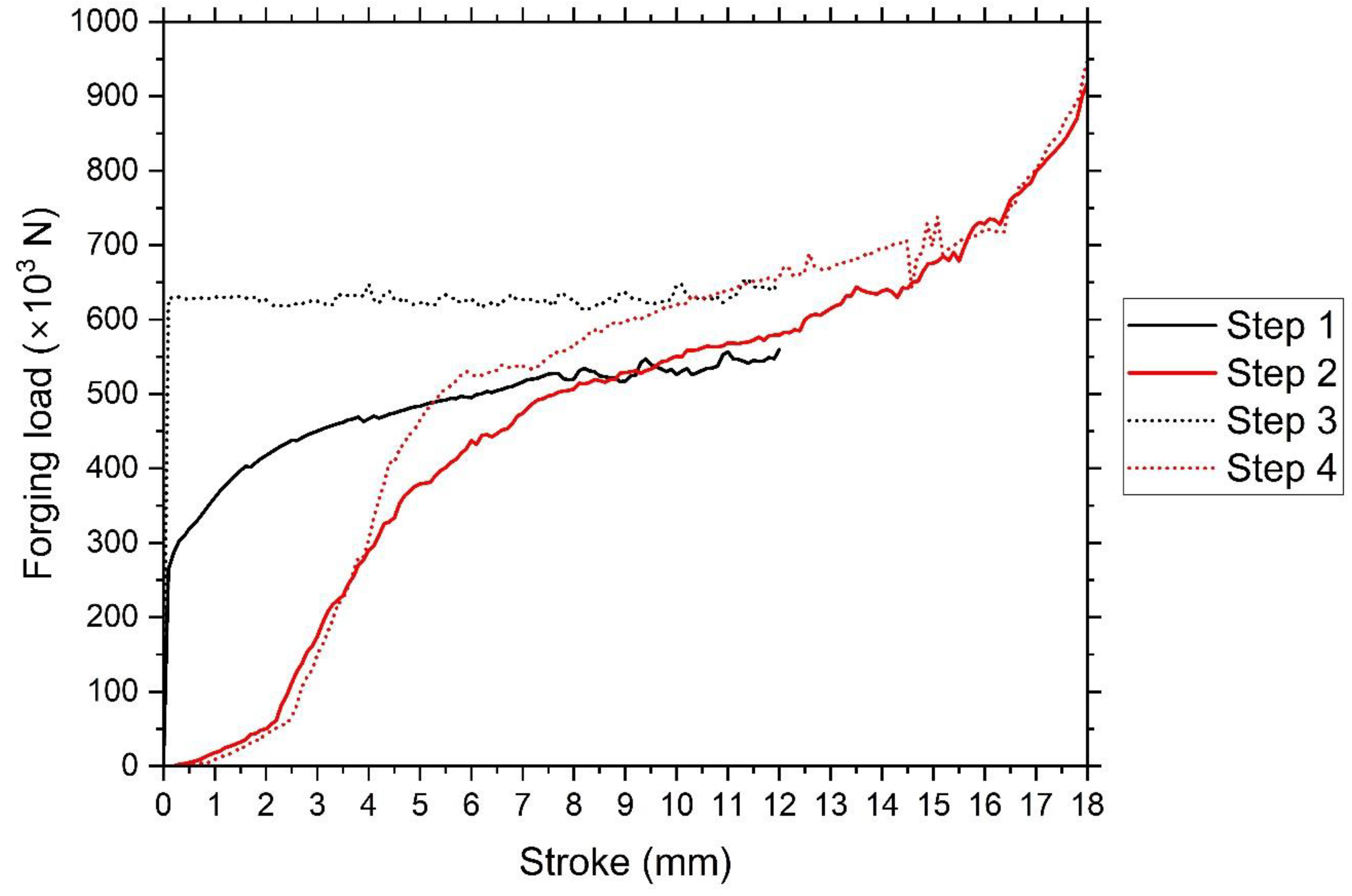

3.1. Forging Load

4. Summary and Conclusions

- (1)

