Submitted:

19 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

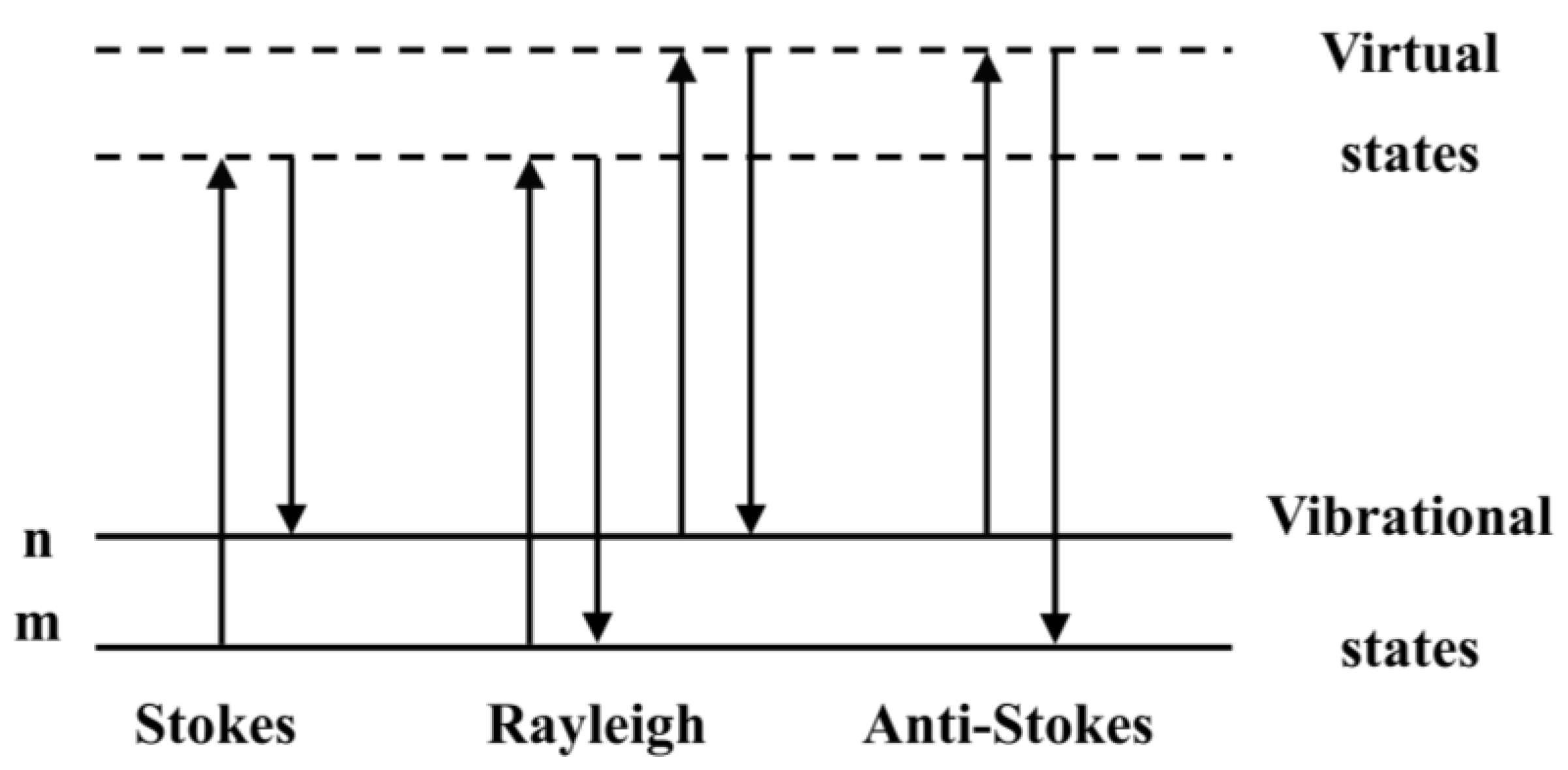

1. Introduction to Raman Scattering Spectroscopy

2. Development of SERS Technology

3. Theoretical Mechanisms for the Emergence of the SERS Phenomenon

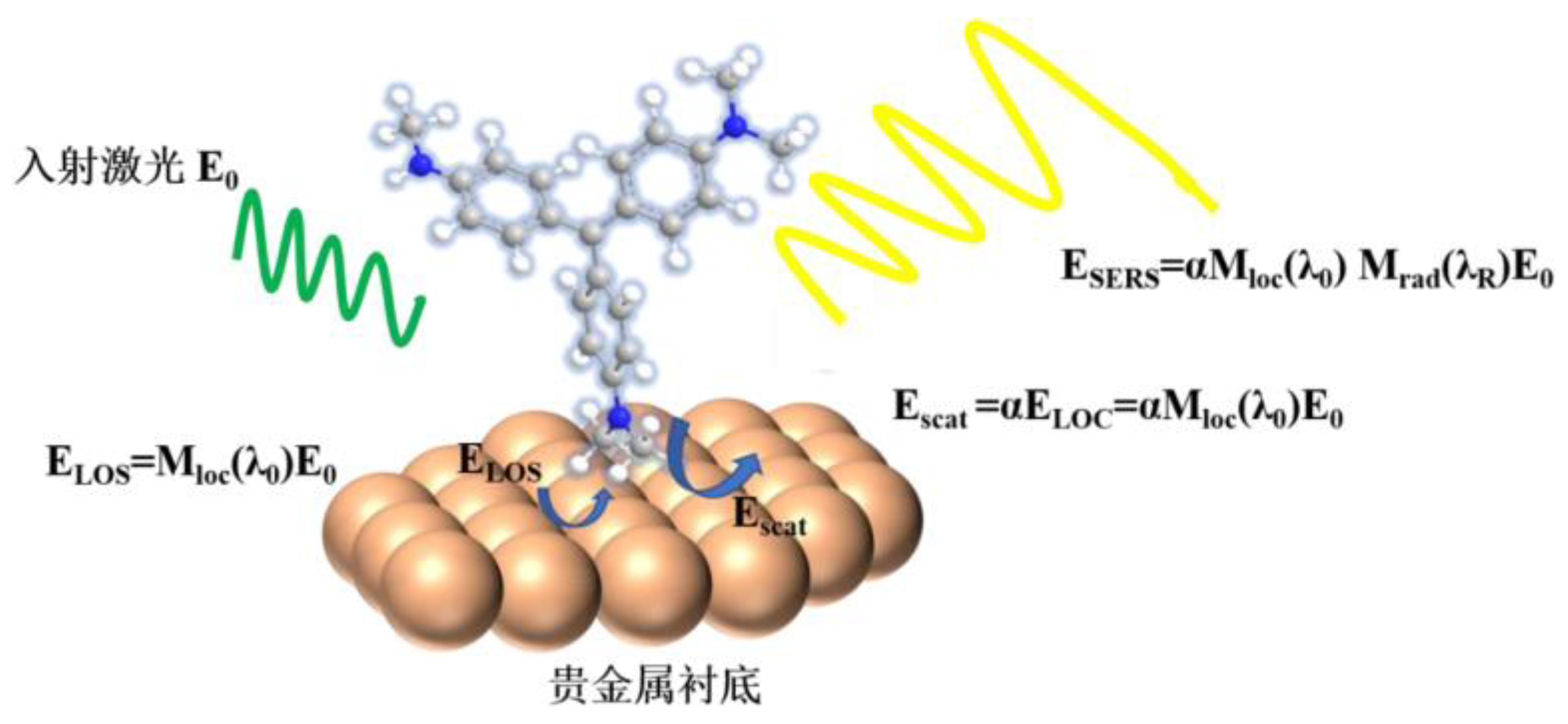

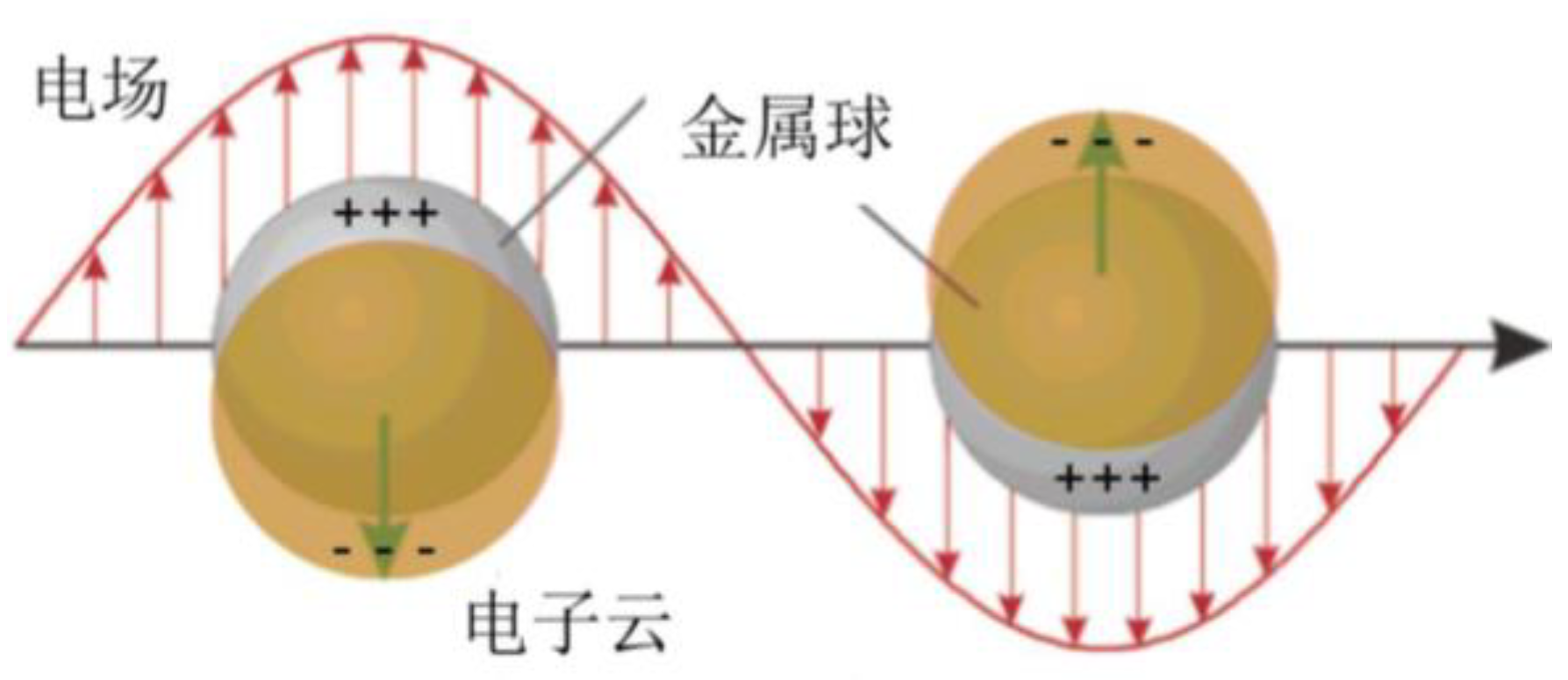

3.1. Electromagnetic Enhancement Mechanism

3.2. Chemical Enhancement Mechanism

3.3. Theoretical Modeling of SERS Enhancement Effects

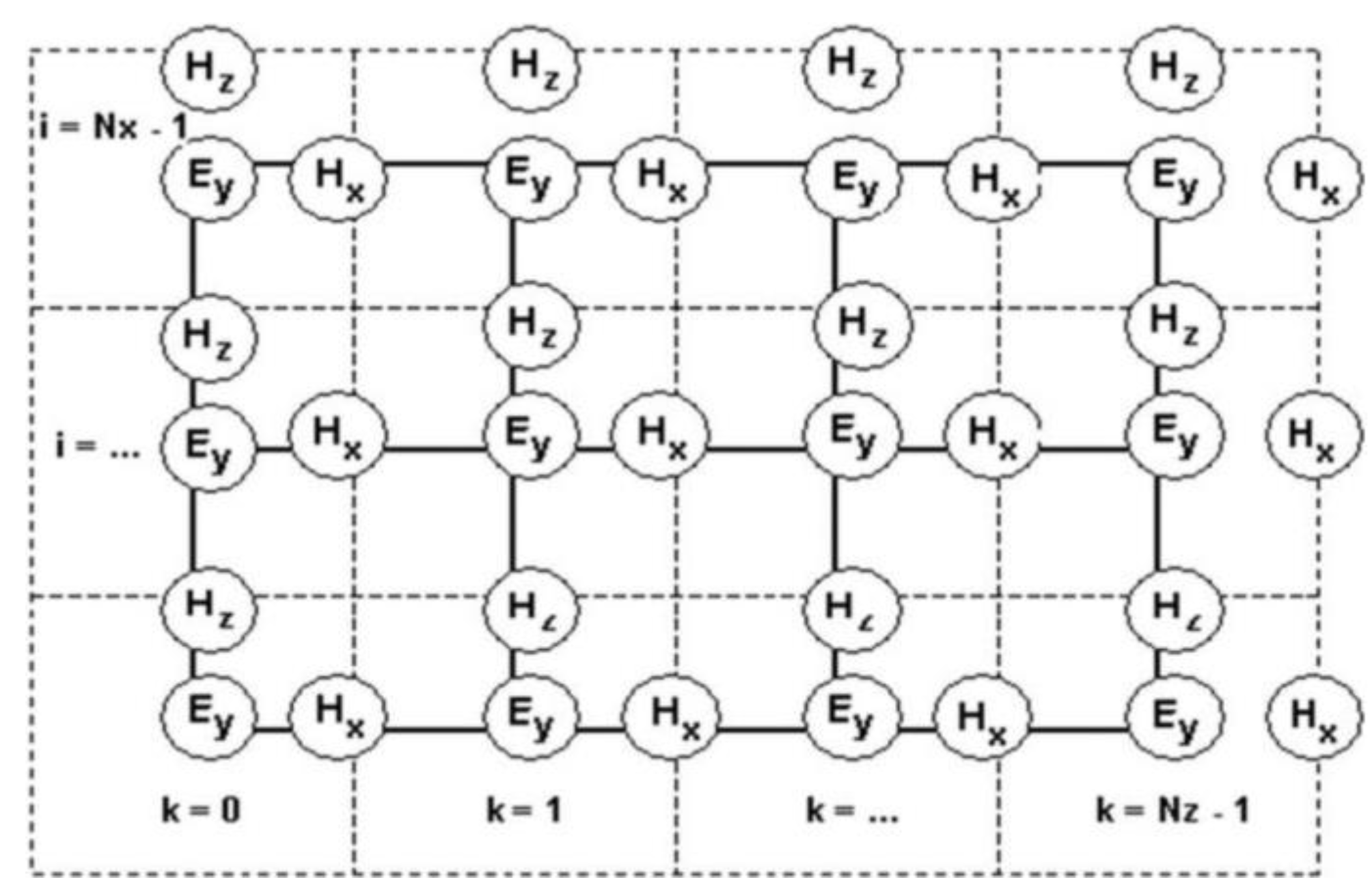

