Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

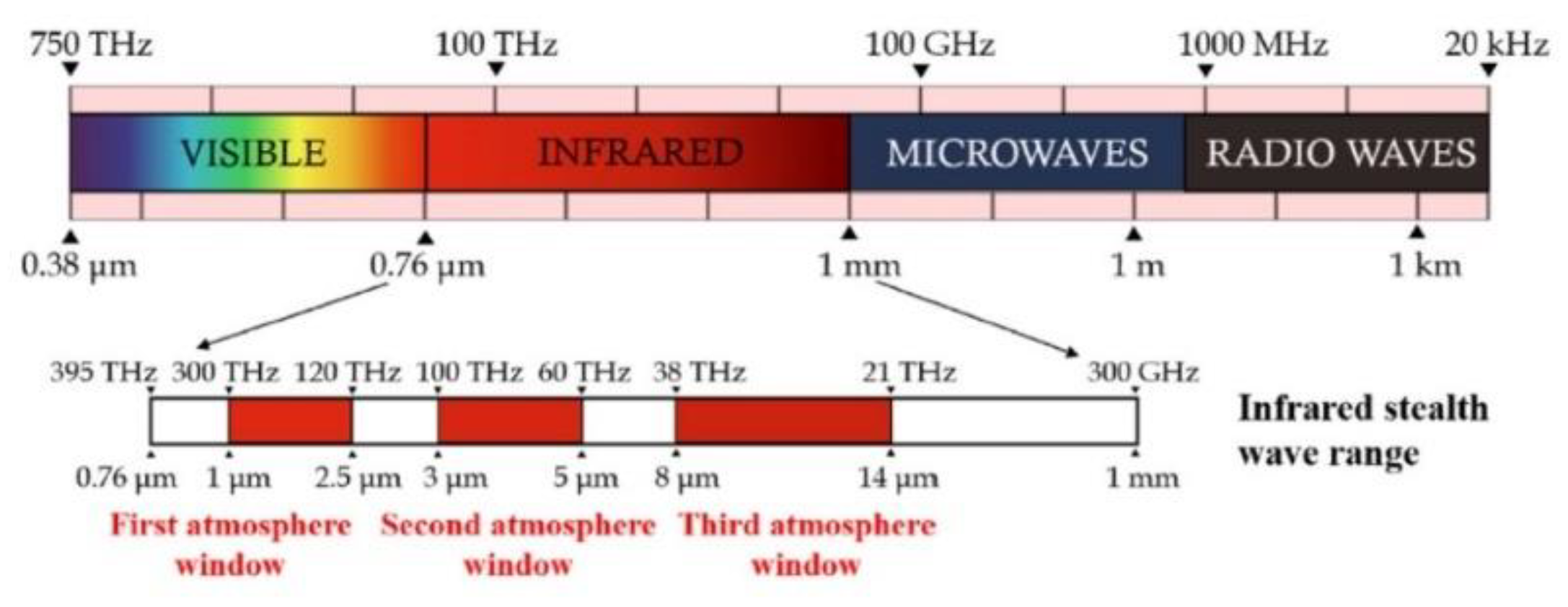

1.1. Thermal Camouflage Principle

1.2. Thermal Camouflage Materials

2. Adaptive Thermal Camouflage Devices Based on Graphene Materials

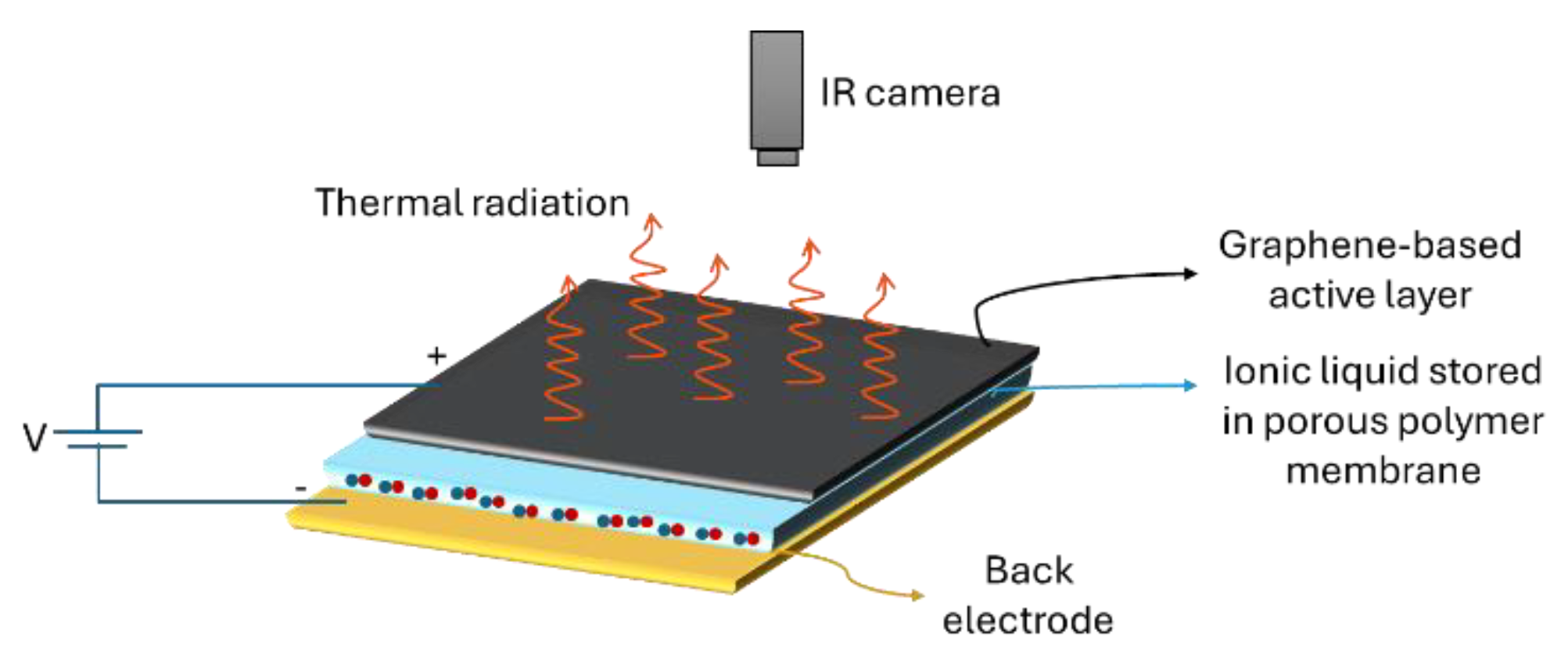

2.1. General Architecture and Principal Elements

2.1.1. Back Electrode

2.1.2. Porous Membrane and Ionic Liquid

| Composition | PP-PE-PP | PE | PTFE | Cellulose paper |

| Thickness [µm] | 25 | 20 | 15 | |

| Average pore size [µm] | 0.070 - 0.150 | - | 0.22 | |

| Porosity [%] | 39 | - | - | |

| Temperature stability [°C] | 135-163 | - | 150-180°C | |

| Water wettability | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | Hydrophilic |

