Submitted:

21 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

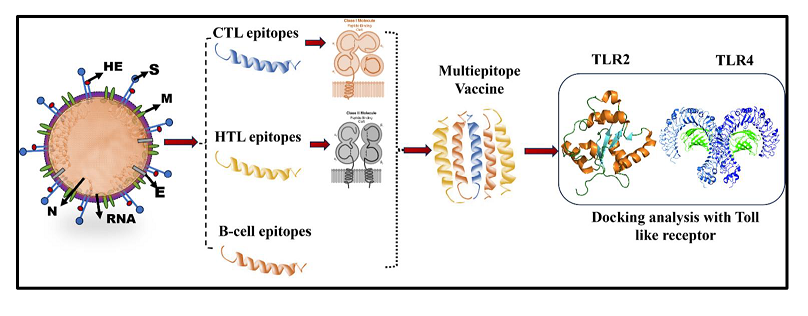

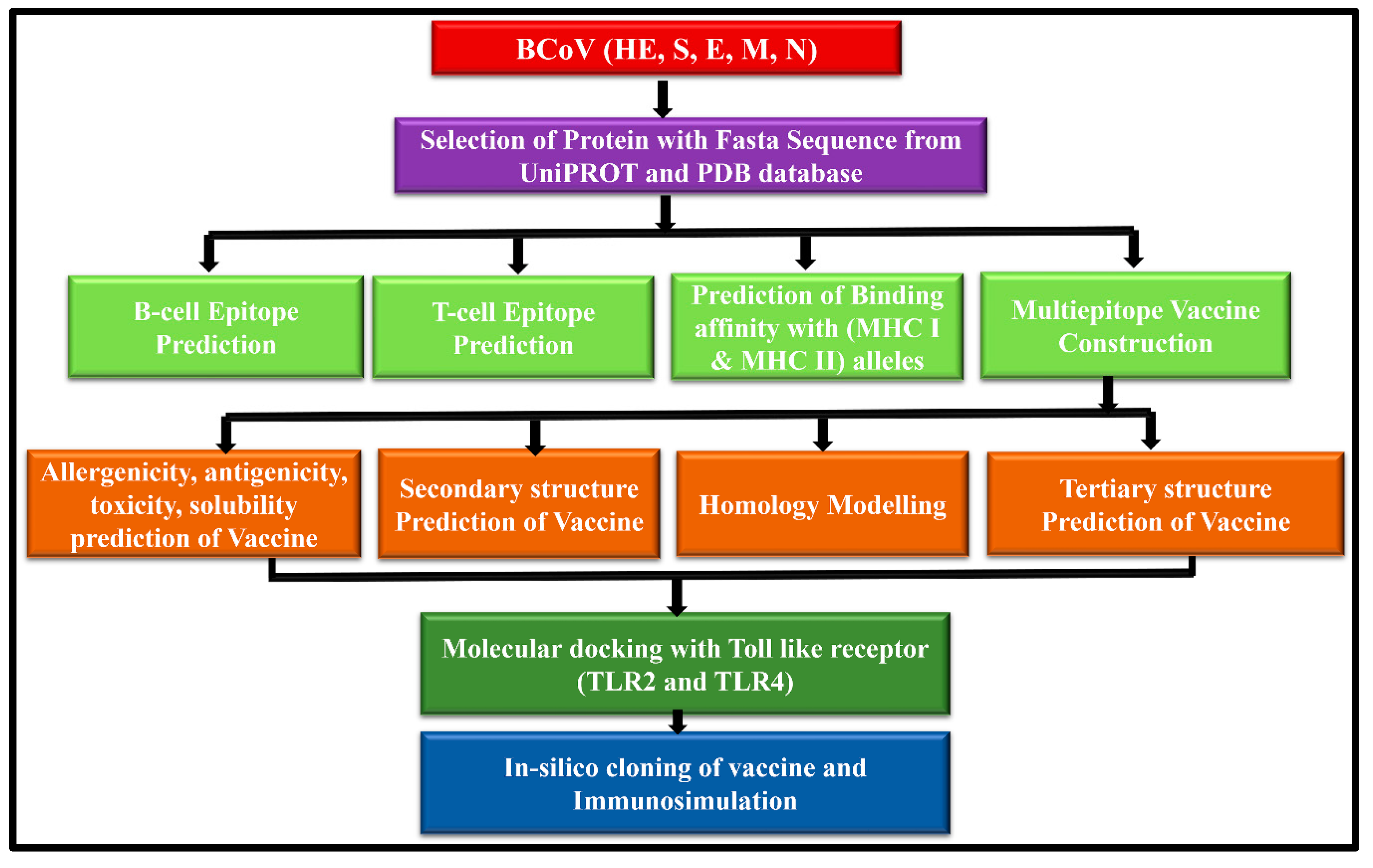

2. Materials and Methods:

2.1. Retrieval of the BCoV Structural Proteins Sequences

2.2. Prediction and Mapping of B Cells and T Cells Epitopes within the Major Structural Proteins of the BCoV

2.3. Evaluation of the Major Physicochemical Properties (Antigenicity, Allergenicity, Toxicity, Solubility, and Immunogenicity) to Design the BCoV Multi-Epitope-Based Vaccine Candidates

