Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

24 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

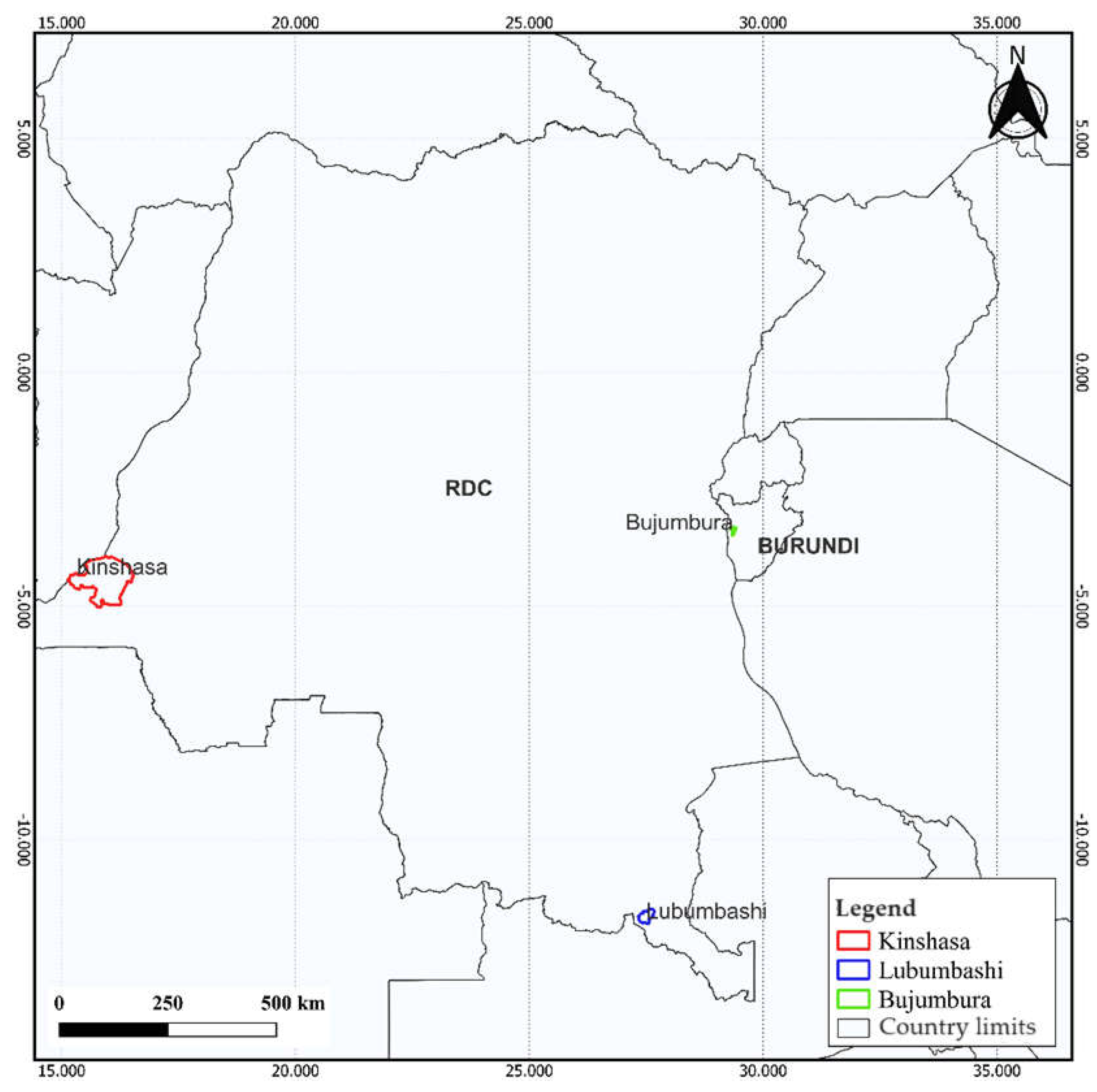

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Selection of Satellite Images.

