Submitted:

09 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

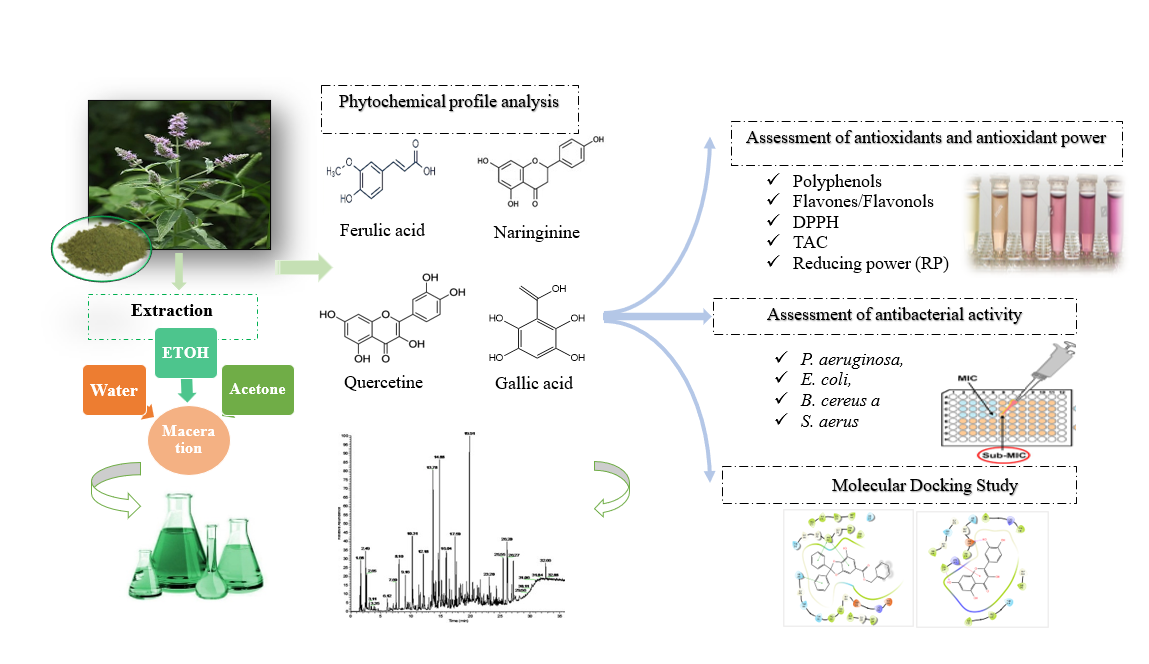

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preliminary Solvent Secerning

