1. Introduction

As the average age in Western countries is constantly increasing, so is the prevalence of edentulism and with it the request for increasingly complex prosthodontic and implant-prosthodontic solutions, which require a suitable and sufficient amount of bone in order to be performed in an optimal and predictable manner.[

1]

Following tooth extraction, bone ridge undergoes a process of remodeling that leads to its dimensional reduction.[

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] Such physiological changes in the alveolar process adversely affect the prosthodontic rehabilitation of the edentulous area, whether the patient has to be treated with implant-supported or with traditional prosthodontic procedures. Knowing that the extent of bone resorption is correlated with the degree of trauma during extraction, in recent years several studies dealing with extraction surgery focused on techniques different from traditional ones and gradually more conservative and respectful of the supporting tissues.[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]

One of the most recent minimally invasive extraction methods to have been introduced is that involving the use of the Magnetic Mallet, which is capable of generating well-calibrated and predefined electromagnetic pulses that allow the clinician to perform surgical procedures much more precisely, quickly and less traumatically for the patient than using a manual hammer and traditional chisels and levers, which, in the vast majority of cases, have been seen to result in trauma to the supporting tissues, with destruction of the surrounding bone structure. [

18,

19,

20]

In this perspective, the purpose of the present study is to clinically evaluate bucco-lingual bone resorption of the alveolar crest 3 months after extractions performed using the Magnetic Mallet®.[

21]

2. Materials and Methods

Between February 2023 and June 2023, a sample of 9 consecutive patients (6 males and 3 females), with an average age of 62 years (range: 38-73 years), underwent 29 tooth extractions using the Magnetic Mallet® and were subsequently rehabilitated with implant-supported partial fixed prostheses with delayed loading at the Division of Prosthodontics and Implant Prosthodontics, Department of Surgical Sciences (DISC), of the University of Genova. A diagnosis of the dental elements to be extracted was performed with clinical examination and radiographs. All patients were accurately informed about the expected operative procedures and the research protocol and provided a signed informed consent before being included in the experimental protocol. The project was approved by the local Ethical Committee (approval n. 2023/68).

The extractions were performed by two operators of equal clinical experience.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients referring to the Division of Prosthodontics and Implant Prosthodontics were included in this research protocol if they matched the following inclusion criteria:

good systemic health without any contraindications to oral surgery and subsequent prosthetic rehabilitations planned;

presence of at least one severely compromised dental element to be extracted;

willingness to participate to the study protocol, attend the planned appointments and follow the instructions given by the clinicians.

Mobility 0 or I degree

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were:

Patients with systemic diseases representing a contraindication to oral surgery;

Irradiation of the head/neck region within 12 months prior to surgery;

Pregnancy or breast-feeding;

Poor oral hygiene and lack of motivation to return for checkups.

2.3. Patient Evaluation

Anamnestic data (biographical data, near and remote pathological history) were carefully collected. Clinical and radiographic examinations were conducted, in order to assess the health condition of the oral cavity and if one or more elements were assessed as unrecoverable the patient was included in the research.

Once the diagnosis was made, an appointment was scheduled for a professional oral hygiene section and then the extraction of the hopeless elements was scheduled.

The following data were assessed:

level of oral hygiene, assessed on the basis of the plaque index

location of the dental element(s) to be extracted;

presence of hard lamina as evaluated through endoral x-ray;

cause of extraction: caries, orthodontic reasons, trauma;

mobility of degree 0, I at the time of extraction;

Occlusal and lateral endoral pictures of the elements to be extracted were taken before starting the surgery session (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1, 2.

Occlusal and lateral view of one of the dental element to be extracted (16).

Figure 1, 2.

Occlusal and lateral view of one of the dental element to be extracted (16).

A pre-operative sectoral cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) was taken in order to 3-dimensionally assess root conformation (to avoid possible complications during extraction) and in order to measure the thickness of bone crest at time 0 (extraction time). A second CBCT was taken 3 months post-extraction to evaluate the buccal-palatal/lingual bone resorption. Bucco-lingual bone resorption was measured as the difference between bone crest thickness recorded at T0 and bone crest thickness at T3M using adjacent teeth as reference point.

2.4. Surgical Procedure, Evaluation at Follow-Up, and Collection of Radiographic Data

Before extraction the patient was instructed to rinse with a 0.2% chlorexidine solution for 1 minute. Then local anesthesia was administered using the most appropriate technique to control the pain of the affected element: in the case of plexic anesthesia, a vial of Optocain® Mepivacaine with adrenaline 1:100˙000 was used, while in the case of truncular anesthesia, Scandonest® 3% without vasoconstrictor was used, followed then by further plexic anesthesia at the level of the affected tooth. An oral rinse with a 0.2% chlorhexidine solution was, thereafter, had the patient performed.

After that, the Magnetic Mallet was prepared on the work surface, which consists of a handpiece, which is activated by an electronic power supply that can control forces and timing of application, on which specific instruments and inserts can be mounted to perform the desired work. The handpiece transmits a magnetic wave to the insert, which generates a shock wave that is calibrated with respect to force application times and induces axial movements at the tip of the insert itself.

