Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

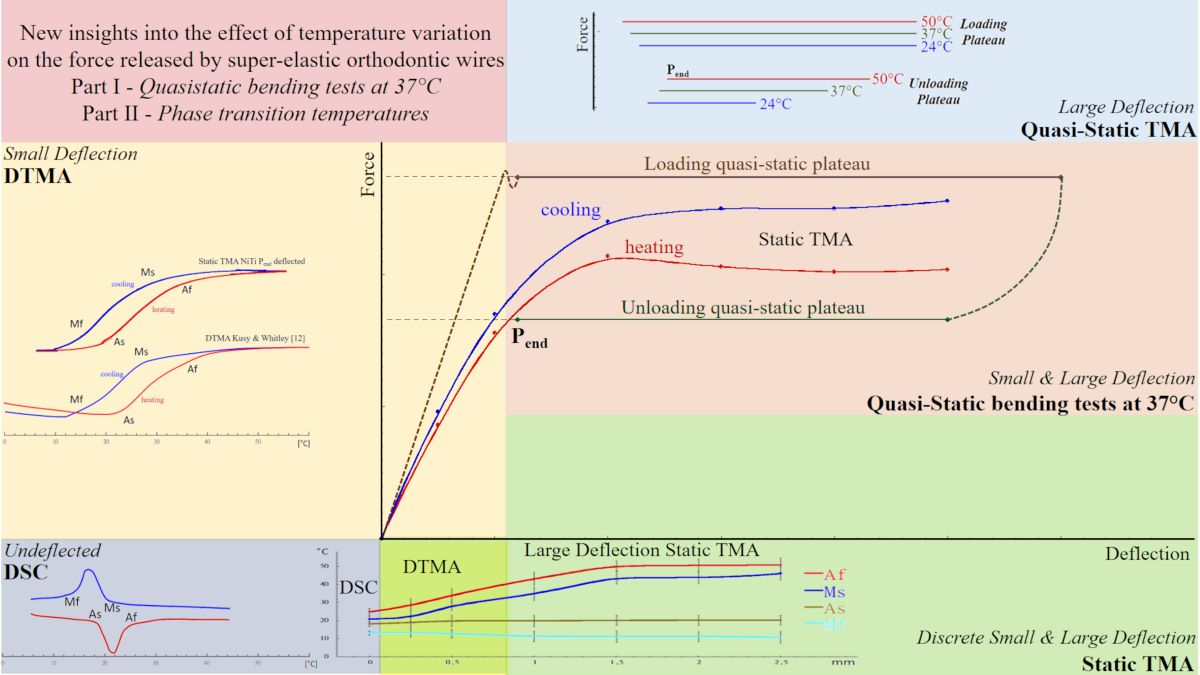

1. Introduction

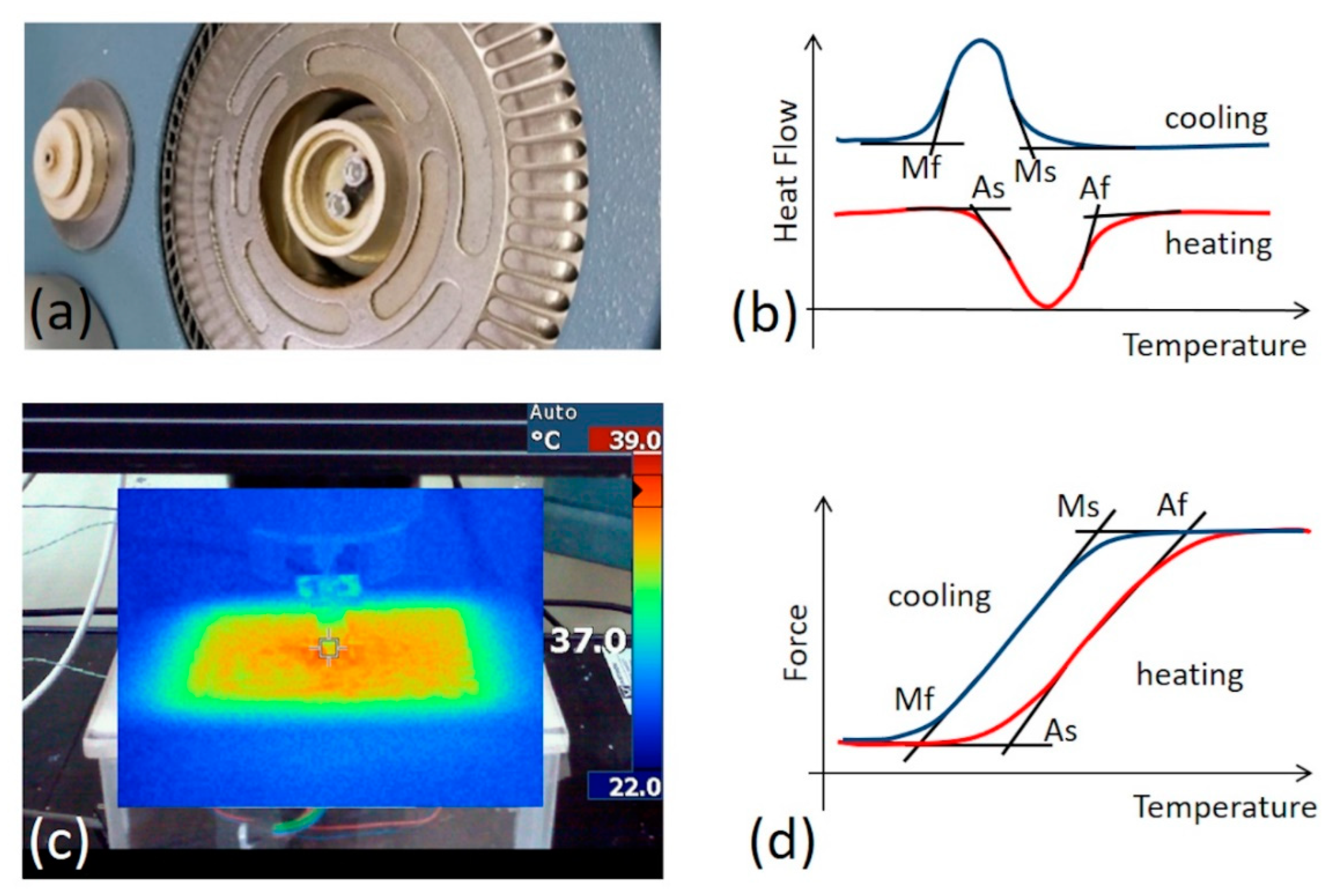

2. Materials and Methods

