Submitted:

19 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

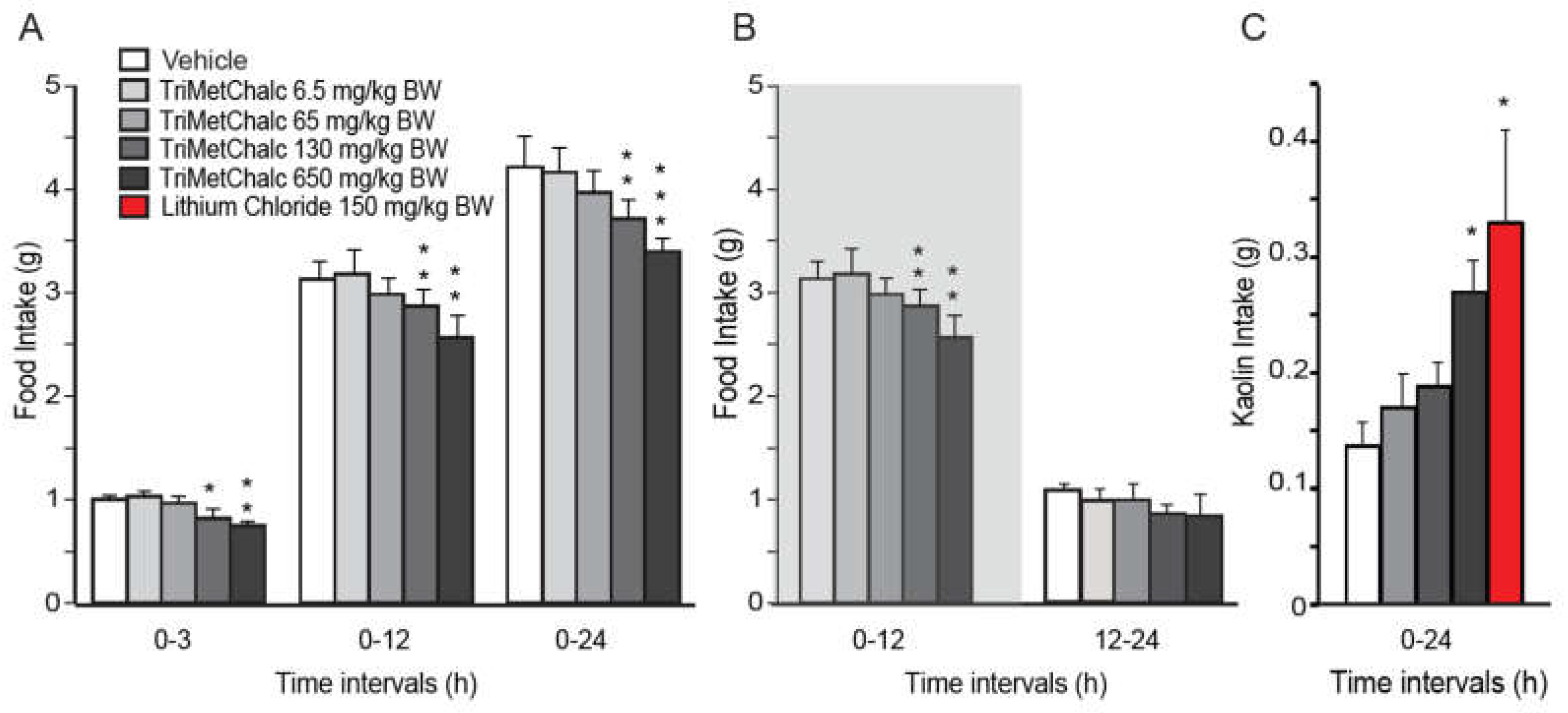

2.1. Effect of Acute Per Os Administration of TriMetChal on Food Intake in C57Bl/6 Mice

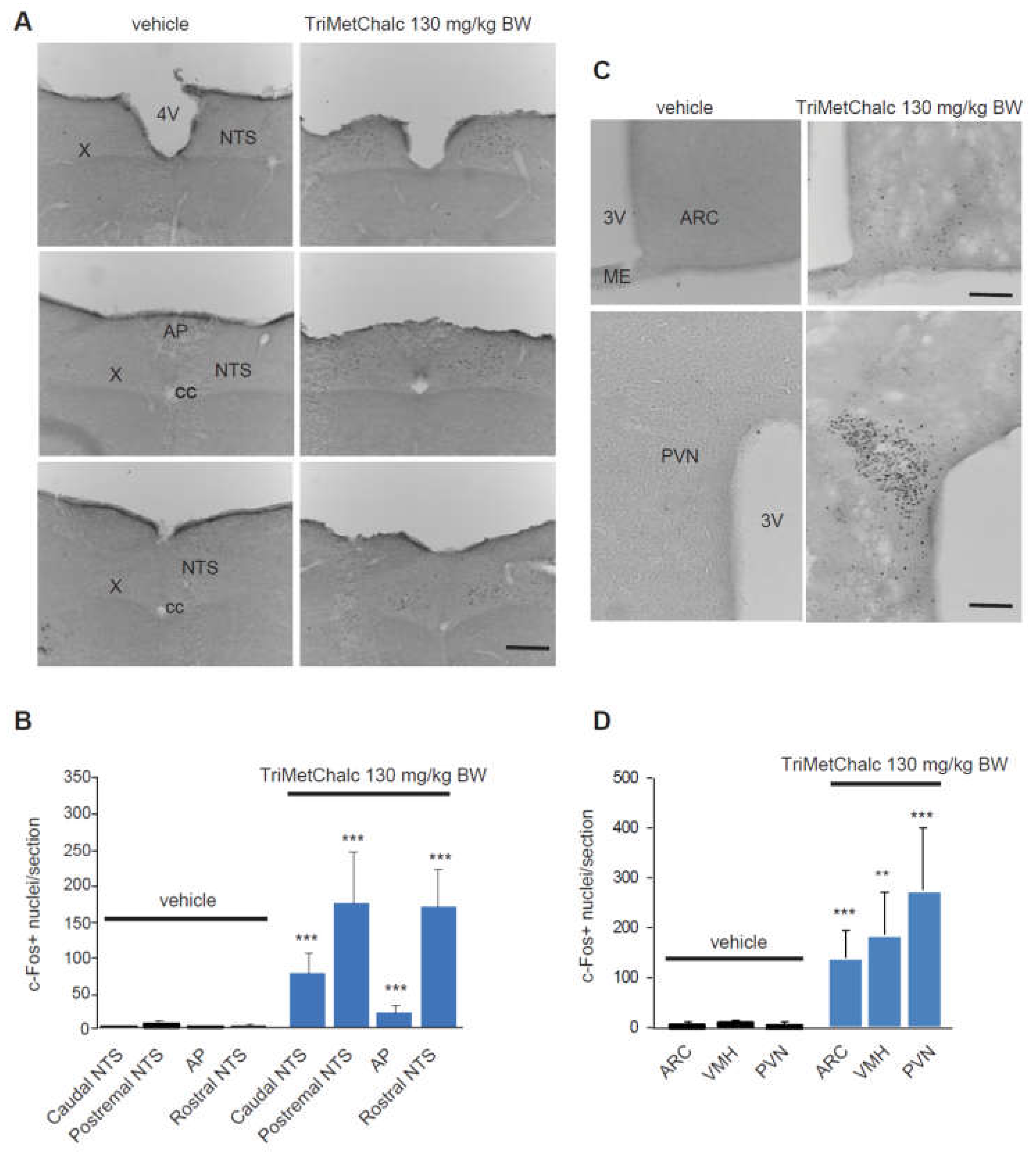