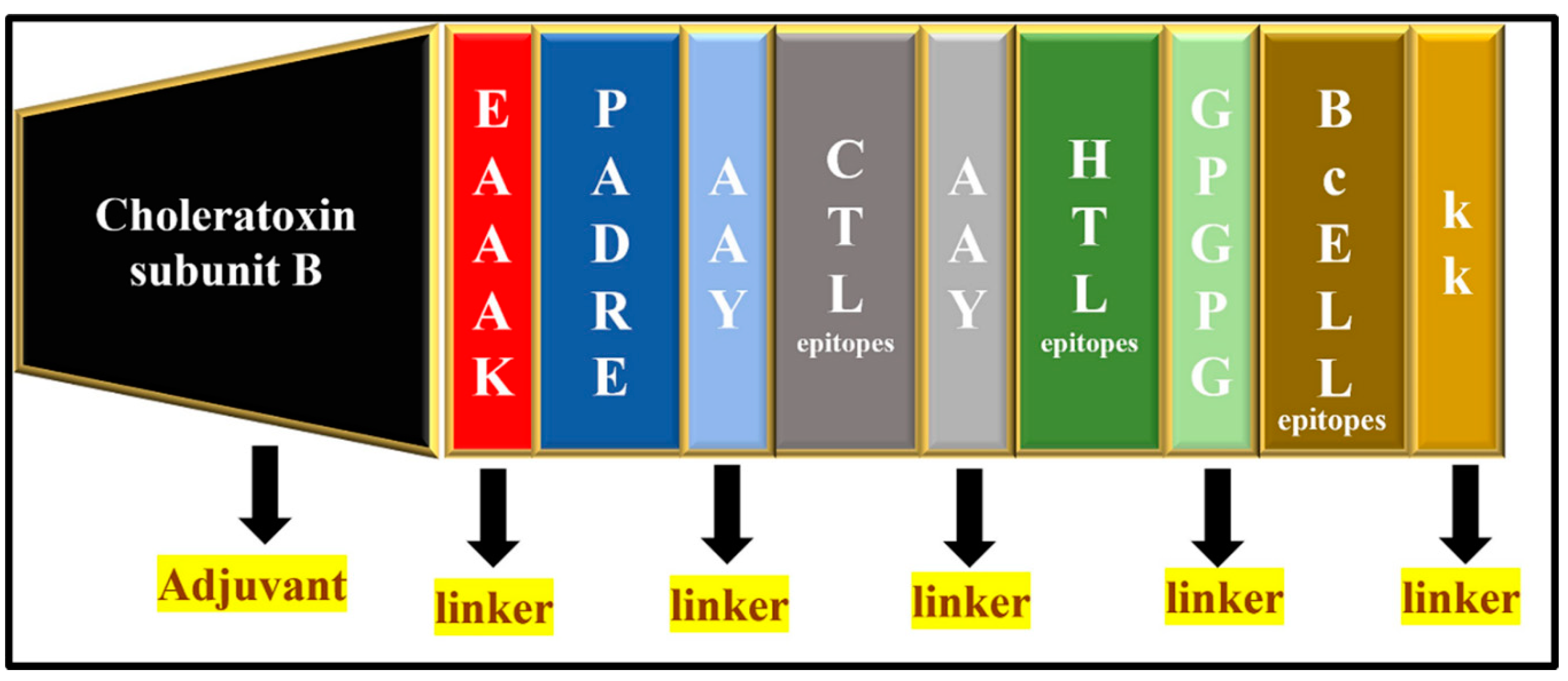

2.4. Designing of the Potential BCoV Multi-Epitope-Based Vaccines from the Major Structural Proteins and the Confirmation of Their Structural Arrangement

2.5. Analysis of the Secondary and the Tertiary Structures of the Designed Multiepitopes BCoV Based Vaccine Candidates

2.6. Molecular Docking and Binding Affinities of the Designed Epitopes-Based Vaccine Candidates with the Cellular Immunoreceptors

2.7. Applications of the In-Silico Immune Simulation and Computational Immunology to Evaluate the Immunogenic Properties of the Designed Multiepitopes BCoV-Based Vaccine Candidates

2.8. Application of a Combination of Codon Optimization and In-Silico Cloning for the Design of the Epitopes-Based Vaccine Constructs

