1. Introduction

Insomnia is a common sleep disorder defined by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition (ICSD-3) as a single, chronic disorder characterized by sleep initiation or maintenance problems (despite the presence of adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep) and daytime consequences, with a duration criterion of 3 months and a frequency criterion of at least three times per week [

1]. It has been estimated that chronic insomnia is being present in 6% of the population of Western industrialized countries [

2,

3], with large variations among European countries from a low prevalence of 5.7% in Germany up to 19% in France and 6.9% in the Spanish population [

3,

4]. However, approximately 30% of a variety of adult samples drawn from population-based studies reported one or more of the symptoms of insomnia: difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, waking up too early, and in some cases, nonrestorative or poor quality of sleep [

5]. Insomnia is a risk factor for multiple conditions, so that a better understanding and characterization of insomnia may contribute to tailoring individualized evaluation and treatment, as well as to prevent other related diseases [

3].

Diamine oxidase (DAO) is an enzyme encoded by the amine oxidase copper-containing 1 (

AOC1) gene located in chromosome 7 (7q34-q36) in the human genome [

6]. DAO is a secretory protein stored in plasma membrane vesicular structures and responsible for degradation of extracellular histamine [

7,

8]. In mammals, DAO is mainly expressed in the small intestinal villi [

9,

10]. An impaired histamine degradation based on reduced DAO activity and the resulting exogenous histamine excess may cause numerous symptoms due to the ubiquity distribution of histamine receptors in organs and tissues [

11].

Deficiency DAO enzyme has a strong genetic component [

12], but the prevalence in the general population remains undefined. In a recent large random population-based sample of 1051 healthy subjects in the framework of the West Sweden Asthma Study, DAO deficiency was reported in 44% of cases [

13]. DAO activity is largely associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the

AOC1 gene, particularly the three most relevant variants in Caucasian individuals leading to a reduction of DAO enzyme activity are c.47C>T (rs10156191), c.995C>T (rs1049742), c.1990C>G (rs1049793) [

14,

15]. The following frequencies (95% confidence interval [CI]) for these three

AOC1 gene variants among Spanish Caucasian individuals have been reported: rs10156191, 25.4% (20.16-30.58); rs1049742, 6.3% (3.42-9.26); and rs1049793, 30.6% (25.1-36.1) [

14]. In addition, another SNP in the promoter region of the

AOC1 gene has been identified, c.691G>T (rs2052129) with a frequency of 41.7%, which has been associated with a decrease in DAO transcriptional activity [

15].

Histamine intolerance due to DAO dysfunction may cause nonspecific functional gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms with a large variability and complex symptom combinations of digestive, cardiovascular, respiratory, cutaneous, and neurological manifestations [

11]. In relation to the nervous system, a high rate of DAO deficiency by 87% of patients with proven diagnosis of migraine has been reported [

16]. In a cohort of pediatric patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the prevalence of having at least one minor dysfunctional allele was 78.5% [

17], and in women with fibromyalgia, the prevalence of genetic DAO deficiency was 74.5% based on alterations of the four variants of the

AOC1 gene [

18]. Sleep issues like insomnia can affect patients with these disorders [

19,

20,

21]. Moreover, sleep problems are frequent complaints in subjects with DAO deficiency, however, as far as we are aware, DAO deficiency in subjects with insomnia symptoms has not been previously evaluated.

Therefore, the objective of the study was to determine the prevalence of DAO deficiency of genetic origin in subjects who presented insomnia symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

A prospective study of the prevalence of DAO enzyme deficiency in patients with insomnia-related symptoms was conducted at AdSalutem Sleep Institute, which is a reference center specialized in sleep medicine that provides a complete range of evaluation and treatment of sleep disturbances for children and adults, located in Barcelona, Spain. Between May 5 and November 27, 2023, all consecutive patients who met the eligibility criteria and provided written consent were included in the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: subjects of both genders, 18 years of age or older, and presence of one or more insomnia-related symptoms, including difficulty to fall asleep, difficulty to stay asleep, or wake up too early and not able to get back to sleep. Patients in which insomnia-related symptoms could be caused by other sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea, narcolepsy, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, parasomnia, etc. were excluded from the study. Subjects with a previous diagnosis of DAO enzyme deficiency and following a low-histamine diet or receiving dietary DAO enzyme supplementation were also excluded.

