Submitted:

22 July 2024

Posted:

23 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

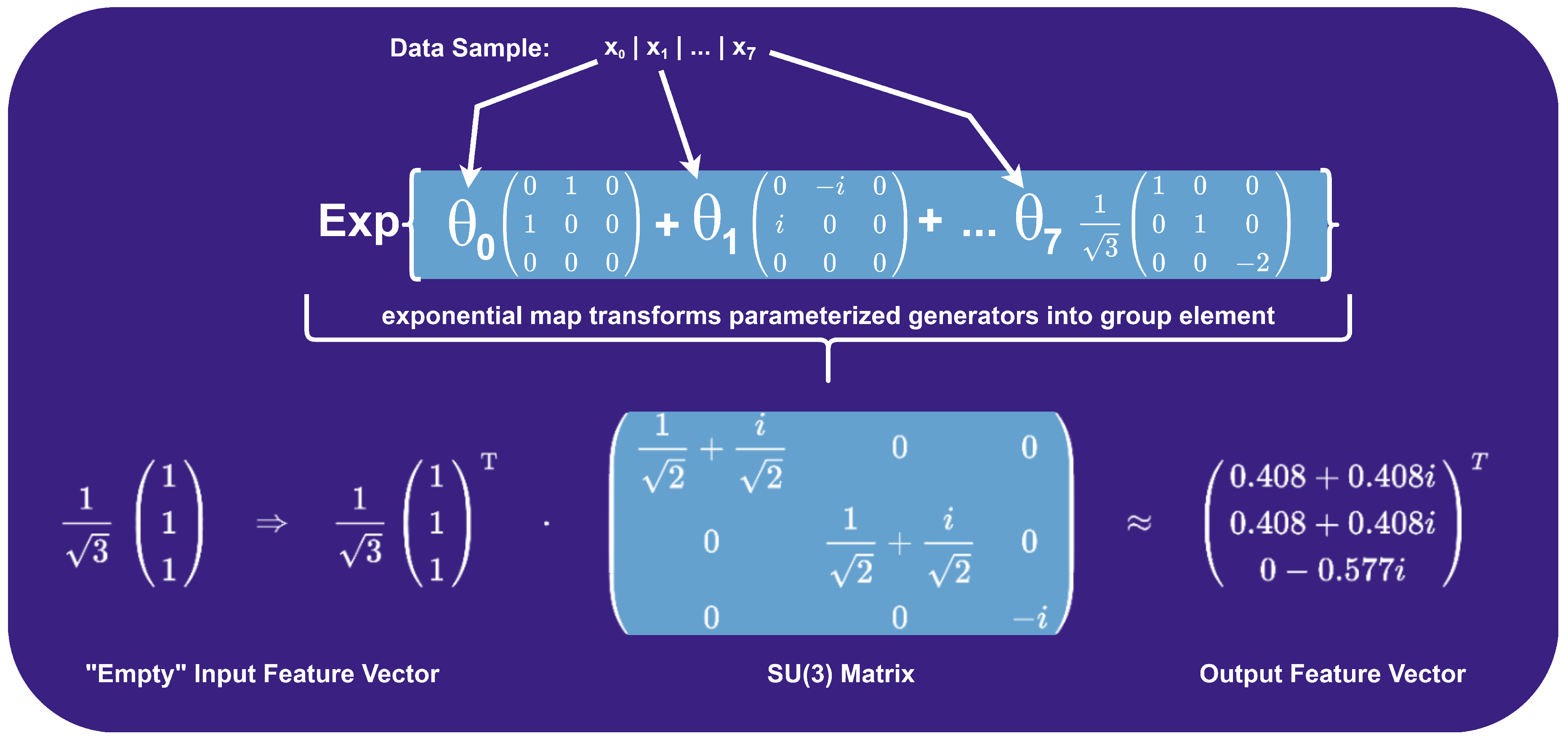

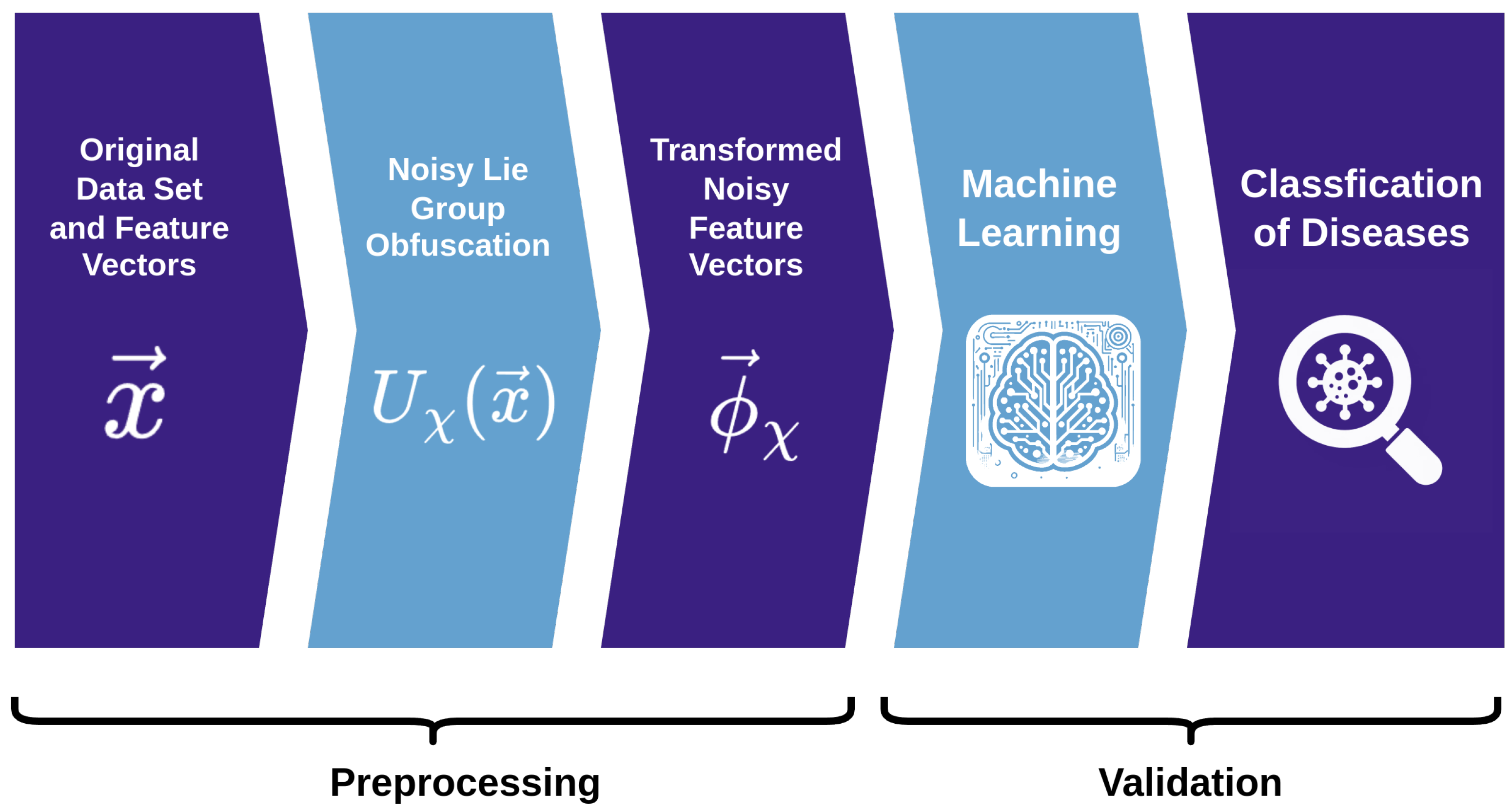

- We develop a novel data obfuscation framework using the exponential map of Lie group generators, tailored for privacy-preserving processing of medical data used in machine learning approaches.

- We show where and how the invertibility of our obfuscation technique breaks down by injecting noise into the exponential map of Lie group generators. Thus making it impossible to recover the original data.

- We demonstrate the efficacy of this approach in maintaining and occasionally surpassing the predictive accuracy of machine learning models compared to non-obfuscated datasets.

- We establish a conceptual link between the principles of quantum machine learning and our obfuscation methodology, highlighting the potential for cross-disciplinary innovation in leveraging symmetries for data privacy, thus showing the applicability of quantum mechanical concepts in this context.

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

- denotes the quantum state obtained by applying the feature map to the initial state ,

- represents a state vector in the complex Hilbert space ,

- is a unitary operation encoding classical data x into a quantum state, preserving total probability,