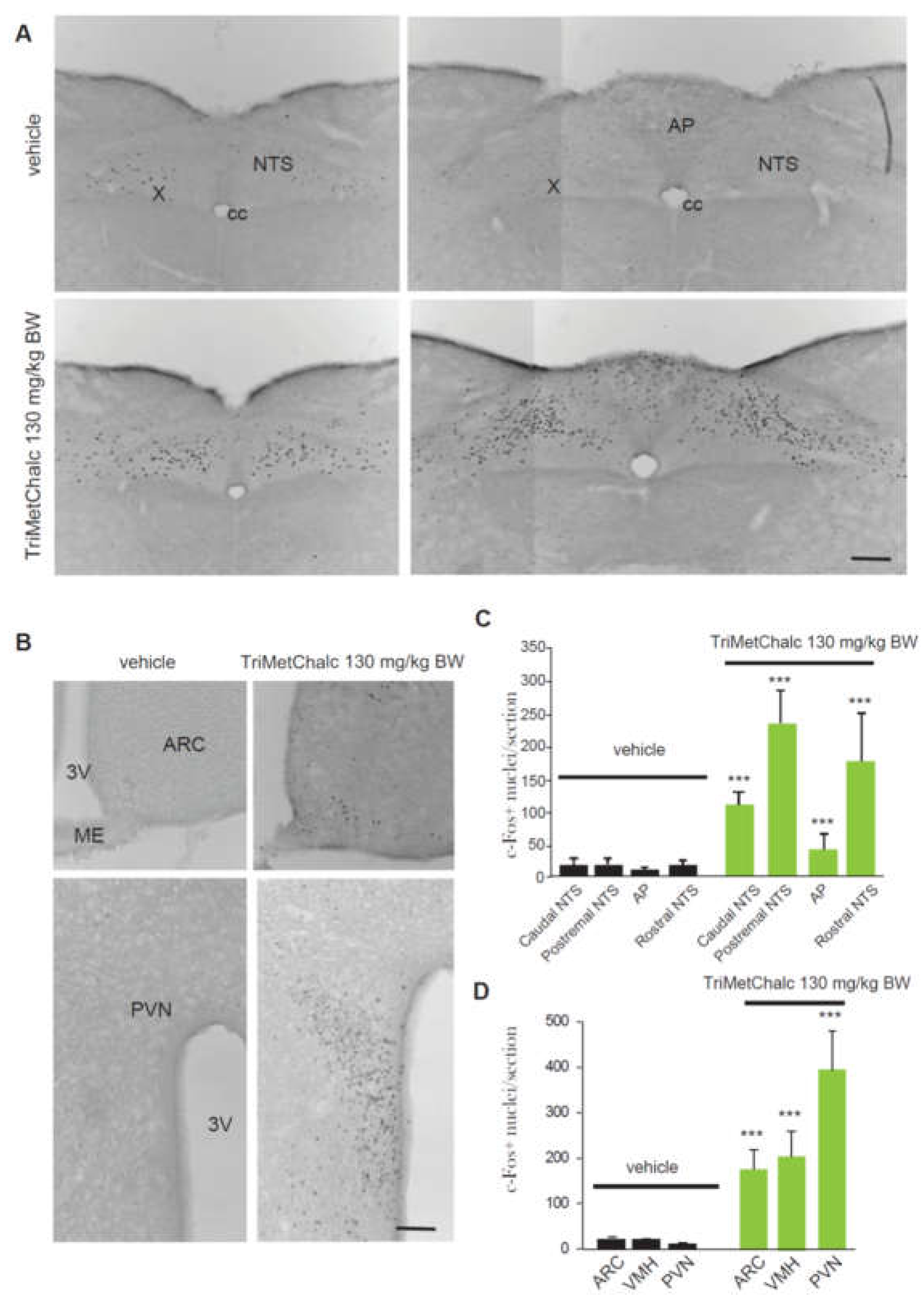

2.2. Brain Pattern of Central Pathways Activated in Response t Acute Trimetchalc Per Os Administration

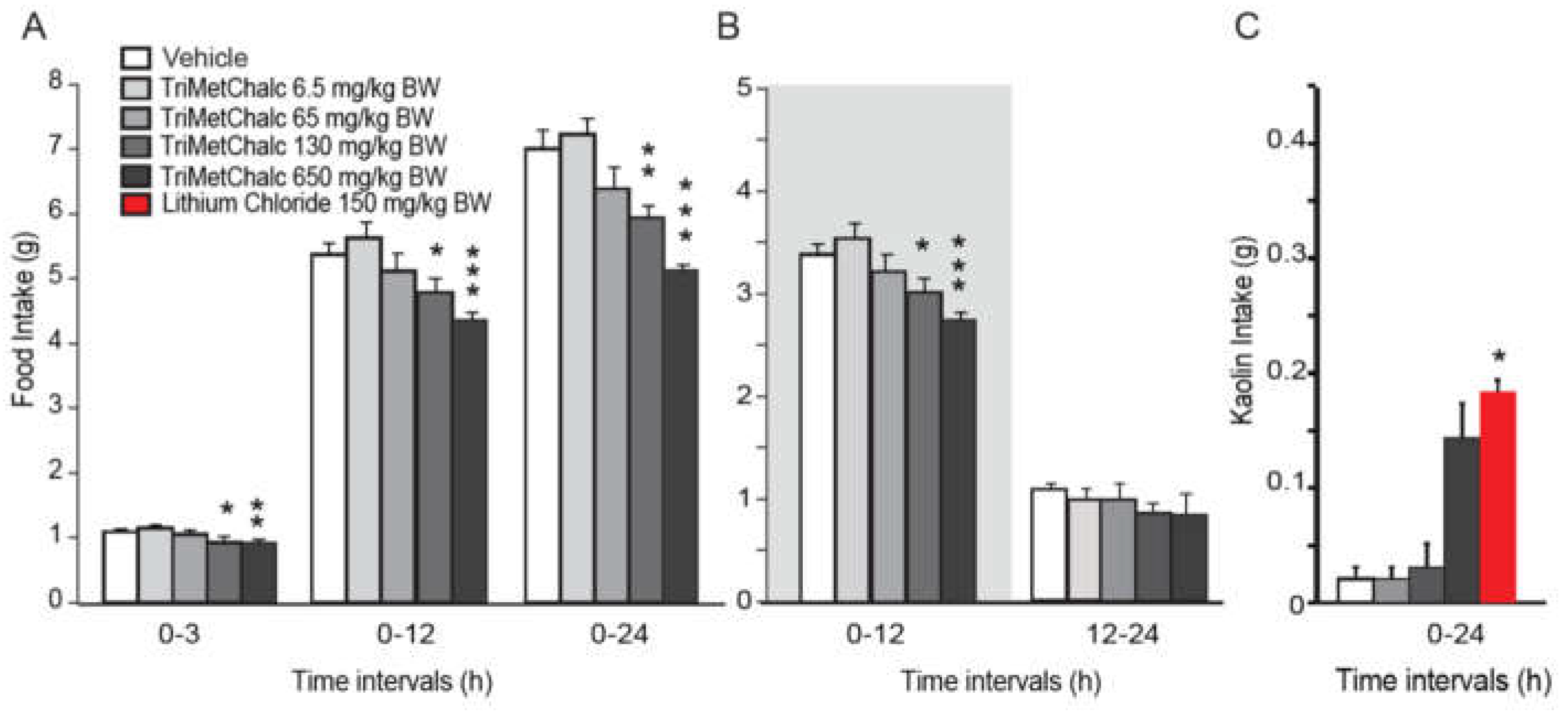

