Submitted:

18 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

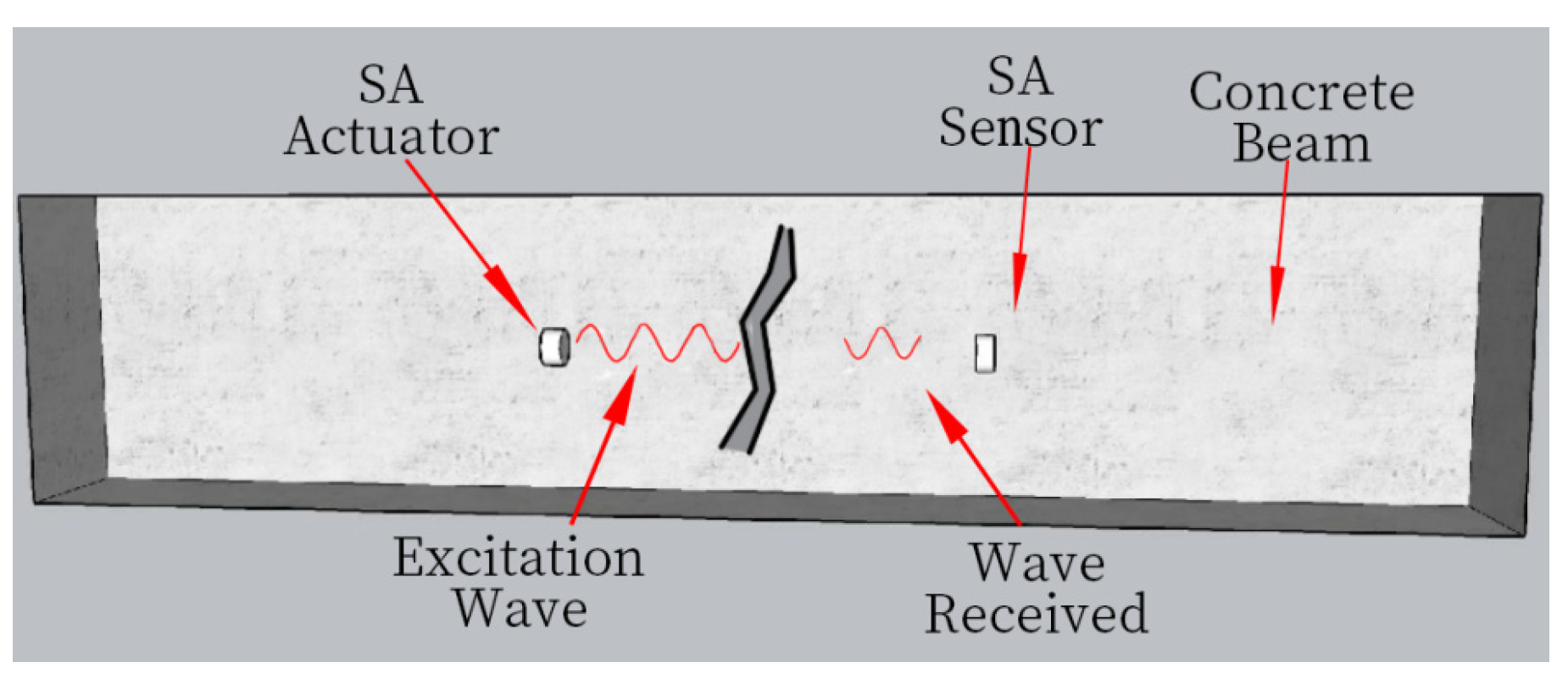

2. Piezoelectric Intelligent Aggregate Monitoring Principle

2.1. Piezoelectric Intelligent Aggregate and Active sensing Technology Loss Measurement Principle

2.2. Damage Index Based on Wavelet Packet Energy

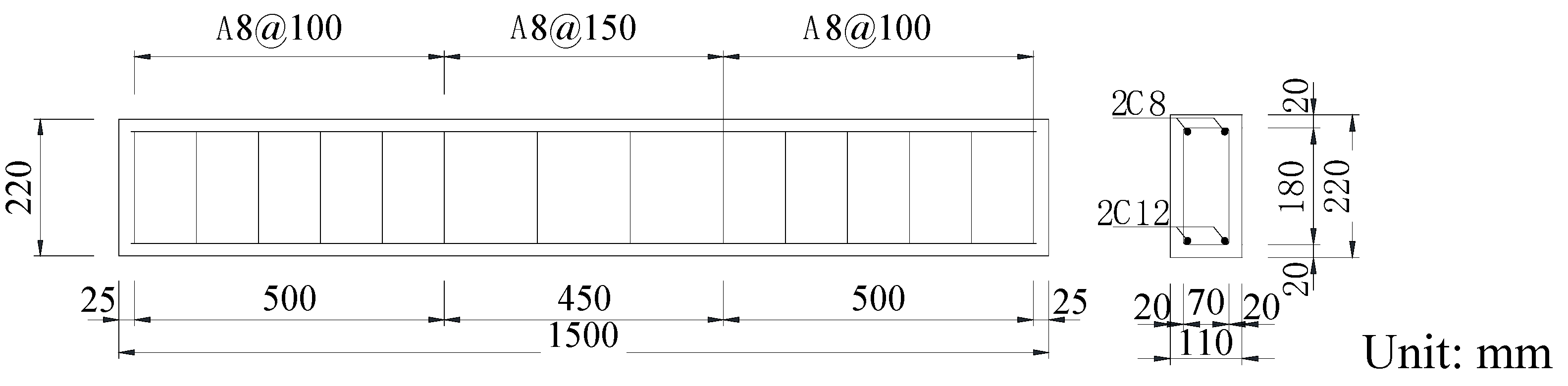

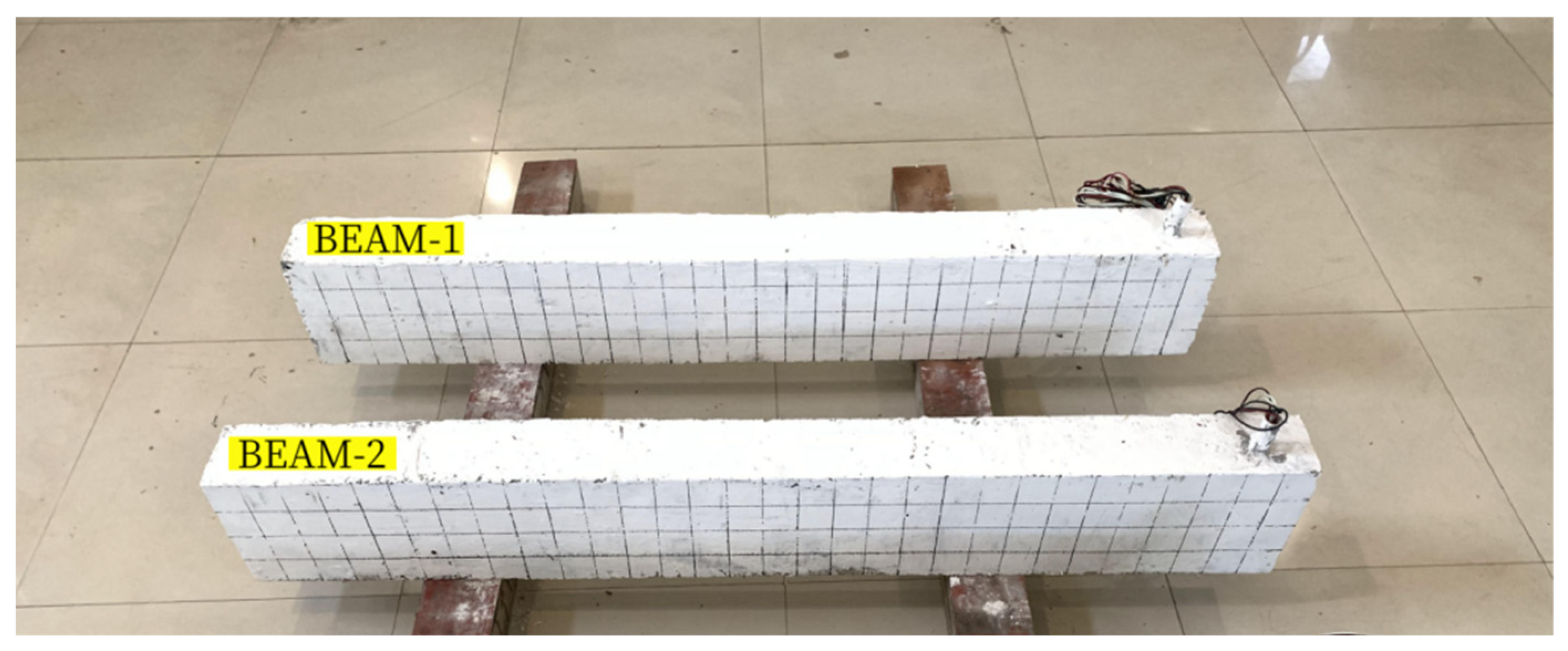

3. Fabrication of Test Components

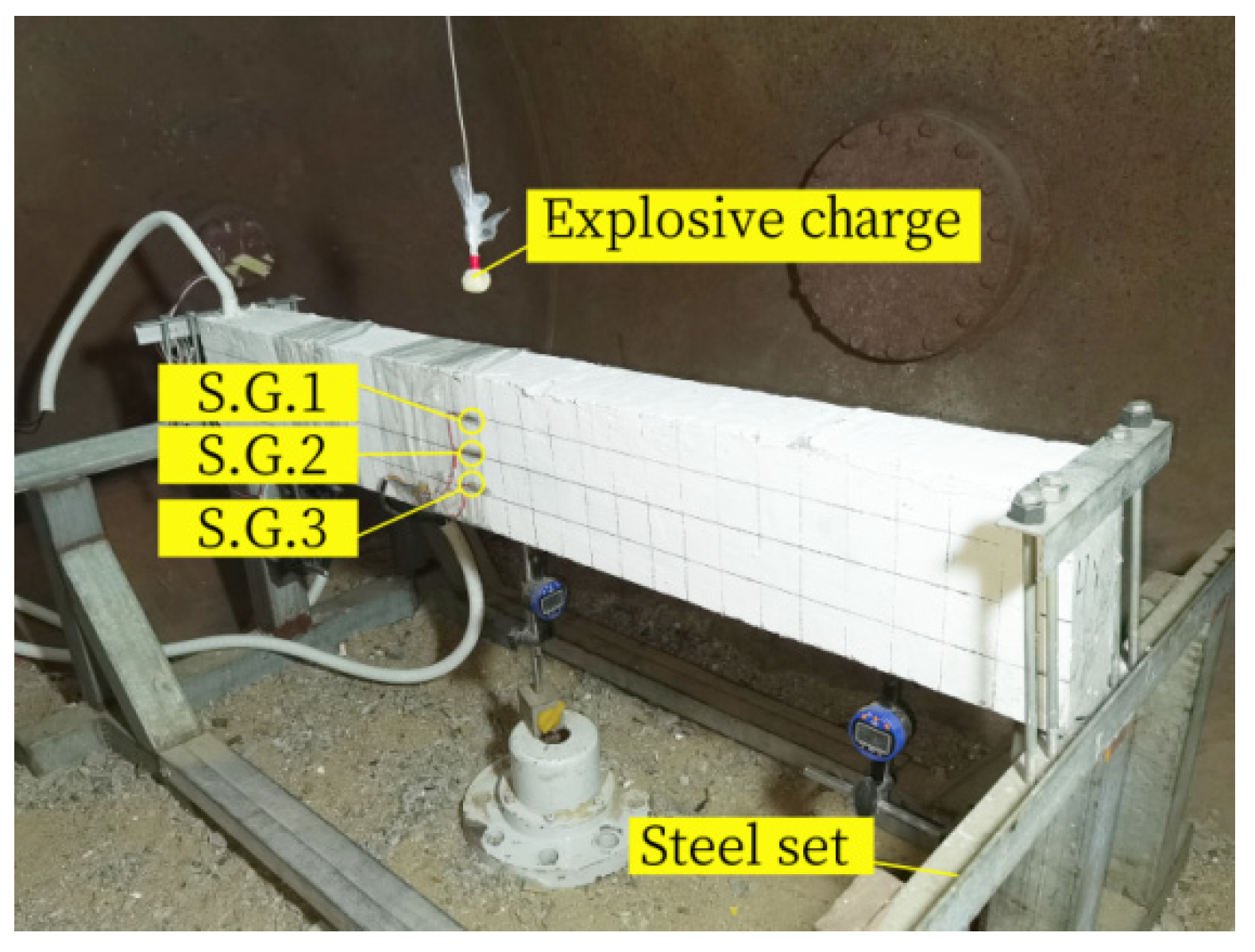

4. Test Plan

4.1. Explosion Test Is Carried Out on Beam-1 BEAM

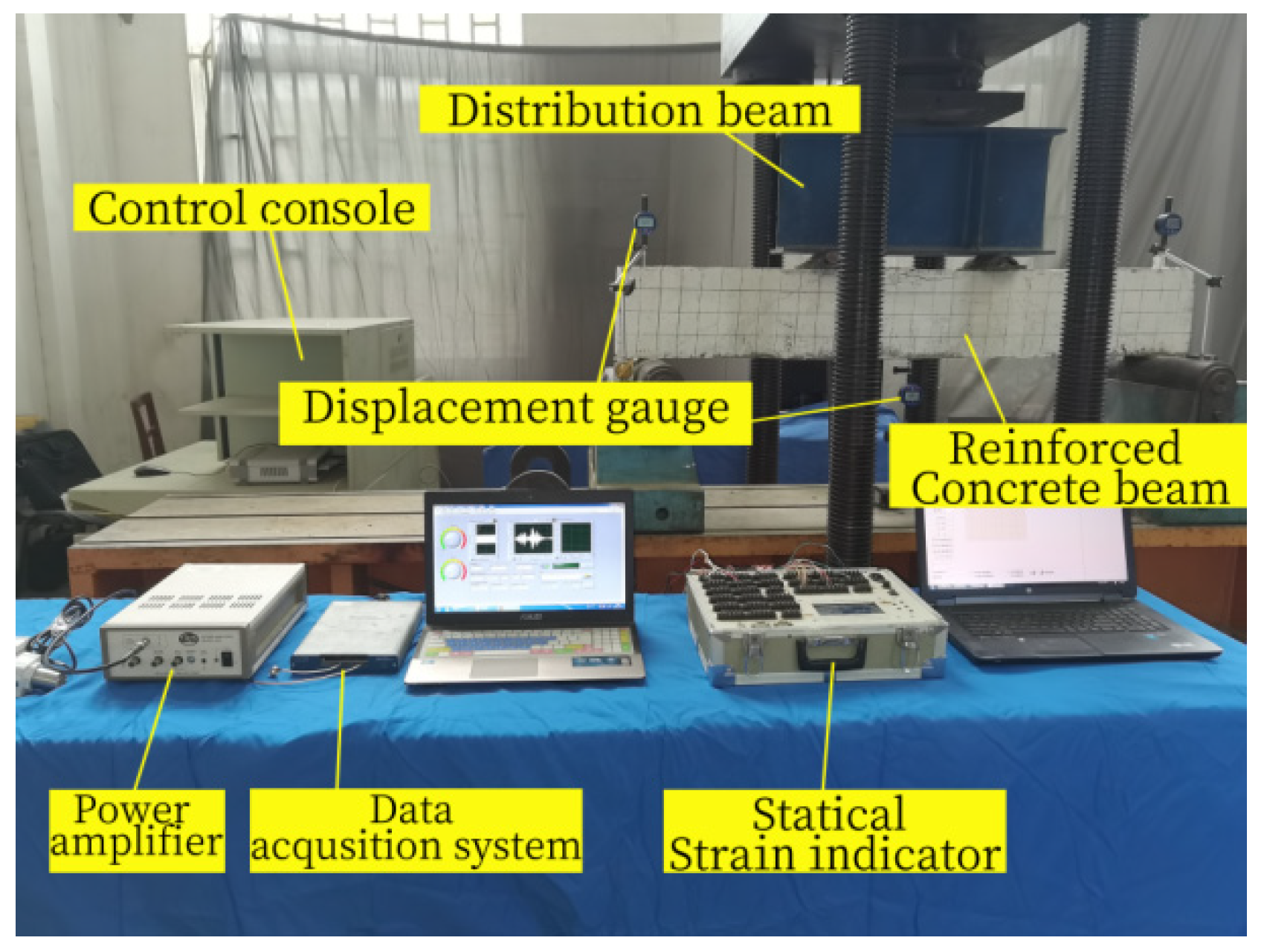

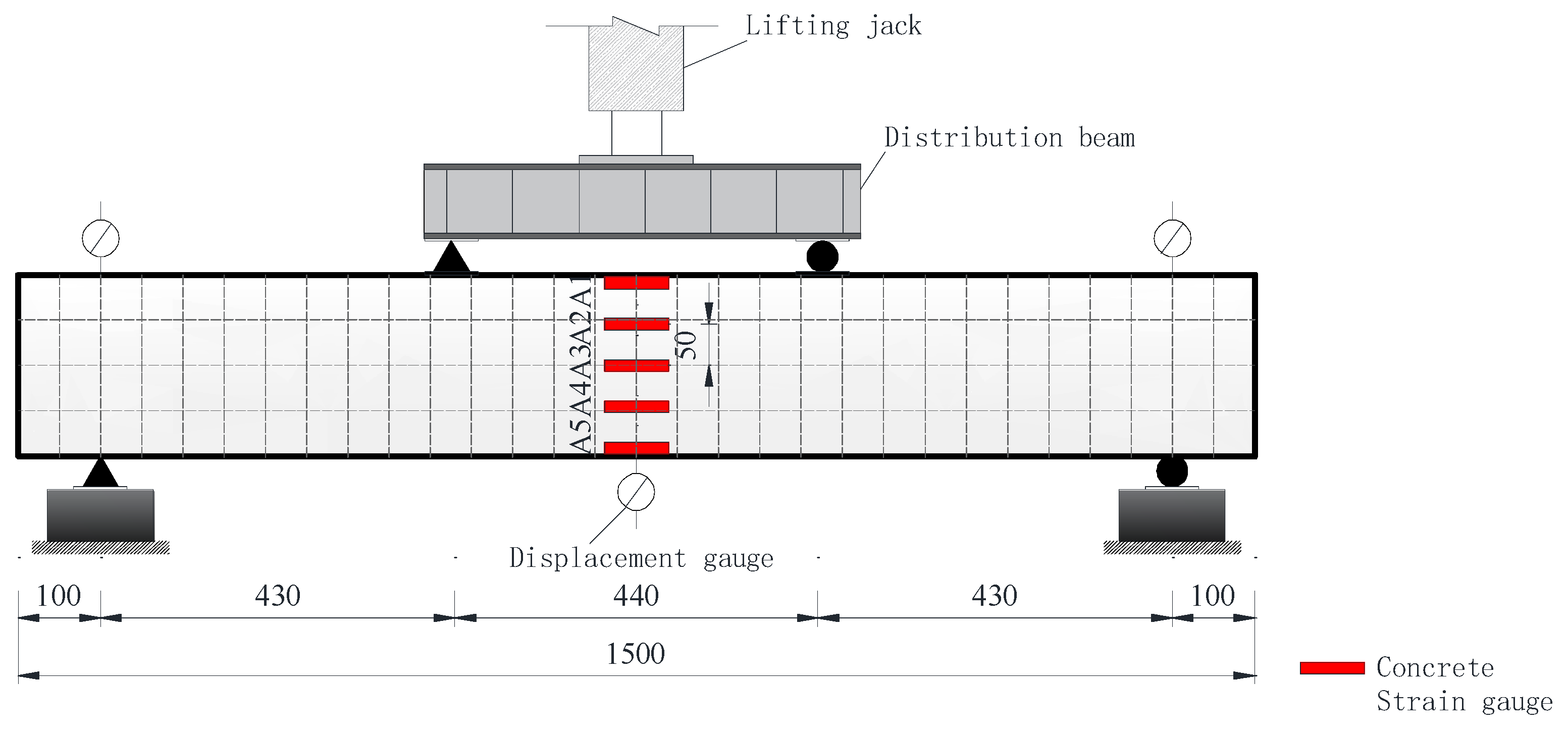

4.2. Bearing Capacity Experiment of Two RC Beams

5. Test Results and Analysis

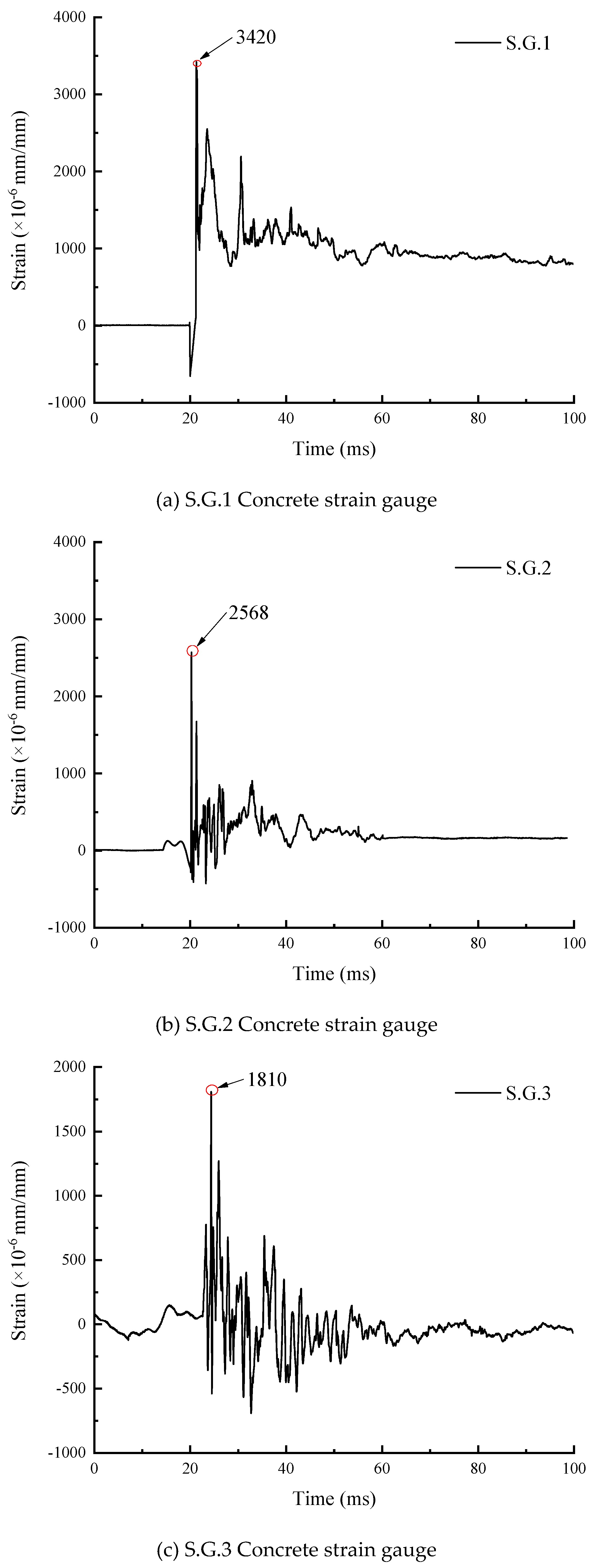

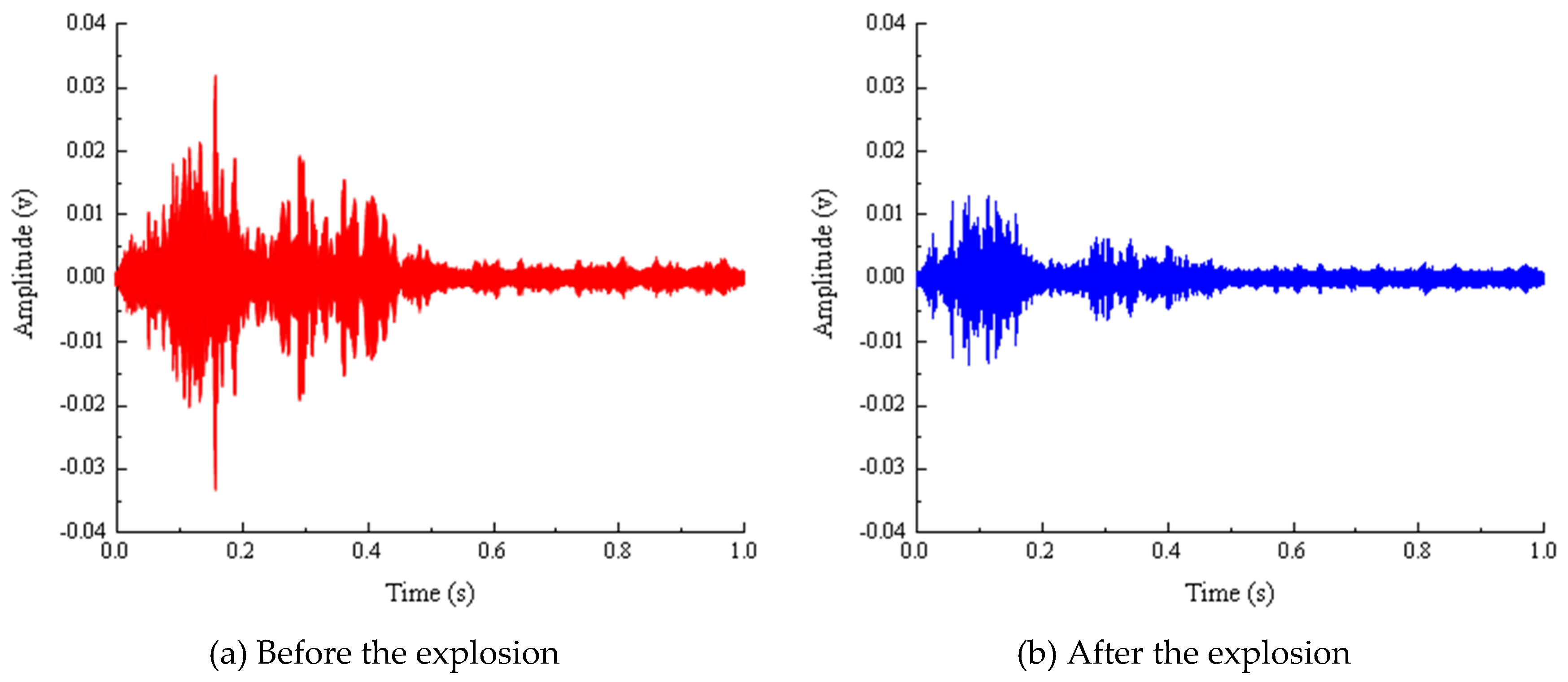

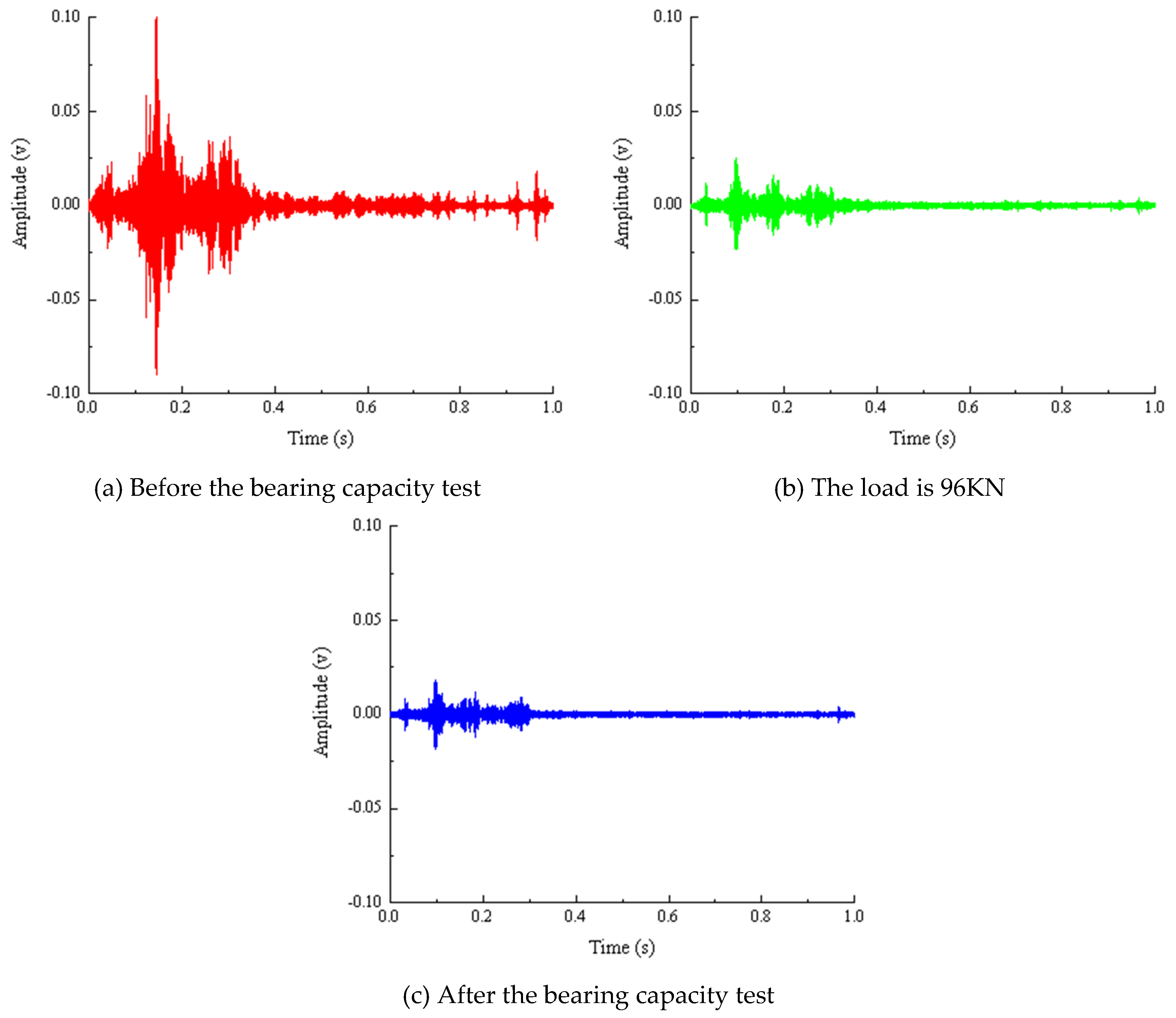

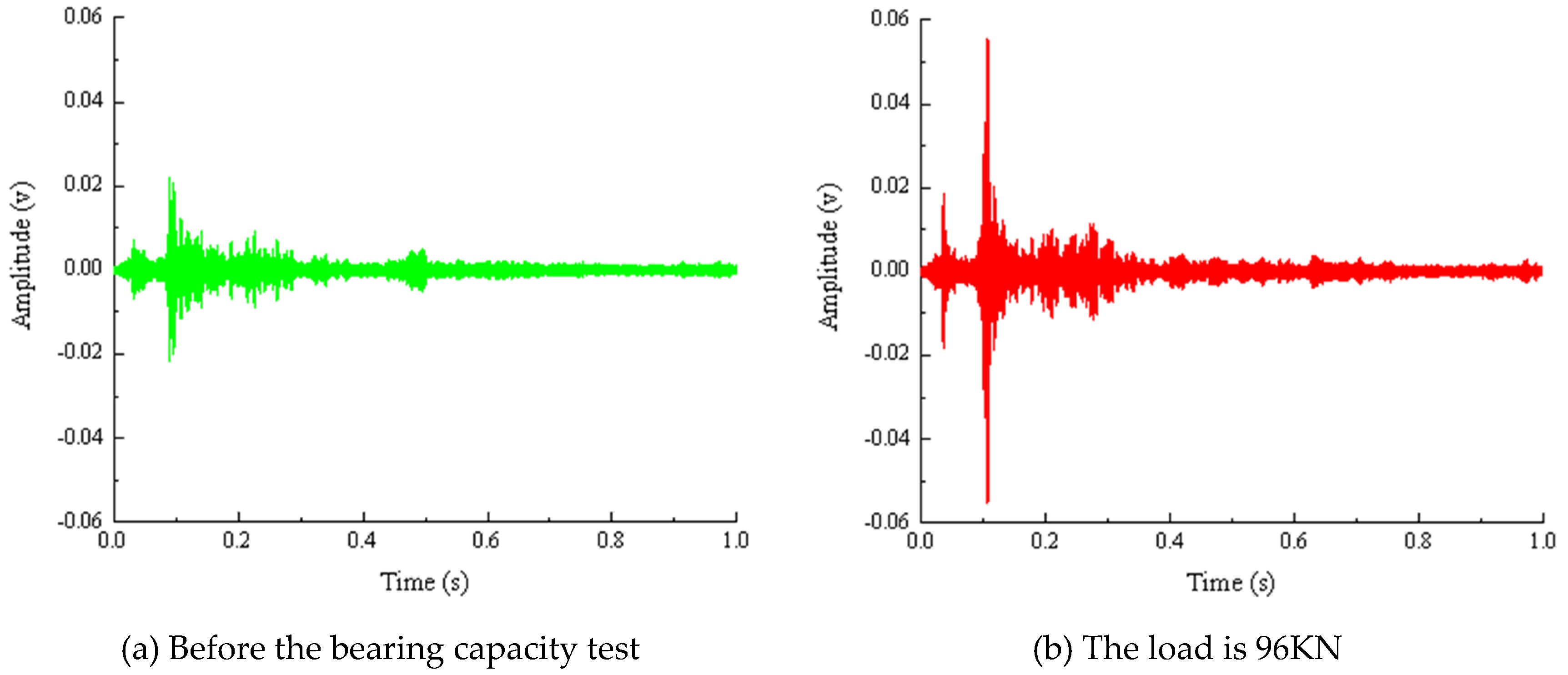

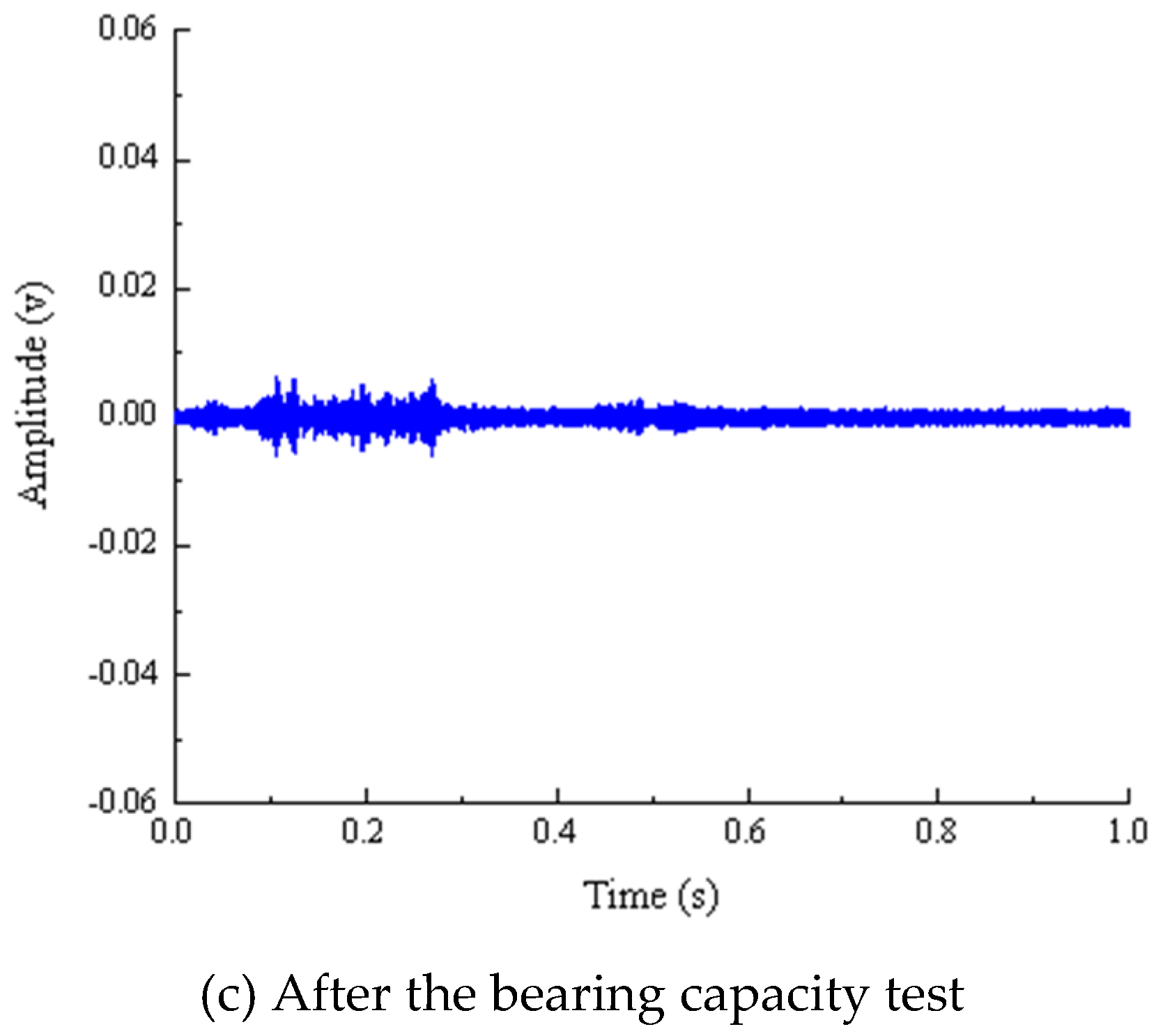

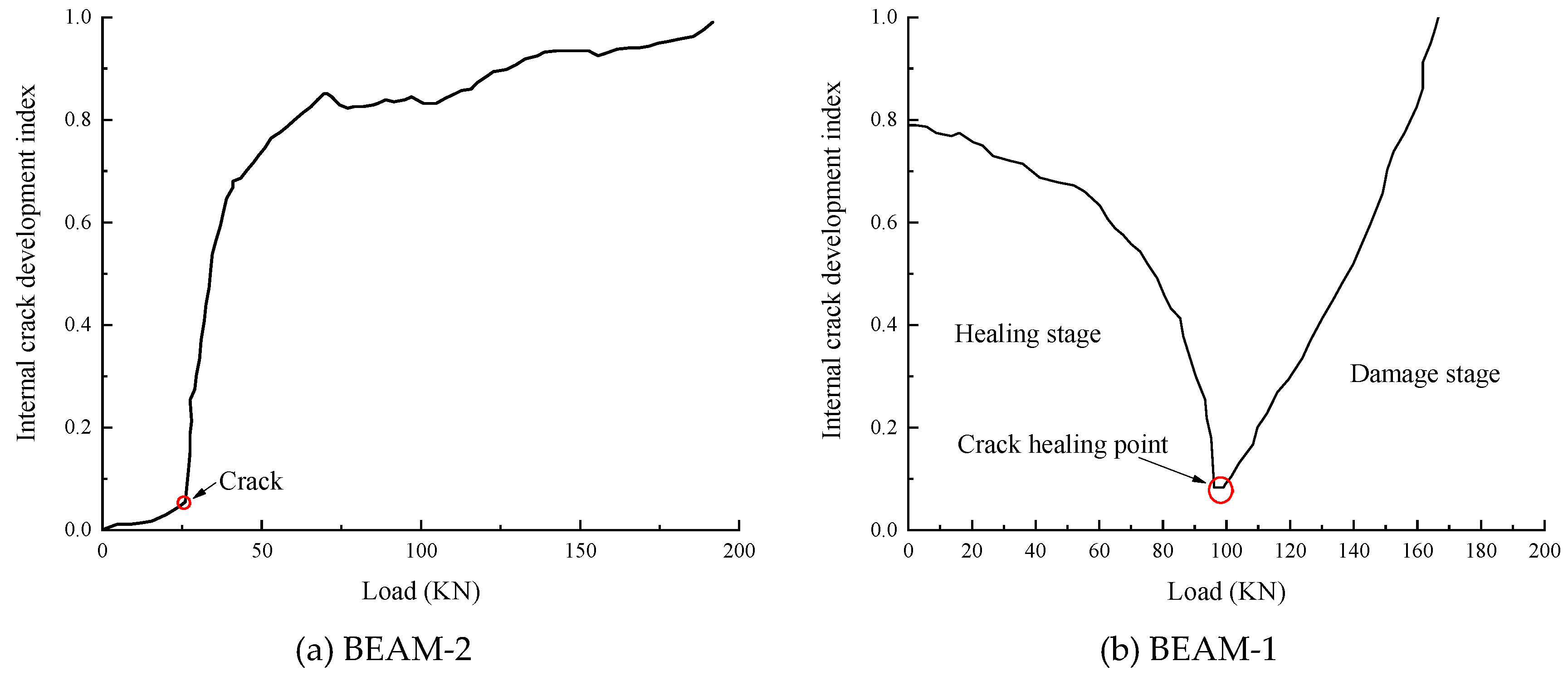

5.1. Analysis of Explosion Damage Results of Beam-1 BEAM

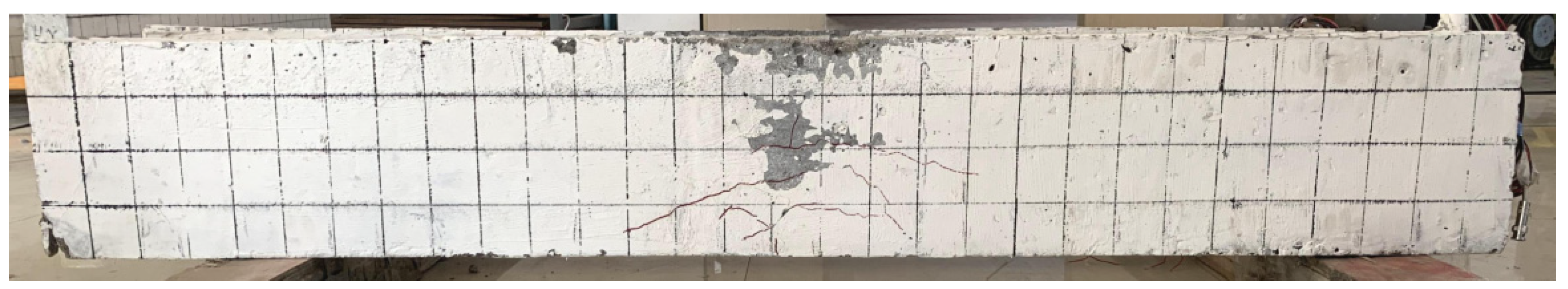

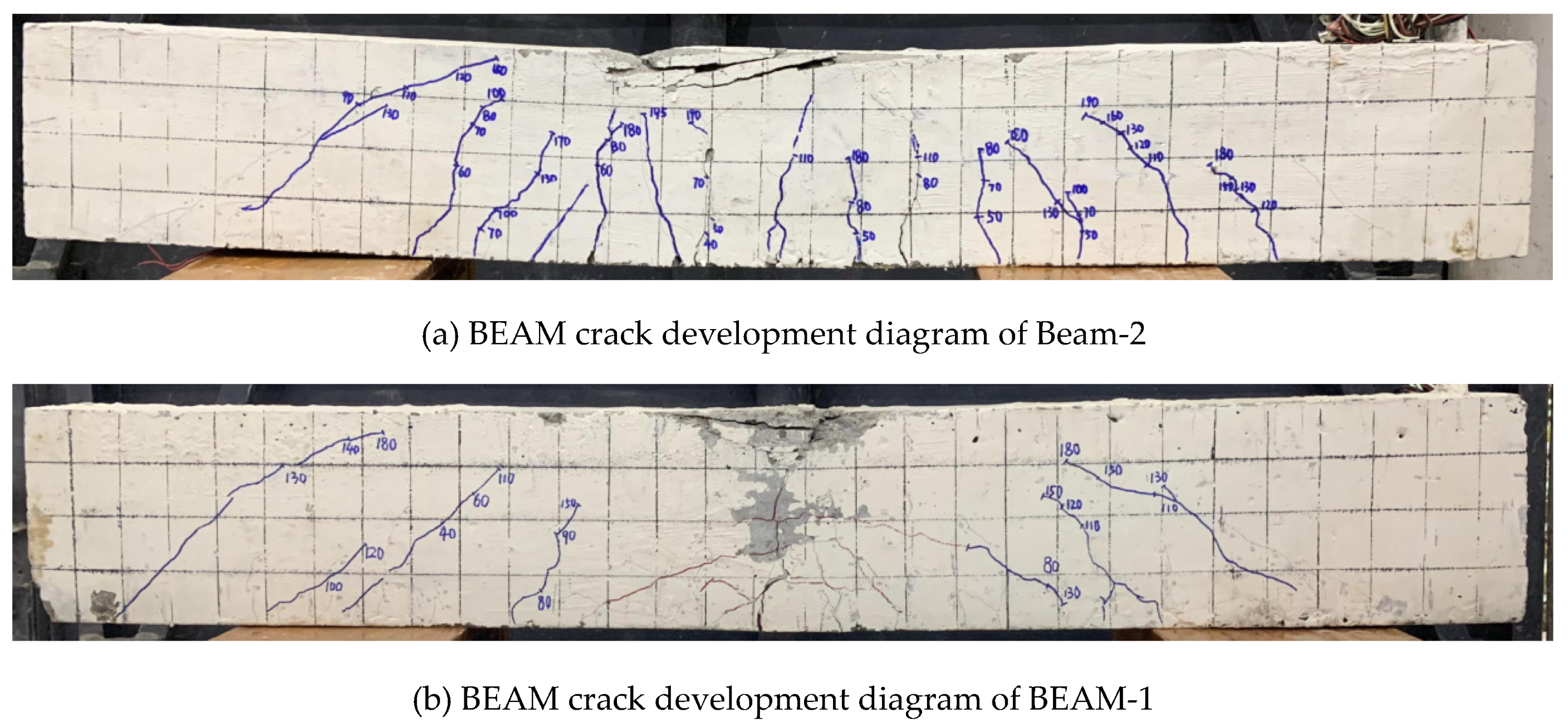

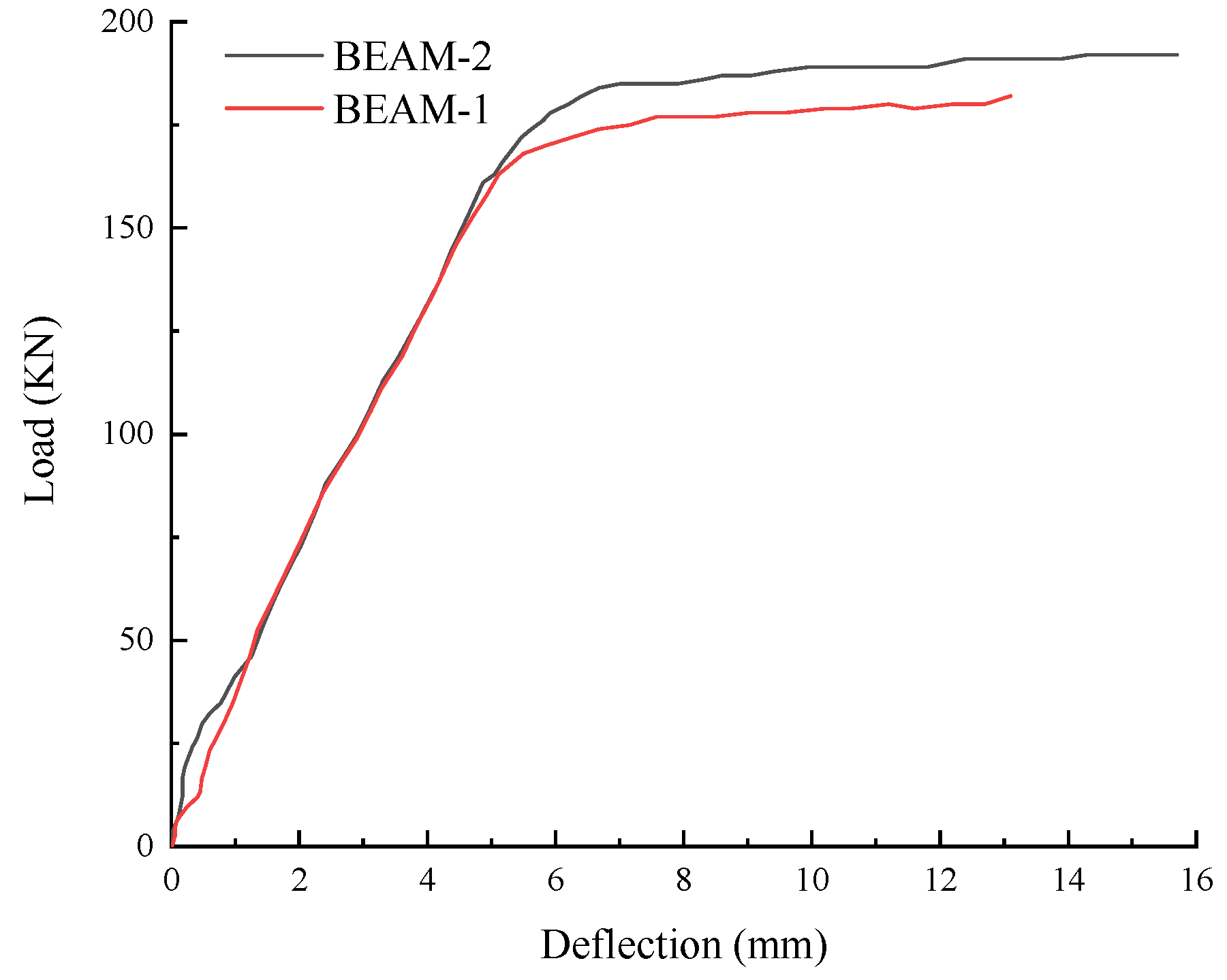

5.2. Analysis of Bearing Capacity Test Results of Two Beams

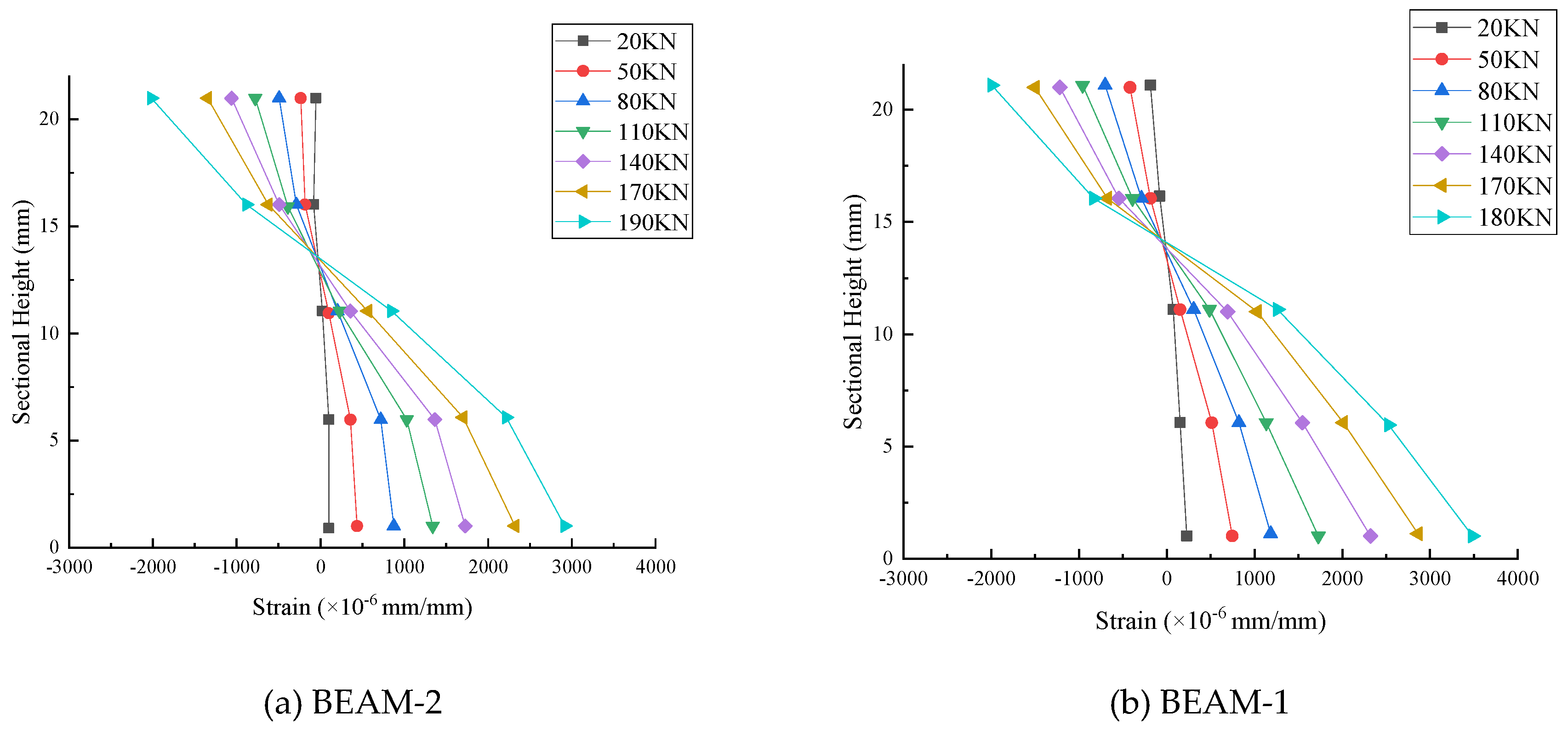

5.3. Analysis of Flexural Capacity

6. Conclusions

References