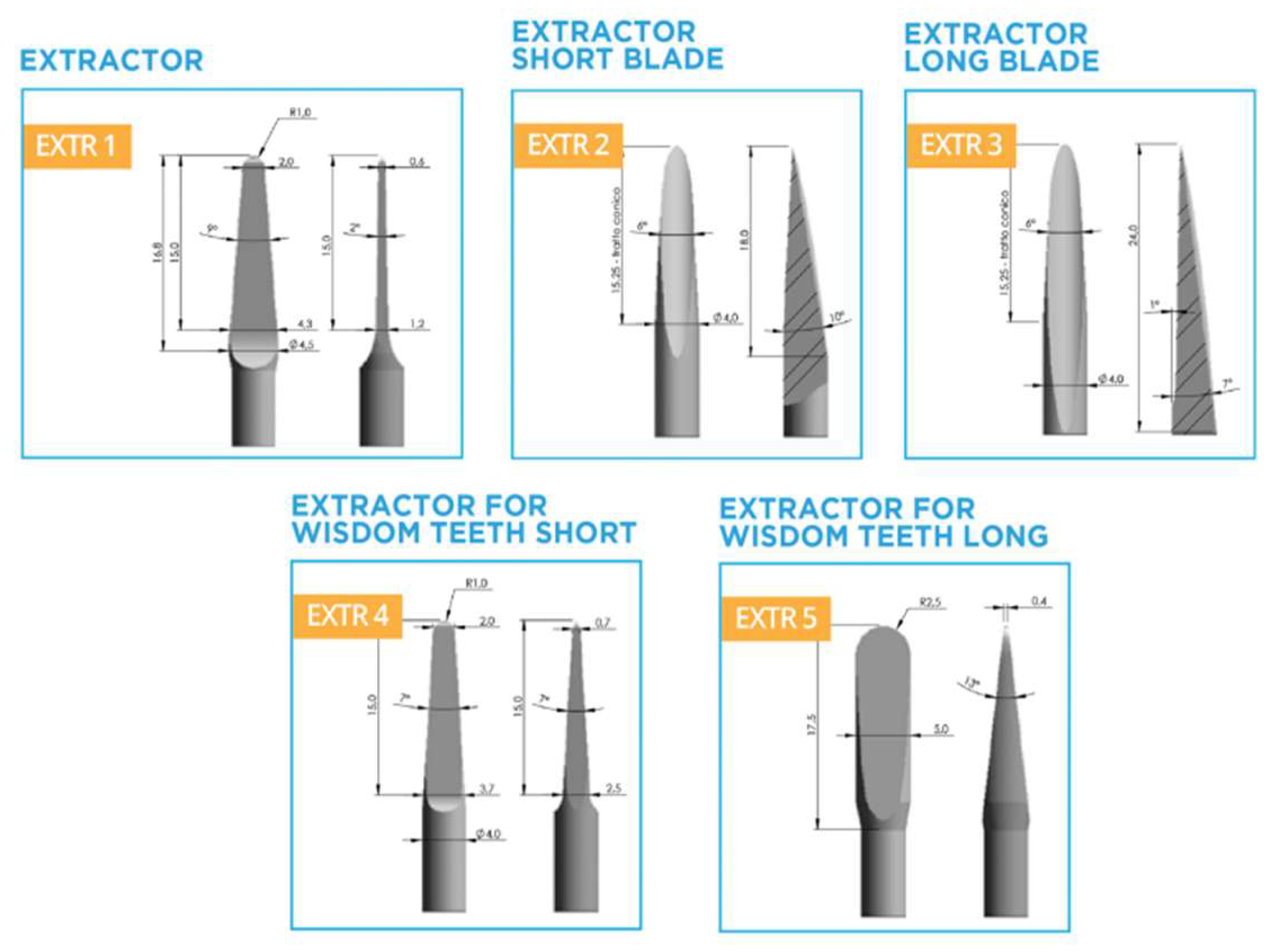

Once the Magnetic Mallet was prepared on the work surface, the next step was to choose the most suitable extraction insert to be mounted on the handpiece. The extraction kit offers a set of 5 inserts, both straight and curved ones for better access to the posterior regions, for a total of 10 instruments: for each extraction, it was evaluated which among them offered the best morphology to perform the surgical maneuvers in relation to the dental anatomy.

The Magnetic Mallet provides 4 different force settings, the intensity of which varies from a minimum of 1, to a maximum of 4. Having set the lowest power (equal to one) via the ferrule selector, the insert was inserted parallel to the long axis of the tooth within the gingival sulcus and the Magnetic Mallet was activated via the foot pedal connected to the instrument. The objective was to induce dislocation of the periodontal ligament fibers circumferentially along the entire circumference of the root of the tooth element.

