1. Introduction

Soils are the largest reservoir of terrestrial organic carbon (C), containing approximately three times more C than the atmosphere (Sanderman et al., 2017). Soil organic matter (SOM) is critical to ecosystem sustainability and plays a vital role in maintaining soil fertility, structure, and vitality (Dutta et al., 2022). In addition, increasing soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration can mitigate climate change (Lal, 2004; Paustian et al., 2016; IPCC, 2018). Farming practices affect SOM by altering the input of carbon from crop residues or organic fertilizers and by indirectly affecting SOC turnover through soil disturbance. A combination of practices such as high use of organic inputs, permanent soil cover and reduced tillage can increase soil carbon sequestration.

Tillage is one of the used tools that can affect biological C sequestration and effects the GHG production. Globally, the shift of tillage practice from conventional tillage to no-tillage is effectively protecting soils under cropping, improving their quality – reducing their rate of SOM decline – as well as enhancing the resilience of cropping systems (Mehra et al., 2018). Intensive tillage (i.e., plow-based tillage) can destroy soil aggregates (Lichter et al., 2008), essential ecosystem services – such as crop biodiversity and C storage in many agricultural soils (Levine et al., 2011; Paustian et al., 2019; Roesch et al., 2007; Sanderman et al., 2017). Direct seeding can also cause some direct seeding problems (Blanco-Canqui and Wortmann, 2020). Strip tillage combines two soil zones with different properties and functions (Pöhlitz et al., 2018). Favourable conditions for seed germination and plant growth are created in the sowing area, uncultivated interrow serve to restore soil fertility (Pöhlitz et al., 2018). By combining cover crops with strip seeding, the negative impact of direct seeding on the soil and the plant can be reduced. Cong et al. (2015) indicate that soil C sequestration potential of strip intercropping is management practises to conserve organic matter in soil.

Intensification and diversification of the rotation system by replacing fallow with leguminous crops is a more recent practice that is believed to increase wheat yields and improve overall soil health (Gollany, 2022). Diversification of crop systems with leguminous crops improve nitrogen (N) use efficiency (Gaudin et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2008) due to the additional N resulting from the mineralization of legume residues. Legumes are grown in a variety of ways, such as main crop, catch crop or intercrop. In arable farms they are important as supporting crops, they can perform many other ecosystem services. According to Domnariu (2024), even less is known about the specific effects of legume N on SOC when transitioning to a more diverse cropping system.

The results of previous studies show that leguminous crops can gradually increase SOC stock, fraction-C concentration, stability of macroaggregates, soil moisture content, total porosity, and steadily increase the yield of subsequent crops (Li et al., 2016; Huynh et al., 2019; Udom and Omovbude, 2019). When combined with reduced tillage, these benefits could be enhanced (Raimbault and Vyn, 1991). More N from biological N fixation of legumes is believed to be one of the main drivers (Amado et al., 2006). Therefore, legumes' residues retention can retain more C in soil than residues of cereals. However, it has also been suggested that the increased soil N caused by its residue decomposition might stimulate microbial growth and production of extracellular enzymes through the priming effect, leading to more local C and N loss (Liu et al., 2022).

There is no doubt that the influence of leguminous crops is crucial for C accumulation in the soil. Hu et al. (2022), found that after intercropping, SOC content, water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC) and the readily oxidized organic carbon significantly increased in the soil. It was concluded that the content of SOC positively related to the size of soil aggregates, and it is influenced by the type and characteristics of the soil and meteorological and climatic peculiarities. Therefore, when determining general patterns and drawing conclusions, researchers must consider specific local site conditions.

Crop rotation diversification using legumes has been advocated as one of the solutions to improve the resilience of the crop system to various environmental stresses and the use of N resources. However, when forage legumes or grass-legumes are ploughed, there is a high risk of nitrate leaching, especially in sandy soils (De Notaris et al., 2018). The use of cover crops and the adoption of RT are essential conservation practices to increase of SOC and N stocks and increase soil microbial activity (Carlos et al., 2023). So, more importance should be given to the relationship of N with SOC sequestration under the combination of strip tillage with the legumes intercropping. We hypothesize that winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and forage legume strip intercropping technologies could optimize crop residue mineralization and increase SOC. Thus, this work aims to evaluate cover crops and strip tillage on soil C and N contents and winter wheat grain yield.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Soil

Field experiments were conducted at Joniškėlis Experimental Station of the Institute of Agriculture, Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry (LAMMC) in the northern part of Central Lithuania’s lowland in 2018–2020. The soil at the experimental site was classified as an Endocalcari-Endohypogleyic Cambisol (Siltic, Drainic), the texture of which is clay loam on silty clay with deeper lying sandy loam. The topsoil pH (0–25 cm) is close to neutral (6.1), medium in phosphorus (146 mg P2O5 kg−1), high in potassium (276 mg K2O kg−1), and moderate in humus (2.54%).

