Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

23 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

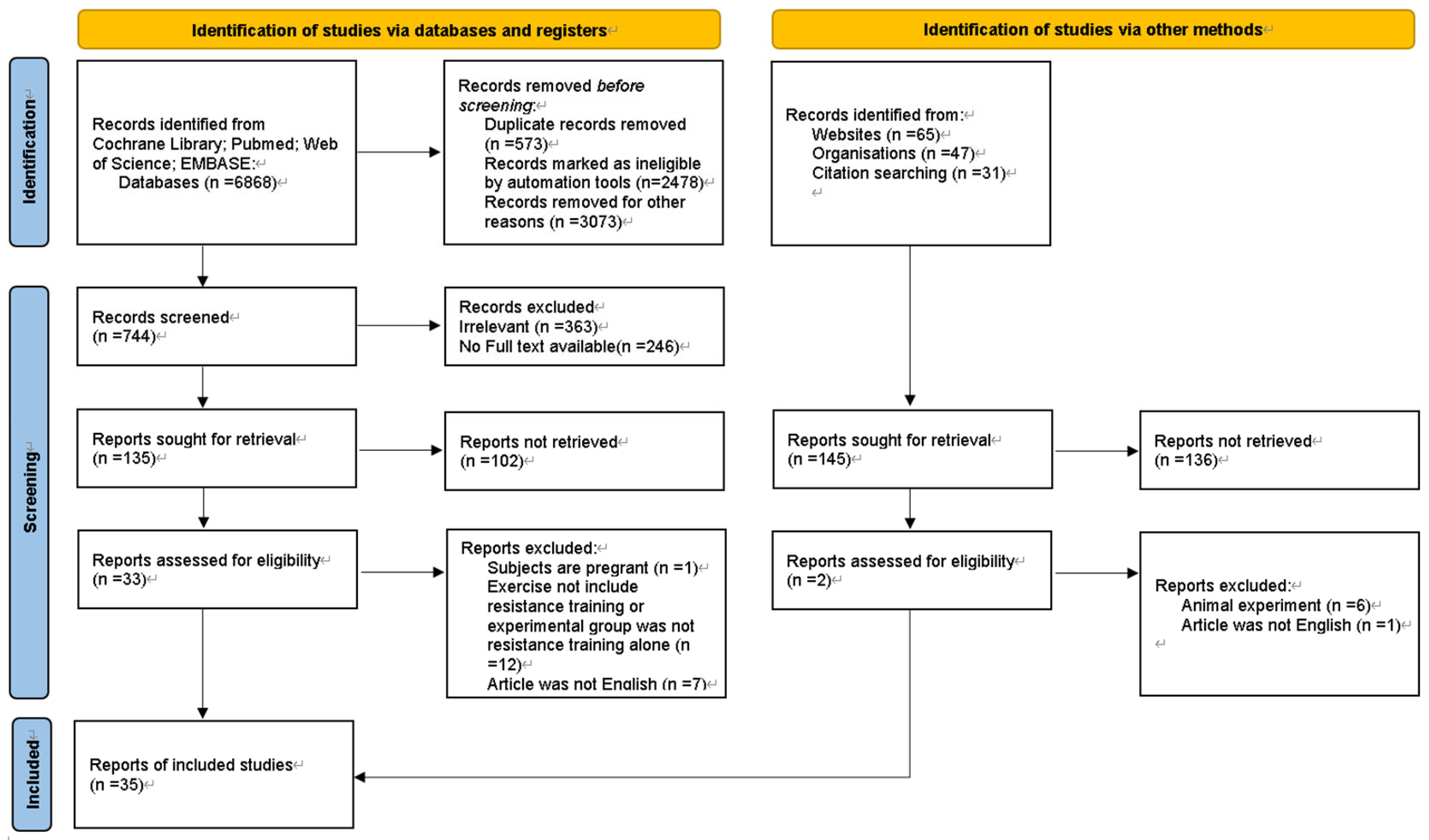

3.1. Search results

3.2. Characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Year | Samples(F/M) | Age(years) | Duration | Intervention | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dejan Reljic[29] | May-21 | 23/7 | 51.7 ± 11.7 | 12 weeks, twice a week | Weeks 1-4:50-60%1RM; Weeks 5-8:60-75%1RM; Weeks 9-12:70-80%1RM, one exercise per set | A, B, C, D, E, F, I, J, K |

| Dejan Reljic [29] | May-21 | 23/7 | 51.7 ± 11.7 | 12 weeks, three times a week | Weeks 1-4:50-60%1RM; Weeks 5-8:60-75%1RM; Weeks 9-12:70-80%1RM, three exercises per set | A, B, C, D, E, F, I, J, K |

| Javier Ibáñez [30] | Aug-09 | 12/0 | 51.4 ± 5.5 | 16 weeks, twice a week | During the first 8 weeks of the training period, subjects were loaded at 50 to 70% of the individual 1-RM, and during the last 8 weeks of the training period, the load was 70 to 80% of the maximum load. In addition, from week 8 to week 16, subjects performed a partial (20%) calf extension and bench press set-up with loads ranging from 30% to 50% of the maximum load. | A, F, G, H, I, J, K, L |

| Itamar Levinger [31] | Oct-07 | 5/9 | 51.9 ± 5.8 | 10 weeks, three times a week | With a 48-h recovery between sessions, the initial training intensity was two sets of 15-20 reps at 40-50% 1RM each. Starting in weeks 2-10, subjects performed three sets of each exercise at 50-85% 1RM for 8-20 repetitions. | A, B, C, F, I, J |

| Itamar Levinger [31] | Oct-07 | 6/4 | 48.9±7.4 | 10 weeks, three times a week | The total intervention duration was 10 weeks, with 48-h of recovery between sessions, and the initial training intensity was two sets of 15-20 reps at 40-50% 1RM. Starting in weeks 2-10, subjects performed three sets of each exercise at 50-85% 1RM for 8-20 repetitions. | A, B, C, F, I, J |

| Steven K [32] | Sep-13 | 7/0 | 20.9 ± 1.59 | 7 weeks, three times a week | At 60% 1-RM for 3 days/week and approximately 60 minutes/repetition, subjects performed three sets of 8-12 repetitions with 90-120 seconds of rest between sets. | A, F, L |

| Robert G. Memelink [33] | Dec-20 | 24/38 | 65.8 ± 6.4 | 13 weeks, three times a week | Total intervention length 13 weeks, three times a week, one hour each time | A, E, F, G, L |

| Ramin Shabani [34] | Apr-15 | 10/0 | 51.3 ± 6.63 | 12 weeks, three times a week | In the initial 1-3 weeks, the intensity is 40-50% 1-RM, 4-8 weeks, 50-65% 1-RM, with a total of 8 sets of movements, each set repeated 8-12 times, with 3 minutes rest between sets | F |

| D.W. Dunstan [35] | Feb-98 | 5/5 | 51.1 ± 2.2 | 8 weeks, three times a week | The total duration of the intervention was 8 weeks, three times a week, with a weight of 50-55% 1RM for each exercise. | B, C. F. L |

| Cíntia E. Botton [36] | Oct-18 | 8/14 | 68.6 ± 7.06 | 12 weeks, three times a week | The initial training load is determined during the familiarization training and increases with the load until a maximum of 15 repetitions is reached. | E, F, H, I, J, K |

| Sophie Drapeau [37] | Apr-11 | 22/0 | 58.5±4.6 | 24 weeks, three times a week | Phase 1: Start training (3 weeks, 15 repetitions, 2-3 sets each, 90-120 seconds between sets); Phase 2 (5 weeks, 12 repetitions, 2-3 sets each, 90 seconds between sets); Phase 3 (9 weeks, 8-10 repetitions, 2-4 sets each, 120-180 seconds between sets); Phase 4 (8 weeks, 10-12 repetitions, 3-4 sets each, 60-90 seconds between sets)) | F, G, H, I, J, K, L |

| RC Plotnikoff [38] | Jun-10 | 13/8 | 54±12 | 16 weeks, three times a week | Total intervention duration of 16 weeks, 3 training sessions per week | A, B, C, E, F, I, J, K, L |

| Mika Venojärvi [39] | Aug-12 | 0/40 | 54 ±7.2 | 12 weeks, three times a week | Increase exercise intensity and load every 4 weeks | A, B, C, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L |

| Carmen Castaneda [40] | Sep-02 | 19/12 | 66 ± 5.57 | 16 weeks, three times a week | For 45 minutes each time, subjects performed three sets of eight repetitions on each machine at a time. | A, B, C, F, H, J, K |

| Marisol García-Unciti [41] | Dec-12 | 12/0 | 51.4±5.5 | 16 weeks, twice a week | During the first 8 weeks of the training period, subjects were loaded at 50-70% of the individual 1-RM, and during the last 8 weeks of the training period, the load was 70-80% of the maximum load. | A, F, H, I, J, K, L |