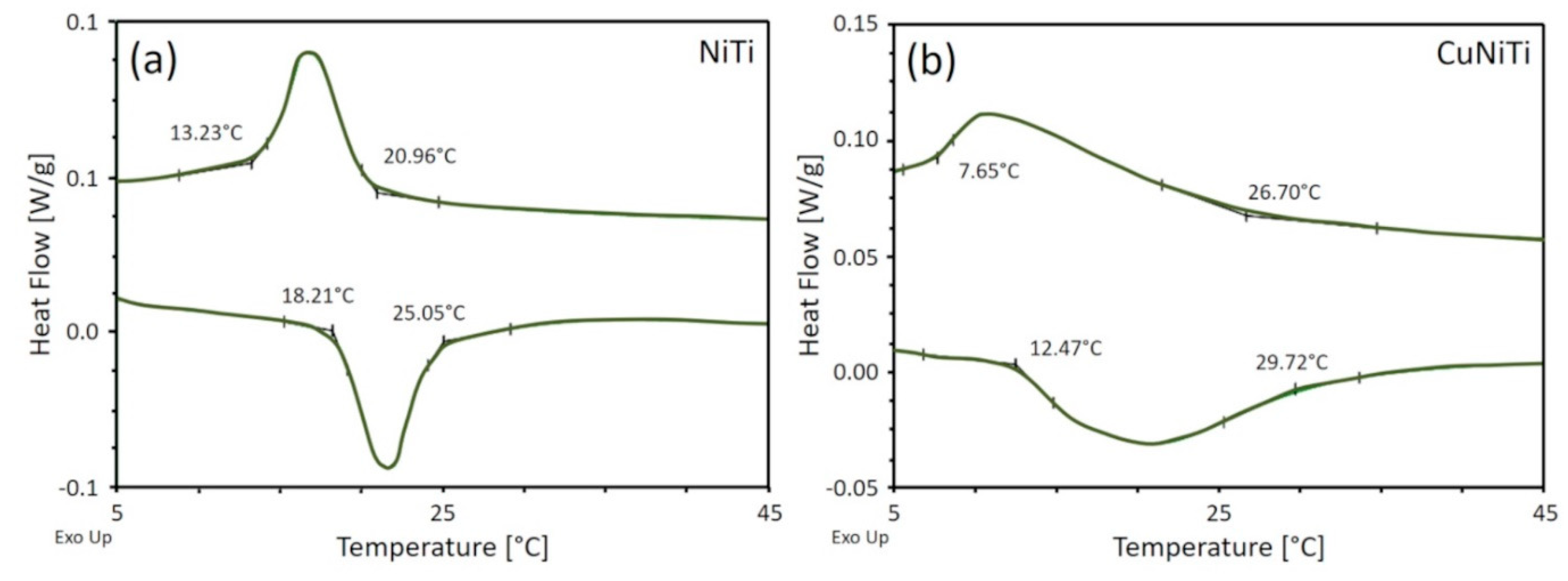

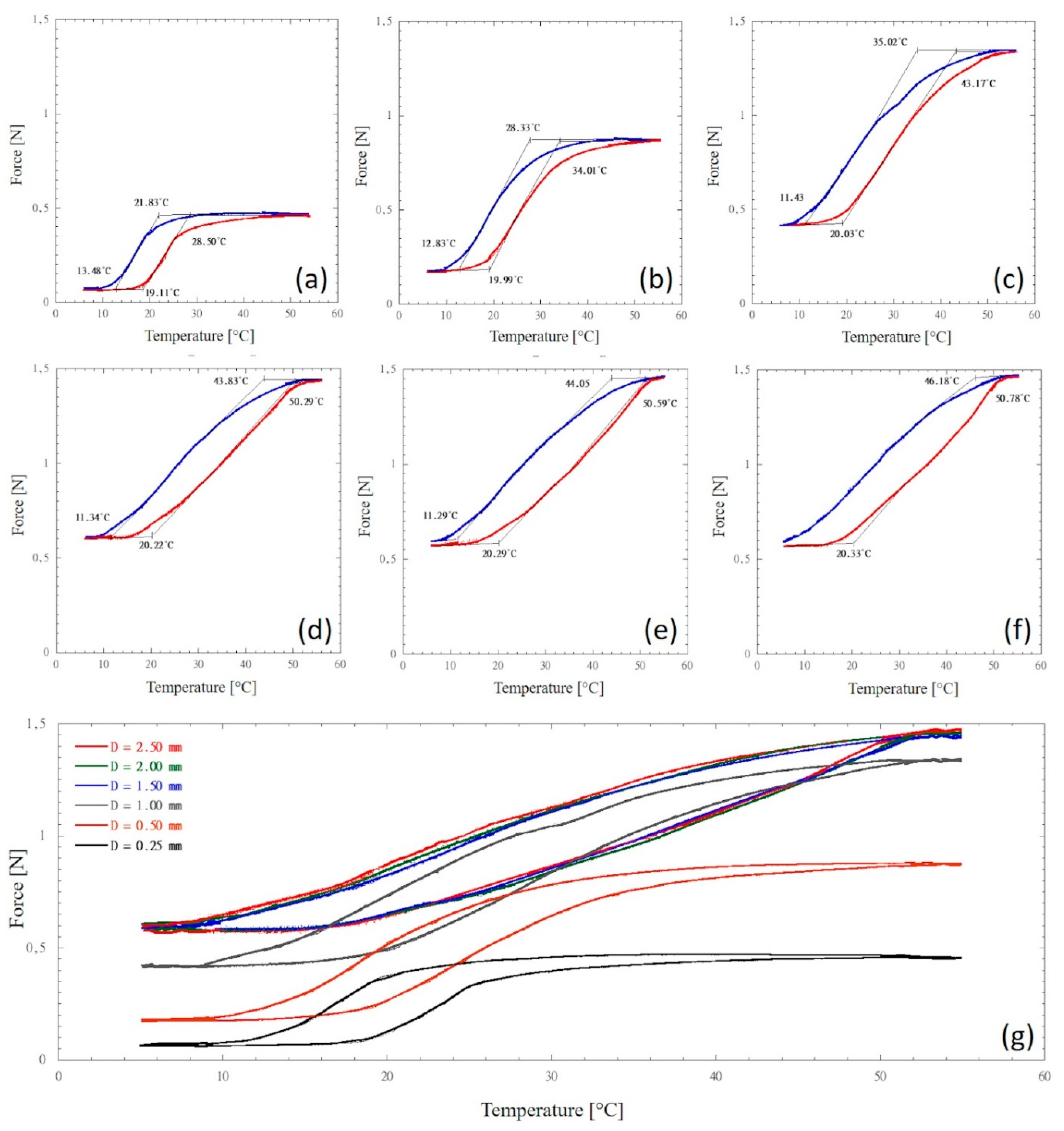

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Phase Transition Temperatures of Unstressed NiTi and CuNiTi Archwires

