Results

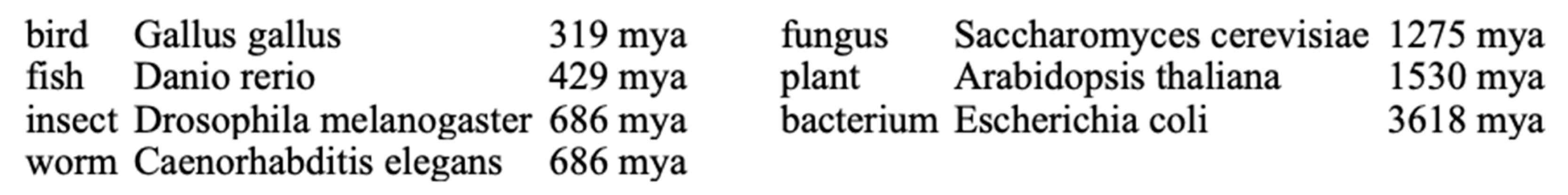

Table 1 provides a list of forty mammals studied. It includes scientific and common names, whole genome size (in Gbp), number of protein coding DNA sequences (CDS), and a three-letter code so their names need not be written in full every time. This code consists of a Capitalized first letter matching the first letter of the genus followed by two lower case letters indicating the first two letters of the species. In three cases, this is insufficient to distinguish among them, so a second letter for genus is used: Mamu for

Macaca mulatta, Mimu for

Microcebus murinus, Mumu for

Mus musculus. Gbp and CDS values were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; accessed November 2021). These numbers may be outdated, but are sufficient for background, playing no role in the analyses undertaken.

Table S1 provides phylogenetic divergence in a grid of pairwise species separation times for easy reference, and recorded in units of

million years ago (mya). It is symmetrical along the diagonal (upper left → lower right), so only half is displayed for clarity. When examining

Table S1, search for the cell intersecting the appropriate column/row combination for those species of interest. Complete scientific names are given in the first column, but each row is headed by the abbreviation code. Oan is an unanticipated outlier, as it diverged from the thirty-nine other species 180 mya.

Many results uncovered by studying tRNA sequences from Archaea (Laibelman 2022) are here reified either in their entirety or slightly modified. Additional outcomes emerge only upon exploring the much larger numbers of strings necessarily incorporated into the more complex biochemistry innate to multicellular Eukarya in comparison with unicellular Archaea. Isoacceptors refers to sets of mRNA codon triplets translated into one amino acid according to the notion of codon degeneracy (redundancy). Since mRNA codons always act in conjunction with aminoacylated tRNA in a 1:1 relation, isoacceptors will likewise refer to relevant anticodon triplet tRNA. Isodecoder is employed when tRNA with an identical anticodon triplet encode nucleotide differences elsewhere when comparing entire sequences (Goodenbour and Pan 2006). In the Archaea paper, they are called unique sequences (unique strings): 186 organisms cumulatively encode 8869 sequences (4658 unique, 52.5%) for an average of ~48 strings per genome. Here, forty mammalian Eukarya generate 19,776 (12,578 unique, 63.6%), averaging ~494 per species.

Nonetheless, the most essential findings from that prior research are confirmed. Above all, it can no longer be doubted that, as forcefully advocated, The Standard Genetic Code Lacks Redundancy for Amino Acid Codons. This assessment constitutes a major departure from current dogma and demands a rethinking, and revision, of several core beliefs about genetics as revealed through genomics. Like the Archaea, mammalian Eukarya tRNA sequences display diversity in characteristics for every isoacceptor regardless of associated amino acid. Although the Standard Genetic Code interpretation suggests equality among codon triplets for specific residues after translation, this image offers a fundamentally incomplete and inaccurate picture. It is crucial to look at information provided by aminoacylated tRNA sequences bound to codon triplets. The range of properties exhibited by different anticodon triplets associated with single amino acids offers sufficient evidence to remove any semblance of degeneracy.

As in Archaea, the lengths of encoded tRNA strings in animals vary greatly per isoacceptor. The preferred length in number of nucleotides (nt) is defined as the largest number of total sequences for that anticodon triplet expressed in each genome. Glycine, for example, displays as preferred lengths:

39 sequences tRNAGly(ACC) → 73 nt (2×), 74 nt (1×)

388 sequences tRNAGly(CCC) → 71 nt (36×), 73 nt (4×)

540 sequences tRNAGly(GCC) → 71 nt (40×)

435 sequences tRNAGly(UCC) → 71 nt (2×), 72 nt (36×), 73 nt (2×)

The full range of expressed string lengths for glycine-associated tRNA covers 64−78 nt.

Table S2 proves this is not an isolated cherry-picked example; length variance is typically found for 62 anticodon triplets (standard sixty-one plus UCA for selenocysteine). In general, there is a narrower range of tRNA lengths in these Eukarya than in Archaea, in part because forty of the former are tabulated as opposed to 186 of the latter. Preferred length for glycine isoacceptors is the same for tRNA

Gly(CCC), but different for tRNA

Gly(GCC) and tRNA

Gly(UCC); tRNA

Gly(ACC) has just one representative among these Archaea.

Table S2 offers a breakdown by animal and isoacceptor, with preferred length shown in

bold red font.

Table S3 summarizes preferred length distributions by isoacceptor; ties in length are listed as paired values; for example, 72/76 is a column heading indicating one species (Mlu according to

Table S2) for which these lengths tie as most times found in tRNA

Pro(UGG). Only tRNA

Ala(AGC) and tRNA

Thr(CGU) display variability in preferred length, with the former invoking a species split between 72 nt (nineteen genomes) and 73 nt (twenty genomes), plus a 72/73 nt tie (one genome). For threonine isoacceptor, there is a wide spread favored: 72 nt (10×), 73 nt (2×), 74 nt (6×), 72/74 nt (17×), 72/73/74 nt (4×), 72/73/74/75 nt (1×). A meaning for length variability is presented in the Discussion. It cannot be presumed inconsequential, and the array illustrated by glycine-connected anticodons suffices to break degeneracy when tRNA are bound at the ribosomal A site with their correlate mRNA codon triplets.

What Goodenbour & Pan (2006) denominated as isodecoders applies to a greater extent than they focused on in their paper. They looked at eleven Eukarya including Cfa, Hsa, Mumu, Ptr, Rno. Their definition of isodecoders removed the most abundant differently sequenced string from the count; hence, their number of isodecoders per isoacceptor is relative to that string most often encoded by identical sequences. Neither in the Archaea survey nor here is this distinction made: the definition of unique tRNA equals the Goodenbour & Pan number plus one, representing an absolute value. Henceforth, isodecoders will be used interchangeably with unique.

It was mentioned that of 8869 archaeal tRNA sequences, 4658 are unique (52.5%), and of 19,776 eukaryl tRNA, 12,578 are unique (63.6%). A higher uniqueness percentage for Eukarya than Archaea is not surprising. If sequence variations in tRNA strings exist, there should be a greater number (larger percentage) in structurally and functionally more complex organisms

when nucleotide differences in any position are meaningful.

Table 2 displays raw totals and percentages: (i) with all anticodon triplets considered; (ii) with suppressor genes and undetermined anticodons (tRNA

Undet(NNN)) removed. The second condition ensures proper amino acid translatable sequences may be investigated separately. Totals in

Table 2 show removal of suppressor and unassignable genes has minimal impact: uniqueness percentage declines from 63.6% to 63.1% because those sequences removed from the tally are almost always unique relative to each other.

Table 2 also contains the number of isoacceptors for each organism under condition (ii). These forty creatures possess numbers of isoacceptors from 46 in Mlu to 60 in Vpa. Bta has next to most isoacceptors at 54, revealing Vpa as an outsider in this regard, a status which will prove significant. Using condition (ii) data, normalized uniqueness percentages range from 42.1% for Mdo to 85.4% for Vpa. In addition to Mdo, Sha (42.9%) and Dor (47.6%) are on the conservative side of 50%. Vpa is not as much of an outlier in isodecoders compared to isoacceptors; Ttr encodes 80.7% uniqueness, and there are six animals above 70%.

Although informative,

Table 2 does not speak to the main issue at hand, which is proving a lack of degeneracy among isoacceptors.

Table 3 accomplishes this task by expressing uniqueness percentages as a function of anticodon triplet. It shows sixteen are encoded by relatively few strings: one for tRNA

Leu(GAG) in Laf up to sixty-five for tRNA

Sec(UCA) present in every animal but Mlu. Their unique-to-total sequence percentages equal 81−100%. Suppressor sequences—twenty-four tRNA

sup(CUA), eighty-nine tRNA

sup(UCA), forty-one tRNA

sup(UUA)—present uniqueness levels of 100%, 99%, 100%, respectively. Isoacceptor strings register uniqueness percentages from tRNA

Leu(UAG) (97.5%) to tRNA

His(GUG) (24.8%) based on 147−1673 sequences.

For any given amino acid—whether associated with 2-box, 3-box, 4-box, or 6-box isoacceptor—percentages are not the same except for lysine-affiliated tRNA, where tRNA

Lys(CUU) equals 63.1%, while tRNA

Lys(UUU) comes in at 63.0%. Alanine is fairly close at 82.0%, 83.3%, 100%, 80.9% for anticodon triplets AGC, CGC, GGC, UGC, respectively. Other 4-box amino acids are not a match for each other; for example, valine has 61.3%, 55.6%, 91.7%, 86.1% for anticodons AAC, CAC, GAC, UAC, respectively. Arginine, leucine, serine 6-box isoacceptors are unalike whether structured as 6-box or 2-box plus 4-box units; they appear more like valine than like alanine. Aside from lysine, the 2-box groupings are grossly different, with glutamic acid illustrative: tRNA

Glu(CUC) is 42.3% and tRNA

Glu(UUC) is 71.5%.

Table S4 unites

Table 2 and

Table 3. Demonstrably large variances per isoacceptor constitute unimpeachable evidence for tRNA inequivalence. Given a 1:1 correspondence with mRNA codons, a lack of redundancy among the latter is a necessary conclusion.

