Submitted:

18 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights

- Coupling HPLC with ICP-MS is a powerful tool to determine trace amounts of organophosphorus, organosulfur and organoarsenic substances, their derivatives and degradation products in environmental samples.

- HPLC-ICP-MS can be successfully used as a complementary to GC-MS and HPLC-MS techniques to conduct forensic analysis of complex environmental matrices containing CWA and other toxic substances.

1. Introduction

2. HPLC-ICP-MS in the Analysis of Organophosphorus Compounds

2.1. The importance of the analysis of organophosphorus nerve agents, their hydrolysis products, and metabolites

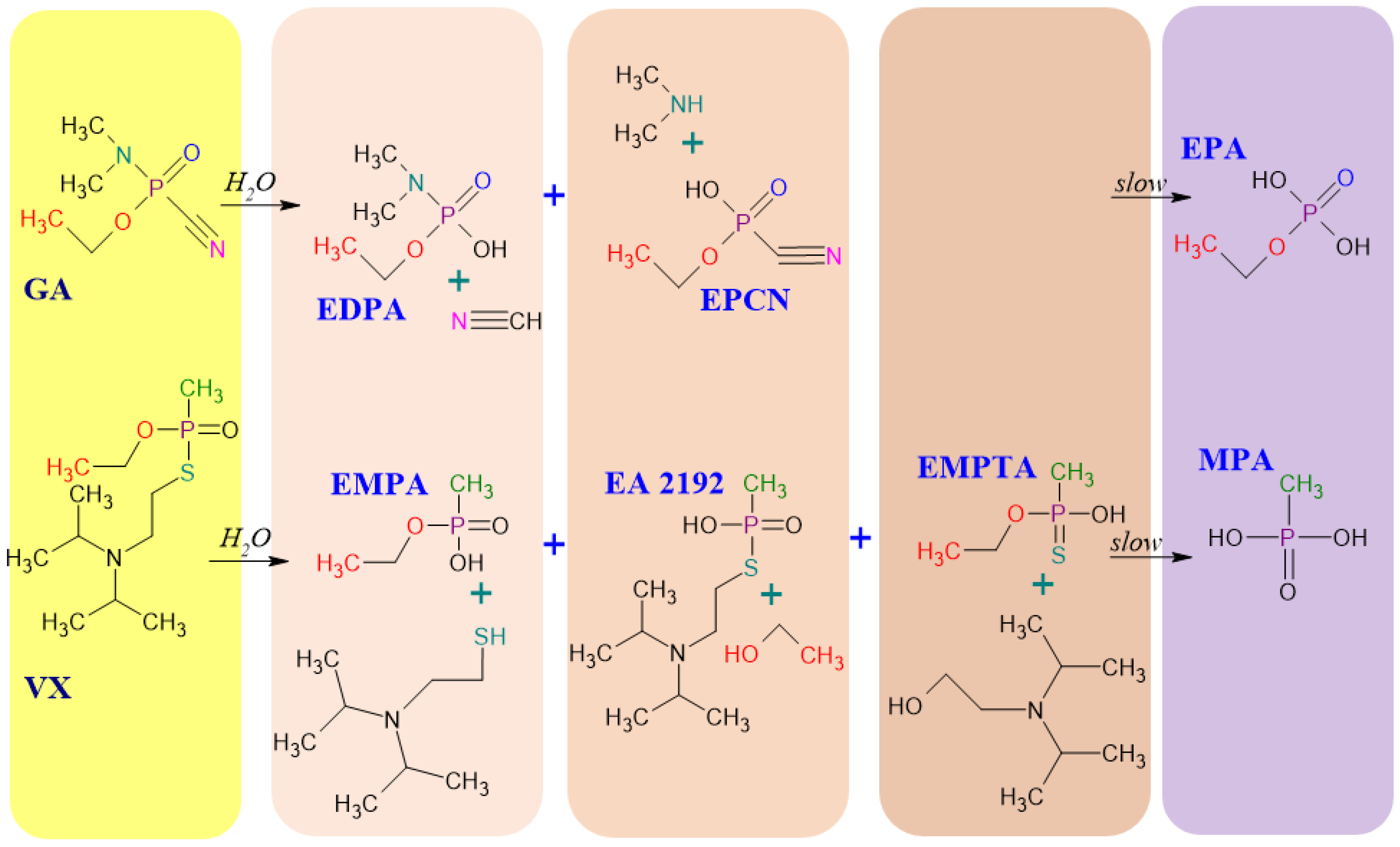

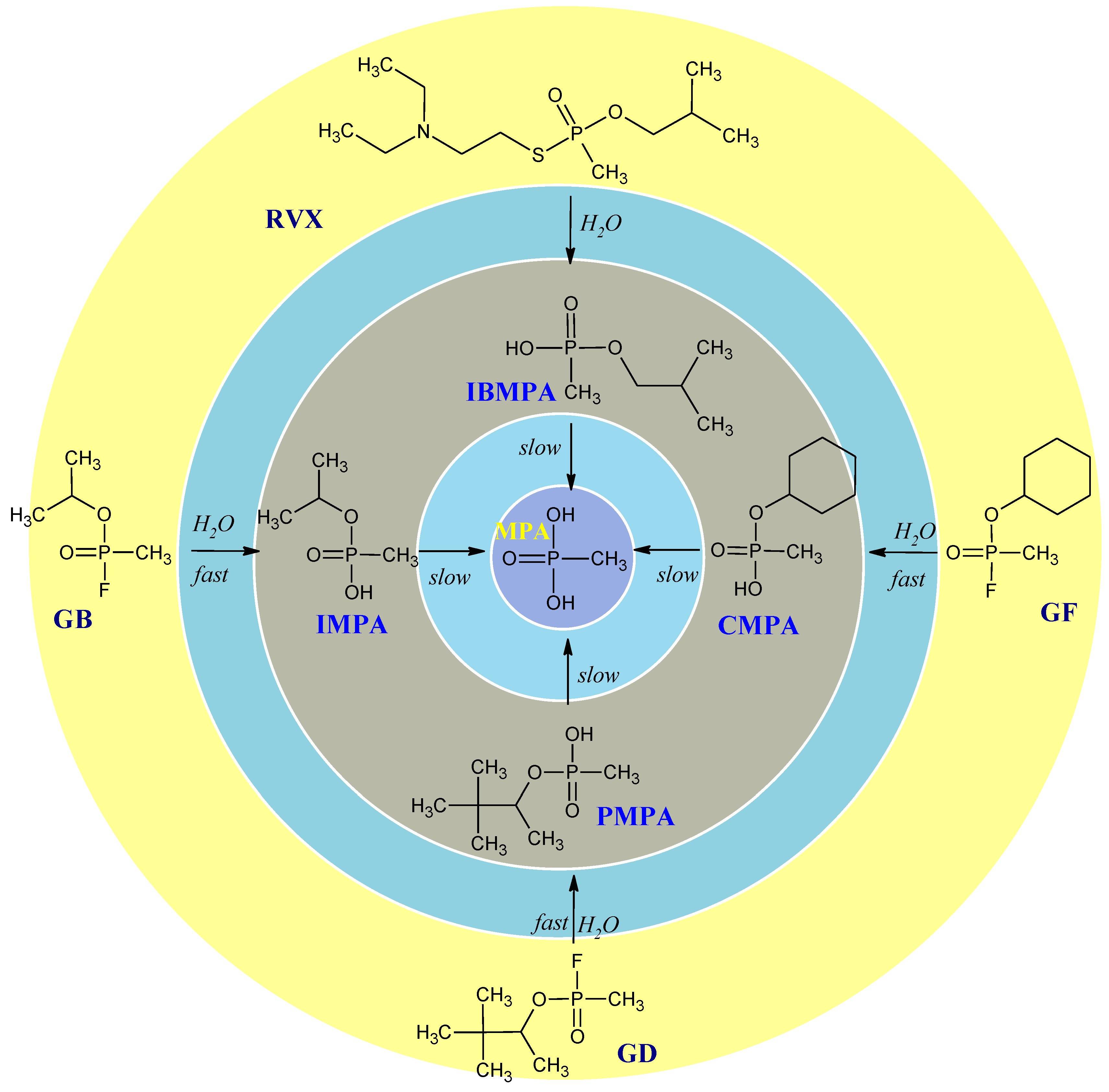

2.2. Hydrolysis of Organophosphorus Based Nerve Agents

2.3. The Use of the HPLC-ICP-MS Technique for the Analysis of Organophosphorus Compounds

