1. Introduction

As a key component of aircraft, an excellent aerodynamic configuration of the airfoil plays a crucial role in fuel economy, reducing polluting emissions and improving performance [

1,

2,

3]. In the design of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and gliders, the development of wing configurations with a high aspect ratio is also being opted for, because these wing configurations provide a better range and flight duration. In UAVs there is a greater interest in improving the flight duration, especially in subsonic flight missions, in missions such as: reconnaissance, target tracking, pseudo-satellites, etc [

4].

Taking into account the aircraft powered by propeller engines, aerodynamically, an aircraft to achieve a large endurance its C

L1.5/C

D (C

L, lift coefficient; C

D, drag coefficient) ratio values should be the highest possible [

5]. This C

L1.5/C

D ratio is usually called the endurance parameter. As mentioned above, this is mainly achieved by having a wing with a high aspect ratio, but the shape of the airfoils along the wingspan is also of utmost importance, which should also provide a high c

l1.5/c

d value [

4,

6]. The design of this type of airfoils is obtained by optimizing the shape of the airfoil, which must produce a high value of the endurance parameter with respect to a design lift coefficient. It is important to mention that airfoils with high values of c

l1.5/c

d and c

l usually have convex shapes that generate very negative values of pitch moment coefficient (c

m). This drawback is compensated by the empennage of the aircraft. Although in aircraft configurations that lack a horizontal empennage (such as flying wings) it is necessary that the c

m be as close to zero, for this reason in these cases an extra objective function is usually added to the optimization task, minimizing |c

m| [

4,

7].

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD), wind tunnel testing and theoretical analysis have gradually become the main approaches to aerodynamic design, advancing the progress of aerodynamic optimization of airfoils. However, in real engineering design, wind tunnel tests are expensive, and theoretical analysis is less applicable when dealing with complex engineering problems, so CFD has gradually become the main method for aerodynamic analysis [

8].

The basic element of aerodynamic optimization of the airfoil mainly includes the design object, the design objective, the design constraints and the design method (optimization method). Design object refers to the aerodynamic geometric configuration. The design objective refers to the expected aerodynamic performance, the characteristics of the flow field, etc. The design constraints illustrate the interdependence and constraints between the design variables of the design object. And optimization methods provide the strategies and means to achieve the design goal [

8].

Currently there are a large number of optimization methods that are widely used. These methods can be generally classified into gradient-based and gradient-free optimization methods. Current gradient-based approaches use discrete adjunct sensitivity analysis, scale approximately linearly with the number of design variables, and are very capable of handling thousands of design variables and constraints. The advantages of gradient-based optimization to address airfoil shape optimization are low computational costs in large design spaces and a track record of successful implementations in aerodynamics. However, there are some drawbacks to this approach, such as the tendency to converge on local optima and a high sensitivity to the starting point, poor efficiency for nonlinear cost functions and the need for continuous shapes (the shape gradient must exist at all points). The gradient-based approach may be more appropriate for a detailed aerodynamic design, as they are only able to offer a limited range of solutions. Gradient-free methods can be more complex to implement than gradient-based methods, but they do not require continuity or predictability in the design space and usually increase the probability of finding a global optimum. Optimization methods known as metaheuristics can offer robust methods for finding a solution and increase the probability of converging on a solution at the global optimum. It is known that these gradient-free methods are able to address numerically noisy optimization problems that are difficult for gradient-based methods. And unlike gradient methods, derivatives of cost functions are not necessary. In addition, no predefined baseline design or knowledge of the design space is required and gradient-free methods usually optimize several solutions in parallel. However, their convergence speeds are usually slow enough that they are unable to cooperate directly with time-consuming CFD analysis. To counteract this disadvantage that metaheuristic methods have, in the first instance, more robust computing equipment is used (which implies raising the costs of the optimization process). Another alternative is to make use of methods based on surrogate models [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Traditional methods for training surrogate models include the polynomial response surface method, the support vector regression method, and the Kriging model. The traditional substitute model has adjustable parameters; however, the main problem is that it is not suitable for handling large-scale training data, so it is usually trained with a small amount of data in a relatively limited space [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Recent advances in machine learning (especially in deep learning methods: artificial neural networks) have provided a new option for generating surrogate models. Compared to traditional surrogate models, the advantages of applying neural networks in aerodynamic data modeling lie in the fact that: a) neural networks, as a data-driven model, are not based on aerodynamic theories or physical models, which means that it does not require in-depth knowledge of aerodynamics; b) neural networks can be used to address high-dimensional, multi-scale and nonlinear problems that are difficult for traditional surrogate models; and c) some neural networks have the ability to process time sequence data [

13].

In the present work, a methodology is developed to accelerate the process of airfoil optimization under conditions of subsonic, incompressible and turbulent flow, making use of current deep learning models and metaheuristic algorithms. This research work is specifically aimed at the design of aircraft with long endurance operating in subsonic flight regime.

4. Conclusions

As part of this work, a methodology was developed to generate optimization algorithms, aimed at the aerodynamic optimization of airfoils under conditions of subsonic, incompressible and turbulent flow. In the development process, metaheuristic algorithms (specifically evolutionary algorithms) and different artificial neural network architectures were evaluated. The purpose of the algorithms developed is that they can be used in the early stages of aircraft design with high elongation and long flight duration. To achieve the established goal, the following research and developments were carried out:

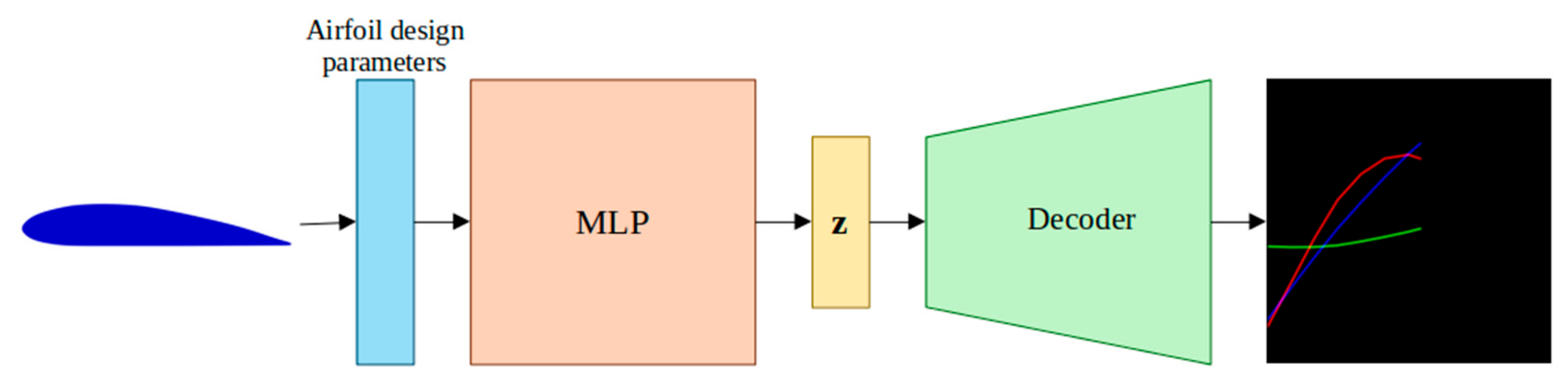

An artificial neural network architecture, AZTLI-NN, (composed of a multilayer perceptron and a variational autoencoder) was developed for aerodynamic response prediction. A new image-based coding was proposed for the output parameters of the neural network, the neural network has the ability to generate the diagrams of the aerodynamic coefficients as a function of the angle of attack. For the training of the neural network, a database of wing airfoils was generated with their respective aerodynamic coefficients (lift coefficient, drag coefficient, pitch moment coefficient) using computational aerodynamics. The procedure of the numerical simulations was validated with experimental cases. Airfoil parameterization methods were evaluated to determine which provided the best performance when reconstructing wing airfoils.

Evolutionary algorithms of mono-objective and multi-objective optimization were adapted so that they could be used in conjunction with the AZTLI-NN network.

The performance of each of the algorithms was evaluated. Several tests were carried out to evaluate the repeatability of the results and the consistency in the computation times. In both cases, repeatability of the results was obtained, and the computation times are suitable for the algorithms to be considered in early-stage design processes.

Therefore, the work carried out achieves the practical importance raised, since not only was it possible to meet the established objective, but also provided a background to achieve the development of neural network architectures and adapt evolutionary algorithms to be used in optimization tasks of airfoils aimed at different tasks. For example, the proposed methodology can be used in the design of aircraft operating in different flight regimes, in the design of propellers, in the design of wind turbines, etc.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.Q.P.; methodology, J.G.Q.P.; software, J.G.Q.P.; validation, J.G.Q.P.; formal analysis, J.G.Q.P.; investigation, J.G.Q.P.; resources, E.K., and O.L.; data curation, J.G.Q.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.Q.P.; writing—review and editing, V.S., E.M., E.K., and O.L.; visualization, V.S., and E.K.; supervision, V.S., E.M., E.K., and O.L.; project administration, J.G.Q.P.; funding acquisition, E.M. and E.K.,. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

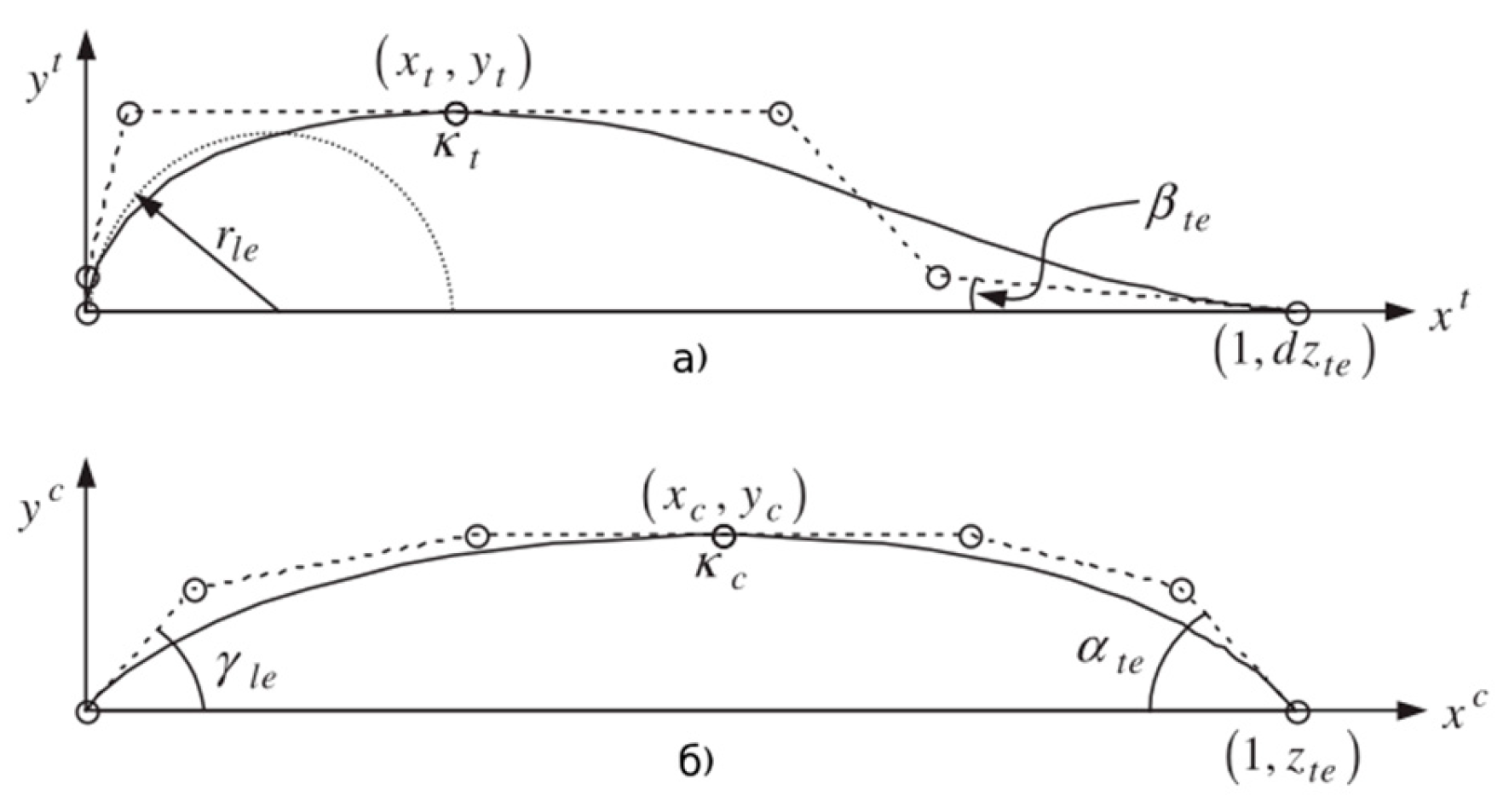

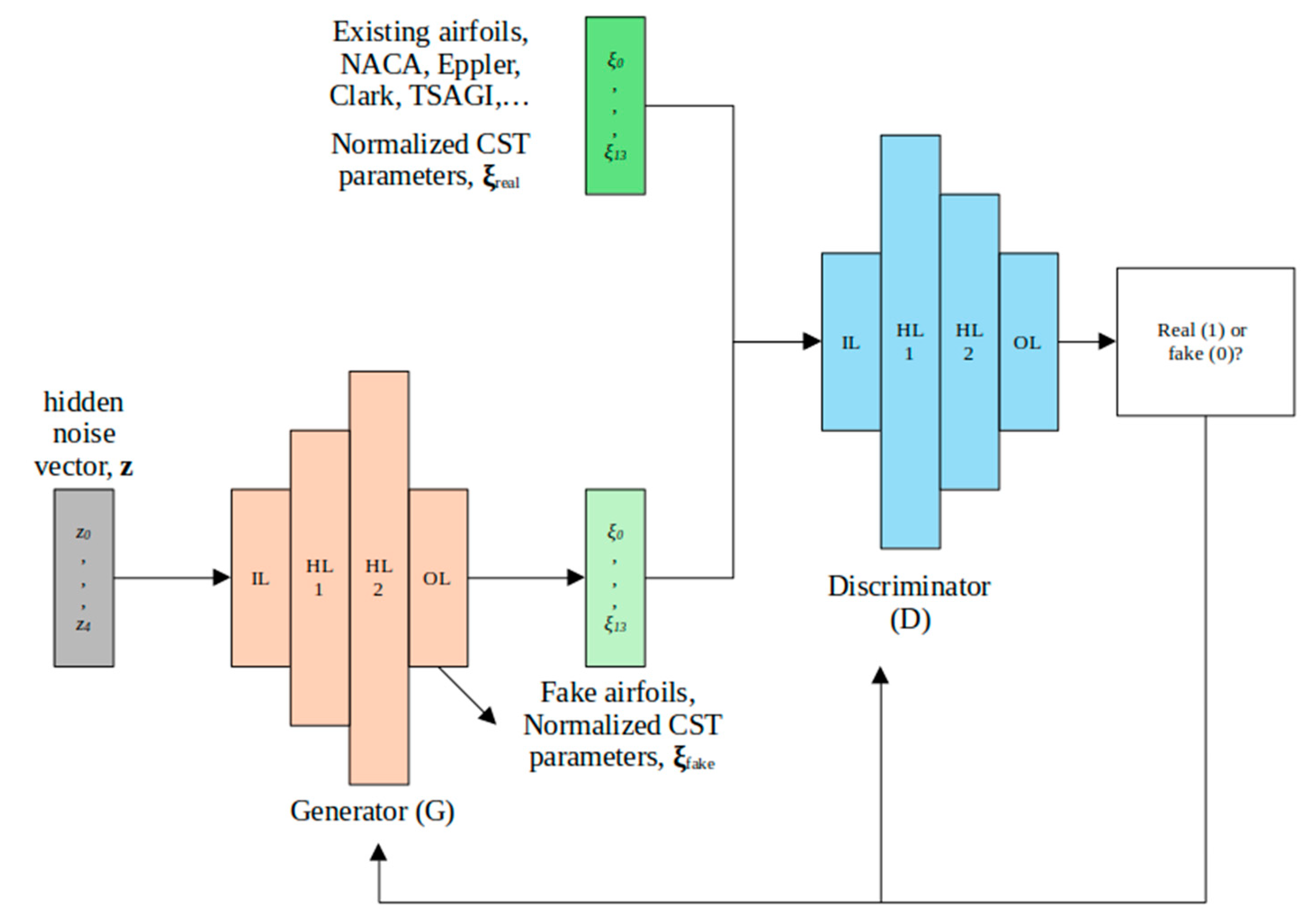

Figure 1.