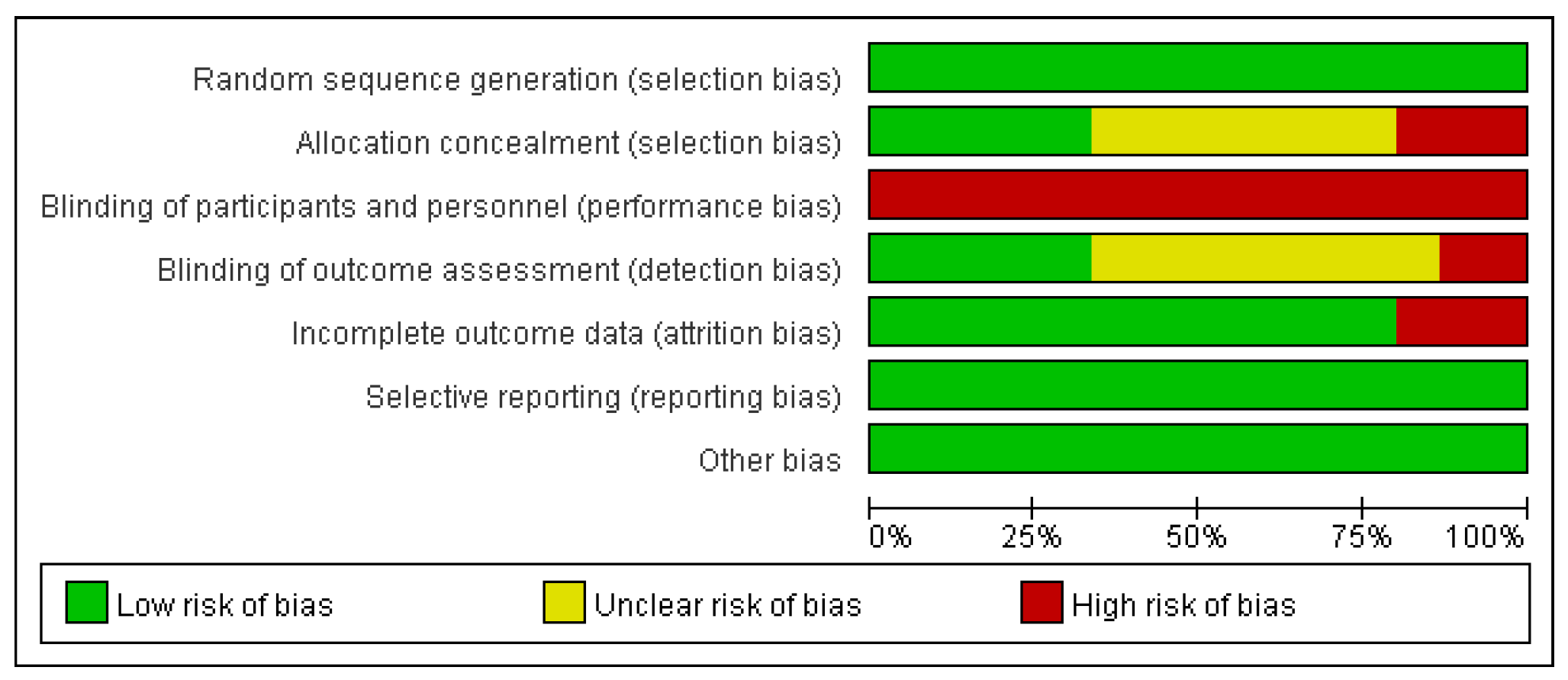

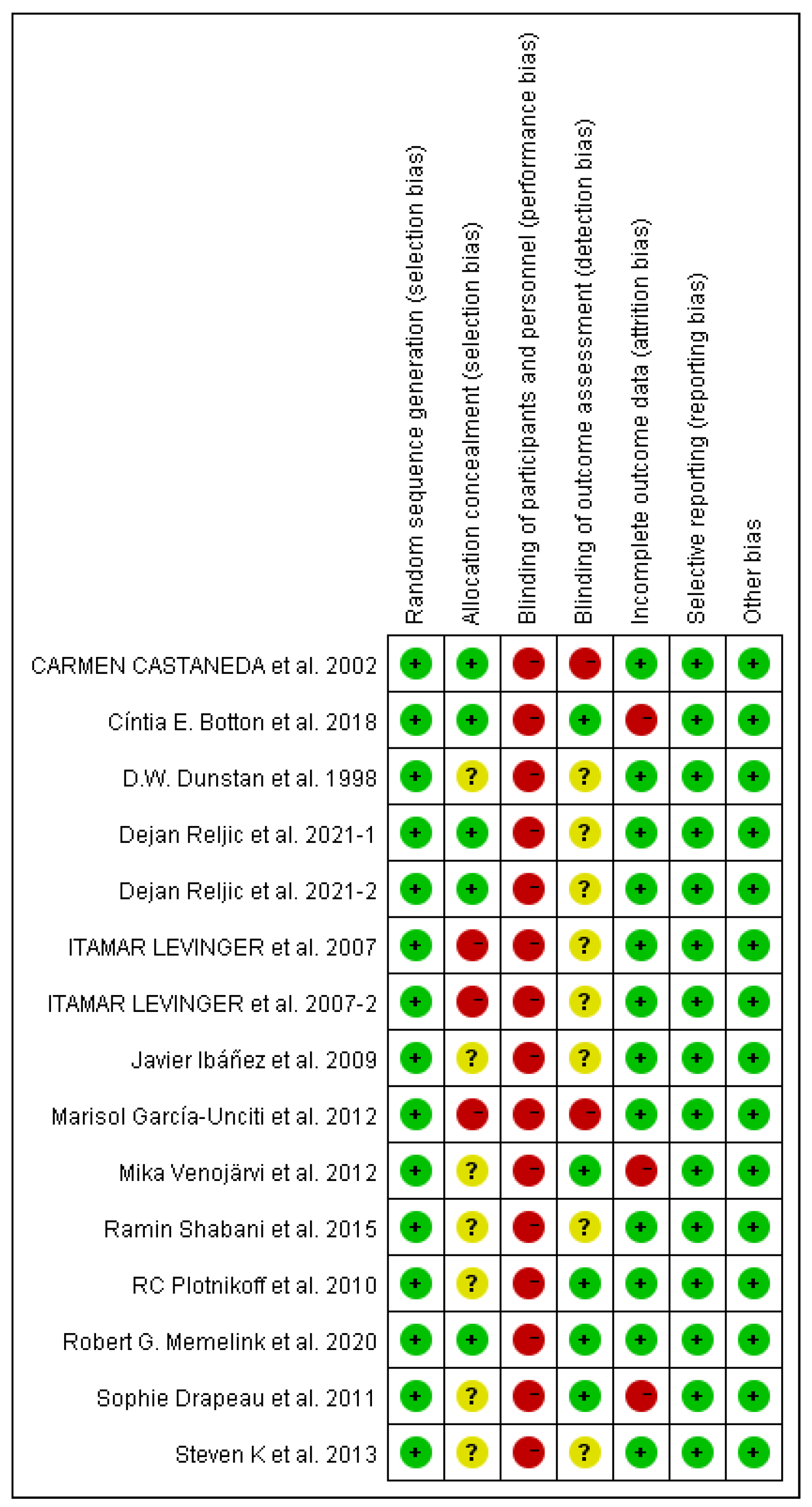

3.3. Risk of bias

3.3.1. Selection bias

3.3.2. Performance and detection bias

3.3.3. Attrition bias

3.3.4. Reporting bias

3.3.5. Publication bias