A comparison of archaeal to eukaryl tRNA uniqueness percentage per isoacceptor indicates six matches out of sixty-three possible pairs: standard sixty-one for twenty amino acids plus selenocysteine plus initiator methionine distinct from elongator methionine. Matches are arbitrarily defined as ±5% for each isoacceptor pair. Matched (Archaea %, Eukarya %) are: tRNAAsn(GUU) (46.9, 45.6); tRNAAsp(GUC) (39.6, 40.3); tRNACys(GCA) (55.2, 54.0); tRNAPro(UGG) (53.5, 51.0); tRNASer(GCU) (63.2, 59.6); tRNAVal(CAC) (58.1, 55.6). Only for aspartic acid are these mammals less conservative than relatively simple unicellular prokaryotes, with the remaining five isoacceptor pairings contrary to the overall domain relationship under condition (ii) of 52.3% vs. 63.1%. As a consequence of inequality between isoacceptors as well as among isodecoders, they might not translate the same amino acid. Both assertions are addressed in the Discussion section.

Table S5 offers a compilation of unique sequences for every animal sorted by species, anticodon triplet, associated length. Aside from a reference for research, it permits additional string features related to

skewness and

translational ambiguity found for Archaea to have demonstrated similar applicability in mammals. Think of each 1D tRNA sequence as a barcode not only distinguishing apples from oranges via isoacceptors, but also segregating fuji apples from gala apples by isodecoders. In this metaphor, total copy numbers equate to ratios for each type of apple. When arranged linearly left to right (5’ → 3’), the amino acid attachment point is on the extreme right. Stacking same-length sequences means anticodon triplets sometimes fail to possess perfect vertical alignment. Instead, inserted nucleotides left of the triplet induce

rightward skew; inserted nucleotides to the right cause

leftward skew; deleted nucleotides left of the triplet induce

leftward skew; deleted nucleotides to the right cause

rightward skew. As shown in

Table S5, skewness is rare, occurring mostly when there exists distinct 5’- and/or 3’ -terminal nucleotide triplets within isodecoders. Bta provides examples of skewness.

Ala (AGC) 72 nt

GGCGGUAUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCACAUGCUUAGCAUGCAUGAGACCCUGGGUUCAAUCCCCAGUACUGCCA

GGGGAUGUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCAUGCUUAGCAUGCAUGAGGUCCCGGGUUCGAUCCCCAGCAUCUCCA

GGGGGUAUAGCUCAGUGGCAGAGCACAUGCUUAGCAUGCACGAGACCCUGGGUUCAAUCCCCAGUAUCUCCA

GGGGGUAUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCAUGCUUAGCAUGCAUGAGGCCCUGGGUUCAAUCCCCAGUACCUCCA

GGGGGUAUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGUGCGUGCUUAGCAUGUAUGAGGUCCUGAGUUCAAUCCCCAGUACCUCCA

GGGGGUGUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCGUGCUUAGCAUGCACGAGGCCCCGGGUUCAAUCCCCGGCACCUCCA

GGGGGUGUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCGUGCUUAGCAUGCACGAGGCCCUGGGUUCAAUCCCCAGCACCUCCA

GGGGGUGUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGCGCGUGCUUAGCAUGUACGAGGUCCCGGGUUCAAUCCCCGGCACCUCCA

GGGGGUGUAGCUCAGUGGUAGAGUGUAUGCUUAGCAUGCACGAGGUGCCAGGUUCAAAUCCUGGCACUUCCA

UCCCUGGCAGUCCAGUGGUUAGGACUUGGCACCAGCACUGCCAGGGCCCAGGUUCGAUCCUUGGUUGGGGAA

Ala (AGC) 73 nt

GGGGAAUUAGCUCAAAUGGUAGAGCGCUCGCUUAGCAUGUGAGAGGUAGCGGGAUCGAUGCCCGCAUUCUCCA

GGGGAAUUAGCUCAAGUGGUAGAGCGCUCGCUUAGCAUGUGAGAGGUAGUGGGAUCGAUGCCCACAUUCUCCA

GGGGAAUUAGCUCAAGUGGUAGAGCGCUCGCUUAGCAUGUGAGAGGUAGUGGGAUCGAUGCCCGCAUUCUCCA

GGGGAAUUAGCUCAAGUGGUAGAGCGCUUGCUUAGCAUGUGAGAGGUAGUGGGAUCGAUGCCCACAUUCUCCA

GGGGGAUUAGCUCAAAUGGUAGAGCGCUCGCUUAGCAUGCGAGAGGUAGCGGGAUCGAUGCCCGCAUCCUCCA

GGGGGAUUAGCUCAAAUGGUAGAGCGCUCGCUUAGCAUGCGAGAGGUAGUGGGAUCGAUGCCCAUAUCCUCCA

GGGGGUGUAGCUCA GUGGUAGAGCGCGUGCUUAGCAUGCACGAGGCCCCGGGUUUCAAUCCCCGGCACCUCCA

Table S5 also provides a visual demonstration of anticodon triplet ambiguity by highlighting it in

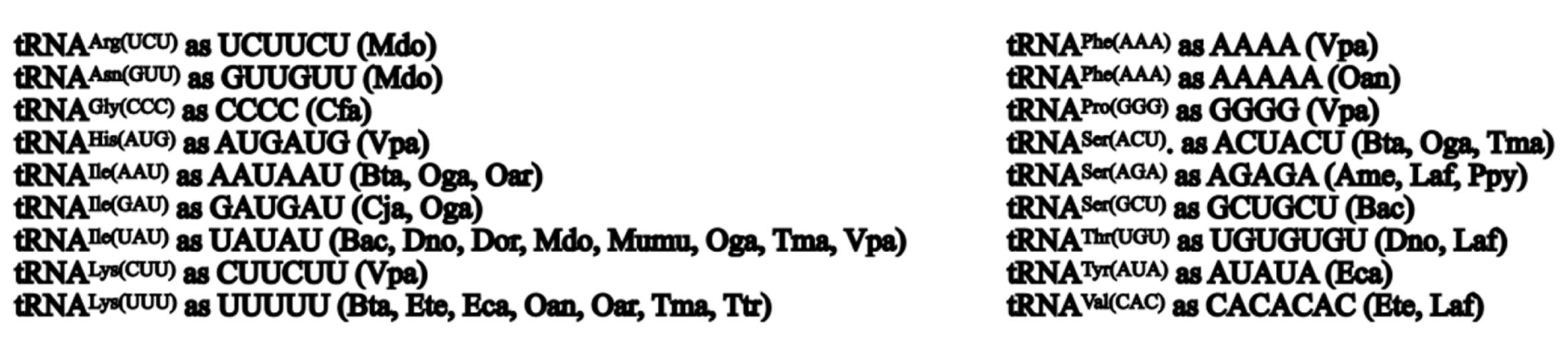

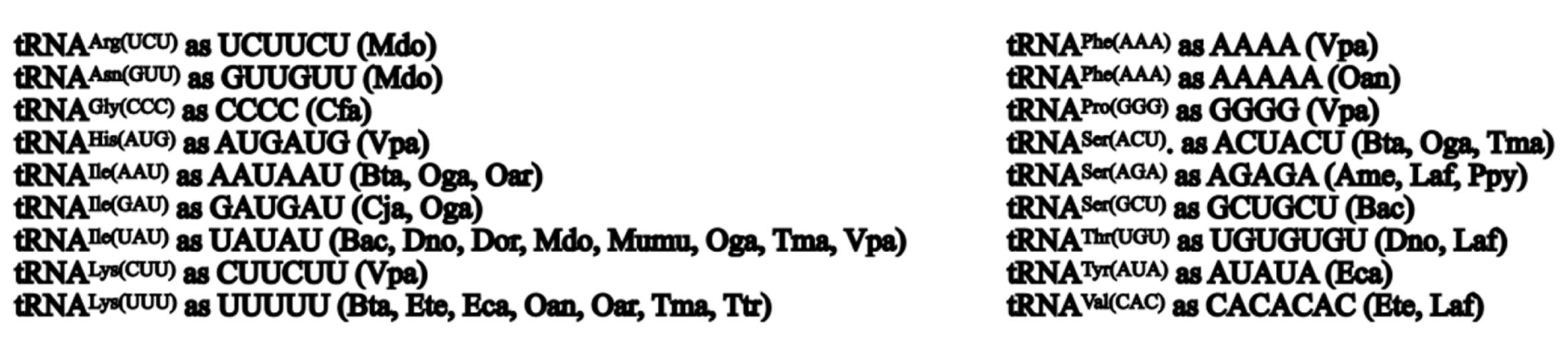

bold red font. Ambiguity results if adjacent nucleotides extend the triplet region, and the pattern occurs in three formats: (i) letter replication beyond XXX; (ii) palindromic repeats XYXYX; (iii) triplet duplication XYXXYX, XYYXYY, XXYXXY, XYZXYZ. Four ambiguous anticodons appear with frequencies above 50%: tRNA

Arg(CCU) as CCUCCU (63.5%); tRNA

Glu(CUC) as CUCUC (86.8%); tRNA

Lys(UUU) as UUUU (97.4%); tRNA

Val(CAC) as CACAC (73.3%). Skewness and ambiguity might appear together, emphasizing sequence individuality: CUCUC extends in the 5’ direction, while CACAC extends towards a 3’ terminus. In addition to these four, ambiguity occurs rarely, and usually as single events within an animal genome:

In sum, only tRNA connected to alanine, aspartic acid, cysteine, glutamine, leucine, methionine, selenocysteine, tryptophan are free of translational ambiguity. Apparent symmetry leading to ambiguity may be broken by nucleotide modification occurring post-transcriptionally. These alterations are not considered due to an insufficiency of knowledge for these species. Although vast amounts of research on the topic exists, mammal-relevant work focuses on eukaryotic model organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Berg and Brandl 2021; Dannfald et al. 2021). As stated in the Introduction, it is not presumed changes apply automatically to other Eukarya after one billion years divergence time. Data collected on nucleotide modifications might be significant in the present context; that it must be, without more general proof of applicability in mammals, is a viewpoint subject to legitimate criticism.

