Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Prisoner’s Dilemma Game

2.4. Behavior Analysis

2.4.1. FACS Coding

2.4.2. Gaze Direction Coding

2.6. Artifact Reduction Methods for fNIRS Data

2.7. Analysis of IBS

3. Results

3.1. Linear Regression of Duchenne Smiling with Gaze and Cooperativeness and Cooperative Behavior

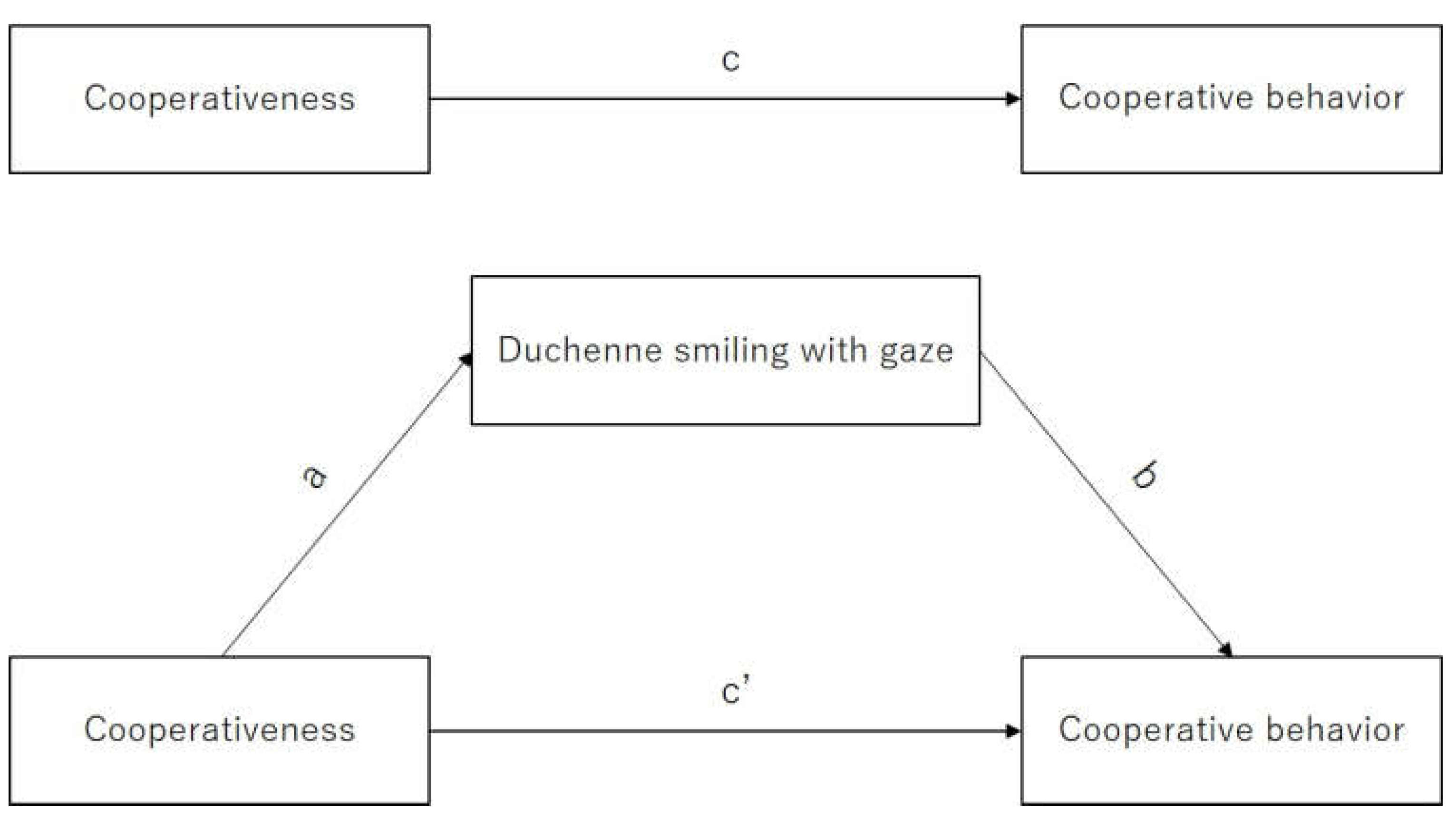

3.2. Estimating Mediating Effect of Duchenne Smiling with Gaze on Cooperative Behavior

3.3. IBS Analysis

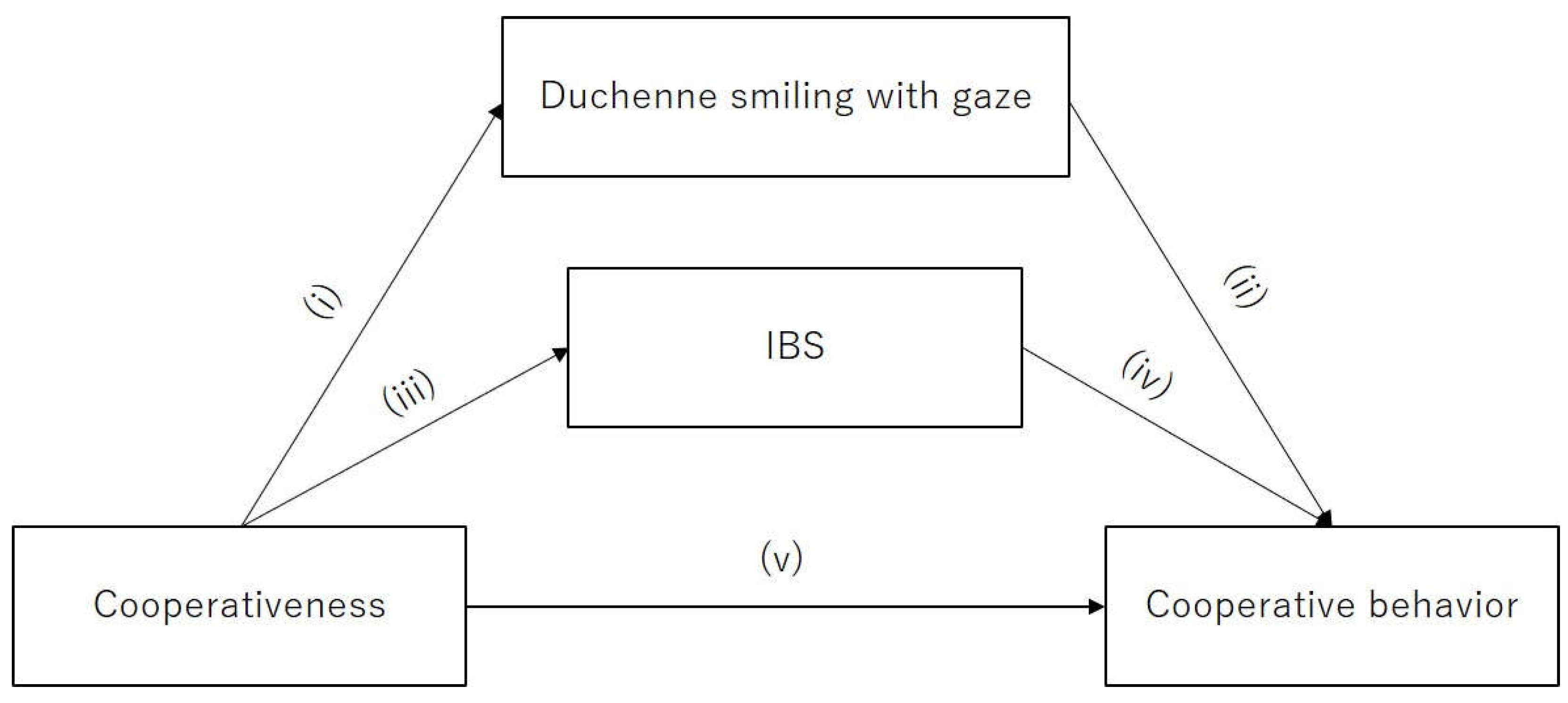

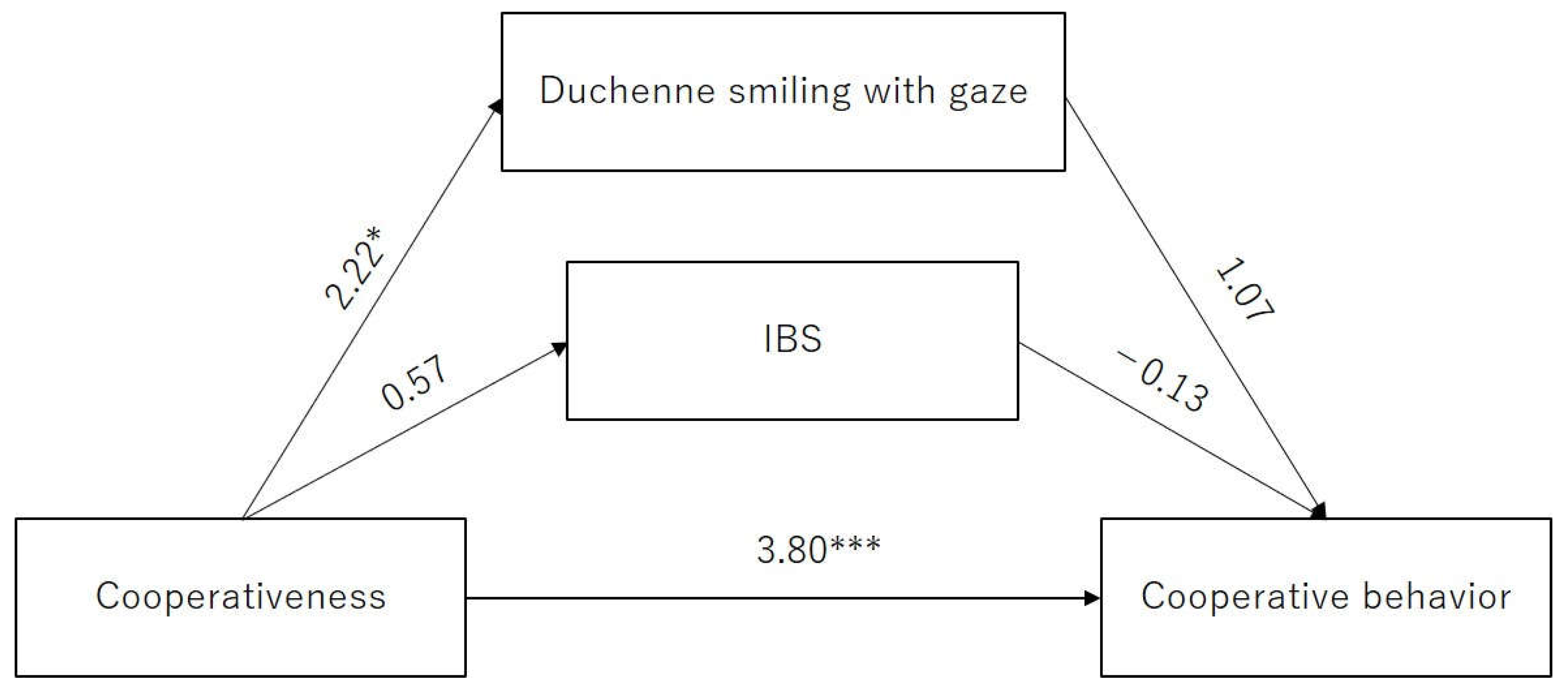

3.4. Path Analysis for Examining the Role of IBS in Cooperative Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nowak, M.A. Five Rules for the Evolution of Cooperation. Science 2006, 314, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommet, N.; Weissman, D.L.; Elliot, A.J. Income Inequality Predicts Competitiveness and Cooperativeness at School. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Au, W.-T.; Jiang, F.; Xie, X.; Yam, P. Cooperativeness and Competitiveness as Two Distinct Constructs: Validating the Cooperative and Competitive Personality Scale in a Social Dilemma Context. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, T.; Mifune, N.; Li, Y.; Shinada, M.; Hashimoto, H.; Horita, Y.; Miura, A.; Inukai, K.; Tanida, S.; Kiyonari, T.; et al. Is Behavioral Pro-Sociality Game-Specific? Pro-Social Preference and Expectations of pro-Sociality. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 120, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.I.; Zeglen, K.N.; Schmidt, K.L. Facial Expressions as Honest Signals of Cooperative Intent in a One-Shot Anonymous Prisoner’s Dilemma Game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2012, 33, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehu, M.; Grammer, K.; Dunbar, R.I.M. Smiles When Sharing. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2007, 28, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.M.; Palameta, B.; Moore, C. Are There Nonverbal Cues to Commitment? An Exploratory Study Using the Zero-Acquaintance Video Presentation Paradigm. Evol. Psychol. 