Submitted:

17 July 2024

Posted:

18 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Determination of Cell Number, and Secretion of MMP-1 and Procollagen 1a1

2.4. Assessment of Apoptosis

2.5. ApoLive-Glo Multiplex Assay for Cell Viability and Apoptosis

2.6. Determination of Cytosolic Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species

2.7. Determination of Mitochondrial Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species

2.8. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Gene Expression Analysis (RT-qPCR)

2.9. Mitochondrial-Respiration Parameters

2.10. Cellular ATP Levels

2.11. Preparation of Whole Cell Lysates and Western Blotting

2.12. Transient Transfection and ARE/Nrf2 Reporter Gene Assay

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

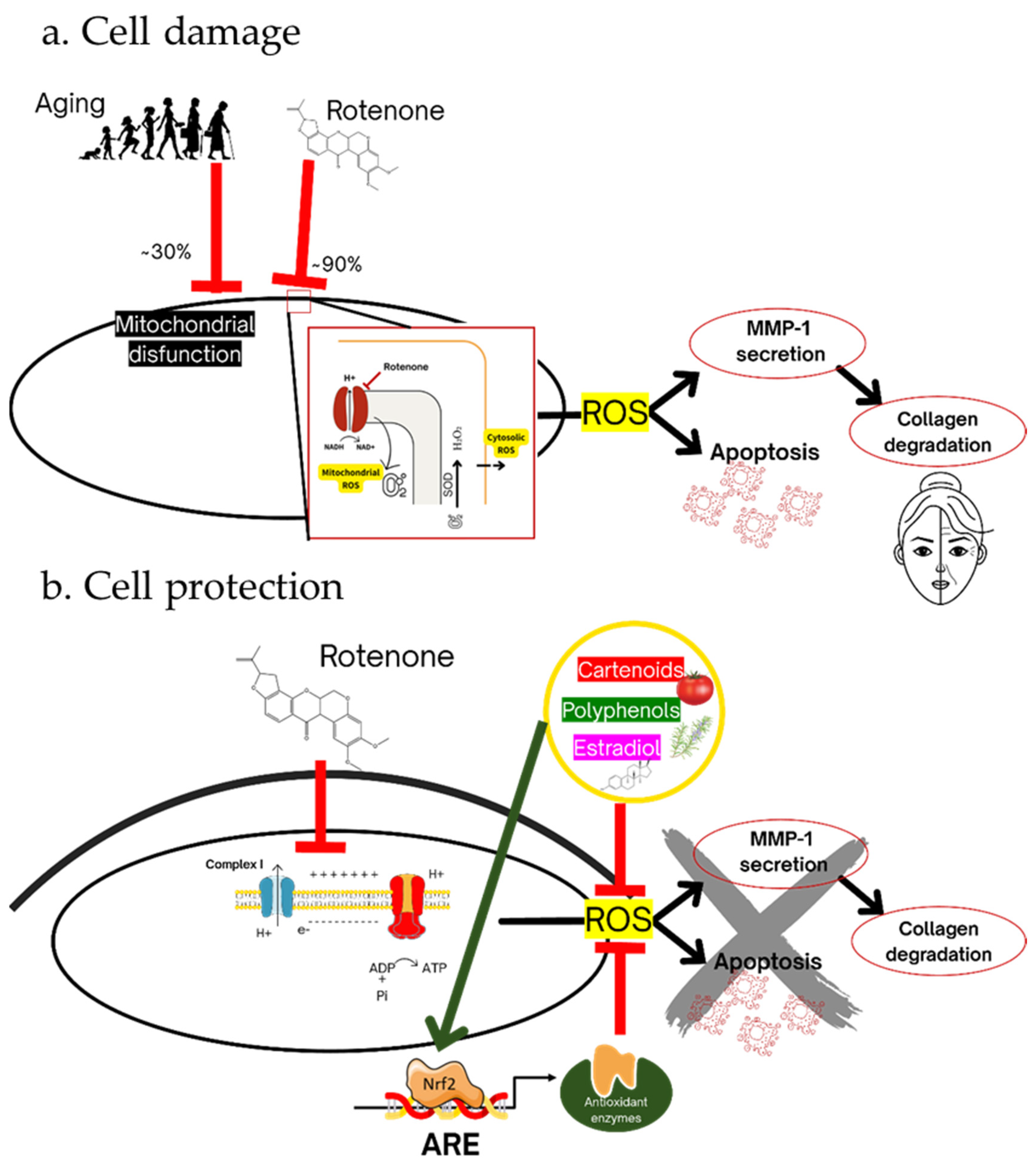

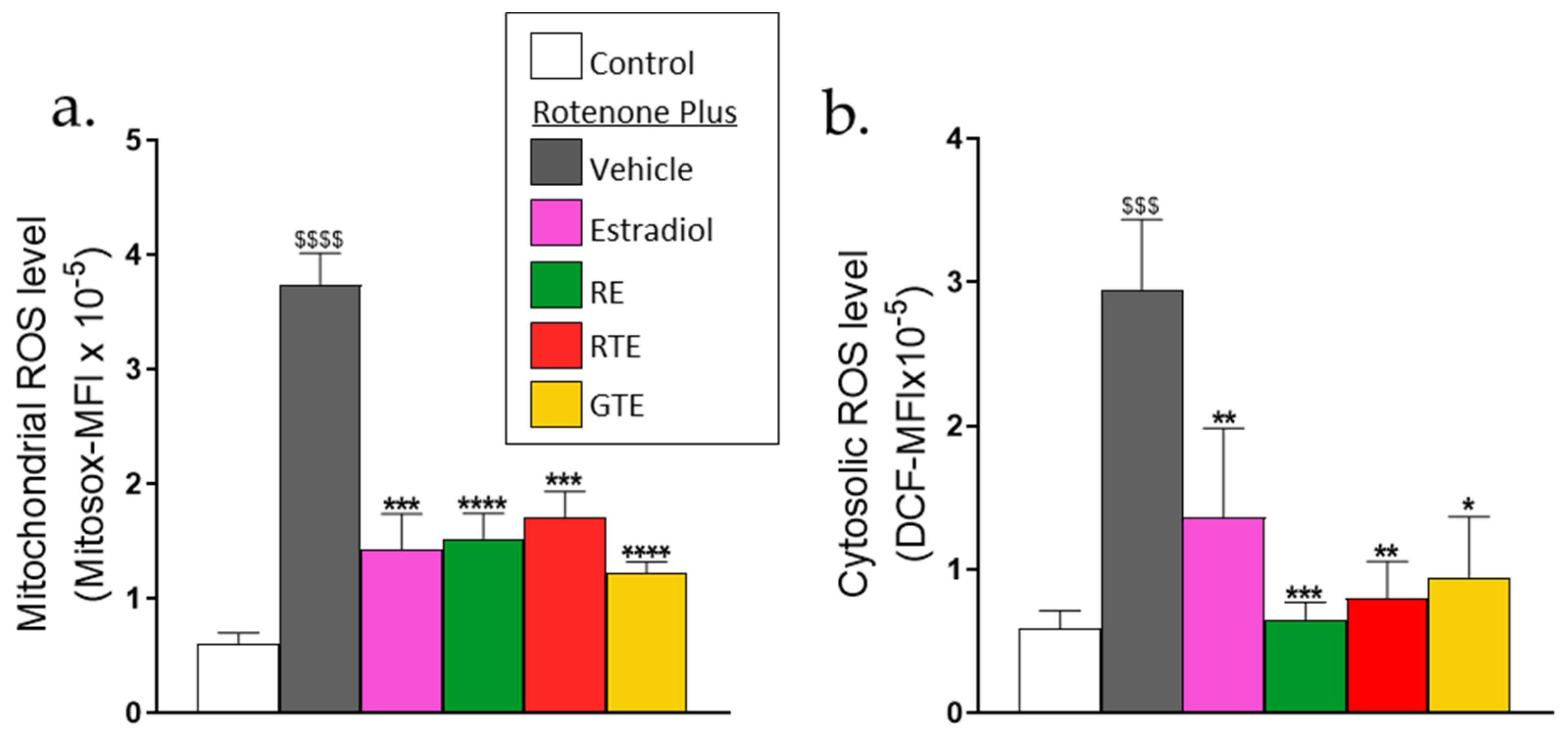

3.1. Mitochondrial and Cytoplasmic ROS Levels in Dermal Fibroblasts Are Increased by Rotenone Treatment and Reduced by Tomato and Rosemary Extracts, and Estradiol

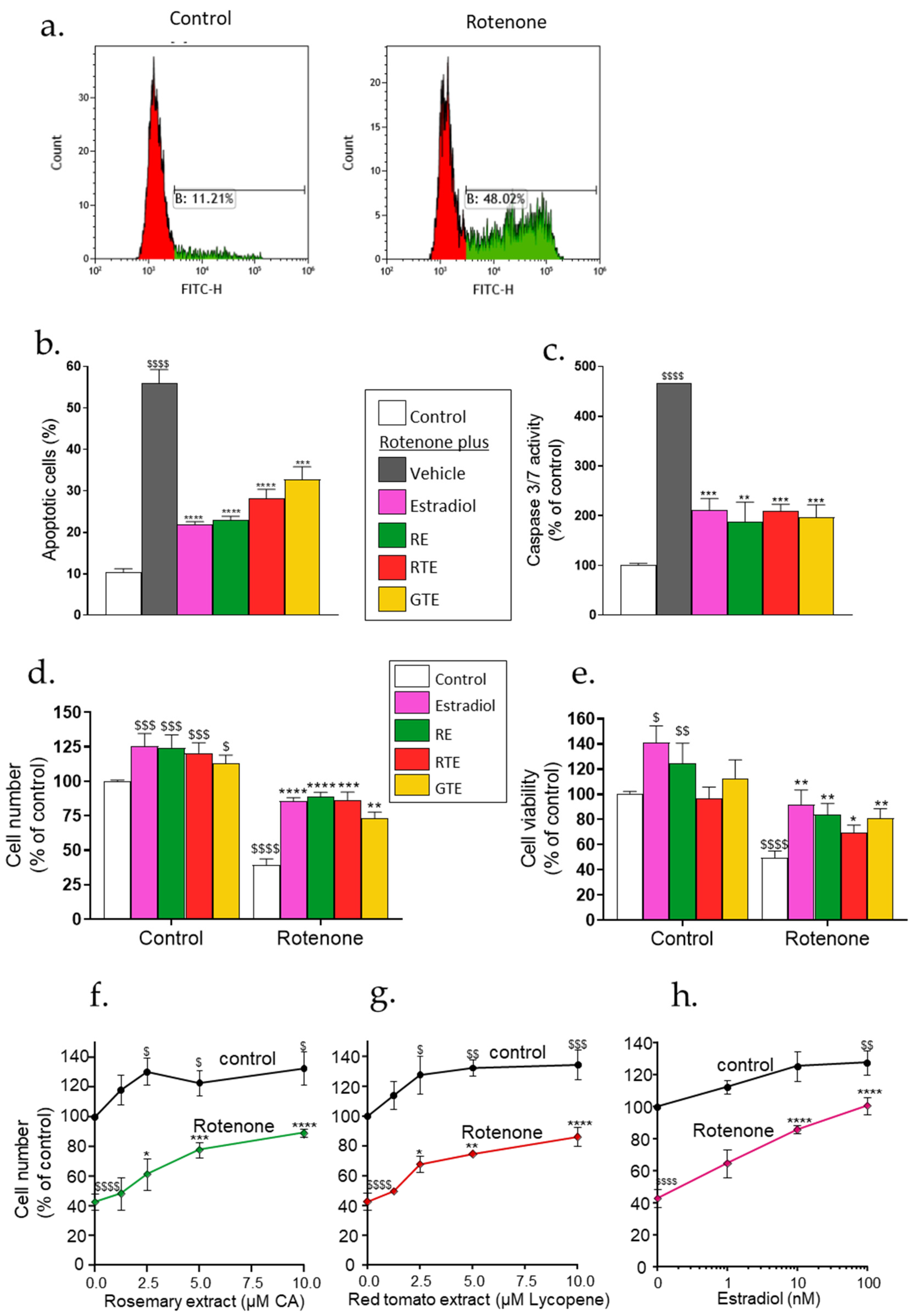

3.2. Rotenone Triggers Apoptotic Cell Death of Dermal Fibroblasts, Which Can Be Reduced by Tomato and Rosemary Extracts and Estradiol

