Submitted:

11 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

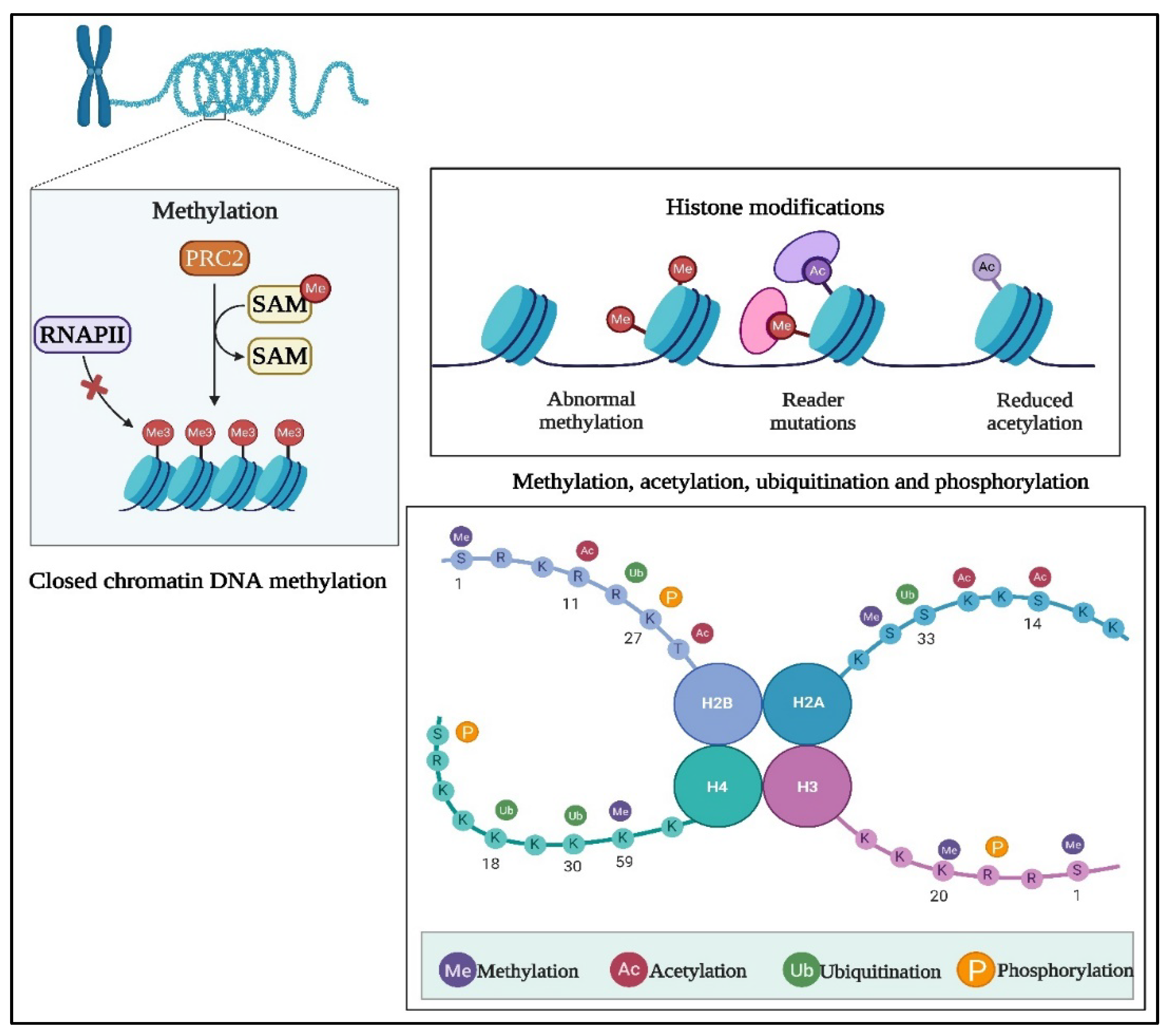

2. Cancer Epigenetics

1.1. DNA Methylation

2.1. Histone Modifications

2.2. Non-Coding RNAs

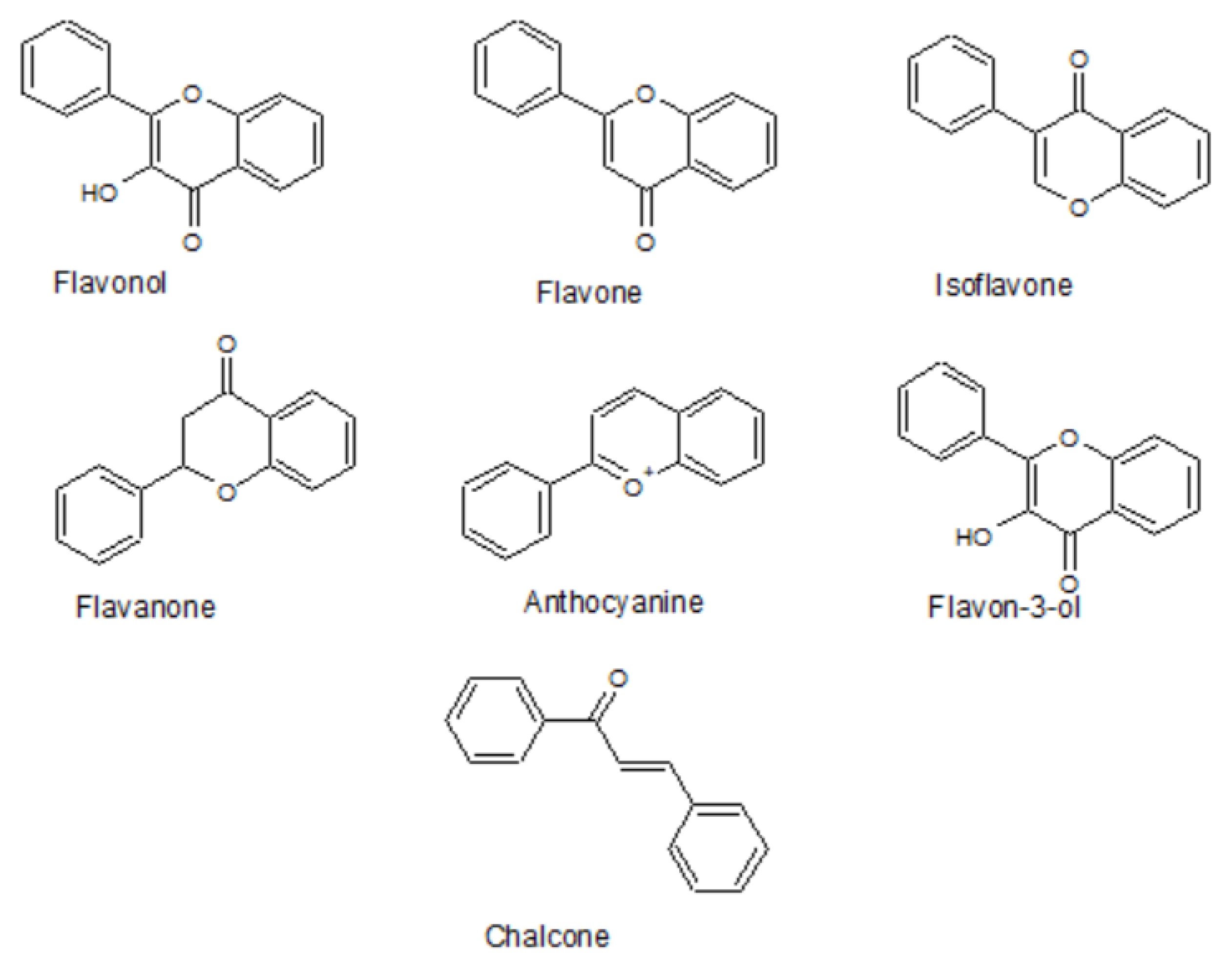

3. Flavonoids As Epigenetic Modulators

4. Cancer Prevention And Therapy By Epigenetically Active Flavonoids

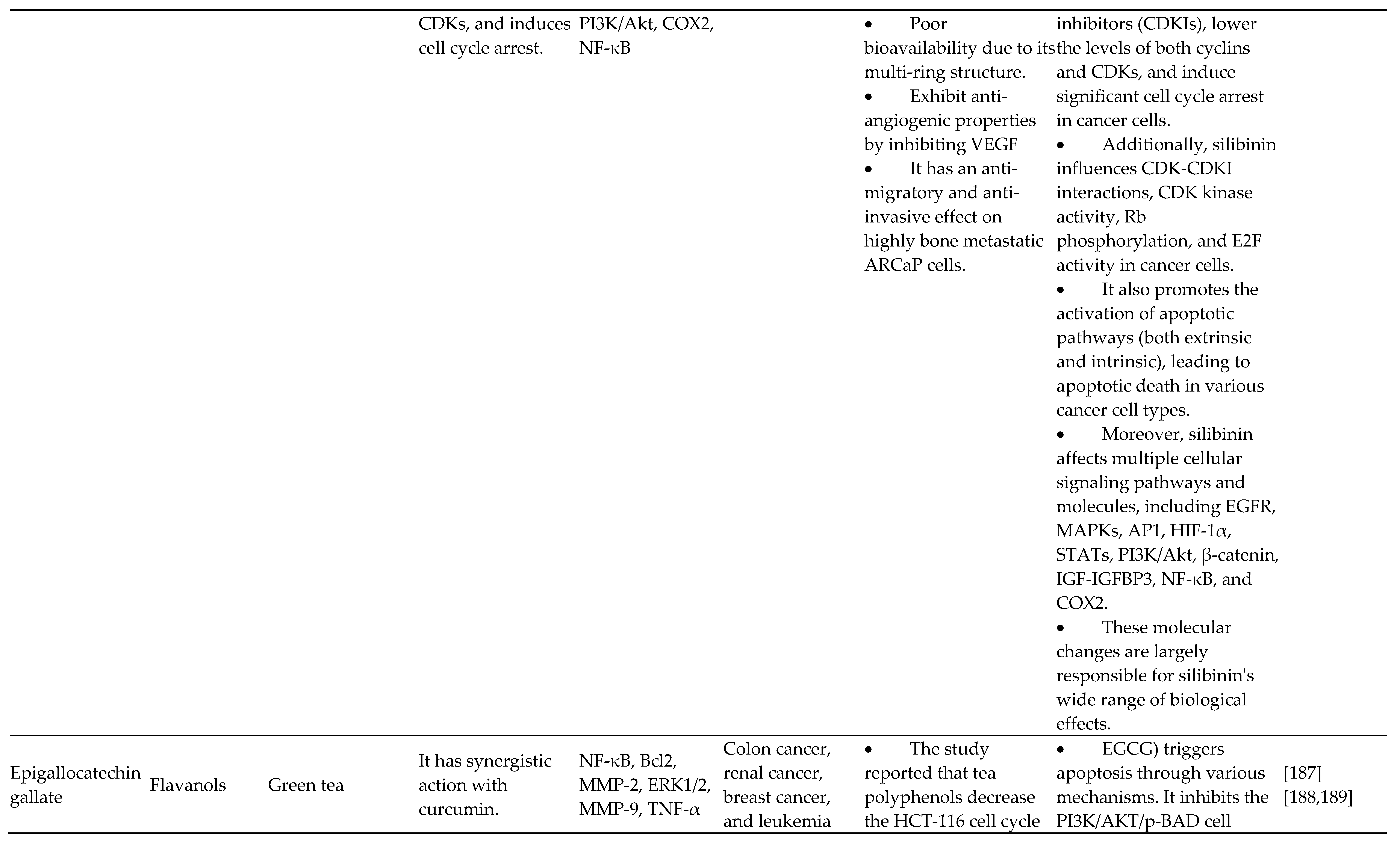

4.1. Flavan-3-Ols/Flavanols/Catechins

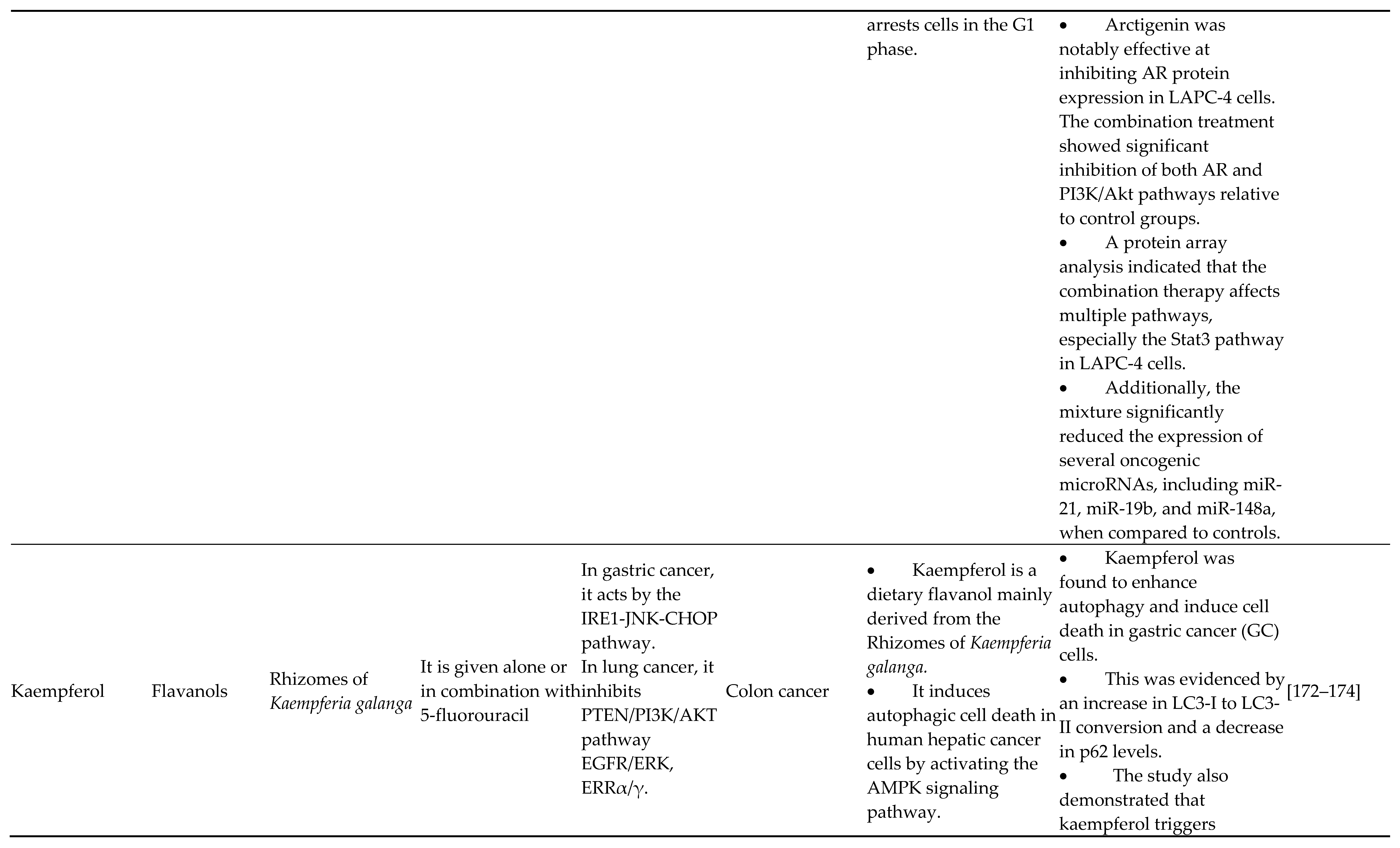

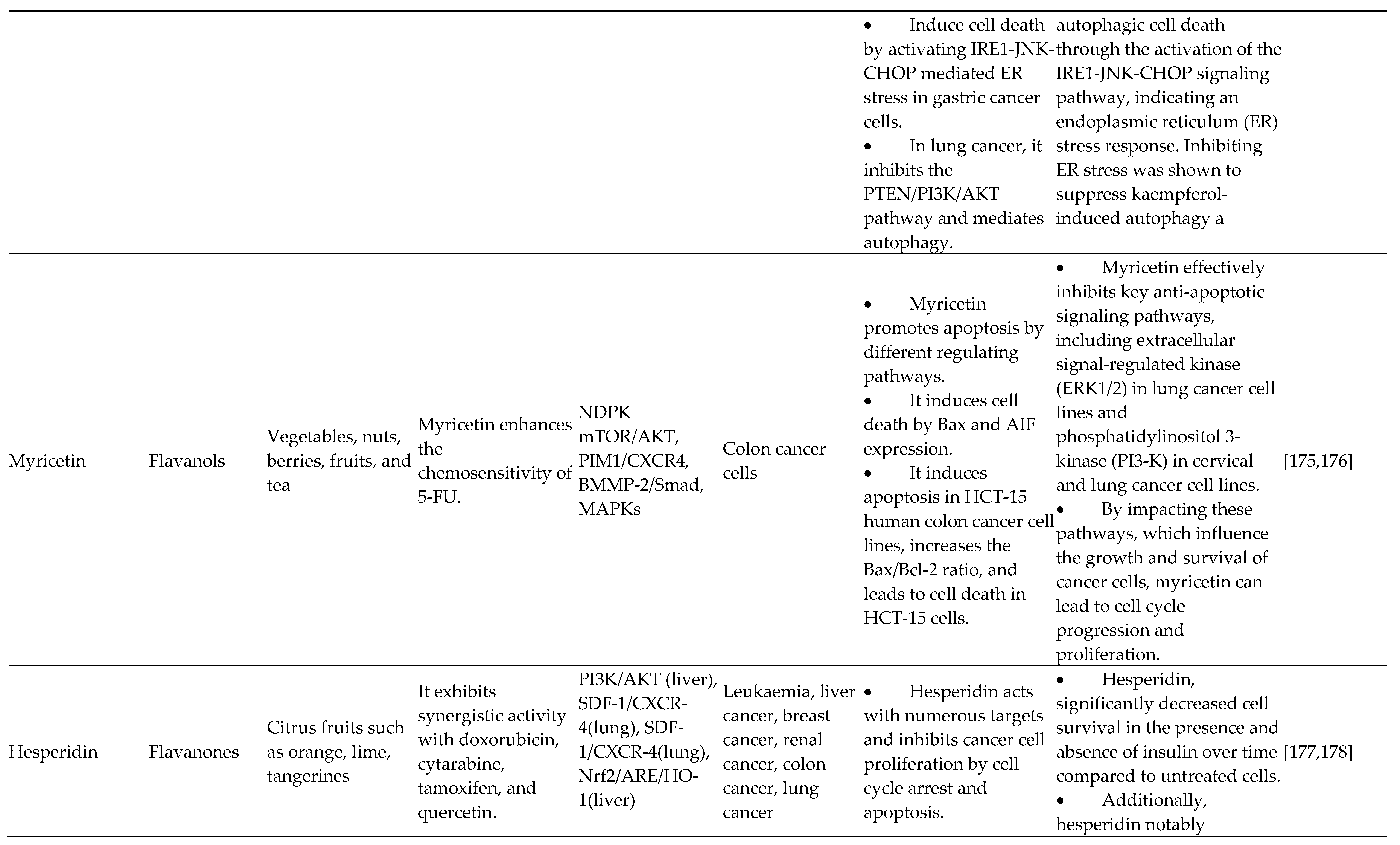

4.2. Flavonols

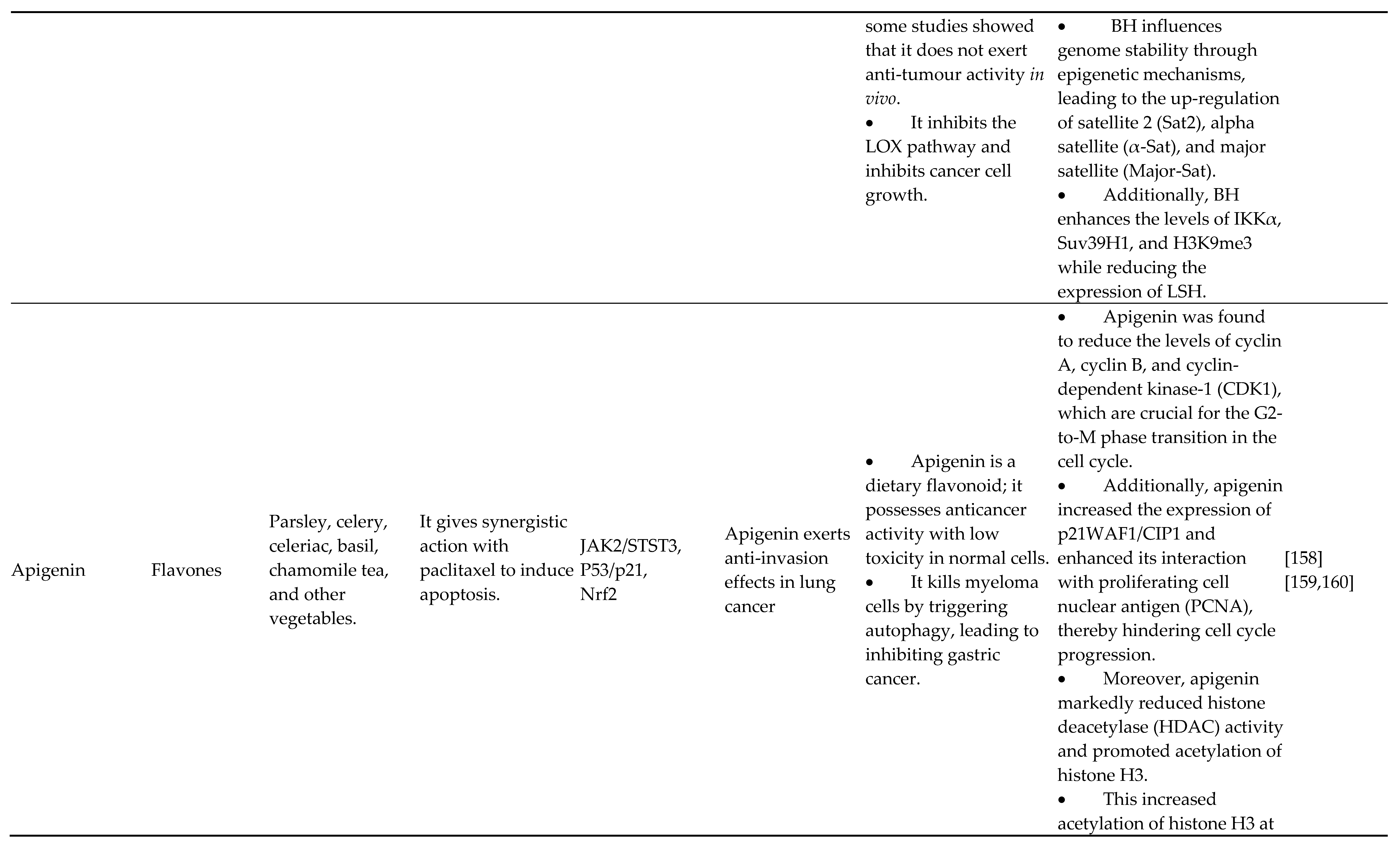

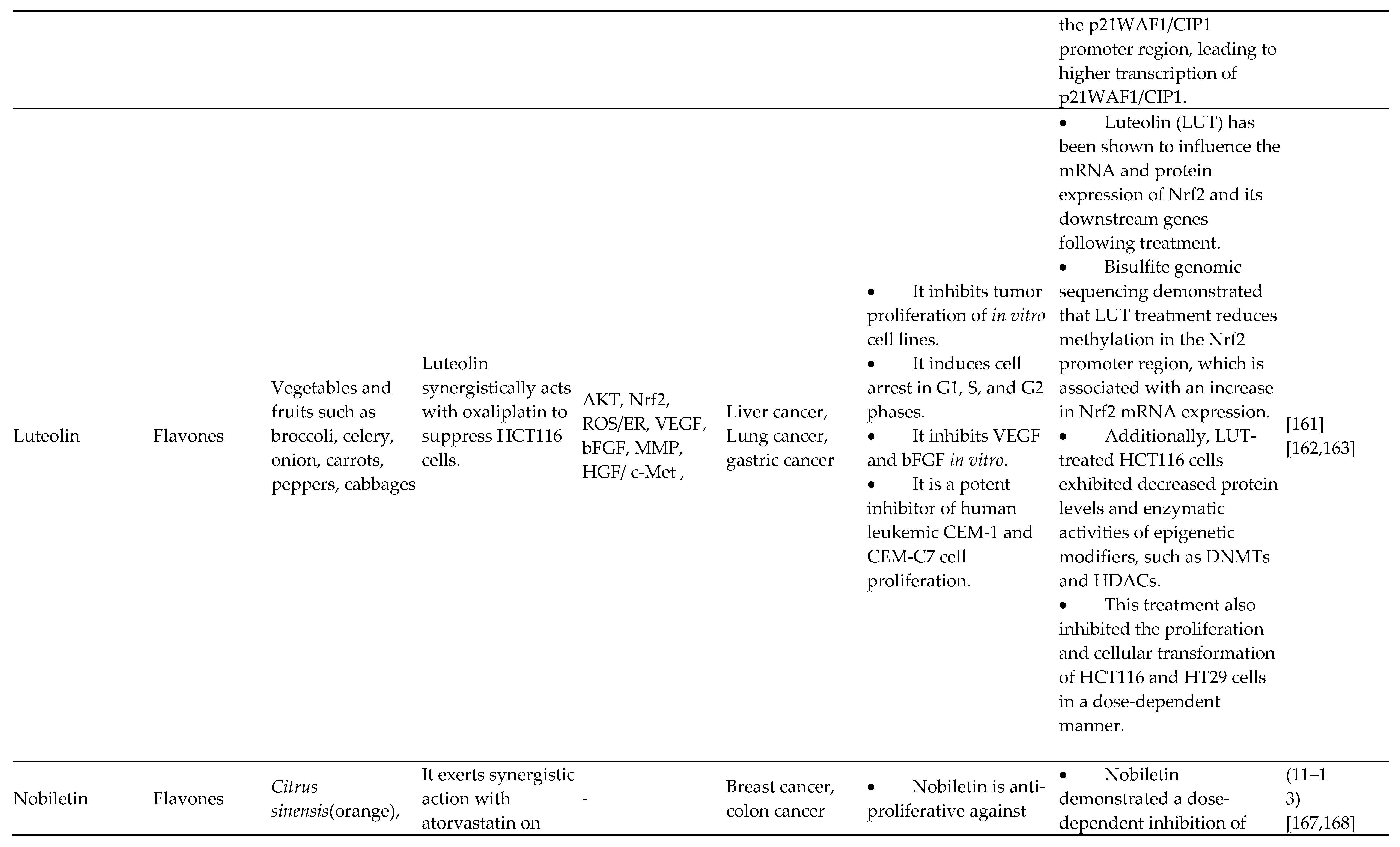

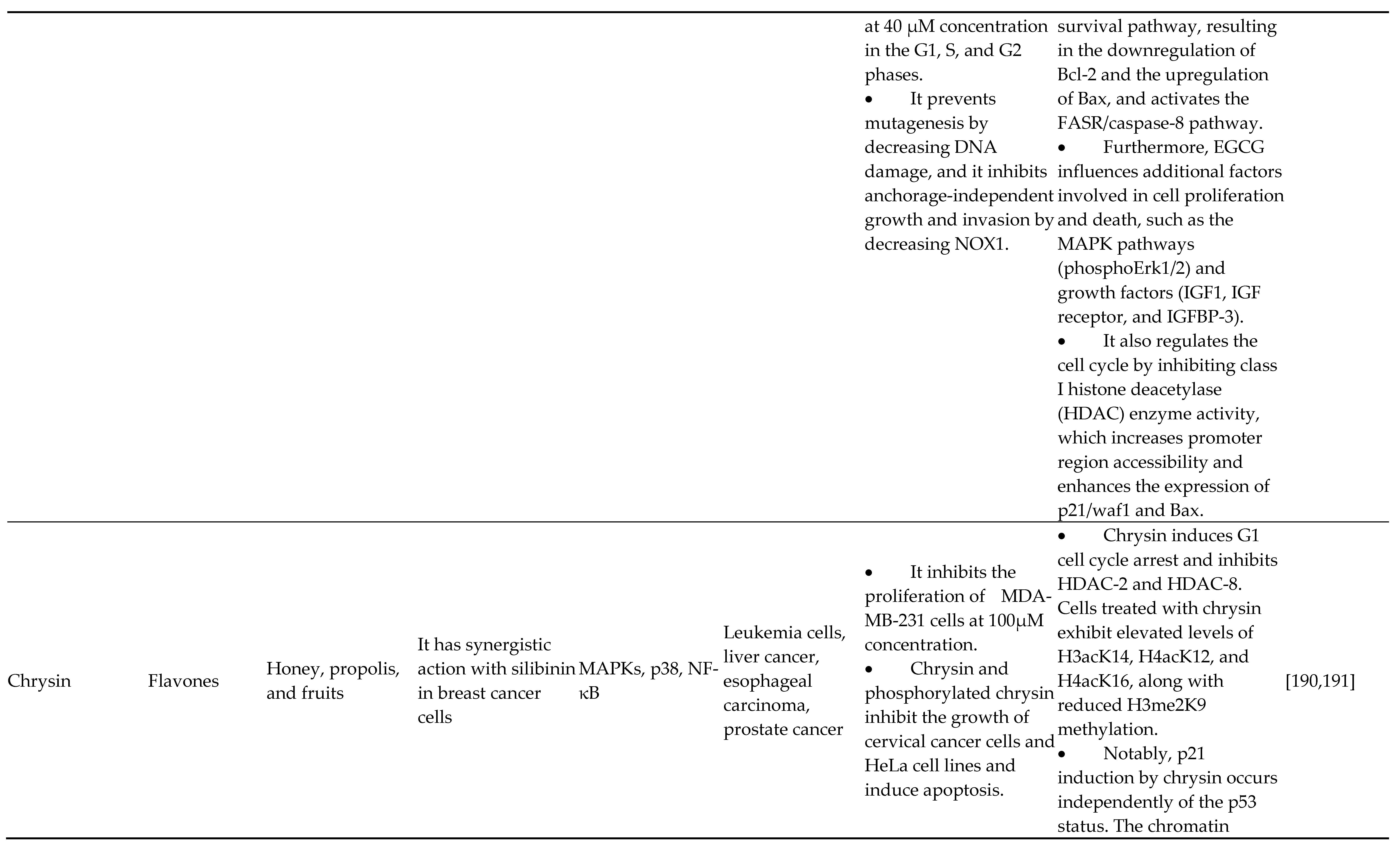

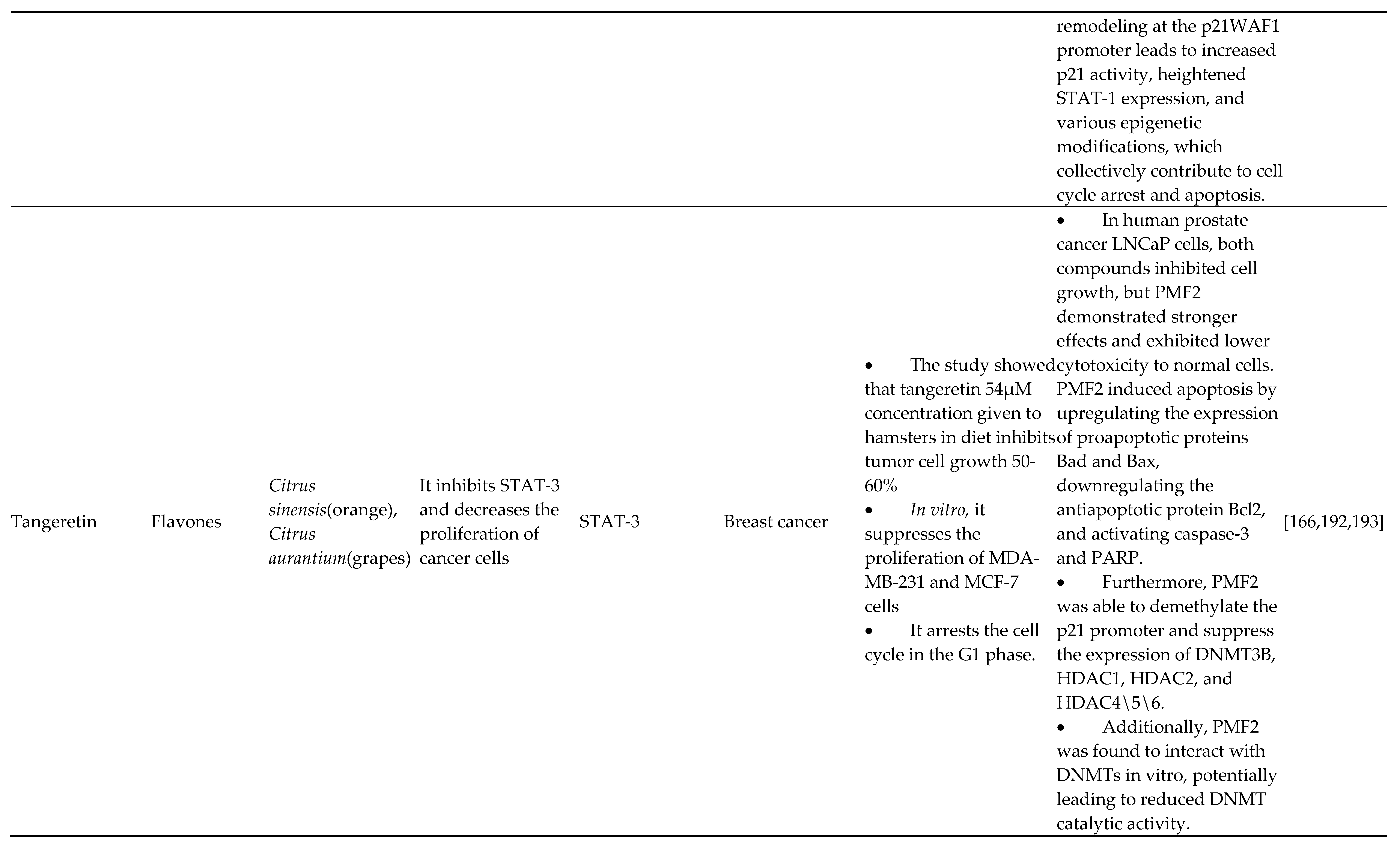

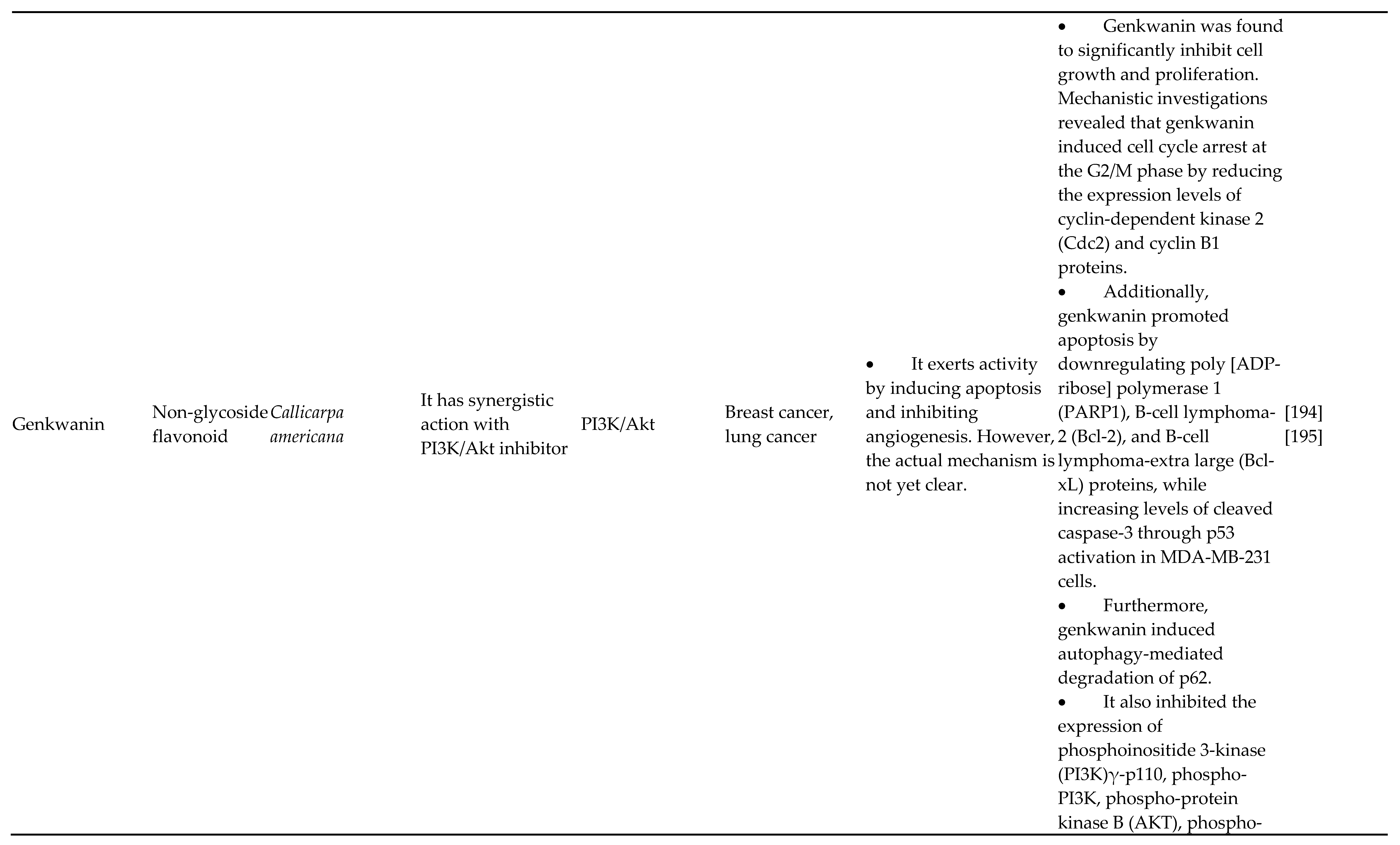

4.3. Flavones

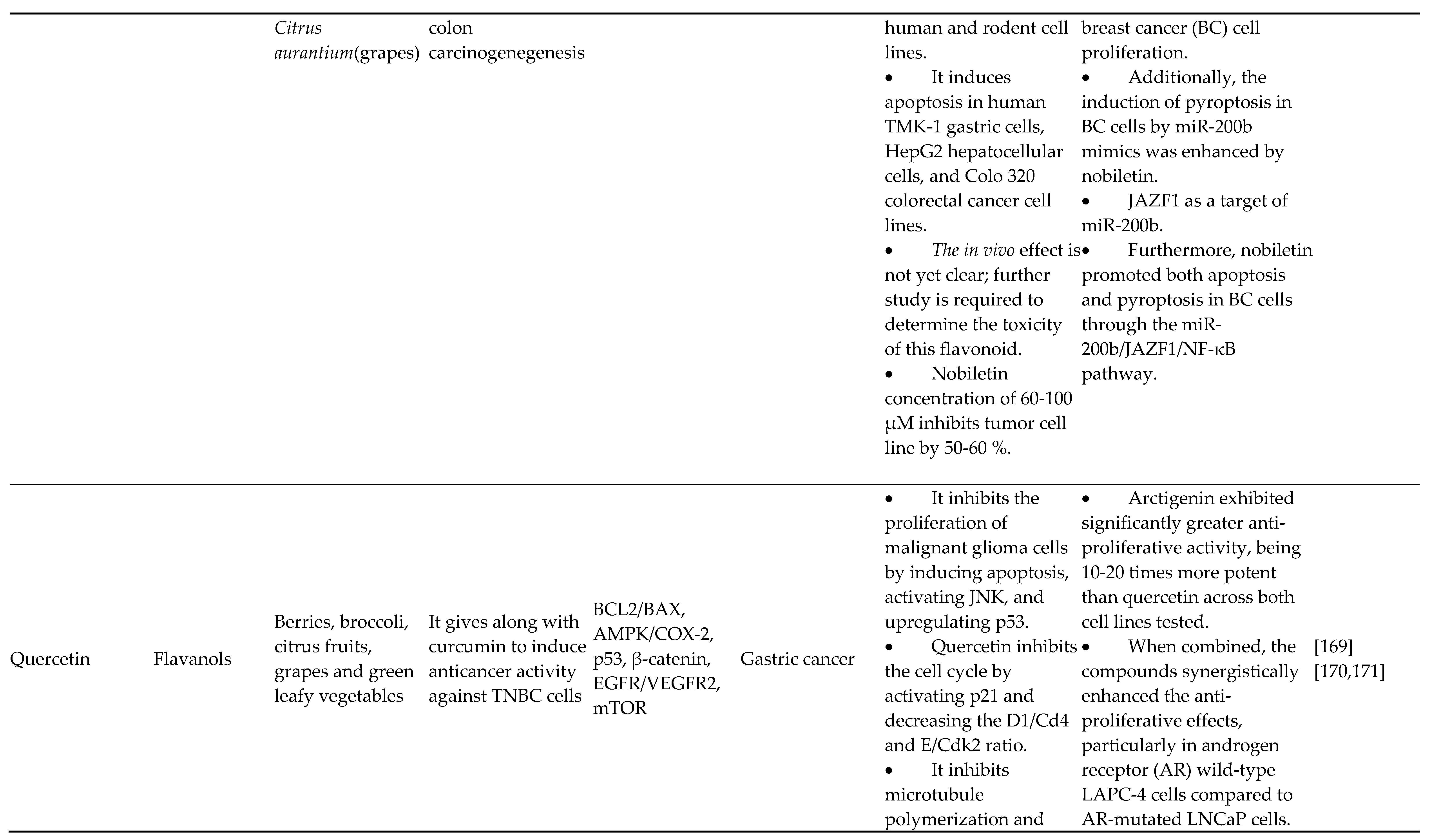

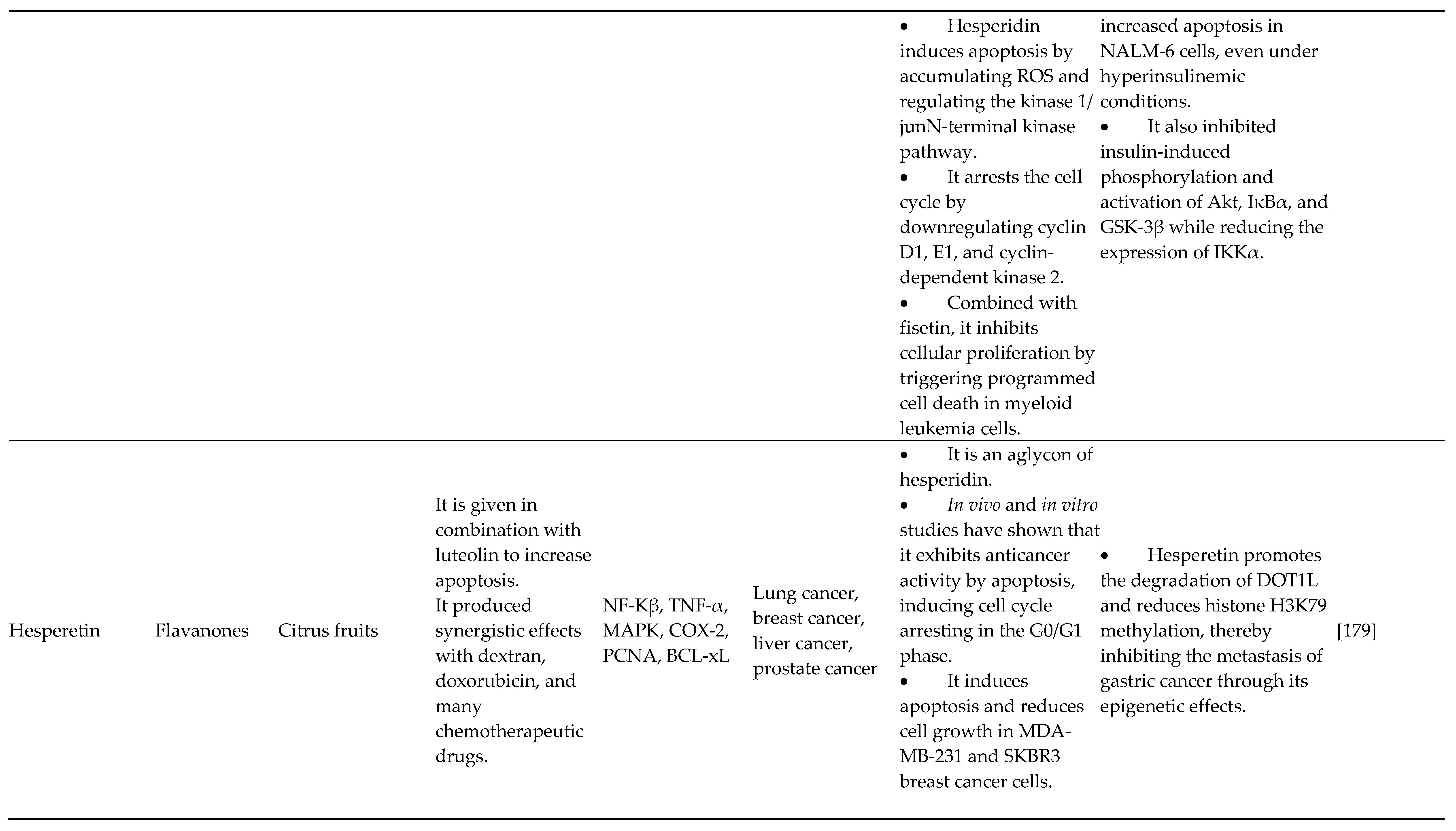

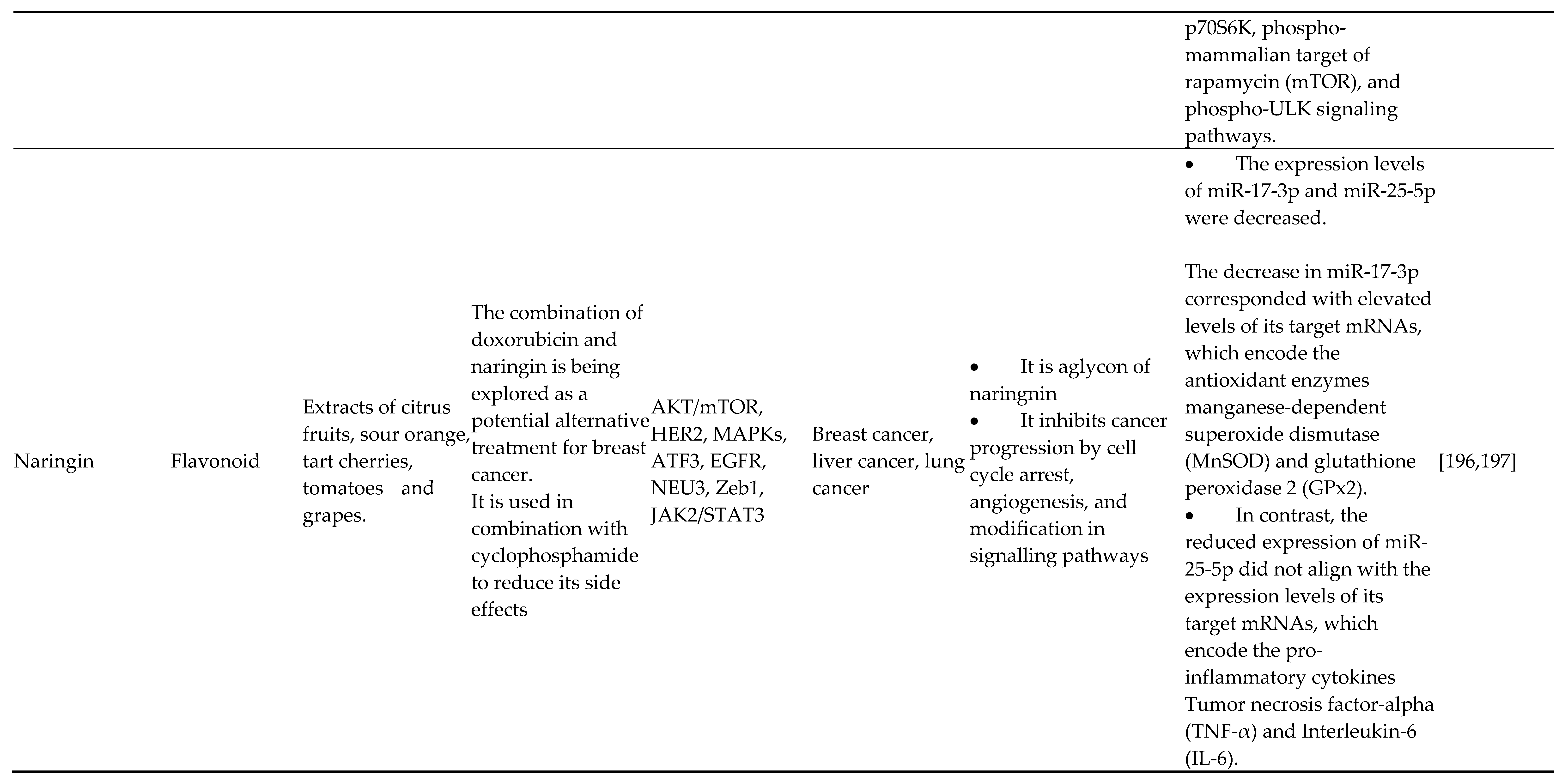

4.4. Flavanones

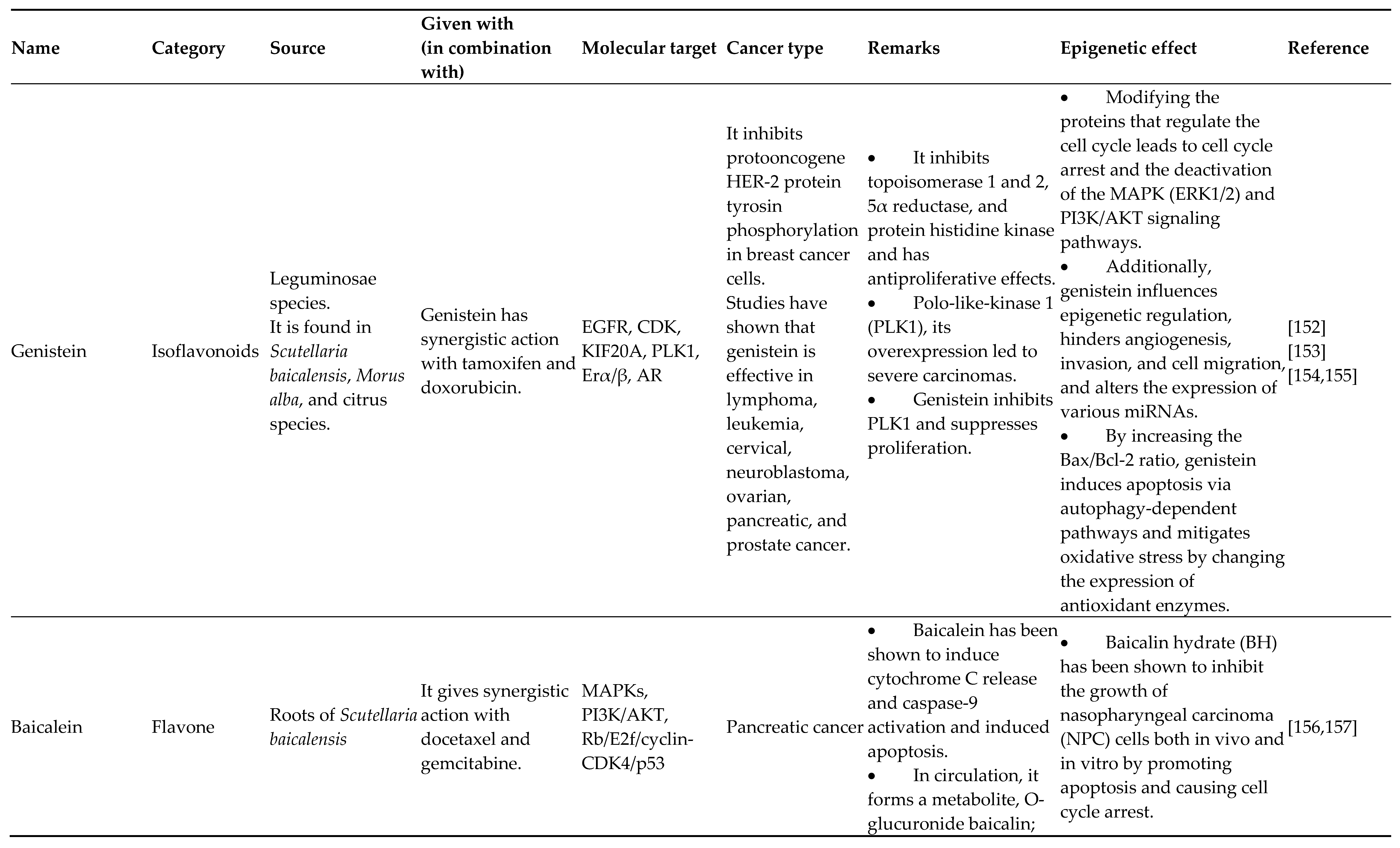

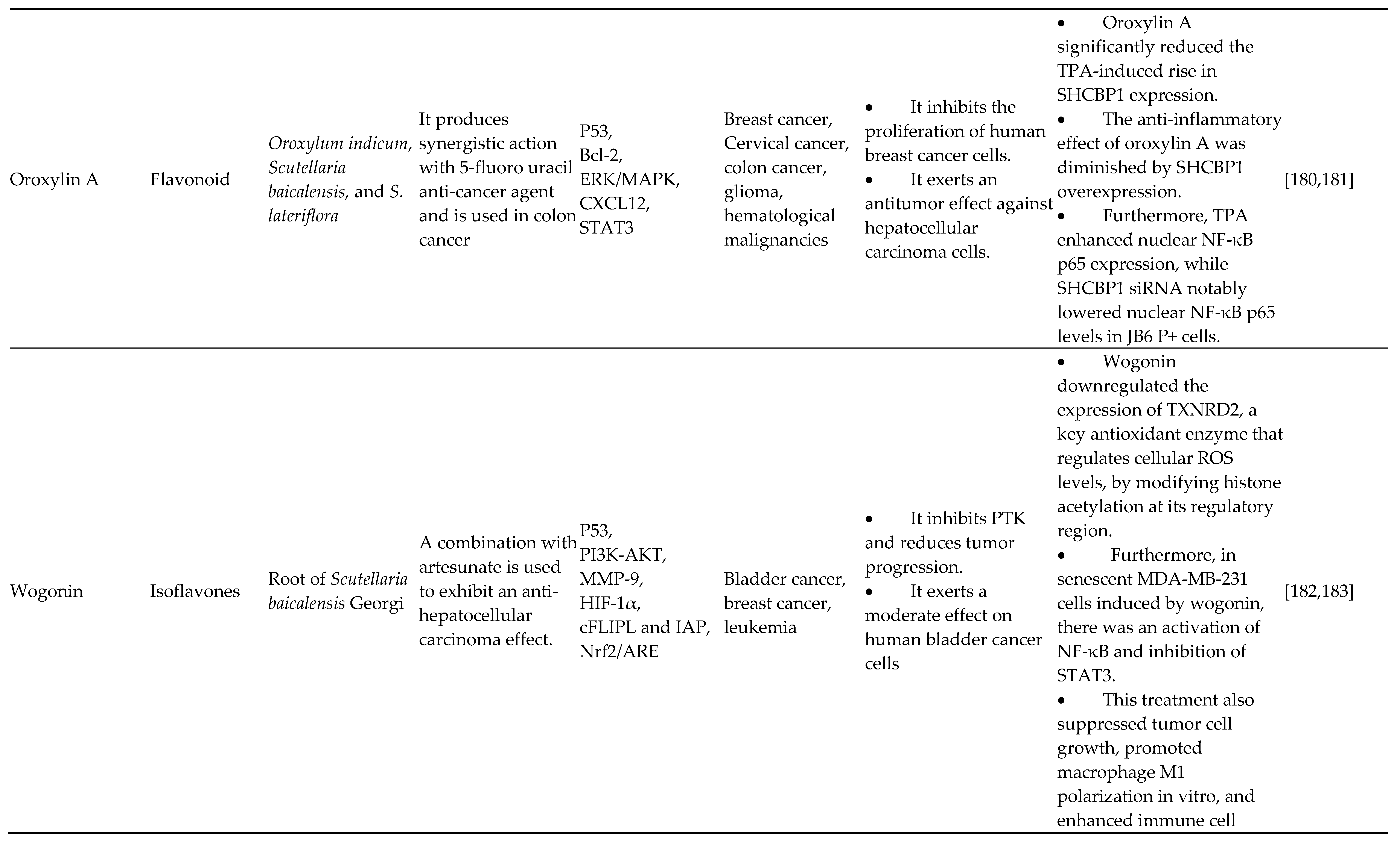

4.5. Isoflavones

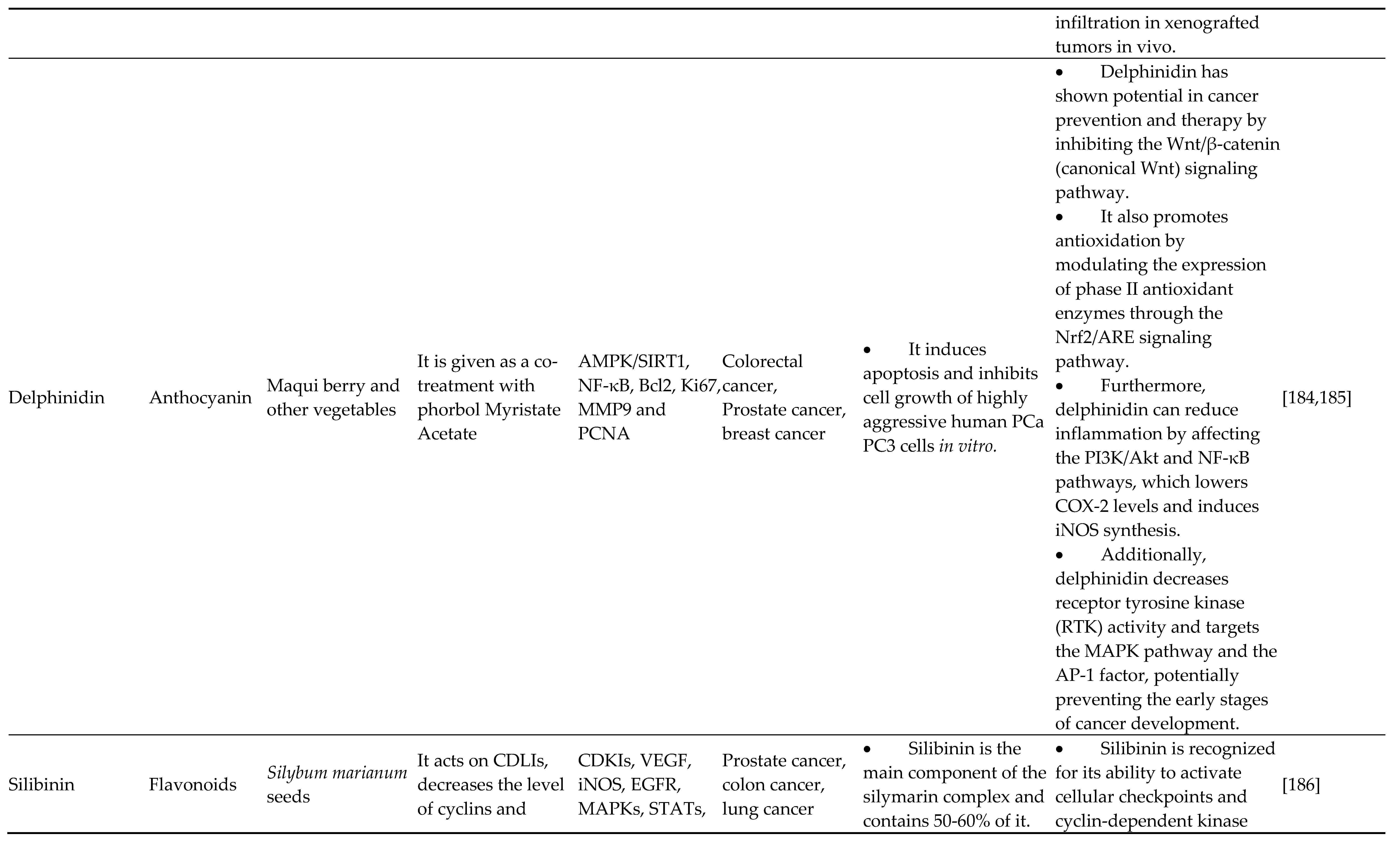

4.6. Anthocyanidins

