Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Study Design and Participants

Measured Parameters

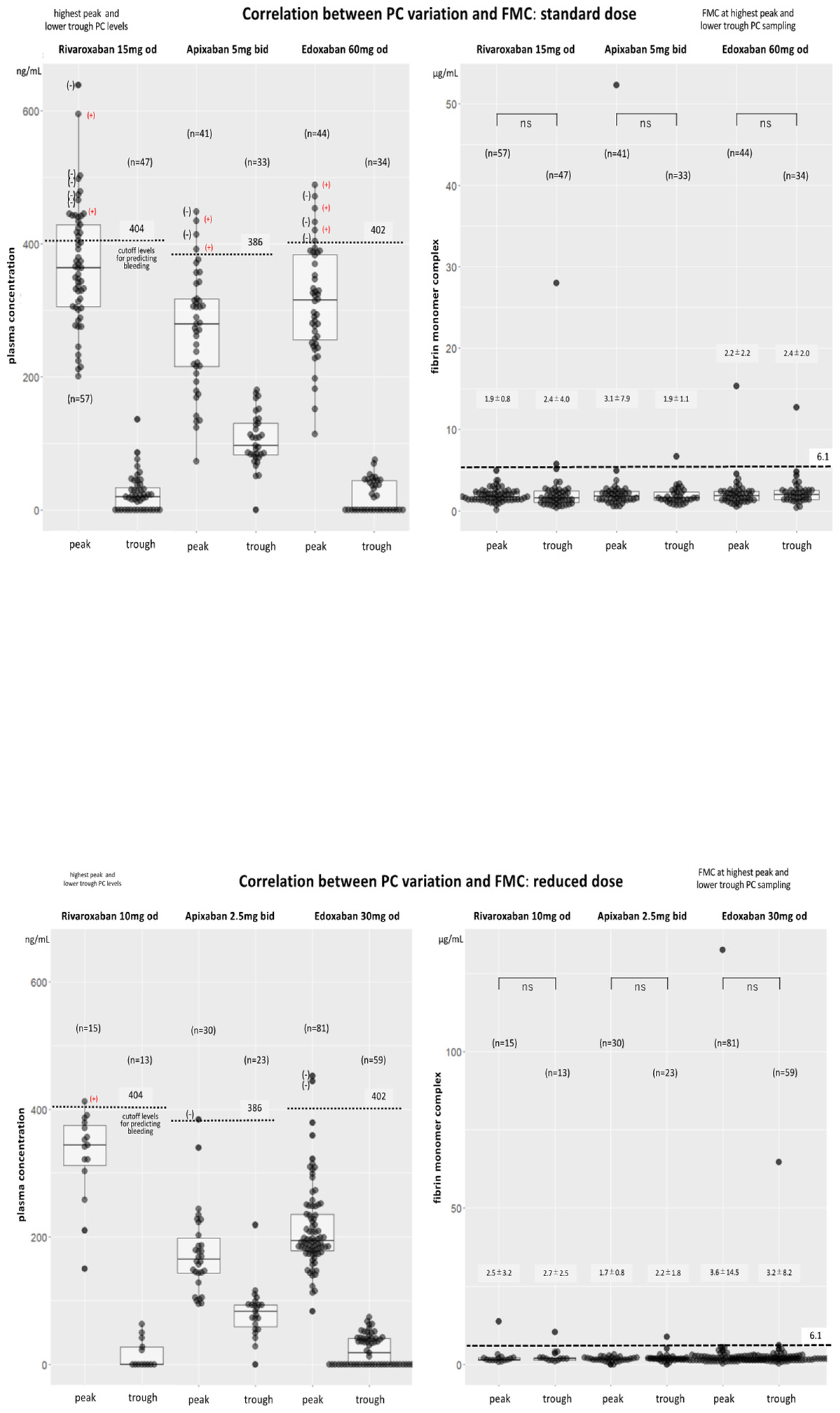

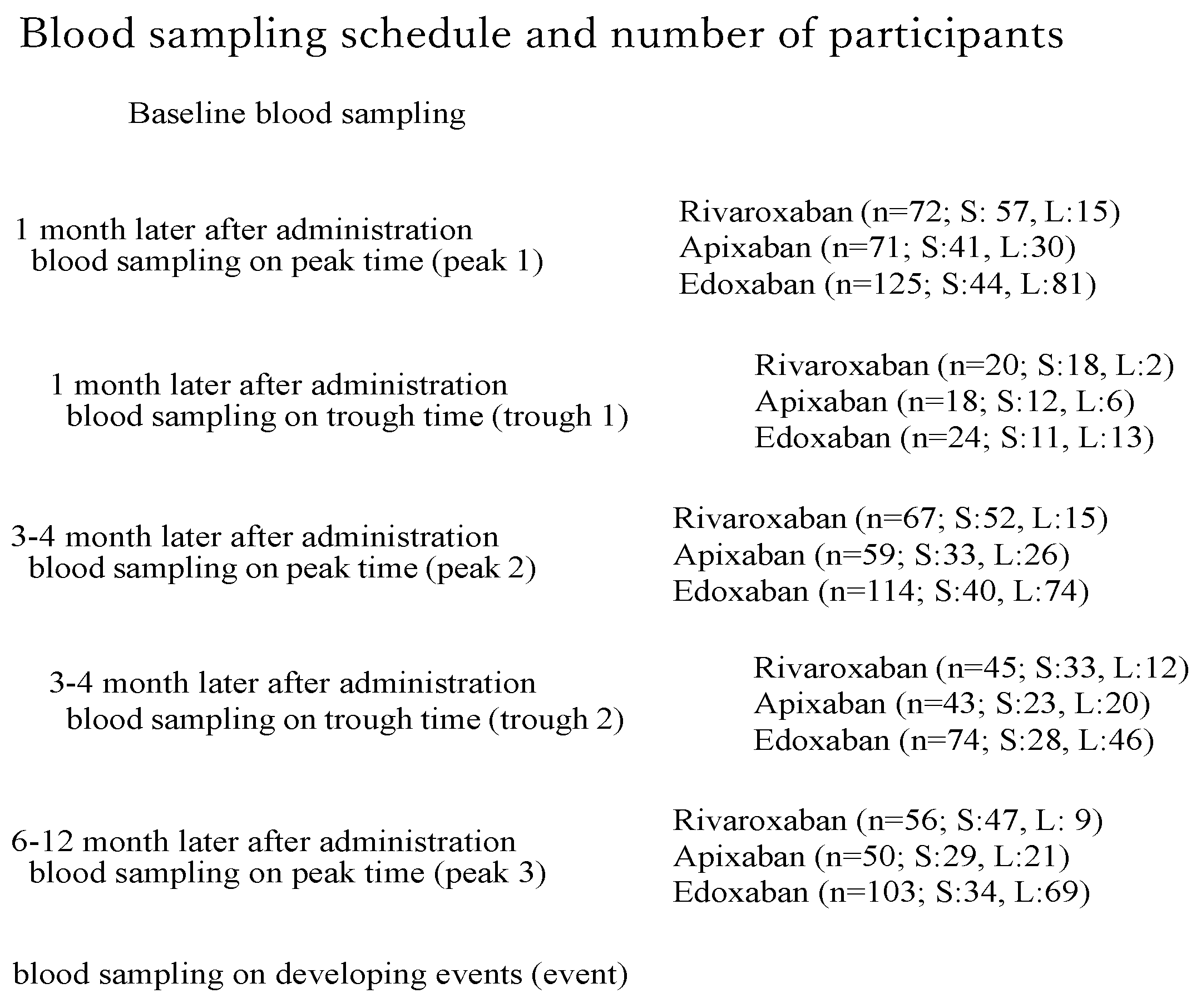

Blood Sampling (Figure 1)