3.4. Study outcomes

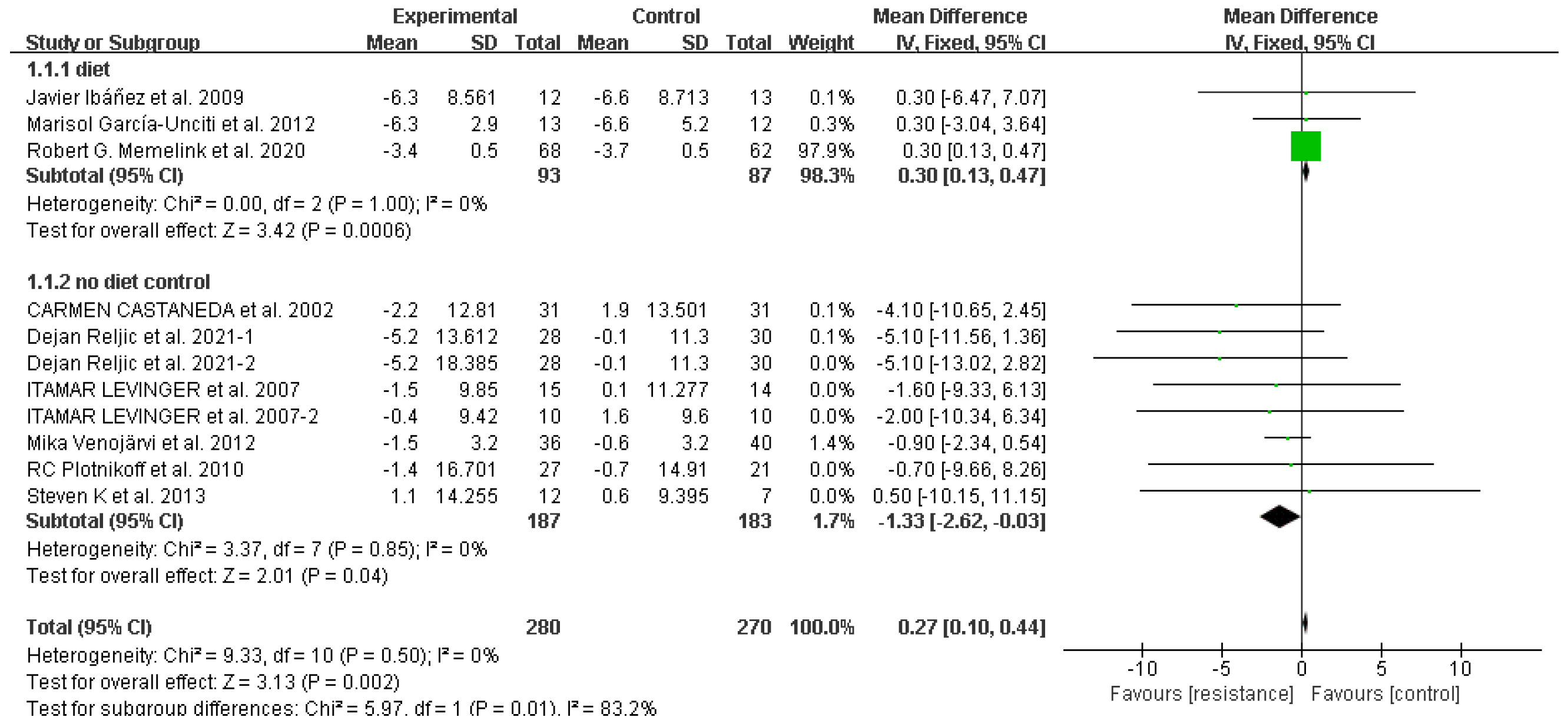

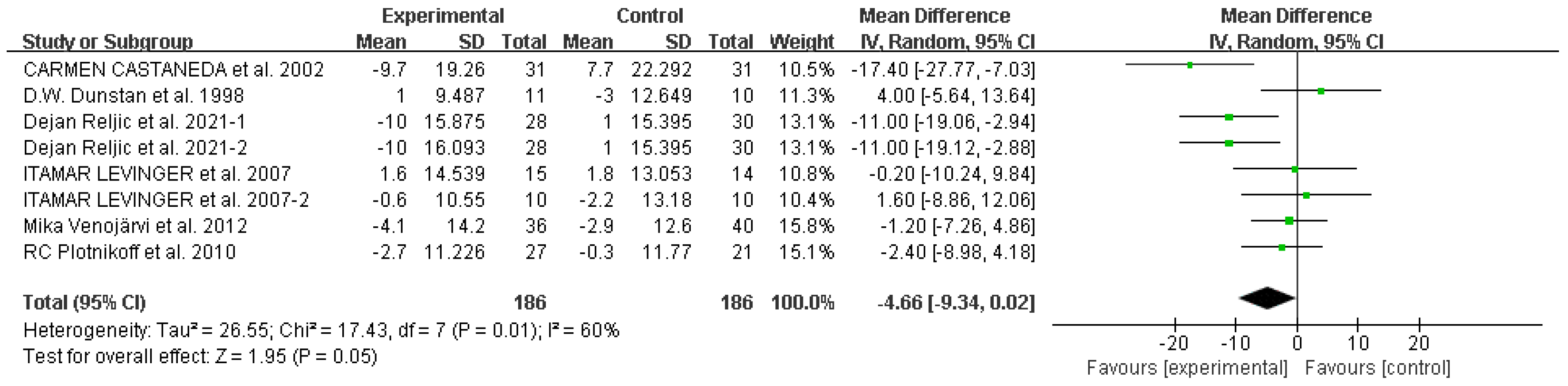

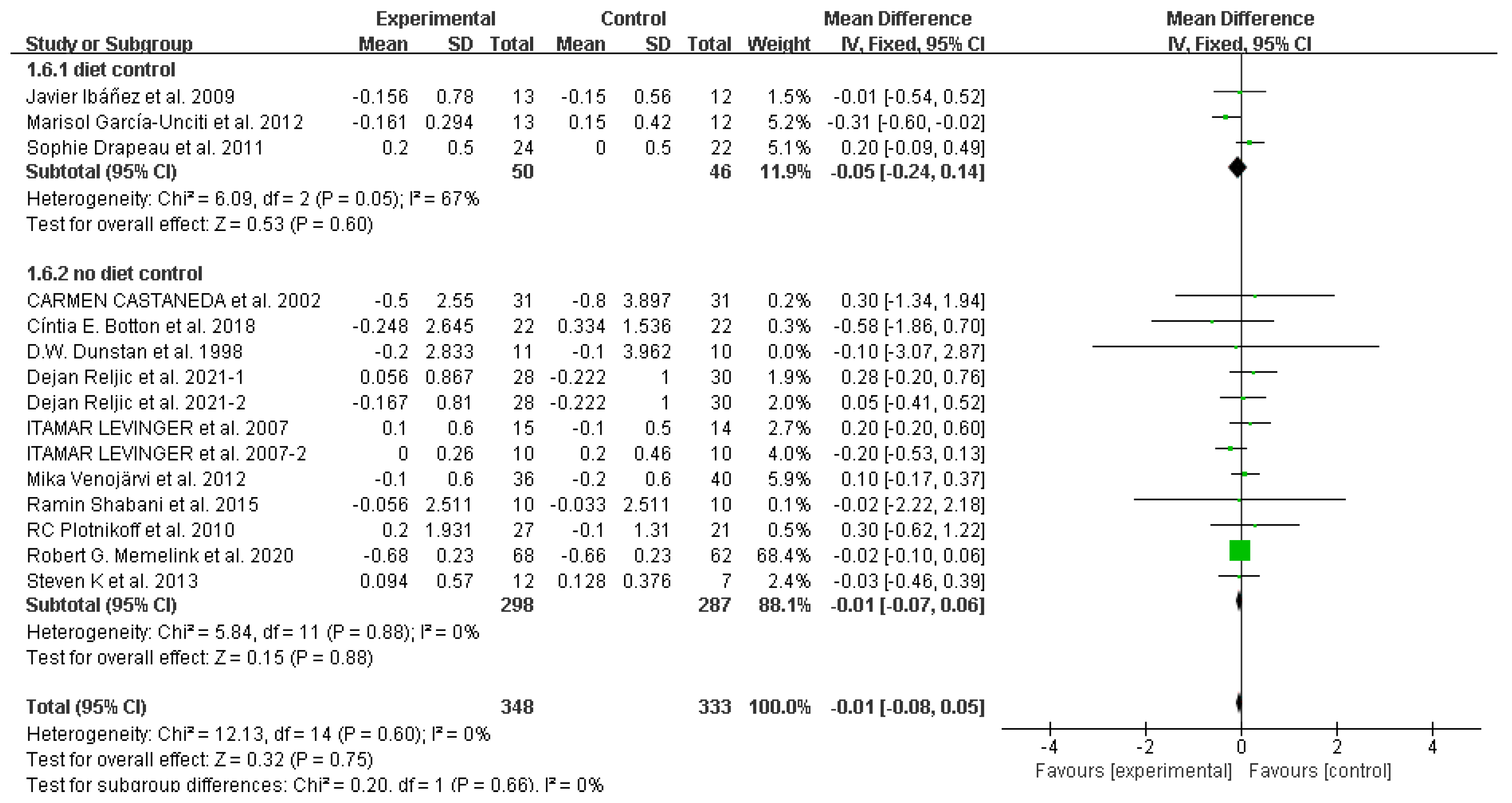

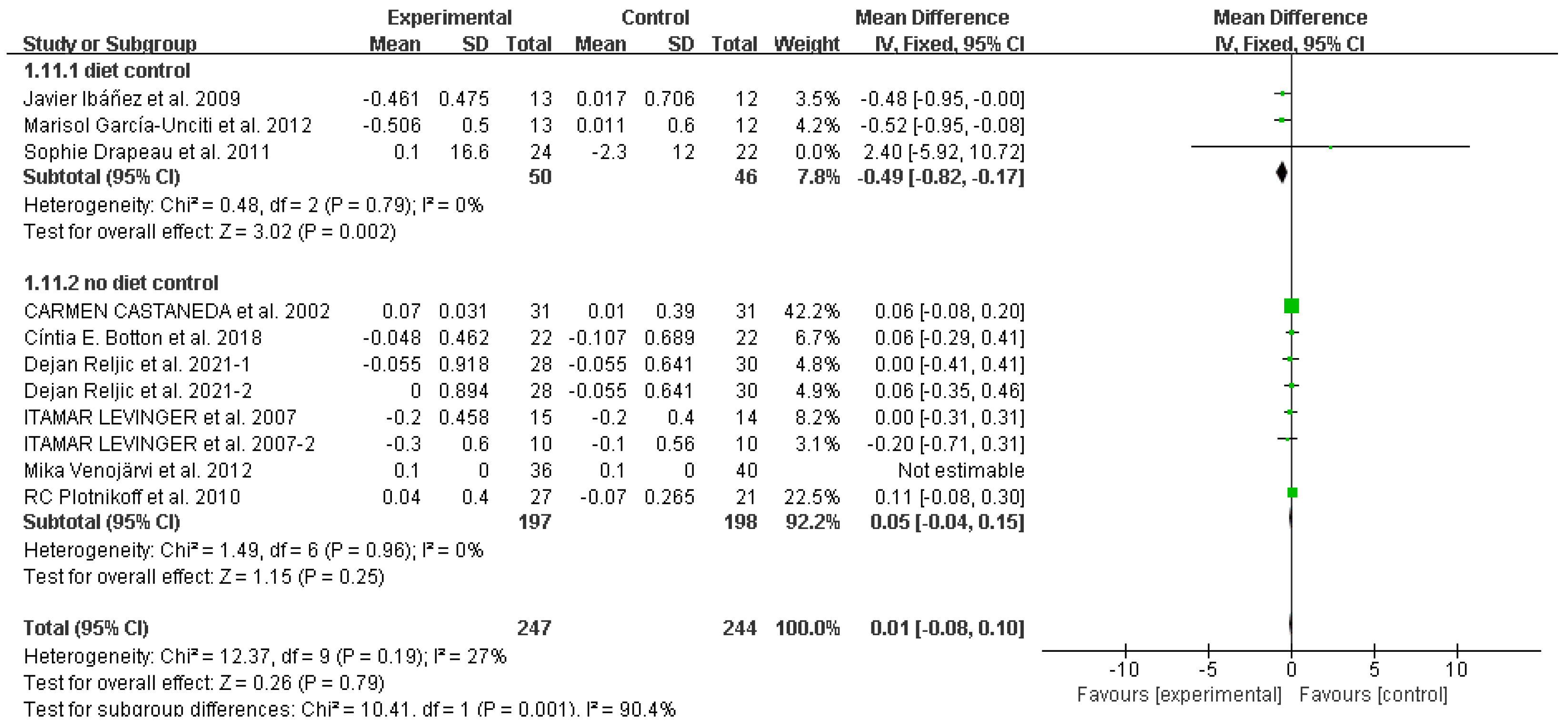

Waist

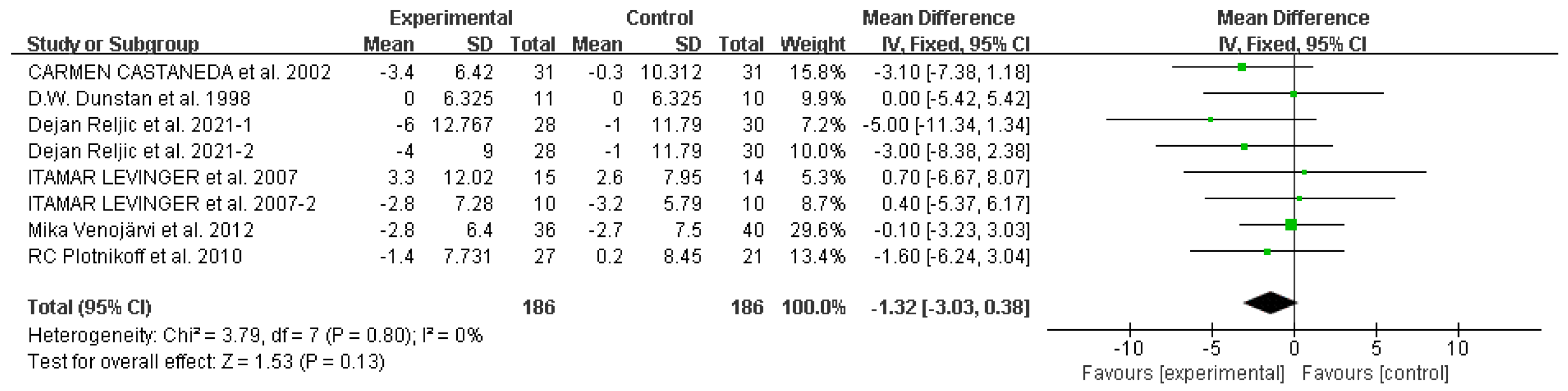