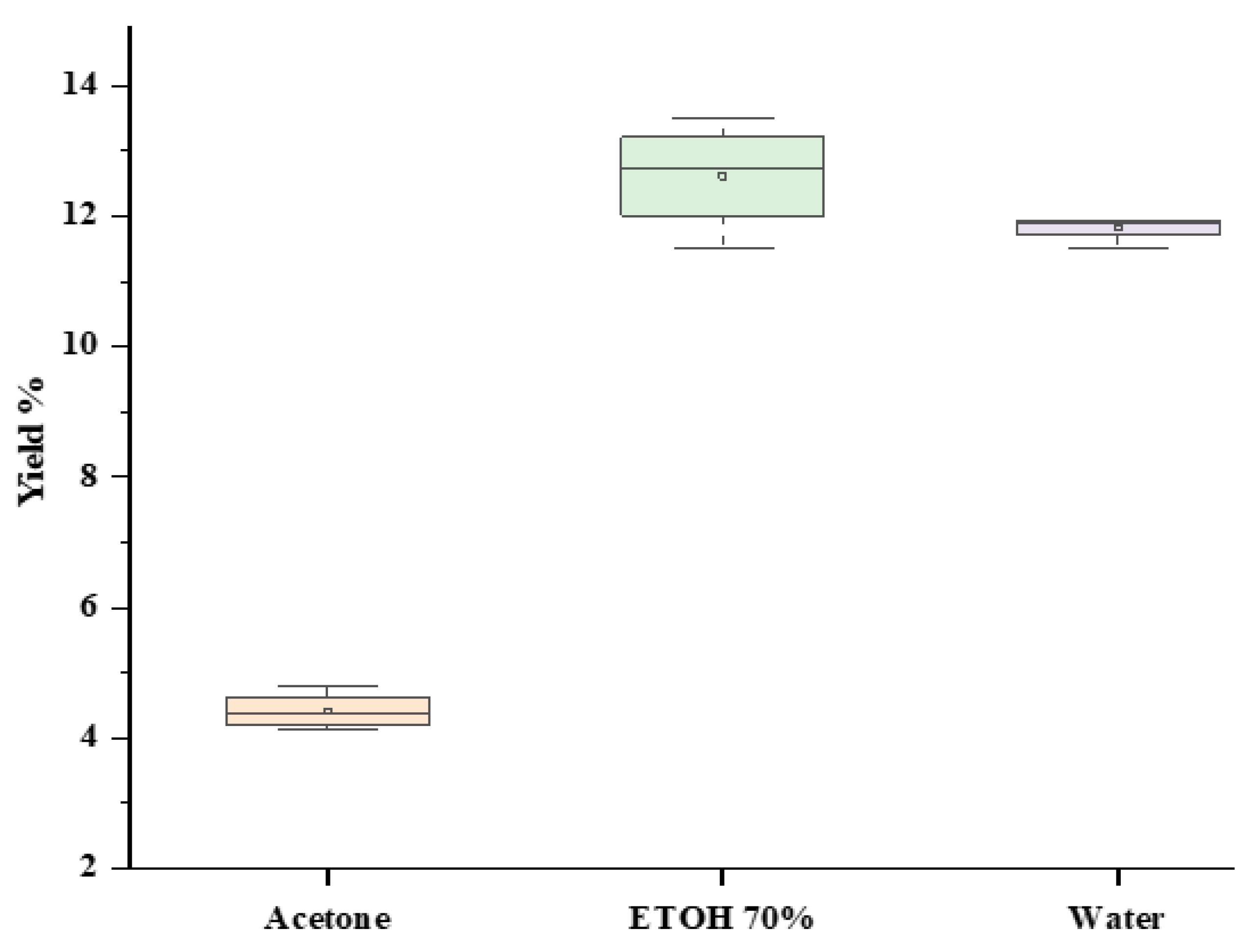

2.2. Solvent Polarity Effect on the Extraction Yield

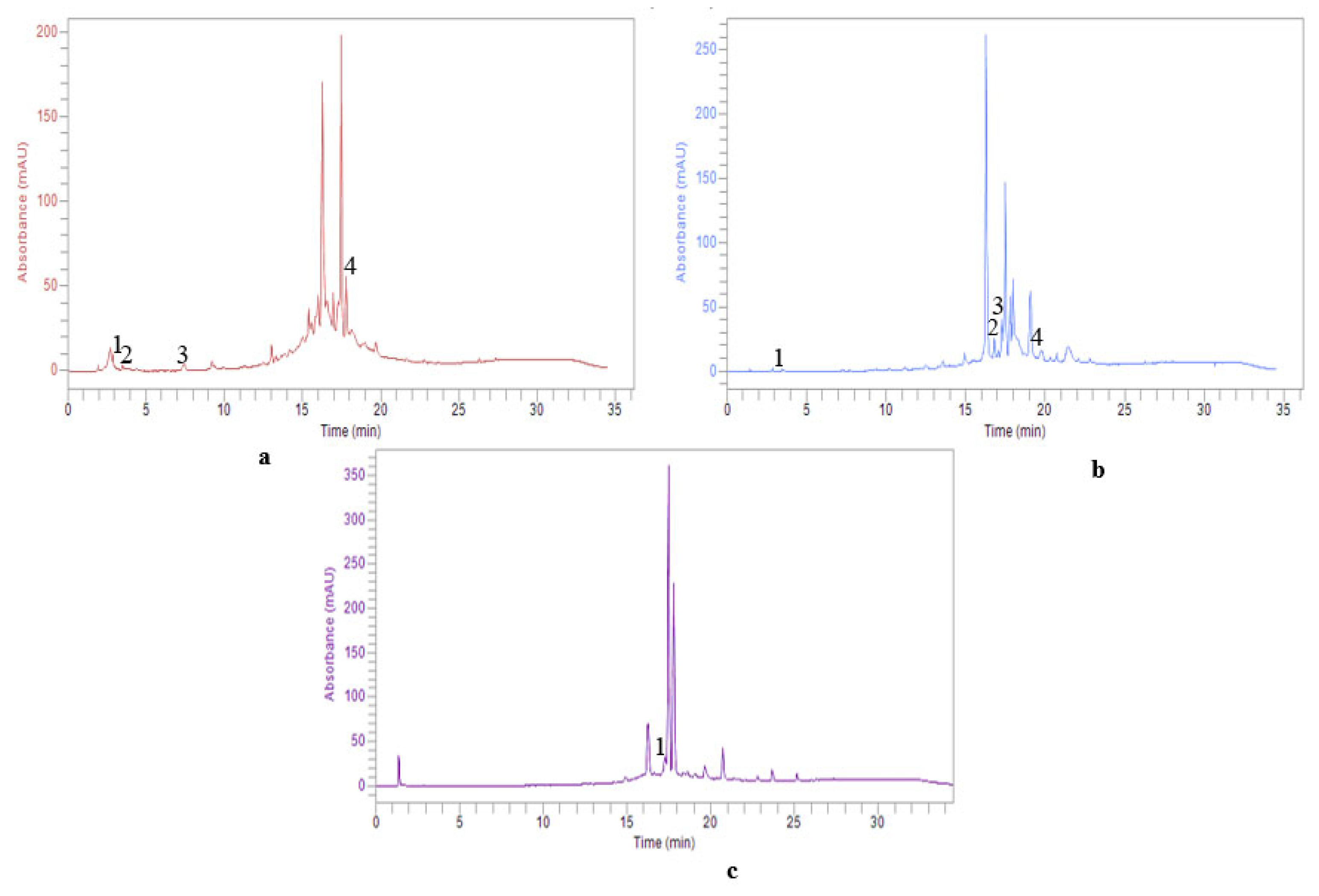

2.3. HPLC–DAD expLoration of Individual Phenolic Composition

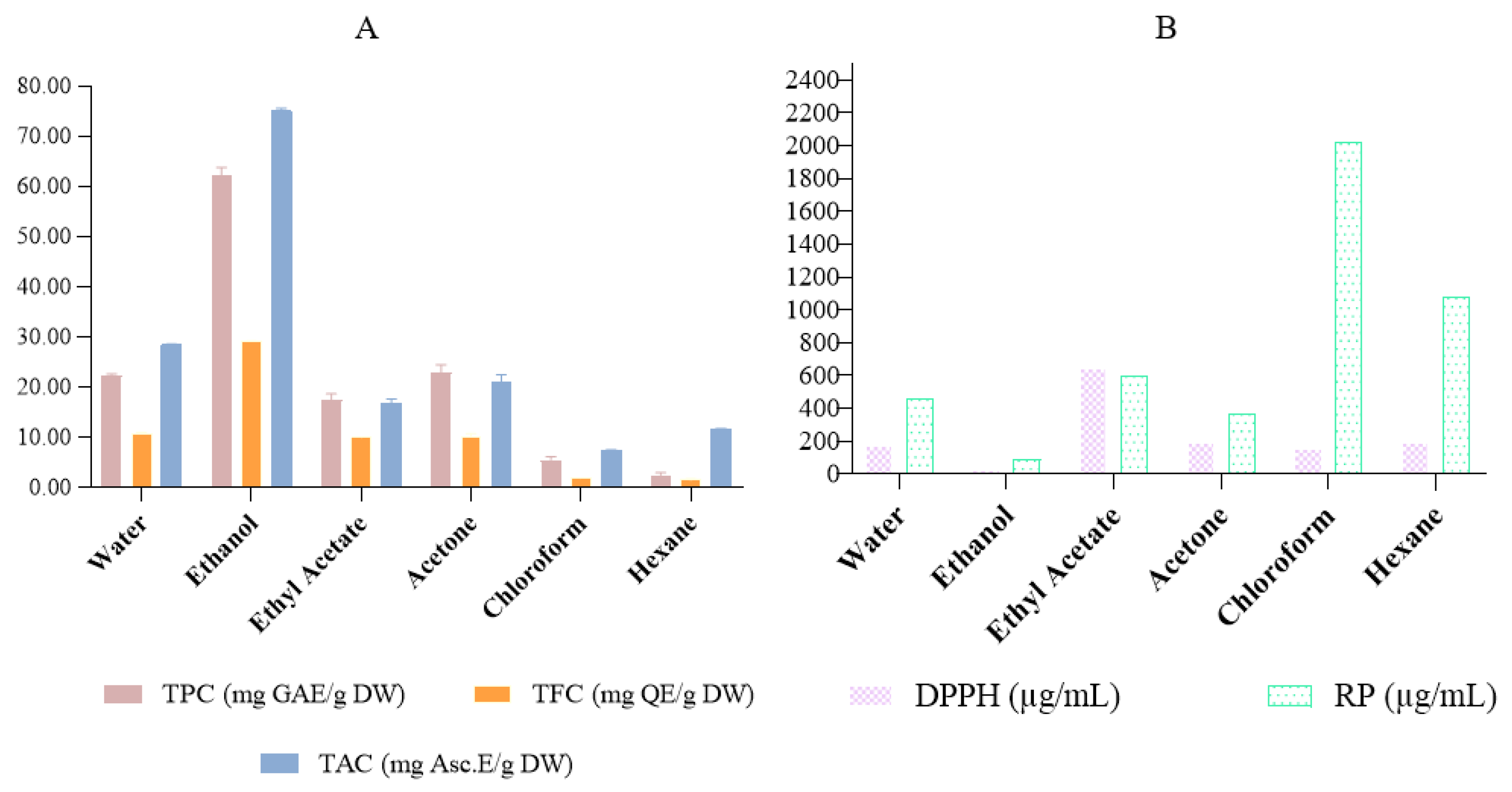