3. Results and Discussion

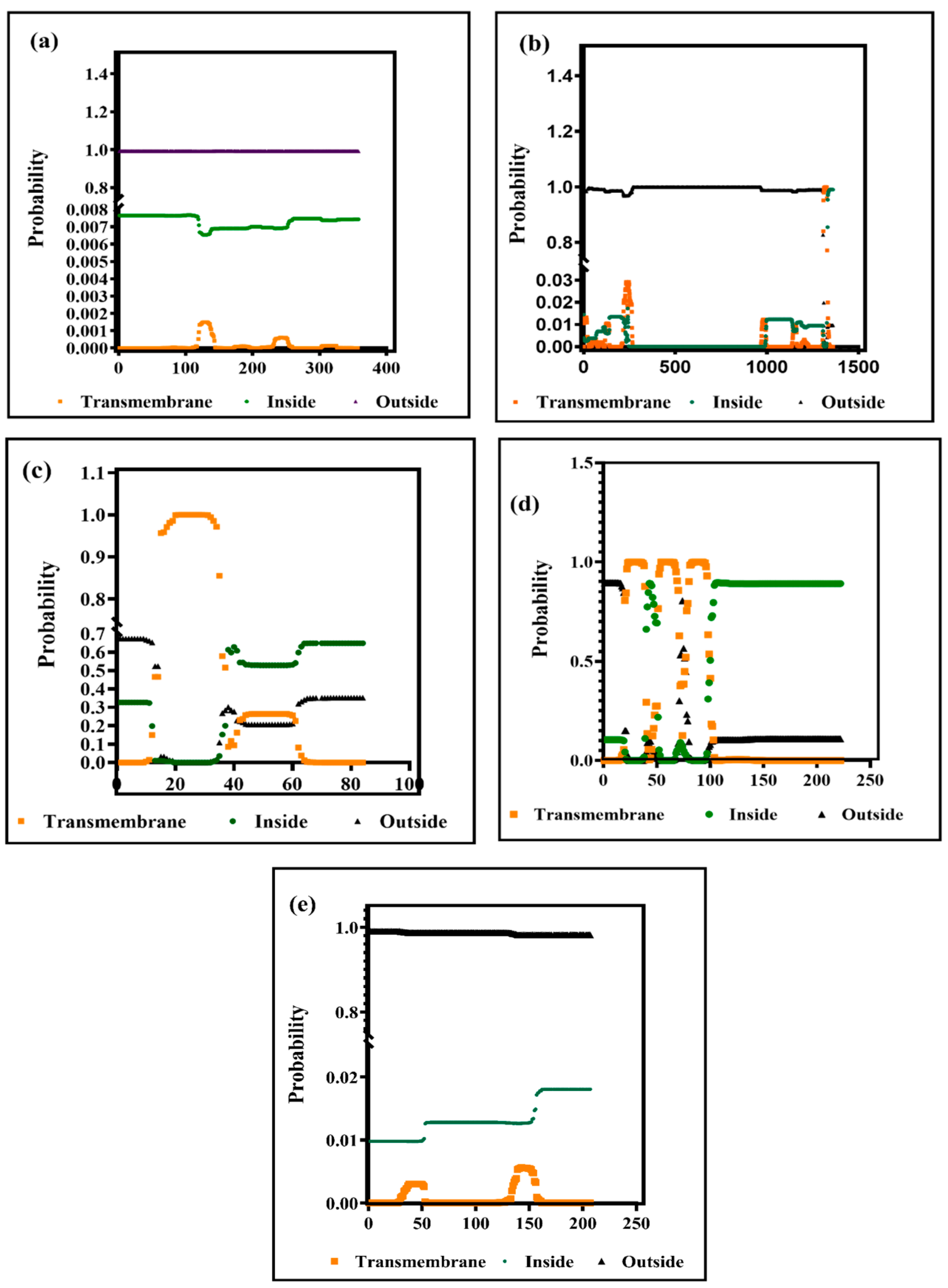

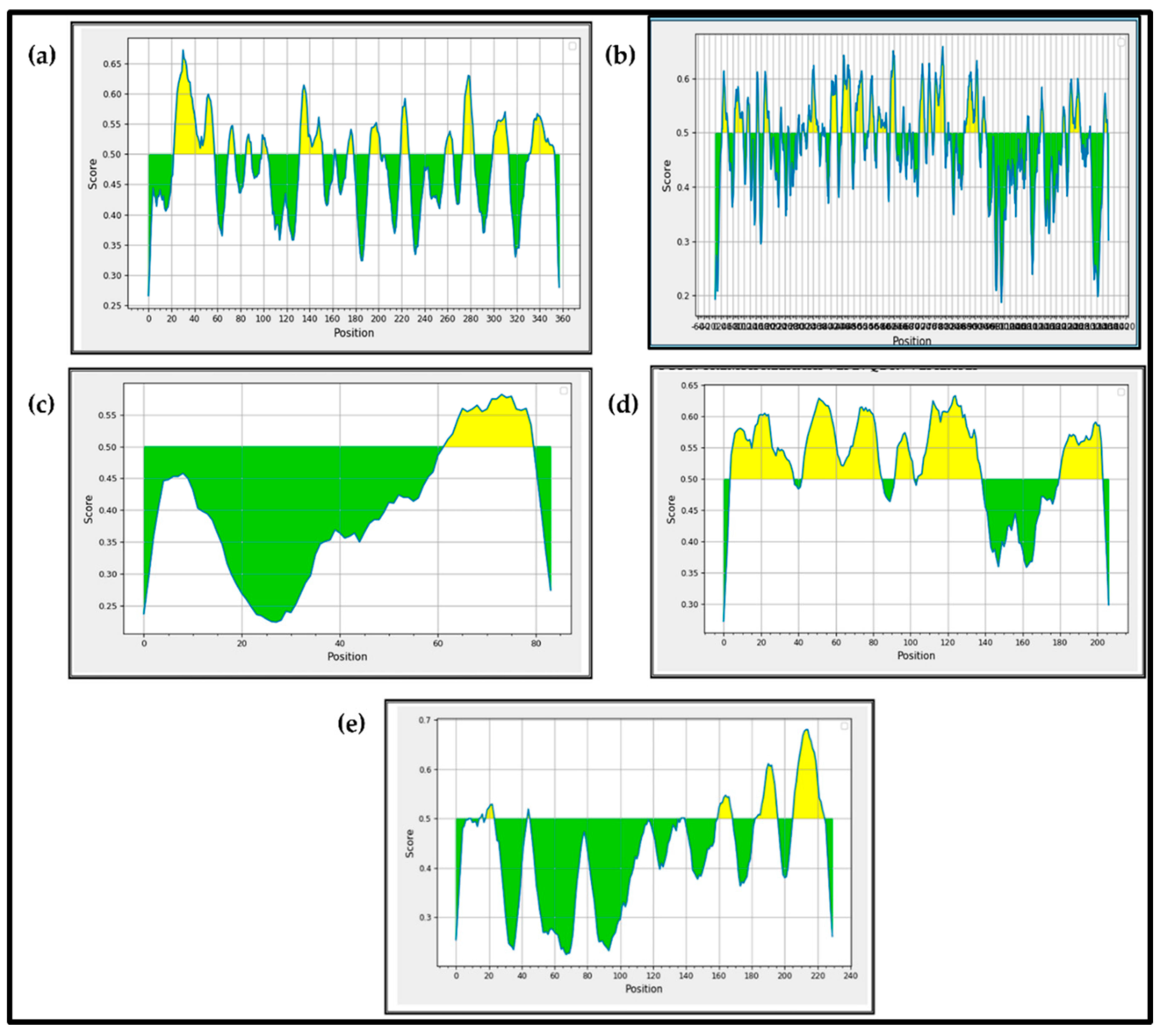

3.1. Prediction of the Secondary Structures of the BCoV Major Structural Proteins

3.2. Prediction of B Cell and T Cell (MHC Class I and MHC Class II) Epitopes within the BCoV Major Structural Proteins

3.2.1. The B Cell Epitopes Prediction and Assessment

3.2.2. Prediction of the T Cell Epitopes within the BCoV Major Structural Proteins and Their Binding/Interaction with the MHC -I and the MHC-II Proteins.

