Submitted:

19 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bio-Based Fertilizers for Plants

2.1. EU Fertilizer Product Regulation

2.2. Biostimulants

2.3. Amino Acid-Based Biostimulants

3. Fish Protein Hydrolysates

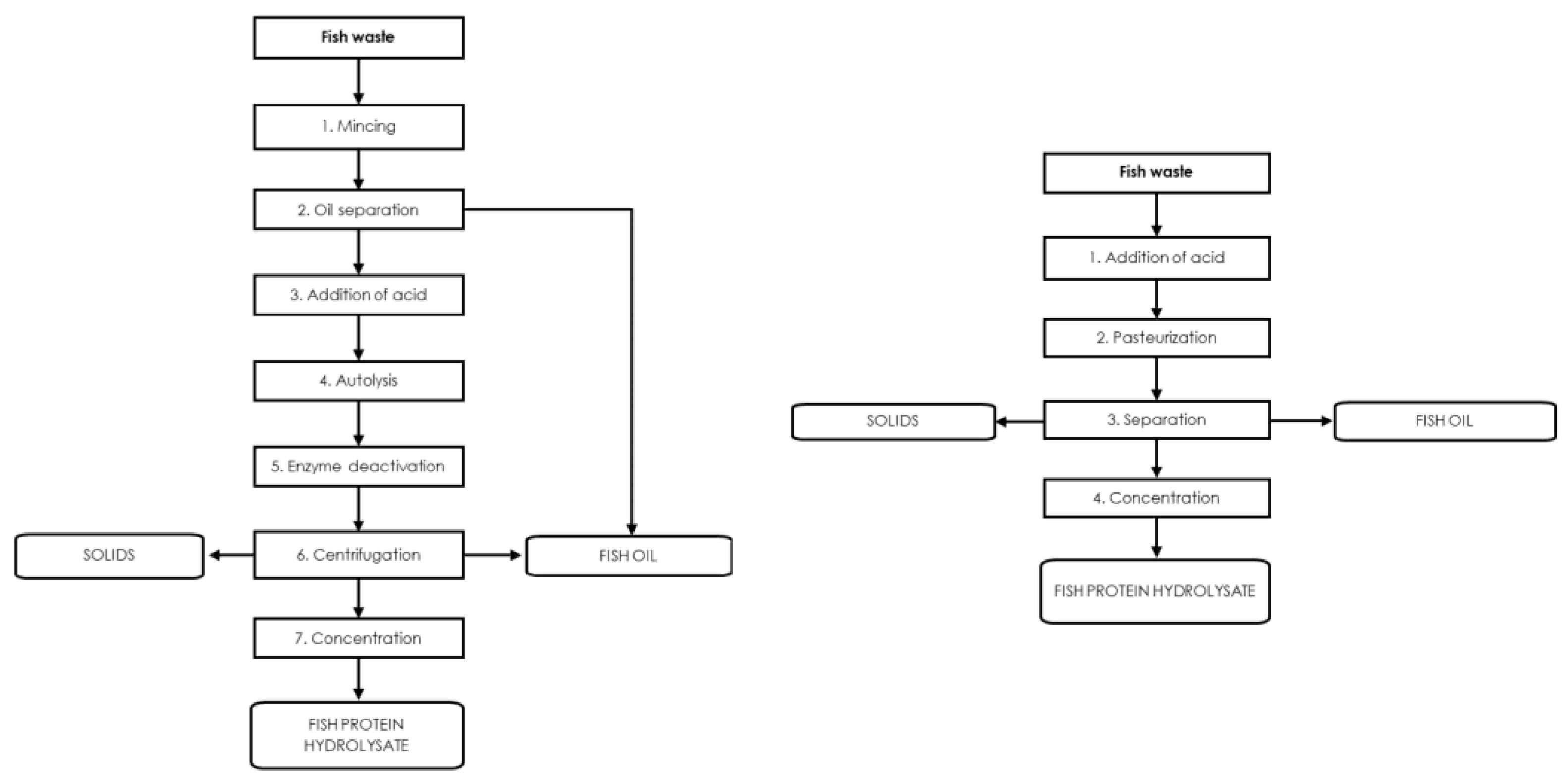

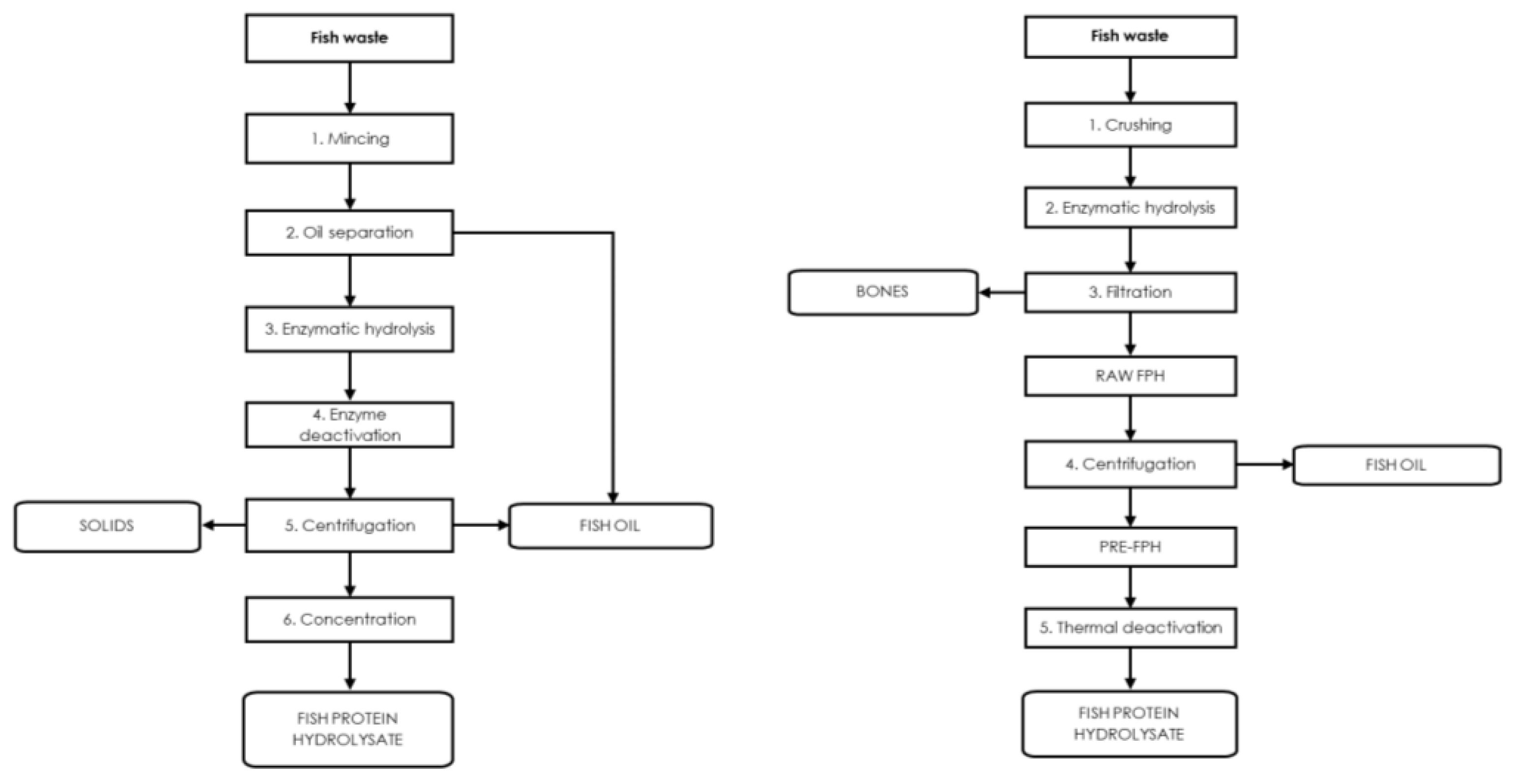

3.1. Chemical Hydrolysis

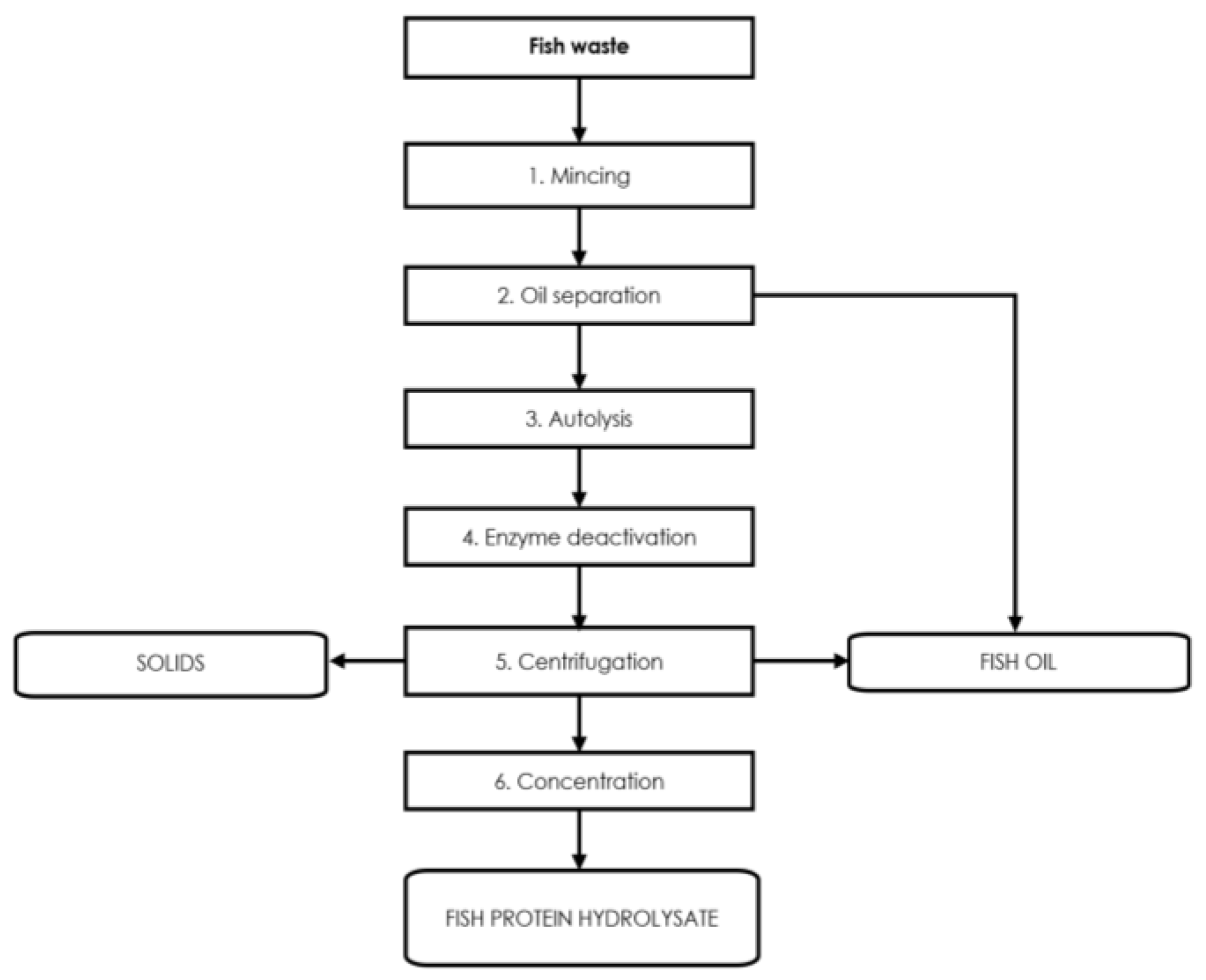

3.2. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

3.3. Endogenous Enzymes of Fish

3.4. Use of Fish Protein Hydrolysates in Agriculture

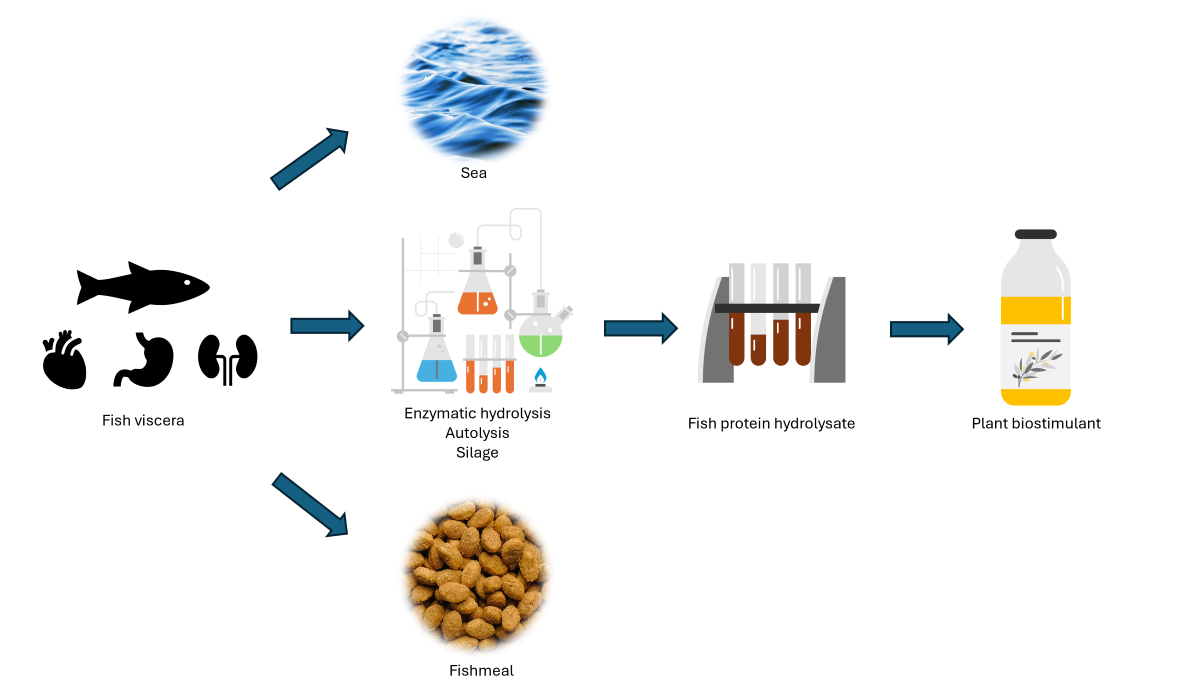

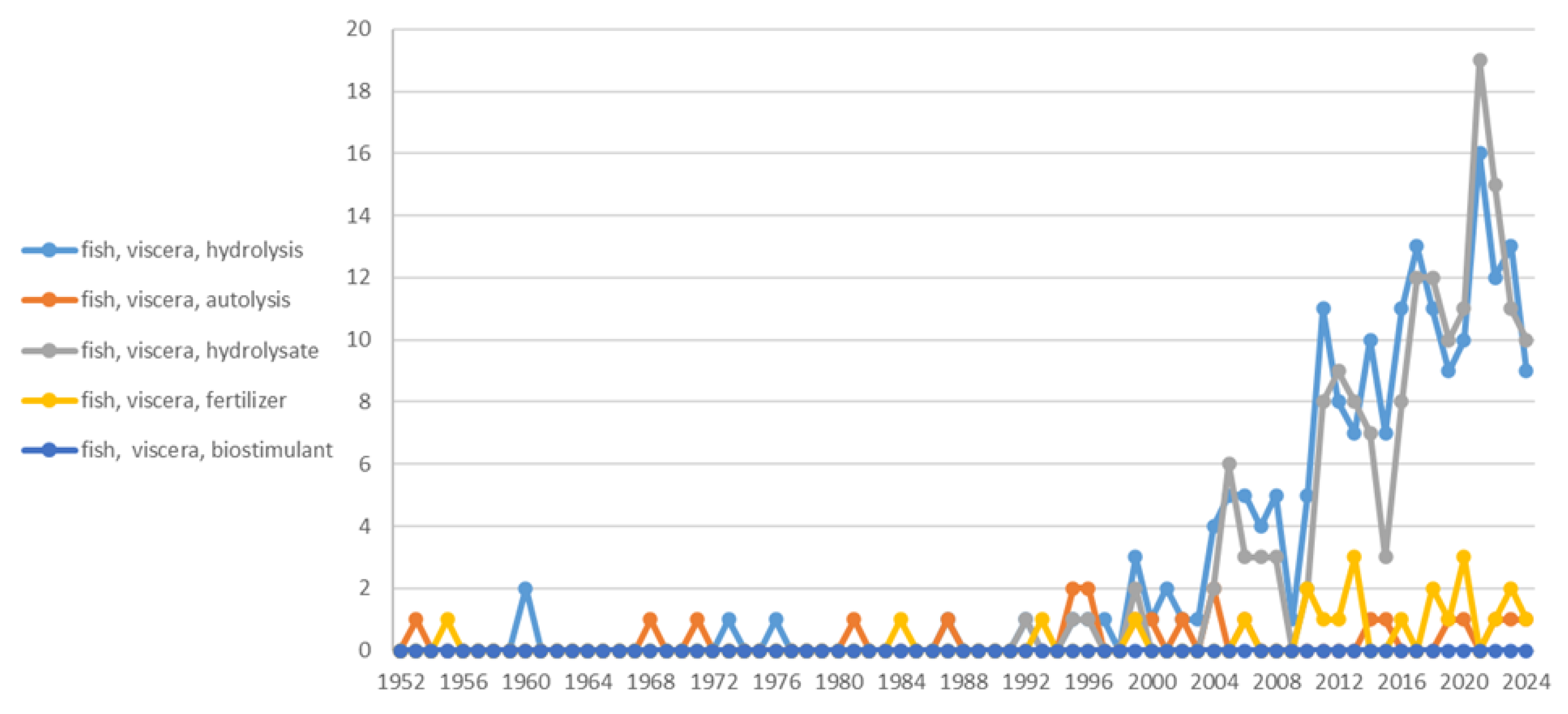

4. Fish Viscera

Fish Viscera Protein Hydrolysates

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO, 2022. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0461en.

- Moreira, T.F.M.; Pessoa, L.G.A.; Seixas, F.A.V.; Ineu, R.P.; Gonçalves, O.H.; Leimann, F.V.; Ribeiro, R.P. Chemometric evaluation of enzymatic hydrolysis in the production of fish protein hydrolysates with acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Food Chem., 2022, 367, 130728, . [CrossRef]

- Vidotti, R.M.; Macedo Viegas, E.M.; Carneiro, D.J. Amino acid composition of processed fish silage using different raw materials. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol., 2003, 105, 199-204, . [CrossRef]

