Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

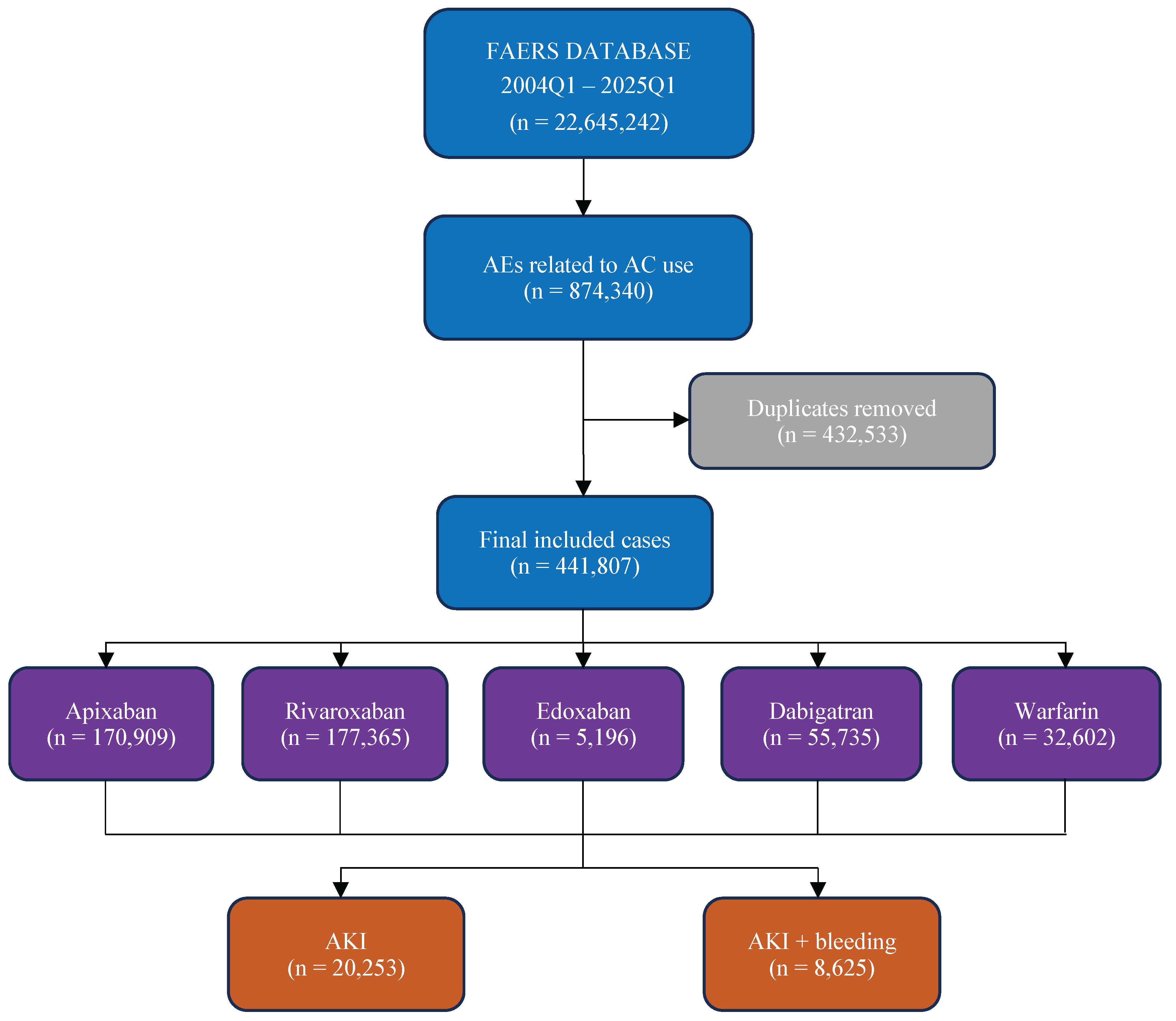

2. Materials and Methods

- ROR025 (lower limit of the 95% confidence interval of ROR) >1 and adverse events >3.

- The IC025 (lower limit of the 95% credible interval of IC) >0.

- Use of PRR detects a signal when the number of co-occurrences is 3 or more and the PRR is 2 or more with an associated x2 value of 4 or more.