3. ICP-MS in the Analysis of Organosulfur Compounds

3.1. The Importance of the Organosulfur Compounds Analysis

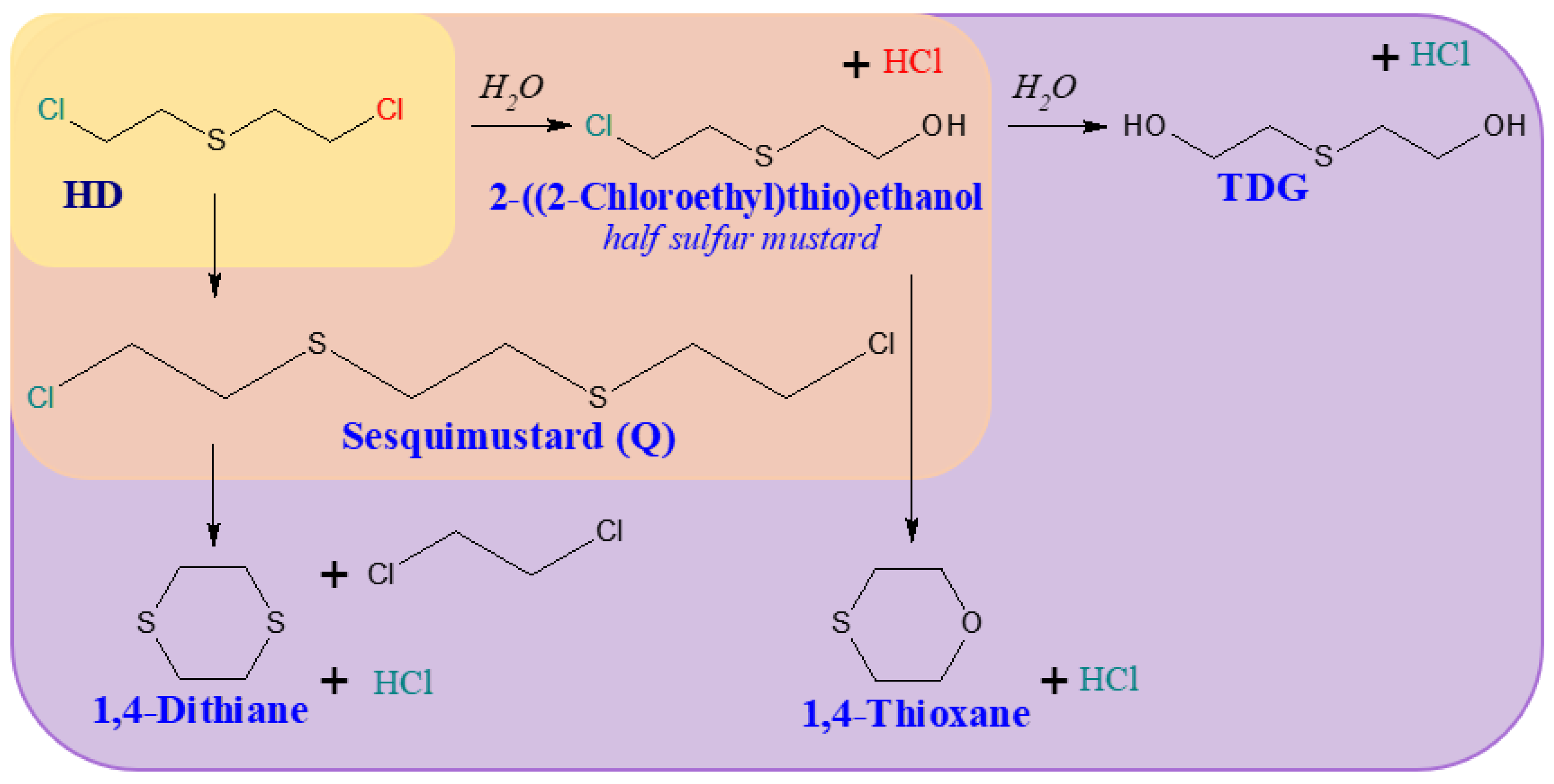

3.2. Degradation Reactions of Organosulfur Compounds

3.3. Use of ICP-MS Technique to Analyze Organosulfur Compounds

4. ICP-MS in the Analysis of Organoarsenic Compounds

4.1. Significance of the Organoarsenic Compounds Analysis

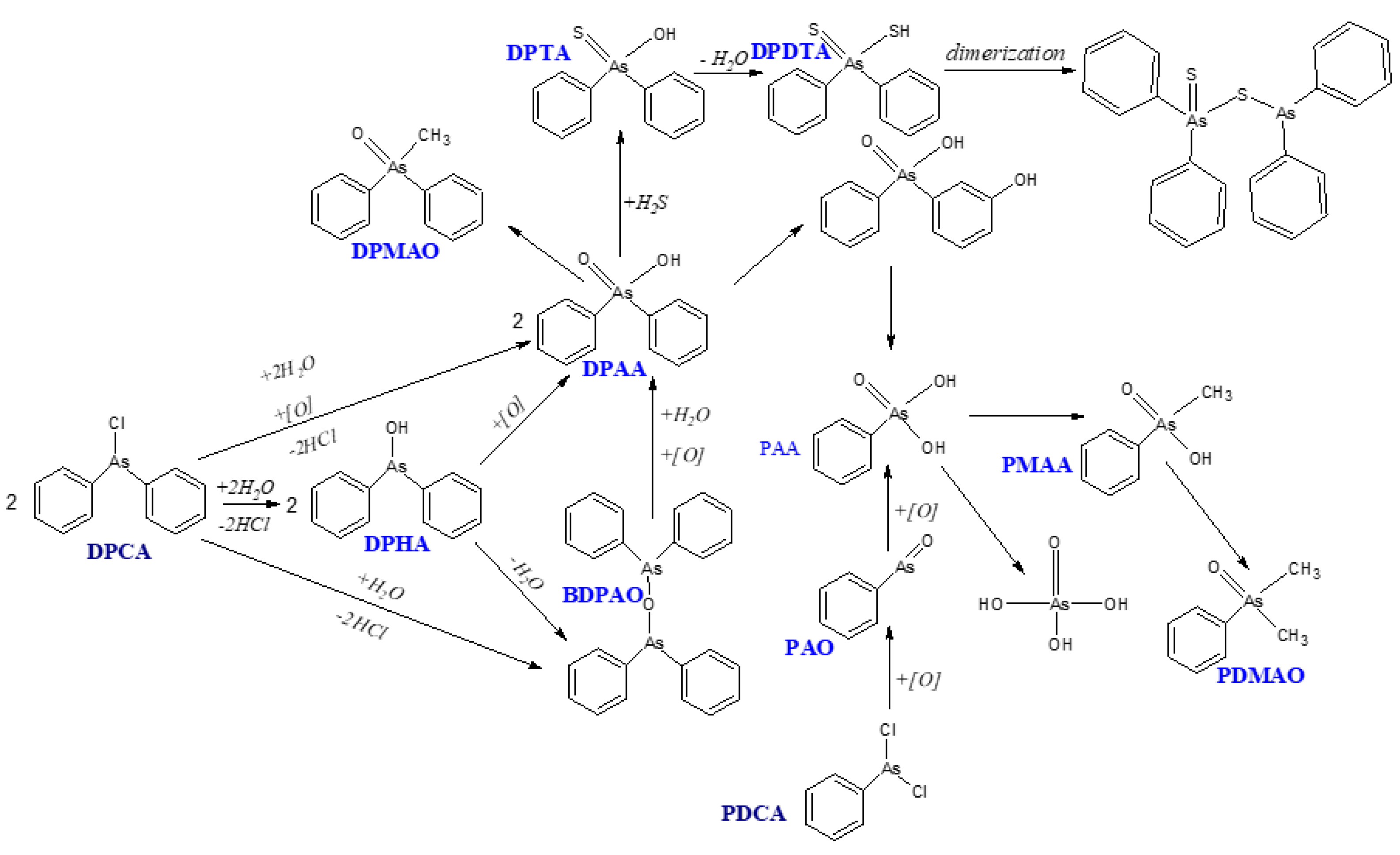

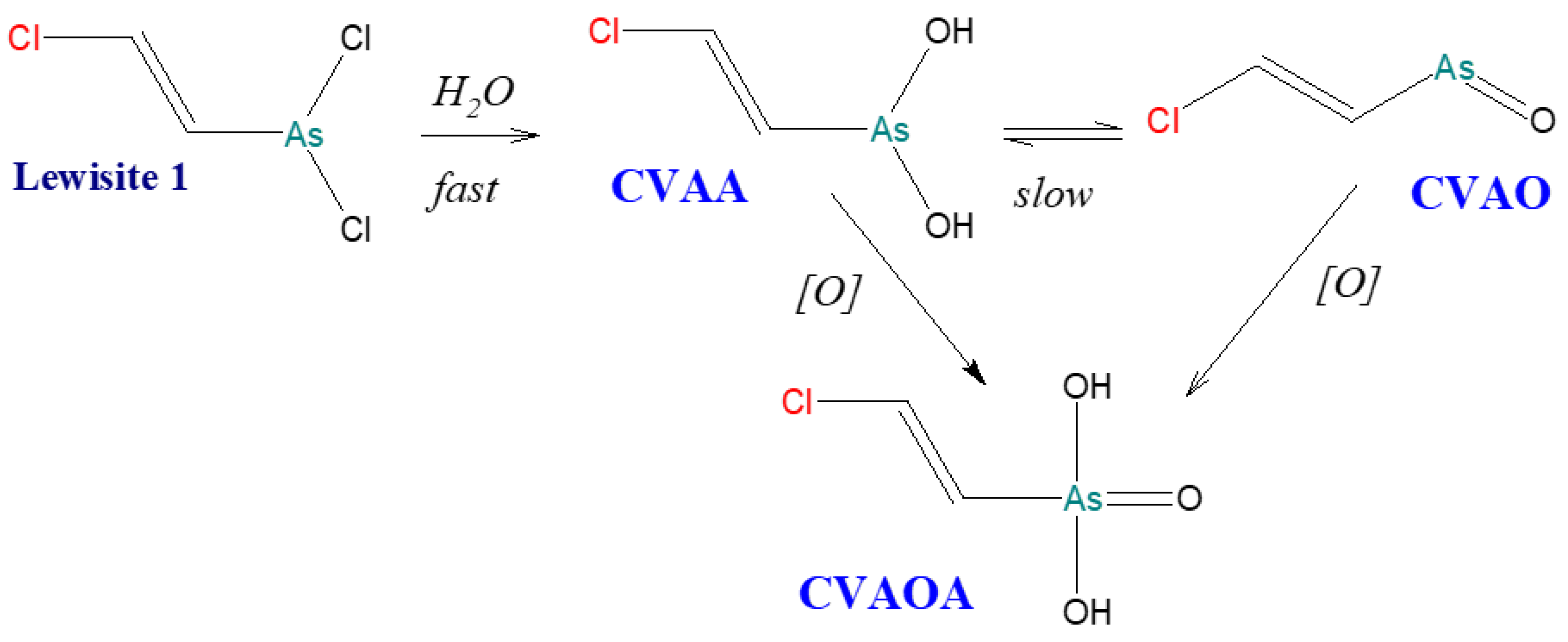

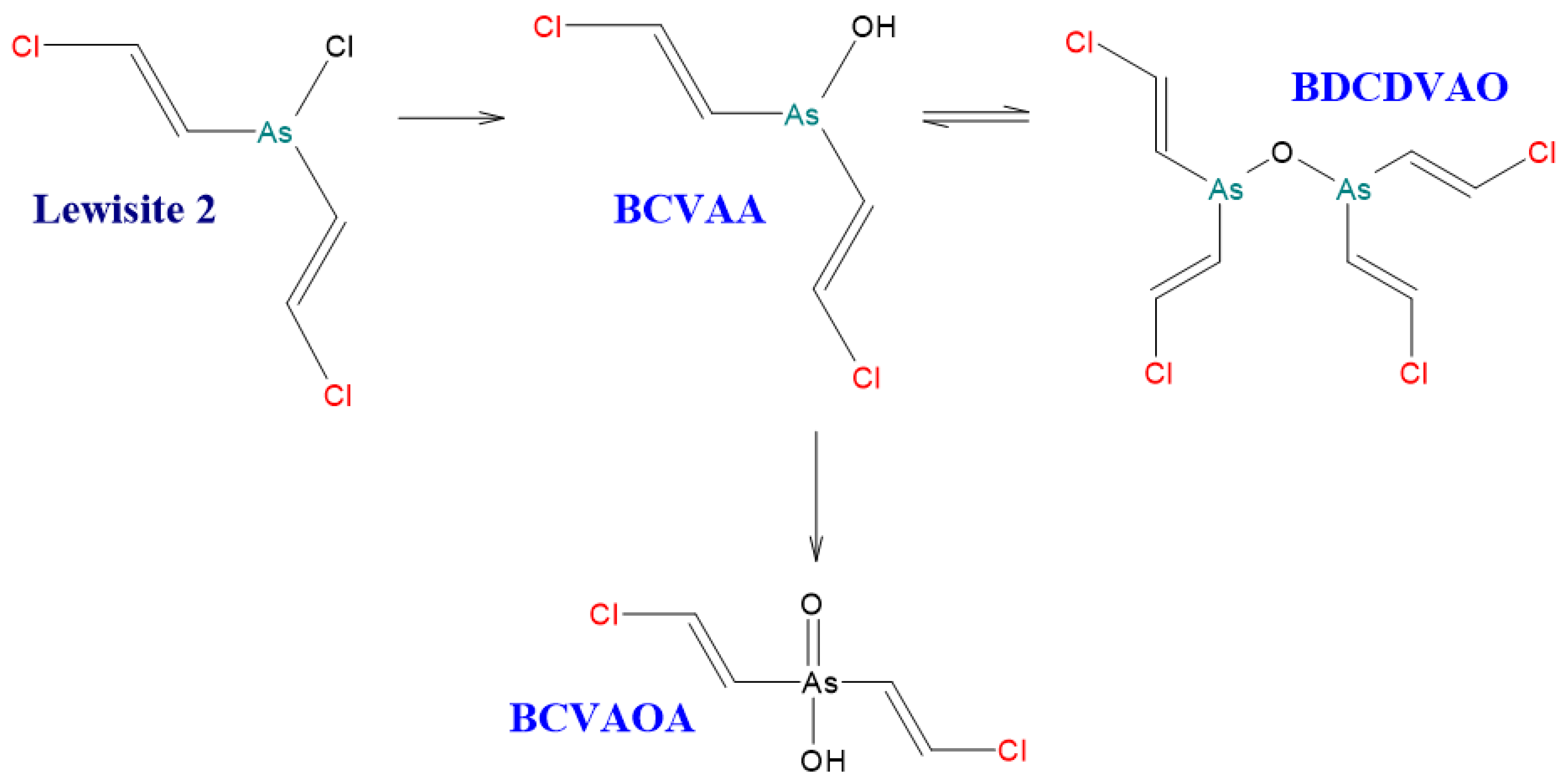

4.2. Degradation Reactions of Organoarsenic Compounds

4.3. The Use of the ICP-MS Technique for the Analysis of Organoarsenic Compounds

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Acronyms

| Acronym and abbreviation | Full name | No CAS |

| AB | Arsenobetaine | 64436-13-1 |

| ACh | Acetylcholine | 51-84-3 |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase | 9000-81-1 |

| APCI | Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization | - |

| BCVAA | Bis(2-chlorovinyl)arsinous acid | NF |

| BDPAO | Bis(diphenylarsine)oxide | 2215-16-9 |

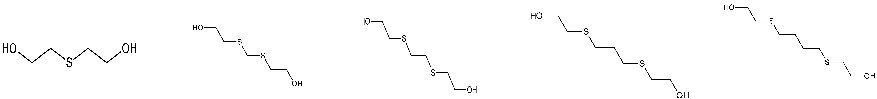

| BHETBu | 1,4-bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)butane | 7425-93-6 |

| BHETE | 1,2-bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)ethane | 5244-34-8 |

| BHETM | Bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)methane | 44860-68-6 |

| BHETPr | 1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)propane | 16260-48-3 |

| CCT | Collision-reaction Cell Technology | - |

| CMPA | Cyclohexyl methylphosphonic acid | 1932-60-1 |

| CVAA | 2-chlorovinylarsenous acid | 85090-33-1 |

| CVAO | 2-chlorovinylarsine oxide | 3088-37-7 |

| CVAOA | 2-chlorovinylarsonic acid | 64038-44-4 |

| CWA | Chemical Warfare Agents | - |

| CWC | Chemical Weapons Convention | - |

| DEHP | Diethylhydrogen phosphate | 598-02-7 |

| DMA (III) | Dimethylarsinous acid | 55094-22-9 |

| DMAA | Dimethylarsinic acid | 75-60-5 |

| DMHP | Dimethylhydrogen phosphate | 813-78-5 |

| DMTA (III) | Dimethylthioarsinous acid | NF |

| DMTA (V) | Dimethyldithioarsinic acid (dimethylarsinodithioic acid) | NF |

| DPAA | Diphenylarsinic acid | 6217-24-9 |

| DPCA | Diphenylchloroarsine | 712-48-1 |

| DPCNA | Diphenylcyanoarsine | 23525-22-6 |

| DPMAO | Diphenylmethylarsine oxide | NF |

| DPTA | Diphenylthioarsinic acid | NF |

| DRC | Dynamic reaction cell | - |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid | 60-00-4 |

| EHDAP | Ethyl hydrogen dimethylamidophosphate sodium salt | NF |

| EMPA | Ethyl methylphosphonic acid | 1832-53-7 |

| EMPTA | Ethyl methylphosphonothioic acid | 18005-40-8 |

| EPA | Ethylphosphonic acid | 6779-09-5 |

| EPCN | Ethylphosphorylcyanidate | NF |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization | - |

| GA | O-Ethyl N,N-dimethyl phosphoramidocyanidate (Tabun) | 77-81-6 |

| GB | Propan-2-yl methylphosphonofluoridate (Sarin) | 107-44-8 |

| GC | Gas Chromatography | - |

| GD | 3,3-Dimethylbutan-2-yl methylphosphonofluoridate (Soman) | 96-64-0 |

| GF | Cyclohexyl methylphosphonofluoridate (Cyclosarin) | 329-99-7 |

| GFAAS | Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy | - |

| HD | bis(2-chloroethyl)sulfide (Sulfur mustard) | 505-60-2 |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography | - |

| IBHMP | Isobutyl hydrogen methylphosphonate | 1604-38-2 |

| IC50 | Median inhibitory concentration | - |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry | - |

| IMPA | Isopropyl methylphosphonic acid | 1832-54-8 |

| IPHEP | Isopropyl hydrogen ethylphosphonate | 170135-50-9 |

| LC | Liquid Chromatography | - |

| MMA (III) | Monomethylarsonous acid | 25400-23-1 |

| MMA (V) | Monomethylarsonic acid | 124-58-3 |

| MPA | Methylphosphonic acid | 993-13-5 |

| MS | Mass spectrometry | - |

| OES | Optical emission spectroscopy | - |

| OPNA | Organophosphorus Nerve Agents | - |

| OPNA DP | Organophosphorus Nerve Agents Degradation Products | - |

| ORS | Octopole Reaction System | - |

| PAA | Phenylarsonic acid | 98-05-5 |

| PAO | Phenylarsine oxide | 637-03-6 |

| PDCA | Phenyldichloroarsine | 696-28-6 |

| PDMAO | Phenyldimethylarsine oxide | NF |

| PMAA | Phenylmethylarsinic acid | NF |

| PMPA | Pinacolyl methylphosphonic acid | 616-52-4 |

| PPA | Propylphosphonic acid | 4672-38-2 |

| ppb | Parts per billion | - |

| ppm | Parts per million | - |

| ppt | Parts per trillion | - |

| PTE | Phosphotriesterase | - |

| QQQ | Triple quadrupole (mass spectrometer) | - |

| TBDMS | Tert-Butyldimethylsilyl ether | 124150-87-4 |

| TDG | Thiodiglycol | 111-48-8 |

| TMA | Tetramethylarsonium | NF |

| TMAO | Trimethylarsine oxide | 4964-14-1 |

| UV | Ultraviolet | - |

References

- R.S. Houk, V.A. Fassel, G.D. Flesch, H.J. Svec, A.L. Gray, C.E. Taylor, Inductively Coupled Argon Plasma as an Ion Source for Mass Spectrometric Determination of Trace Elements, Anal. Chem. 952 (1980) 2283-2289. https://masspec.scripps.edu/learn/ms/pdf/1980_HoukRS.pdf.

- A.L. Gray, Mass-spectrometric Analysis of Solutions Using an Atmospheric Pressure Ion Source, Analyst 100 (1975) 1190, 289-299. [CrossRef]

- P. Vanninen (Ed.) P. Vanninen, ed., Recommended Operating Procedures for Analysis in the Verification of Chemical Disarmament, The Blue Book, University of Helsinki, Helsinki (2017) ISBN 978-951-51-9958-4.

- J. Nawała, K. Czupryński, S. Popiel, D. Dziedzic, J. Bełdowski, Development of the HS-SPME-GC-MS/MS method for analysis of chemical warfare agent and their degradation products in environmental samples, Anal. Chim. Acta 933 (2016) 103–116. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Valdez, R.N. Leif, S. Hok, B.R. Hart, Analysis of chemical warfare agents by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry: Methods for their direct detection and derivatization approaches for the analysis of their degradation products, Rev. Anal. Chem. 37 (2018) 1, 20170007. [CrossRef]

- T. Wada, E. Nagasawa, S. Hanaoka, Simultaneous determination of degradation products related to chemical warfare agents by high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry, Appl. Organomet. Chem. 20 (2006) 9, 573–579. [CrossRef]

- B. Muir, B.J. Slater, D.B. Cooper, C.M. Timperley, Analysis of chemical warfare agents: I. Use of aliphatic thiols in the trace level determination of Lewisite compounds in complex matrices, J. Chromatogr. A 1028 (2004) 2, 313–320. [CrossRef]

- S. Popiel, M. Sankowska, Determination of chemical warfare agents and related compounds in environmental samples by solid-phase microextraction with gas chromatography, J. Chromatogr. A 1218 (2011) 47, 8457–8479. [CrossRef]

- Terzic, I. Swahn, G. Cretu, M. Palit, G. Mallard, Gas chromatography-full scan mass spectrometry determination of traces of chemical warfare agents and their impurities in air samples by inlet based thermal desorption of sorbent tubes, J. Chromatogr. A 1225 (2012) 182–192. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Tørnes, A.M. Opstad, B.A. Johnsen, Determination of organoarsenic warfare agents in sediment samples from Skagerrak by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, Sci. Total Environ. |356 (2006) 1-3, 235–246. [CrossRef]

- M.Y. Cheh, H.C. M.Y. Cheh, H.C. Chua, F.B. Hopkins, J.R. Riches, C.M. Timperley, H.S.N. Lee, Determination of lewisite constituents in aqueous samples using hollow-fibre liquid-phase microextraction followed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 406 (2014) 21, 5103–5110. [CrossRef]

- T. Capoun, J. Krykorkova, Internal Standards for Quantitative Analysis of Chemical Warfare Agents by the GC/MS Method: Nerve Agents, J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Wilbur, Applications of ICP-MS in Homeland Security, Agilent Technologies (2004) https://www.agilent.com/Library/applications/5989-0741EN.pdf.

- STANAG 4701(1), NATO Standard AEP-66, NATO Handbook for Sampling and Identification of Biological, Chemical and Radiological Agents (SIBCRA), Edition A Version 1, NATO Standardization Agency (2015) http://nso.nato.int/nso/.