2.3. Image pre-Processing, Processing and Classification

2.4. Calculation of Spatial Pattern Indices and Detection of Landscape Dynamics

2.5. Vegetation Index

3. Results

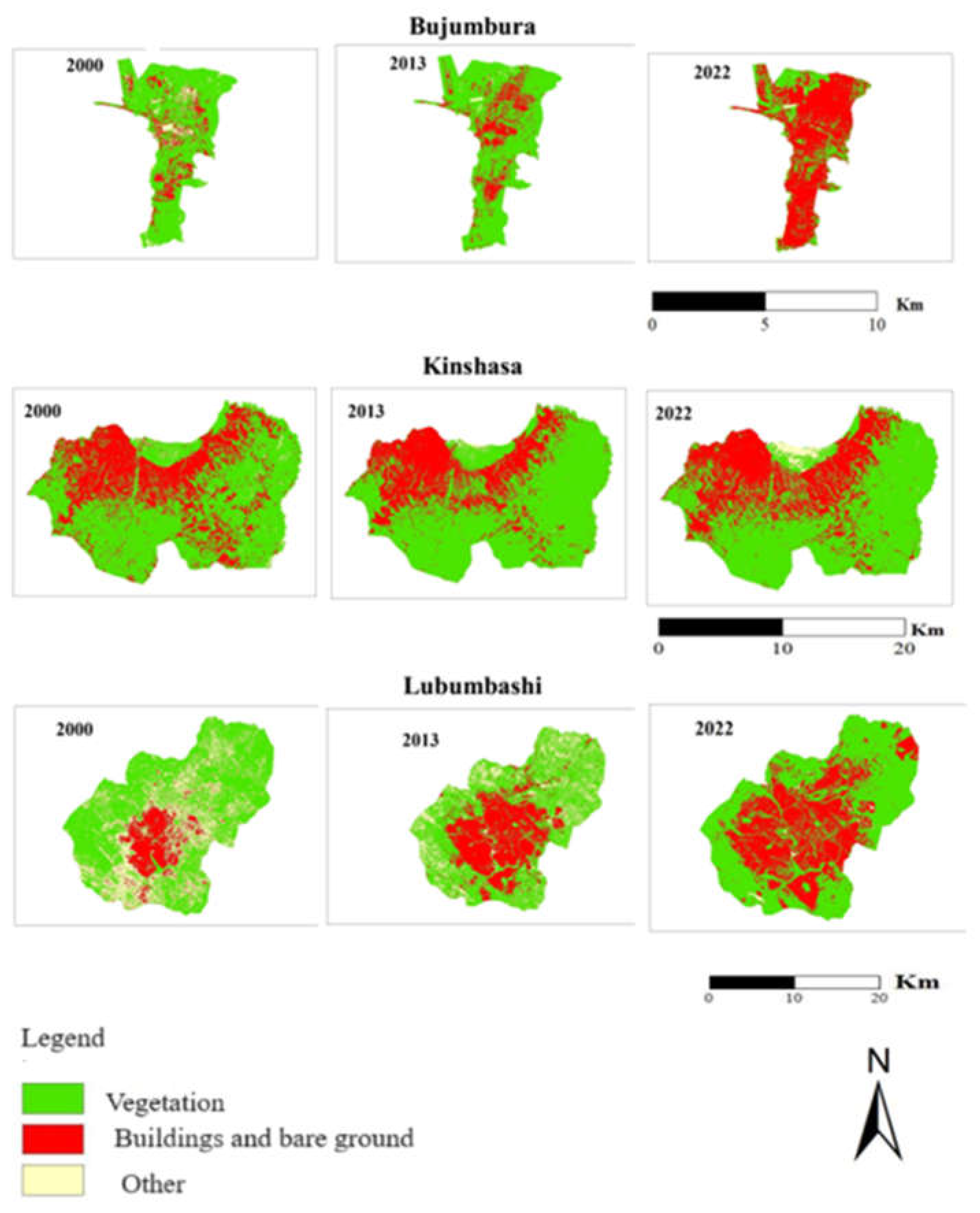

3.1. Satellite Data Analysis: Classification and Mapping (2000 to 2022)

3.2. Changes in Land Use between 2000 and 2022

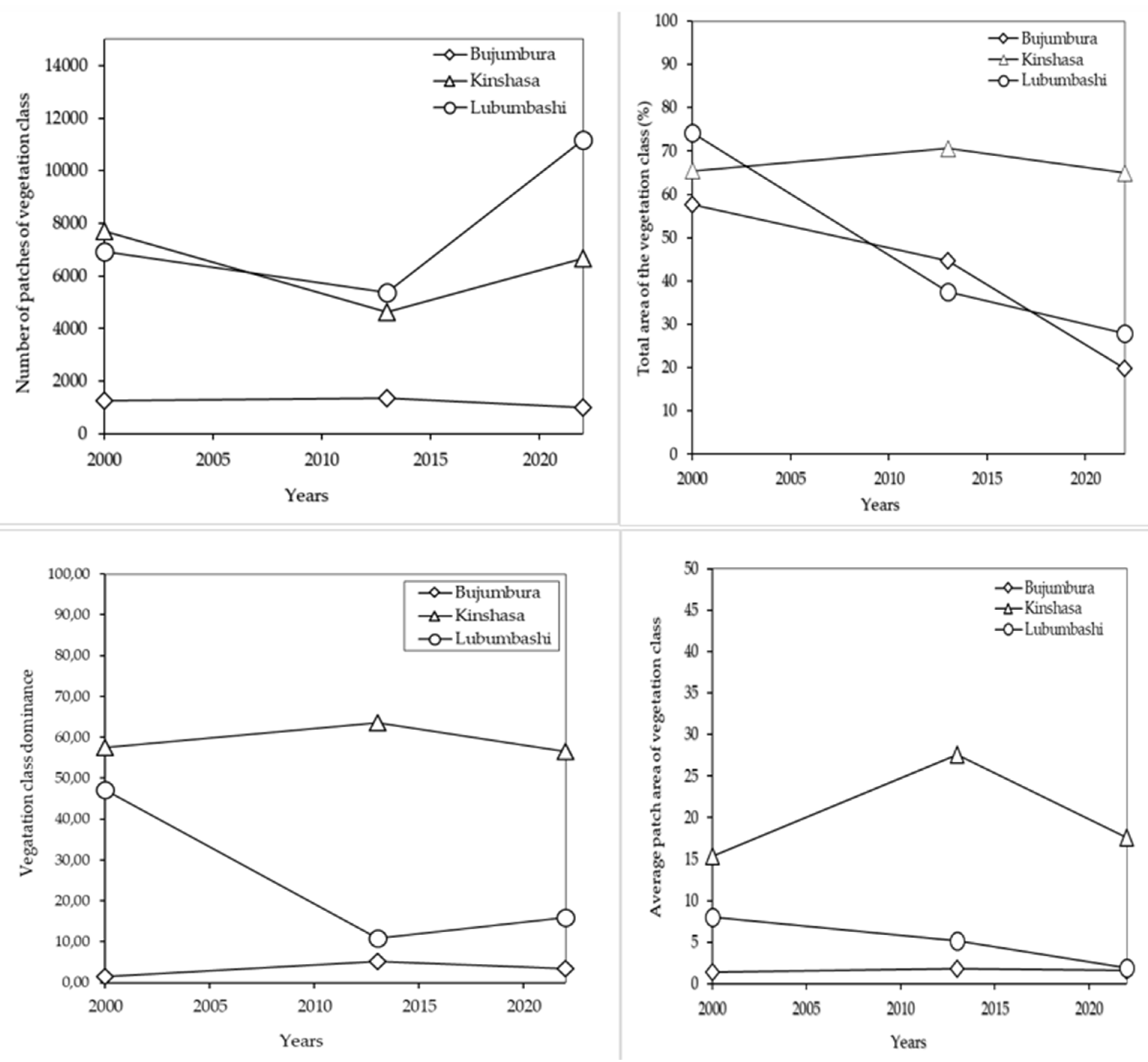

3.3. Dynamics of the Spatial Structure of Vegetation

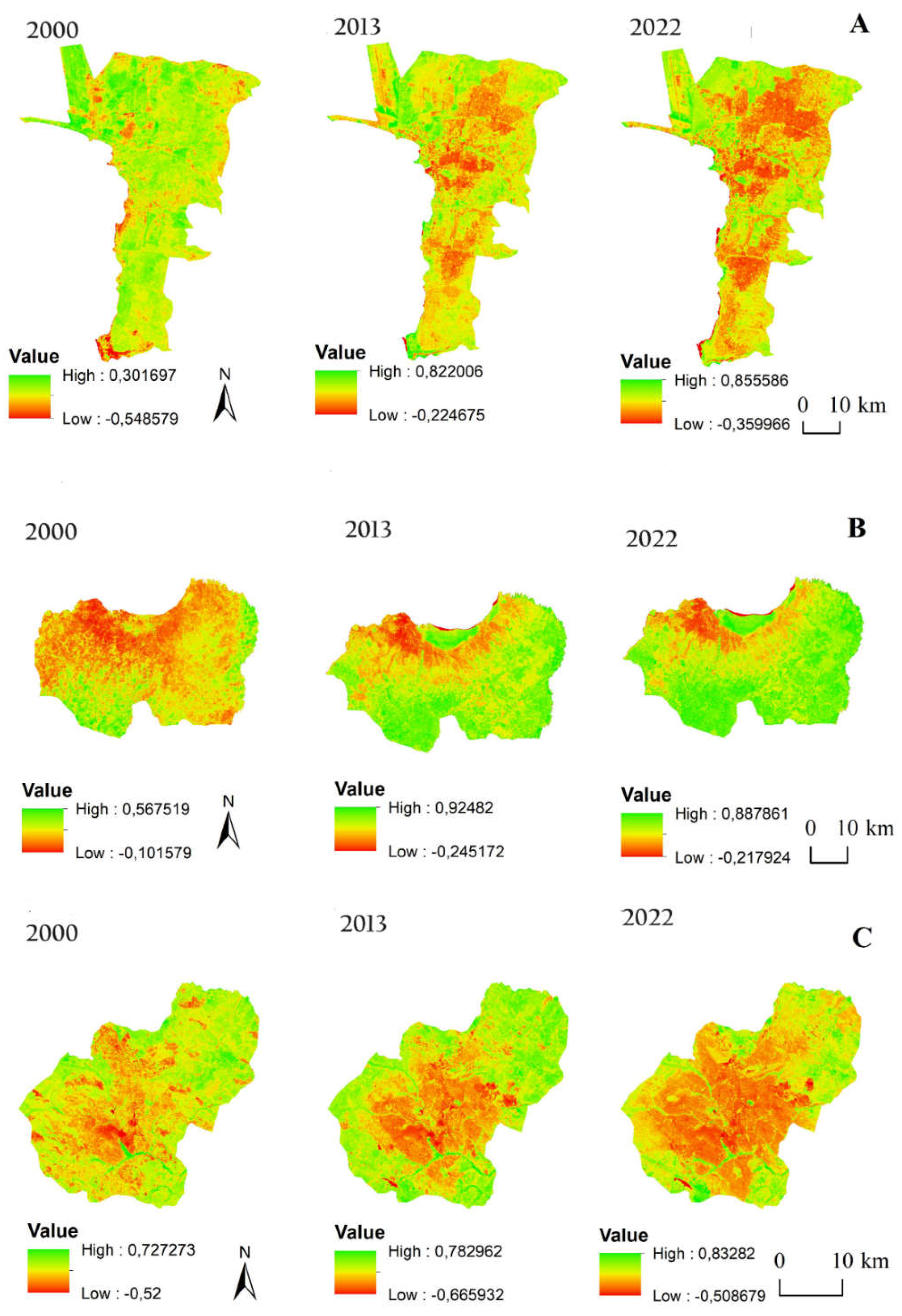

3.4. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Approach

4.2. Spatial Structure Indices

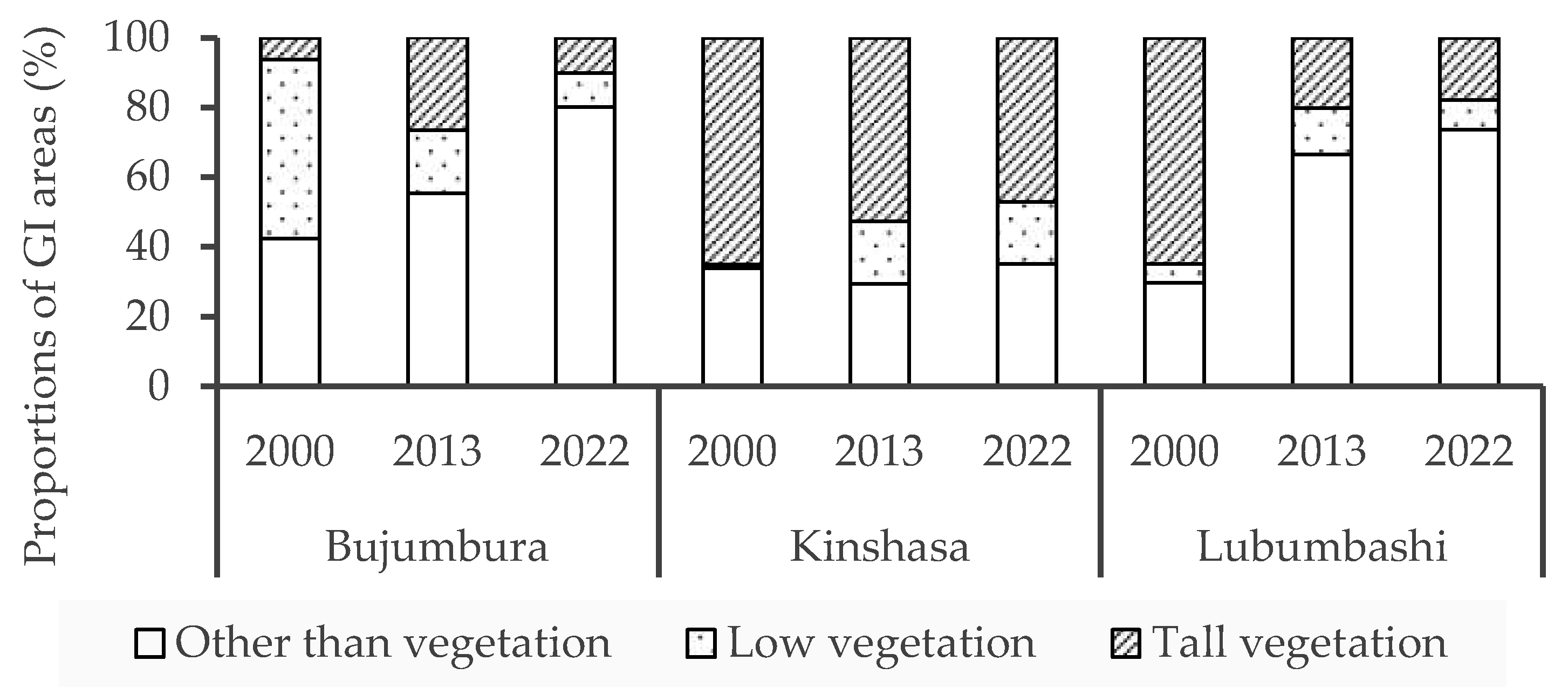

4.3. Standardized Differential Vegetation Index and Green Infrastructure Composition Dynamics

4.4. Urbanization and Loss of Natural Cover in the Cities of Bujumbura, Kinshasa and Lubumbashi

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD/CSAO. Cahiers de l’Afrique de l’Ouest: Dynamiques de l’urbanisation Africaine 2020: Africapolis, Une Nouvelle Géographie urbaine, Cahiers de l'Afrique de l'Ouest; Editions OCDE, Paris; 2020; ISBN 9789264349025.