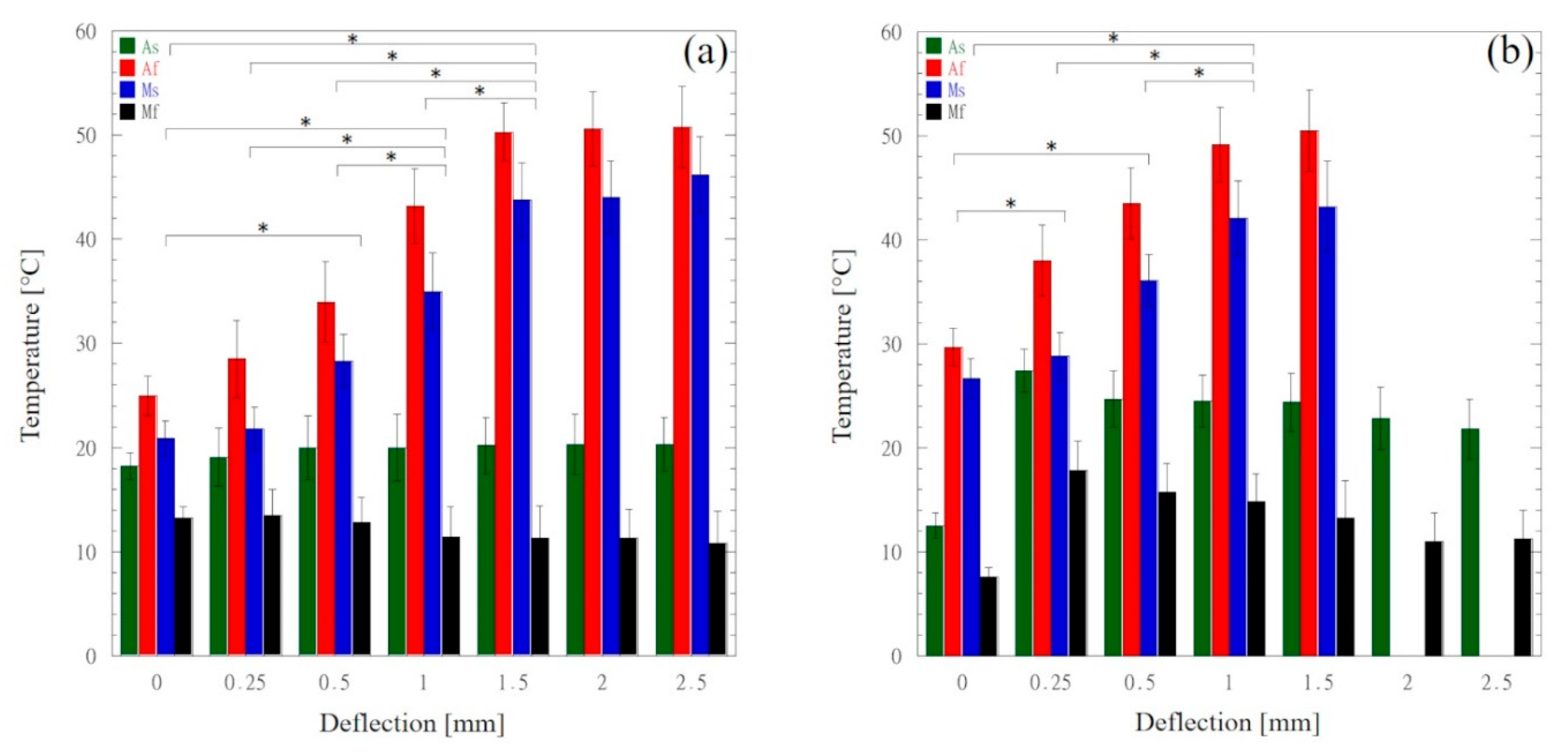

4.2. Effect of the Deflection Level on Af and Ms Temperatures

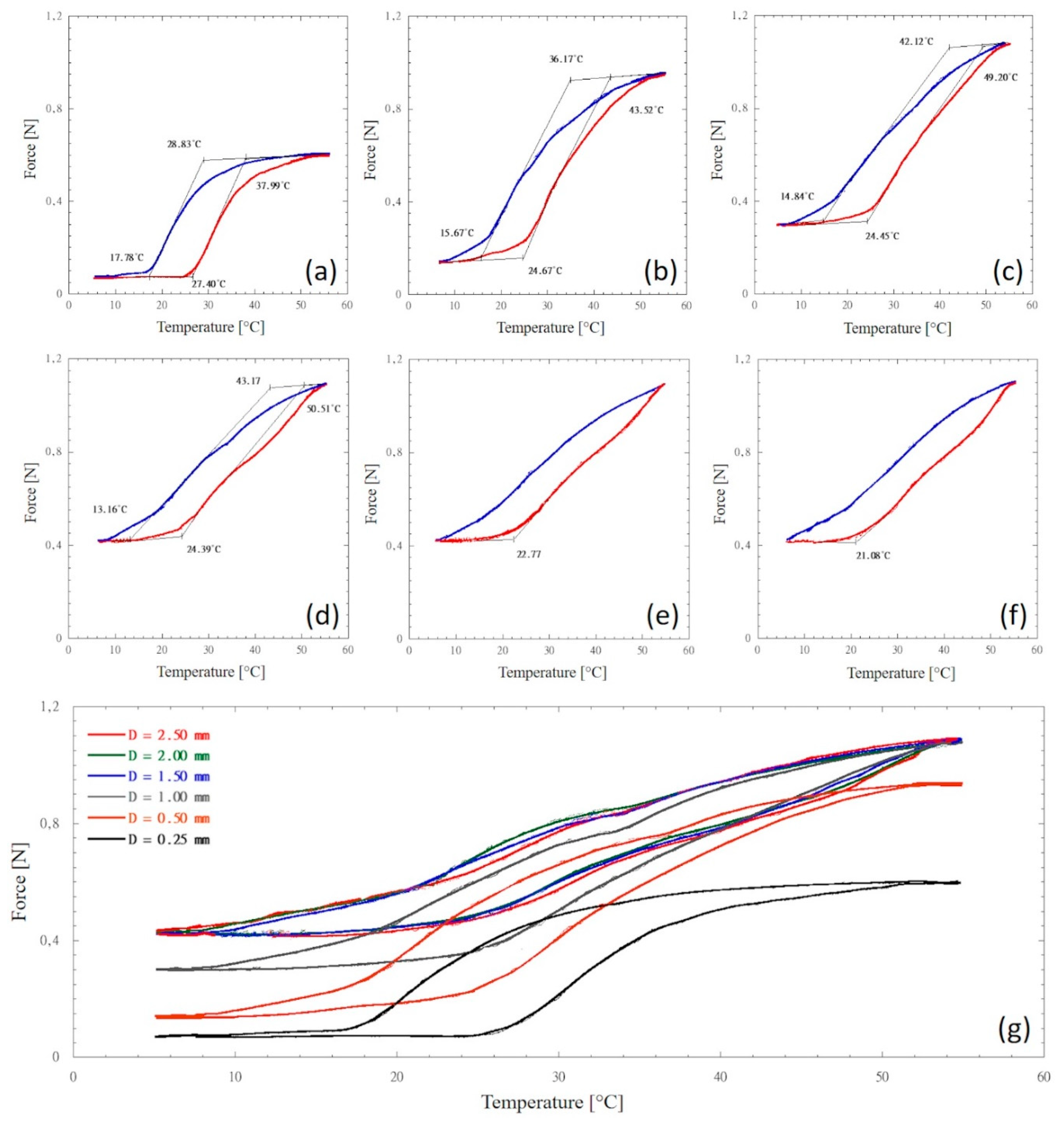

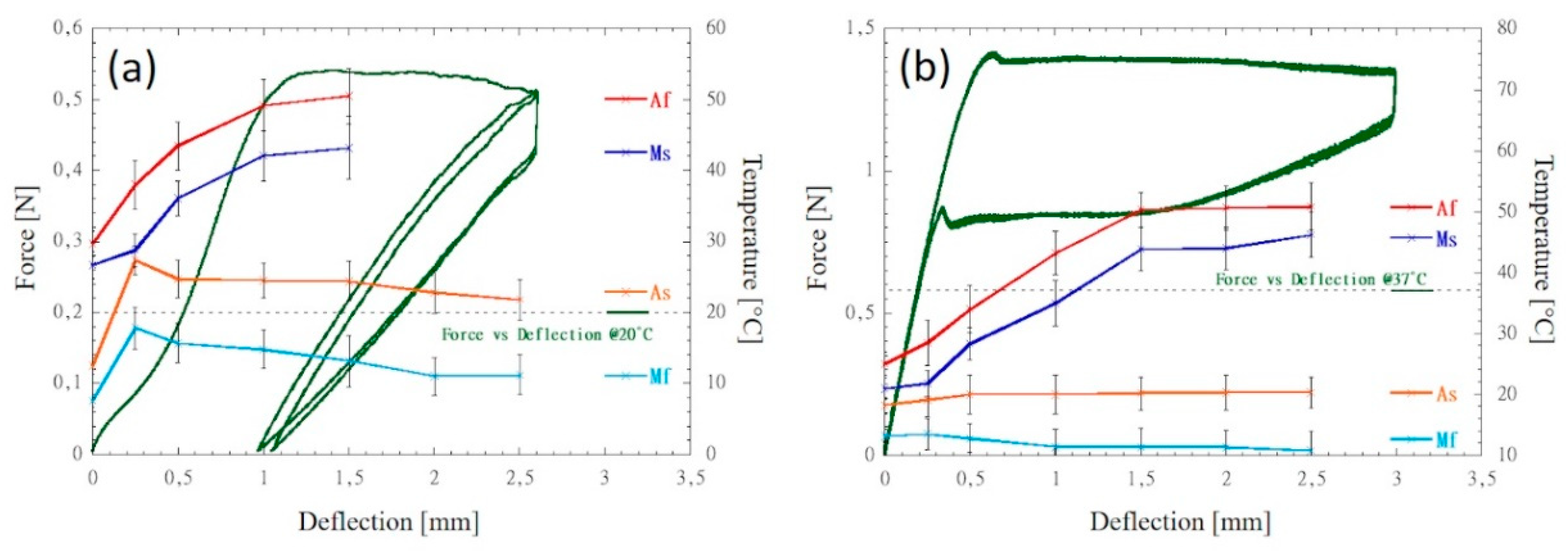

4.3. Effect of Temperature on the Force Released by NiTi and CuNiTi Wires