During activation of the unit, the insert, moving rapidly and longitudinally on a constant 1.1-mm stroke between the root surface and the hard lamina of the alveolus, advanced easily with minimal hand pressure, achieving much faster and less strenuous results than conventional periotomes.

In the case of single-rooted elements, the most suitable extraction insert was mounted on the handpiece until the tooth was completely dislocated and avulsed. In the case of multi-rooted elements, the roots were always separated using drills to make the element as single-rooted and then proceed in the same as for single-rooted elements, in order to avoid the risk of bone or dental fractures (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Surgical sectioning of roots.

Figure 3.

Surgical sectioning of roots.

The extractions were carried out through the action of the mallet only, pliers were used only when needed, only during the final phase of the extraction in order to catch the tooth once it has been completely detached using the magnetodynamic device.

Once the operation was completed, the mobility of the tooth was assessed using the handle of a mirror and a metal tweezer. In cases where mobility was shown to be grade 0 or 1, the circumferential dislocation operation was repeated at a higher level of intensity.

Once a sufficient level of mobility was achieved, the tooth elements were removed from their socket only by the action of the Mallet, using the tip of the insert as a lever (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 4, 5, 6, 7.

Root extraction using the Magnetic Mallet®.

Figure 4, 5, 6, 7.

Root extraction using the Magnetic Mallet®.

After extraction a manual alveolar debridement was performed and a 4-0 silk suture was placed.

Ice was applied and patients were instructed to follow the usual post-extraction home procedures:

icepack in the surgical area for 6 hours after surgery, alternating 30 minutes with and 30 minutes off;

administrations of 875 mg amoxicillin + 125 mg clavulanic acid every 8 hours for 5 days;

fresh, soft diet for the first 24 hrs;

no rinsing during the first 24 hours;

normal home oral hygiene procedures the day after surgery and rinsing with mouthwash with 0.12% chlorhexidine twice a day for 2 weeks.

All the extractions were carried on by two expert surgeons. At the end of the surgical procedure, the following information was recorded for each patient:

- -

maximum intensity value selected during dislocation (from 1 to 4);

- -

use of Magnetic Mallet inserts only and code of the insert(s) used;

- -

use of Magnetic Mallet inserts and extraction pliers only;

- -

use of inserts, pliers, and hand levers;

- -

time of the extraction considered between the end of anesthesia and the avulsion of the element;

- -

measurement in mm of the depth of insertion of the instrument into the gingival sulcus;

- -

whether inserts were used as levers;

- -

indicative percentage of dislocation obtained with the Mallet only;

- -

assessment of the heating of the handpiece during use;

- -

indicative frequency of blows administered;

- -

positioning of the insert;

- -

approximation of instrument entry angle with respect to the root;

- -

type of noise during instrument use;

The patient was reobserved after 1 week/10 days to assess the healing progress and remove any sutures.

Regarding radiographic investigations, sectional CBCTs were performed to measure the thickness of the bone ridge at time 0 (extraction time) and at 3 months in order to assess vestibulo-palatal/lingual bone resorption.

For statistical analysis, a two-sample t-test was performed between measurements taken at time T0 and those taken at 3 months (T3M) in the 29 tooth elements.

The same test was repeated for comparison of the two operators that performed the extractions.

3. Results

A sample consisting of 9 patients (6 males and 3 females), with an average age of 62 years (38-73), were recruited between February 2023 and June 2023, from whom 29 dental elements were extracted, of which 25 were single-rooted and 4 were multi-rooted.

Out of 9 patients, 2 were smokers.

The level of oral hygiene was rated as "good" for 4 patients, "sufficient" for 1 patient and "poor" for 4 patients (of whom 2 were smokers).

A total of 3 molars, 3 premolars, 3 canines and 20 incisors were removed.

Three elements, belonging to 3 patients, were extracted for trauma, while the remaining 26 , were removed for the presence of destructive carious lesions.

Twenty-two extractions were performed in the upper jaw and 7 in the lower jaw.

Preoperative evaluation of the mobility of the dental elements was performed.

17 teeth (including 2 multi-rooted) showed a mobility grade of 0, 12 teeth (including 2 multi-rooted and 5 located in the lower jaw) a mobility grade of 1.

Based on the radiographic examination, it was possible to examine the presence of the lamina dura.

In the course of the extraction procedure, surgical separation of the roots into a single tooth element, whose root morphology would have made the use of the Magnetic Mallet difficult.

Regarding the clinical data on the use of the instrument, it was observed that the maximum level of force used to extract the tooth was equal to 1 in 2 cases (1 monoradiculated and 1 pluriradiculated), equal to 2 in 20 cases (all monoradiculated, equal to 3 in 7 cases (4 monoradiculated and 3 pluriradiculated, while there were no cases in which it was necessary to use an instrument force level equal to 4.

During the surgical procedure, different types of extraction inserts were used: specifically, in 1 case only (and, more specifically, in the only tooth element to which roots were separated, having mobility degree of 0) the EXTR3 insert was used, in 15 teeth (13 single-rooted and 2 multi-rooted), the EXTR2F insert was used, in 11 teeth (all single-rooted) the use of EXTR3F insert was employed, in 1 tooth element (multi-rooted) the angled EXTR3F insert was used and in 1 tooth (single-rooted) the EXTR4F insert was used (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

different types of inserts used for extraction.