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D.L.; Blei, A.; Potere, D. The Dimensions of Global Urban Expansion: Estimates and Projections for All Countries, 2000-2050. Prog. Plann. 2011, 75, 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal. The End of Population Growth. Deu. Ban. 2011, 1–13.

- Halleux, J.-M. Les Territoires Périurbains et Leur Développement Dans Le Monde : Un Monde En Voie d’urbanisation et de Périurbanisation. In Territoires périurbains: Développement, enjeux et Perspectives dans les pays du Sud ; Bogaert, J., Halleux, J.M., Eds.; Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gemblox, Belgium, 2015, pp.43-61.

- Kabanyegeye, H.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Sambieni, K.R.; Masharabu, T.; Bogaert, J. Trente-Trois Ans de Dynamique Spatiale de l’occupation Du Sol de La Ville de Bujumbura, République Du Burundi. Afrique Sci. Rev. Int. des Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 203–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeiren, K.; Van Rompaey, A.; Loopmans, M.; Serwajja, E.; Mukwaya, P. Urban Growth of Kampala, Uganda: Pattern Analysis and Scenario Development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 106, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffler, A.; Swilling, M. Valuing Green Infrastructure in an Urban Environment under Pressure - The Johannesburg Case. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Vranken, I.; Andre, M. Biocultural Landscapes. Biocultural Landscapes 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, H.; Cormier, L. La Complexité de l ’ Application Du Concept d ’ Infrastructure Verte à l ’ Échelle Locale : Exemples de Paris et Porto. Urbanités biodiversité. Entre villes fertiles campagnes urbaines, quelle place pour la biodiversité ? 2017, Hal-01597292.