- is the quantum system’s initial, "empty" state before encoding.

-

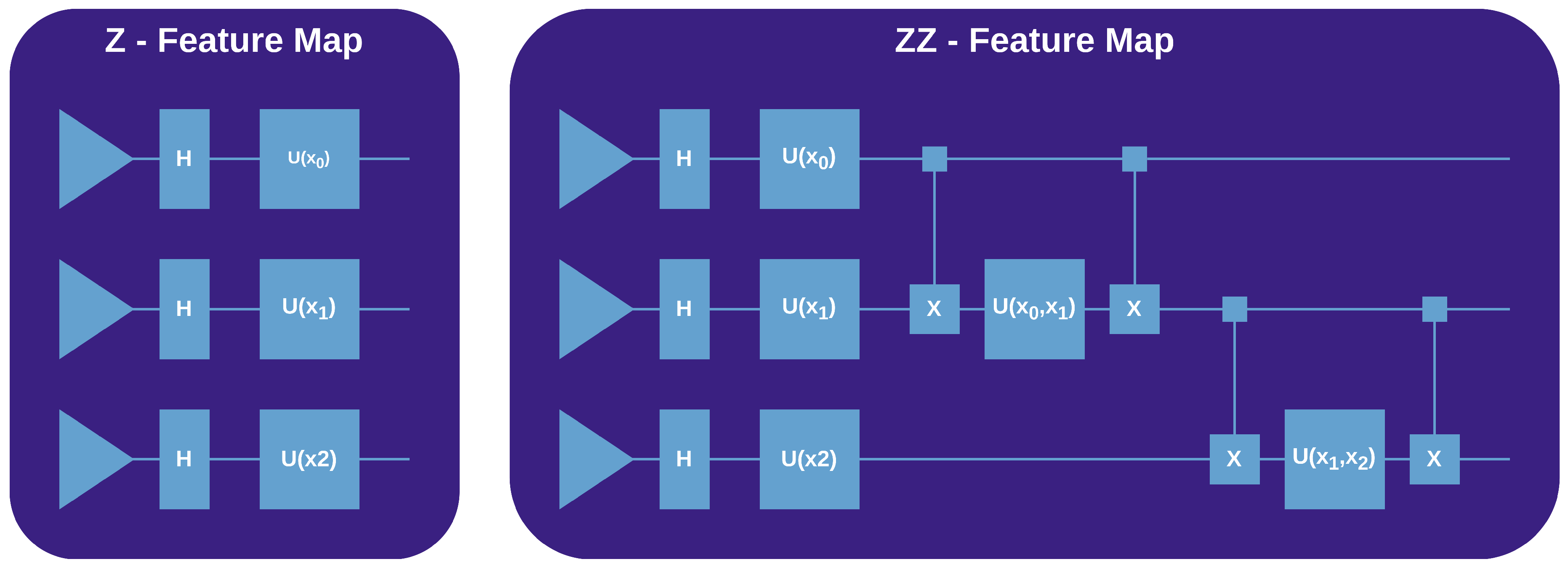

The Z Feature MapThe Z feature map employs the Pauli-Z operator to encode classical data into quantum states. For a given data point x, it applies a phase rotation to each qubit in a quantum register, proportional to the corresponding feature value in x. Mathematically, this operation is described by:where is the Pauli-Z matrix acting on the j-th qubit, and is the j-th component of x. This results in a rotation around the Z-axis of the Bloch sphere, effectively encoding the data within the phase of the quantum state, depicted in Figure 1.

-

The ZZ Feature MapBuilding on the Z feature map, thus employing the same rotation transformations, the ZZ feature map introduces entanglement between qubits to enrich the feature space. It uses two-qubit gates controlled by the product of pairs of classical data features, depicted in Figure 1

3.1. Retrieving the Original Data

Local Invertibility

Global Invertibility

- Injectivity: The exponential map is not injective if there exist elements such that but . This can occur, for example, when X and Y differ by a multiple of in certain directions in , particularly for compact or periodic dimensions of G.