General architecture of the architecture of a GAN.

Figure 1.

General architecture of the architecture of a GAN.

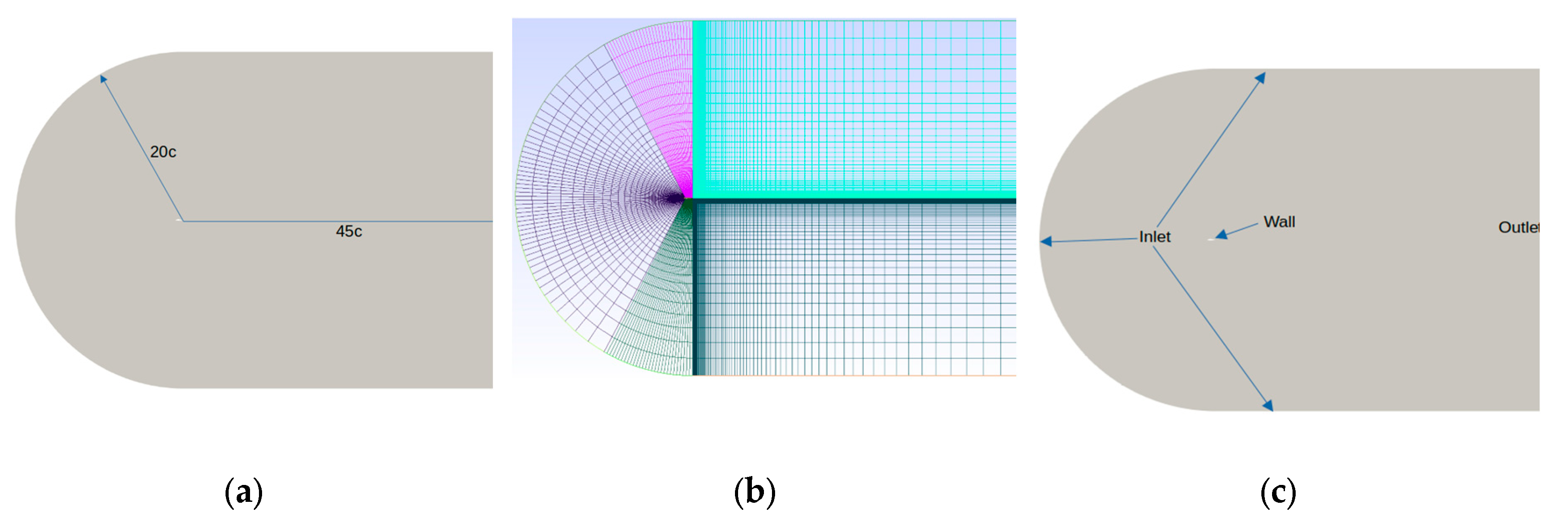

Figure 2.

(a) Dimensions of the control volume, c is the chord length of the profile; (b) General view of the mesh; (c) Boundary conditions of the control volume.

Figure 2.

(a) Dimensions of the control volume, c is the chord length of the profile; (b) General view of the mesh; (c) Boundary conditions of the control volume.

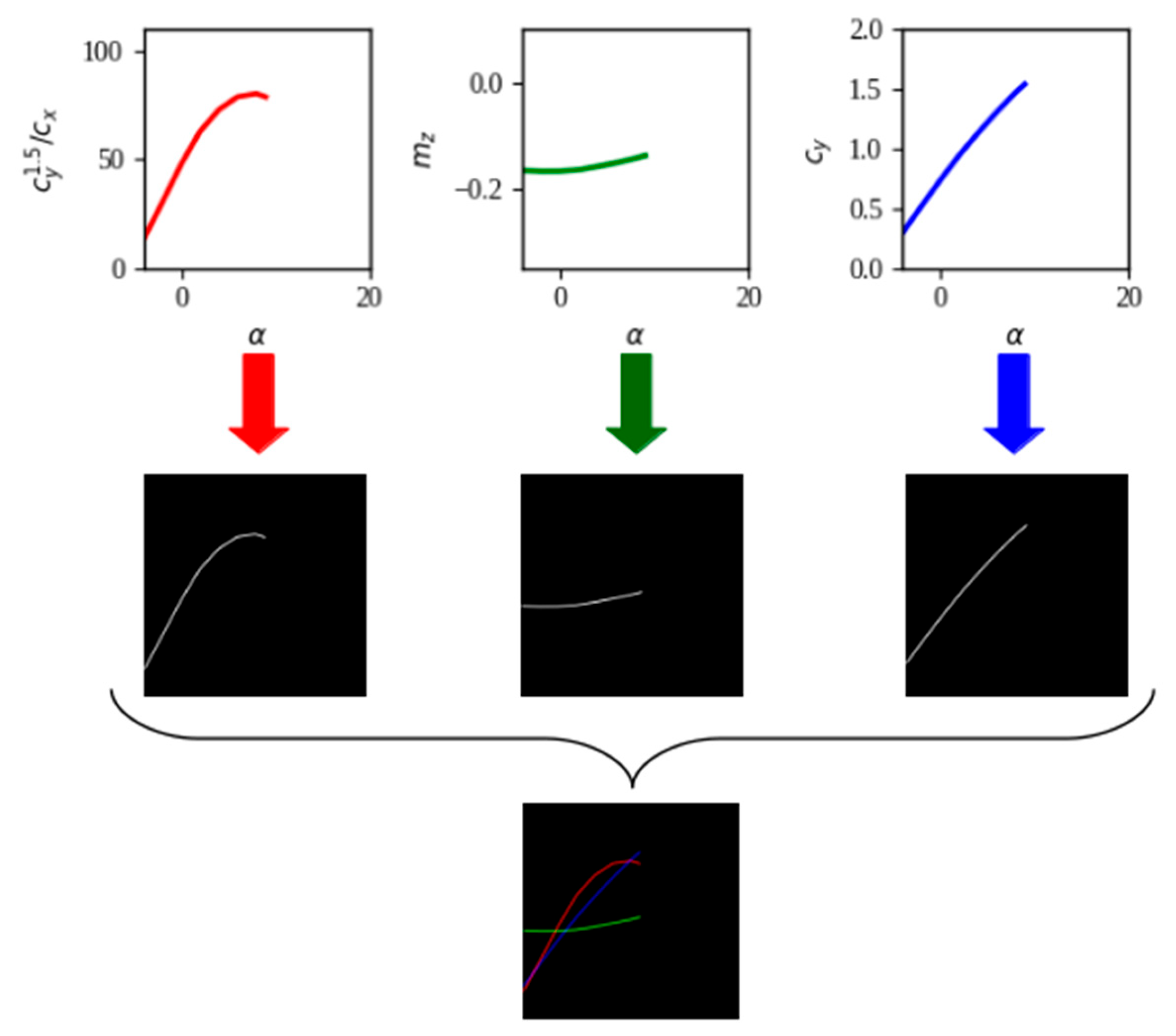

Figure 3.

Creation of the output data (output images) representing the aerodynamic coefficients of the airfoils.

Figure 3.

Creation of the output data (output images) representing the aerodynamic coefficients of the airfoils.

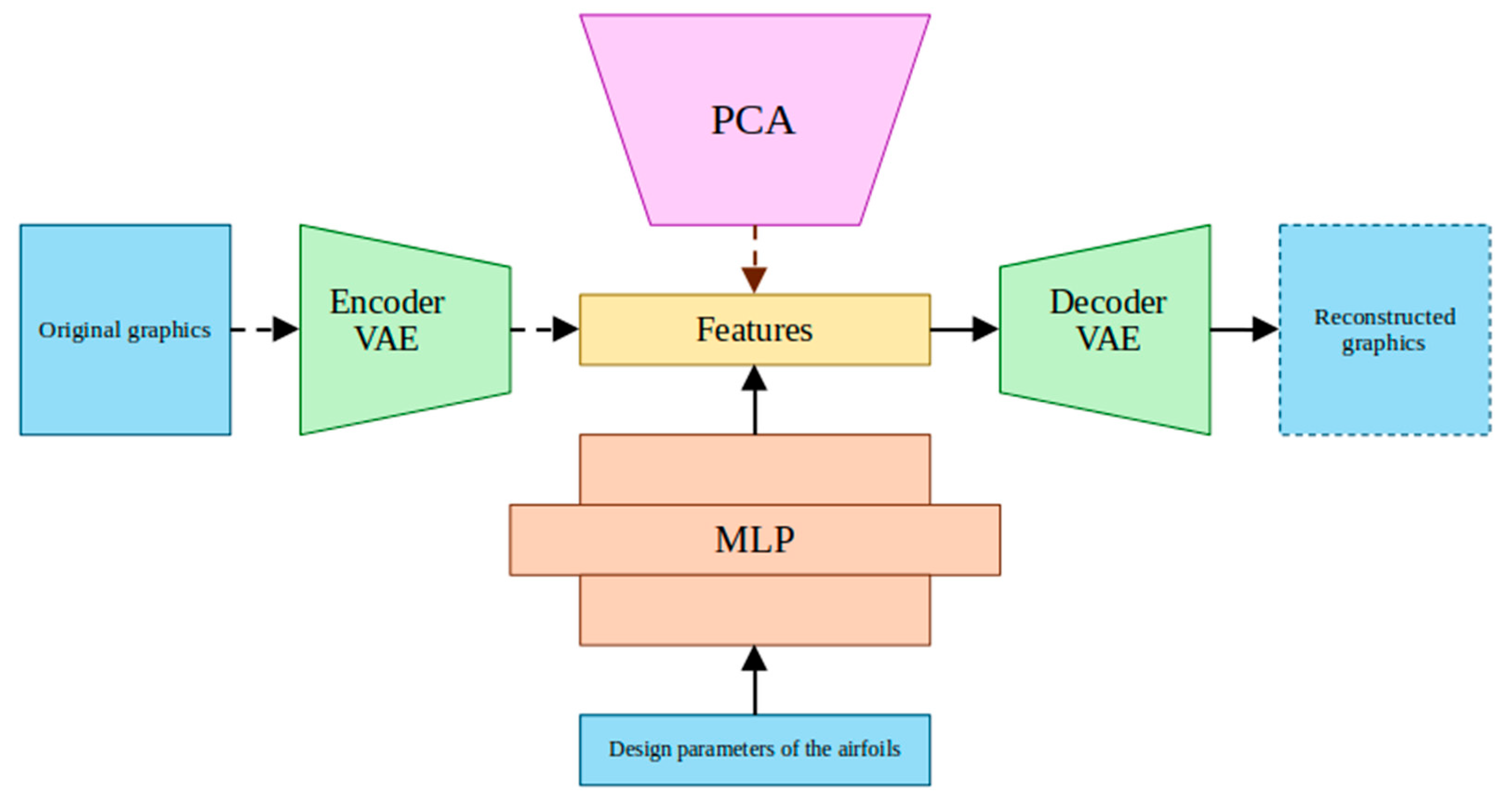

Figure 4.

Methodology of design of a neural network to predict aerodynamic coefficients.

Figure 4.

Methodology of design of a neural network to predict aerodynamic coefficients.

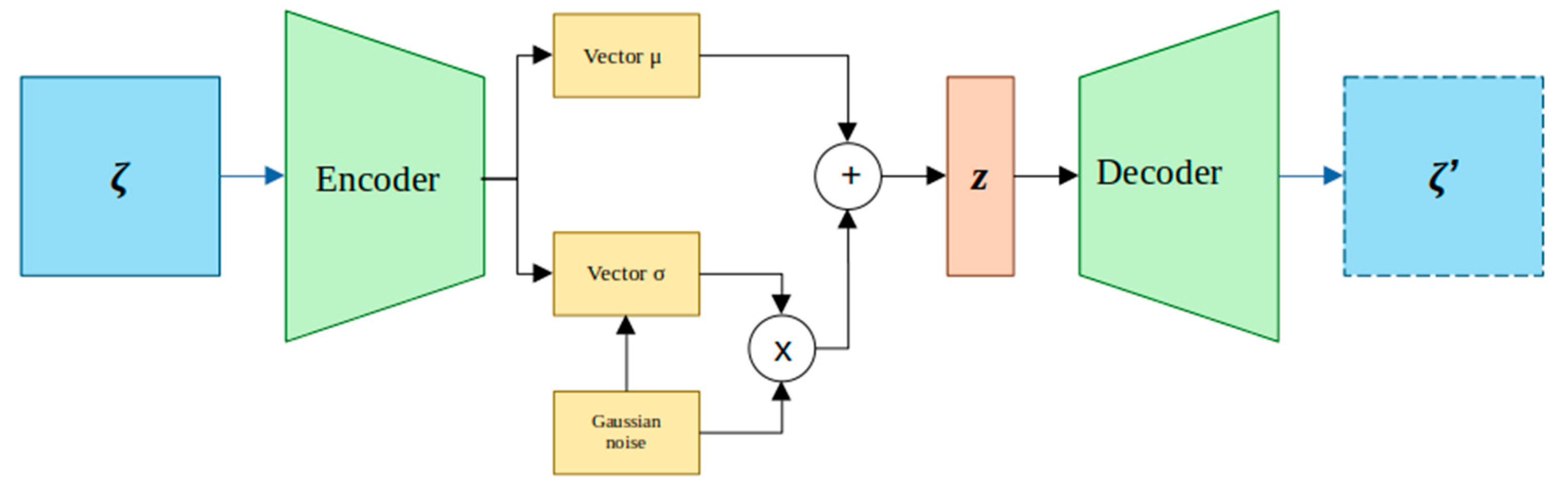

Figure 5.

General architecture of a VAE.

Figure 5.

General architecture of a VAE.