- Osseni, A.A.; Mouhamadou, T.; Tohoain, B.A.C.; Sinsin, B. SIG et Gestion Des Espaces Verts Dans La Ville de Porto-Novo Au Benin. Tropicultura 2015, 332, 146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kaleba, S.C.; Khonde, C.N.; Mwana, Y.A.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Kankumbi, F.M. Vingt-Cinq Ans de Monitoring de La Dynamique Spatiale Des Espaces Verts En Réponse á l'Urbanisation Dans Les Communes de La Ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, R.D. Congo). Tropicultura 2017, 35, 300–311.

- du Toit, M.J.; Cilliers, S.S.; Dallimer, M.; Goddard, M.; Guenat, S.; Cornelius, S.F. Urban Green Infrastructure and Ecosystem Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambieni, K. R. , Sikuzani, Y. U., Kaleba, C., Moyene, A. B., Kankumbi, F. M., Nzuzi, F. L., Occhiuto, R, Bogaert, J. Les Espaces Verts En Zone Urbaine et Périurbaine de Kinshasa En République Démocratique Du Congo. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 478–491.

- Sikuzani, Y.U.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Maréchal, J.; Ilunga wa Ilunga, E.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K. F. Changes in the Spatial Pattern and Ecological Functionalities of Green Spaces in Lubumbashi (the Democratic Republic of Congo) in Relation With the Degree of Urbanization. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2018, 11, 194008291877132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanyegeye, H.; Masharabu, T.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Bogaert, J. Perception Sur Les Espaces Verts et Leurs Services Écosystémiques Par Les Acteurs Locaux de La Ville de Bujumbura (République Du Burundi). Tropicultura 2020, 38, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gashu, K.; Egziabher, T.G. Spatiotemporal Trends of Urban Land Use / Land Cover and Green Infrastructure Change in Two Ethiopian Cities : Bahir Dar and Hawassa. Environ. Syst. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomba, M.; Osunde, Z.D.; Sidi, S.; Okhimamhe, A.; Kleemann, J.; Fürst, C. Changes and Perceptions. L. 2024, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, Y.S.; Malaisse, F.; Yona, J.M.; Mwamba, T.M.; Bogaert, J. Diversity, Use and Management of Household-Located Fruit Trees in Two Rapidly Developing Towns in Southeastern D. R. Congo. Urb. For. Urb.Gr.. 2021, 63, 127220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.C.; Turner, R.N. Capital Cities: A Special Case in Urban Development. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2011, 46, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washbourne, C. Environmental Policy Narratives and Urban Green Infrastructure: Reflections from Five Major Cities in South Africa and the UK. Envir. Scie. & Pol. 2022,129, 96-106.

- Delgado-Capel, M.; Cariñanos, P. Towards a Standard Framework to Identify Green Infrastructure Key Elements in Dense Mediterranean Cities. Forests 2020, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, L.; Enqvist, J. Green Infrastructure in South African Cities. Report for CSP, African Centre for Cities, National Treasury, South Africa 2019.

- Useni, Y.S. Analyse Spatio-Temporelle Des Dynamiques d’anthropisation Paysagère Le Long Du Gradient Urbain-Rural de La Ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, République Démocratique Du Congo). Ph.D.Thesis, Université de Lubumbashi République Démocratique du Congo, 2017.

- Messina Ndzomo, J.P.; Sambieni, K.R.; Mbevo Fendoung, P.; Mate Mweru, J.P.; Bogaert, J.; Halleux, J.M. La Croissance De L’Urbanisation Morphologique À Kinshasa Entre 1979 Et 2015: Analyse Densimétrique Et De La Fragmentation Du Bâti. BSGLg 2019, 73, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigirimana, J. Urban Plant Diversity Patterns, Processes and Conservation Value in Sub-Saharan Africa: Case of Bujumbura in Burundi, Ph.D. Thesis, Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kabanyegeye, H.; Ndayishimiye, J.; Hakizimana, P.; Masharabu, T.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Diversité Floristique et Statut de Conservation Des Espaces Verts de La Ville de Bujumbura (Burundi) Floristic Diversity and Conservation Status of Species in Green Spaces in the City of Bujumbura (Burundi). Geo. Eco. Trop. 2022, 46, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal, J. , Useni, S. Y., Bogaert, J., Munyemba, K. F., & Mahy, G. La Perception Par Des Experts Locaux Des Espaces Verts et de Leurs Services Écosystémiques Dans Une Ville Tropicale En Expansion : Le Cas de Lubumbashi. In Anthropisation des paysages Katangais; Bogaert, J., Colinet, G., Mahy, G., Ed.; Liège-Belgique, 2018; pp. 59–69.

- Sikuzani, Y.U.; Mpibwe Kalenga, A.; Yona Mleci, J.; N’Tambwe Nghonda, D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Assessment of Street Tree Diversity, Structure and Protection in Planned and Unplanned Neighborhoods of Lubumbashi City (DR Congo). Sustain. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikuzani, Y.U.; Boisson, S.; Kaleba, S.C.; Khonde, C.N.; Malaisse, F.; Halleux, J.-M.; Bogaert, J.; Kankumbi, F.M. Dynamique de l’occupation Du Sol Autour Des Sites Miniers Le Long Du Gradient Urbain-Rural de La Ville de Lubumbashi, RD Congo. Base 2019, 24, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambieni, K.R. Dynamique Du Paysage de La Ville Province de Kinshasa Sous La Pression de La Périurbanisation: L’infrastructure Verte Comme Moteur d’aménagement. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole régionale post-universitaire d'Aménagement et de gestion intégrée des forêts et territoires tropicaux, Kinshasa, Republique Démocratique du Congo et Université de Liège,Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Salmon, M.; Ozer, A.; Pissart, A. Les Images Satellitaires Prises En Période de Sécheresse, Outil Utile Pour La Cartographie Géologique de La Belgique. Bull. la Soc. Géo. Liège 2007, 49, 67–74.