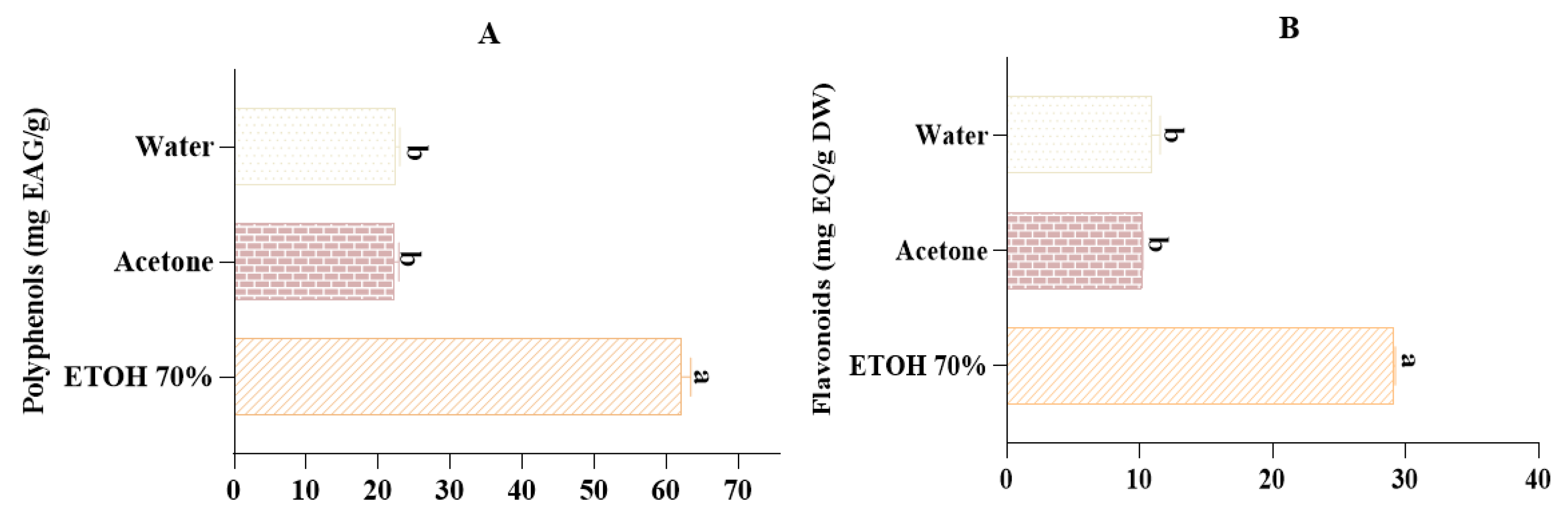

2.4. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content

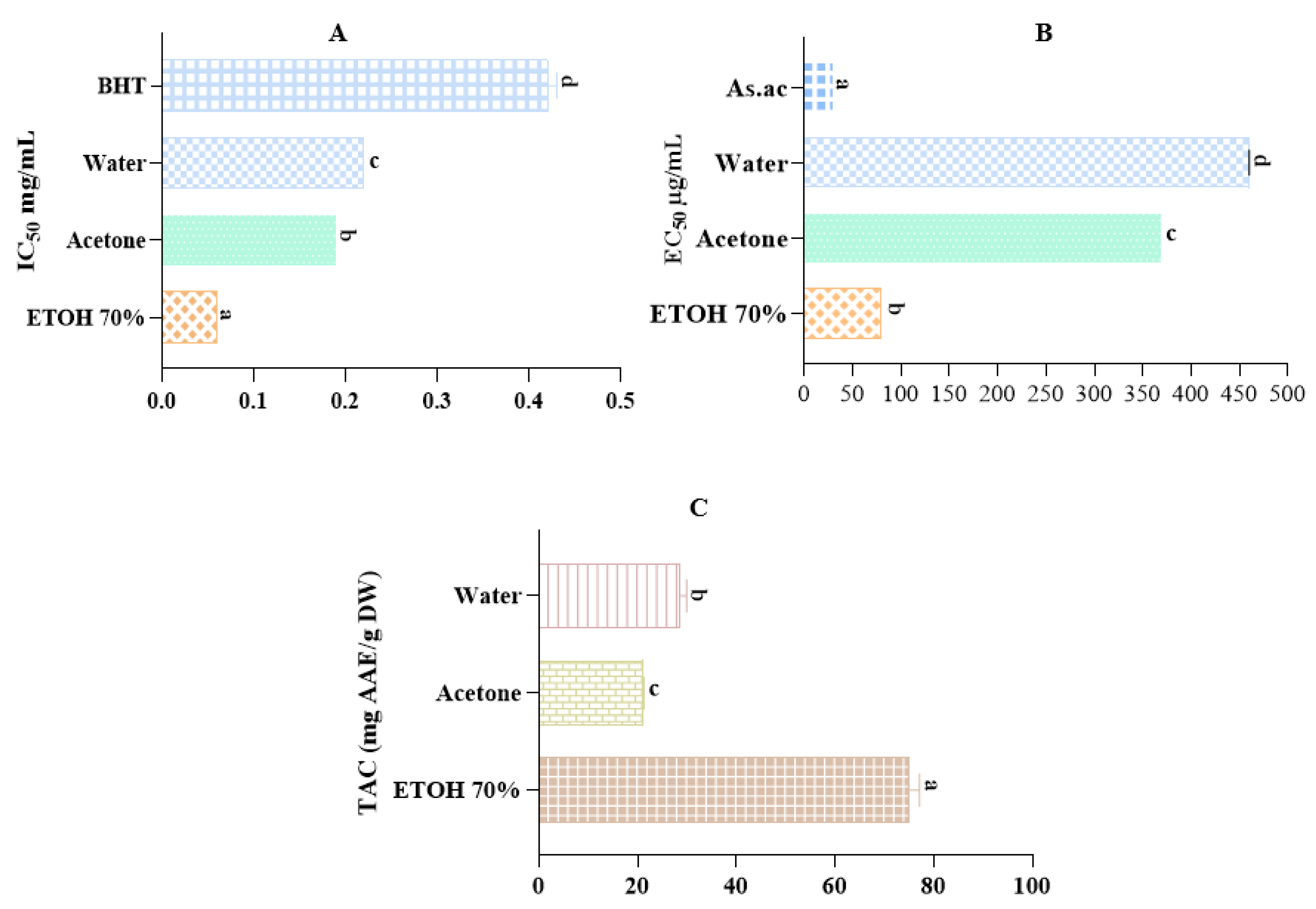

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.6. Assessment of the Antibacterial Capacity