Figure 8.

different types of inserts used for extraction.

The use of these inserts, the tip of which was used as a lever in all dental elements, allowed for complete dislocation of each tooth without the use of forceps and hand levers.

During the dislocation maneuvers, the insert was placed mesial, palatal/lingual and distal to each element and used parallel to the root. The average depth achieved by the instrument in the socket was 4 mm, ranging from 3 mm (in 3 single-rooted teeth) to 6 mm (in 1 single-rooted tooth).

The average frequency of blows administered to achieve avulsion of the tooth elements was approximately 7 blows (6.6), in a range between 2 (in a lower lateral incisor with initial mobility degree of 1) and 12 (in an upper canine with initial mobility degree of 0), while the average time taken to extract each tooth calculated from the beginning of instrument use, was 3 1/2 minutes, ranging from 2 minutes (for 12 teeth of which one was multi-rooted, with a degree of mobility equal to 0 in 5 cases, equal to 1 in 7 cases) to 7 minutes (in a single-rooted element with a degree of mobility equal to 0).

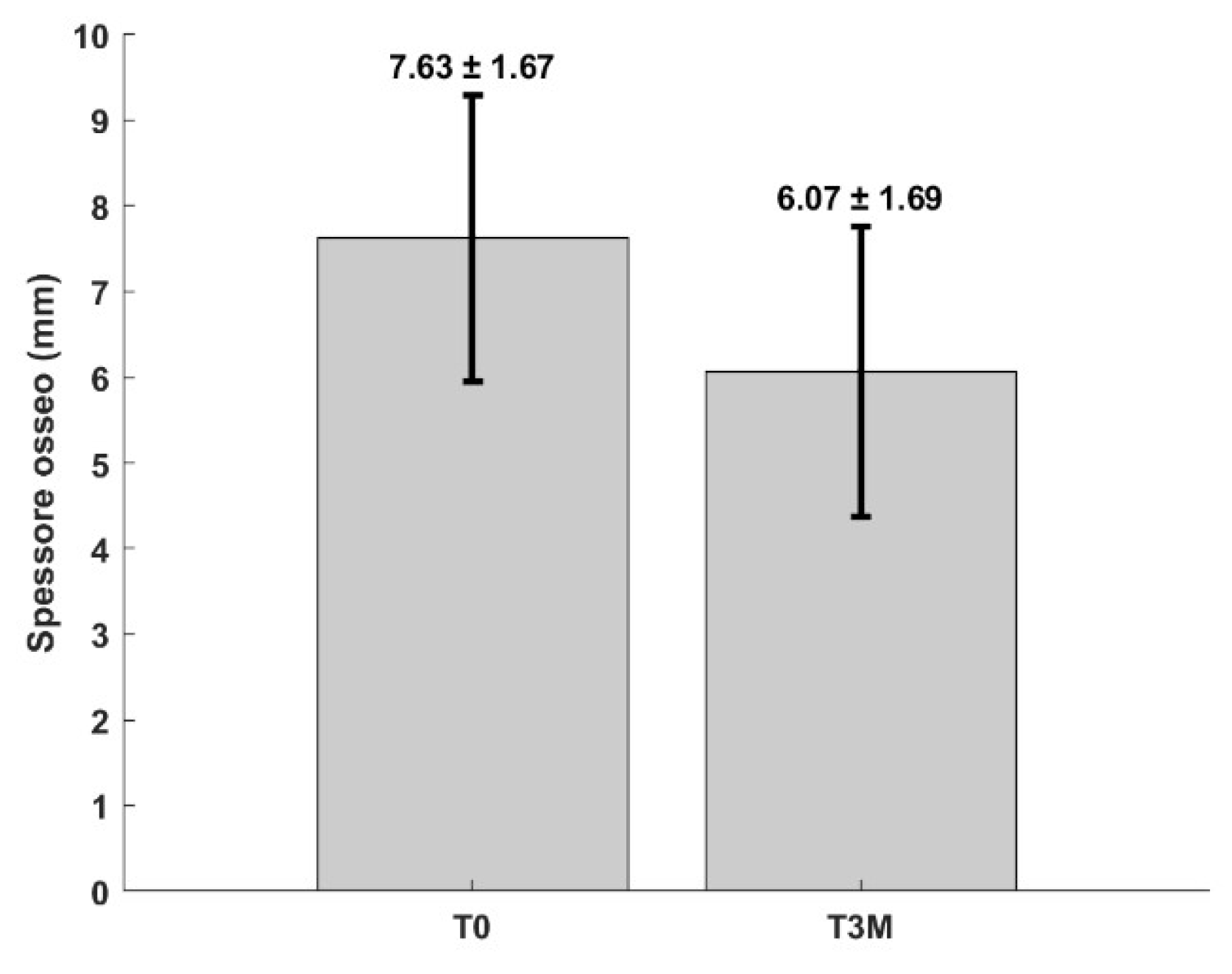

Regarding the measurements concerning the alveolar ridge, the bone thickness at time 0 and 3 months after the extractions were calculated by means of sectorial CBCT in order to go and evaluate the vestibulo-palatal/lingual bone resorption at 4 months after the dental avulsions, the average of which was 1.56 mm, ranging from 0.7 mm to 2.7 mm. The minimum resorption occurred at the level of an 11 (thus at the level of a monoradiculate element located in the upper jaw) belonging to a nonsmoking patient presenting poor hygiene, with a degree of mobility equal to 1, who was extracted in 2 minutes, using an instrument force level