- EB05, a lower one-sided 95% confidence limit of EBGM, is considered significant when it is greater than or equal to 2.

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soria Jiménez, C.E.; Papolos, A.I.; Kenigsberg, B.B.; Ben-Dor, I.; Satler, L.F.; Waksman, R.; Cohen, J.E.; Rogers, T. Management of Mechanical Prosthetic Heart Valve Thrombosis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolo, M.; Lane, D.A.; Boriani, G.; Lip, G.Y.H. The Importance of Adherence and Persistence with Oral Anticoagulation Treatment in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy 2021, 7, f81–f83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diavati, S.; Sagris, M.; Terentes-Printzios, D.; Vlachopoulos, C. Anticoagulation Treatment in Venous Thromboembolism: Options and Optimal Duration. Curr Pharm Des 2022, 28, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Alexander, G.C.; Nazarian, S.; Segal, J.B.; Wu, A.W. Trends and Variation in Oral Anticoagulant Choice in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation, 2010-2017. Pharmacotherapy 2018, 38, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, A.I.; Shehab, N.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Weidle, N.J.; Budnitz, D.S. Bleeding Related to Oral Anticoagulants: Trends in US Emergency Department Visits, 2016–2020. Thromb Res 2023, 225, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, T.; Salman, L.A.; Ciaudelli, B.; Cohen, D.A. Anticoagulation-Related Nephropathy: The Most Common Diagnosis You’ve Never Heard Of. The American Journal of Medicine 2019, 132, e631–e633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodsky, S.V.; Satoskar, A.; Chen, J.; Nadasdy, G.; Eagen, J.W.; Hamirani, M.; Hebert, L.; Calomeni, E.; Nadasdy, T. Acute Kidney Injury During Warfarin Therapy Associated With Obstructive Tubular Red Blood Cell Casts: A Report of 9 Cases. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2009, 54, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, S.V.; Collins, M.; Park, E.; Rovin, B.H.; Satoskar, A.A.; Nadasdy, G.; Wu, H.; Bhatt, U.; Nadasdy, T.; Hebert, L.A. Warfarin Therapy That Results in an International Normalization Ratio above the Therapeutic Range Is Associated with Accelerated Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephron Clinical Practice 2010, 115, c142–c146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, S.; Eikelboom, J.; Hebert, L.A. Anticoagulant-Related Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 29, 2787–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrocka, I.; Załuska, W. Anticoagulant-Related Nephropathy: Focus on Novel Agents. A Review. Adv Clin Exp Med 2022, 31, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.A.; Martín-Cleary, C.; Gutiérrez, E.; Toldos, O.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Praga, M.; Ortiz, A.; Egido, J. AKI Associated with Macroscopic Glomerular Hematuria: Clinical and Pathophysiologic Consequences. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012, 7, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaeda, T.; Tamon, A.; Kadoyama, K.; Okuno, Y. Data Mining of the Public Version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Int J Med Sci 2013, 10, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praga, M.; Sevillano, A.; Auñón, P.; González, E. Changes in the Aetiology, Clinical Presentation and Management of Acute Interstitial Nephritis, an Increasingly Common Cause of Acute Kidney Injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015, 30, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazella, M.A. Pharmacology behind Common Drug Nephrotoxicities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 13, 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, J.T.; Freedman, S.B.; Kelly, D.M.; Neuen, B.L.; Perkovic, V.; Jun, M.; Badve, S.V. Kidney Function, Albuminuria, and Risk of Incident Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2024, 83, 350–359.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Liao, D.; Yang, M.; Wang, S. Anticoagulant-Related Nephropathy Induced by Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulants: Clinical Characteristics, Treatments and Outcomes. Thromb Res 2023, 222, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, A.C.; Nagler, E.V.; Morton, R.L.; Masson, P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, R.; Suhail, F.; Lerma, E.V. Cardiovascular Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease. Dis Mon 2015, 61, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Ware, K.; Qamri, Z.; Satoskar, A.; Wu, H.; Nadasdy, G.; Rovin, B.; Hebert, L.; Nadasdy, T.; Brodsky, S.V. Warfarin-Related Nephropathy Is the Tip of the Iceberg: Direct Thrombin Inhibitor Dabigatran Induces Glomerular Hemorrhage with Acute Kidney Injury in Rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014, 29, 2228–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubisz, P.; Stanciakova, L.; Dobrotova, M.; Samos, M.; Mokan, M.; Stasko, J. Apixaban - Metabolism, Pharmacologic Properties and Drug Interactions. Curr Drug Metab 2017, 18, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potpara, T.