Submitted:

20 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Safety Data Analysis

- High dimensionality: The number of AEs can be large (hundreds or even thousands), especially during the post-approval marketing phase when the medicine becomes available for broad populations. However, only a few of these AEs are significant for new discoveries about the product’s clinical safety.

- Sparsity: Most types of AEs are rare, especially in the stage of post-market surveillance, due to factors such as selective participant profiles in clinical trials, rare events in large populations, long-term effects and drug interactions, and so on.

- Weak signal: Certain AEs may exhibit a low signal strength related to the drug or vaccine under investigation, which potentially impact the efficacy of the methodologies employed to detect the association.

- Complex correlation: AEs may demonstrate complex correlation structure, either positive or negative, among themselves, which poses significant challenges in identifying drug or vaccine associated AE signals.

1.2. Apriori Method

2. Method

2.1. Improved Apriori Method

2.2. Numerical Study

2.2.1. Simulation Studies

2.2.2. VAERS Data

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Study

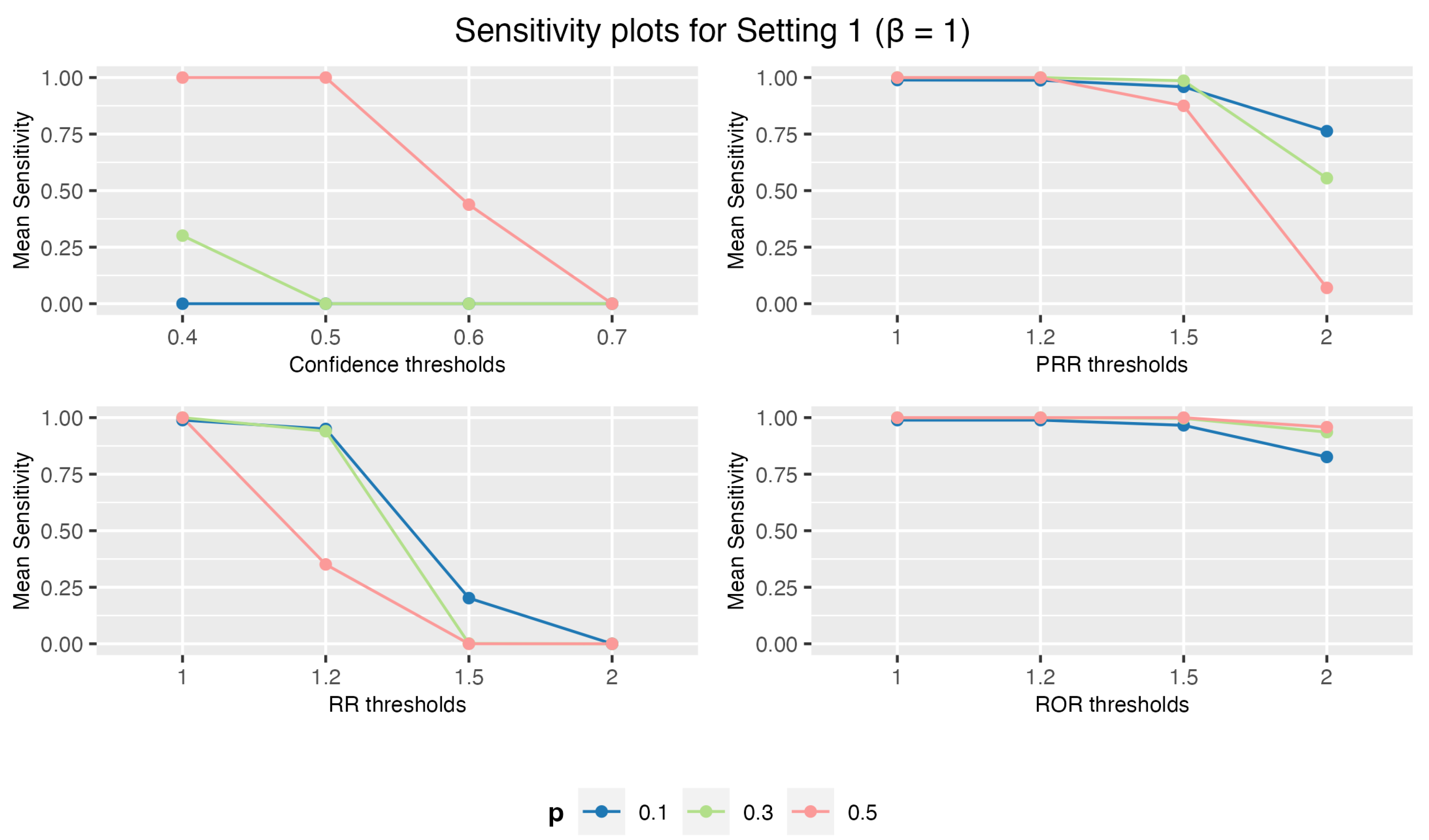

