Standard of care for advanced Prostate Cancer (PCa) consists of Androgen Deprivation Therapy (ADT) and the use of ever more effective therapies targeting the Androgen Receptor (AR) under different mechanisms (rev in [

1]). Unfortunately, these treatments ultimately fail due to various PCa adaptation pathways [

2] resulting in the incurable phase of the disease: metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). One of the most common mechanisms is the ability to integrate AR signals with ever diminishing residual testosterone, with the frequent participation of YAP (the final transducer of the Hippo pathway) as AR co-activator (rev in [

3]).

The Hippo pathway responds to a variety of signals, including cell-cell contact, mechanotransduction, and apico-basal polarity [

4,

5]. When the Hippo pathway is activated, kinases MST1/2 and LATS1/2 phosphorylate and inactivate YAP and TAZ. YAP and TAZ are transcriptional co-activators but lack DNA binding activity. They also appear to lack typical NLS and NES signals [

6,

7] (although this was recently argued in [

8]) and were believed to shuttle via interaction with their transcriptional partners or association with s14-3-3 [

9] or by the mere cell’s mechanical deformation [

10], although a role for YAP post-translation modification has also been proposed [

11,

12]. Upon phosphorylation by MST and LATS kinases, they are sequestered in the cytoplasm, ubiquitylated by the B-TrCP ubiquitin ligase, and marked for degradation by the proteasome. YAP/TAZ are usually inhibited by the cell-cell contact in normal tissues [

4]. Over-activation of YAP/TAZ through aberrant regulation of Hippo has been noted in many types of tumors and associated with the acquisition of malignant traits, including resistance to anticancer therapies, maintenance of cancer stem cells, distant metastasis [

4], and in prostates, Androgen-Independent (AI) adenocarcinoma progression [

13,

14]. When the Hippo core kinases are “off,” YAP/TAZ translocate into the nucleus, bind to TEAD1-4, and activate the transcription of downstream target genes, leading to multiple oncogenic activities, including loss of contact inhibition, cell proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and resistance to apoptosis. In PCa, YAP has been identified as a binding partner of AR and colocalized with AR in an androgen-dependent (AD) manner in and in an AI manner in CRPC [

13]. YAP was also found to be upregulated in LNCaP-C42 cells and, when expressed ectopically in LNCaP, activated AR signaling and conferred castration resistance, motility and invasion (rev. in [

3]). Knockdown of YAP greatly reduced the rates of migration and invasion of LNCaP, and YAP activated AR signaling was sufficient to promote LNCaP cells from an AS to an AI state in vitro, and castration resistance in vivo [

15]. It also was recently determined that ERG (and the common

TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangement) activates the transcriptional program regulated by YAP1, and that prostate-specific activation of either ERG or YAP1 in mice induces similar transcriptional changes and results in age-related prostate tumors [

16].

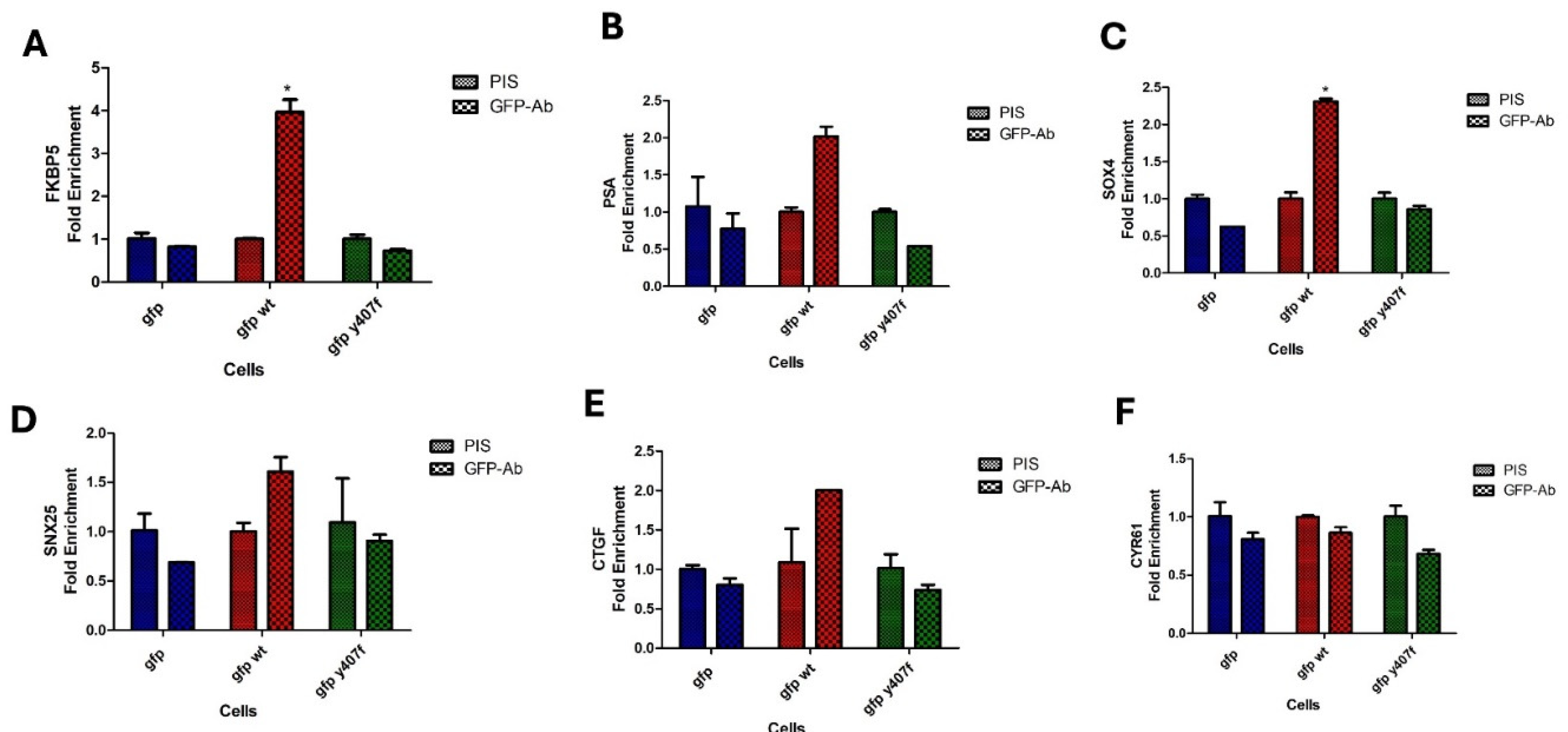

However, It has remained unclear what are the activators of the Hippo/YAP in PCa, but we have recently shown preliminary results that TLK1 has an important role in this via activation and induced stabilization, or possibly nuclear relocalization, via phosphorylation by Nek1 at YAP-Y407 [

17,

18]. We are now solidifying this work by showing that: 1) The phosphorylation of Y407 is critical for YAP retention/partition in the nuclei, and that J54 (TLK1i) reverses this along with YAP407 dephosphorylation. 2) That the enhanced degradation of (cytoplasmic) YAP is increased by J54 even when treatment with Enzalutamide (ENZ) tends to lead to its accumulation. 3) That the basis for all these effects, including YAP nuclear retention, can be explained by the stronger association of pYAP-Y407 with its transcriptional co-activators, AR and TEAD1. 4) That ChIP for GFP-YAP-wt, but much less for the GFP-YAP-Y407F mutant, at promoters of typical ARE- and TEAD1-driven genes are readily showing occupancy but becomes displaced after treatment with J54. 5) In the VCaP model, driven by the

TMPRSS2-ERG oncogenic translocation, xenografts initially respond well to the combination Enzalutamide (ENZ) and J54 (TLKi) but ultimately about 50% of the tumors relapse, despite the fact that J54 is still capable of suppressing pNek1-T141, its target, pYAP-Y407, and some of its target gene products.

Materials and Methods

- 1.

Cell Culture products. RPMI-1640 medium was acquired from Thermofisher. ENZ was acquired from BioSci Inc, J54 was synthesized by our group as described in the STAR Methods of [34]. We, however, also purchased some quantity from MedKoo Biosciences (J-3-54).

