2. Materials and Methods

The short version of the CCAS (13 items) is evaluated in this article, hence the acronym CCAS-13. According to its developers, the CCAS-13 is made up of eight items measuring "cognitive and emotional impairment" and five items measuring "functional impairment". Responses are based on a 5-point Likert-type frequency scale ("never", "rarely", "sometimes", "often" and "always").

Data was retrieved from:

https://osf.io/m3ygz/ for 905 respondents of Mouguiama-Daouda et al. [

16] study 2. Data from 873 respondents in Heeren et al. [

24] were retrieved from:

https://osf.io/2r659/. The data are made available by the researchers under the "CC-By attribution 4.0 International" license.

Data analysis was performed with the MIRT package [

34] on R software [

35], version 4.3.0. The Graded Response Model (GRM) [

36] was used. This model is suitable for the analysis of ordinal data, particularly Likert scales [

37]. It is also more flexible than other IRT models in that it allows the discrimination parameter to be estimated for each item [

38]. Statistical analyses of the data were carried out in two stages: 1) tests of goodness of fit of models 2) verification of the psychometric properties of the chosen model.

For the first stage, four models were tested: the unidimensional model, the multidimensional 2- and 3-factor model, and the bifactorial model. Model fit was tested using the limited information goodness-of-fit statistic

M2 [

39]. This test is more appropriate than the Pearson’s test statistic χ² especially in the context of IRT models [

39]. The

M2 test belongs to the limited information test category. These tests were designed to solve the problem faced by full information tests like the χ²: they depend on all the information in the contingency table, especially in models with many variables, where the probability of combining certain categories is becoming increasingly rare. Indeed, according to Steinberg & Thissen [

40], for a number of categories greater than or equal to 5, the fit approximation becomes invalid for any model as soon as the number of items exceeds six, regardless of sample size. One of the major interests of IRT is to tackle the problem of probability sparsity by examining the sample in terms of how participants responded to difficult answers [

41]. The idea behind limited-information tests is to reduce the dependence on probabilities for rare response combinations [

42], which can improve the power of the tests and the accuracy of the model fit assessment. Probability boxes removed from the contingency table are, in fact, more likely to appear (see [

43] for more on the difference between limited-information and full-information tests).

Apart from the

M2 test, we also consulted the values of other important indicators. In particular, we followed the recommendations of Maydeu-Olivares and Joe [

44] that an RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) of less than 0.089 and a SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) of less than 0.05 are acceptable model fits for the IRT. We also took into account the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI). They range from 0 to 1, indicating that model fit is acceptable when their respective values are above .90, and that model fit is excellent when their respective values are above .95 [

45,

46]. We have also reported the values of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [

47]. This indicator, which incorporates complexity and level of fit into its equation, is useful when selecting the best model from among several plausible ones [

48]. A low AIC value indicates a better model [

49].

Once the most suitable model had been selected, the psychometric qualities of the chosen model were checked. For each item, we evaluated the parameters of discrimination (noted

a) and difficulty (noted

b1,

b2,

b3,

b4 respectively relative to the 50% probability of choosing “rarely” over “never”, then “sometimes” over “rarely”, then “often” over “sometimes” and finally “always” over “often”). Based on the principle that, according to IRT, the latent trait is represented by a continuum going from a low level to a high level, the discrimination parameter (

a) determines how well an item is able to discriminate individuals along the latent trait continuum [

50]. According to Baker [

51], item discrimination becomes acceptable when the

a value is greater than or equal to 0.5. Difficulty parameters (

b1...4) are based on thresholds at which an individual has a 50% probability or more of selecting any category of an item [