Systolic blood pressure

Diastolic blood pressure

Mean arterial pressure

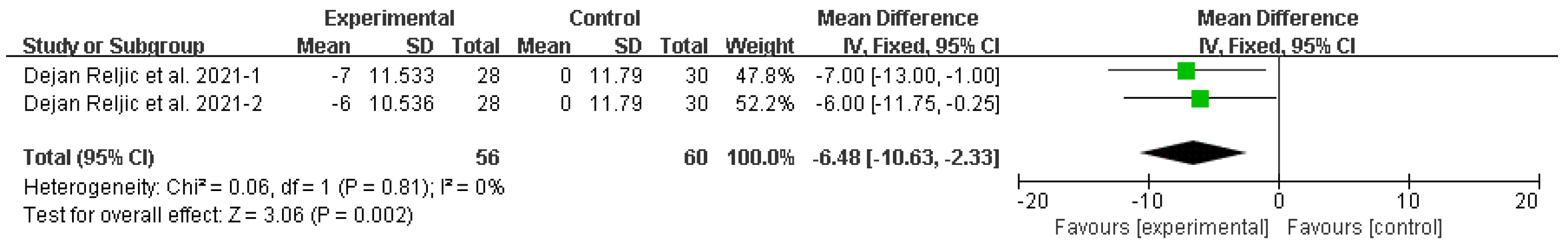

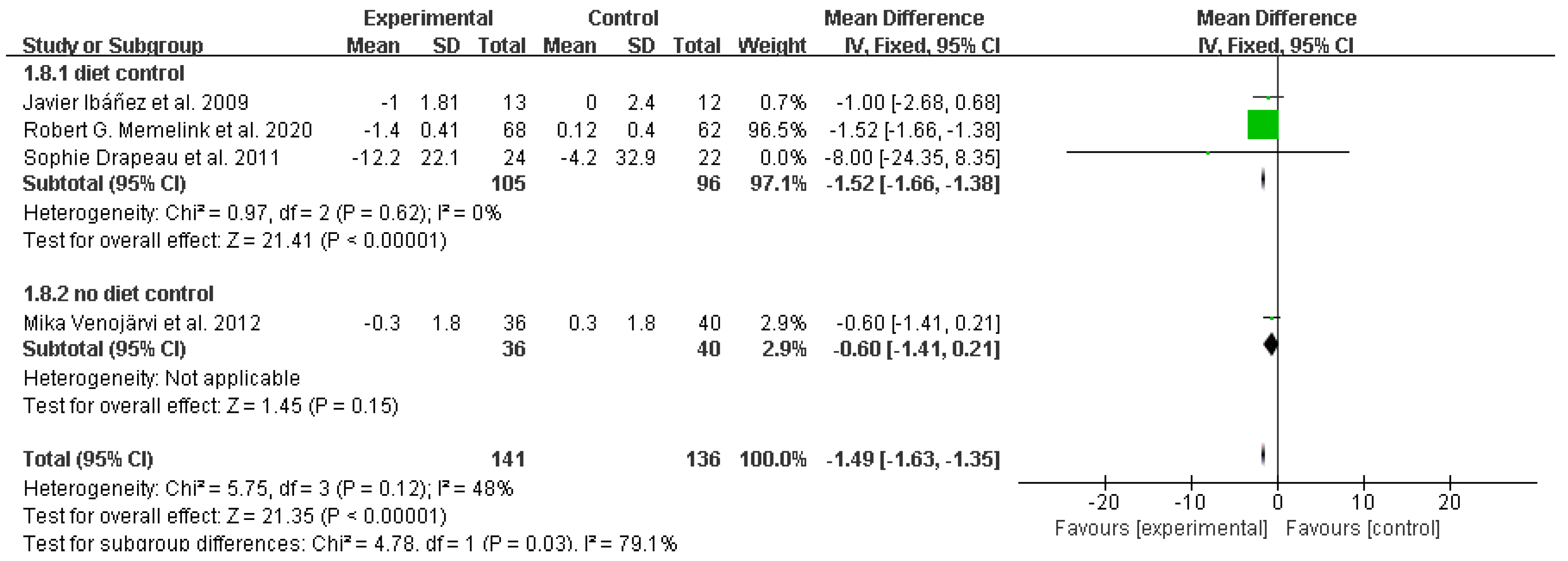

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c (%))