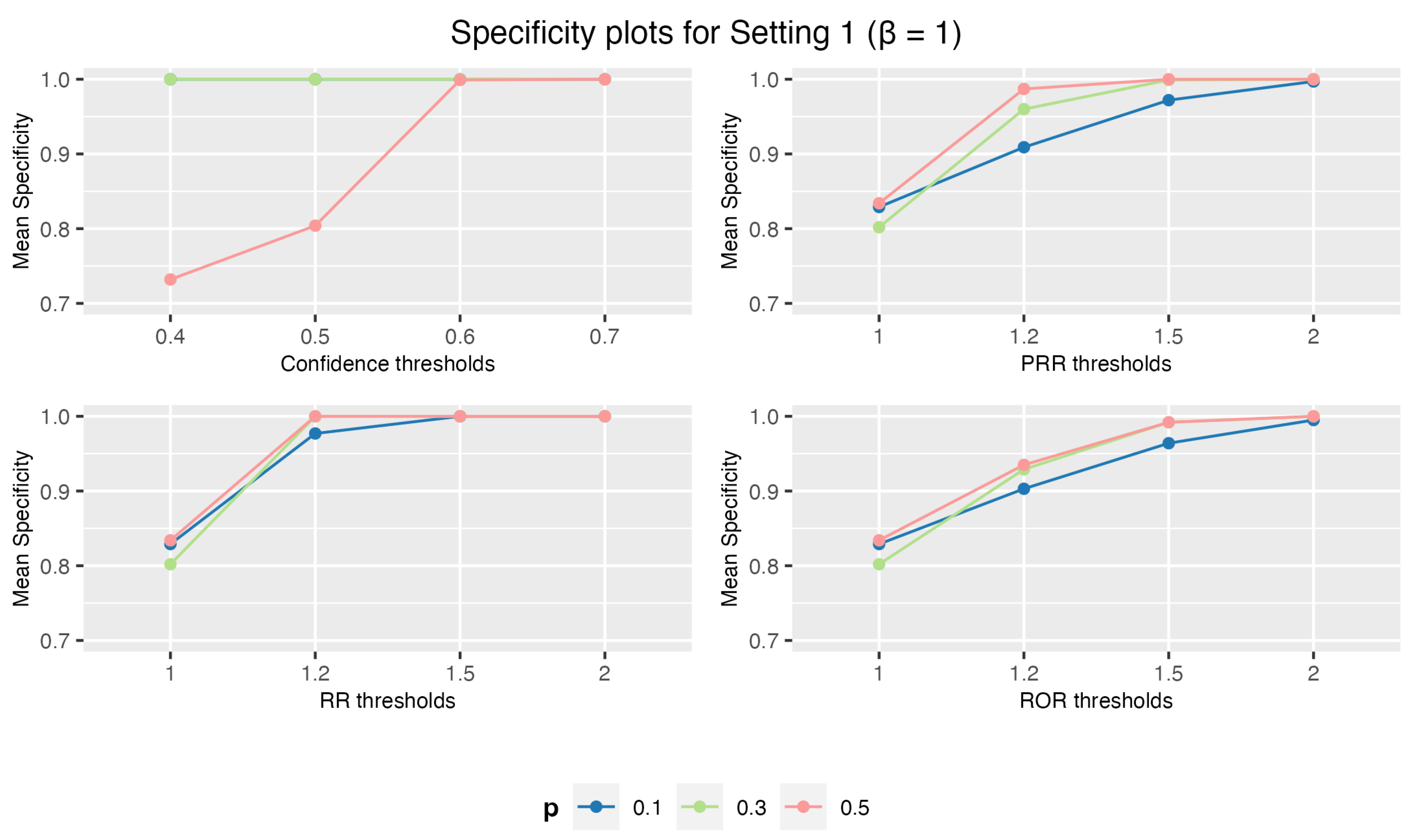

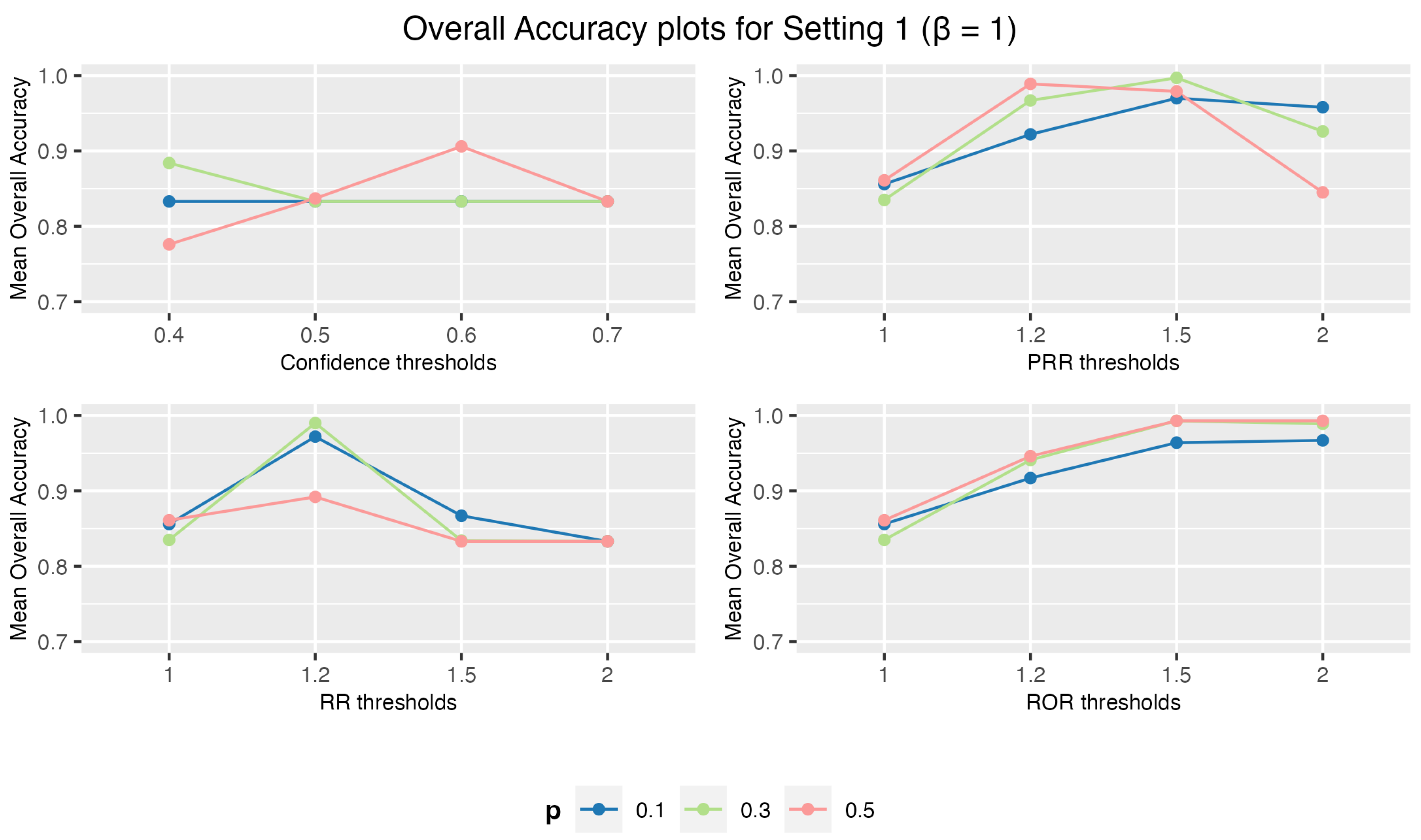

3.1.1. Setting 1: 1 Drug and 3 AEs

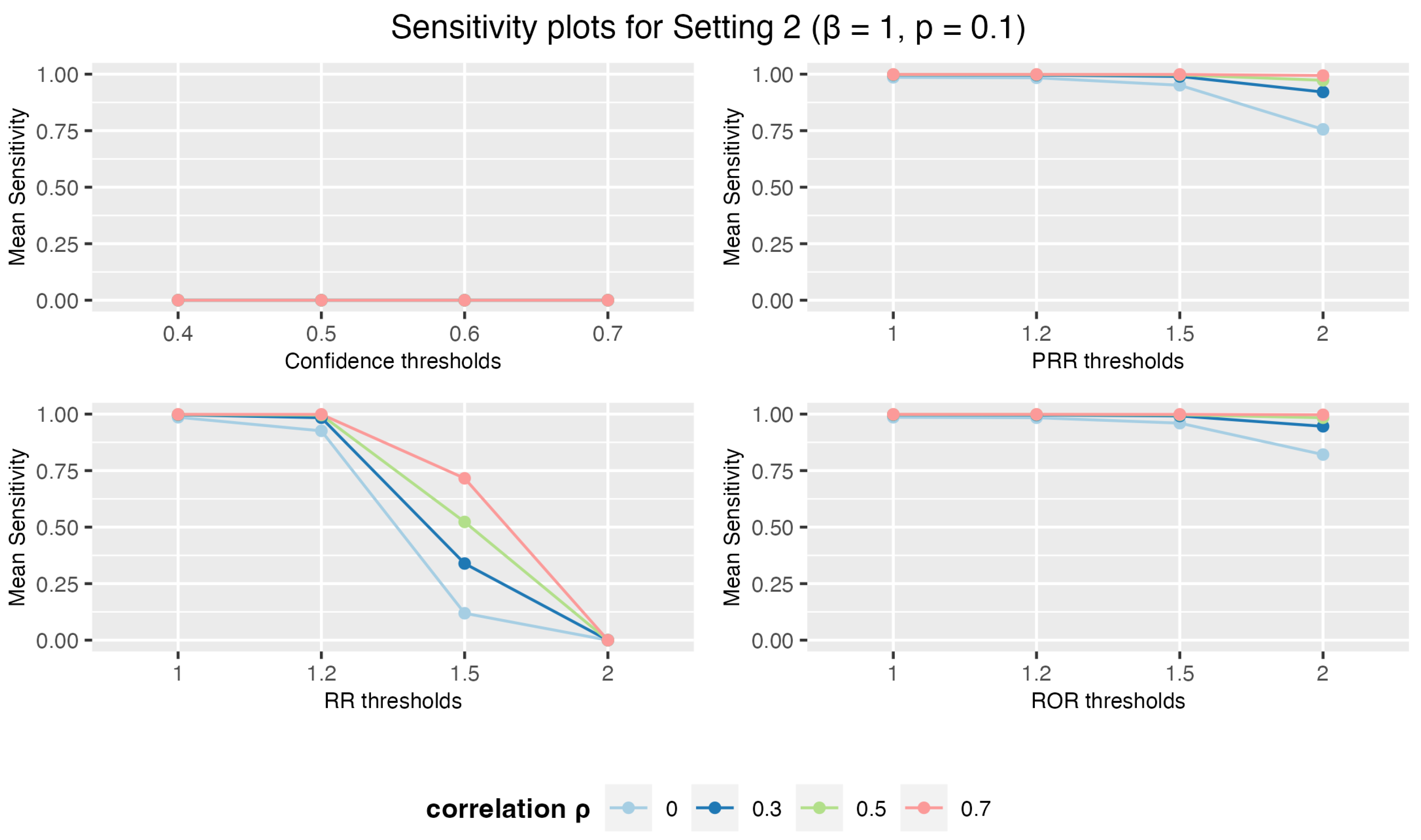

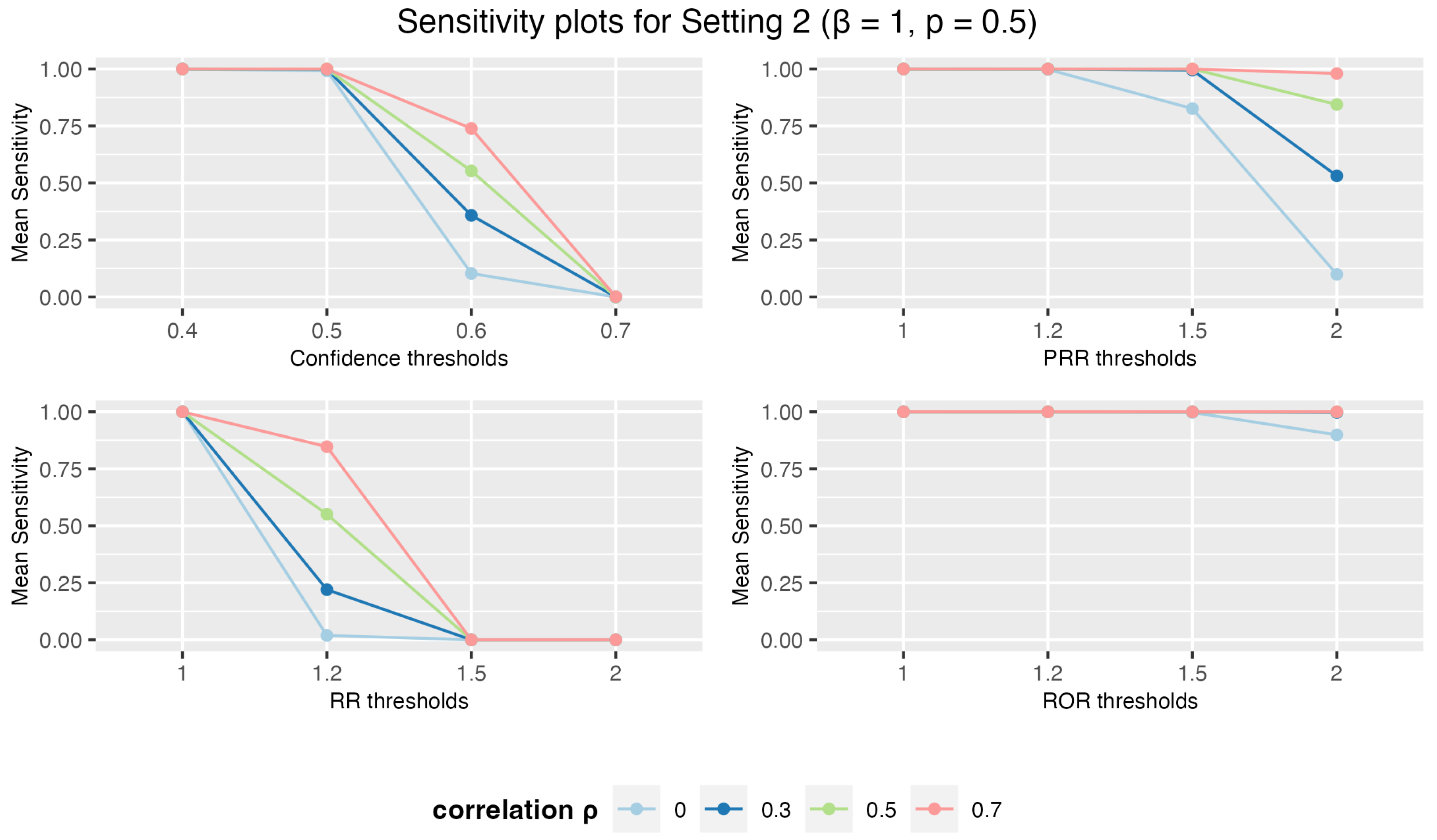

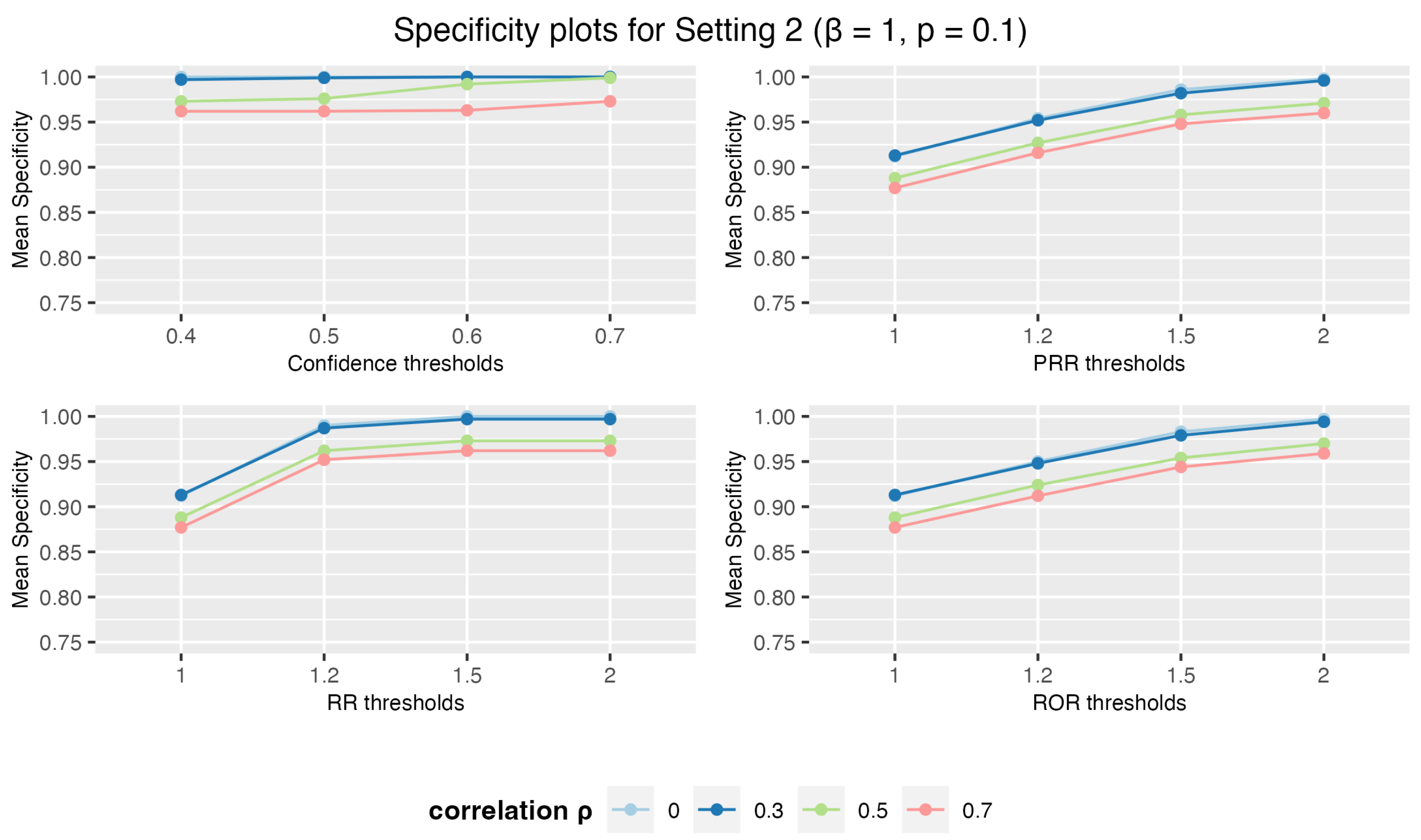

3.1.2. Setting 2: 3 Drugs and 5 AEs

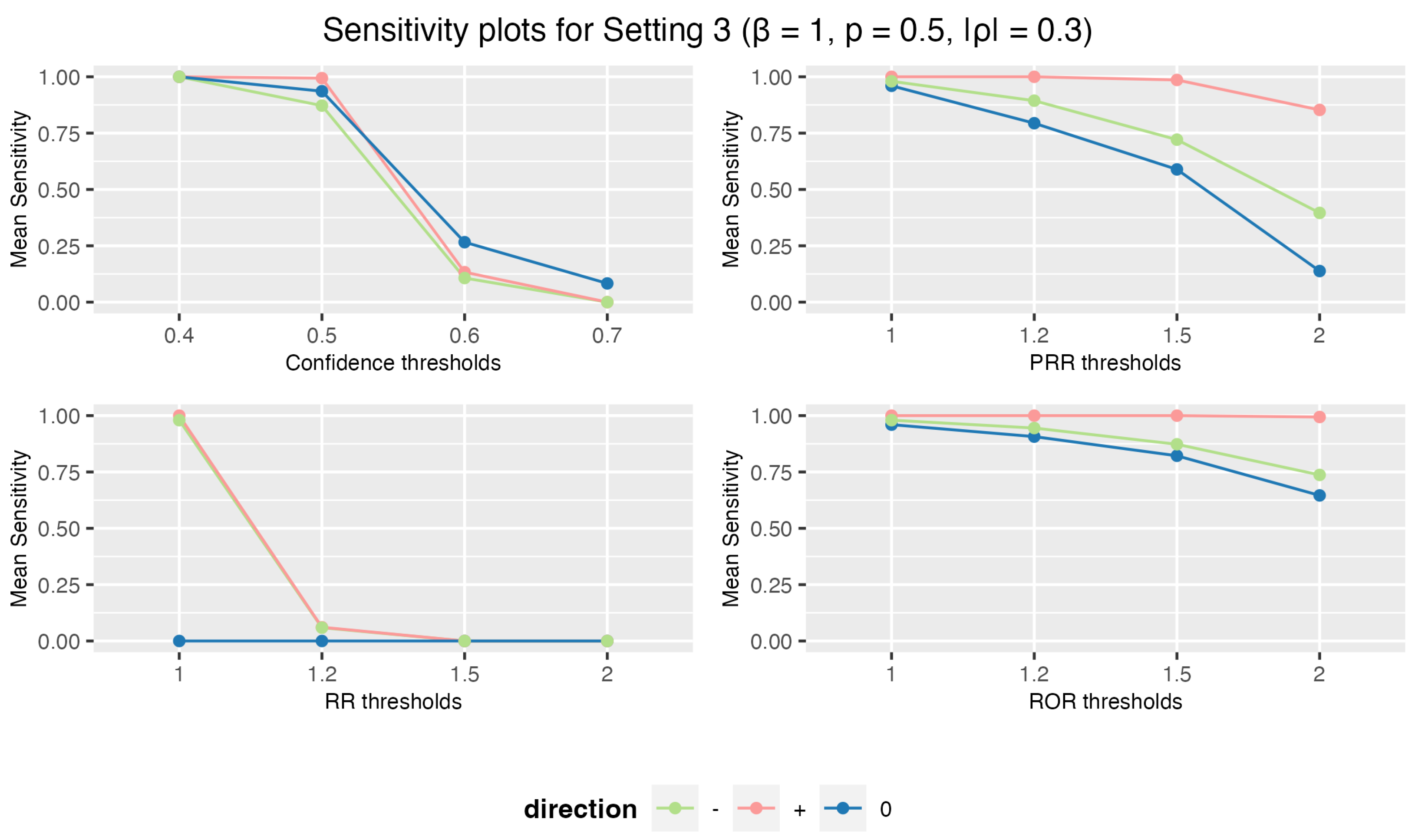

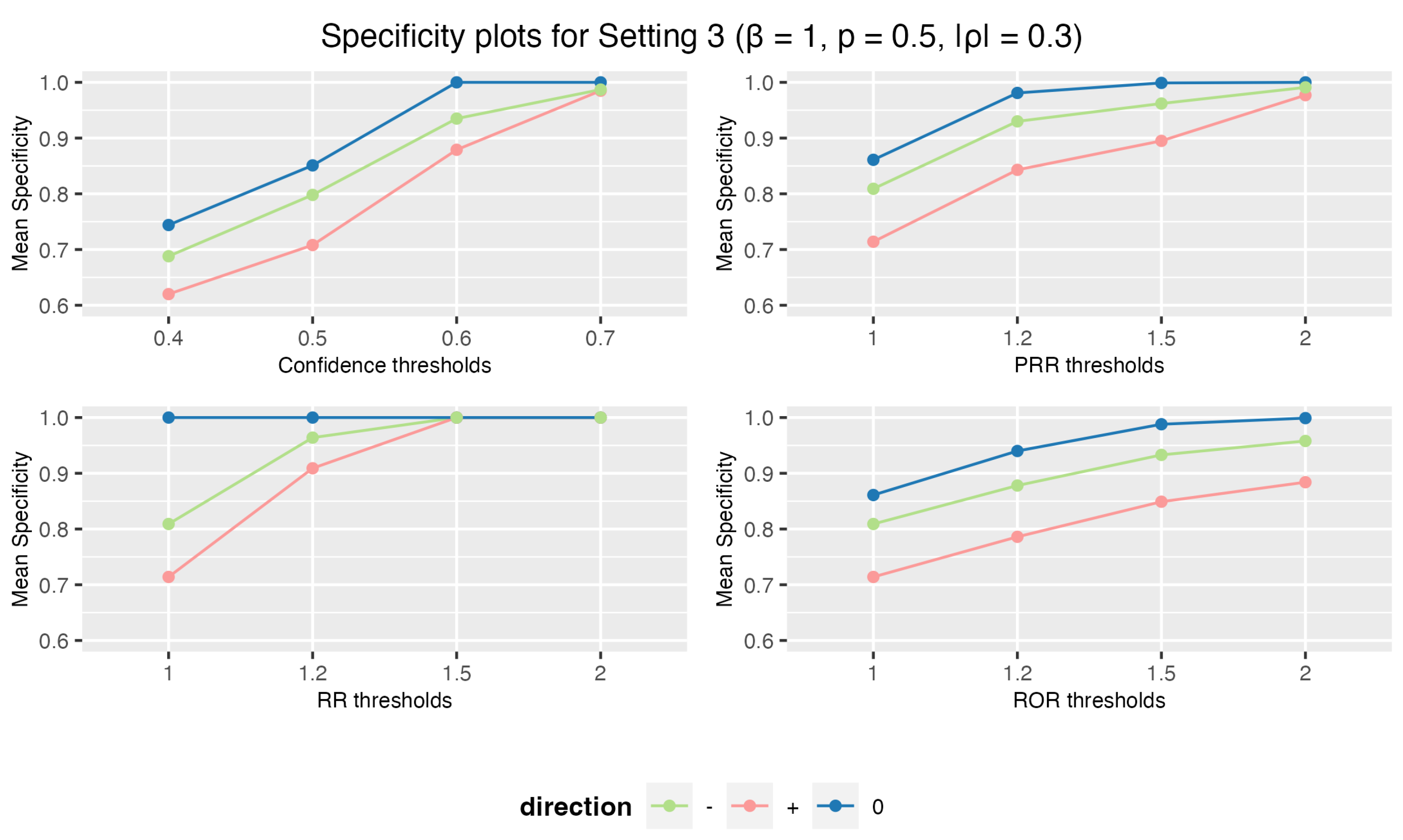

3.1.3. Setting 3: 5 Drugs and 10 AEs

3.2. VAERS Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Importance of Pharmacovigilance, 2022. By WHO Quality Assurance and Safety Team. ISBN 9241590157. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- Wax, P.M. Elixirs, diluents, and the passage of