Upon collecting unique sequences in

Table S5, an unmistakable pattern pertaining to initial (position 1) nucleotide identity and isoacceptor, independent of length, was observed:

Adenosine for tRNAiMet(CAU) and tRNALeu(UAA)

Cytidine for tRNATyr(AUA) and tRNATyr(GUA)

Uridine for tRNAAsp(AUC), tRNAAsp(GUC), tRNAGlu(CUC), tRNAGlu(UUC)

Guanosine for all other tRNA (fifty-five, counting initiator and elongator methionines separately plus selenocysteine)

Theoretically, first position mutations are conceivable for isodecoders from each isoacceptor in every mammal. In practice, no acceptable mutations were encoded for tRNA

iMet(CAU); if they occurred in the past, they were quickly excised from genomes, consistent with its special role in translation. Although there seems no easily discernible justification for an eight plus fifty-five isoacceptor division, eighteen animals followed the pattern with six or fewer total isodecoder deviations.

Table S6 presents a matrix of initial position codon mutation numbers with respect to each amino acid. Of 12,283 unique sequences for amino acid-related tRNA, 1236 violations (10%) were discovered. This is not a product of neutral drift because particular tRNA are especially susceptible to alteration at position 1, with sequences for alanine, arginine, glutamic acid, glycine, lysine, tryptophan affected most (69% of pattern deviations), whereas asparagine, histidine, isoleucine, methionine, phenylalanine, proline, selenocysteine, threonine, tyrosine are impacted least (7.5%).

Animals most susceptible to pattern violation are Bac, Bta, Oar, Ttr, a group itself connected. Bac and Ttr from order Cetacea diverged 34 million years ago; Bta and Oar from order Artiodactyla separated 24.6 mya; Bac/Ttr had their last common ancestor with Bta/Oar 58 mya (

Table S1). These four species comprise the closest land-based and sea-based living creatures (Foote

et al. 2015). A review of sequences (

Table S5) in context with the matrix (

Table S6) indicates this group is responsible for establishing uridine as rival to guanosine starting nucleotide for twenty-six isoacceptors (fourteen amino acids). Uridine is normally preferred for only acidic amino acids, but these four species altered (infected?) isoacceptors for every amino acid except histidine, leucine, proline, selenocysteine, tyrosine. The mutated strings possess starting 5’ and ending 3’ triplets identifiable as carryovers from aspartic and glutamic acid sequences. In other words, acidic amino acid tRNA are especially prone to undergo mutation at the anticodon triplet, illustrated by conversions tRNA

Asp(AUC) → tRNA

Ala(AGC); tRNA

Asp(GUC) → tRNA

Asn(GUU); tRNA

Glu(CUC) → tRNA

Lys(CUU); tRNA

Glu(UUC) → tRNA

Gln(UUG).

In addition to encoded tRNA strings whose anticodons were deemed unassignable (145 total, 142 unique) by scientists performing the sequencing analyses, a small number definitively assigned to specific isoacceptors still had nucleobases whose identity was uncertain. It is now possible to suggest resolution of these instances with high probability based on correlation with other sequences in those animals.

Table S7 lists recommended corrections along with justification. Certainty is impossible, unless sequencings are independently repeated, since nucleobase alteration not conforming to precedent is an option. There is, however, one exception to impossibility of certainty: in Ggo, there exists an unusual 98 nt tRNA

Pro(AGG) encoded sequence with a 20 nt section of unknown bases:

GGCUCGUUGGUCUAGGGGUAUGNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNGGUAUGAUUCUCGCUUAGGGUGCGAGAGGUCCCGGGUUCAAAUCCCGGACGAGCCC

Regardless of identities for those missing twenty bases, removal leaves a 78 nt string possessing a six nt overlap (

underlined bases) producing a mature 72 nt tRNA

Pro(AGG) precisely matching nucleotide-for-nucleotide a sequence existing in this animal’s genome (

Table S5). The remaining six examples from

Table S7 contain consecutive nucleobase strings of 1−4 unknowns (i.e.,

N →

NNNN).

Having determined unique tRNA sequences within each genome, they were examined to evaluate whether identical patterns existed excluding the anticodon triplet, which had to be distinct from each other since perfect matches throughout the entire length had been removed.

Table S8 provides a complete list of all successful pairings and

Table S9 arranges that information by the number of mammals encoding each internal sequence match. From the data it becomes obvious specific isoacceptors more frequently possess a match inside the genome primarily associated with alanine, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, leucine, proline, serine, valine, though not all appear in every genome. Aspartic acid, histidine, isoleucine, lysine, phenylalanine each merited inclusion once; arginine and tryptophan twice; threonine in four genomes; cysteine in five. Asparagine, methionine, selenocysteine, tyrosine are absent. Of more significance than recitation of amino acids are the sets of anticodon triplets grouped. An in-depth analysis of meaning is forthcoming in the Discussion, but a preview has been mentioned with respect to uridine mutations for position 1.

This internal matching exercise also permitted an analysis of the tRNA in each genome labeled as

Undet (

NNN) by initial researchers (according to GtRNAdb). From

Table S4, five species have more than two unassignable tRNA: Oar (four), Bta (eleven), Bac (seventeen), Ttr (twenty-one), Vpa (seventy-six). The first four have been acknowledged to be phylogenetically related, and outlier status exhibited by Vpa has been noted in a different context. Executing a spreadsheet

sort command allowed nearest neighbor strings to be determined. Plausible assignment of anticodon triplet could often be made, with the results in

Table S10 segregated as

probable (109),

possible (sixteen),

still unassignable (seventeen). Strings called

probable differed from a neighbor string used as reference by 0−9 nucleotides as an arbitrary cutoff; those denoted

possible deviated from their reference by 10−14 nucleotides.

Assigned tRNA contained either an exact match to the reference anticodon or a mutation in one base. Strings still regarded as unassignable either had no close matches to any nearest neighbor, or the best alignment instituted a gap in the anticodon triplet preventing evaluation.

Table S10 is organized by mammal, anticodon assignment, tRNA

Undet(NNN) plus nearest neighbor used as the basis for assignment. With its relatively enormous number of undetermined tRNA, Vpa commands special attention. Of its seventy-six unknowns, the evaluation process led to sixty-four in the probable group along with three possibles and nine still uncertain. For a species with 833 unique tRNA

Ala((AGC), 63% of tRNA

Undet(NNN) used one of these as its reference string.

The next matching activity involving unique tRNA sequences compared them in all forty animals. Extensive usage of cell background colors facilitated distinguishing species. Unique sequences, omitting suppressor and original undeterminable strings, were subjected to the spreadsheet

sort command. Again, 100% nucleotide-for-nucleotide pairwise match was the only acceptable criterion. Successful matches per isoacceptor with associated length were tabulated; the minimum number of inclusive genomes was two and the maximum forty.

Table S11 reports 631 amino acid-translatable tRNA sequences were found. As shown in

Table 2 arranged by animal, 5617 matched out of 12,283 unique sequences (45.7%), with a larger percentage of matches incurred by smaller genomes. In a separate test, two tRNA

sup(UCA) and one tRNA

Undet(NNN) aligned perfectly, deriving from cetaceans Bac and Ttr in all three cases (also shown in

Table S11).

If the classic dogma held true, every isoacceptor would have at least one isodecoder matched in all forty species, corresponding to unmodified versions of twenty classical amino acids; it is not expected, nor does it occur, that every animal encodes tRNA

Sec(UCA). Just twenty-nine sequences appear with 100% nucleotide match in all forty species (

Table 5 and

Table S11); 42.9% connected two animals, with every value from 2−40 genomes represented (

Table 5), Of crucial importance, this set of twenty-nine isodecoders covers at least one isoacceptor for each canonical amino acid, with two for arginine, glycine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, proline, serine, tryptophan, valine. The tryptophan sequences reference single isoacceptor tRNA

Trp(CCA), and there is a single nucleotide difference between them. Methionine’s match exists only for the initiator version; the highest interspecies acceptance for elongator methionine sequences is thirty-eight species (absent in Mdo, Sha). The import cannot be overstated: sixty-one isoacceptors do not find exact sequence matches in every mammal, substantiating the fact that 1:1 codon/anticodon complexes are not degenerate.

The ten tRNA sequences present in thirty-nine animals were studied to assess how deviant, based upon number of nucleobase differences, was the genome of the absent species. Results are detailed in

Table S12. They involve tRNA sequences related to two alanine, two arginine, one glycine, one leucine, one lysine, one proline, one serine, one threonine. More than three mismatched nucleotides was arbitrarily defined as a

not close match; two alanine (Sar, Vpa), glycine (Oan), serine (Ocu), threonine (Vpa) strings satisfied this negative condition, whereas the lysine sequence (Eeu) was borderline with three variants. Both tRNA

Arg(UCU) (Bac, Dno) altered a single nucleobase generated by two nearest neighbors each, and this was also found for two sequences from Ame for tRNA

Pro(UGG) plus a single neighbor from Mlu for tRNA

Leu(CAG). The arginine pair reference the same isoacceptor, and tRNA

Leu(CAG) was already covered in the collection of twenty-nine sequences. If the four amino acid associated strings are accepted into the consensus set, addition of two expands those covered in all forty mammals to thirty isoacceptors, which is barely halfway to sixty-one isoacceptors in the Standard Genetic Code.