-

2.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: mouse anti-YAP (dilution- 1:1000 in 5% Milk+TBST, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SCBT, Dallas, TX, USA, cat# sc101199), rabbit anti-phospho-YAP-Y407 (custom generated by Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), mouse anti-NEK1 (1:1000 in TBST, SCBT, cat# sc 398813, Dallas, TX, USA), rabbit anti-phospho-NEK1 pT141 (lab-generated by Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), anti-Hu CD274 (PD-L1, B7-H1) (1:1000 in TBST, cat# 14-5983-82, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-ORC2 (1:1000 in TBST, cat# PA5-67313, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-pSTAT1 (1:1000 in TBST, cat# 9167 CST Danvers, MA), anti-pIRF3 (1:1000 in TBST, cat# 4302 CST Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-TEAD1 (1:1000 in TBST, cat# 12292 CST Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-pSTING (1:1000 in TBST, cat# 19781 CST Danvers, MA), rabbit anti-STING (1:1000 in TBST, cat# 80231 CST Danvers, MA), anti-GAPDH (1:1300 in 5%BSA+TBST, ca# 2118S (14C10), CST), anti-GFP (cat# MA5-15256 (GF28R), Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), rabbit anti-MMP10 (1:1000 in TBST, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, cat# ab38930), rabbit anti-MMP9 (1:1000 in TBST, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, cat# ab283575), and rabbit anti-actin (1:1000 in TBST, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, cat# ab1801). Secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies, anti-rabbit (cat# 7074S, CST) and anti-mouse (cat# 7076S, CST) were used to probe immunoblots.

-

1.

GFP localization. GP-YAP-expressing cells were seeded at a density of 20,000/cm2 in a T25 and after treatment with fresh medium containing J54 (10 µM) were immediately monitored during a time course in the Incucyte.

-

2.

ChIP and coIP. These were carried out as described in [

19].

-

3.

Animal Studies

All animals used in this study received humane care based on the recommendations set by the American Veterinary Medical Association, and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of LSU Health Sciences Center at Shreveport approved all the test protocols. Immune-deficient NOD SCID mice (Charles River) were used in this research to host human VCaP tumors. The mice were subcutaneously implanted with 0.5 × 106 human PCa VCaP-Luc cells suspended in Matrigel into each lower back flank. Following establishing tumor sizes less than 120 mm3, the mice harboring the tumors were randomly assigned to three groups for treatment. Enzalutamide (Enz, 10 mg/kg), an androgen receptor (AR) inhibitor and a combination of Enz and TLK1-NEK1 axis inhibitor J54 (10 mg/kg each) were administered to the mice as treatments. One group received the combination treatment orally (OR). J54 and Enz were administered every two weeks, dissolved in 200 sterile saline containing 10% Polysorbate-80—PS-80. Our prior work served as the basis for the dosage for J54. A caliper was used every other day to measure the tumor diameters. Thirteen biweekly medication cycles totaling forty-three days were spent on the inhibitor therapy. The tumor-bearing mice were observed every other day and were euthanized if their body weight appeared to have dropped by more than 20%, if they showed signs of poor health or stomach palpitations brought on by cancer metastases or prostate tumor development, or if they were too unwell to eat or drink. After the experiment, the mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation, and the tumors were removed to perform tissue Western blots.

Western Blots

-

a.

Tissue Western Blot: Western blots were performed from randomly selected tumors excised from the different treatment groups, including control (PBS), ENZ, J54 and the combination of the VCaP-Luc grafted NOD SCID mice. The frozen tumor tissues were disrupted with the Bioruptor® Plus sonication device (Diagenode; Cat. No. B01020001), homogenized, and lysed in the ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Cat. No. SC-24948). The samples were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 mins in the refrigerated setting. The supernatant was collected, transferred into fresh 1.5 ml microfuge tubes, flash-frozen, and stored at -800C until further use. The total protein concentration was measured using a Pierce™ BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific; Cat. No. 23225) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard control. An equal loading amount of 15 µg was calculated for each protein sample. The sample supernatant was denatured with 1X Laemmli Buffer for 10 mins at 950C and separated using 10% PAGE with Mini PROTEAN TGX protein gel (BioRad; Cat. No. 4568084) at 100 volts for 120 mins. The proteins were transferred to the Immun-Blot PVDF membrane (BioRad; Cat. No. 1620177) using a Mini Trans-Blot Cell (BioRad; Cat. No. 1703930) at 100 volts for 150-180 mins on ice. The membrane was blocked with 5% Non-fat dry milk (Cell Signaling Technology; Cat. No. 9999S) in 1X Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature. Following blocking, the membrane was washed once with 1X TBST and incubated with primary antibodies in 5% BSA in 1X TBST overnight at 40C with gentle rocking. The next day, after washing four times with 1X TBST, the membrane was incubated with horse anti-rabbit antibody 1:2000 dilution) labeled with horseradish peroxidase in 5% BSA in 1X TBST for 1-1.5 hours at room temperature. After incubation, the membrane was washed four times with 1X TBST, and the reactive bands were detected using Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific; Cat. No. 32106) on ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (BioRad; Cat. No. 12003154).

-

b.

Cell Western Blot: The western blot for PC-3 cells was performed as described above but with minor modifications. Briefly, 3*106 LNCaP expressing GFP-YAP or VCaP cells (control and drug-treated) were collected, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and lyzed with RIPA lysis buffer system. The lysate was vortexed and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min to remove cell debris. The total protein was estimated, and 30 μg of the cell lysate was loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel. The separated proteins were transferred to the membrane using a wet transfer apparatus. The complete transfer was ensured by checking the membrane for uniform background staining. The membrane was then incubated in a blocking solution (e.g., 5% non-fat milk in TBST) for 1 h at room temperature to block non-specific binding sites, followed by primary antibody.

Statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad prism 9 and Microsoft excel software. Data quantifications are expressed as mean± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated by 2-tailed Student’s t-test when comparing the mean between two groups, or by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis when comparing more than two groups. p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

The TLK1>Nek1 Nexus Is a Key Player of YAP Stability

We previously showed that activation of the TLK1>Nek1 nexus results in increased expression of YAP, largely via leading to the accumulation of this typically rapidly degraded protein, and that Nek1-KO cells have intrinsically very low levels of YAP [

17]. We subsequently showed that the Y407F mutant is expressed in LNCaP and Hek293 cells as a highly unstable protein, constitutively displaying an array of cleaved smaller species, and reduced transcriptional activity [

18]. However, it is unknown if the majority of CRPC progression journeys through overactivation of YAP [

20], and if so, what are the key regulators of the Hippo/YAP axis in PCa.