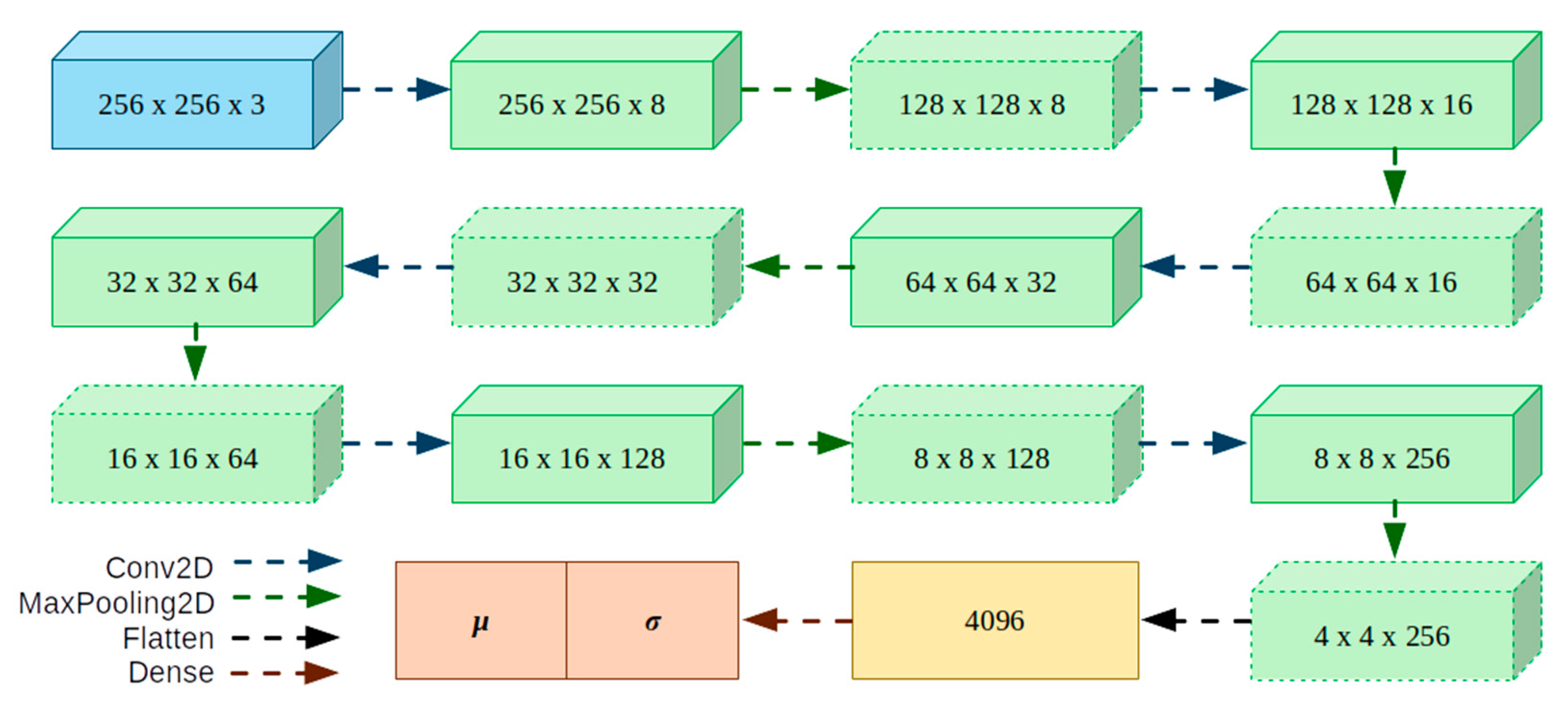

Figure 6.

Architecture of the encoder.

Figure 6.

Architecture of the encoder.

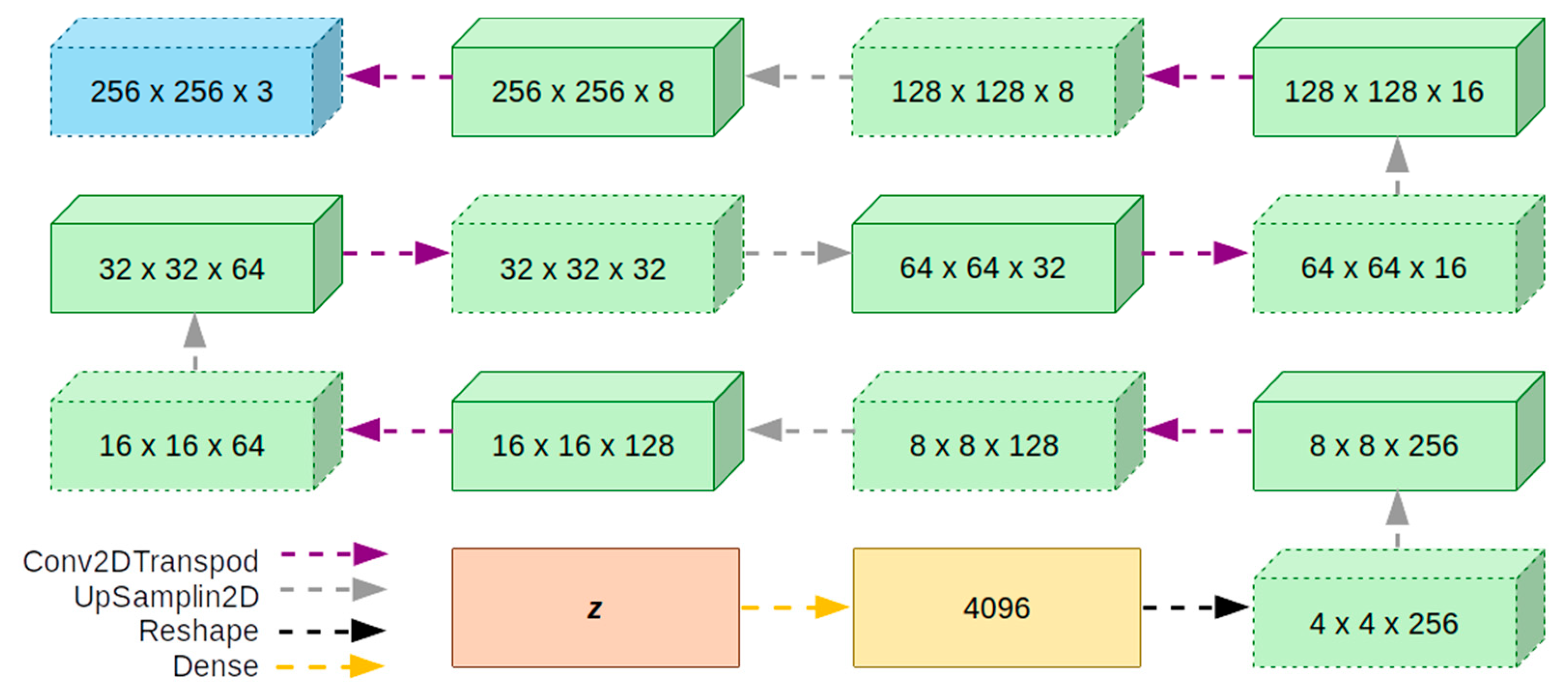

Figure 7.

Architecture of the decoder.

Figure 7.

Architecture of the decoder.

Figure 8.

Final architecture of the neural network “AZTLI-NN” used to predict aerodynamic coefficients of the airfoils.

Figure 8.

Final architecture of the neural network “AZTLI-NN” used to predict aerodynamic coefficients of the airfoils.

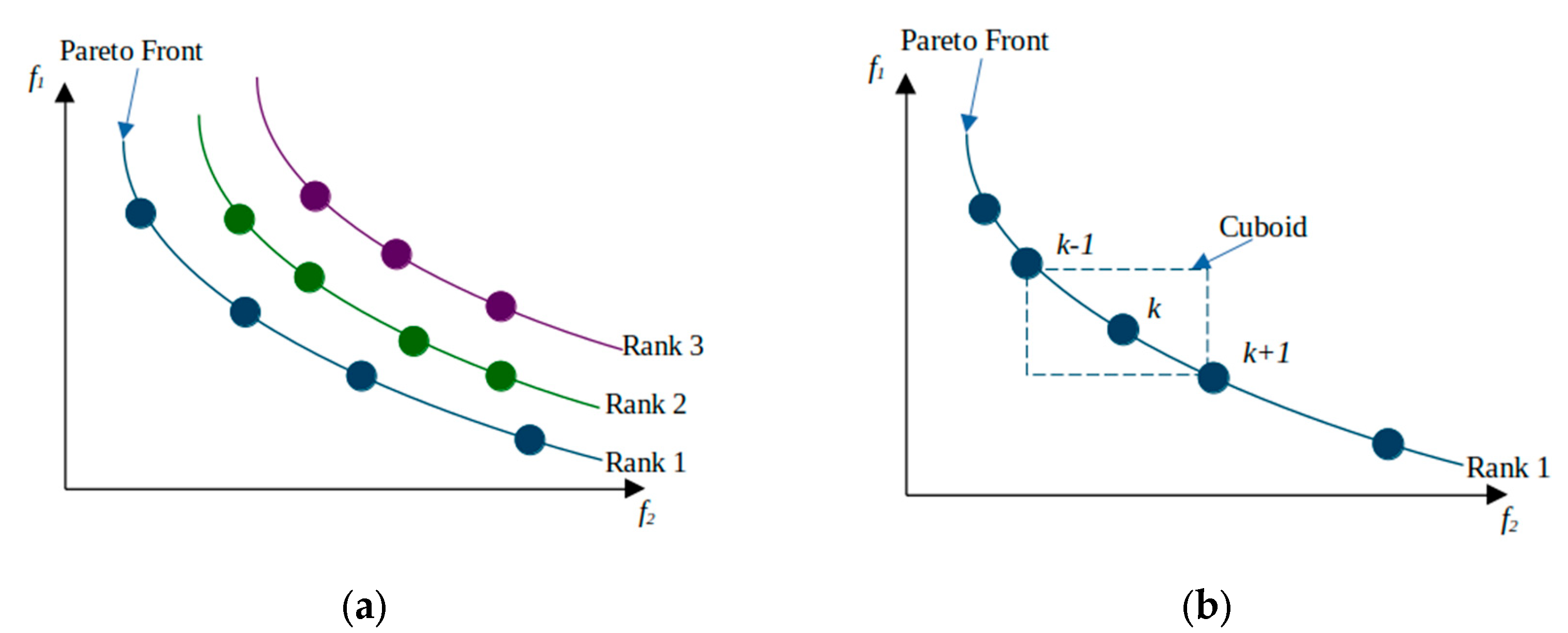

Figure 9.

(a) non-dominated classification; (b) crowding distance.

Figure 9.

(a) non-dominated classification; (b) crowding distance.

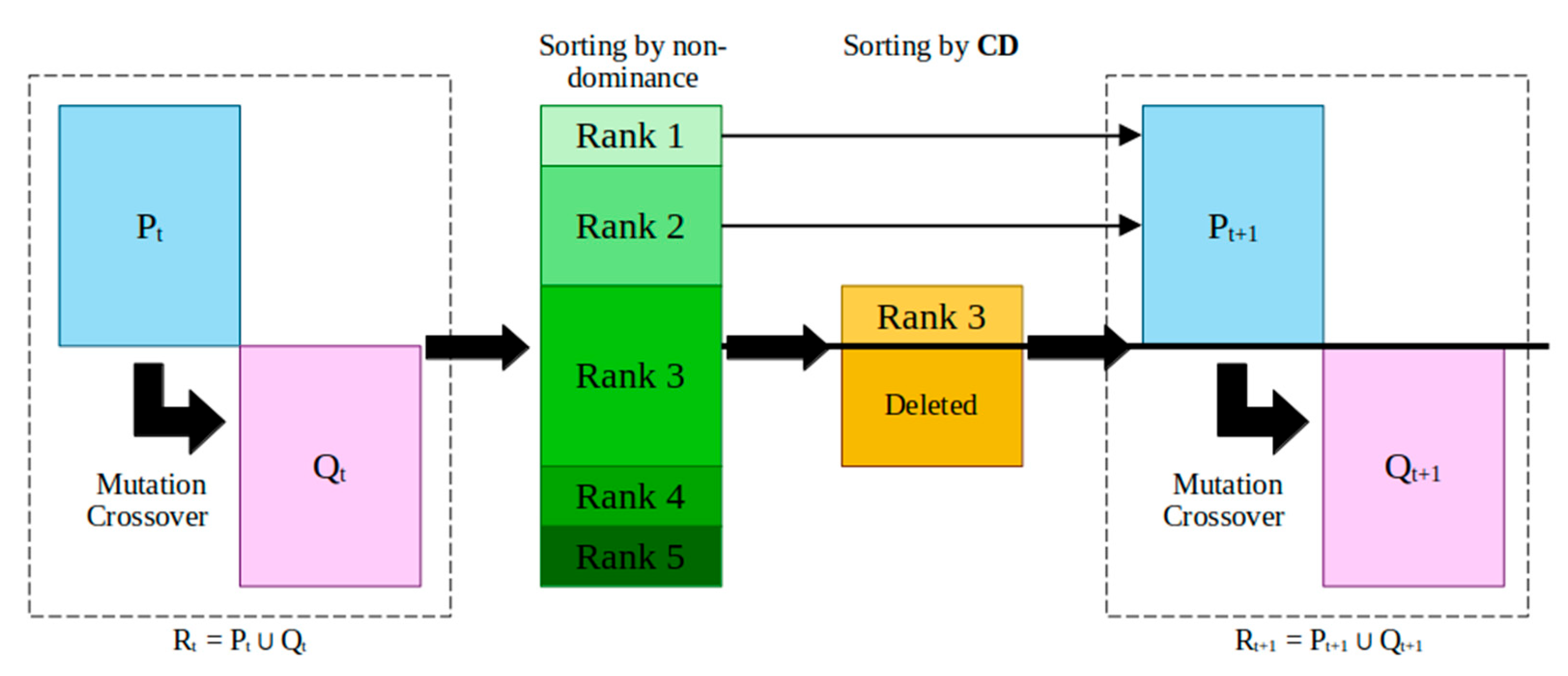

Figure 10.

The procedure for conducting NSGA-II.

Figure 10.

The procedure for conducting NSGA-II.

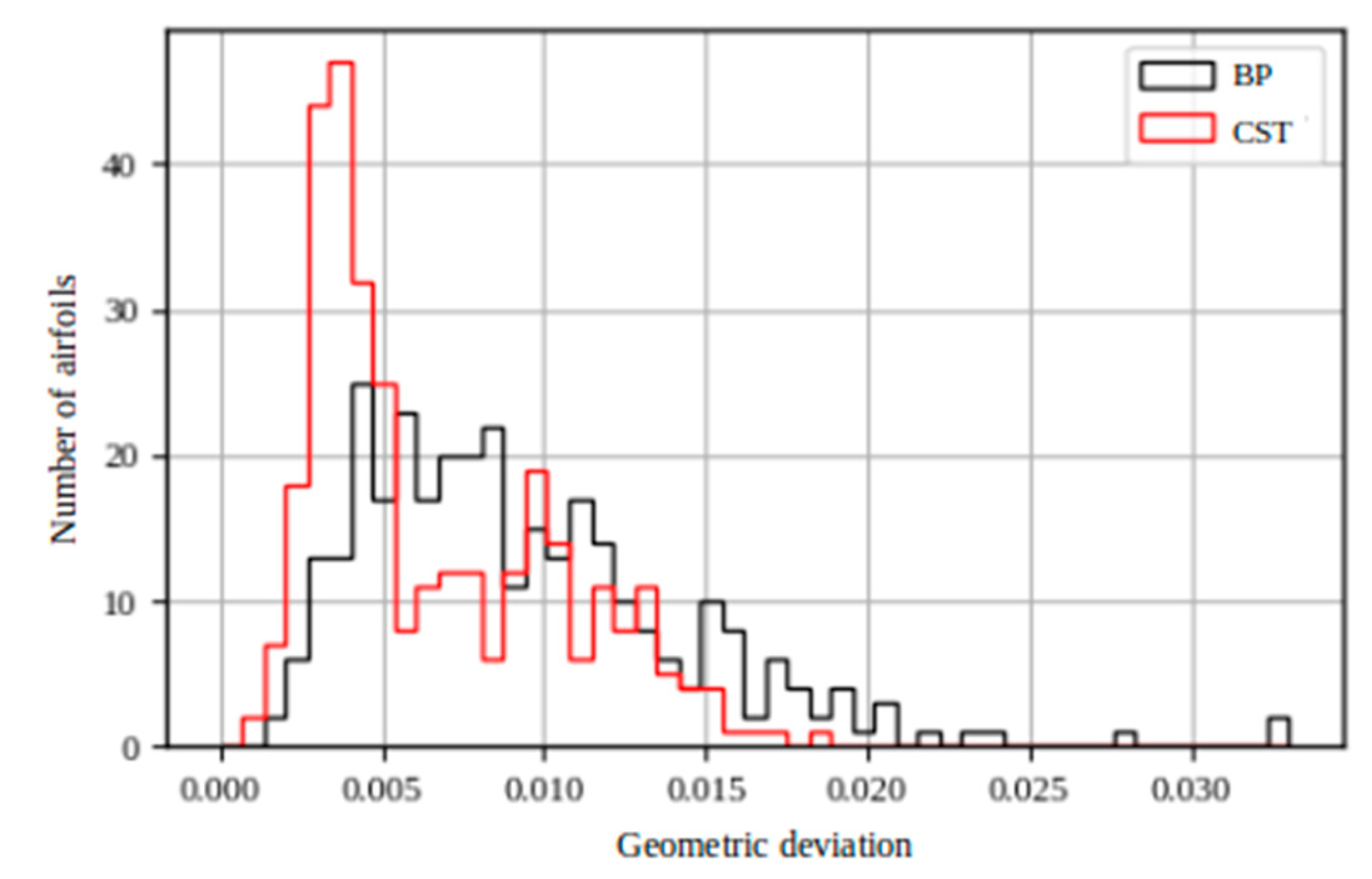

Figure 11.