Engineering (TS), Sysmex Corporation

Bleeding and Thromboembolic Events in DOAC Users

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

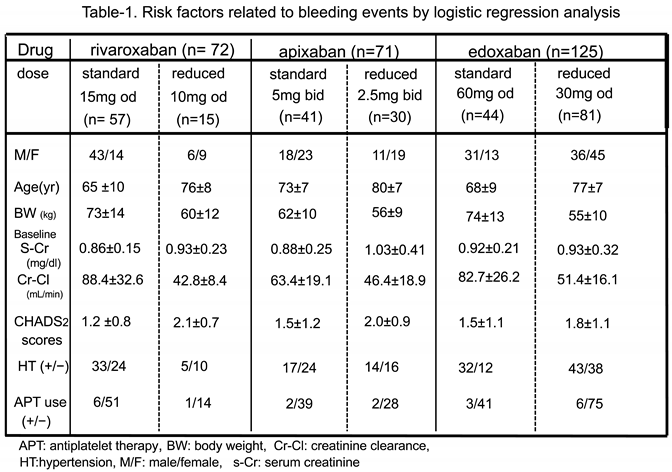

Patient Characteristics (Table 1)

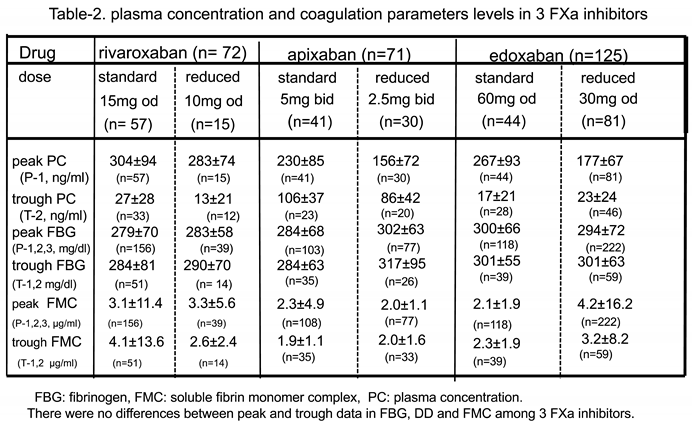

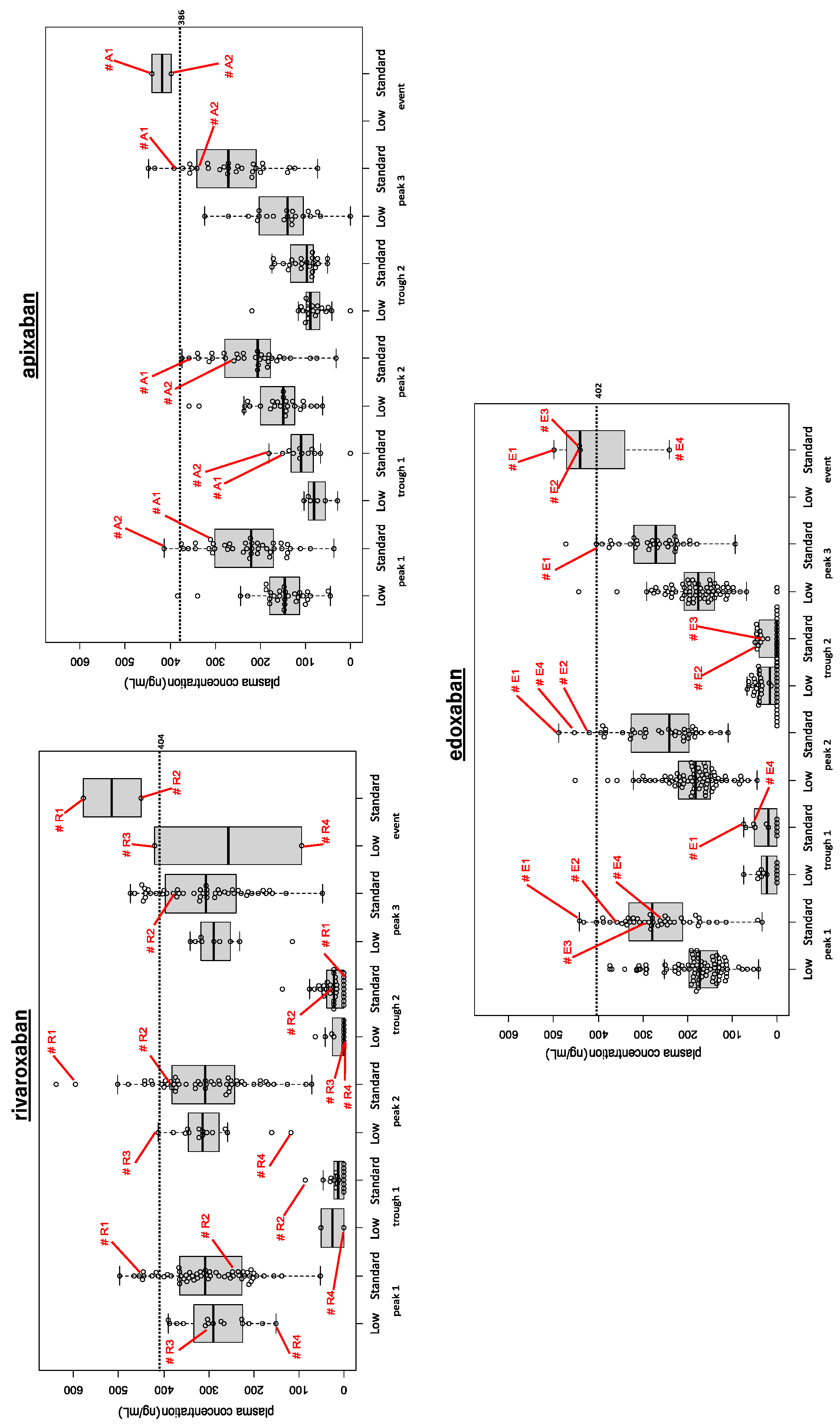

Drug PC Levels among Patients who Received Standard and Reduced Doses in all DOAC Groups(Table 2, Figure 2)