5. Applications of Flavanoids in Cancer

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Competing Interests

Data Availability

Ethics Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent to Publish

References

- Weinhold B. Epigenetics: The Science of Change. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114. [CrossRef]

- Cheedipudi S, Genolet O, Dobreva G. Epigenetic inheritance of cell fates during embryonic development. Front Genet 2014;5. [CrossRef]

- Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, Jones PA. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature 2004;429:457–63. [CrossRef]

- Anand P, Kunnumakara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Lai OS, et al. Cancer is a Preventable Disease that Requires Major Lifestyle Changes. Pharm Res 2008;25:2097–116. [CrossRef]

- Cavalli G, Heard E. Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature 2019;571:489–99. [CrossRef]

- Taby R, Issa J-PJ. Cancer Epigenetics. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:376–92. [CrossRef]

- Bennett RL, Licht JD. Targeting Epigenetics in Cancer. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2018;58:187–207. [CrossRef]

- Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer Epigenetics: From Mechanism to Therapy. Cell 2012;150:12–27. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:7–33. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:12–49. [CrossRef]

- Yu W-D, Sun G, Li J, Xu J, Wang X. Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials of cancer immunotherapy in combination with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cancer Lett 2019;452:66–70. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Waschke BC, Woolaver RA, Chen SMY, Chen Z, Wang JH. HDAC inhibitors overcome immunotherapy resistance in B-cell lymphoma. Protein Cell 2020;11:472–82. [CrossRef]

- Lacouture M, Sibaud V. Toxic Side Effects of Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies Affecting the Skin, Oral Mucosa, Hair, and Nails. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018;19:31–9. [CrossRef]

- Shukla S, Meeran SM, Katiyar SK. Epigenetic regulation by selected dietary phytochemicals in cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Lett 2014;355:9–17. [CrossRef]