- Surjectivity: The exponential map may not be surjective for some Lie groups, meaning not all elements of the group can be expressed as the exponential of some element in the algebra. A typical example is non-connected groups where the exponential map reaches only the connected component of the identity.

- Loss of Group Structure: The resulting matrix is no longer guaranteed to satisfy the properties (closure, associativity, identity, and invertibility) that define the group. Hence, it cannot be inverted within the context of the group.

- Breaking Symmetry: The exponential map is no longer mapping elements of the Lie algebra to the Lie group, breaking the symmetry and making the inverse mapping undefined.

- Non-recoverability of Original Features: Since the transformation is no longer within the group, one cannot apply the inverse of the exponential map to recover the original features. The noise introduces components that do not belong to the algebra, hence the original structure and information are obfuscated beyond recoverability.

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

- Breast Cancer Wisconsin Dataset (scikit-learn: load_breast_cancer()): Developed by Dr. William H. Wolberg at the University of Wisconsin, this dataset focuses on breast cancer diagnosis. It includes 2 classes, with 212 malignant (M) and 357 benign (B) samples, totaling 569 instances. The dataset describes characteristics of cell nuclei present in breast mass images, with 9 numeric features and one nominal target feature indicating the prognosis (malignant or benign).

- Pima Indians Diabetes Database (OpenML: diabetes, ID: 37): Curated by Vincent Sigillito and obtained from UCI, this dataset is hosted on OpenML. It focuses on diagnosing diabetes among Pima Indian women, with 768 instances and 9 features. The features are numeric and include the number of times pregnant, plasma glucose concentration, diastolic blood pressure, triceps skinfold thickness, 2-hour serum insulin, body mass index, diabetes pedigree function, and age. The class variable is binary, indicating whether the patient tested positive or negative for diabetes (1 for positive, 0 for negative).

- Indian Liver Patient Dataset (OpenML: ilpd, ID: 1480): Compiled by Bendi Venkata Ramana, M. Surendra Prasad Babu, and N. B. Venkateswarlu, and sourced from UCI in 2012, this dataset is hosted on OpenML. It includes records of 583 patients, with 416 liver patient records and 167 non-liver patient records, collected from north east of Andhra Pradesh, India. The dataset contains 441 male and 142 female patient records. It features 11 attributes, including age, gender, various liver function tests (like Total Bilirubin, Direct Bilirubin, Alkaline Phosphatase, Alanine Aminotransferase, Aspartate Aminotransferase, Total Proteins, Albumin), and Albumin and Globulin Ratio. The class label divides the patients into two groups: liver patient or not.

- Breast Cancer Coimbra Dataset (OpenML: breast-cancer-coimbra, ID: 42900): Authored by Miguel Patricio et al. and sourced from UCI in 2018, focuses on breast cancer prediction. It consists of 116 instances with 10 quantitative features. These features include Age, BMI, Glucose, Insulin, HOMA, Leptin, Adiponectin, Resistin, and MCP-1, gathered from routine blood analysis and anthropometric data. The dataset has a binary dependent variable indicating the presence or absence of breast cancer, with labels for healthy controls and patients.