equal to 1 and a number of strokes equal to 3, while the maximum peak of bone ridge thickness reduction was observed at the level of a 23 (thus again at the level of a single-rooted tooth placed in the upper jaw), also belonging to the same patient, with a degree of mobility equal to 1, removed in 5 minutes, using a force level equal to 2 and a number of strokes equal to 10.

Bone ridge thickness was measured from the most buccal to the most lingual point at 2 mm apical to the crestal margin, as approximate allowance was made for the reduction even in height of the alveolar ridge that may occur during the 3 months following extraction.

For statistical analysis, a two-sample t-test was performed between measurements taken at time T0 and those taken at 3 months (T3M) in the 29 tooth elements. The difference between the samples is significant with an alpha significance level of 0.01.

Figure 9 shows mean and standard deviation of bone thickness at T0 and T3.

Figure 9.

Mean and standard deviation of bone thickness at T0 and at T3M.

Figure 9.

Mean and standard deviation of bone thickness at T0 and at T3M.

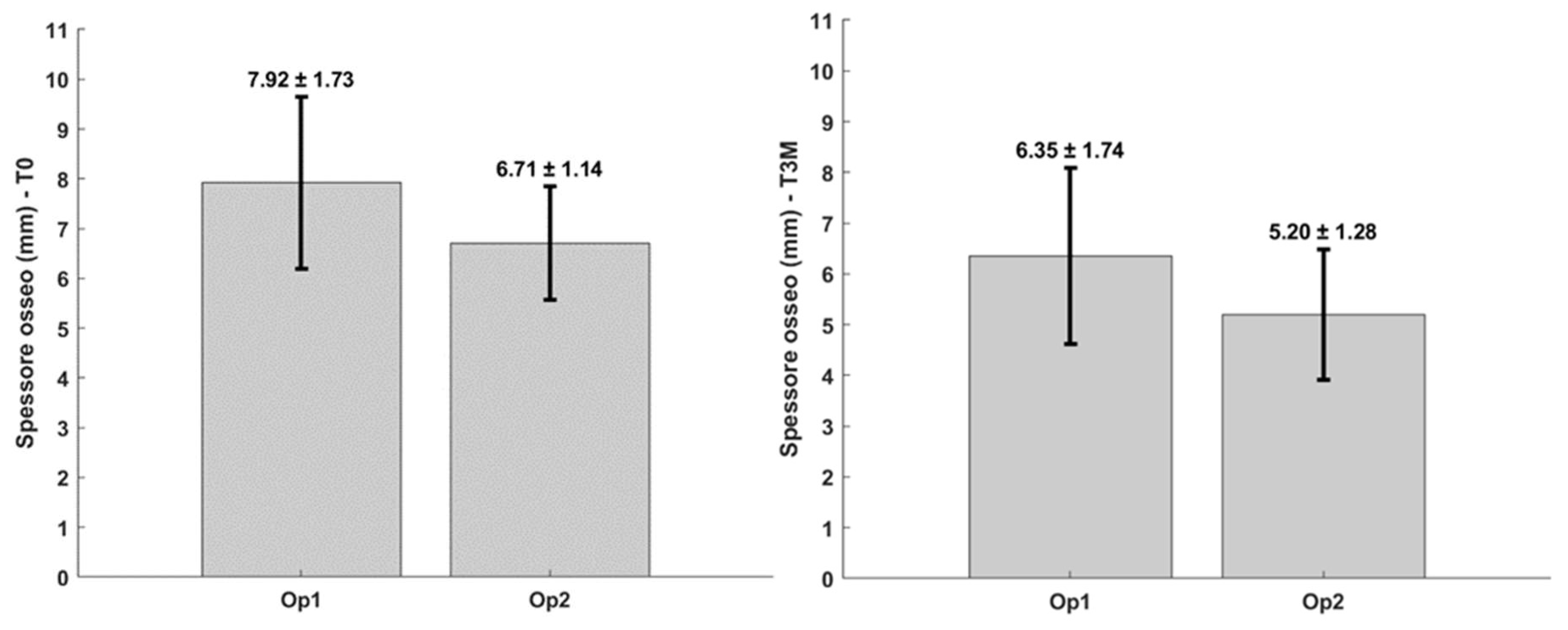

The same test was repeated for comparison of the two operators that performed the extractions. Surgeon 1 extracted 15 teeth, while surgeon 2 extracted 14 teeth. The figures below show mean and standard deviation of bone thickness. No statistically significant difference was found with a significance level of 0.01 at time T0, nor at time T3M (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Comparison of the two operators. Mean and standard deviation of bone thickness at time T0 and time T3M.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the two operators. Mean and standard deviation of bone thickness at time T0 and time T3M.

