Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Instrumentation

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Study Variables

2.8. Data Analysis

2.8.1. Quantitative Analysis

2.8.1.1. Level of Knowledge of Ergonomics and Posture

2.8.1.2. Postural Behaviour

2.8.1.3. Inferential Statistics

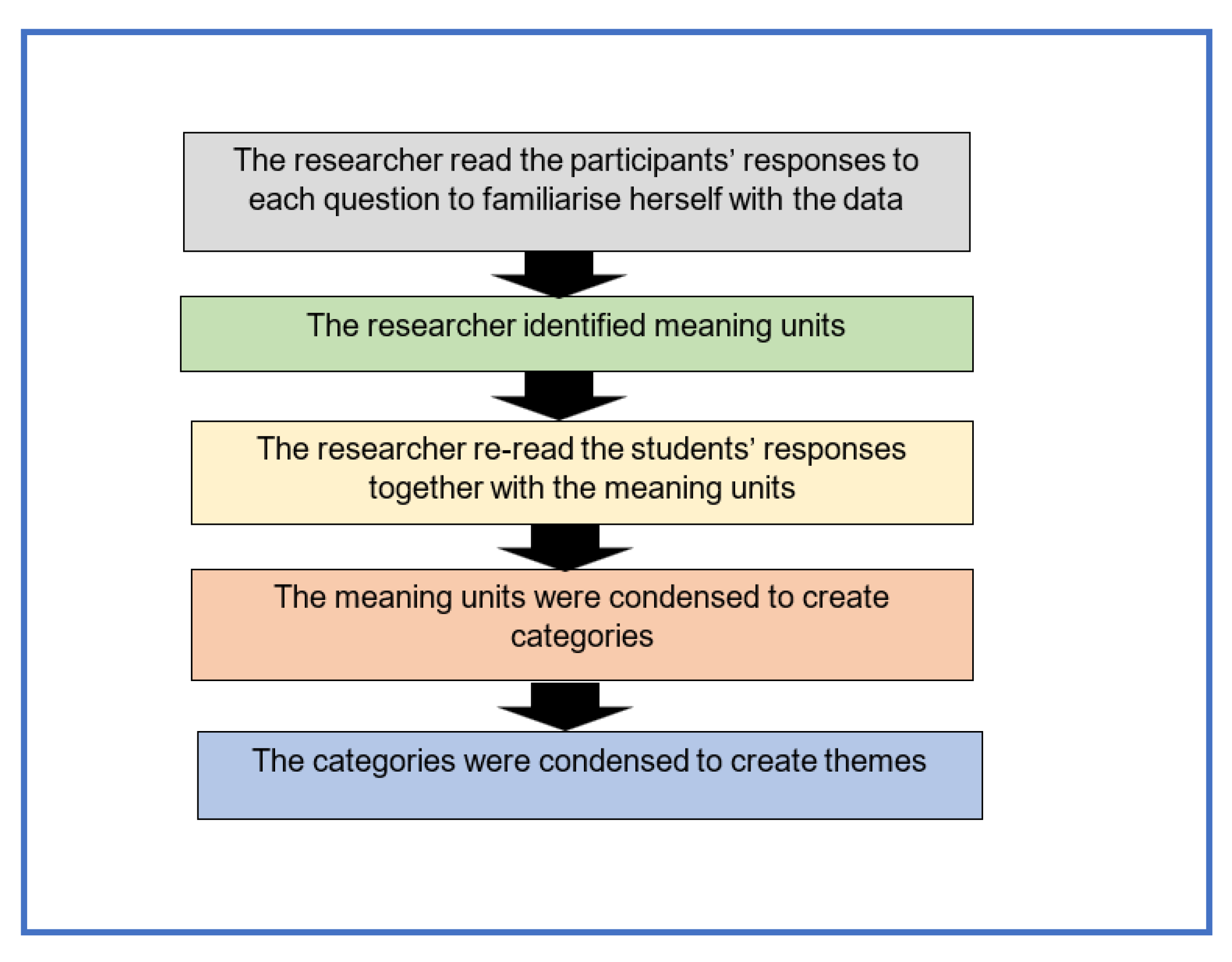

2.8.2. Qualitative Analysis

2.8.2.1. Quality Assurance

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

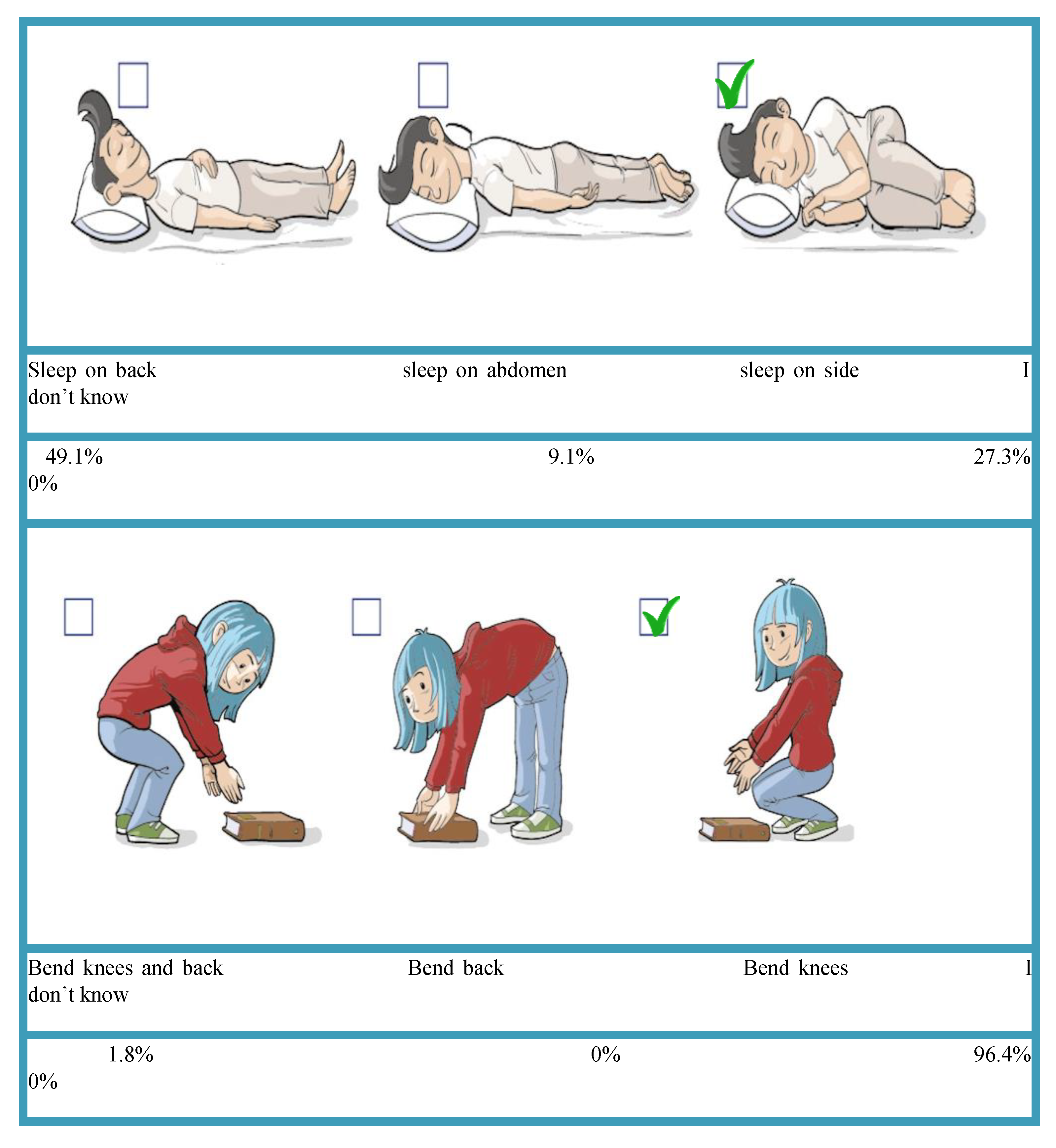

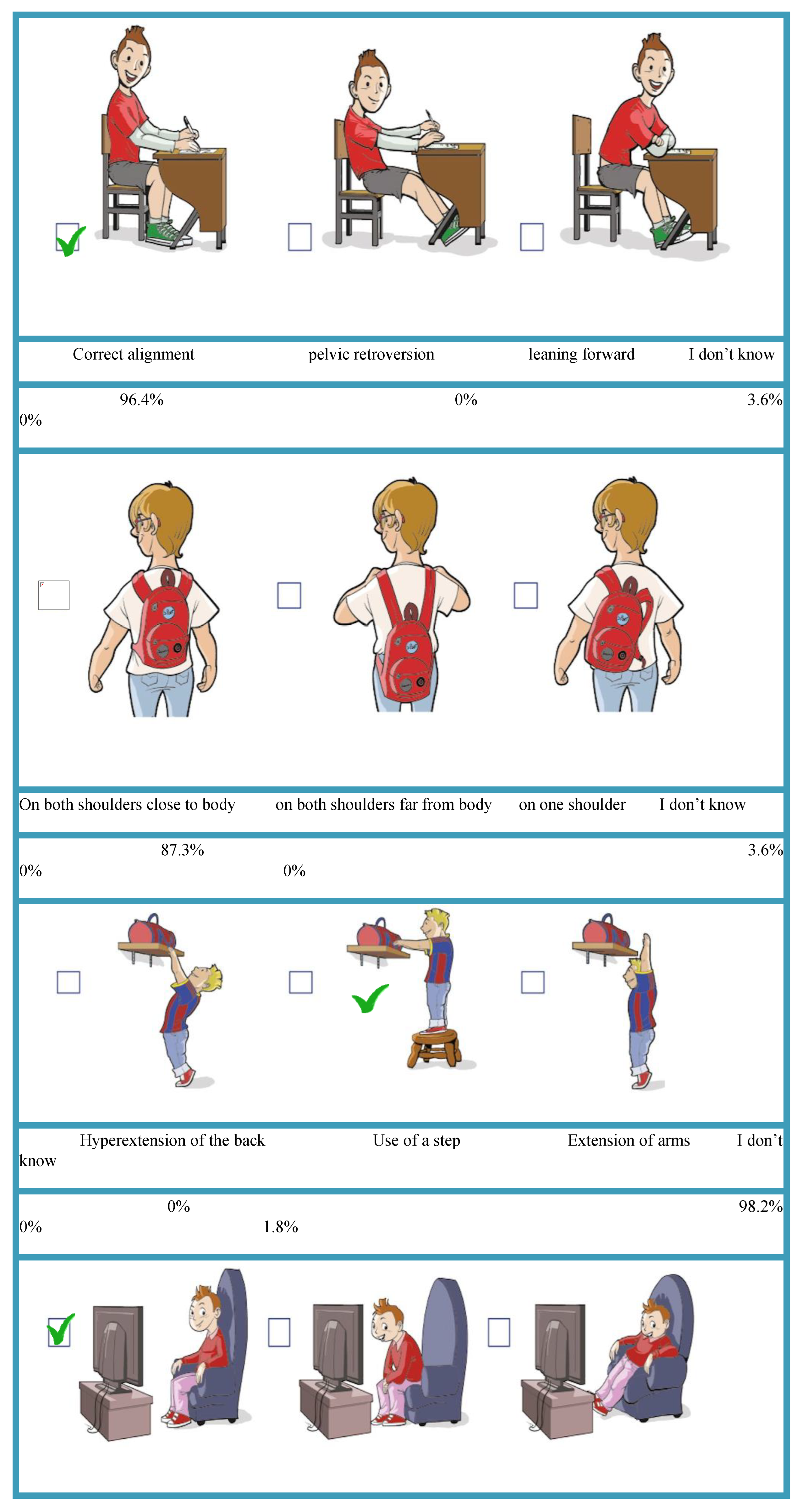

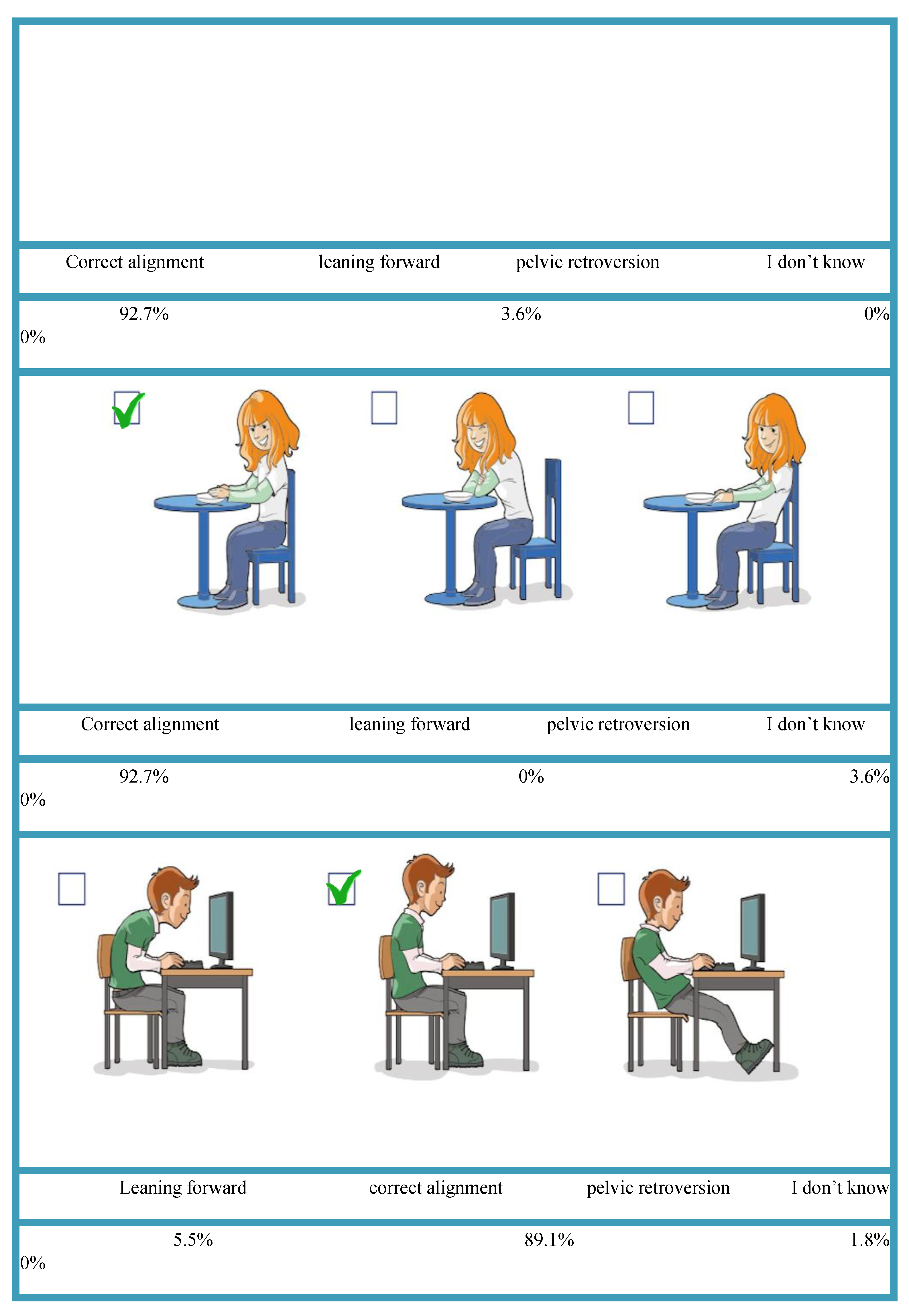

3.2. Knowledge about Ergonomics and Posture

3.3. Relationship between the Knowledge of Ergonomics and Posture with Different Independent Variables (Age, Gender, Course of Study, Academic Year, MSP)