Table 6 employs a standardized format for those twenty-nine strings in order to evaluate which, if any, nucleobases are invariant. This

three-point scheme uniformly aligns 5’ terminus + anticodon triplet + 3’ terminus, inserting gap spaces where needed to compensate for unequal lengths of the natural strings (71−83 nt). By this technique, anticodon triplets are at positions 35−37, and no nucleotide modifications are entertained in consideration of conservation; 2D cloverleaf and nucleotide numbering system (Sprinzl

et al. 1998) are inconsequential. Nine positions (

bold font) express strict conservation: U

8, G

10, A

14, G

18, G

63, U

65, C

66, A

68, C

71. These sequences supply a variety of lengths, 5’ beginning and 3’ ending nucleotide triplets:

lengths → 71 nt (1×), 72 nt (12×), 73 nt (8×), 74 nt (4×), 82 nt (3×), 83 nt (1×)

5’ terminus → AGC (1×), CCU (1×), GAC (4×), GCA (1×), GCC (4×), GCG (1×), GCU (1×), GGC (4×), GGG (3×), GGU (2×), GUA (1×), GUC (2×), GUU (2×), UCC (2×)

3’ terminus → ACA (3×), ACG (2×), CCA (3×), CCC (2×), CCU (3×), CUA (1×), GAA (1×), GAG (1×), GCA (5×), GCG (2×), GGA (1×), UCA (2×), UCG (3×)

Table 7 permits tracing a relative phylogenetic relationship among these animals by determining the number of matches against a species chosen as arbitrary standard. Since we are homocentric creatures by nature, it is convenient to use Hsa as reference. Ideally, larger numbers of common isodecoder strings should imply closer phylogenetic relationships in a single ordering. Hsa has a representative in 164 of 631 matches (26.0%). In common with those 164 tRNA are 142 held by Ptr, followed by 128 for Ggo, 121 for Ppy, 117 for Nle and so on, with Oan last at sixty-one sequences. Comparing this order with

TimeTree divergence times gives a near-perfect fit: less time divergence equals more matches. This is wholly to-be-expected, for it is the root rationale for constructing phylogenetic relationships in the first place.

These are raw data results, and it is

prima facie reasonable to predict larger numbers of encoded tRNA would lead to a greater number commonly held because chances of agreement likely increase with opportunities. However, a string length of 73 nt generates 4

73 ≈ 8.9×10

43 permutations; leucine and serine tRNA of 82 nt produce 4

82 ≈ 2.3×10

49 distinct strings. Genome size differences are of order 130−1436 isodecoders, with reference Hsa having 254 (

Table 2). On the scale of possibles, genome size variance for unique tRNA are insignificant in terms of increasing the likelihood of a perfect match.

Knowing there are 631 encoded sequences among 2−40 mammalian species producing perfect matches enables comparison of this collection with unique tRNA strings from other lifeforms in order to determine whether model organisms serve as proper representatives for all biological constructs related to translational processes. It is informative to proceed according to TimeTree divergence times:

Fifty-two unique tRNA from

Escherichia coli (strain K12) failed to find 100% matches, focusing specifically on respective tRNA

iMet(CAU) sequences (

Table S13a).

186 Archaea containing 4608 unique tRNA with 12,283 unique mammalian tRNA, including those 631 interspecies-matched sequences, culminated in finding not a single perfect agreement, in particular for respective tRNA

iMet(CAU) sequences (

Table S13a). Such failure implies either: (i) no horizontal gene transfer occurs; (ii) occurs, but transferred strings are later altered in one or more nucleobase positions once internalized by an organism; (iii) an insufficient number of eukaryl species were examined. This test does not dismiss horizontal gene transfer as a possibility between domains; it only draws a tentative inference with respect to this process occurring across sets of tRNA genes.

Arabidopsis thaliana,

Oryza sativa,

Zea mays with 171, 193, 304 unique tRNA, respectively, failed to find 100% matches, in particular for respective tRNA

iMet(CAU) sequences (

Table S13a).

Fifty-five unique tRNA from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (strain S288c) failed to find 100% matches, in particular for respective tRNA

iMet(CAU) sequences (

Table S13a).

Caenorhabditis elegans and

Drosophila melanogaster encoding 152 and eighty-four unique tRNA, respectively, produced four matches: tRNA

Gln(CUG), tRNA

Gln(UUG), tRNA

Lys(CUU), tRNA

Pro(CGG), all from

Drosophila melanogaster. A focus on respective tRNA

iMet(CAU) sequences failed to find matches to the consensus mammalian version (

Tables S13a and S13b). There were fourteen cases where variations appeared in no more than three nucleobases, with just two containing

Caenorhabditis elegans strings. In no case did both invertebrates match a single mammalian tRNA (

Table S13b). Among four perfect alignments, the anticodon triplets are related by single base mutation: CUG → UUG; CUG → CUU; CUG → CGG. To be clear, these four are not identical to each other throughout their length; they are separately the same as representative mammalian tRNA. The mutation pattern is reminiscent of radioactive isotopic decay whereby element A is converted to element B by gain or loss of a helium nucleus (α process) or to element C by gain or loss of an electron (β process).

Alligator mississippiensis and

Gallus gallus with 391 and 158 unique tRNA, respectively, displayed numerous perfect pairings related to all isoacceptors. Twenty-five of the twenty-nine strings encoded by all mammals were also found in the two nonmammalian vertebrates, as well as nine of those ten strings contained in all mammals but one (i.e., sequences with thirty-nine-member genomes). Among those twenty-five was the consensus tRNA

iMet(CAU) sequence (

Table S13c).

Discussion

Genetics theorists directly confront Sophie’s Choice on a regular basis: a cherished idea must die. Perhaps genomes from evolutionarily divergent species should be radically different due to: (i) natural selection for environmental adaptation; (ii) unpredictable random mutation; (iii) genetic drift leading to an accumulation of inaccuracies in transcription and/or translation occurring over time, Contrarily, one may expect genes to demonstrate high degrees of sequence similarity for analogous function despite influential factors pushing for change. Consequently, geneticists might be surprised by gene identicality, if adhering to the first view, or by variance, if advocates of the second perspective. They cannot have it both ways at the same time for a given thematic issue. Call it the central conflict in evolutionary theory: taxonomy is predicated on a supposition that kingdoms, phyla, families, species normatively establish separate pursuits in life for life; yet, despite aspirations towards individuality, encountering issues concerning predators and prey, sexual reproduction, attracting or avoiding effects of natural phenomena (gravity, electromagnetic radiation, weather) means they sometimes converge in discovering ways to survive and prosper.

Like proteins, nucleotide sequences display degrees of homology over their length. Unlike them—where components can be same (valine vs. valine), similar (leucine vs. valine), or different (arginine vs. valine)—nucleotide comparisons in two molecules face a binary option; even if modified, they are either identical or not. The notion of similar nucleotides is a fallacy, although some perceive A/G purines similar and C/U pyrimidines likewise. Why does similarity not apply? The pairs engage in different numbers and strengths of hydrogen bonds during complementary base pairing, affecting the energetics of interaction in nonequivalent ways: three hydrogen bonds in GC equal to 14.3 Kcal/mol, as opposed to two hydrogen bonds in AU worth 10.6 Kcal/mol (Halder et al. 2019).

All pieces of data reported in Results collectively lead to three theses about the roles played by tRNA in mammalian, and probably vertebral lifeforms in general, though only two are proposed as novel: (i) isodecoders provide a record of benign mutations; (ii) beyond transporting amino acids to ribosomes, tRNA participate in modifying them before and during translation; (iii) secondary structure development in growing proteins depends on tRNA sequences.

When tRNA from forty mammals display patterns of both identicality and uniqueness, it must be in consequence of different aspects pertaining to structure and function. Structural parameters regarding length, sequence, skewness, anticodon ambiguity all express unrelenting diversity. Nucleotide differences between isodecoders represent mutation history almost by definition, since hazardous or lethal alterations would probably have been exorcised from genomes if longevity or survival were at stake. Evidence for a historical interpretation should be, at minimum, a finding that phylogenetically proximate species undergo similar changes.

Table 7 confirms this indirectly by verifying a correlation between animal divergence time and incidence of string identity relative to humans. Contrarily, if evolutionarily separated creatures jointly develop mutations absent in more closely-related organisms, then other reasons for their presence must be discovered while still respecting a doctrine of historical record: do they serve cognizable novel purposes?

Both sequence identicality and deviation require justification. The law of large numbers enters in force, and probability statistics work in both directions. A 4-base code of 73 nt generates 473 ≈ 8.9×1043 possible sequences. If two strings, each 73 nt, are perfect matches across their length, the odds of this happening are one in 42×73 ≈ 8.0×1087 or, in general, one in 4MN for M creatures possessing N identical nucleotides. Therefore, when twenty-nine tRNA strings display nucleotide-for-nucleotide matches across forty species diverging 6−180 mya, it can only be attributed to sharing the same function each time; the odds against coincidence are truly astronomical, although an exact accounting would necessitate factoring in different lengths among these twenty-nine.

Sequence deviation is far more probable because the odds of a single base change is one in three rather than one in four for complete randomness. If, in a reference mammal, nucleotide A is replaced by C in mammals 2 and 3, then it is chosen from set C/G/U in each, so the odds are one in nine, whereas starting from scratch means selection from set A/C/G/U. For N identical variations between two species from any reference sequence chosen from among 8.9×1043 options, the probability is one in 32N. and for M creatures the chances are one in 3MN. Longer leucine and serine affiliated tRNA make the odds much worse since baseline numbers of permutations rise exponentially. This is another strong argument against coincidence. The conclusion must be similarity in sequence—defined by number of nucleobase changes between any pair—need not, at a degree of variance possibly as small as a single alteration, result in identical purposes. On the other hand, large amounts of variation, however large is quantified, may yield the same outcome or exhibit differential effects. Probability alone is inadequate for assessment; as in real estate, location (of changes) means everything with respect to value.

A second justification for matching sequences altered in exactly the same way from a reference is convergent evolution. As a philosophical principle of adaptation, its invocation automatically concedes a purpose for tRNA sequence variation above and beyond historical record or sheer coincidence. The only battle remaining is to assign the correct purpose(s). Referral to

Table S11 is again made: twenty-nine of 631 tRNA held in common by forty mammals, with 602 sequences matched by two to thirty-nine animals. That represents a lot of convergent evolution definitely against the odds. Some of those 602 differ from the twenty-nine by a single nucleotide. For example, tRNA

Leu(CAG), 83 nt long, where the upper is found in all mammals investigated, while the lower is present in all but Mlu. From the general formula, odds (M = 39, N = 1) for deviation from the top tRNA is one in 3

39 ≈ one in 4.1×10

18.