52]. The

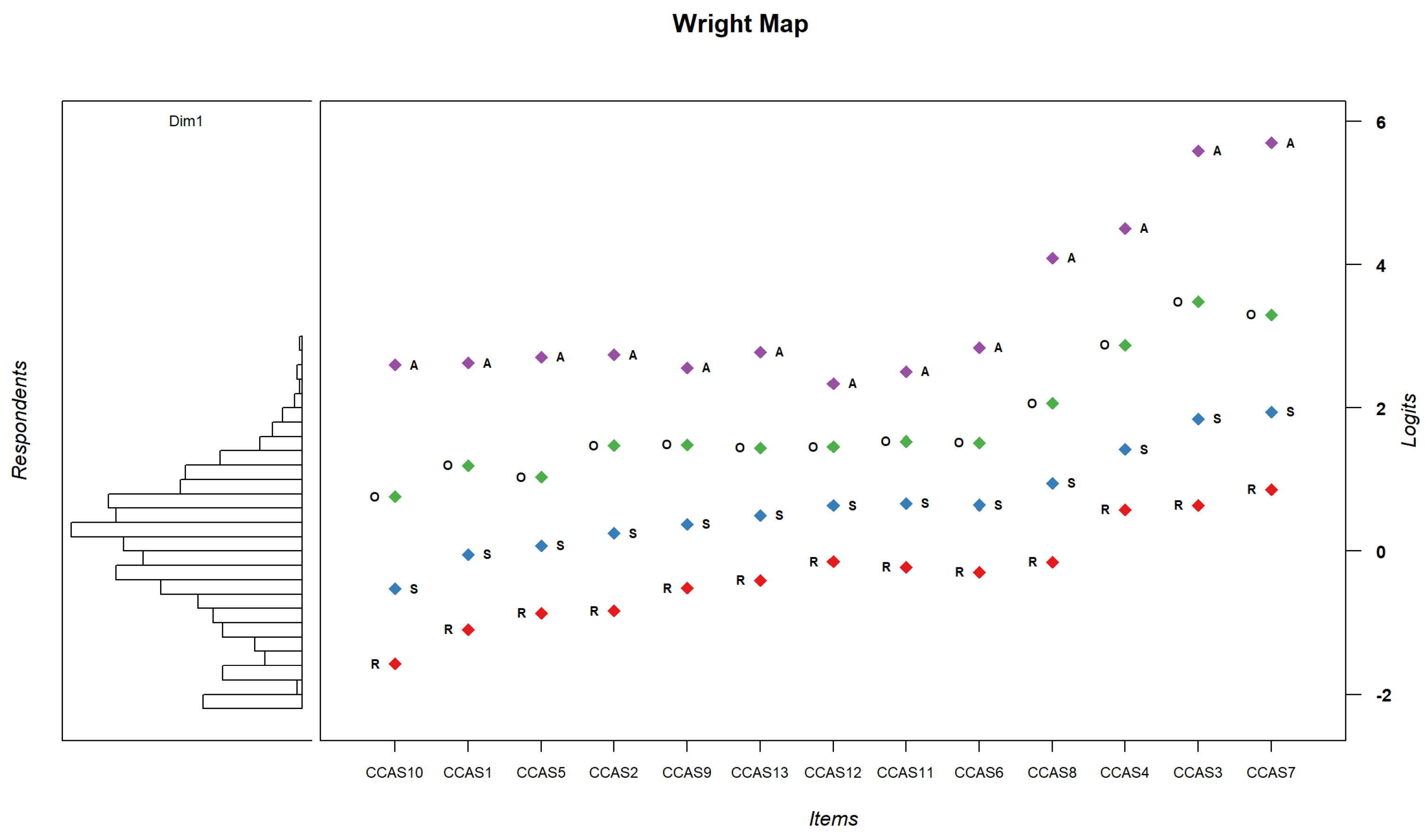

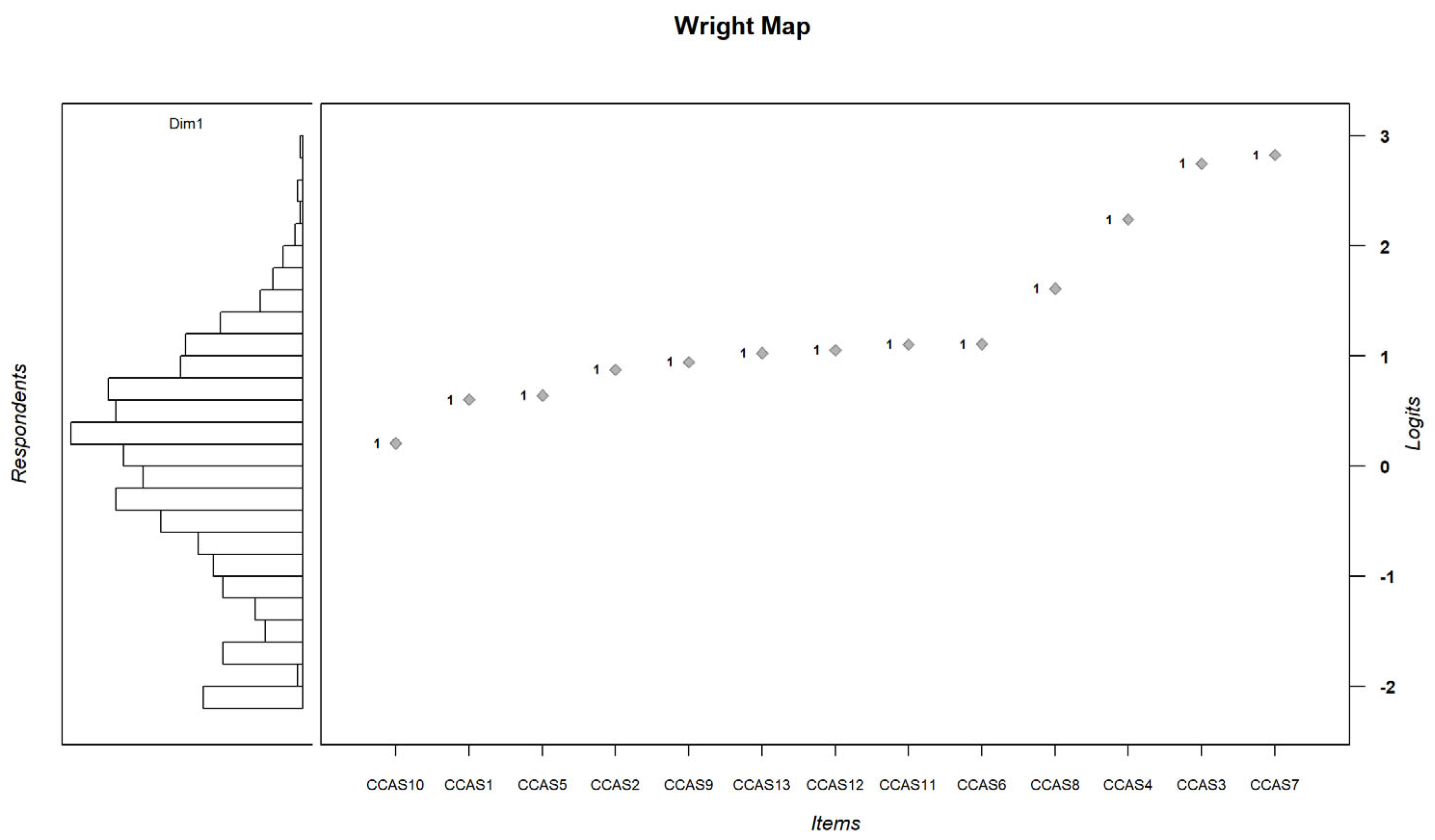

b1...4 values are standardized on a scale ranging, in our case, from -6 to 6. This choice was made in order to be able to graphically represent the most difficult modalities of the scale with values (greater than 3). A b value close to -6 reflects ease of endorsement of the item category in question. Conversely, an item category with a b value close to 6 is difficult to endorse.

One of the advantages of IRT is the independence of the estimated item parameters from the sample, and therefore the relative consistency of estimates across samples. Thus, a well-fitted model will always return the same item parameter estimates, regardless of the sample [

53]. As a result, the same analyses were carried out separately on the two datasets, with no major differences. Consequently, we will only present the results obtained on a single dataset from the work of Mouguiama-Daouda et al. [

16] (N=905). The full analyses carried out on both datasets are presented in the

Supplementary Materials.

4. Discussion

The present study explores alternative CCAS-13 factor structures that may better explain climate anxiety. We argued in favor of using the one-dimensional model rather than the 2- or 3-factors model of the CCAS-13. Our results are in line with what has been found in the literature about the goodness of fit of the unidimensional model [

16,

27]. Indeed, the 2- and 3-dimensional models present a problem of strong correlations between their dimensions. This means that the different factors measure almost the same thing. This misinterpretation might partly be due to the almost systematic choice of oblique rotations [

56].

Although rotation simplifies model selection and interpretation, it can also be misleading [

56]. Factors interpreted a posteriori are merely the result of the chosen rotation. This choice of rotation exacerbates what Van Schuur and Kiers [

20] call the "extra factor" phenomenon in exploratory factor analyses. These authors describe how, for a potentially bipolar concept, factor analyses misinterpret the (potentially quadratic) relationship between the latent dimension and its indicators, transforming what should be a unidimensional bipolar phenomenon into a multidimensional one whose factors are more or less independent. furthermore, the discussion around the eco-anxiety continuum, and the distinction between practical eco-anxiety and paralyzing eco-anxiety, raised questions about the multi-factor modeling of this construct. A recurring feature of the CCAS-13 data modelling we carried out without axis rotation is that there is always a dominant factor that explains most of the variance on its own. The bifactor model, which we also tested and which proposes a solution to circumvent the use of rotations, confirms that a general climate anxiety factor is the most relevant in the case of CCAS-13.