The primary objective of the study was to determine the number (and percentage) of patients with insomnia-related symptoms and DAO enzyme deficiency, defined as the presence of at least one of the four most relevant SNP variants of the AOC1 gene, including c.691G>7 (rs2052129), c.47C>T (rs10156191), c.995C>T (rs1049742), and c.1990C>G (rs1049793). Secondary objectives included the assessment of DAO deficiency and type of SNPs in relation to the study variables, including anthropometric data, insomnia-related symptoms, daytime symptoms, and other DAO deficiency associated symptoms.

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CEIC) of Grupo Hospitalario Quirón Cataluña (code DAO-SLEEP-2022, approval date May 4, 2023), Sant Cugat del Vallés, Barcelona, Spain. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06488027).

2.2. Sample Collection and Genotyping

The four most relevant SNP variants of the AOC1 gene, were measured using the DAO-Test® Genotyping Assay kit (DR Healthcare, Barcelona, Spain). Saliva samples from the oral mucosa were collected by rubbing the inner side of both cheeks using a sterile cotton swab. The genotyping was performed with a Multiplex (Single-Nucleotide Primer Extension) SNuPE (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) followed by capillary electrophoresis in an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.3. Data Collection

For each participant, the following data were collected: demographic and anthropometric variables; DAO deficiency (defined as the presence of at least one SPN of the AOC1 gene and categorized as yes/no); number and distribution of the four variants of the AOC1 gene; insomnia-related symptoms (trouble falling asleep, staying asleep, early morning awakening, frequency of insomnia categorized as less than 3 or more than 3 days a week, and daily; daytime repercussions (somnolence, fatigue, cognitive impairment, poor concentration, lack of attention or memory, mood changes, and headache); other symptoms (fibromyalgia, migraine, ADHD, allergy-hypersensitivity, gastrointestinal complaints); and sleep medications (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] classification). In addition, a DAO-score based on the number of SNPs was developed, the range of which varied between 0 and 8, where 0 = absence of variants, 1 = heterozygous variant, and 2 = homozygous variant. Therefore, in case of all four homozygous variants, a DAO-score of 8 is obtained.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as mean and standard deviation (SD) and 95% confidence interval (CI), or median an interquartile range (IQR) (25th-75th percentile). The chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test were used for the comparison of categorical variables, and the Student’s

t test or the Mann-Whitney

U test for the comparison of quantitative variables according to conditions of application. Study variables were analyzed in relation to DAO deficiency, DAO-score, and type and number of SNP variants. A specific analysis of the relationship between the c.1990C>G (rs1049793) and the study variables was performed as this is one of the SNPs that has been mostly observed to cause DAO deficiency and low functionality of histamine metabolism in Caucasian individuals [

16,

17,

18]. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the independent association of genotypic variants and their combinations with specific insomnia-related symptoms, as well as predictive variables of specific genotypic variants. Variables with a

p value < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the regression models with a stepwise backward selection procedure, and variables with a

p value > 0.3 were removed. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% Cis were estimated. Statistical significance was set at

p < 0.05. The R statistical software package (v4.0.0; R Core Team 2020) was used for the analysis of data.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Patients, Prevalence of DAO Deficiency, and SNPs Variants

Over the 6-month recruitment period, a total of 167 patients met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study. There were 50 men and 117 women, with a mean (SD) age of 48.3 (13.5) years, and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 23.8 (4.3) kg/m2.

DAO deficiency was present in 138 patients, with a prevalence rate of 82.6% (95% CI 76-88.1%). In 29 patients (17.4%), no SPNs were found, whereas in the remaining 138 with SNPs, there were 125 (74.9%) heterozygous carriers and 13 (7.8%) homozygous carriers.

