Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

25 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Landowners and GAP Status

2.3. Existing Vegetation Types (2020 Update)

2.4. Mature and Old-growth Forests (MOG)

2.5. Focal Species

2.5.1. Wolverine

2.5.2. Canada Lynx, Northern Goshawk, and Mexican Spotted Owl

2.6. Wildland-Urban Interface/Intermix (WUI), Wildfires, and Forest Thinning

2.7. Downscaled Climate Projections

3. Results

3.1. Landownerships and Gap Status

3.2. Existing Vegetation Types Representation Analysis

3.3. Mature and Old-Growth Forest Representation Analysis

3.4. Focal Species Distributions and GAP status

3.4.1. Wolverine

3.4.2. Mexican Spotted Owl and Northern Goshawk Representation Analysis

3.4.3. Canada Lynx Representation Analysis

3.5. WUI, Wildfires, and Forest Thinning

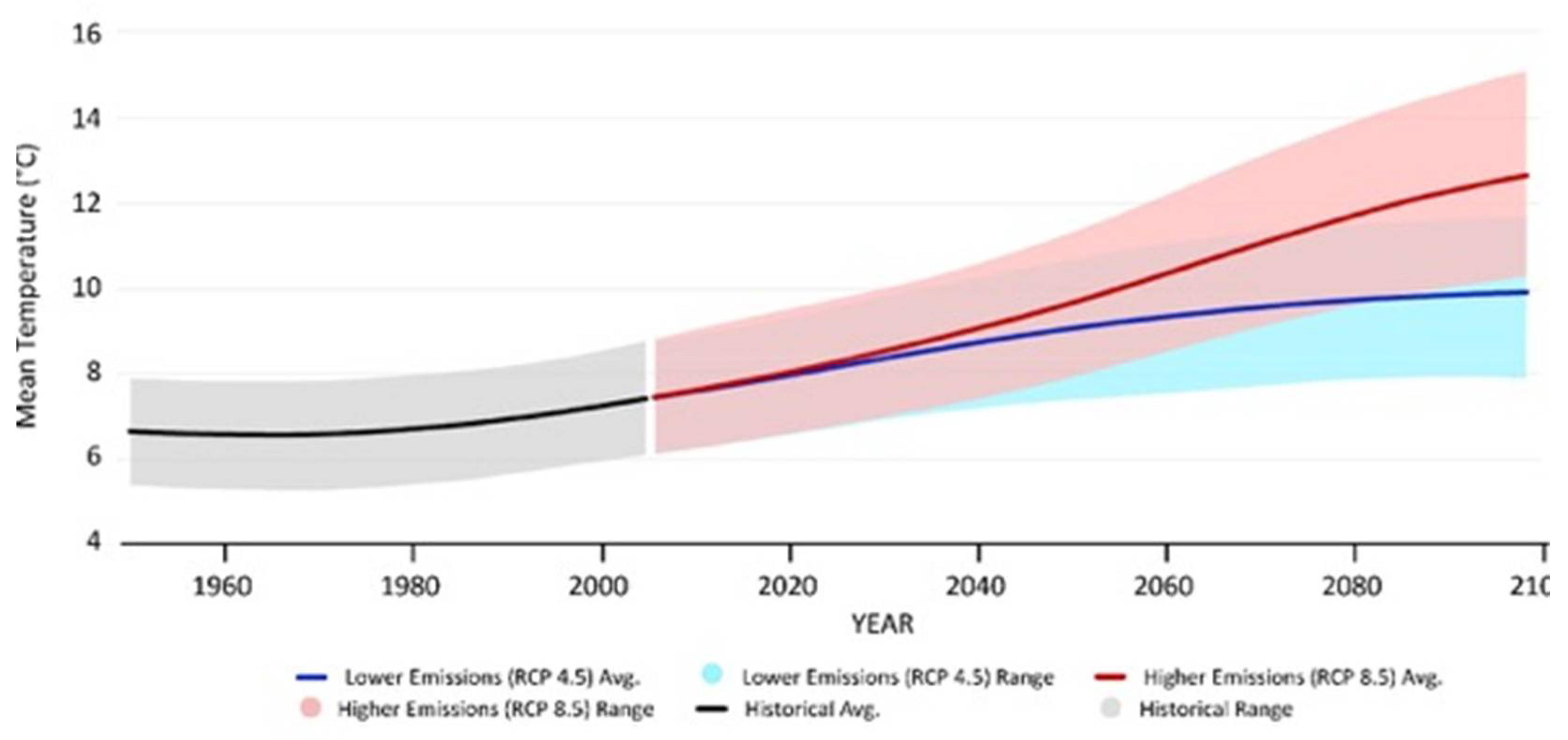

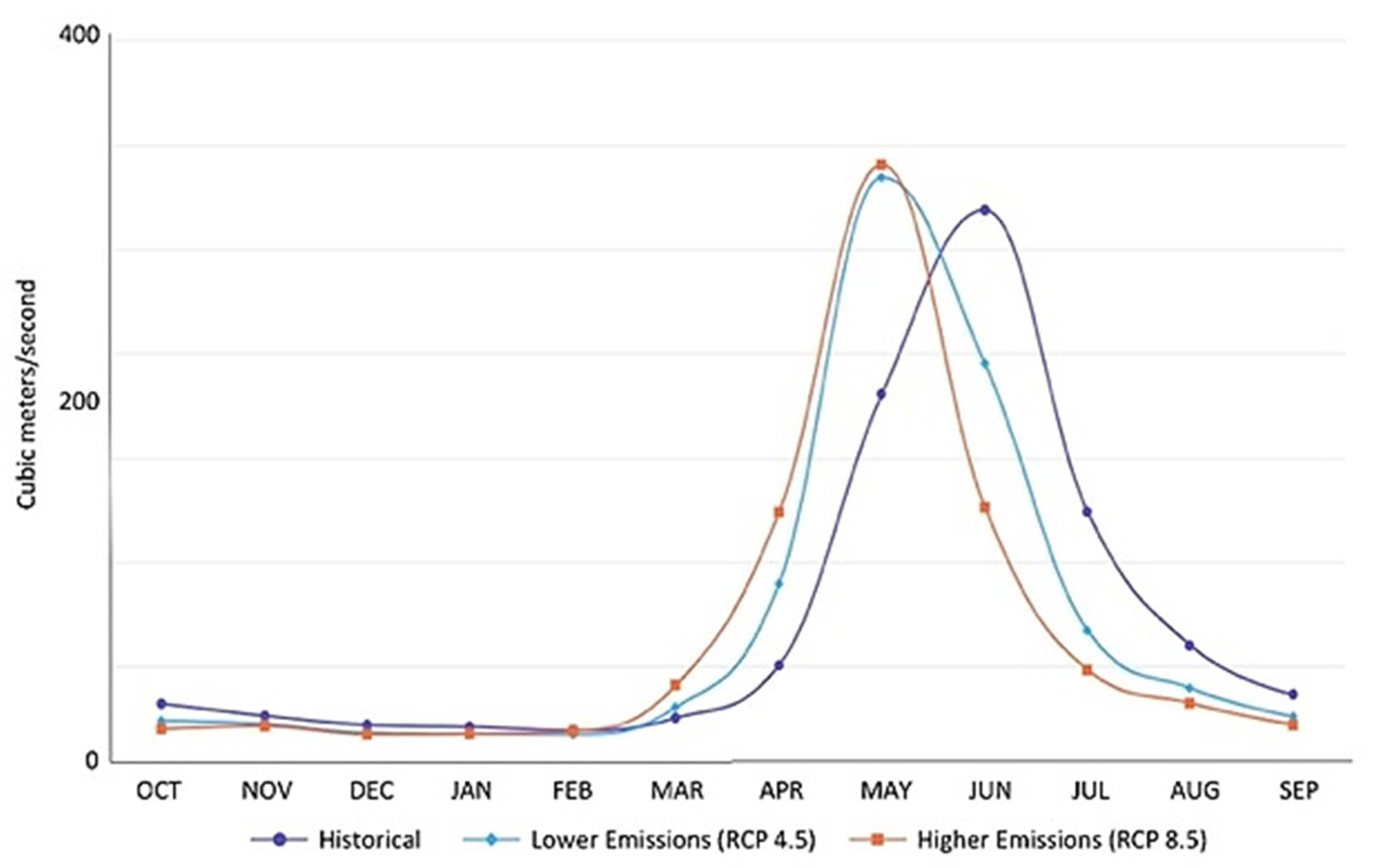

3.6. Climate Change

3.6.1. Historical Trends

3.6.2. Future Projections Under Two Emissions Scenarios

4. Discussion

4.1. Representation and Importance of Protected Areas

4.2. Focal Species Conservation

4.3. Wildfires, Wilderness, and the Wildland-Urban Interface

4.4. Climate Change

5. Conclusions and Conservation Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Bios

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinneman, D. J.; Watson, J.; Martin, W. W. The State of the Southern Rockies Ecoregion: A Look at Special Imperilment, Ecosystem Protection, and a Conservation Opportunity. Endangered Species Update. Sch. Nat. Resour. Univ. Mich. JanuaryFebruary 2000, 17 (1:1-24).