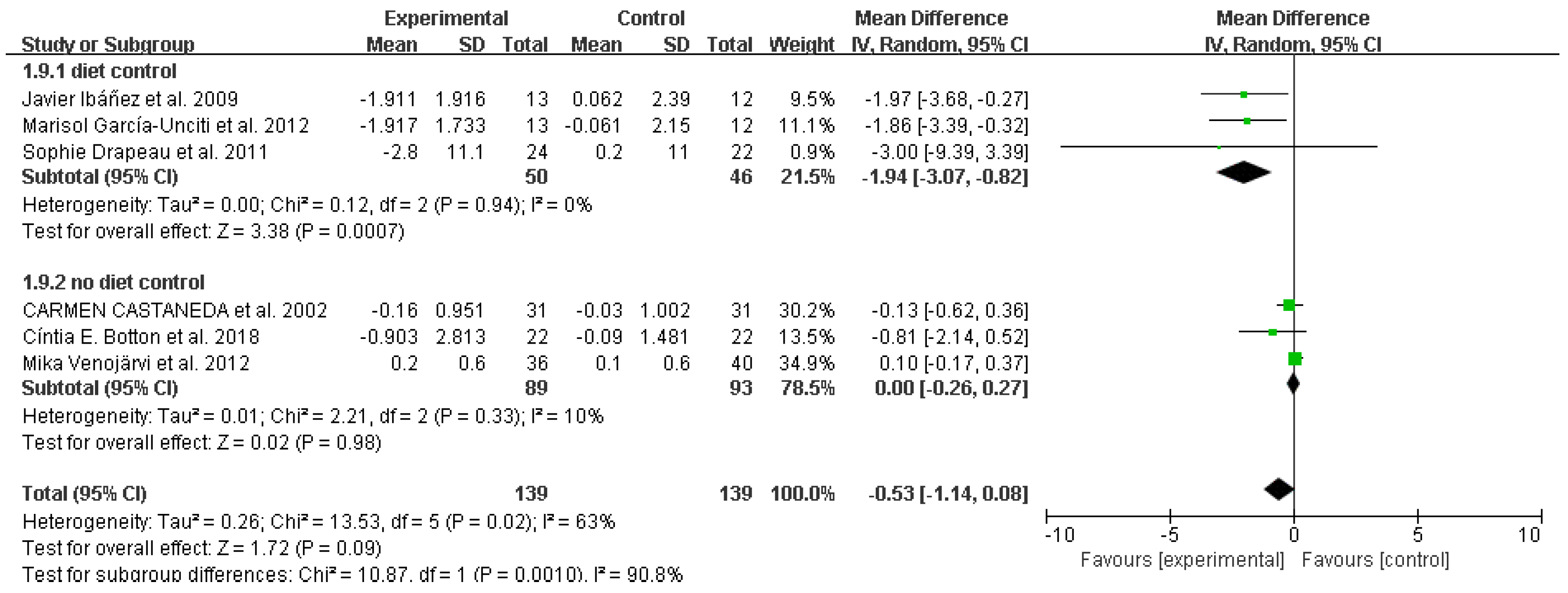

Fasting glucose

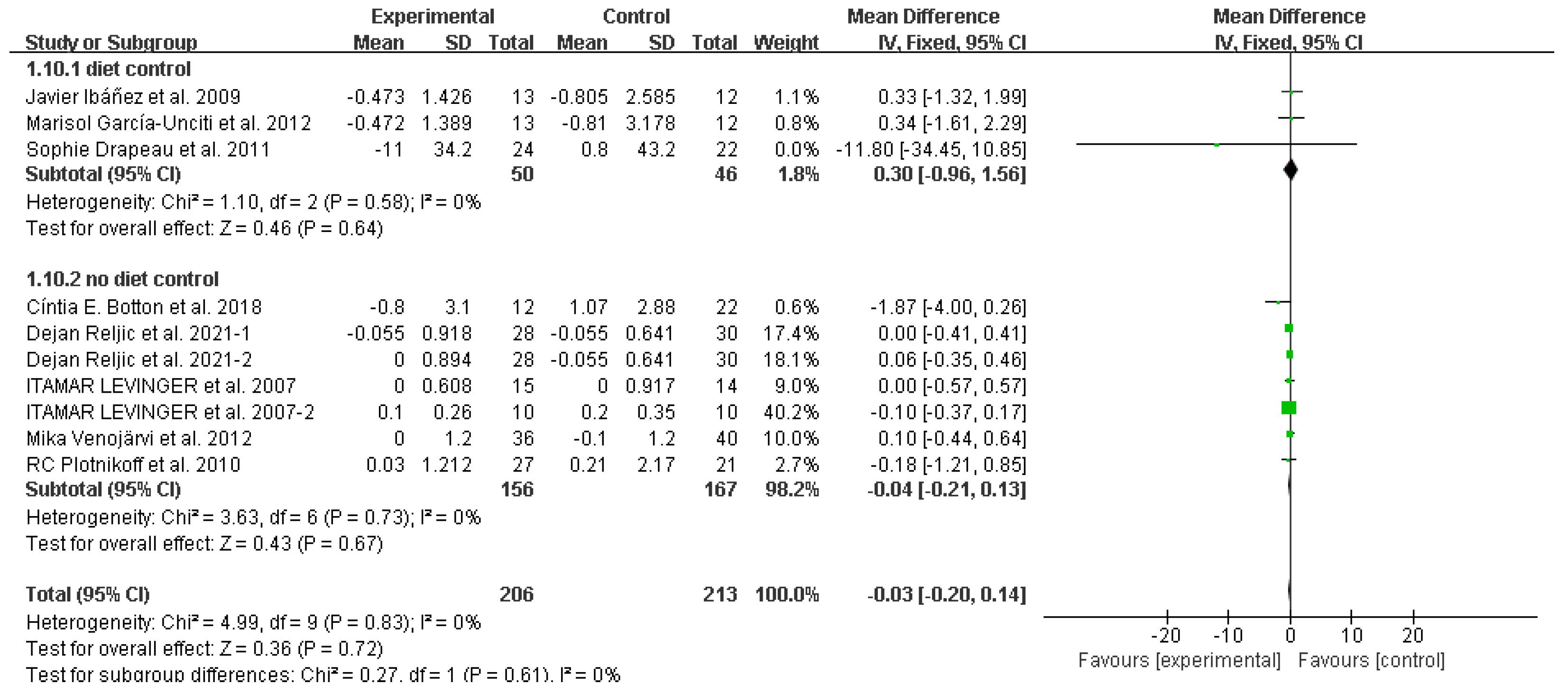

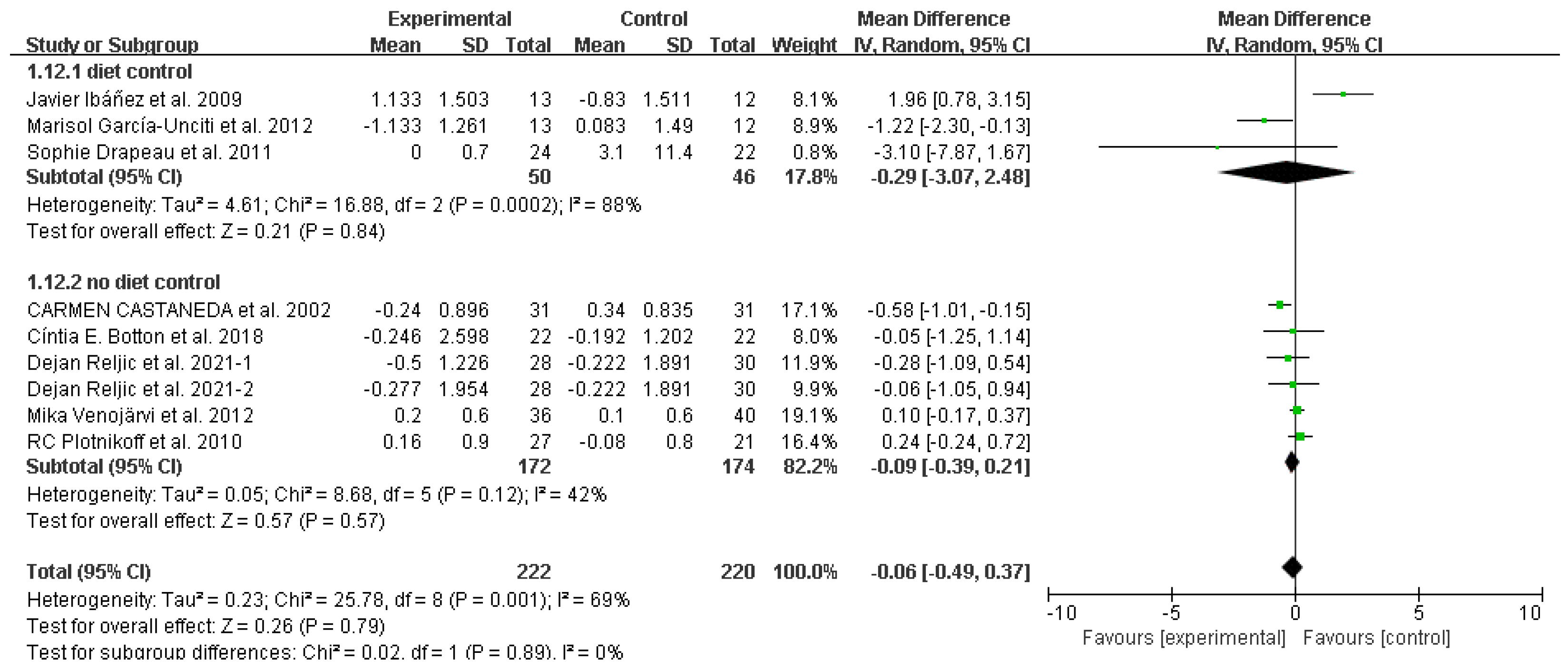

Homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance

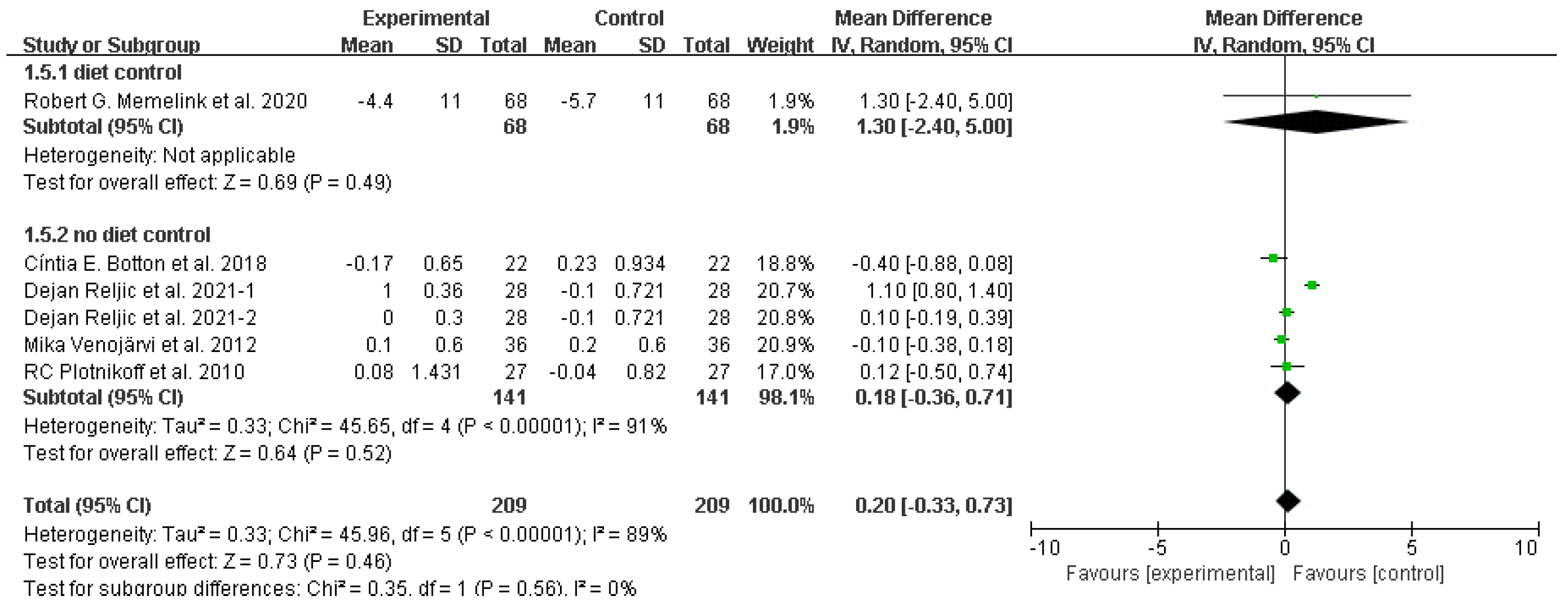

Total cholesterol

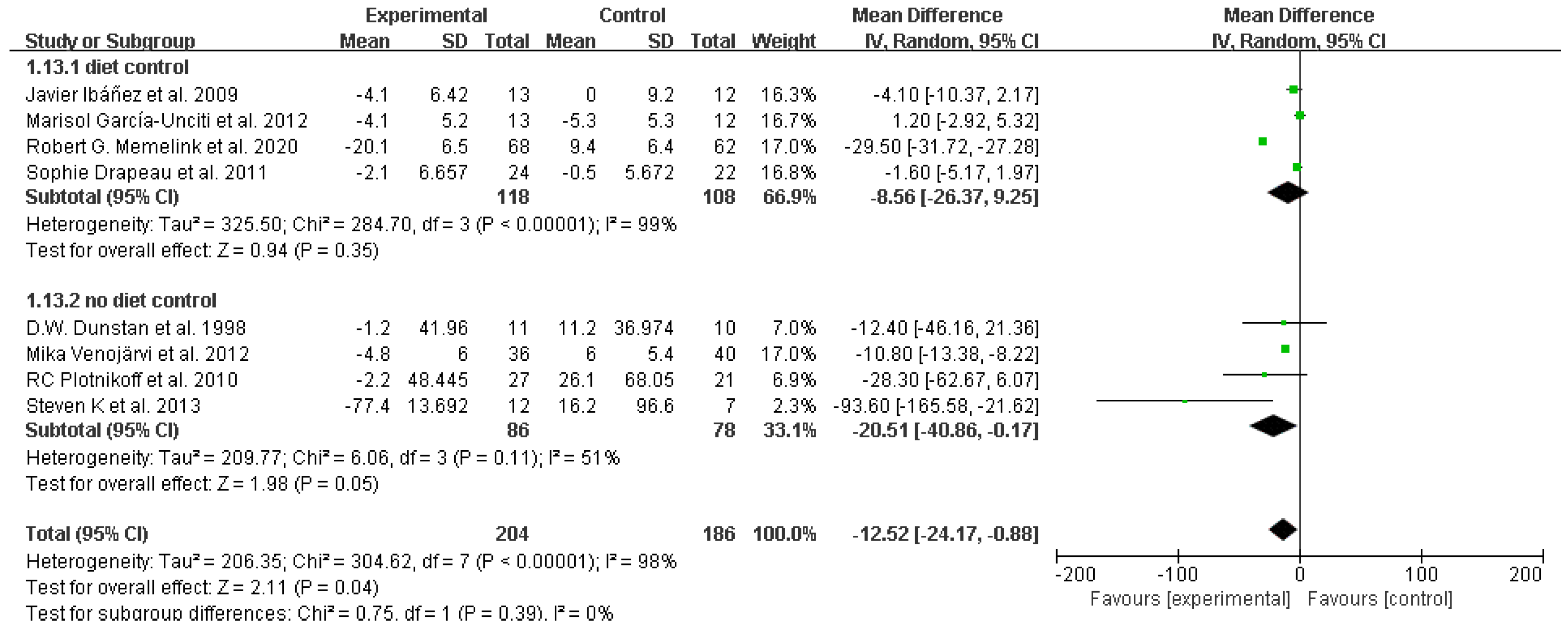

Total triglycerides

High-density lipoprotein

Low-density lipoprotein

Fasting insulin

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, Pathophysiology, and Management of Obesity. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(3):254-266.

- Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387(10026):1377-1396.

- Ortega FB, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation Research. 2016;118(11):1752-1770.

- Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(21). [CrossRef]

- Eckel RH, Kahn R, Robertson RM, Rizza RA. Preventing cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a call to action from the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2006;113(25):2943-2946.

- Lobelo F, Rohm Young D, Sallis R, et al. Routine Assessment and Promotion of Physical Activity in Healthcare Settings: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(18):e495-e522. [CrossRef]

- Lim C, Nunes EA, Currier BS, McLeod JC, Thomas ACQ, Phillips SM. An Evidence-Based Narrative Review of Mechanisms of Resistance Exercise-Induced Human Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy. Medicine and Science In Sports and Exercise. 2022;54(9):1546-1559. [CrossRef]

- Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Regulation of coronary blood flow during exercise. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88(3):1009-1086. [CrossRef]

- Yu P-C, Hsu C-C, Lee W-J, et al. Muscle-to-fat ratio identifies functional impairments and cardiometabolic risk and predicts outcomes: biomarkers of sarcopenic obesity. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 2022;13(1):368-376. [CrossRef]

- Hong S-H, Choi KM. Sarcopenic Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Their Implications in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Consequences. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(2). [CrossRef]

- Murach KA, Dimet-Wiley AL, Wen Y, et al. Late-life exercise mitigates skeletal muscle epigenetic aging. Aging Cell. 2022;21(1):e13527. [CrossRef]

- Hurst C, Robinson SM, Witham MD, et al. Resistance exercise as a treatment for sarcopenia: prescription and delivery. Age Ageing. 2022;51(2). [CrossRef]

- Armstrong A, Jungbluth Rodriguez K, Sabag A, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on waist circumference in adults with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews : an Official Journal of the International Association For the Study of Obesity. 2022;23(8):e13446. [CrossRef]

- Umpierre D, Ribeiro PAB, Schaan BD, Ribeiro JP. Volume of supervised exercise training impacts glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review with meta-regression analysis. Diabetologia. 2013;56(2):242-251. [CrossRef]