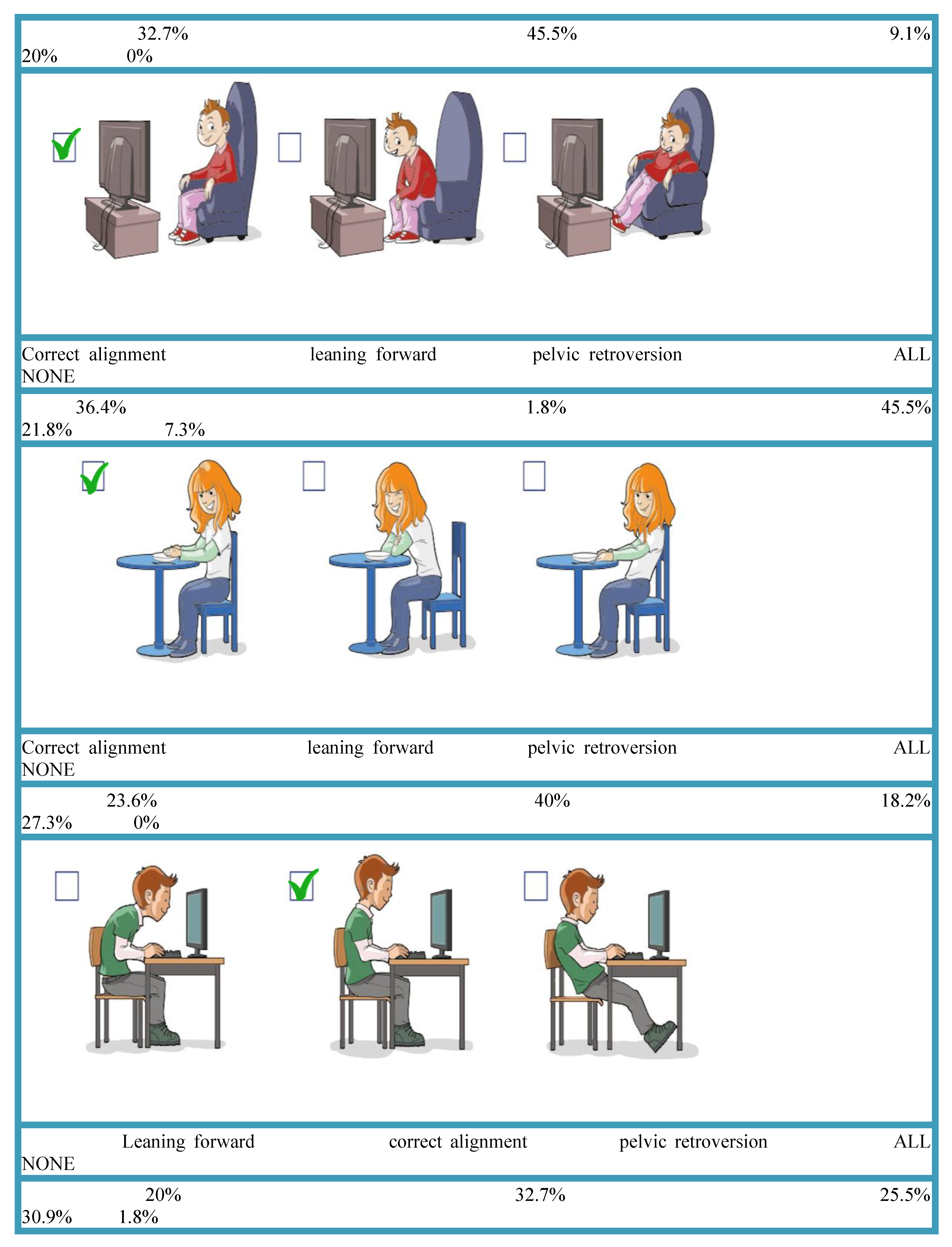

3.4. Postural Behaviour

3.5. Relationship between the Behaviour with Demographics and MSP

3.6. Relationship between the Knowledge of Posture and Ergonomics with Postural Behaviour

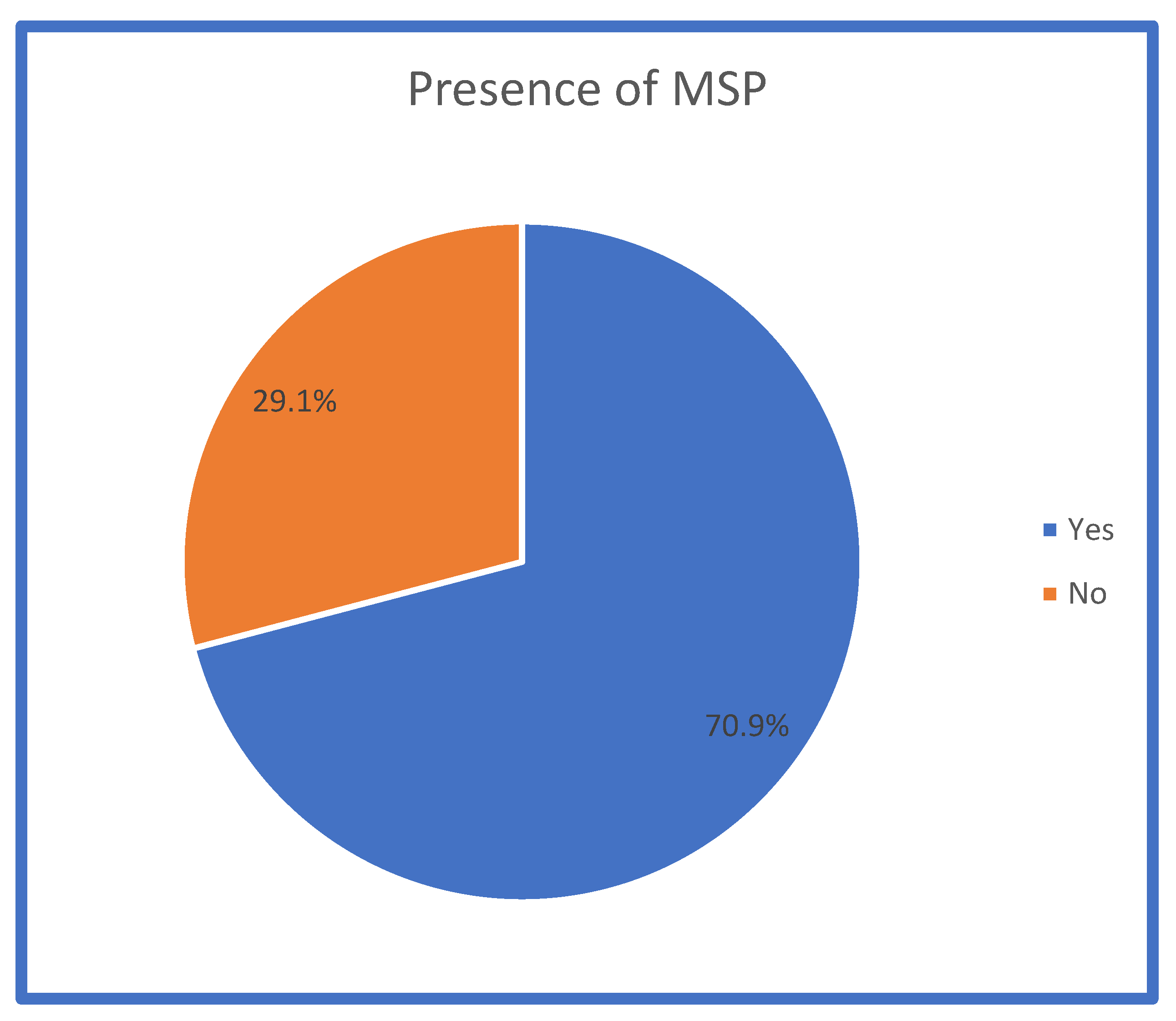

3.7. MSP

3.8. Relationship between Demographic Characteristics with the Incidence of MSP

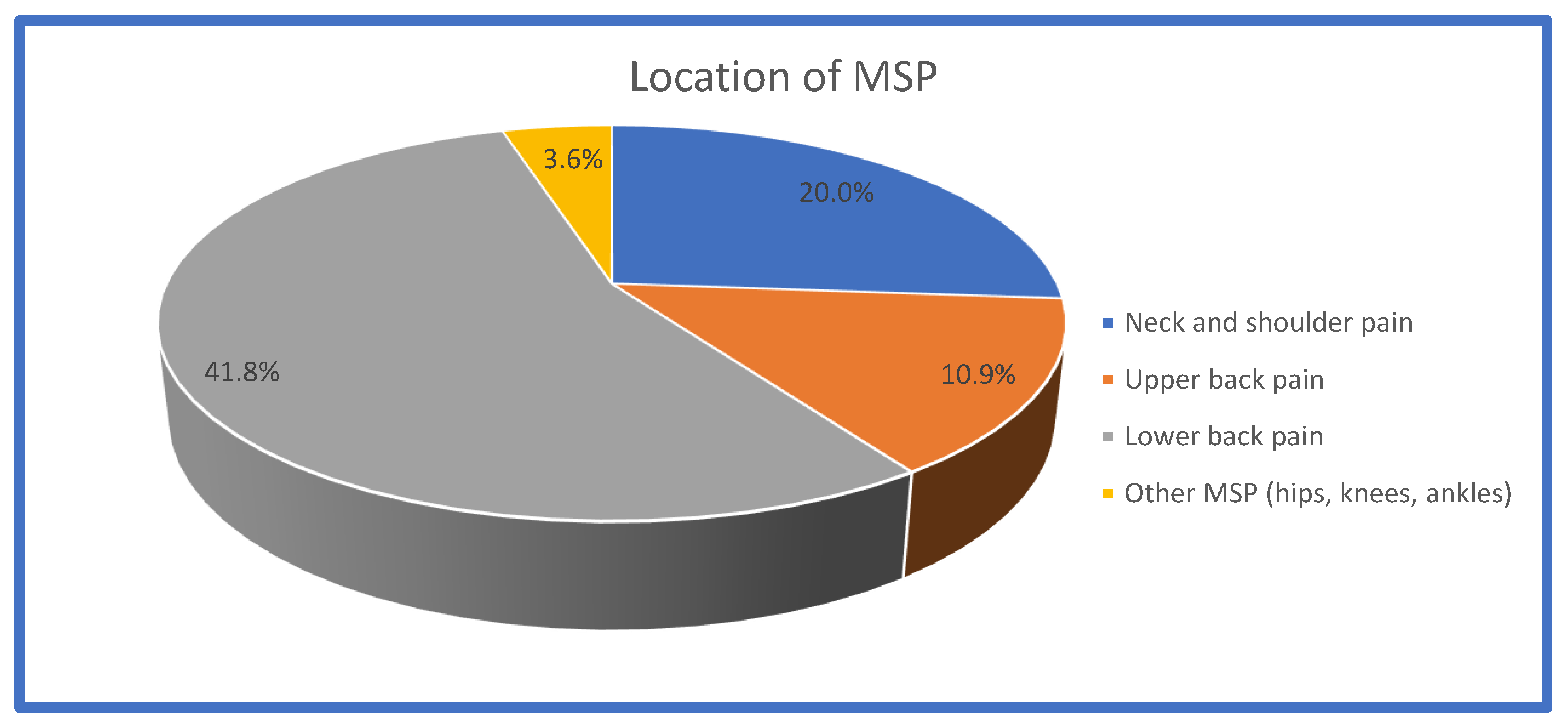

3.9. Relationship between Demographic Characteristics with the Location of MSP

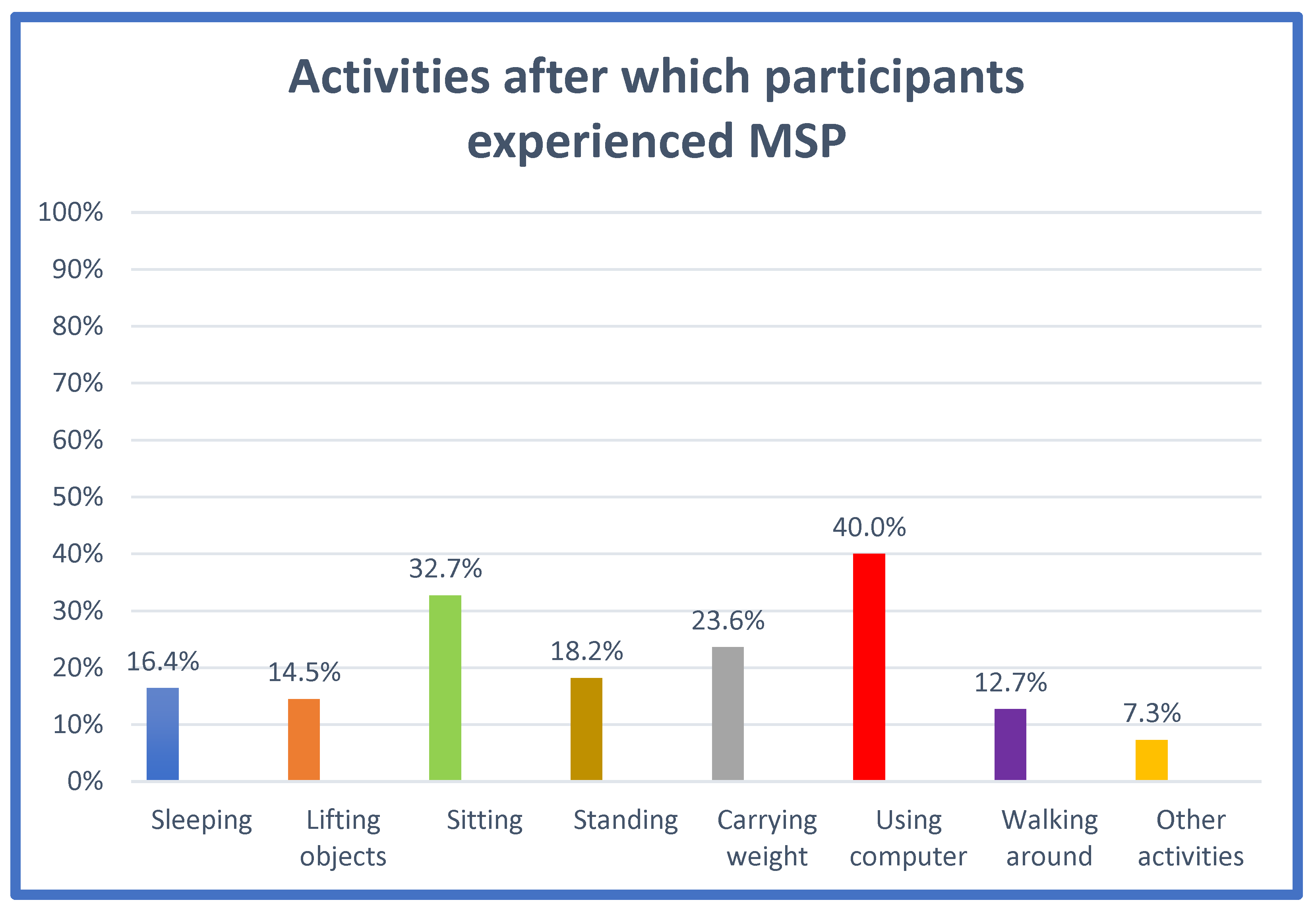

3.10. Relationship between the Location of MSP with the Activities of Daily Living

5.6.6. Qualitative Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Level of Knowledge of Ergonomics and Posture

4.1.1. Relationship between Knowledge with Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Postural Behaviour

4.2.1. The Relationship between Postural Behaviour with Demographic Characteristics

4.3. Association between Knowledge of Ergonomics and Posture with Postural Behaviour

4.4. Incidence and Location of MSP

4.4.1. The Relationship between the Incidence of MSP with Demographic Characteristics

4.5. The Relationship between Knowledge of Ergonomics and Posture with Incidence of MSP

4.6. Association between Postural Behaviour with MSP

4.7. Limitations and Future Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowman, P.J.; Braswell, K.D.; Cohen, J.R.; Funke, J.L.; Landon, H.L.; Martinez, P.I.; Mossbarger, J.N. Benefits of laptop computer ergonomics education to graduate students. Open J. Ther. Rehabil. 2014, 2, 42923–42928. [CrossRef]

- Sirajudeen, M.S.; Siddik, S.S.M. Knowledge of Computer Ergonomics among Computer Science Engineering and Information Technology Students in Karnataka, India. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Heal. 2017, 9, 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Kanaparthy, A.; Kanaparthy, R.; Boreak, N. Postural awareness among dental students in Jizan, Saudi Arabia. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 107–111. [CrossRef]

- Movahhed, T.; Dehghani, M.; Arghami, S.; Arghami, A. Do dental students have a neutral working posture? J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2016, 29, 859–864.

- Garbin, A.Í.; Garbin, C.A.S.; Diniz, D.; Yarid, S. Dental students’ knowledge of ergonomic postural requirements and their application during clinical care. European Journal of Dental Education 2011, 15, 31-35. [CrossRef]

- Cervera-Espert, J.; Pascual-Moscardó, A.; Camps-Alemany, I. Wrong postural hygiene and ergonomics in dental students of the University of Valencia (Spain) (part I). Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2018, 22, 48–56. [CrossRef]

- Rodanant, P.; Promprakai, T. Ergonomic risk assessment from working postures in fourth year undergraduate dental students at Mahidol University. Mahidol Dental Journal 2019, 39, 63-70.

- El-Sallamy, R.M.; Atlam, S.A.; Kabbash, I.; Abd El-fatah, S.; El-Flaky, A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards ergonomics among undergraduates of Faculty of Dentistry, Tanta University, Egypt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 30793–30801. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Karki, I.; Sharma, P. Computer workstation ergonomics: Knowledge testing of State Agricultural Universities (SAU) students. Journal of Human Ecology 2015, 49, 335-339. [CrossRef]

- Kamaroddin, J.H.; Abbas, W.F.; Aziz, M.A.; Sakri, N.M.; Ariffin, A. Investigating ergonomics awareness among university students. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on User Science and Engineering (i-USEr), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 13–15 December 2010; p. 296.

- Dolen, A.P.; Elias, S.M. Knowledge and Practice of Laptop Ergonomics and Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Symptoms among University Students. Asia Pac. Environ. Occup. Health J. 2016, 2, 8–18.

- Srisaard, B. Basic Research, 2nd edition, Suveeriyasan Press, Bangkok, 1992.

- Suchat, P. Social Research Methodology, 10th edition, Sieng-chieng Press, Bangkok, 1997.

- Jaafar, R.; Akmal, A.; Libasin, Z. Awareness of Ergonomics Among the Engineering Students. J. Intelek. 2020, 15, 220–226. [CrossRef]

- Yossria, E.; Mohammed, H.E.; Mohammed, A.H. Relation between body mechanics performance and nurses’ exposure of work place risk factors on the low back pain prevalence, Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Yaqoob, U.; Ali, S.S.; Siddiqui, A.A. Frequency of musculoskeletal pain and associated factors among undergraduate students. Case Reports in Clinical Medicine. 2018, 7, 131-145. [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, C.; Lester, H. Perceived stress during undergraduate medical training: a qualitative study. Medical education 2003, 37, 32-38. [CrossRef]