4. Discussion

A total of 29 dental elements were extracted, due to the presence of destructive caries.

Seven extractions were performed at the level of the lower jaw, which is more rigid and compact with a harder bone theca.

Of the 29 extracted teeth, 4 were multi-rooted and 25 were single rooted.

One of the advantages of the Magnetic Mallet is that it allows a much more constant and greater force to be applied than manual hammers. The magnetic-dynamic device, on the other hand, provides 4 different intensity settings, from 1 to 4, corresponding to 65, 85, 120 and 260 kg, respectively.

The average degree of force used for the extractions in this study was 2. In no case was level 4 used, while grade 3 was used for the removal of all 4 molars, underscoring that it is usually more difficult to extract this type of element.

Whether there is a correlation between the degree of force used and bone density has not been investigated, but it would be interesting to address this topic in future studies.

As regards the frequency of blows administered, the lowest number of blows occurred at the level of a lower lateral incisor with a degree of mobility equal to 1, while the maximum frequency of blows was found in an upper canine with a degree of mobility equal to 0. This is consistent with the fact that the canine has the largest root at the level of the maxilla. In fact, a rather large number of shots were also used to remove the contralateral canine.

On the other hand, it should be noted that in the elements without hard lamina the frequency of the number of blows was lower than the average, as was also the time taken to perform the extractions, which was, however, higher at the level of the 3 molars and the 3 canines, or in the teeth where the avulsion maneuvers can actually prove to be a little more investigative. The minimum value of time was found in the extractions of both upper and lower central and lateral incisors and first premolars; however, it should be emphasized that, unlike what has been said before, the maximum peak also occurred at the level of an anterior element, in particular, in an upper lateral incisor which had an initial degree of mobility equal to 0. In fact, it can be noted how the number of blows administered and the degree of force used in this tooth were rather high (8 blows, degree of force equal to 3).

With regard to bone resorption 3 months after extractions, the focal point of the study, the teeth that presented a greater contraction of the alveolar ridge in the vestibulo-palatal/lingual direction were the two upper canines and a lateral incisor, also upper, all belonging to the same non-smoker patient, for which the extractions required more than the average time, i.e. 5 minutes, and it was also necessary to use a high number of strokes (12 strokes for the right canine and 10 strokes for the lateral incisor right and left canine). This confirms the fact that there is a correlation between the extent of resorption and the degree of trauma that occurs during the intraoperative phase.

The percentage of teeth with greater than average bone resorption (1.56 mm) was higher in the mandible (71%) than in the maxilla (32%). This could suggest that there is also a correlation with the different bone types between maxilla and mandible.

The results obtained in this research were compared with data from previous works.

In 2003, Schropp et al.[

22] observed a reduction in bone crest width of approximately 30% 3 months after extraction. It has been calculated that the average resorption obtained in this study corresponds, however, to approximately 20%. Indeed, if the width of the crest had been reduced by approximately 30%, the observed bone resorption would not have been 1.56 mm, but 2.29 mm. From this first analysis, therefore, it can be seen that the use of the Magnetic Mallet in extraction procedures actually brings benefits as regards a minor reduction in the vestibulo-palatal/lingual dimension of the alveolar process.

Over the years, numerous clinical studies have been performed regarding the use of grafting materials and mechanical barriers in post-extraction sockets in order to prevent the contraction of the alveolar ridge that occurs following tooth extraction.

Analyzing the following data, we note how the use of some types of biomaterials resulted in less bone resorption.[

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. In other cases, however, the use of grafting materials has led to similar, if not worse, results than those obtained in the present study. Cardaropoli & Cardaropoli[

29], for example, observed a change in the width of the bone crest at 4 months of 1.85 mm following the use of bovine bone mineral, a reduction therefore greater than that found in our analysis, as well as Kutkut et al [

30] who, using calcium sulphate hemihydrate and platelet-rich plasma, obtained a resorption of 1.7 mm after 3 months and Clozza et al[

31] who, again at 3 months, found bone loss buccally-palatal/lingually by 1.8 mm after using bioactive glass. In the study by Neiva et al[

32], whose aim was to evaluate the matrix of hydroxyapatite combining with the synthetic P-15 cell-binding peptide, the change in bone thickness at 16 weeks was 1.31 mm, value similar to that of our research, as well as that obtained by Shakibaie-M24 at 12-14 weeks in the second test group using hydroxidelapatite and silicon dioxide (1.5 mm) and to that detected by Toloue et al. [

33] at 3 months using calcium sulphate (1.33 mm). Also the resorption observed by Cook & Mealey 34 at 21 weeks in test group 1 following the use of a bovine xenogenic graft is very similar to ours (1.57 mm).