- Radziemska, M.; Vaverková, M.D.; Adamcová, D.; Brtnický, M.; Mazur, Z. Valorization of fish waste compost as a fertilizer for agricultural use. Waste Biomass Valori., 2019, 10, 2537-2545, . [CrossRef]

- Vernieri, P.; Borghesi, E., Ferrante, A.; Magnani, G. Application of biostimulants in floating system for improving rocket quality. J. Food Agric. Environ., 2005, 3, 86-88.

- Kurniawati, A.; Toth, G.; Ylivainio, K.; Toth, Z. Opportunities and challenges of bio-based fertilizers utilization for improving soil health. Org. Agric., 2023, 13, 335-350, . [CrossRef]

- European Commission, 2016. Circular economy: new regulation to boost the use of organic and waste-based fertilisers. Brussels, 17th March of 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/en/ip_16_827/IP_16_827_EN.pdf.

- Chojnacka, K.; Moustakas, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. Bio-based fertilizers: a practical approach towards circular economy. Bioresour. Technol., 2020, 295, 122223, . [CrossRef]

- Tur-Cardona, J.; Bonnichsen, O.; Speelman, S.; Verspecht, A.; Carpentier, L.; Debruyne, L.; Marchand, F.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Buysse, J. Farmers' reasons to accept bio-based fertilizers: a choice experiment in seven different European countries. J. Clean. Prod., 2018, 197, 406-416, . [CrossRef]

- Jaies, I.; Qayoom, I.; Saba, F.; Khan, S. Fish wastes as source of fertilizers and manures. In Fish wastes to valuable products, 1st ed.; Maqsood, S., Naseer, M.N., Benjakul, S., Zaidi, A.A.; Springer, pp. 329-338.