- Drummond, B. M.; Wilson, T. S.; Acevedo, W. Status and Trends of Land Change in the Western United States-1973 to 2000. USGS Professional Paper 1794-A. 2012. Available online: http://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1794/a/ (accessed on 03 June 2024).

- Neely, B.; Comer, P.; Moritz, M.; Lammerts, R.; Rondeau, C. Prague, G.; Bell, H.; Copeland, J.; Humke, S.; Spakeman, T.; Schulz, D.; Theobald, D.; Valutis, L. Southern Rocky Mountains: An ecoregional assessment and conservation blueprint; The Nature Conservancy with support from the U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Colorado Division of Wildlife, and Bureau of Land Management: Boulder, C.O., 2001. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260097702_Southern_Rocky_Mountains_an_ecoregional_assessment_and_conservation_blueprint (accessed on 21 June, 2024).

- Ricketts, T. H.; Dinerstein, E.; Olson, D. M.; Loucks, C. J. Terrestrial ecoregions of North America; Island Press: Washington, D.C, 1999.

- NatureServe. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data Accessed through NatureServe Explorer Web Application, 2024. Available online: https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.838618/Pinus_ponderosa_-_Pseudotsuga_menziesii_-_Abies_concolor_Forest_Woodland_Macrogroup (accessed 21 May 2024).

- Dinerstein, E., multiple authors. An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience 2017, 1 (6), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Noss, R. F.; Dobson, A. P.; Baldwin, R.; Beier, P.; Davis, C. R.; Dellasala, D. A.; Francis, J.; Locke, H.; Nowak, K.; Lopez, R.; Reining, C.; Trombulak, S. C.; Tabor, G. Bolder Thinking for Conservation. Conserv Biol 2012, 26 (1), 1–4.