The general characteristics of the study population are shown in

Table 1. Difficulties in staying asleep was the most common complaint in 88% of patients followed by trouble falling asleep in 60.5%. More than half of patients suffered from insomnia symptoms every day and only 9.6% less than 3 days per week. Also, 99.4% reported daytime consequences of insomnia, with fatigue (79.6%), mood changes (72.5%), and poor concentration in 70.1%. Other DAO deficiency-related symptoms included gastrointestinal complaints in 49.1% of cases, respiratory allergies in 25.7%, and migraine in 18.6%. Sleep medications were recorded in 84.9% of subjects, with melatonin alone (24.0%) or combined with psychotropic drugs (36.5%) as the most common medications. Moreover, 60.5% of patients used over-the-counter sleep aids, 28.1% benzodiazepines, 27.5% alpha2-delta ligands, and 10.8% selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

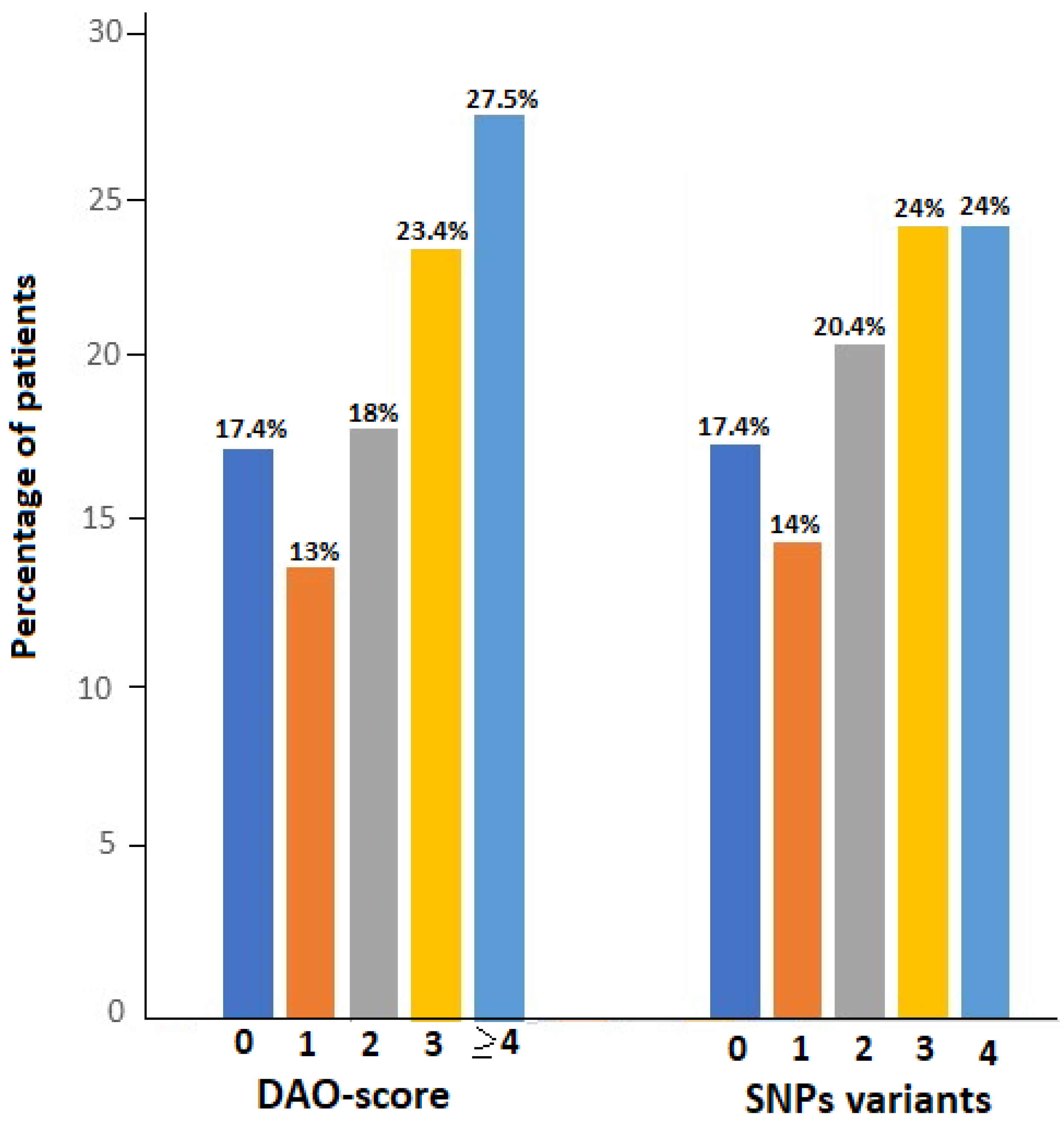

As shown in

Figure 1, DAO-score was ≥ 4 in 46 patients (27.5%), 3 in 39 (23.4%), 2 in 30 (18.0%), and 1 in 23 (13.8%). The number of altered variants was 4 and 3 in 24% of patients, 2 in 34 (20.4%), and 1 in 24 (14.4%). There was a large number of different combinations of SNPs variants, with the two most frequent being ‘c.691G>T or c.995C>7 or c.1990C>G’ in 133 patients (79.6%) and ‘c.691G>T and c.47C>T’ in 93 (55.7%) (

Table S1, Supplementary materials).

3.2. DAO Deficiency and DAO-Score in Relation to the Study Variables

The distribution of the study variables in the groups of 138 patients with DAO deficiency and 29 patients without DAO deficiency was similar, and there were no statistically significant differences between the groups. However, there were minor non-significant differences in some variables, with patients with DAO deficiency showing higher percentages of difficulty to fall asleep (61.6% vs. 55.2%), early morning awakening (54.3% vs. 51.7%) and reporting daytime lack of attention or memory (57.2% vs. 51.7%) as compared to those without DAO deficiency. Food and pharmacological allergy-hypersensitivity showed a trend towards statistical significance, being more frequent among patients with DAO deficiency than in those without DAO deficiency (21.7% vs. 6.9%, p = 0.072).