GUCAGGAUGGCCGAGCGGUCUAAGGCGCUGCGUUCAGGUCGCAGUCUCCCCUGGAGGCGUGGGUUCGAAUCCCACUCCUGACA

GUCAGGAUGGCCGAGCGGUCUAAGGCGCUGCGUUCAGGUCGCAGUCUCCCCUGGAGGCGUGGGUUCGAAUCCCACUUCUGACA

Identicality in sequence causing identicality in function is transparently logical, providing a firm ground for rational thought. Quasi-identicality throughout a string length implies a concomitant range of functional activity from absolutely identical to relatively similar. If divergence time between species is sufficiently narrow, the continuum scale of in vivo action tends more towards clone-like outcomes. When nucleotide sequences are dissimilar enough, they, nonetheless, could evoke similar biochemical endpoints if organisms are proximate physiologically and inhabit analogous geographical niches; should conditional criteria be unmet, the balance tips towards otherness in action. Large-scale deviance in tRNA leading to altered function is the logical converse of the first postulate, but causally neither necessary nor sufficient for guaranteeing a result. It remains to answer a crucial question: how much difference is enough to make a difference?

Returning to tRNALeu(CAG), and bearing in mind the hypothesized additional functions for tRNA, is it conceivable the single nucleobase change is assignable to participation in leucine modification in the intervening period between transcription and translation, or to involvement in co-translational folding of the peptide chain? Absolutely. C/U structural variance could lead to different points of contact between tRNA and rRNA, or between tRNA and ribosomal proteins, because C4 in cytidine has an NH2 attached able to act as both hydrogen bond donor or acceptor, whereas uridine C4 is engaged in a double bond to O capable of hydrogen bond acceptor status only. In addition, the C−N single bond (1.37Å) is longer than a C=O double bond (1.27Å), so it extends farther into the ribosomal space (Heyrovska 2008). Nothing here constitutes proof; it is all conjecture, but plausible, deserving of confirmation or rejection.

The influence of sequence is paramount for any discussion of tRNA function beyond its known role as amino acid conveyor to ribosomes. The other structural parameters (length, skewness, anticodon ambiguity) are relevant to disclosing full tRNA participation in translation.

Table S3 covering preferred length distributions reveals predominant tRNA lengths are 72−73 nt for isoacceptors besides those leucine or serine related (82 nt). Exceptions include: 71 nt (tRNA

Gly(CCC), tRNA

Gly(GCC)); 74 nt (tRNA

Asn(GUU), tRNA

Ile(AAU), tRNA

Ile(UAU), tRNA

Thr(AGU)); 83 nt (tRNA

Leu(CAG), tRNA

Leu(UAA)); 84 nt (tRNA

Leu(CAA)); 87 nt (tRNA

Sec(UCA)). Long strings beyond 87 nt are accommodated by flexible variable arms; lengths less than 71 nt present challenges to cloverleaf construction (Sprinzl

et al. 1998).

Sequences beyond those 71−87 nt limits should be viable unless proven otherwise. Hamashima et al. speculated that atypically long tRNA sequences housed in that variable arm, excluding leucine and serine isoacceptors, may not be aminoacylated at all, but serve other functional roles in all branches of Eukarya (Hamashima et al. 2015). This hypothesis begs for experimental approval or disapproval. An exploration of novel variable armed tRNA from bacterial genomes show Escherichia coli aminoacylation activity in some strings, but these authors conceded other sequences could possess otherwise unspecified nonaminoacylation functions (Mukai et al. 2017).

In this set of mammalian tRNA, forty-three sequences are shorter than 71 nt and six longer than 87 nt. Regardless of whether length distortions from that preferred for a given isoacceptor are less than, within, or beyond this length range, either they are of in vivo significance, meaning affect functionality, or represent irrelevant extravagances. Using resource material unnecessarily requires energy probably better employed for other situations, so the second choice is a priori less plausible. Lynch & Marinov engaged in an exhaustive analysis of energetic costs for Bacteria and Eukarya in cells undergoing gene replication, transcription, translation (Lynch and Marinov 2015). For tRNA, only the first two processes are pertinent. Using their calculations: (i) during M phase of a cell cycle, growth and maintenance energetic costs for a cell once formed are Escherichia coli << Saccharomyces cerevisiae << Mus musculus; (ii) during S phase of a cell cycle, transcription of mRNA after production engages energetic costs such that Escherichia coli < Saccharomyces cerevisiae < Arabidopsis thaliana; (iii) in absolute values, transcription costs exceed replication costs by at least one order of magnitude.

It is reasonable to accept energetic costs of mRNA would be sufficiently close to those for tRNA (nucleobase synthesis, processing into mature form, modifications as necessary) to render them roughly interchangeable, and those for Arabidopsis thaliana to adequately serve as proxy for Mus musculus in that both represent structurally complex Eukarya. Consequently, transcription of nonpreferred tRNA lengths for no legitimate purpose is inefficient. It is more rational to believe they topologically alter relationships among nucleotides, affecting folding ability into the conventional 3D shape. Spatial adjustments may also change potential contact points with other translation active biomaterials, affecting properties such as thermodynamic binding stability, kinetic translation rate, decomposition frequency.

Using a baseline of 71 nt established by glycine-related isoacceptors, deletions and insertions can be obtained from: (i) isodecoders by removal or addition of at least one nucleotide; (ii) other isoacceptors by nucleotide polymorphism at the anticodon triplet plus removal or addition of one or more nucleotides; (iii) foreign sources through horizontal gene transfer (Keeling and Palmer 2008). They are illustrated, where underlining indicates nucleobase mutations, and compiled in

Table S14.

isodecoder test

GGGCCAGUGGCGCAA UGGAUAACGCGUCUGACUACGGAUCAGAAGAUUCUAGGUUCGACUCCUGGCUGGCUCG

GGGCCAGUGGCGCAAUGGAUAACGCGUUGAUAACGCGUCUGACUACGGAUCAGAAGAGUCUAGGUUCGACUCCUGGCUGGCUCG

Addition constitutes an 11-nucleotide repetition of UGGAUAACGCG. From

Tables S2 and S3, 73 nt is preferred in all forty mammals. It is conceivable this was an inadvertent sequencing or recording error by the original researchers. In the Results section, correction of a 98 nt tRNA

Pro(AGG) from Ggo was demonstrated to fall into this category. Using a cutoff of three or fewer base alterations from the reference sequence as distinguishing

probable from

possible,

Table S14 offers fifteen probable and four possible tRNA outside the 71−87 nt range as belonging to this category (not including two mentioned in the text).

isodecoder test

GGCCCCAUGGUGUAA U GGUU AGCACUCUGGACUUUGAAUC CAGCGAUC CGA GUUCAAA UC UCGG UGGGACCU

GCC UGG GUGGCUCAGUCGGUUGAGCG UCU GACUUUGGCUCAGGUCA CGAUCUCGCGGUCCGUGGGUUCGAGCCCCACGUCGGGCU

isoacceptor test

GCCUGGGUGGCUCAGUCGGUUGAGCGUCUGACUUUGGCUCAGGUCACGAUCUCGCGGUCCGUGGGUUCGAGCCCCACGUCGGGCU

GCCUGGGUGGCUCAGUCGGUUGAGCGUCUGACUUCAGCUCAGGUCACGAUCUCGCGGUCCGUGGGUUCGAGCCCCACGUCGGGCU

Isodecoders of preferred length 72 nt for tRNA

Gln(UUG) differ by many nucleobases even with gaps introduced in both sequences (one sample comparison shown), but an isoacceptor gives a perfect match. According to

Table S2, preferred length for tRNA

sup(UCA) is species-dependent, although 85 nt in Fca. As shown in

Table S14, three tRNA are assigned to this type, not counting that shown here.

isodecoder test

GGCUCUGUGGCGCAAUGGA UAGCGCAUUGGACUUCUAAUUCAAAGGUUGUGGGUUCGAGUCCCACCAGAGUCG

GUCUCUGUGGCGCAAUGGACGAGCGCGCUGGACUUCUAAU CCAGAGGUUCCGGGUUCGAGUCCCGGCAGAGAUG

isoacceptor test

GUCUCUGUGGCGCAAUGGACGAGCGCGCUGGACUUCUAAUCCAGAGGUUCCGGGUUCGAGUCCCGGCAGAGAUG

GUCUCUGUGGCGCAAUGGGUUAGCGCGUUCGGCUGUUAACUGAAAGGUUGGUGGUUCGAGCCCACCCAGGGACG

A gap space was added to maximize alignment in the isodecoder test because the preferred length for tRNA

Arg(UCU) is 73 nt. So many mutations were found in these comparison tests that the most likely source is external due to gene transfer. The feasibility of tRNA gene movement was discounted between Archaea and Mammals at the close of the Results section, leaving Bacteria or organelles (mitochondria) as suspects.

Table S14 indicates twenty-six strings could not be matched by any sequence encoded.

Anticodon ambiguity was described as an intrinsic feature of some isoacceptors signifying their nondegeneracy. Encoding frequency varies from always (UUUU) to usually (CCUCCU) to occasionally (UAUAU) to rarely (GGGG), and leads to two related phenomena: ribosomal pausing and frameshifting. Pausing occurs when translation momentarily halts while mRNA/tRNA strands struggle to gain the proper relationship ensuring correctly attached amino acid in the ribosomal A site is joined to the peptide present in the P site. Frameshifting is a consequence of incorrectly spaced complementary base pairing.

An anticodon ambiguity consecutively extended one nucleotide leading to NaNaNaNa results in a corresponding ± 1 frameshift depending on whether the extra identical residue is located towards the 5’ or 3’ end. If ambiguity is palindromic of form NaNbNaNbNa then a ± 2 frameshift eventuates. A repeat of type NaNbNcNaNbNc (or permutations involving six nucleobases) does not technically create frameshifts since it is a multiple of three. Instead, it forces an aminoacylated tRNA to adopt a conformation contrary to that produced when the correct triplet is aligned. The question becomes whether shifted nucleotide triplets can still establish appropriate interactions with rRNA nucleotides of the large and small subunits (Harish and Caetano-Anollés 2012) or with neighboring ribosomal proteins (Wilson and Doudna Cate 2012).

Cognizing connections between anticodon ambiguity and ribosomal pausing permits an alternate explanation for data accumulated by Charneski & Hurst. Translation rate along Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribosomes decreases if positively charged arginine, histidine, lysine are found in (near) the Peptide Exit Tunnel because of, they speculated, electrostatic attraction to negative charges on phosphates in rRNA. Acknowledging histidine displayed weaker effects than the other two, differences were ascribed to pKa at physiological pH (Carneski and Hurst 2013).