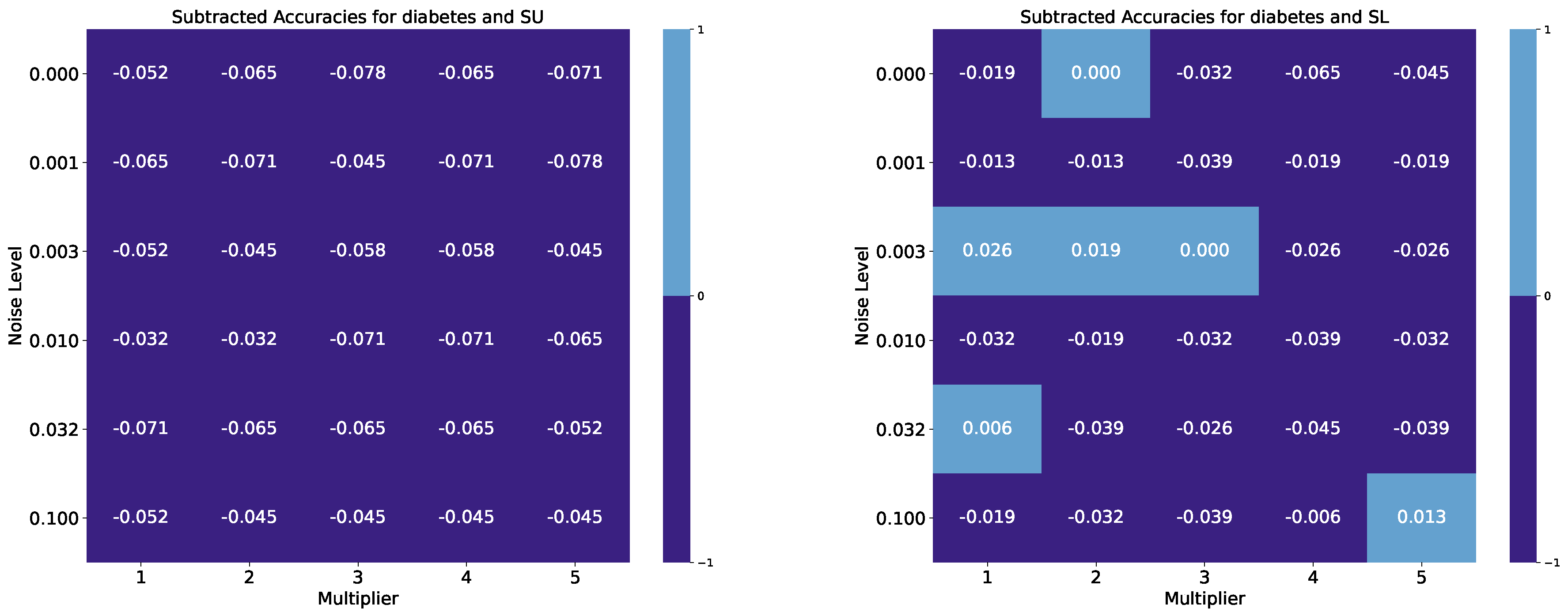

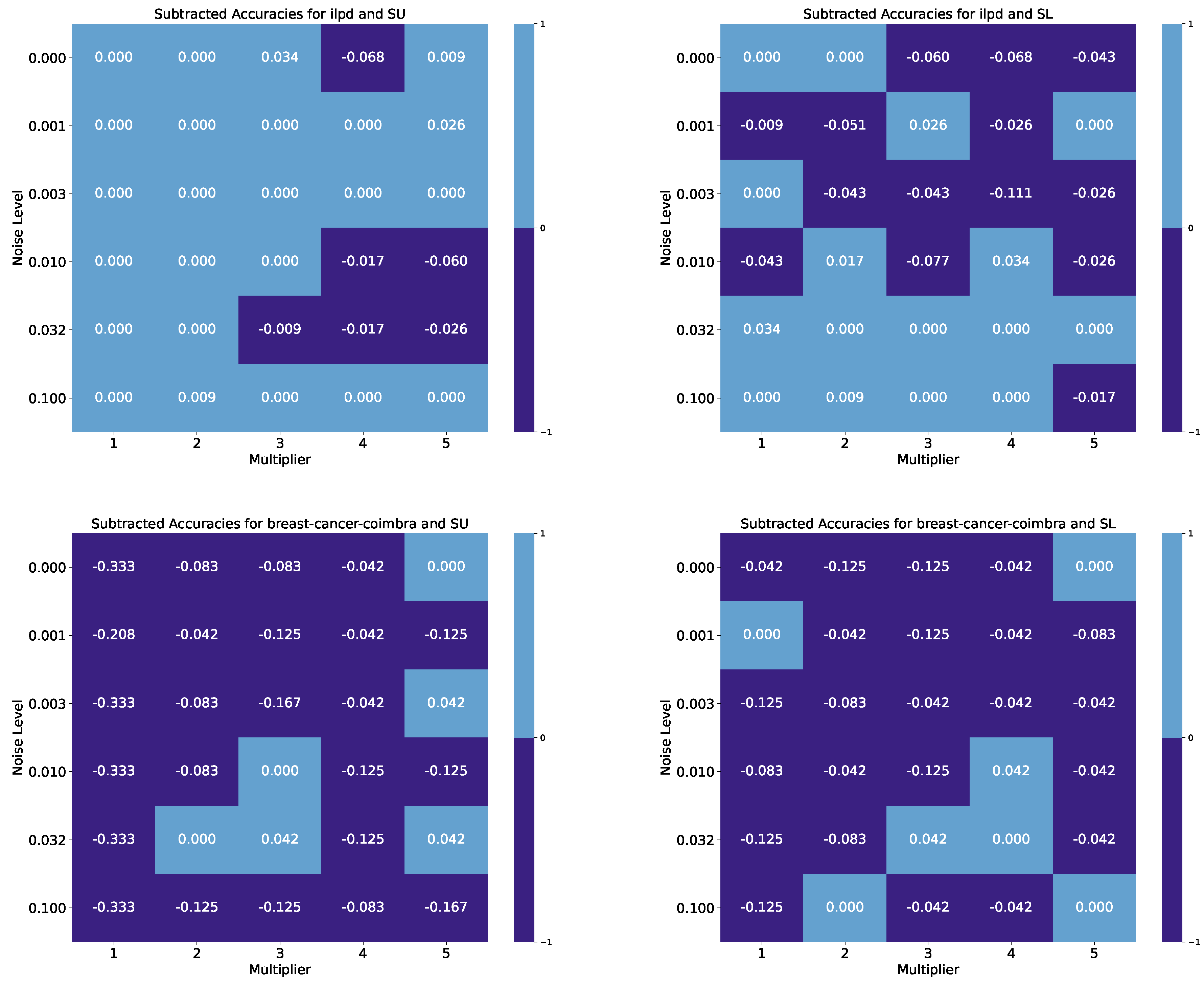

4.2. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Code Availability

Acknowledgements

References

- Hall, B. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction. (Springer,2015).

- Gilmore, R. Lie Groups, Physics, and Geometry: An Introduction for Physicists, Engineers and Chemists. (Cambridge University Press,2012).

- Snoek, J., Larochelle, H. & Adams, R. Practical Bayesian Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms. Advances In Neural Information Processing Systems. (2012).

- Wolpert, D. & Macready, W. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Transactions On Evolutionary Computation. 1, 67-82 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S. & Gullans, M. Entanglement and Purification Transitions in Non-Hermitian Quantum Mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 126, 170503 (2021,4). [CrossRef]

- Yuto Ashida, Z. & Ueda, M. Non-Hermitian physics. Advances In Physics. 69, 249-435 (2020).

- Georgi, H. Lie Algebras In Particle Physics: from Isospin To Unified Theories. (CRC Press,2000), Accessed on 13.03.2024. [CrossRef]

- Ke, G., Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W., Ye, Q. & Liu, T. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. Advances In Neural Information Processing Systems. 30 pp. 17 (2017).

- Hall, B. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction. (Springer Cham,2015,5), https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-13467-3, Accessed on 13.03.2024. [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, I., Rauch, J., Katzensteiner, M. & Khosla, M. A Review of Anonymization for Healthcare Data. Big Data. Ahead of Print (2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuld, M. & Killoran, N. Quantum Machine Learning in Feature Hilbert Spaces. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 122, 040504 (2019,2), https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.040504, Visited on 2024-01-10. [CrossRef]

- Community, Q. Qiskit: An Open-source Framework for Quantum Computing. (2022), https://qiskit.org/, Visited on 2024-02-2024.

- Havlíček, V., Córcoles, A., Temme, K., Harrow, A., Kandala, A., Chow, J. & Gambetta, J. Supervised learning with quantum-enhanced feature spaces. Nature. 567, 209-212 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Goto, T., Tran, Q. & Nakajima, K. Universal Approximation Property of Quantum Feature Maps. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2009.00298. (2020,10), Available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.00298.