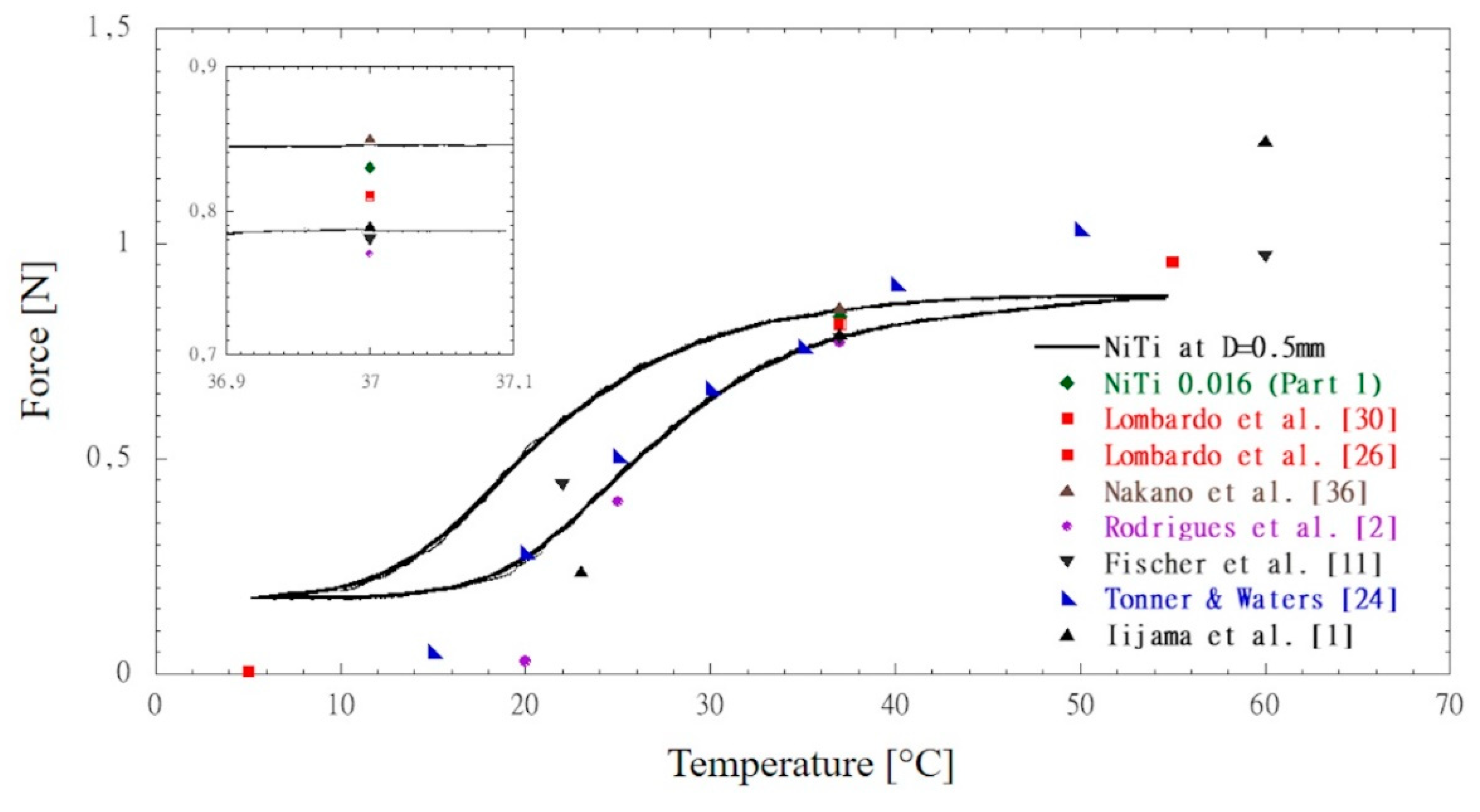

4.4. Clinical Outcames and the Effect of Oral Temperature Variation on NiTi and CuNiTi Orthodontic Wires

5. Conclusions

- -

- The proposed static TMA approach encompasses a simple, comprehensive and reproducible setup expected to aid in the future optimization of orthodontic treatments.

- -

- By using static TMA, the force released by superelastic wires and transition temperatures are straightforward addressed.