the 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Annals of internal medicine 1995, 122, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargesson, N. Thalidomide-induced teratogenesis: History and mechanisms. Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews 2015, 105, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibbald, B. Rofecoxib (Vioxx) voluntarily withdrawn from market. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal 2004, 171, 1027–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumholz, H.M.; Ross, J.S.; Presler, A.H.; Egilman, D.S. What have we learnt from Vioxx? BMJ : British Medical Journal 2007, 334, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra, D.V.; Adewale, A.J. Flagging clinical adverse experiences: reducing false discoveries without materially compromising power for detecting true signals. Statistics in Medicine 2012, 31, 1918–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Chen, B.E.; Sun, J.; Patel, T.; Ibrahim, J.G. A hierarchical testing approach for detecting safety signals in clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine 2020, 39, 1541–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, S.M.; Berry, D.A. Accounting for multiplicities in assessing drug safety: a three-level hierarchical mixture model. Biometrics 2004, 60, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amy Xia, H.; Ma, H.; Carlin, B.P. Bayesian hierarchical modeling for detecting safety signals in clinical trials. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics 2011, 21, 1006–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuMouchel, W. Multivariate Bayesian Logistic Regression for Analysis of Clinical Study Safety Issues. Statistical Science 2012, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Srikant, R.; others. Fast algorithms for mining association rules. Proc. 20th int. conf. very large data bases, VLDB. Santiago, Chile, 1994, Vol. 1215, pp. 487–499.