Results obtained from the airfoil reconstruction tests.

Figure 11.

Results obtained from the airfoil reconstruction tests.

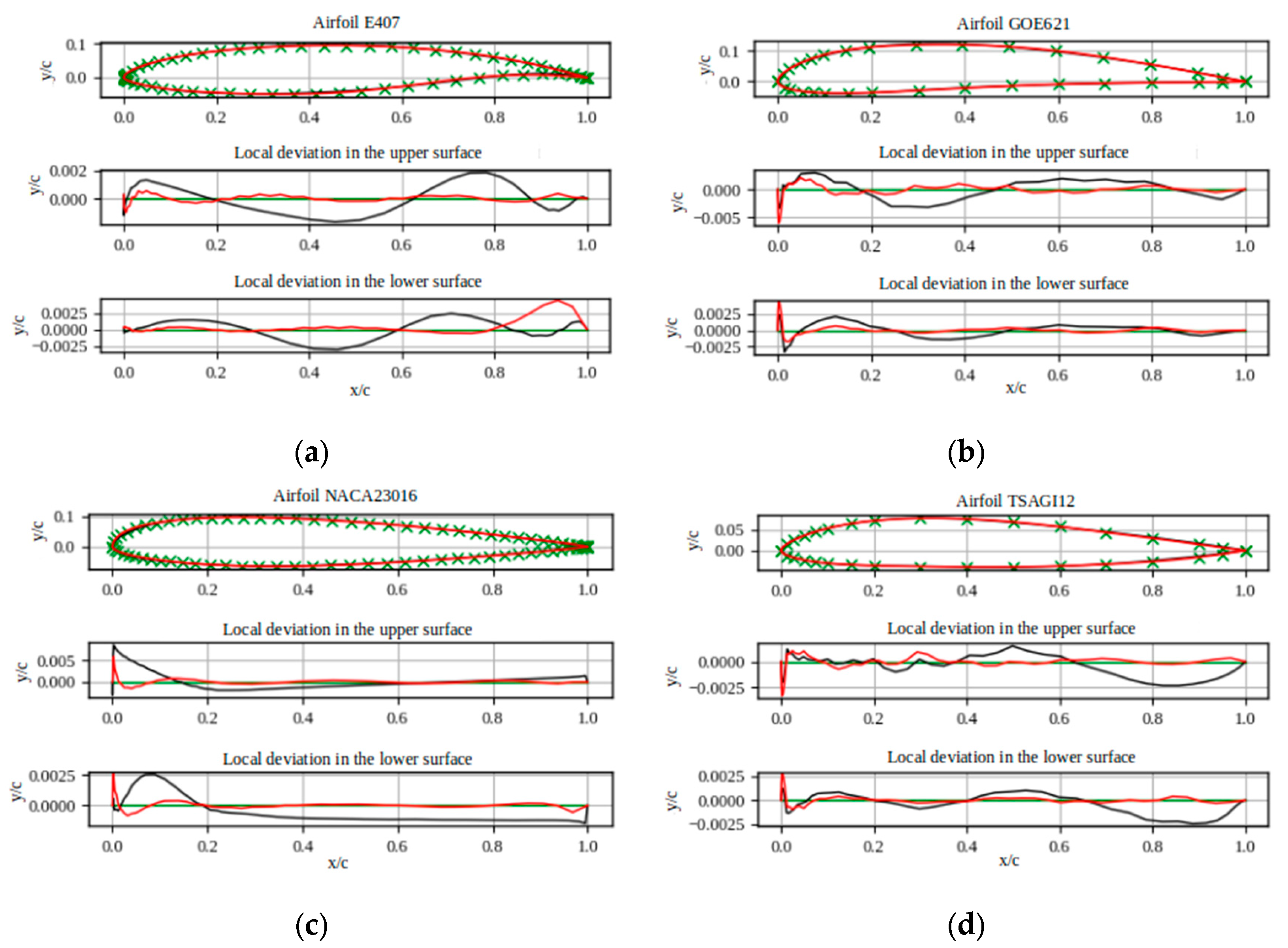

Figure 12.

Airfoils reconstructed using the Bezier-PARSEC method (black) and the CST method (red). The original coordinates are shown in green. (a) Eppler 407 airfoil, (b) Gottingen 621 airfoil, (c) NACA airfoil of the 5-digit series NACA23016, and (d) TSAGI 12 airfoil.

Figure 12.

Airfoils reconstructed using the Bezier-PARSEC method (black) and the CST method (red). The original coordinates are shown in green. (a) Eppler 407 airfoil, (b) Gottingen 621 airfoil, (c) NACA airfoil of the 5-digit series NACA23016, and (d) TSAGI 12 airfoil.

Figure 13.

Architecture of the GAN used to create new airfoils.

Figure 13.

Architecture of the GAN used to create new airfoils.

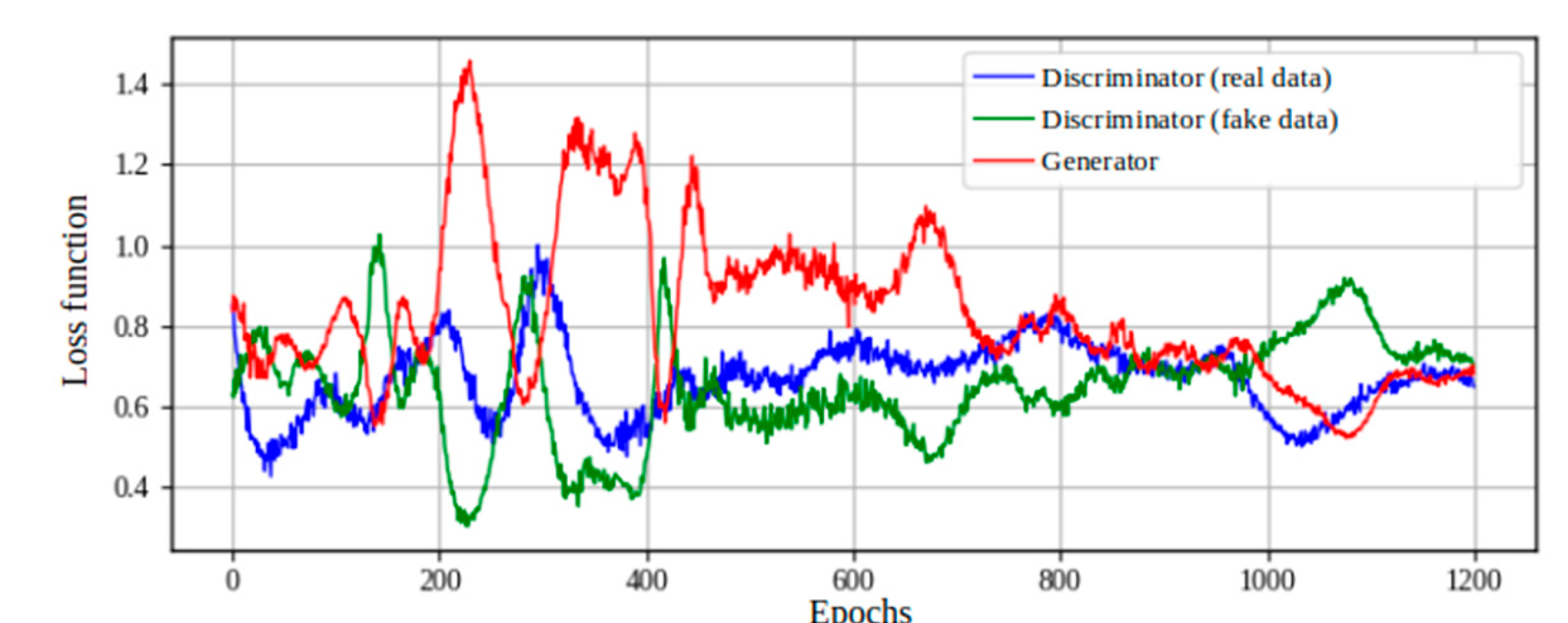

Figure 14.

Training of the GAN.

Figure 14.

Training of the GAN.

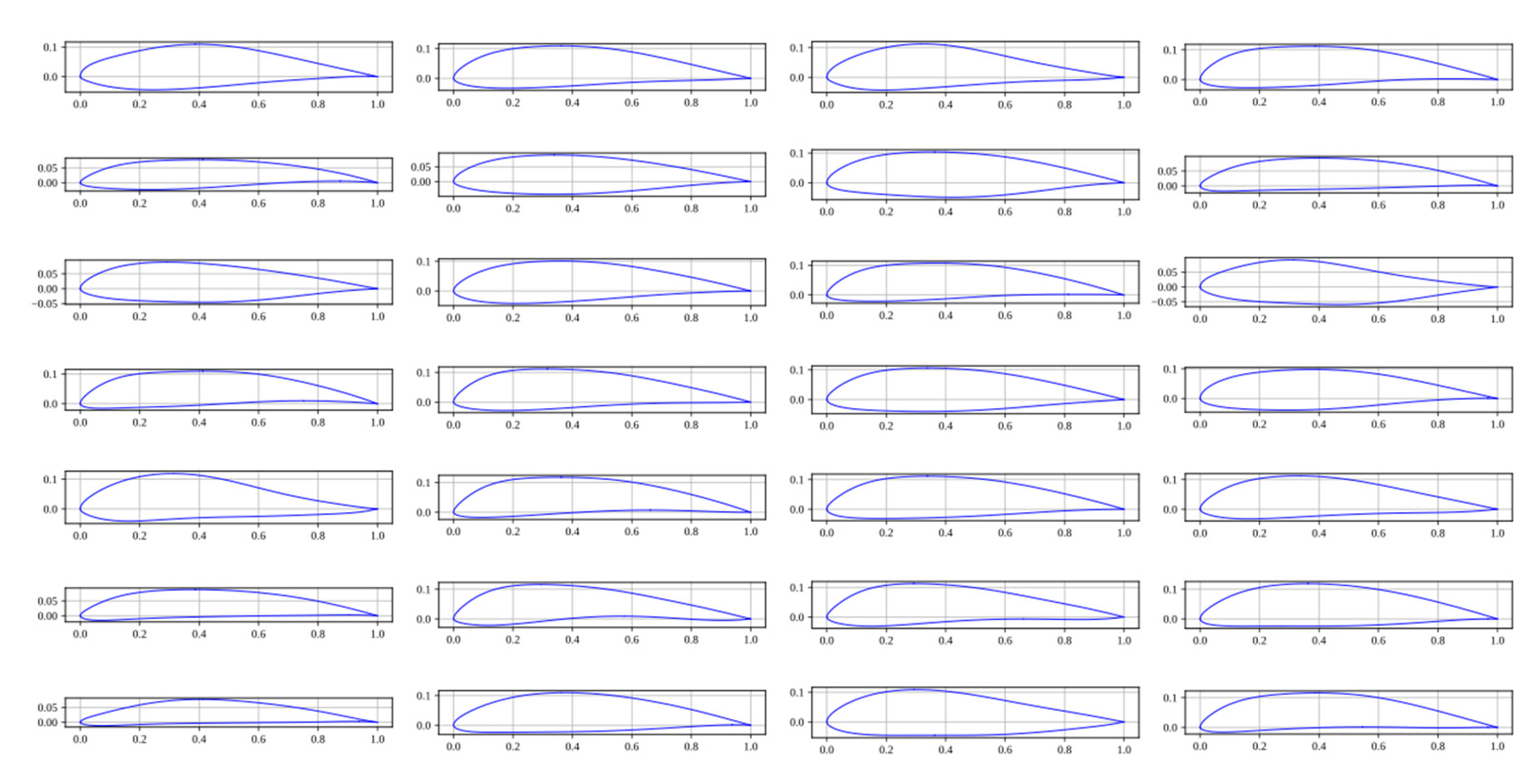

Figure 15.

Airfoils obtained after 1200 learning epochs.

Figure 15.

Airfoils obtained after 1200 learning epochs.

Figure 16.

Aerodynamic coefficients of the NACA 0012 airfoil.

Figure 16.

Aerodynamic coefficients of the NACA 0012 airfoil.

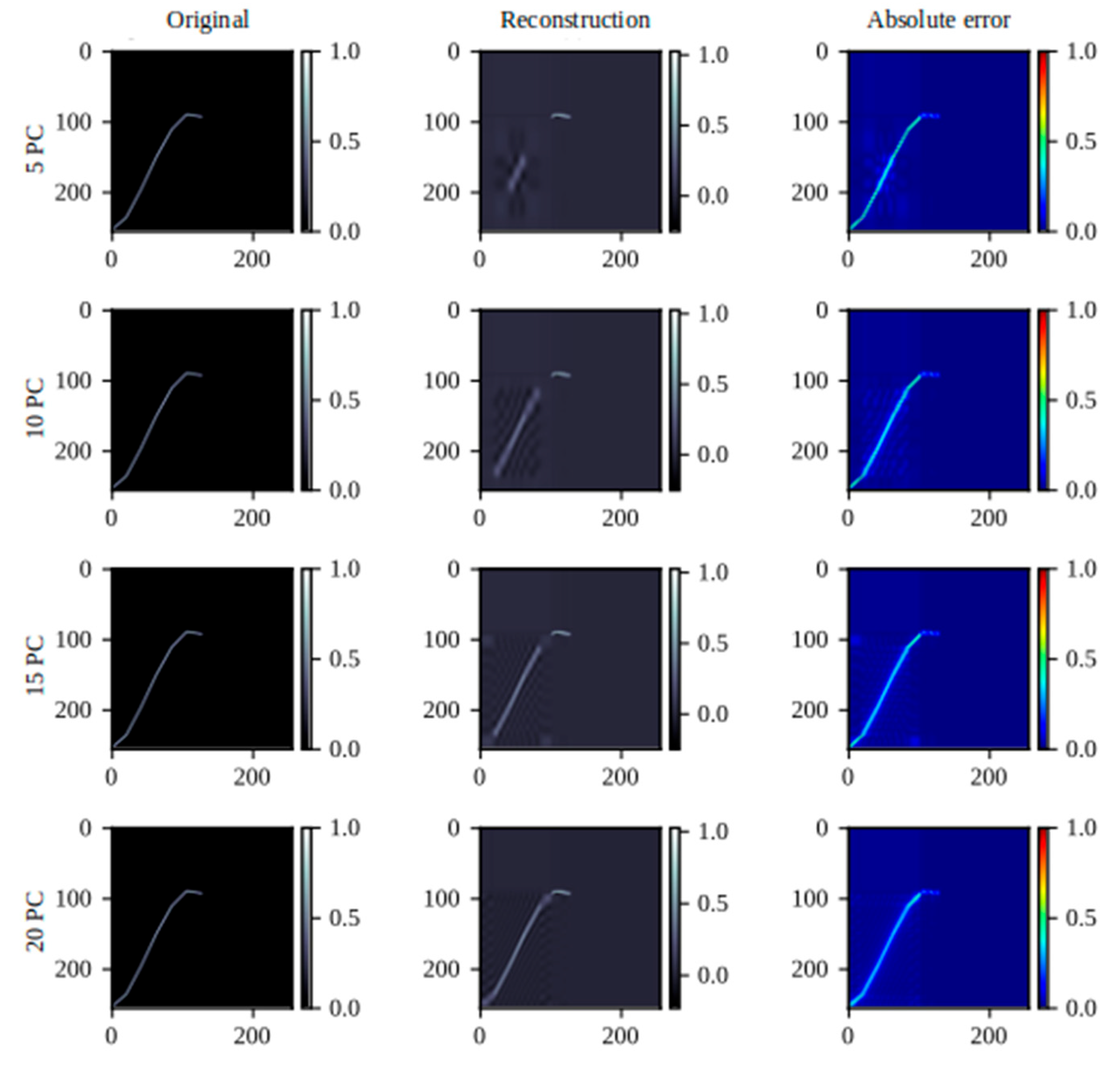

Figure 17.

