Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

23 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methods

3. Detailed Examination of Research Ethics Laws

3.1. The Main Difference between French Law and the Laws of Anglo-Saxon Countries

3.2. Document Number 09-022 Is an Advisory Opinion of the Local Ethics Committee and not a Compulsory CPP/IRB Authorization

3.3. Similarities between French Law and US Law

3.4. Confirmation by the French Authorities

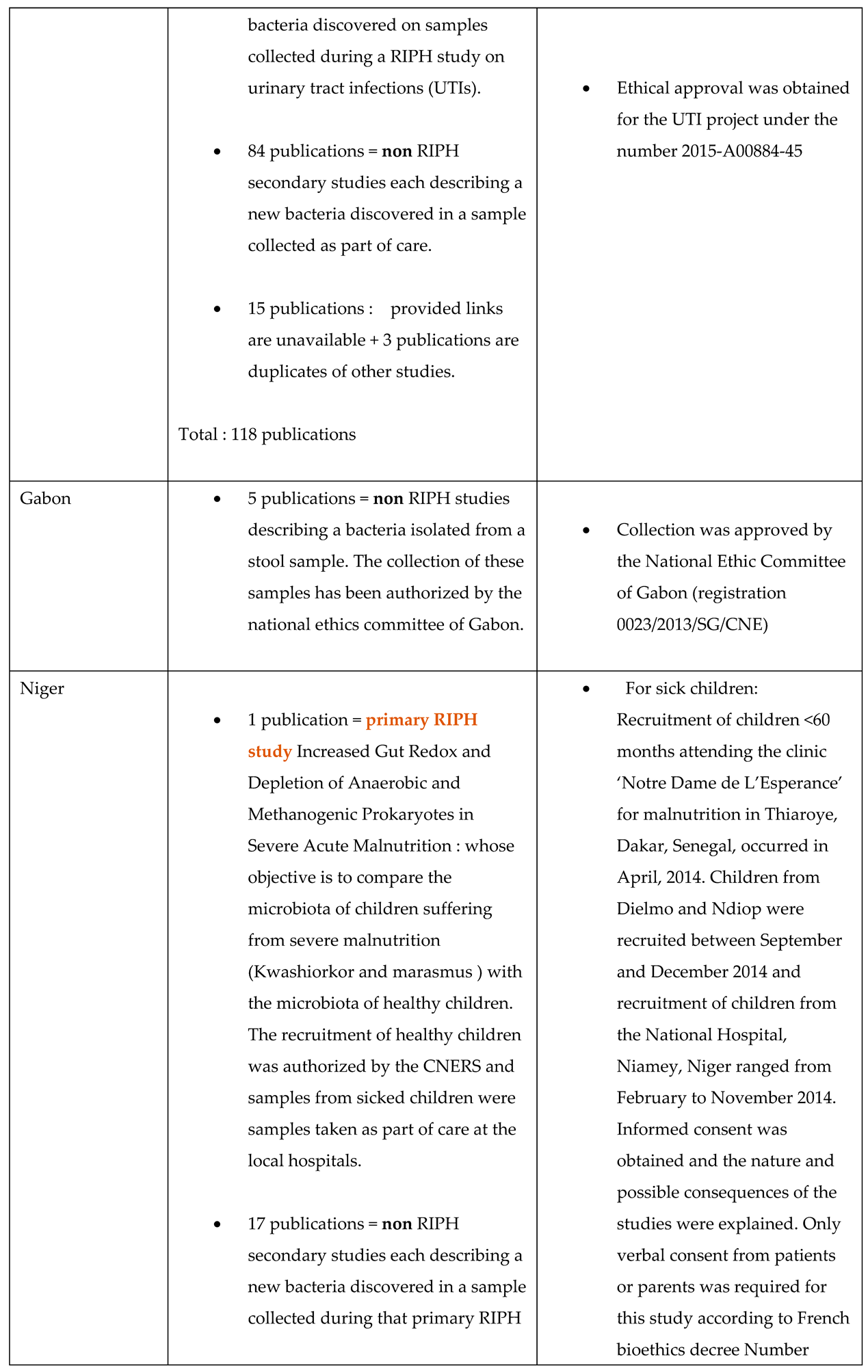

3.5. Lack of Ethics Committees and Specific Legislation in Some Countries

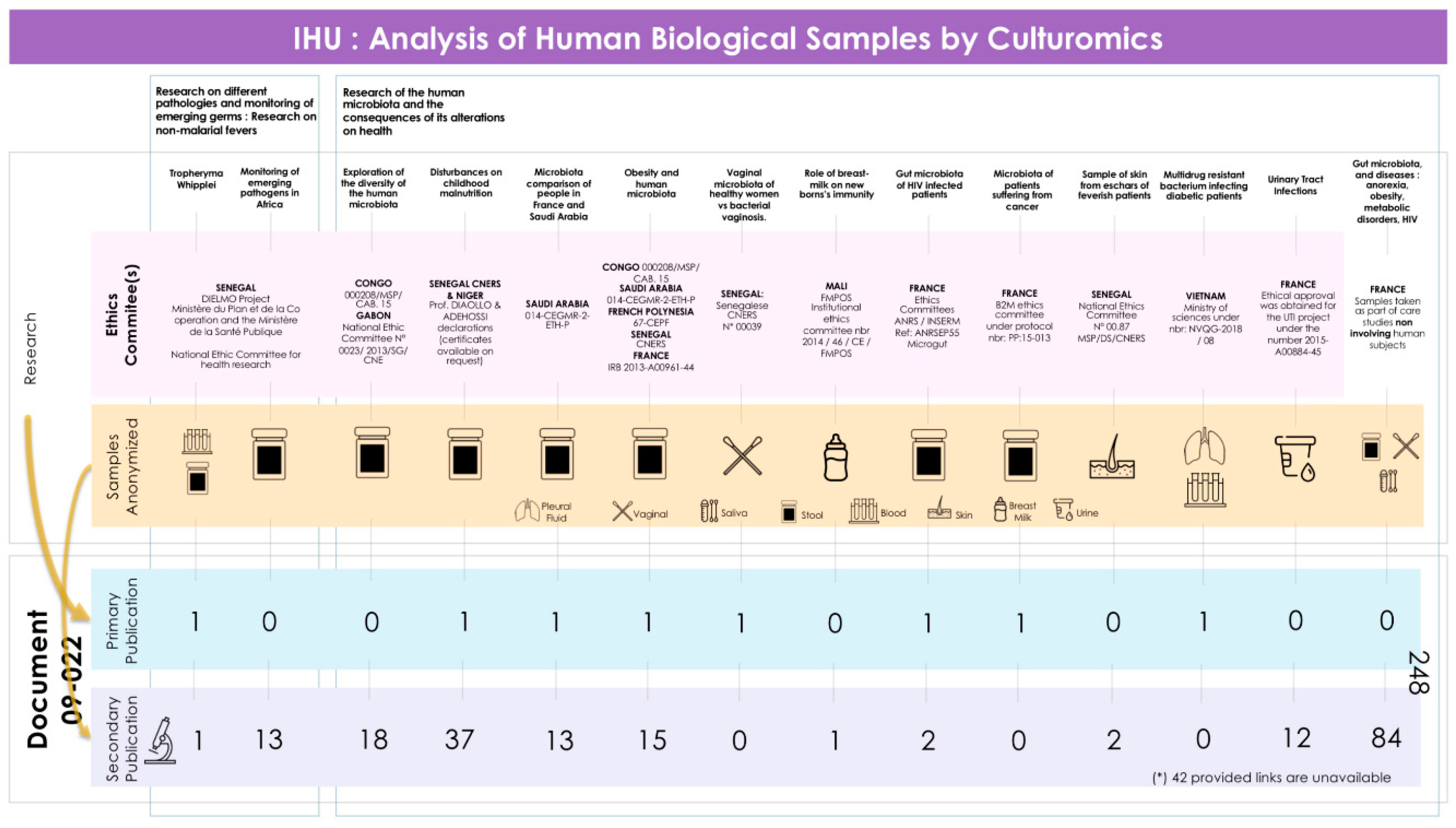

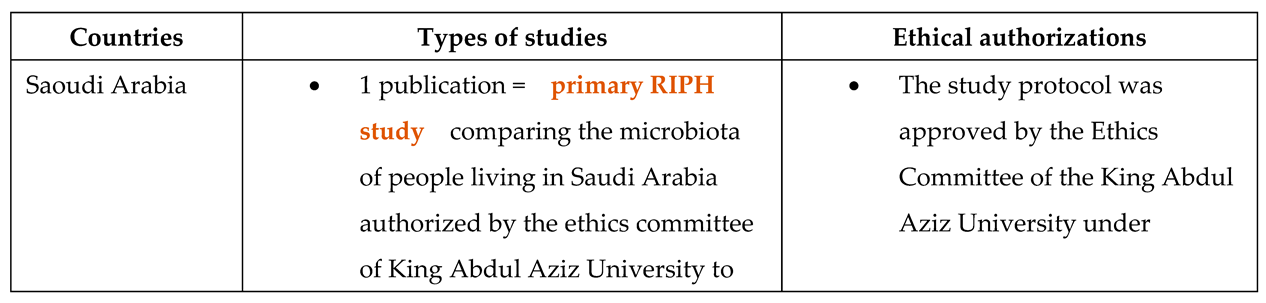

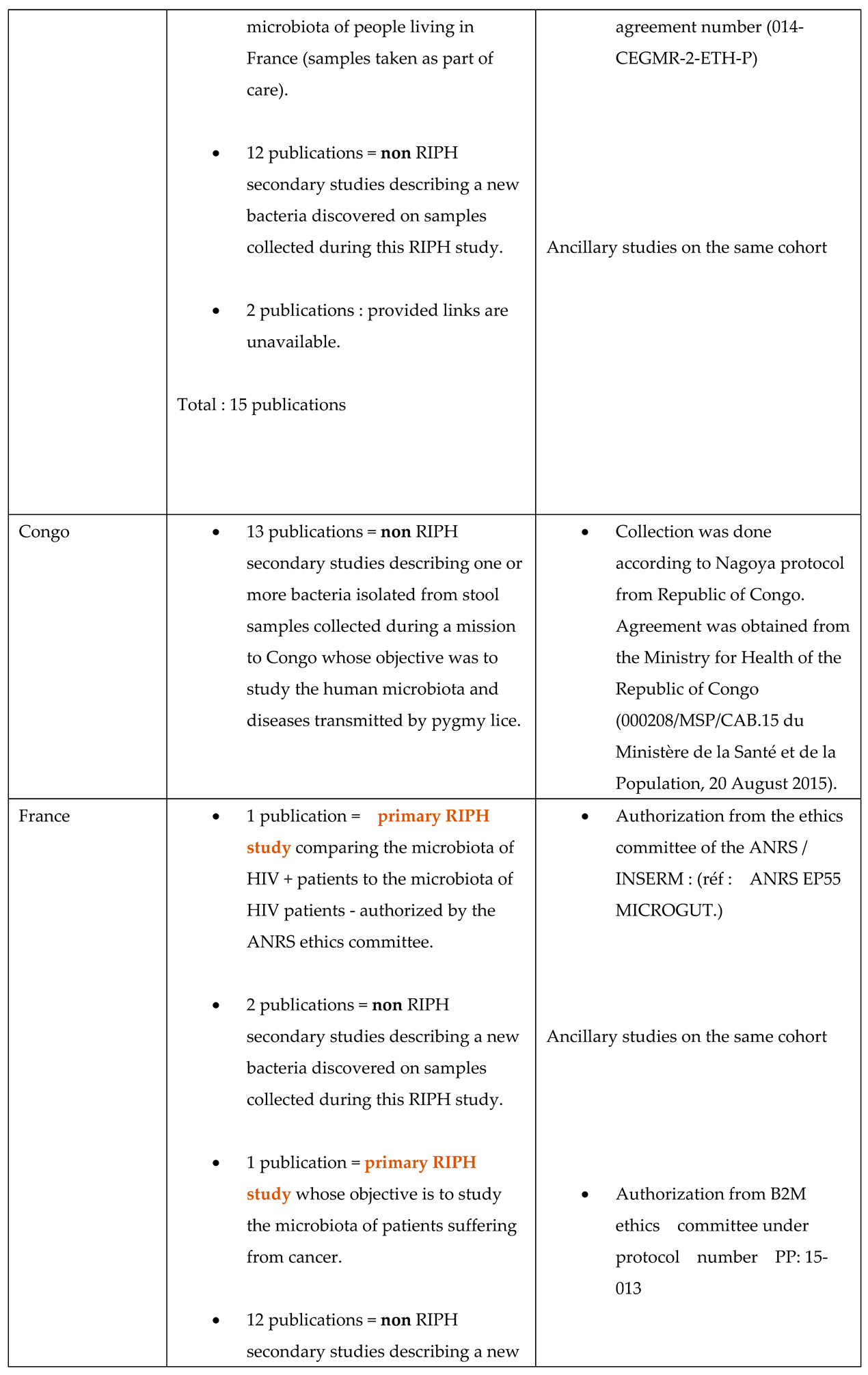

4. Results

4.1. The Absence of Article Titles Makes It Difficult to Identify the Type of Studies