- Wami, S.D.; Mekonnen, T.H.; Yirdaw, G.; Abere, G. Musculoskeletal problems and associated risk factors among health science students in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Public Health 2020, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Morais, B.X.; Dalmolin, G.d.L.; Andolhe, R.; Dullius, Angela Isabel dos Santos; Rocha, L.P. Musculoskeletal pain in undergraduate health students: prevalence and associated factors. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2019, 53. [CrossRef]

- Algarni, A.D.; Al-Saran, Y.; Al-Moawi, A.; Bin Dous, A.; Al-Ahaideb, A.; Kachanathu, S.J. The prevalence of and factors associated with neck, shoulder, and low-back pains among medical students at university hospitals in central Saudi Arabia. Pain research and treatment 2017. [CrossRef]

- Alshagga, M.A.; Nimer, A.R.; Yan, L.P.; Ibrahim, I.A.A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.S.; Al-Dubai, S.A.R. Prevalence and factors associated with neck, shoulder and low back pains among medical students in a Malaysian Medical College. BMC research notes 2013, 6, 244. [CrossRef]

- McBeth, J.; Jones, K. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology 2007, 21, 403-425.

- Abledu, J.K.; Offei, E.B. Musculoskeletal disorders among first-year Ghanaian students in a nursing college. African health sciences 2015,15, 444-449. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Devi, Y.S.; John, S. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal pain in Indian nursing students. International Journal of Nursing Education 2010, 2, 6-8.

- Smith, D.R.; Choe, M.; Chae, Y.R.; Jeong, J.; Jeon, M.Y.; An, G.J. Musculoskeletal symptoms among Korean nursing students. Contemporary nurse 2005,19,151-160. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.; Leggat, P.A. Musculoskeletal disorders among rural Australian nursing students. Australian Journal of Rural Health 2004,12, 241-245. [CrossRef]

- Movahhed, T.; Dehghani, M.; Arghami, S.; Arghami, A. Do dental students have a neutral working posture? Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation 2016, 29, 859-864.

- Thornton, L.J.; Barr, A.E.; Stuart-Buttle, C.; Gaughan, J.P.; Wilson, E.R.; Jackson, A.D.; Wyszynski, T.C.; Smarkola, C. Perceived musculoskeletal symptoms among dental students in the clinic work environment. Ergonomics 2008, 51, 573-586. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Nimbarte, A.D.; Motabar, H. Physical risk factors associated with the work-related neck/cervical musculoskeletal disorders: A review. Industrial and Systems Engineering Review 2017, 5, 44-60. [CrossRef]

- Wahlstrom, J. Ergonomics, musculoskeletal disorders and computer work. Occupational medicine 2005, 55,168-176. [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.H.; White, P.; Lai, C.W. Musculoskeletal impact of the use of various types of electronic devices on university students in Hong Kong: An evaluation by means of self-reported questionnaire. Manual therapy 2016, 26, 47-53. [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, A.; Vimercati, L.; L’Abbate, N. Musculoskeletal complaints among Italian X-ray technology students: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMC research notes 2010, 3, 114. [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; March, L.; Brooks, P.; Blyth, F.; Woolf, A.; Bain, C.; Williams, G.; Smith, E.; Vos, T.; Barendregt, J.; Murray, C.; Burstein, R.; Buchbinder, R. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2014, 73, 968-974. [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Muñoz, I.; Gómez-Conesa, A.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Prevalence of low back pain in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC pediatrics 2013, 13, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Weleslassie, G.G.; Meles, H.G.; Haile, T.G.; Hagos, G.K. Burden of neck pain among medical students in Ethiopia. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2020, 21, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J.A.; Palmer, J.A.; Venzke, J.W. Ethnic differences in pain perception. Physical therapy reviews 2005, 10, 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.L.; Fillingim, R.B.; Keefe, F. Race, ethnicity and pain. Pain 2001, 94, 133-137.