3.2.2.1. Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Epitope Identification and Evaluation (CTL):

3.2.2.2. Prediction of the Putative T Helper-Cell Epitopes (HTL) within the Major BCoV Structural Proteins:

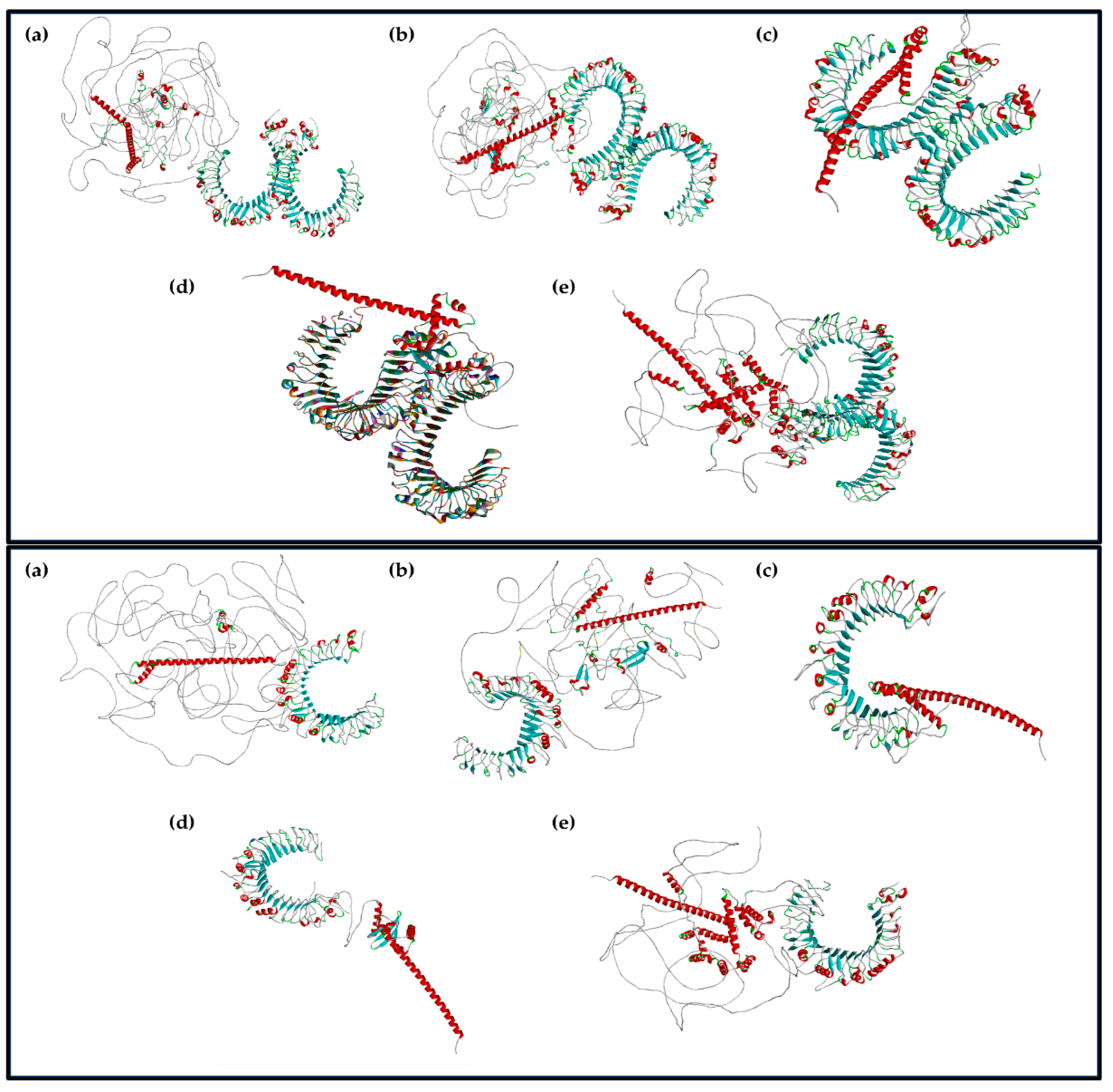

3.3. Homology Modeling and Epitope Visualization of the Potential Vaccine Candidates Based on the Identified Epitopes from the Major BCoV Structural Proteins.

3.3.1. Designing of the Potential Vaccine Constructs Based on the Identified Epitopes in the Major Structural Proteins of the BCoV and Their Conjugation with the Adjuvants.