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Lip, G.Y.H. Use of Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Renal Dysfunction. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018, 14, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasnicka, T.; Malikova, I.; Zenahlikova, Z.; Kettnerova, K.; Brzezkova, R.; Zima, T.; Ulrych, J.; Briza, J.; Netuka, I.; Kvasnicka, J. Rivaroxaban - Metabolism, Pharmacologic Properties and Drug Interactions. Curr Drug Metab 2017, 18, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, K.; Lamparter, M. Prescription of DOACs in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation at Different Stages of Renal Insufficiency. Adv Ther 2023, 40, 4264–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel, Z.; McArthur, E.; Jeyakumar, N.; Sood, M.M.; Garg, A.X.; Silver, S.A.; Dorian, P.; Blum, D.; Beaubien-Souligny, W.; Yan, A.T.; et al. The Risk of Acute Kidney Injury with Oral Anticoagulants in Elderly Adults with Atrial Fibrillation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021, 16, 1470–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, W.C.Y.; Torre, C.O.; Man, K.K.C.; Stewart, H.M.; Seager, S.; Van Zandt, M.; Reich, C.; Li, J.; Brewster, J.; Lip, G.Y.H.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness and Safety Between Apixaban, Dabigatran, Edoxaban, and Rivaroxaban Among Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2022, 175, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gen, S.; Higashi, R.; Nagae, N.; Kigure, R.; Kamikubo, Y.; Nobe, K.; Ikeda, N. Edoxaban-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis. CEN Case Rep 2025, 14, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezue, K.; Ram, P.; Egbuche, O.; Menezes, R.G.; Lerma, E.; Rangaswami, J. Anticoagulation-Related Nephropathy for the Internist: A Concise Review. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2020, 10, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaw, D.J.; Kaiser, S.; Kong, A.; Joshi, S. An Inconspicuous Offender: Apixaban-Induced Anticoagulant-Related Nephropathy. Cureus 2023, 15, e44672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belčič Mikič, T.; Kojc, N.; Frelih, M.; Aleš-Rigler, A.; Večerić-Haler, Ž. Management of Anticoagulant-Related Nephropathy: A Single Center Experience. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, T.M.; Ata, S.I.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Alhawassi, T.M.; Aljadhey, H.S. Signals of Bleeding among Direct-Acting Oral Anticoagulant Users Compared to Those among Warfarin Users: Analyses of the Post-Marketing FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Database, 2010–2015. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018, 14, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, K.T.; Conn, K.M.; van Manen, R.P.; Brown, J.E. Signal Detection for Bleeding Associated with the Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2018, 75, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Thai, S.; Zhou, J.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, T.; Cui, X. Evaluation of Rivaroxaban-, Apixaban- and Dabigatran-Associated Hemorrhagic Events Using the FDA-Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Database. Int J Clin Pharm 2021, 43, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini, R.; Wong, D.B.; Addison, D.; Chiang, E.; Weisbord, S.D.; Jneid, H. Persistent Underrepresentation of Kidney Disease in Randomized, Controlled Trials of Cardiovascular Disease in the Contemporary Era. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 29, 2782–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, I.; Patel, S.; Camargo, M.; Patel, A.; Poojary, P.; Coca, S.G.; Nadkarni, G.N. Representation and Reporting of Kidney Disease in Cerebrovascular Disease: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0176145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, I.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Yacoub, R.; Saha, A.; Simoes, P.; Parikh, C.R.; Coca, S.G. Representation of Patients With Kidney Disease in Trials of Cardiovascular Interventions: An Updated Systematic Review. JAMA Intern Med 2016, 176, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Apixaban | Rivaroxaban | Edoxaban | Dabigatran | Warfarin | Total | |