Arginine codon AGG complements tRNAArg(CCU) encoded as CCUCCU 63.5% of the time among forty mammals and also present in the yeast genome as a unique tRNA string in a single occurrence. Repetition makes it difficult for mRNA to establish a correct pairing properly oriented to ensure other nucleotide interactions, slowing down processing. Similarly, mRNA codon AAA for lysine is partnered with tRNALys(UUU) always encoded as UUUU or UUUUU among studied mammals and as UUUU in the fungus. Again, searching for the right nucleotide positions induces temporary ribosomal pausing. Finally, histidine’s reduced effect is explained by matching mRNA codon CAC with tRNAHis(GUG). The yeast and mammal strings are almost palindromic: GUUGUG rather than GUGUG; in consequence, there is some decline in translation speed, but only a fraction caused by ambiguous anticodons in arginine and lysine, as observed.

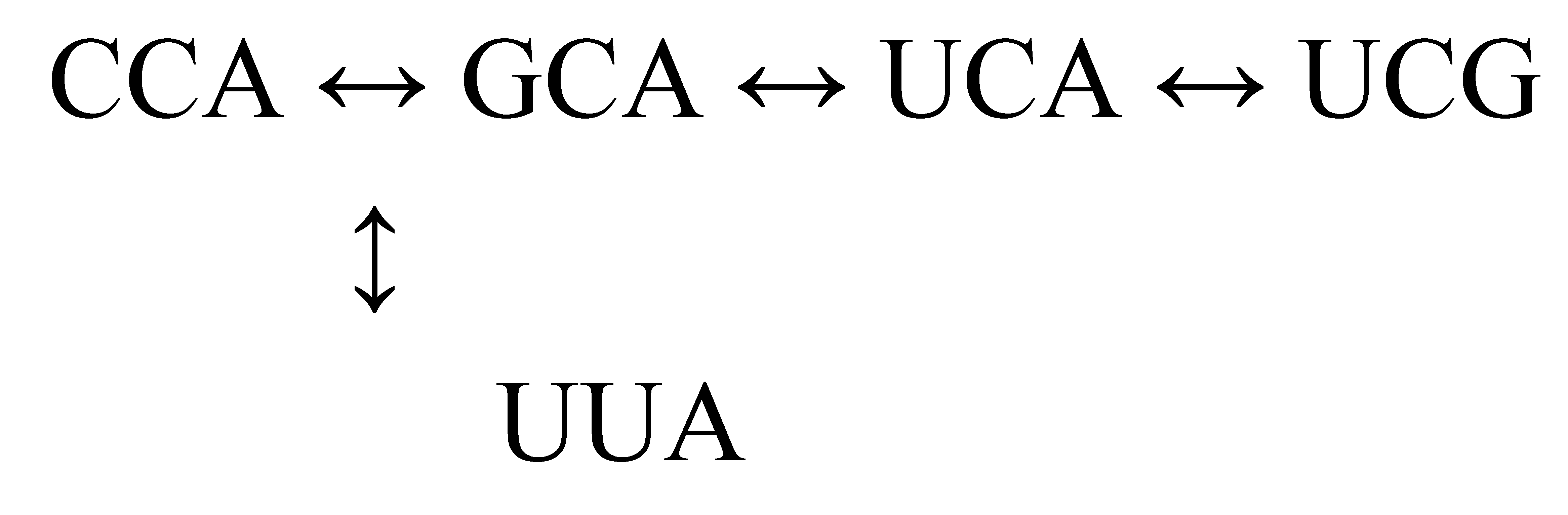

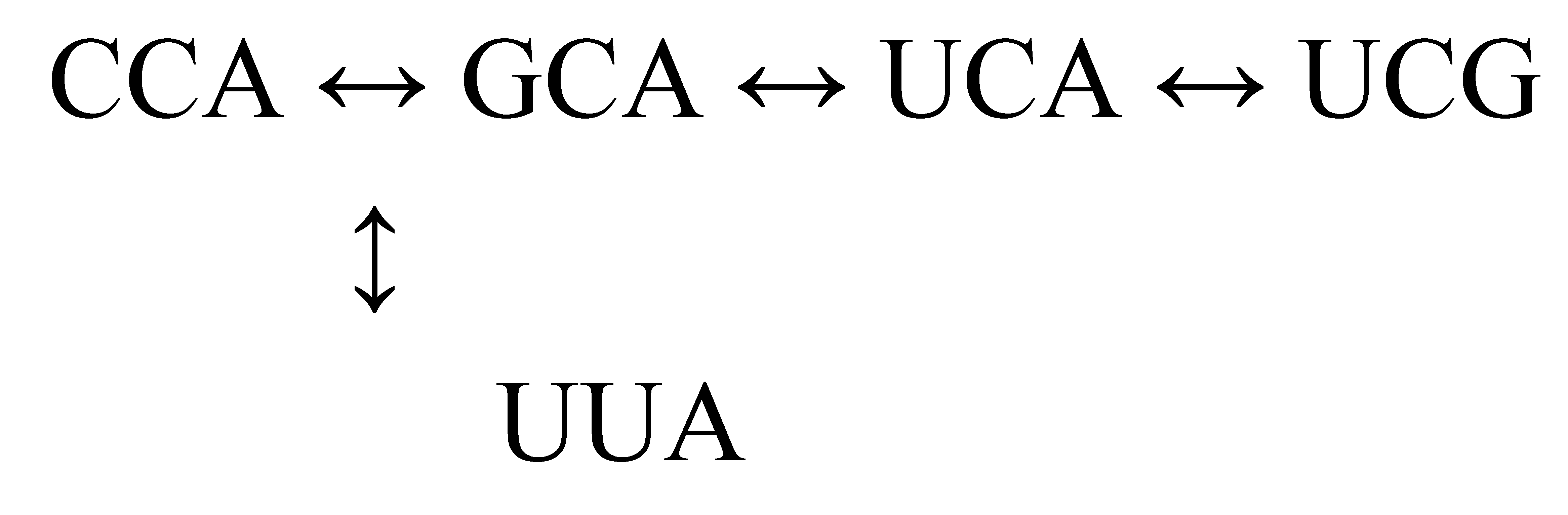

Earlier, mention was made of a theoretical mutation process by which isoacceptors of both related and unrelated aminoacylated tRNA could be connected; for example, tRNA

Trp(CCA) → tRNA

Cys(GCA) → tRNA

Gly(GCC) → tRNA

Asp(GUC). String matching tests performed on the tRNA component for each animal’s genome gave results (

Tables S8 and S9) supporting this thesis. Aside from some sort of directed process of mutation, the best alternative would be accumulated random errors during transcription (neutral drift). If alignments, discounting differences in anticodon triplet, between otherwise unrelated tRNA happened rarely, an error theory would be viable given a transcription mistake frequency of 10

−4 or lower (Rozov

et al. 2016). On that scale, a mammal in S phase of its cell cycle would need 27.4 years to accomplish one base change in the anticodon triplet: one mutation every 10,000 cell cycles, each cycle occurring once in twenty-four hours (for Hsa; Cooper and Adams 2022).

The problem is

Tables S8 and S9 demonstrate the same alteration occurs in up to forty genomes. If all nucleotides outside the anticodon triplet remain perfectly matched, as the data insists they must be, the law of large numbers militates against fortuitous coincidence, even if anticodon mutations need not take place within a single 27.4 year period for every animal, but could extend over millions of years. In that time, other nucleobases would also be susceptible to the same neutral drift process, causing loss of alignment in other portions of tRNA molecules. Systemic mutation is a preferred explanation for these observations coupled with the notion that resultant sequence matched alignments are purposeful, so are maintained during evolution once they occur in each genome.

Mutations involve purine/purine, purine/pyrimidine, pyrimidine/pyrimidine for isoacceptor pairs, and may occur in any anticodon position, but mostly at the wobble base. Occasionally, a trio of strings are participants: tRNAPhe(GAA), tRNASer(GGA), tRNATrp(CCA) of 73 nt in Oar is an example; notice the length for the serine isoacceptor is unusual, meaning it must derive from phenylalanine tRNA via single nucleotide polymorphism. Existence of internally matched sequences does not typically reveal from which direction alteration occurred: tRNAPro(AGG) and tRNAPro(CGG) are perfectly aligned, except for anticodon triplet, in all forty animals, and tRNAPro(UGG) is a match for all but Ame. A forty-for-forty outcome also applies to the combination tRNAVal(AAC) and tRNAVal(CAC), with tRNAVal(UAC) a match in the Bta genome.

Although directionality is not ordinarily obvious, exceptions for which they could be elucidated have been cited already. In this respect, Vpa is a major contributor to unraveling the mysteries of systemic mutation. It transcribes 1436 unique tRNA, more than twice that in Laf (694), its closest rival (

Table 2). Of these, 833 (58.0%) are tRNA

Ala(AGC) (

Table S4) of every length 71−80 nt. This abundance does not appear for other isoacceptors in the genome, so its existence cannot be a consequence of a whole genome duplication event (Meyer and Schartl 1999). Another method to account for excessive accumulation is single gene multiplication. Supposedly, most duplicates are silenced after several million years (Lynch and Conery 2000). It is unknown whether the majority of these genes have been rendered nonfunctional in this manner.

Still another route justifying tRNA imbalance of this magnitude would require an exclusive gene transcription event occurring several times, but not shared by other tRNA genes, as if it were caught in a transcription loop repeat cycle. Reiterative transcription refers to a loop, but usually constitutes a process of repetitive single nucleotide addition, mainly A or U, to 3’ termini (Turnbough Jr. 2011). A distinction between gene duplication and gene reiterative transcription is clear-cut: in the first, a gene is duplicated X times, with each replicant transcribed once, leading to X copies; in the second, a single gene is transcribed X times. As envisioned, gene reiterative transcription would be analogous to chemical polymerization, as in conversion of ethylene to polyethylene. Of course, questions arise immediately: (i) what would be the genetic equivalent of a polymer initiation reagent? (ii) what would be the genetic equivalent of a polymer termination reagent?