- Nicolas Soucy-Gonthier, Danielle Marceau, M.D.; Alain Cogliastro, G.D. et A.B. Détection de l’évolution Des Superficies Forestières En Montérégie Entre Juin 1999 et Août 2002 à Partir d’images Satellitaires LandSat-TM; Montréal, Canada, 2003.

- Zurqani, H. A. , Post, C. J., Mikhailova, E. A., Schlautman, M. A., & Sharp, J.L. Geospatial Analysis of Land Use Change in the Savannah River Basin Using Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 69, 175–185.

- Zhu, Z.; Woodcock, C.E. Object-Based Cloud and Cloud Shadow Detection in Landsat Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barima, Y.S.S.; Barbier, N.; Bamba, I.; Traoré, D.; Lejoly, J.; Bogaert, J. Dynamique Paysagère En Milieu de Transition Forêt-Savane Ivoirienne. Bois Forets Des Trop. 2009, 299, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floreano, I. X. , & de Moraes, L.A.F. Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Analysis (2009–2019) with Google Earth Engine and 2030 Prediction Using Markov-CA in the Rondônia State, Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 239.

- Girard, M. C., & Girard, C.M. Traitement Des Données de Télédétection; Environnem.; Paris, 2010.

- Bogaert, J.; Vranken, I.; Andre, M. Anthropogenic Effects in Landscapes: Historical Context and Spatial Pattern. Bio. Landsc. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C. Issues in Measuring Landscape Fragmentation. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1998, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, J.; Myneni, R.B.; Knyazikhin, Y. The Shape Index. Landsc. Ecol. 2002, 85443, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbarth, M.H.K.; Scianini, M; With, K.A.; Wiegand, K.; Nowosad, J. Landscaperemetrics: An Open-Source R Tool to Calculae Landscape Matrics. Ecogr. 2019, 1648–1657. [CrossRef]

- Diallo, H. , Bamba I., Barima Y.S.S., Visser M., B.; A., Mama A., Vranken I., M.M.&; J., B. Effets Combinés Du Climat et Des Pressions Anthropiques Sur La Dynamique Évolutive de La Dégradation d’une Aire Protégée Du Mali (La Réserve de Fina, Boucle Du Baoulé). Scie. et chang. plan./Séch. 2011, 22, 97-107.

- Bogaert, J.; Barima, Y.S.S.; Mongo, L.I.W.; Bamba, I.; Mama, A.; Toyi, M.; Lafortezza, R. Forest Fragmentation: Causes, Ecological Impacts and Implications for Landscape Management. Landsc. Ecol. For. Manag. Conserv. 2011, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van Eysenrode, D. Decision Tree Algorithm for Detection of Spatial Processes in Landscape Transformation. Environ. Manage. 2004, 33, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haulleville, T.; Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Rakoto Ratsimba, H.; Bastin, J.F.; Brostaux, Y.; Verheggen, F.J.; Rajoelison, G.L.; Malaisse, F.; Poncelet, M.; Haubruge, É.; beeckman, H. ; Bogaert,J. Fourteen Years of Anthropization Dynamics in the Uapaca Bojeri Baill. Forest of Madagascar. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 14, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tente, O.; Oloukoi, J.; Toko, I.; Tente, O.; Oloukoi, J.; Toko, I. Dynamique Spatiale et Structure Du Paysage Dans La Commune de Zè, Bénin. In OSFACO Conference: Satellite images for sustainable land management in Africa, 2019.

- Vani, V.; Mandla, V.R. Comparative Study of NDVI and SAVI Vegetation Indices in Anantapur District Semi-Arid Areas. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Razagui, A. , & Bachari, N.E.I. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of NDVI Vegetation Index Calculated from NOAA and MSG Satellite Images. J. Renew. Energies, 2014, 17, 497–506.

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Leeuwen, W. Van; Miura, T.; Glenn, E. Land Remote Sensing and Global Environmental Change: NASA’s Earth Observing System and the Science of ASTER and MODIS. 2011, 894. [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Tovar, C.L. L’indice Différentiel Normalisé de Végétation Comme Indicateur de La Dégradation. Unasylva 2011, 62, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data Data for Categorical of Observer Agreement The Measurement. 2012, 33, 159–174.

- G. M. Foody Assessing the Accuracy of Land Cover Change with Imperfect Ground Rerefence Data. Remote Sens. Envirnement 2010, 144, 2271–2285.

- Hesselbarth, M.H.K.; Nowosad, J.; Signer, J.; Graham, L.J. Open-Source Tools in R for Landscape Ecology. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Reports 2021, 6, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayiranga, A.; Kurban, A.; Ndayisaba, F.; Nahayo, L.; Karamage, F.; Ablekim, A.; Li, H.; Ilniyaz, O. Monitoring Forest Cover Change and Fragmentation Using Remote Sensing and Landscape Metrics in Nyungwe-Kibira Park. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2016, 04, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simwanda, M.; Ranagalage, M.; Estoque, R.C.; Murayama, Y. Spatial Analysis of Surface Urban Heat Islands in Four Rapidly Growing African Cities. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman,R. T.T. Some General Principles of Landscape and Regional Ecology. Landsc. Ecol. 1995, 10, 133–142.