| Number of Cases | 6581 (32.5) | 7977 (39.4) | 569 (2.8) | 3453 (17.0) | 1673 (8.3) | 20253 |

| Mean age ± SD | 72.6 ± 16.4 | 72.5 ± 12.3 | 76.3 ± 17.7 | 75.4 ± 11.8 | 70.6 ± 14.4 | 72.9 ± 14.1 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 2937 (44.6) | 283 (3.6) | 245 (43.1) | 500 (14.5) | 103 (6.2) | 4068 (20.1) |

| Female | 2896 (44.0) | 253 (3.2) | 209 (36.7) | 451 (13.1) | 67 (4.0) | 3876 (19.1) |

| Unknown | 748 (11.3) | 7441 (93.3) | 115 (20.2) | 2502 (72.5) | 1503 (89.8) | 12309 (60.8) |

| Countries | ||||||

| United States | 1927 (29.3) | 5103 (64.1) | 6 (1.0) | 1361 (39.4) | 493 (29.6) | 8890 (43.9) |

| Japan | 827 (12.6) | 288 (3.6) | 185 (32.5) | 25 (0.7) | 129 (7.7) | 1454 (7.2) |

| France | 821 (12.5) | 539 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 248 (7.2) | 68 (4.1) | 1676 (8.3) |

| Canada | 770 (11.7) | 140 (1.8) | 4 (0.7) | 78 (2.6) | 72 (4.3) | 1064 (5.3) |

| Germany | 630 (9.6) | 409 (5.1) | 155 (27.2) | 195 (5.6) | 17 (1.0) | 1406 (6.9) |

| Indications | ||||||

| Cerebrovascular accident prophylaxis | 1719 (26.1) | 1598 (20.1) | 1 (0.2) | 243 (7.0) | 36 (2.2) | 3597 (17.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 370 (5.6) | 1854 (23.3) | 184 (32.3) | 1653 (47.9) | 254 (15.2) | 4315 (21.3) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 156 (2.4) | 722 (9.1) | 18 (3.2) | 29 (0.8) | 76 (4.6) | 1001 (4.9) |

| Thrombosis prophylaxis | 148 (2.2) | 916 (11.5) | 75 (13.2) | 64 (1.9) | 66 (4.0) | 1269 (6.3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 141 (2.1) | 366 (4.6) | 14 (2.5) | 34 (1.0) | 69 (4.1) | 624 (3.1) |

| Years | ||||||

| 2015 | 260 (4.0) | 607 (7.6) | 0 (0) | 207 (6.0) | 133 (8.0) | 1207 (6.0) |

| 2016 | 348 (5.3) | 1452 (18.2) | 5 (0.9) | 228 (6.6) | 121 (7.3) | 2154 (10.6) |

| 2017 | 437 (6.6) | 1040 (13.1) | 7 (1.2) | 343 (9.9) | 126 (7.6) | 1953 (9.6) |

| 2018 | 609 (9.3) | 1144 (14.4) | 15 (2.6) | 322 (9.3) | 249 (14.9) | 2339 (11.5) |

| 2019 | 758 (11.5) | 591 (7.4) | 14 (2.5) | 285 (8.3) | 207 (12.4) | 1855 (9.2) |

| 2020 | 750 (11.4) | 1397 (17.5) | 27 (4.7) | 203 (5.9) | 186 (11.2) | 2563 (12.7) |

| 2021 | 849 (12.9) | 259 (3.3) | 42 (7.4) | 110 (3.2) | 132 (7.9) | 1392 (6.9) |

| 2022 | 1034 (15.7) | 299 (3.8) | 151 (26.5) | 102 (3.0) | 127 (7.6) | 1713 (8.5) |

| 2023 | 639 (9.7) | 208 (2.6) | 134 (23.6) | 70 (2.0) | 75 (4.5) | 1126 (5.6) |

| 2024 | 604 (9.2) | 193 (2.4) | 148 (26.0) | 46 (1.3) | 61 (3.7) | 1052 (5.2) |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Other outcomes | 3535 (53.7) | 1934 (24.2) | 271 (47.6) | 794 (23.0) | 591 (35.3) | 7125 (35.2) |

| Hospitalized | 2153 (32.7) | 4574 (57.3) | 240 (42.2) | 1780 (51.5) | 753 (45.0) | 9500 (46.9) |

| Died | 398 (6.0) | 1008 (12.6) | 39 (6.9) | 419 (12.1) | 177 (10.6) | 2041 (10.1) |