- -

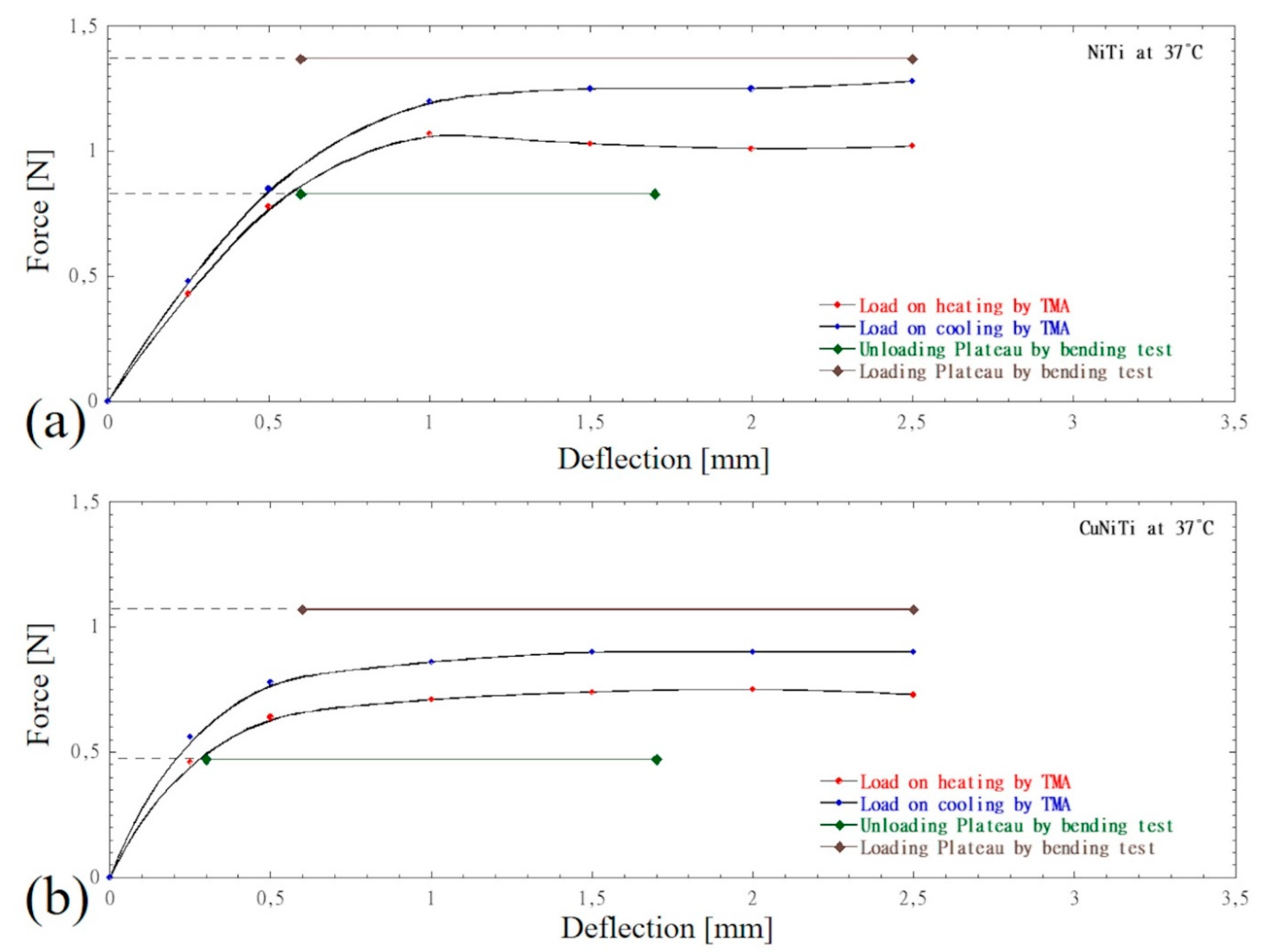

- The plateau force levels at 37°C only represent the lower boundary force that a superelastic wire releases at 37°C.

- -

- For both NiTi and CuNiTi, plateau force levels at 37°C can be predicted by the static TMA profile matching the end point of the force plateau extension.

- -

- Once the wire is applied, and its structure stabilizes, the released force depends on both deflection and temperature levels.

- -

- The released force increases by increasing the deflection level only up to a certain limit of deflection, above this limit, the force is independent of the deflection amount.

- -

- The austenitic finish (Af) and martensitic start (Ms) temperatures steeply increase as the deflection level increases.

- -

- Temporary heating or cooling returns a wire’s structure more plentiful of austenitic phase or martensitic phase, respectively. Thus affecting the magnitude of the force released by the wire.

- -

- At fixed deflection and temperature levels, the released force may span between two extremes according to the type and magnitude of the temporary thermal event. The higher the relative difference between the fixed temperature level and the transition temperatures (Mf<As<T<Ms<Af), the higher will be the extension of the range over which the force may span.

- -

- At deflection levels lower than 1.0 mm, the force released by CuNiTi wires spans over a range wider than that of the NiTi wire. The opposite occurs for deflection levels higher than 1.5 mm.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iijima, M.; Ohno, H.; Kawashima, I.; Endo, K.; Mizoguchi, I. Mechanical Behavior at Different Temperatures and Stresses for Superelastic Nickel–Titanium Orthodontic Wires Having Different Transformation Temperatures. Dental Materials 2002, 18, 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P. F. ; Fernandes, F. B. ; Magalhães, R. ; Camacho, E. ; Lopes, A. ; Paula, A. S. ; Basu R. ; Schell, N. Thermo-mechanical characterization of NiTi orthodontic archwires with graded actuating forces. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials 2020, 107, 103747.

- Stoyanova-Ivanova, A.; Georgieva, M.; Petrov, V.; Andreeva, L.; Petkov, A.; Georgiev, V. Effects of Clinical Use on the Mechanical Properties of Bio-Active®(BA) and TriTanium®(TR) Multiforce Nickel-Titanium Orthodontic Archwires. Materials 2023, 16(2), 483. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J. Thermomechanical Aspects of NiTi. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 1995, 43, 1243–1281. [CrossRef]

- Longman, C.M.; Pearson, G.J. Variations in tooth, surface temperature in the oral cavity during fluid intake. Biomaterials. 1987 Sep 1;8(5):411-4.

- Airoldi, G.; Riva, G.; Vanelli, M.; Garattini, G. Oral environment temperature changes induced by cold/hot liquid intake. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 1997, 112.1: 58-63.

- Moore, R. Intra-Oral Temperature Variation over 24 Hours. The European Journal of Orthodontics 1999, 21, 249–261. [CrossRef]

- Laino, G.; De Santis, R.; Gloria, A.; Russo, T.; Quintanilla, D.S.; Laino, A.; Martina, R.; Nicolais, L.; Ambrosio, L. Calorimetric and Thermomechanical Properties of Titanium-Based Orthodontic Wires: DSC-DMA Relationship to Predict the Elastic Modulus. J Biomater Appl 2012, 26, 829–844. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.E.; Waddell, J.N.; Lyons, K.M.; Kieser, J.A. Intraoral pH and temperature during sleep with and without mouth breathing. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2016 May;43(5):356-63.

- Bradley, T.G.; Brantley, W.A.; Culbertson, B.M. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analyses of Superelastic and Nonsuperelastic Nickel-Titanium Orthodontic Wires. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996, 109, 589–597. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Brandies, H.; Es-Souni, M.; Kock, N.; Raetzke, K.; Bock, O. Transformation Behavior, Chemical Composition, Surface Topography and Bending Properties of Five Selected 0.016" x 0.022" NiTi Archwires. J Orofac Orthop 2003, 64, 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Kusy, R.P.; Whitley, J.Q. Thermal and mechanical characteristics of stainless steel, titanium-molybdenum, and nickel-titanium archwires. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics 2007, 131(2), 229-237.

- Nespoli, A.; Passaretti, F.; Szentmiklósi, L.; Maróti, B.; Placidi, E.; Cassetta, M.; Tian, K.V. Biomedical NiTi and β-Ti Alloys: From Composition, Microstructure and Thermo-Mechanics to Application. Metals 2022, 12(3), 406.

- Sakima, M.T.; Dalstra, M.; Melsen, B. How does temperature influence the properties of rectangular nickel–titanium wires?. The European Journal of Orthodontics 2006, 28(3), 282-291.

