Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Preeclampsia

Obesity and Preeclampsia

Insulin

Leptin

ASB4

ASB4 and PE

Conclusion and Future Direction

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saftlas, A.F.; et al. Epidemiology of preeclampsia and eclampsia in the United States, 1979-1986. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990, 163, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananth, C.V.; Keyes, K.M.; Wapner, R.J. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ 2013, 347, f6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, A.B.; et al. Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987-2004. Am J Hypertens 2008, 21, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, D.; Peterson, E. A critical review of early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2011, 66, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetti, T.J.; Kates, R.; Williams, V. Hemodynamic observations in severe preeclampsia complicated by pulmonary edema. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985, 152, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drislane, F.W.; Wang, A.M. Multifocal cerebral hemorrhage in eclampsia and severe pre-eclampsia. J Neurol 1997, 244, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morriss, M.C.; et al. Cerebral blood flow and cranial magnetic resonance imaging in eclampsia and severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 1997, 89, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, F.G.; Fernandez, C.O.; Hernandez, C. Blindness associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995, 172, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisonkova, S.; Joseph, K.S. Incidence of preeclampsia: risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013, 209, 544 e1–544 e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegard, R.A.; et al. Preeclampsia and fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 2000, 96, 950–955. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, R.; et al. Influence of pre-eclampsia on fetal growth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2003, 13, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibai, B.M.; et al. Aggressive versus expectant management of severe preeclampsia at 28 to 32 weeks' gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994, 171, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.M.; Gammill, H. Pre-eclampsia and cardiovascular disease in later life. The Lancet 2005, 366, 961–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, J.A.; et al. Preeclampsia and cognitive impairment later in life. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2017, 217, e1–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojczakowski, W.; et al. Preeclampsia and Cardiovascular Risk for Offspring. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, E.; et al. Pre-eclampsia. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.-J.; Seow, K.-M.; Chen, K.-H. Preeclampsia: Recent Advances in Predicting, Preventing, and Managing the Maternal and Fetal Life-Threatening Condition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odigboegwu, O.; Pan, L.J.; Chatterjee, P. Use of Antihypertensive Drugs During Preeclampsia. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