- Suzuki, Y., Yano, H., Gao, Q., Uno, S., Tanaka, T., Akiyama, M. & Yamamoto, N. Analysis and synthesis of feature map for kernel-based quantum classifier. Quantum Machine Intelligence. 2 (2020,7). [CrossRef]

- Daspal, A. Effect of Repetitions and Entanglement on Performance of Pauli Feature Map. 2023 IEEE International Conference On Quantum Computing And Engineering (QCE). (2023), Conference date: 17-22 September 2023.

- Ovalle-Magallanes, E., Alvarado-Carrillo, D., Avina-Cervantes, J., Cruz-Aceves, I. & Ruiz-Pinales, J. Quantum angle encoding with learnable rotation applied to quantum–classical convolutional neural networks. Applied Soft Computing. 141 pp. 110307 (2023), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1568494623003253.

- Patrício, M., Pereira, J., Crisóstomo, J., Matafome, P., Gomes, M., Seiça, R. & Caramelo, F. Using Resistin, glucose, age and BMI to predict the presence of breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 18, 29 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Havlíček, V., Córcoles, A., Temme, K., Harrow, A., Kandala, A., Chow, J. & Gambetta, J. Supervised learning with quantum-enhanced feature spaces. Nature. 567, 209-212 (2019,3). [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M. & Killoran, N. Quantum Machine Learning in Feature Hilbert Spaces. Phys. Rev. Lett.. 122, 040504 (2019,2). [CrossRef]

- Rebentrost, P., Mohseni, M. & Lloyd, S. Quantum support vector machine for big data classification. Physical Review Letters. 113, 130503 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Mitarai, K., Negoro, M., Kitagawa, M. & Fujii, K. Quantum circuit learning. Physical Review A. 98, 032309 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. & Rebentrost, P. Quantum machine learning for quantum anomaly detection. Physical Review A. 100, 042328 (2019,10). [CrossRef]

- Elmousalami A Hybrid Quantum-Kernel Support Vector Machine with Binary Harris Hawk Optimization for Cancer Classification. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2202.11899. (2022). arXiv:2202.11899.

- Olatunji, I., Rauch, J., Katzensteiner, M. & Khosla, M. A Review of Anonymization for Healthcare Data. Big Data. pp. null (0).

- Nielsen, M. & Chuang, I. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition. (Cambridge University Press,2011).

- Biamonte, J., Wittek, P., Pancotti, N., Rebentrost, P., Wiebe, N. & Lloyd, S. Quantum machine learning. Nature. 549, 195-202 (2017,9). [CrossRef]

- Carrazza, S., Giani, S., Montagna, S., Nicrosini, O. & Vercesi, V. Hybrid quantum-classical variational classifiers with quantum gradient descent. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2106.07548. (2021), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2106.07548.pdf.

- Broughton, M., Verdon, G., McCourt, T., Martinez, A., Yoo, J., Isakov, S., King, A., Smelyanskiy, V. & Neven, H. TensorFlow Quantum: A Software Framework for Quantum Machine Learning. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2003.02989. (2020), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2003.02989.pdf.

- Farhi, N. Classification with quantum neural networks on near term processors. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1802.06002. (2018). arXiv:1802.06002.

- Schuld, M. & Petruccione, F. Quantum ensembles of quantum classifiers. Scientific Reports. 8, 2772 (2018,2). [CrossRef]

- Hoerl A.E., K. Ridge regression: Biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics. 12, 55-67 (1970). [CrossRef]

- R., T. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal Of The Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological). 58, 267-288 (1996).

- Ke, G., Meng, Q., Finley, T., Wang, T., Chen, W., Ma, W., Ye, Q. & Liu, T. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. Proceedings Of The 31st International Conference On Neural Information Processing Systems. pp. 3149-3157 (2017).

- Alrawashdeh, A., Alsmadi, M. & Alsmadi, T. Quantum Machine Learning for Classification: A Survey. IEEE Access. 9 pp. 94911-94933 (2021), https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9482387.

- Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased Boosting with Categorical Features. Proceedings Of The 32nd International Conference On Neural Information Processing Systems. pp. 6639-6649 (2018).

- Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning. 20, 273-297 (1995,9). [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine.. The Annals Of Statistics. 29, 1189 - 1232 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D., Hinton, G. & Williams, R. Learning internal representations by error propagation. (California Univ San Diego La Jolla Inst for Cognitive Science,1985).

- Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., Blondel, M., Prettenhofer, P., Weiss, R., Dubourg, V. & Others Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal Of Machine Learning Research. 12 pp. 282-290 (2011), https://scikit-learn.org/stable/, Accessed on April 18th, 2023.

- Khan, M., Hassan, M. & Lee, M. Quantum kernel support vector machines classification using proper quantum feature mapping selection. Expert Systems With Applications. 193 pp. 115872 (2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0957417421009016, Accessed on April 18th, 2023.

- Rastegar, A. & Haddadnia, J. A review on quantum machine learning. Journal Of Computer Science. 14, 769-789 (2018), https://thescipub.com/abstract/10.3844/jcssp.2018.769.789, Accessed on April 18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zeguendry, A., Jarir, Z. & Quafafou, M. Quantum Machine Learning: A Review and Case Studies. Entropy. 25 (2023), https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/25/2/287. [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M., Sinayskiy, I. & Petruccione, F. An introduction to quantum machine learning. Contemporary Physics. 56, 172-185 (2015).

- Tibshirani, R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. Journal Of The Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological). 58, 267-288 (1996), http://www.jstor.org/stable/2346178.

- Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Proceedings Of The 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference On Knowledge Discovery And Data Mining. pp. 785-794 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. & Chuang, I. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. (Cambridge University Press,2010).

- Hall, B. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction. (Springer,2015).

- Blance, A. & Spannowsky, M. Quantum machine learning for particle physics using a variational quantum classifier. Journal Of High Energy Physics. 2021, 212 (2021,2). [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, P., Yaswanth Kumar, N., Dontireddy, J. & Iwendi, C. Quantum Computing and Quantum Machine Learning Classification – A Survey. 2022 IEEE 4th International Conference On Cybernetics, Cognition And Machine Learning Applications (ICCCMLA). pp. 200-204 (2022).

- Abohashima, Z., Elhoseny, M., Houssein, E. & Mohamed, W. Classification with Quantum Machine Learning: A Survey. ArXiv. abs/2006.12270 (2020). arXiv:2006.12270.