- Burel, F.; Baudry, J. Ecologie Du Paysage. Concepts, Méthodes et Applications; Tec & Doc.; Paris, France. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, J.; Bamba, I.; Koffi, K.J.; Sibomana, S.; Djibu, J.K.; Champluvier, D.; Robbrecht, E.; Visser, M.N. Fragmentation of Forest Landscapes in Central Africa : Causes , Consequences and Management. In Patterns and processes in forest landscapes: Multiple use and sustainable management; Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2008; pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, J.; Mahamane, A. Ecologie du Paysage : Cibler la Configur ation et l ’ Echelle Spatiale. Ann. des Sci. Agron. du Bénin 2005, 7, 1–18.

- Haila, Y. A Conceptual Genealogy of Fragmentation Research: From Island Biogeography to Landscape Ecology. Ecol. Appl. 2002, 12, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhamadou, I.T.; Imorou, I.T.; Sinsin, B. Perceptions locales des déterminants de la fragmentation des îlots de forêts denses dans la région des Monts Kouffé au Bénin. J. of Appl. Bio. 2022, 66, 5049–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabulu, D.J.; Bamba, I.; Munyemba, K.F.; Defourny, P.; Vancutsem, C.; Nyembwe, N.S.; Ngongo, L.M.; Bogaert, J. Analyse de La Structure Spatiale Des Forêts Au Katanga. Ann. la Fac. des Sci. Agron. Univ. Lubumbashi 2015, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ducrot, D. Méthodes d’analyses et d’interprétation d’images de Télédétection Multisource. Extraction de Caractéristiques Du Paysage, Toulouse, France, 2005.

- Mouhamadou, I.T.; Touré, F.; Imorou, I.T.; Sinsin, B. Indices de Structures Spatiales Des Îlots de Forêts Denses Dans La Région Des Monts Kouffé. VertigO 2012, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcros, P. Ecologie Du Paysage et Dynamique Végétale Post-Culturale; 1994; Vol. 13; ISBN 2853623823.

- Bogaert, J.; Rousseau, R.; Van Hecke, P.; Impens, I. Alternative Area-Perimeter Ratios for Measurement of 2D Shape Compactness of Habitats. Appl. Math. Comput. 2000, 111, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuanga, J.M.; Adipalina Guguya, B.; Ngenda Okito, E.; Maestripieri, N.; Saqalli, M.; Rossi, V.; Iyongo Waya Mongo, L. Suivi de l’anthropisation Du Paysage Dans La Région Forestière de Babagulu, République Démocratique Du Congo. VertigO 2020, 20, 0–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diello, P.; Mahe, G.; Paturel, J.-E.; Dezetter, A.; Delclaux, F.; Servat, E.; Ouattara, F. Relations Indices de Végétation–Pluie Au Burkina Faso: Cas Du Bassin Versant Du Nakambé/Relationship between Rainfall and Vegetation Indexes in Burkina Faso: A Case Study of the Nakambé Basin. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2005, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, W.; Skidmore, A.K.; Toxopeus, A.G. Vegetation NDVI Linked to Temperature and Precipitation in the Upper Catchments of Yellow River. Environ. Model. Assess. 2012, 17, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangirinama, F.; Nzitwanayo, B.; Hakizimana, P. Utilisation Du Charbon de Bois Comme Principale Source d’énergie de La Population Urbaine : Un Sérieux Problème Pour La Conservation Du Couvert Forestier Au Burundi. Bois Forets des Trop. 2016, 8, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavunda, C.A.; Kanda, M.; Folega, F.; Egbelou, V.; Bosela, B.; Drazo, N.A.; Yoka, J.; Dourma, M. Dynamique Spatio-Temporelle Des Changements d ’ Occupation Du Sol Sous Incidence Anthropique Dans La Ville de Kinshasa ( RDC ) de 2001 à 2021. Geo-Eco-Trop 2022, 137–148.

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Ecol. ec. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoumani, A.; Victor, R.; Randriamampandry, C. La Croissance de La Ville d ’ Antananarivo et Ses Conséquences. Madamines 2019, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, F.; Nakagoshi, N. Spatial-Temporal Gradient Analysis of Urban Green Spaces in Jinan, China. Land. and urb. Plan. 2006, 78, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, R.I.; Forman, R.T.T.; Kareiva, P. Open Space Loss and Land Inequality in United States ’ Cities, 1990 – 2000. PLoS One 2010, 5(3), e9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyi, O. Politiques Publiques Urbaines De L ’ Habitat Dans La Ville De Bujumbura De 1962 a 2009. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour, Pau, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kabanyegeye, H.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Sambieni, K.R.; Mbarushimana, D.; Masharabu, T.; Bogaert, J. Analysis of Anthropogenic Disturbances of Green Spaces along an Urban–Rural Gradient of the City of Bujumbura (Burundi). Land 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kaleba, S.C.; Halleux, J.M.; Bogaert, J.; Kankumbi, F.M. Caractérisation de La Croissance Spatiale Urbaine de La Ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, R.D. Congo) Entre 1989 et 2014. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 99–108.

- Sikuzani, Y.U.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Kalumba Mwanke, A.; Yamba, A.M.; Nkuku Khonde, C.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Tree Diversity and Structure on Green Space of Urban and Peri-Urban Zones: The Case of Lubumbashi City in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujoh, F.; Dlama, K.I.; Oluseyi, I.O. Urban Expansion and Vegetal Cover Loss in and around Nigeria ’ s Federal Capital City. J. Ecol. Nat. Environ. 2011, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Koumoi, Z.; Alassane, A.; Djangbedja, M.; Boukpessi, T.; Kouya, A.-E. Dynamique Spatio-Temporelle de l’occupation Du Sol Dans Le Centre-Togo. Rev. Géographie du LARDYMES, Univ. Lomé 2013, 7, 163–172.