2.2. Experimental Design and Details

Two analogous field experiments were set up in 2018-2019 (I experiemntį) and in 2019-2020 (II experiment). The main crop in first year sequence experiments (2018 and 2019) was spring oat (

Avena sativa L.), cv. ‘Migla DS’ (O); these were undersown with black medick (

Medicago lupulina L.) cv. ‘Arka 133 DS’ (O+BM), white clover (

Trifolium repens L.) cv. ‘Nemuniai’ (O+WC) and Egyptian clover (

Trifolium alexandrinum L.) cv. ‘Cleopatra’ (O+EC). Oat and forage legumes (BM, WC, and EC) were also grown in monocrops. In 2019 and 2020, winter wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) cv. ‘Gaja’ was grown in intercropping with forage legumes (BM+WW, WC+WW, EC+WW) and in winter wheat (WW) monocrops. Eight winter wheat management strategies with two soil tillage treatments—conventional deep inversion tillage and strip tillage—were compared (

Table 1).

The treatments included pure stands of wheat grown after three forage legume monocrops using conventional tillage and sowing (CTS): O–WW(CTS), BM–WW(CTS), WC–WW(CTS), and EC–WW(CTS); and grown after oat monocrop and oat-forage legume intercrop using strip tillage (STS): O–WW(STS), O+BM–BM+WW(STS), O+WC–WC+WW(STS), and O+EC–EC+WW(STS). The mass of EC froze in winter, BM and WC – left to grow. The control treatments included winter wheat grown as a sole crop in a cereal sequence: O–WW(CTS). Oat straw was used as fertilizer in all experimental plots, where outs were grown. The experiment plots were designed as a complete one-factor randomized block with four replicates. The size of individual plot was 6 × 20 m.

2.3. Sampling, Preparation, and Analyses

Winter wheat grain yield was harvested when most crops reached the hard dough stage (BBCH 87). Each experimental plot was harvested using a small-plot combine harvester. After grain threshing, the yields were reported at 14% moisture.

To determine soil mineral nitrogen – SMN (N-NH4 + N-NO3) content, soil samples were collected in spring before winter wheat growth resumed, 25 March 2019 and 2020; all were at 0–30 cm and 30–60 cm depths. Five cores were randomly collected from each plot, crushed, and stored in a deep freezing (−18 °C) until N-NH4 and N-NO3 analyses. The concentrations of soil N-NO3 were determined using the potentiometric method in a 1% extract of KAl(SO4)2·12H2O (1:2.5, w/v) (Jurgutis et al., 2021), and those of soil N-NH4 were determined using spectrophotometric measurements (with UV/Vis Cary 50, Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) at a wavelength of 655 nm in a 1 M KCl extract (1:2.5, w/v) (Baethgen et al., 1989).

Soil samples for agrochemical characterization were taken from the 0–25 cm soil layer, and collected three times during the experimental period: in spring before oats and forage legumes sowing; in autumn after winter wheat sowing and after harvest. Soil samples were air-dried, crushed, and sieved through a 0.25 mm sieve, manually removing visible roots and plant residues, and then used for the water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC) and mobile humic fractions analyses.

WEOC was measured in deionized water extract (1:5, w/v) using the IR detection method after UV-catalyzed persulphate oxidation with ions chromatograph (SKALAR, Netherlands). The analysis procedure was performed according to the methodology recommended by SKALAR, using C8H5KO4 as a standard (Volungevičius et al., 2015).

Mobile humic substances (HSs) were extracted with 0.1 M NaOH (Ponomareva and Plotnikova, 1980; Jokubauskaitė et al., 2014). The suspension of soil and solution (v/w, 1:10) was periodically shaken at ambient temperature for 24 h. Next, 10 mL of a saturated Na2SO4 solution was added, and the extract was separated by centrifugation at 3800 rpm (Universal 32, Hettich, Germany) for 10 min. The MHSs solution was evaporated to dry mass (DM) and quantified spectrophotometrically as in typical SOC determination measurements at 590 nm using glucose as a standard (Nikitin, 1999). For the determination of mobile humic acids (HAs) in the soil samples, an aliquot of the extract was acidified to pH 1.3–1.5 with 1 M H2SO4 and heated at 68–70 °C to precipitate the HAs. The precipitated HAs were filtered and rinsed with 0.01 M H2SO4 solution to completely remove the mobile fulvic acids. The HAs were subsequently dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH solution, evaporated, and quantified spectrophotometrically.

All concentrations of soil compounds were expressed on a DM basis. All chemical analyses of soil were conducted at the Chemical Research Laboratory of the Institute of Agriculture, LAMMC.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Collected winter wheat grain yield and soil data were subjected to two/tree-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant differences between factors and interactions were determined by F-test at p < 0.05, p < 0.01 probability levels. Significantly differences in data were calculated by Tukey’s test at p < 0.05, where means with the same letter are not significantly different. Standard error of the mean (SE) was used to represent error values.