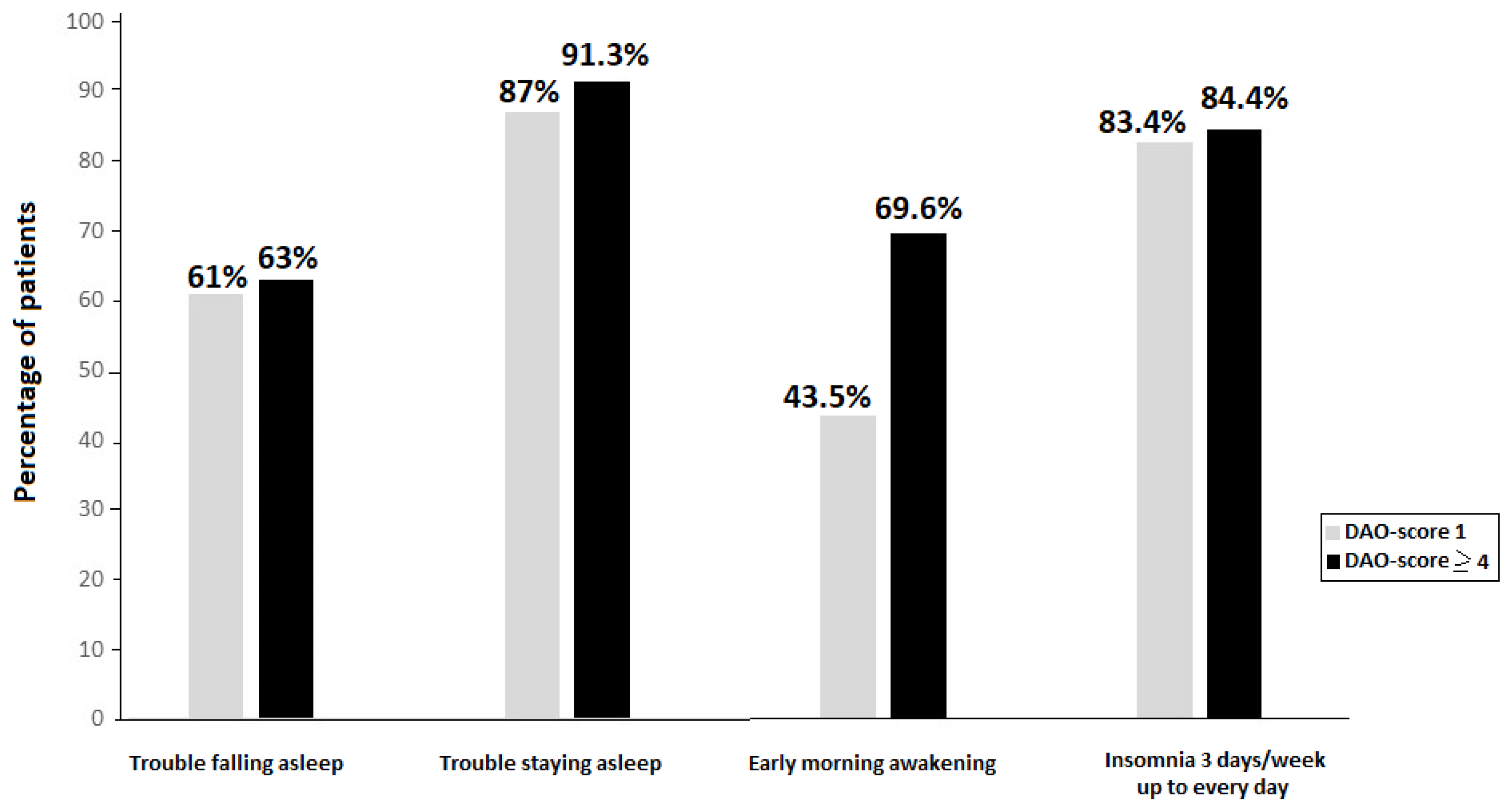

In the analysis of insomnia-related symptoms according to the DAO-score, patients with DAO-score ≥ 4 showed higher percentages of nighttime symptoms than those with DAO-score 0, with statistically significant differences in the item of early morning awakenings (69.6 vs. 46.2%,

p = 0.045).

Figure 2 shows the comparison between patients with DAO-score 1 and those with DAO-score ≥ 4 for nighttime insomnia-related symptoms, with somewhat higher percentages among patients with DAO-score ≥ 4.

In relation to daytime repercussions, lack of attention or memory was more frequent in the DAO-score group 1 than in group 3 (73.9% vs. 46.2%, p = 0.038) and mood changes were more frequent in DAO-score 2 than in DAO-score ≥ 4 (86.7% vs. 60.9%, p = 0.019). Also, food and pharmacological allergies-hypersensitivities were more frequent in patients with DAO-score 3 than in those with DAO-score 0 (28.2% vs. 6.9%, p = 0.032). DAO-score was also unrelated to sleep medications, although a higher percentage of patients with DAO-score ≥ 4 used sleep medications than those with DAO-score 0 (91.1% vs. 89.7%, p = 1.0) and DAO-score 1 (91.1% vs. 82.6%, p = 0.428).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with nighttime insomnia symptoms according to DAO-score.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with nighttime insomnia symptoms according to DAO-score.

3.3. Type and Number of SNPs Variants in Relation to the Study Variables

The distribution of genetic variants of the

AOC1 gene according to absence of allelic variants and heterozygous and homozygous SNPs carriers did not show statistically significant differences in relation to demographic and anthropometric data, nighttime and daytime repercussions related to insomnia, and other symptoms related to DAO deficiency. However, in the particular case of the c.1990C>G (rs1049793) variant, carriers of c.1990C>G as compared to non-carriers showed significantly higher percentages of trouble staying asleep (94.4% vs. 83.3%,

p = 0.032) and early morning awaking (66.2% vs. 44.8%,

p = 0.007) (

Table 2). Other differences in the remaining study variables were not significant. In the analysis of the combinations of SNPs variants, all combinations in which the c.1990C>G was present showed higher percentages of patients with early morning awakening than in those in whom this symptom was not present (

Table 2).