| Electrolyte wettability | Good | Good | Not well | Good |

2.1.3. Graphene-Based Active Layers

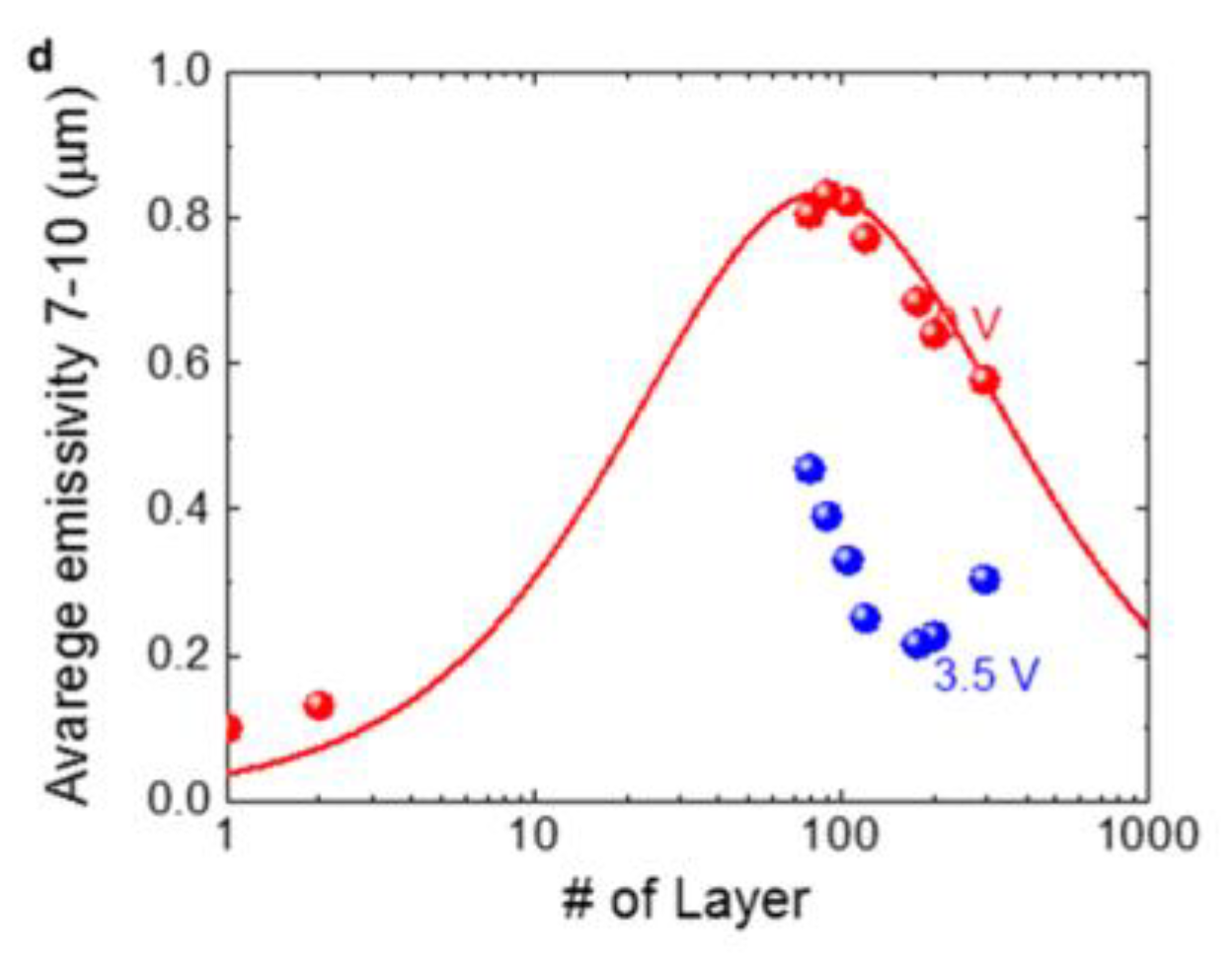

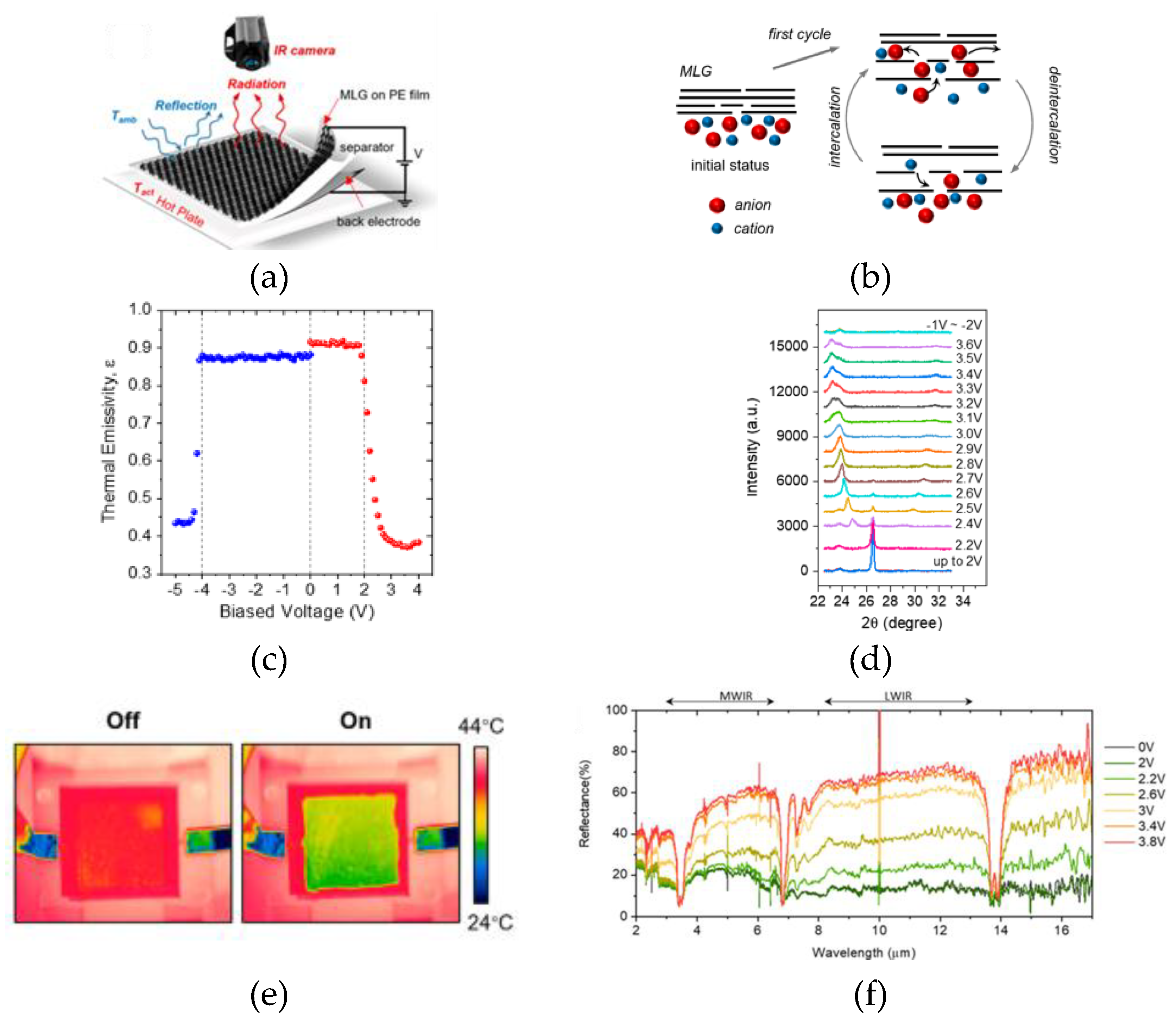

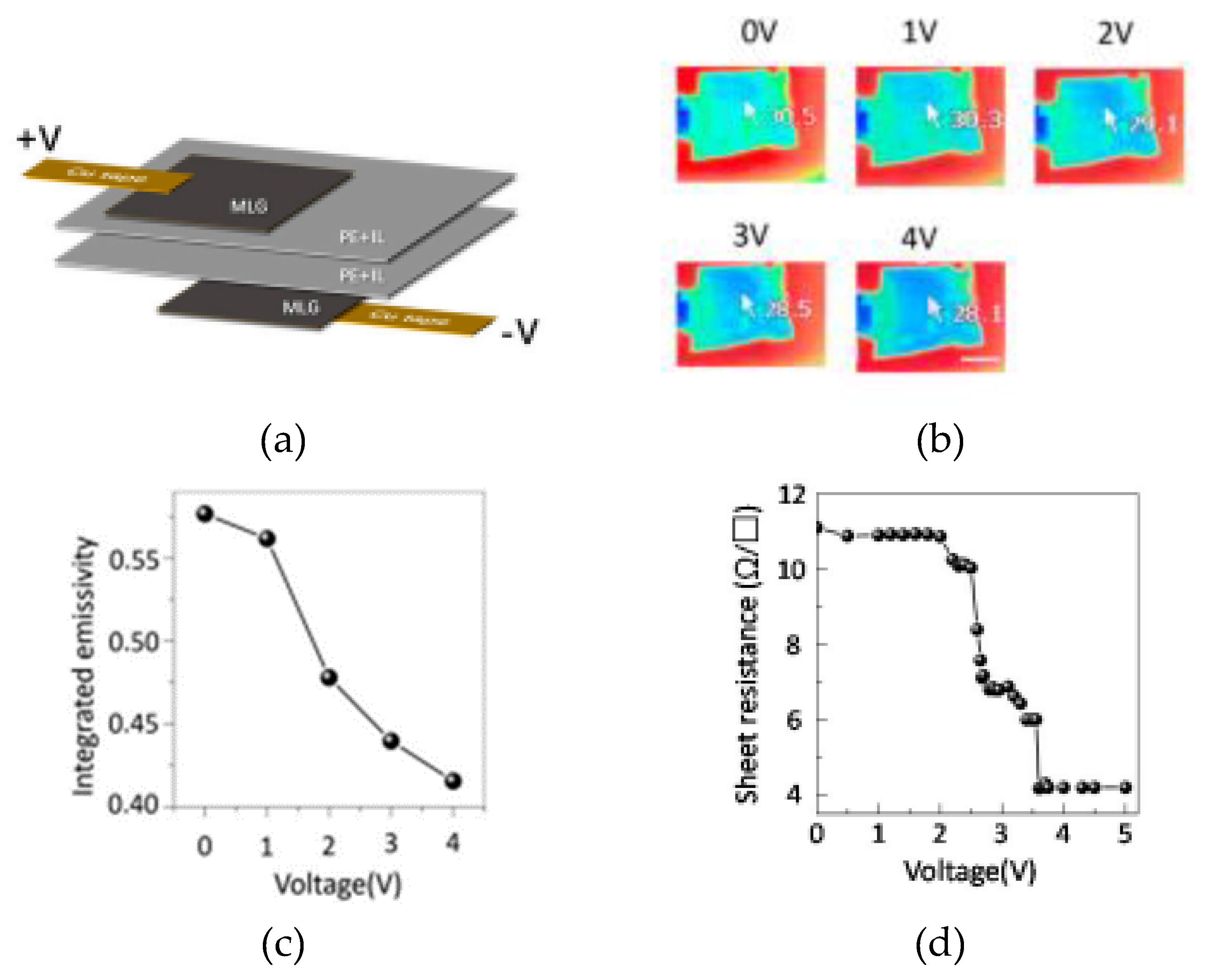

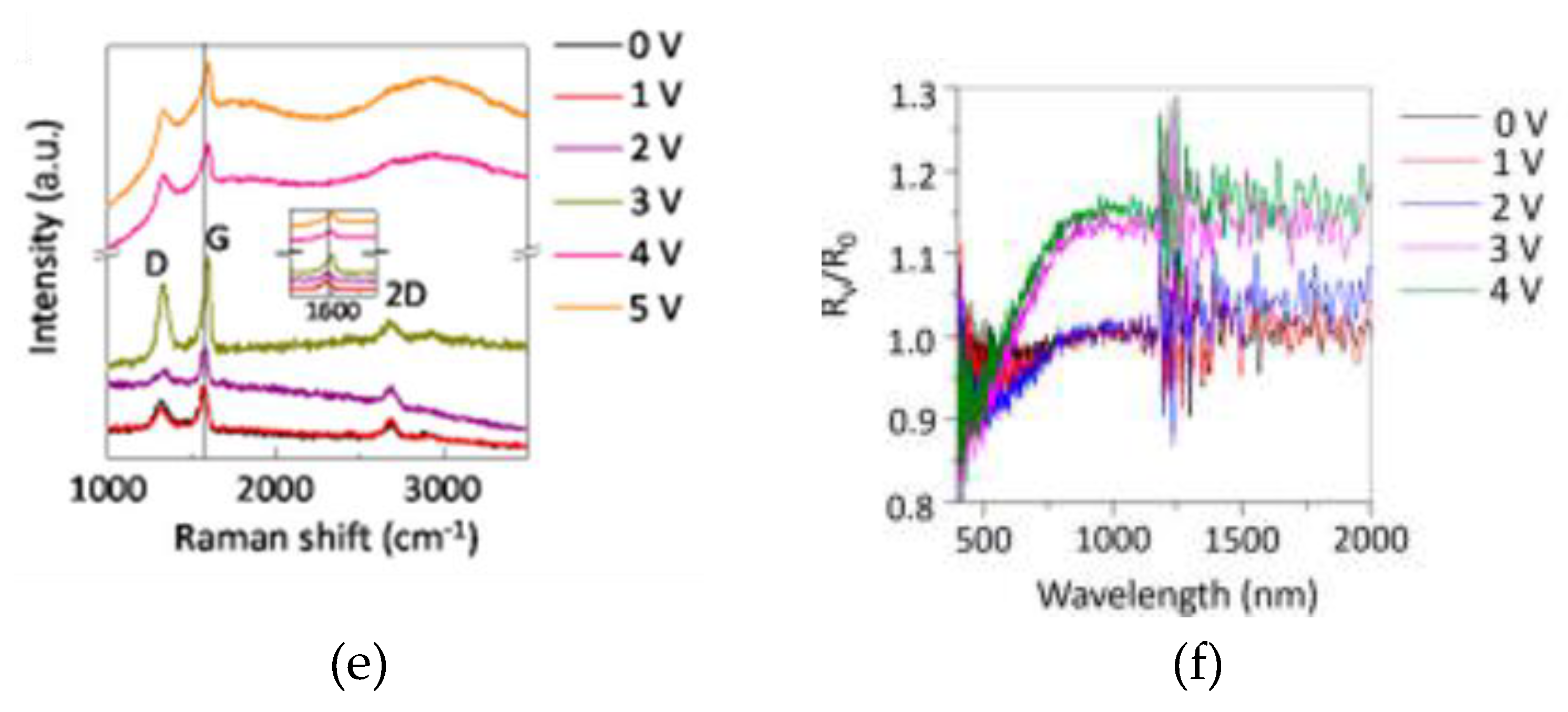

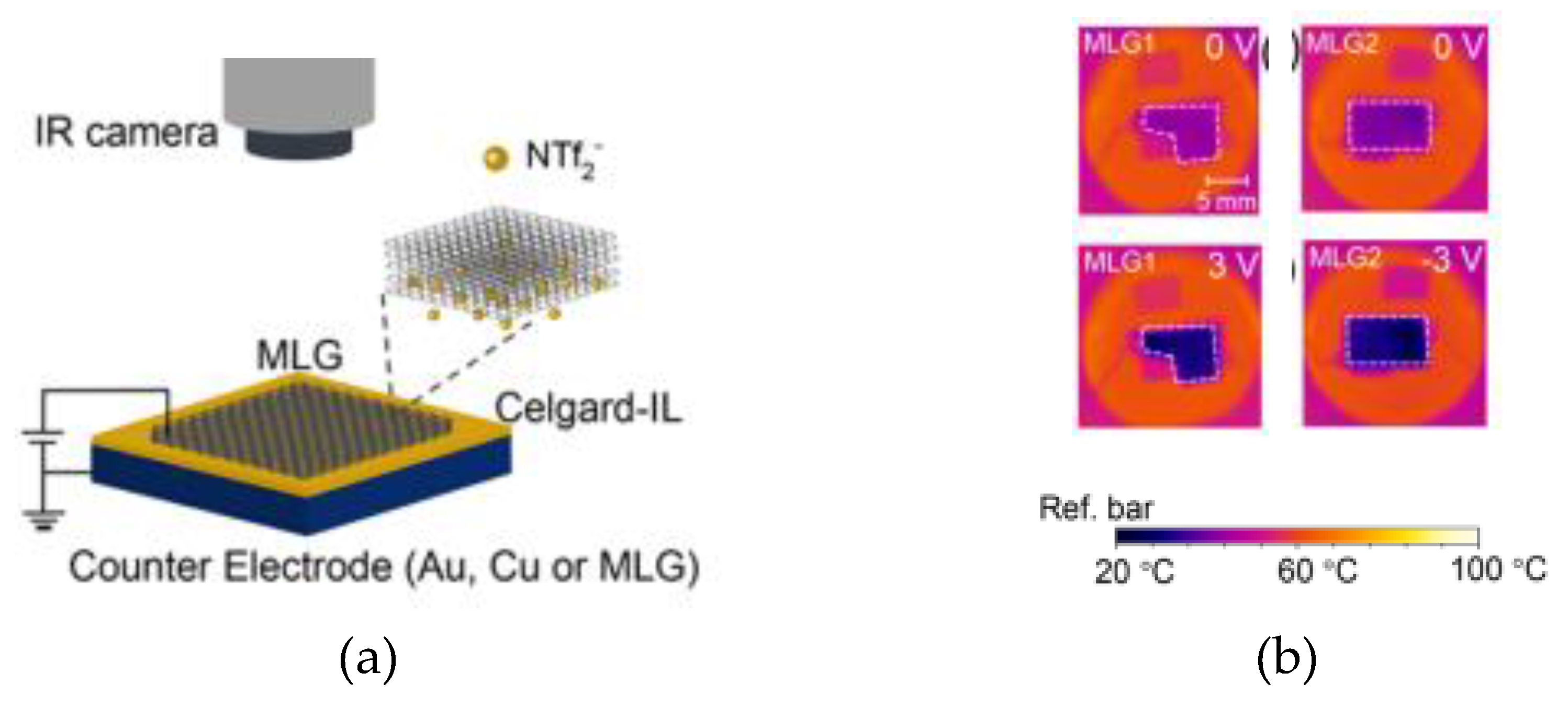

2.2. Thermal Camouflage Devices Based on MLG Active Layer

2.3. Thermal Camouflage Devices Based on vdW Graphene Layer

2.4. Thermal Camouflage Devices Based on Graphene Aerogels (GAs)

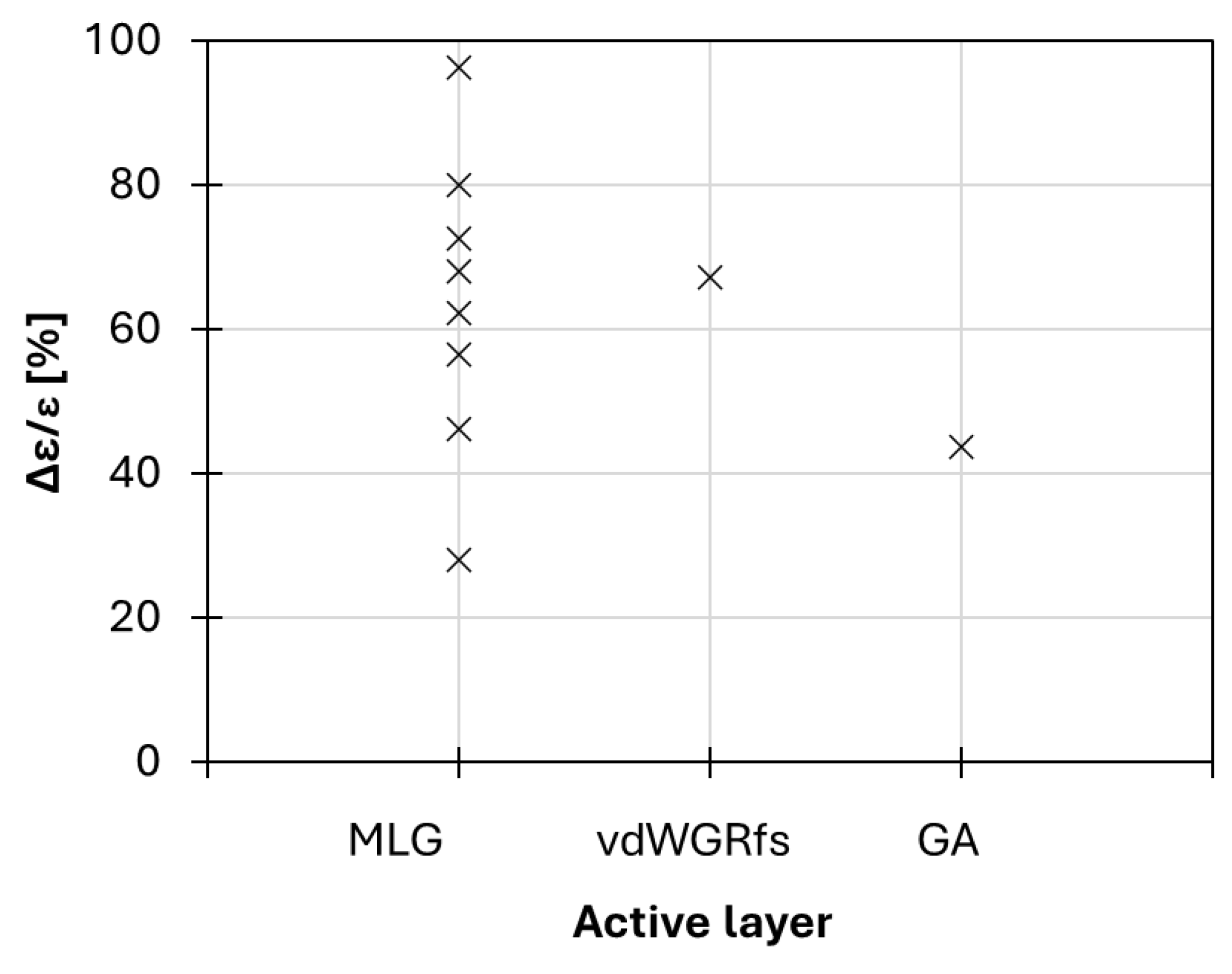

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lyu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Li, G.; Fang, D.; Zhang, X. Nanofibrous Kevlar Aerogel Films and Their Phase-Change Composites for Highly Efficient Infrared Stealth. ACS Nano 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahulikar, S.P.; Sonawane, H.R.; Arvind Rao, G. Infrared Signature Studies of Aerospace Vehicles. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2007, 43, 218–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bai, X.; Yang, T.; Luo, H.; Qiu, C.-W. Structured Thermal Surface for Radiative Camouflage. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Y.; Huang, J. Joint Improvements of Radar/Infrared Stealth for Exhaust System of Unmanned Aircraft Based on Sorting Factor Pareto Solution. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Xi, W.; Liu, Y.; Tang, K.; Song, J.; Luo, X.; Wu, J.; Qiu, C.-W. Thermal Camouflaging Metamaterials. Mater. Today 2021, 45, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Shan, D.; Deng, L.; He, L.; He, J.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Liao, C. Infrared Emissivity and Microwave Transmission Behavior of Flaky Aluminum Functionalized Pyramidal-Frustum Shaped Periodic Structure. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 99, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Ban, G.D.; Ye, S.T.; Liu, W.Y.; Liu, N.; Tao, R. Infrared Emissivity Properties of Infrared Stealth Coatings Prepared by Water-Based Technologies. Opt. Mater. Express 2016, 6, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, G.; Shen, X.; Yan, X.; Cheng, C. Low Infrared Emissivity of Polyurethane/Cu Composite Coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 6077–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xu, G. Effect of Surface Modification of Cu with Ag by Ball-Milling on the Corrosion Resistance of Low Infrared Emissivity Coating. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2010, 166, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.R.; Mengüç, M.P.; Daun, K.; Siegel, R. Thermal Radiation Heat Transfer; CRC Press: Seventh edition. | Boca Raton : CRC Press, 2021. | Revised edition of: Thermal radiation heat transfer / John R. Howell, M. Pinar Mengüç, Robert Siegel. Sixth edition. 2015., 2020; ISBN 9780429327308.

- Rogalski, A. Infrared Detectors: An Overview. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2002, 43, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, M.; Liu, X.; Jin, X.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Ultrathin Titanium Carbide (MXene) Films for High-Temperature Thermal Camouflage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Luo, Z.; Tan, S.; He, J.; Guan, X.; Xu, T.; Guo, S.; Ji, G. Achieving the Low Emissivity of Graphene Oxide Based Film for Micron-Level Electromagnetic Waves Stealth Application. Carbon N. Y. 2024, 218, 118771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.E.M.; Kurcbart, S.M. Hagen-Rubens Relation beyond Far-Infrared Region. EPL (Europhysics Lett. 2010, 90, 44004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yu, D. Preparation and Characterization of a New Low Infrared-Emissivity Coating Based on Modified Aluminum. Prog. Org. Coatings 2013, 76, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Weng, X.; Wei, B.; Yuan, L.; Huang, G.; Du, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, H. Effects of Low-Melting Glass Powder on the Thermal Stabilities of Low Infrared Emissivity Al/Polysiloxane Coatings. Prog. Org. Coatings 2020, 142, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Lv, D. Fabrication and Characterization of a PDMS Modified Polyurethane/Al Composite Coating with Super-Hydrophobicity and Low Infrared Emissivity. Prog. Org. Coatings 2020, 143, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, G.; Liu, C.; Hou, H.; Tan, S. Surface-Modified CeO2 Coating with Excellent Thermal Shock Resistance Performance and Low Infrared Emissivity at High-Temperature. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2019, 357, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Wang, W.; Yu, X.; Xu, H.; Zhong, Y.; Sui, X.; Zhang, L.; Mao, Z. Preparation of ZnO:(Al, La)/Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) Nonwovens with Low Infrared Emissivity via Electrospinning. Mater. Lett. 2015, 143, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Zhou, Y.; He, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, T. Optically Active SiO2/TiO2/Polyacetylene Multilayered Nanospheres: Preparation, Characterization, and Application for Low Infrared Emissivity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 288, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Gu, J.; Ren, F.; Zhang, L.; Xu, G.; Wang, B.; Song, S.; Zhao, J.; Dou, S.; Li, Y. Smart Materials for Dynamic Thermal Radiation Regulation. Small 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.D.; Inoue, T.; Asano, T.; Noda, S. Electrical Modulation of Narrowband GaN/AlGaN Quantum-Well Photonic Crystal Thermal Emitters in Mid-Wavelength Infrared. ACS Photonics 2019, 6, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, C.; Pu, J.; Chen, T.