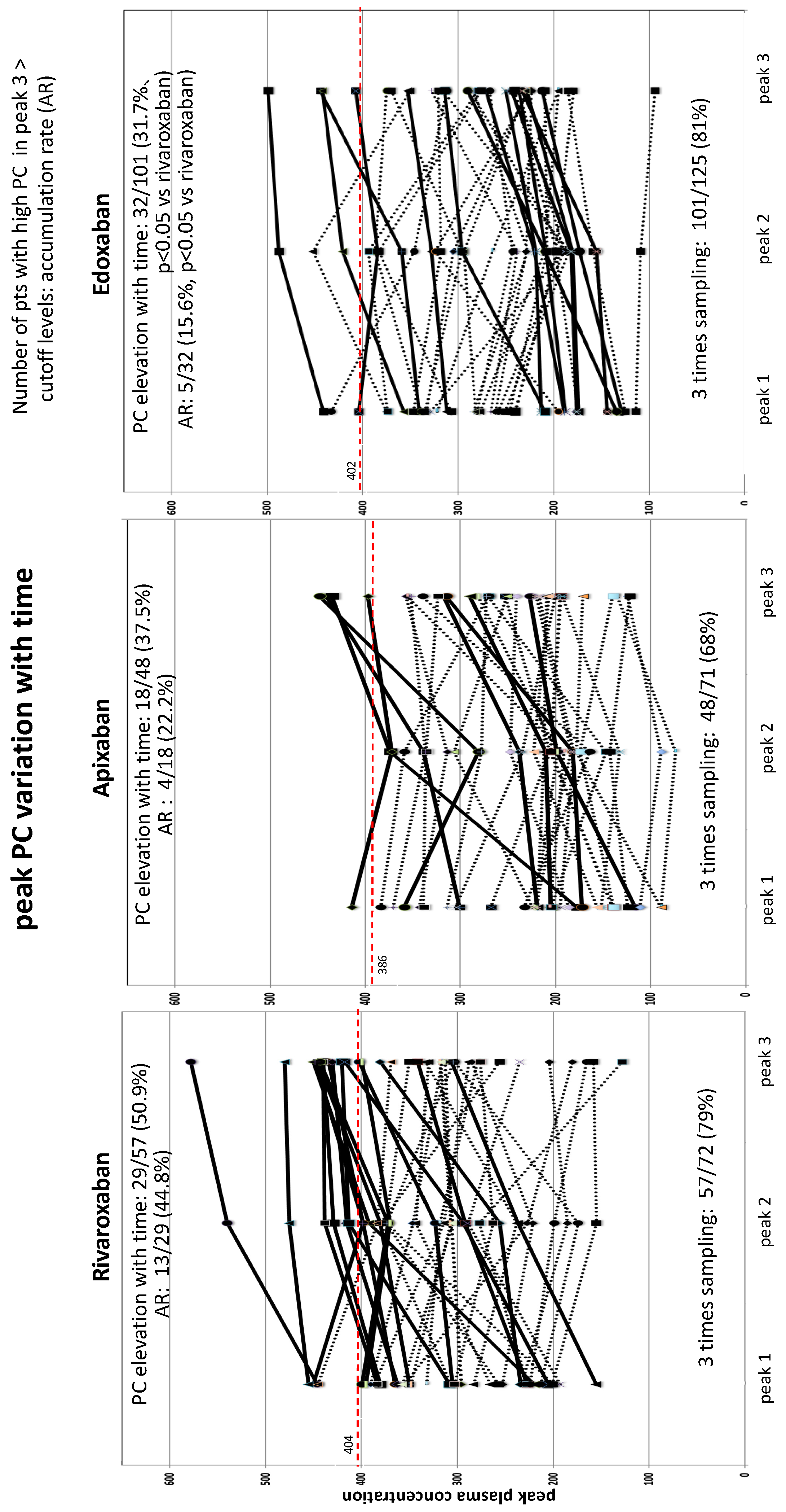

Alterations in Peak PC Over Time among Three DOACs (Figure 2 and Figure 3)

Bleeding and Thromboembolic Events among DOAC Users (Figure 2)

Other Coagulation Biomarkers (Table 2, Figure 4A and Figure 4B)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board statement

Informed consent statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Steffel, J.; Collins, R.; Antz, M.; Cornu, P.; Desteghe, L.; Haeusler, K.G.; Oldgren, J.; Reinecke, H.; Roldan-Schilling, V.; Rowell, N.; et al. 2021 European Heart Rhythm Association practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2021, 23, 1612-1676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S-R.; Choi, E-K.; Kwon, S.; Han, K-D.; Jung, J-H.; Cha, M-J, Oh, S.; Gregory Y.J. Effectiveness and safety of contemporary oral anticoagulants among Asians with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2019, 50, 2245-2249. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Abraham, N.S.; Sangaralingham, L.R.; Bellolio, F.; McBane, R.D.; Shah, N.D.; Noseworthy, P.A. Effectiveness and safety of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2016, 5, e003725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, M.; Romanazzi, I.; Romiti, G.F.; Farcomeni, A.; Lip, G.Y.H. Real-world use of Apixaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2018, 49, 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Fralick, M.; Colacci, M.; Schneeweiss, S.; Huybrechts, K.F.; Lin, K.J.; Gagne, J.J. Effectiveness and safety of apixaban compared with rivaroxaban for patients with atrial fibrillation in routine practice: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2020, 172, 463-473. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Keshishian, A.V.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, A.; Dhamane, A.D.; Luo, X.; Klem, C.; Ferri, M.; Jiang, J.; Yuce, H. et al. Oral anticoagulants for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in patients with high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2120064. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.S.; Yun, J.E.; Park, J.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.K.; Park, D-W.; Nam, G-B. Outcomes after use of standard- and low-dose non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2019, 50, 110-118. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Stecker, E.; Warden, B.A. Direct oral anticoagulant use: a practical guide to common clinical challenges. J Am Heart Assoc 2020, 9, e017559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwa, M.; Nohara, Y.; Morii, I.; Kino, M. Safety and efficacy re-evaluation of edoxaban and rivaroxaban dosing with plasma concentration monitoring in non-valvular atrial fibrillation: With observations of on-label and off-label dosing. Circ Rep 2023, 5, ,80-89. [CrossRef]