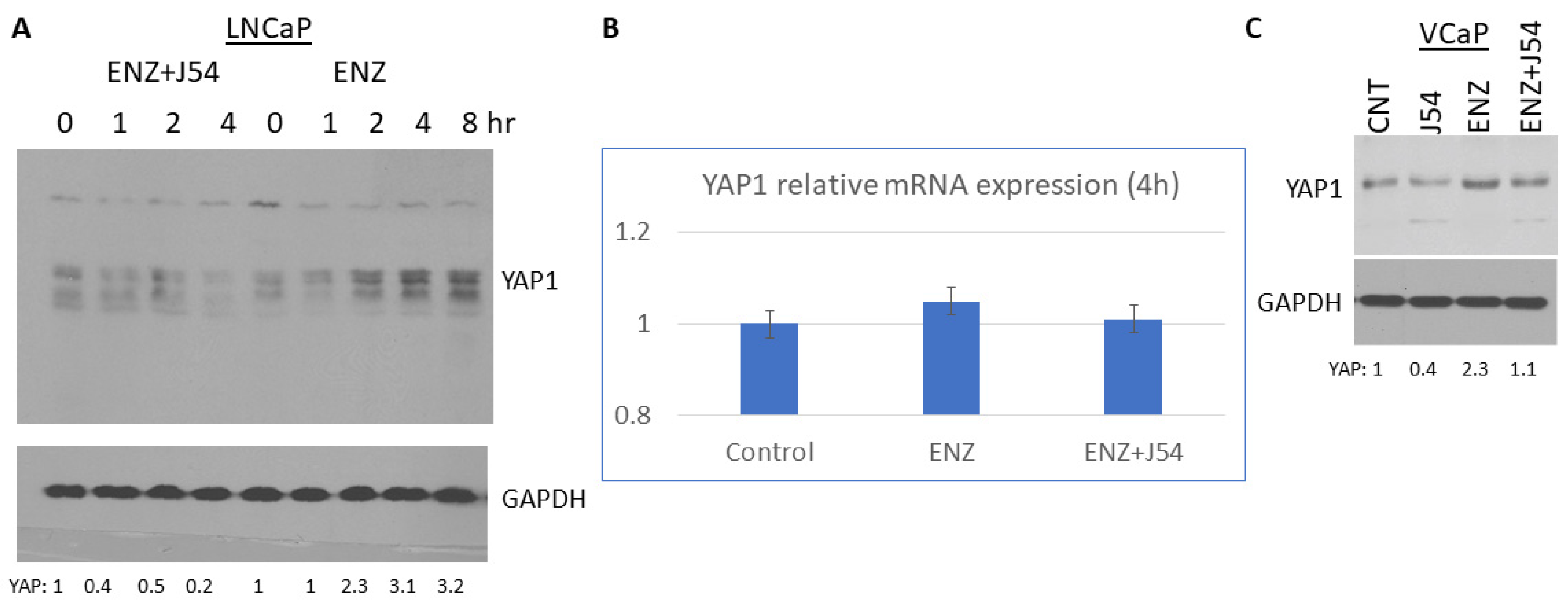

Relatively few PCa cells models exist to monitor the adaptive changes that occur during progression from AS to AI growth, with the predominant clearly being the LNCaP cells. With these cells, it was demonstrated the critical importance of YAP1 and its integration of AR and TEAD signals reprogramming in their transition to ENZ resistance [

21], which was also correlated to functional analyses revealing that YAP1 positively regulates numerous genes related to cancer stemness and lipid metabolism. Moreover, Gene signatures of COUP-TFII and YAP1 from different datasets showed strong correlation in a large cohort of mCRPC datasets from cBioPortal [

21]. However, in that study, the expression of YAP1 was analyzed in LNCaP clones derived for their resistance to ENZ (EnzaR) and not by following early stages of adaptation to ARSI exposure. In fact, we have recently shown that YAP1 increased expression following ADT is largely post-transcriptional, and due to the rapid compensatory activation of the mTOR>TLK1B>NEK1 kinase cascade, ending in the phosphorylation of YAP1-Y407 that transcriptionally activates as well as prominently stabilizes this key co-activator [

18,

22]. We now show that this is in fact a rapid event following exposure of LNCaP cells to ENZ, and it is possibly an important survival mechanism to integrate any residual AR signals (or other YAP1 signatures) that lead to their final adaptation to ARSI exposure. We show that the rapid increase in YAP1 accumulation after can be completely blocked by concomitant treatment with J54 (

Figure 1) without appreciable changes of the mRNA, which was thus attributed to YAP1 protein stabilization [

18,

22], although the newly uncovered Nek1>YAP regulation is underreported in recent reviews [

23]. Nonetheless, we established that activation of TLK1 by BIC and the resulting increase in pNek1-T141 and transcriptional activity [

18] can be completely suppressed with J54 (TLKi) [

24] as a direct regulator of YAP stability. This could be demonstrated also in VCaP cells treated for 4h as shown (

Figure 1C) that represent another rare PCa model that readily converts in culture and in xenografts from AD to AI following ARSI treatment.

While

Figure 1 can invoke possible alternative explanations for the progressive difference in YAP levels in ENZ vs ENZ+J54 treated cells over time, this result is independently reinforced by our prior report that GFP-tagged versions of YAP showed an increase pattern of cleaved products after treatment with J54 for the wt version. Whereas the Y407F mutant showed constitutively high instability and degradation products that were not enhanced after treatment with J54 (as the key Nek1 phosphorylation site was abrogated) [

18].

Evidence That the TLK1>Nek1>pYAP-Y407 Is Critically Important for Its Nuclear Localization/Retention

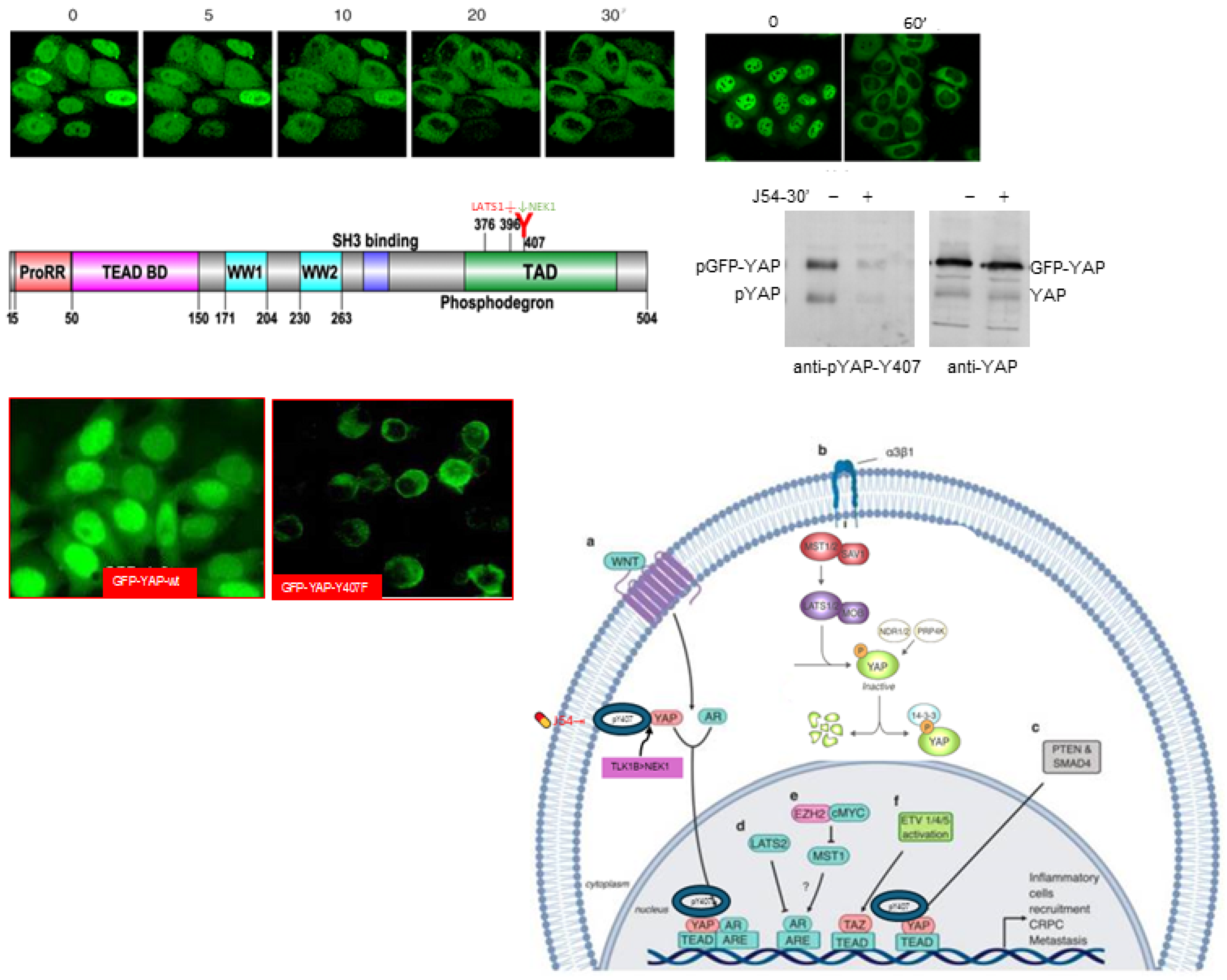

We previously reported that GFP-YAP-wt appeared to be preferentially localized to the nuclei, whereas the Y407F mutant seemed largely excluded from the nuclear compartment [

18]. However, that was only a suggestion, as the cells had not been sorted for GFP expression and rather just selected for G418 resistance. Moreover, we had not tested the dependence on the TLK1>Nek1 nexus by challenging the cultures with J54.