2.3. Effect of Acute Per Os Administration of TriMetChalc on Food Intake and c-Fos Expression in ob/ob Mice

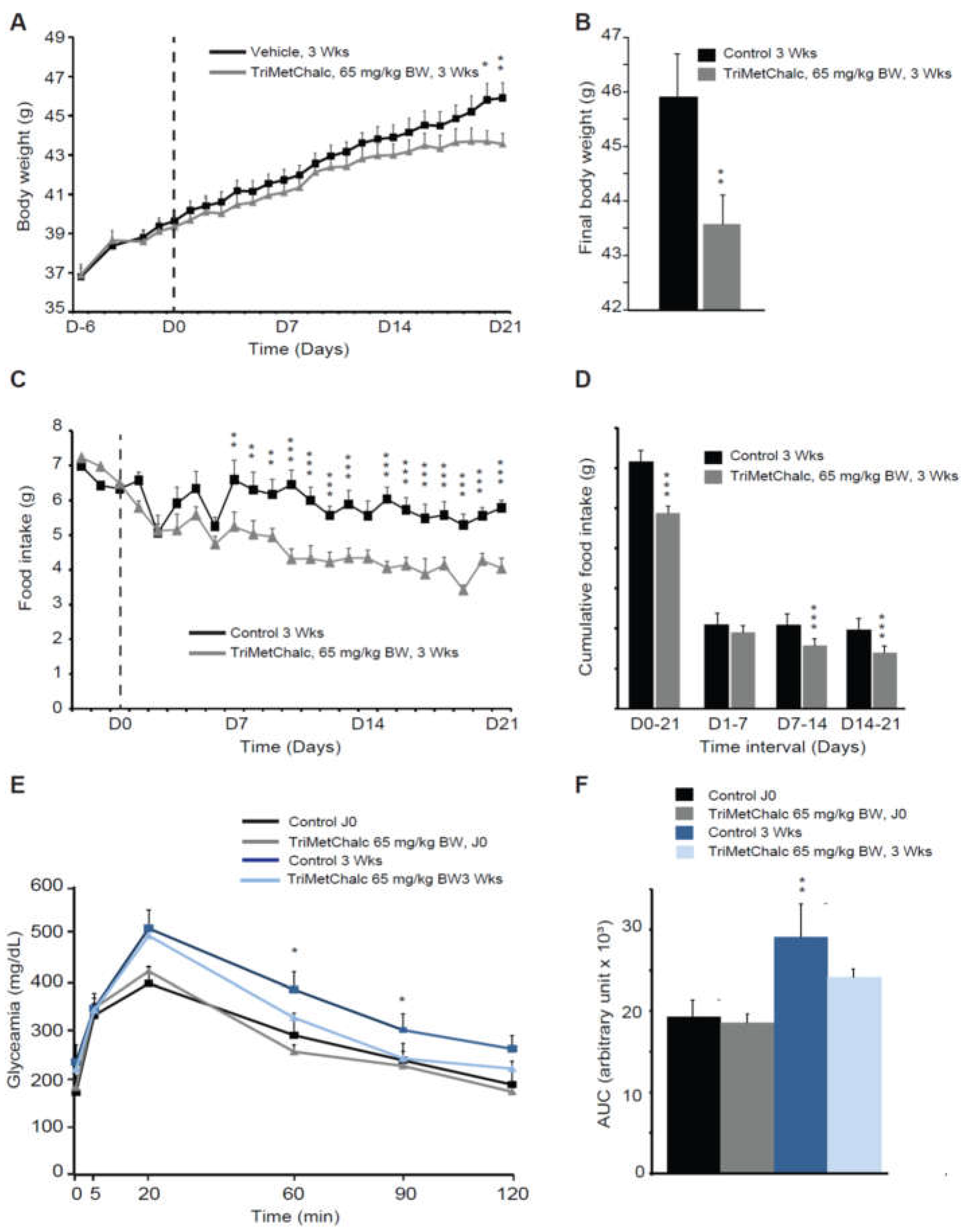

2.4. Effect of Chronic TriMetChalc Treatment on Food Intake and Body Weight of Leptin Deficient Mice