-H.; Liang, J.; Lai, Y.-T.; Rao, Y.; Wu, R.; Han, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; et al. Dynamic Electrochromism for All-Season Radiative Thermoregulation. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, D.; Cheng, H.; Peng, L.; Zu, M. Manipulating Metals for Adaptive Thermal Camouflage. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Cercós, D.; Paulillo, B.; Maniyara, R.A.; Rezikyan, A.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Mazumder, P.; Pruneri, V. Ultrathin Metals on a Transparent Seed and Application to Infrared Reflectors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 46990–46997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.-M.; Ahn, J.; Choi, Y.K.; Lim, T.; Seo, K.; Hong, T.; Choi, G.H.; Kim, H.; Lee, B.W.; Park, S.Y.; et al. Development of a Wearable Infrared Shield Based on a Polyurethane–Antimony Tin Oxide Composite Fiber. NPG Asia Mater. 2020, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Han, K.; Hahn, J.W. Selective Dual-Band Metamaterial Perfect Absorber for Infrared Stealth Technology. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Xu, G.; Tan, S.; Yang, Z.; Bu, H.; Fang, G.; Hou, H.; Li, J.; Pan, L. Controllable Synthesis of ZnO with Different Morphologies and Their Morphology-Dependent Infrared Emissivity in High Temperature Conditions. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 804, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Mao, Z. Low Infrared Emissivity Materials and Their Application in Infrared Stealth: A Review. Rev. Adv. Sci. Eng. 2016, 5, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, J.; Reidinger, M.; Rydzek, M.; Arduini-Schuster, M. Polymer-Based Pigmented Coatings on Flexible Substrates with Spectrally Selective Characteristics to Improve the Thermal Properties. Prog. Org. Coatings 2011, 70, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Luo, M.; Jian, S.; Peng, B.; Deng, L. The Synthesis and Characterization of Al/Co 3 O 4 Magnetic Composite Pigments with Low Infrared Emissivity and Low Lightness. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2017, 83, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Jin, Z.; He, L.; Ma, S.; Wang, C.; Mu, X.; Song, L. Synthesis of a Novel Graphene Conjugated Covalent Organic Framework Nanohybrid for Enhancing the Flame Retardancy and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Resins through Synergistic Effect. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 182, 107616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Xing, H.; Fan, Q.; Ji, X.; Yang, P. Conductive Polyaniline Coated on Aluminum Substrate as Bi-Functional Materials with High-Performance Microwave Absorption and Low Infrared Emissivity. Synth. Met. 2021, 271, 116640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Xu, C.; Tian, X.; Wang, J.; Tian, C.; Yang, B.; Qu, S.; Fan, Q. Ultra-Wideband Flexible Transparent Metamaterial with Wide-Angle Microwave Absorption and Low Infrared Emissivity. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 22108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Han, X.; Xu, P.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. The Electromagnetic Property of Chemically Reduced Graphene Oxide and Its Application as Microwave Absorbing Material. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Feng, W.; Li, Q. Beyond the Visible: Bioinspired Infrared Adaptive Materials. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, O.; Kakenov, N.; Karademir, E.; Balci, S.; Cakmakyapan, S.; Polat, E.O.; Caglayan, H.; Özbay, E.; Kocabas, C. Electrically Switchable Metadevices via Graphene. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M Houssa, A Dimoulas, A.M. 2D Materials for Nanoelectronics; Press, C., Ed.; Vol. 17.; 2016.