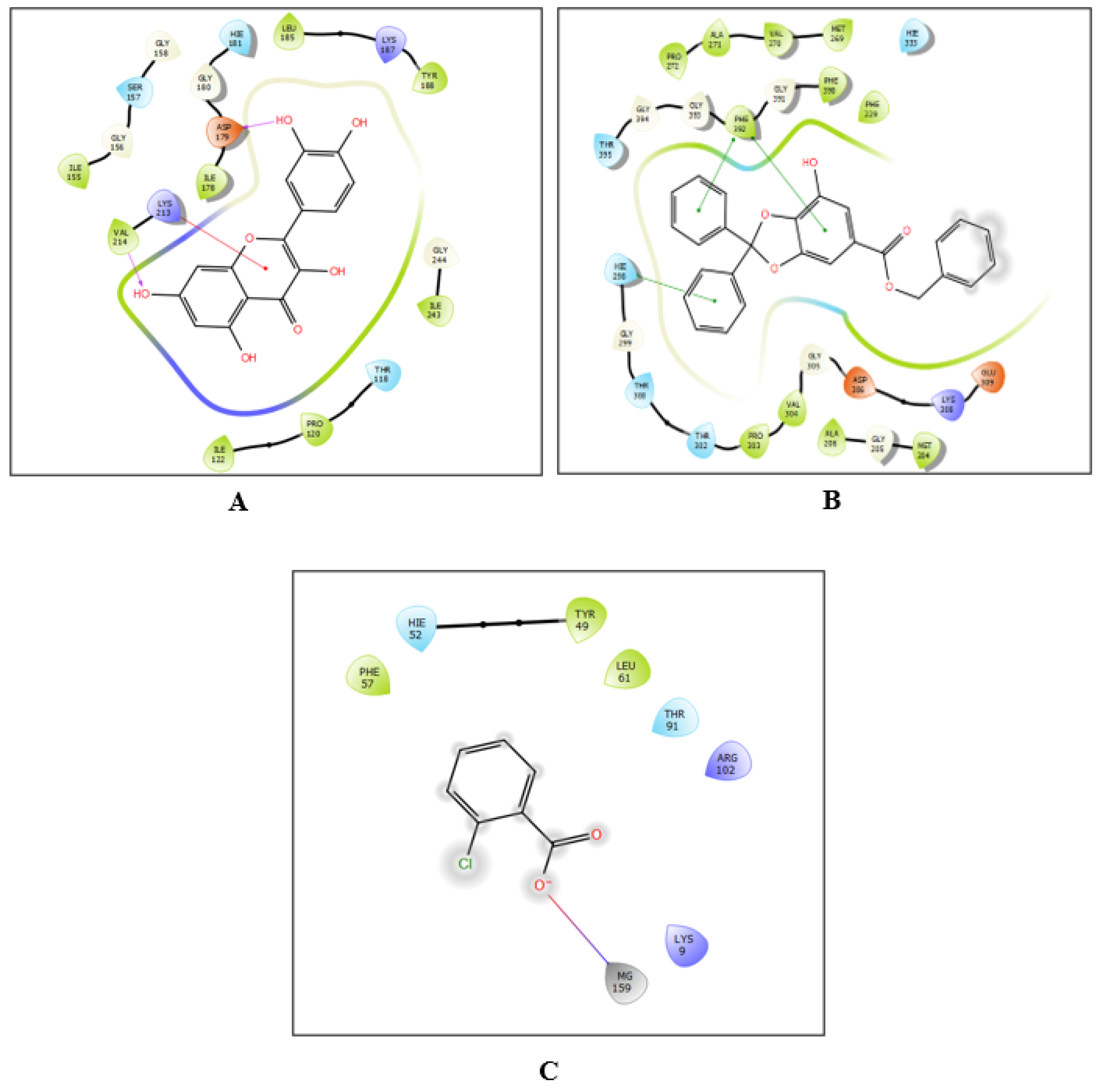

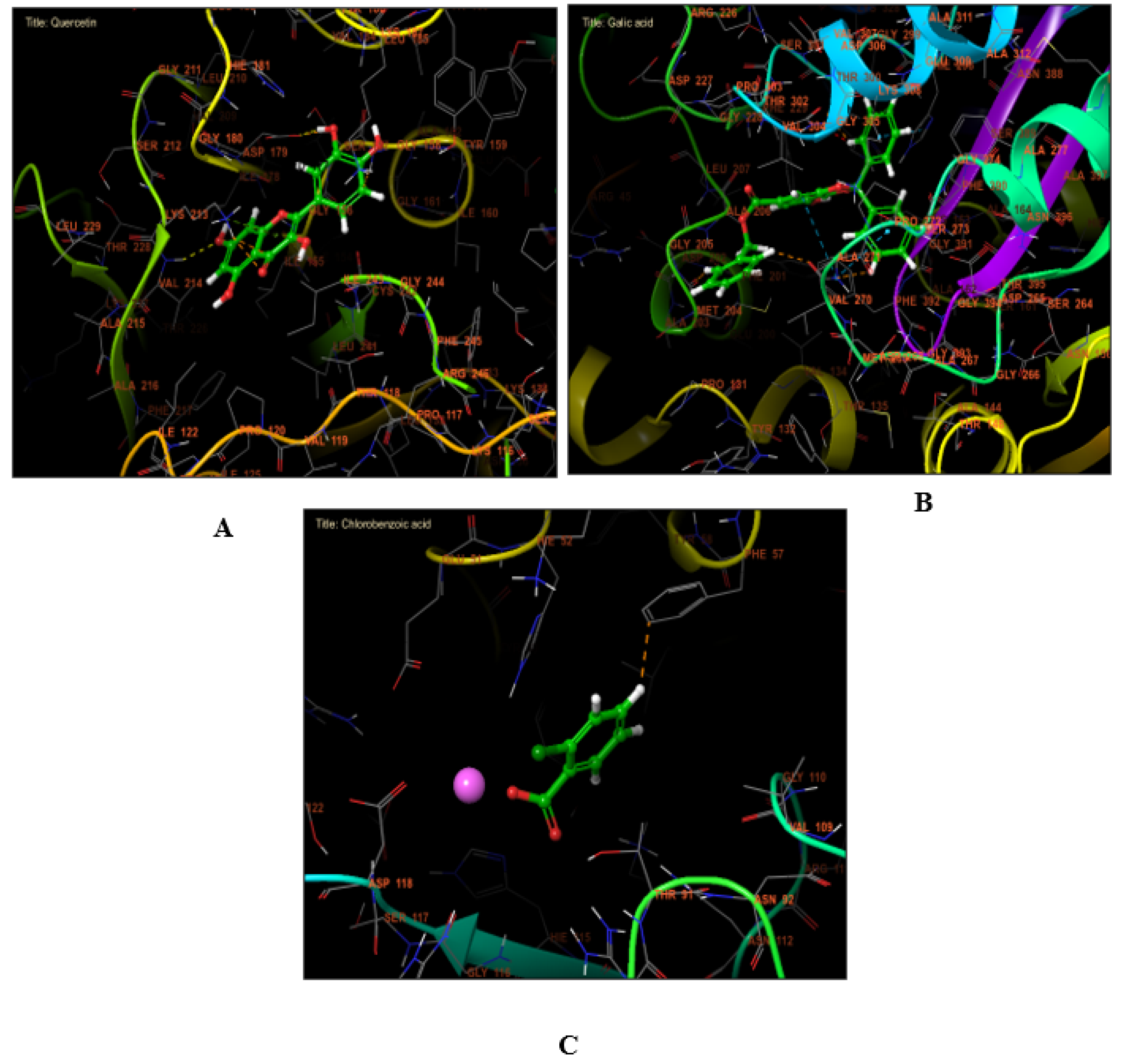

2.7. Molecular Docking Assessment

3. Statistical analysis

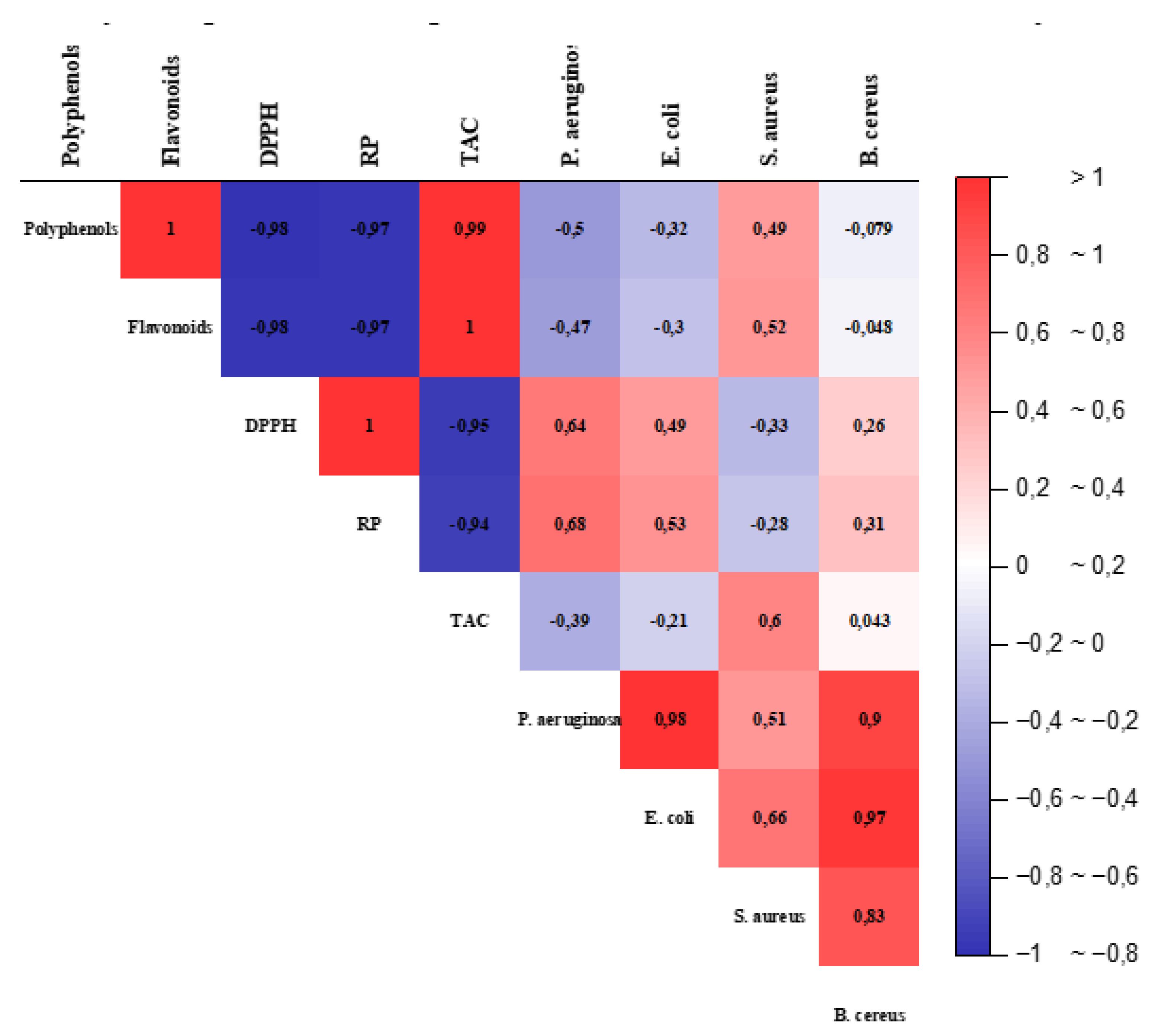

3.1. Correlation Analysis

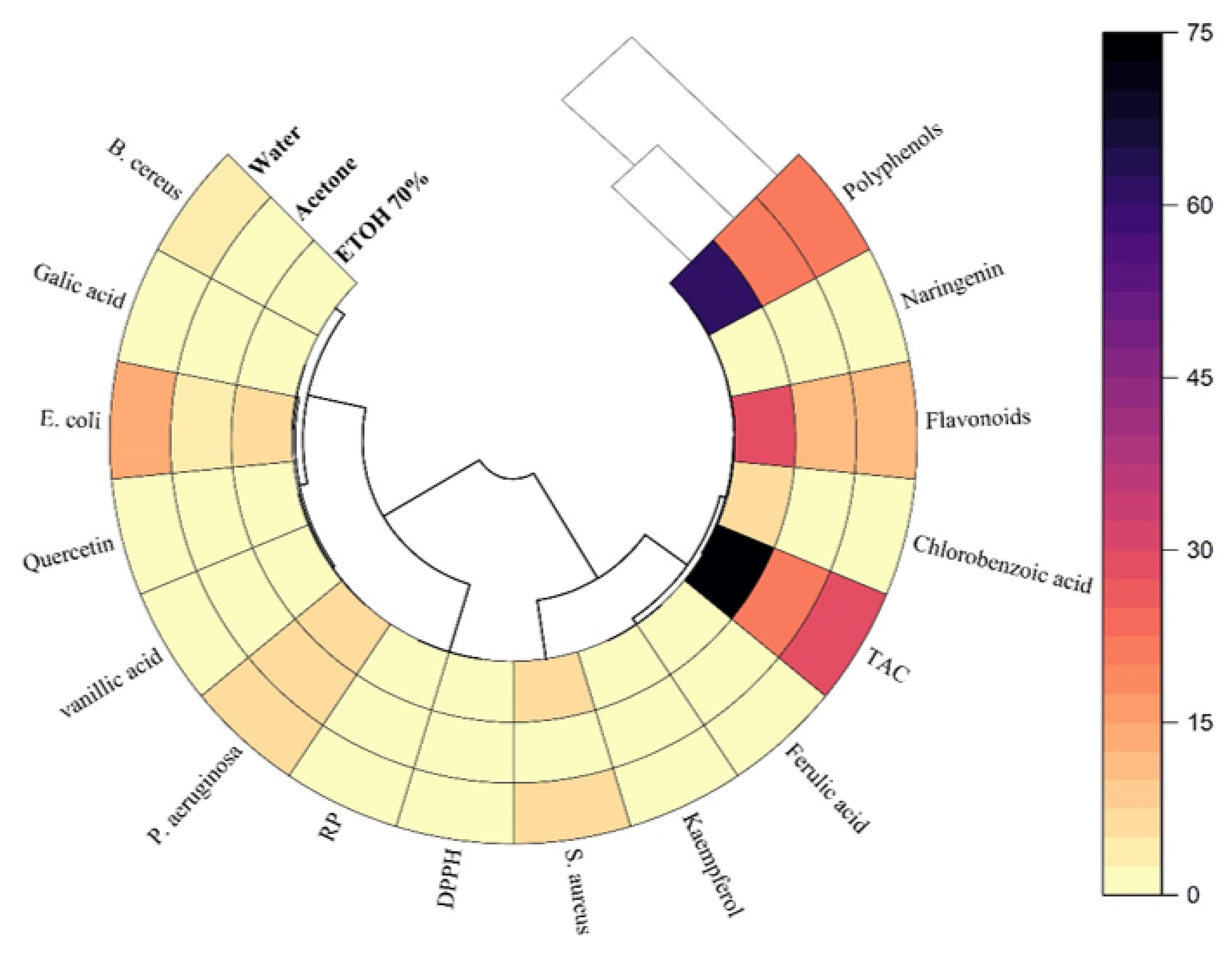

3.2. Polar Heatmap Analysis

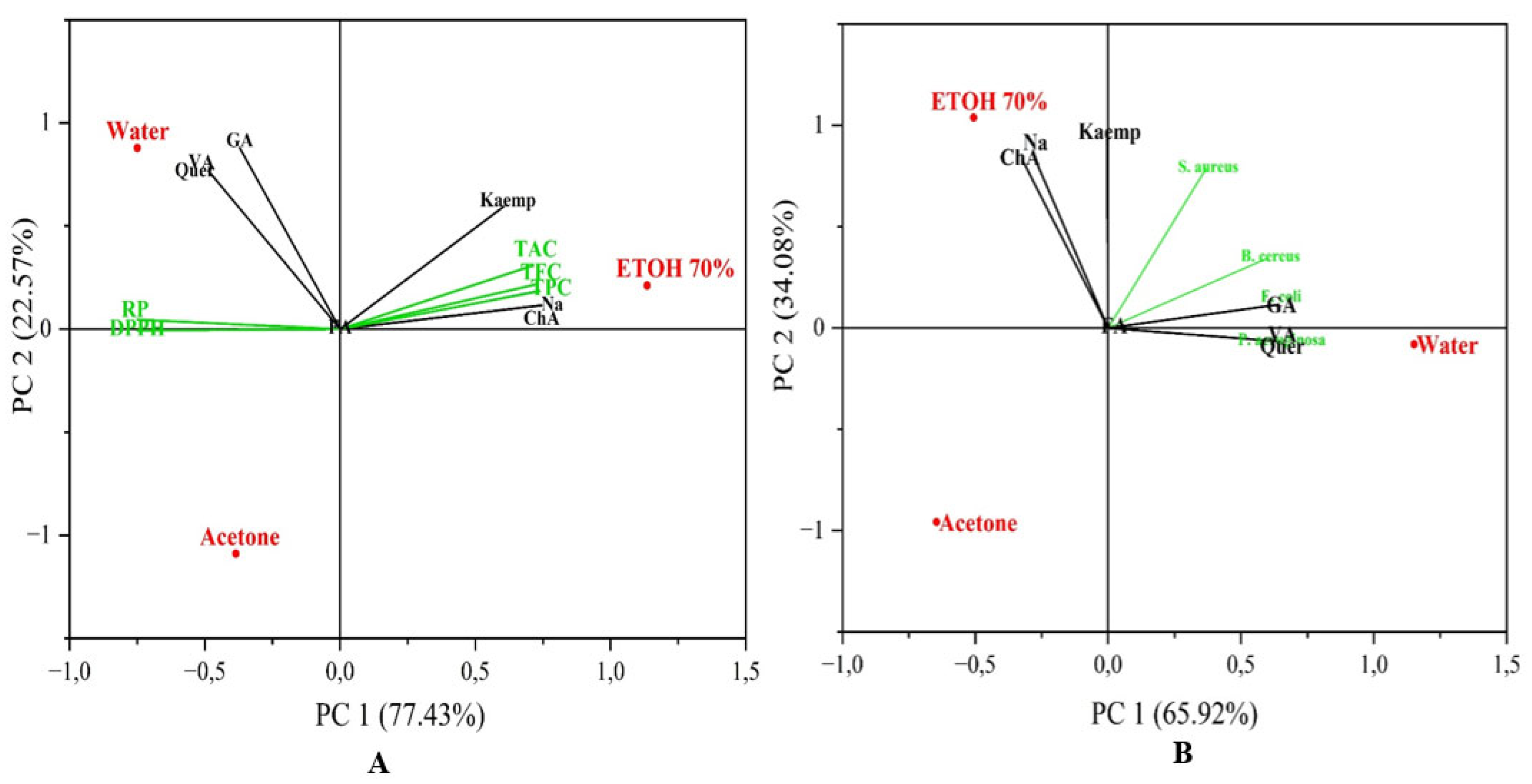

3.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Botanical Material

4.2. Preparation of Extracts

4.3. Estimating the Yield of Extraction

4.4. Identification of Individual Phenolic Components using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with a Diode Array Detector (HPLC-DAD)

4.5. Assessment of Total Phenolic Content

4.6. Assessment of Total Flavonoid Content

4.7. In Vitro Antioxidant Capabilities

4.8. Assessment of Antibacterial Capacity

4.8.1. Microbial Testing