- Watson, J. E. M.; Evans, T.; Venter, O.; Williams, B.; Tulloch, A.; Stewart, C.; Thompson, I.; Ray, J. C.; Murray, K.; Salazar, A.; McAlpine, C. The Exceptional Value of Intact Forest Ecosystems. Nat Ecol Evol 2018, 2, 599–610. [CrossRef]

- Haight, J.; Hammill, E. Protected Areas as Potential Refugia for Biodiversity under Climatic Change. Biol Conserv 2019, 241, 108258. [CrossRef]

- Hoell, A.; Funk, C.; Barlow, M.; Shukla, S. Recent and Possible Future Variations in the North American Monsoon. In The Monsoons and Climate Change: Observations and Modeling. Carvalho, L., Jones, C., Eds.; Springer Climate. Springer, Cham, 2016, pp. 149-162. [CrossRef]

- Allen, C. D.; Savage, M.; Falk, D. A.; Suckling, K. F.; Swetnam, T. W.; Schulke, T.; Stacey, P. B.; Morgan, P.; Hoffman, M.; Klingel, J. T. Ecological Restoration of Southwestern Ponderosa Pine Ecosystems: A Broad Perspective. Ecol. Appl. 2002, 12, 1418–1433. [CrossRef]

- Margolis, E. Q.; Balmat, J. Fire History and Fire-Climate Relationships along a Fire Regime Gradient in the Santa Fe Municipal Watershed, NM, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 2416–2430. [CrossRef]

- Fulé, P. Z.; Crouse, J. E.; Roccaforte, J. P.; Kalies, E. L. Do Thinning and/or Burning Treatments in Western USA Ponderosa or Jeffrey Pine-Dominated Forests Help Restore Natural Fire Behavior? For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 269, 68–81. [CrossRef]

- Haffey, C.; Sisk, T. D.; Allen, C. D.; Thode, A. E.; Margolis, E. Q. Limits to Ponderosa Pine Regeneration Following Large High-Severity Forest Fires in the United States Southwest. Fire Ecol. 2018, 14 (ue 1). [CrossRef]

- Baker, W. L.; Hanson, C. T.; DellaSala, D. A. Harnessing Natural Disturbances: A Nature-Based Solution for Restoring and Adapting Dry Forests in the Western USA to Climate Change. Fire 2023, 6, 428. [CrossRef]

- DellaSala, D. A.; Baker, B.; Hanson, C. T.; Ruediger, L.; W, B. Have Western USA Fire Suppression and Active Management Approaches Become a Contemporary Sisyphus? Biol. Conserv. 2022, 268 (109499). [CrossRef]

- Baker, W. L. Restoring and Managing Low-Severity Fire in Dry-Forest Landscapes of the Western USA. PLoS ONE 2017, 12 2. [CrossRef]

- Calkin, D. E.; Barrett, K.; Cohen, J. D.; Quarles, S. L. Wildland-Urban Fire Disasters Aren’t Actually a Wildfire Problem. PNAS 2023, 120 (51). [CrossRef]

- Law, B. E.; Bloemers, R.; Colleton, N.; Allen, M. Redefining the Wildfire Problem and Scaling Solutions to Meet the Challenge. Bull. At. Sci. 2023, 79 (6), 377-384,. [CrossRef]

- Hyden, S. Forest Service Wildfire Management Policy Run Amok. Available online: https://www.counterpunch.org/2023/08/11/forest-service-wildfire-management-policy-run-amok/ (accessed 2 June, 2024).

- Vander Lee, B.; Smith, R.; Bate, J. Ecological and Biological Diversity of the Santa Fe National Forest in Ecological and Biodiversity of National Forests in Region 3. Chapter 13. Nat Conserv 2004.

- DellaSala, D. A.; Kuchy, A. L.; Koopman, M.; Menke, K.; Fleischner, T. L.; Floyd, M. L. An Ecoregional Conservation Assessment for Forests and Woodlands of the Mogollon Highlands Ecoregion, Northcentral Arizona and Southwestern, 2023. Land 12, 2112–2112. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K. A.; Niknami, L. S.; Buto, S. G.; Decker, D. Federal Standards and Procedures for the National Watershed Boundary Dataset (WBD. US Geol. Surv. Tech. Methods 2022, 11-A3, 54 ,. [CrossRef]

- Benkman, C. W.; Balda, R. P. Adaptations for Seed Dispersal and the Compromises Due to Seed Predation in Limber Pine. Ecology 65, 632–642.

- DellaSala, D. A.; Mackey, B.; Norman, P.; Campbell, C.; Comer, P. J.; Kormos, C. F.; Keith, H.; Rogers, B. Mature and Old-Growth Forests Contribute to Large-Scale Conservation Targets in the Conterminous United States. Frontiers 2022, 5. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K. A.; Hansen, A. J.; Inman, R. M.; Lawrence, R. L.; Hoegh, A. B. Testing Landscape Resistance Layers and Modeling Connectivity for Wolverines in the Western United States. Glob Ecol Conserv 2020, 23, 01125. [CrossRef]

- Squires, J. R.; DeCesare, H. J.; Olson, L. E.; Kolbe, J. A.; Hebblewhite, M.; Parks, S. Combining Resource Selection and Movement Behavior to Predict Corridors for Canada Lynx at Their Southern Range Periphery. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 157, 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, D. N.; Crocker-Bedford, D. C.; Broberg, L.; Suckling, K. F.; Tibbitts, T. A Review of Northern Goshawk Habitat Section in the Home Range and Implications for Forest Management in the Western United States. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2005, 33(1), 120–129.