- M.-M. Blum, R.V.S.M. Mamidanna, Analytical chemistry and the Chemical Weapons Convention, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 406 (2014) 5067–5069. [CrossRef]

- S. Mukherjee, R.D. S. Mukherjee, R.D. Gupta, Organophosphorus Nerve Agents: Types, Toxicity, and Treatments, J. Toxicol. 2020 (2020) 1–16, 3007984. [CrossRef]

- M.A. DeLuca, P.R. M.A. DeLuca, P.R. Chai, E. Goralnick, T.B. Erickson, Five Decades of Global Chemical Terror Attacks: Data Analysis to Inform Training and Preparedness, Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 15 (2021) 6, 750–761. [CrossRef]

- P.R. Chai, B.D. Hayes, T.B. Erickson, E.W. Boyer, Novichok agents: a historical, current, and toxicological perspective, Toxicol. Commun. 2 (2018) 1, 45–48. [CrossRef]

- D.D. Palkki, L. D.D. Palkki, L. Rubin, Saddam Hussein’s role in the gassing of Halabja, The Nonproliferation Review 28 (2021) 115–129. [CrossRef]

- J.R. Hiltermann, A Poisonous Affair: America, Iraq, and the Gassing of Halabja, Cambridge University Press (2014) ISBN: 9780521876865, 0521876869.

- Sarin attacks in Japan: acute and delayed health effects in survivors, Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents (Third Edition), R. C. Gupta, Academic Press, Elsevier (2020) 37–53, ISBN 9780128190906. [CrossRef]

- T. Okumura, T. Nomura, T. Suzuki, M. Sugita, Y. Takeuchi, T. Naito, S. Okumura, H. Maekawa, N. Takasu, K. Miura, K. Suzuki, The Dark Morning: The Experiences and Lessons Learned from the Tokyo Subway Sarin Attack, Chemical Warfare Agents, John Wiley & Sons (2007) 277–285, ISBN: 9780470013595. [CrossRef]

- OPCW, Note by the Technical Secretariat: Report of the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission in Syria Regarding Alleged Incidents in Ltamenah, the Syrian Arab Republic on 24 and 25 March 2018 (S/1636/2018), 2018. https://www.opcw.org/sites/default/files/documents/S_series/2018/en/s-1636-2018_e_.pdf (accessed June 6, 2024). 25 March.

- A.T. Tu, The use of VX as a terrorist agent: action by Aum Shinrikyo of Japan and the death of Kim Jong-Nam in Malaysia: four case studies, Global Security: Health, Science and Policy 5 (2020) 1, 48–56. [CrossRef]

- T. Nakagawa, A.T. Tu, Murders with VX: Aum Shinrikyo in Japan and the assassination of Kim Jong-Nam in Malaysia, Forensic Toxicol. 36 (2018) 542–544. [CrossRef]

- D. Butler, Attacks in UK and Syria highlight growing need for chemical-forensics expertise, Nature 556 (2018) 7701, 285–286. [CrossRef]

- H.K. Kim, State Terrorism as a Mechanism for Acts of Violence against Individuals: Case Studies of Kim Jong-Nam, Skripal and Khashoggi Assassinations, Journal of East Asia and International Law (JEAIL) 14 (2021) 55–78. [CrossRef]

- V. Aroniadou-Anderjaska, J.P. V. Aroniadou-Anderjaska, J.P. Apland, T.H. Figueiredo, M. De Araujo Furtado, M.F. Braga, Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (nerve agents) as weapons of mass destruction: History, mechanisms of action, and medical countermeasures, Neuropharmacology 181 (2020) 108298. [CrossRef]

- R.M. Black, B. Muir, Derivatisation reactions in the chromatographic analysis of chemical warfare agents and their degradation products, J. Chromatogr. A 1000 (2003) 1-2, 253–281. [CrossRef]

- I.S. Che Sulaiman, B.W. I.S. Che Sulaiman, B.W. Chieng, F.E. Pojol, K.K. Ong, J.I. Abdul Rashid, W.M.Z. Wan Yunus, N.A. Mohd Kasim, N. Abdul Halim, S.A. Mohd Noor, V.F. Knight, A review on analysis methods for nerve agent hydrolysis products, Forensic Toxicol. 38 (2020) 297–313. [CrossRef]

- D.D. Richardson, J.A. D.D. Richardson, J.A. Caruso, Derivatization of organophosphorus nerve agent degradation products for gas chromatography with ICPMS and TOF-MS detection, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 388 (2007) 4, 809–823. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Valdez, R.N. Leif, Analysis of Organophosphorus-Based Nerve Agent Degradation Products by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Current Derivatization Reactions in the Analytical Chemist’s Toolbox, Molecules 26 (2021) 4631. [CrossRef]

- D.D. Richardson, B.B.M. D.D. Richardson, B.B.M. Sadi, J.A. Caruso, Reversed phase ion-pairing HPLC-ICP-MS for analysis of organophosphorus chemical warfare agent degradation products, J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 21 (2006) 396–403. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Kubachka, D.D. K.M. Kubachka, D.D. Richardson, D.T. Heitkemper, J.A. Caruso, Detection of chemical warfare agent degradation products in foods using liquid chromatography coupled to inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry, J. Chromatogr. A 1202 (2008) 2, 124–131. [CrossRef]

- E. Carletti, L. Jacquamet, M. Loiodice, D. Rochu, P. Masson, F. Nachon, Update on biochemical properties of recombinant Pseudomonas diminuta phosphotriesterase., J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.24 (2009) 4, 1045–1055. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Duchovic, J.A. R.J. Duchovic, J.A. Vilensky, Mustard Gas: Its Pre-World War I History, J. Chem. Educ. 84 (2007) 6, 944. [CrossRef]

- UN. Secretary-General, Report of the Mission Dispatched by the Secretary-General to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Conflict between the Islamic Republic of Iran and Iraq, S/20060, New York (1988). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/48547/files/S_20060-EN.

- M.H. Rabiee, M. Ghanei, H. Amini, A. Akhlaghi, Mortality rate of people exposed to Mustard Gas during Iran-Iraq war in Sardasht, Iran: a 32 years retrospective cohort study, BMC Public Health 22 (2022) 1152. [CrossRef]

- H. Abolghasemi, M.H. H. Abolghasemi, M.H. Radfar, M. Rambod, P. Salehi, H. Ghofrani, M.R. Soroush, F. Falahaty, Y. Tavakolifar, A. Sadaghianifar, S.M. Khademolhosseini, Z. Kavehmanesh, M. Joffres, F.M. Burkle, E.J. Mills, Childhood physical abnormalities following paternal exposure to sulfur mustard gas in Iran: a case-control study, Confl. Health. 4 (2010) 13. [CrossRef]

- T. Knobloch, J. Bełdowski, C. Böttcher, M. Söderström, N.P. Rühl, J. Sternheim, Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission Chemical Munitions Dumped in the Baltic Sea Report of the ad hoc Expert Group to Update and Review the Existing Information on Dumped Chemical Munitions in the Baltic Sea (HELCOM MUNI), Balt. Sea Environ. Proc., Helsinki (2013) ISSN 0357-2994. https://helcom.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Chemical-Munitions-Dumped-in-the-Baltic-Sea-Report-of-the-ad-hoc-Expert-Group.pdf (access: 10. June 2024.).