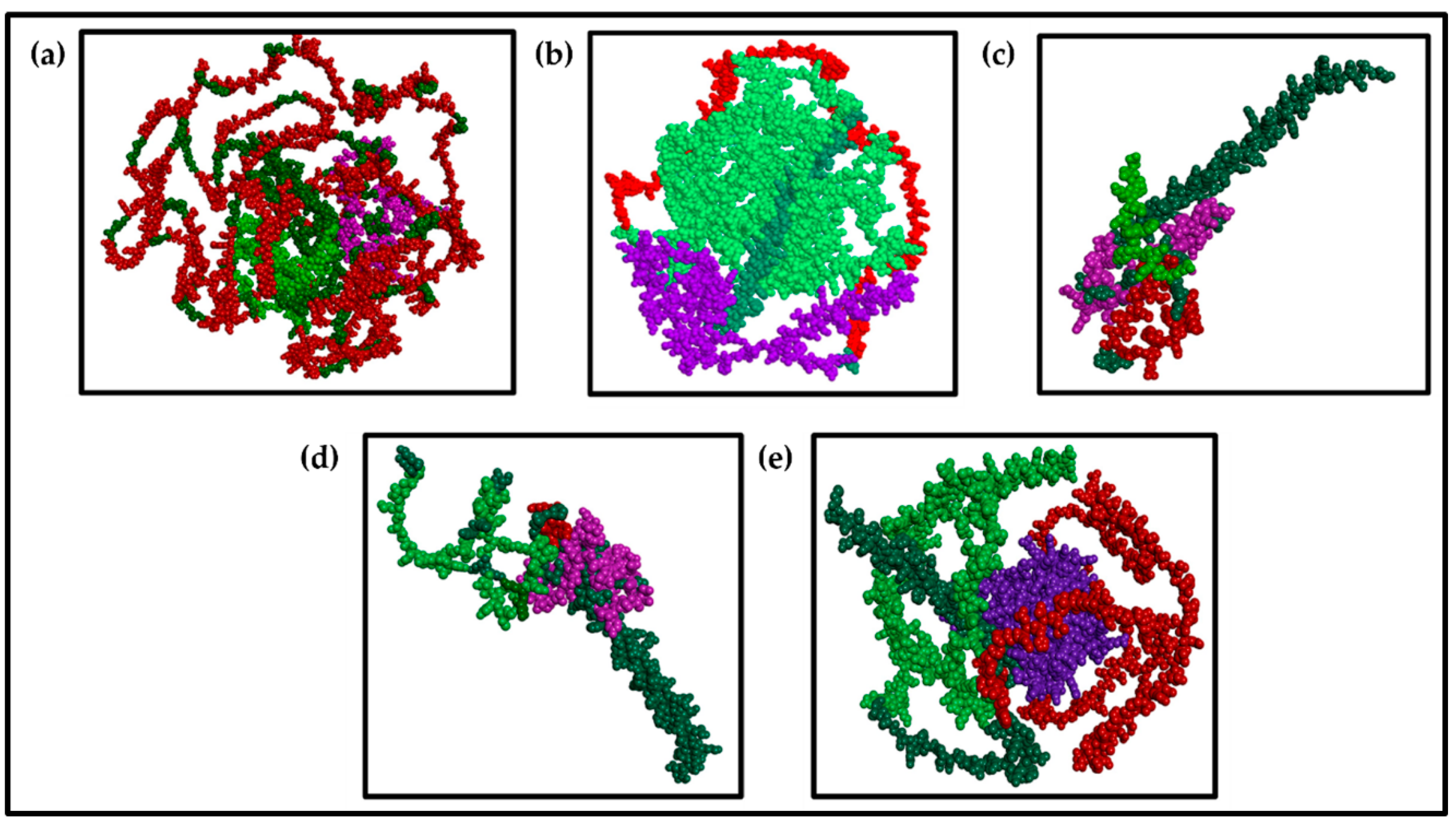

3.3.2. Prediction of the 3D Structures of the Designed Multi-Epitope-Based Vaccines for the Major Structural Proteins of BCoV

3.3.3. Visualization of the Multiepitope (B-Cell, CTL, and HTL of T-Cell) of the Major BCoV Structural Proteins

3.4. Results of the Molecular Docking of the Designed BCoV Vaccine Constructs with the Immunoreceptors (TLR2 and TLR4).

3.5. In-Silico Immune Simulation

3.6. The Codon Optimization and In-Silico Cloning of the BCoV Multi-Epitope-Based Vaccines Based on the Individual Structural Proteins:

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saif, L.J. Bovine respiratory coronavirus. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2010, 26, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, B.; Sun, D. Advances in Bovine Coronavirus Epidemiology. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakebrough-Hall, C.; Hick, P.; Mahony, T.J.; Gonzalez, L.A. Factors associated with bovine respiratory disease case fatality in feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanthrige-Don, N.; Lung, O.; Furukawa-Stoffer, T.; Buchanan, C.; Joseph, T.; Godson, D.L.; Gilleard, J.; Alexander, T.; Ambagala, A. A novel multiplex PCR-electronic microarray assay for rapid and simultaneous detection of bovine respiratory and enteric pathogens. J. Virol. Methods 2018, 261, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmageed, M.I.; Abdelmoneim, A.H.; Mustafa, M.I.; Elfadol, N.M.; Murshed, N.S.; Shantier, S.W.; Makhawi, A.M. Design of a Multiepitope-Based Peptide Vaccine against the E Protein of Human COVID-19: An Immunoinformatics Approach. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 2683286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arwansyah, A.; Arif, A.R.; Kade, A.; Taiyeb, M.; Ramli, I.; Santoso, T.; Ningsih, P.; Natsir, H.; Tahril, T.; Uday Kumar, K. Molecular modelling on multiepitope-based vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 using immunoinformatics, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2022, 33, 649–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Kancharla, S.; Kolli, P.; Jena, M. Reverse vaccinology approach towards the in-silico multiepitope vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2. F1000Res 2021, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Madan, R.; Singh, S. Immunology to Immunotherapeutics of SARS-CoV-2: Identification of Immunogenic Epitopes for Vaccine Development. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir Ul Qamar, M.; Rehman, A.; Tusleem, K.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Qasim, M.; Zhu, X.; Fatima, I.; Shahid, F.; Chen, L.L. Designing of a next generation multiepitope based vaccine (MEV) against SARS-COV-2: Immunoinformatics and in silico approaches. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0244176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umitaibatin, R.; Harisna, A.H.; Jauhar, M.M.; Syaifie, P.H.; Arda, A.G.; Nugroho, D.W.; Ramadhan, D.; Mardliyati, E.; Shalannanda, W.; Anshori, I. Immunoinformatics Study: Multi-Epitope Based Vaccine Design from SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Haider, A.; Rehman, A.; Qasim, M.; Umar, A.; Sufyan, M.; Akram, H.N.; Mir, A.; Razzaq, R.; Rasool, D.; et al. Immunoinformatics and Molecular Docking Studies Predicted Potential Multiepitope-Based Peptide Vaccine and Novel Compounds against Novel SARS-CoV-2 through Virtual Screening. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1596834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshafei, S.O.; Mahmoud, N.A.; Almofti, Y.A. Immunoinformatics, molecular docking and dynamics simulation approaches unveil a multi epitope-based potent peptide vaccine candidate against avian leukosis virus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafoor, D.; Zeb, A.; Ali, S.S.; Ali, M.; Akbar, F.; Ud Din, Z.; Ur Rehman, S.; Suleman, M.; Khan, W. Immunoinformatic based designing of potential immunogenic novel mRNA and peptide-based prophylactic vaccines against H5N1 and H7N9 avian influenza viruses. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 42, 3641–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.M.; Tong, G.Z.; Wang, Y.F.; Qiu, H.J. [Multi-epitope DNA vaccines against avian influenza in chickens]. Sheng Wu Gong. Cheng Xue Bao 2003, 19, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tataje-Lavanda, L.; Malaga, E.; Verastegui, M.; Mayta Huatuco, E.; Icochea, E.; Fernandez-Diaz, M.; Zimic, M. Identification and evaluation in-vitro of conserved peptides with high affinity to MHC-I as potential protective epitopes for Newcastle disease virus vaccines. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Wang, H.N.; Lu, D.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, T.; Kang, R.M. The immunoreactivity of a chimeric multi-epitope DNA vaccine against IBV in chickens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 377, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Ma, X.; Wang, F.; Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, X. Design and construction of a chimeric multi-epitope gene as an epitope-vaccine strategy against ALV-J. Protein Expr. Purif. 2015, 106, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanami, S.; Nazarian, S.; Ahmad, S.; Raeisi, E.; Tahir Ul Qamar, M.; Tahmasebian, S.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Fazeli, M.; Ghatreh Samani, M. In silico design and immunoinformatics analysis of a universal multi-epitope vaccine against monkeypox virus. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0286224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cia, G.; Pucci, F.; Rooman, M. Critical review of conformational B-cell epitope prediction methods. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Vasquez, V.; Calvay-Sanchez, K.D.; Zarate-Sulca, Y.; Mendoza-Mujica, G. In-silico identification of linear B-cell epitopes in specific proteins of Bartonella bacilliformis for the serological diagnosis of Carrion's disease. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, F.; Nain, Z.; Hossain, M.M.; Syed, S.B.; Ahmed Khan, M.S.; Adhikari, U.K. A comprehensive screening of the whole proteome of hantavirus and designing a multi-epitope subunit vaccine for cross-protection against hantavirus: Structural vaccinology and immunoinformatics study. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 150, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hoque, M.N.; Islam, M.R.; Akter, S.; Rubayet Ul Alam, A.S.M.; Siddique, M.A.; Saha, O.; Rahaman, M.M.; Sultana, M.; Crandall, K.A.; et al. Epitope-based chimeric peptide vaccine design against S, M and E proteins of SARS-CoV-2, the etiologic agent of COVID-19 pandemic: an in silico approach. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, D.; Mohan, M. Immunoinformatics-driven approach for development of potential multi-epitope vaccine against the secreted protein FlaC of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Shahid, F.; Butt, T.T.; Awan, F.M.; Ali, A.; Malik, A. Designing Multi-Epitope Vaccines to Combat Emerging Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) by Employing Immuno-Informatics Approach. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumchan, A.; Proespraiwong, P.; Sawatdichaikul, O.; Phurahong, T.; Hirono, I.; Unajak, S. Computational design of novel chimeric multiepitope vaccine against bacterial and viral disease in tilapia (Oreochromis sp.). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleri, W.; Vaughan, K.; Salimi, N.; Vita, R.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. The Immune Epitope Database: How Data Are Entered and Retrieved. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 5974574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.; Jain, A.; Verma, S.K. Prediction of Epitope based Peptides for Vaccine Development from Complete Proteome of Novel Corona Virus (SARS-COV-2) Using Immunoinformatics. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 1729–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Fei, C. A Highly Effective System for Predicting MHC-II Epitopes With Immunogenicity. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 888556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, B.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooft, R.W.; Sander, C.; Vriend, G. Objectively judging the quality of a protein structure from a Ramachandran plot. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997, 13, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, M.; Amini-Khoei, H.; Tahmasebian, S.; Ghatrehsamani, M.; Ghatreh Samani, K.; Edalatpanah, Y.; Rostampur, S.; Salehi, M.; Ghasemi-Dehnoo, M.; Azadegan-Dehkordi, F.; et al. Designing a novel multi-epitope vaccine against Ebola virus using reverse vaccinology approach. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapin, N.; Lund, O.; Bernaschi, M.; Castiglione, F. Computational immunology meets bioinformatics: the use of prediction tools for molecular binding in the simulation of the immune system. PLoS One 2010, 5, e9862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Sood, D.; Chandra, R. Design and optimization of a subunit vaccine targeting COVID-19 molecular shreds using an immunoinformatics framework. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 35856–35872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Bogdan, P.; Nazarian, S. An in silico deep learning approach to multi-epitope vaccine design: a SARS-CoV-2 case study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, T.; Narsaria, U.; Basak, S.; Deb, D.; Castiglione, F.; Mueller, D.M.; Srivastava, A.P. A candidate multi-epitope vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevinc Temizkan, S.; Alkan, F. Bovine coronavirus infections in Turkey: molecular analysis of the full-length spike gene sequences of viruses from digestive and respiratory infections. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, F.; Raisi, A.; Pourali, G.; Razavi, Z.S.; Ravaei, F.; Sadri Nahand, J.; Kourkinejad-Gharaei, F.; Mirazimi, S.M.A.; Zamani, J.; Tarrahimofrad, H.; et al. A computational approach to design a multiepitope vaccine against H5N1 virus. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.; Savytskyi, O.V.; Coban, M.; Venugopal, A.; Pleqi, V.; Weber, C.A.; Chitale, R.; Durvasula, R.; Hopkins, C.; Kempaiah, P.; et al. Protein structure-based in-silico approaches to drug discovery: Guide to COVID-19 therapeutics. Mol. Aspects Med. 2023, 91, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.Y. Khan, N.D., A. M.Y. Khan, N.D., A.U. Shah, R.N. ElAlaoui, M. Cherkaoui, M.G. Hemida, Identification of Some Potential Cellular Receptors and Host Enzymes That Could Potentially Refine the Bovine Coronavirus (BCoV) Replication and Tissue Tropism. A Molecular Docking Study, (2024).