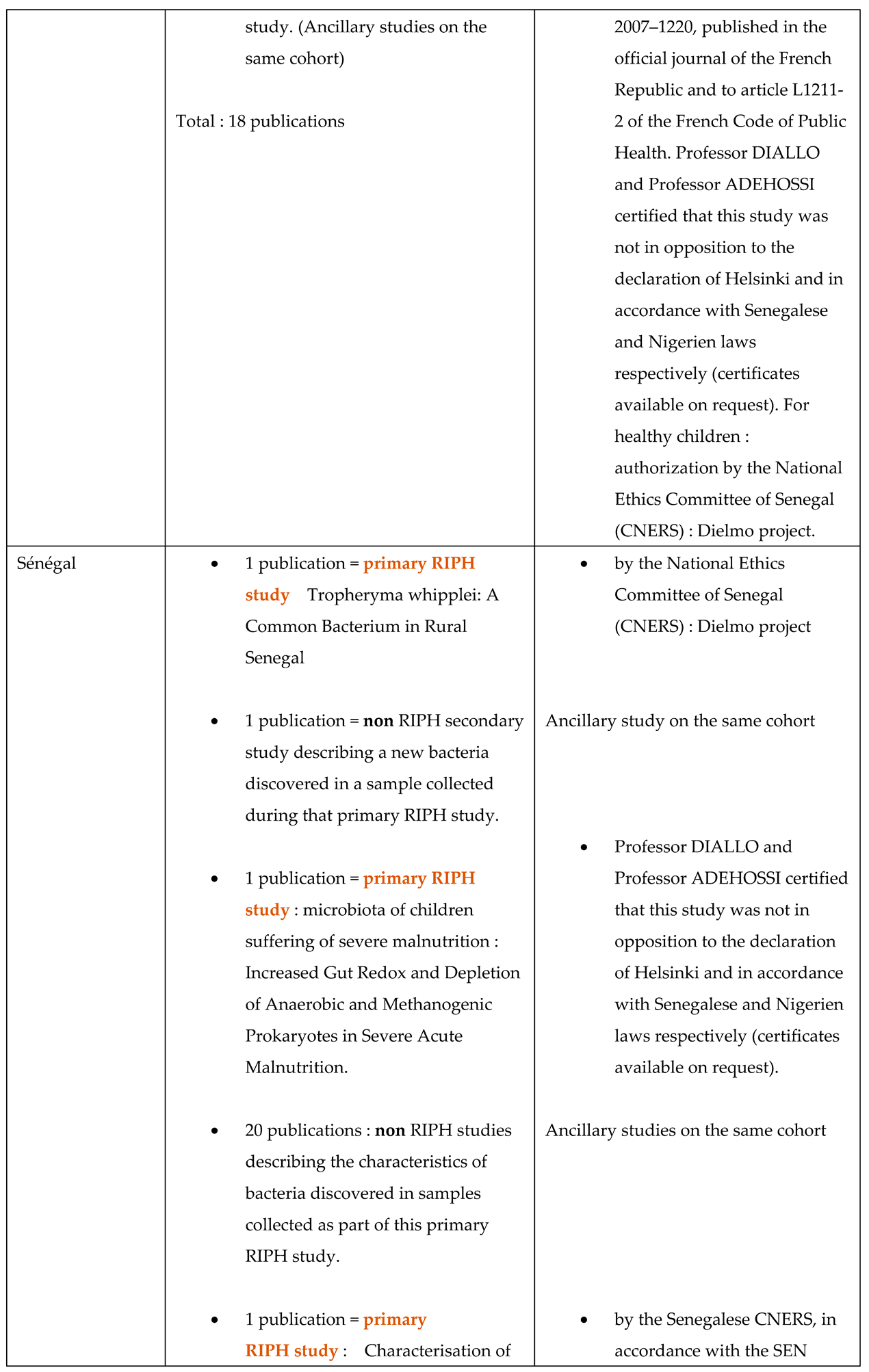

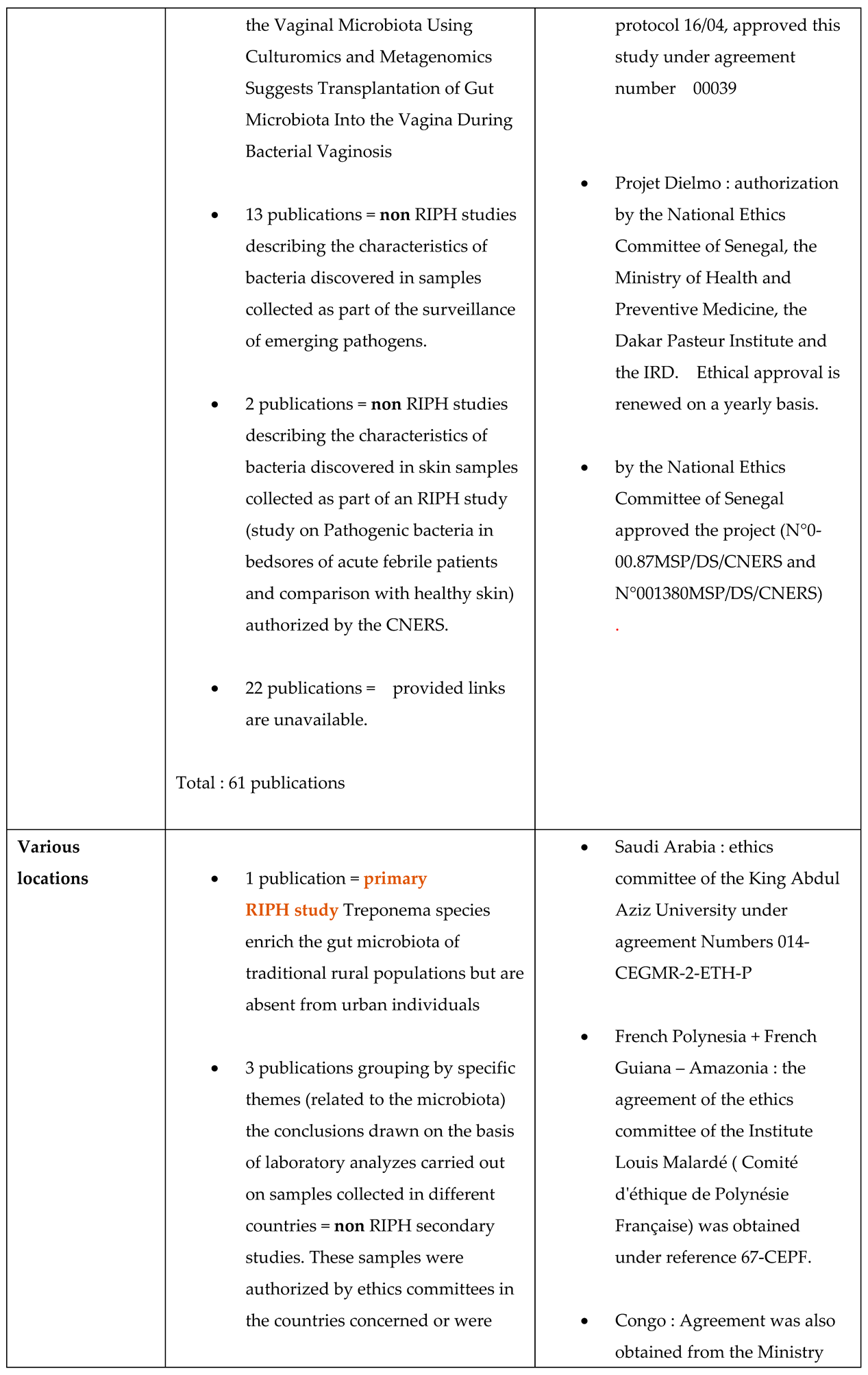

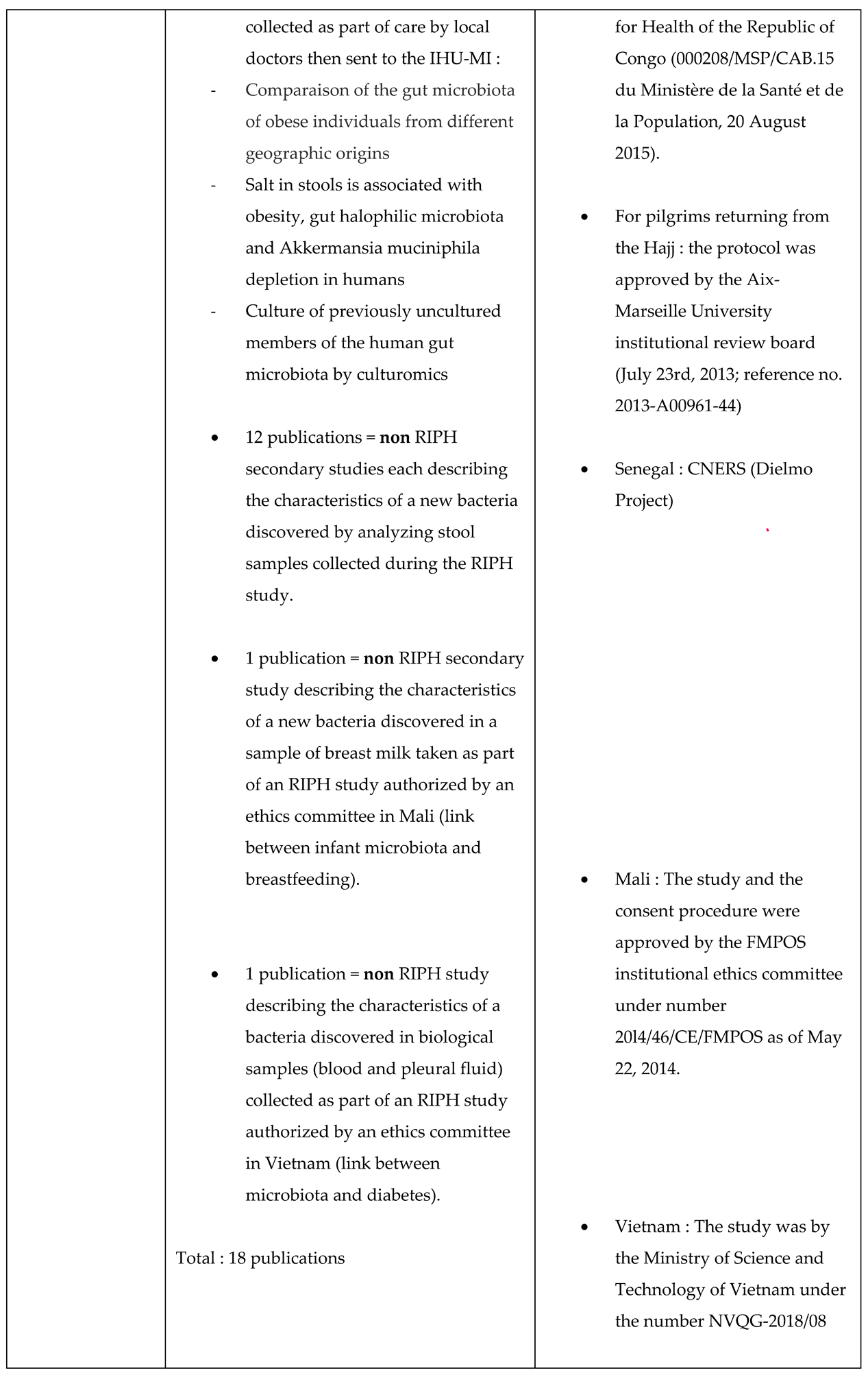

4.2. A superficial Analysis of the Contents Overlooks the Authorizations Given to the Primary Studies from Which the Analyzed Samples Originate

4.3. The Introduction to Publications Mentions the Overall Project

- -

- All these publications are part of a long-term global research project.

- -

- This document is not a legally binding authorization for RIPH research from an IRB, but an optional document of the IHU-MI’s local ethics committee confirming that the legislation authorizes laboratory analyses (non-RIPH research) on biological samples, whether these samples have been obtained as part of a RIPH study authorized by an independent ethics committee or as part of patient care.

- -

- The primary RIPH studies from which the biological samples analyzed were taken have all been approved by CPP/IRB, whose references are given in the publications relating to these primary studies.

- -

- This same document can be used for all publications resulting from this global research project, regardless of their number.