We now show exactly that effect in

Figure 2, which demonstrates that treatment with J54 result in rapid dephosphorylation of pYAP-Y407 (GFP-tagged or endogenous protein) and concomintant relocalization from nuclei to the cytoplasm. We also confirmed more rigorously that GFP-YAP-wt is mostly nuclear, whereas the Y40&F mutant is largely excluded from the nuclei. A working model is also shown in

Figure 2 (adapted from [

3]) where we propose that the productive association of pYAP-Y407 with transcriptional co-activators lads to its import and/or retention in the nuclei and at promoters of its target genes, whereas J54-mediated dephosphorylation leads to its default, LATS-mediated phosphorylation at S127 and S396 and subsequent nuclear export via shutlling with s14-3-3 proteins and eventually its rapid degradation.

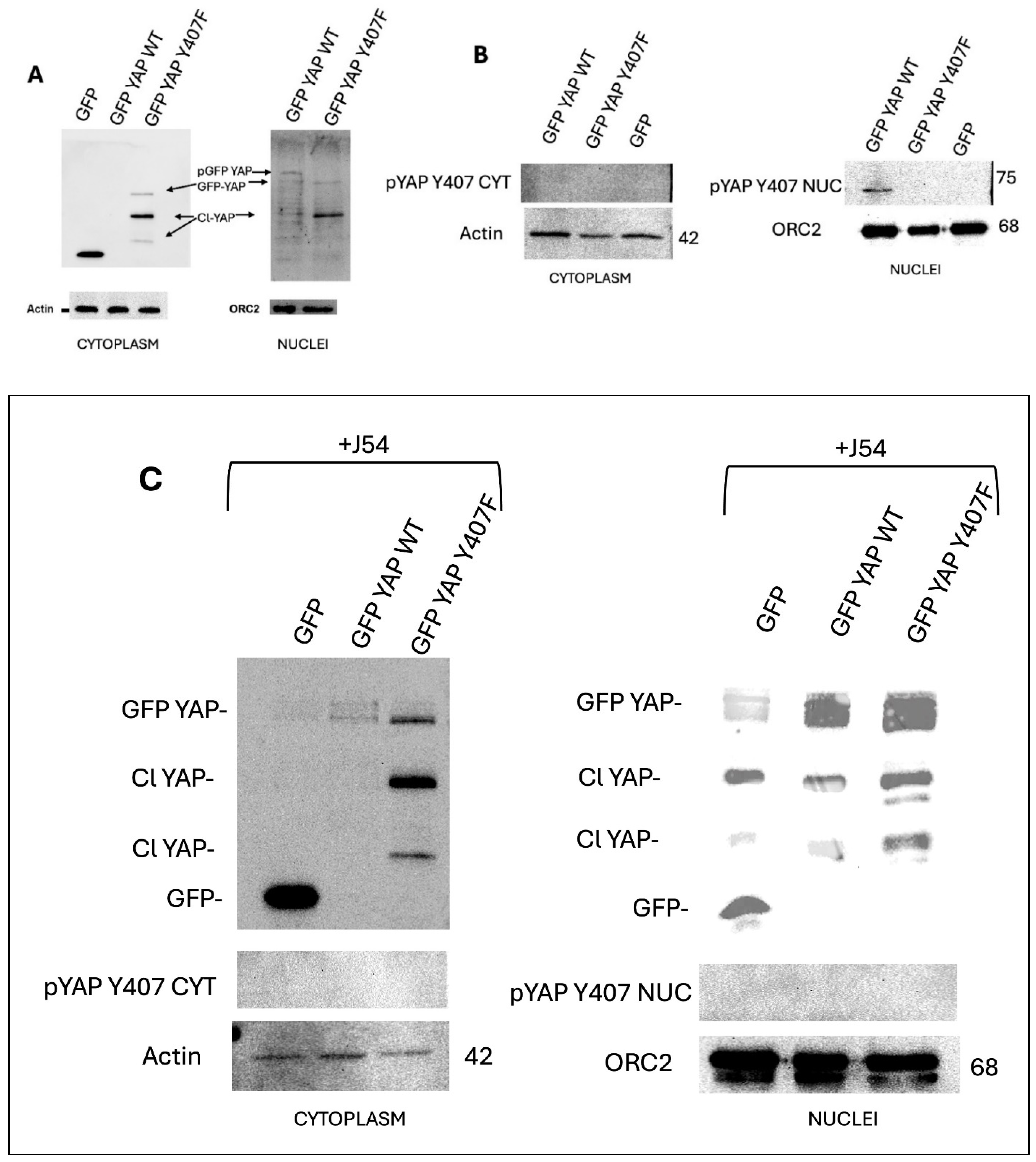

TLK1>Nek1 Nexus Is Actively Involved in the Regulation of the Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling of YAP

The subcellular location of YAP is pertinent for its downstream signaling and several studies have confirmed that active YAP must be essentially nuclear to facilitate its transcriptional programs [

24,

25]. We previously reported that LNCaP cells overexpressing GFP-YAP-WT and not Y407F mutant can convert from AS to AI-growth. We now provide evidence to show that this transformation is driven by the complete relocation of YAP to the nucleus after Nek1-mediated phosphorylation (

Figure 3A) and that the Y407F mutant’s high instability and degradation in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm could explain its inability to transform cells into AI-growth. This property highlights the need for spatiotemporal regulation of YAP activity via nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. In response to the numerous cues that signal through the Hippo pathway, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of YAP by its core kinases has been reported to regulate its cytoplasmic and nuclear movements respectively [

26]. Recent report of the inolvement of Src-family kinases in the shuttling process by [

27] suggests the involvement of other YAP nucleocytoplasmic regulators independent of Hippo core kinases. We now report that Y407 phosphorylation of YAP is sufficient for relocating active YAP into the nucleus (

Figure 3B), as evident by the YAP-Y407 band seen only in the GFP-YAP-WT, where it can stably bind to DNA-binding partners to initiate the transcription of target genes. Our results became more interesting when we observed the high instability and degradative ability of GFP-YAP-WT like those of the non-phosphorylatable Y407F mutant when the cells were treated with J54 (TLKi) for 24 hrs (

Figure 3C). Remarkably, J54 treatment eliminates any trace of the active YAP-Y407 from the nucleus, mediates the degradation of nuclear YAP and most importantly, orchestrates the movement of YAP to the cytoplasm where in time it becomes inactive, associates with 14-3-3 protein and is targeted for degradation by the b-TrCP, the default of Hippo core kinase phosphorylation.

GFP-YAP-wt Partitions Largely to the Nuclei Whereas the Y407F Mutant to the Cytoplasm

A fractionation experiment to separate nuclei from cytoplasm, revealed that: 1) GFP-YAP-wt is essentially all nuclear (with a clearly slower mobility band, seen also in C, enriched in the nuclear fraction) and absent from cytoplasm (

Figure 3A). Whereas, the GFP-YAP-Y407 mutant distributes about 60:40 between cytoplasm and nuclei (note also the prominent degradation product (Cl-YAP we previously reported [

18] and its presence in both cytoplasm and nuclei). When we used the phopho-specific pY407 antiserum (

Figure 3B), the only signal seen was from the WB of the GFP-YAP-wt cells, nuclear fraction.