A biochemically obvious reason why a species should contain this many isodecoder genes for a single isoacceptor is missing, regardless of the process by which it came to be. Could its natural habitat necessitate this response as a survival mechanism? Perhaps the surplus is intended to compensate for the animal being prone to deleterious, even lethal, mutations. The most recent sequencing of the Vpa genome acknowledged the presence of more recognizable protein coding sequences than is found in camel, cow, sheep (Richardson

et al. 2019). However, this would fail to explain excessiveness of a single isoacceptor. Whatever the purpose might be, matched sequences within the genome reveal unusual agreements (

Tables S8 and S9) absent in other mammals. Undoubtedly, mutation direction proceeded as AGC → GGC, AGC → AUC, AGC → AGG, AGC → AAC, respectively.

73 nt: tRNAAla(AGC) with tRNAAla(GGC)

75 nt: tRNAAla(AGC) with tRNAAla(GGC) (two pairs)

73 nt: tRNAAla(AGC) with tRNAAsp(AUC)

73 nt: tRNAAla(AGC) with tRNAPro(AGG)

73 nt: tRNAAla(AGC) with tRNAVal(AAC) (three pairs)

Of all tRNA isoacceptors, two stand out as unambiguously special because they possess activities irreplaceable by others: (i) tRNA

iMet(CAU) is a key part of the Start codon/anticodon mRNA/tRNA couple; (ii) tRNA

Cys(GCA) , and in some genomes tRNA

Cys(ACA), because its attached cysteine is transformable into a dimer whose disulfide bonds have substantial effect on secondary protein structure. For tRNA

iMet(CAU), a single isodecoder sequence is contained in all mammals, confirming its structural demand for special binding affinity with eukaryotic initiation factors (

Table S11). Transfer RNA

Cys(GCA) is encoded the most times, and represents the most unique sequences, for these animals, excluding tRNA

Ala(AGC) whose totals are inflated by Vpa (

Table S4). As diametric opposite of initiator methionine tRNA singularity, cysteine tRNA multiplicity also suggests precise order and location of individual nucleotides are responsible for providing information; in this case, on which pair of cysteines engage in S−S bond formation.

Unsurprisingly, the consensus initiator methionine sequence lacks a duplicate in organism types other than vertebrates. Bacteria, Archaea, plants, fungi, invertebrates fail match tests (

Table S13a), which supports the repetitive claim throughout this paper portraying them as poor models from which to draw conclusions about features concerning translational processes in mammals. Either tRNA

iMet(CAU) strings matter or do not. If number and location of nucleotide changes lack significance, then no variable position can participate in rate critical interactions among tRNA, initiation factors, GTP within ternary complexes commencing translation. If relevant, they probably cause rate and/or thermodynamic stability differences during translation onset. Possible also, and not a mutually exclusive option, is that initiation factors for taxonomic groups (vertebrates, invertebrates, fungi, plants, prokaryotes) are structurally diverse in order to compensate for alterations in tRNA sequences (Lütcke

et al. 1987; Gu

et al. 2010). If no universal eukaryotic initiation factors exist, demarcation occurred around 500 million years ago during vertebrate and invertebrate separation. Employing nonvertebrates as models for features characteristic of translation related to vertebrate tRNA is like using tricycles to model jet airplanes because both have wheels.

Final protein conformations are frequently intimately connected to disulfide bond formation; 29% of all expressed proteins in Eukarya are said to contain cysteine-cysteine linkages (Narayan 2021). In addition, cysteine sulfur is readily oxidizable to sulfenic acid (RSOH), sulfinic acid (RSO2H), sulfonic acid (RSO3H), where R = HO2CCH(NH2)CH2− (remainder of amino acid). A survey of X-ray crystal structures in the Protein Data Bank turned up 1171 sulfenic acids, 469 sulfinic acids, 382 sulfonic acids (Ruiz et al. 2022). The authors issued a caveat: X-ray irradiation may promote oxidation, so molecules found might not all be biologically relevant. This tally does not include a plethora of derivatives, such as thioesters and thioamides (Poole 2015). The two most prominent oxidants are hydrogen peroxide and glutathione (Schulte et al. 2020), both abundantly present in cells. A diversity of tRNACys(GCA) sequences, and occasionally tRNACys(ACA), encoded in these animals should now be readily comprehensible.

It is hypothesized isoacceptors and their constituent isodecoders might not facilitate translation of the same amino acid. This proposition is contrary to conventional wisdom. How might nondegeneracy be justified as prima facie plausible beyond the structural impediments to redundancy already articulated? Again, tRNA sequence transcription errors are estimated to appear at a frequency of 10−5 to 10−4 (one event in 10,000−100,000 molecules) along with a similar misacylation rate (Rozov et al. 2016). Given a typical protein of 300−500 residues, the probability of introducing incorrect amino acids by either route is low.

Among twenty-nine tRNA perfect nucleotide match sequences appearing in all forty mammals (

Table 5) is exactly one for tRNA

Cys(GCA) despite more isodecoders (forty-three) held in common between two or more animals compared to every other isoacceptor. Of this total, six others are encoded in over twenty genomes and thirty-six are found in 2−6 species (

Table S11). It is suggested the consensus string is used for unmodified cysteine not undergoing disulfide bond formation in any protein, while the remainder contain precise information signifying which pair of cysteines join together, or are converted into another type of modification for employment in select instances. At the other end of the spectrum is lysine, which appears twice among these twenty-nine: one for each isoacceptor and possessing the same length (73 nt). What can it mean in practical terms to claim codons AAG and AAA (synonymous with tRNA

Lys(CUU) and tRNA

Lys(UUU) respectively) fail to translate into the same lysine? Consensus sequences are shown with underlined residues denoting differences:

GCCCGGCUAGCUCAGUCGGUAGAGCAUGAGACUCUUAAUCUCAGGGUCGUGGGUUCGAGCCCCACGUUGGGCG

GCCCGGAUAGCUCAGUCGGUAGAGCAUCAGACUUUUAAUCUGAGGGUCCAGGGUUCAAGUCCCUGUUCGGGCG

Ideally, one would consider these as constituting a no frills option translating the canonical amino acid structure absent post-translational modifications. Notice: (i) identical beginning 5’ and ending 3’ sets of nucleotides containing the amino acid attachment stem; (ii) eleven changes (15%) in isolated clusters of 1−3 nucleobases; (iii) these mutations are of various types distributed unevenly throughout the strings, where some alterations are Watson-Crick complementary (CG, AU), some purine/pyrimidine (AC, GU), some purine/purine (AG), some pyrimidine/pyrimidine (CU).

The questions are obvious. If both strings translate the no frills option faithfully, then what do the diversity of mutations signify? If both strings translate the no frills option faithfully, then why do all forty animals encode both sequences, yet not also encode other isodecoders with such unanimity? No shortage exists (

Table S11): there are fifteen other CUU versions shared by at least two mammals, and twenty-four more for UUU. Aside from one CUU isodecoder, none of the fourteen remaining are encoded in greater than seven species. Likewise, twenty-four UUU isodecoders are, except for two, not found in more than six animals. The variety of

in vivo relevant modified lysines is extensive (Wang and Cole 2020), and it is at least plausible some may form while still in the ribosomal environment.

There still remains the binary option: either differences in sequence matter or do not. Can it be alleged variation is insignificant? Yes, but this postulate is contrary to an image of a refined evolutionary process where errors in transcription and/or translation—stages characterized as having a large number of moving parts engaged in a series of multiple steps—are very rare, as has been stipulated. A fundamental paradigm of Darwinian Evolution is: nature does everything for good reasons. Almost by definition, lethal or detrimental mutations are typically removed from genomes. Retained diversity in isoacceptor tRNA coding must serve meaningful purposes, must be important by design.

If this hypothesis is correct, remaining isodecoders shared nonunanimously indicate mutations in tRNA sequence are either (i) benign, producing the same amino acid or (ii) induce translation of amino acids in modified forms. Retention as a historical record of nucleotide mutation is reasonable. The second choice suggests isoacceptors and their subordinate isodecoders are not redundantly referencing the same amino acid. Where is the dividing line? How many nucleobase changes (mutations, not modifications) are sufficient to result in subsequent amino acid structural conversion?

It cannot be stated definitively due to a paucity of information; hence, a compelling incentive for experimental testing exists. Theoretically, single nucleotide mutation could lead to amino acid alterations ranging from simple (methylation) to complex (glycosylation) to esoteric (L → D stereoisomer change; Ehmsen et al. 2013). On the other hand, single nucleobase changes might be minor alterations due to transcriptional mistakes, rare as they appear to be, leading over time to neutral drift emendations. When the same sets of mutations are observed in phenotypically and phylogenetically divergent species, then base switching cannot be due to simple transcriptional laxity. It is reasonable to theorize that, if positioned in a crucial location, one nucleotide might signify assistance in producing a modified amino acid after aminoacylation has occurred. By argument extension, multiple bases could likewise assist in establishing structural changes eventually resulting in functional adjustments. A nonexhaustive catalog of conceivable transformations, besides those already mentioned, includes acetylation, hydroxylation, phosphorylation, ubiquinylation, methionine oxidation.

If it is still insisted there is no innate difficulty in affixing no frills labels to both tRNALys(CUU) and tRNALys(UUU), asserting they illustrate degenerate isoacceptors, what about those thirty-nine other strings unevenly distributed among species? It would demand a convoluted reasoning process to maintain a belief in unmitigated redundancy pertaining to all lysine isodecoders. If, however, it is conceded there is a two-fold division between the unanimous two and the remainder—in physics, this operation would be called a symmetry break—then a basis for distinction can only lie in admitting sequence is the decisive factor. In that case, there must be additional divisions, other symmetry breaking operations, involving thirty-nine strings: species ABCDE possess one sequence in common, but only ADF share another isodecoder.

It would appear there is a means to circumvent this reasoning chain. Instances of evolution-based intentional diversity among isodecoders appeared as early as 2006 when Dittmar et al. suggested they permitted translational control of product proteins beyond that presented through the dictates of mRNA sequences alone (Dittmar et al. 2006). This paper’s title announced Tissue-specific Differences in Human Transfer RNA Expression. By this account, functional differences between isodecoders—where this term appeared for the first time—indicated anatomical locations of operation, but made no mention of a lack of isoacceptor redundancy. To these authors. all tRNALys(CUU) and tRNALys(UUU) encoded the no frills option (canonically structured lysine), but each isodecoder had predominant expression and utilization in diverse organs. This proposition was later confirmed in a mouse study: eighty-six of 210 (41%) isodecoder tRNA showed tissue-dependent expression variance among cortex, cerebellum, medulla oblongata, spinal cord, heart, liver, tibialis (Pinkard et al. 2020).