- Mañas A, Gómez-Redondo P, Valenzuela PL, Morales JS, Lucía A, Ara I. Unsupervised home-based resistance training for community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ageing Research Reviews. 2021;69:101368. [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine and Science In Sports and Exercise. 2009;41(3):687-708.

- Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine and Science In Sports and Exercise. 2009;41(2):459-471. [CrossRef]

- Amaro-Gahete FJ, Ponce-González JG, Corral-Pérez J, Velázquez-Díaz D, Lavie CJ, Jiménez-Pavón D. Effect of a 12-Week Concurrent Training Intervention on Cardiometabolic Health in Obese Men: A Pilot Study. Frontiers In Physiology. 2021;12:630831. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva MAR, Baptista LC, Neves RS, et al. The Effects of Concurrent Training Combining Both Resistance Exercise and High-Intensity Interval Training or Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training on Metabolic Syndrome. Frontiers In Physiology. 2020;11:572. [CrossRef]

- Wilson JM, Marin PJ, Rhea MR, Wilson SMC, Loenneke JP, Anderson JC. Concurrent training: a meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2012;26(8):2293-2307.

- Edwards JJ, Griffiths M, Deenmamode AHP, O'Driscoll JM. High-Intensity Interval Training and Cardiometabolic Health in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zheng L, Qin R, Rao Z, Xiao W. High-intensity interval training induces renal injury and fibrosis in type 2 diabetic mice. Life Sciences. 2023;324:121740. [CrossRef]

- Quindry JC, Franklin BA, Chapman M, Humphrey R, Mathis S. Benefits and Risks of High-Intensity Interval Training in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2019;123(8):1370-1377. [CrossRef]

- Fyfe JJ, Hamilton DL, Daly RM. Minimal-Dose Resistance Training for Improving Muscle Mass, Strength, and Function: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and Practical Considerations. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2022;52(3):463-479. [CrossRef]

- Ashton RE, Tew GA, Aning JJ, Gilbert SE, Lewis L, Saxton JM. Effects of short-term, medium-term and long-term resistance exercise training on cardiometabolic health outcomes in adults: systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020;54(6):341-348. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

- Sutton AJ, Song F, Gilbody SM, Abrams KR. Modelling publication bias in meta-analysis: a review. Stat Methods Med Res. 2000;9(5):421-445.

- Reljic D, Herrmann HJ, Neurath MF, Zopf Y. Iron Beats Electricity: Resistance Training but Not Whole-Body Electromyostimulation Improves Cardiometabolic Health in Obese Metabolic Syndrome Patients during Caloric Restriction-A Randomized-Controlled Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(5). [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez J, Izquierdo M, Martínez-Labari C, et al. Resistance training improves cardiovascular risk factors in obese women despite a significative decrease in serum adiponectin levels. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2010;18(3):535-541. [CrossRef]