3.4. Evaluation of SERS Enhancement Effects

4. Application of SERS Technology

4.1. Food Additives and Pesticide Residues

4.2. Reaction Process Monitoring

4.3. Biomedical Applications

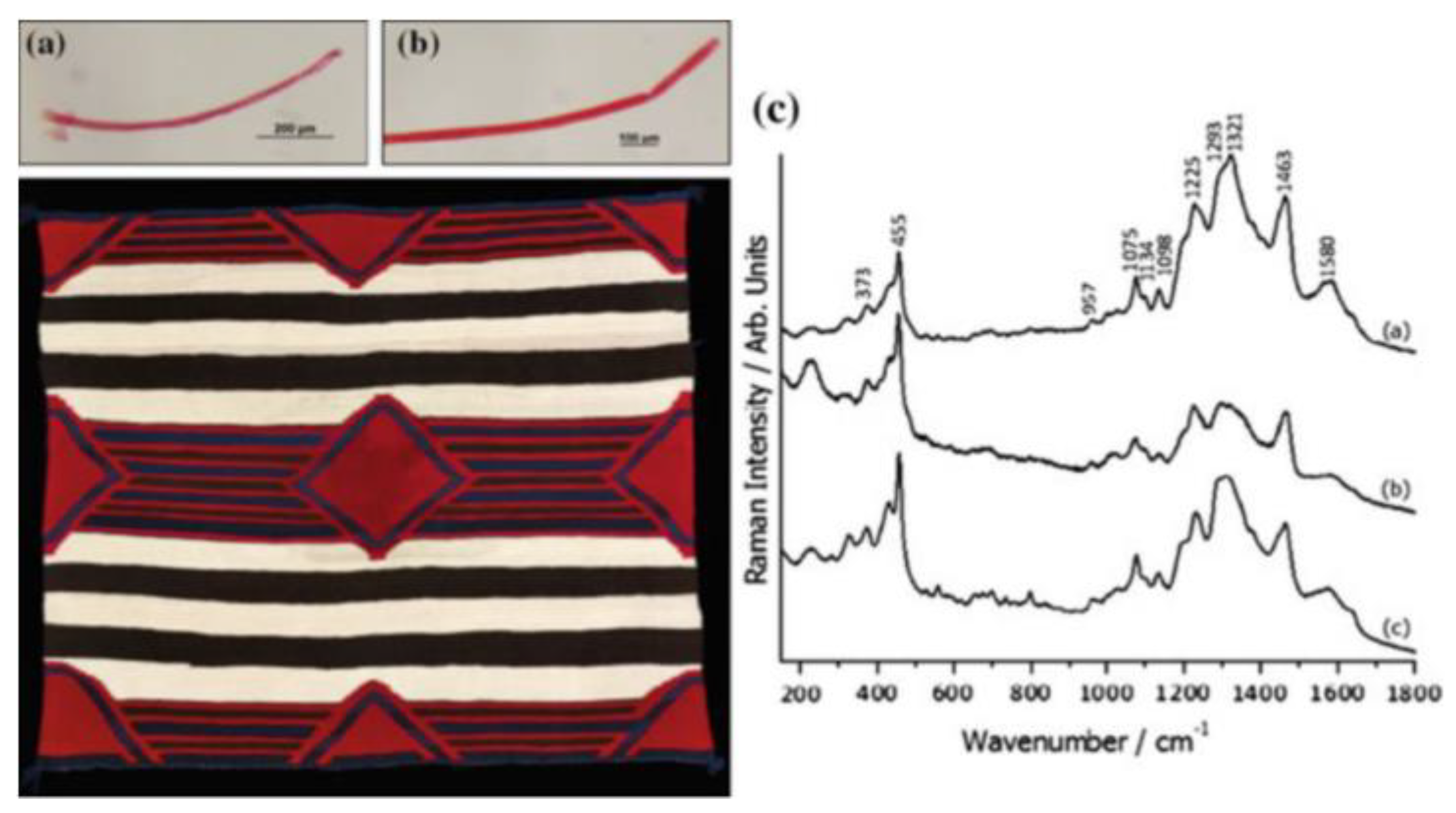

4.4. Archaeology and Art

Conclusions

References

- Smekal, A. Zur quantentheorie der dispersion. Naturwissenschaften 1923, 11, 873–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, C.V.; Krishnan, K.S. A new type of secondary radiation. Nature 1928, 121, 501–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settle, F. Handbook of instrumental techniques for analytical chemistry. Electrical Insulation Magazine IEEE 1997, 14, 42–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks, P.M. Infrared and raman spectroscopy in forensic science; John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Willard., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; HobartH., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Merritt, L. Willard.; HobartH.; Merritt, L. Instrumental methods of analysis; John Wiley & Sons, 1988.