- Miyazaki, S.; Otsuka, K.; Suzuki, Y. Transformation pseudoelasticity and deformation behavior in a Ti-50.6 at% Ni alloy. Scripta Metallurgica 1981, 15(3), 287-292.

- Kusy, R.P.; Wilson, T.W. Dynamic mechanical properties of straight titanium alloy arch wires. Dental Materials 1990, 6(4), 228-236.

- Lahoz, R.; Puértolas, J.A. Training and two-way shape memory in NiTi alloys: influence on thermal parameters. Journal of alloys and compounds 2004, 381(1-2), 130-136.

- Florian, G.; Gabor, A.R.; Nicolae, C.A.; Rotaru, A.; Marinescu, C.A.; Iacobescu, G.; Rotaru, P. Physical and thermophysical properties of a commercial Ni–Ti shape memory alloy strip. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2019, 138, 2103-2122.

- Silva, P.C.; Grassi, E.N.; Araújo, C.J.; Delgado, J.M.; Lima, A.G. NiTi SMA Superelastic Micro Cables: Thermomechanical Behavior and Fatigue Life under Dynamic Loadings. Sensors 2022, 22(20), 8045.

- Santoro, M.; Beshers, D.N. Nickel-titanium alloys: stress-related temperature transitional range. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2000, 118(6), 685-692.

- Deng, Z.; Huang, K.; Yin, H.; Sun, Q. Temperature-dependent mechanical properties and elastocaloric effects of multiphase nanocrystalline NiTi alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 938, 168547.

- Agarwal, N.; Ryan Murphy, J.; Hashemi, T.S.; Mossop, T.; O’Neill, D.; Power, J.; Brabazon, D. Effect of Heat Treatment Time and Temperature on the Microstructure and Shape Memory Properties of Nitinol Wires. Materials 2023, 16(19), 6480.

- Ronca, D.; Gloria, A.; De Santis, R.; Russo, T.; D’Amora, U.; Chierchia, M.; Ambrosio, L. Critical analysis on dynamic-mechanical performance of spongy bone: the effect of an acrylic cement. Hard Tissue 2014, 3(1), 9-16.

- Tonner, R.I.; Waters, N.E. The Characteristics of Super-Elastic Ni-Ti Wires in Three-Point Bending. Part I: The Effect of Temperature. Eur J Orthod 1994, 16, 409–419. [CrossRef]

- Yanaru, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kakigawa, H.; Kozono, Y. Temperature-and deflection-dependences of orthodontic force with Ni-Ti wires. Dental materials journal 2003, 22(2), 146-159.

- Lombardo, L.; Toni, G.; Stefanoni, F.; Mollica, F.; Guarneri, M. P.; Siciliani, G. The effect of temperature on the mechanical behavior of nickel-titanium orthodontic initial archwires. The Angle Orthodontist 2013, 83(2), 298-305.

- Sabbagh, H.; Janjic Rankovic, M.; Martin, D.; Mertmann, M.; Hötzel, L.; Wichelhaus, A. Load Deflection Characteristics of Orthodontic Gummetal® Wires in Comparison with Nickel–Titanium Wires: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2024, 17(2), 533. [CrossRef]

- Brauchli, L.M.; Keller, H.; Senn, C.; Wichelhaus, A. Influence of bending mode on the mechanical properties of nickel-titanium archwires and correlation to differential scanning calorimetry measurements. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2011, 139(5), e449-e454.

- Biermann, M.C.; Berzins, D.W.; Bradley, T.G. Thermal analysis of as-received and clinically retrieved copper-nickel-titanium orthodontic archwires. The Angle Orthodontist 2007, 77(3), 499-503.

- Lombardo, L.; Marafioti, M.; Stefanoni, F.; Mollica, F.; Siciliani, G. Load Deflection Characteristics and Force Level of Nickel Titanium Initial Archwires. Angle Orthod 2012, 82, 507–521. [CrossRef]

- Kusy, R.P. A Review of Contemporary Archwires: Their Properties and Characteristics. Angle Orthod 1997, 67, 197–207. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.; Arreghini, A.; Al Ardha, K.; Scuzzo, G.; Takemoto, K.; Siciliani, G. Wire Load-Deflection Characteristics Relative to Different Types of Brackets. Int Orthod 2011, 9, 120–139. [CrossRef]

- Bartzela, T.N.; Senn, C.; Wichelhaus, A. Load-Deflection Characteristics of Superelastic Nickel-Titanium Wires. Angle Orthod 2007, 77, 991–998. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P. D.; Dysart, P. S.; Hood, J. A.; Herbison, G. P. Load-deflection characteristics of superelastic nickel-titanium orthodontic wires. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics 2002, 121(5), 483-495.

- Nucera, R.; Gatto, E.; Borsellino, C.; Aceto, P.; Fabiano, F.; Matarese, G.; Cordasco, G. Influence of bracket-slot design on the forces released by superelastic nickel-titanium alignment wires in different deflection configurations. The Angle Orthodontist 2014, 84(3), 541-547.

- Nakano, H.; Satoh, K.; Norris, R.; Jin, T.; Kamegai, T.; Ishikawa, F.; Katsura, H. Mechanical Properties of Several Nickel-Titanium Alloy Wires in Three-Point Bending Tests. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1999, 115, 390–395. [CrossRef]

| Tooth location | Mean temperature | Temperature range | Speech/breath temperature range | Peak temperature after cold drink | Peak temperature after hot drink | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Front | 33.1 | 29.9-36.8 | 68 | 5 | ||

| Upper Posterior | 34.6 | 55 | 5 | |||

| Upper | 10 | 55 | 6 | |||

| Lower | 15 | 53 | 6 | |||

| Upper Incisor | 34.9 | 33.2-35.8 | 6 | 58 | 7 | |

| Upper Premolar | 35.6 | 34.6-36.2 | 8 | 54 | 7 | |

| Lower incisor | 35.5 | 26-37 | 5 | 50 | 8 | |

| Upper incisor | 33.2 | 32-35 | 13-39 | 9 |

| Smart Alloy | Test | Temperature range [°C] | Length or Span length [mm] | Observed property | Deflection or Load | Observed Transitions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuNiTi & NiTi orthodontic wires (0.406x0.559mm2) |