- Aggarwal, N.; Anand, T.; Kishore, J.; Ingle, G.K. Low back pain and associated risk factors among undergraduate students of a medical college in Delhi. Education for health (Abingdon, England) 2013, 26, 103-108. [CrossRef]

- Dugan, J.E. Teaching the body: a systematic review of posture interventions in primary schools. Educational Review 2018, 70, 643-661. [CrossRef]

- Foster, N.E.; Anema, J.R.; Cherkin, D.; Chou, R.; Cohen, S.P.; Gross, D.P.; Ferreira, P.H.; Fritz, J.M.; Koes, B.W.; Peul, W. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. The Lancet 2018, 391, 2368-2383. [CrossRef]

- Qidwai, W.; Ishaque, S.; Shah, S.; Rahim, M. Adolescent lifestyle and behaviour: A survey from a developing country. PloS one 2010, 5, e12914. [CrossRef]

- Lis-Sochocka, M.; Chylinska-Wrzos, P.; Wawryk-Gawda, E.; Bulak, K.; Jodlowska-Jedrych, B. Back pain and physical activity: Students of the Medical University of Lublin. Current Issues in Pharmacy and Medical Sciences 2015, 28, 278-282. [CrossRef]

- Cardon, G.; Balague, F. Low back pain prevention’s effects in schoolchildren. What is the evidence? European spine journal 2004,13, 663-79.

- Mitchell, T.; O’Sullivan, P.B.; Burnett, A.F.; Straker, L.; Rudd, C. Low back pain characteristics from undergraduate student to working nurse in Australia: a cross-sectional survey. International journal of nursing studies 2008, 45, 1636-1644. [CrossRef]

- Chitara, V.; Nishita, D. Prevalence of Neck Pain among Students in Dentistry. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research 2017, 7, 192-194.

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2008.

- Siedlecki, S.L.; Butler, R.S.; Burchill, C.N. Survey design research: a tool for answering nursing research questions. Clinical nurse specialist 2015, 29, E1-E8.

- Aristegui, R.G. The Effectivity of an Educational Plan on Postural Habits and Prevention of Back Pain in the Children of San Sebastian. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pais Vasco, Leioa, Spain, 2015.

- Salman, M.; Bettany-Saltikov, J.; Kandasamy, G.; Aristegui Racero, G. Development of a Novel Pictorial Questionnaire to Assess Knowledge and Behaviour on Ergonomics and Posture as Well as Musculoskeletal Pain in University Students: Validity and Reliability. Healthcare 2024, 12, 324. [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. How to conduct surveys: a step-by-step guide, sixth edition. SAGE, Los Angeles 2016.

- Field, A. Discovering statistics using SPSS: Book plus code for E version of text. SAGE Publications Limited 2009.

- Bettany-Saltikov, J.; Whittaker, V.J. Selecting the most appropriate inferential statistical test for your quantitative research study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2014, 23, 1520-1531. [CrossRef]

- Hayter, A.J. A proof of the conjecture that the Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons procedure is conservative. The Annals of Statistics 1984, 61-75. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: post-hoc multiple comparisons. Restorative dentistry & endodontics 2015, 40, 172-176.

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursing Plus Open 2016, 2, 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Curry, L.A.; Nembhard, I.M.; Bradley, E.H. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 2009, 119, 1442-1452. [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C.T. Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice 8th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia 2014.

- Burnard, P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse education today 1991, 11, 461-466. [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kanste, O.; Pölkki, T.; Utriainen, K.; Kyngäs, H. Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE open 2014, 4.

- Kubinger, K.D.; Holocher-Ertl, S.; Reif, M.; Hohensinn, C.; Frebort, M. On Minimizing Guessing Effects on Multiple-Choice Items: Superiority of a two solutions and three distractors item format to a one solution and five distractors item format. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 2010, 18, 111-115. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Hillel, M.; Budescu, D.; Attali, Y. Scoring and keying multiple choice tests: A case study in irrationality. Mind & Society 2005, 4, 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Ambusam, S.; Omar, B.; Joseph, L.; Deepashini, H. Effects of document holder on postural neck muscles activity among computer users: a preliminary study. Journal of research in health sciences 2015, 15, 213-217.

- Carb, G.J. The Science of Sitting Made Simple: How to Look and Feel Better with Good Posture in Ten Easy Steps. Posture Press 2008.

- McGill, S. Low back disorders: evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation. Human Kinetics 2015.

- Egoscue, P.; Gittines, R. Pain Free at Your PC: Using a Computer Doesn’t Have to Hurt. Bantam 2009.

- Homola, S. The Chiropractor’s Self-Help Back and Body Book. First edition, Hunter House Publishers, Canada 2002.

- Paterson, J. E-Book Teaching Pilates for Postural Faults, Illness and Injury: a practical guide. Elsevier Health Sciences 2008.

- Hamberg-van Reenen, H.; Ariëns, G.; Blatter, B.; Twisk, J.; Van Mechelen, W.; Bongers, P. Physical capacity in relation to low back, neck, or shoulder pain in a working population. Occupational and environmental medicine 2006, 63, 371-377.

- Safran, M.; Zachazewski, J.E.; Stone, D.A. Instructions for Sports Medicine Patients E-Book. 2nd edition, Elsevier Health Sciences, United Kingdom 2011.

- Straker, L.M. A review of research on techniques for lifting low-lying objects: 2. Evidence for a correct technique. Work 2003, 20, 83-96.

- Lewit, K. Manipulative therapy: Musculoskeletal medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences 2009.

- Bendix, T.; Eid, S. The distance between the load and the body with three bi-manual lifting techniques. Applied Ergonomics 1983, 14, 185-192. [CrossRef]

- Karahan, A.; Bayraktar, N. Determination of the usage of body mechanics in clinical settings and the occurrence of low back pain in nurses. International journal of nursing studies 2004, 41, 67-75. [CrossRef]

- Seidler, A.; Bolm-Audorff, U.; Siol, T.; Henkel, N.; Fuchs, C.; Schug, H.; Leheta, F.; Marquardt, G.; Schmitt, E.; Ulrich, P.T.; Beck, W.; Missalla, A.; Elsner, G. Occupational risk factors for symptomatic lumbar disc herniation; a case-control study. Occupational and environmental medicine 2003. 60, 821-830. [CrossRef]

- Drzał-Grabiec, J.; Snela, S.; Rachwał, M.; Podgórska, J.; Rykała, J. Effects of carrying a backpack in an asymmetrical manner on the asymmetries of the trunk and parameters defining lateral flexion of the spine. Human factors 2015, 57, 218-26. [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, K.H. Fitting the Human: Introduction to Ergonomics. CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group, Boca Raton 2008.

- Mackie, H.W.; Stevenson, J.M.; Reid, S.A.; Legg, S.J. The effect of simulated school load carriage configurations on shoulder strap tension forces and shoulder interface pressure. Applied Ergonomics 2005, 36,199-206. [CrossRef]

- Filaire, M.; Vacheron, J.J.; Vanneuville, G.; Poumarat, G. Influence of the mode of load carriage on the static posture of the pelvic girdle and the thoracic and lumbar spine in vivo. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 2001, 23, 27-31. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.; Woodhull-Mcneal, A.P. Postural adjustments while standing with two types of loaded backpack. Ergonomics 1987, 30,1425-1430. [CrossRef]

- Leilnahari, K.; Fatouraee, N.; Khodalotfi, M.; Sadeghein, M.A.; Kashani, Y.A. Spine alignment in men during lateral sleep position: experimental study and modeling. Biomedical Engineering Online 2011, 10, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Brame, C. 2013. Writing good multiple choice test questions. Retrieved from Vanderbuilt University Center for Teaching website: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-subpages/writing-good-multiple-choice-test-questions.

- Aghahi, R.H.; Darabi, R.; Hashemipour, M.A. Neck, back, and shoulder pains and ergonomic factors among dental students. Journal of education and health promotion 2018, 7, 40.

- Happell, B.; Stanton, R.; Hoey, W.; Scott, D. Knowing is not doing: The relationship between health behaviour knowledge and actual health behaviours in people with serious mental illness. Mental Health and Physical Activity 2014, 7, 198-204. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.H.; Bailey, J.E. Incentives and barriers to lifestyle interventions for people with severe mental illness: a narrative synthesis of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies. Journal of advanced nursing 2011, 67, 690-708. [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health education monographs 1974, 2, 354-386. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2002, 32, 665-683.

- Ryan, P. Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change: background and intervention development. Clinical nurse specialist CNS 2009, 23, 161-70.

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health education & behavior 2004, 31, 143-164. [CrossRef]

- Swain, C.T.; Pan, F.; Owen, P.J.; Schmidt, H.; Belavy, D.L. No consensus on causality of spine postures or physical exposure and low back pain: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Journal of Biomechanics 2020, 102, 109312. [CrossRef]

- Corlett, E.N. Background to sitting at work: research-based requirements for the design of work seats. Ergonomics 2006, 49, 1538-1546. [CrossRef]

- Nachemson, A.L. Disc pressure measurements. Spine 1981, 6, 93-97. [CrossRef]

- Beach, T.A.; Parkinson, R.J.; Stothart, J.P.; Callaghan, J.P. Effects of prolonged sitting on the passive flexion stiffness of the in vivo lumbar spine. The Spine Journal 2005, 5, 145-154. [CrossRef]

- Halonen, J.I.; Shiri, R.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Lallukka, T. Risk and Prognostic Factors of Low Back Pain: Repeated Population-based Cohort Study in Sweden. Spine 2019, 44, 1248-1255.

- Plamondon, A.; Gagnon, M.; Desjardins, P. Validation of a 3D segment model to estimate the net reaction forces and moments at the L5/S1 joint. Proceedings of the Canadian Society for Biomechanics VIIIth biennial conference 1994, 196.

- Kumar, S. Theories of musculoskeletal injury causation. Ergonomics 2001, 44, 17-47.

- Kim, D.; Cho, M.; Park, Y.; Yang, Y. Effect of an exercise program for posture correction on musculoskeletal pain. Journal of physical therapy science 2015, 27, 1791-1794. [CrossRef]

- Columb, M.; Atkinson, M. Statistical analysis: sample size and power estimations. Bja Education 2016,16, 159-161. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B. A focus on reliability in developmental research through Cronbach’s Alpha among medical, dental and paramedical professionals. Asian Pacific Journal of Health Sciences 2016, 3, 271-278.

| Variable | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age 18-23 years 24-29 years 30-34 years > 34 years Total |

10 24 7 14 55 |

18.2 43.6 12.7 25.5 100.0 |

|

Gender Male Female Total |

19 36 55 |

34.5 65.5 100.0 |

|

Course of study Dietetics Engineering Computer Science Project management Sports therapy and rehabilitation Interior Architecture and Design Energy Physiotherapy PhD Forensic Radiography Occupational therapy Global leadership and management Operating department practice Midwifery Nursing Low intensity psychological therapies Psychology Total |

6 5 5 1 1 3 1 1 4 1 1 1 3 2 18 1 1 55 |

10.9 9.1 9.1 1.8 1.8 5.5 1.8 1.8 7.3 1.8 1.8 1.8 5.5 3.6 32.7 1.8 1.8 100.0 |

|

Year of study Year 1 year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Postgraduate Total |