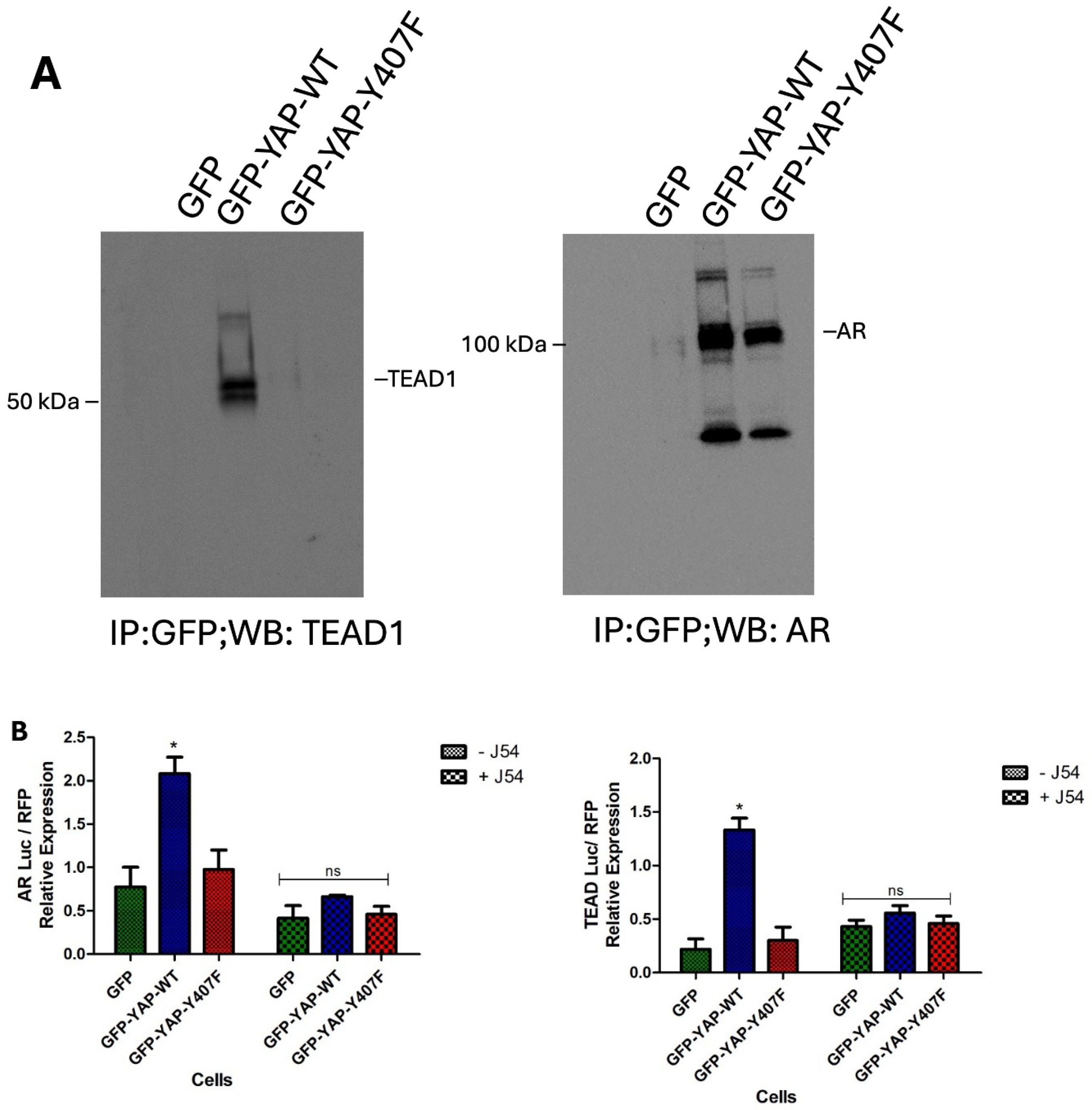

Y407 Phosphorylation of YAP Is Important for Its Nuclear Interaction with DNA-Binding Partners and Delivery of Transcriptional Outputs That Control CRPC Progression and ECM Invasiveness

YAP as a transcriptional coactivator lacks a DNA-binding domain and hence requires a DNA-binding transcription factor to modulate the expression of its target genes [

28]. In addition, its association with these binding partners has been suggested to be beneficial for its nuclear retention [

9]. Although YAP interacts with numerous DNA-binding transcription factors [

28,

29], TEAD family of proteins remains the most characterized binding partners of YAP. The interaction with TEAD is significant giving that a sizable proportion of the N-terminal of YAP is devoted to TEAD binding [

30], and the nature of this interaction is often described as pro-oncogenic [

31]. Specifically, in PCa, YAP has also been described to co-localize with AR in the androgen-dependent and AI manner to form protein complexes in the nuclei [

13]. We previously reported the transcriptional output of Y407 phosphorylation in an expression panel of EMT and AR target genes [

18]. To elucidate the importance of Y407 phosphorylation of YAP in converting upstream signaling to transcriptional outputs in LNCaP cells we carried out Co-immunoprecipitation with the GFP-YAP-WT and the Y407F mutant expressing cells. Our results revealed that wt-YAP interacts much more strongly with TEAD and AR compared to the mutant (

Figure 4A).

Moreover, using the transcriptional reporters of AR and YAP/TEAD (8xGTIIG-Lux) in a transient transfection experiment, we also confirmed that the transcriptional output of wt-YAP is significantly higher than that of the mutant following Nek1>YAP1 activation (

Figure 4B), which supports the upregulation of the AR target, and YAP/TEAD canonical genes. Interestingly, we observed that J54 treatment resulted in a significant reduction in the luciferase expression to a level comparable to the mutant when both AR and TEAD reporters are considered. This rightly connotes that J54, and by extension obliteration of Y407 phosphorylation, also interrupts YAP’s interaction with binding partners in addition to disrupting its stability. In [

18], we confirmed that Y407 phosphorylation is critical for EMT, we further investigated the implications of YAP’s stable association with binding partners on its tumor invasive properties using the incucyte cell migration assay. We observed that LNCaP cells (typically rather indolent) overexpressing YAP-wt had a high basement membrane (Matrigel) invasive ability (

Figure 4C) comparable to that of the highly metastatic PC3-PCa cells. This effect was reversed with J54 treatment of the cells, again depicting the ability of J54 to reverse metastatic properties of PCa.

We carried out an immunoblot to determine the expression of some of the known MMPs and found a higher expression of MMP9 and MMP10 (

Figure 4D) in the wt-YAP overexpressing cells which corresponds with increased YAP activation of EMT TFs which we have previously described in [

18].