- Ewen, S.; Geoffrey, D. Modern raman spectroscopy: A practical approach; John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Willard, H.H.; Merritt Jr, L.L.; Dean, J.A.; Settle Jr, F.A. Instrumental methods of analysis; CBS Publishers & Distributors, 1988.

- Baena, J.R.; Lendl, B. Raman spectroscopy in chemical bioanalysis. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2004, 8, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudelski, A. Analytical applications of raman spectroscopy. Talanta 2008, 76, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albraheem, L.; Al-Khalifa, H.S. Raman spectroscopy for chemical analysis; John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

- Sloane, H.J. The technique of raman spectroscopy: A state-of-the-art comparison to infrared. Applied Spectroscopy 1971, 25, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, M.; Hendra, P.J.; McQuillan, A.J. Raman spectra of pyridine adsorbed at a silver electrode. Chemical Physics Letters 1974, 26, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanmaire, D.L.; Van Duyne, R.P. Surface raman spectroelectrochemistry: Part i. Heterocyclic, aromatic, and aliphatic amines adsorbed on the anodized silver electrode. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 1977, 84, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht M, G.; Creighton J, A. Anomalously intense raman spectra of pyridine at a silver electrode. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1977, 99, 5215–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Zhu, T.; Liu, Z. Approaching the electromagnetic mechanism of surface-enhanced raman scattering: From self-assembled arrays to individual gold nanoparticles. Chemical Society Reviews 2011, 40, 1296–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, N.; Chapelle, M.L. The electromagnetic effect in surface enhanced raman scattering: Enhancement optimization using precisely controlled nanostructures. J Quant Spectrosc Ra 2012, 113, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, W. Interfaces and thin films as seen by bound electromagnetic waves. Annu Rev Phys Chem 1998, 49, 569–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskovits, M. Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy: A brief retrospective. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2010, 36, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovits, M.; DiLella, D.P.; Maynard, K.J. Surface raman spectroscopy of a number of cyclic aromatic molecules adsorbed on silver: Selection rules and molecular reorientation. Langmuir 1988, 4, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, A.; Brus, L.E. Theoretical model for enhanced photochemistry on rough surfaces. Journal of Chemical Physics 1981, 75, 2205–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrell, R.L. Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry 2008, 1, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.K.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Z. Y., L. Plasmon-enhanced light-matter interactions and applications. NPJ Computational Materials 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewskh, S.; Skonieczny, J. Roughness effects in surface enhanced raman scattering-evidence for electromagnetic and charge transfer enhancement mechanism. Acta Physica Polonica 1991, 80, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, E.J.; Schatz, G.C. An accurate electromagnetic theory study of surface enhancement factors for silver, gold, copper, lithium, sodium, aluminum, gallium, indium, zinc, and cadmium. Journal of Physical Chemistry 1987, 91, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polavarapu, L.; Liz-Marzán, L.M. Growth and galvanic replacement of silver nanocubes in organic media. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 4355–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, J.H.; Jia, H.Y.; Li, M.J.; J. B., Z.; Yang, B.; Zhao, B.; Xu, W.Q.; Lombardi, J.R. Mercaptopyridine surface-functionalized cdte quantum dots with enhanced raman scattering properties. J Phys Chem C 2008, 112, 996–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiohara, A.; Wang, Y.S.; Liz-Marzan, L.M. Recent approaches toward creation of hot spots for sers detection. J Photoch Photobio C 2014, 21, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; M., T.; Huang, Z.R.; Jiang, D.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Zhou, F.; Nogami, M. Controlled fabrication of silver nanoneedles array for sers and their application in rapid detection of narcotics. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 2663–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Ru, E.C.; Grand, J.; Sow, I.; Somerville, W.R.; Etchegoin, P.G.; Treguer-Delapierre, M.; Charron, G.; Felidj, N.; Levi, G.; Aubard, J. A scheme for detecting every single target molecule with surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. Nano Letters 2011, 11, 5013–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakonen, A.; Svedendahl, M.; Ogier, R.; Yang, Z.-J. Dimer-on-mirror sers substrates with attogram sensitivity fabricated by colloidal lithography. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 9405–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brus. ; Louis. Noble metal nanocrystals:Plasmon electron transfer photochemistry and singlemolecule raman spectroscopy. Accounts of Chemical Research 2008, 41, 1742–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Muhammed, A.C.; Baik, S.; Kim, J. Silver nanoflowers for single-particle sers with 10 pm sensitivity. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 465705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Timur. ; Shegai.; Alexan.; Vaskevich; Israel; Rubinstein; Gilad; Haran. Raman spectroelectrochemistry of molecules within individual electromagnetic hot spots. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131, 14390–14398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, S.L.; Frontiera, R.R.; Henry, A.I.; Dieringer, J.A.; Van Duyne, R.P. Creating, characterizing, and controlling chemistry with sers hot spots. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2013, 15, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metiu, H. Surface enhanced spectroscopy. Progress in Surface Science 1984, 17, 153–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valley, N.; Greeneltch, N.; Van Duyne, R.P.; Schatz, G., C. A look at the origin and magnitude of the chemical contribution to the enhancement mechanism of surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy (sers): Theory and experiment. J Phys Chem Lett 2013, 4, 2599–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikin, S.K.; Olivares-Amaya, R.; Rappoport, D.; Stopa, M.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. On the chemical bonding effects in the raman response: Benzenethiol adsorbed on silver clusters. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2009, 11, 9401–9411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneipp, K.; Kneipp, H.; Itzkan, I.; Dasari, R.R.; Feld, M.S. Ultrasensitive chemical analysis by raman spectroscopy. Chemical Reviews 1999, 99, 2957–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Avouris, P. Introduction to carbon materials research. Top Appl Phys 2001, 80, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, S.B.; Swan, A.K.; Unlu, M.S.; Goldberg, B.B.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Tinkham, M. Measuring the uniaxial strain of individual single-wall carbon nanotubes: Resonance raman spectra of atomic-force-microscope modified single-wall nanotubes. Physical Review Letters 2004, 93, 167401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, A. The ‘chemical’ (electronic) contribution to surface-enhanced raman scattering. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2005, 36, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, A.; Kambhampati, P. Surface-enhanced raman scattering. Chemical Society Reviews 1998, 27, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, A.; Ivanecky III, J.E.; Child, C.M.; Foster, M. On the mechanism of chemical enhancement in surface-enhanced raman scattering. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1995, 117, 11807–11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.L.; Jensen, L.; Schatz George, C. Surface-enhanced raman scattering of pyrazine at the junction between two ag20 nanoclusters. Nano Letters 2006, 6, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, K. Numerical solution of initial boundary value problems involving maxwell's equations in isotropic media. IEEE Transactions on Antennas 1966, 14, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, K.S.; Luebbers, R.J. The finite difference time domain method for electromagnetics; CRC Press, 1993.