22 18 8 5 2 55 |

40.0 32.7 14.5 9.1 3.6 100.0 |

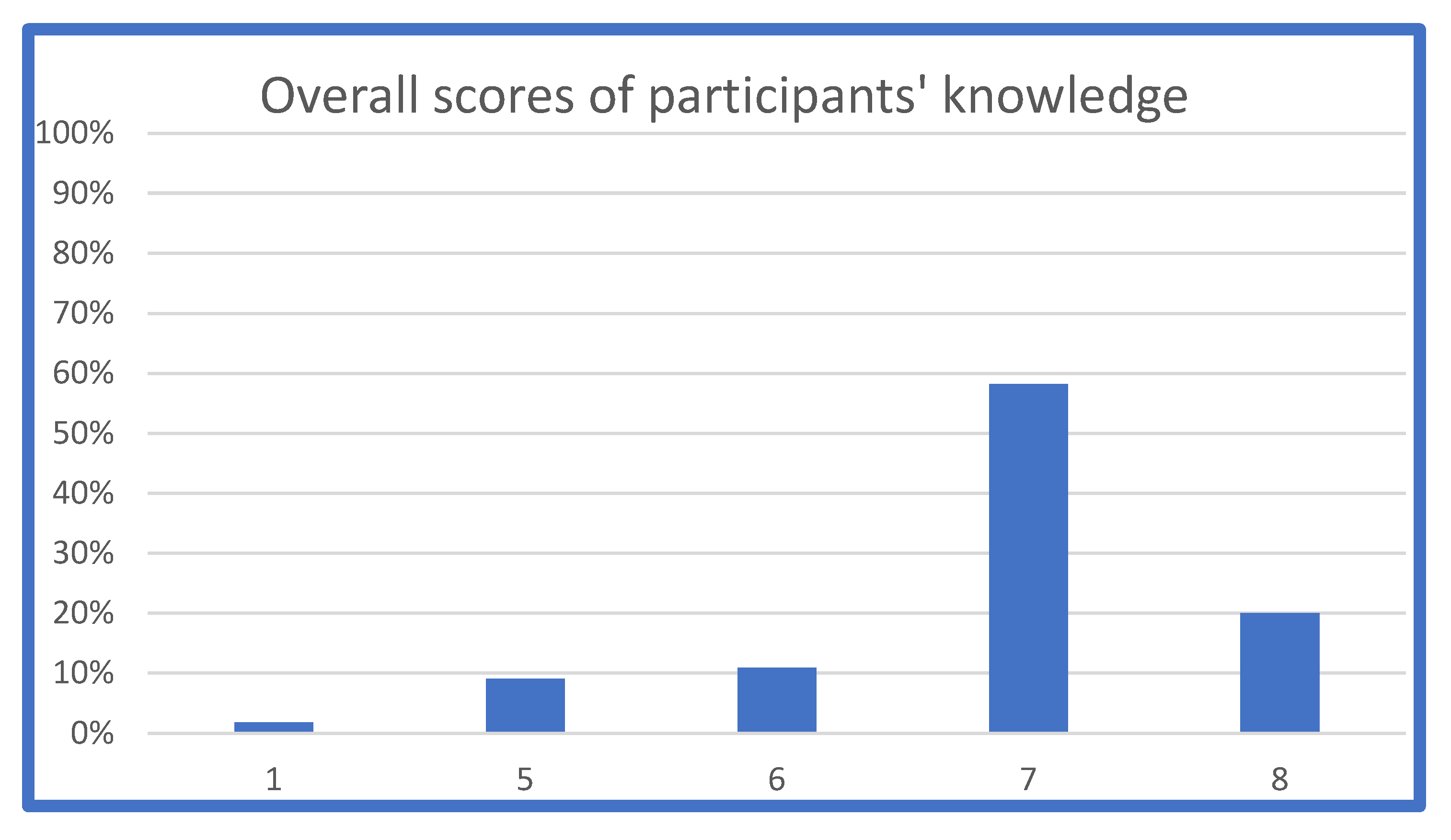

| Overall Scores of Knowledge | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Poor knowledge |

1 | 1.8 |

| Fair knowledge |

11 | 20.0 |

| Good knowledge | 43 | 78.2 |

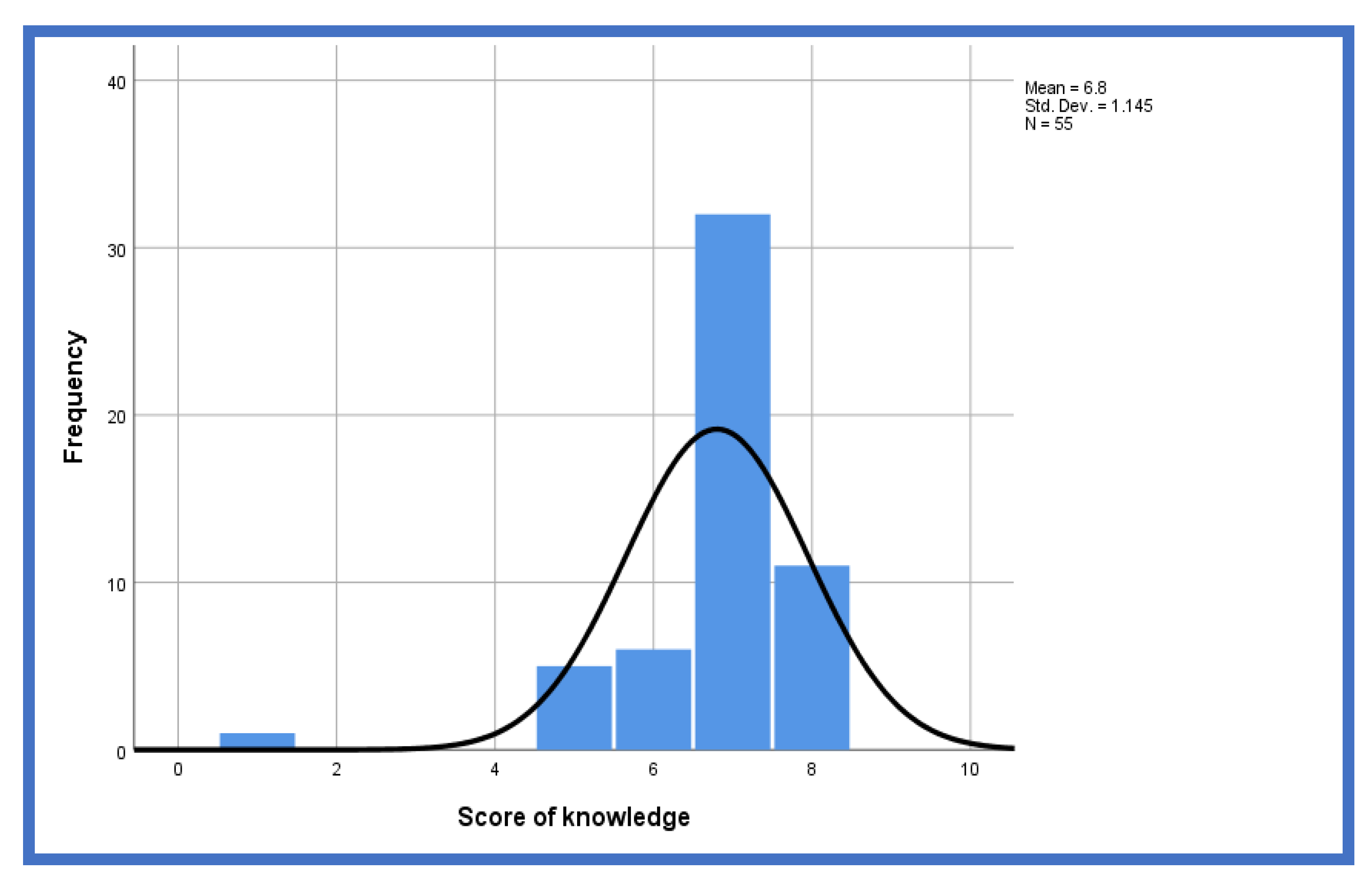

| N | Mean | SD. | Min. | Max. | Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge score | 55 | 6.80 | 1.145 | 1 | 8 | 0.351 | 0.00 |

| *SD=standard deviation; Min=minimum bound of confidence interval; Max=maximum bound of confidence interval | |||||||

| Variables | N | Mean Rank | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age 18-23 24-29 30-34 >34 |

10 24 7 14 |

28.50 26.40 21.86 33.46 |

0.30 |

|

Gender Male Female |

19 36 |

25.71 29.21 |

0.39 |

|

Course of study Dietetics Forensic Radiography Occupational therapy Global leadership and management Operating department practice Midwifery Nursing Low intensity psychological therapies Psychology Engineering Computer Science Project management Sports therapy and rehabilitation Interior Architecture and Design Energy Physiotherapy phD |

6 1 1 1 3 2 18 1 1 5 5 1 1 3 1 1 4 |

32.50 50.00 50.00 28.50 28.50 28.50 26.67 28.50 1.00 37.10 29.00 4.00 28.50 12.17 4.00 28.50 33.13 |