Statistical analyses were performed with Statistica software, version 7.1 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

2.5. Meteorological Conditions

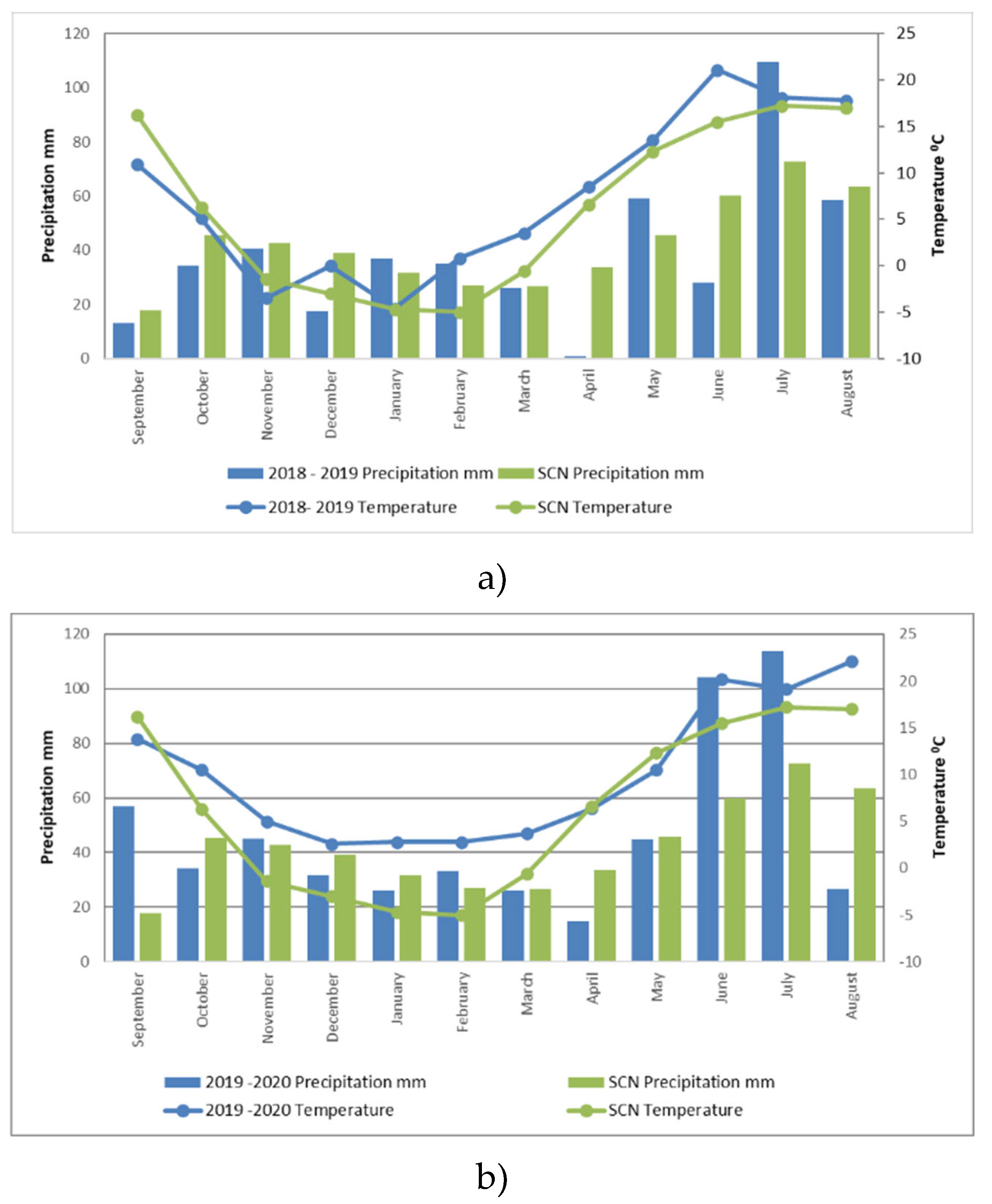

The weather data were obtained from the meteorological station, located 1.0 km away from the experimental site (

Figure 1a, b). In the first half of the 2018 growing season, rainfall was close to the Standard Climate Norm (SCN). In April and May, there was no lack of heat and sunshine, which led to good plant development in the early growth stages. The low rainfall in June slowed down plant growth. Dry weather persisted in July and August, with lower rainfall compared to the SCN.

Autumn 2018 was dry, especially in September (only 13.3 mm of precipitation). The low rainfall limited soil processes and the migration of mineral N to deeper layers. December was warm, but rainfall was low (17.5 mm). 2019 was slightly wetter and the seasonal distribution of rainfall was much more even than in 2018. April was dry. The dry period ended only at the end of May. This may have had a negative impact on the release of N from plant residues and soil and on winter wheat nutrition. In the third ten-day period of May, 42 mm of precipitation fell, which accelerated the growth of plant biomass. June was unusually warm, with an average daily temperature 6 °C above the SCN. However, the limited rainfall did not lead to a very intense growth of plant biomass. July was the wettest month, with 109.3 mm of rainfall, 36.5 mm more than the SCN.

In August and September (2019), there was sufficient rainfall and warmth for plant development. The autumn of 2019 was much warmer than that of 2018. The months of December–February 2019–2020 were characterised by positive average monthly daily temperatures, which is not common in Lithuania. Spring 2020 was warm and early, but rainfall was low. April was dry, with only 14.9 mm of precipitation, 18.8 mm below the SCN. However, the dry period was not prolonged, with May rainfall close to the SCN. June and July were characterised by an excess of rainfall and warmth, which led to an intensive growth of cereal and forage legume biomass. The 2020 growing season was characterised by an uneven distribution of rainfall, with insufficient rainfall in the first half of the growing season and excess rainfall in the second half.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Mineral Nitrogen

Tillage method (p<0.01) and its interaction with legumes (p<0.05) had a significant effect on the SMN content. On average, significantly less (17.3% on average) SMN was detected using winter wheat strip tillage and sowing compared to conventional tillage and sowing (

Figure 2a). At the resumption of winter wheat vegetation, substantially more (30.4%) SMN was detected in winter wheat field after ploughed WC compared to the preceding crop of oats. Other pre-sown legumes (BM, EC) tended to increase (5.9–12.5%) the SMN content. Strip tillage and sowing of winter wheat into forage legumes (except EC) resulted in a 5.7–9.1% increase in SMN content compared to sowing into oat stubble.