- Krug, J.T.; Sanchez, E.J.; Xie, X.S. Design of near-field optical probes with optimal field enhancement by finite difference time domain electromagnetic simulation. Journal of Chemical Physics 2002, 116, 10895–10901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.M. Electromagnetic simulation using the fdtd method; John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

- Futamata, M.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Local electric field and scattering cross section of ag nanoparticles under surface plasmon resonance by finite difference time domain method. J Phys Chem B 2003, 107, 7607–7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futamata, M.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Microscopic morphology and sers activity of ag colloidal particles. Vib Spectrosc 2002, 30, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.H. The pstd algorithm: A time-domain method requiring only two cells per wavelength. Microwave and Optical Technology Letters 1997, 15, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.H. Pml and pstd algorithm for arbitrary lossy anisotropic media. IEEE Microwave and Guided Wave Letters 1999, 9, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mishchenko, M. Light scattering by randomly oriented axially symmetric particles. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 1991, 8, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchenko, M.I.; Travis, L.D.; Mackowski, D.W. T-matrix computations of light scattering by nonspherical particles: A review. J Quant Spectrosc Ra 1996, 55, 535–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottmann, J.P.; Martin, O.J.; Smith, D.R.; Schultz, S. Plasmon resonances of silver nanowires with a nonregular cross section. Physical Review B 2001, 64, 235402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micic, M.; Klymyshyn, N.; Suh, Y.D.; Lu, H.P. Finite element method simulation of the field distribution for afm tip-enhanced surface-enhanced raman scanning microscopy. J Phys Chem B 2003, 107, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottmann, J.P.; Martin, O.J. F.; Smith, D.R.; Schultz, S. Dramatic localized electromagnetic enhancement in plasmon resonant nanowires. Chemical Physics Letters 2001, 341, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Geshev, P.; Witting, T.; Dickmann, K.; Hietschold, M. Enhanced raman scattering in the near field of a scanning tunneling tip-an approach to single molecule raman spectroscopy. Electrochemistry 2003, 71, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demming, F.; Jersch, J.; Dickmann, K.; Geshev, P.I. Calculation of the field enhancement on laser-illuminated scanning probe tips by the boundary element method. Appl Phys B-Lasers O 1998, 66, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, E.; Schatz, G.C. Electromagnetic fields around silver nanoparticles and dimers. Journal of Chemical Physics 2004, 120, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H.; Schatz, G.C.; Van Duyne, R.P. Discrete dipole approximation for calculating extinction and raman intensities for small particles with arbitrary shapes. Journal of Chemical Physics 1995, 103, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futamata, M.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Critical importance of the junction in touching ag particles for single molecule sensitivity in sers. J Mol Struct 2005, 735, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubre, C.; Nordlander, P. Finite-difference time-domain studies of the optical properties of nanoshell dimers. J Phys Chem B 2005, 109, 10042–10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futamata, M.; Maruyama, Y.; Ishikawa, M. Metal nanostructures with single molecule sensitivity in surface enhanced raman scattering. Vib Spectrosc 2004, 35, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.M.; Cui, Y.; Xu, Y.H.; Ren, B.; Tian, Z.Q. Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy: Substrate-related issues. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2009, 394, 1729–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leru, E.C.; Blackie, E.; Meyer, M.; Etchegoin, P.G. Surface enhanced raman scattering enhancement factors: A comprehensive study. J Phys Chem C 2007, 111, 13794–13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ye, S.; Luo, X. Sensitive sers detection of mirna via enzyme-free DNA machine signal amplification. Chemical Communications 2016, 52, 10269–10272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.L.; Liu, R.Y.; Han, G.M.; Zhang, Z.P. A chemically reactive raman probe for ultrasensitively monitoring and imaging the in vivo generation of femtomolar oxidative species as induced by anti-tumor drugs in living cells. Chemical Communications 2013, 49, 6647–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlacker, P. Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy: Concepts and chemical applications. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2014, 53, 4756–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.C.; Zhang, A.M.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, D.X. Nanomaterial-based sers sensing technology for biomedical application. J Mater Chem B 2019, 7, 3755–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, S.Z.; Huo, Y.Y.; T. Y., N.; Liu, A.H.; Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Wang, M.H.; Li, C.H.; Man, B.Y. 3d silver nanoparticles with multilayer graphene oxide as a spacer for surface enhanced raman spectroscopy analysis. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 5897–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Wang, Y.S.; You, T.T.; Zhang, X.-J.; Yang, N.; Wang, G.-S.; Yin, P.-G. Interfacial synthesis of a three-dimensional hierarchical mos2-ns@ ag-np nanocomposite as a sers nanosensor for ultrasensitive thiram detection. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 8879–8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.H.; Liu, D.B.; Wang, Z.H.; X. L., S.; Cui, D.; Chen, X. Picomolar detection of mercuric ions by means of gold-silver core-shell nanorods. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6731–6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.B.; Yin, J.; Zheng, Y.M.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, X.X.; Luo, F.H. Self-assembly of au nanoparticles on pmma template as flexible, transparent, and highly active sers substrates. Analytical chemistry 2014, 86, 6262–6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.M.; Liu, Y.N. Surface-enhanced raman detection of melamine on silver-nanoparticle-decorated silver/carbon nanospheres: Effect of metal ions. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2011, 3, 3091–3096. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Sun, M.; Xu, L.; Wang, L.; Kuang, H.; Xu, C. A sers active gold nanostar dimer for mercury ion detection. Chemical Communications 2013, 49, 4989–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Yue, W.; Tanabe, I.; Han, X.; Zhao, B.; Ozaki, Y. Semiconductor-driven "turn-off" surface-enhanced raman scattering spectroscopy: Application in selective determination of chromium (vi) in water. Chemical Science 2015, 6, 342–348. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Chen, N.; Su, Y.Y. Silicon nanohybrid-based sers chips armed with an internal standard for broad-range, sensitive and reproducible simultaneous quantification of lead(ii) and mercury(ii) in real systems. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 4010–4018. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.L.; Bantz, K.C.; Haynes, C.L. Partition layer-modified substrates for reversible surface-enhanced raman scattering detection of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2009, 394, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