0.18 |

|

Academic year year 1 year 2 year 3 year 4 postgraduate |

22 18 8 5 2 |

30.80 23.33 31.13 23.00 39.25 |

0.29 |

|

School Health Non health |

33 17 |

27.32 21.97 |

0.16 |

|

MSP Yes No |

39 16 |

27.27 29.78 |

0.55 |

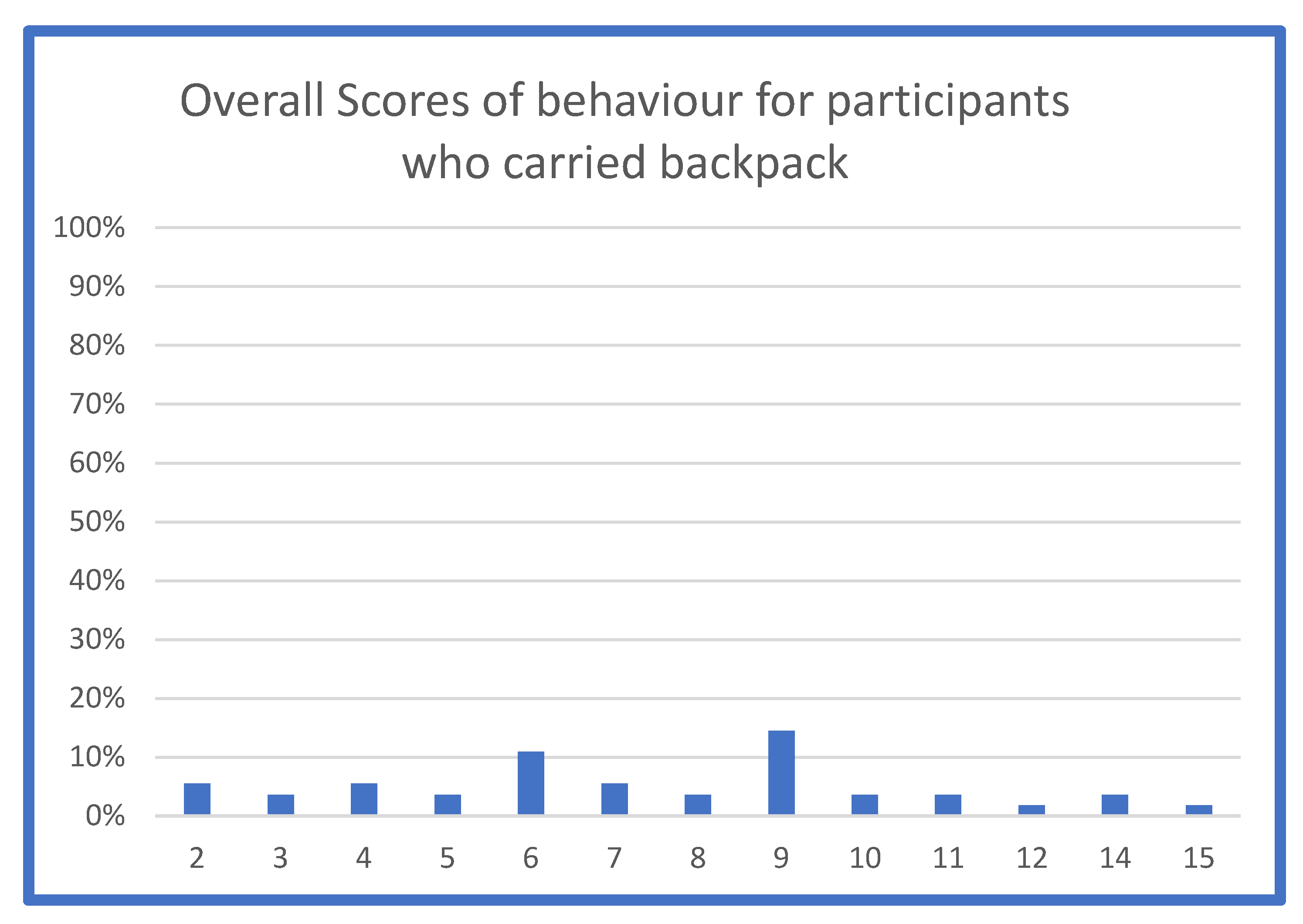

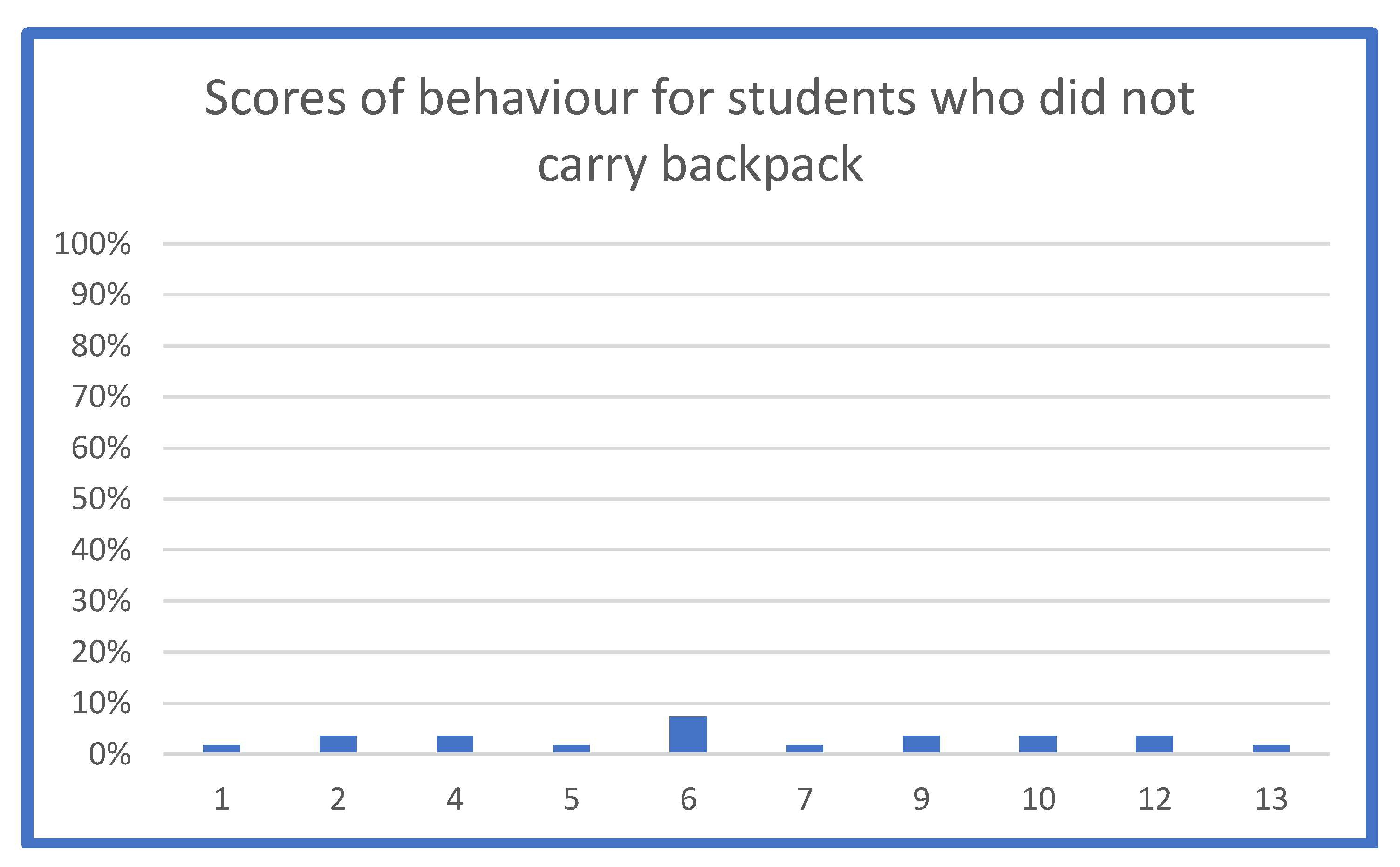

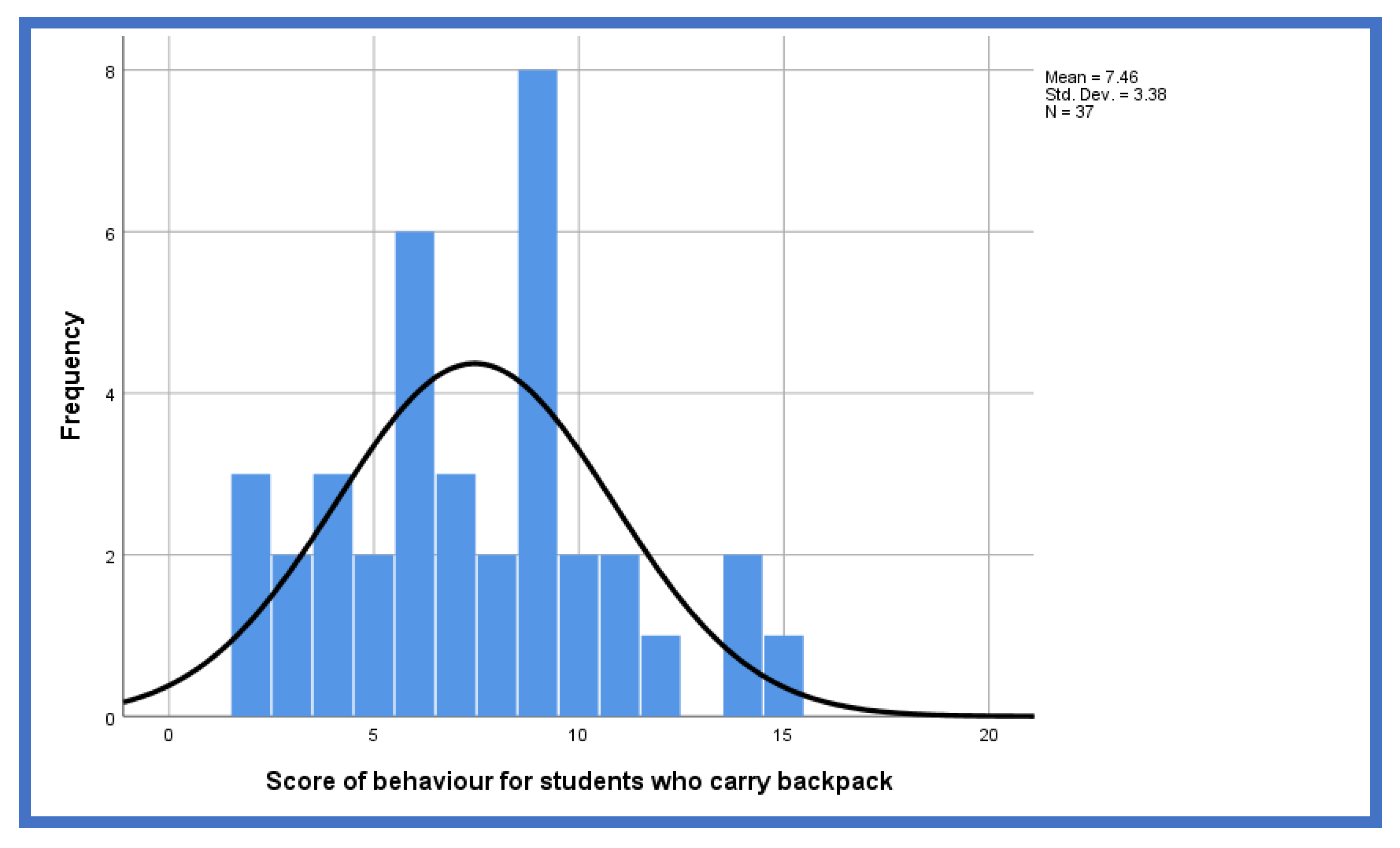

| Behaviour of Participants Who Carried Backpack | Behaviour of Participants Who Did Not Carry Backpack | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | |

| Poor | 19 | 51.4 | 10 | 55.6 |

| Fair | 14 | 37.8 | 5 | 27.8 |

| Good | 4 | 10.8 | 3 | 16.6 |

| Total | 37 | 100 | 18 | 100 |

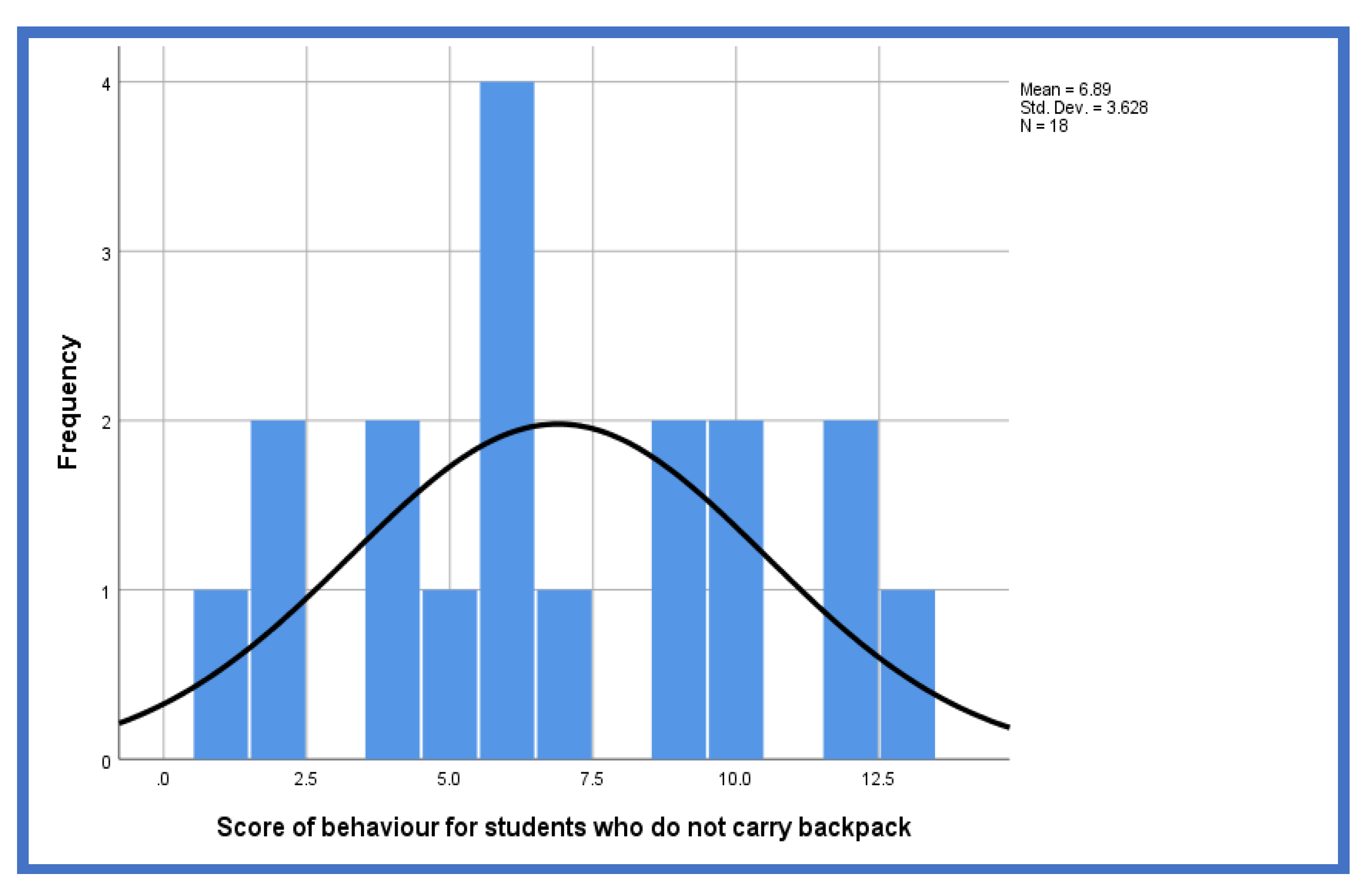

| Measures of Location | Goodness of Fit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Kolmogorov –Smirnov Z | P value | ||

| Behaviour scores (participants who carried backpack) | 37 | 7.46 | 3.380 | 2 | 15 | 0.108 | 0.20 | |

| Behaviour scores (participants who did not carry backpack) |

18 |

6.89 |

3.628 |

1 |

13 |

0.152 |

0.20 |

|

| Postural Behaviour | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students Who Carried Backpack Students Who Did Not Carry Backpack | ||||||

| F | DF | P-VALUE | F | DF | P-VALUE | |

| AGE | 1.495 | 3 | 0.23 | 0.964 | 3 | 0.45 |

| GENDER | 0.164 | 1 | 0.69 | 6.045 | 1 | 0.30 |

| COURSE | 1.606 | 12 | 0.16 | 3.701 | 9 | 0.60 |

| YEAR | 0.728 | 4 | 0.58 | 2.307 | 4 | 0.11 |

| SCHOOL | 0.340 | 1 | 0.56 | 4.125 | 1 | 0.62 |

| MSP | 6.251 | 1 | 0.20 | 0.899 | 1 | 0.36 |

| Age |

Gender | Course of Study | Academic Year | School | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MSP presence |

2.275 (.52) |

2.383 (.12) |

14.467 (.56) |

2.884 (.58) |

3.569 (.06) |

| *χ2 stands for Chi square value; (p-value) | |||||

| Age |

Gender | Course of Study | Year of Study | School | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Neck and shoulder pain Upper back pain Lower back pain Other pain (hips, knees and ankles) |

4.397 (.22) 3.064 (.38) 5.973 (.11) 14.232 (.35) |

0.3222 (.57) 0.711 (.39) 2.867 (.09) 1.095 (.29) |

17.535 (.35) 21.618 (.16) 13.032 (.67) 9.023 (.91) |

4.897 (.29) 1.819 (.77) 3.046 (.55) 4.266 (.37) |

1.092 (.30) 0.778 (.38) 2.911 (.09) 1.073 (.30) |

| Chi square values; (p-values) | |||||

| Neck and Shoulder Pain | Upper Back Pain | Lower Back Pain | Other Pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sleeping |