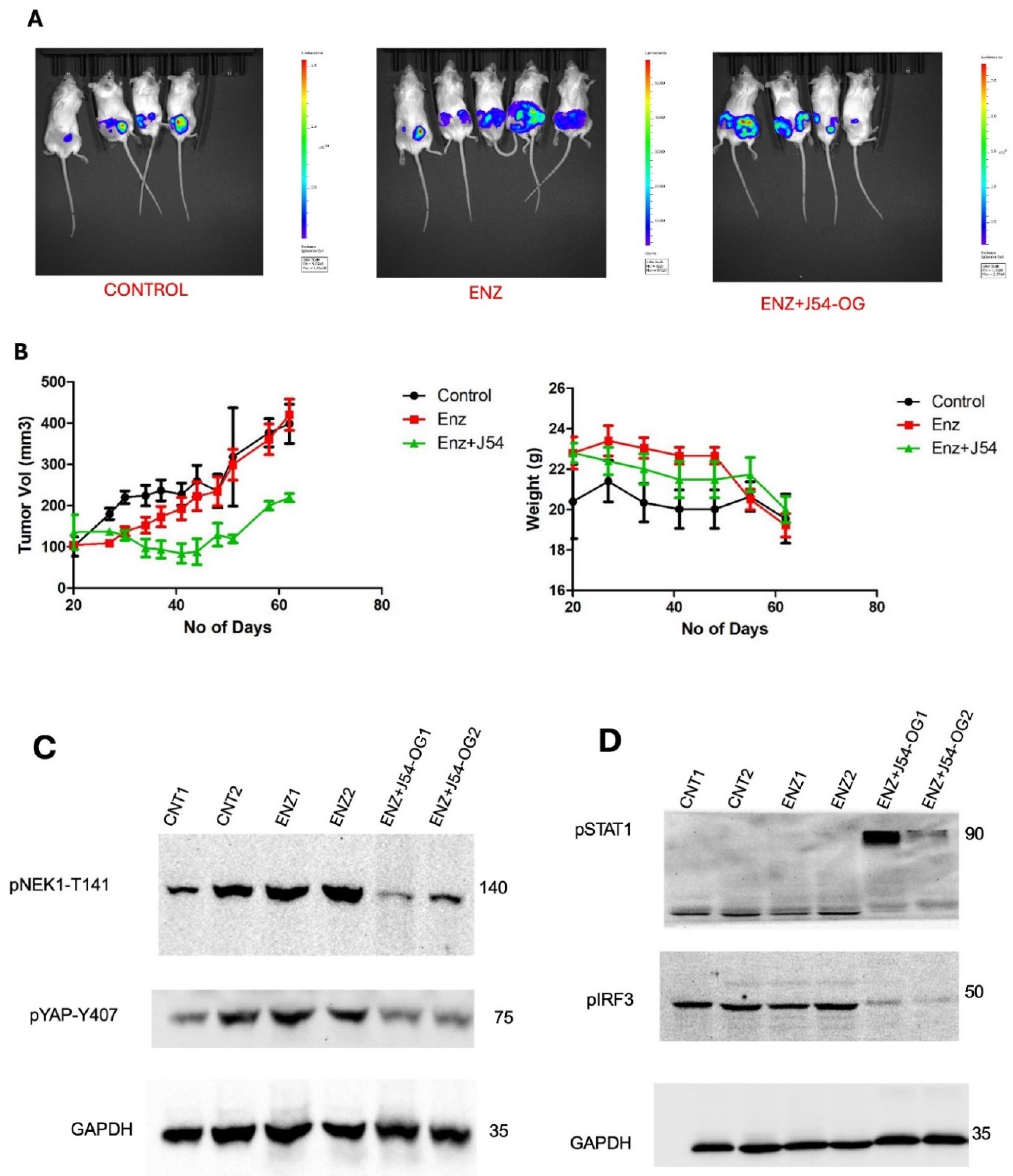

Treatment of VCaP Xenografted Mice with ENZ and J54 Shows Only Transient Tumor Regression Despite Prolonged Suppression of the TLK1>NEK1>YAP Axis

We previously reported that treatment of LNCaP xenografts with ARSI+J54 results in nearly complete, permanent regression of tumors [

24,

25]. The VCaP xenograft model, that also converts readily from AD to AI, initially responds well (with shrinkage of the tumors) to the combination Enzalutamide (ENZ) and J54 (TLKi) but ultimately in about 50% of the mice, the tumors slowly re-grow (

Figure 5A,B). This despite the fact that J54 is still capable of suppressing pNek1-T141 and its target, pYAP-Y407 [

18] (

Figure 5C), the active, nuclear form of the co-activator, and some of its target genes that encompass Immune Checkpoint regulators (

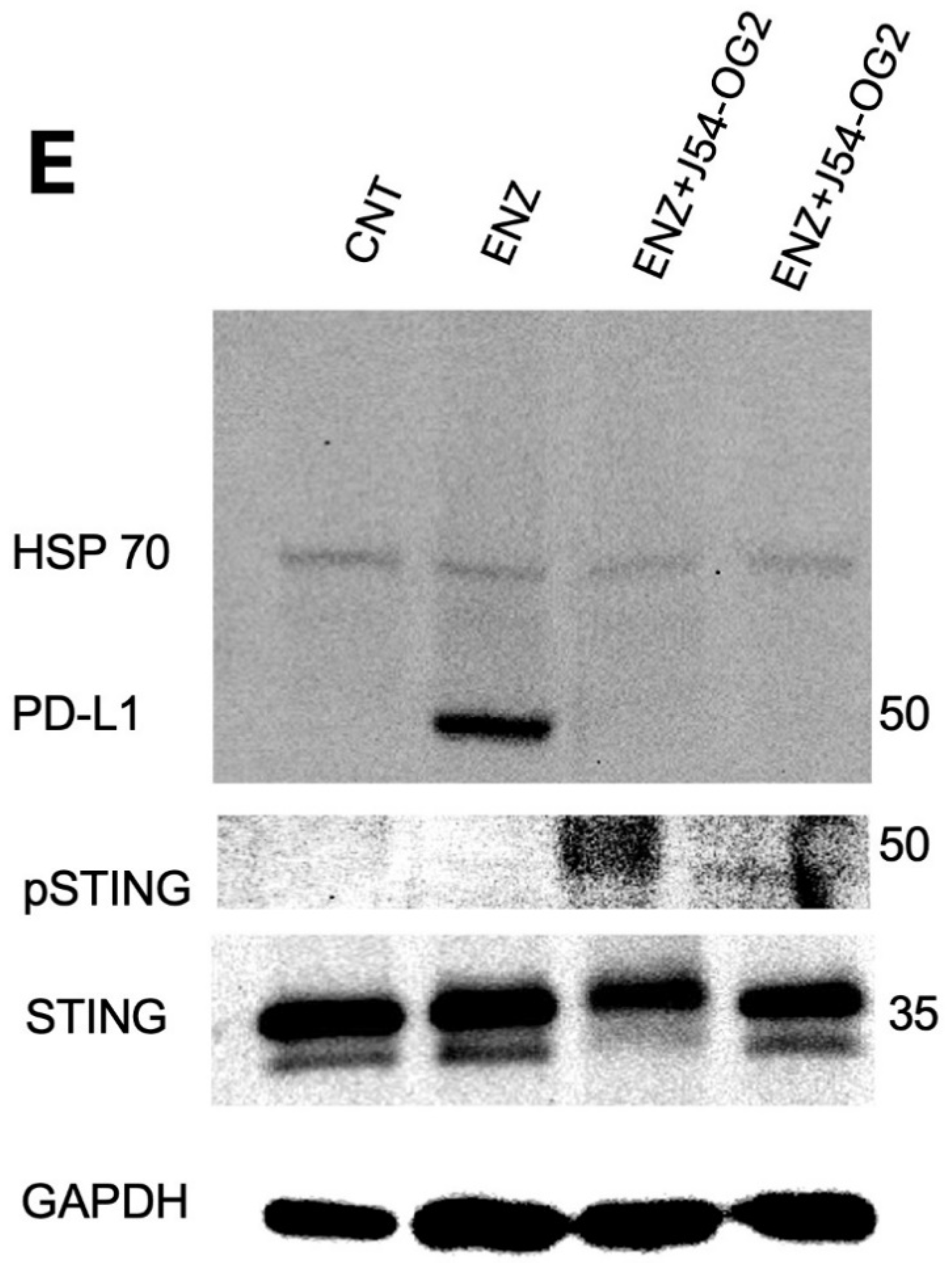

Figure 5D,E). We currently favor the hypothesis that the

TMPRSS2-ERG oncogenic translocation expressed in VCaP can implement a parallel AI (CRPC) conversion as the one mediated by the AR/YAP integration, with elevated expression of their target genes including EMT and androgen independence determinants [

18], but that the addition of J54 to curtail the TLK1>Nek1 axis may still act as a ICB [

26,

27] in an immunocompetent host/individual. In fact, an important distinction that characterizes YAP coopted regulation of cancer progression genes is its capacity to mediate YAP-Induced PD-L1 expression that drives immune evasion [

20,

25,

26]. This is clearly shown in

Figure 6E, which shows that prolonged treatment with ENZ results in a dramatic increase in PD-L1 expression, that can be fully suppressed by concomitant administration of J54. It is noteworthy that this is a sad outcome already reported for ENZ that may limit its prolonged use in patients [

27]. Concomitantly, pIRF3 in recidive VCaP xenografts was also suppressed with J54 (

Figure 6D), thus curtailing a key branch of the innate immunity through expression of INF-g that is also critical for PDL-1/2 expression and avoiding immune surveillance [

28]; while pSTAT1 was dramatically increased likely through activation of cGAS/STING from release of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA upon implementation of apoptosis [

29,

30,

31,

32]. This was confirmed by WB analysis of pSTING vs. pan-STING (

Figure 6E), an indication of the high rate of apoptotic turn-over in the tumors of mice concomitantly treated with J54. Note that in this experiment there is no J54 alone group, which in previous work we had already shown has negligible effect of the rate of tumor growth or the general health of the mice [

24,

33].