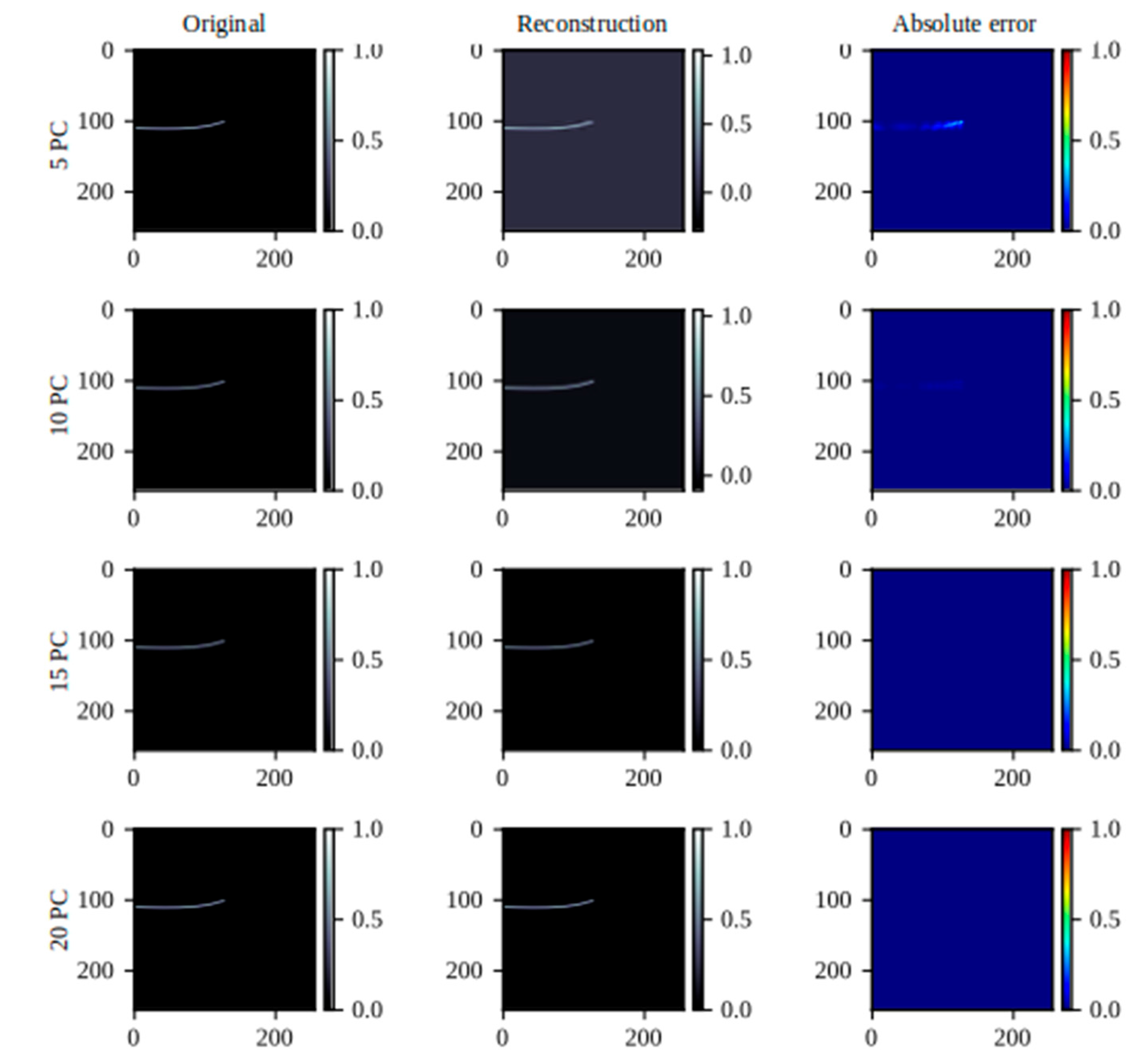

Reconstruction of the graph of cl1.5/cd vs α by PCA using different number of PCs.

Figure 17.

Reconstruction of the graph of cl1.5/cd vs α by PCA using different number of PCs.

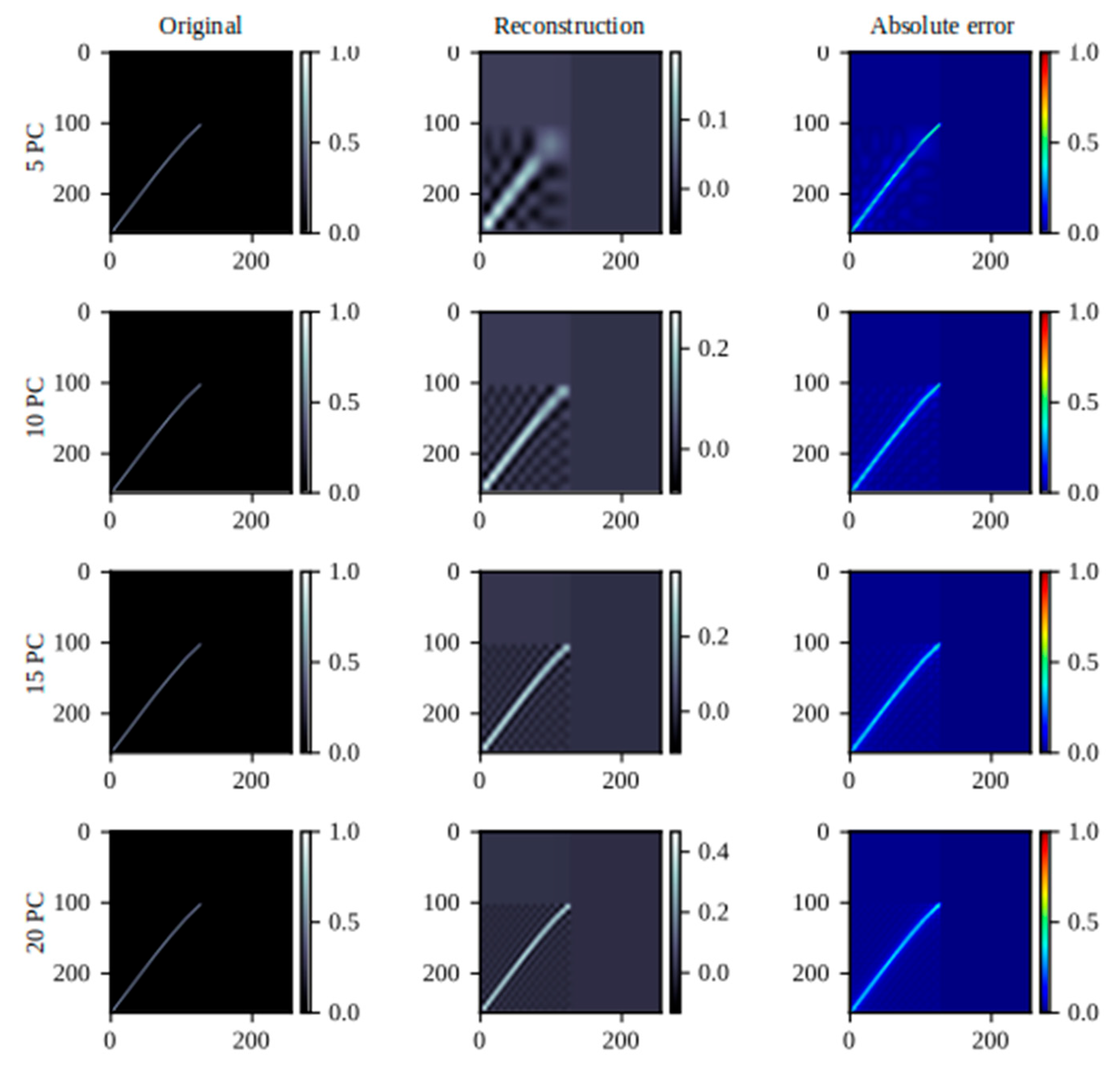

Figure 18.

Reconstruction of the graph of cm vs α by PCA using different number of PCs.

Figure 18.

Reconstruction of the graph of cm vs α by PCA using different number of PCs.

Figure 19.

Reconstruction of the graph of cl vs α by PCA using different number of PCs.

Figure 19.

Reconstruction of the graph of cl vs α by PCA using different number of PCs.

Figure 20.

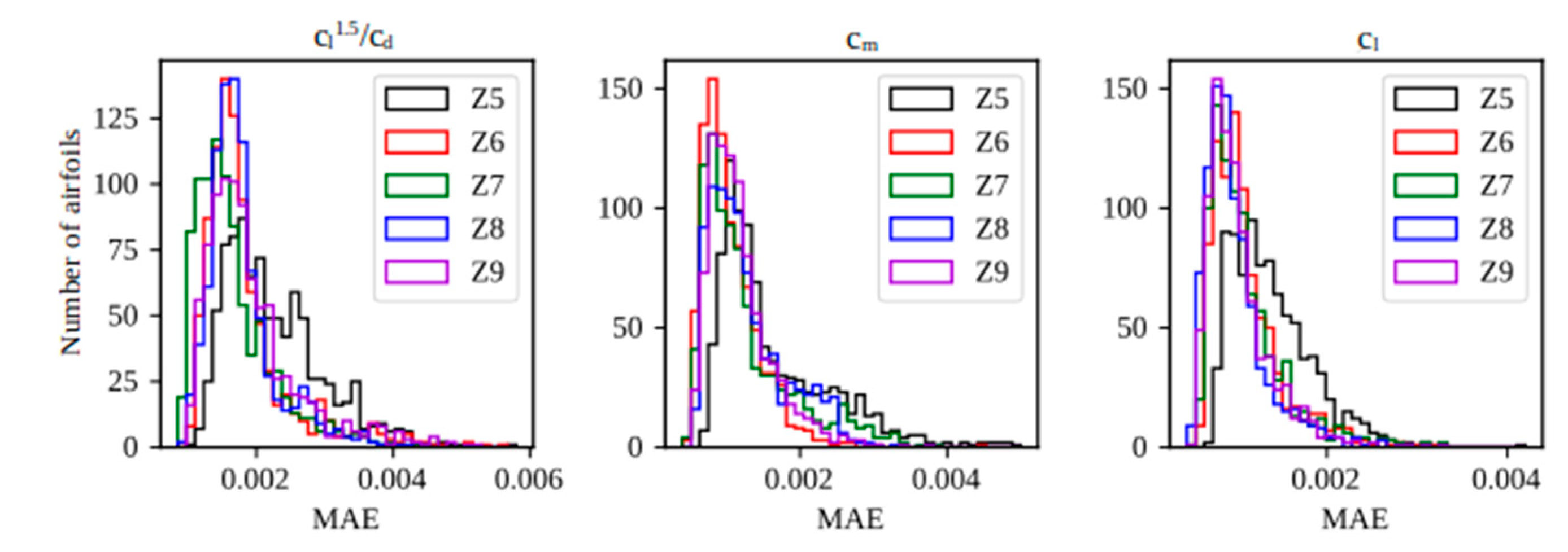

Statistical distribution of MAE in the reconstruction of graphs with a VAE. Stage of training.

Figure 20.

Statistical distribution of MAE in the reconstruction of graphs with a VAE. Stage of training.

Figure 21.

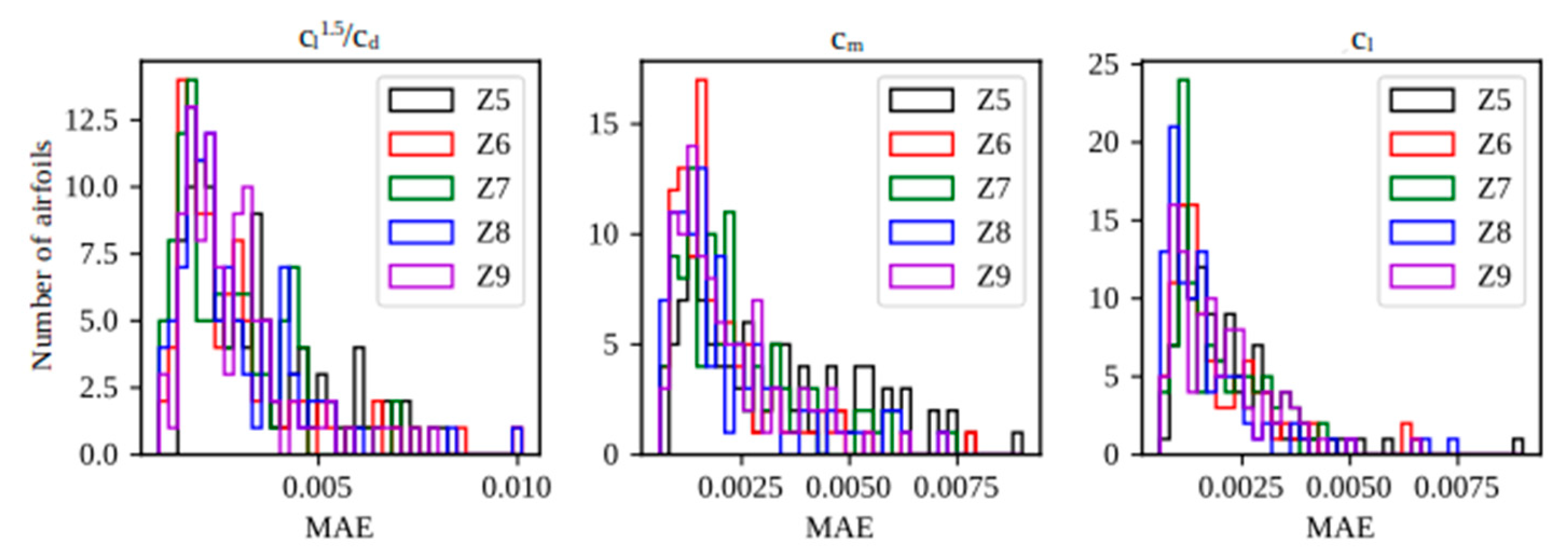

Statistical distribution of MAE in the reconstruction of graphs with a VAE. Stage of testing.

Figure 21.

Statistical distribution of MAE in the reconstruction of graphs with a VAE. Stage of testing.