It is important to note, however, that in most of the control groups in which only extractions were performed without the use of biomaterials, the reduction of the bucco-palatal/lingual dimension of the bone crest was significantly higher than that found in this study, reaching values ≥ 2 mm.

We can therefore state that the use of the Magnetic Mallet to perform dental extractions allows for less bone resorption to be obtained even without the necessity to use biomaterials that counteract the contraction of the alveolar ridge. This outcome can be partially explained by the outcomes of a biomolecular and histologycal study on minipigs about bone healing using Magnetic Mallet in implant placement.[

35] The study found that implant sites prepared with the mallet presented a significant increase in newly formed bone, osteoblast number, and a smaller quantity of fibrous tissue, together with significant BMP-4 augmentation and a positive trend in other osteogenic factors. The study concluded that the mallet is able to induce osseocondensation and improve newly formed bone during implant site preparation.

Saldanha et al. [

36], in a 6-month prospective study, showed that smoking can lead to greater bone size reduction, stating that it is possible to have an additional 0.5 mm crest bone decrease after tooth extraction in smokers compared to non-smokers. In the present study, only two patients were smokers, who, however, did not show higher bone resorption than non-smokers. It would be interesting to extend the study follow-up in order to evaluate bone behaviour over time.

Finally, no statistically significant difference was found between the two operators involved in the study. This suggests that the use of the Magnetic mallet for tooth extraction requires a short learning curve and, consequently, can be easily used by both expert operators and less experienced clinicians.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study showed that the use of the Magnetic Mallet during extraction procedures promoted less resorption of the bucco-lingual dimension of the bone ridge in the 3 months following dental extractions, compared with the use of manual hammers and traditional chisels and levers. It was also observed that, in some cases, the extent of this resorption was less even than the reduction in bone thickness found in previous studies in which different types of biomaterials were used with the aim of preserving the socket. This suggests that when the magnetodynamic device is used, the use of such graft materials can be limited, although it would be interesting to undertake new combined studies in which the action of the Magnetic Mallet is evaluated in conjunction with the use of a filler material to be applied in the alveolus, to see if less bone resorption can be achieved.

In conclusion, we can consider the use of the Magnetic Mallet as a viable alternative to the well-established minimally invasive extraction techniques that can make extractions faster, atraumatic and effective, thus leading to minimal or no use of bone grafts.

However, further investigations, including a greater sample of patients and a longer follow-up, are needed in order to deepen the knowledge on the use of the Magnetic Mallet and on the possible variables affecting the clinical outcomes, in order to develop standardized protocols for its use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B., F.G., F.B. and J.C.; methodology, D.B.; software, A.T.L.; validation, D.B. and M.M.; formal analysis, F.G.; investigation, D.B. and J.C.; resources, D.B., and J.C..; data curation, F.G. and A.T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.G. and J.C.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and L.D.G.; visualization, F.B. F.B.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are available upon requests to corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Polzer, I.; Schimmel, M.; Müller, F.; Biffar, R. Edentulism as part of the general health problems of elderly adults. Int Dent J. 2010, 60, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van der Weijden, F.; Dell’Acqua, F.; Slot, D.E. Alveolar bone dimensional changes of post-extraction sockets in humans: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2009, 36, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombelli, L.; Farina, R.; Marzola, A.; Bozzi, L.; Liljenberg, B.; Lindhe, J. Modeling and remodeling of human extraction sockets. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardaropoli, G.; Araújo, M.; Lindhe, J. Dynamics of bone tissue formation in tooth extraction sites. An experimental study in dogs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003, 30, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.G.; Lindhe, J. Dimensional ridge alterations following tooth extraction. An experimental study in the dog. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, M.G.; Silva, C.O.; Misawa, M.; Sukekava, F. Alveolar socket healing: what can we learn? Periodontol 2000 2015, 68, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashman, A. Postextraction Ridge Preservation Using a Synthetic Alloplast. Implant. Dent. 2000, 9, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.G.; Lindhe, J. Socket grafting with the use of autologous bone: an experimental study in the dog. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2011, 22, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Heggeler, J.M.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A. Effect of socket preservation therapies following tooth extraction in non-molar regions in humans: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2011, 22, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoletti, F.; Matesanz, P.; Rodrigo, D.; Figuero, E.; Martin, C.; Sanz, M. Surgical protocols for ridge preservation after tooth extraction. A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 23, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atieh M A, Alsabeeha N H, Payne A G, Duncan W, Faggion C M, Esposito M. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: alveolar ridge preservation techniques for dental implant site development. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015.