| Life-threatening | 216 (3.3) | 295 (3.7) | 8 (1.4) | 170 (4.9) | 70 (4.2) | 759 (3.7) |

| Disabled | 44 (0.7) | 31 (0.4) | 9 (1.6) | 44 (1.3) | 24 (1.4) | 152 (0.7) |

| Seriousness | ||||||

| Serious | 6347 (96.4) | 7842 (98.3) | 567 (99.6) | 3207 (92.9) | 1619 (96.8) | 19582 (96.7) |

| Non-Serious | 234 (3.6) | 135 (1.7) | 2 (0.4) | 246 (7.1) | 54 (3.2) | 671 (3.3) |

| Apixaban | Rivaroxaban | Edoxaban | Dabigatran | Warfarin | Total | |

| Number of Cases | 1359 (15.8) | 4243 (49.2) | 156 (1.8) | 1934 (22.4) | 933 (10.8) | 8625 |

| Mean age ± SD | 69.8 ± 19.5 | 72.4 ± 11.9 | 77.3 ± 16.9 | 75.1 ± 11.8 | 71.3 ± 13.4 | 72.5 ± 13.7 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 659 (48.5) | 114 (2.7) | 73 (46.8) | 315 (16.3) | 71 (7.6) | 1232 (14.3) |

| Female | 573 (42.2) | 79 (1.9) | 55 (35.3) | 278 (14.4) | 39 (4.2) | 1024 (11.9) |

| Unknown | 127 (9.3) | 4050 (95.4) | 28 (17.9) | 1341 (69.3) | 823 (88.2) | 6369 (73.8) |

| Countries | ||||||

| United States | 361 (26.6) | 3530 (83.3) | 6 (3.8) | 956 (49.4) | 262 (28.1) | 5115 (59.3) |

| Japan | 113 (8.3) | 44 (1.0) | 31 (19.9) | 9 (0.5) | 56 (6.0) | 253 (2.9) |

| France | 106 (7.8) | 105 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 91 (4.7) | 15 (1.6) | 317 (3.7) |

| Canada | 175 (12.9) | 55 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 40 (2.1) | 36 (3.9) | 307 (3.6) |

| Germany | 193 (14.2) | 106 (2.5) | 61 (39.1) | 110 (5.7) | 5 (0.5) | 475 (5.5) |

| Indications | ||||||

| Cerebrovascular accident prophylaxis | 345 (25.4) | 943 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 126 (6.5) | 18 (19) | 1432 (16.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 117 (8.6) | 1064 (25.1) | 40 (25.6) | 996 (51.5) | 150 (16.1) | 2367 (27.4) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 55 (4.0) | 501 (11.8) | 7 (4.5) | 17 (0.9) | 51 (5.5) | 631 (7.3) |

| Thrombosis prophylaxis | 85 (6.2) | 625 (14.7) | 11 (7.0) | 31 (1.6) | 40 (4.3) | 792 (9.2) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 38 (2.8) | 226 (5.3) | 6 (3.8%) | 16 (0.8) | 35 (3.7) | 321 (3.7) |

| Years | ||||||

| 2015 | 50 (3.7) | 306 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | 83 (4.3) | 59 (6.3) | 498 (5.8) |

| 2016 | 89 (6.5) | 972 (22.9) | 3 (1.9) | 104 (5.4) | 77 (8.3) | 1245 (14.4) |

| 2017 | 118 (8.7) | 641 (15.1) | 4 (2.6) | 178 (9.2) | 71 (7.6) | 1012 (11.7) |

| 2018 | 152 (11.2) | 639 (15.1) | 8 (5.1) | 185 (9.6) | 136 (14.6) | 1120 (13.0) |

| 2019 | 158 (11.6) | 296 (6.9) | 4 (2.6) | 157 (8.1) | 129 (13.9) | 744 (8.6) |

| 2020 | 145 (10.7) | 895 (21.1) | 6 (3.8) | 103 (5.3) | 101 (10.8) | 1250 (14.5) |