4.4. About the Low Response Rate From Publishers

5. Discussion

- -

- Should have checked whether the IHU-MI’s ethics committee is a CPP/IRB, whose authorizations are mandatory, or a local consultative ethics committee (using a same document for numerous publications is not fraudulent if this document is only legally optional).

- -

- Among the documents available on the ANSM website, they should have used and provided the one that would have made it possible to understand that the same number can be used for all research publications not involving the human person that are part of the same global project. Because it is this global project to study the human microbiota that is approved by the IHU-MI’s local ethics committee. Furthermore, they should have taken account of the fact that the publications state that they are part of this overall project.

- -

- Should have rigorously examined each of the publications concerned rather than focusing on the repetition of the same issue. Their analysis, which they themselves describe as rapid, neglected to search for the CPP/IRB ethics committee authorizations received for the primary RIPH studies.

- -

- Should have seen that more than a third of publications concern samples taken in the context of healthcare, which do not require a CPP/IRB approval.

- -

- Should also have seen that the vast majority of publications are « genome announcements » which do not require CPP/IRB approval either.

- -

- Should have investigated the specific ethical legislation of the developing countries from which certain samples originated. This would have revealed the absence of ethical legislation and functioning ethics committees in some of these countries at the time the samples were collected.

- -

- Should have investigated the IHU-MI’s international health monitoring missions, which would have enabled them to envisage that specific biological samples had been taken by local doctors and sent to the IHU-MI laboratory for the purpose of diagnosing tropical diseases. These diagnostic samples do not require CPP/IRB authorization.

- -

- Should have known (and mentioned in their article) that research not involving human beings is not subject to the same legal requirements as research involving human beings. However, several co-authors have already published non-HIPR studies and are therefore familiar with the differences between these two types of research.

- -

- Should have compared with research not involving human subjects published by other French teams. They would have noticed that these publications do not require CPP/IRB authorizations.

- -

- Should have taken into account the replies they received from publishers reassuring them that the ethical rules were being respected and explaining why their concerns were unfounded. These explanations provided about some of the publications could have enabled them to re-examine other publications of the same type and to understand that they were wrong in their interpretation of French law.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAR | Autorisation Administrative de Recherche. |

| ANSM | Agence Nationale de la Santé et du Médicament. |

| CCNE | Comité Consultatif National d’Ethique. |

| CEL | Comité Local d’Ethique. |

| CNERS | Comité National d’Ethique de la Recherche en Santé |

| CNR | Centre National de Référence des Rickettsies, Coxiella et Barnotella. |

| COPE | Committee on Publication Ethics. |

| CPP | Commission de Protection des Personnes i.e IRB. |

| IFR | Institut Fédératif de Recherche. |

| IGAS | Inspection Générale des Affaires Sociales. |

| IHU | Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire. |

| IHU-MI | IHU Méditerannée Infection. |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board. |

| INSERM | Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale. |

| HHS | Department of Health and Human Services. |

| MESR | Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. |

| MST | Maladies Sexuellement Transmissibles. |

| RECs | Research Ethics Committees. |

| RHB | Research on Human Beings |

| RIPH | Recherche impliquant la personne humaine i.e. research involving human subjects. |

| Non-RIPH | Recherches n’impliquant pas la personne humaine i.e research non involving human subjects. |

References

- COPE Council – COPE Discussion Document: Dealing with concerns about the integrity of published research – English. [CrossRef]

- COPE Council – Resources – Addressing ethics complaints from complainants who submit multiple issues. [CrossRef]

- Frank, F., Florens, N., Meyerowitz-katz, G. et al. Raising concerns on questionable ethics approvals – a case study of 456 trials from the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire Méditerranée Infection. Res Integr Peer Rev 8, 9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- ARS île de France – Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé – Comités de Protection des Personnes : https://www.iledefrance.ars.sante.fr/media/86137/download?inline. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Infectiologie.com – Le site de l’infectiologie Française – La recherche clinique et la loi Jardé : https://www.infectiologie.com/UserFiles/File/formation/desc/2019/seminaire-avril-2019/jeudi-04-04-2019/recherche-6-jeudi-04-marion-noret.pdf . Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Legifrance – Le service public de la diffusion du droit – République Française – Code de Santé Publique – Article L1211-2. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/article_lc/LEGIARTI000043895792. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Inserm – La science pour la santé – République Française. https://www.inserm.fr/nos-recherches/recherche-clinique/la-recherche-clinique/. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Unité de Recherche Clinique de l’Est Parisien – La carte des CPP en France et dans les DOM TOM. http://urcest.com/la-carte-des-cpp-en-france-et-dans-les-dom-tom#languedoc-roussillon-provence-alpes-c%C3%B4te-d-39-azur-et-la-corse. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- ANSM – Agence Nationale des Produits de santé et du Médicament – Document numéro 2020-001. https://ansm.sante.fr/uploads/2022/11/28/20221004-cada22v207-ethiq-2020-001.pdf. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- ANSM – Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé – Documents transmis le 28/11/2022 - Comité d’éthique de l’IHU Méditerranée-infection. https://ansm.sante.fr/page/documents-transmis-le-28-11-2022-comite-dethique-de-lihu-mediterranee-infection. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- ANSM – Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé – Document numéro 2016-011. https://ansm.sante.fr/uploads/2022/11/28/20221004-cada22v207-ethiq-2016-011.pdf. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – 45 CFR 46 FAQs. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/45-cfr-46/index.html. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – 45 CFR 46 Exemptions. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/common-rule-subpart-a-46104/index.html. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – Exempt Research Determination – 45 CFR 46.101 (b). https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/exempt-research-determination/index.html. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services - Human Subject Regulations Decision Charts: 2018 Requirements – Chart 01: Is an Activity Human Subjects Research Covered by 45 CFR Part 46? – And Chart 09: Does Exemption 45 CFR 46.104(d)(7), Storage for Secondary Research for Which Broad Consent Is Required, Apply? https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/decision-charts-2018/index.html. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- HHS.gov – Department of Health and Human Services – OHRP E-Learning Program – What is human subjects research ? : https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/OHRP-HHS-Learning-Module-Lesson2.pdf. Accessed Oct 31 2023.