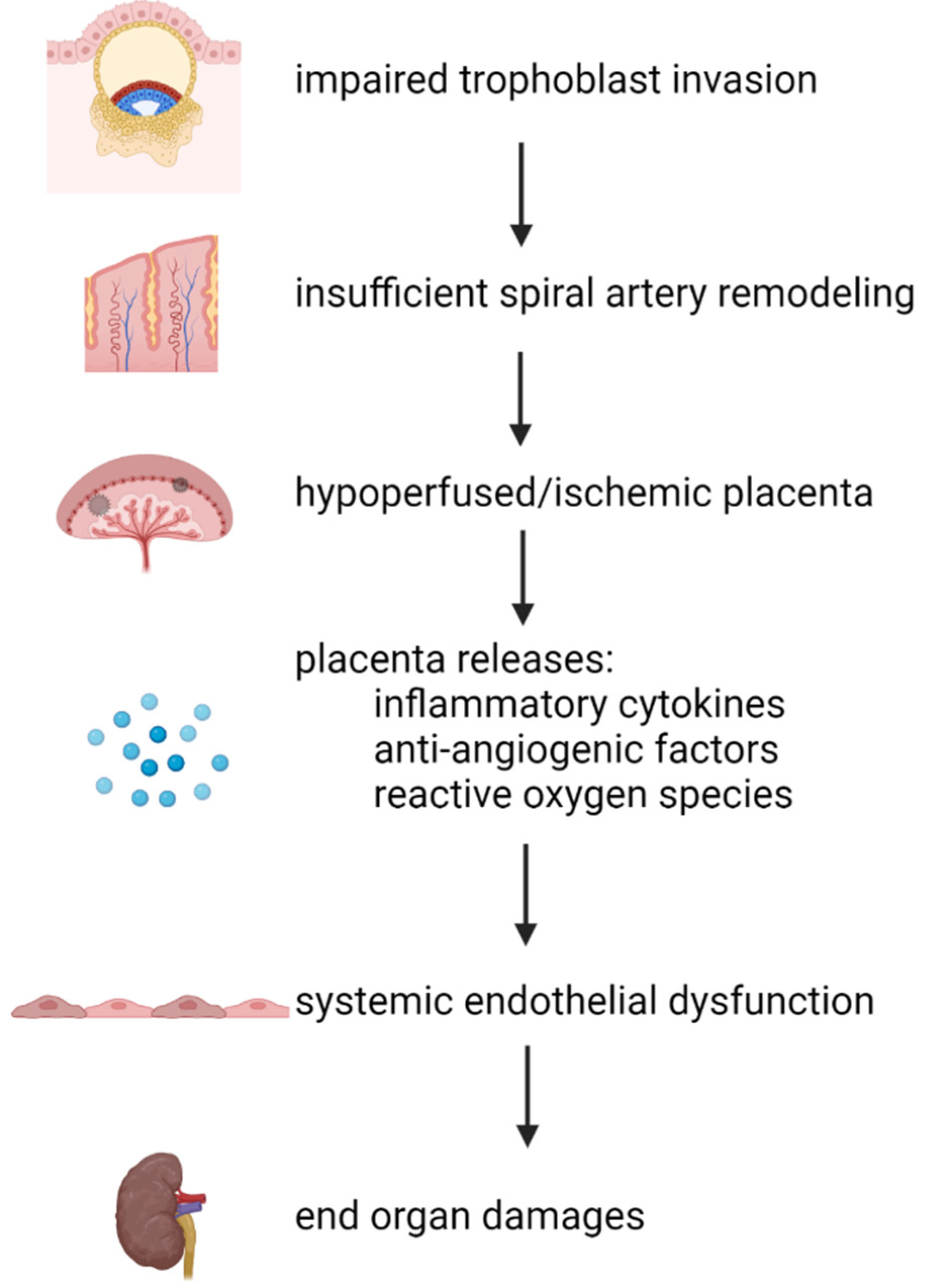

- Staff, A.C. The two-stage placental model of preeclampsia: An update. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2019, 134-135, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, P.; Black, S.; Huppertz, B. Endovascular Trophoblast Invasion: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Intrauterine Growth Retardation and Preeclampsia. Biology of Reproduction 2003, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, S.E.; et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2003, 111, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catov, J.M.; et al. Risk of early or severe pre-eclampsia related to pre-existing conditions. Int J Epidemiol 2007, 36, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaal, M.; le Roux, C.W.; Docherty, N.G. Morbidity and mortality associated with obesity. Annals of Translational Medicine 2017, 5, 161–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, B.; et al. Health in Preconception, Pregnancy and Postpartum Global Alliance: International Network Preconception Research Priorities for the Prevention of Maternal Obesity and Related Pregnancy and Long-Term Complications. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunwole, S.M.; Zera, C.A.; Stanford, F.C. Obesity Management in Women of Reproductive Age. Jama 2021, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.M.; et al. The Role of Obesity in Preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens 2011, 1, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, D.R. ; M. A. Morris, and J.C. Gambone, Obesity pandemic: causes, consequences, and solutions-but do we have the will? Fertil Steril 2017, 107, 833–839. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; et al. Maternal body mass index and risk of birth and maternal health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2015, 16, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, A.K.; et al. Super-obesity and risk for early and late pre-eclampsia. BJOG 2010, 117, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, L.M.; et al. The risk of preeclampsia rises with increasing prepregnancy body mass index. Ann Epidemiol 2005, 15, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvera, S.; Solivan-Rivera, J.; Loureiro, Z.Y. Angiogenesis in adipose tissue and obesity. Angiogenesis 2022, 25, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, I.; et al. Obesity-Associated Oxidative Stress: Strategies Finalized to Improve Redox State. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 10497–10538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frühbeck, G.; et al. Normalization of adiponectin concentrations by leptin replacement in ob/ob mice is accompanied by reductions in systemic oxidative stress and inflammation. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryk, E.; et al. Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in the obese may develop as part of a homeostatic response to elevated free fatty acids: A mechanistic case-control and a population-based cohort study. EBioMedicine 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magkos, F.; Wang, X.; Mittendorfer, B. Metabolic actions of insulin in men and women. Nutrition 2010, 26, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulovski, N.; et al. Insulin signaling is an essential regulator of endometrial proliferation and implantation in mice. The FASEB Journal 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Chaudhry, P.; Asselin, E. Bridging endometrial receptivity and implantation: network of hormones, cytokines, and growth factors. Journal of Endocrinology 2011, 210, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaglino, M.B.; et al. Bioinformatics approach reveals evidence for impaired endometrial maturation before and during early pregnancy in women who developed preeclampsia. Hypertension 2015, 65, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, B.B.; Flier, J.S. Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2000, 106, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasumov, T.; et al. Improved insulin sensitivity after exercise training is linked to reduced plasma C14:0 ceramide in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015, 23, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.M.; et al. Insulin resistance does not affect early embryo development but lowers implantation rate in in vitro maturation–in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer cycle. Clinical Endocrinology 2013, 79, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piltonen, T.T. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Endometrial markers. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2016, 37, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; et al. Mice endometrium receptivity in early pregnancy is impaired by maternal hyperinsulinemia. Molecular Medicine Reports 2017, 15, 2503–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Caron, K.M. Haploinsufficiency for Adrenomedullin Reduces Pinopodes and Diminishes Uterine Receptivity in Mice1. Biology of Reproduction 2008, 79, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujvari, D.; et al. Prokineticin 1 is up-regulated by insulin in decidualizing human endometrial stromal cells. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2017, 22, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, M.; Mauro, M.; Williams, Z. Direct toxicity of insulin on the human placenta and protection by metformin. Fertility and Sterility 2019, 111, 489–496e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; et al. Insulin Exhibits an Antiproliferative and Hypertrophic Effect in First Trimester Human Extravillous Trophoblasts. Reproductive Sciences 2017, 24, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; et al. Calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase IV in trophoblast cells under insulin resistance: functional and metabolomic analyses. Mol Med 2023, 29, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-a.; et al. Reciprocal Relationships Between Insulin Resistance and Endothelial Dysfunction. Circulation 2006, 113, 1888–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusi, K.; et al. Insulin resistance differentially affects the PI 3-kinase– and MAP kinase–mediated signaling in human muscle. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2000, 105, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafidis, P.A.; Bakris, G.L. Insulin and Endothelin: An Interplay Contributing to Hypertension Development? The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2007, 92, 379–385. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero, A.; et al. Leptin system in embryo development and implantation: a protein in search of a function. Reprod Biomed Online 2005, 10, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, N.M.; et al. Leptin Requirement for Conception, Implantation, and Gestation in the Mouse. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 5198–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederich, R.C.; et al. Leptin levels reflect body lipid content in mice: evidence for diet-induced resistance to leptin action. Nat Med 1995, 1, 1311–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffei, M.; et al. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat Med 1995, 1, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Considine, R.V.; et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendieta Zeron, H.; et al. Hyperleptinemia as a prognostic factor for preeclampsia: a cohort study. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2012, 55, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeboah, F.A.; et al. Adiposity and hyperleptinemia during the first trimester among pregnant women with preeclampsia. Int J Womens Health 2017, 9, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, S.M.; et al. Leptin and leptin-binding activity in women with recurrent miscarriage: correlation with pregnancy outcome. Human Reproduction 2001, 16, 2008–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.-H.; et al. Leptin down-regulates γ-ENaC expression: a novel mechanism involved in low endometrial receptivity. Fertility and Sterility 2015, 103, 228–235e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; et al. Leptin inhibits decidualization and enhances cell viability of normal human endometrial stromal cells. Int J Mol Med 2003, 12, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; et al. Role of leptin in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Placenta 2023, 142, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.C.; et al. Establishment and characterization of a human first-trimester extravillous trophoblast cell line (TEV-1). J Soc Gynecol Investig 2005, 12, e21–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; et al. Effect of leptin on cytotrophoblast proliferation and invasion. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2009, 29, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sultan, A.I.; Al-Elq, A.H. Leptin levels in normal weight and obese saudi adults. J Family Community Med 2006, 13, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; et al. Leptin Promotes HTR-8/SVneo Cell Invasion via the Crosstalk between MTA1/WNT and PI3K/AKT Pathways. Disease Markers 2022, 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; et al. Leptin-Promoted Human Extravillous Trophoblast Invasion Is MMP14 Dependent and Requires the Cross Talk Between Notch1 and PI3K/Akt Signaling1. Biology of Reproduction 2014, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, Y.; et al. Asb4, Ata3, and Dcn Are Novel Imprinted Genes Identified by High-Throughput Screening Using RIKEN cDNA Microarray. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2002, 290, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohroki, J.; et al. ASB proteins interact with Cullin5 and Rbx2 to form E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes. FEBS Letters 2005, 579, 6796–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.E.; et al. ASB4 Is a Hydroxylation Substrate of FIH and Promotes Vascular Differentiation via an Oxygen-Dependent Mechanism. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2023, 27, 6407–6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linossi, E.M. ; S. E. Nicholson, The SOCS box—Adapting proteins for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. IUBMB Life 2012, 64, 316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, A.; et al. Asb6, an Adipocyte-specific Ankyrin and SOCS Box Protein, Interacts with APS to Enable Recruitment of Elongins B and C to the Insulin Receptor Signaling Complex. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 38881–38888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kile, B.T.; et al. Cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the ankyrin repeat and SOCS box-containing proteins Asb-1, Asb-2, Asb-3 and Asb-4. Gene 2000, 258, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Y.; et al. Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing protein 4 (Asb-4) colocalizes with insulin receptor substrate 4 (IRS4) in the hypothalamic neurons and mediates IRS4 degradation. BMC Neuroscience 2011, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, A.E.; et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015, 518, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulholland, M.W.; et al. Expression of Ankyrin Repeat and Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling Box Protein 4 (Asb-4) in Proopiomelanocortin Neurons of the Arcuate Nucleus of Mice Produces a Hyperphagic, Lean Phenotype. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Vagena, E.; et al. ASB4 modulates central melanocortinergic neurons and calcitonin signaling to control satiety and glucose homeostasis. Science Signaling 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; et al. Arcuate Nucleus Transcriptome Profiling Identifies Ankyrin Repeat and Suppressor of Cytokine Signalling Box-Containing Protein 4 as a Gene Regulated by Fasting in Central Nervous System Feeding Circuits. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 2005, 17, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagena, E.; et al. ASB4 modulates central melanocortinergic neurons and calcitonin signaling to control satiety and glucose homeostasis. Sci Signal 2022, 15, eabj8204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Y.; et al. Akyrin repeat and SOCS box containing protein 4 (Asb-4) interacts with GPS1 (CSN1) and inhibits c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activity. Cellular Signalling 2007, 19, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, V.; et al. Expression of ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing 4 (ASB4) confers migration and invasion properties of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. BioScience Trends 2014, 8, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacomino, G.; Siani, A. Role of microRNAs in obesity and obesity-related diseases. Genes & Nutrition 2017, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, M.; et al. Regulation of ankyrin repeat and suppressor of cytokine signalling box protein 4 expression in the immortalized murine endothelial cell lines MS1 and SVR: a role for tumour necrosis factor alpha and oxygen. Cell Biochemistry and Function 2011, 29, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, D.; et al. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus, 2022.