We have also demonstrated the usefulness of the IRT method in providing new perspectives on the conceptualization of eco-anxiety. It consolidates the tool, but also opens up prospects for its improvement. Indeed, the results of the item response model show that the positions of the items in terms of difficulty are similar in the analysis of the different data sets, thus indicating a good consistency of the eco-anxiety construct as described by CCAS-13. Consequently, it would be more interesting to validate tools based on a hierarchy of symptom severity.

In this regard, we note that items from the two dimensions defined by Clayton & Karazsia [

4] overlap on the eco-anxiety continuum. By interpreting the position of the items and analyzing their content in depth, we can begin to trace a continuum of the place eco-anxiety takes in a person's life. According to the results, it starts with: 1) having problems managing one's needs and interest in the sustainable; 2) questioning the way the environmental situation is handled cognitively and emotionally; 3) having social problems and a loss of meaning at work; and 4) falling into despair, accompanied by severe physical symptoms such as crying and nightmares.

However, one part of the continuum remains unexplored: that which concerns people with low scores. This limits the use of the CCAS among the general public, and raises questions about how this issue is represented.

Based on the floor effects observed on the distributions of the various items, states other than those described above are likely to be grouped in the non-anxious category. However, even if these people do not suffer from severe symptoms, they may nonetheless feel a certain amount of anxiety and stress relative to the perceived environmental crisis. In a recent qualitative study, Marczak et al. [

11] show that people who are strongly affected by the ecological crisis may not present any of the symptoms described in the CCAS-13 [

11]. If this questionnaire is to be adapted to a general population, we need to consider adjusting and supplementing it by including items that refer to less severe manifestations, and thus have a tool that could fit in with the idea of a continuum relating to eco-anxiety.