- Zhong, J.; Song, C.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, F. Experimental and numerical simulation study on failure mode transformation law of reinforced concrete beam under impact load. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, G.; Stochino, F. Theoretical models to predict the flexural failure of reinforced concrete beams under blast loads. Eng. Struct. 2012, 49, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Experimental and numerical research on reinforced concrete slabs strengthened with POZD coated corrugated steel under contact explosive load. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2022, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifehzadeh, M.; Aryan, H.; Gencturk, B.; Akyniyazov, D. Structural Response of Steel Jacket-UHPC Retrofitted Reinforced Concrete Columns under Blast Loading. Materials 2021, 14, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, J.; Kong, X.; Chen, Y.; Jin, F. Wrapping and anchoring effects on CFRP strengthened reinforced concrete arches subjected to blast loads. Struct. Concr. 2020, 22, 1913–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ke, Z.; Feng, W.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Li, H. Effects of crumb rubber particles on the dynamic response of reinforced concrete beams subjected to blast loads. Eng. Struct. 2024, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katchalla, B.; Jaswanth, G.; Mukesh, K.; Kasturi, B.; Hrishikesh, S. Performance-based probabilistic deflection capacity models and fragility estimation for reinforced concrete column and beam subjected to blast loading. Reliability Engineering & System Safety. 