- Levinger I, Goodman C, Matthews V, et al. BDNF, metabolic risk factors, and resistance training in middle-aged individuals. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2008;40(3):535-541. [CrossRef]

- Malin SK, Hinnerichs KR, Echtenkamp BG, Evetovich TK, Engebretsen BJ. Effect of adiposity on insulin action after acute and chronic resistance exercise in non-diabetic women. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2013;113(12):2933-2941. [CrossRef]

- Memelink RG, Pasman WJ, Bongers A, et al. Effect of an Enriched Protein Drink on Muscle Mass and Glycemic Control during Combined Lifestyle Intervention in Older Adults with Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Double-Blind RCT. Nutrients. 2020;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Shabani R, Nazari M, Dalili S, Rad AH. Effect of Circuit Resistance Training on Glycemic Control of Females with Diabetes Type II. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:34. [CrossRef]

- Dunstan DW, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ, Burke V, Morton AR, Stanton KG. Effects of a short-term circuit weight training program on glycaemic control in NIDDM. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 1998;40(1):53-61. [CrossRef]

- Botton CE, Umpierre D, Rech A, et al. Effects of resistance training on neuromuscular parameters in elderly with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized clinical trial. Exp Gerontol. 2018;113:141-149. [CrossRef]

- Drapeau S, Doucet E, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Brochu M, Prud'homme D, Imbeault P. Improvement in insulin sensitivity by weight loss does not affect hyperinsulinemia-mediated reduction in total and high molecular weight adiponectin: a MONET study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36(2):191-200. [CrossRef]

- Plotnikoff RC, Eves N, Jung M, Sigal RJ, Padwal R, Karunamuni N. Multicomponent, home-based resistance training for obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Obesity. 2010;34(12):1733-1741. [CrossRef]

- Venojärvi M, Wasenius N, Manderoos S, et al. Nordic walking decreased circulating chemerin and leptin concentrations in middle-aged men with impaired glucose regulation. Ann Med. 2013;45(2):162-170. [CrossRef]

- Castaneda C, Layne JE, Munoz-Orians L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training to improve glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2335-2341. [CrossRef]

- García-Unciti M, Izquierdo M, Idoate F, et al. Weight-loss diet alone or combined with progressive resistance training induces changes in association between the cardiometabolic risk profile and abdominal fat depots. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;61(4):296-304. [CrossRef]

- Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, et al. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: a consensus statement from shaping America's health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1647-1652.