DTMA in Bending | -20 ÷ 80 | 5 | Storage modulus | 5 g preload 5 µm dynamic amplitude (max force amplitude 40g) | As, Af, Ms, Mf | [12] Kusy & Whitley (2006) |

| CuNiTi & NiTi orthodontic wires (0.392x0.559mm2) |

TMA Stress vs strain in Bending | 10 ÷ 55 | 16 | Young’s modulus | 1Hz loading unloading cycles up to 0.5 mm | As, Af | [8] Laino et al. (2010) |

| NiTi graded orthodontic wire (0.4x0.4 mm2) |

DTMA in Bending | 5 ÷ 40 | 9 | Strain | 0.10 to 0.75 mm | - | [2] Rodrigues et al. (2020) |

| Commercial & orthodontic NiTi (0.43x0.64mm2) | DTMA in Bending | -90 ÷ 120 | 10 | Strain | 2 mm | - | [13] Nespoli et al. (2022) |

| NiTi orthodontic wires (0.483x0.635mm2) | Stress vs strain in Bending (Mode II) | 30 ÷ 40 | 5 | Force Energy loss |

steps of 0.2 mm up to 4 mm |

- | [14] Sakima et al. (2006) |

| NiTi (φ=0.35 mm) |

Stress vs strain in Tension | -195 ÷ 10 | 16 | Stress and Electrical resistivity | Strain rate of 5.2x10-4sec-1 |

Af, Ms | [15] Miyazaki et al. (1981) |

| NiTi orthodontic wires (φ=0.406 mm) |

DTMA in Tension | -120 ÷ 200 | L/A ≥ 3.6 cm-1 | Storage modulus | 20 g preload Dymamic load at 11Hz |

As, Af | [16] Kusy and Wilson (1990) |

| Commercial shape memory NiTi wire (φ=0.279 mm) |

DTMA in Tension | -65 ÷ 45 | 15 | Strain | 15 N | As, Af, Ms, Mf | [17] Lahoz & Puértolas (2004) |

| Flexinol NiTi strips (2.52x0.52 mm2) | TMA in Tension | -50 ÷ 200 | 35 | Storage & loss modulus | 18 N | As, Af, Ms, Mf | [18] Florian et al. (2019) |

| Commercial smart NiTi cable and wire (φ=0.35 mm) | Stress vs strain in Tension | 35 ÷ 85 | 12.6 | Stress | 7.5% maximum strain; strain rate of 0.5%/min | Af, Ms | [19] Silva et al. (2022) |

| CuNiTi & NiTi orthodontic wires (0.432x0.635mm2) |

Bent at 1mm and 6mm | 5 ÷ 60 | 10 | Relative electrical resistivity | 1 mm and 6 mm | Mf ÷ Af range | [20] Santoro & Beshers (2000) |

| Tested archwires Alloy | Cross-section | Size [inches] | Size [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiTi | Round | .016 | 0.406 |

| CuNiTi | Round | .016 | 0.406 |

| Heating phase | Cooling phase | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Alloy | Deflection [mm] | As [°C] | Af [°C] | Ms [°C] | Mf [°C] |

| DSC | NiTi | 0 | 18.2 (±1.3) | 25.0 (±1.9) | 20.9 (±1.7) | 13.2 (±1.1) |

| CuNiTi | 0 | 12.5 (±1.2) | 29.7 (±1.8) | 26.7 (±1.9) | 7.6 (±0.9) | |

| TMA | NiTi | 0.25 | 19.1 (±2.8) | 28.5 (±3.7) | 21.8 (±2.1) | 13.5 (±2.5) |

| 0.5 | 20.0 (±3.1) | 34.0 (±3.9) | 28.3 (±2.6) | 12.8 (±2.4) | ||

| 1.0 | 20.0 (±3.2) | 43.2 (±3.6) | 35.0 (±3.7) | 11.4 (±2.9) | ||

| 1.5 | 20.2 (±2.7) | 50.3 (±3.8) | 43.8 (±3.6) | 11.3 (±3.1) | ||

| 2.0 | 20.3 (±2.9) | 50.6 (±3.6) | 44.0 (±3.5) | 11.3 (±2.8) | ||

| 2.5 | 20.3 (±2.6) | 50.8 (±3.9) | 46.2 (±3.7) | 10.8 (±3.1)* | ||

| CuNiTi | 0.25 | 27.4 (±2.1) | 38.0 (±3.4) | 28.8 (±2.3) | 17.8 (±2.9) | |

| 0.5 | 24.7 (±2.7) | 43.5 (±3.4) | 36.1 (±2.5) | 15.7 (±2.8) | ||

| 1.0 | 24.5 (±2.5) | 49.2 (±3.6) | 42.1 (±3.6) | 14.8 (±2.7) | ||

| 1.5 | 24.4 (±2.8) | 50.5 (±3.9) | 43.2 (±4.4) | 13.2 (±3.6) | ||

| 2.0 | 22.8 (±3) | - | - | 11.0 (±2.7)* | ||

| 2.5 | 21.8 (±2.9) | - | - | 11.2 (±2.8)* | ||

| NiTi | DF | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Type | 3 | 17744,62936 | 5914,87645 | 680,66161 | 0 |

| Deflection | 6 | 3453,89886 | 575,64981 | 66,2436 | 0 |

| Interaction | 18 | 3768,61314 | 209,3674 | 24,09321 | 0 |

| Model | 27 | 24967,14136 | 924,70894 | 106,41201 | 0 |

| Error | 112 | 973,268 | 8,68989 | -- | -- |

| Corrected Total | 139 | 25940,40936 | -- | -- | -- |

| CuNiTi | |||||

| Transition Type | 4 | 1604,0748 | 401,0187 | 47,28852 | 0 |

| Deflection | 6 | 2467,08551 | 411,18092 | 48,48685 | 0 |

| Interaction | 18 | 1081,86315 | 60,10351 | 7,08746 | 6,42516E-11 |

| Model | 28 | 18634,96141 | 665,53434 | 78,48046 | 0 |

| Error | 92 | 780,18352 | 8,48026 | -- | -- |

| Corrected Total | 120 | 19415,14493 | -- | -- | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).