- European Commission, 2019. Regulation 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 laying down rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilising products and amending Regulations No 1069/2009 and repealing Regulation No 2003/2003. Official Journal of the European Union, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/oj.

- Madende, M.; Hayes, M. Fish by-product use as biostimulants: an overview of the current state of the art, including relevant legislation and regulations within the EU and USA. Molecules, 2020, 25, 1122, . [CrossRef]

- Drobek, M.; Frac, M.; Cybulska, J. Plant biostimulants: importance of the quality and yield of horticultural crops and the improvement of plant tolerance to abiotic stress — a review. Agronomy, 2019, 9(6), 355, . [CrossRef]

- Parađiković, N.; Teklić, T.; Zeljković, S.; Lisjak, M.; Špoljarević, M. Biostimulants research in some horticultural plant species - a review. Food Energy Secur., 2019, 8, e00162, . [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L.K.; Macdonald, L.M.; Wong, M.T.F.; Webb, M.J.; Jenkins, S.N.; Farrell, M. Potential roles of biological amendments for profitable grain production - a review. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 2018, 256, 34-50, . [CrossRef]

- Pecha, J.; Fürst, T.; Kolomazník, K.; Friebrová, V.; Svoboda, P. Protein biostimulant foliar uptake modelling: the impact of climatic conditions. AIChE, 2012, 58(7), 2010-2019, . [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Nardi, S.; Lucini, L.; Canaguier, R.; Rouphael, Y. Protein hydrolysates as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic., 2015, 196, 28-38, . [CrossRef]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. (2017). Biostimulants in plant science: a global perspective. Front. Plant Sci., 2017, 7, 2049, . [CrossRef]

- European Biostimulants Industry Council, 2018, https://biostimulants.eu/ Access date: 24/04/2024.

- Du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic., 2015, 196, 3-14, . [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, G.; Cocetta, G.; Ferrante, A. Effect of glutamic acid foliar applications on lettuce under water stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants, 2021, 27(5), 1059-1072, . [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.G.; Yu, C.; Yang, L.; Qin, S.J.; Ma, H.Y.; Du, G.D.; Liu, G.C.; Khanizadeh, S. Effects of Foliar-Applied L-Glutamic Acid on the Diurnal Variations of Leaf Gas Exchange and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters in Hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida Bge.). European Journal of Horticultural Science, 2009, 74(5), 204-209.