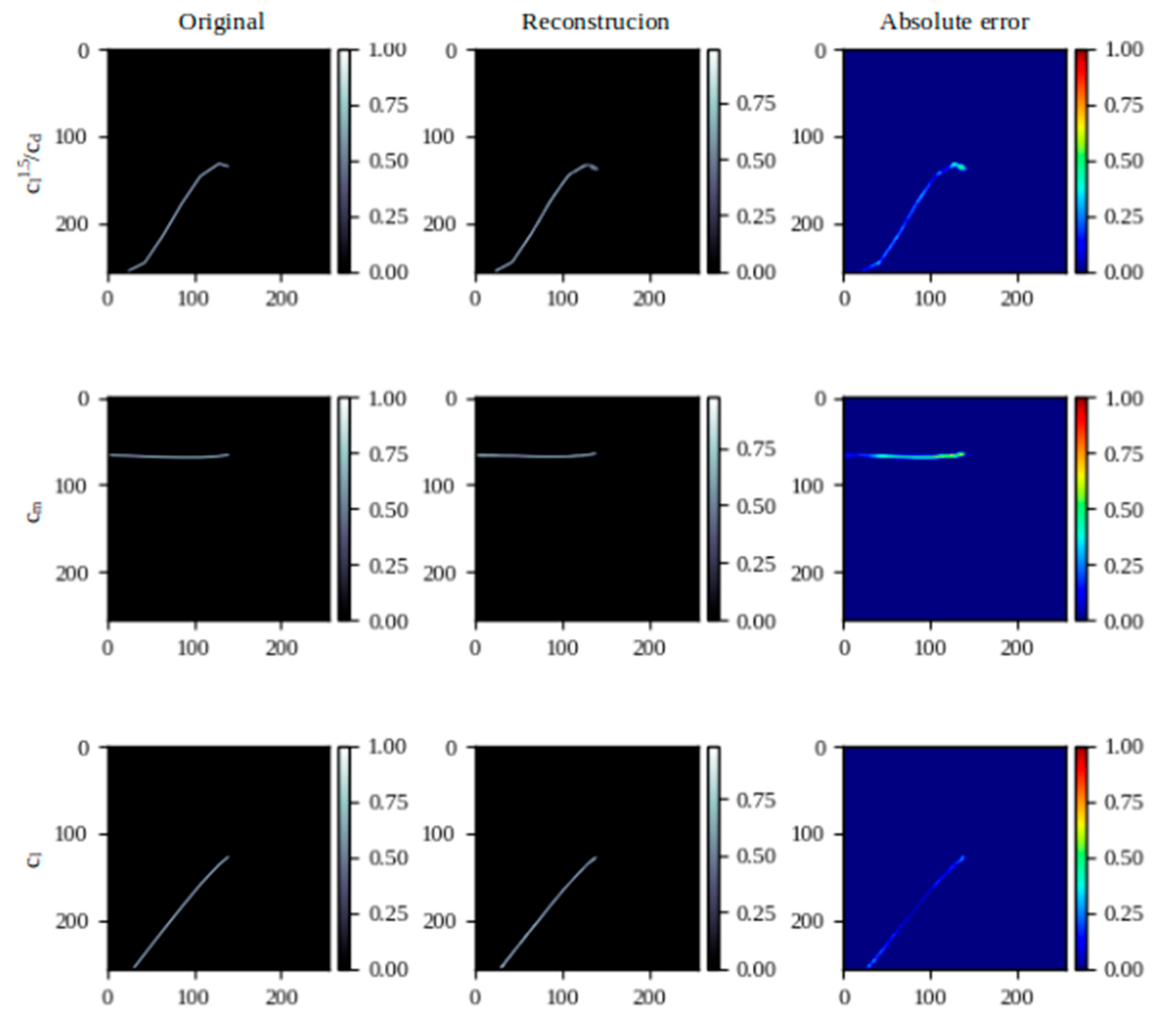

Figure 22.

Reconstruction of the graphs of the aerodynamic coefficients of the Eppler 502 airfoil (Re = 1.5x106, M = 0.15).

Figure 22.

Reconstruction of the graphs of the aerodynamic coefficients of the Eppler 502 airfoil (Re = 1.5x106, M = 0.15).

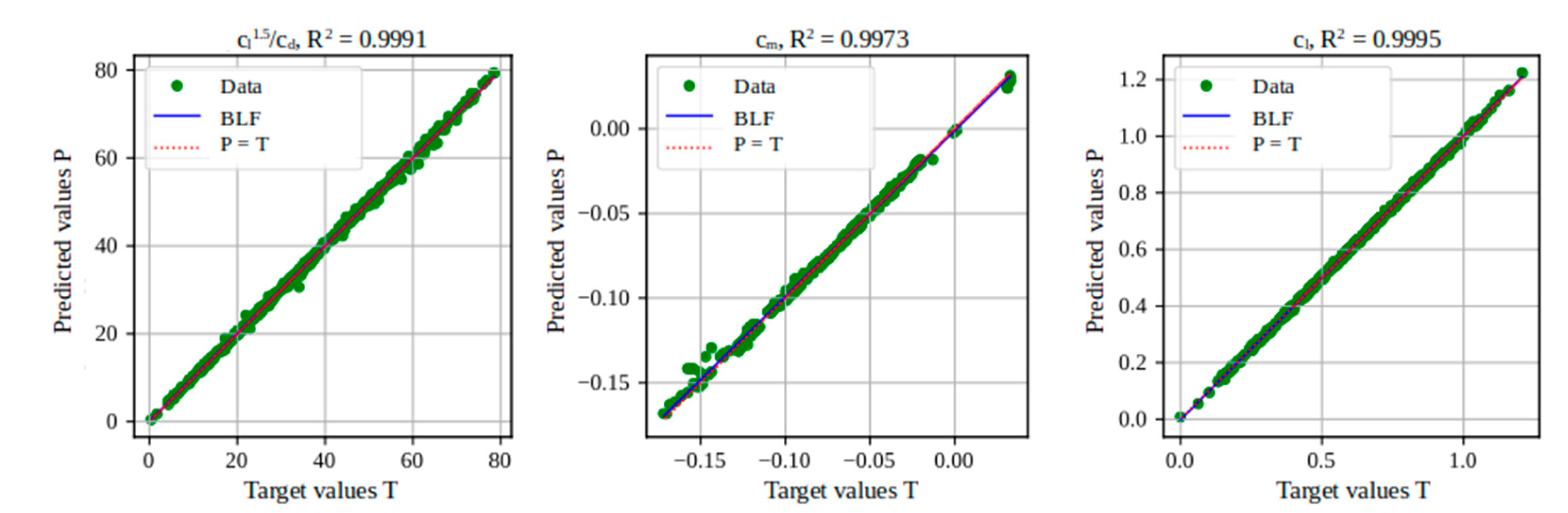

Figure 23.

Analysis of the performance in the reading of aerodynamic coefficients in the graphs reconstructed by the VAE.

Figure 23.

Analysis of the performance in the reading of aerodynamic coefficients in the graphs reconstructed by the VAE.

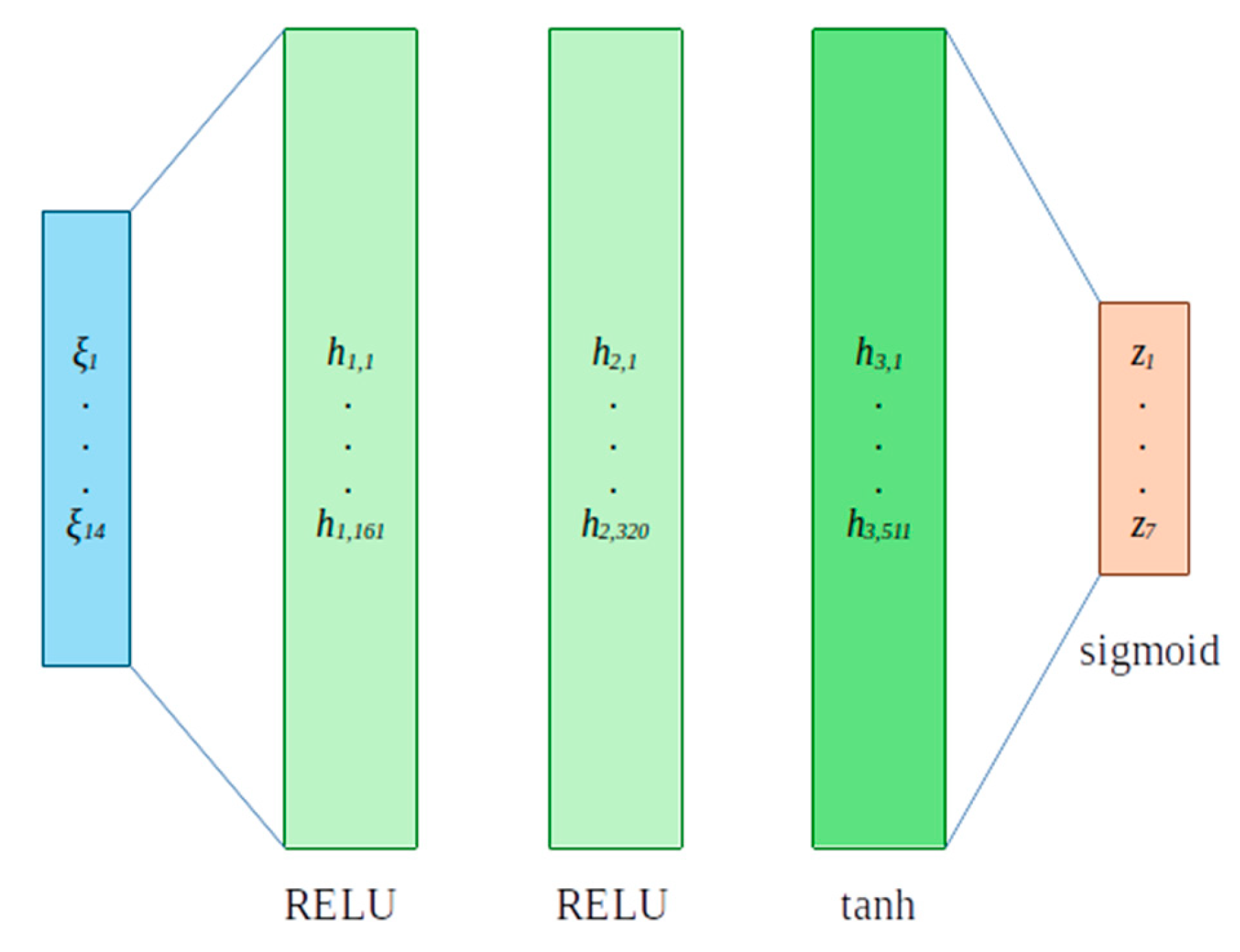

Figure 24.

The Architecture of MLP.

Figure 24.

The Architecture of MLP.

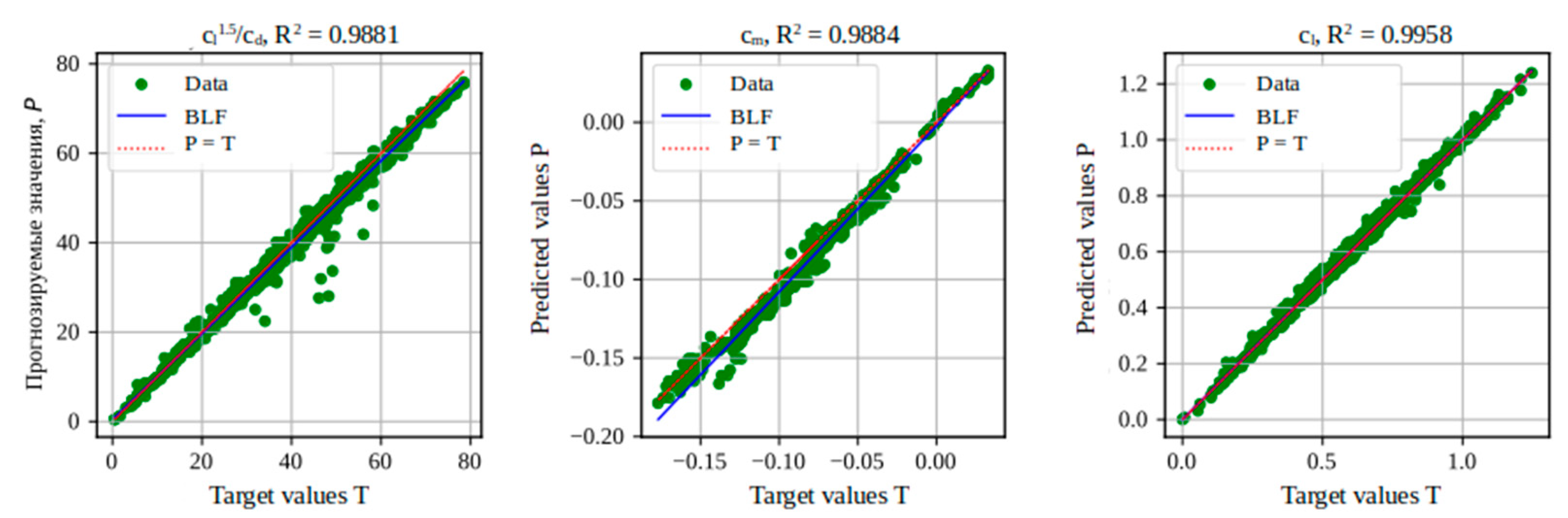

Figure 25.

Performance analysis in predicting aerodynamic coefficients using AZTLI-NN (1000 data).

Figure 25.

Performance analysis in predicting aerodynamic coefficients using AZTLI-NN (1000 data).

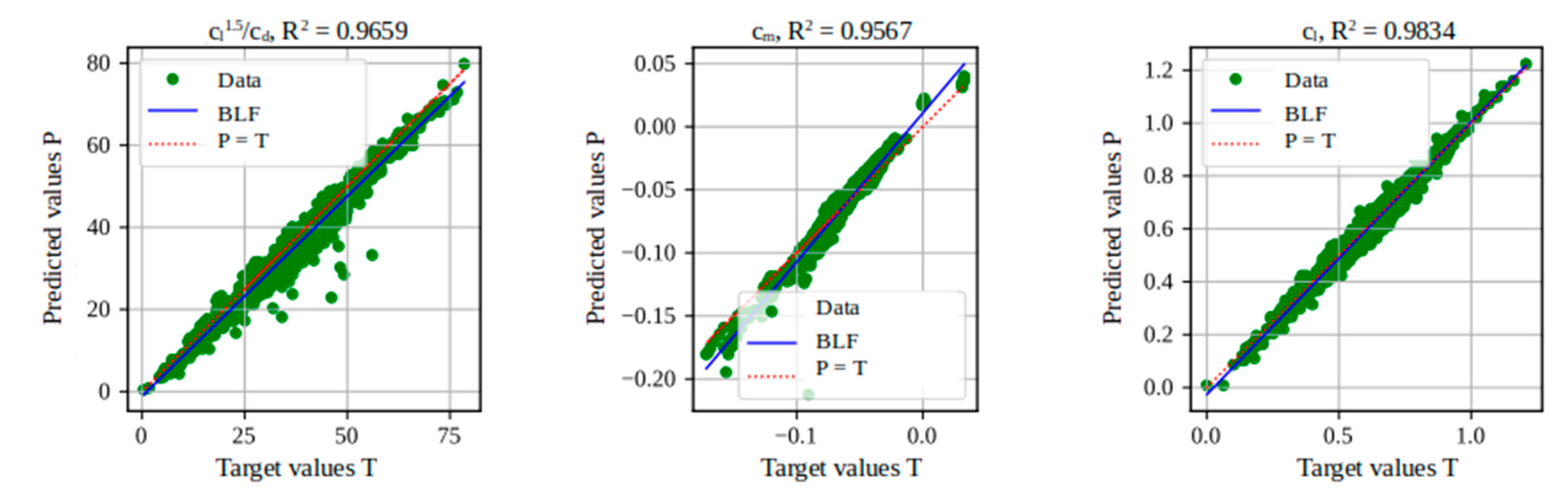

Figure 26.

Performance analysis in predicting aerodynamic coefficients using AZTLI-NN (1500 data).

Figure 26.

Performance analysis in predicting aerodynamic coefficients using AZTLI-NN (1500 data).