2003, 1, 147470490300100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.; Miles, L.; Macrae, C.N. Why Are You Smiling at Me? Social Functions of Enjoyment and Non-Enjoyment Smiles. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Eckel, C.C.; Kacelnik, A.; Wilson, R.K. The Value of a Smile: Game Theory with a Human Face. J. Econ. Psychol. 2001, 22, 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehu, M.; Little, A.; Dunbar, R. Duchenne Smiles and the Perception of Generosity and Sociability in Faces. J. Evol. Psychol. 2007, 5, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnery, S.D.; Hall, J.A.; Ruben, M.A. The Deliberate Duchenne Smile: Individual Differences in Expressive Control. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2013, 37, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, R.W.; Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Voluntary Facial Action Generates Emotion-Specific Autonomic Nervous System Activity. Psychophysiology 1990, 27, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasello, M.; Hare, B.; Lehmann, H.; Call, J. Reliance on Head versus Eyes in the Gaze Following of Great Apes and Human Infants: The Cooperative Eye Hypothesis. J. Hum. Evol. 2007, 52, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, N.J. The Eyes Have It: The Neuroethology, Function and Evolution of Social Gaze. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000, 24, 581–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langton, S.R.H.; Watt, R.J.; Bruce, V. Do the Eyes Have It? Cues to the Direction of Social Attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.B.; Kleck, R.E. Effects of Direct and Averted Gaze on the Perception of Facially Communicated Emotion. Emotion 2005, 5, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinke, C.L. Gaze and Eye Contact: A Research Review. Psychol. Bull. 1986, 100, 78–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holroyd, C.B. Interbrain Synchrony: On Wavy Ground. Trends Neurosci. 