- Tchernof A, Després J-P. Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiological Reviews. 2013;93(1):359-404. [CrossRef]

- Leenen R, van der Kooy K, Deurenberg P, et al. Visceral fat accumulation in obese subjects: relation to energy expenditure and response to weight loss. The American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263(5 Pt 1):E913-E919. [CrossRef]

- van der Kooy K, Leenen R, Seidell JC, Deurenberg P, Droop A, Bakker CJ. Waist-hip ratio is a poor predictor of changes in visceral fat. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1993;57(3):327-333. [CrossRef]

- Kordi R, Dehghani S, Noormohammadpour P, Rostami M, Mansournia MA. Effect of abdominal resistance exercise on abdominal subcutaneous fat of obese women: a randomized controlled trial using ultrasound imaging assessments. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(3):203-209. [CrossRef]

- Vispute SS, Smith JD, LeCheminant JD, Hurley KS. The effect of abdominal exercise on abdominal fat. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2011;25(9):2559-2564. [CrossRef]

- Drapeau S, Doucet E, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Brochu M, Prud'homme D, Imbeault P. Improvement in insulin sensitivity by weight loss does not affect hyperinsulinemia-mediated reduction in total and high molecular weight adiponectin: a MONET study. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition Et Metabolisme. 2011;36(2):191-200. [CrossRef]

- Chudyk A, Petrella RJ. Effects of exercise on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(5):1228-1237.

- Yang Z, Scott CA, Mao C, Tang J, Farmer AJ. Resistance exercise versus aerobic exercise for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, NZ). 2014;44(4):487-499. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen VA, Fagard RH. Effects of endurance training on blood pressure, blood pressure-regulating mechanisms, and cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 2005;46(4):667-675. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen VA, Fagard RH, Coeckelberghs E, Vanhees L. Impact of resistance training on blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 2011;58(5):950-958.

- Gao Y, Wang Q, Li J, et al. Impact of Mean Arterial Pressure Fluctuation on Mortality in Critically Ill Patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2018;46(12):e1167-e1174. [CrossRef]

- Sun S, Lo K, Liu L, et al. Association of mean arterial pressure with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in young adults. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96(1138):455-460. [CrossRef]

- Miyai N, Shiozaki M, Yabu M, et al. Increased mean arterial pressure response to dynamic exercise in normotensive subjects with multiple metabolic risk factors. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(6):534-539. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1615-1625.

- Yang W. Diagnosing diabetes using glycated haemoglobin A1c. BMJ. 2010;340:c2262. [CrossRef]

- Sylow L, Kleinert M, Richter EA, Jensen TE. Exercise-stimulated glucose uptake - regulation and implications for glycaemic control. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2017;13(3):133-148. [CrossRef]

- Evans PL, McMillin SL, Weyrauch LA, Witczak CA. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Glucose Transport and Glucose Metabolism by Exercise Training. Nutrients. 2019;11(10). [CrossRef]

- Rossello X, Raposeiras-Roubin S, Oliva B, et al. Glycated Hemoglobin and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in People Without Diabetes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021;77(22):2777-2791. [CrossRef]

- Khaw K-T, Wareham N. Glycated hemoglobin as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Current Opinion In Lipidology. 2006;17(6):637-643. [CrossRef]

- Malka R, Nathan DM, Higgins JM. Mechanistic modeling of hemoglobin glycation and red blood cell kinetics enables personalized diabetes monitoring. Science Translational Medicine. 2016;8(359):359ra130. [CrossRef]

- Hu M, Lin W. Effects of exercise training on red blood cell production: implications for anemia. Acta Haematol. 2012;127(3):156-164. [CrossRef]

- Montero D, Lundby C. Regulation of Red Blood Cell Volume with Exercise Training. Comprehensive Physiology. 2018;9(1):149-164.

- Montero D, Breenfeldt-Andersen A, Oberholzer L, et al. Erythropoiesis with endurance training: dynamics and mechanisms. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2017;312(6):R894-R902. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Delgado F, Katsiki N, Lopez-Miranda J, Perez-Martinez P. Dietary habits, lipoprotein metabolism and cardiovascular disease: From individual foods to dietary patterns. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;61(10):1651-1669. [CrossRef]

- Huang G, Xu J, Zhang Z, Cai L, Liu H, Yu X. Total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is associated with metabolic syndrome in a very elderly Chinese population. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):15212. [CrossRef]

- Chait A, Ginsberg HN, Vaisar T, Heinecke JW, Goldberg IJ, Bornfeldt KE. Remnants of the Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. Diabetes. 2020;69(4):508-516. [CrossRef]

- Cho K-H. The Current Status of Research on High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL): A Paradigm Shift from HDL Quantity to HDL Quality and HDL Functionality. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23(7). [CrossRef]

- Hasvold P, Thuresson M, Sundström J, et al. Association Between Paradoxical HDL Cholesterol Decrease and Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients Initiated on Statin Treatment in a Primary Care Setting. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(3):225-233. [CrossRef]

- de Salles BF, Simão R, Fleck SJ, Dias I, Kraemer-Aguiar LG, Bouskela E. Effects of resistance training on cytokines. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2010;31(7):441-450. [CrossRef]

- Libardi CA, De Souza GV, Cavaglieri CR, Madruga VA, Chacon-Mikahil MPT. Effect of resistance, endurance, and concurrent training on TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP. Medicine and Science In Sports and Exercise. 2012;44(1):50-56.

- Sañudo B, Alfonso-Rosa R, Del Pozo-Cruz B, Del Pozo-Cruz J, Galiano D, Figueroa A. Whole body vibration training improves leg blood flow and adiposity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2013;113(9):2245-2252. [CrossRef]

- Williams MA, Haskell WL, Ades PA, et al. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2007;116(5):572-584.

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Adults with overweight and obesity |

| Intervention | Resistance training |

| Comparators | No additional physical exercise |

| Outcomes | Waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, variables related to glucose metabolism and lipids, including glycated hemoglobin, fasting glucose, balance model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, fasting insulin |

| Study design | All randomized controlled trials |

| #1 resistance training [Mesh] |

| #2 training, resistance OR strength training OR training, strength OR weight-lifting OR strengthening program OR strengthening program OR weight-lifting OR strengthening programs OR weight-lifting OR weight lifting strengthening program OR weight-lifting strengthening programs OR weight-lifting exercise program OR exercise program OR exercise programs OR weight lifting exercise program OR weight-lifting exercise programs OR weight-bearing strengthening program OR strengthening program OR weight-bearing OR strengthening programs OR weight-bearing OR weight bearing strengthening program OR weight-bearing strengthening programs OR weight-bearing exercise program OR exercise program OR weight-bearing OR exercise programs OR weight-bearing OR weight-bearing exercise program OR weight-bearing exercise programs |

| #3 #1 OR #2 |

| #4 obesity [Mesh] |

| #5 appetite depressants OR body weight OR diet, reducing OR skinfold thickness OR lipectomy OR anti-obesity agents OR bariatrics |

| #6 #4 OR #5 |

| #7 overweight [Mesh] |

| #8 glucose metabolism disorders [Mesh] |

| #9 disorder, glucose metabolism OR disorders, glucose metabolism OR metabolism disorder, glucose OR metabolism disorders, glucose OR glucose metabolic disorders OR glucose metabolic disorders OR disorder, glucose metabolic OR disorders, glucose metabolic OR metabolic disorder, glucose OR metabolic disorders, glucose OR glucose metabolism disorder OR glucose metabolic disorder |

| #10 #8 OR #9 |

| #11 Lipid metabolism [Mesh] |

| #12 Metabolism, lipid OR lipid metabolism disorder OR metabolism disorder, lipid OR metabolism disorders, lipid |

| #13 #11 OR #12 |

| #14 Glycated hemoglobin OR Fasting plasma glucose OR Homeostatic model assessment-B cell function OR Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance OR Triglycerides OR Total-cholesterol OR HDL-cholesterol OR LDL-cholesterol OR insulin |

| #15 randomized controlled trial [Publication Type] |

| #16 randomized OR RCT |

| #17 #15 OR #16 |

| #18 #3 AND #6 AND #10 AND #13 AND #17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).