- The difference in the velocities of material particles in the ACF leads to the complexity of the metal flow kinematics with the formation of diagonal and vortex flows in the deformed material. The main diagonal flows, which have the highest velocity, are formed along the diagonal of the billet, and the alternating loads of the punches cause their directions to change to the opposite with each subsequent step. The radial thrust of these diagonal flows, coupled with the frictional conditions and loading peculiarities in the ACF, creates the vortex flows that are most clearly visible in Steps 1 and 3.

- (2)

- The maximum effective strain and stress occur at two points of the billet with the container surface and at two points at the interfaces of adjacent punches. With each subsequent deformation step, the average and absolute values of strains and stresses increase, and their distribution becomes more uniform. In the final ACF step, the effective strain proportions in the material ≥ 0.5 and ≥ 1.0 are 100% and 82.14%, respectively, and the effective stress proportions ≥ 270 MPa and ≥ 360 MPa are 99.77% and 91.9%, respectively.

- (3)

- It can be argued that the use of two separate punches instead of a solid one reduces the forging load since the contact area between the punch and the billet is reduced. Theoretical peak loads are a bit below 1 MN, which means the possibility of using standard factory presses with a tonnage of more than 150 tons. Preliminary results confirm the possibility of ACF commercializing; however, before this it is necessary to conduct laboratory or factory experiments since many questions remain that deserve further research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gronostajski, Z.; Pater, Z.; Madej, L.; Gontarz, A.; Lisiecki, L.; Łukaszek-Sołek, A.; Luksza, J.; Mróz, S.; Muskalski, Z.; Muzykiewicz, W.; Pietrzyk, M.; Sliwa, R.E.; Tomczak, J.; Wiewiórowska, S.; Winiarski, G.; Zasadzinski, J.; Ziółkiewicz, S. Recent development trends in metal forming. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering 2019, 19, 898–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Peng, L.F.; Meng, B.; Xu, Z.T.; Wang, L.L.; Ngaile, G.; and Fu, M.W. Energy field assisted metal forming: Current status, challenges and prospects. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 2023, 192, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafenecker, J.; Bartels, D.; Kuball, C.-M.; Kreß, M.; Rothfelder, R.; Schmidt, M.; and Merklein, M. Hybrid process chains combining metal additive manufacturing and forming – A review. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology 2023, 46, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep Raja, C.; Ramesh, T. Influence of size effects and its key issues during microforming and its associated processes – A review. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2021, 24, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edalati, K.; Bachmaier, A.; Beloshenko, V.A.; Beygelzimer, Y.; Blank, V.D.; Botta, W.J.; Bryła, K.; Čížek, J.; Divinski, S.; Enikeev, N.A.; et al. Nanomaterials by severe plastic deformation: review of historical developments and recent advances. Materials Research Letters 2022, 10, 163–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, V. Review: Modes and Processes of Severe Plastic Deformation (SPD). Materials 2018, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pustovoytov, D.; Pesin, A.; Tandon, P. ; Asymmetric (Hot, Warm, Cold, Cryo) Rolling of Light Alloys: A Review. Metals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jiang, H.W.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y. New extrusion method for reducing load and refining grains for magnesium alloy. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017, 90, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherpour, E.; Pardis, N.; Reihanian, M.; Ebrahimi, R. An overview on severe plastic deformation: research status, techniques classification, microstructure evolution, and applications. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2019, 100, 1647–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R.Z.; Langdon, T.G. Principles of equal-channel angular pressing as a processing tool for grain refinement. Progress in Materials Science 2006, 51, 881–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beygelzimer, Y.; Varyukhin, V.; Synkov, S.; Orlov, D. Useful properties of twist extrusion. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2009, 503, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Wang, Q.; Attarilar, S. A comprehensive review of magnesium-based alloys and composites processed by cyclic extrusion compression and the related techniques. Progress in Materials Science 2023, 131, 101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, Q.; Ye, B.; Zhou, H. Enhanced microstructure homogeneity and mechanical properties of AZ31–Si composite by cyclic closed-die forging. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2013, 552, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyukov, R.R.; Imayev, R.M.; Nazarov, A.A. Production, properties and application prospects of bulk nanostructured materials. Journal of Materials Science 2008, 43, 7257–7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.; Faraji, G.; Mashhadi, M.M.; Hamdi, M. Repetitive forging (RF) using inclined punches as a new bulk severe plastic deformation method. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2012, 558, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri-Pour, M.; Parsa, M.H.; Khajezade, A.; Mirzadeh, H. Multi-Axial Incremental Forging and Shearing as a New Severe Plastic Deformation Processing Technique. Advanced Engineering Materials 2015, 17, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Tsuji, N.; Utsunomiya, H.; Sakai, T.; Hong, R. G. Ultra-fine grained bulk aluminum produced by accumulative roll-bonding (ARB) process. Scripta Materialia 1998, 39, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, F.; Lu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, B. Optimization of structural parameters for elliptical cross-section spiral equal-channel extrusion dies based on grey theory. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics 2013, 26, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Pardis, N.; Ebrahimi, R.; Talebanpour, B. A novel single pass severe plastic deformation technique: Vortex extrusion. Materials Science and Engineering A 2011, 530, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, F.; Zeng, X. Microstructural characteristics and deformation of magnesium alloy AZ31 produced by continuous variable cross-section direct extrusion. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2017, 33, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocich, R.; Macháčková, A.; Kunčická, L. Twist channel multi-angular pressing (TCMAP) as a new SPD process: Numerical and experimental study. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2014, 612, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsborhan, M.; Ebrahimi, M. Production of nanostructure copper by planar twist channel angular extrusion process. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2016, 682, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, L.S.; Lapovok, R.; Hasani, A.; Gu, C. Non-equal channel angular pressing of aluminum alloy. Scripta Materialia 2009, 61, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwei, L.; Tianmo, L.; Yong, C.; Liguang, W.; Zhongchang, W. Double change channel angular pressing of magnesium alloys AZ31. Materials and Design 2012, 35, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, M.H.; Reihanian, M.; Bagherpour, E.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Zarinejad, M.; Dean, T.A. Consolidation of Al particles through forward extrusion-equal channel angular pressing (FE-ECAP). Materials Letters 2008, 62, 3266–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.C.; Valiev, R.Z.; Li, X.; Ewing, B.R. Commercialization of bulk nanostructured metals and alloys. MRS Bulletin 2021, 46, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Politis, D.J.; Wang, L.; Lin, J. A review on forming techniques for manufacturing lightweight complex—shaped aluminium panel components. International Journal of Lightweight Materials and Manufacture 2018, 1, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J. Advanced lightweight materials for automobiles: a review. Materials & Design 2022, 221, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S-S.; Yue, X.; Li, Q.-Y.; Peng, H.-L.; Dong, B.-X.; Liu, T.-S.; Yang, H.-Y.; Fan, J; Shu, S.-L.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, Q.-C. Development and applications of aluminum alloys for aerospace industry. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 27, 944–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaohan, Y.; Zhiquan, X.; Shaowei, J.; Yao, Z.; Yuhan, L.; Huasheng, Q.; Renjie, N.; Jiahao, Y.; David, H.; Wei, C.; Yu, C. A review of research on aluminum alloy materials in structural engineering. Developments in the Built Environment 2024, 17, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, P.; Vundavilli, P.R.; Meher, A.; Mahapatra, M.M. Recent progress in aluminum metal matrix composites: A review on processing, mechanical and wear properties. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2020, 59, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirtharaj, J.; Mariappan, M. Exploring the potential uses of Aluminium Metal Matrix Composites (AMMCs) as alternatives to steel bar in Reinforced Concrete (RC) structures-A state of art review. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 80, 108085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enze, Y.; Huijie, Z.; Kang, M.; Conggang, A.; Qiuzhi, G.; Xiaoping, L. Effect of deep cryogenic treatment on microstructures and performances of aluminum alloys: a review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2023, 26, 3661–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Seet, H.L.; Liu, T.; Liao, W.; Ramamurty, U.; Ling Nai, S.M. Recent progress on the additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys and aluminum matrix composites: Microstructure, properties, and applications. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 2023, 190, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abishkenov, M.; Ashkeyev, Z.; Nogaev, K. Investigation of the shape rolling process implementing intense shear strains in special diamond passes. Materialia 2022, 26, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkeyev, Z.; Abishkenov, M.; Mashekov, S.; Kawałek, A. Stress state and power parameters during pulling workpieces through a special die with an inclined working surface. Engineering Solid Mechanics 2021, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abishkenov, M.; Ashkeyev, Z.; Nogaev, K.; Bestembek, Y.; Azimbayev, K.; Tavshanov, I. On the possibility of implementing a simple shear in the cross-section of metal materials during caliber rolling. Engineering Solid Mechanics 2023, 11, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiko, J.O.; Mwema, F.M.; Bodunrin, M.O. Finite element simulation of X20CrMoV121 steel billet forging process using the Deform 3D software. SN Applied Sciences 2019, 1, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereczki, P.; Szombathelyi, V.; Krállics, G. Determination of flow curve at large cyclic plastic strain by multiaxial forging on MaxStrain System. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2014, 84, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereczki, P.; Krallics, G.; Renkó, J. The effect of strain rate under multiple forging on the mechanical and microstructural properties. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 37, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.H.; Van Tyne, C.J. Validation via FEM and plasticine modeling of upper bound criteria of a process-induced side-surface defect in forgings. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2000, 99, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Shi, Z.; Lin, J.; Dean, T.A. An upper bound solution for deformation field analysis in differential velocity sideways extrusion using a unified stream function. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2022, 224, 107323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, S.-H.; Lin, S.-L. Application of 3D FEM-slab method to shape rolling. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2001, 43, 1155–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Jiang, H.W. Microstructural analysis and mechanical properties of AZ31 magnesium alloy prepared by alternate extrusion (AE). International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017, 92, 4293–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulagin, R.; Beygelzimer, Y.; Ivanisenko, Yu.; Mazilkin, A.; Straumal, B.; Hahn, H. Instabilities of interfaces between dissimilar metals induced by high pressure torsion. Materials Letters 2018, 222, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beygelzimer, Y.; Reshetov, A.; Synkov, S.; Prokof’eva, O.; Kulagin, R. Kinematics of metal flow during twist extrusion investigated with a new experimental method. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2009, 209, 3650–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. Comprehensive Materials Processing. Deformation Rules and Mechanism of Large-Scale Profiles Extrusion of Difficult-to-Deform Materials. Comprehensive Materials Processing 2014, 5, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Billet diameter (D) | 40 mm |

|---|---|

| Billet height (H) | 45 mm |

| Billetmaterial (type) | Al 6061-Т4 (plasticity material) |

| Tooling material type | Rigid |

| Billet temperature (T) | 20 °C (cold forging) |

| Number of elements for billet | 34,767 tetrahedron elements (6,971 nodes) |

| Forging speed (v) | 1 mm/s (for all four punches) |

| Coefficient of friction (μ) | 0.12 (shear friction factor) |

| Punch stroke (h1) Punch stroke (h2) |

12 mm (first and second punches) ~18mm (third and fourth punches) |

| Simulation type | Lagrangian incremental |

| Iteration | Direct method |

| Solver | Conjugate gradient method |

| Remeshing | Global |

| Relative interference depth | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).