- Pogna, E.A.A.; Tomadin, A.; Balci, O.; Soavi, G.; Paradisanos, I.; Guizzardi, M.; Pedrinazzi, P.; Mignuzzi, S.; Tielrooij, K.-J.; Polini, M.; et al. Electrically Tunable Nonequilibrium Optical Response of Graphene. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3613–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihoglu, O.; Uzlu, H.B.; Yakar, O.; Aas, S.; Balci, O.; Kakenov, N.; Balci, S.; Olcum, S.; Süzer, S.; Kocabas, C. Graphene-Based Adaptive Thermal Camouflage. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 4541–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, J.W.; D’Aria, D.M. Emissivity of Terrestrial Materials in the 8–14 Μm Atmospheric Window. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 42, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Tareen, A.K.; Aslam, M.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Mahmood, A.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Z. Recent Developments in Emerging Two-Dimensional Materials and Their Applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 387–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Chang, H.; Guo, N.; Liu, J.; Jia, Y.; Wang, L.; Weng, Y.; et al. Flexible Mid-Infrared Radiation Modulator with Multilayer Graphene Thin Film by Ionic Liquid Gating. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 13538–13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Li, Q.; Cai, L.; Pan, M.; Ghosh, P.; Du, K.; Qiu, M. Thermal Camouflage Based on the Phase-Changing Material GST. Light Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Luo, M.; Jiang, X.; Luo, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J. Color Camouflage, Solar Absorption, and Infrared Camouflage Based on Phase-Change Material in the Visible-Infrared Band. Opt. Mater. Express 2022, 12, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kats, M.A.; Blanchard, R.; Zhang, S.; Genevet, P.; Ko, C.; Ramanathan, S.; Capasso, F. Vanadium Dioxide as a Natural Disordered Metamaterial: Perfect Thermal Emission and Large Broadband Negative Differential Thermal Emittance. Phys. Rev. X 2013, 3, 041004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvet, K.; Sauques, L.; Rougier, A. IR Electrochromic WO3 Thin Films: From Optimization to Devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2009, 93, 2045–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Xue, P.; Valenzuela, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Feng, W. Three-Dimensional Electrochromic Soft Photonic Crystals Based on MXene-Integrated Blue Phase Liquid Crystals for Bioinspired Visible and Infrared Camouflage. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2022, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S. V; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S. V; Grigorieva, I. V; Firsov, A.A. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science (80-. ). 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geim, A.K.; Novoselov, K.S. The Rise of Graphene. Nanosci. Technol. a Collect. Rev. from Nat. journals 2010, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Ren, L.; Gao, S.; Li, S. Histogram Method for Reliable Thickness Measurements of Graphene Films Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wei, X.; Kysar, J.W.; Hone, J. Measurement of the Elastic Properties and Intrinsic Strength of Monolayer Graphene. Science 2008, 321, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukleri, G.; Parthenios, J.; Papagelis, K.; Jalil, R.; Ferrari, A.C.; Geim, A.K.; Novoselov, K.S.; Galiotis, C. Subjecting a Graphene Monolayer to Tension and Compression. Small 2009, 5, 2397–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, A.H.C.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The Electronic Properties of Graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teweldebrhan, D.; Lau, C.N.; Ghosh, S.; Balandin, A.A.; Bao, W.; Calizo, I.; Miao, F. Superior Thermal Conductivity of Single-Layer Graphene. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandin, A.A. Thermal Properties of Graphene and Nanostructured Carbon Materials. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, E.; Varshney, V.; Roy, A.K. Thermal Properties of Graphene: Fundamentals and Applications. MRS Bull. 2012, 37, w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassei, J.K.; Kaner, R.B. Graphene, a Promising Transparent Conductor. Mater. Today 2010, 13, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmenko, A.B.; Van Heumen, E.; Carbone, F.; Van Der Marel, D. Universal Optical Conductance of Graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 117401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eizenberg, M.; Blakely, J.M. Carbon Monolayer Phase Condensation on Ni (111). Surf. Sci. 1979, 82, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, P.; Louw-gaume, A.E.; Kucki, M.; Krug, H.F.; Kostarelos, K.; Fadeel, B.; Dawson, K.A.; Salvati, A.; Vµzquez, E.; Ballerini, L.; et al. Classification Framework for Graphene-Based Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 7714–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, T.; Gómez-Cámer, J.L.; Bünzli, C.; Novák, P.; Trabesinger, S. The Counterintuitive Impact of Separator–Electrolyte Combinations on the Cycle Life of Graphite–Silicon Composite Electrodes. J. Power Sources 2017, 343, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S. A Review on the Separators of Liquid Electrolyte Li-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2007, 164, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, D.; Christensen, T.; Hsieh, C.-T.; Li, J. Elucidation of Separator Effect on Energy Density of Li-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A3377–A3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldroubi, S.; Brun, N.; Bou Malham, I.; Mehdi, A. When Graphene Meets Ionic Liquids: A Good Match for the Design of Functional Materials. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 2750–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Bakan, G.; Guo, H.; Ergoktas, M.S.; Steiner, P.; Kocabas, C. Reversible Ionic Liquid Intercalation for Electrically Controlled Thermal Radiation from Graphene Devices. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 11583–11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo, D.; Tittl, A.; Limaj, O.; Abajo, F.J.G. de; Pruneri, V.; Altug, H. Double-Layer Graphene for Enhanced Tunable Infrared Plasmonics. Light Sci. Appl. 2017, 6, e16277–e16277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Li, J.; Ke, H.; Du, Y.; Peng, W.; Dai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.A. Impact of Ionic Liquids on Effectiveness of Tuning the Emissivity of Multilayer Graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 26256–26263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, G.; Peng, Z.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, L.; Cao, S.; Ji, S.; Qu, G.; Zhao, L.; Wang, S.; et al. Freestanding Graphene Fabric Film for Flexible Infrared Camouflage. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Balilonda, A.; Yang, S.; Tao, X.; Chen, W. Graphene-Based Soft Actuator with Dynamic Spectrum Modulation for a Smart Thermal Surface. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 8298–8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, R.; Deng, C.; Peng, Y.; Jiang, T. Tunable Infrared Emissivity in Multilayer Graphene by Ionic Liquid Intercalation. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chao, X.; Balilonda, A.; Chen, W. Scalable van Der Waals Graphene Films for Electro-Optical Regulation and Thermal Camouflage. InfoMat 2023, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Ke, H.; Guo, X.; Cheng, S.; Lin, T.; Peng, W.; Dai, M.; Cai, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.A. Tuning Infrared Emissivity of Graphene Aerogel Through Ion Intercalation. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2022, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials for Thermal Camouflage | PROS | CONS | Ref. |