- Tanigawa, T.; Kaneko, M.; Hashizume, K.; Kajikawa, M.; Ueda, H.; Tajiri, M.; Paolini, J.G. Mueck, W. Model-based dose selection for phase III rivaroxaban study in Japanese patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2013, 28, 59-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BIOPHENTMDiXaI http://www.hyphen-biomed.com/images/Notices/BI-BIOPHEN/ANG-D750-02/02-1030 (accessed September 30, 2023).

- Suwa, M.; Morii, I.; Kino, M. Rivaroxaban or apixaban for non-valvular atrial fibrillation: Efficacy and safety of off-label under-dosing according to plasma concentration. Circ J 2019, 83, 991-999. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, S.; Kearon, C. Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in nonsurgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005, 3, 692–694. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hori, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Tanahashi, N.; Momomura, S.; Uchiyama, S.; Goto, S.; Izumi, T.; Koretsune, Y.; Kajikawa, M.; Kato, M.; et al. Rivaroxaban vs. warfarin in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation. The J-ROCKET AF Study. Circ J 2012, 76, 2104-2111. [CrossRef]

- Gong, I.Y.; Kim, R.B. Importance of pharmacokinetic profile and variability as determinants of dose and response to dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban. Can J Cardiol 2013, 29, S23-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Agnelli, G. Edoxaban: A focused review of its clinical pharmacology. Eur Heart J 2014, 35, 1844-1855. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, W.A.; Chung, C.P.; Stein, C.M.; Smalley, W.; Zimmerman, E.; Dupont, W.D.; Hung, A.M.; Daugherty, J.R.; Dickson, A.; Murray, K.T. Association of rivaroxaban vs apixaban with major ischemic or hemorrhagic events in patients with atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2021, 326, 2395-2404. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y-H.; Lee, H-F., See, L-C.; Tu, H-T.; Chao, T-F.; Yeh, Y-H.; Wu, L-S., Kuo, C-T.; Chang, S-H.; Lip, G.Y.H. Effectiveness and safety of four direct oral anticoagulants in Asian patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Chest 2019, 156, 529-543. [CrossRef]

- Clemens, A.; Noack, H.; Brueckmann, M.; Lip, G.Y.H. Twice- or once-daily dosing of novel oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention: A fixed-effects meta-analysis with predefined heterogeneity quality criteria. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e99276. [CrossRef]

- Vrijens, B.; Heidbuchel, H. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: Considerations on once- vs twice-daily regimens and their potential impact on medication adherence. Europace 2015, 17, 514-523. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H-J.; Sohn, I.S.; Jin, E-S.; Bae, Y-J. Adherence and clinical outcomes for twice-daily versus once-daily dosing of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation: Is dosing frequency important? PLOS ONE 2023,18, e0283478. [CrossRef]

- Polymeris, A.A.; Zietz, A.; Schaub, F.; Meya, L.; Traenka, C.; Thilemann, S.; Wallllllgner, B., Hert, L.; Altersberger, V.L.; Seiffge, D.J.;et al. Once versus twice daily direct oral anticoagulants in patients with recent stroke and fibrillation. Eur Stroke J 2022, 7, 221-229.

- Shinohara, T.; Takahashi, N.; Mukai, Y.; Kimura, T. Yamaguchi, K.; Takita, A.; Origasa, H.; Okumura, K.; the KYU-RABLE investigators. Changes in plasma concentrations of edoxaban and coagulation biomarkers according to thromboembolic risk and atrial fibrillation type in patients undergoing catheter ablation: Subanalysis of KYU-RABLE. J Arrhythmia 2021, 37, 70-78. [CrossRef]

- Refaai, M.A.; Riley, P.; Mardovina, T.; Bell, P.D. The clinical significance of fibrin monomers. Thromb Haemost 2018, 118, 1856-1866. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).