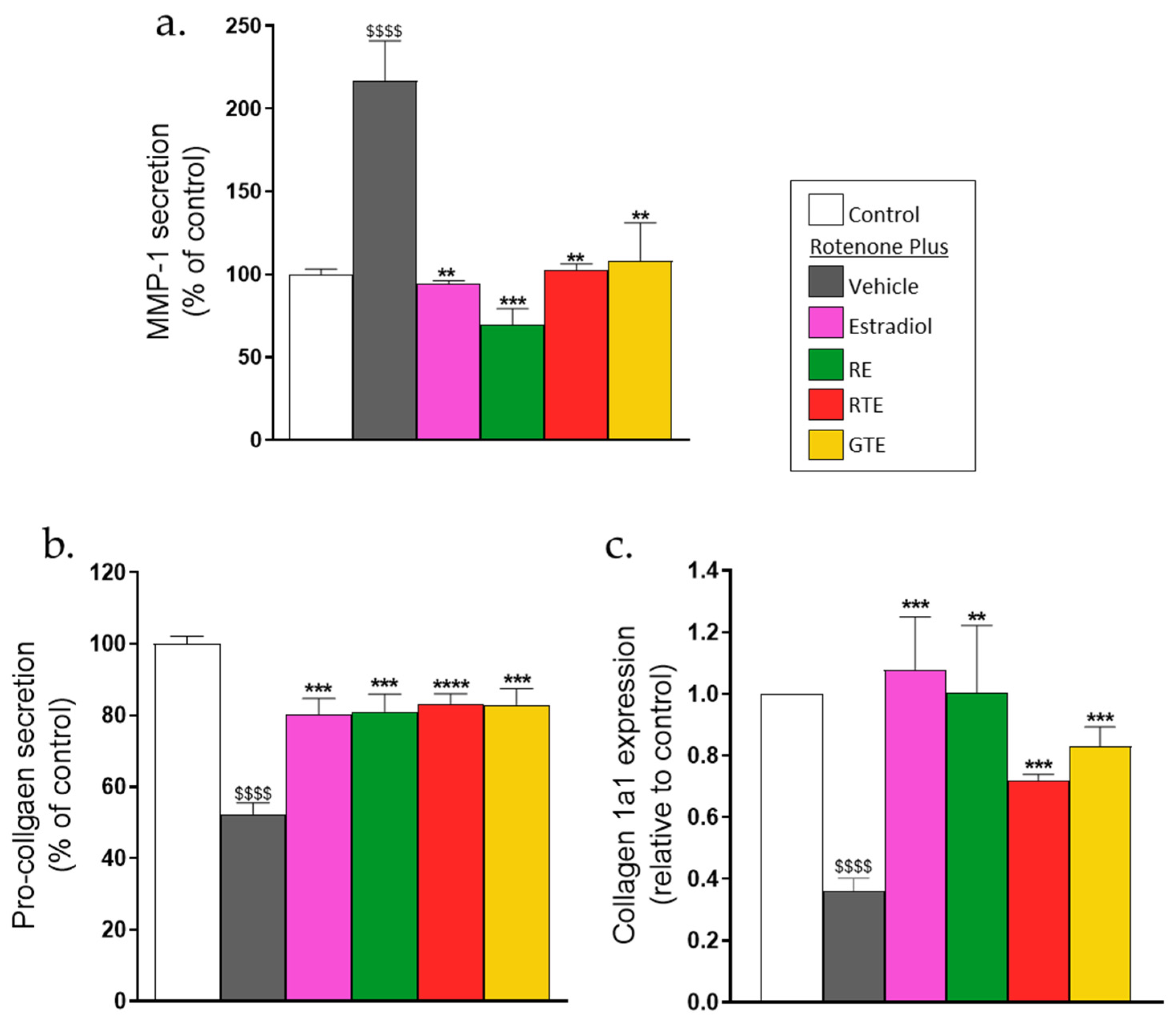

3.3. Rotenone Increases MMP1 and Reduces Collagen 1a1 Secretion. Carotenoids, Polyphenols, and Estradiol Reverse These Effects