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Cheng, Q.; Sun, W. The effects of amino acids, phenols and protein hydrolysates as biostimulants on sustainable crop production and alleviated stress. Recent Pat. Biotechnol., 2022, 16, 319-328, . [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, R.; Cocetta, G.; Trivellini, A.; Vernieri, P.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulants and crop responses: a review. Biol. Agric. Hortic., 2014, 31(1), 1-17, . [CrossRef]

- Vranova, V.; Rejsek, K.; Skene, K.R.; Formanek, P. Non-protein amino acids: plant, soil and ecosystem interactions. Plant Soil, 2011, 342, 31-48, . [CrossRef]

- Ashmead, H.D.; Ashmead, H.H.; Miller, G.W.; Hsu, H.H. (1986). Foliar feeding of plants with amino acid chelates. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Publications.

- Souri, M. K. Aminochelate fertilizers: the new approach to the old problem; a review. Open Agriculture, 2016, 1 (1), 118-123. [CrossRef]

- Serna-Rodríguez, J.R.; Castro-Brindis, R.; Colinas-León, M.T.; Sahagún-Castellanos, J.; Rodríguez-Pérez, J.E. Aplicación foliar de ácido glutámico en plantas de jitomate (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). RCHSH, 2011, 17(1), 9-13.

- Alahmad, K.; Noman, A.; Xia, W.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, Y. Influence of the Enzymatic Hydrolysis Using Flavourzyme Enzyme on Functional, Secondary Structure, and Antioxidant Characteristics of Protein Hydrolysates Produced from Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis). Molecules, 2023, 28(2), 519, . [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, H.; Iñarra, B.; Labidi, J.; Mendiola, D.; Bald, C. Comparison of amino acid release between enzymatic hydrolysis and acid autolysis of rainbow trout viscera. Heliyon, 2024, 10, e27030, . [CrossRef]

- Opheim, M.; Slizyte, R.; Sterten, H; Provan, F.; Larssen, E.; Kjos, N.P. Hydrolysis of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) rest raw materials – Effect of raw material and processing on composition, nutritional value, and potential bioactive peptides in the hydrolysates. Process Biochem., 2015, 50, 1247-1257, . [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot., 2007, 59, 206-216, . [CrossRef]

- Heyser, J.W.; De Bruin, D.; Kincaid, M.L.; Johnson, R.Y.; Rodriguez, M.M.; Robinson, N.J. Inhibition of NaCI-induced proline biosynthesis by exogenous proline in halophilic Distichlis spicata suspension cultures. J. Exp. Bot., 1989, 40(2), 225-232, . [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M. M. F. Protection of plasma membrane of onion epidermal cells by glycinebetaine and proline against NaCl stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem., 1998, 36(10), 767-772, . [CrossRef]

- Chrominski, A.; Halls, S.; Weber, D.J.; Smith, B.N. Proline affects ACC to ethylene conversion under salt and water stresses in the halophyte, Allenrolfea occidentalis. Environ. Exp. Bot, 1989, 29(3), 359-363, . [CrossRef]

- Flores, T.; Todd, C.D.; Tovar-Mendez, A.; Dhanoa, P.K.; Correa-Aragunde, N.; Hoyos, M.E.; Brownfield, D.M.; Mullen, R.T.; Lamattina, L.; Polacco, J.C. (2008). Arginase-negative mutants of arabidopsis exhibit increased nitric oxide signaling in root development. Plant Physiol., 2008, 147(4), 1936-1946, . [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Fraguas, J.; Mirón, J.; Valcárcel, J.; Pérez-Martín, R.I.; Antelo, L.T. Valorisation of fish discards assisted by enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial bioconversion: Lab and pilot plant studies and preliminary sustainability evaluation. J. Clean Prod., 2020, 246, 119027, . [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.T.; Hirata, M.; Toorisaka, E.; Hano, T. Acid-hydrolysis of fish wastes for lactic acid fermentation. Bioresour. Technol., 2006, 97, 2414-2420, . [CrossRef]

- Wisuthiphaet, N.; Kongruang, S. Production of fish protein hydrolysates by acid and enzymatic hydrolysis. JOMB, 2015, 4(6), 466-470, 10.12720/jomb.4.6.466-470.

- Villamil, O.; Váquiro, H.; Solanilla, J.F. Fish viscera protein hydrolysates: Production, potential applications and functional and bioactive properties. Food Chem., 2017, 224, 160-171, . [CrossRef]

- Aspmo, S.I.; Horn, S.J.; Eijsink, V.G.H. Enzymatic hydrolysis of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.) viscera. Process Biochem., 2005, 40(5), 1957-1966, . [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, S.F.; Cavallini, N.; Demichelis, F.; Savorani, F.; Mancini, G.; Fino, D.; Tommasi, T. From tuna viscera to added-value products: A circular approach for fish-waste recovery by green enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Bioprod. Process., 2023, 137, 155-167, . [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, V.V.; Ghaly, A.E.; Brooks, M.S.; Budge, S.M. Extraction of proteins from mackerel fish processing waste using Alcalase enzyme. J. Bioprocess. Biotechniq., 2013, 3, 130, . [CrossRef]

- Valcarcel, J.; Sanz, N.; Vázquez, J.A. Optimization of the enzymatic protein hydrolysis of by-products from seabream (Sparus aurata) and seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax), chemical and functional characterization. Foods, 2020, 9, 1503, . [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, J.A.; Sotelo, C.G.; Sanz, N.; Pérez-Martín, R.I.; Rodríguez Amado, I.; Valcarcel, J. Valorization of aquaculture by-products of salmonids to produce enzymatic hydrolysates: process optimization, chemical characterization and evaluation of bioactives. Mar. Drugs, 2019, 17, 676, . [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, K.; Tokur, B. Optimization of hydrolysis conditions for the production of protein hydrolysates from fish wastes using response surface methodology. Food Biosci., 2022, 45, 101312, . [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D.; Lauritano, C.; Esposito, F.P.; Riccio, G.; Rizzo, C.; de Pascale, D. (2021). Fish waste: from problem to valuable resource. Mar. Drugs, 2021, 19, 116, . [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Varatharajan, V.; Peng, H.; Senadheera, R. Utilization of marine by-products for the recovery of value-added products. J. Food Bioact., 2019, 6, 10-61, . [CrossRef]

