Submitted:

22 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

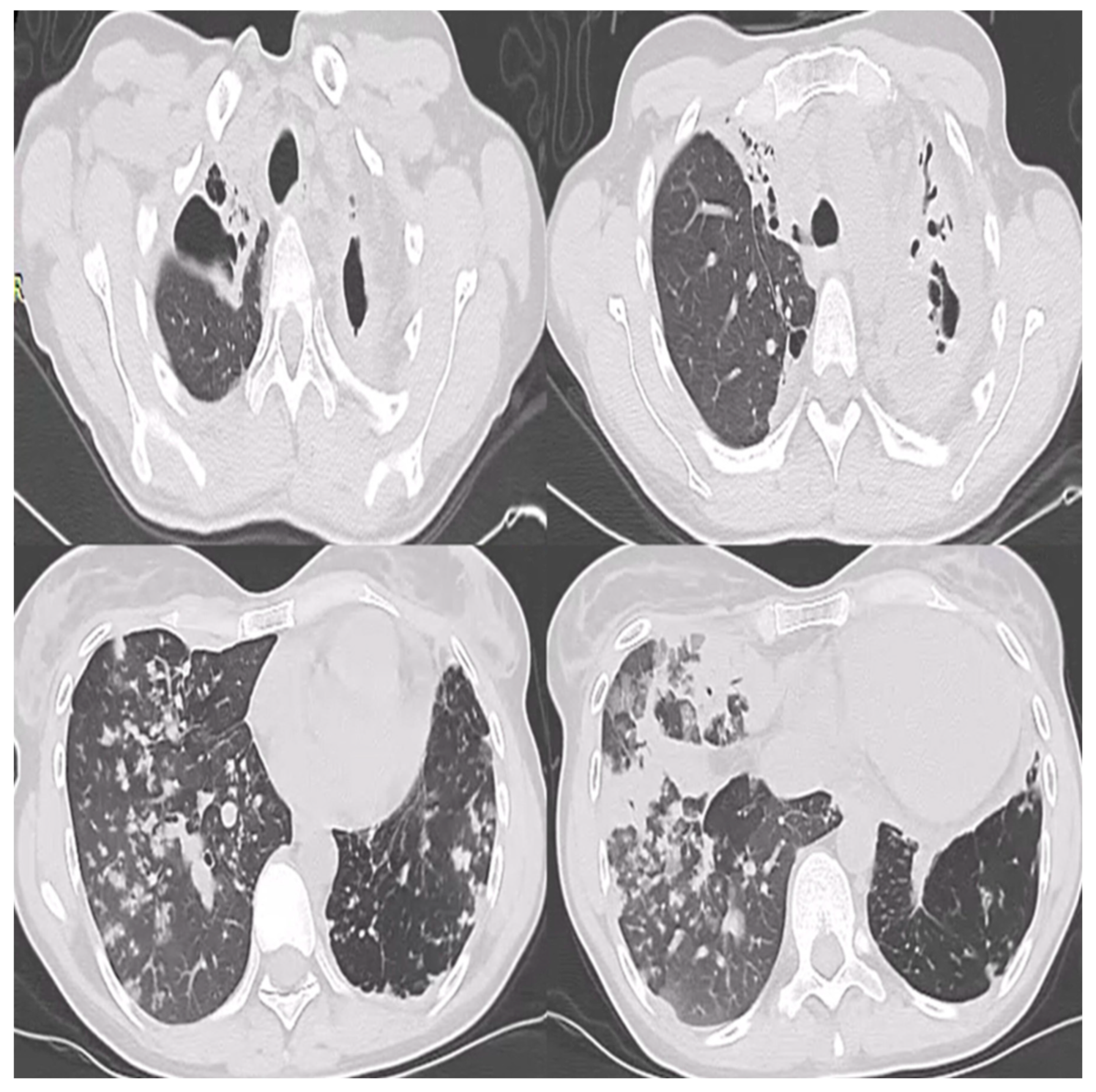

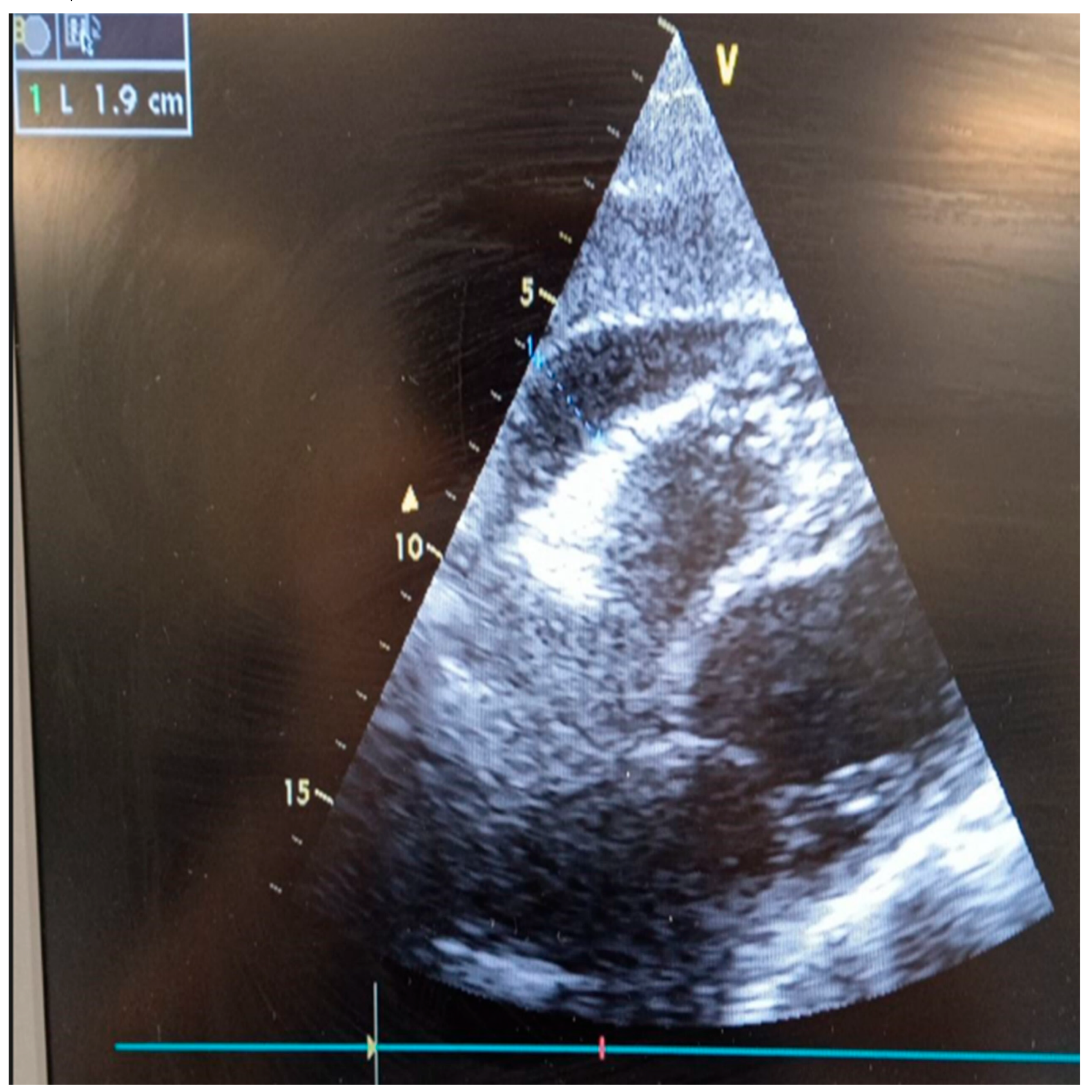

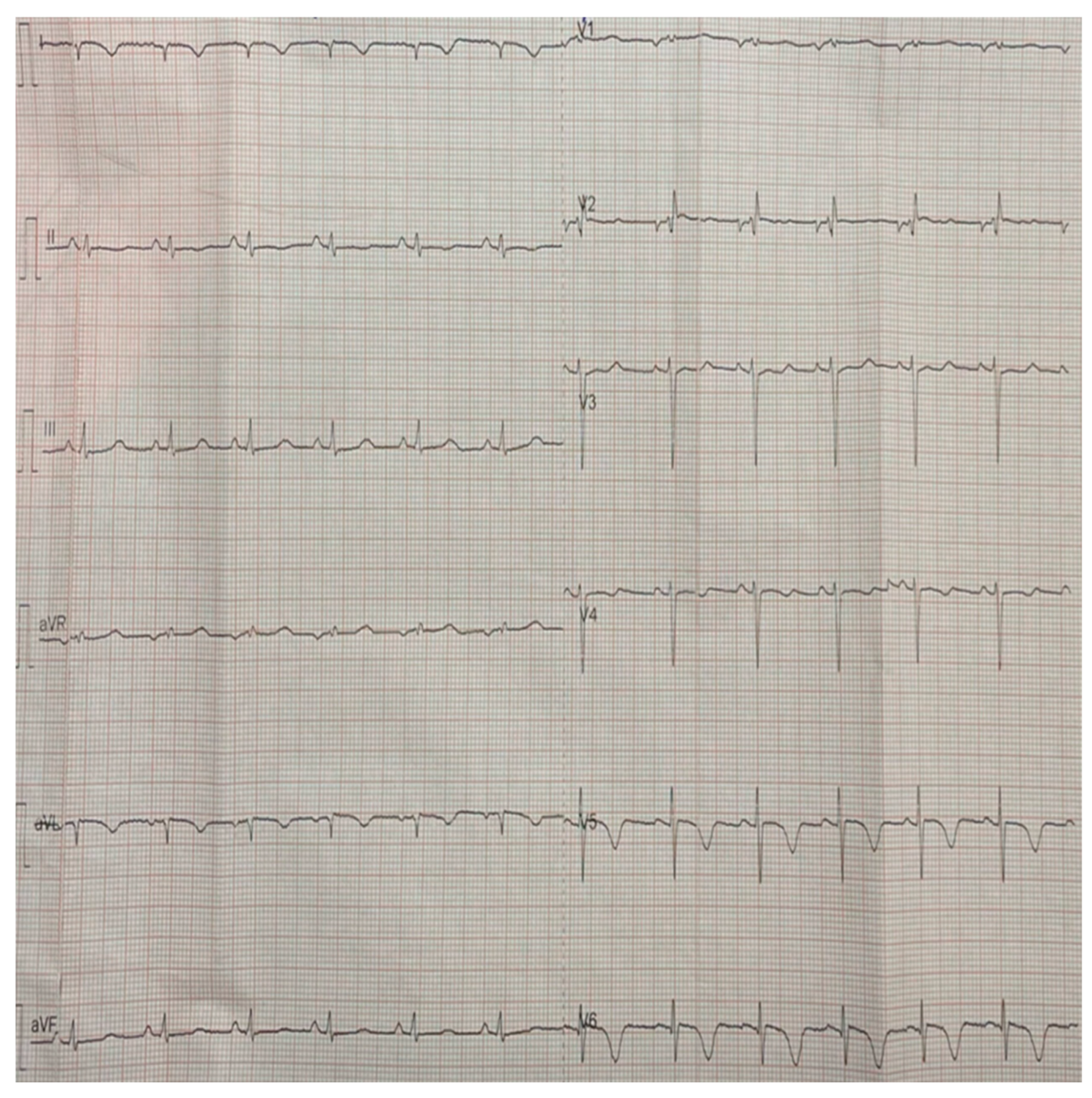