2022, 45, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsen, B.A.; Sumich, A.; Kasabov, N.; Liang, S.H.Y.; Wang, G.Y. What Has Social Neuroscience Learned from Hyperscanning Studies of Spoken Communication? A Systematic Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 132, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C.S.; Choo, S.; Huang, J.; Park, J. Brain-to-Brain Neural Synchrony During Social Interactions: A Systematic Review on Hyperscanning Studies. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, U.; De Felice, S.; Pinti, P.; Zhang, X.; Noah, J.; Ono, Y.; Burgess, P.W.; Hamilton, A.; Hirsch, J.; Tachtsidis, I. Quantification of Inter-Brain Coupling: A Review of Current Methods Used in Haemodynamic and Electrophysiological Hyperscanning Studies. NeuroImage 2023, 280, 120354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeszumski, A.; Eustergerling, S.; Lang, A.; Menrath, D.; Gerstenberger, M.; Schuberth, S.; Schreiber, F.; Rendon, Z.Z.; König, P. Hyperscanning: A Valid Method to Study Neural Inter-Brain Underpinnings of Social Interaction. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozawa, T.; Sakaki, K.; Ikeda, S.; Jeong, H.; Yamazaki, S.; Kawata, K.H. dos S.; Kawata, N.Y. dos S.; Sasaki, Y.; Kulason, K.; Hirano, K.; et al. Prior Physical Synchrony Enhances Rapport and Inter-Brain Synchronization during Subsequent Educational Communication. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeszumski, A.; Liang, S.H.-Y.; Dikker, S.; König, P.; Lee, C.-P.; Koole, S.L.; Kelsen, B. Cooperative Behavior Evokes Interbrain Synchrony in the Prefrontal and Temporoparietal Cortex: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of fNIRS Hyperscanning Studies. eneuro 2022, 9, ENEURO–0268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, V.; Ohström, K.-R.P.; Lindenberger, U. Interactive Brains, Social Minds: Neural and Physiological Mechanisms of Interpersonal Action Coordination. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinero, D.A.; Dikker, S.; Van Bavel, J.J. Inter-Brain Synchrony in Teams Predicts Collective Performance. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2021, 16, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, H.; Luo, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, X. Interpersonal Neural Synchronization During Cooperative Behavior of Basketball Players: A fNIRS-Based Hyperscanning Study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl, V.; Wass, S.; Leong, V.; Scharke, W.; Wistuba, S.; Wirth, C.L.; Konrad, K.; Gerloff, C. Multimodal Hyperscanning Reveals That Synchrony of Body and Mind Are Distinct in Mother-Child Dyads. NeuroImage 2022, 251, 118982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astolfi, L.; Toppi, J.; De Vico Fallani, F.; Vecchiato, G.; Cincotti, F.; Wilke, C.T.; Yuan, H.; Mattia, D.; Salinari, S.; He, B.; et al. Imaging the Social Brain by Simultaneous Hyperscanning During Subject Interaction. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2011, 26, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, S.C.; Hyon, R.; Baek, E.C.; Parkinson, C.; Cerf, M. Personality Similarity Predicts Synchronous Neural Responses in fMRI and EEG Data. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jia, H.; Zheng, M.; Liu, T. Group Decision-Making Behavior in Social Dilemmas: Inter-Brain Synchrony and the Predictive Role of Personality Traits. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 168, 110315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Chen, C.; Chen, C.; He, Q.; Moyzis, R.K.; Xue, G.; Dong, Q. Striatum-Centered Fiber Connectivity Is Associated with the Personality Trait of Cooperativeness. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0162160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, N.A.; Davidson, R.J. Patterns of Brain Electrical Activity during Facial Signs of Emotion in 10-Month-Old Infants. Dev. Psychol. 1988, 24, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinada, M.; Yamagishi, T. Physical Attractiveness and Cooperation in a Prisoner’s Dilemma Game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Facial Action Coding System 2019.