- Kaur, B.; Karnwal, A.; Bansal, A.; Malik, T. An Immunoinformatic-Based In Silico Identification on the Creation of a Multiepitope-Based Vaccination Against the Nipah Virus. Biomed. Res. Int. 2024, 2024, 4066641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathollahi, M.; Motamedi, H.; Hossainpour, H.; Abiri, R.; Shahlaei, M.; Moradi, S.; Dashtbin, S.; Moradi, J.; Alvandi, A. Designing a novel multi-epitopes pan-vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal influenza: in silico and immunoinformatics approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sami, S.A.; Marma, K.K.S.; Mahmud, S.; Khan, M.A.N.; Albogami, S.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Rakib, A.; Chakraborty, A.; Mohiuddin, M.; Dhama, K.; et al. Designing of a Multi-epitope Vaccine against the Structural Proteins of Marburg Virus Exploiting the Immunoinformatics Approach. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 32043–32071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi, B.; Molaei, A.; Fard, N.A. Multi-epitopevaccines, from design to expression; an in silico approach. Hum. Immunol. 2024, 85, 110804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, S.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yao, H.; Liu, G. Combined Immunoinformatics to Design and Evaluate a Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate against Streptococcus suis Infection. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornbluth, R.S.; Stone, G.W. Immunostimulatory combinations: designing the next generation of vaccine adjuvants. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 80, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopp, M.T.; Holze, J.; Lauber, F.; Holtkamp, L.; Rathod, D.C.; Miteva, M.A.; Prestes, E.B.; Geyer, M.; Manoury, B.; Merle, N.S.; et al. Insights into the molecular basis and mechanism of heme-triggered TLR4 signalling: The role of heme-binding motifs in TLR4 and MD2. Immunology 2024, 171, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.J.I.; Hossain, M.F.; Neef, J.; Zwack, E.E.; Tsai, C.M.; Raafat, D.; Fechtner, K.; Herzog, L.; Kohler, T.P.; Schluter, R.; et al. TLR4 sensing of IsdB of Staphylococcus aureus induces a proinflammatory cytokine response via the NLRP3-caspase-1 inflammasome cascade. mBio 2024, 15, e0022523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Wu, K.H.; Wu, H.P. Unraveling the Complexities of Toll-like Receptors: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladipo, E.K.; Ojo, T.O.; Olufemi, S.E.; Irewolede, B.A.; Adediran, D.A.; Abiala, A.G.; Hezekiah, O.S.; Idowu, A.F.; Oladeji, Y.G.; Ikuomola, M.O.; et al. Proteome based analysis of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants: approach to a universal vaccine candidate. Genes. Genomics 2023, 45, 1489–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raoufi, E.; Hemmati, M.; Eftekhari, S.; Khaksaran, K.; Mahmodi, Z.; Farajollahi, M.M.; Mohsenzadegan, M. Epitope Prediction by Novel Immunoinformatics Approach: A State-of-the-art Review. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2020, 26, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurina, V.; Adianingsih, O.R. Predicting epitopes for vaccine development using bioinformatics tools. Ther. Adv. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 10, 25151355221100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, A.; Akhtar, N.; Sharma, N.R.; Kaushik, V.; Borkotoky, S. MERS virus spike protein HTL-epitopes selection and multi-epitope vaccine design using computational biology. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 12464–12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | B-cell epitope Sequence |

|---|---|

| HE | RSDCNHVVNTNPRNYSYMDLNPALCDSGKISSKAGNNYTGEGNFTPYSNDIWVYNGSAQSTALCKSGSLVLNFYLSGCFLSNTKYYDDTETITTGFLNKRKDFRWNNARQSDNMTNYVGVYDINHGDAQQGVFRYDNVSSVWPLYSYGRCP |

| S | VSINDVDTGAPSISTDIVDVTNYPTSGSTYRNMALKGTLLLSRLWFKPPFLSDTKVIKKGVMYSTTNLDNKLQHTICHPNLGNKRVELWHWDTGKSDFMSIAPSTGVYEDVYRRIPNLPDCNIEAWLNDKSVPSPLNWERKTFSNCNFGRKVDLQLGNLGYLQSFNYRIDTTVSVSRFNPSTWNRRFGFTEQFVFKPQPVGVFTHHDFCPCKLDGSLCVGNGPGIDAGYKNSGIGTCLCTPDPITSKSTGPYKCPQSGLAIKSDYCGGNPCTCQPQAFLGWSVDSCLQGHDVNSGTTCSTDLQKSNTDIATYYNSDYLTNKCNYVFNNTLSRQLQPINYFADNSTSSVVQTCDLTDYSTKRRSRRAITTGYRFTTFEPFTVNSVNDSLEPVGGDTTQLQVANSLMNGVTLSTKLKDGVNFNVDDINFSPVLGCLGSDCNKVSSRLSDVGFVEAYNNLEAQAQIDKSQSSRINFCGYYYPEPITGNKAPDVMLNISTPNLHDFKEELDQWFKNQTSVAPDLSLDYICDDYTGHQELVIKT |

| E | RGRQFYEFYNDVKPPVLD |

| M | IKFLKELGTGYSLSDTYKRGFLDKIGDTKVGNYRLPSTQKGSGMDTAL |

| N | SGPISPTNLEMFKPGVEELNPSKLLLLSYHQEGMILGSLELLSFKKERSLNLQRDKVCLLHQESQLLKLRGTGTDTTMATSVNCCHDFTILEQDRMPKTSMAPILTESSGSLVTRLMSIPRLLHAHPVEPLVQDRVVEPILATEP |

| Protein | Final Vaccine Construct |

|---|---|

| HE | MSNTCDEKTQSLGVKFLDEYQSKVKRQIFSGYQSDIDTHNRIKDELEAAAKAKFVAAWTLKAAAAAYALCDSGKISSKAAYAQSTALCKAAYFLNKRKDFAAYFRYDNVSSVAAYNKRKDFRWAAYNNARQSDNMAAYRQSDNMTNYAAYRYDNVSSVWAAYSGKISSKAAAYSSKAGNNYAAYTTGFLNKRKAAYVNTNPRNYAAYALCDSGKISSKAGNNGPGPARQSDNMTNYVGVYDGPGPGCDSGKISSKAGNNYTGPGPGDAQQGVFRYDNVSSVGPGPGDDTETITTGFLNKRKGPGPGDFRWNNARQSDNMTNGPGPGDINHGDAQQGVFRYDGPGPGDLNPALCDSGKISSKGPGPGDSGKISSKAGNNYTGGPGPGDTETITTGFLNKRKDGPGPGFLNKRKDFRWNNARQGPGPGFRWNNARQSDNMTNYGPGPGCFLSNTKYYDDTETGPGPGGFLNKRKDFRWNNARGPGPGGKISSKAGNNYTGEGGPGPGISSKAGNNYTGEGNFGPGPGITTGFLNKRKDFRWNGPGPGKDFRWNNARQSDNMTGPGPGKISSKAGNNYTGEGNGPGPGKRKDFRWNNARQSDNGPGPGLNKRKDFRWNNARQSGPGPGLNPALCDSGKISSKAGPGPGMDLNPALCDSGKISSGPGPGNNARQSDNMTNYVGVGPGPGNNYTGEGNFTPYSNDGPGPGNPALCDSGKISSKAGGPGPGPALCDSGKISSKAGNGPGPGPRNYSYMDLNPALCDGPGPGRKDFRWNNARQSDNMGPGPGRNYSYMDLNPALCDSGPGPGRSDCNHVVNTNPRNYGPGPGSSKAGNNYTGEGNFTGPGPGSYMDLNPALCDSGKIGPGPGTGFLNKRKDFRWNNAGPGPGTITTGFLNKRKDFRWGPGPGTTGFLNKRKDFRWNNGPGPGVYDINHGDAQQGVFRGPGPGYDDTETITTGFLNKRGPGPGYDINHGDAQQGVFRYGPGPGYMDLNPALCDSGKISGPGPGYSYMDLNPALCDSGKKKRSDCNHVVNTNPRNYSYMDLNPALCDSGKISSKAGNKKNYTGEGKKNFTPYKKSNDIWKKVYNGSAQSTALCKSGSLVLNKKFYLSGCKKFLSNTKYYDDKKTETITTGFKKLNKRKDFKKRWNNARQSDNMKKTNYVGVYDINHGDAKKQQGVFRYDNVSSVWPLYSYGRCP |