- Miller, R. A.; Carlisle, J. D.; Bechard, M. J.; Santini, D. Predicting Nesting Habitat of Northern Goshawks in Mixed Aspen-Lodgepole Pine Forests in a High-Elevation Shrub-Stepped Dominated Landscape. Open J Ecol 2013, 3, 109–115. [CrossRef]

- Wan, H. Y.; S.A., C.; Ganey, J. L. Habitat Fragmentation Reduces Genetic Diversity and Connectivity of the Mexican Spotted Owls: A Simulation Study Using Empirical Resistance Models. Genes 2018, 9 (8), 403. [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V. C.; Helmers, D. P.; Mockrin, M. H.; Carlson, A. R.; Hawbaker, T. J.; Martinuzzi, S. The 1990-2020 Wildland-Urban Interface of the Conterminous United States – Geospatial Data, 4th ed.; Forest Service Research Data Archive: Fort Collins, CO, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J. T.; Brown, T. J. A Comparison of Statistical Downscaling Methods Suited for Wildfire Applications. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 772–780. [CrossRef]

- Global Vegetation Dynamics: Concepts and Applications in the MC1 Model. In AGU Geophyiscal Monographs; Bachelet, D., Turner, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Vol. 214, p 210. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, T.; Bachelet, D.; Ferschweiler, K. Projected Major Fire and Vegetation Changes in the Pacific Northwest of the Conterminous United States under Selected CMIP5 Climate Futures. Ecol Model 2015, 317, 16–29.

- Lohmann, D. R.; Nolte-Holube, R.; Raschke, E. A Large-Scale Horizontal Routing Model to Be Coupled to Land Surface Parameterization Schemes. Tellus 1996, 48, 708–721.

- Thornton, D.; Murray, D. Modeling Range Dynamics through Time to Inform Conservation Planning: Canada Lynx in the Contiguous United States. Biol Conserv 2024, 292, 110541. [CrossRef]

- Hegewisch, K. C.; Abatzoglou, J. T. Future Time Series Web Tool. Clim. Toolbox. Available online: https://climatetoolbox.org (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Menon, M.; Landguth, E.; Leal-Saenz, A.; Bagley, J. C.; Schoettle, A. W.; Wehenkel, C.; Flores-Renteria, L.; Cushman, S. A.; Waring, K. M. Tracing the Footprints of a Moving Hybrid Zone under a Demographic History of Speciation with Gene Flow. Evol Appl 2020, 13 (1), 195–209.

- Menon, M.; Bagley, J. C.; Page, G. F. M.; Whipple, A. V.; Schoettle, A. W.; Still, C. J.; Wehenke, C.; Waring, K. M.; Flores-Renteria, L.; Cushma, S. A.; Eckert, A. J. Adaptive Evolution in a Conifer Hybrid Zone Is Driven by a Mosaic of Recently Introgressed and Background Genetic Variants. Commun Biol 2021, 4 (1), 160. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. S.; Sniezko, R. A. Quantitative Disease Resistance to White Pine Blister Rust at Southwestern White Pine’s (Pinus Strobiformis) Northern Range. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Spotted Owls and Forest Fire: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Evidence. Ecosphere 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Spotted Owls and Forest Fire: Reply. Ecosphere 2020. [CrossRef]

- Heinemeyer, K.; Squires, J.; Hebblewhite, M.; O’Keefe, J. J.; Holbrook, J. D.; Copeland, J. Wolverines in Winter: Indirect Habitat Loss and Functional Responses to Backcountry Recreation. Ecosphere 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sherriff, R. L.; Veblen, T.; Sibold, J. Fire History in High Elevation Subalpine Forests in the Colorado Front Range. Ecoscience 2007, 8, 369–380. [CrossRef]

- Addington, R. N. multiple authors. Principles and Practices for the Restoration of Ponderosa Pine and Dry Mixed-Conifer Forests of the Colorado Front Range; USDA General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-373:; Fort Collins, CO, 2018; pp 1–121. https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_series/rmrs/gtr/rmrs_gtr373.pdf.

- Hood, S.; Harvey, B. J.; Fornwalt, P. J.; Naficy, C. E.; Hansen, W. D.; Davis, K. T.; Battaglia, M. A.; Stevens-Rumann, C. S.; Saab, V. A. Fire Ecology of Rocky Mountain Forests. Chapter 8. In Fire Ecology and Management: Past, Present, and Future of US Forested Ecosystems, Managing Forest Ecosystems 39; Greenberg, C. H., Collins, B., Eds.; 2021. [CrossRef]

- McKinney, S. T. Fire Regimes of Ponderosa Pine Ecosystems in Two Ecoregions of New Mexico. In Fire Effect Information System. USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory: Missoula, MT, 2021. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/fire_regimes/NM_ponderosa_pine/all.html; (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Bradley, C. M., C. T. Hanson, DellaSala, D. A. Does increased forest protection correspond to higher fire severity in frequent-fire forests of the western United States? Ecosphere 2016, 7, 1-13.