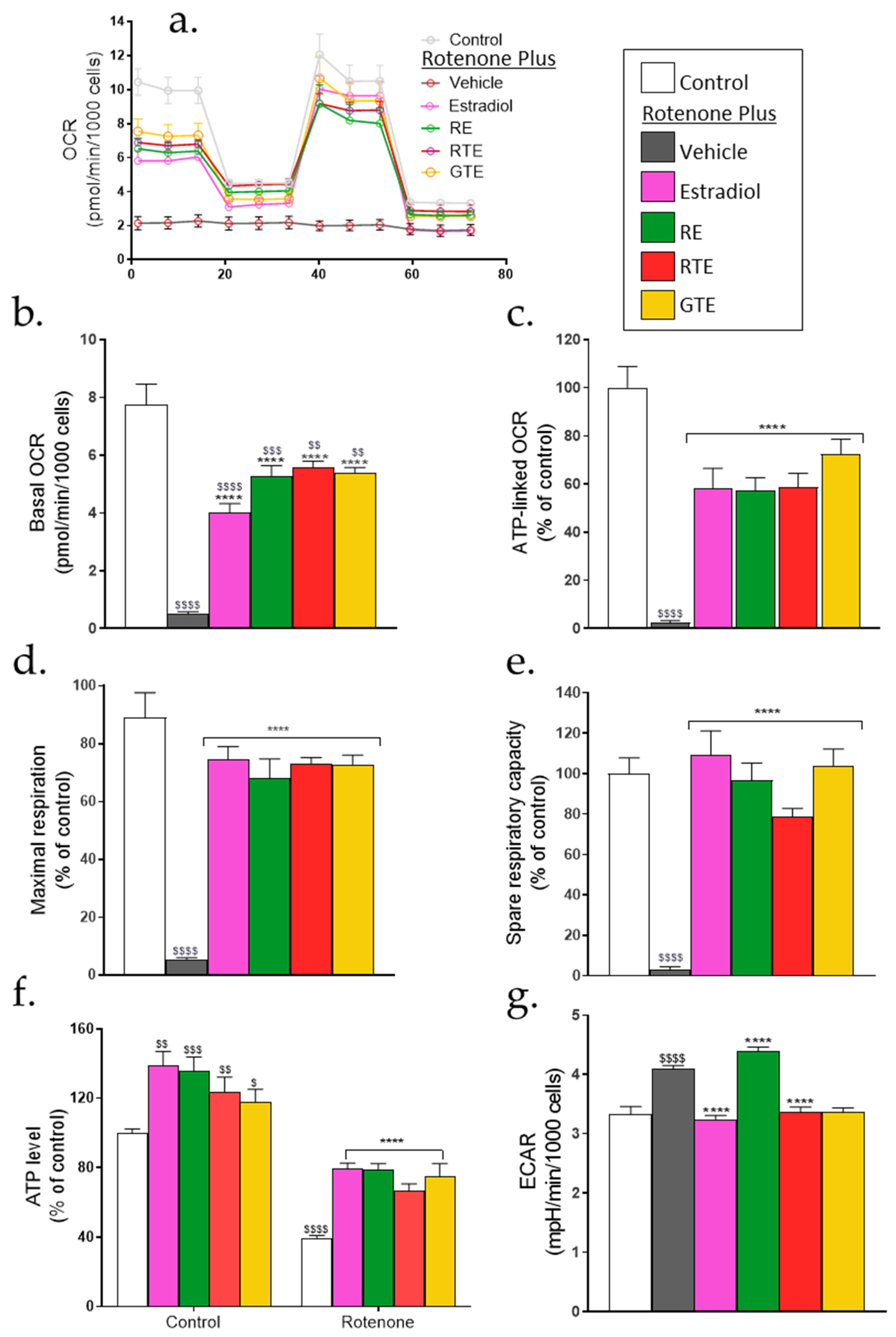

3.4. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Following Exposure to Rotenone and Recovery by Dietary Compounds and Estradiol