4.019 (.05) |

1.318 (.25) |

2.731 (.09) |

0.406 (.52) |

|

Lifting objects |

2.340 (.13) | 1.913 (.17) | 4.236 (.04)* | 0.353 (.56) |

|

Sitting |

2.973 (.09) | 3.524 (.06) | 4.093 (.04)* | 1.010 (.32) |

|

Standing |

0.764 (.38) | 0.010 (.92) | 7.323 (.01)* | 0.461 (.49) |

| Carrying weight | 1.234 (.27) | 2.593 (.11) | 2.721 (.09) | 0.642 (.42) |

|

Computer use |

6.136 (.01)* |

5.269 (.02)* |

2.441 (.06) |

1.384 (.24) |

|

Walking |

2.005 (.16) | 0.094 (.78) | 2.890 (.09) | 2.596 (.11) |

| Other activities | 1.078 (.29) | 0.528 (.47) | 1.952 (.16) | 5.619 (.50) |

| Chi square values; p-values | ||||

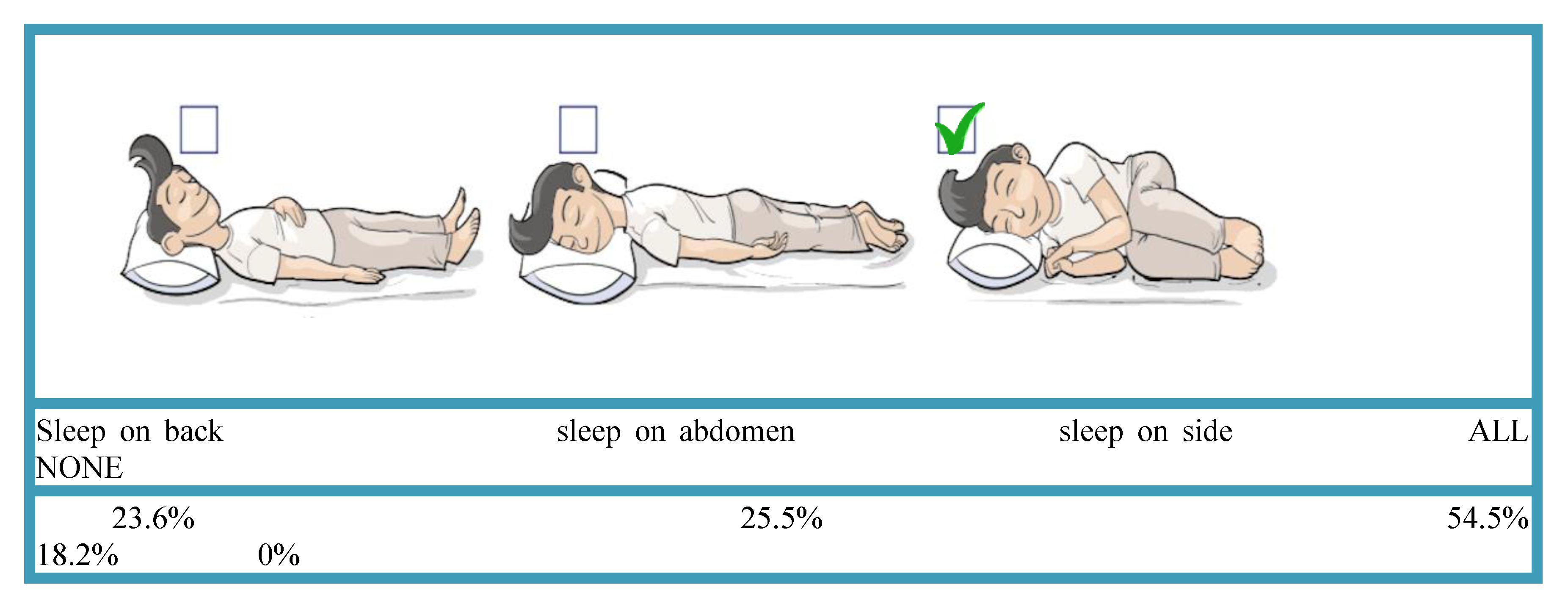

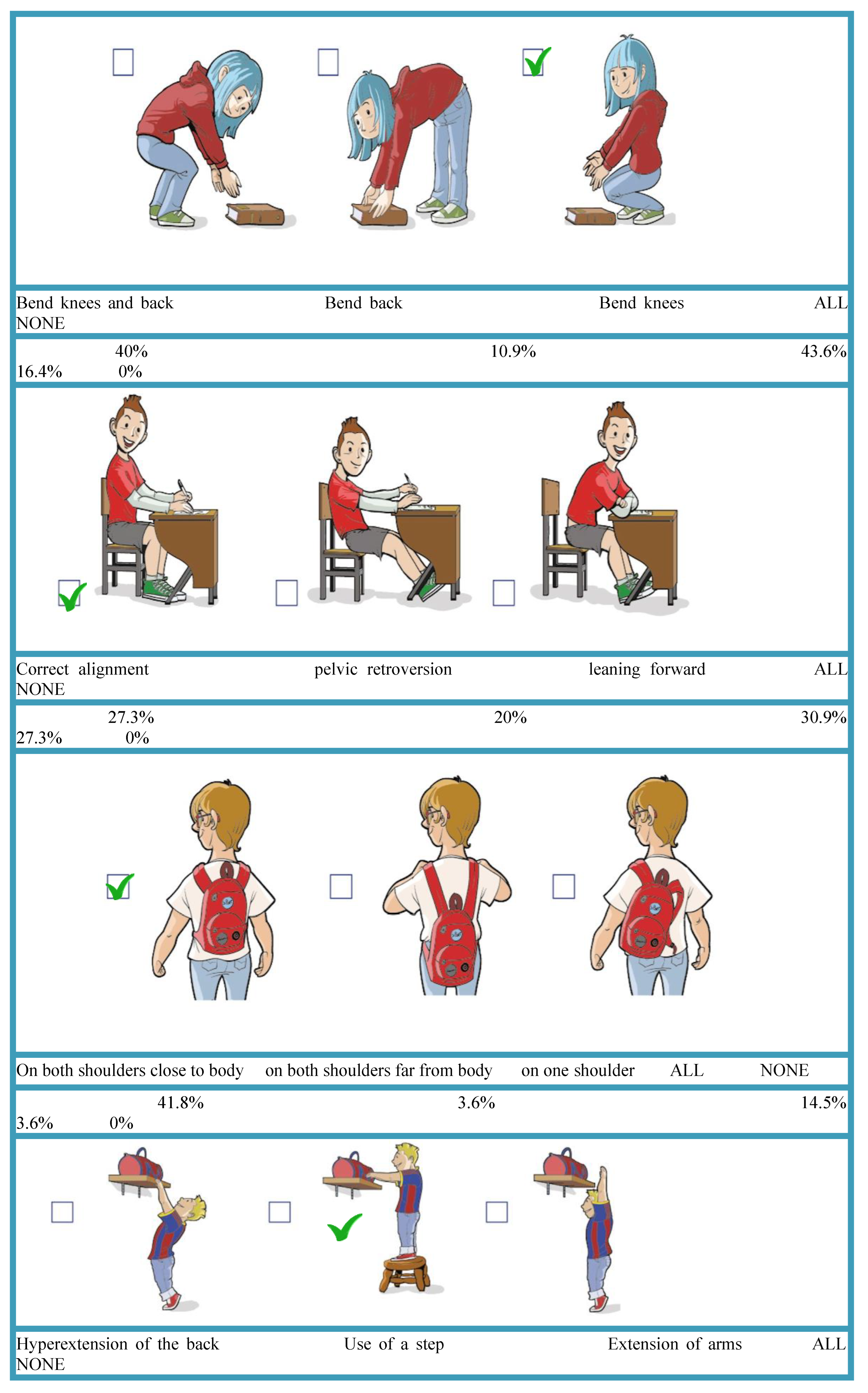

| Questions | Themes and Categories | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

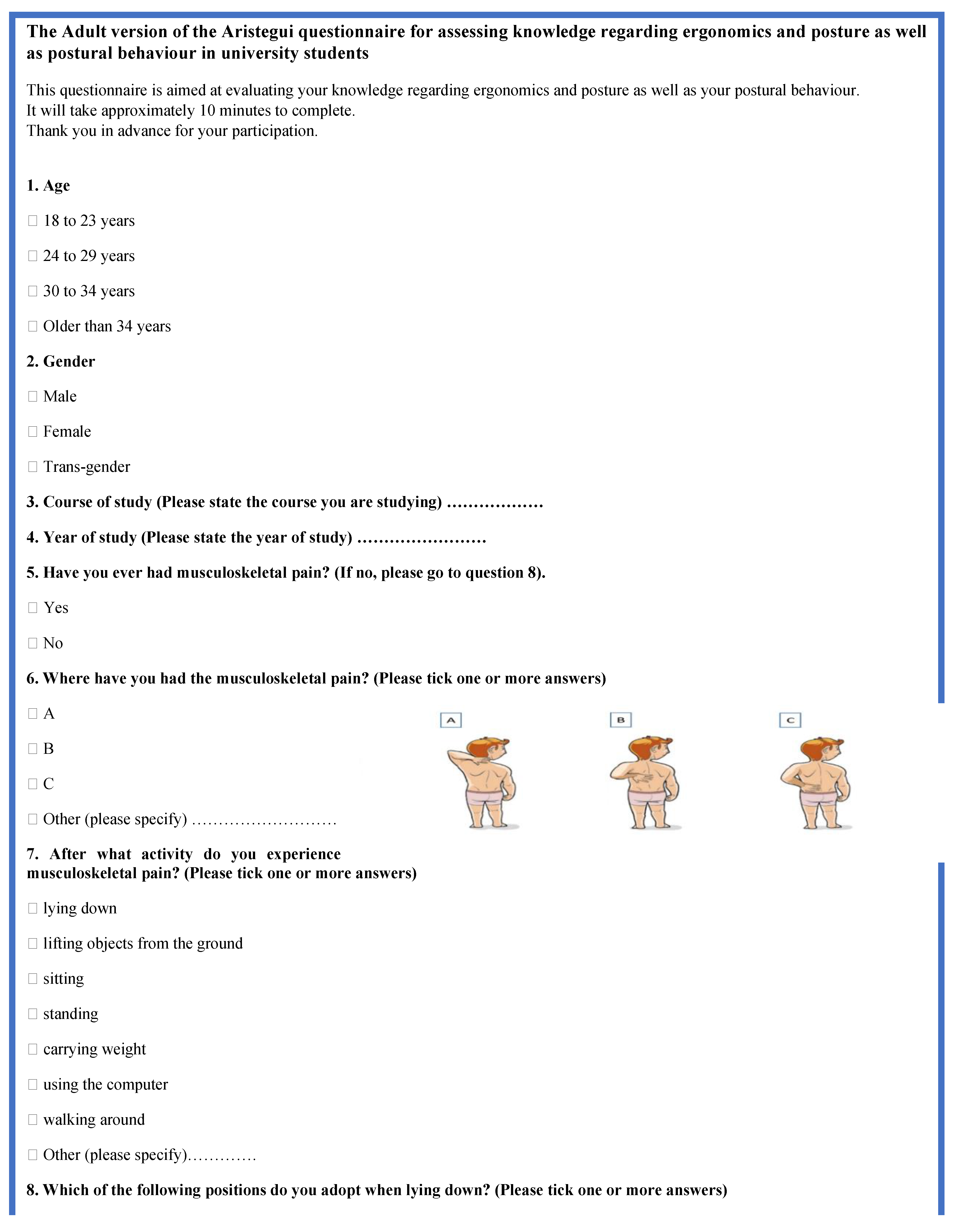

| Qs10. What is the reason for your choice of the most adequate sleeping posture? |

Comfortable position recovery position relaxed posture foetal posture Correct spinal alignment spine is straight correct alignment Less pain and injuries Less pressure on spine Equal distribution of body weight |