In relation to the number of SNPs, demographic and anthropometric variables showed a similar distribution among patients with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 variants. Insomnia-related variables also followed a similar pattern, except for early morning awakening which was more frequent in patients with 4 variants than in those with 2 variants (70% vs. 44.1%, p = 0.038). Other differences in daytime repercussions and other DAO deficiency-related manifestations were not found.

3.4. Predictive Variables of Insomnia-Related Symptoms and SNPs Variants

In the logistic regression analysis, some SNPs variants alone or combined were independent variables significantly associated with some nighttime and daytime insomnia-related symptoms and manifestations associated with DAO deficiency (

Table 3). The combinations of (c.691G>T) & (c.47C>T) & (c.1990C>G) showed an increased risk of trouble staying asleep (OR 4.28) and early morning awakening (OR 3.59), whereas patients with (c.691G>T) or (c.995C>T) showed a 2.9 reduced risk of cognitive impairment (OR 0.34) than the remaining patients. The risk of mood changes showed a 2.33 decrease (OR 0.42) in patients with (c.47C>T) & (c.1990C>G). Patients with homozygosity in the (c.47C>T) had a 20-fold higher risk of ADHD related to DAO deficiency than patients with heterozygosity. Finally, the presence of (c.47C>T) & (c.1990C>G) showed and increased risk of allergy/hypersensitivity (OR 1.91) (

Table 3).

Likewise, the presence of some clinical manifestations in patients with insomnia were independent predictors of SNPs of the

AOC1 gene. Early morning awakening, dermatological allergy, and food and pharmacological allergies were significantly associated with some specific variants or combinations (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study carried out in a consecutive sample of 167 adult patients with insomnia-related symptoms attended in daily practice shows a high prevalence rate of DAO deficiency of genetic origin of 82.6%. This finding is clinically relevant as leaves open the possibility for an alternative treatment strategy of sleep problems based on DAO enzyme supplementation. As far as we are aware, genetic DAO deficiency in the setting of patients with insomnia symptoms has not been previously evaluated.

An increase in circulating histamine is a well-known effect of accumulation of exogenous histamine consumed through diet in the presence of low activity of the DAO enzyme to degrade it. Histamine is involved in numerous physiological functions, and strong and consistent evidence exist to suggest that histamine, acting via H

1 and/or H

3 receptors has a pivotal role in the regulation of sleep-wakefulness [

22]. Blockade of the wake promoting effects of histamine via H

1 receptor antagonism has been a widely used approach to the treatment of insomnia [

23,

24]. In fact, over half of all over-the-counter sleep aids contain H

1 receptor antagonists such as diphenhydramine or doxylamine [

25]. In the present study, 141 patients (84.9%) took any sleeping drugs, and the largest percentage of patients (60.5%) reported using over-the-counter medications.

Early awakening insomnia with inability to return to sleep is a characteristic symptom of increased histamine levels. In our study, patients with DAO deficiency showed higher percentages of trouble falling asleep and early awakening as compared with those without DAO deficiency, although differences were not statistically significant. In relation to daytime repercussions, patients with DAO deficiency showed higher percentages of fatigue and somnolence. Notably, it was found that the percentage of patients with food and pharmacological allergy was higher among patients with DAO deficiency (21.7%) as compared to those without DAO deficiency (6.9%), with the difference showing a trend of statistical significance (p = 0.072). Interestingly, when patients were grouped by DAO-score, which reflected the number of heterozygous and homozygous SNPs variants, the group with a DAO-score ≥ 4 showed higher percentages of insomnia-related symptoms, in particular trouble staying asleep and early morning awakening.