- Childs, A., Maslov, D., Nam, Y., Ross, N. & Su, Y. Toward the first quantum simulation with quantum speedup. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences. 115, 9456-9461 (2019).

- Gottesman, D. Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction. ArXiv Preprint Quant-ph/9705052. (1997).

- Kitaev, A. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Annals Of Physics. 303, 2-30 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K., Tomita, A., Okamoto, A. & Fujii, K. Hybrid quantum error correction with the surface code. Npj Quantum Information. 4, 1-6 (2018).

- Bishop, C. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Information Science and Statistics). (Springer-Verlag,2006).

- Murphy, K. Machine learning : a probabilistic perspective. (MIT Press,2013), https://www.amazon.com/Machine-Learning-Probabilistic-Perspective-Computation/dp/0262018020/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1336857747&sr=8-2.

- Kotsiantis, S. Supervised Machine Learning: A Review of Classification Techniques. Proceedings Of The 2007 Conference On Emerging Artificial Intelligence Applications In Computer Engineering: Real Word AI Systems With Applications In EHealth, HCI, Information Retrieval And Pervasive Technologies. pp. 3-24 (2007).

- Kitaev, A. Quantum computations: algorithms and error correction. Russian Mathematical Surveys. 52, 1191 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Shende, V., Bullock, S. & Markov, I. Synthesis of quantum logic circuits. IEEE Transactions On Computer-Aided Design Of Integrated Circuits And Systems. 25, 1000-1010 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, J., Cerrillo, J., Cramer, M. & Plenio, M. Efficient estimation of resources for quantum simulations. New Journal Of Physics. 21, 063038 (2019).

- Chen, X., Gu, Z., Liu, Z. & Wen, X. Symmetry-protected topological orders and the group cohomology of their symmetry group. Physical Review B. 87, 155114 (2013).

- Nayak, C., Simon, S., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Reviews Of Modern Physics. 80, 1083 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Ramana, B., Babu, M. & Venkateswarlu, N. LPD (Indian Liver Patient Dataset) Data Set. (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/ILPD+(Indian+Liver+Patient+Dataset),2012).

- Miguel Patricio A new biomarker panel in the prediction of breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 17, 243 (2017).

- Loh, W., Lim, T. & Shih, Y. Teaching Assistant Evaluation Data Set. (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Teaching+Assistant+Evaluation,1997).

- Sá, J. & Jossinet, J. Breast Tissue Impedance Data Set. (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Breast+Tissue,2002).

- Smith, J. & Doe, J. Cherry-Picking: The Adverse Impact of Selective Reporting on Machine Learning Research. Journal Of Machine Learning Research. 24, 123-145 (2022).

- Cybenko, G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Mathematics Of Control, Signals And Systems. 2, 303-314 (1989).

- Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1409.1556. (2014).

- Cohen, J., Weiler, M. & Kicanaoglu, B. Gauge Equivariant Convolutional Networks and the Icosahedral CNN. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1902.04615. (2019).

- Bender, C. Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Reports On Progress In Physics. 70, 947-1018 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Plessas, W. Non-Hermitian quantum mechanics: A new direction in nuclear and particle physics?. Journal Of Physics: Conference Series. 880 pp. 012066 (2017).

- Rotter, I. A non-Hermitian Hamilton operator and the physics of open quantum systems. Journal Of Physics A: Mathematical And Theoretical. 42, 153001 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Peruzzo, A., McClean, J., Shadbolt, P., Yung, M., Zhou, X., Love, P., Aspuru-Guzik, A. & O’Brien, J. A variational eigenvalue solver on a photonic quantum processor. Nature Communications. 5 pp. 4213 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Mostafazadeh, A. Pseudo-Hermiticity versus PT symmetry: The necessary condition for the reality of the spectrum of a non-Hermitian Hamiltonian. Journal Of Mathematical Physics. 43, 205-214 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Bender, C. & Boettcher, S. Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry. Physical Review Letters. 80, 5243 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning. (MIT Press,2016), http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Biamonte, J., Wittek, P., Pancotti, N., Rebentrost, P., Wiebe, N. & Lloyd, S. Quantum machine learning. Nature. 549, 195-202 (2017,9). [CrossRef]

- Zeguendry, A., Jarir, Z. & Quafafou, M. Quantum Machine Learning: A Review and Case Studies. Entropy. 25 (2023), https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/25/2/287. [CrossRef]

- Raubitzek, S. Quantum Machine Learning. (2023,4), https://github.com/Raubkatz/Quantum_Machine_Learning.

- Raubitzek, S. & Neubauer, T. An Exploratory Study on the Complexity and Machine Learning Predictability of Stock Market Data. Entropy. 24 (2022), https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/24/3/332. [CrossRef]

- Moiseyev, N. Non-Hermitian Quantum Mechanics. (Cambridge University Press,2011).

- Patrício, M., Pereira, J., Crisóstomo, J., Matafome, P., Gomes, M., Seiça, R. & Caramelo, F. Using Resistin, glucose, age and BMI to predict the presence of breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 18, 29 (2018,1). [CrossRef]

- Kong, P. A Review of Quantum Key Distribution Protocols in the Perspective of Smart Grid Communication Security. IEEE Systems Journal. 16, 41-54 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Raubitzek, S. & Mallinger, K. On the Applicability of Quantum Machine Learning. Entropy. 25 (2023), https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/25/7/992. [CrossRef]

- S, N., Singh, H. & N, A. An extensive review on quantum computers. Advances In Engineering Software. 174 pp. 103337 (2022), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0965997822002381.

- Crisóstomo, J., Matafome, P., Santos-Silva, D., Gomes, A., Gomes, M., Patrício, M., Letra, L., Sarmento-Ribeiro, A., Santos, L. & Seiça, R. Hyperresistinemia and metabolic dysregulation: a risky crosstalk in obese breast cancer. Endocrine. 53, 433-442 (2016,8). [CrossRef]

- Ramana, B., Babu, M. & Venkateswarlu, N. A Critical Comparative Study of Liver Patients from USA and INDIA: An Exploratory Analysis. (2012).