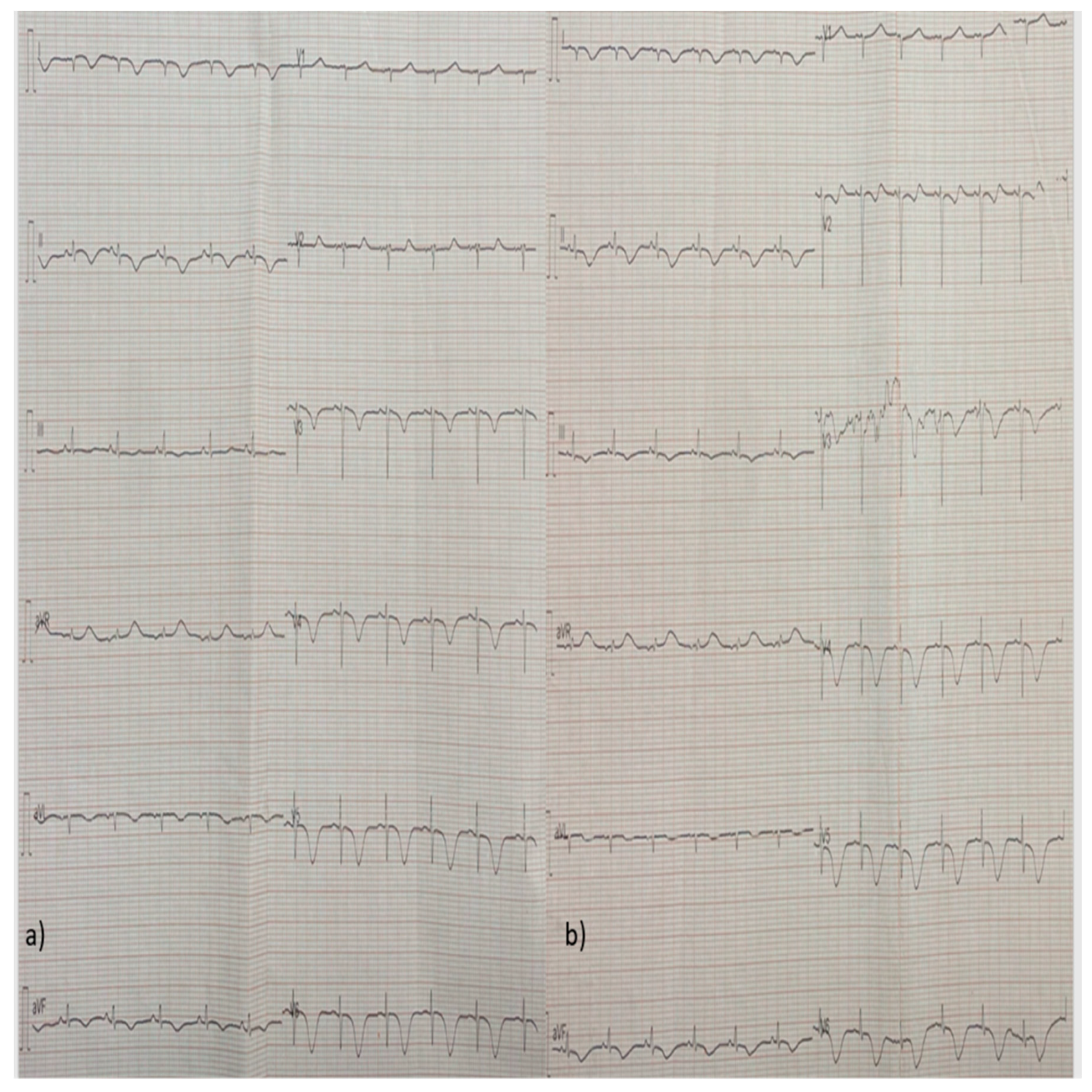

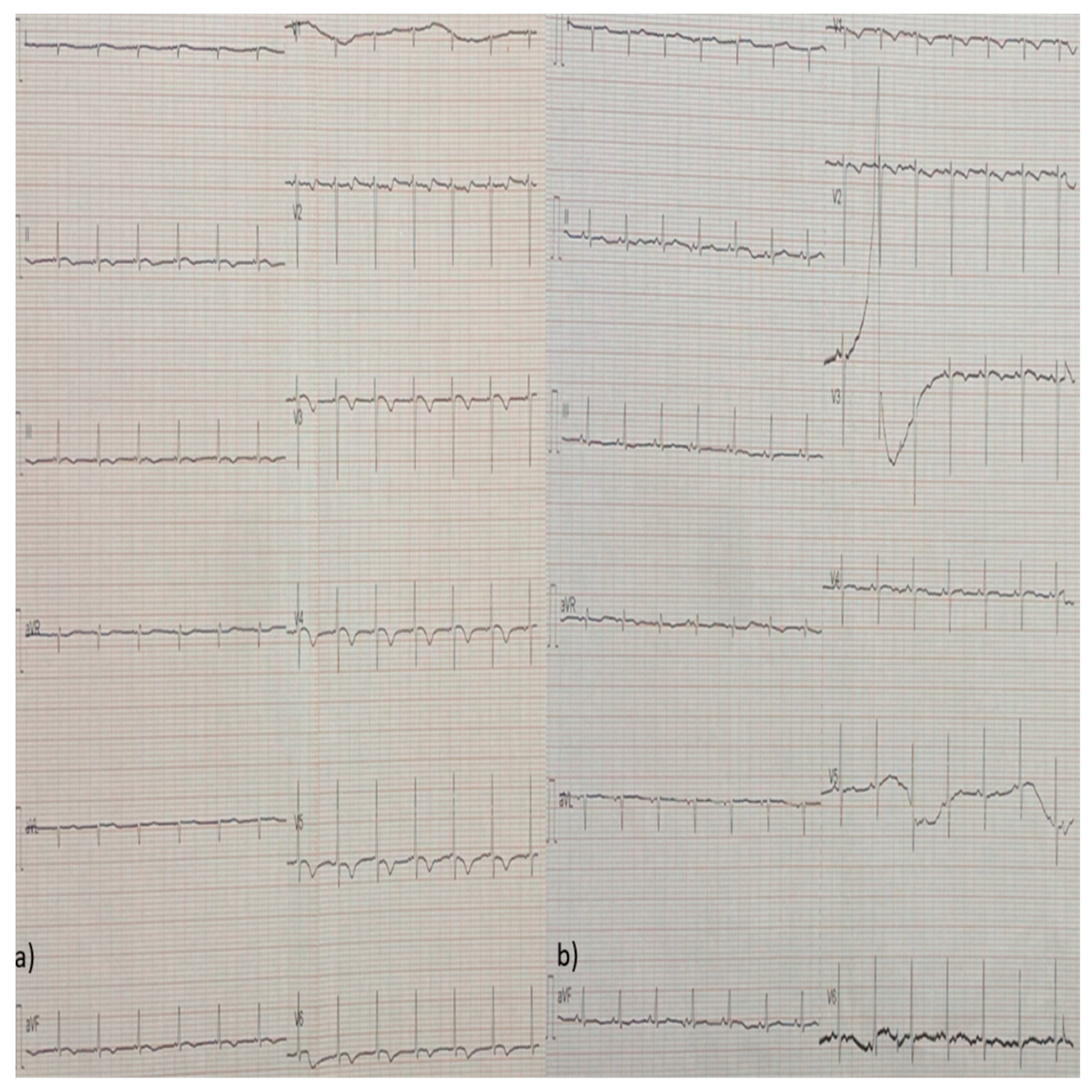