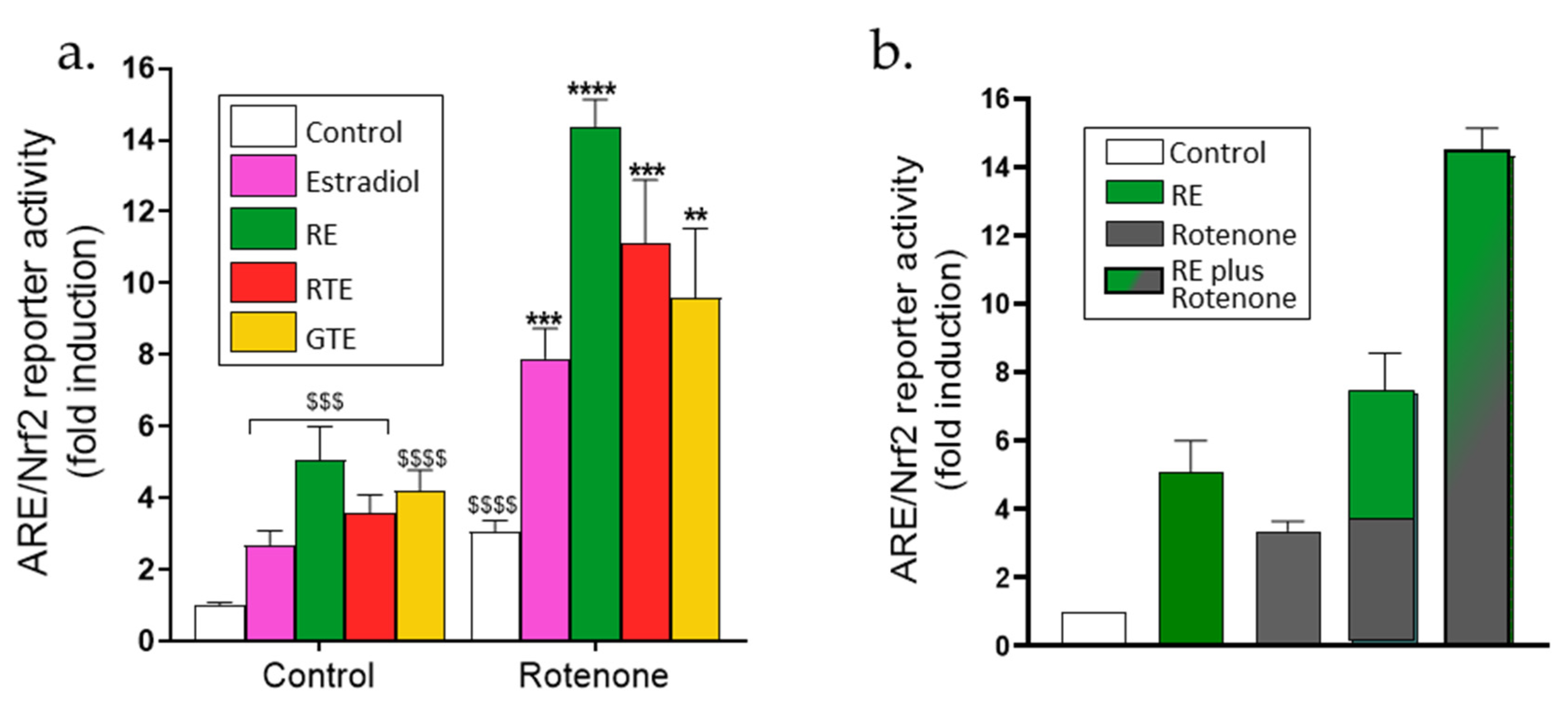

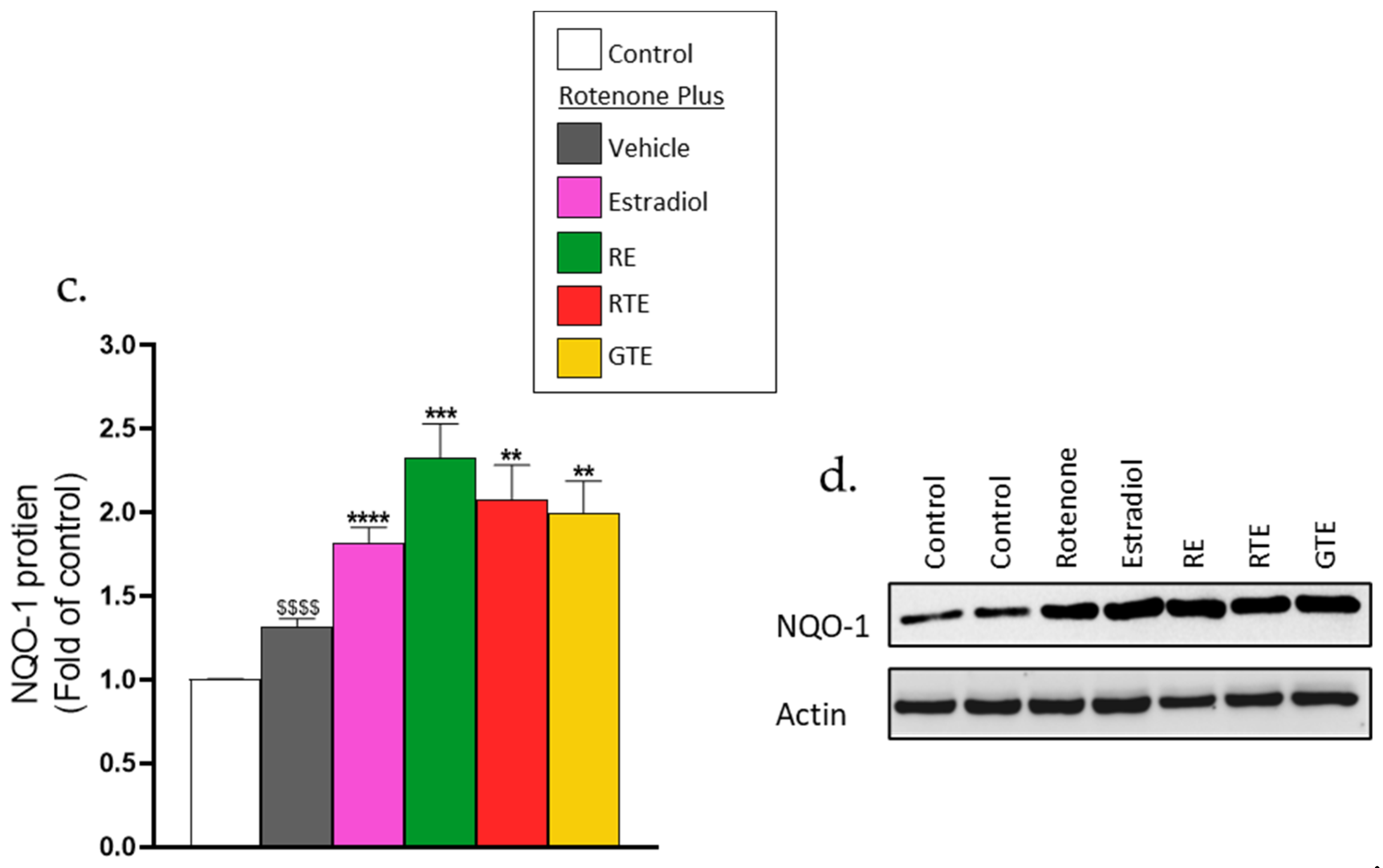

3.5. Increased Activation of ARE/Nrf2 by the Combinations of the Phytonutrients or Estradiol with Rotenone

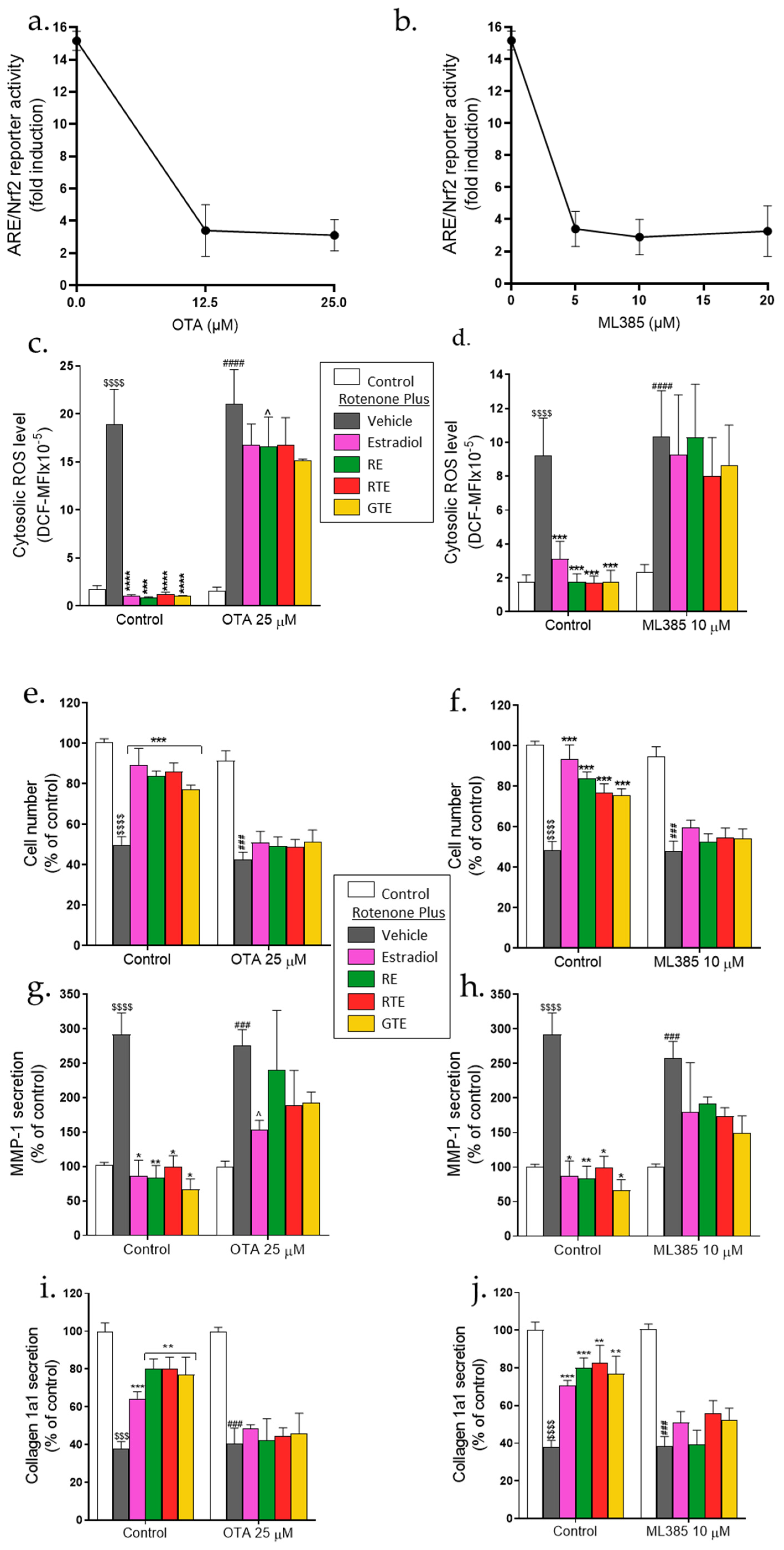

3.6. Activation of ARE/Nrf2 Is Required for Protection from Rotenone-Induced Damage by Dietary Compounds and Estradiol

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bickers, D.R.; Athar, M. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of skin disease. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2006, 126, 2565-2575. [CrossRef]

- Dan Dunn, J.; Alvarez, L.A.J.; Zhang, X.; Soldati, T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: A nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biology 2015, 6, 472-485. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betteridge, D.J. What is oxidative stress? Metabolism 2000, 49, 3-8. [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.D.; Huang, B.-W.; Tsuji, Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cellular Signalling 2012, 24, 981-990. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, V.; Mishra, S.K.; Pant, H.C. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Advances in Pharmacological Sciences 2011, 2011, 572634. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmiento-Salinas, F.L.; Perez-Gonzalez, A.; Acosta-Casique, A.; Ix-Ballote, A.; Diaz, A.; Treviño, S.; Rosas-Murrieta, N.H.; Millán-Perez-Peña, L.; Maycotte, P. Reactive oxygen species: Role in carcinogenesis, cancer cell signaling and tumor progression. Life Sciences 2021, 284, 119942. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigis, M.C.; Yankner, B.A. The aging stress response. Mol Cell 2010, 40, 333-344. [CrossRef]

- Bratic, A.; Larsson, N.-G. The role of mitochondria in aging. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2013, 123, 951-957. [CrossRef]

- Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Functional role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in physiology. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2016, 100, 81-85. [CrossRef]

- Jastroch, M.; Divakaruni, A.S.; Mookerjee, S.; Treberg, J.R.; Brand, M.D. Mitochondrial proton and electron leaks. Essays in Biochemistry 2010, 47, 53-67. [CrossRef]

- Sena, Laura A.; Chandel, Navdeep S. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Molecular Cell 2012, 48, 158-167. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.H. Mitochondrial Medicine for Aging and neurodegenerative diseases. NeuroMolecular Medicine 2008, 10, 291-315. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, V.; Junn, E.; Mouradian, M.M. The role of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2013, 3, 461-491. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HARMAN, D. The biologic clock: The mitochondria? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1972, 20, 145-147. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutmann, J.; Schroeder, P. Role of mitochondria in photoaging of human skin: The defective powerhouse model. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings 2009, 14, 44-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreedhar, A.; Aguilera-Aguirre, L.; Singh, K.K. Mitochondria in skin health, aging, and disease. Cell Death & Disease 2020, 11, 444. [CrossRef]