- Busch C, Burkard M, Leischner C, Lauer UM, Frank J, Venturelli S. Epigenetic activities of flavonoids in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Clin Epigenetics 2015;7:64. [CrossRef]

- Brower V. Epigenetics: Unravelling the cancer code. Nature 2011;471:S12–3. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Lu Q, Chang C. Epigenetics in Health and Disease, 2020, p. 3–55. [CrossRef]

- Ilango S, Paital B, Jayachandran P, Padma PR, Nirmaladevi R. Epigenetic alterations in cancer. Front Biosci Landmark Ed 2020;25:1058–109. [CrossRef]

- Gao F, Das SK. Epigenetic regulations through DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation: clues for early pregnancy in decidualization. Biomol Concepts 2014;5:95–107. [CrossRef]

- Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 2002;16:6–21. [CrossRef]

- Blake LE, Roux J, Hernando-Herraez I, Banovich NE, Perez RG, Hsiao CJ, et al. A comparison of gene expression and DNA methylation patterns across tissues and species. Genome Res 2020;30:250–62. [CrossRef]

- Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 2012;13:484–92. [CrossRef]

- Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2002;99:3740–5. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg MVC, Bourc’his D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019;20:590–607. [CrossRef]

- Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet 2007;8:286–98. [CrossRef]

- Chebly A, Ropio J, Peloponese J-M, Poglio S, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Cherrier F, et al. Exploring hTERT promoter methylation in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Mol Oncol 2022;16:1931–46. [CrossRef]

- Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene Silencing in Cancer in Association with Promoter Hypermethylation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2042–54. [CrossRef]

- Cheung H-H, Lee T-L, Rennert OM, Chan W-Y. DNA methylation of cancer genome. Birth Defects Res Part C Embryo Today Rev 2009;87:335–50. [CrossRef]

- Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38:23–38.

- Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res 2011;21:381–95. [CrossRef]

- Karlić R, Chung H-R, Lasserre J, Vlahoviček K, Vingron M. Histone modification levels are predictive for gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2010;107:2926–31. [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz-López KG, Castro-Muñoz LJ, Reyes-Hernández DO, García-Carrancá A, Manzo-Merino J. Lactate in the Regulation of Tumor Microenvironment and Therapeutic Approaches. Front Oncol 2019;9:1143. [CrossRef]

- Di Cerbo V, Schneider R. Cancers with wrong HATs: the impact of acetylation. Brief Funct Genomics 2013;12:231–43. [CrossRef]

- Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Villar-Garea A, Boix-Chornet M, Espada J, Schotta G, et al. Loss of acetylation at Lys16 and trimethylation at Lys20 of histone H4 is a common hallmark of human cancer. Nat Genet 2005;37:391–400. [CrossRef]

- Audia JE, Campbell RM. Histone Modifications and Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016;8:a019521. [CrossRef]

- Varier RA, Timmers HTM. Histone lysine methylation and demethylation pathways in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Rev Cancer 2011;1815:75–89. [CrossRef]

- Richon VM, Sandhoff TW, Rifkind RA, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor selectively induces p21 WAF1 expression and gene-associated histone acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2000;97:10014–9. [CrossRef]

- Rossetto D, Avvakumov N, Côté J. Histone phosphorylation. Epigenetics 2012;7:1098–108. [CrossRef]

- Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Sedelnikova OA, Solier S, et al. γH2AX and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2008;8:957–67. [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa R, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. Transcriptional regulation through noncoding RNAs and epigenetic modifications. RNA Biol 2009;6:233–6. [CrossRef]

- Statello L, Guo C-J, Chen L-L, Huarte M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021;22:96–118. [CrossRef]

- Mohr A, Mott J. Overview of MicroRNA Biology. Semin Liver Dis 2015;35:003–11. [CrossRef]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK-H, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 2009;19:92–105. [CrossRef]

- Peng Y, Croce CM. The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2016;1:15004. [CrossRef]

- Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs — microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:259–69. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Reyes E, González-Barrios R, Cisneros-Soberanis F, Herrera-Goepfert R, Pérez V, Cantú D, et al. Disruption of CTCF at the miR-125b1 locus in gynecological cancers. BMC Cancer 2012;12:40. [CrossRef]

- Ali Syeda Z, Langden SSS, Munkhzul C, Lee M, Song SJ. Regulatory Mechanism of MicroRNA Expression in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:1723. [CrossRef]

- Baer C, Claus R, Plass C. Genome-Wide Epigenetic Regulation of miRNAs in Cancer. Cancer Res 2013;73:473–7. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Chen X, Yu X, Tao Y, Bode AM, Dong Z, et al. Regulation of microRNAs by epigenetics and their interplay involved in cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2013;32:96. [CrossRef]

- Cammaerts S, Strazisar M, De Rijk P, Del Favero J. Genetic variants in microRNA genes: impact on microRNA expression, function, and disease. Front Genet 2015;6. [CrossRef]

- Marín-Béjar O, Marchese FP, Athie A, Sánchez Y, González J, Segura V, et al. Pint lincRNA connects the p53 pathway with epigenetic silencing by the Polycomb repressive complex 2. Genome Biol 2013;14:R104. [CrossRef]

- Vance KW, Ponting CP. Transcriptional regulatory functions of nuclear long noncoding RNAs. Trends Genet 2014;30:348–55. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Wang W, Zhu W, Dong J, Cheng Y, Yin Z, et al. Mechanisms and Functions of Long Non-Coding RNAs at Multiple Regulatory Levels. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:5573. [CrossRef]

- Hou Y, Zhang R, Sun X. Enhancer LncRNAs Influence Chromatin Interactions in Different Ways. Front Genet 2019;10. [CrossRef]

- Marchese FP, Raimondi I, Huarte M. The multidimensional mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function. Genome Biol 2017;18:206. [CrossRef]

- Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat Med 2015;21:1253–61. [CrossRef]

- Sinha S, Shukla S, Khan S, Farhan M, Kamal MA, Meeran SM. Telomeric Repeat Containing RNA (TERRA): Aging and Cancer. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2015;14:936–46. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zeng J, Chen W, Fan J, Hylemon PB, Zhou H. Long Noncoding RNA H19: A Novel Oncogene in Liver Cancer. Non-Coding RNA 2023;9:19. [CrossRef]

- de la Parra C, Castillo-Pichardo L, Cruz-Collazo A, Cubano L, Redis R, Calin GA, et al. Soy Isoflavone Genistein-Mediated Downregulation of miR-155 Contributes to the Anticancer Effects of Genistein. Nutr Cancer 2016;68:154–64. [CrossRef]

- Panche AN, Diwan AD, Chandra SR. Flavonoids: an overview. J Nutr Sci 2016;5:e47. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Pandey AK. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. Sci World J 2013;2013:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Woo H-H, Jeong BR, Hawes MC. Flavonoids: from cell cycle regulation to biotechnology. Biotechnol Lett 2005;27:365–74. [CrossRef]

- Pietta P-G. Flavonoids as Antioxidants. J Nat Prod 2000;63:1035–42. [CrossRef]

- Miron A, Aprotosoaie AC, Trifan A, Xiao J. Flavonoids as modulators of metabolic enzymes and drug transporters. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2017;1398:152–67. [CrossRef]

- Jucá MM, Cysne Filho FMS, de Almeida JC, Mesquita D da S, Barriga JR de M, Dias KCF, et al. Flavonoids: biological activities and therapeutic potential. Nat Prod Res 2020;34:692–705. [CrossRef]

- Khan H, Belwal T, Efferth T, Farooqi AA, Sanches-Silva A, Vacca RA, et al. Targeting epigenetics in cancer: therapeutic potential of flavonoids. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2021;61:1616–39. [CrossRef]

- Jiang W, Xia T, Liu C, Li J, Zhang W, Sun C. Remodeling the Epigenetic Landscape of Cancer—Application Potential of Flavonoids in the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Front Oncol 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Carlos-Reyes Á, López-González JS, Meneses-Flores M, Gallardo-Rincón D, Ruíz-García E, Marchat LA, et al. Dietary Compounds as Epigenetic Modulating Agents in Cancer. Front Genet 2019;10. [CrossRef]

- Abbas A, Hall JA, Patterson WL, Ho E, Hsu A, Al-Mulla F, et al. Sulforaphane modulates telomerase activity via epigenetic regulation in prostate cancer cell lines. Biochem Cell Biol 2016;94:71–81. [CrossRef]

- Abbas A, Patterson W, Georgel PT. The epigenetic potentials of dietary polyphenols in prostate cancer management. Biochem Cell Biol 2013;91:361–8. [CrossRef]

- Galati G, O’Brien PJ. Potential toxicity of flavonoids and other dietary phenolics: significance for their chemopreventive and anticancer properties. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;37:287–303. [CrossRef]

- Skibola CF, Smith MT. Potential health impacts of excessive flavonoid intake. Free Radic Biol Med 2000;29:375–83. [CrossRef]

- Singh BN, Shankar S, Srivastava RK. Green tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): Mechanisms, perspectives and clinical applications. Biochem Pharmacol 2011;82:1807–21. [CrossRef]

- Henning SM, Wang P, Carpenter CL, Heber D. Epigenetic effects of green tea polyphenols in cancer. Epigenomics 2013;5:729–41. [CrossRef]

- Giudice A, Montella M, Boccellino M, Crispo A, D’Arena G, Bimonte S, et al. Epigenetic Changes Induced by Green Tea Catechins a re Associated with Prostate Cancer. Curr Mol Med 2018;17. [CrossRef]

- Fang MZ, Wang Y, Ai N, Hou Z, Sun Y, Lu H, et al. Tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits DNA methyltransferase and reactivates methylation-silenced genes in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 2003;63:7563–70.

- Gupta S. Green tea polyphenols increase p53 transcriptional activity and acetylation by suppressing class�I histone deacetylases. Int J Oncol 2012. [CrossRef]

- Yoon H-G. EGCG suppresses prostate cancer cell growth modulating acetylation of androgen receptor by anti-histone acetyltransferase activity. Int J Mol Med 2012. [CrossRef]

- Lubecka K, Kaufman-Szymczyk A, Cebula-Obrzut B, Smolewski P, Szemraj J, Fabianowska-Majewska K. Novel Clofarabine-Based Combinations with Polyphenols Epigenetically Reactivate Retinoic Acid Receptor Beta, Inhibit Cell Growth, and Induce Apoptosis of Breast Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:3970. [CrossRef]

- KHAN MA, HUSSAIN A, SUNDARAM MK, ALALAMI U, GUNASEKERA D, RAMESH L, et al. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate reverses the expression of various tumor-suppressor genes by inhibiting DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylases in human cervical cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2015;33:1976–84. [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski O, Biesiekierska M, Balcerczyk A. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) Alters Histone Acetylation and Methylation and Impacts Chromatin Architecture Profile in Human Endothelial Cells. Molecules 2020;25:2326. [CrossRef]

- Kedhari Sundaram M, Haque S, Somvanshi P, Bhardwaj T, Hussain A. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits HeLa cells by modulation of epigenetics and signaling pathways. 3 Biotech 2020;10:484. [CrossRef]

- Kang Q, Zhang X, Cao N, Chen C, Yi J, Hao L, et al. EGCG enhances cancer cells sensitivity under 60Coγ radiation based on miR-34a/Sirt1/p53. Food Chem Toxicol 2019;133:110807. [CrossRef]

- Deb G, Shankar E, Thakur VS, Ponsky LE, Bodner DR, Fu P, et al. Green tea-induced epigenetic reactivation of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-3 suppresses prostate cancer progression through histone-modifying enzymes. Mol Carcinog 2019;58:1194–207. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Youness R, Amr Assal R, Mohamed Ezzat S, Zakaria Gad M, Abdel Motaal A. A methoxylated quercetin glycoside harnesses HCC tumor progression in a TP53/miR-15/miR-16 dependent manner. Nat Prod Res 2020;34:1475–80. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed F, Ijaz B, Ahmad Z, Farooq N, Sarwar MB, Husnain T. Modification of miRNA Expression through plant extracts and compounds against breast cancer: Mechanism and translational significance. Phytomedicine 2020;68:153168. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Zhang W, Chopra S, Kaur D, Wang H, Li M, et al. The Epigenetic Modification of Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) on Cancer. Curr Drug Targets 2020;21:1099–104. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Raza W, Parveen S, Meena A, Luqman S. Flavonoid display ability to target microRNAs in cancer pathogenesis. Biochem Pharmacol 2021;189:114409. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chen X, Jiang J, Wan X, Wang Y, Xu P. Epigallocatechin gallate reverses gastric cancer by regulating the long noncoding RNA LINC00511/miR-29b/KDM2A axis. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Basis Dis 2020;1866:165856. [CrossRef]