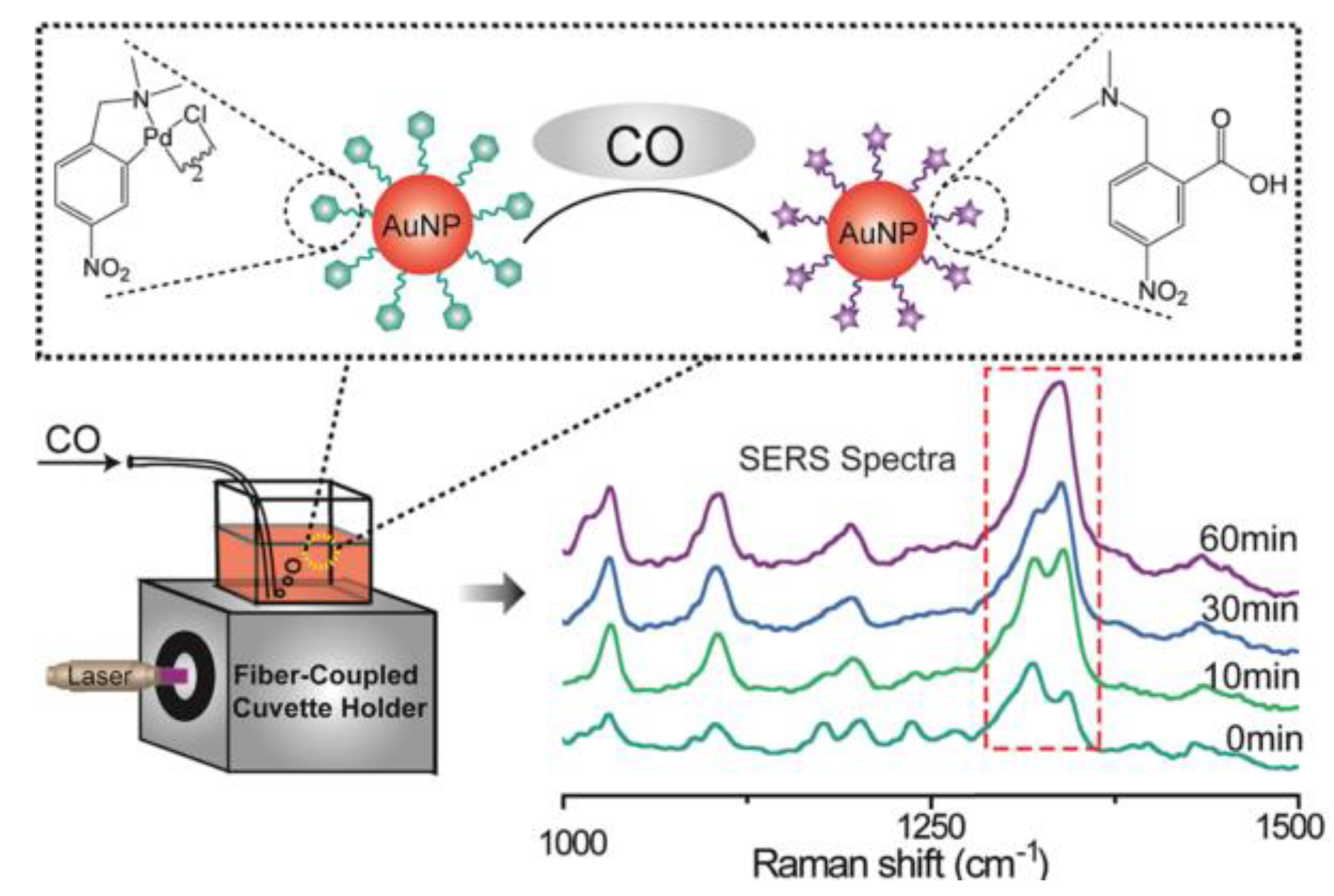

- Hu, K.; Li, D.W.; Cui, J.; Cao, Y.; Long, Y.-T. In situ monitoring of palladacycle-mediated carbonylation by surface enhanced raman spectroscopy. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 97734–97737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhao, H. 3d fe3o4@au@ag nanoflowers assembled magnetoplasmonic chains for in situ sers monitoring of plasmon-assisted catalytic reactions. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2016, 4, 8866–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Li, D.; Zhu, L.; Yang, W. A new plasmonic pickering emulsion based sers sensor for in situ reaction monitoring and kinetic study. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2016, 4, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Parchur, A.K.; Zhou, A. In vitro biomechanical properties, fluorescence imaging, surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy, and photothermal therapy evaluation of luminescent functionalized camoo4 : Eu@au hybrid nanorods on human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials 2016, 17, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