2022, 227, 108729. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Algassem, O.; Aoude, H. Response of high-strength reinforced concrete beams under shock-tube induced blast loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 189, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Aoude, H. Effects of stainless steel reinforcement and fibers on the flexural behaviour of high-strength concrete beams subjected to static and blast loading. Eng. Struct. 2023, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, F.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Bai, F.; Yu, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, J. Effect of close-in successive explosions on the blast behaviors of reinforced concrete beams: An experimental study. Structures 2023, 53, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.-B.; Yu, W.-L.; Huang, F.-L. Experimental investigation of p-section concrete beams under contact explosion and close-in explosion conditions. Def. Technol. 2018, 14, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, J.-B.; Huang, F.-L. Behavior of reinforced concrete beams and columns subjected to blast loading. Def. Technol. 2018, 14, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zheng, S.; Lei, C.; Jia, H.; Chen, Z.; Yu, B. Machine learning-based prediction for residual bearing capacity and failure modes of rectangular corroded RC columns. Ocean Eng. 2023, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xie, H.; Han, B.; Li, P.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, J. Experimental study on residual bearing capacity of full-size fire-damaged prestressed concrete girders. Structures 2022, 45, 1788–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-P.; Jiang, Y.; Li, W.-B. Residual load-bearing capacity of corroded reinforced concrete columns with an annular cross-section. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Chen, X.; Yang, B.; Guo, J.; Liu, Y. Finite element analysis on the residual bearing capacity of axially preloaded tubular T-joints subjected to impacts. Structures 2021, 31, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wu, C. Experimental study on residual axial bearing capacity of UHPFRC-filled steel tubes after lateral impact loading. Structures 2020, 26, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molkens, T.; Van Coile, R.; Gernay, T. Assessment of damage and residual load bearing capacity of a concrete slab after fire: Applied reliability-based methodology. Eng. Struct. 2017, 150, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.; Muhammad, M.A.; Mohammed, B.K. Effect of PET waste fiber addition on flexural behavior of concrete beams reinforced with GFRP bars. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Analysis and discussion of steel pipe-encased concrete defects by ultrasonic inspection. Nondestruct. Test. 2018, 40, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, R.V. Acoustic emission characteristics of reinforced concrete beams with varying percentage of tension steel reinforcement under flexural loading. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2017, 6, 162–176. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Cho, S.; Spencer, B.; Fan, J. Concrete Crack Assessment Using Digital Image Processing and 3D Scene Reconstruction. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2016, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrias, A.; Rodriguez, G.; Casas, J.R.; Villalba, S. Application of distributed optical fiber sensors for the health monitoring of two real structures in Barcelona. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018, 14, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Jia, H.; Pan, W. Detection of concrete defects in steel tube lining by impact echo method. Nondestruct. Test. 2021, 43, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, M.S.; Maltseva, O.V.; Noskov, A.S.; Kuznetsov, A.S. Experience of using the ultrasonic low-frequency tomograph for inspection of reinforced concrete structures. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 481, 012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wulan, T.; Yao, Y.; Bian, M.; Bao, Y. Assessment of damage evolution of concrete beams strengthened with BFRP sheets with acoustic emission and unsupervised machine learning. Eng. Struct. 2024, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdera, L.; Dvořák, R.; Hoduláková, M.; Topolář, L.; Mikulášek, K.; Smutny, J.; Chobola, Z. Application of Acoustic Emission Method and Impact Echo Method to Structural Rehabilitation. Key Eng. Mater. 2018, 776, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Wang, N.; Xu, P.; Song, G. New Crack Detection Method for Bridge Inspection Using UAV Incorporating Image Processing. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, A.M.; Moaf, F.O.; Abdelgader, H.S. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Two-Stage Concrete and Conventional Concrete Using Nondestructive Tests. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, M.A.A.; Gotz, R.; de Aguiar, P.R.; Alexandre, F.A.; Fernandez, B.O.; Junior, P.O. A Low-Cost Acoustic Emission Sensor based on Piezoelectric Diaphragm. IEEE Sensors J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, S.; Li, W.; Qi, H.; Xue, X. Use of numerical methods for identifying the number of wire breaks in prestressed concrete cylinder pipe by piezoelectric sensing technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, Y. Wave propagation modeling of the PZT sensing region for structural health monitoring. Smart Mater. Struct. 2007, 16, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Q.; Hao, H.; Fan, K.Q. Detection of delamination between steel bars and concrete using embedded piezoelectric actuators/sensors. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2013, 3, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Jiang, J.; Xu, K.; Wang, N. Damage Detection of Common Timber Connections Using Piezoceramic Transducers and Active Sensing. Sensors 2019, 19, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Gu, H.; Mo, Y.-L. Smart aggregates: multi-functional sensors for concrete structures—a tutorial and a review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kong, Q.; Ho, S.C.M.; Lim, I.; Mo, Y.L.; Song, G. Feasibility study of using smart aggregates as embedded acoustic emission sensors for health monitoring of concrete structures. Smart Mater. Struct. 2016, 25, 115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Du, C.; Liu, T.; Li, W. Effects of temperature on the performance of the piezoelectric-based smart aggregates active monitoring method for concrete structures. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 035016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Kong, Q.; Peng, Z.; Wang, L.; Dai, L.; Feng, Q.; Huo, L.; Song, G. Monitoring of Corrosion-Induced Degradation in Prestressed Concrete Structure Using Embedded Piezoceramic-Based Transducers. IEEE Sensors J. 2017, 17, 5823–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Deng, Q.; Cai, L.; Ho, S.; Song, G. Damage Detection of a Concrete Column Subject to Blast Loads Using Embedded Piezoceramic Transducers. Sensors 2018, 18, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Ren, C.; Deng, Q.; Jin, Q.; Chen, X. Real-Time Monitoring of Bond Slip between GFRP Bar and Concrete Structure Using Piezoceramic Transducer-Enabled Active Sensing. Sensors 2018, 18, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Yan, S. Statistical algorithm for damage detection of concrete beams based on piezoelectric smart aggregate. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2012, 18, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, V.; Chenaghlou, M.; Gharabaghi, A.M. A combination of wavelet packet energy curvature difference and Richardson extrapolation for structural damage detection. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 101, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.S. Damage Assessment of Subway Station Columns Subjected to Blast Loadings. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Water-cement ratio(%) | Cement (kg/m3) |

Sand (kg/m3) |

Stone (kg/m3) |

Water (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C40 | 0.39 | 432 | 558 | 1242 | 168 |

| Working condition | TNT equivalent(g) | Internal crack development index (R) | Damage index (D) | Damage assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEAM-2 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| BEAM-1 | 100 | 0.79 | 0.143 | Mild injury |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).