3.2. Productivity of winter wheat

Statistical analysis showed that winter wheat grain yield was significantly affected by the year (p<0.01) conditions. On average, the grain yield in 2020 was significantly higher (51%) compared to 2019. The interaction between tillage and cropping also contributed to a significant increase in grain yields (p<0.01).

Table 2 shows the average data for both trials. A comparison of grain yields of winter wheat (oats as a preceding crop) sown in ploughed soil and sown using strip tillage method showed an average yield reduction of 7%, but not significantly. The cultivation of forage legumes further accentuated these differences. The winter wheat grain yield increase with forage legume ploughing was between 47 and 58% compared to the control of the oat pre-crop. The highest yield increase was due to ploughing WC (1854 kg ha

-1), but it was not significantly different from ploughing other forage legumes.

On average, strip tillage and sowing reduced wheat grain yield by 30% compared to wheat under conventional tillage and sowing. Grain yield decreased from 105 to 348 kg ha-1 (except for EC). The negative effect of strip tillage and sowing was mitigated by BM (BM+WW). Here, the grain yield increase was 322 kg ha-1 compared to O-WW(STS). This yield increase was 10% and 5% higher compared to the oat pre-crop with conventional or strip tillage and WW sowing respectively. This could be due to the EC frozen aboveground mass and the nutrients released from it. Winter wheat yields were lowest when grown in a binary crop with WC, which competed with the winter wheat between the rows. The results show that winter wheat grown in a binary crop with forage legumes have significantly lower grain yield than winter wheat grown after grasses under ploughing and conventional sowing.

3.3. Forms of soil organic carbon

In the year of the experimental set-up, water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC) and mobile humic substances (HSs) were higher in the soil of experiment II and mobile humic acids (HAs) – higher in the soil of experiment I. The WEOC content of the soil depended on the interaction of three factors: year, tillage / sowing method and crop (p<0.05) (

Table 3).

During the study period, WEOC changed little (Experiment I) or decreased (Experiment II). In 2018, after sowing winter wheat, the highest WEOC was found in the soil of the binary crop WC+WW(STS) and the lowest – in the soil of O-BM (irrespective of tillage and sowing method). Experiment II showed the highest WEOC in EC+WW(STS) soil and the lowest in BM+WW(STS) soil. These mobile organic carbon compounds decreased after harvesting winter wheat. There were no significant differences between the variants. The studies show that strip tillage and sowing, as well as legume crops, tend to increase WEOC content.

In both study periods, the amount of mobile humic substances (HSs) was significantly increased by year and plant interactions (p<0.01). On average, HSs increased over the study period. In Experiment I, after sowing winter wheat, the highest HSs was found in the soil of the variants EC-WW(CTS), WC+WW(STS) and EC+WW(STS) (

Table 4). Irrespective of tillage methods, legume WC and EC significantly increased the HSs content compared to the preceding crop of oats.

Experiment II showed that forage legumes BM and WC had a positive effect on the accumulation of these substances. The lowest levels of HSs were found after oats and EC. Tillage and sowing method had no significant effect. These differences were maintained after harvesting winter wheat. In Experiment I, the HSs content was significantly higher in WC and EC plots compared to the control, irrespective of tillage and sowing method. Experiment II showed that the positive effect of BM(CTS) and WC(CTS) remained. In the strip tillage and sowing plots, the highest HSs content was found in the WC+WW binary crop. It can be concluded that the performance of forage legumes (except WC) is influenced by their growing conditions.

After sowing winter wheat, the content of humified organic carbon compounds - HAs - depended on the interaction between year and tillage (p<0.05) and year and crop (p<0.05). On average, the highest levels of HAs were found in the plots of Experiment II under strip tillage and sowing (

Table 5).

In Experiment I, annual clover (EC) had the greatest positive effect. It can be argued that the roots and residues of annual plants restructure and prepare to replenish the soil with organic matter, unlike perennial grasses. According to the average data from Experiment II, BM and WC increased the mobile humic acid content by 14.4 and 15.3%, respectively, compared to the oat pre-crop, irrespective of tillage method. The effect of EC was not consistent. After cereal harvesting, the year had the greatest influence on soil HAs. The data from Experiment I showed that the positive influence of EC remained, with a significant increase in HAs compared to the oat pre-crop. Strip tillage and sowing tended only to increase the HAs content. In Experiment II, the data were less consistent and contradictory. Compared to the data at the beginning of Experiment II, the HAs content consistently increased. Strip tillage and WW sowing tended to decrease HAs, while the oat pre-crop tended to increase them. Ploughed WC also showed positive results.