- Flower, A.; G. Gavin, D.; Heyerdahl, E. K.; Parsons, R. A.; Cohn, G. M. Western Spruce Budworm Outbreaks Did Not Increase Fire Risk over the Last Three Centuries: A Dendrochronological Analysis of Inter-Disturbance Synergism. PLoS ONE 2014, 9 (12), e114282. [CrossRef]

- Bentz, B. J.; Regniere, J.; Fettig, C. J.; Hansen, M.; Hayes, J. L.; Hicke, J. A.; Kelsey, R. G.; Negron, J. F.; Seybold, S. J. Climate Change and Bark Beetles of the Western United States and Canada: Direct and Indirect Effects. BioScience 2010, 60 (8), 602–613. [CrossRef]

- Kulakowski, D.; Jarvis, D. The Influence of Mountain Pine Beetle Outbreaks and Drought on Severe Wildfires in Northwestern Colorado and Southern Wyoming: A Look at the Past Century. Ecol Manag 2011, 262, 1686–1696. [CrossRef]

- Six, D. L.; Biber, E.; Long, E. Management of Pine Beetle Outbreak Suppression: Does Relevant Science Support Current Policy? Forests 2014, 5, 103–133. [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. J.; Schoennagel, T.; Veblen, T. T.; Chapman, T. B. Area Burned in the Western United States Unaffected by Recent Mountain Pine Beetle Outbreaks. PNAS 2015, 112 (14), 4375–4380. [CrossRef]

- Meigs, G. W.; Zald, H. S. J.; Keeton, W. S. Do Insect Outbreaks Reduce the Severity of Subsequent Forest Fires? Environ. Res Lett 2016. [CrossRef]

- Black, S.H., Kulakowski, D., Noon, B.R., DellaSala, D. Do bark beetle outbreaks increase wildfire risks in the Central U.S. Rocky Mountains: Implications from Recent Research. Natural Areas Journal 2013, 33, 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2024. 6th Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/ (accessed 10 June 2024).

- Swanson, M. E.; Franklin J. F.; Beschta R. L.; Crisafulli C. M; DellaSala D. A.; Hutto R. L.; Lindenmayer, D. B.; Swanson, F. J. The Forgotten Stage of Forest Succession: Early-Successional Ecosystems on Forest Sites. Front Ecol Env. 2011, 9 (2), 117–125. [CrossRef]

- Executive Order 14008. FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Takes New Action to Conserve and Restore America’s Lands and Waters, 2023. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/21/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-takes-new-action-to-conserve-and-restore-americas-lands-and-waters/ (accessed 12 July 2024).

- Executive Order 14072. Strengthening The Nation’s Forest, Communities, and Local Economies, 2022. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/04/27/2022-09138/strengthening-the-nations-forests-communities-and-local-economies (accessed 12 July 2024).

- Schoennagel, T.; Balch, J. K.; Brenkert-Smith, H. Adapt to More Wildfire in Western North American Forests as Climate Changes. PNAS 2017, 114 (18), 4582–4590. [CrossRef]

- Ripple W. J.; Olwf C.; Phillips M. K.; Beschta R. L. Rewilding the American West. BioScience 2022, 72, 931–935. [CrossRef]

- Balch, J. K.; Bradley, B. A.; Abatzoglou, J. T.; Nagy, R. C.; Fusco, E. J.; Mahood, A. L. Human-Started Wildfires Expand the Fire Niche across the United States. PNAS 2017, 114 (11), 2946–2951. [CrossRef]

| Southern Rocky Mountains Ecoregion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner Category | GAP ha | Total Owner Category ha |

||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| National Park Service | 139,643 | 40,539 | 1 | 8,684 | 4,302 | 193,170 |

| (72.3) | (21.0) | (0.0) | (4.5) | (2.2) | (1.3) | |

| U.S. Bureau of Land Management | 20,911 | 104,967 | 143 | 1,059,753 | 7,847 | 1,193,622 |

| (1.8) | (8.8) | (0.0) | (88.8) | (0.7) | (8.2) | |

| USDA Forest Service | 1,486,778 | 510,940 | 1,396,938 | 3,614,900 | 9,478 | 7,019,033 |

| (21.2) | (7.3) | (19.9) | (51.5) | (0.1) | (48.5) | |

| Other Federal1 | 20 | 10,866 | 0 | 497 | 39,025 | 50,408 |

| (0.0) | (21.6) | (0.0) | (1.0) | (77.4) | (0.3) | |

| State | 79 | 52,332 | 353 | 303,385 | 202,997 | 559,145 |

| (0.0) | (9.4) | (0.1) | (54.3) | (36.3) | (3.9) | |

| Local Government | 1,284 | 24,838 | 43 | 8,924 | 52,801 | 87,889 |

| (1.5) | (28.3) | (0.0) | (10.2) | (60.1) | (0.6) | |

| Tribal | 1 | 274 | 64 | 174 | 413,551 | 414,064 |

| (0.0) | (0.1) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (99.9) | (2.9) | |

| Non-Governmental Organization |

128 | 22,579 | 10 | 2,263 | 7,185 | 32,165 |

| (0.4) | (70.2) | (0.0) | (7.0) | (22.3) | (0.2) | |

| Private | 2,326 | 209,099 | 2,174 | 108,796 | 4,603,628 | 4,926,023 |

| (0.0) | (4.2) | (0.0) | (2.2) | (93.5) | (34.0) | |

| Total GAP ha | 1,651,170 | 976,433 | 1,399,726 | 5,107,376 | 5,340,813 | 14,475,519 |

| (%) | (11.4) | (6.7) | (9.7) | (35.3) | (36.9) | |

| Southern Rocky Mountains Ecoregion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner Category | GAP ha | Total Owner Category ha |

||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| National Park Service | 12,605 | 38,609 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51,214 |

| (24.6) | (75.4) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (2.3) | |

| U.S. Bureau of Land Management | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | |

| USDA Forest Service | 162,852 | 10,581 | 99,897 | 740,343 | 36 | 1,013,710 |

| (16.1) | (1.0) | (9.9) | (73.0) | (0.0) | (46.3) | |

| Other Federal 1 | 1 | 8,003 | 2 | 41,924 | 10,287 | 60,217 |

| (0.0) | (13.3) | (0.0) | (69.6) | (17.1) | (2.8) | |

| State | 0 | 31,818 | 1 | 8,781 | 30,634 | 71,234 |

| (0.0) | (44.7) | (0.0) | (12.3) | (43.0) | (3.3) | |

| Local Government | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 893 | 897 |

| (0.0) | (0.3) | (0.1) | (0.0) | (99.6) | (0.0) | |

| Tribal | 1 | 274 | 64 | 45 | 264,245 | 264,630 |

| (0.0) | (0.1) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (99.9) | (12.1) | |

| Non-Governmental Organization |

0 | 215 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 215 |

| (0.0) | (100.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | |

| Private | 86 | 1,272 | 380 | 7,311 | 716,884 | 725,933 |

| (0.0) | (0.2) | (0.1) | (1.0) | (98.8) | (33.2) | |

| Total GAP ha | 175,546 | 90,775 | 100,345 | 798,404 | 1,022,980 | 2,188,050 |

| (%) | (8.0) | (4.1) | (4.6) | (36.5) | (46.8) | |

| Southern Rocky Mountains Ecoregion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing Vegetation Type (EVT) Category | GAP ha | Total EVT Category ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| Agricultural | 269 | 11,263 | 1,008 | 22,927 | 221,516 | 256,983 |

| (0.1) | (4.4) | (0.4) | (8.9) | (86.2) | (1.8) | |

| Alpine | 90,446 | 29,059 | 22,827 | 29,109 | 9,781 | 181,223 |

| (49.9) | (16.0) | (12.6) | (16.1) | (5.4) | (1.3) | |

| Aspen and Mixed-Conifer Forest | 5,177 | 2,484 | 17,949 | 33,109 | 9,966 | 68,684 |

| (7.5) | (3.6) | (26.1) | (48.2) | (14.5) | (0.5) | |

| Aspen Forest and Woodland | 107,598 | 92,004 | 236,841 | 500,609 | 343,511 | 1,280,563 |

| (8.4) | (7.2) | (18.5) | (39.1) | (26.8) | (8.8) | |

| Barren | 52,872 | 13,289 | 18,192 | 26,440 | 22,601 | 133,395 |

| (39.6) | (10.0) | (13.6) | (19.8) | (16.9) | (0.9) | |

| Developed | 1,443 | 4,819 | 541 | 42,593 | 167,541 | 216,938 |

| (0.7) | (2.2) | (0.2) | (19.6) | (77.2) | (1.5) | |

| Grassland | 80,727 | 95,578 | 71,477 | 386,897 | 807,428 | 1,442,106 |

| (5.6) | (6.6) | (5.0) | (26.8) | (56.0) | (10.0) | |

| Limber Pine Woodland | 4 | 237 | 26 | 2,165 | 1,489 | 3,921 |

| (0.1) | (6.1) | (0.7) | (55.2) | (38.0) | (0.0) | |

| Lodgepole Pine Forest | 114,905 | 64,508 | 137,148 | 408,600 | 106,138 | 831,299 |

| (13.8) | (7.8) | (16.5) | (49.2) | (12.8) | (5.7) | |

| Mixed-Conifer Forest | 91,210 | 87,846 | 154,977 | 506,968 | 362,187 | 1,203,189 |

| (7.6) | (7.3) | (12.9) | (42.1) | (30.1) | (8.3) | |

| Pinyon-Juniper | 18,355 | 50,682 | 36,605 | 386,388 | 463,682 | 955,712 |

| (1.9) | (5.3) | (3.8) | (40.4) | (48.5) | (6.6) | |

| Ponderosa Pine | 35,994 | 83,489 | 112,688 | 842,012 | 1,130,986 | 2,205,170 |

| (1.6) | (3.8) | (5.1) | (38.2) | (51.3) | (15.2) | |

| Riparian | 21,052 | 13,503 | 17,583 | 80,563 | 113,188 | 245,889 |

| (8.6) | (5.5) | (7.2) | (32.8) | (46.0) | (1.7) | |

| Shrubland | 67,705 | 127,211 | 118,569 | 904,887 | 1,250,583 | 2,468,954 |

| (2.7) | (5.2) | (4.8) | (36.7) | (50.7) | (17.1) | |

| Snow-Ice | 41,221 | 8,151 | 2,358 | 7,225 | 2,348 | 61,304 |

| (67.2) | (13.3) | (3.8) | (11.8) | (3.8) | (0.4) | |

| Sparse | 162,830 | 35,553 | 39,627 | 43,009 | 16,005 | 297,024 |

| (54.8) | (12.0) | (13.3) | (14.5) | (5.4) | (2.1) | |

| Subalpine Forest | 747,527 | 240,071 | 405,574 | 836,305 | 211,538 | 2,441,016 |

| (30.6) | (9.8) | (16.6) | (34.3) | (8.7) | (16.9) | |

| Water | 3,725 | 5,335 | 1,698 | 21,600 | 30,441 | 62,799 |

| (5.9) | (8.5) | (2.7) | (34.4) | (48.5) | (0.4) | |

| Wetland | 8,111 | 11,349 | 4,037 | 25,971 | 69,883 | 119,351 |

| (6.8) | (9.5) | (3.4) | (21.8) | (58.6) | (0.8) | |

| Total GAP ha | 1,651,170 | 976,433 | 1,399,726 | 5,107,376 | 5,340,813 |

14,475,519 (100%) |

| (%) | (11.4) | (6.7) | (9.7) | (35.3) | (36.9) | |

| Santa Fe Subregion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing Vegetation Type (EVT) Category | GAP ha | Total EVT Category ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| Agricultural | 40 | 455 | 101 | 1,833 | 27,075 | 29,505 |