| S | MSNTCDEKTQSLGVKFLDEYQSKVKRQIFSGYQSDIDTHNRIKDELEAAAKAKFVAAWTLKAAAAAYDKSVPSPLNWAAYKSQSSRINFAAYLGNKRVELWAAYLNDKSVPSPLNWAAYLSDTKVIKKAAYNDKSVPSPLNWAAYRNMALKGTLLWAAYRRFGFTEQFAAYSQSSRINFAAYSAKSDFMSIAAYSTTNLDNKLQHAAYTNLDNKLQHAAYYRNMALKGTLAAYTSKSTGPYKAAYTTNLDNKLQHGPGPGSDVGFVEAYNNLEAQGPGPGDVGFVEAYNNLEAQAGPGPGFEPFTVNSVNDSLEPGPGPGTFEPFTVNSVNDSLEGPGPGPEPITGNKAPDVMLNGPGPGYYPEPITGNKAPDVMKKVSINDVDTGAPSISTDIVDVTNKKYPTSGSTYRNMALKGTLLLSRLWFKPPFLSDKKTKVIKKGVMYSKKTTNLDNKLQKKHTICHPNLGNKRVELWHWDTGKKGVVTKKKSSAKKKSDFMSKKIAPSTGVYEKKDVYRRIPNLPDCNIEAWLNDKSVPSPLNWERKTFSNCNFKKAKKFTCNKKIKKAAKKKGRKVDLQLGNLGYLQSFNYRIDTTKKVSVSRFNPSTWNRRFGFTEQFVFKPQPVGVFTHHDKKFCPCKLDGSLCVGNGPGIDAGYKNSGIGTKKQKKCLCTPDPITSKSTGPYKCPQKKSGLAIKSDYCGGNPCTCQPQAFLGWSVDSCLQGKKHDVNSGTTCSTDLQKSNTDIKKATYYNSKKDYLTNKKSKKKCNYVFNNTLSRQLQPINYFKKADNSTSSVVQTCDLTKKDYSTKRRSRRAITTGYRFTTFEPFTVNSVNDSLEPVGGKKTIGKKDTTQLQVANSLMNGVTLSTKLKDGVNFNVDDINFSPVLGCLGSDCNKVSSRKKLSDVGFVEAYNNKKLEAQAQIDKKKSQSSRINFCGKKYYYPEPITGNKKKAPDVMLNISTPNLHDFKEELDQWFKNQTSVAPDLSLDYIKKIGTKKCDDYTGHQELVIKT |

| E | MSNTCDEKTQSLGVKFLDEYQSKVKRQIFSGYQSDIDTHNRIKDELEAAAKAKFVAAWTLKAAAAAYYNDVKPPVLAAYRGRQFYEFYAAYYNDVKPPVLAAYRQFYEFYNDVAAYNDVKPPVLGPGPGQFYEFYNDVKPPVLDGPGPGRGRQFYEFYNDVKPPKKRGRQFYEFYNDVKPPVLD |

| M | MSNTCDEKTQSLGVKFLDEYQSKVKRQIFSGYQSDIDTHNRIKDELEAAAKAKFVAAWTLKAAAAAYTQKGSGMDTALAAYTGYSLSDTYKAAYRGFLDKIGDTKAAYYSLSDTYKAAYFLKELGTGYAAYKELGTGYSLAAYDTKVGNYRLAAYKGSGMDTALAAYYSLSDTYKRGPGPGIKFLKEKKLGTGYSLSDKKTYKRGFLDKKIGDTKKKVGNYRLPSTQKGSGMDTALKK |

| N | MSNTCDEKTQSLGVKFLDEYQSKVKRQIFSGYQSDIDTHNRIKDELEAAAKAKFVAAWTLKAAAAAYLQRDKVCLLAAYGSLELLSFKAAYSLNLQRDKVCLLAAYRSLNLQRDKAAYRSLNLQRDKVCLLAAYLLSFKKERSLAAYLQRDKVCLLHAAYLSFKKERSLAAYEELNPSKLLAAYSLELSFKKERSLAAYGMILGSLELAAYLSFKKERSLAAYHPVEPLVQDRVAAYVEELNPSKLAAYFKKERSLNLAAYGVEELNPSKLLAAYLSFKKERSLGPGPGAHPVEPLVQDRVVEPGPGPGHAHPVEPLVQDRVVEGPGPGLLSFKKERSLNLQRDGPGPGSLNLQRDKVCLLHQEGPGPGIPRLLHAHPVEPLVQGPGPGRSLNLQRDKVCLLHQGPGPGLHAHPVEPLVQDRVVGPGPGLLSFKKERSLNLQRDGPGPGHDFTILEQDRMPKTSGPGPGSLNLQRDKVCLLHQEGPGPGLLSFKKERSLNLQRDGPGPGCHDFTILEQDRMPKTGPGPGELLSFKKERSLNLQRKKSGPISPTNLEMFKPGVEELNPSKLLLLSYHQEGMKKILGSLELLSFKKERSLNLQRDKVCLLHQESQLLKLRGTGTDTTKKMATSVNCCHDKKFTILEQDRMPKTSMAPILTESSGSLVTRLMSIPRLKKLHAHPVEPLVQDRVVEPILATEP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).