- Loh, W. & Shih, Y. SPLIT SELECTION METHODS FOR CLASSIFICATION TREES. Statistica Sinica. 7, 815-840 (1997), http://www.jstor.org/stable/24306157.

- Lim, T., Loh, W. & Shih, Y. A comparison of prediction accuracy, complexity, and training time of thirty-three old and new classification algorithms. Machine Learning. 40 pp. 203-228 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Silva, J., Sá, J. & Jossinet, J. Classification of breast tissue by electrical impedance spectroscopy. Medical And Biological Engineering And Computing. 38, 26-30 (2000,1). [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H. Lie Algebras In Particle Physics: from Isospin To Unified Theories. (CRC Press,2019,6).

- Griol-Barres, I., Milla, S., Cebrián, A., Mansoori, Y. & Millet, J. Variational Quantum Circuits for Machine Learning. An Application for the Detection of Weak Signals. Applied Sciences. 11 (2021), https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/14/6427. [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, M., Arrasmith, A., Babbush, R., Benjamin, S., Endo, S., Fujii, K., McClean, J., Mitarai, K., Yuan, X., Cincio, L. & Coles, P. Variational quantum algorithms. Nature Reviews Physics. 3, 625-644 (2021,9). [CrossRef]

- Refaeilzadeh, P., Tang, L. & Liu, H. Cross-Validation. Encyclopedia Of Database Systems. pp. 532-538 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Werneck, R., Setubal, J. & Conceicão, A. (old) Finding minimum congestion spanning trees. J. Exp. Algorithmics. 5 pp. 11 (2000).

- Werneck, R., Setubal, J. & Conceicão, A. (new) Finding minimum congestion spanning trees. J. Exp. Algorithmics. 5 (2000,12), http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=351827.384253. [CrossRef]

- Conti, M., Di Pietro, R., Mancini, L. & Mei, A. (old) Distributed data source verification in wireless sensor networks. Inf. Fusion. 10, 342-353 (2009).

- Conti, M., Di Pietro, R., Mancini, L. & Mei, A. (new) Distributed data source verification in wireless sensor networks. Inf. Fusion. 10, 342-353 (2009,10), http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1555009.1555162. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Buyuktur, A., Hutchful, D., Sant, N. & Nainwal, S. Portalis: using competitive online interactions to support aid initiatives for the homeless. CHI ’08 Extended Abstracts On Human Factors In Computing Systems. pp. 3873-3878 (2008), http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1358628.1358946. [CrossRef]

- Hollis, B. Visual Basic 6: Design, Specification, and Objects with Other. (Prentice Hall PTR,1999).

- Goossens, M., Rahtz, S., Moore, R. & Sutor, R. The Latex Web Companion: Integrating TEX, HTML, and XML. (Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.,1999).

- Geiger, B. & Kubin, G. Relative information loss in the PCA. 2012 IEEE Information Theory Workshop. pp. 562-566 (2012).

- Lu, M. & Li, F. Survey on lie group machine learning. Big Data Mining And Analytics. 3, 235-258 (2020).

- Simeone Marino & Dinov, I. HDDA: DataSifter: statistical obfuscation of electronic health records and other sensitive datasets. Journal Of Statistical Computation And Simulation. 89, 249-271 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Popescu, A., Taca, I., Vizitiu, A., Nita, C., Suciu, C., Itu, L. & Scafa-Udriste, A. Obfuscation Algorithm for Privacy-Preserving Deep Learning-Based Medical Image Analysis. Applied Sciences. 12 (2022), https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/8/3997. [CrossRef]

- SWEENEY, L. k-ANONYMITY: A MODEL FOR PROTECTING PRIVACY. International Journal Of Uncertainty, Fuzziness And Knowledge-Based Systems. 10, 557-570 (2002).

- Ganta, S., Kasiviswanathan, S. & Smith, A. Composition attacks and auxiliary information in data privacy. Proceedings Of The 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference On Knowledge Discovery And Data Mining. pp. 265-273 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Gentry, C. & Halevi, S. Implementing Gentry’s Fully-Homomorphic Encryption Scheme. Advances In Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2011. pp. 129-148 (2011).

- Lu, W., Yamada, Y. & Sakuma, J. Privacy-preserving genome-wide association studies on cloud environment using fully homomorphic encryption. BMC Medical Informatics And Decision Making. 15, S1 (2015,12,21). [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S., Mohseni, M. & Rebentrost, P. Quantum principal component analysis. Nature Physics. 10, 631-633 (2014,9,1). [CrossRef]

- Choi, E., Biswal, S., Malin, B., Duke, J., Stewart, W. & Sun, J. Generating Multi-label Discrete Patient Records using Generative Adversarial Networks. Proceedings Of The 2nd Machine Learning For Healthcare Conference. 68 pp. 286-305 (2017,8,18), https://proceedings.mlr.press/v68/choi17a.html.