4.8.2. Determination of Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

4.8.3. Assessment of the Lowest Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

4.9. Molecular Docking Study

4.9.1. Protein Preparation

4.9.2. Ligand Preparation

4.9.3. Receptor Grid Generation

4.9.4. Performing Molecular Docking

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

References

- Tourabi, M.; Nouioura, G.; Touijer, H.; Baghouz, A.; El Ghouizi, A.; Chebaibi, M.; Bakour, M.; Ousaaid, D.; Almaary, K.S.; Nafidi, H.-A.; et al. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Insecticidal Properties of Chemically Characterized Essential Oils Extracted from Mentha longifolia: in Vitro and in Silico Analysis. Plants 2023, 12, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, S. Prospective Role in Treatment of Major Illnesses And Potential Benefits As A Safe Insecticide And Natural Food Preservative of Mint (Mentha Spp.): A Review. Asian Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences 2014, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Baek, S.-A.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Park, S. Metabolic Profiling of Nine Mentha Species and Prediction of Their Antioxidant Properties Using Chemometrics. Molecules 2019, 24, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, A.; Rustaiyan, A.; Masoudi, S.; Nadji, K. Composition of the Essential Oils of Mentha aquatica L. and Nepeta Meyeri Benth. from Iran. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2006, 18, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenwald, J.; Brendler, T.; Jaenicke, C. PDR for Herbal Medicines (Physicians’ Desk Reference). Montvale, New Jersey: Medical Economics Company 2000.