- Natarelli, N.; Gahoonia, N.; Aflatooni, S.; Bhatia, S.; Sivamani, R.K. Dermatologic manifestations of mitochondrial dysfunction: A review of the literature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 3303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.-r.; Yin, H.-b.; Xu, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.-h.; Yin, Z.-q.; Permatasari, F.; Luo, D. Baicalin protects human skin fibroblasts from ultraviolet A radiation-induced oxidative damage and apoptosis. Free Radical Research 2012, 46, 1458-1471. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinnerthaler, M.; Bischof, J.; Streubel, M.K.; Trost, A.; Richter, K. Oxidative stress in aging human Skin. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 545-589. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lee, W.; Jayawardena, T.U.; Cha, S.H.; Jeon, Y.J. Dieckol, an algae-derived phenolic compound, suppresses airborne particulate matter-induced skin aging by inhibiting the expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases through regulating NF-κB, AP-1, and MAPKs signaling pathways. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 146, 111823. [CrossRef]

- Fam, V.W.; Charoenwoodhipong, P.; Sivamani, R.K.; Holt, R.R.; Keen, C.L.; Hackman, R.M. Plant-based foods for skin health: A Narrative Review. J Acad Nutr Diet 2021. [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Pierzak, M.; Kręcisz, B.; Suliga, E. Bioactive compounds for skin health: A review. Nutrients 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Stahl, W. Nutritional protection against skin damage from sunlight. Annual Review of Nutrition 2004, 24, 173-200. [CrossRef]

- Darawsha, A.; Trachtenberg, A.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. The protective effect of carotenoids, polyphenols, and estradiol on dermal fibroblasts under oxidative stress. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Lee, H.; Noh, J.S.; Jin, C.-Y.; Kim, G.-Y.; Hyun, J.W.; Leem, S.-H.; Choi, Y.H. Hemistepsin A protects human keratinocytes against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress through activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2020, 691, 108512. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Dor, A.; Steiner, M.; Gheber, L.; Danilenko, M.; Dubi, N.; Linnewiel, K.; Zick, A.; Sharoni, Y.; Levy, J. Carotenoids activate the antioxidant response element transcription system. Mol Cancer Ther 2005, 4, 177-186. [CrossRef]

- Linnewiel, K.; Ernst, H.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Ben-Dor, A.; Kampf, A.; Salman, H.; Danilenko, M.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Structure activity relationship of carotenoid derivatives in activation of the electrophile/antioxidant response element transcription system. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 2009, 47, 659-667.