4. Discussion

Wheat grain yield. The suitable combinations of crop management practices and soil health regulate the production potential of several crops under conservation agriculture (Liu et al 2014; Faiz et al., 2022; Yogi et al., 2023). According to Verma et al. (2024), conventional tillage without residue had lower yields than zero-tillage with residues and conventional tillage with residues. Some of the results of scientific research conducted that of excessive tillage operations and no-residue covering, which exposed the soil to water runoff, losses of nutrients, reduced soil microbial diversity, more weed competition, and heat induced moisture loss on bare surface (Nandan et al., 2019; Ankit et al., 2022; Yogi et al., 2023). Lyon et al. (1998) found an 8.0% greater winter wheat yield with conventional tillage than with no-till. Arshad and Gill (1997) reported that comparing conventional, reduced and zero tillage (no-till) systems found during 3 years of testing the greatest average wheat yield for reduced tillage, while conventional tillage had the lowest. Moreno et al. (1997) also indicates that higher winter wheat yield under conservation than traditional tillage, but differences were not significant. According to Plaza-Bonilla et al. (2016), the use of cover crops did not significantly have a negative impact on the yield. Pittelkow et al. (2015) indicate that direct seeding reduced plant yield by 12% without fertilizer and by 4% with the addition of N fertilizer (80-120 kg N ha-1). The decrease in yield depended on the type of plants, hydrothermal conditions, the method of managing plant residues, and N fertilizer rates. After 3 to 10 years, the yield is said to be equivalent to that obtained with conventional tillage (Pittelkow et al., 2015).

Soil organic carbon. As the most active component of SOC, soil water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC), is the main form of SOC migration and transformation (Ritson et al., 2014). WEOC is the sum of a series of dissolved carbonaceous organic compounds as an important index of labile organic carbon pool in soil (Guan et al., 2018). Soil temperature, water content and NH4+-N were the main factors mediating WEOC concentration (Wang et al., 2021). Intercropping increased soil dissolved organic carbon (WEOC) concentration by 2.6–14.5% and accumulation by 8.0–21.1% (Wang et al., 2021).

In soil, the largest proportion of C is humic substances, mainly composed of humin, humic acid and fulvic acid (Wolschick et al., 2018). As a reactive part of soil MHSs, MHAs plays an important role in maintaining soil fertility and nutrient supply (Zhang et al., 2019; Mohinuzzaman et al., 2020). Several studies show that humic matter, as a humified part of soil organic matter (SOM), includes plant remains that have undergone transformation processes in the soil and have already lost their cellular structure (Aleksandrova et al., 1976; Nardi et al., 2021). Kelleher and Simpson (2006) reported that HSs is an operationally defined fraction of soil organic matter and constitutes the largest pool of unfavourable organic carbon in the environment. Previous studies have shown that SOC is more active in large aggregates, and SOM can be stabilized or prevented from breaking down to form stable microaggregates (Six et al., 2002; Bimüller et al., 2016). Intercrops have also been found to increase SOM. Total root biomass in intercrops was on average 23% higher than the average root biomass of common plants (Cong et al., 2015). Research shows that reduced tillage and no-till can improve soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration compared to conventional tillage (Dutta et al. 2022).

Higher lability, carbon pools, and carbon management index were directly correlated with increased carbon fractions in rotations that include legumes and organic nutrition management (Liu et al., 2014; Lal et al., 2018; Babu et al., 2020). The integration of legumes with organic manures in the rice-wheat cropping system also enhanced the carbon pool and the carbon management index (Nath et al., 2019). Within a short period of two years, the addition of residues under zero-tillage and conventional-tillage increased the C inputs by 3 Mg ha−1 yr− 1 over conventional-tillage (without residue) (Verma et al., 2024). Retaining crop residues under zero-tillage conditions promote the creation of bigger macroaggregates, and the presence of micro-aggregates within these macroaggregates acts as a protective barrier for SOC, protecting it from degradation by microbes (Six et al., 2000).

According to Datta et al (2021) for the last nine years, considerable amount of crop residues was recycled in conservation agriculture-based managements (zero tillage wheat and mung bean with partial residue retention to zero tillage -maize followed by zero tillage -wheat and mung bean). Jat et al. (2019a) leading to addition of huge amount of C into soil which upon decomposition converted to stable fractions such as HAs. Higher HAs content in soils under conventional might be due to the roots and rhizodeposition carbon of rice and wheat crops added to the soil during nine years of the experiment as evidenced by grain yield obtained during the period and avoidance of crop residue burning (Datta et al., 2021). Liaudanskiene et al. (2013) reported that minimum tillage practices significantly increased the HAs contents strongly bound to calcium through cation bridging at surface layer. Wolschick et al. (2018) also observed higher amounts of HAs in soil under 27 years of conservation tillage. Higher carbon input through crop residues as well as zero tillage and inclusion of legumes further facilitated the conversion of crop residue carbon to SOC and subsequent formation of more condensed humic acid under conservation agriculture based scenarios as also evidenced by higher SOC and soil aggregation (Jat et al., 2019a,b).

Study suggested that increased biological N fixation and/or reduced gaseous N losses contributed to the increases in soil N in intercrop rotations with legume (Cong et al., 2015).

