Submitted:

18 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Neurodevelopmental Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Data Presentation and Group Comparison

2.4.2. Linear Regression Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preoperative Data

3.2. Operative and Postoperative Data

3.3. Neurodevelopmental Assessment

3.4. Factors Affecting Neurodevelopment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaynor, J.W.; Stopp, C.; Wypij, D.; Andropoulos, D.B.; Atallah, J.; Atz, A.M.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellinger, D.C.; Wypij, D.; Kuban, K.C.; Rappaport, L.A.; Hickey, P.R.; Wernovsky, G.; et al. Developmental and neurological status of children at 4 years of age after heart surgery with hypothermic circulatory arrest or low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation 1999, 100, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbess, J.M.; Visconti, K.J.; Hancock-Friesen, C.; Howe, R.C.; Bellinger, D.C.; Jonas, R.A. Neurodevelopmental outcome after congenital heart surgery: Results from an institutional registry. Circulation 2002, 106(12 Suppl 1), I95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.J. Neurologic complications of cardiac disease in the newborn. Clin Perinatol 1997, 24, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenezi, A.M.; Albawardi, N.M.; Ali, A.; Househ, M.S.; Elmetwally, A. The epidemiology of congenital heart diseases in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. J Public Health Epidemiol 2015, 7, 232–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger, D.C.; Jonas, R.A.; Rappaport, L.A.; Wypij, D.; Wernovsky, G.; Kuban, K.C.; et al. Developmental and neurologic status of children after heart surgery with hypothermic circulatory arrest or low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass. N Engl J Med 1995, 332, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Cardiac Collaborative on Neurodevelopment (ICCON) Investigators. Impact of operative and postoperative factors on neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2016, 102, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasundaram, P.l Avulakunta, I,D. Bayley Scales Of Infant and Toddler Development. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

- Pizarro, C.; Sood, E.D.; Kerins, P.; Duncan, D.; Davies, R.R.; Woodford, E. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after infant cardiac surgery with circulatory arrest and intermittent perfusion. Ann Thorac Surg 2014, 98, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, B.S.; Lipkin, P.H.; Newburger, J.W.; Peacock, G.; Gerdes, M.; Gaynor, J.W.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012, 126, 1143–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabbutt, S.; Nord, A.S.; Jarvik, G.P.; Bernbaum, J.; Wernovsky, G.; Gerdes, M.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after staged palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, C.S.; Bove, E.L.; Devaney, E.J.; Mollen, E.; Schwartz, E.; Tindall, S.; et al. A randomized clinical trial of regional cerebral perfusion versus deep hypothermic circulatory arrest: outcomes for infants with functional single ventricle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007, 133, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosiorek, A.; Donofrio, M.T.; Zurakowski, D.; Reitz, J.G.; Tague, L.; Murnick, J.; et al. Predictors of neurological outcome following infant cardiac surgery without deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. Pediatr Cardiol 2022, 43, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visconti, K.J.; Rimmer, D.; Gauvreau, K.; del Nido, P.; Mayer, J.E., Jr; Hagino, I.; Pigula, F.A. Regional low-flow perfusion versus circulatory arrest in neonates: one-year neurodevelopmental outcome. Ann Thorac Surg 2006, 82, 2207-2211; discussion 2211-2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, S.; Nord, A.S.; Gerdes, M.; Wernovsky, G.; Jarvik, G.P.; Bernbaum, J.; et al. Predictors of impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes at one year of age after infant cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009, 36, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wypij, D.; Newburger, J.W.; Rappaport, L.A.; duPlessis, A.J.; Jonas, R.A.; Wernovsky, G.; et al. The effect of duration of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest in infant heart surgery on late neurodevelopment: the Boston Circulatory Arrest Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003, 126, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, P.R. Neurologic sequelae associated with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Surg 1998, 65 (6 Suppl), S65-69; discussion S69-70, S74-76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newburger, J.W.; Sleeper, L.A.; Bellinger, D.C.; Goldberg, C.S.; Tabbutt, S.; Lu, M.; et al. Early developmental outcome in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and related anomalies: the single ventricle reconstruction trial. Circulation 2012, 125, 2081–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beca, J. Gunn, J.K.; Coleman, L.; Hope, A.; Reed, P.W.; Hunt, R.W.; et al. New white matter brain injury after infant heart surgery is associated with diagnostic group and the use of circulatory arrest. Circulation 2013, 127, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total patients (n = 23) |