Discussion

YAP1 and its paralog TAZ are the final effectors of the Hippo signaling pathway, which is involved in regulating organ size through multiple cellular functions including cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis [

3,

23,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Hippo pathway responds to a variety of cellular cues, including cell-cell contact, mechanotransduction, and apico-basal polarity [

4,

5]. When the Hippo signaling is activated, kinases MST1/2 and LATS1/2 phosphorylate and inactivate YAP1 and TAZ. YAP1 and TAZ are transcriptional co-activators but lack DNA binding activity. Upon phosphorylation by MST and LATS kinases, they are sequestered in the cytoplasm, ubiquitylated by the b-TrCP ubiquitin ligase, and marked for degradation by the proteasome. YAP1/TAZ are usually inhibited by the cell-cell contact in normal tissues [

4]. Specifically, it should be noted that YAP1 is a generally unstable protein whose turnover rate is strongly regulated by multiple stabilizing [

40] or de-stabilizing phosphorylation events controlled by multiple kinases (see [

4,

15,

41] for some reviews). The best-known destabilizing event is by the Large Tumor Suppressor 1 and 2 (LATS1/2), the core kinases of Hippo signaling pathway that can phosphorylate YAP1 on Ser127 which creates a binding site for 14-3-3 protein. The binding of 14-3-3 to pYAP1-S127 leads to its cytoplasmic sequestration [

42,

43]. Sequential phosphorylation by LATS1/2 on YAP1 Ser397 primes it for further phosphorylation by Casein kinase 1 (CK1δ/ε) on Ser400 and Ser403 which creates a phosphodegron motif in the transcriptional activation domain (TAD) for β-TrCP/SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase mediated proteasomal degradation [

44]. It could be argued that the main regulation of YAP/TAZ is via its translocation from the ‘inactive’ cytoplasmic compartment where its is eventually degraded, to its final target genes in the nucleus, and much of this regulation occurs via phosphorylation of specific residues, e.g., [

45,

46,

47], and importantly, Tyrosines [

11,

45]. The phosphorylation of YAP1 by NEK1 on Y407 (

Figure 1A), which is located in the TAD, was a new finding by our lab and immediately correlated with its stabilization, since pharmacologic inhibition of the TLK1>NEK1 nexus with THD or J54 resulted in a dose and time-dependent degradation of YAP1 (

Figure 4B and [

17]). Thus, it is notable that over-activation of YAP1 can be directly suppressed via inhibition of the TLK1>NEK1 activation loop, for example with J54.

We now solidify these initial results by confirming that the phosphorylation of Y407-residue is critical for the nuclear shuttling or retention of YAP, likely by promoting its association with its transcriptional co-activators. This is vaguely reminiscent of the well-established role of pY-containing specific residue as an anchor for SH2-domain proteins [

48,

49]. The ultimate goals of this study are to identify a pathway for preventing CRPC progression via dampening the TLK1>Nek1>YAP-mediated conversion from AD to AI [

50]. We can at this point be confident that this is probably the case for PCa cases that pattern along the LNCaP cells models, but this may not be the case for the more complex situation when the common

TMPRSS2-ERG translocation is present, and almost certainly not for NEPC cases, wherein expression of YAP is actually reduced [

51] and probably inactive. However, the

TMPRSS2-ERG oncogenic translocation is known to activate/stabilize YAP [

52] and consequently driving expression of PD-L1 [

26], which is a critical component of the Immune checkpoint and a target for ICB intervention [

53]. Notably, parallel work by other investigators has highlighted the important emerging role of the TLKs in this novel area of work [

54,

55].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization by A.D.B. and D.O.; manuscript writing: A.D.B. and D.O.; methodology: A.D.B. and D.O.; experiment analysis and interpretation D.O. and A.D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a DoD-PCRP grant W81XWH-17-1-0417 and grants from the LA-CCRI and Feist-Weiller Cancer Center (FWCC) of LSU Health Shreveport to ADB.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and certified that no human subjects were used.

Informed Consent Statement

No human subjects were used. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional ACUC – protocol P-20-24 TARGETING THE TLK1/NEK1 AXIS IN PROSTATE CANCER. Approved 1-21-2020, for studies involving animals.

Data Availability Statement

Description of all data and materials can be found in the referenced article. No additional data has been withheld from the public.

Acknowledgments

We like to thank the INLET facility of LSU Health Shreveport, especially Ana maria Dragoi and Brian Latimer for their assistance in working with the IncuCyte machines. We would also like to thank the Research Core Facility Genomics Core and animal facility of LSU Health Shreveport for the help with the qPCR analysis and animal work. Also special thanks to Lucia Solitro for her expert use of the PE-IVIS.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen Y, Clegg NJ, Scher HI: Anti-androgens and androgen-depleting therapies in prostate cancer: new agents for an established target. Lancet Oncol 2009, 10(10):981-991.

- Chism DD, De Silva D, Whang YE: Mechanisms of acquired resistance to androgen receptor targeting drugs in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2014, 14(11):1369-1378.

- Salem O, Hansen CG: The Hippo Pathway in Prostate Cancer. Cells 2019, 8(4).

- Yu FX, Zhao B, Guan KL: Hippo Pathway in Organ Size Control, Tissue Homeostasis, and Cancer. Cell 2015, 163(4):811-828. doi: 810.1016/j.cell.2015.1010.1044.

- Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan K-L: The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes & development 2010, 24(9):862-874.

- Kofler M, Kapus A: Nuclear Import and Export of YAP and TAZ. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(20).

- Shreberk-Shaked M, Oren M: New insights into YAP/TAZ nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling: new cancer therapeutic opportunities? Mol Oncol 2019, 13(6):1335-1341.

- Yang Y, Wu M, Pan Y, Hua Y, He X, Li X, Wang J, Gan X: WW domains form a folded type of nuclear localization signal to guide YAP1 nuclear import. J Cell Biol 2024, 223(6).

- Kofler M, Speight P, Little D, Di Ciano-Oliveira C, Szászi K, Kapus A: Mediated nuclear import and export of TAZ and the underlying molecular requirements. Nature Communications 2018, 9(1):4966.

- Elosegui-Artola A, Andreu I, Beedle AEM, Lezamiz A, Uroz M, Kosmalska AJ, Oria R, Kechagia JZ, Rico-Lastres P, Le Roux AL et al.: Force Triggers YAP Nuclear Entry by Regulating Transport across Nuclear Pores. Cell 2017, 171(6):1397-1410.e1314.

- Sugihara T, Werneburg NW, Hernandez MC, Yang L, Kabashima A, Hirsova P, Yohanathan L, Sosa C, Truty MJ, Vasmatzis G et al.: YAP Tyrosine Phosphorylation and Nuclear Localization in Cholangiocarcinoma Cells Are Regulated by LCK and Independent of LATS Activity. Molecular Cancer Research 2018, 16(10):1556-1567.

- Qian H, Ding C-H, Liu F, Chen S-J, Huang C-K, Xiao M-C, Hong X-L, Wang M-C, Yan F-Z, Ding K et al.: SRY-Box transcription factor 9 triggers YAP nuclear entry via direct interaction in tumors. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9(1):96.

- Kuser-Abali G, Alptekin A, Lewis M, Garraway IP, Cinar B: YAP1 and AR interactions contribute to the switch from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth in prostate cancer. Nature communications 2015, 6:8126-8126.

- Noh M-G, Kim SS, Hwang EC, Kwon DD, Choi C: Yes-Associated Protein Expression Is Correlated to the Differentiation of Prostate Adenocarcinoma. Journal of pathology and translational medicine 2017, 51(4):365-373.

- Zhang L, Yang S, Chen X, Stauffer S, Yu F, Lele SM, Fu K, Datta K, Palermo N, Chen Y et al.: The hippo pathway effector YAP regulates motility, invasion, and castration-resistant growth of prostate cancer cells. Molecular and cellular biology 2015, 35(8):1350-1362.

- Nguyen LT, Tretiakova MS, Silvis MR, Lucas J, Klezovitch O, Coleman I, Bolouri H, Kutyavin VI, Morrissey C, True LD et al.: ERG Activates the YAP1 Transcriptional Program and Induces the Development of Age-Related Prostate Tumors. Cancer Cell 2015, 27(6):797-808. doi: 710.1016/j.ccell.2015.1005.1005.