5. Conclusions

Strip sowing of winter wheat into forage legumes resulted in a significantly lower SMN content and wheat grain yield compared to conventional sowing into forage legumes. Irrespective of tillage and sowing method, WC was the most important contributor to SMN, compared to the oat pre-crop. However, in the binary crop, forage legumes competed with cereals and reduced (especially WC) winter wheat grain yield. The grain yield of winter wheat grown in the binary crop with forage legumes was not significantly lower than that of winter wheat grown after grasses under ploughing and conventional sowing. The content of mobile humic substances and humic acids in the soil was influenced by the use of forage legumes (e.g. oat straw as a fertiliser) and was not significantly influenced by tillage practices. White clover had the greatest positive effect on mobile humic substances. The influence of other forage legumes (BM, EC) was less consistent. After winter wheat harvest, humic acid levels were either increased by WC and EC (Experiment I) or increased in all plots, especially with WC (Experiment II), compared to the data before the experiments were set up.

References

- Aleksandrova, L.N.; Naidenova, O.A. Laboratory Praxis in Soil Science; Kolos: Leningrad, Russia, 1976; p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, T.J.; Bayer, C.; Conceicao, P.C.; Spagnollo, E.; de Campos, B.H.; da Veiga, M. Potential of carbon accumulation in no-till soils with intensive use and cover crops in southern Brazil. Journal of Environmental Quality 2006, 35, 1599–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankit Bana, R.S.; Rana, K.S.; Singh, R.; Godara, S.; Grover, M.; Yadav, A.; Choudhary, A.K.; Singh, T.; Choudhary, M.; Bansal, R.; Singh, N.; Mishra, V.; Choudhary, A.; Yogi, A.K. No-tillage with residue retention and foliar sulphur nutrition enhances productivity, mineral biofortification and crude protein in rainfed pearl millet under Typic Haplustepts. Elucidating the responses imposed on an eight-year long-term experiment. Plants 2022, 11, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.A.; Gill, K.S. Barley, canola and wheat production under different tillage–fallow–green manure combinations on a clay soil in a cold semiarid climate. Soil and Tillage Research 1997, 43, 63–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Singh, R.; Avasthe, R.K.; Yadav, G.S.; Das, A.; Singh, V.K.; Mohapatra, K.P.; Rathore, S.S.; Chandra, P.; Kumar, A. Impact of land configuration and organic nutrient management on productivity, quality and soil properties under baby corn in eastern Himalayas. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 16–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethgen, W.E.; Alley, M.M. A manual colorimetric procedure for measuring ammonium nitrogen in soil and plant Kjeldahl digests. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 1989, 20, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimüller, C.; Kreyling, O.; Kölbl, A.; von Lützow, M.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization in hierarchically structured aggregates of different size. Soil and Tillage Research 2016, 160, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Wortmann, C.S. Does occasional tillage undo the ecosystem services gained with no-till? A review. Soil and Tillage Research 2020, 198, 104–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, F.S.; de Sousa, R.O.; Nunes, R.; de Campos Carmona, F.; Cereza, T.; Weinert, C.; Pasa, E.H.; Bayer, C.; de Oliveira Camargo, F.A. Long-term cover crops and no-tillage in Entisol increase enzyme activity and carbon stock and enable the system fertilization in southern Brazil. Geoderma Regional 2023, 34, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, W.F.; Hoffland, E.; Li, L.; Six, J.; Sun, J.H.; Bao, X.G.; Zhang, F.S.; Van DerWerf, W. Intercropping enhances soil carbon and nitrogen. Global Change Biology 2015, 21, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, A.; Choudhury, M.; Sharma, P.C.; Kaulash, P.; Jat, H.S.; Jat, M.L.; Kar, S. Stability of humic acid carbon under conservation agriculture practices. Soil and Tillage Research 2021, 216, 105–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Notaris, C.; Rasmussen, J.; Sørensen, P.; Olesen, J.E. Nitrogen leaching: A crop rotation perspective on the effect of N surplus, field management and use of catch crops. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2018, 255, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domnariu, H.; Reardon, C.L.; Manning, V.A.; Gollany, H.T.; Trippe, K.M. Legume cover cropping and nitrogen fertilization influence soil prokaryotes and increase carbon content in dryland wheat systems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2024, 367, 108–959. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, A.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Jiménez-Ballesta, R.; Dey, A.; Saha, N.D.; Kumar, S.; Nath, C.P.; Prakash, V.; Jatav, S.S.; Patra, A. Conventional and Zero Tillage with Residue Management in Rice–Wheat System in the Indo-Gangetic Plains: Impact on Thermal Sensitivity of Soil Organic Carbon Respiration and Enzyme Activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 20, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, M.A.; Bana, R.S.; Choudhary, A.K.; Laing, A.M.; Bansal, R.; Bhatia, A.; Bana, R.C.; Singh, Y.; Kumar, V.; Bamboriya, S.D.; Padaria, R.N.; Kaswan, S.; Dabas, J.P.S. Zero tillage, residue retention and system-intensification with legumes for enhanced pearl millet productivity and mineral biofortification. Sustainability 2022, 14, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, A.C.M.; Janovicek, K.; Deen, B.; Hooker, D.C. Wheat improves nitrogen use efficiency of maize and soybean-based cropping systems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2015, 210, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollany, H.T. Assessing the effects of crop residue retention on soil health. In Horwath, W. (Ed.), Improving Soil Health 2022, 189–218. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, London. [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; An, N.; Zong, N.; He, Y.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J.; He, N. Climate warming impacts on soil organic carbon fractions and aggregate stability in a Tibetan alpine meadow. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2018, 116, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Huang, R.; Deng, H.; Li, K.; Peng, J.; Zhou, L.; Ou, H. Effects of different intercropping methods on soil organic carbon and aggregate stability in sugarcane field. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2022, 31, 3587–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, H.T.; Hufnagel, J.; Wurbs, A.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D. Influences of soil tillage, irrigation and crop rotation on maize biomass yield in a 9-year field study in Müncheberg, Germany. Field Crops Research 2019, 241, 107–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 ℃; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jat, H.S.; Datta, A.; Choudhary, M.; Sharma, P.C.; Yadav, A.K.; Choudhary, V.; Gathala, M.K.; Sharma, D.K.; Jat, M.L.; McDonald, A. Climate Smart Agriculture practices improve soil organic carbon pools, biological properties and crop productivity in cereal-based systems of North-West India. Catena 2019a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jat, H.S.; Datta, A.; Choudhary, M.; Yadav, A.K.; Choudhary, V.; Sharma, P.C.; Gathala, M.K.; Jat, M.L.; McDonald, A. Effects of tillage, crop establishment and diversification on soil organic carbon, aggregation, aggregate associated carbon and productivity in cereal systems of semi-arid Northwest India. Soil Tillage Research 190, 128–138. [CrossRef]