Control (n = 6) |

DHCA (n = 17) |

P-value | |

| Males | 15 (65.22%) | 5 (83.33%) | 10 (58.82%) | 0.37 |

| Age at intervention (days) | 21 (9–82) | 6 (3–35) | 31 (14–103) | 0.05 |

| Weight at intervention (Kg) | 3.2 (2.5–3.6) | 3.5 (2.9–3.7) | 2.8 (2.5–3.6) | 0.40 |

| Down syndrome | 1 (4.35%) | 0 | 1 (5.88%) | >0.99 |

| Prenatal diagnosis | 5 (22.73%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0.10 |

| Preterm labor | 2 (8.7%) | 0 | 2 (11.76%) | >0.99 |

| Socio-economic status Low Middle Upper middle |

12 (57.14%) 7 (33.33%) 2 (9.52%) |

4 (66.67%0 1 (16.67%) 1 (16.67%) |

8 (53.33%) 6 (40%) 1 (6.67%) |

0.50 |

| Father’s education Primary school Secondary school Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree |

1 (4.76%) 10 (47.62%) 9 (42.86%) 1 (4.76%) |

0 1 (16.67%) 4 (66.67%) 1 (16.67%) |

1 (6.67%) 9 (60%) 5 (33.33%) 0 |

0.13 |

| Mother’s education Primary school Middle school Secondary school Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree |

1 (4.76%) 5 (23.81%) 6 (28.57%) 7 (33.33%) 2 (9.52%) |

0 2 (33.33%) 0 3 (50%) 1 (16.67%) |

1 (6.667%) 3 (20%) 6 (40%) 4 (26.67%) 1 (6.67%) |

0.32 |

| Delivery mode Vaginal Cesarean |

16 (69.57%) 7 (30.43%) |

3 (50%) 3 (50%) |

13 (76.47%) 4 (23.53%) |

0.32 |

| Previous non-cardiac surgery | 1 (4.35%) | 0 | 1 (5.88%) | >0.99 |

| Preoperative ventilation (days) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) | 0.56 |

| Total patients (n = 23) |

Control (n = 6) |

DHCA (n = 17) |

P-value | |

| Duration of CPB (minutes) | 68 (56–78) | 101.5 (74–123) | 61 (56–72) | 0.002 |

| Cross-clamp time (minutes) | 45.57 ± 16.52 | 61.67 ± 18.59 | 39.88 ± 11.65 | 0.003 |

| Highest creatinine (μmol/L) | 55 (46–87.8) | 54.5 (49–70) | 68 (42–91) | 0.93 |

| Highest lactate (mmol/L) | 4.67 (0.48) | 4.87 ± 1.14 | 4.6 ± 0.53 | 0.81 |

| Postoperative acidosis | 17 (77.27%) | 3 (50%) | 14 (87.5%) | 0.10 |

| Postoperative hypoxia | 11 (47.83%) | 4 (66.67%) | 7 (41.18%) | 0.37 |

| Mechanical ventilation (days) | 6 (4–8) | 5 (2–7) | 7 (4–12) | 0.29 |

| ECMO | 1 (4.35%) | 0 | 1 (5.88%) | >0.99 |

| Open sternum | 18 (78.36%) | 4 (66.67%) | 14 (82.35%) | 0.58 |

| Open chest duration (days) | 2 (1.5–3) | 3 (1.5–4) | 2 (1.5–3) | 0.53 |

| Postoperative seizures | 1 (4.35%) | 1 (16.67%) | 0 | 0.26 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 4 (17.39%) | 1 (16.67%) | 3 (17.65%) | >0.99 |

| Lowest Ca level (mg/dl) | 2.04 (1.88–2.14) | 1.98 (1.55–2.12) | 2.05 (1.93–2.14) | 0.34 |

| ICU stay (days) | 12 (7–18) | 9 (5–12) | 15 (7–23) | 0.13 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 16 (12–26) | 11.5 (10–14) | 19 (15–46) | >0.99 |

| Surgical re-exploration | 2 (8.7%) | 0 | 2 (11.76%) | >0.99 |

| Blood stream infection | 6 (26.09%) | 0 | 6 (35.29%) | 0.14 |

| Surgical site infection | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (33.33%) | 0 | 0.06 |

| Heart block | 5 (21.74%) | 1 (16.67%) | 4 (23.53%) | >0.99 |

| Chest drain > 5 days | 2 (8.7%) | 0 | 2 (11.76%) | >0.99 |

| Total patients (n = 23) |

Control (n = 6) |

DHCA (n = 17) |

P-value | |

| Age at assessment (days) | 774.78 ± 343.56 | 865 ± 184.36 | 742.94 ± 284.12 | 0.47 |