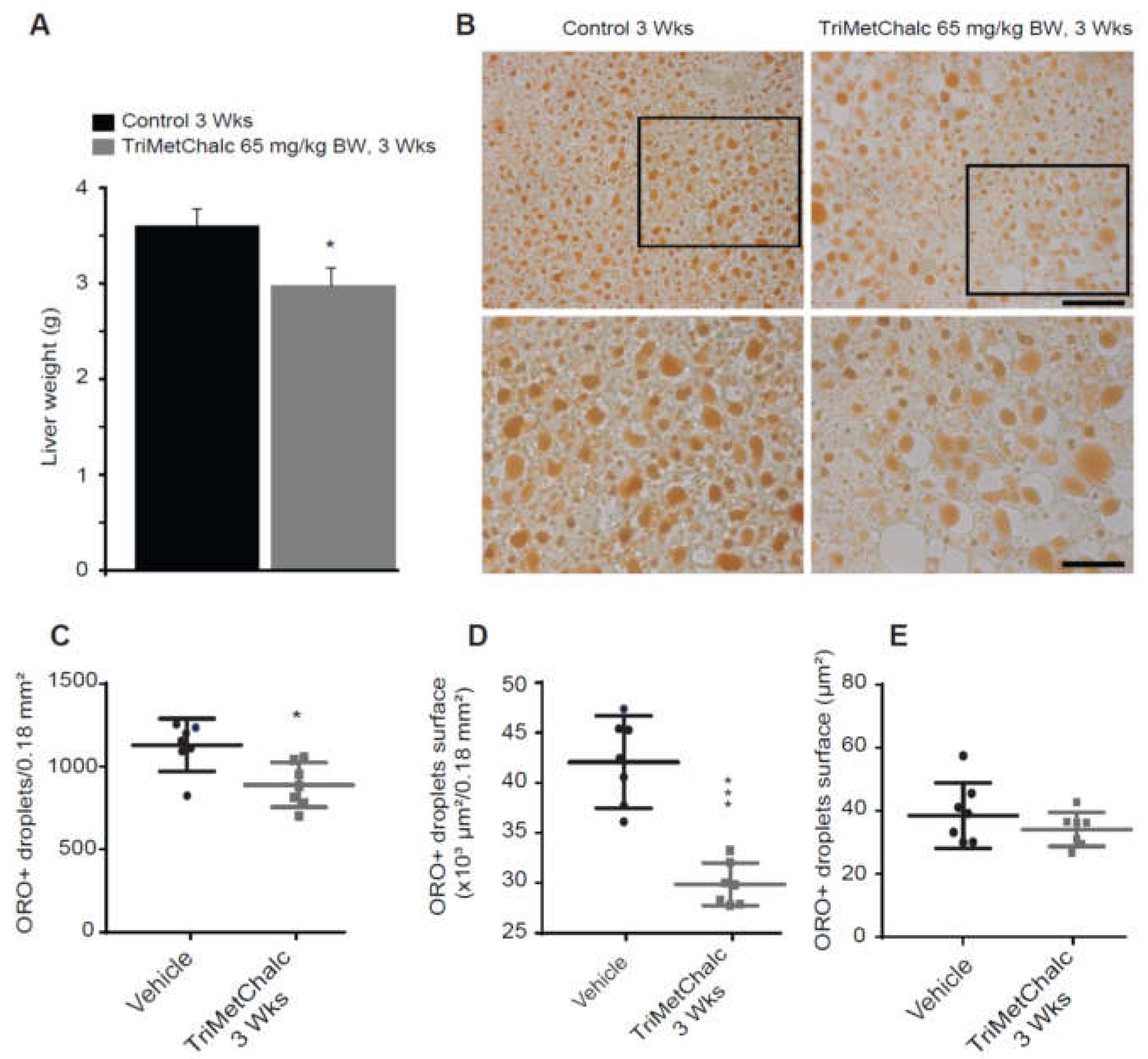

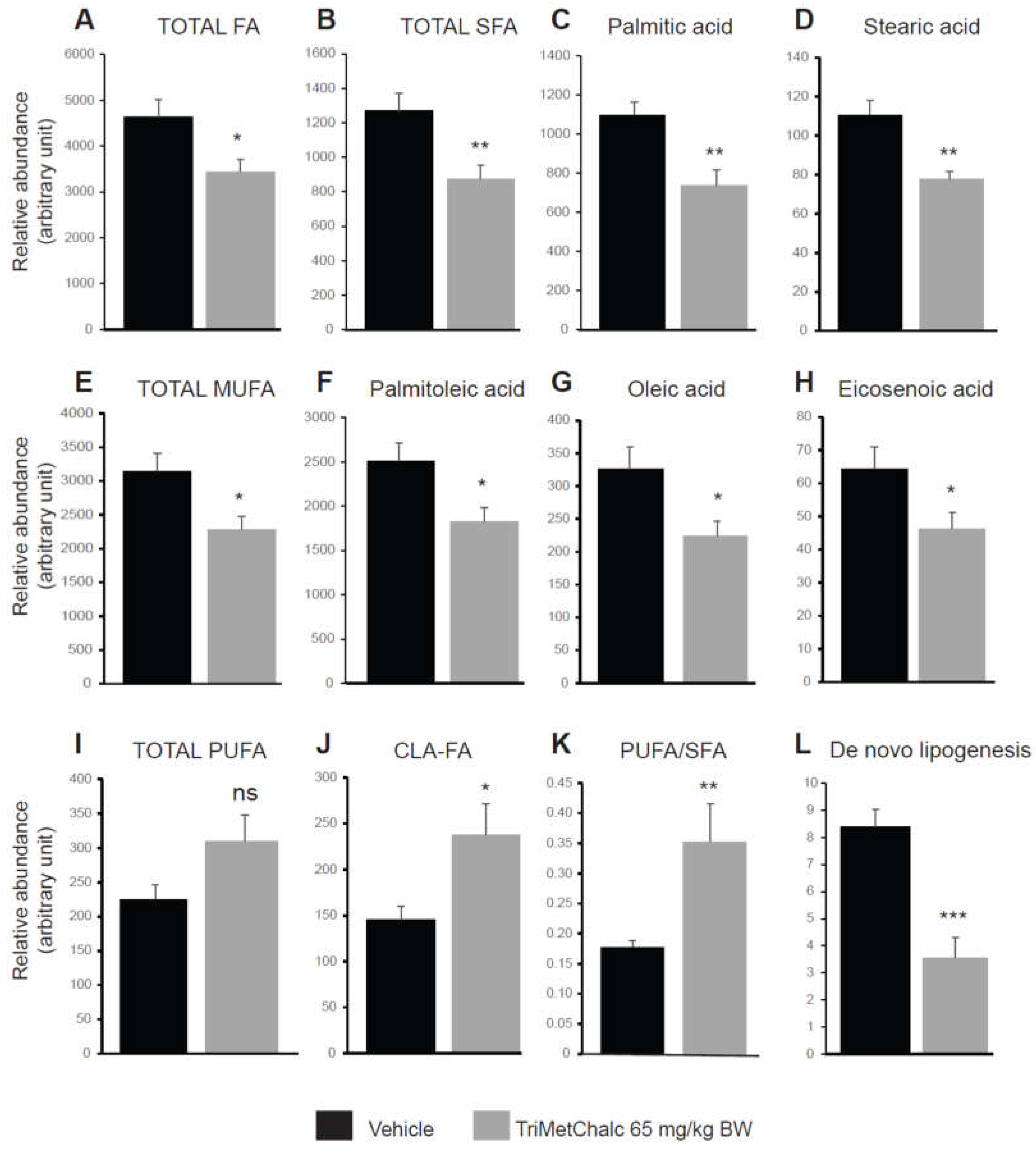

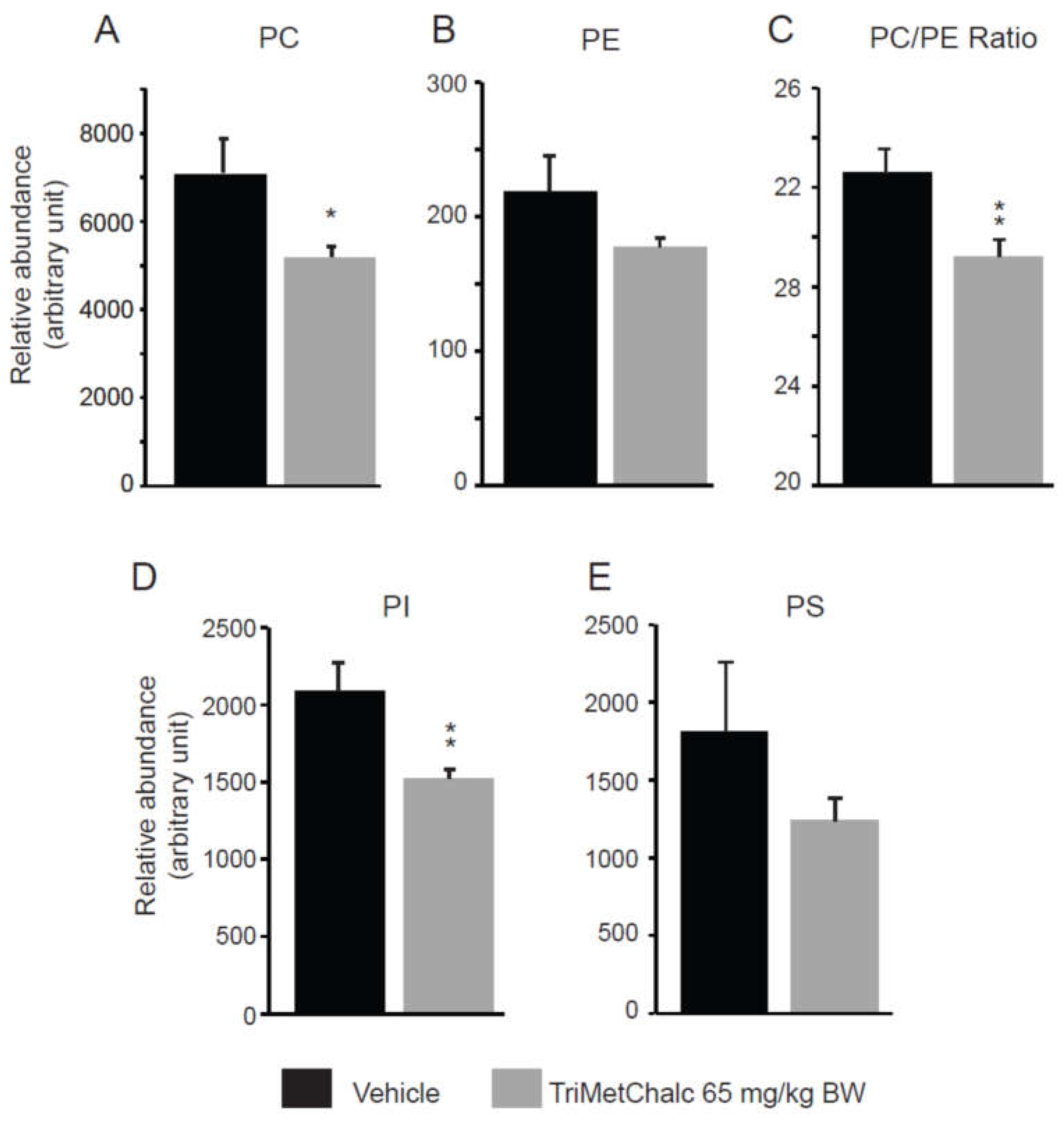

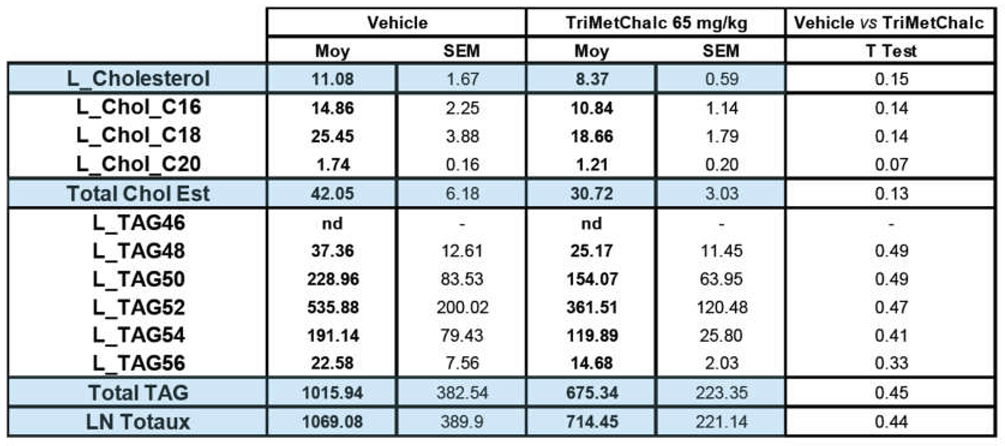

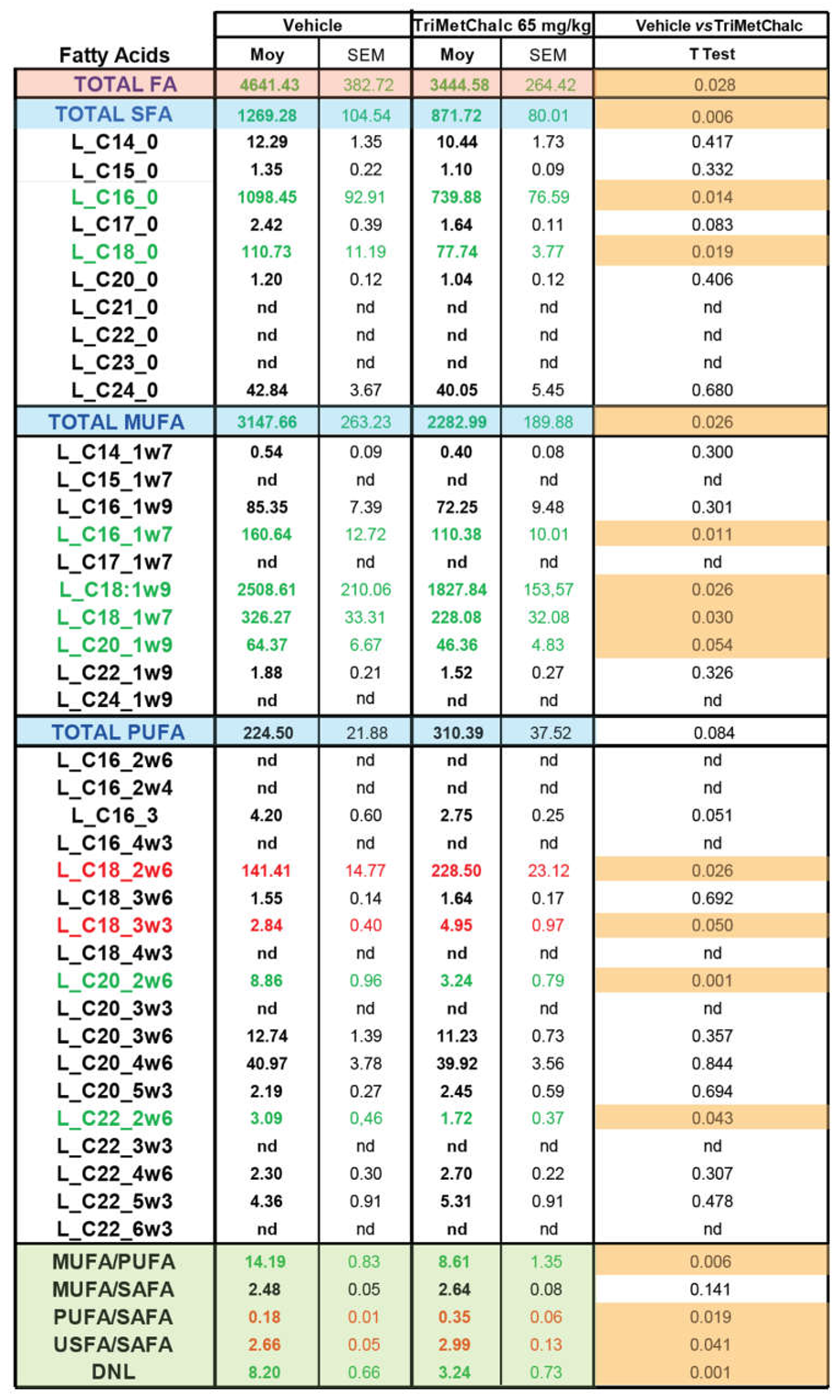