- Jokubauskaite, I.; Amaleviciute, K.; Lepane, V.; Slepetiene, A.; Slepetys, J.; Liaudanskiene, I.; Karcauskiene, D.; Booth, C.A. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-size exclusion chromatography (SEC) for qualitative detection of humic substances and natural organic matter in mineral soils and peats in Lithuania. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 2014, 95, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgutis, L.; Šlepetienė, A.; Amalevičiūtė-Volungė, K.; Volungevičius, J.; Šlepetys, J. The effect of digestate fertilisation on grass biogas yield and soil properties in field-biomass-biogas-field renewable energy production approach in Lithuania. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 153, Article–106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, B.P.; Simpson, A.J. Humic Substances in Soils: Are They Really Chemically Distinct? Environmental Science & Technology 2006, 40, 4605–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304(5677), 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Smith, P.; Jungkunst, H.F.; Mitsch, W.J.; Lehmann, J.; Nair, P.R.; McBratney, A.B.; de Moraes Sa, J.C.; Schneider, J.; Zinn, Y.L.; Skorupa, A.L. The carbon sequestration potential of terrestrial ecosystems. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2018, 73, 145A–152A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, U.Y.; Teal, T.K.; Robertson, G.P.; Schmidt, T.M. Agriculture’s impact on microbial diversity and associated fluxes of carbon dioxide and methane. ISME J. 2011, 5, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yu, P.J.; Li, G.D.; Zhou, D.W. Grass–legume ratio can change soil carbon and nitrogen storage in a temperate steppe grassland. Soil Tillage Research 2016, 157, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaudanskiene, I.; Slepetiene, A.; Velykis, A.; Satkus, A. Distribution of organic carbon in humic and granulodensimetric fractions of soil as influenced by tillage and crop rotation. Estonian Journal of Ecology 2013, 62, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, K.; Govaerts, B.; Six, J.; Sayre, K.D.; Deckers, J.; Dendooven, L. Aggregation and C and N contents of soil organic matter fractions in a permanent raised-bed planting system in the Highlands of Central Mexico. Plant and Soil 2008, 305, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, J.D.; Stroup, W.W.; Brown, R.E. Crop production and soil water storage in long-term winter wheat-fallow tillage experiments. Soil Tillage Research 1998, 49, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, M.; Cui, J.; Li, B.; Fang, C.M. Effects of straw carbon input on carbon dynamics in agricultural soils: a meta-analysis. Global Change Biology 2014, 20, 1366–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.X.; Wei, Y.X.; Li, R.C.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.D.; Virk, A.L.; Lal, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.L. Improving soil aggregates stability and soil organic carbon sequestration by no-till and legume-based crop rotations in the North China Plain. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 847, 157518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, P.; Baker, J.; Sojka, R.E.; Bolan, N.; Desbiolles, J.; Kirkham, M.B.; Ross, C.; Gupta, R. Chapter Five - A Review of Tillage Practices and Their Potential to Impact the Soil Carbon Dynamics. In D.L. Sparks (Ed.), Advances in Agronomy 2018, 150, 185–230. Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Mohinuzzaman, M.; Yuan, J.; Yang, X.; Senesi, N.; Li, S.L.; Ellam, R.M.; Mostofa, K.M.G.; Liu, C.Q. Insights into solubility of soil humic substances and their fluorescence characterisation in three characteristic soils. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 720, 137395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, F.; Pelegrin, F.; Fernandez, J.E.; Murillo, J.M. Soil physical properties, water depletion and crop development under traditional and conservation tillage in southern Spain. Soil Tillage Research 1997, 41, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandan, R.; Singh, V.; Singh, S.S.; Kumar, V.; Hazra, K.K.; Nath, C.P.; Poonia, S.; Malik, R.K.; Bhattacharyya, R.; McDonald, A. Impact of conservation tillage in rice–based cropping systems on soil aggregation, carbon pools and nutrients. Geoderma 2019, 340, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardi, S.; Schiavon, M.; Francioso, O. Chemical Structure and Biological Activity of Humic Substances Define Their Role as Plant Growth Promoters. Molecules 2021, 26, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, C.P.; Hazra, K.K.; Kumar, N.; Praharaj, C.S.; Singh, S.S.; Singh, U.; Singh, N.P. Including grain legume in rice–wheat cropping system improves soil organic carbon pools over time. Ecological Engineering 2019, 129, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, B.A. A method for soil humus determination. Agric. Chem. 1999, 3, 156–158. [Google Scholar]