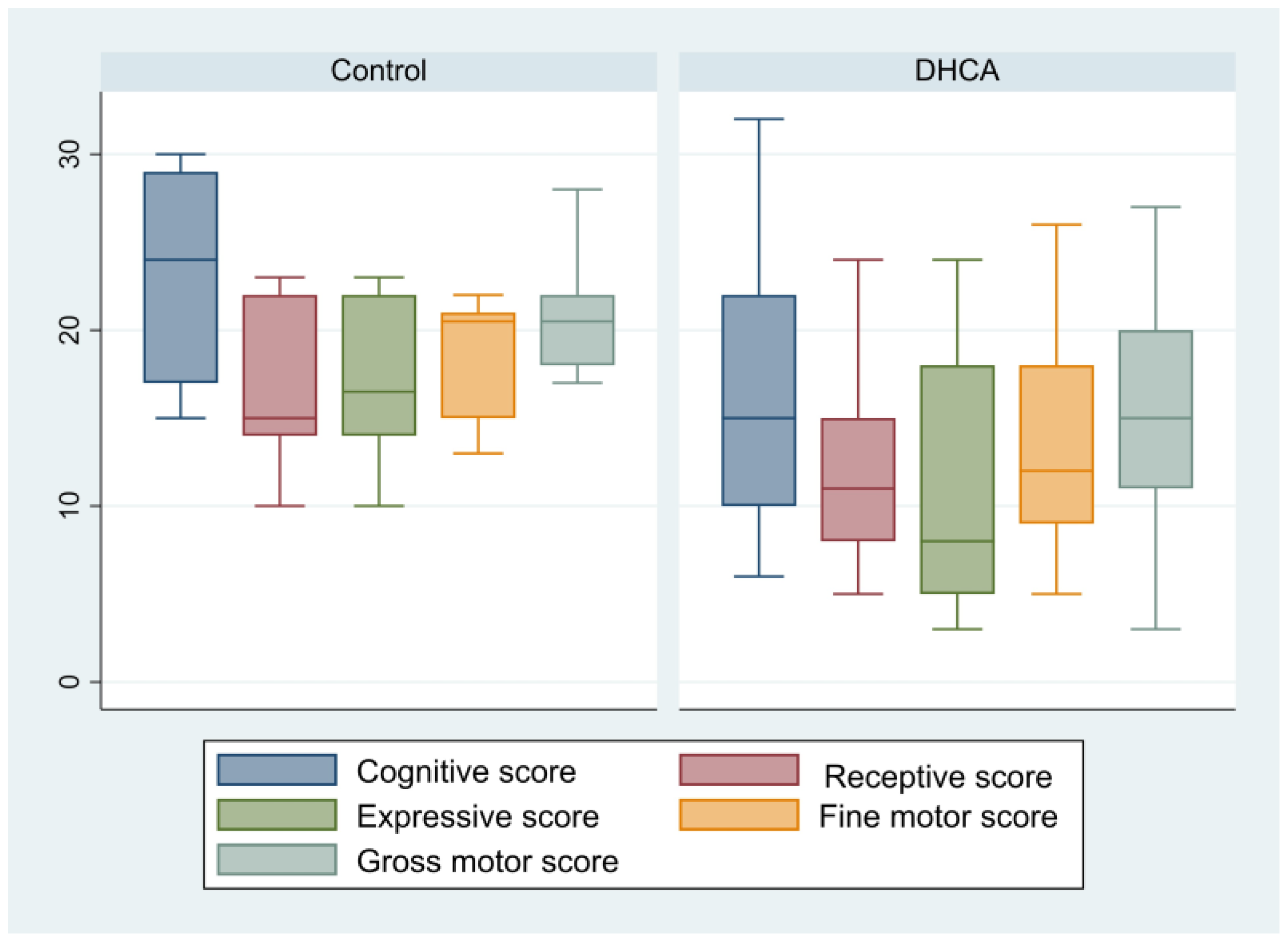

| Cognitive score | 18.26 ± 7.99 | 23.17 ± 6.62 | 16.53 ± 7.87 | 0.08 |

| Cognitive At-risk Emerging Competent |

9 (39.13%) 8 (34.78%) 6 (26.09%) |

1 (16.67%) 3 (50%) 2 (33.33%) |

8 (47.06%) 5 (29.41%) 4 (23.53%) |

0.49 |

| Receptive communication score | 14 (8–15) | 15 (14–22) | 11 (8–15) | 0.17 |

| Receptive communication At-risk Emerging Competent |

6 (26.09%) 10 (43.48%) 7 (30.43%) |

1 (16.67%) 3 (50%) 2 (33.33%) |

5 (29.41%) 7 (41.18%) 5 (29.41%) |

>0.99 |

| Expressive communication score | 12.43 ± 6.91 | 17 ± 4.90 | 10.82 ± 6.89 | 0.06 |

| Expressive communication At-risk Emerging Competent |

9 (39.13%) 8 (34.78%) 6 (26.09%) |

1 (16.67%) 3 (50%) 2 (33.33%) |

8 (47.06%) 5 (29.41%) 4 (23.53%) |

0.49 |

| Fine motor score | 14.91 ± 6.03 | 18.67 ± 3.72 | 13.59 ± 6.21 | 0.08 |

| Fine motor At-risk Emerging Competent |

5 (29.41%) 12 (52.17%) 6 (26.09%) |

0 4 (66.67%) 2 (33.33%) |

5 (29.41%) 8 (47.06%) 4 (23.53%) |

0.46 |

| Gross motor score | 16.26 ± 7.21 | 21 ± 3.90 | 14.59 ± 7.43 | 0.06 |

| Gross motor At-risk Emerging Competent |

9 (39.13%) 7 (30.43%) 7 (30.43%) |

0 3 (50%) 3 (50%) |

9 (52.94%) 4 (23.53%) 4 (23.53%) |

0.05 |

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Cognitive score* | ||||

| Age at assessment (months) | 0.53 (0.32–0.74) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.45–0.74) | <0.001 |

| Preterm | -9.05 (-20.94–2.85) | 0.13 | -13.38 (-19.22–-7.53) | <0.001 |

| CPB duration | 0.11 (-0.02–0.24) | 0.09 | - | |