- MOSTAFA SM, GAMAL-ELDEEN AM, MAKSOUD NA EL, FAHMI AA. Epigallocatechin gallate-capped gold nanoparticles enhanced the tumor suppressors let-7a and miR-34a in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. An Acad Bras Ciênc 2020;92. [CrossRef]

- Zheng N-G, Wang J-L, Yang S-L, Wu J-L. Aberrant Epigenetic Alteration in Eca9706 Cells Modulated by Nanoliposomal Quercetin Combined with Butyrate Mediated via Epigenetic-NF-κB Signaling. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:4539–43. [CrossRef]

- Kedhari Sundaram M, Hussain A, Haque S, Raina R, Afroze N. Quercetin modifies 5′CpG promoter methylation and reactivates various tumor suppressor genes by modulating epigenetic marks in human cervical cancer cells. J Cell Biochem 2019;120:18357–69. [CrossRef]

- Nwaeburu CC, Abukiwan A, Zhao Z, Herr I. Quercetin-induced miR-200b-3p regulates the mode of self-renewing divisions in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer 2017;16:23. [CrossRef]

- Pham TND, Stempel S, Shields MA, Spaulding C, Kumar K, Bentrem DJ, et al. Quercetin Enhances the Anti-Tumor Effects of BET Inhibitors by Suppressing hnRNPA1. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:4293. [CrossRef]

- Zheng N-G, Wang J-L, Yang S-L, Wu J-L. Aberrant Epigenetic Alteration in Eca9706 Cells Modulated by Nanoliposomal Quercetin Combined with Butyrate Mediated via Epigenetic-NF-κB Signaling. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:4539–43. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Chen X, Li J, Xia C. Quercetin Antagonizes Esophagus Cancer by Modulating miR-1-3p/TAGLN2 Pathway-Dependent Growth and Metastasis. Nutr Cancer 2022;74:1872–81. [CrossRef]

- Russo GL, Ungaro P. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Quercetin and Other Flavonoids in Cancer Therapy and Prevention. Epigenetics Cancer Prev., Elsevier; 2019, p. 187–202. [CrossRef]

- Kedhari Sundaram M, Hussain A, Haque S, Raina R, Afroze N. Quercetin modifies 5′CpG promoter methylation and reactivates various tumor suppressor genes by modulating epigenetic marks in human cervical cancer cells. J Cell Biochem 2019;120:18357–69. [CrossRef]

- Pham TND, Stempel S, Shields MA, Spaulding C, Kumar K, Bentrem DJ, et al. Quercetin Enhances the Anti-Tumor Effects of BET Inhibitors by Suppressing hnRNPA1. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:4293. [CrossRef]

- Hu S, Cheng J, Zhao W, Zhao H. Quercetin induces apoptosis in meningioma cells through the miR-197/IGFBP5 cascade. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2020;80:103439. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Chen H. Genistein increases gene expression by demethylation of WNT5a promoter in colon cancer cell line SW1116. Anticancer Res 2010;30:4537–45.

- Zhang C, Hao Y, Sun Y, Liu P. Quercetin suppresses the tumorigenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma by regulating microRNA-22/WNT1/β-catenin axis. J Pharmacol Sci 2019;140:128–36. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chen X, Jiang J, Wan X, Wang Y, Xu P. Epigallocatechin gallate reverses gastric cancer by regulating the long noncoding RNA LINC00511/miR-29b/KDM2A axis. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Basis Dis 2020;1866:165856. [CrossRef]

- Ramos YAL, Souza OF, Novo MCT, Guimarães CFC, Popi AF. Quercetin shortened survival of radio-resistant B-1 cells in vitro and in vivo by restoring miR15a/16 expression. Oncotarget 2021;12:355–65. [CrossRef]

- Imran M, Saeed F, Gilani SA, Shariati MA, Imran A, Afzaal M, et al. Fisetin: An anticancer perspective. Food Sci Nutr 2021;9:3–16. [CrossRef]

- Berger A, Venturelli S, Kallnischkies M, Böcker A, Busch C, Weiland T, et al. Kaempferol, a new nutrition-derived pan-inhibitor of human histone deacetylases. J Nutr Biochem 2013;24:977–85. [CrossRef]

- Kim TW, Lee SY, Kim M, Cheon C, Ko S-G. Kaempferol induces autophagic cell death via IRE1-JNK-CHOP pathway and inhibition of G9a in gastric cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2018;9:875. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Liu C-F, Gao N, Zhao J, Xu J. RETRACTED: Kaempferol suppresses proliferation but increases apoptosis and autophagy by up-regulating microRNA-340 in human lung cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;108:809–16. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez S, Risolino M, Mandia N, Talotta F, Soini Y, Incoronato M, et al. miR-340 inhibits tumor cell proliferation and induces apoptosis by targeting multiple negative regulators of p27 in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2015;34:3240–50. [CrossRef]

- Imran M, Saeed F, Gilani SA, Shariati MA, Imran A, Afzaal M, et al. Fisetin: An anticancer perspective. Food Sci Nutr 2021;9:3–16. [CrossRef]

- Pal HC, Pearlman RL, Afaq F. Fisetin and Its Role in Chronic Diseases, 2016, p. 213–44. [CrossRef]

- Ding G, Xu X, Li D, Chen Y, Wang W, Ping D, et al. Fisetin inhibits proliferation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma by inducing DNA damage via RFXAP/KDM4A-dependent histone H3K36 demethylation. Cell Death Dis 2020;11:893. [CrossRef]

- Pandey M, Shukla S, Gupta S. Promoter demethylation and chromatin remodeling by green tea polyphenols leads to re-expression of GSTP1 in human prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer 2010:NA-NA. [CrossRef]

- Gao A-M, Zhang X-Y, Hu J-N, Ke Z-P. Apigenin sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells to doxorubic through regulating miR-520b/ATG7 axis. Chem Biol Interact 2018;280:45–50. [CrossRef]

- Tseng T-H, Chien M-H, Lin W-L, Wen Y-C, Chow J-M, Chen C-K, et al. Inhibition of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth by apigenin through induction of G2/M arrest and histone H3 acetylation-mediated p21 WAF1/CIP1 expression. Environ Toxicol 2017;32:434–44. [CrossRef]

- Chen X-J, Wu M-Y, Li D-H, You J. Apigenin inhibits glioma cell growth through promoting microRNA-16 and suppression of BCL-2 and nuclear factor-κB/MMP-9. Mol Med Rep 2016;14:2352–8. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Han X, Mo F, Zeng H, Zhao Y, Wang H, et al. Apigenin inhibits the growth of colorectal cancer through down-regulation of E2F1/3 by miRNA-215-5p. Phytomedicine 2021;89:153603. [CrossRef]

- Wu H-T, Lin J, Liu Y-E, Chen H-F, Hsu K-W, Lin S-H, et al. Luteolin suppresses androgen receptor-positive triple-negative breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by epigenetic regulation of MMP9 expression via the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2021;81:153437. [CrossRef]

- Lin D, Kuang G, Wan J, Zhang X, Li H, Gong X, et al. Luteolin suppresses the metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer by reversing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via downregulation of β-catenin expression. Oncol Rep 2017;37:895–902. [CrossRef]

- Krifa M, Leloup L, Ghedira K, Mousli M, Chekir-Ghedira L. Luteolin Induces Apoptosis in BE Colorectal Cancer Cells by Downregulating Calpain, UHRF1, and DNMT1 Expressions. Nutr Cancer 2014;66:1220–7. [CrossRef]

- Markaverich BM, Vijjeswarapu M, Shoulars K, Rodriguez M. Luteolin and gefitinib regulation of EGF signaling pathway and cell cycle pathway genes in PC-3 human prostate cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;122:219–31. [CrossRef]

- Shoulars K, Rodriguez MA, Thompson T, Markaverich BM. Regulation of cell cycle and RNA transcription genes identified by microarray analysis of PC-3 human prostate cancer cells treated with luteolin. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;118:41–50. [CrossRef]

- Farooqi AA, Butt G, El-Zahaby SA, Attar R, Sabitaliyevich UY, Jovic JJ, et al. Luteolin mediated targeting of protein network and microRNAs in different cancers: Focus on JAK-STAT, NOTCH, mTOR and TRAIL-mediated signaling pathways. Pharmacol Res 2020;160:105188. [CrossRef]

- Mohr A, Mott J. Overview of MicroRNA Biology. Semin Liver Dis 2015;35:003–11. [CrossRef]

- Lai W, Jia J, Yan B, Jiang Y, Shi Y, Chen L, et al. Baicalin hydrate inhibits cancer progression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by affecting genome instability and splicing. Oncotarget 2018;9:901–14. [CrossRef]

- Bijak M. Silybin, a Major Bioactive Component of Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum L. Gaernt.)—Chemistry, Bioavailability, and Metabolism. Mol J Synth Chem Nat Prod Chem 2017;22:1942. [CrossRef]

- Barreca D, Mandalari G, Calderaro A, Smeriglio A, Trombetta D, Felice MR, et al. Citrus Flavones: An Update on Sources, Biological Functions, and Health Promoting Properties. Plants 2020;9:288. [CrossRef]

- Khan H, Belwal T, Efferth T, Farooqi AA, Sanches-Silva A, Vacca RA, et al. Targeting epigenetics in cancer: therapeutic potential of flavonoids. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2021;61:1616–39. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Sheng H, Zheng F, Zhang F. Hesperetin promotes DOT1L degradation and reduces histone H3K79 methylation to inhibit gastric cancer metastasis. Phytomedicine 2021;84:153499. [CrossRef]

- Mateen S, Raina K, Agarwal C, Chan D, Agarwal R. Silibinin Synergizes with Histone Deacetylase and DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors in Upregulating E-cadherin Expression Together with Inhibition of Migration and Invasion of Human Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2013;345:206–14. [CrossRef]

- Anestopoulos I, Sfakianos A, Franco R, Chlichlia K, Panayiotidis M, Kroll D, et al. A Novel Role of Silibinin as a Putative Epigenetic Modulator in Human Prostate Carcinoma. Molecules 2016;22:62. [CrossRef]

- Hossainzadeh S, Ranji N, Naderi Sohi A, Najafi F. Silibinin encapsulation in polymersome: A promising anticancer nanoparticle for inducing apoptosis and decreasing the expression level of miR-125b/miR-182 in human breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol 2019;234:22285–98. [CrossRef]

- Ling D, Marshall GM, Liu PY, Xu N, Nelson CA, Iismaa SE, et al. Enhancing the anticancer effect of the histone deacetylase inhibitor by activating transglutaminase. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:3278–87. [CrossRef]

- Panche AN, Diwan AD, Chandra SR. Flavonoids: an overview. J Nutr Sci 2016;5:e47. [CrossRef]

- Taku K, Melby MK, Nishi N, Omori T, Kurzer MS. Soy isoflavones for osteoporosis: An evidence-based approach. Maturitas 2011;70:333–8. [CrossRef]

- Vitale DC, Piazza C, Melilli B, Drago F, Salomone S. Isoflavones: estrogenic activity, biological effect and bioavailability. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 2013;38:15–25. [CrossRef]

- Qin Y, Niu K, Zeng Y, Liu P, Yi L, Zhang T, et al. Isoflavones for hypercholesterolaemia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013. [CrossRef]

- Sathyapalan T, Aye M, Rigby AS, Thatcher NJ, Dargham SR, Kilpatrick ES, et al. Soy isoflavones improve cardiovascular disease risk markers in women during the early menopause. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2018;28:691–7. [CrossRef]

- Křížová L, Dadáková K, Kašparovská J, Kašparovský T. Isoflavones. Molecules 2019;24:1076. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Zorita S, González-Arceo M, Fernández-Quintela A, Eseberri I, Trepiana J, Portillo MP. Scientific Evidence Supporting the Beneficial Effects of Isoflavones on Human Health. Nutrients 2020;12:3853. [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo C, Russo GL, Orhan IE, Habtemariam S, Daglia M, Sureda A, et al. Genistein and Cancer: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Adv Nutr 2015;6:408–19. [CrossRef]

- Adjakly M, Bosviel R, Rabiau N, Boiteux J-P, Bignon Y-J, Guy L, et al. DNA methylation and soy phytoestrogens: quantitative study in DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate cancer cell lines. Epigenomics 2011;3:795–803. [CrossRef]