| 2021 | 97 (7.1) | 105 (2.5) | 19 (12.2) | 47 (2.4) | 71 (7.6) | 339 (3.9) |

| 2022 | 206 (15.2) | 58 (1.4) | 46 (29.5) | 32 (1.7) | 81 (8.7) | 423 (4.9) |

| 2023 | 144 (10.6) | 55 (1.3) | 21 (13.5) | 30 (1.6) | 34 (3.7) | 284 (3.3) |

| 2024 | 128 (9.4) | 24 (0.6) | 34 (21.8) | 9 (0.5) | 16 (1.7) | 211 (2.4) |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Other outcomes | 557 (41.0) | 565 (13.3) | 51 (32.7) | 381 (19.7) | 276 (29.6) | 1830 (21.2) |

| Hospitalized | 599 (44.1) | 2835 (66.8) | 79 (50.6) | 1090 (56.4) | 460 (49.3) | 5063 (58.7) |

| Died | 114 (8.4) | 657 (15.5) | 20 (12.8) | 262 (13.5) | 122 (13.1) | 1175 (13.6) |

| Life-threatening | 60 (4.4) | 141 (3.3) | 3 (1.9) | 101 (5.2) | 30 (3.2) | 335 (3.9) |

| Disabled | 6 (0.4) | 9 (0.2) | 2 (1.3) | 11 (0.6) | 13 (1.4) | 41 (0.5) |

| Seriousness | ||||||

| Serious | 1336 (98.3) | 4207 (99.2) | 155 (99.4) | 1845 (95.4) | 901 (96.6) | 8444 (97.9) |

| Non-Serious | 23 (1.7) | 36 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 89 (4.6) | 32 (3.4) | 181 (2.1) |

| Drug | Cases | ROR | PPR | Chi Square | p value | IC |

| Apixaban | 6581 | 0.76 (0.73-0.78) | 0.77 (0.74-0.79) | 329.24 | <0.001 | -0.38 (-0.42- -0.34) |

| Rivaroxaban | 7977 | 0.97 (0.95-1.00) | 0.97 (0.95-1.00) | 3.31 | 0.069 | -0.02 (-0.05-0.00) |

| Edoxaban | 569 | 2.63 (2.40-2.87) | 2.45 (2.26-2.65) | 494.57 | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.18-1.35) |

| Dabigatran | 3453 | 1.46 (1.41-1.52) | 1.43 (1.38-1.49) | 392.65 | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.41-0.48) |

| Warfarin | 1673 | 1.14 (1.08-1.20) | 1.13 (1.08-1.19) | 25.27 | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.12-0.22) |

| Drug | Cases | ROR | PPR | Chi Square | p value | IC |

| Apixaban | 1359 | 0.29 (0.28-0.31) | 0.30 (0.28-0.32) | 1926.26 | <0.001 | -1.29 (-1.34- -1.23) |

| Rivaroxaban | 4243 | 1.47 (1.41-1.54) | 1.46 (1.40-1.53) | 319.14 | <0.001 | 0.30 (0.27-0.34) |

| Edoxaban | 156 | 1.59 (1.35-1.86) | 1.57 (1.34-1.83) | 31.60 | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.48-0.80) |

| Dabigatran | 1934 | 2.07 (1.96-2.18) | 2.03 (1.93-2.13) | 793.86 | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.79-0.89) |

| Warfarin | 933 | 1.55 (1.44-1.66) | 1.53 (1.43-1.64) | 156.02 | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.49-0.63) |

| Drug | Cases | ROR | PPR | Chi Square | p value | IC |

| Apixaban | 26 | 0.86 (0.55-1.32) | 0.86 (0.56-1.32) | 0.35 | 0.554 | -0.17 (-0.60-0.26) |

| Rivaroxaban | 69 | 2.25 (1.58-3.22) | 2.21 (1.56-3.13) | 20.12 | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.33-0.92) |

| Edoxaban | 1 | 0.57 (0.08-4.15) | 0.58 (0.08-4.08) | 0.03 | 0.864 | -0.78 (-2.76-1.2) |

| Dabigatran | 20 | 0.59 (0.37-0.96) | 0.6 (0.37-0.96) | 4.15 | 0.042 | -0.59 (-1.07- -0.12) |

| Warfarin | 9 | 0.42 (0.21-0.84) | 0.43 (0.22-0.84) | 5.87 | 0.015 | -1.09 (-1.77- -0.41) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).