- Delpy, D.T.; Cope, M.; Zee, P.V.D.; Arridge, S.; Wray, S.; Wyatt, J. Estimation of Optical Pathlength through Tissue from Direct Time of Flight Measurement. Phys. Med. Biol. 1988, 33, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholkmann, F.; Kleiser, S.; Metz, A.J.; Zimmermann, R.; Mata Pavia, J.; Wolf, U.; Wolf, M. A Review on Continuous Wave Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Imaging Instrumentation and Methodology. NeuroImage 2014, 85, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homan, R.W.; Herman, J.; Purdy, P. Cerebral Location of International 10–20 System Electrode Placement. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1987, 66, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozawa, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Sakaki, K.; Yokoyama, R.; Kawashima, R. Interpersonal Frontopolar Neural Synchronization in Group Communication: An Exploration toward fNIRS Hyperscanning of Natural Interactions. NeuroImage 2016, 133, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinsted, A.; Moore, J.C.; Jevrejeva, S. Application of the Cross Wavelet Transform and Wavelet Coherence to Geophysical Time Series. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2004, 11, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Bryant, D.M.; Reiss, A.L. NIRS-Based Hyperscanning Reveals Increased Interpersonal Coherence in Superior Frontal Cortex during Cooperation. NeuroImage 2012, 59, 2430–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, C.; Dai, B.; Shi, G.; Ding, G.; Liu, L.; Lu, C. Leader Emergence through Interpersonal Neural Synchronization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 4274–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yekutieli, D.; Benjamini, Y. Resampling-Based False Discovery Rate Controlling Multiple Test Procedures for Correlated Test Statistics. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1999, 82, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, S.; Bachmann, I. Path Analysis. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Matthes, J., Davis, C.S., Potter, R.F., Eds.; Wiley, 2017; pp. 1–9 ISBN 978-1-118-90176-2.

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Hosseini, S.; Miyake, Y.; Nozawa, T. Unravelling the Relation between Altruistic Cooperativeness Trait, Smiles, and Cooperation: A Mediation Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1227266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatman, J.A.; Barsade, S.G. Personality, Organizational Culture, and Cooperation: Evidence from a Business Simulation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, L.; Fuchs, A.; Williams, K.; Moehler, E.; Resch, F.; Koenig, J.; Kaess, M. Child Temperament as a Longitudinal Predictor of Mother–Adolescent Interaction Quality: Are Effects Independent of Child and Maternal Mental Health? Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentland, A. Honest Signals: How They Shape Our World; MIT Press, 2010; ISBN 978-0-262-26104-3.