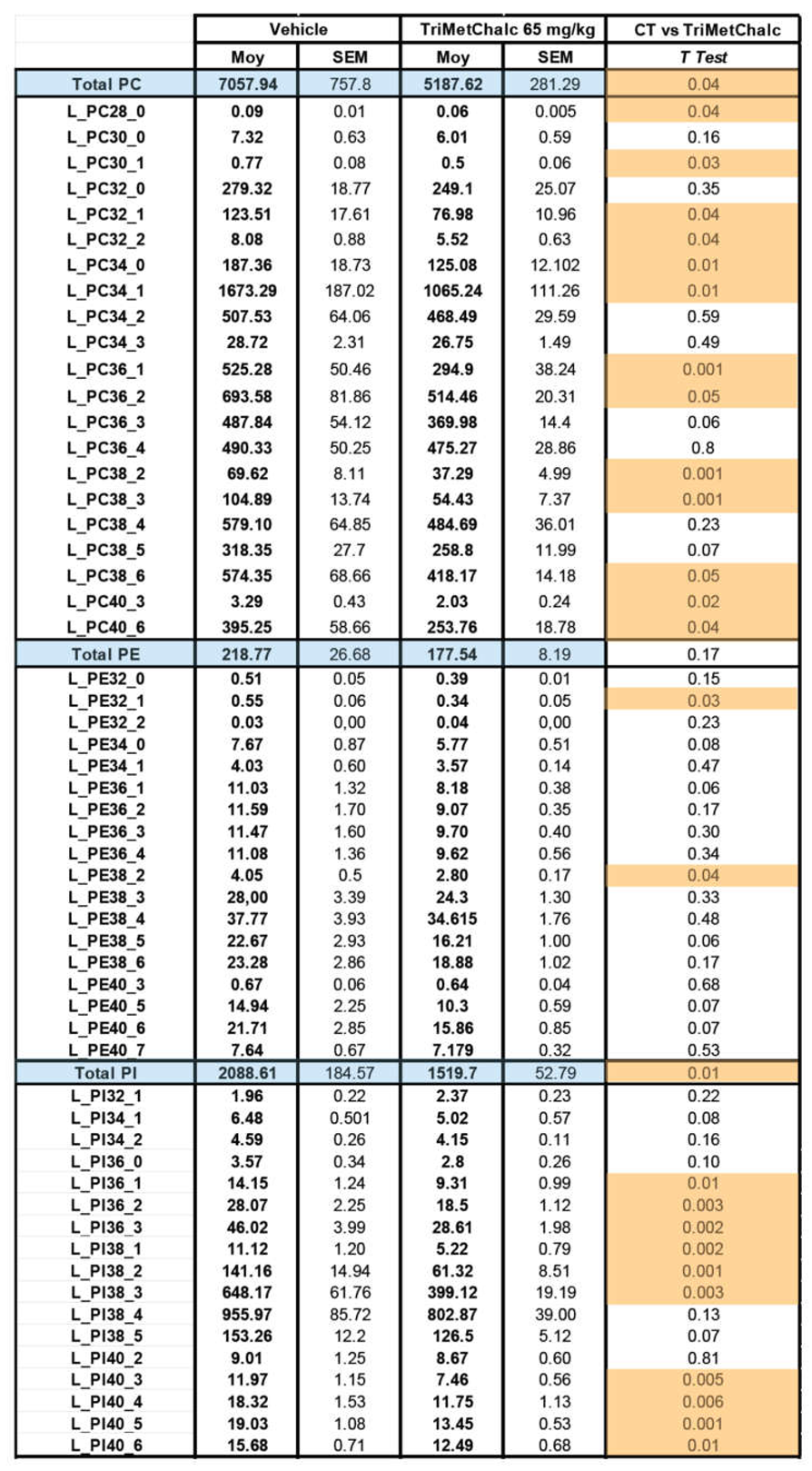

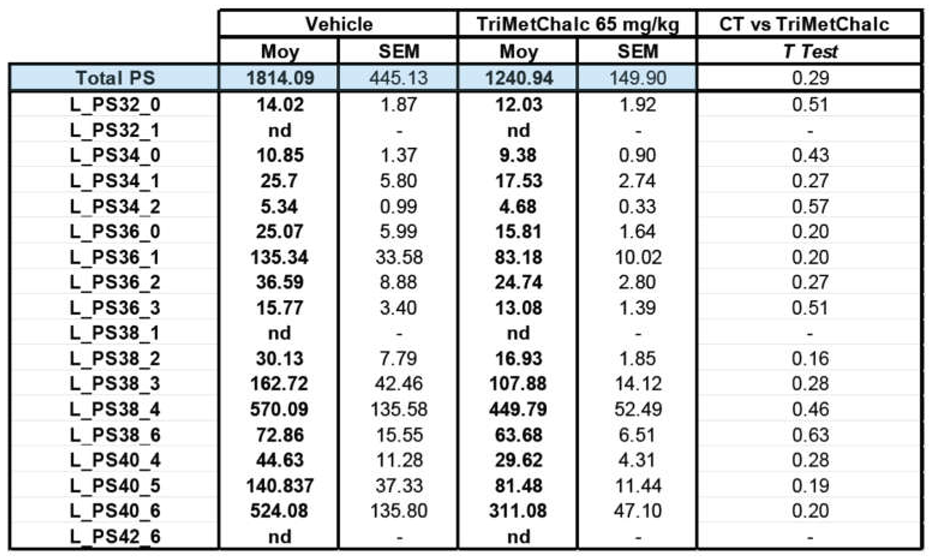

2.5. Effect of Chronic TriMetChalc Treatment on Hepatic Lipid Content of ob/ob Mice

3. Discussion

3.1. TriMetChalc Acts as Anorexigenic Molecule Independently of Leptin