- Vannabun, A.; Ketnawa, S.; Phongthai, S.; Benjakul, S.; Rawdkuen, S. Characterization of acid and alkaline proteases from viscera of farmed giant catfish. Food Biosci., 2014, 6, 9-16, . [CrossRef]

- Sriket, C. (2014). Proteases in fish and shellfish: role on muscle softening and prevention. Int. Food Res. J., 2014, 21(2), 433-445.

- Fisheries processing (1994). Edited by A.M. Martin. 1st edition; Springer, 1994. 10.1007/978-1-4615-5303-8.

- Morrissey, M.T.; Okada, T. Marine enzymes from seafood by-products. In Maximising the value of marine by-products, 1st ed., Shahidi, F., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Limited, Cambridge, England, 2007; pp. 374-396.

- Olsen, R.; Toppe, J. Fish silage hydrolysates: not only a feed nutrient, but also a useful feed additive. Trends Food Sci. Technol., 2017, 66, 93-97, . [CrossRef]

- Richardsen, R.; Nystøyl, N.; Strandheim, G.; Viken, A. Analyse marint restråstoff, 2014. Retrieved from https://sintef.brage.unit.no/sintef-xmlui/handle/11250/2454964?locale-attribute=en.

- Olsen, R.; Toppe, J.; Karunasagar, I. Challenges and realistic opportunities in the use of by-products from processing of fish and shellfish. Trends Food Sci. Technol., 2014, 36, 144-151, . [CrossRef]

- Prabha, J.; Narikimelli, A.; Sajini, M.I.; Vincent, S. Optimization for autolysis assisted production of fish protein hydrolysate from underutilized fish Pellona ditchela. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res., 2013, 4(12), 1863-1869, ISSN 2229-5518.

- van't Land, M.; Vanderperren, E.; Raes, K. The effect of raw material combination on the nutritional composition and stability of four types of autolyzed fish silage. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol., 2017, 234, 284-294, . [CrossRef]

- Arason, S.; Thoroddsson, G.; Valdimarsson, G. (1990). The production of silage from waste and industrial fish: the Icelandic experience. Marketing profit out of seafood wastes. Proceedings of the International Conference on Fish By-products (ed. S. Keller), University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska, pp. 79-85.

- Cao, W.; Zhang, C.; Hong, P.; Ji, H. Response surface methodology for autolysis parameters optimization of shrimp head and amino acids released during autolysis. Food Chem., 2008, 109, 176-183, . [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, H.; Iñarra, B.; Labidi, J.; Bald, C. (2024). Optimization of the autolysis of rainbow trout viscera for amino acid release using response surface methodology. Open Research Europe, 2024, 4, 141, . [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, M.; Regenstein, J.M.; Noori, F.; Gheshlaghi, S.P. Autolysis of rainbow trout by-products: enzymatic activities, lipid and protein oxidation, and antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates. LWT - Food Sci. Technol., 2021, 140, 110702, . [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.; Dauksas, E.; Remme, J.F.; Richardsen, R.; Løes, A.K. Fish and fish waste-based fertilizers in organic farming – with status in Norway: a review. Waste Manage., 2020, 115, 95-112, . [CrossRef]

- Ertani, A.; Pizzeghello, D.; Francioso, O.; Sambo, P.; Sanchez-Cortes, S.; Nardi, S. (2014). Capsicum chinensis L. growth and nutraceutical properties are enhanced by biostimulants in a long-term period: chemical and metabolomic approaches. Front. Plant Sci., 2014, 5, 1-12, 10.3389/fpls.2014.00375.

- Halpern, M.; Bar-Tal, A.; Ofek, M.; Minz, D.; Muller, T.; Yermiyahu, U. The use of biostimulants for enhancing nutrient uptake. In Advances in Agronomy, 2015; Sparks, D.L., Volume 130, pp. 141-174.

- Cerdán, M.; Sánchez-Sánchez, A.; Oliver, M.; Juárez, M.; Sánchez-Andreu, J.J. Effect of foliar and root applications of amino acids on iron uptake by tomato plants. Acta Hortic., 2009, 830, 481-488.

- Corte, L.; Dell'Abate, M.T.; Magini, A.; Migliore, M.; Felici, B.; Roscini, L.; Sardella, R.; Tancini, B.; Emiliani, C.; Cardinali, G.; Benedetti, A. Assessment of safety and efficiency of nitrogen organic fertilizers from animal-based protein hydrolysates – a laboratory multidisciplinary approach. J. Sci. Food Agr., 2014, 94, 235-245, 10.1002/jsfa.6239.

- FAO, 2023. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics. Global aquaculture production 1950-2021 (FishStatJ). FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Division [online]. Version 4.01.0, Rome. Update 2023, www.fao.org/fishery/es/statistics/software/fishstatj.

- FAO, 2023. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics. Global catches 1950-2021 (FishStatJ). FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Division [online]. Version 4.01.0, Rome. Update 2023, www.fao.org/fishery/es/statistics/software/fishstatj.

- APROMAR (La acuicultura en España, 2023). Available online: https://apromar.es/notas-de-prensa/apromar-publica-su-informe-anual-la-acuicultura-en-espana-2023/ (accessed on 17/03/2024).