10.9% 25.5% 1.8% 12.7% 12.7% 5.5% 3.6% |

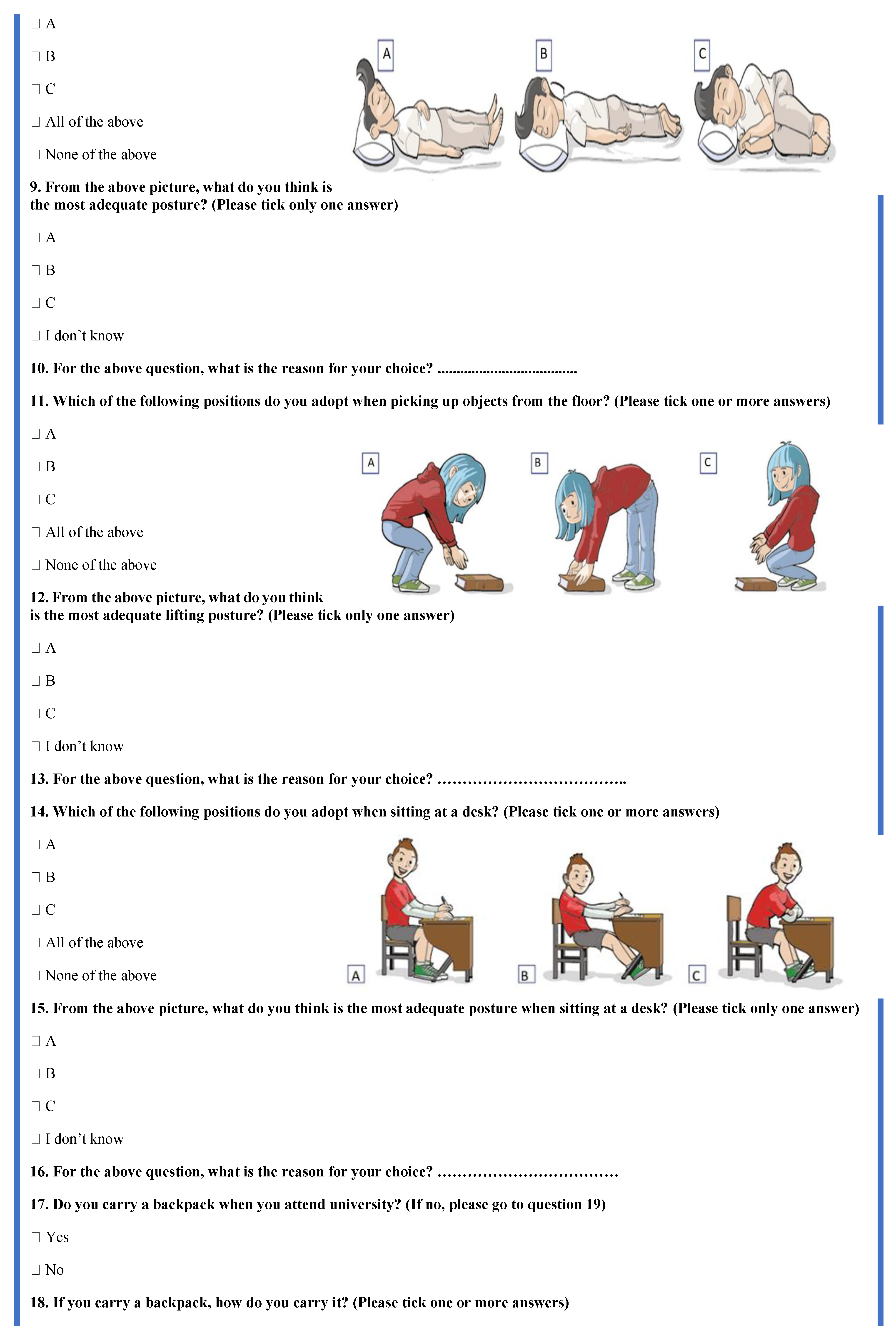

| Qs13. What is the reason for your choice of the most adequate posture when picking up objects from the ground? |

Use knees not back Bend knees Use legs Keep back straight Keep objects close to body Load is close to the body Less pain and injuries Prevent pain and injuries Less pressure on spine Even distribution of weight |

10.9% 14.5% 32.7% 1.8% 3.6% 20% 21.8% |

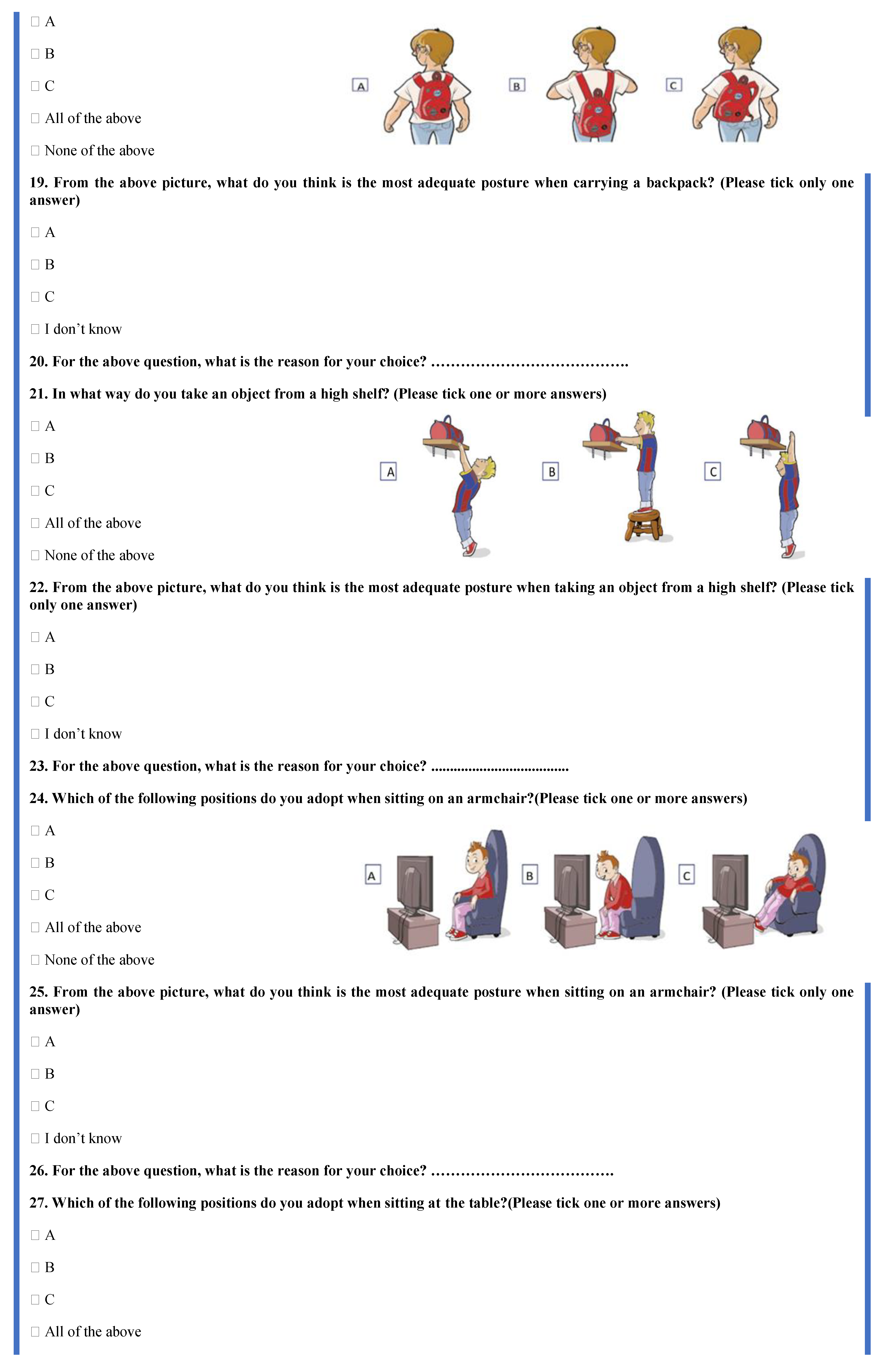

| Qs16.What is the reason for your choice of the most adequate posture when sitting at a desk |

Comfortable posture Comfortable Good posture Correct spine alignment Straight back Spine support Back support Less pain and injuries avoid pain Hands on desk Elbows rest on desk Feet flat on floor Feet on floor |

7.3% 29.1% 36.4% 5.5% 18.2% 1.8% 1.8% |

| Qs23. What is the reason for your choice of the most adequate posture when taking an object from a high shelf? |

Less pain and injuries Less pain Spine alignment Spine is straight |

51% 33% |

| Qs26. What is the reason for your choice of the most adequate posture when sitting on an armchair |

Comfortable posture Comfortable Better posture Correct spine alignment Straight back Spine alignment Spine support Back support Less pain and injuries Avoid pain Less pressure and strain Better for joints |

10.9% 31% 40% 1.8% 10.9% 1.8% 9.1% 1.8% |

| Qs 29. What is the reason for your choice of the most adequate posture when sitting at a table |

Comfortable posture Better posture comfortable Spine support Straight back Back support Good for back Less pain and injuries Less pressure and strain Prevent pain Good for joints Equal distribution of body weight |

21.8% 5.5% 43.6% 16.4% 1.8% 5.5% 1.8% 1.8% 1.8% |

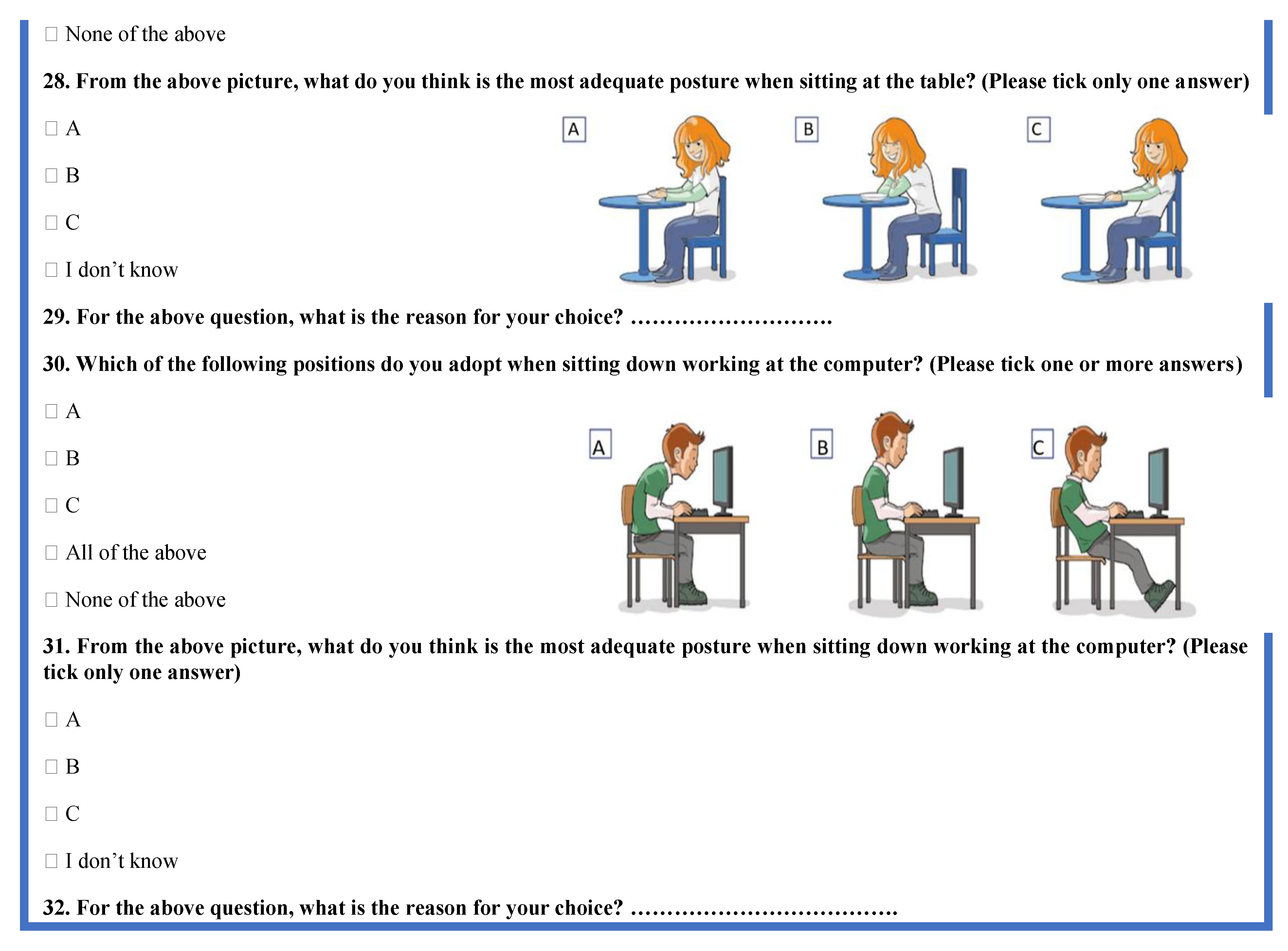

| Qs32. What is the reason for your choice of the most adequate posture when sitting down working at computer |

Comfortable posture Comfortable Good posture Correct spine alignment Back straight Spine alignment Spine support Back support Less pain and injuries Avoid pain Hands on desk Elbows rest on desk Feet flat on floor Feet on floor Screen at eye level Eyes at same level with screen |

5.5% 25.5% 31% 1.8% 12.7% 9.1% 3.6% 3.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).