3.2. TriMetChalc Attenuates Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Housing

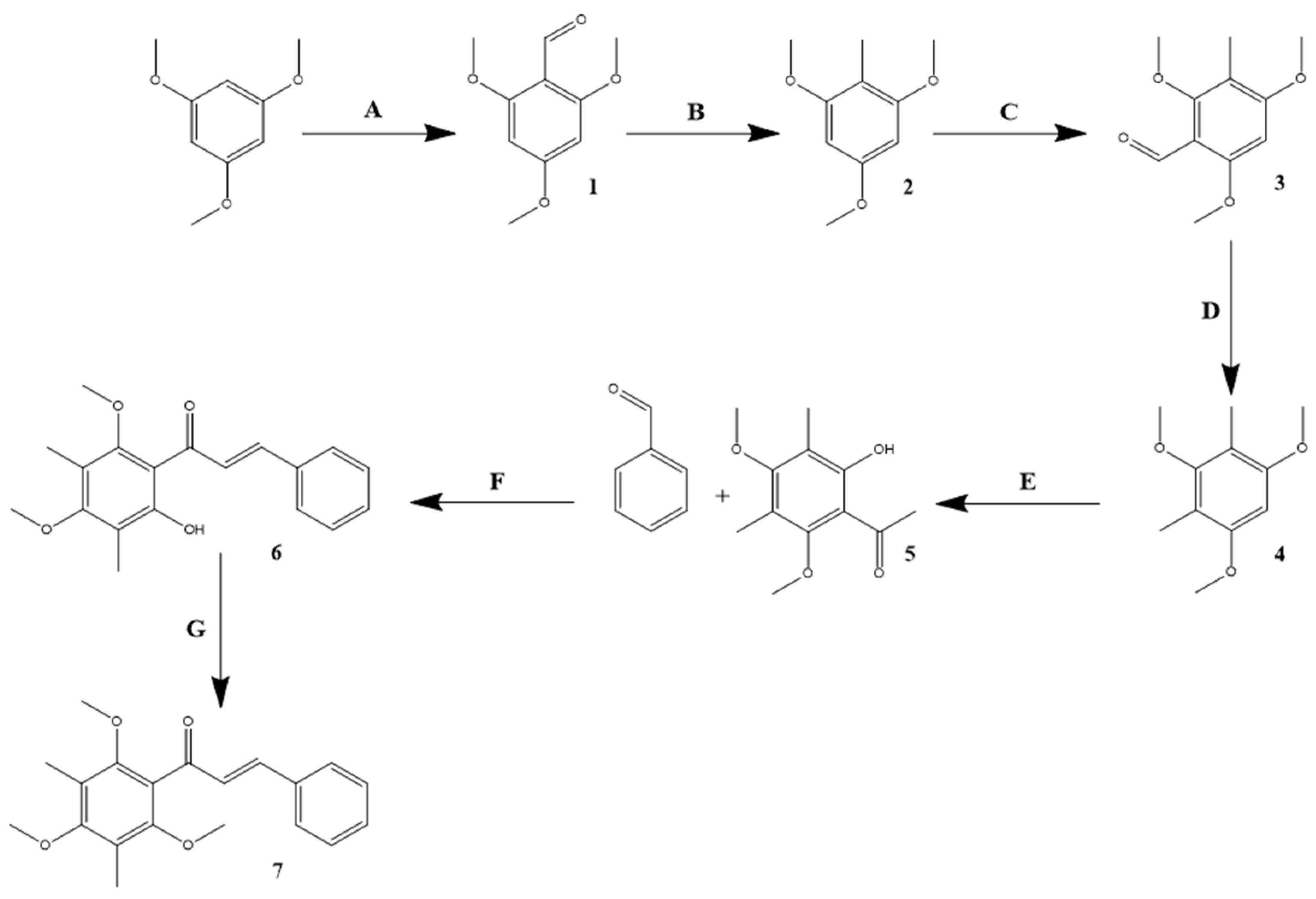

4.2. 3,5-Dimethyl-2,4,6-trimethoxychalcone (TriMetChalc) Synthesis Pathway (Figure 1)