- T. Missiaen, M. Söderström, I. Popescu, P. Vanninen, Evaluation of a chemical munition dumpsite in the Baltic Sea based on geophysical and chemical investigations, Sci. Total Environ.408 (2010) 17, 3536–3553. [CrossRef]

- J. Bełdowski, Z. Klusek, M. Szubska, R. Turja, A.I. Bulczak, D. Rak, M. Brenner, T. Lang, L. Kotwicki, K. Grzelak, J. Jakacki, N. Fricke, A. Östin, U. Olsson, J. Fabisiak, G. Garnaga, J.R. Nyholm, P. Majewski, K. Broeg, M. Söderström, P. Vanninen, S. Popiel, J. Nawała, K. Lehtonen, R. Berglind, B. Schmidt, Chemical Munitions Search & Assessment-An evaluation of the dumped munitions problem in the Baltic Sea, Deep Sea Res., Part II 128 (2016) 85–95. [CrossRef]

- N. Schlager, J. Weisblatt, D.E. Newton, Chemical Compounds, Thomson Gale, ISBN 1 4144 0467 0 (2006). https://rushim.ru/books/spravochniki/chemical-compounds.pdf (access: 10. June 2024.).

- S.L. Hoenig, Compendium of Chemical Warfare Agents, Springer Science & Business Media, LLC (2007), ISBN: 978-0-387-34626-7. [CrossRef]

- B.T. Røen, Trace determination of sulphur mustard and related compounds in environmental samples by headspace-trap GC-MS, Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI), FFI-rapport 2008/02247 (2008) ISBN 978-82-464-1469-0. https://ffi-publikasjoner.archive.knowledgearc.net/bitstream/handle/20.500.12242/2250/08-02247.pdf (access: 10. June 2024.).

- N.B. Munro, S.S. N.B. Munro, S.S. Talmage, G.D. Griffin, L.C. Waters, A.P. Watson, J.F. King, V. Hauschild, The Sources, Fate, and Toxicity of Chemical Warfare Agent Degradation Products, Environ. Health Perspect. 107 (1999) 12, 933–974. [CrossRef]

- R.M. Black, R.J. Clarke, D.B. Cooper, R.W. Read, D. Utley, Application of headspace analysis, solvent extraction, thermal desorption and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to the analysis of chemical warfare samples containing sulphur mustard and related compounds, J. Chromatogr. A 637 (1993) 1, 71–80. [CrossRef]

- A.E. Boyer, D. Ash, D.B. Barr, C.L. Young, W.J. Driskell, R.D. Whitehead, M. Ospina, K.E. Preston, A.R. Woolfitt, R.A. Martinez, L.A. Silks, J.R. Barr, Quantitation of the sulfur mustard metabolites 1,1′-sulfonylbis[2-(methylthio)ethane] and thiodiglycol in urine using isotope-dilution gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, J. Anal. Toxicol. 28 (2004) 5, 327–332. [CrossRef]

- J. Riches, R.W. J. Riches, R.W. Read, R.M. Black, Analysis of the sulphur mustard metabolites thiodiglycol and thiodiglycol sulphoxide in urine using isotope-dilution gas chromatography-ion trap tandem mass spectrometry, J. Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 845 (2007) 1, 114–120. [CrossRef]

- S. Popiel, J. Nawała, D. Dziedzic, M. Söderström, P. Vanninen, Determination of mustard gas hydrolysis products thiodiglycol and thiodiglycol sulfoxide by gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry after trifluoroacetylation, Anal. Chem. 86 (2014) 12, 5865–5872. [CrossRef]

- K.K. Kroening, D.D. Richardson, S. Afton, J.A. Caruso, Screening hydrolysis products of sulfur mustard agents by high-performance liquid chromatography with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry detection, Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 393 (2009) 8, 1949–1956. [CrossRef]

- G. Garnaga, E. Wyse, S. Azemard, A. Stankevičius, S. de Mora, Arsenic in sediments from the southeastern Baltic Sea, Environ. Pollut. 144 (2006) 3, 855–861. [CrossRef]

- M. Kuligowska, S. Neffe, Collection and identification of samples contaminated with chemical warfare agents and their degradation products with the use of military equipment for detecting chemical contamination at the site of their occurrence, Bulletin of MUT 71 (2022) 4, 73–110. [CrossRef]

- T. Bausinger, J. Preuß, Environmental remnants of the first World War: Soil contamination of a burning ground for arsenical ammunition, Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 74 (2005) 6, 1045–1052. [CrossRef]

- M. Hempel, B. Daus, C. Vogt, H. Weiss, Natural attenuation potential of phenylarsenicals in anoxic groundwaters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 18, 6989–6995. [CrossRef]

- M. Ishizaki, T. Yanaoka, M. Nakamura, T. Hakuta, S. Ueno, M. Komuro, M. Shibata, T. Kitamura, A. Honda, M. Doy, K. Ishii, A. Tamaoka, N. Shimojo, T. Ogata, E. Nagasawa, S. Hanaoka, Detection of Bis(diphenyl wrsine)oxide, Diphenylarsinic Acid and Phenylarsonic Acid, Compounds Probably Derived from Chemical Warfare Agents, in Drinking Well Water, J. Health Sci. 52 (2005) 2, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- K. Kinoshita, Y. K. Kinoshita, Y. Shida, C. Sakuma, M. Ishizaki, K. Kiso, O. Shikino, H. Ito, M. Morita, T. Ochi, T. Kaise, Determination of diphenylarsinic acid and phenylarsonic acid, the degradation products of organoarsenic chemical warfare agents, in well water by HPLC-ICP-MS, Appl. Organomet. Chem. 19 (2005) 2, 287–293. [CrossRef]

- J. Nawała, D. Gordon, D. Dziedzic, P. Rodziewicz, S. Popiel, Why does Clark I remain in the marine environment for a long time?, Sci. Total Environ. 774 (2021) 145675. [CrossRef]

- T. Brzeziński, M. Czub, J. Nawała, D. Gordon, D. Dziedzic, B. Dawidziuk, S. Popiel, P. Maszczyk, The effects of chemical warfare agent Clark I on the life histories and stable isotopes composition of Daphnia magna, Environ. Pollut. 266 (2020) 115142. [CrossRef]

- K. Kinoshita, O. Shikino, Y. Seto, T. Kaise, Determination of degradation compounds derived from Lewisite by high performance liquid chromatography/inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry, Appl. Organomet. Chem. 20 (2006) 9, 591–596. [CrossRef]