- UCSF – University of California San Francisco – Not Human Subjects Research : https://irb.ucsf.edu/not-human-subjects-research. Accessed Oct 31 2023.

- University of Virginia – Research Involving Data and/or Biological Specimens : https://research.virginia.edu/sites/vpr/files/2019-08/25-03-Research-Involving-Data-and-or-Biological-Specimens.pdf. Accessed Oct 31 2023.

- Infectiologie.com – Le site de l’infectiologie Française – Outils de formation – Recherches « Hors Loi Jardé » M. NORET – Chef de projet Clinique des pathologies infectieuses – 6 Octobre 2021. https://www.infectiologie.com/UserFiles/File/formation/desc/2021/seminaire-octobre-2021/merc-610-t.27/conf-4-hors-loi-jarde-mnoret.pdf Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Infectiologie.com – Le site de l’infectiologie Française – Outils de formation – Autorisations règlementaires : CPP, comité d’éthique, ANSM, CNIL. – Docteur Sébastien Gallien – Service d’immunologie et maladies infectieuses Université Paris Est Créteil. Equipe 16 INSERM U955 IMRB & VRI – 4 avril 2019. https://www.infectiologie.com/UserFiles/File/formation/desc/2019/seminaire-avril-2019/jeudi-04-04-2019/recherche-9-jeudi-04-dr-gallien.pdf. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Comité de Protection des Personnes (en recherche biomédicale) CPP Tours Ouest-1. – « Je veux démarrer une recherche sur des échantillons biologiques déjà prélevés à l’occasion du soin ou d’une recherche (changement de finalité) ». https://cppouest1.fr/mediawiki/index.php?title=CPP_Ouest-1:NOD0126. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Council of Europe – Guide for Research Ethics Committee Members – Steering Committee on Bioethics. https://www.coe.int/t/dg3/healthbioethic/activities/02_biomedical_research_en/Guide/Guide_EN.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct 2023.

- European Network of Research Ethics Committees – EUREC – Position of the European Network of Research Ethics Committees (EUREC) on Ethics Reviews of Research Projects involving Persons outside Biomedical Research. http://www.eurecnet.org/documents/EUREC_Positionpaper_March_2021.pdf. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- CER Sorbonne Université.fr – Collections biologiques Réglementation – Mise à jour 15/12/2020 : https://cer.sorbonne-universite.fr/sites/default/files/media/2021-06/CER-collections-biologiques.pdf . Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- R. Souche, S. Mas, O. Scatton, J.-M. Fabre, L. Gimeno, A. Herrero, S. Gaujoux, French legislation on retrospective clinical research: What to know and what to do, Journal of Visceral Surgery, Volume 159, Issue 3, 2022, Pages 222-228, ISSN 1878-7886. [CrossRef]

- Amiel P., Dosquet C., Comité d’évaluation éthique de l’inserm (CEEI), Guide de qualification des recherches en santé [A qualification guide for health research], Inserm, 2021. https://comite-ethique.cnrs.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Inserm_GuideQualifCEEI_2021mai.pdf.

- Husson, T., Lecoquierre, F., Nicolas, G. et al. Episignatures in practice: independent evaluation of published episignatures for the molecular diagnostics of ten neurodevelopmental disorders. Eur J Hum Genet 32, 190–199 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Inspection Générale des Affaires Sociales – igas.gouv.fr – Contrôle de l’IHU Méditerranée infection – Rapport définitif tome 1 – Août 2023. https://www.igas.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_ihu_definitif_tome_1_.pdf Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Sénat Français – Question écrite n°05533 – 16e législature – Qualification des déchets résultant de la recherche médicale – Août 2023 https://www.senat.fr/questions/base/2023/qSEQ230305533.html. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Convention on Biological Diversity – Access and Benefit-sharing Clearing-House (ABS Clearing-House, ABSCH) – Arrêté du 17 mai 2013 du Ministère des Enseignements Moyen et Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique de la République du Niger fixant les conditions d’obtention d’Autorisation Administrative de Recherche (AAR) au Niger. https://absch.cbd.int/api/v2013/documents/F41B0FAB-46D1-5BF6-254E-83C88E73BE10/attachments/203719/Arr%C3%AAt%C3%A9%20106%20MEMS%20RS.PDF Accessed Oct 31 2023.