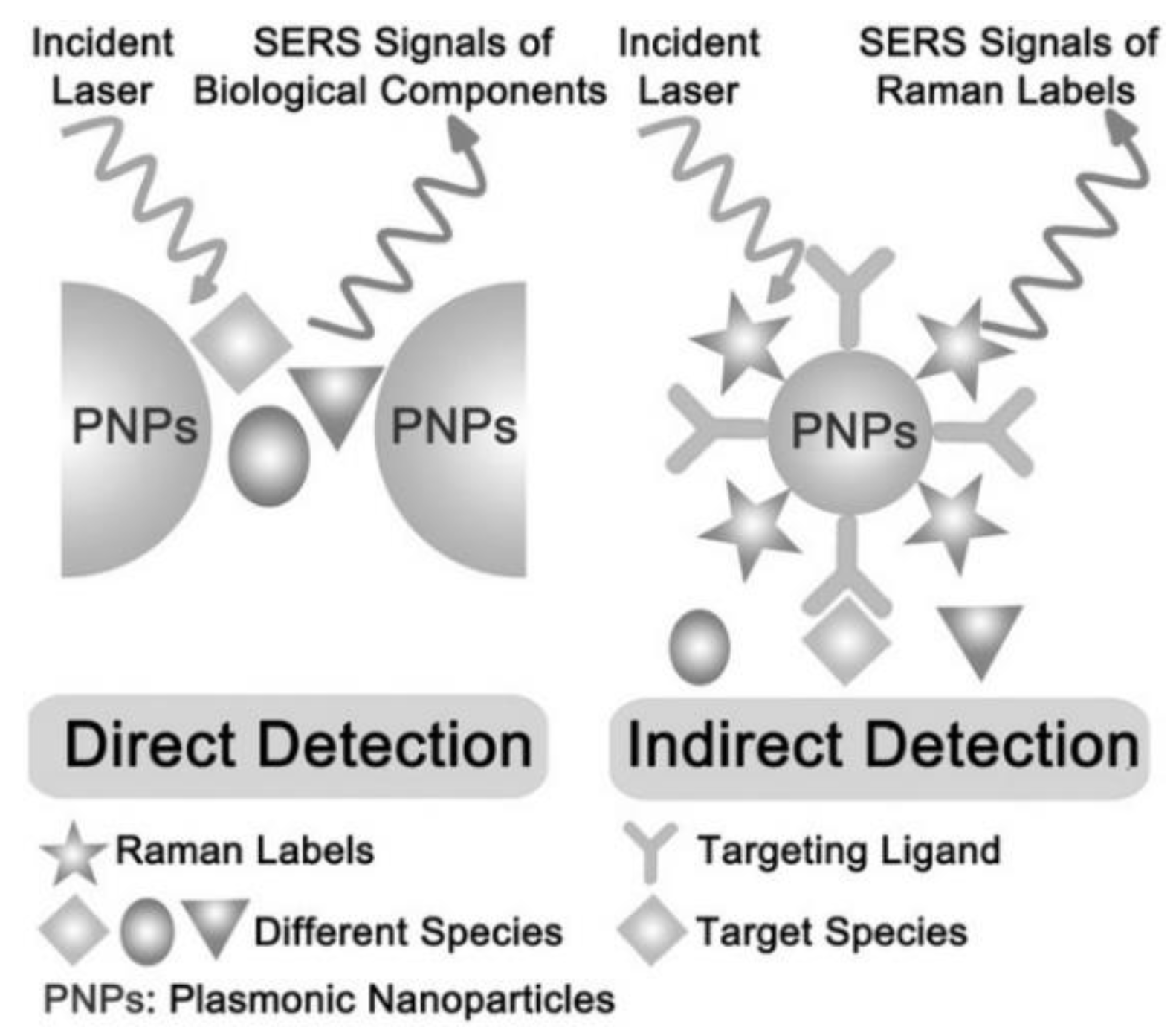

- Moore, T.J.; Moody, A.S.; Payne, T.D.; Sarabia, G.M.; Daniel, A.R.; Sharma, B. In vitro and in vivo sers biosensing for disease diagnosis. Biosensors 2018, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldavnekar, R.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Tan, B. Non plasmonic semiconductor quantum sers probe as a pathway for in vitro cancer detection. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HU, K.; LI, W.D.; Cui, J.; Cao, Y. In situ monitoring of palladacycle-mediated carbonylation by surface enhanced raman spectroscopy. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 97734–97737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.S.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, M.X.; X. , W.; B., R. Raman imaging from microscopy to nanoscopy, and to macroscopy. Small 2015, 11, 3395–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, A.; Tamer, U.; Caykara, T. Sers detection of hepatitis b virus DNA in a temperature-responsive sandwich-hybridization assay. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2017, 48, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourpa, I.; Morjani, H.; Riou, J.F.; Manfait, M. Intracellular molecular interactions of antitumor drug amsacrine (m-amsa) as revealed by surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. FEBS Letters 1996, 397, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.W.; Jin, R.; Mirkin, C.; Northwestern, U. Nanoparticles with raman spectroscopic fingerprints for DNA and rna detection. Science 2002, 297, 1536–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.W.; Li, X.W.; Xu, H.Y.; Zhou, Y.G.; Gu, R.A. A non-resonance surface-enhanced raman spectroscopic study of hemin on a roughened silver electrode. Guang Pu Xue Yu Guang Pu Fen Xi 2003, 23, 294–296. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Hung, H.C.; Sinclair, A.; Z. , P.; Tao, B.; Galvan, D.D.; Jain, P.; Li, B.; Jiang, S.; Yu, Q. Hierarchical zwitterionic modification of a sers substrate enables real-time drug monitoring in blood plasma. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13437. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.S.; Hu, P.; Cui, Y.; Zong, C.; Feng, J.-M.; Wang, X.; Ren, B. Bsa-coated nanoparticles for improved sers-based intracellular ph sensing. Analytical chemistry 2014, 86, 12250–12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, L.A.; Bray, F.; Siegel, R.L.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics. CA-A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2015, 65, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, O.; Sendur, M.A.; Ozdemir, N.; Aksoy, S. Targeted therapies in gastric cancer and future perspectives. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2016, 22, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, T.; Lu, Q.; Yan, X.; Zhong, D.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, Y.; Han, Y.; Cui, D.; Li, X.; Huang, L. Sea-urchin-like au nanocluster with surface-enhanced raman scattering in detecting epidermal growth factor receptor (egfr) mutation status of malignant pleural effusion. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2015, 7, 359–369. [Google Scholar]