- Paustian, K.; Larson, E.; Kent, J.; Marx, E.; Swan, A. Soil C sequestration as a biological negative emission strategy. Frontiers in Climate 2019, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittelkow, C.M.; Linquist, B.A.; Lundy, M.E.; Liang, X.; Van Groenigen, K.J.; Lee, J.; Van Kessel, C. When does no-till yield more? A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Research 2015, 183, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Bonilla, D.; Nolot, J.M.; Raffaillac, D.; Justes, E. Cover crops mitigate nitrate leaching in cropping systems including grain legumes: Field evidence and model simulations. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2016, 212, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pöhlitz, J.; Rücknagel, J.; Koblenz, B.; Schlüter, S.; Vogel, H.J.; Christen, O. Computed tomography and soil physical measurements of compaction behaviour under strip tillage, mulch tillage and no tillage. Soil Tillage Research 2018, 175, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomareva, V.V.; Plotnikova, T.A. Humus and Soil-Forming1980. Publishing house Nauka: Leningrad, Russia.

- Raimbault, B.A.; Vyn, T.J. Crop rotation and tillage effects on corn growth and soil structural stability. Agronomy Journal 1991, 83, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritson, J.P.; Graham, N.J.D.; Templeton, M.R.; Clark, J.M.; Gough, R.; Freeman, C. The impact of climate change on the treatability of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in upland water supplies: A UK perspective. Science of The Total Environment 2014, 473, 714–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roesch, L.F.W.; Fulthorpe, R.R.; Riva, A.; Casella, G.; Hadwin, A.K.M.; Kent, A.D.; Daroub, S.H.; Camargo, F.A.O.; Farmerie, W.G.; Triplett, E.W. Pyrosequencing enumerates and contrasts soil microbial diversity. The ISME Journal 2007, 1, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderman, J.; Hengl, T.; Fiske, G.J. Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114, 9575–9580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selau Carlos, F.; de Sousa, R.O.; Nunes, R.; de Campos Carmona, F.; Cereza, T.; Weinert, C.; Pasa, E.H.; Bayer, C.; de Oliveira Camargo, F.A. Long-term cover crops and no-tillage in Entisol increase enzyme activity and carbon stock and enable the system fertilization in southern Brazil. Geoderma Regional 2023, 34, 100635. [Google Scholar]

- Six, J.; Conant, R.T.; Paul, E.A.; Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and Soil 2002, 241, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Paustian, K. Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: a mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2000, 32, 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.G.; Gross, K.L.; Robertson, G.P. Effects of crop diversity on agroecosystem function: crop yield response. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udom, B.E.; Omovbude, S. Soil physical properties and carbon/nitrogen relationships in stable aggregates under legume and grass fallow. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2019, 39, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, G.; Dhaka, A.K.; Singh, B.; Kumar, A.; Choudhary, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Kamboj, N.K.; Hasanain, M.; Singh, S.; Bhupenchandra, I.; Shabnam Sanwal, P.; Kumar, S. Productivity, soil health, and carbon management index of soybean-wheat cropping system under double zero-tillage and natural-farming based organic nutrient management in north-Indian plains. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 917, 170418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volungevičius, J.; Amalevičiūtė, K.; Liaudanskienė, I.; Šlepetienė, A.; Šlepetys, J. Chemical properties of Pachiterric Histosol as influenced by different land use. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 2015, 102, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolschick, N.H.; Barbosa, F.T.; Bertol, I.; Bagio, B.; Kaufmann, D.S. Long-term effect of soil use and management on organic carbon and aggregate stability. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2018, 42, e0170393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogi, A.K.; Bana, R.S.; Godara, S.; Sangwan, S.; Choudhary, A.K.; Nirmal, R.C.; Bamboriya, S.; Shivay, Y.S.; Singh, T.; Yadav, A.; Nagar, S.; Singh, N. Elucidating the interactive impact of tillage, residue retention, and system intensification on pearl millet yield stability and biofortification under rainfed agroecosystems. Agriculture, 2023; 10, 1205926. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chi, F.; Wei, D.; Zhou, B.; Cai, S.; Li, Y.; Kuang, E.; Sun, L.; Li, L.J. Impacts of Long-term Fertilization on the Molecular Structure of Humic Acid and Organic Carbon Content in Soil Aggregates in Black Soil. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 11908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).