- Srikant, R.; Agrawal, R. Mining sequential patterns: Generalizations and performance improvements. Advances in Database Technology — EDBT ’96; Apers, P., Bouzeghoub, M., Gardarin, G., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1996; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lallich, S.; Teytaud, O.; Prudhomme, E. Association Rule Interestingness: Measure and Statistical Validation. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007, Vol. 43, pp. 251–275. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.H.; Kushniruk, A.W.; Borycki, E.M.; Greig, D. Application of the Apriori Algorithm for Adverse Drug Reaction Detection. In Detection and Prevention of Adverse Drug Events; IOS Press, 2009; pp. 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, R.; Chase, H.S.; Friedman, C. Mining multi-item drug adverse effect associations in spontaneous reporting systems. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Puijenbroek, E.P.; Bate, A.; Leufkens, H.G.M.; Lindquist, M.; Orre, R.; Egberts, A.C.G. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2002, 11, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.J.W.; Waller, P.; Davis, S. Proportional reporting ratios: the uses of epidemiological methods for signal generation. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1998, 7, S102. [Google Scholar]

- Szarfman, A.; Machado, S.G.; O’Neill, R.T. Use of screening algorithms and computer systems to efficiently signal higher-than-expected combinations of drugs and events in the US FDA’s spontaneous reports database. Drug safety 2002, 25, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyboom, R.H.; Hekster, Y.A.; Egberts, A.C.; Gribnau, F.W.; Edwards, I.R. Causal or casual? The role of causality assessment in pharmacovigilance. Drug safety 1997, 17, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harpaz, R.; Haerian, K.; Chase, H.S.; Friedman, C. Statistical Mining of Potential Drug Interaction Adverse Effects in FDA’s Spontaneous Reporting System. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2010, 2010, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Guo, X.J.; Xu, J.F.; Wu, C.; Sun, Y.L.; Ye, X.F.; Qian, W.; Ma, X.Q.; Du, W.M.; He, J. Exploration of the Association Rules Mining Technique for the Signal Detection of Adverse Drug Events in Spontaneous Reporting Systems. PLOS ONE, 7, e40561. [CrossRef]

- Rothman, K.J.; Lanes, S.; Sacks, S.T. The reporting odds ratio and its advantages over the proportional reporting ratio. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 13, 519–523. [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.J.W.; Waller, P.C.; Davis, S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2001, 10, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avery, A.; Anderson, C.; Bond, C.; Fortnum, H.; Gifford, A.; Hannaford, P.; Hazell, L.; Krska, J.; Lee, A.; McLernon, D.; others. Evaluation of patient reporting of adverse drug reactions to the UK ‘Yellow Card Scheme’: literature review, descriptive and qualitative analyses, and questionnaire surveys. Health Technology Assessment 2011, 15, 1–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhu, M.S.; Kannan, B. Detecting signals of drug-drug interactions using association rule mining methodology. IJCSIT) Int J Comput Sci Inf Technol 2013, 4, 590–594. [Google Scholar]

- Bate, A.; Lindquist, M.; Edwards, I.R.; Olsson, S.; Orre, R.; Lansner, A.; De Freitas, R.M. A Bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. European journal of clinical pharmacology 1998, 54, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, A.; Evans, S.J.W. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2009, 18, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, A.D.; Davies, S.J. A Note on Generating Correlated Binary Variables. Biometrika 85, 487–490. [CrossRef]

- Shimabukuro, T.T.; Nguyen, M.; Martin, D.; DeStefano, F. Safety monitoring in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS). Vaccine 2015, 33, 4398–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, M. Performance Measures in Binary Classification. International Journal of Statistics in Medical Research 1, 79–81. [CrossRef]

- Alberg, A.J.; Park, J.W.; Hager, B.W.; Brock, M.V.; Diener-West, M. The Use of “Overall Accuracy” to Evaluate the Validity of Screening or Diagnostic Tests. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2004, 19, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, S.W. Prevalence and Incidence. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Kempf-Leonard, K., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, 2005; pp. 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Decker, M.D.; Lewis, E.; Fireman, B.; Pool, V.; Greenberg, D.P.; Johnson, D.R.; Black, S.; Klein, N.P. Hypotonic-hyporesponsive Episodes After Diphtheria, Tetanus and Acellular Pertussis Vaccination. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2021, 40, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, R.; Patriarca, P.; Ensor, K.; Izikson, R.; Goldenthal, K.; Cox, M. Evaluation of the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of FluBlok® trivalent recombinant baculovirus-expressed hemagglutinin influenza vaccine administered intramuscularly to healthy adults 50–64 years of age. Vaccine 2011, 29, 2272–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.P. Recombinant trivalent influenza vaccine (Flublok®): a review of its use in the prevention of seasonal influenza in adults. Drugs 2013, 73, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin, S.A.; Smith, B.; Clarke, K.; Treanor, J.; Mabrouk, T.; Germain, M. A Phase I, Randomized, Controlled Trial to Study the Reactogenicity and Immunogenicity of a Nasal, Inactivated Trivalent Influenza Virus Vaccine in Healthy Adults. Human Vaccines 2005, 1, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, V.; Bonanni, P.; Castro, M.; Gabutti, G.; Franco, E.; Marchetti, F.; Prato, R.; Vitale, F. Combined hexavalent diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B-inactivated poliovirus-Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine; Infanrix™ hexa: Twelve years of experience in Italy. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2014, 10, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Zangwill, K.M.; Eriksen, E.; Lee, M.; Lee, J.; Marcy, S.M.; Friedland, L.R.; Weston, W.; Howe, B.; Ward, J.I. A population-based, postlicensure evaluation of the safety of a combination diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, hepatitis B, and inactivated poliovirus vaccine in a large managed care organization. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e1179–e1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeñaca, F.; Vázquez, L.; Garcia-Corbeira, P.; Mesaros, N.; Hanssens, L.; Dolhain, J.; Gómez, I.P.; Liese, J.; Knuf, M. Immunization of preterm infants with GSK’s hexavalent combined diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-hepatitis B-inactivated poliovirus-Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine: A review of safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine 2018, 36, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughlin, J.; Mast, T.C.; Doherty, M.C.; Wang, F.T.; Wong, J.; Seeger, J.D. Postmarketing evaluation of the short-term safety of the pentavalent rotavirus vaccine. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 2012, 31, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, E.J.; Thomas, R.; Duggan, C.; Asmar, B.I. Pentavalent rotavirus vaccine in infants with surgical gastrointestinal disease. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2014, 59, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, S.; Greenberg, D.P. A combined diphtheria, tetanus, five-component acellular pertussis, poliovirus and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. Expert Review of Vaccines 2005, 4, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silfverdal, S.A.; Coremans, V.; François, N.; Borys, D.; Cleerbout, J. Safety profile of the 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV). Expert review of vaccines 2017, 16, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botham, S.; Isaacs, D.; Henderson-Smart, D. Incidence of apnoea and bradycardia in preterm infants following DTPw and Hib immunization: A prospective study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 33, 418–421. [CrossRef]