The genetic study was based on the identification of the four SNPS (c.-691G>T, c.47C>T, c.995C>T, and c.1990C>G) more frequently identified in histamine intolerance due to DAO enzyme dysfunction. Data of previous studies of changes in DAO levels of genetic origin in diverse diseases especially migraine [

16], ADHD [

17] fibromyalgia [

18], and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) [

26] are in agreement with the present findings. In all these studies, a high prevalence of genetic DAO deficiency due to these SNPs was found. In a recent retrospective pilot study to investigate the prevalence of four variants of the diamine oxidase (DAO) encoding gene (

AOC1) in a cohort of 100 patients with symptoms of histamine intolerance and 100 healthy individuals, 79% of individuals with histamine intolerance harbored one or more of the four variants associated with reduced DAO activity [

27]. Moreover, it was found that carrying multiple DAO deficiency-associated gene variants and a high load of risk alleles (homozygous) was more relevant than the mere presence of one or more variants [

27]. In our study, carriers of the c.1990C>G allele either as a single variant or combined with other alleles as compared to non-carriers showed significantly higher rates of insomnia-related symptoms, especially early morning awakening. In the logistic regression analysis, the presence of c.1990C>G (rs1049793) was also a significant independent risk factor for trouble staying asleep and early awakening, as well as insomnia-related daytime repercussions such as cognitive impairment and lack or attention or memory, and other symptoms of DAO deficiency such as allergy-hypersensitivity.

In patients with migraine and DAO deficiency, the SNP c.47C>T (rs10156191) was associated with the risk of developing migraine, particularly in women [

28]. The SNP c.47C>T was also relevant in our study since in combination with other variants was present as a risk factor for trouble staying asleep, early awakening, lack of attention or memory, mood changes, ADHD, and allergy/hypersensitivity. In a prospective cohort of of 100 patients with at least moderate LUTS, SNPs of the

AOC1 gene were found in 88% of the patients, with the presence of c.-691G>T and c.47C>T variants associated with a greater severity of obstructive symptoms [

26]. In a study of 98 Spanish women with fibromyalgia, the prevalence of genetic DAO deficiency was 74.5% based on the four variants of the

AOC1 gene [

18]. SNP deficits were found at frequencies of 53.1% for c.47C>T, 49% for c.691G >T, 48% for c.691G>7, and 19.4% for c.995C>T, which did not differ from the European population [

18]. In the present study, a somewhat higher percentages of SNPs deficits were found, with 65% for c.691G>7 (rs2052129), 63.5% for c.47C>T (rs10156191), 51.5% for c.995C>T (rs1049742), and 42.5% for c.1990C>G (rs1049793). However, based on the high frequency of the allele frequencies found in patients with insomnia-related symptoms, genotyping assessment of the

AOC1 gene may constitute a valuable biomarker of DAO enzymatic activity in subjects presenting with sleep problems.

Allergy-hypersensitivity (respiratory, food, pharmacological, and dermatological) and gastrointestinal complaints were also frequently recorded in our study sample. Food and pharmacological allergies/hypersensitivity occurred in 21.7% of patients with DAO deficiency as compared to 6.9% in those without DAO deficiency. Also, patients with the combination of (c.47C>T) & (c.1990C>G) showed a 1.91-fold increased risk of suffering from allergies or hypersensitivity compared to the other patients. A plausible association between the DAO activity deficit and allergic rhinitis has been reported in an observational study of 108 patients with symptoms of persistent allergic rhinitis, with a prevalence of 46.3% in those with mild rhinitis and 47.9% in those with moderate/severe symptoms [

29]. The authors suggest that allergic rhinitis may be added to other conditions as a potential target of DAO enzyme supplementation [

29].

A recent study in a cohort of 303 children and adolescents with a primary diagnosis of ADHD, 238 patients (78.5%) had at least one of the 4 SNP variants associated with DAO deficiency [

17]. Homozygosity of alleles within rs2052129 and rs10156191 variants related to severe DAO deficiency was associated with lower intelligence quotient (IQ) and much lower working memory [

17]. This interesting observation of

AOC1 gene variants and impairment of cognitive skills in ADHD should be further assessed in other patient populations.

Limitations of the study include the single-center nature of the study, the lack of a control healthy subjects without insomnia-related symptoms, and the fact that serum levels of DAO were not measured. Insomnia-related symptoms were assessed on a clinical basis by sleep specialists, but actigraphy studies were not performed, which could be further included in the design of future studies of genetic DAO deficiency in insomnia patients. However, our preliminary real-world study presents novel evidence of a potential link between DAO enzyme deficiency of genetic origin and clinical symptoms of insomnia.