- Khalil MI, Ghosh I, Singh V, Chen J, Zhu H, De Benedetti A: NEK1 Phosphorylation of YAP Promotes Its Stabilization and Transcriptional Output. Cancers 2020, 12(12):3666.

- Ghosh I, Khalil MI, Mirza R, King J, Olatunde D, De Benedetti A: NEK1-Mediated Phosphorylation of YAP1 Is Key to Prostate Cancer Progression. Biomedicines 2023, 11(3):734.

- Sunavala-Dossabhoy G, De Benedetti A: Tousled homolog, TLK1, binds and phosphorylates Rad9; tlk1 acts as a molecular chaperone in DNA repair. DNA Repair 2009, 8:87-102.

- Collak FK, Demir U, Sagir F: YAP1 Is Involved in Tumorigenic Properties of Prostate Cancer Cells. Pathol Oncol Res 2020, 26(2):867-876.

- Lee H-C, Ou C-H, Huang Y-C, Hou P-C, Creighton CJ, Lin Y-S, Hu C-Y, Lin S-C: YAP1 overexpression contributes to the development of enzalutamide resistance by induction of cancer stemness and lipid metabolism in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40(13):2407-2421.

- Khalil MI, Ghosh I, Singh V, Chen J, Zhu H, De Benedetti A: NEK1 Phosphorylation of YAP Promotes Its Stabilization and Transcriptional Output. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12(12).

- Zhao Y, Sheldon M, Sun Y, Ma L: New Insights into YAP/TAZ-TEAD-Mediated Gene Regulation and Biological Processes in Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15(23):5497.

- Singh V, Bhoir S, Chikhale RV, Hussain J, Dwyer D, Bryce RA, Kirubakaran S, De Benedetti A: Generation of Phenothiazine with Potent Anti-TLK1 Activity for Prostate Cancer Therapy. iScience 2020, 23(9):101474.

- Hu X, Zhang Y, Yu H, Zhao Y, Sun X, Li Q, Wang Y: The role of YAP1 in survival prediction, immune modulation, and drug response: A pan-cancer perspective. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13.

- Kim MH, Kim CG, Kim SK, Shin SJ, Choe EA, Park SH, Shin EC, Kim J: YAP-Induced PD-L1 Expression Drives Immune Evasion in BRAFi-Resistant Melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res 2018, 6(3):255-266.

- Bishop JL, Sio A, Angeles A, Roberts ME, Azad AA, Chi KN, Zoubeidi A: PD-L1 is highly expressed in Enzalutamide resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6(1):234-242.

- Jayaprakash P, Ai M, Liu A, Budhani P, Bartkowiak T, Sheng J, Ager C, Nicholas C, Jaiswal AR, Sun Y et al.: Targeted hypoxia reduction restores T cell infiltration and sensitizes prostate cancer to immunotherapy. J Clin Invest 2018, 128(11):5137-5149.

- Wang M, Ran X, Leung W, Kawale A, Saxena S, Ouyang J, Patel PS, Dong Y, Yin T, Shu J et al.: ATR inhibition induces synthetic lethality in mismatch repair-deficient cells and augments immunotherapy. Genes Dev 2023, 37(19-20):929-943.

- Zheng W, Liu A, Xia N, Chen N, Meurens F, Zhu J: How the Innate Immune DNA Sensing cGAS-STING Pathway Is Involved in Apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(3).

- Singh V, Khalil MI, De Benedetti A: The TLK1/Nek1 axis contributes to mitochondrial integrity and apoptosis prevention via phosphorylation of VDAC1. Cell Cycle 2020, 19(3):363-375.

- Singh V, Jaiswal PK, Ghosh I, Koul HK, Yu X, De Benedetti A: The TLK1-Nek1 axis promotes prostate cancer progression. Cancer Letters 2019, 453:131-141.

- Bhoir S, Ogundepo O, Yu X, De benedetti A: Exploiting TLK1 and Cisplatin Synergy for Synthetic Lethality in Androgen-Insensitive Prostate Cancer. In: Preprints. Preprints; 2023.

- Szulzewsky F, Holland EC, Vasioukhin V: YAP1 and its fusion proteins in cancer initiation, progression and therapeutic resistance. Dev Biol 2021, 475:205-221.

- Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan KL: The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev 2010, 24(9):862-874.

- Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, Wang CY, Guan KL: A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF(beta-TRCP). Genes Dev 2010, 24(1):72-85.

- Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, Li L, Li W, Li S, Yu J, Lin JD, Wang CY, Chinnaiyan AM et al.: TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev 2008, 22(14):1962-1971.

- Zhao J, Herrera-Diaz J, Gross D: Domain-wide displacement of histones by activated heat shock factor occurs independently of swi/snf and is not correlated with RNA polymerase II density. 2005, 25: 8985-8999.

- Zhao J, Zhai X, Zhou J: Snapshot of the evolution and mutation patterns of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2020.

- Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y: Yap1 phosphorylation by c-Abl is a critical step in selective activation of proapoptotic genes in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell 2008, 29(3):350-361. doi: 310.1016/j.molcel.2007.1012.1022.

- Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan KL: The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev 2010, 24(9):862-874. doi: 810.1101/gad.1909210.

- Basu S, Totty NF, Irwin MS, Sudol M, Downward J: Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14-3-3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell 2003, 11(1):11-23. [CrossRef]

- Piccolo S, Dupont S, Cordenonsi M: The biology of YAP/TAZ: hippo signaling and beyond. Physiol Rev 2014, 94(4):1287-1312. doi: 1210.1152/physrev.00005.02014.

- Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, Wang CY, Guan KL: A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF(beta-TRCP). Genes Dev 2010, 24(1):72-85. [CrossRef]

- Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y: Yap1 phosphorylation by c-Abl is a critical step in selective activation of proapoptotic genes in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell 2008, 29(3):350-361.

- Li B, He J, Lv H, Liu Y, Lv X, Zhang C, Zhu Y, Ai D: c-Abl regulates YAPY357 phosphorylation to activate endothelial atherogenic responses to disturbed flow. J Clin Invest 2019, 129(3):1167-1179.

- Hong X, Nguyen HT, Chen Q, Zhang R, Hagman Z, Voorhoeve PM, Cohen SM: Opposing activities of the Ras and Hippo pathways converge on regulation of YAP protein turnover. Embo J 2014, 33(21):2447-2457.

- Tsubouchi A, Sakakura J, Yagi R, Mazaki Y, Schaefer E, Yano H, Sabe H: Localized suppression of RhoA activity by Tyr31/118-phosphorylated paxillin in cell adhesion and migration. J Cell Biol 2002, 159(4):673-683.

- Marasco M, Carlomagno T: Specificity and regulation of phosphotyrosine signaling through SH2 domains. J Struct Biol X 2020, 4:100026.

- Warren JSA, Xiao Y, Lamar JM: YAP/TAZ Activation as a Target for Treating Metastatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10(4).

- Cheng S, Prieto-Dominguez N, Yang S, Connelly ZM, StPierre S, Rushing B, Watkins A, Shi L, Lakey M, Baiamonte LB et al.: The expression of YAP1 is increased in high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma but is reduced in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2020, 23(4):661-669.

- Kim TD, Shin S, Janknecht R: ETS transcription factor ERG cooperates with histone demethylase KDM4A. Oncol Rep 2016, 35(6):3679-3688.

- Lentz RW, Colton MD, Mitra SS, Messersmith WA: Innate Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: The Next Breakthrough in Medical Oncology? Mol Cancer Ther 2021, 20(6):961-974.

- Segura-Bayona S, Villamor-Payà M, Attolini CS-O, Koenig LM, Sanchiz-Calvo M, Boulton SJ, Stracker TH: Tousled-Like Kinases Suppress Innate Immune Signaling Triggered by Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres. Cell Reports 2020, 32(5):107983.

- Stracker TH, Osagie OI, Escorcia FE, Citrin DE: Exploiting the DNA Damage Response for Prostate Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2024, 16(1):83.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).