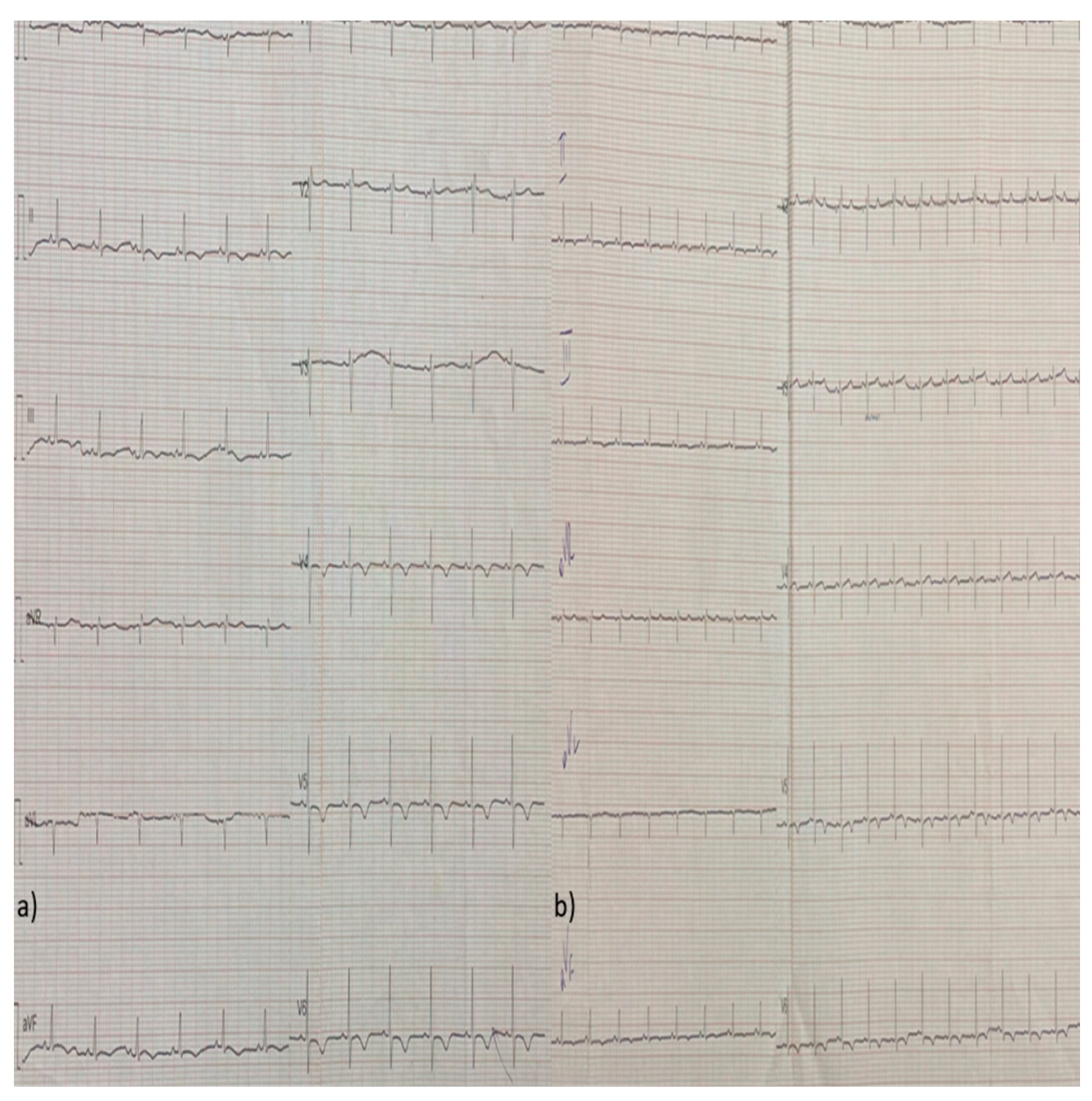

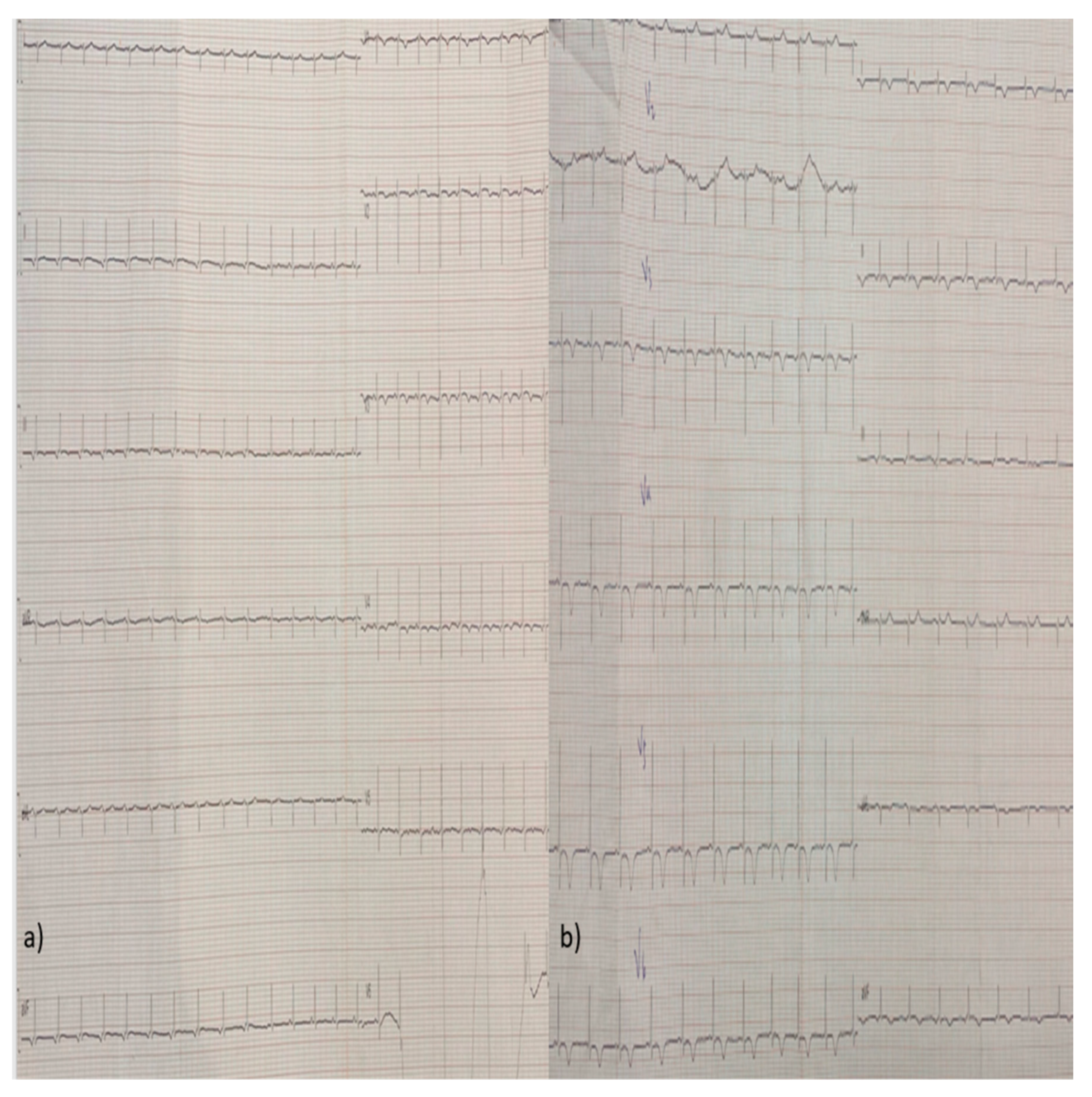