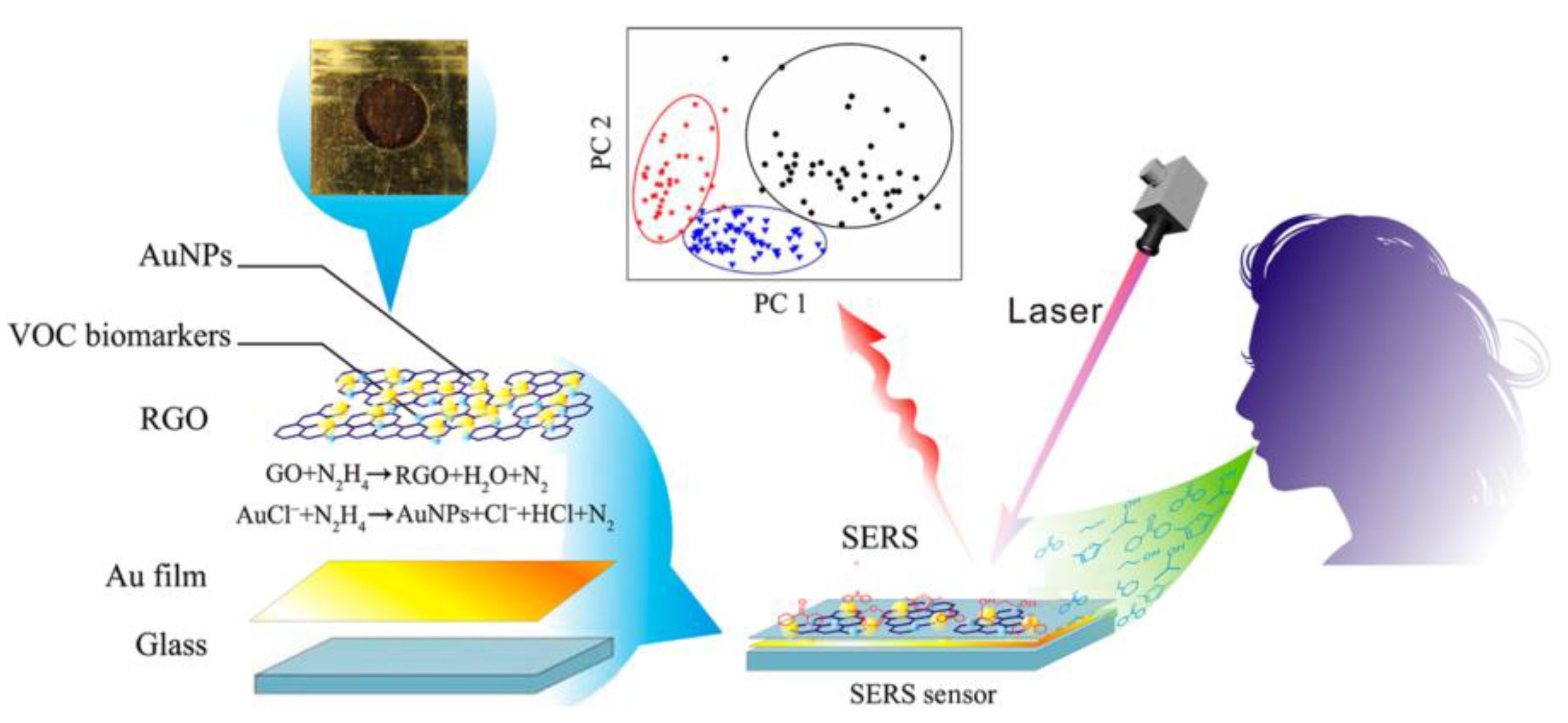

- Hakim, M.; Broza, Y.Y.; Barash, O.; Peled, N.; Phillips, M.; Amann, A.; Haick, H. Volatile organic compounds of lung cancer and possible biochemical pathways. Chemical Reviews 2012, 112, 5949–5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Zhang, Y.X.; Pan, F.; Liu, J. Breath analysis based on surface-enhanced raman scattering sensors distinguishes early and advanced gastric cancer patients from healthy persons. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 8169–8179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, P.; Jie, L.; Cui, D. Breath analysis based on surface enhanced raman scattering sensors distinguishes early and advanced gastric cancer patients from healthy persons. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2018, 10, 8169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, X.M.; Nie, S.M. Surface-enhanced raman nanoparticles for in-vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection. AIP Conference Proceedings 2010, 1267, 81–81. [Google Scholar]

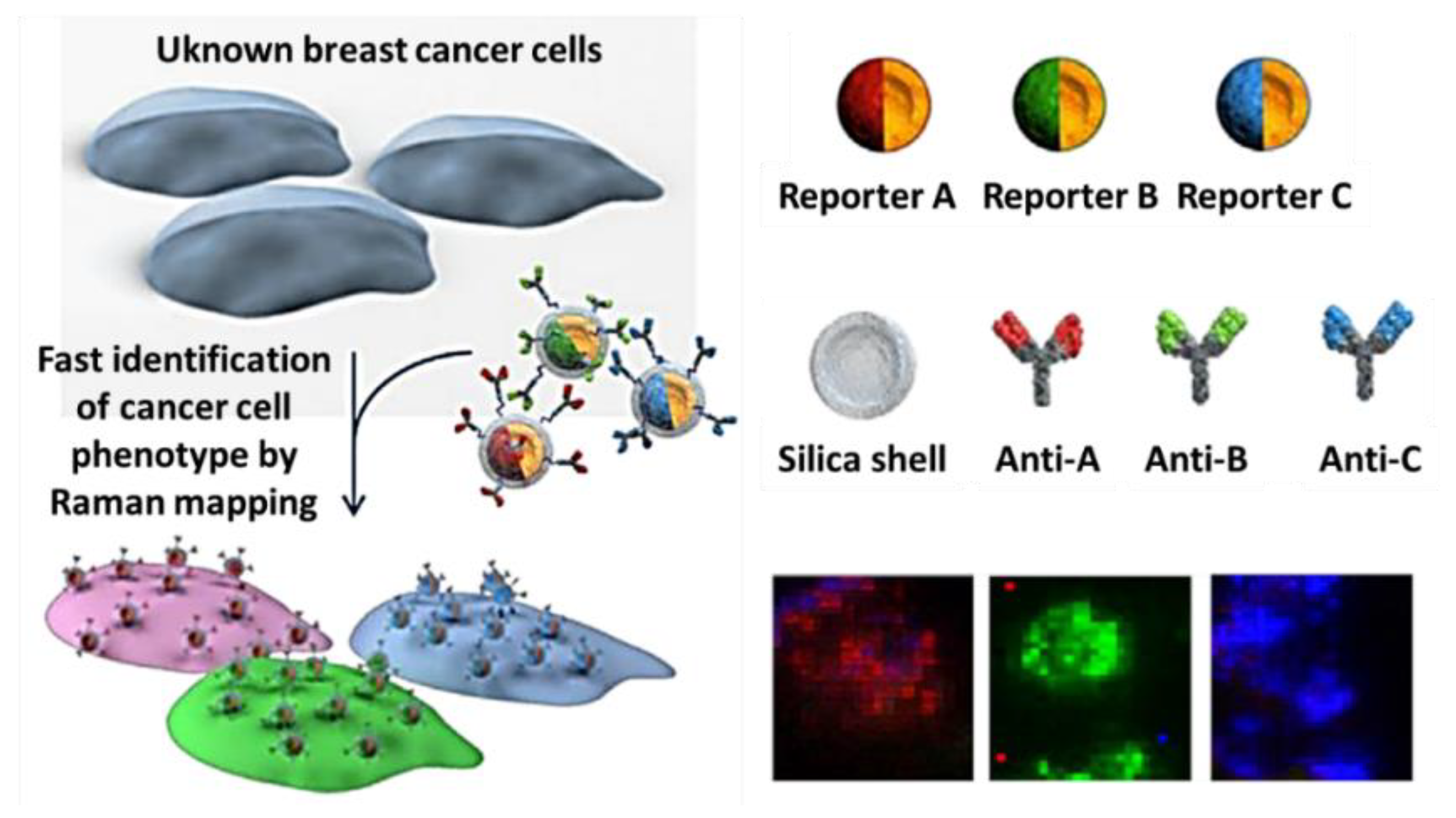

- Lee, S.; Chon, H.; Lee, J.Y. Rapid and sensitive phenotypic marker detection on breast cancer cells using surface-enhanced raman scattering (sers) imaging-sciencedirect. Biosensors 2014, 51, 238–243. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, F.; Zaleski, S.; Casadio, F.; Leona, M.; Duyne, R. Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy: Using nanoparticles to detect trace amounts of colorants in works of art; Nanoscience and Cultural Heritage, 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).