- Calniquer, G.; Khanin, M.; Ovadia, H.; Linnewiel-Hermoni, K.; Stepensky, D.; Trachtenberg, A.; Sedlov, T.; Braverman, O.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Combined effects of carotenoids and polyphenols in balancing the response of skin cells to UV irradiation. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Lu, H.; Xu, Z.; Tong, R.; Shi, J.; Jia, G. Recent advances of natural polyphenols activators for Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2019, 16, e1900400. [CrossRef]

- Heo, H.; Lee, H.; Yang, J.; Sung, J.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, J. Protective activity and underlying mechanism of ginseng seeds against UVB-induced damage in human fibroblasts. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-R.; Kim, D.-W.; Sung, J.; Kim, T.H.; Choi, C.-H.; Lee, S.-J. Astaxanthin inhibits autophagic cell death induced by bisphenol A in human dermal fibroblasts. antioxidants 2021, 10, 1273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoia, P.; Raina, G.; Camillo, L.; Farruggio, S.; Mary, D.; Veronese, F.; Graziola, F.; Zavattaro, E.; Tiberio, R.; Grossini, E. Anti-oxidative effects of 17 β-estradiol and genistein in human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci 2018, 92, 62-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lephart, E.D. A review of the role of estrogen in dermal aging and facial attractiveness in women. J Cosmet Dermatol 2018, 17, 282-288. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.L.; Greiwe, J.S.; Schwen, R.J. Ageing skin: oestrogen receptor β agonists offer an approach to change the outcome. Exp Dermatol 2011, 20, 879-882. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.S.; Tseng, Y.T.; Hsu, Y.Y.; Lo, Y.C. Nrf2-Keap1 antioxidant defense and cell survival signaling are upregulated by 17β-estradiol in homocysteine-treated Dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells. Neuroendocrinology 2013, 97, 232-241. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherer, T.B.; Betarbet, R.; Testa, C.M.; Seo, B.B.; Richardson, J.R.; Kim, J.H.; Miller, G.W.; Yagi, T.; Matsuno-Yagi, A.; Greenamyre, J.T. Mechanism of toxicity in rotenone models of Parkinson's disease. The Journal of Neuroscience 2003, 23, 10756-10764. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooney, R.V.; Joseph Kappock, T.; Pung, A.; Bertram, J.S. Solubilization, cellular uptake, and activity of β-carotene and other carotenoids as inhibitors of neoplastic transformation in cultured cells. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: 1993; Volume 214, pp. 55-68.

- Levy, J.; Bosin, E.; Feldman, B.; Giat, Y.; Miinster, A.; Danilenko, M.; Sharoni, Y. Lycopene is a more potent inhibitor of human cancer cell proliferation than either alpha-carotene or beta-carotene. Nutr Cancer 1995, 24, 257-266. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, R.; Birch-Machin, M. Mitochondria’s role in skin ageing. Biology 2019, 8, 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottenberg, H.; Hoek, J.B. The path from mitochondrial ROS to aging runs through the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 943-955. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kim, C.N.; Yang, J.; Jemmerson, R.; Wang, X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell 1996, 86, 147-157. [CrossRef]

- MA, Y.-S.; CHEN, Y.-C.; LU, C.-Y.; LIU, C.-Y.; WEI, Y.-H. Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 1 and disruption of mitochondrial network in skin fibroblasts of patients with MERRF syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2005, 1042, 55-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Schoeb, T.R.; Bajpai, P.; Slominski, A.; Singh, K.K. Reversing wrinkled skin and hair loss in mice by restoring mitochondrial function. Cell Death & Disease 2018, 9, 735. [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama, Y.; Yamawaki, Y.; Sato, Y.; Muraoka, S.; Yoshida, M.; Okano, Y.; Masaki, H. Decreased mitochondrial function in UVA-irradiated dermal fibroblasts causes the insufficient formation of type I collagen and fibrillin-1 fibers. Journal of Dermatological Science 2022, 108, 22-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, S.; Hu, R.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Lee, H.; Chang, M.; Guan, L. Protective skin aging effects of cherry blossom extract (Prunus Yedoensis) on oxidative stress and apoptosis in UVB-irradiated HaCaT cells. Cytotechnology 2019, 71, 475-487. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gary, A.-S.; Rochette, P.J. Apoptosis, the only cell death pathway that can be measured in human diploid dermal fibroblasts following lethal UVB irradiation. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 18946. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Okada, T.; Konishi, H.; Takahashi, M.; Ito, M.; Asai, J. The effects of ultraviolet A and reactive oxygen species on the mRNA expression of 72-kDa type IV collagenase and its tissue inhibitor in cultured human dermal fibroblasts. Arch Dermatol Res 1996, 288, 39-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J.; Ma, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Ye, M. Luteolin prevents UVB-induced skin photoaging damage by modulating SIRT3/ROS/MAPK Signaling: An in vitro and in vivo studies. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruscotti, I.; Barchiesi, F.; Jackson, E.K.; Imthurn, B.; Stiller, R.; Kim, J.-H.; Schaufelberger, S.; Rosselli, M.; Hughes, C.C.W.; Dubey, R.K. Estradiol stimulates capillary formation by human endothelial progenitor cells. Hypertension 2010, 56, 397-404, doi:. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Venkannagari, S.; Oh, K.H.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Rohde, J.M.; Liu, L.; Nimmagadda, S.; Sudini, K.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Gajghate, S.; et al. Small molecule inhibitor of NRF2 selectively intervenes therapeutic resistance in KEAP1-deficient NSCLC tumors. ACS Chem Biol 2016, 11, 3214-3225. [CrossRef]

- Limonciel, A.; Jennings, P. A review of the evidence that ochratoxin A is an Nrf2 inhibitor: Implications for nephrotoxicity and renal carcinogenicity. Toxins (Basel) 2014, 6, 371-379. [CrossRef]