| (0.1) | (1.5) | (0.3) | (6.2) | (91.8) | (1.3) | |

| Alpine | 453 | 141 | 25 | 182 | 1,208 | 2,009 |

| (22.6) | (7.0) | (1.2) | (9.1) | (60.1) | (0.1) | |

| Aspen and Mixed-Conifer Forest | 306 | 371 | 172 | 890 | 2,136 | 3,875 |

| (7.9) | (9.6) | (4.4) | (23.0) | (55.1) | (0.2) | |

| Aspen Forest and Woodland | 9,814 | 4,648 | 3,495 | 30,877 | 28,563 | 77,397 |

| (12.7) | (6.0) | (4.5) | (39.9) | (36.9) | (3.5) | |

| Barren | 4,045 | 438 | 290 | 799 | 3,185 | 8,757 |

| (46.2) | (5.0) | (3.3) | (9.1) | (36.4) | (0.4) | |

| Developed | 223 | 668 | 97 | 4,544 | 21,545 | 27,077 |

| (0.8) | (2.5) | (0.4) | (16.8) | (79.6) | (1.2) | |

| Grassland | 6,756 | 11,666 | 4,544 | 30,197 | 67,543 | 120,706 |

| (5.6) | (9.7) | (3.8) | (25.0) | (56.0) | (5.5) | |

| Limber Pine Woodland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | |

| Lodgepole Pine Forest | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 2 |

| (4.3) | (39.1) | (52.2) | (4.3) | (0.0) | (0.0) | |

| Mixed-Conifer Forest | 40,613 | 20,745 | 26,675 | 159,960 | 113,726 | 361,719 |

| (11.2) | (5.7) | (7.4) | (44.2) | (31.4) | (16.5) | |

| Pinyon-Juniper | 13,342 | 8,390 | 20,138 | 145,166 | 196,042 | 383,078 |

| (3.5) | (2.2) | (5.3) | (37.9) | (51.2) | (17.5) | |

| Ponderosa Pine | 16,241 | 17,185 | 21,711 | 298,328 | 308,192 | 661,657 |

| (2.5) | (2.6) | (3.3) | (45.1) | (46.6) | (30.2) | |

| Riparian | 948 | 1,146 | 495 | 4,920 | 12,284 | 19,793 |

| (4.8) | (5.8) | (2.5) | (24.9) | (62.1) | (0.9) | |

| Shrubland | 15,066 | 13,315 | 10,137 | 64,256 | 155,022 | 257,795 |

| (5.8) | (5.2) | (3.9) | (24.9) | (60.1) | (11.8) | |

| Snow-Ice | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 21 |

| (43.9) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (56.1) | (0.0) | |

| Sparse | 1,206 | 146 | 271 | 650 | 1,122 | 3,395 |

| (35.5) | (4.3) | (8.0) | (19.1) | (33.1) | (0.2) | |

| Subalpine Forest | 66,104 | 8,037 | 12,129 | 53,830 | 72,629 | 212,730 |

| (31.1) | (3.8) | (5.7) | (25.3) | (34.1) | (9.7) | |

| Water | 91 | 351 | 3 | 118 | 4,298 | 4,860 |

| (1.9) | (7.2) | (0.1) | (2.4) | (88.4) | (0.2) | |

| Wetland | 289 | 3,072 | 60 | 1,855 | 8,397 | 13,673 |

| (2.1) | (22.5) | (0.4) | (13.6) | (61.4) | (0.6) | |

| Total GAP ha | 175,546 | 90,775 | 100,345 | 798,404 | 1,022,980 |

2,188,050 (100.0) |

| (%) | (8.0) | (4.1) | (4.6) | (36.5) | (46.8) | |

| Southern Rocky Mountains Ecoregion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Structure Class | GAP ha | Total Forest Structure Class ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| Young | 214,080 | 110,619 | 189,426 | 618,906 | 381,940 | 1,514,970 |

| (14.1) | (7.3) | (12.5) | (40.9) | (25.2) | (22.9) | |

| Intermediate | 274,961 | 160,632 | 302,829 | 967,726 | 625,263 | 2,331,411 |

| (11.8) | (6.9) | (13.0) | (41.5) | (26.8) | (35.3) | |

| Mature | 387,317 | 206,024 | 438,769 | 1,078,196 | 650,641 | 2,760,947 |

| (14.0) | (7.5) | (15.9) | (39.1) | (23.6) | (41.8) | |

| Total GAP ha | 876,358 | 477,275 | 931,024 | 2,664,829 | 1,657,843 |

6,607,329 (100.0) |

| (13.3) | (7.2) | (14.1) | (40.3) | (25.1) | ||

| Santa Fe Subregion | ||||||

| Forest Structure Class | GAP ha | Total Forest Structure Class ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| Young | 16,957 | 10,126 | 9,021 | 78,272 | 78,996 | 193,372 |