This sophisticated explanation of functional distinctions does not circumvent the possibility here imagined: not all lysines, to continue the example, are canonical structures because chemical adjustments contribute substantively to those tissue-specific expressions. The explanation offered by Dittmar et al. and Pinkard et al. is not mutually exclusive to the current suggestion. According to a database of amino acid modifications (dbPTM; Li et al. 2022), cysteine and lysine undergo more change types in vivo than other amino acids. Perhaps Geslain & Pan were unwittingly alluding to amino acid structural alterations when positing that different tRNA sequences led to functional distinctions in aminoacylation efficiency as well as ribosomal binding during translation (Geslain and Pan 2010).

Source dbPTM is specifically denominated post-translational modifications, but no justification exists for the view they must be so constrained. It is now commonplace to explore co-translational folding when it was once believed all protein secondary and tertiary conformational structural changes transpired after a molecule was assembled. Nonetheless, post-translational folding is still mostly true (Ellgaard et al. 2016): folding time for a fifty kilodalton protein takes 15−30× as long as synthesis (30−60 min vs. 2 min).

Analogously, pre- or co-translational amino acid modifications could be viable developmental stages. Pre means during or after tRNA aminoacylation, whereby nucleotides assist in formulating compositionally altered amino acids; co signifies once canonical aminoacylated tRNA are engaged in association with the A site of the ribosome.

Mechanistically, the pre version of amino acid modification begins with synthetases responsible for initial aminoacylation. After transcription in the nucleus, tRNA are exported to the cytoplasm for first order amino acid binding catalyzed by synthetases. Amino acids, bound or unbound, might be structurally altered while in the cytoplasm prior to movement towards ribosomes and initiation of translation because the medium contains molecules able to serve as reagents and catalysts (Luby-Phelps 1999) assisted by nucleotides in tRNA acting as interaction partners to bind those needed. Also possible is aminoacylated tRNA being returned (cytoplasm → nucleus) for adjustments necessitated by encounters with stresses of diverse types (Avcilar-Kucukgoze and Kashina 2020).

If no structural changes are warranted prior to beginning protein construction, then the alternate pathway for amino acid modification (co version) is available. Once the tRNA is base paired with mRNA and the ternary complex formed with cofactors and GTP, there is room to access amino acid sidechains by modifying reagents present near the ribosome because the attachment point is orthogonal to the codon/anticodon interaction position. As in the pre version, specific nucleotides would be involved, only this time by connecting with rRNA or ribosomal proteins acting as catalysts for the conversion. Although no evidence points to an in vivo function for ribosomal proteins beyond stabilization of rRNA comprising ribosomal subunits (Draper and Reynaldo 1999), tRNA might develop transitory associations through: (i) positively charged amino acids in nearby proteins ionically bound to negatively charged/phosphate within tRNA; (ii) protein hydrophilic amino acids or rRNA nucleotides hydrogen bonding to ribose 2’-OH in tRNA; (iii) direct hydrogen bond formation between hydrophilic amino acids and tRNA nucleotides; (iv) aromatic ring pi bond stacking between aromatic amino acids and nucleotide bases.

Amino acid acceptor stem and TΨC loop interact with the large subunit, in contrast to anticodon and D loop connections to the small subunit (Harish and Caetano-Anollés 2012). Transfer RNA contacts with ribosomal proteins while in the A site include uS12, uS13, uL16, plus uS9, uL5, uL16 when in the P site (Timsit

et al. 2021). This list omits potential Eukarya-specific ribosomal protein participation. These agents would be likely, not necessarily sole, candidates for incipient catalysis of modified amino acid generation. Postulating points of contact between tRNA nucleotides and amino acids present in ribosomal proteins, or between rRNA expansion segments and tRNA, introduces meaning for finding isodecoders of different lengths related to the same anticodon triplet within each genome (

Tables S2 and S3).

Length variance creates positional adjustments by altering topological relationships: tRNA

Ala(AGC) strings of 72 nt do not permit nucleobases to occupy the same space in its ribosomal environment as do nucleotides with 73 nt tRNA

Ala(AGC). Although the adjustment in nanometers is minor within the absolute confines of an L-shaped molecule, a one base movement relative to spatially immobilized amino acids in ribosomal proteins, or to the subunits themselves, could alter potential interactions allowing modifications within tRNA-bound residues. If 72 nt → 73 nt extensions might be significant, imagine the consequences for tRNA

Ala(AGC) strings whose length varies from 69 nt (Dor) to 80 nt (Vpa), a range different from those encoded by allegedly degenerate isoacceptors tRNA

Ala(CGC) and tRNA

Ala(UGC) (

Table S2). The data shows the same argument is applicable to all other isoacceptors regardless of associated amino acid.

Transfer RNA: (i) of different lengths per isoacceptor cannot all refer to canonical amino acids without structural modifications; (ii) of a single length having matching isodecoder sequences, but not present in all species, cannot all refer to canonical amino acids without structural modifications; (iii) of a single length with matching isodecoder strings in all species could refer to canonical amino acids without structural modifications if it represents the only such set for that isoacceptor; (iv) of a single length with matching isodecoder sequences in all species and encoding the most identical copies probably refers to a canonical amino acid without structural modifications.

A second speculation regarding tRNA roles in translation concerns influencing folding patterns as proteins are constructed. A prime example has been declared: secondary structural organization through cysteine dimerization. If many cysteines are present, S−S bond construction could start before the entire molecule is synthesized to minimize likelihood of improper linkages distorting eventual molecular shapes and impeding intended activity. Cysteine dimerization has been found to take place as just described for bovine protein γB-crystallin. From its crystal structure, Cys18, Cys22, Cys78 are observed to be in close proximity, with four more cysteines present (Cys15, Cys32, Cys41, Cys109). Measuring translation speed for variable length partial primary sequences indicated folding took place within the Ribosomal Exit Tunnel amid S−S bond formation between Cys18 and Cys22, possibly through glutathione assistance (Schulte et al. 2020).

Tunnel dimensions are estimated at 100Å long plus 10−20Å wide (Wilson and Beckmann 2011). Approximately thirty residues are required to span the distance, and growing chains are visible when their lengths extend 60Å from a tRNA molecule situated in the P site. Given spatial restrictions, both disulfide bond-forming cysteines would need to be within that thirty residue limit if reaction were to take place before departure from the Exit Tunnel, as occurs in γB-crystallin, while still being subject to influence by tRNA. Interaction of cysteines with tRNA portions (nucleobase, ribose, phosphate), which need not be the same component for both, might be sufficient to bring them into close proximity enabling covalent bond construction.

Codons are known to vary in translation speed (Zouridis and Hatzimanikatis 2008; Buhr et al. 2016), and rate variance to depend more on precise isodecoder sequences than copy number counts (Zhou et al. 2016). Assumptions have been made that rate is inversely proportional to available co-translational folding time (O’Brien et al. 2014). Tunnel geometry offers sufficient space to initiate α-helix formation (Bhushan et al. 2010; Nilsson et al. 2015) as well as β-sheets (Marino et al. 2016). Protein folding could begin before reaching the Exit Tunnel, starting as early as when a segment arrives in the Peptidyl Transfer Center, if the needed amino acids are assembled and size of the PTC permits.

None of the research on co-translational folding within the Exit Tunnel makes mention of tRNA inclusion in the procedure, but has not been investigated, so is an open possibility awaiting study. As with proposed amino acid modification, it is conceived isodecoder tRNA in ribosomal A and P sites participate in folding efforts through interaction with ribosomal proteins and rRNA extension segments. Implicated tRNA must remain available before disappearing through the E site. If it could be evaluated, isodecoder residence time should correlate with situational chain folding events. Differential contact between tRNA and ribosomal proteins or rRNA explains why isodecoders do not vertically align even if a single length, justifying observations of skewness among strings, and certainly rationalizes sequence length differences.

Unicellular species display linear correlations between codon usage and tRNA abundance, but a connection between these variables is uncertain for Eukarya (Novoa et al. 2012). Most archaeal species encode one isodecoder per isoacceptor (Laibelman 2022) since multiple copies are pertinent to only 5.7% of total sequences; therefore, an inherent relationship between tRNA abundance and codon usage will be uncovered. A fundamental reason for the uncertainty within Eukarya is now capable of elucidation. There are two ways to assess copy number: (i) by reliance on exact multiple copies only; (ii) by including all isodecoders of variable length. The distinction is not solely with respect to number, but to assumptions underlying each method. Counting by (i) adheres to the rationale that like structure implies like function is an ironclad rule; following (ii) presumes functional degeneracy is maintained despite variable sequence structure and length.

Associated with the issue of codon interchangeability is the theme of codon usage bias. These two concepts are oppositional, for bias between isoacceptors implies absence of degeneracy: some aspect or feature endemic to these sequences must end the tie implied by a concept of redundancy. It was referred to earlier as a symmetry-breaking operation. The voluminous literature on codon usage bias absorbed into the HiveCuts database (

https://hive.biochemistry.gwu.edu/cuts/) provides a distorted portrayal of features and significance by failing to accommodate agreement between mRNA activity and tRNA availability. Assessing statistical use of codons in isolation is like calculating the speed of a race car without taking into account identity and personal abilities of the driver: it can be done but is a flawed indicator of actual performance.

Codon usage bias intrinsically implies anticodon usage bias, an idea consistent with the notion of nondegeneracy exhibited through differential properties such as tRNA sequence and length. If preferred length for isoacceptors captures the set of isodecoders transcribed most often, optimal codon designations depend on usage for a particular assigned task, such as selective tissue distribution based on isodecoder. Colloquially, this is known as the right tool for the right job. As admitted by Hanson & Coller, difficulty in parsing effects of codon bias on translation efficiency derives from additional factors influencing codon usage (Hanson and Coller 2018).