- Health Research Web – Plan stratégique national de la recherche en santé 2013-2020 – Ministère de la Santé du Niger. https://healthresearchwebafrica.org.za/files/PLAN_STRATEGIQUE_RECERCHE_EN_SANTE_2013_2020adoptjuin..pdf Accessed Nov 03 2023.

- Chaudhry I, Thurtle V, Foday E, et al. Strengthening ethics committees for health-related research in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2022;12:e062847. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/12/11/e062847. [CrossRef]

- Centre National d’Ethique de la Recherche Scientifique du Sénégal – Ressources - Rapport consultant évaluation du système de revue éthique. https://cners.sn/public/docs/1587396889.pdf Accessed Nov 03 2023.

- Barchi, F., Little, M.T. National ethics guidance in Sub-Saharan Africa on the collection and use of human biological specimens: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 17, 64 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Health Research Web – Rapport du comité d’évaluation des sites de recherche de Dielmo et de Ndiop – Robin Bailey, Christophe Rogier, Samba Cor Sarr. – 1er Octobre 2009. https://healthresearchwebafrica.org.za/files/_RapportDielmoNdiop.pdf. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Abat Cédric, Colson P., Chaudet H., Rolain J. M., Bassene H., Diallo A., Mediannikov Oleg, Fenollar F., Raoult D., Sokhna Cheikh. (2016). Implementation of syndromic surveillance systems in two rural villages in Senegal. Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases, 10 (12), p. e0005212 [12 p.]. ISSN 1935-2735. [CrossRef]

- Institut Méditerranée Infection – Activité de surveillance épidémiologique. https://www.mediterranee-infection.com/veille-epidemiologique/lactivite-de-surveillance-epidemiologique-de-lihu/. Accessed Oct 27 2023.

- Méditerranée Infection – La veille sanitaire internationale de l’IHU. https://www.mediterranee-infection.com/veille-epidemiologique/lihu-et-la-surveillance-internationale-des-voyageurs/ Accessed Nov 08 2023.

- GéoSentinel – The Global Surveillance and Research Network – EuroTravNet. https://geosentinel.org/sites/eurotravnet Accessed Nov 08 2023.

- Méditerranée Infection – Présentation du CNR. https://www.mediterranee-infection.com/diagnostic/les-centres-nationaux-de-reference-cnr/cnr-rickettsioses/presentation-du-cnr/ Accessed Nov 08 2023.

- Dunning Hotopp JC, Baltrus DA, Bruno VM, Dennehy JJ, Gill SR, Maresca JA, Matthijnssens J, Newton ILG, Putonti C, Rasko DA, Rokas A, Roux S, Stajich JE, Stedman KM, Stewart FJ, Thrash JC. Best Practices for Successfully Writing and Publishing a Genome Announcement in Microbiology Resource Announcements. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2020 Sep 3;9(36):e00763-20. PMID: 32883786; PMCID: PMC7471381. [CrossRef]

- Antoine Altdorfer et al, Infective endocarditis caused by Neisseria mucosa on a prosthetic pulmonary valve with false positive serology for Coxiella burnetii – The first described case. Elsevier. 2021;24: e01146. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214250921001025. [CrossRef]

- WMA – Association Médicale Mondiale – Déclaration d’Helsinki - https://www.wma.net/fr/policies-post/declaration-dhelsinki-de-lamm-principes-ethiques-applicables-a-la-recherche-medicale-impliquant-des-etres-humains/ Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

- COPE – Guidelines – Cooperation between research institutions and journals on research integrity and publication misconduct cases. https://publicationethics.org/resources/guidelines/cooperation-between-research-institutions-and-journals-research-integrity Accessed Feb 20 2024.

- FRA – European Union Agency For Fundamental Rights – Charte des droits fondamentaux de l’Union Européenne - http://fra.europa.eu/fr/eu-charter/article/48-presomption-dinnocence-et-droits-de-la-defense Accessed Feb 20 2024.

- APMNews – Dépêche du 7 Août 2023 – Des manquements éthiques identifiés dans plus de 450 publications de l’IHU de Marseille. https://www.apmnews.com/freestory/10/399289/des-manquements-ethiques-identifies-dans-plus-de-450-publications-de-l-ihu-de-marseille Accessed Oct 29 2023.

- L’Express – Fraudes scientifiques et manquements éthiques : l’équipe derrière la chute de Didier Raoult – Article publié le 14 Août 2023. https://www.lexpress.fr/sciences-sante/sciences/fraudes-scientifiques-et-manquements-ethiques-lequipe-derriere-la-chute-de-didier-raoult-BBWUTRR7NRDRJPQILKVBUV7NHQ/ Accessed Oct 29 2023.

- The Guardian – French research center behind controversial Covid paper found to have used questionable ethics processes – Article publié le 8 Août 2023: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/09/french-research-centre-behind-controversial-covid-paper-found-to-have-used-questionable-ethics-processes Accessed Oct 29 2023.

- Libération – Un village éprouvette au Sénégal – Publié le 26 août 2002 : https://www.liberation.fr/cahier-special/2002/08/26/un-village-eprouvette-au-senegal_413542/ Accessed Oct 29 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).