| Suspected AE | All other AEs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected drug | a | b | a + b |

| All other drugs | c | d | c + d |

| Total | a + c | b + d | a + b + c + d |

| VAERS ID | VAERS ID Code | Vaccine Type | Vaccine Type Code | Symptoms | Symptoms Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0376710-1 | 0376710-1 | DIPHTHERIA AND TETANUS TOXOIDS AND ACELLULAR PERTUSSIS VACCINE + INACTIVATED POLIOVIRUS VACCINE + HAEMOPHILUS B CONJUGATE VACCINE | DTAPIPVHIB | DEATH | 10011906 |

| 0376710-1 | 0376710-1 | DIPHTHERIA AND TETANUS TOXOIDS AND ACELLULAR PERTUSSIS VACCINE + INACTIVATED POLIOVIRUS VACCINE + HAEMOPHILUS B CONJUGATE VACCINE | DTAPIPVHIB | UNRESPONSIVE TO STIMULI | 10045555 |

| 0376710-1 | 0376710-1 | INFLUENZA VIRUS VACCINE, TRIVALENT (INJECTED) | FLU3(SEASONAL) | DEATH | 10011906 |

| 0376710-1 | 0376710-1 | INFLUENZA VIRUS VACCINE, TRIVALENT (INJECTED) | FLU3(SEASONAL) | UNRESPONSIVE TO STIMULI | 10045555 |

| 0376710-1 | 0376710-1 | PNEUMOCOCCAL, 7-VALENT VACCINE (PREVNAR) | PNC | DEATH | 10011906 |

| 0376710-1 | 0376710-1 | PNEUMOCOCCAL, 7-VALENT VACCINE (PREVNAR) | PNC | UNRESPONSIVE TO STIMULI | 10045555 |

| 0376969-1 | 0376969-1 | INFLUENZA (H1N1) MONOVALENT (INJECTED) | FLU(H1N1) | COAGULOPATHY | 10009802 |

| 0376969-1 | 0376969-1 | INFLUENZA (H1N1) MONOVALENT (INJECTED) | FLU(H1N1) | DEATH | 10011906 |

| 0376969-1 | 0376969-1 | INFLUENZA (H1N1) MONOVALENT (INJECTED) | FLU(H1N1) | DRUG INTERACTION | 10013710 |

| Associated pairs | Non-associated pairs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selected | a (TP) | b (FP) | a + b |

| Not selected | c (FN) | d (TN) | c + d |

| Total | a + c | b + d | a + b + c + d |

| Parameter | Threshold | Selected pairs |

|---|---|---|

| Confidence | 0.4 | 33 |

| 0.5 | 30 | |

| 0.6 | 28 | |

| 0.7 | 26 | |

| PRR | 1 | 341 |

| 1.2 | 308 | |

| 1.5 | 272 | |

| 2 | 214 | |

| RR | 1 | 341 |

| 1.2 | 300 | |

| 1.5 | 246 | |

| 2 | 153 | |

| ROR | 1 | 341 |

| 1.2 | 321 | |

| 1.5 | 282 | |

| 2 | 232 |

| Vaccine Code | Vaccine Name | AE/Symptom Name | Support | ROR | PRR | RR | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTAPIPVHIB | DIPHTHERIA AND TETANUS TOXOIDS AND ACELLULAR PERTUSSIS VACCINE + INACTIVATED POLIOVIRUS VACCINE + HAEMOPHILUS B CONJUGATE VACCINE | UNRESPONSIVE TO STIMULI | 25 | 2.059 | 1.867 | 1.609 | 0.181 |

| FLU3(SEASONAL) | INFLUENZA VIRUS VACCINE, TRIVALENT (INJECTED) | NAUSEA | 8 | 2.061 | 2.002 | 1.681 | 0.056 |

| DTAPHEPBIP | DIPHTHERIA AND TETANUS TOXOIDS AND ACELLULAR PERTUSSIS VACCINE + HEPATITIS B + INACTIVATED POLIOVIRUS VACCINE | RESPIRATORY ARREST | 15 | 2.063 | 1.939 | 1.668 | 0.116 |

| RV5 | ROTAVIRUS VACCINE, LIVE, ORAL, PENTAVALENT | RESUSCITATION | 35 | 2.074 | 1.853 | 1.551 | 0.206 |

| HEPA | HEPATITIS A | INTENSIVE CARE | 4 | 2.074 | 1.972 | 1.870 | 0.095 |

| HIBV | HAEMOPHILUS B CONJUGATE VACCINE | PALLOR | 3 | 2.077 | 2.055 | 1.703 | 0.020 |

| HIBV | HAEMOPHILUS B CONJUGATE VACCINE | DEHYDRATION | 3 | 2.077 | 2.055 | 1.703 | 0.020 |

| HIBV | HAEMOPHILUS B CONJUGATE VACCINE | RHINORRHOEA | 3 | 2.077 | 2.055 | 1.703 | 0.020 |

| PPV | PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINE, POLYVALENT | INTENSIVE CARE | 3 | 2.082 | 1.977 | 1.900 | 0.097 |

| HIBV | HAEMOPHILUS B CONJUGATE VACCINE | APNOEA | 4 | 2.084 | 2.055 | 1.703 | 0.027 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).