| DHCA | -6.64 (-14.13–0.86) | 0.08 | - | |

| Receptive communication score** | ||||

| Age at assessment (months) | 0.33 (0.16–0.50) | 0.001 | 0.38 (0.25–0.50) | <0.001 |

| Preterm | -8.24 (-16.45–0.03) | 0.049 | -11 (-15.95–-6.06) | <0.001 |

| CPB | 0.07 (-0.02–0.17) | 0.12 | - | |

| DHCA | -4.03 (-9.52–1.46) | 0.14 | - | |

| Expressive communication score*** | ||||

| Age at assessment (months) | 0.39 (0.17–0.6) | 0.001 | 0.44 (0.26–0.61) | <0.001 |

| Preterm | -8.14 (-18.38–2.09) | 0.11 | -11.35 (-18.3–-4.4) | <0.001 |

| Down syndrome | -9.84 (-24.21–4.49) | 0.17 | - | |

| CPB time | 0.10 (-0.01–0.21) | 0.09 | - | |

| DHCA | -6.18 (-12.57–0.22) | 0.06 | - | |

| Fine motor score **** | ||||

| Age at assessment (months) | 0.39 (0.22–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.32–0.53) | <0.001 |

| Male | -3.78 (-9.13–1.58) | 0.16 | - | |

| Preterm | -8.12 (-16.87–0.63) | 0.07 | -10.62 (-14.68–-6.55) | <0.001 |

| Down syndrome | -8.27 (-20.85–4.30) | 0.19 | - | |

| CPB | 0.07 (-0.28–0.17) | 0.15 | - | |

| DHCA | -5.08 (-10.72–0.56) | 0.08 | -2.1 (-4.70–-0.49) | 0.10 |

| Gross motor score ***** | ||||

| Age at assessment (months) | 0.48 (0.30–0.67) | <0.001 | 0.51 (0.39–0.64) | <0.001 |

| Male | -4.78 (-11.13–1.58) | 0.13 | -10.85 (-15.82–-5.87) | <0.001 |

| Preterm | -7.95 (-18.71–2.81) | 0.14 | - | |

| Down syndrome | -10.73 (-25.63–4.18) | 0.15 | - | |

| CPB | 0.10 (-0.01–0.22) | 0.08 | - | |

| DHCA | -6.41 (-13.09–0.27) | 0.06 | -3.04 (-6.22–-0.14) | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).