- Jung, R.E.; Philipp, A.; Annen, B.M.; Signorelli, L.; Thoma, D.S.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Attin, T.; Schmidlin, P. Radiographic evaluation of different techniques for ridge preservation after tooth extraction: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerle, C.H.; Araujo, M.G.; Simion, M. Evidence-based knowledge on the biology and treatment of extraction sockets. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012, 23, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalsi, A.S.; Kalsi, J.S.; Bassi, S. Alveolar ridge preservation: why, when and how. British Dental Journal 2019, 227, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, A.; Mardas, N.; Mezzomo, L.A.; Needleman, I.G.; Donos, N. Alveolar ridge preservation. A systematic review. Clin Oral Investig 2013, 17, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, D.; Colombo, J.; Motta, F.; Motta, F.M.; Zillio, A.; Scotti, N. Digital vs. Freehand Anterior Single-Tooth Implant Restoration. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, 4012127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldi, D.; Colombo, J.; Stacchi, C.; Robiony, M.; Schierano, G. Small diameter and immediate loading implantology: A minimally invasive technique. Dental Cadmos 2020, 88, 518–525. [Google Scholar]

- Crespi, R.; Capparè, P.; Gherlone, E. Electrical Mallet Provides Essential Advantages in Maxillary Bone Condensing. A Prospective Clinical Study. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2013, 15, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennardo, F.; Barone, S.; Vocaturo, C.; Nucci, L.; Antonelli, A.; Giudice, A. Usefulness of Magnetic Mallet in Oral Surgery and Implantology: A Systematic Review. J Pers Med. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennardo, F.; Barone, S.; Vocaturo, C.; Gheorghe, D.N.; Cosentini, G.; Antonelli, A.; Giudice, A. Comparison between Magneto-Dynamic, Piezoelectric and conventional surgery for dental extractions: a pilot study. Dent J 2023, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.G.; Silva, C.O.; Misawa, M.; Sukekava, F. Alveolar socket healing: What can we learn? Periodontology 2000, 68, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schropp, L.; Wenzel, A.; Kostopoulos, L.; Karring, T. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: A clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2003, 23, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thalmair, T.; Fickl, S.; Schneider, D.; Hinze, M.; Wachtel, H.J. Dimensional alterations of extraction sites after different alveolar ridge preservation techniques - a volumetric study. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.G.; da Silva, J.C.C.; de Mendonça, A.F.; Lindhe, J. Ridge alterations following grafting of fresh extraction sockets in man. A randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Yun, P.-Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-G. Ridge Preservation of the Molar Extraction Socket Using Collagen Sponge and Xenogeneic Bone Grafts. Implant. Dent. 2011, 20, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakibaie-M, B. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Two Different Bone Substitute Materials for Socket Preservation After Tooth Extraction: A Controlled Clinical Study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2013, 33, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardaropoli, D.; Tamagnone, L.; Roffredo, A.; Gaveglio, L.; Cardaropoli, G. Socket preservation using bovine bone mineral and collagen membrane: A randomized controlled clinical trial with histologic analysis. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2012, 32, 421–430. [Google Scholar]

- Ayham Arab Oghli, Helmut StevelingRidge preservation following tooth extraction: a comparison between atraumatic extraction and socket seal surgery. Quintessence Int 2010, 41, 605–609.

- Preservation of the postextraction alveolar ridge: a clinical and histologic study.

- Cardaropoli, D.; Cardaropoli, G. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2008 Oct;28(5):469-77.

- Kutkut, A.; Andreana, S.; Kim, H.; Monaco, E. Extraction Socket Preservation Graft Before Implant Placement With Calcium Sulfate Hemihydrate and Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Clinical and Histomorphometric Study in Humans. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clozza, E.; Biasotto, M.; Cavalli, F.; Moimas, L.; Di Lenarda, R. Three-dimensional evaluation of bone changes following ridge preservation procedures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2012, 27, 770–775. [Google Scholar]

- Neiva, R.F.; Tsao, Y.; Eber, R.; Shotwell, J.; Billy, E.; Wang, H. Effects of a Putty-Form Hydroxyapatite Matrix Combined With the Synthetic Cell-Binding Peptide P-15 on Alveolar Ridge Preservation. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toloue, S.M.; Chesnoiu-Matei, I.; Blanchard, S.B. A clinical and histomorphometric study of calcium sulfate compared with freeze-dried bone allograft for alveolar ridge preservation. J Periodontol. 2012, 83, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.C.; Mealey, B.L. Histologic Comparison of Healing Following Tooth Extraction With Ridge Preservation Using Two Different Xenograft Protocols. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schierano, G.; Baldi, D.; Peirone, B.; von Degerfeld, M.M.; Navone, R.; Bragoni, A.; Colombo, J.; Autelli, R.; Muzio, G. Biomolecular, Histological, Clinical, and Radiological Analyses of Dental Implant Bone Sites Prepared Using Magnetic Mallet Technology: A Pilot Study in Animals. Materials 2021, 14, 6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, J.B.; Casati, M.Z.; Neto, F.H.; Sallum, E.A.; Nociti, F.H., Jr. Smoking may affect the alveolar process dimensions and radiographic bone density in maxillary extraction sites: a prospective study in humans. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006, 64, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).