4.2.1. Synthesis of 2,4,6-Trimethoxybenzaldehyde

4.2.2. Synthesis of 2,4,6-Trimethoxytoluene

4.2.3. Synthesis of 3-Methyl-2,4,6-trimethoxybenzaldehyde

4.2.4. Synthesis of 2,4-Dimethyl-1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene

4.2.5. Synthesis of 2-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethyl-4,6-dimethoxyacetophenone

4.2.6. Synthesis of 2-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethyl-4,6-dimethoxychalcone

4.2.7. Synthesis of 3,5-Dimethyl-2,4,6-dimethoxychalcone (TriMetChalc)

4.3. Per Os Administration of TriMetChalc

4.4. Food Intake Measurements and Pica Behavior (Kaolin Intake)

4.5. Tissue Histology and Oil Red O Staining

4.6. Immunohistochemistry Procedures

4.7. Microscopy, Image Analysis and Cell Count

4.8. Extraction and Analysis of Neutral Lipids and Phospholipids

4.9. Extraction and Analysis of Fatty Acids

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/de- 854tail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Mitra, S.; De, A.; Chowdhury, A. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeren, J.; Scheja, L. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and lipoprotein metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2021, 50, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, P.N.; Sarin, S.K.; Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Wong, V.W.S.; Dufour, J.F.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gofton, C.; Upendran, Y.; Zheng, M.H.; George, J. MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD? Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, S17–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Ayada, I.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Wen, T.; Ma, Z.; Bruno, M.J.; de Knegt, R.J.; Cao, W.; et al. Estimating Global Prevalence of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Overweight or Obese Adults. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e573–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbrini, E.; Sullivan, S.; Klein, S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology 2010, 51, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi-Sales, E.; Mohaddes, G.; Alipour, M.R. Chalcones as putative hepatoprotective agents: Preclinical evidence and molecular mechanisms. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, T.T.; Chuyen, N.V. Anti-hyperglycemic activity of an aqueous extract from flower buds of Cleistocalyx operculatus (Roxb.) Merr and Perry. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.C.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, W.G.; Mi, T.Y.; Zhou, L.X.; Huang, N.; Hoptroff, M.; Lu, Y.H. 2′,4′-dihydroxy-6′-methoxy-3′,5′-dimethylchalcone promoted glucose uptake and imposed a paradoxical effect on adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2014, 62, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Kim, M.; Song, H.; Lee, C.S.; Oh, W.K.; Mook-Jung, I.; Chung, S.S.; Park, K.S. DMC (2’,4’-dihydroxy-6’-methoxy-3’,5’-dimethylchalcone) improves glucose tolerance as a potent AMPK activator. Metabolism. 2016, 65, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benny, F.; Kumar, S.; Binu, A.; Parambi, D.G.T.; Alsahli, T.G.; Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Chandran, N.; Manisha, D.S.; Sreekumar, S.; Bhatt, A.; et al. Targeting GABA receptors with chalcone derivative compounds, what is the evidence? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2023, 27, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadi, V.; Malla, R.R.; Siragam, S. Natural and Synthetic Chalcones: Potential Impact on Breast Cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2023, 28, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nematollahi, M.H.; Mehrabani, M.; Hozhabri, Y.; Mirtajaddini, M.; Iravani, S. Antiviraland antimicrobial applications of chalcones and their derivatives: From nature to greener synthesis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trak-Smayra, V.; Paradis, V.; Massart, J.; Nasser, S.; Jebara, V.; Fromenty, B. Pathology of the liver in obese and diabetic ob/ob and db/db mice fed a standard or high-calorie diet. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2011, 92, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parlati, L.; Régnier, M.; Guillou, H.; Postic, C. New targets for NAFLD. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, C.L.; McCormack, S.E. Acquired hypothalamic obesity: A clinical overview and update. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.H.; Arnold, M.; Langhans, W. Lipopolysaccharide-induced anorexia following hepatic portal vein and vena cava administration. Physiol. Behav. 1998, 64, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardet, C.; Bonnet, M.S.; Jdir, R.; Sadoud, M.; Thirion, S.; Tardivel, C.; Roux, J.; Lebrun, B.; Wanaverbecq, N.; Mounien, L.; et al. The food-contaminant deoxynivalenol modifies eating by targeting anorexigenic neurocircuitry. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüning, J.C.; Fenselau, H. Integrative neurocircuits that control metabolism and food intake. Science 2023, 381, eabl7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillebaud, F.; Duquenne, M.; Djelloul, M.; Pierre, C.; Poirot, K.; Roussel, G.; Riad, S.; Lanfray, D.; Morin, F.; Jean, A.; et al. Glial Endozepines Reverse High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity by Enhancing Hypothalamic Response to Peripheral Leptin. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 3307–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaige, S.; Barbouche, R.; Barbot, M.; Boularand, S.; Dallaporta, M.; Abysique, A.; Troadec, J.D. Constitutively active microglial populations limit anorexia induced by the food contaminant deoxynivalenol. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, B.; Kahn, B.B. AMPK integrates nutrient and hormonal signals to regulate food intake and energy balance through effects in the hypothalamus and peripheral tissues. J. Physiol. 2006, 574, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minokoshi, Y.; Alquier, T.; Furukawa, N.; Kim, Y.B.; Lee, A.; Xue, B.; Mu, J.; Foufelle, F.; Ferré, P.; Birnbaum, M.J.; et al. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature 2004, 428, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, M. Hypothalamic AMPK and energy balance. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 48, e12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Chun, H.C.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, K.S.; Chung, S.S.; Park, K. Synthesis of 2′,4′,6′-trimethoxy-3′,5′-dimethylchalcone derivatives and their anti-diabetic and anti-atherosclerosis effect. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2023, 128, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.T.; Chang, F.R.; Tsai, Y.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Hsieh, T.J. 2-Bromo-4’-methoxychalcone and 2-Iodo-4’-methoxychalcone Prevent Progression of Hyperglycemia and Obesity via 5’-Adenosine-Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Viggiano, T.R.; McGill, D.B.; Oh, B.J. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1980, 55, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samy, A.M.; Kandeil, M.A.; Sabry, D.; Abdel-Ghany, A.A.; Mahmoud, M.O. From NAFLD to NASH: Understanding the spectrum of non-alcoholic liver diseases and their consequences. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.G.; Qian, J.; Lu, Y.H. Hepatoprotective effects of 2’,4’-dihydroxy-6’-methoxy-3’,5’-dimethylchalcone on CCl4-induced acute liver injury in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12821–12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hliwa, A.; Ramos-Molina, B.; Laski, D.; Mika, A.; Sledzinski, T. The role of fatty acids in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, H.; Bronk, S.F.; Werneburg, N.W.; Gores, G.J. Free fatty acids induce JNK-dependent hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 12093–12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, H.; Gores, G.J. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin. Liver Dis. 2008, 28, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Yang, L.; van Rooijen, N.; Brenner, D.A.; Ohnishi, H.; Seki, E. Toll-likereceptor 2 and palmitic acid cooperatively contribute to the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through inflammasome activation in mice. Hepatology 2013, 57, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lottenberg, A.M.; Afonso Mda, S.; Lavrador, M.S.; Machado, R.M.; Nakandakare, E.R. The role of dietary fatty acids in the pathology of metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Fu, Y.; Guo, G.; Zhang, X. Liver fatty acid composition in mice with or without nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2011, 10, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, P.; Baillie, R.A.; Wiest, M.M.; Mirshahi, F.; Choudhury, J.; Cheung, O.; Sargeant, C.; Contos, M.J.; Sanyal, A.J. A lipidomic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2007, 46, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spooner, M.H.; Jump, D.B. Omega-3 fatty acids and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults and children: Where do we stand? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2019, 22, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, G.; Cassader, M.; Paschetta, E.; Gambino, R. Bioactive lipid species and metabolic pathways in progression and resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 282–302.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Dou, Q.L.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.Y. Establishment of a hepatocyte steatosis model using Chang liver cells. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 15224–15232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Hong, W.; Yao, K.N.; Zhu, X.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Ye, L. Ursodeoxycholic acid ameliorates hepatic lipid metabolism in LO2 cells by regulating the AKT/mTOR/SREBP-1 signaling pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akazawa, Y.; Cazanave, S.; Mott, J.L.; Elmi, N.; Bronk, S.F.; Kohno, S.; Charlton, M.R.; Gores, G.J. Palmitoleate attenuates palmitate-induced Bim and PUMA upregulation and hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Listenberger, L.L.; Han, X.; Lewis, S.E.; Cases, S.; Farese Jr, R.V.; Ory, D.S.; Schaffer, J.E. Triglyceride accumulation protects against fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3077–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurikawa, N.; Takagi, T.; Wakimoto, S.; Uto, Y.; Terashima, H.; Kono, K.; Ogata, T.; Ohsumi, J. A novel inhibitor of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 attenuates hepatic lipid accumulation, liver injury and inflammation in model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 36, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uto, Y. Recent progress in the discovery and development of stearoyl CoA desaturase inhibitors. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2016, 197, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobili, V.; Alisi, A.; Musso, G.; Scorletti, E.; Calder, P.C.; Byrne, C.D. Omega-3 fatty acids: Mechanisms of benefit and therapeutic effects in pediatric and adult NAFLD. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2016, 53, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappini, F.; Coilly, A.; Kadar, H.; Gual, P.; Tran, A.; Desterke, C.; Samuel, D.; Duclos-Vallée, J.C.; Touboul, D.; Bertrand-Michel, J.; et al. Metabolism dysregulation induces a specific lipid signature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, E.J. Lipoproteins, nutrition, and heart disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Yuan, M.; Wang, L. The effect of Omega-3 unsaturated fatty acids on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, P.S.; Carla Inada, A.; Marcelino, G.; Maiara Lopes Cardozo, C.; de Cássia Freitas, K.; de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães, R.; Pereira de Castro, A.; Aragão do Nascimento, V.; Aiko Hiane, P. Fatty acids consumption: The role metabolic aspects involved in obesity and its associated disorders. Nutrients 2017, 22, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diraison, F.; Moulin, P.; Beylot, M. Contribution of hepatic de novo lipogenesis and reesterification of plasma non esterified fatty acids to plasma triglyceride synthesis during non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Metab. 2003, 29, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudgins, L.C.; Hellerstein, M.; Seidman, C.; Neese, R.; Diakun, J.; Hirsch, J. Human fatty acid synthesis is stimulated by a eucaloric low fat, high carbohydrate diet. J. Clin. Invest. 1996, 97, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Han, R.H.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Han, X. Lipidomic analysis reveals significant lipogenesis and accumulation of lipotoxic components in ob/ob mouse organs. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2018, 136, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Yang, L.; Li, P.; Hofmann, O.; Dicker, L.; Hide, W.; Lin, X.; Watkins, S.M.; Ivanov, A.R.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Aberrant lipid metabolism disrupts calcium homeostasis causing liver endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity. Nature 2011, 473, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, J.; Chaba, T.; Zhu, L.F.; Jacobs, R.L.; Vance, D.E. Hepatic ratio of phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidylethanolamine predicts survival after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veen, J.N.; Kennelly, J.P.; Wan, S.; Vance, J.E.; Vance, D.E.; Jacobs, R.L. The critical role of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 2017, 1859, 1558–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfield 2nd, J.W.; Ortinau, L.C.; Pickering, R.T.; Ruebel, M.L.; Meers, G.M.; Rector, R.S. Altered hepatic lipid metabolism contributes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in leptin-deficient Ob/Ob mice. J. Obes. 2013, 296537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, A.V.; Rambabu, A.; Giriprasad, P.V.; Rao, R.S.C.; Babu, B.H. Synthesis of (±)-Pisonivanone and Other Analogs as Potent Antituberculosis Agents. J. Chem. 2012, 2013, 961201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandam, R.; Jadav, S.S.; Ala, V.B.; Ahsan, M.J.; Bollikolla, H.B. Synthesis of new C-dimethylated chalcones as potent antitubercular agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2018, 27, 1690–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.W.; Damodar, K.; Kim, J.K.; Jun, J.G. First synthesis and in vitro biological assessment of isosideroxylin, 6,8-dimethylgenistein and their analogues as nitric oxide production inhibition agents. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 1114–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbouche, R.; Gaigé, S.; Airault, C.; Poirot, K.; Dallaporta, M.; Troadec, J.D.; Abysique, A. The food contaminant deoxynivalenol provokes metabolic impairments resulting in non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) in mice. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrans, A.; Collet, X.; Barbaras, R.; Jaspard, B.; Manent, J.; Vieu, C.; Chap, H.; Perret, B. Hepatic lipase induces the formation of pre-beta 1 high density lipoprotein (HDL) from triacylglycerol-rich HDL2. A study comparing liver perfusion to in vitro incubation with lipases. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 11572–11577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillington, J.M.; Trafford, D.J.; Makin, H.L. A rapid and simple method for the esterification of fatty acids and steroid carboxylic acids prior to gas-liquid chromatography. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1981, 111, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).