- Balconi, M.; Fronda, G. The “Gift Effect” on Functional Brain Connectivity. Inter-Brain Synchronization When Prosocial Behavior Is in Action. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Shi, X.; Cai, Q.; Li, X.; Cheng, X. Inter-Brain Synchrony and Cooperation Context in Interactive Decision Making. Biol. Psychol. 2018, 133, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Turel, O.; Feng, T.; Zhu, C.-Z.; He, Q. Dyad Sex Composition Effect on Inter-Brain Synchronization in Face-to-Face Cooperation. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021, 15, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.G.; Vrtička, P.; Cui, X.; Shrestha, S.; Hosseini, S.M.H.; Baker, J.M.; Reiss, A.L. Inter-Brain Synchrony in Mother-Child Dyads during Cooperation: An fNIRS Hyperscanning Study. Neuropsychologia 2019, 124, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraishi, M.; Shimada, S. Inter-Brain Synchronization during a Cooperative Task Reflects the Sense of Joint Agency. Neuropsychologia 2021, 154, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djalovski, A.; Dumas, G.; Kinreich, S.; Feldman, R. Human Attachments Shape Interbrain Synchrony toward Efficient Performance of Social Goals. NeuroImage 2021, 226, 117600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Mok, C.; Witt, E.E.; Pradhan, A.H.; Chen, J.E.; Reiss, A.L. NIRS-Based Hyperscanning Reveals Inter-Brain Neural Synchronization during Cooperative Jenga Game with Face-to-Face Communication. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Mai, X.; Wang, S.; Zhu, C.; Krueger, F.; Liu, C. Interpersonal Brain Synchronization in the Right Temporo-Parietal Junction during Face-to-Face Economic Exchange. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, X.; Zhu, N.; Li, D.; Zhang, M. The Effect of Task Performance and Partnership on Interpersonal Brain Synchrony during Cooperation. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Pan, Y.; Cheng, X. Brain-to-Brain Synchronization across Two Persons Predicts Mutual Prosociality. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2017, 12, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinreich, S.; Djalovski, A.; Kraus, L.; Louzoun, Y.; Feldman, R. Brain-to-Brain Synchrony during Naturalistic Social Interactions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, C.; Pesquita, A.; Brennan, A.A.; Perdikis, D.; Enns, J.T.; Brick, T.R.; Müller, V.; Lindenberger, U. Teams on the Same Wavelength Perform Better: Inter-Brain Phase Synchronization Constitutes a Neural Substrate for Social Facilitation. NeuroImage 2017, 152, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D.; Kudoh, T. American-Japanese Cultural Differences in Attributions of Personality Based on Smiles. J. Nonverbal Behav. 1993, 17, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.L.; Blevins, E.; Bencharit, L.Z.; Chim, L.; Fung, H.H.; Yeung, D.Y. Cultural Variation in Social Judgments of Smiles: The Role of Ideal Affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 116, 966–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl, V.; Gerloff, C.; Scharke, W.; Konrad, K. Brain-to-Brain Synchrony in Parent-Child Dyads and the Relationship with Emotion Regulation Revealed by fNIRS-Based Hyperscanning. NeuroImage 2018, 178, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvirts, H.Z.; Perlmutter, R. What Guides Us to Neurally and Behaviorally Align With Anyone Specific? A Neurobiological Model Based on fNIRS Hyperscanning Studies. The Neuroscientist 2020, 26, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant A’s cooperation level (i.e., how much A gives) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant B’s cooperation level | 150 | 100 | … | 0 | |

| 150 | 300R300 | 200R350 | 0R450 | ||

| 100 | 350R200 | 250R250 | 50R350 | ||

| … | |||||

| 0 | 450R0 | 350R50 | 150R150 | ||

| Effect | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.661 | 0.415 | 0.91 | <2e−16 *** |

| Direct effect | 0.599 | 0.339 | 0.86 | <2e−16 *** |

| Indirect effect | 0.062 | −0.056 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| Period | Estimate (Genuine) |

Estimate (Permutated) |

T-Value | Df | p-Value | Fdr-Adjusted Q-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.48 | 0.336 | 0.312 | 2.726 | 65.955 | 0.0081 | 0.0479 |

| 16.40 | 0.344 | 0.309 | 3.993 | 64.634 | 0.0001 | 0.0016 |

| 17.37 | 0.352 | 0.305 | 4.896 | 59.746 | 7.77E-06 | 0.0001 |

| 18.41 | 0.357 | 0.304 | 5.222 | 55.929 | 2.69E-06 | 0.0001 |

| 19.50 | 0.359 | 0.306 | 4.842 | 53.705 | 1.13E-05 | 0.0001 |

| 20.66 | 0.359 | 0.311 | 4.006 | 51.616 | 0.0001 | 0.0016 |

| 21.89 | 0.358 | 0.316 | 3.103 | 48.912 | 0.0031 | 0.0217 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).