- Singh, P.; Pandey, A.K. Prospective of Essential Oils of the Genus Mentha as Biopesticides: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimzadeh, M.; Nabavi, S.M.; Nabavi, S.F.; Eslami, B. Biological Activity of Mentha aquatica l. Pharmacologyonline 2010, 2, 611–619. [Google Scholar]

- Mkaddem, M.; Bouajila, J.; Ennajar, M.; Lebrihi, A.; Mathieu, F.; Romdhane, M. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Mentha (longifolia L. and Viridis ) Essential Oils. Journal of Food Science 2009, 74, M358–M363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, O.R.; Macias, R.I.R.; Domingues, M.R.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Cardoso, S.M. Hepatoprotection of Mentha aquatica L., Lavandula dentata L. and Leonurus cardiaca L. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Hussain, S.; Gupta, M.; Saxena, A.K. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Extracts of Mentha spp. against Human Cancer Cells.

- Gul, H.; Abbas, K.; Qadir, M.I. Gastro-Protective Effect of Ethanolic Extract of Mentha longifolia in Alcohol- and Aspirin-Induced Gastric Ulcer Models. Bangladesh J Pharmacol 2015, 10, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatiha, B.; Khodir, M.; Farid, D.; Tiziri, R.; Karima, B.; Sonia, O.; Mohamed, C. Optimisation Of Solvent Extraction Of Antioxidants (Phenolic Compounds) From Algerian Mint (Mentha spicata L.).

- Iloki-Assanga, S.B.; Lewis-Luján, L.M.; Lara-Espinoza, C.L.; Gil-Salido, A.A.; Fernandez-Angulo, D.; Rubio-Pino, J.L.; Haines, D.D. Solvent Effects on Phytochemical Constituent Profiles and Antioxidant Activities, Using Four Different Extraction Formulations for Analysis of Bucida buceras L. and Phoradendron californicum. BMC Research Notes 2015, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, T.; Mićić, N.; Potkonjak, A.; Milanov, D.; Dodić, J.; Trivunović, Z.; Popović, B.M. The Evaluation of Phenolic Content, in Vitro Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Mentha piperita Extracts Obtained by Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Food Chemistry 2021, 362, 130226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourabi, M.; Metouekel, A.; Ghouizi, A.E.L.; Jeddi, M.; Nouioura, G.; Laaroussi, H.; Hosen, M.E.; Benbrahim, K.F.; Bourhia, M.; Salamatullah, A.M.; et al. Efficacy of Various Extracting Solvents on Phytochemical Composition, and Biological Properties of Mentha longifolia L. Leaf Extracts. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 18028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapornik, B.; Prošek, M.; Golc Wondra, A. Comparison of Extracts Prepared from Plant By-Products Using Different Solvents and Extraction Time. Journal of Food Engineering 2005, 71, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodor, E.D.; Gatea, F.; Camelia, A.; Radulescu, C.; Chira, A.; Radu, G. Polyphenols, Radical Scavenger Activity, Short-Chain Organic Acids and Heavy Metals of Several Plants Extracts from `Bucharest Delta`. Chemical Papers 2015, 69, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naczk, M.; Shahidi, F. Phenolics in Cereals, Fruits and Vegetables: Occurrence, Extraction and Analysis. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2006, 41, 1523–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masibo, M.; He, Q. Major Mango Polyphenols and Their Potential Significance to Human Health. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2008, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, A.; Sultana, B.; Hussain, A.; Anwar, F.; Ahmad, N. Antioxidant Potential, Phenolics Content and Antimicrobial Attributes of Selected Medicinal Plants. Pak. J. Anal. Environ. Chem. 2021, 22, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorman, H.J.D.; Koşar, M.; Kahlos, K.; Holm, Y.; Hiltunen, R. Antioxidant Properties and Composition of Aqueous Extracts from Mentha Species, Hybrids, Varieties, and Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 4563–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoai, L.V.N.; Quoc, L.P.T.; Hoang, H.T.; Raes, K.; Mai, D.S.; Thien, L.T. Extraction of Polyphenols from Mentha aquatica Linn. Var. Crispa. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2023, 88, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti, F.; Sosa, S.; Marrelli, M.; Menichini, F.; Statti, G.A.; Uzunov, D.; Tubaro, A.; Menichini, F.; Loggia, R.D. In Vivo Anti-Inflammatory and in Vitro Antioxidant Activities of Mediterranean Dietary Plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2008, 116, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, N.Q.N.; Duc, L.T.; Minh, L.V.; Tien, L.X. Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Activity of Aqueous and Ethanolic Extracts of Mentha aquatica L. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 991, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in Vivo and in Vitro Methods Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajimehdipoor, H.; Shahrestani, R.; Shekarchi, M. Investigating the Synergistic Antioxidant Effects of Some Flavonoid and Phenolic Compounds.