- Ron-Doitch, S.; Frušić-Zlotkin, M.; Soroka, Y.; Duanis-Assaf, D.; Amar, D.; Kohen, R.; Steinberg, D. eDNA-mediated cutaneous protection against UVB damage conferred by staphylococcal epidermal colonization. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 788. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Xu, T.; Xun, C.; Guo, H.; Cao, R.; Gao, S.; Sheng, W. Carnosic acid protects against ferroptosis in PC12 cells exposed to erastin through activation of Nrf2 pathway. Life Sciences 2021, 266, 118905. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Yu, X.; Huangpu, H.; Yao, F. Ginsenoside Rb3 protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury via activating the antioxidation signaling pathway of PERK/Nrf2/HMOX1. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 109, 254-261. [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.J.; Kew, K.A.; Ryan, T.E.; Pennington, E.R.; Lin, C.-T.; Buddo, K.A.; Fix, A.M.; Smith, C.A.; Gilliam, L.A.; Karvinen, S.; et al. 17β-estradiol directly lowers mitochondrial membrane microviscosity and improves bioenergetic function in skeletal Muscle. Cell Metabolism 2018, 27, 167-179.e167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razmara, A.; Duckles, S.P.; Krause, D.N.; Procaccio, V. Estrogen suppresses brain mitochondrial oxidative stress in female and male rats. Brain Research 2007, 1176, 71-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, T.E.; Yang, S.-H.; Wen, Y.; Simpkins, J.W. Estrogen protection in Friedreich's ataxia skin fibroblasts. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 2742-2749. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, T.E.; Yu, A.E.; Wen, Y.; Yang, S.-H.; Simpkins, J.W. Estrogen prevents oxidative damage to the mitochondria in Friedreich's ataxia skin fibroblasts. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e34600. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, Y.; Nawaz, A.; Kado, T.; Takikawa, A.; Igarashi, Y.; Onogi, Y.; Wada, T.; Sasaoka, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Sasahara, M.; et al. Astaxanthin stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis in insulin resistant muscle via activation of AMPK pathway. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2020, 11, 241-258. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Cao, Z.; Cui, Y.; Huo, S.; Shao, B.; Song, M.; Cheng, P.; Li, Y. Lycopene ameliorates aflatoxin B1-induced testicular lesion by attenuating oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage with Nrf2 activation in mice. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2023, 256, 114846. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, Y.-F.; Liu, X.-T.; Li, Y.-C.; Zhu, H.-M.; Sun, M.-R.; Li, P.; Liu, B.; Yang, H. Songorine promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2 induction during sepsis. Redox Biology 2021, 38, 101771. [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.Y.; Park, S.H.; Yun, S.Y.; Yu, D.S.; Lee, Y.B. Astaxanthin protects ultraviolet b-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in human keratinocytes via intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Ann Dermatol 2022, 34, 125-131. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazekas, Z.; Gao, D.; Saladi, R.N.; Lu, Y.; Lebwohl, M.; Wei, H. Protective effects of lycopene against ultraviolet B-induced photodamage. Nutrition and Cancer 2003, 47, 181-187. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J.; Yang, Z.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Li, Z. Resveratrol treats UVB-induced photoaging by anti-MMP expression, through anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiapoptotic properties, and treats photoaging by Upregulating VEGF-B expression. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2022, 2022, 6037303. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottai, G.; Mancina, R.; Muratori, M.; Di Gennaro, P.; Lotti, T. 17β-estradiol protects human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes against oxidative damage. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2013, 27, 1236-1243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrás, C.; Gambini, J.; López-Grueso, R.; Pallardó, F.V.; Viña, J. direct antioxidant and protective effect of estradiol on isolated mitochondria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease 2009, 1802, 205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, G.J.; Datta, S.C.; Talwar, H.S.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Varani, J.; Kang, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Molecular basis of sun-induced premature skin ageing and retinoid antagonism. Nature 1996, 379, 335-339. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.J.; Iwasaki, A.; Chien, A.L.; Kang, S. UVB-mediated DNA damage induces matrix metalloproteinases to promote photoaging in an AhR- and SP1-dependent manner. JCI Insight 2022, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siwik, D.A.; Pagano, P.J.; Colucci, W.S. Oxidative stress regulates collagen synthesis and matrix metalloproteinase activity in cardiac fibroblasts. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2001, 280, C53-C60. [CrossRef]

- Son, E.D.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, B.G.; Chang, I.S.; Chung, J.H. Topical application of 17β-estradiol increases extracellular matrix protein synthesis by stimulating TGF-β signaling in aged human skin in vivo. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2005, 124, 1149-1161. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, D.H.; Won, C.-H.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, S.; Lee, M.-J.; Chung, J.H. Differential effects of low-dose and high-dose beta-carotene supplementation on the signs of photoaging and type i procollagen gene expression in human Skin in vivo. Dermatology 2010, 221, 160-171. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-H.; Lai, Y.-H.; Lin, T.-P.; Liu, W.-S.; Kuan, L.-C.; Liu, C.-C. Chronic exposure to rhodobacter sphaeroides extract lycogen™ prevents UVA-induced malondialdehyde accumulation and procollagen i down-regulation in human dermal Fibroblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 1686-1699. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galicka, A.; Sutkowska-Skolimowska, J. The beneficial effect of rosmarinic acid on benzophenone-3-induced alterations in human skin fibroblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 11451. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, N.; Conte, J.; Chen, Y.-J.; Natrajan, P.; Taw, M.; Keller, T.; Givant, J.; Tuason, M.; Dulaj, L.; Leonardi, D.; et al. Beneficial regulation of matrixmetalloproteinases and their inhibitors, fibrillar collagens and transforming growth factor-β by Polypodium leucotomos, directly or in dermal fibroblasts, ultraviolet radiated fibroblasts, and melanoma cells. Archives of Dermatological Research 2009, 301, 487-495. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.H.; Joo, Y.H.; Karadeniz, F.; Ko, J.; Kong, C.-S. Syringaresinol inhibits UVA-Induced MMP-1 expression by suppression of MAPK/AP-1 signaling in HaCaT keratinocytes and human dermal fibroblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 3981. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarshish, E.; Hermoni, K.; Sharoni, Y.; Muizzuddin, N. Effect of Lumenato oral supplementation on plasma carotenoid levels and improvement of visual and experiential skin attributes. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2022, 21, 4042-4052. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-I.; Han, H.-S.; Kim, J.-M.; Park, G.; Jang, Y.-P.; Shin, Y.-K.; Ahn, H.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, K.-T. Eisenia bicyclis extract repairs uvb-induced skin photoaging in vitro and in vivo: Photoprotective effects. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 693. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).