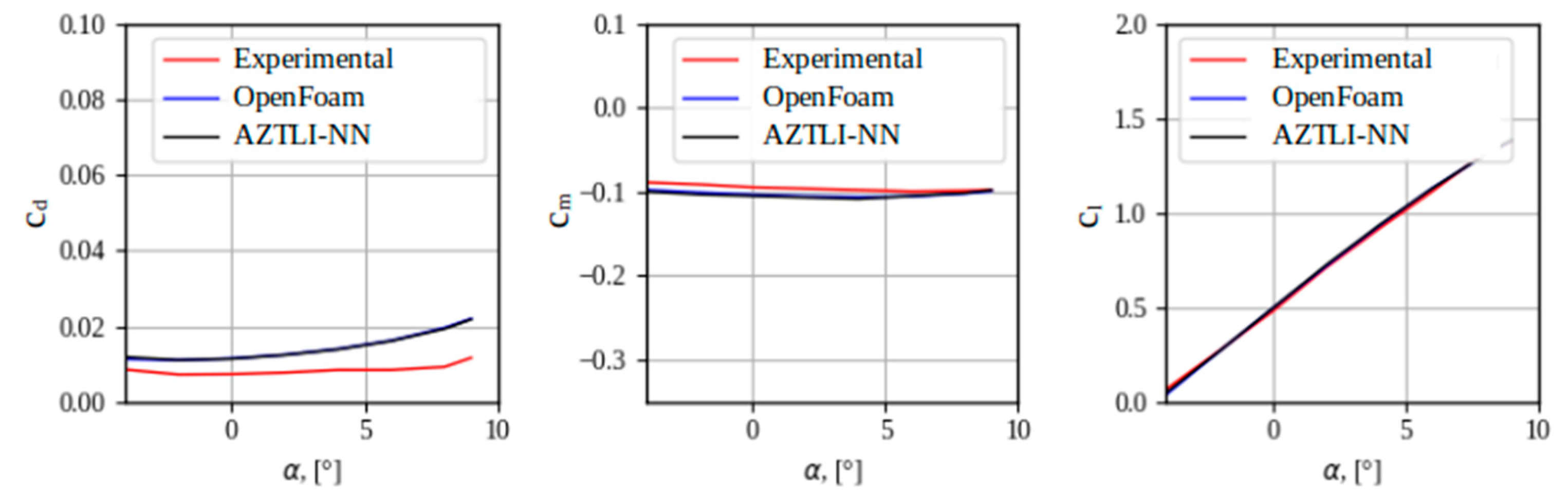

Figure 27.

Aerodynamic coefficients of the FX 66-S-161 profile obtained with a laminar wind tunnel, with OpenFOAM and with AZTLI-NN.

Figure 27.

Aerodynamic coefficients of the FX 66-S-161 profile obtained with a laminar wind tunnel, with OpenFOAM and with AZTLI-NN.

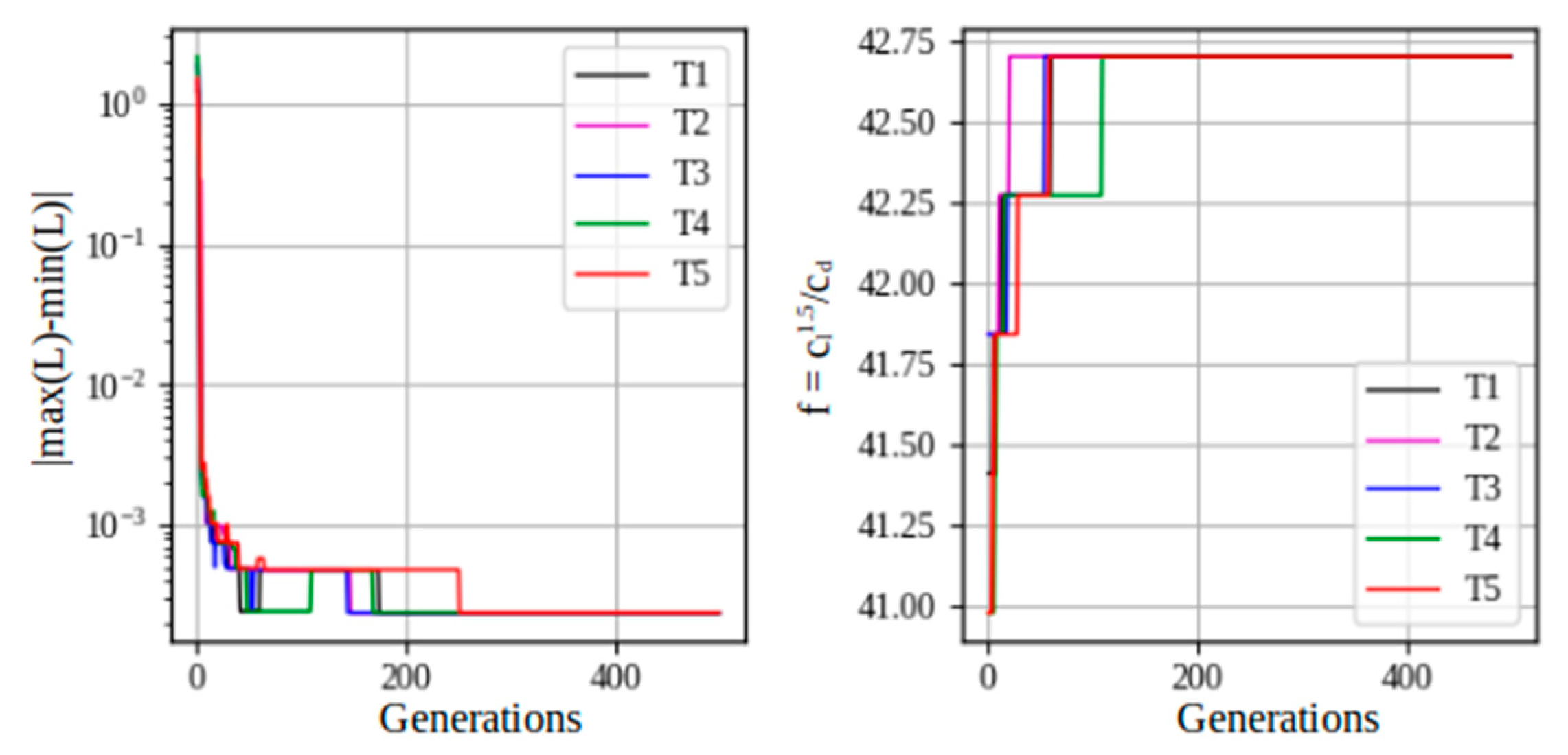

Figure 28.

Convergence analysis of the CAPR-SHADE algorithm.

Figure 28.

Convergence analysis of the CAPR-SHADE algorithm.

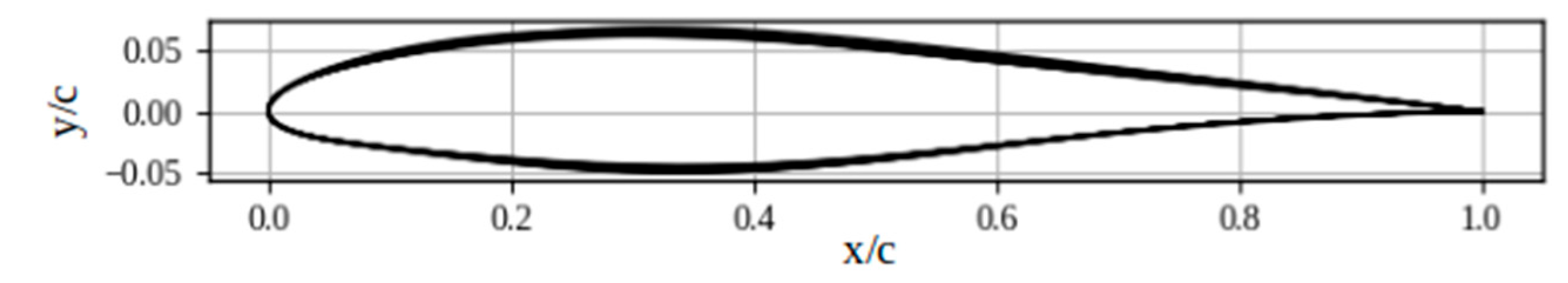

Figure 29.

Optimal airfoils obtained in different tests.

Figure 29.

Optimal airfoils obtained in different tests.

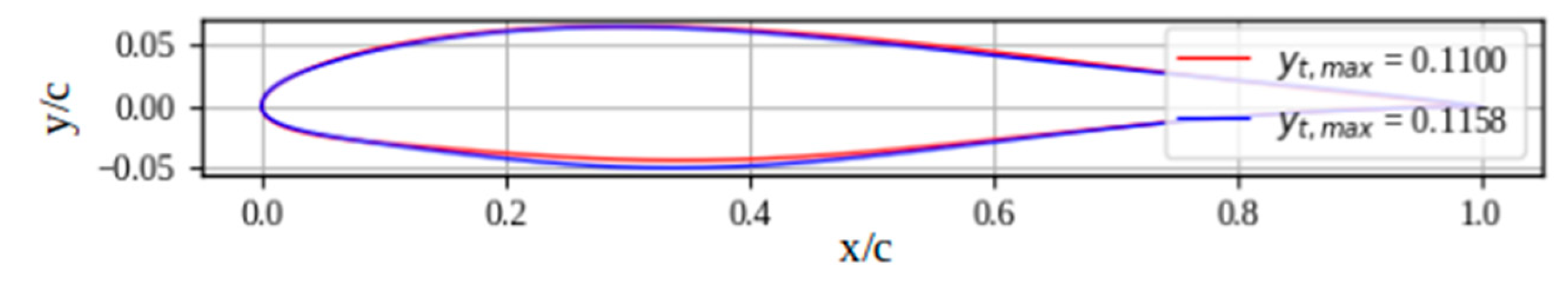

Figure 30.

Optimal airfoils with maximum and minimum ytmax.

Figure 30.

Optimal airfoils with maximum and minimum ytmax.

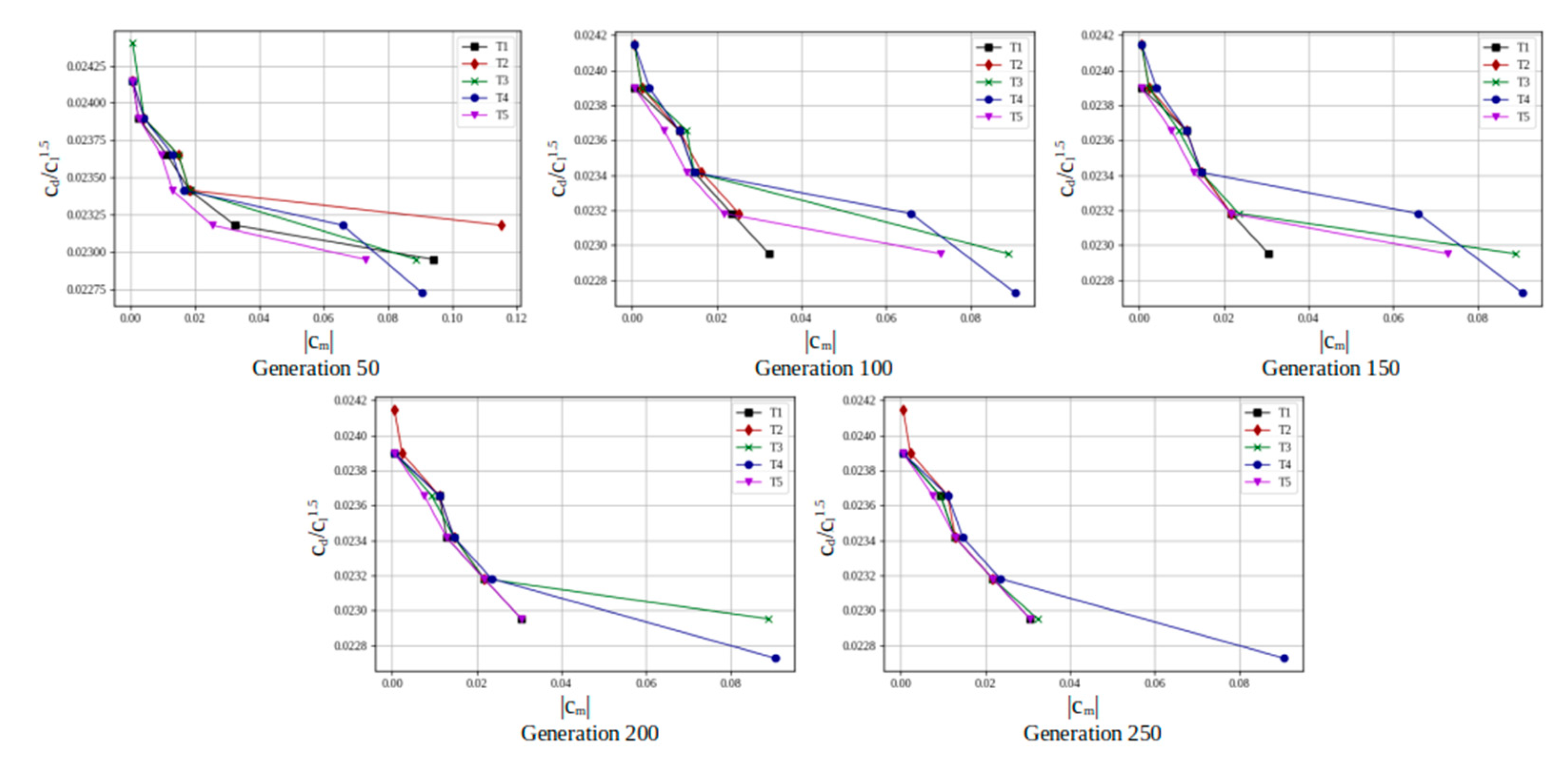

Figure 31.

Evolution of the Pareto front of the 5 optimization tests.

Figure 31.

Evolution of the Pareto front of the 5 optimization tests.

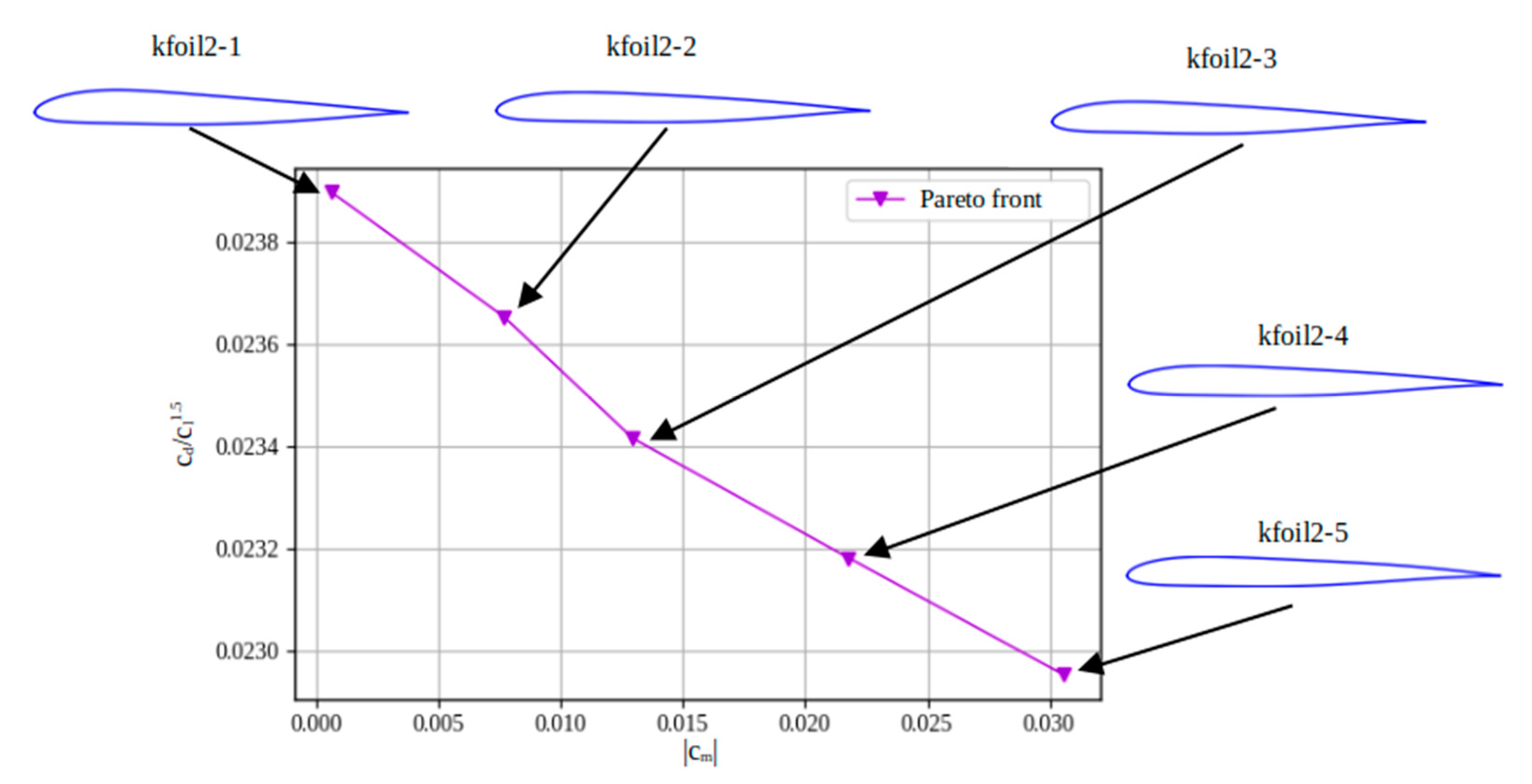

Figure 32.