- Singh, A.; Soottawat, B. Proteolysis and its control using protease inhibitors in fish and fish products: a review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F., 2018, 17(2), . [CrossRef]

| Product Function Category (PFC) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Component Material Category (CMC) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Contaminant | Limit value (mg/kg dry matter) |

| Mercury (Hg) | 1 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 1.5 |

| Hexavalent chromium (Cr VI) | 2 |

| Inorganic arsenic (As) | 40 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 50 |

| Lead (Pb) | 120 |

| Copper (Cu) | 600 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 1500 |

| Reference | Raw material | Enzyme | Dose (% of Protein) |

pH | Temperature (°C) |

Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valcarcel et al. [44] | Seabream heads Seabass heads |

Alcalase | 0.2 | 8.2 8.5 |

57.1 58.4 |

3 3 |

||

| Garofalo et al. [42] | Tuna viscera | Alcalase | 1 | 8.5 | 55 | 2 | ||

| Vázquez et al. [45] | Rainbow trout frames and trimmings Salmon heads |

Alcalase | 0.1 0.2 |

8.3 9 |

56 64 |

3 3 |

||

| Aspmo et al. [41] | Cod viscera | Alcalase | 1 g/100 g of sample |

Unadjusted | 55 | 24 | ||

| Ramakrishnan et al. [43] | Mackerel waste | Alcalase | 0.5 | 7.5 | 55 | 1 | ||

| Domínguez et al. [30] | Rainbow trout viscera | Alcalase + Protana Prime |

1 | 7 | 60 | 7 | ||

| Korkmaz et al. [46] | Trout waste | Alkaline protease | 1 (enzyme /substrate) |

8 | 60 | 1 | ||

| Aspmo et al. [41] | Cod viscera | Protamex | 1 g/100 g of sample |

Unadjusted | 55 | 24 | ||

| Alahmad et al. [29] | Bighead carp | Flavourzyme | 4% (enzyme /substrate) |

6.5 | 50 | 6 | ||

| Tonnes by country, 2021 | Captures | Estimated range of by-products weight |

Estimated range of viscera weight |

Aquaculture | Estimated range of by-products weight |

Estimated range of viscera weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 7,589 | 4,553 – 5,312 | 607 – 1,138 | 8,048 | 4,829 – 5,634 | 644 – 1,207 |

| Austria | 350 | 210 – 245 | 28 – 53 | 4,875 | 2,925 – 3,413 | 390 – 731 |

| Belgium | 13,805 | 8,283 – 9,664 | 1,104 – 20,171 | 223 | 134 – 156 | 18 – 33 |

| Belarus | 605 | 363 – 424 | 48 – 91 | 8,504 | 5,102 – 5,953 | 680 – 1,276 |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 305 | 183 – 214 | 24 – 46 | 3,819 | 2,291 – 2,673 | 305 – 573 |

| Bulgaria | 55,484 | 33,291 – 38,839 | 4,439 – 8,323 | 12,565 | 7,539 – 8,796 | 1,005 – 1,885 |

| Croatia | 59,960 | 35,976 – 41,982 | 4,797 – 8,994 | 25,970 | 15,582 – 18,179 | 2,078 – 3,896 |

| Cyprus | 1,357 | 814 – 950 | 109-204 | 7,845 | 4,707 – 5,492 | 628-1,177 |

| Czechia | 3,314 | 1,988 – 2320 | 265 – 497 | 20,991 | 12,595 – 14,694 | 1,679 – 3,149 |

| Denmark | 415,261 | 249,157 – 290,683 | 33,221 – 62,289 | 32,100 | 19,260 – 22,470 | 2,568 – 4,815 |

| Estonia | 63,189 | 37,913 – 44,232 | 5,055 – 9,478 | 849 | 509 – 594 | 68 – 127 |

| Faroe Islands | 532,282 | 319,369 – 372,597 | 42,583-79,842 | 115,650 | 69,390 – 80,955 | 9,252-17,348 |

| Finland | 124,835 | 74,901 – 87,384 | 9,987 – 18,725 | 14,399 | 8,639 – 10,079 | 1,152 – 2,160 |

| France | 362,379 | 217,427 – 253,665 | 28,990 – 54,357 | 47,910 | 28,746 – 33,537 | 3,833 – 7,187 |

| Germany | 176,847 | 106,108 – 123,793 | 14,148 –26,527 | 18,294 | 10,976 – 12,806 | 1,464 – 2,744 |

| Greece | 46,764 | 28,058 – 32,735 | 3,741 – 7,015 | 130,171 | 78,103 – 91,120 | 10,414 – 19,526 |

| Hungary | 4,601 | 2,761 – 3,221 | 368 – 690 | 17,847 | 10,708 – 12,493 | 1,428 – 2,677 |

| Iceland | 1,027,250 | 616,350 – 719,075 | 82,180 – 154,088 | 53,136 | 31,882 – 37,195 | 4,251 – 7,970 |

| Ireland | 184,761 | 110,857 – 129,333 | 14,781 – 27,714 | 13,381 | 8,029 – 9,367 | 1,070 – 2,007 |

| Italy | 94,016 | 56,410 – 65,811 | 7,521 – 14,102 | 60,484 | 36,290 – 42,339 | 4,839 – 9,073 |

| Latvia | 116,413 | 69,848 – 81,489 | 9,313 – 17,462 | 901 | 541 – 631 | 72 – 135 |

| Liechtenstein | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lithuania | 91,253 | 54,752 – 63,877 | 7,300 | 5,135 | 3,081 – 3,595 | 411 – 770 |

| Luxembourg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moldova | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12,900 | 7,740 – 9,030 | 1,032 – 1,935 |

| Malta | 2,353 | 1,412 – 1,647 | 188 – 353 | 16,433 | 9,860 – 11,503 | 1,315 – 2,465 |