- K. Kinoshita, A. Noguchi, K. Ishii, A. Tamaoka, T. Ochi, T. Kaise, Urine analysis of patients exposed to phenylarsenic compounds via accidental pollution, J. Chromatogr. B: Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 867 (2008) 2, 179–188. [CrossRef]

- B. Daus, J. Mattusch, R. Wennrich, H. Weiss, Analytical investigations of phenyl arsenicals in groundwater, Talanta 75 (2008) 2, 376–379. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Stetson, M.L. Erickson, J. Brenner, E.C. Berquist, C. Kanagy, S. Whitcomb, C. Lawrence, Stability of inorganic and methylated arsenic species in laboratory standards, surface water and groundwater under three different preservation regimes, J. Appl. Geochem. 125 (2021) 104814, 13. [CrossRef]

- S. Hisatomi, L. Guan, M. Nakajima, K. Fujii, M. Nonaka, N. Harada, Formation of diphenylthioarsinic acid from diphenylarsinic acid under anaerobic sulfate-reducing soil conditions, J. Hazard. Mater. 262 (2013) 25–30. [CrossRef]

- K.T. Suzuki, B.K. Mandal, A. Katagiri, Y. Sakuma, A. Kawakami, Y. Ogra, K. Yamaguchi, Y. Sei, K. Yamanaka, K. Anzai, M. Ohmichi, H. Takayama, N. Aimi, Dimethylthioarsenicals as arsenic metabolites and their chemical preparations, Chem. Res. Toxicol. 17 (2004) 7, 914–921. [CrossRef]

- OPCW, Chemical Weapon Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction, Geneva (1992). https://www.opcw.org/sites/default/files/documents/CWC/CWC_en.pdf (access: 10. June 2024.).

- T.M. Baygildiev, I.A. Rodin, A.N. Stavrianidi, A. v. Braun, D.I. Akhmerova, O.A. Shpigun, I. v. Rybalchenko, Time-efficient LC/MS/MS determination of low concentrations of methylphosphonic acid, Inorg. Mater. 53 (2017) 1382–1385. [CrossRef]

- J.Y. Lee, Y.H. Lee, Rapid screening and determination of nerve agent metabolites in human urine by LC-MS/MS, J. Anal. Chem. 69 (2014) 909–916. [CrossRef]

- T. Baygildiev, M. Vokuev, A. Braun, I. Rybalchenko, I. Rodin, Monitoring of hydrolysis products of mustard gas, some sesqui- and oxy-mustards and other chemical warfare agents in a plant material by HPLC-MS/MS, J. Chromatogr. B: Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1162 (2021) 122452. [CrossRef]

| Analyte. | LOD for HPLC-ICP-MS [pg/mL] | LOD for GC-ICP-MS [pg/mL] |

|---|---|---|

| EMPA | 263 | 34,2 |

| IMPA | 183 | 20,9 |

| MPA | 139 | 49,6 |

| No. | Type of column | Mobile phase | Flow [mL/min] | V injection [μL] | Analytes | LOD [ng/mL] | Separation time [min] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Dionex IonPac AS7 4.1 mm × 250 mm, guard column | 0.4 mM acetic acid/sodium acetate, 5 mM HNO3 (pH ∼2.4) in DDW | 1.0 | 25 | EMPA IMPA MPA |

NA NA NA |

5 |

| 2. | Hamilton PRP-X100 4.6 mm × 100 mm 5μm | A= 0.5% H2CO2 (pH ∼2.3), 5% MeOH in DDW B = 0.3M NH4HCO2 (pH ∼2.3), 22% MeOH in DDW |

1.0 | 100 | EDHAP MPA EPA DMHP PPA EMPA IMPA DEHP IPHEP IBHMP |

21.7 18.3 19.9 10.0 22.9 20.4 19.5 26.6 61.5 81.1 |

25 |

| 3. | Hamilton PRP-X100 2.1 mm× 150 mm 5 μm | A= 10 mM (NH4)2CO3 (pH ∼8.5) in DDW B=50 mM (NH4)2CO3 (pH ∼8.5) in DDW |

0.5 | 100 | EDHAP MPA EPA DMHP PPA EMPA IMPA |

88.1 7.4 7.4 8.9 14.5 11.2 28.6 |

30 |

| STRUCTURE |  |

||||

| ACRONYM | TDG | BHETM | BHETE | BHETPr | BHETBu |

| COMPOUND NAME | Thiodiglycol | Bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)methane | 1,2-bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)ethane | 1,3-bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)propane | 1,4-bis(2-hydroxyethylthio)butane |

| LOD [NG/ML] STUDY | 4,60 | 35,50 | 79,30 | 98,50 | 73,20 |

| LOQ [NG/ML] ENVIRONMENTAL SAMPLES | 750,00 | 690,00 | 1,00 | 1,16 | 3,30 |

| Publication[62] | Publication[61] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Hydrophobicity | Dipole-dipole interaction | Separation of functional groups | ||

| Column | C4 | CN | NH2 | C8 | |

| Organic solvents | H2O (HNO3) / C2H5OH /ACN = 80:15:5, | citrate buffer / CH3OH /ACN = 70:20:10, | phosphate buffer/ACN = 50:50 | 0.1% HCOOH–CH3CN = 80:20 | |

| pH | 1,5 | 5,5 | 2,5 | 2,0 | |

| T column [°C] | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| Flow [mL/min] | 0,3 | 0,3 | 0,1 | 0,2 | |

| V injection[μl] | 20 | 10 | no satisfactory separation, the NH2 column was not used for further research |

20 | |

| LOD [ng/mL As] | PAA | 0,25 | 1,0 | 0,3 | |

| PMAA | 0,25 | 0,5 | - | ||

| DPAA | 0,5 | DPAA + AB | 0,5 | ||

| PDMAO | 0,1 | 0,5 | - | ||

| DMPAO | 0,3 | 1,0 | - | ||

| No. | Analyte | LOD [ppb = ng/mL] | |||

| HPLC-MS/MS | Ref. | HPLC-ICP-MS | Ref. | ||

| 1. | MPA | 10 | [68] | 0.14a) | [34] |

| 2. | EMPA | 5* 1** |

[69] | 0.03 a) | [34] |

| 3. | IMPA | 5* 1** |

[69] | 0.02 a) | [34] |

| 4. | TDG | 40 | [70] | 4.6 | [52] |

| 5. | CVAOA | 500 | [6] | 0.1 | [61] |

| 6. | PAA | 50 | [6] | 0.25 | [62] |

| 7. | PMAA | 1 | [6] | 0.25 | [62] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).