| (8.8) | (5.2) | (4.7) | (40.5) | (40.9) | (15.9) | |

| Intermediate | 33,504 | 18,373 | 19,557 | 182,556 | 167,959 | 421,949 |

| (7.9) | (4.4) | (4.6) | (43.3) | (39.8) | (34.7) | |

| Mature | 74,385 | 22,007 | 41,420 | 275,932 | 187,588 | 601,332 |

| (12.4) | (3.7) | (6.9) | (45.9) | (31.2) | (49.4) | |

| Total GAP ha | 124,846 | 50,505 | 69,999 | 536,760 | 434,542 |

1,216,653 (100.0) |

| (10.3) | (4.2) | (5.8) | (44.1) | (35.7) | ||

| Southern Rocky Mountains Ecoregion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolverine Habitat Connectivity Tier | GAP ha | Wolverine Habitat Connectivity Tier ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| 90th Percentile | 370,568 | 142,632 | 259,856 | 565,749 | 255,199 | 1,594,004 |

| (23.2) | (8.9) | (16.3) | (35.5) | (16.0) | (66.7) | |

| 95th Percentile | 186,999 | 59,476 | 145,152 | 299,470 | 104,002 | 795,099 |

| (23.5) | (7.5) | (18.3) | (37.7) | (13.1) | (33.3) | |

| Total GAP ha | 557,567 | 202,108 | 405,008 | 865,219 | 359,201 | 2,389,103 |

| (23.3) | (8.5) | (17.0) | (36.2) | (15.0) | ||

| Santa Fe Subregion | ||||||

| Wolverine Habitat Connectivity Tier | GAP ha | Wolverine Habitat Connectivity Tier ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| 90th Percentile | 16,567 | 4 | 2,224 | 45,033 | 49,005 | 112,833 |

| (14.7) | (0.0) | (2.0) | (39.9) | (43.4) | (73.9) | |

| 95th Percentile | 10,559 | 2 | 809 | 13,624 | 14,807 | 39,801 |

| (26.5) | (0.0) | (2.0) | (34.2) | (37.2) | (26.1) | |

| Total GAP ha | 27,126 | 6 | 3,033 | 58,657 | 63,812 | 152,634 |

| (17.8) | (0.0) | (2.0) | (38.4) | (41.8) | ||

| Southern Rocky Mountains Ecoregion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal Species | GAP ha | Total Focal Species Suitable Habitat ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| Mexican Spotted Owl | 7,912 | 17,767 | 32,989 | 181,424 | 104,697 | 344,789 |

| (2.3) | (5.2) | (9.6) | (52.6) | (30.4) | (2.7) | |

| Northern Goshawk | 995,417 | 637,456 | 1,041,847 | 3,732,433 | 3,299,723 | 9,706,876 |

| (10.3) | (6.6) | (10.7) | (38.5) | (34.0) | (75.2) | |

| Canada Lynx | 558,604 | 258,103 | 520,036 | 1,163,796 | 356,529 | 2,857,068 |

| (19.6) | (9.0) | (18.2) | (40.7) | (12.5) | (22.1) | |

| Total GAP ha | 1,561,934 | 913,326 | 1,594,872 | 5,077,653 | 3,760,949 | 12,908,733 |

| (12.1) | (7.1) | (12.4) | (39.3) | (29.1) | ||

| Santa Fe Subregion | ||||||

| Focal Species | GAP ha | Total Focal Species Suitable Habitat ha | ||||

| (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | (%) | |

| Mexican Spotted Owl | 7,218 | 4,054 | 11,312 | 112,238 | 58,596 | 193,419 |

| (3.7) | (2.1) | (5.8) | (58.0) | (30.3) | (9.9) | |

| Northern Goshawk | 130,313 | 65,243 | 83,743 | 684,744 | 800,875 | 1,764,918 |

| (7.4) | (3.7) | (4.7) | (38.8) | (45.4) | (90.1) | |

| Canada Lynx | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | |

| Total GAP ha | 137,531 | 69,297 | 95,056 | 796,982 | 859,471 | 1,958,337 |

| (7.0) | (3.5) | (4.9) | (40.7) | (43.9) | ||

| Wildland-Urban Interface/Intermix (2020) Class | Southern Rocky Mountains Ecoregion | Santa Fe Subregion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ha | Burned ha | All ha | Burned ha | |

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Low Density Intermix | 410,361 | 25,685 | 51,441 | 4,909 |

| (75.6) | (88.5) | (77.0) | (90.9) | |

| Medium Density Intermix | 69,114 | 1,442 | 7,392 | 166 |

| (12.7) | (5.0) | (11.1) | (3.1) | |

| High Density Intermix | 237 | 2 | 26 | 1 |

| (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | (0.0) | |

| Low Density Interface | 25,640 | 1,536 | 5,086 | 165 |

| (4.7) | (5.3) | (7.6) | (3.1) | |

| Medium Density Interface | 31,149 | 295 | 2,495 | 113 |

| (5.7) | (1.0) | (3.7) | (2.1) | |

| High Density Interface | 6,097 | 78 | 357 | 48 |

| (1.1) | (0.3) | (0.5) | (0.9) | |

| Total ha | 542,599 | 29,037 | 66,797 | 5,402 |

| (%)1 | (3.8) | (2.3) | (3.1) | (1.5) |

| Average Annual Temperature | +1.2°C |

| Maximum Temperature | +0.8°C |

| Minimum Temperature | +1.5°C |

| Frost Free Days | +29 days longer frost-free season |

| Annual Precipitation | -15% |

| Drought2 | Increasing frequency |

| Snowpack3 | <20% at most sites |

| Years | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 32°C | > 38°C | > 41°C | > 32°C | > 38°C | > 41°C | |

| 2040-69 | +19.6 | +1.3 | +0.1 | +12.3 | +0.4 | +0.0 |

| 2070-99 | +39.3 | +6.4 | +1.1 | +15.2 | +0.7 | +0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).