- Tungi, J.; Luzolo, T.; Ngembo, E.N.; Masivi, C.L.; Landu, E.L.; Kibwila, M.N. Pression Exercée Par Les Entreprises Pâtissières Artisanales et Nganda Ntaba Sur La Végétation Arborée Urbaine et Périurbaine à Kinshasa En République Démocratique Du Congo. Int. J. of Inn. and Sci. Res. 2022, 62, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.D.N.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Kaleba, S.C.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bastin, J.F.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bujumbura | Kinshasa | Lubumbashi | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of creation | 1897 | 1881 | 1910 |

| Location | Between 3°30' and 3°51' S and 29°31' and 29°42' E | Between 4°-5° S and 15°-16° E | Between 11°27' and 11°47' S and 27°19' and -27°40' E |

| Area | 10462 hectares | 9965 km2 | 747 km2 |

| Number of communes | 3 | 24 | 7 |

| Year | Bujumbura | Kinshasa | Lubumbashi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall accuracy | Kappa | Overall accuracy | Kappa | Overall accuracy | Kappa | |

| 2000 | 0,89 | 0,69 | 0,95 | 0,86 | 0,95 | 0,92 |

| 2013 | 0,93 | 0,79 | 0,97 | 0,88 | 0,96 | 0,94 |

| 2022 | 0,97 | 0,91 | 0,99 | 0,94 | 0,98 | 0,97 |

| Bujumbura | Year 2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | Buildings and bare ground | Other | Total | ||

| Year 2000 | Vegetation | 9,78 | 47,51 | 0,36 | 57,65 |

| Buildings and bare ground | 30,42 | 5,01 | 0,05 | 35,48 | |

| Other | 4,38 | 1,90 | 0,59 | 6,87 | |

| Total | 44,58 | 54,42 | 1,00 | 100 | |

| Year 2022 | |||||

| Vegetation | 18,17 | 26,36 | 0,06 | 44,58 | |

| Year 2013 | Buildings and bare ground | 1,69 | 52,17 | 0,56 | 54,42 |

| Other | 0,04 | 0,37 | 0,58 | 1,00 | |

| Total | 19,90 | 78,90 | 1,20 | 100 | |

| Kinshasa | Year 2013 | ||||

| Year 2000 | Vegetation | 58,31 | 6,70 | 0,46 | 65,47 |

| Buildings and bare ground | 11,17 | 21,94 | 0,03 | 33,14 | |

| Other | 1,12 | 0,06 | 0,21 | 0,39 | |

| Total | 70,60 | 28,70 | 0,70 | 100 | |

| Year 2022 | |||||

| Year 2013 | Vegetation | 60,78 | 8,28 | 1,54 | 70,60 |

| Buildings and bare ground | 3,86 | 24,80 | 0,04 | 28,70 | |

| Other | 0,28 | 0,02 | 0,40 | 0,71 | |

| Total | 64,92 | 33,10 | 1,99 | 100 | |

| Lubumbashi | Year 2013 | ||||

| Year 2000 | Vegetation | 30,85 | 17,75 | 21,65 | 70,25 |

| Buildings and bare ground | 1,13 | 12,75 | 2,75 | 16,63 | |

| Other | 3,46 | 4,67 | 4,99 | 13,12 | |

| Total | 35,44 | 35,17 | 29,39 | 100 | |

| Year 2022 | |||||

| Year 2013 | Vegetation | 18,91 | 7,55 | 8,98 | 35,44 |

| Buildings and bare ground | 1,89 | 30,92 | 2,36 | 35,17 | |

| Other | 5,46 | 15,50 | 8,43 | 29,39 | |

| Total | 26,26 | 53,97 | 19,77 | 100 | |

| Bujumbura | Kinshasa | Lubumbashi | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-2013 | Vegetation | 0,12 | 3,00 | 0,70 |

| Buildings and bare ground | 0,06 | 1,22 | 0,41 | |

| Other | 0,09 | 0,13 | 0,13 | |

| 2013-2022 | Vegetation | 0,65 | 4,35 | 0,79 |

| Buildings and bare ground | 1,80 | 2,03 | 1,13 | |

| Other | 0,56 | 0,21 | 0,26 |

| City | Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bujumbura | 2000 | 1246 | 6032,39 | 1,55 | 1,45 | 92,47 | 1,04 |

| 2013 | 1349 | 4665,01 | 5,15 | 1,79 | 91,99 | 1,04 | |

| 2022 | 1007 | 2081,94 | 3,36 | 1,62 | 86,03 | 1,04 | |

| Kinshasa | 2000 | 7704 | 652209,25 | 57,47 | 15,36 | 92,80 | 1,04 |

| 2013 | 4623 | 703429,35 | 63,49 | 27,61 | 95,50 | 1,04 | |

| 2022 | 6685 | 646828,15 | 56,57 | 17,56 | 94,40 | 1,04 | |

| Lubumbashi | 2000 | 6925 | 55453,28 | 47,12 | 8,00 | 85,46 | 1,04 |

| 2013 | 5386 | 28034,65 | 10,77 | 5,20 | 83,30 | 1,04 | |

| 2022 | 11173 | 20904,10 | 15,96 | 1,87 | 92,10 | 1,04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).