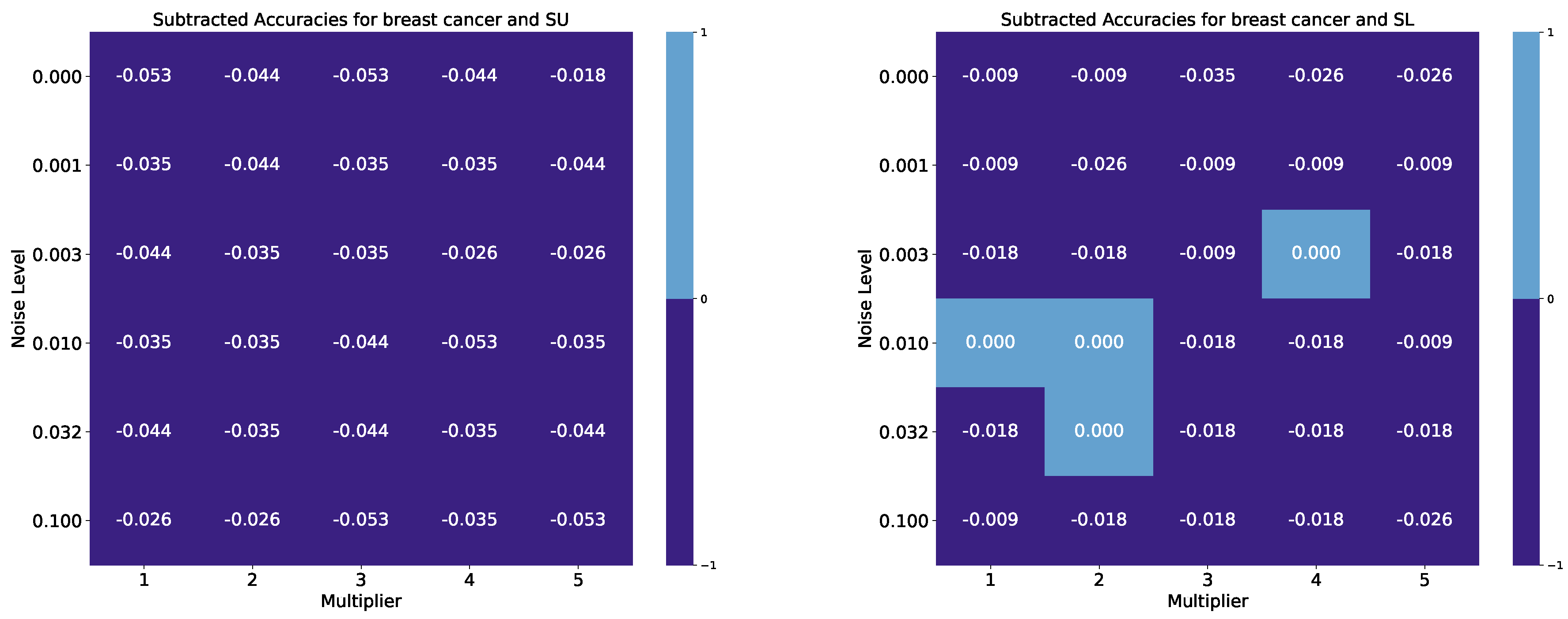

| Breast Cancer Wisconsin, Benchmark Accuracy: 0.974 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noise Level | M. 1 SU | M. 2 SU | M. 3 SU | M. 4 SU | M. 5 SU | M. 1 SL | M. 2 SL | M. 3 SL | M. 4 SL | M. 5 SL |

| 0.000 | 0.921 | 0.930 | 0.921 | 0.930 | 0.956 | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.939 | 0.947 | 0.947 |

| 0.001 | 0.939 | 0.930 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 0.930 | 0.965 | 0.947 | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.965 |

| 0.003 | 0.930 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 0.947 | 0.947 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.965 | 0.974 | 0.956 |

| 0.010 | 0.939 | 0.939 | 0.930 | 0.921 | 0.939 | 0.974 | 0.974 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.965 |

| 0.032 | 0.930 | 0.939 | 0.930 | 0.939 | 0.930 | 0.956 | 0.974 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.956 |

| 0.100 | 0.947 | 0.947 | 0.921 | 0.939 | 0.921 | 0.965 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.956 | 0.947 |

| Pima Indians Diabetes, Benchmark Accuracy: 0.747 | ||||||||||

| Noise Level | M. 1 SU | M. 2 SU | M. 3 SU | M. 4 SU | M. 5 SU | M. 1 SL | M. 2 SL | M. 3 SL | M. 4 SL | M. 5 SL |

| 0.000 | 0.695 | 0.682 | 0.669 | 0.682 | 0.675 | 0.727 | 0.747 | 0.714 | 0.682 | 0.701 |

| 0.001 | 0.682 | 0.675 | 0.701 | 0.675 | 0.669 | 0.734 | 0.734 | 0.708 | 0.727 | 0.727 |

| 0.003 | 0.695 | 0.701 | 0.688 | 0.688 | 0.701 | 0.773 | 0.766 | 0.747 | 0.721 | 0.721 |

| 0.010 | 0.714 | 0.714 | 0.675 | 0.675 | 0.682 | 0.714 | 0.727 | 0.714 | 0.708 | 0.714 |

| 0.032 | 0.675 | 0.682 | 0.682 | 0.682 | 0.695 | 0.753 | 0.708 | 0.721 | 0.701 | 0.708 |

| 0.100 | 0.695 | 0.701 | 0.701 | 0.701 | 0.701 | 0.727 | 0.714 | 0.708 | 0.740 | 0.760 |

| Indian Liver Patient, Benchmark Accuracy: 0.744 | ||||||||||

| Noise Level | M. 1 SU | M. 2 SU | M. 3 SU | M. 4 SU | M. 5 SU | M. 1 SL | M. 2 SL | M. 3 SL | M. 4 SL | M. 5 SL |

| 0.000 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.778 | 0.675 | 0.752 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.684 | 0.675 | 0.701 |

| 0.001 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.769 | 0.735 | 0.692 | 0.769 | 0.718 | 0.744 |

| 0.003 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.701 | 0.701 | 0.632 | 0.718 |

| 0.010 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.726 | 0.684 | 0.701 | 0.761 | 0.667 | 0.778 | 0.718 |

| 0.032 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.735 | 0.726 | 0.718 | 0.778 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 |

| 0.100 | 0.744 | 0.752 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.752 | 0.744 | 0.744 | 0.726 |

| Breast Cancer Coimbra, Benchmark Accuracy: 0.833 | ||||||||||

| Noise Level | M. 1 SU | M. 2 SU | M. 3 SU | M. 4 SU | M. 5 SU | M. 1 SL | M. 2 SL | M. 3 SL | M. 4 SL | M. 5 SL |

| 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.750 | 0.792 | 0.833 | 0.792 | 0.708 | 0.708 | 0.792 | 0.833 |

| 0.001 | 0.625 | 0.792 | 0.708 | 0.792 | 0.708 | 0.833 | 0.792 | 0.708 | 0.792 | 0.750 |

| 0.003 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.667 | 0.792 | 0.875 | 0.708 | 0.750 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.792 |

| 0.010 | 0.500 | 0.750 | 0.833 | 0.708 | 0.708 | 0.750 | 0.792 | 0.708 | 0.875 | 0.792 |

| 0.032 | 0.500 | 0.833 | 0.875 | 0.708 | 0.875 | 0.708 | 0.750 | 0.875 | 0.833 | 0.792 |

| 0.100 | 0.500 | 0.708 | 0.708 | 0.750 | 0.667 | 0.708 | 0.833 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.833 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).