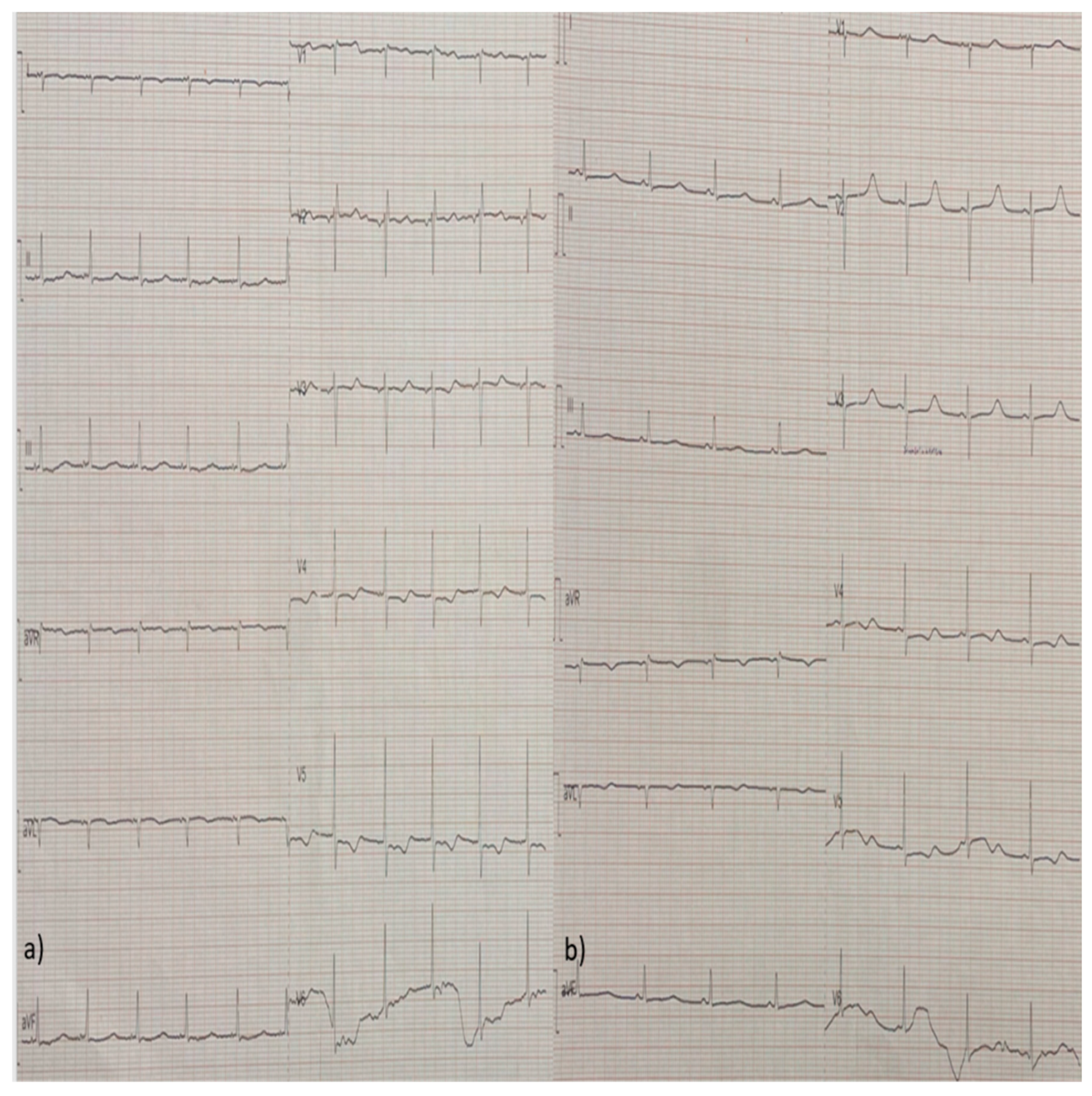

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: Module 4: treatment - drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, 2022 update [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK588564/.