Best Pareto front obtained in the tests.

Figure 32.

Best Pareto front obtained in the tests.

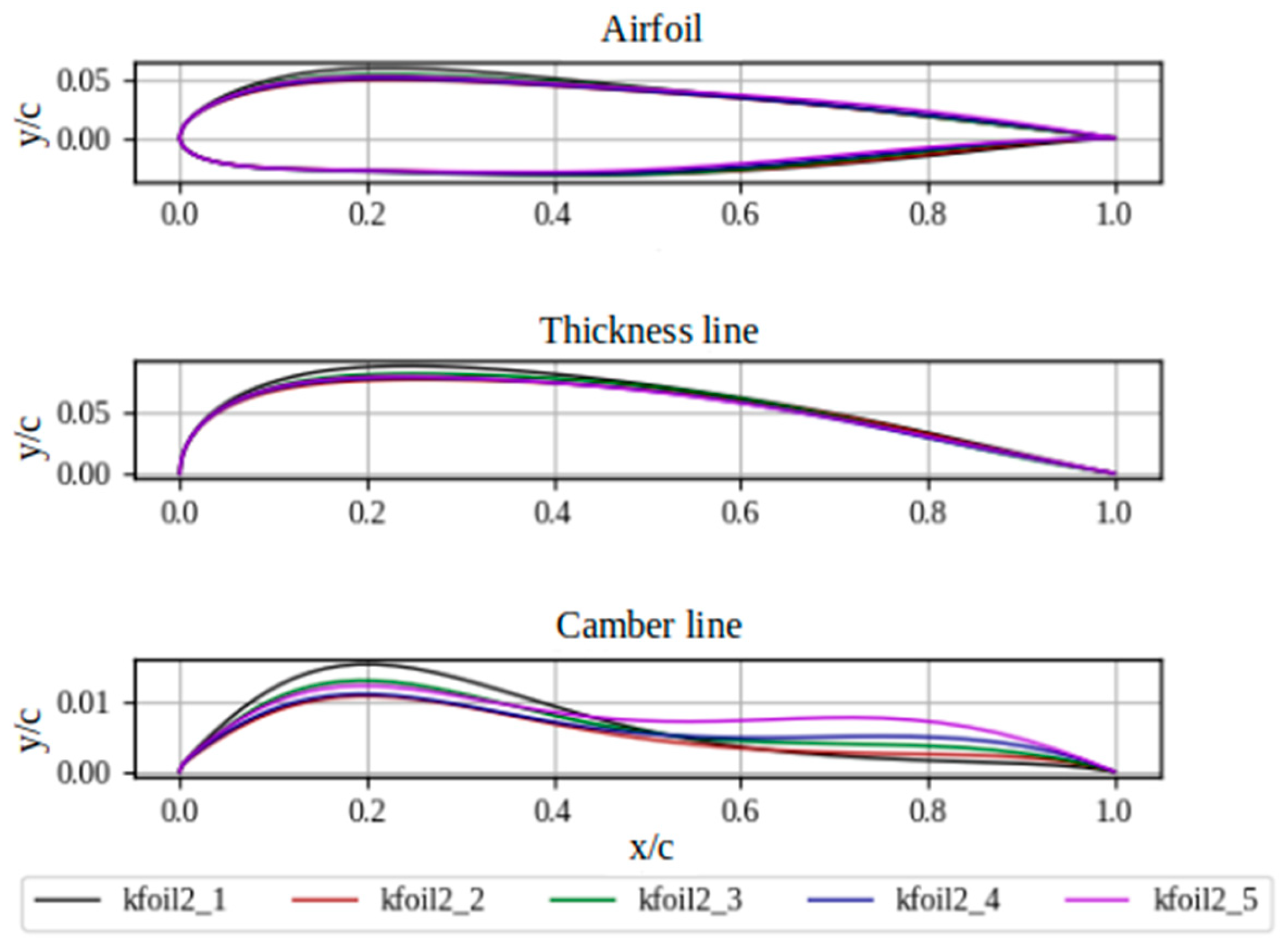

Figure 33.

Comparison of the geometries of the Pareto front profiles.

Figure 33.

Comparison of the geometries of the Pareto front profiles.

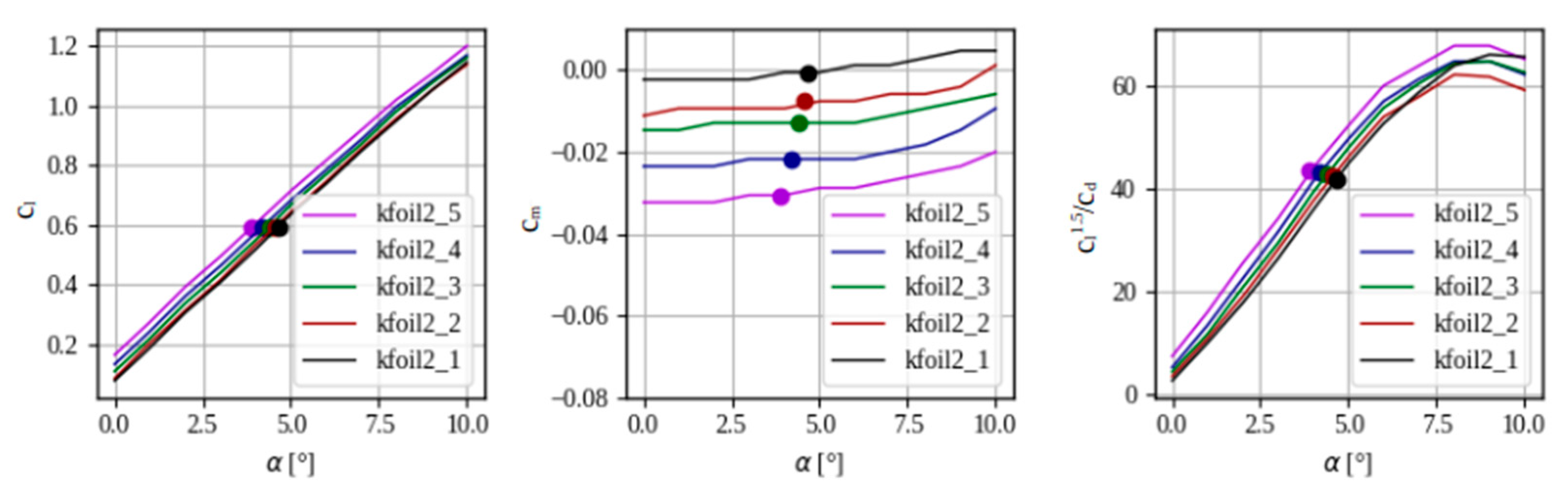

Figure 34.

Aerodynamic comparison of the Pareto front airfoils.

Figure 34.

Aerodynamic comparison of the Pareto front airfoils.

Table 1.

Initial conditions.

Table 1.

Initial conditions.

| |

airfoil |

inlet |

outlet |

frontBack |

internalField |

| U [m/s] |

noSlip |

U∞ |

U∞ |

empty |

U∞ |

| p [m2/s2] |

zeroGradient |

zeroGradient |

0 |

empty |

0 |

| k [m2/s2] |

kqRWallFunction(k0) |

k0 |

k0 |

empty |

k0 |

| ω [1/s] |

omegaWallFunction(ω0) |

ω0 |

ω0 |

empty |

ω0 |

| νt [m2/s] |

nutUWallFunction(0) |

0 |

0 |

empty |

0 |

Table 2.

List of schemes used [

19,

22].

Table 2.

List of schemes used [

19,

22].

| Type of scheme |

OpenFOAM scheme |

| Temporary derivatives |

steadyState |

| Gradients |

Gauss linear |

| Divergence(φ, U) |

bounded Gauss linearUpwind limited |

| Divergence(φ, k) |

bounded Gauss upwind |

| Divergence(φ, ω) |

bounded Gauss upwind |

| Laplacians |

Gauss linear corrected |

| Interpolation |

linear |

Table 3.

Design intervals of the parameters of the CST method.

Table 3.

Design intervals of the parameters of the CST method.

| Parameter |

Design interval |

Parameter |

Design interval |

| Au,0

|

[0,07, 0,35] |

Al,0

|

[-0,30, -0,05] |

| Au,1

|

[0,04, 0,55] |

Al,1

|

[-0,26, 0,05] |

| Au,2

|

[0,00, 0,45] |

Al,2

|

[-0,36, 0,05] |

| Au,3

|

[0,00, 0,55] |

Al,3

|

[-0,47, 0,05] |

| Au,4

|

[0,00, 0,55] |

Al,4

|

[-0,47, 0,05] |

| Au,5

|

[0,00, 0,50] |

Al,5

|

[-0,42, 0,10] |

| Au,6

|

[-0,01, 0,50] |

Al,6

|

[-0,28, 0,10] |

Table 4.

Design intervals of the parameters of the Bezier-PARSEC method.

Table 4.

Design intervals of the parameters of the Bezier-PARSEC method.

| Parameter |

Design interval |

Parameter |

Design interval |

| rle

|

[-0.030, -0.001] |

γle

|

[-0,01, 0,32] |

| xt

|

[0,23, 0,50] |

xc

|

[0,20, 0,85] |

| yt

|

[0,030, 0,095] |

yc

|

[0,010, 0,065] |

| kt

|

[-0.9, -0.2] |

kc

|

[-1,000, 0,025] |

| βte

|

[0,01, 0,40] |

αte

|

[0,01, 0,70] |

Table 5.

Generator (G).

| Layer |

Number of neurons |

Activation function |

| Input layer, IL |

5 |

————————— |

| Hidden layer 1, HL1 |

16 |

Leaky RELU |

| Hidden layer 2, HL2 |

32 |

Leaky RELU |

| Output layer, OL |

14 |

Hyperbolic tangent |

Table 6.

Discriminator (D).

Table 6.

Discriminator (D).

| Layer |

Number of neurons |

Activation function |

| Input layer, IL |

14 |

————————— |

| Hidden layer 1, HL1 |

32 |

Leaky RELU |

| Hidden layer 2, HL2 |

16 |

Leaky RELU |

| Output layer, OL |

1 |

Sigmoid |

Table 7.

Characteristics of the simulated flows in the NACA 0012 airfoil.

Table 7.

Characteristics of the simulated flows in the NACA 0012 airfoil.

| Test |

M [Re] |

| 1 |

0.15 [2x106] |

| 2 |

0.15 [4x106] |

| 3 |

0.15 [6x106] |

| 4 |

0.30 [4x106] |

| 5 |

0.30 [6x106] |

Table 8.

Average values of MAE in the reconstruction of graphs in the VAE testing stage.

Table 8.

Average values of MAE in the reconstruction of graphs in the VAE testing stage.

| Size of z |

MAE |

MAEavg

|

| cl1.5/cd

|

cm

|

cl

|

| 9 |

0.00291 |

0.00218 |

0.00196 |

0.00235 |

| 8 |

0.00283 |

0.00220 |

0.00165 |

0.00223 |

| 7 |

0.00281 |

0.00223 |

0.00185 |

0.00223 |

| 6 |

0.00294 |

0.00203 |

0.00199 |

0.00232 |

| 5 |

0.00341 |

0.00331 |

0.00212 |

0.00294 |

Table 9.

Parameters and their design ranges to optimize MLP hyperparameters.

Table 9.

Parameters and their design ranges to optimize MLP hyperparameters.

| η |

Design ranges |

| n1

|

[128; 512] |

| n2

|

| n3

|

| a1

|

{0; 1; 2}* |

| a2

|

| a3

|

Table 10.

Repeatability analysis of the obtained values obtained by the optimization algorithm.

Table 10.

Repeatability analysis of the obtained values obtained by the optimization algorithm.

| NP0 |

Test |

cl1.5/cd |

α [°] |

ytmax |

cd |

cm |

10|ξ|

|

1 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1127 |

0.0106 |

-0.0342 |

| 2 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1102 |

0.0106 |

-0.0342 |

| 3 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1136 |

0.0106 |

-0.0323 |

| 4 |

42.2745 |

3.9 |

0.1148 |

0.0107 |

-0.0342 |

| 5 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1100 |

0.0106 |

-0.0323 |

20|ξ|

|

1 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1148 |

0.0106 |

-0.0341 |

| 2 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1136 |

0.0106 |

-0.0376 |

| 3 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1117 |

0.0106 |

-0.0341 |

| 4 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1118 |

0.0106 |

-0.0341 |

| 5 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1122 |

0.0106 |

-0.0341 |

50|ξ|

|

1 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1158 |

0.0106 |

-0.0341 |

| 2 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1117 |

0.0106 |

-0.0341 |

| 3 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1113 |

0.0106 |

-0.0359 |

| 4 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1127 |

0.0106 |

-0.0341 |

| 5 |

42.7059 |

3.9 |

0.1104 |

0.0106 |

-0.0359 |

Table 11.

Comparison of the aerodynamic coefficients of optimal profiles obtained using OpenFOAM and AZTLI-NN.

Table 11.

Comparison of the aerodynamic coefficients of optimal profiles obtained using OpenFOAM and AZTLI-NN.

| Airfoil |

Method |

α [°] |

cl |

cd |

cm |

cl1.5/cd |

yt,max |

| Kfoil_1 |

OpenFOAM |

3,9 |

0,5847 |

0,0109 |

-0,0293 |

41,0178 |

0,1100 |

| Kfoil_1 |

AZTLI-NN |

3,9 |

0,59 |

0,0106 |

-0,0323 |

42,7059 |

0,1100 |

| Kfoil_2 |

OpenFOAM |

3,9 |

0,5801 |

0,0110 |

-0,0303 |

40,1662 |

0,1158 |

| Kfoil_2 |

AZTLI-NN |

3,9 |

0,59 |

0,0106 |

-0,0341 |

42,7059 |

0,1158 |

Table 12.

Aerodynamic characteristics of the Pareto front profiles under the condition of design.

Table 12.

Aerodynamic characteristics of the Pareto front profiles under the condition of design.

| Airfoil |

α [°] |

cl

|

cd

|

cm

|

cl1,5/cd

|

yс,max

|

yt,max

|

| kfoil2_1 |

4,6 |

0,5900 0,5933* |

0,0109 0,0110* |

-0,0006 -0,0029* |

41,5431 41,5450* |

0,0154 |

0,0888 |

| kfoil2_2 |

4,5 |

0,5900 0,5907* |

0,0107 0,0108* |

-0,0079 -0,0117* |

42,2745 42,0365* |

0,0108 |

0,0776 |

| kfoil2_3 |

4,3 |

0,5900 0,5905* |

0,0106 0,0107* |

-0,0129 -0,0150* |

42,7059 42,4078* |

0,0130 |

0,0823 |

| kfoil2_4 |

4,1 |

0,5900 0,5878* |

0,0105 0,0107 |

-0,0218 -0,0231* |

43,1373 42,5146* |

0,0111 |

0,0791 |

| kfoil2_5 |

3,9 |

0,5900 0,5930* |

0,0104 0,0106* |

-0,0305 -0,0303* |

43,5686 43,0800* |

0,0123 |

0,0800 |