| Metallic Powders | Emissivity reduction by topological modification of the surface; Low cost |

Rigid structure; High reflectivity; Oxidation; No dynamic camouflage |

[7,8,9,10] |

| Metal-oxide | Excellent stability; Dynamic camouflage; Multispectral stealth |

High cost; High emissivity |

[15,16,17,18] |

| Metamaterials | Low emissivity modulation; Dynamic camouflage; Multispectral stealth |

High cost | [19,20] |

| Thin metallic film | Very large emittance modulation | Slow response time; Limited lifetime and cyclability |

[21,22,23,24,25] |

| Graphene and graphene-like materials | Dynamic camouflage; Multispectral stealth |

High emissivity | [5,26,27] |

| Active layer | Thickness [nm] |

Electrolyte (volume) |

Separator | Back electrode |

Bias [V] |

Rs [Ω/sq] |

Vth [V] |

Treal [°C] |

Tapp [°C] |

ε [-] |

tR [s] |

Ref |

| MLG | 34 | [DEME]+[TFSI]- | PE | Au | 0 to 3.5 | 33 - 0.6 | 1.5 V | 55° | N.A. | 0.76 - 0.33 | N.A. | [40] |

| MLG | 50-70 | [DEME]+[TFSI]- (50 µL) |

PE | MLG | 0 to 4.0 | 11 - 4 | 2.0 V | 35° | ~ 31° - 28° | 0.57 - 0.41 | <1s | [71] |

| MLG | - | [EMIm]+[NTf2]- | PP-PE-PP | Cu | 0 to 4.0 | N.A. | 2.0 V | 65° | ~ 48° - 32° | 0.54 - 0.02 | N.A. | [68] |

| MLG | 90-100 | [HMIm]+[NTf2]- | PP-PE-PP | Au | 0 to 4.0 | N.A. | 2.0 V | 65° | ~ 50° - 32° | 0.47 - 0.10 | ~ 1.8÷1.9 | [43] |

| MLG | 90-100 | [HMIm]+[NTf2]- | PP-PE-PP | MLG | 0 to 4.0 | N.A. | 2.5 V | 65° | ~ 50°- 30° | 0.51 - 0.14 | ~ 1.7 | [43] |

| MLG | 90-100 | [HMIm]+[NTf2]- | PP-PE-PP | Cu | 0 to 4.0 | N.A. | 3.0 V | 65° | N.A | 0.50 - 0.10 | N.A | [43] |

| MLG | - | [AMIM]+[TFSI]- | Lens cleaning tissue | Stainless steel | 0 to 3.8 | 50 - N.A. | 2.2 V | N.A | ~ 41° - 31° | 0.85 - 0.33 | N.A. | [66] |

| MLG | N.A. | [EMIM]+[TFSI]- (20 µL) |

PE | Au | 0 to 3.3 | 28 - 3 | 2.7 V | N.A | N.A | 0.65 - 0.35 | N.A | [70] |

| FS-GFF | 90 | [BMIM]+[PF6]- | Cellulose | Au | 0 to 5 | 50 - N.A. | 3.0 V | N.A | ~ 36° - 27° | 0.79 - 0.68 | ~25 | [69] |

| vdWGRfs | 136 | [EMIM]+[TFSI]- (20 µL) |

PTFE | Cu | 0 to 5.5 | 98 - N.A. | 3.0 V | 38° | ~ 31° - 27° | 0.55 - 0.18 | ~6 | [72] |

| GAs 20% porosity |

60000 | [HMIm]+[NTf2]- | PP-PE-PP | Cu | 0 to 2.6 | N.A. | 2.6 V | 69° | ~ 68° - 56° (@60% strain) | 0.71 - 0.40 | ~180 | [73] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).