| Montenegro | 753 | 452 – 527 | 60 – 113 | 640 | 384 – 448 | 51 – 96 |

| Netherlands | 261,571 | 156,943 – 183,100 | 20,926 – 39,236 | 5,540 | 3,324 – 3,878 | 443 – 831 |

| North Macedonia | 514 | 308 – 360 | 41 – 77 | 3,169 | 1,901 – 2,218 | 254 – 475 |

| Norway | 2,115,496 | 1,269,298 – 1,480,847 | 169,240 – 317,324 | 1,662,675 | 997,605 – 1,163,873 | 133,014 – 249,401 |

| Poland | 201,321 | 120,793 – 140,925 | 16,106 – 30,198 | 44,786 | 26,872 – 31,350 | 3,583 – 6,718 |

| Portugal | 156,076 | 93,646 – 109,253 | 12,486 – 23,411 | 8,671 | 5,203 – 6,070 | 694 – 1,301 |

| Romania | 3,476 | 2,086 – 2,433 | 278 – 521 | 11,714 | 7,028 – 8,200 | 937 – 1,757 |

| Serbia | 2,354 | 1,412 – 1,648 | 188 – 353 | 7,308 | 4,385 – 5,116 | 585 – 1,096 |

| Slovakia | 1,815 | 1,089 – 1,271 | 145 – 272 | 2,304 | 1,382 – 1,613 | 184 – 346 |

| Slovenia | 241 | 145 – 169 | 19 – 36 | 1,256 | 754 – 879 | 100 – 188 |

| Spain | 743,530 | 446,118 – 520,471 | 59,482 – 111,530 | 70,285 | 42,171 – 49,200 | 5,623 – 10,543 |

| Sweden | 155,925 | 93,555 – 109,148 | 12,474 – 23,389 | 11,796 | 7,078 – 8,257 | 944 – 1769 |

| Switzerland | 1,486 | 892 – 1,040 | 119 – 223 | 2,334 | 1,400 – 1,634 | 187 – 350 |

| Ukraine | 34,507 | 20,704 – 24,155 | 2,761 – 5,176 | 16,882 | 10,129 – 11,817 | 1,351 – 2,532 |

| United Kingdom | 523,488 | 314,093 – 366,442 | 41,879 – 78,523 | 219,198 | 131,519 – 153,439 | 17,536 – 32,880 |

| TOTAL | 7,587,527 | 4,552,516 – 5,311,269 | 607,002 – 1,138,129 | 2,700,987 | 1,620,592 –1,890,691 | 216,079 – 405,148 |

| Tonnes by country, 2021 | Carp | Seabass | Gilt-head bream | Salmon | Trout | Turbot |

| Albania | - | 2,463 | 3,724 | - | 1,861 | - |

| Austria | 666 | - | - | 8 | 3,205 | - |

| Belgium | 7,557 | - | - | - | 127 | - |

| Belarus | 356.2 | 54 | 82 | - | 3,317 | - |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bulgaria | 5,986 | - | - | 1 | 5,468 | - |

| Croatia | 3,630 | 9,039 | 7,519 | - | 350 | - |

| Cyprus | - | 2,680 | 5,097 | - | 52 | - |

| Czechia | 18,709 | - | - | - | 1,070 | - |

| Denmark | - | 14 | - | 1,668 | 28,476 | - |

| Estonia | - | - | - | - | 712 | - |

| Faroe Islands | - | - | - | 115,650 | - | - |

| Finland | - | - | - | - | 13,551 | - |

| France | 1,470 | 2,290 | 1,850 | - | 38,800 | - |

| Germany | 4610 | - | - | - | 8725 | - |

| Greece | 1 | 51,232 | 66,891 | - | 1,911 | - |

| Hungary | 12,707 | - | - | - | 74 | - |

| Iceland | - | - | - | 46,458 | 6,341 | - |

| Ireland | - | - | - | 12,844 | 537 | - |

| Italy | 199 | 7,394 | 8,176 | - | 41,971 | 30 |

| Latvia | 564 | - | - | - | 183 | - |

| Liechtenstein | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lithuania | 3,734 | - | - | - | 131 | - |

| Luxembourg | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Moldova | - | 221 | 2,640 | - | - | - |

| Malta | 10,580 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Montenegro | - | 43 | 36 | - | 561 | - |

| Netherlands | - | - | - | - | 50 | 100 |

| North Macedonia | 299 | - | - | - | 2,828 | - |

| Norway | - | - | - | 1,562,415 | 97,774 | - |

| Poland | 18,941 | - | - | - | 19,298 | - |

| Portugal | - | 834 | 3,091 | - | 857 | 3,538 |

| Romania | 7,369 | - | - | - | 2,747 | - |

| Serbia | 5,649 | - | - | - | 1,556 | - |

| Slovakia | 740 | - | - | - | 800 | - |

| Slovenia | 131 | - | - | - | 921 | - |

| Spain | - | 23,037 | 7,823 | - | - | 7,629 |

| Sweden | - | - | - | - | 11,703 | - |

| Switzerland | - | - | - | 162 | 1,230 | - |

| Ukraine | 13,450 | - | - | - | 312 | - |

| United Kingdom | 168 | - | - | 205,000 | 13,253 | - |

| Total fish weight | 117,516 | 99,301 | 106,929 | 1,944,206 | 310,751 | 11,297 |

| Estimated range of by-products weight |

70,510 – 82,261 | 59,581 – 69,511 | 64,157 – 74,850 | 1,166,524 – 1,360,944 | 186,451 – 217,526 | 6,778 – 7,908 |

| Estimated range of viscera weight |

9,401 – 17,627 | 7,944 – 14,895 | 8,554 – 16,039 | 155,536 – 291,631 | 24,860 – 46,613 | 904 – 1,695 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).