- Ferhat, M.; Erol, E.; Beladjila, K.A.; Çetintaş, Y.; Duru, M.E.; Öztürk, M.; Kabouche, A.; Kabouche, Z. Antioxidant, Anticholinesterase and Antibacterial Activities of Stachys Guyoniana and Mentha aquatica. Pharmaceutical Biology 2017, 55, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konaté, K.; Mavoungou, J.F.; Lepengué, A.N.; Aworet-Samseny, R.R.; Hilou, A.; Souza, A.; Dicko, M.H.; M’Batchi, B. Antibacterial Activity against β- Lactamase Producing Methicillin and Ampicillin-Resistants Staphylococcus aureus: Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) Determination. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2012, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakat, S.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.R.; Allehdan, S.; Olaimat, A.N.; Holley, R.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Amurca (Olive Oil Lees) Extract against Selected Foodborne Pathogens. Food Sci. Technol (Campinas) 2015, 35, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, A.; Ożarowski, M.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Activity of Some Flavonoids and Organic Acids Widely Distributed in Plants. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Q.; Wei, S.; Su, H.; Zheng, S.; Xu, S.; Liu, M.; Bo, R.; Li, J. Bactericidal Activity of Gallic Acid against Multi-Drug Resistance Escherichia coli. Microbial Pathogenesis 2022, 173, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.S.; Panda, S.K.; Navitha, M.; Asha, K. .. K.; Anandan, R.; Mathew, S. Vanillic Acid and Coumaric Acid Grafted Chitosan Derivatives: Improved Grafting Ratio and Potential Application in Functional Food. J Food Sci Technol 2015, 52, 7153–7162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Martínez, F.J.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Encinar, J.A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.C.; Micol, V. Antimicrobial Capacity of Plant Polyphenols against Gram-Positive Bacteria: A Comprehensive Review. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 27, 2576–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, J.A.; Kevers, C.; Pincemail, J.; Defraigne, J.O.; Dommes, J. Extraction Conditions Can Greatly Influence Antioxidant Capacity Assays in Plant Food Matrices. Food Chemistry 2012, 130, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloff, J.N. Which Extractant Should Be Used for the Screening and Isolation of Antimicrobial Components from Plants? Journal of Ethnopharmacology 1998, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Rocha, K.M.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Larrosa-Pérez, M.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R. Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids in Acetonic Extract from Quince (Cydonia oblonga mill.): Nutraceuticals with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential. Molecules 2022, 27, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, F.M.; Couto, J.A.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Tóth, I.V.; Rangel, A.O.S.S.; Hogg, T.A. Cell Membrane Damage Induced by Phenolic Acids on Wine Lactic Acid Bacteria. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2009, 135, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Ma, L.; Wen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S. Studies of the in Vitro Antibacterial Activities of Several Polyphenols against Clinical Isolates of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2014, 19, 12630–12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtar, M.; Ginestra, G.; Youcefi, F.; Filocamo, A.; Bisignano, C.; Riazi, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Selected Polyphenols and Capsaicinoids Identified in Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and Their Possible Mode of Interaction. Curr Microbiol 2017, 74, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Dong, J.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, M.; Tan, W.; Deng, X.; et al. Inhibition of α-Toxin Production by Subinhibitory Concentrations of Naringenin Controls Staphylococcus aureus Pneumonia. Fitoterapia 2013, 86, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matejczyk, M.; Świsłocka, R.; Golonko, A.; Lewandowski, W.; Hawrylik, E. Cytotoxic, Genotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of Caffeic and Rosmarinic Acids and Their Lithium, Sodium and Potassium Salts as Potential Anticancer Compounds. Advances in Medical Sciences 2018, 63, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tourabi, M.; EL Ghouizi, A.; Nouioura, G.; Faiz, K.; Fatemi, H.EL.; Elyagoubi, K.; Lyoussi, B.; Derwich, E.H. Phenolic Profile, Acute and Subacute Toxicity of an Aqueous Extract from Moroccan Mentha longifolia L. Aerial Part in Swiss Albino Mice Model. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2023, 117293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadipe, V.; Mongalo, N.; Opoku, A. In Vitro Evaluation of the Comprehensive Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Curtisia dentata (Burm.f) C.A. Sm: Toxicological Effect on the Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK293) and Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HepG2) Cell Lines. EXCLI J 2015, 14, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachiri, L.; Echchegadda, G.; Ibijbijen, J.; Nassiri, L. Etude Phytochimique Et Activité Antibactérienne De Deux Espèces De Lavande Autochtones Au Maroc : «Lavandula stoechas L. et Lavandula dentata L.». European Scientific Journal, ESJ 2016, 12, 313–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, Y.E.; Mahraz, A.M.; Beniaich, G.; Mssillou, I.; Chebaibi, M.; Jardan, Y.A.B.; Lahkimi, A.; Nafidi, H.-A.; Aboul-Soud, M.A.M.; Bourhia, M.; et al. Essential Oils of Origanum compactum Benth: Chemical Characterization, in Vitro, in Silico, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Activities. Open Chemistry 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahabi, S.; Loukili, E.H.; Daoudi, N.E.; Chebaibi, M.; Ramdani, M.; Rahhou, I.; Bnouham, M.; Fauconnier, M.-L.; Hammouti, B.; Rhazi, L.; et al. Study of the Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant Properties, and In Vitro Anti-Diabetic Efficacy of Gracilaria bursa-pastoris Extracts. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrati, F.E.-Z.; Elmadbouh, O.H.M.; Chebaibi, M.; Soufi, B.; Conte, R.; Slighoua, M.; Saleh, A.; Al Kamaly, O.; Drioiche, A.; Zair, T.; et al. Evaluation of the Toxicity of Caralluma europaea (C.E) Extracts and Their Effects on Apoptosis and Chemoresistance in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2023, 41, 8517–8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Area % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standards | MF | RT | Water | EtOH 70% | Acetone | |

| Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | 2.89 | 1.10 | 0.22 | nd | |

| Vanillic acid | C8H8O4 | 7.428 | 1.43 | nd | nd | |

| Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 12.236 | nd | nd | nd | |

| Chlorobenzoic acid | C7H5ClO2 | 16.799 | nd | 5.61 | 0.43 | |

| Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 3.307 | 0.39 | nd | nd | |

| Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 17.130 | nd | 2.45 | nd | |

| Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 18.132 | 0.39 | 0.9 | nd | |

| EtOH 70% | Acetone | Water | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | Effect | MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | Effect | MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | Effect |

| Gram-negative Bacteria | ||||||||||||

| P. aeruginosa | 6.25±0.00 | ND | - | - | 6.25±0.00 | ND | _ | _ | 6.37±0.16 | ND | _ | _ |

| E. coli | 6.25±0.07 | ND | - | - | 4.68±0.0 | ND | _ | _ | 12.60±0.00 | ND | _ | _ |

| Gram-positive Bacteria | ||||||||||||

| S. aureus | 6.18±0.08 | 50 ±2.03 | 8.08±0.43 | Bacteriostatic | 1.56±0.11 | 1.56±0.33 | 1 | Bactericidal | 6.25±0.10 | 6.25±1 | 1±0.0 | Bactericidal |

| B. cereus | 1.78±0.55 | 50 ±1.07 | 28.07 | Bacteriostatic | 0.78±0.05 | 0.78±0.25 | 1 | Bactericidal | 3.12±0.06 | 25±0.0 | 8.08 ±0.18 | Bacteriostatic |

| Glide score (kcal/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant activity | Antibacterial activity | ||

| 2CDU | 1FJ4 | 3Q8U | |

| Chlorobenzoic acid | -6.084 | -6.496 | -8.448 |

| Ferulic acid | -5.401 | -6.558 | -7.933 |

| Gallic acid | -4.978 | -7.24 | -5.339 |

| Kaempferol | -5.543 | -5.959 | -8.984 |

| Naringenin | -6.181 | -6.336 | -8.209 |

| Quercetin | -6.587 | -5.929 | -8.991 |

| Vanillic acid | -6.12 | -6.217 | -8.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).