- Baker, R.G.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-κB, Inflammation, and Metabolic Disease. Cell Metabolism 2011, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townley-Tilson, W.H.D.; et al. The Ubiquitin Ligase ASB4 Promotes Trophoblast Differentiation through the Degradation of ID2. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.; Kang, B.; Sun, X.H. Id proteins: small molecules, mighty regulators. Curr Top Dev Biol 2014, 110, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.P.; et al. Id2 is a primary partner for the E2-2 basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor in the human placenta. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2004, 222, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townley-Tilson, W.H.; et al. The ubiquitin ligase ASB4 promotes trophoblast differentiation through the degradation of ID2. PLoS One 2014, 9, e89451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; et al. Nicotinamide benefits both mothers and pups in two contrasting mouse models of preeclampsia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 13450–13455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunedomi, R.; et al. Decreased ID2 promotes metastatic potentials of hepatocellular carcinoma by altering secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasorella, A.; et al. Id2 mediates tumor initiation, proliferation, and angiogenesis in Rb mutant mice. Mol Cell Biol 2005, 25, 3563–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayashima, Y.; et al. Insulin Elevates ID2 Expression in Trophoblasts and Aggravates Preeclampsia in Obese ASB4-Null Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, M.; Mauro, M.; Williams, Z. Direct toxicity of insulin on the human placenta and protection by metformin. Fertil Steril 2019, 111, 489–496 e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.; et al. Insulin Exhibits an Antiproliferative and Hypertrophic Effect in First Trimester Human Extravillous Trophoblasts. Reprod Sci 2017, 24, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).