- Karsli-Ceppioglu S, Ngollo M, Adjakly M, Dagdemir A, Judes G, Lebert A, et al. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Modified by Soy Phytoestrogens: Role for Epigenetic Therapeutics in Prostate Cancer? OMICS J Integr Biol 2015;19:209–19. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka MI-SPDPKMSYHVSSMY, Yamamura RDS. Genistein Represses HOTAIR/Chromatin Remodeling Pathways to Suppress Kidney Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem 2020;54:53–70. [CrossRef]

- Allred CD. Dietary genistin stimulates growth of estrogen-dependent breast cancer tumors similar to that observed with genistein. Carcinogenesis 2001;22:1667–73. [CrossRef]

- Khoo HE, Azlan A, Tang ST, Lim SM. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutr Res 2017;61:1361779. [CrossRef]

- Kuo H-CD, Wu R, Li S, Yang AY, Kong A-N. Anthocyanin Delphinidin Prevents Neoplastic Transformation of Mouse Skin JB6 P+ Cells: Epigenetic Re-activation of Nrf2-ARE Pathway. AAPS J 2019;21:83. [CrossRef]

- Jeong M-H, Ko H, Jeon H, Sung G-J, Park S-Y, Jun WJ, et al. Delphinidin induces apoptosis via cleaved HDAC3-mediated p53 acetylation and oligomerization in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016;7:56767–80. [CrossRef]

- Han B, Peng X, Cheng D, Zhu Y, Du J, Li J, et al. Delphinidin suppresses breast carcinogenesis through the HOTAIR /micro RNA -34a axis. Cancer Sci 2019;110:3089–97. [CrossRef]

- Huang C-C, Hung C-H, Hung T-W, Lin Y-C, Wang C-J, Kao S-H. Dietary delphinidin inhibits human colorectal cancer metastasis associating with upregulation of miR-204-3p and suppression of the integrin/FAK axis. Sci Rep 2019;9:18954. [CrossRef]

- Kopustinskiene DM, Jakstas V, Savickas A, Bernatoniene J. Flavonoids as Anticancer Agents. Nutrients 2020;12. [CrossRef]

- Chae H-S, Xu R, Won J-Y, Chin Y-W, Yim H. Molecular Targets of Genistein and Its Related Flavonoids to Exert Anticancer Effects. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:2420. [CrossRef]

- BANERJEE S, LI Y, WANG Z, SARKAR FH. MULTI-TARGETED THERAPY OF CANCER BY GENISTEIN. Cancer Lett 2008;269:226–42. [CrossRef]

- Sanaei M, Kavoosi F, Atashpour S, Haghighat S. Effects of Genistein and Synergistic Action in Combination with Tamoxifen on the HepG2 Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP 2017;18:2381–5. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou EK, Gioxari A, Dimitriou M, Panoutsopoulos GI, Panagiotopoulos AA. Molecular Pathways of Genistein Activity in Breast Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:5556. [CrossRef]

- Donald G, Hertzer K, Eibl G. Baicalein – An Intriguing Therapeutic Phytochemical in Pancreatic Cancer. Curr Drug Targets 2012;13:1772–6.

- Lai W, Jia J, Yan B, Jiang Y, Shi Y, Chen L, et al. Baicalin hydrate inhibits cancer progression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by affecting genome instability and splicing. Oncotarget 2018;9:901–14. [CrossRef]

- Yan X, Qi M, Li P, Zhan Y, Shao H. Apigenin in cancer therapy: anti-cancer effects and mechanisms of action. Cell Biosci 2017;7:50. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Xin Y, Diao Y, Lu C, Fu J, Luo L, et al. Synergistic Effects of Apigenin and Paclitaxel on Apoptosis of Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e29169. [CrossRef]

- Tseng T, Chien M, Lin W, Wen Y, Chow J, Chen C, et al. Inhibition of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth by apigenin through induction of G2/M arrest and histone H3 acetylation-mediated p21 WAF1/CIP1 expression. Environ Toxicol 2017;32:434–44. [CrossRef]

- Seelinger G, Merfort I, Wölfle U, Schempp CM. Anti-carcinogenic Effects of the Flavonoid Luteolin. Molecules 2008;13:2628–51. [CrossRef]

- Jang CH, Moon N, Lee J, Kwon MJ, Oh J, Kim J-S. Luteolin Synergistically Enhances Antitumor Activity of Oxaliplatin in Colorectal Carcinoma via AMPK Inhibition. Antioxidants 2022;11:626. [CrossRef]

- Zuo Q, Wu R, Xiao X, Yang C, Yang Y, Wang C, et al. The dietary flavone luteolin epigenetically activates the Nrf2 pathway and blocks cell transformation in human colorectal cancer HCT116 cells. J Cell Biochem 2018;119:9573–82. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimizu N, Otani Y, Saikawa Y, Kubota T, Yoshida M, Furukawa T, et al. Anti-tumour effects of nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid, on gastric cancer include: antiproliferative effects, induction of apoptosis and cell cycle deregulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20 Suppl 1:95–101. [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi H, Asamoto M, Tujimura K, Hokaiwado N, Takahashi S, Ogawa K, et al. Inhibition of cell proliferation by nobiletin, a dietary phytochemical, associated with apoptosis and characteristic gene expression, but lack of effect on early rat hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo. Cancer Sci 2004;95:936–42. [CrossRef]

- Morley KL, Ferguson PJ, Koropatnick J. Tangeretin and nobiletin induce G1 cell cycle arrest but not apoptosis in human breast and colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2007;251:168–78. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Song M, Qiu P, Rakariyatham K, Li F, Gao Z, et al. Synergistic chemopreventive effects of nobiletin and atorvastatin on colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2017;38:455–64. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Jian W, Li Y, Zhang J. Nobiletin promotes the pyroptosis of breast cancer via regulation of miR -200b/ JAZF1 axis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2021;37:572–82. [CrossRef]

- Mirazimi SMA, Dashti F, Tobeiha M, Shahini A, Jafari R, Khoddami M, et al. Application of Quercetin in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Cancers. Front Pharmacol 2022;13.

- Kundur S, Prayag A, Selvakumar P, Nguyen H, McKee L, Cruz C, et al. Synergistic anticancer action of quercetin and curcumin against triple-negative breast cancer cell lines. J Cell Physiol 2019;234:11103–18. [CrossRef]

- Wang P, Phan T, Gordon D, Chung S, Henning SM, Vadgama JV. Arctigenin in combination with quercetin synergistically enhances the antiproliferative effect in prostate cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015;59:250–61. [CrossRef]

- Ponte LGS, Pavan ICB, Mancini MCS, da Silva LGS, Morelli AP, Severino MB, et al. The Hallmarks of Flavonoids in Cancer. Molecules 2021;26:2029. [CrossRef]

- Qattan MY, Khan MI, Alharbi SH, Verma AK, Al-Saeed FA, Abduallah AM, et al. Therapeutic Importance of Kaempferol in the Treatment of Cancer through the Modulation of Cell Signalling Pathways. Molecules 2022;27:8864. [CrossRef]

- Kim TW, Lee SY, Kim M, Cheon C, Ko S-G. Kaempferol induces autophagic cell death via IRE1-JNK-CHOP pathway and inhibition of G9a in gastric cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2018;9:875. [CrossRef]

- Javed Z, Khan K, Herrera-Bravo J, Naeem S, Iqbal MJ, Raza Q, et al. Myricetin: targeting signaling networks in cancer and its implication in chemotherapy. Cancer Cell Int 2022;22:239. [CrossRef]

- Phillips PA, Sangwan V, Borja-Cacho D, Dudeja V, Vickers SM, Saluja AK. Myricetin induces pancreatic cancer cell death via the induction of apoptosis and inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway. Cancer Lett 2011;308:181–8. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal V, Tuli HS, Thakral F, Singhal P, Aggarwal D, Srivastava S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of action of hesperidin in cancer: Recent trends and advancements. Exp Biol Med 2020;245:486–97. [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi R, Cheraghpour M, Homayounfar R, Nazari M, Nasrollahzadeh J, Davoodi SH. Hesperidin inhibits insulin-induced phosphoinositide 3–kinase/Akt activation in human pre-B cell line NALM-6. J Cancer Res Ther 2018;14:503–8. [CrossRef]

- Sohel M, Sultana H, Sultana T, Al Amin Md, Aktar S, Ali MdC, et al. Chemotherapeutic potential of hesperetin for cancer treatment, with mechanistic insights: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2022;8:e08815. [CrossRef]

- Sajeev A, Hegde M, Girisa S, Devanarayanan TN, Alqahtani MS, Abbas M, et al. Oroxylin A: A Promising Flavonoid for Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases. Biomolecules 2022;12:1185. [CrossRef]

- Huang H, Cai H, Zhang L, Hua Z, Shi J, Wei Y. Oroxylin A inhibits carcinogen-induced skin tumorigenesis through inhibition of inflammation by regulating SHCBP1 in mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2020;80:106123. [CrossRef]

- Tai MC, Tsang SY, Chang LYF, Xue H. Therapeutic Potential of Wogonin: A Naturally Occurring Flavonoid. CNS Drug Rev 2005;11:141–50. [CrossRef]

- Yang D, Guo Q, Liang Y, Zhao Y, Tian X, Ye Y, et al. Wogonin induces cellular senescence in breast cancer via suppressing TXNRD2 expression. Arch Toxicol 2020;94:3433–47. [CrossRef]

- Im N-K, Jang WJ, Jeong C-H, Jeong G-S. Delphinidin Suppresses PMA-Induced MMP-9 Expression by Blocking the NF-κB Activation Through MAPK Signaling Pathways in MCF-7 Human Breast Carcinoma Cells. J Med Food 2014;17:855–61. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Choi H-K, Kim Y-K, Lee H-J. Delphinidin and Its Glycosides’ War on Cancer: Preclinical Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:11500. [CrossRef]

- Deep G, Agarwal R. Anti-metastatic Efficacy of Silibinin: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential against Cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2010;29:447–63. [CrossRef]

- Du G-J, Zhang Z, Wen X-D, Yu C, Calway T, Yuan C-S, et al. Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) Is the Most Effective Cancer Chemopreventive Polyphenol in Green Tea. Nutrients 2012;4:1679–91. [CrossRef]

- Eom D-W, Lee JH, Kim Y-J, Hwang GS, Kim S-N, Kwak JH, et al. Synergistic effect of curcumin on epigallocatechin gallate-induced anticancer action in PC3 prostate cancer cells. BMB Rep 2015;48:461–6. [CrossRef]

- Henning SM, Wang P, Carpenter CL, Heber D. Epigenetic Effects of Green Tea Polyphenols in Cancer. Epigenomics 2013;5:729–41. [CrossRef]

- Maasomi ZJ, Soltanahmadi YP, Dadashpour M, Alipour S, Abolhasani S, Zarghami N. Synergistic Anticancer Effects of Silibinin and Chrysin in T47D Breast Cancer Cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP 2017;18:1283–7. [CrossRef]

- Pal-Bhadra M, Ramaiah MJ, Reddy TL, Krishnan A, Pushpavalli S, Babu KS, et al. Plant HDAC inhibitor chrysin arrest cell growth and induce p21 WAF1 by altering chromatin of STAT response element in A375 cells. BMC Cancer 2012;12:180. [CrossRef]

- Ko Y-C, Choi HS, Liu R, Kim J-H, Kim S-L, Yun B-S, et al. Inhibitory Effects of Tangeretin, a Citrus Peel-Derived Flavonoid, on Breast Cancer Stem Cell Formation through Suppression of Stat3 Signaling. Molecules 2020;25:2599. [CrossRef]

- Wei G-J, Chao Y-H, Tung Y-C, Wu T-Y, Su Z-Y. A Tangeretin Derivative Inhibits the Growth of Human Prostate Cancer LNCaP Cells by Epigenetically Restoring p21 Gene Expression and Inhibiting Cancer Stem-like Cell Proliferation. AAPS J 2019;21:86. [CrossRef]

- Porras G, Bacsa J, Tang H, Quave CL. Characterization and Structural Analysis of Genkwanin, a Natural Product from Callicarpa americana. Crystals 2019;9:491. [CrossRef]

- Wei C, Lu J, Zhang Z, Hua F, Chen Y, Shen Z. Genkwanin attenuates lung cancer development by repressing proliferation and invasion via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. Mater Express 2021;11:319–25.

- Curti V, Di Lorenzo A, Rossi D, Martino E, Capelli E, Collina S, et al. Enantioselective Modulatory Effects of Naringenin Enantiomers on the Expression Levels of miR-17-3p Involved in Endogenous Antioxidant Defenses. Nutrients 2017;9:215. [CrossRef]

- Effat H, Abosharaf HA, Radwan AM. Combined effects of naringin and doxorubicin on the JAK/STAT signaling pathway reduce the development and spread of breast cancer cells. Sci Rep 2024;14:2824. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).