- Conradie, F.; Bagdasaryan. T.R.; Borisov, S.; Howell, P.; Mikiashvili, L.; Ngubane, N., Samoilova, A.; Skornykova. S.; Tudor, E.; et al. Bedaquiline-Pretomanid-Linezolid Regimens for Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387(9):810-823. [CrossRef]

- Cury, R.C.; Budoff, M.; Taylor, A.J. Coronary CT angiography versus standard of care for assessment of chest pain in the emergency department. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2013, 7(2):79-82. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinides, S.V.; Meyer, G.; Becattini, C.; Bueno, H.; Geersing, G.J.; Harjola, V.P.; Huisman, M.V.; Humbert, M.; Jennings, C.S.; et al. The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Respir J. 2019, 54(3):1901647. [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; et al. ESC/ERS Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43(38):3618-3731. [CrossRef]

- Teboul, J.L.; Saugel, B.; Cecconi, M.; De Backer, D.; Hofer, C.K.; Monnet, X.; Perel, A.; Pinsky, M.R.; Reuter, D.A.; et al. Less invasive hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42(9):1350-9. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shlofmitz, E.; Khalid, N.; Bernardo, N.L.; Ben-Dor, I.; Weintraub, W.S.; Waksman, R. Right Heart Catheterization-Related Complications: A Review of the Literature and Best Practices. Cardiol Rev. 2020, 28(1):36-41. [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, E.; Moslehi, J.J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Myocarditis: A Review. JAMA. 2023, 329(13):1098-1113. [CrossRef]

- López-López, J.P.; Posada-Martínez, E.L.; Saldarriaga, C.; Wyss, F.; Ponte-Negretti, C.I.; Alexander, B.; Miranda-Arboleda, A.F.; Martínez-Sellés, M.; Baranchuk, A. Neglected Tropical Diseases, Other Infectious Diseases Affecting the Heart (the NET‐Heart Project). Tuberculosis and the Heart. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021, 10(7):e019435. [CrossRef]

- Michira, B.N.; Alkizim, F.O.; Matheka, D.M. Patterns and clinical manifestations of tuberculous myocarditis: a systematic review of cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2015, 21:118. [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, E.; Frigerio, M.; Adler, E.D.; Basso, C.; Birnie, D.H.; Brambatti, M.; Friedrich, M.G.; Klingel, K.; Lehtonen, J.; et al. Management of Acute Myocarditis and Chronic Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy: An Expert Consensus Document. Circ Heart Fail. 2020, 13(11):e007405. [CrossRef]

- Lampejo, T.; Durkin, S.M.; Bhatt, N.; Guttmann, O. Acute myocarditis: aetiology, diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2021, 21(5):e505-e510. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.S.; Cooper, L.T.; Kerneis, M.;Funck-Brentano, C.; Silvain, J.; Brechot, N.; Hekimian, G.; Ammirati, E.; M’Barek, B.B.; et al. Systematic analysis of drug-associated myocarditis reported in the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database. Nat Commun. 2022, 13: 25.

- Sagar, S.; Liu, P.P.; Cooper, L.T. Jr. Myocarditis. Lancet. 2012, 379(9817):738-47. [CrossRef]

- Seree-Aphinan, C.; Assanangkornchai, N.; Nilmoje, T. Prolonged Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support In a Patient with Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms Syndrome-associated Fulminant Myocarditis - A Case Report and Literature Review. Heart Int. 2020, 14(2):112-117. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.S.; Fradley, M.G.; Cohen, J.V.; Nohria, A.; Reynolds, K.L.; Heinzerling, L.M.; Sullivan, R.J.; Damrongwatanasuk, R.; Chen, C.L.; et al. Myocarditis in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018, 71(16):1755-1764. [CrossRef]

- Ronaldson, K.J.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Taylor, A.J.; Topliss, D.J.; McNeil, J.J. Clinical course and analysis of ten fatal cases of clozapine-induced myocarditis and comparison with 66 surviving cases. Schizophr Res. 2011, 128(1-3):161-5. [CrossRef]

- Uhara, H.; Saiki, M.; Kawachi, S.; Ashida, A,; Oguchi, S.; Okuyama, R. Clinical course of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome treated without systemic corticosteroids. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013, 27(6):722-6. [CrossRef]

- Gils, T.; Lynen, L.; de Jong, B.C.; Van Deun, A.; Decroo, T. Pretomanid for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022, 28(1):31-42. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).