Submitted:

12 June 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

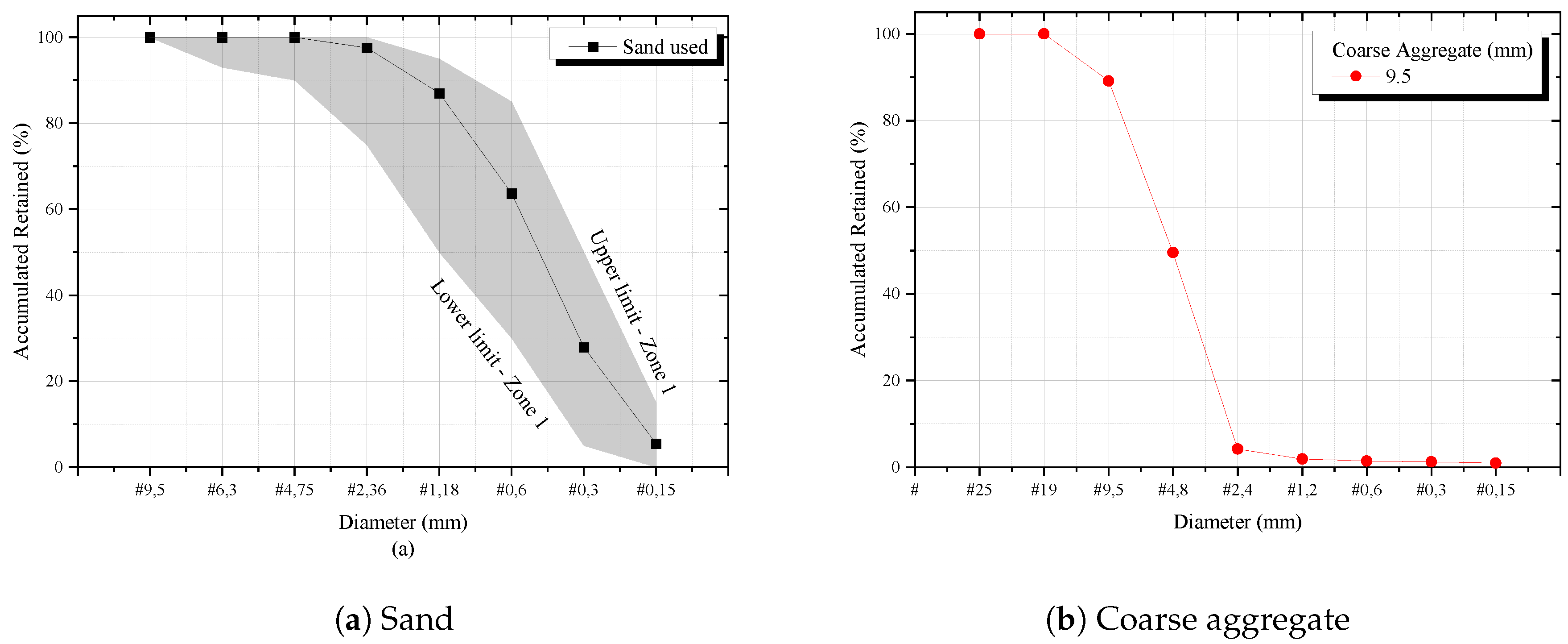

2.1. Materials and Mixtures

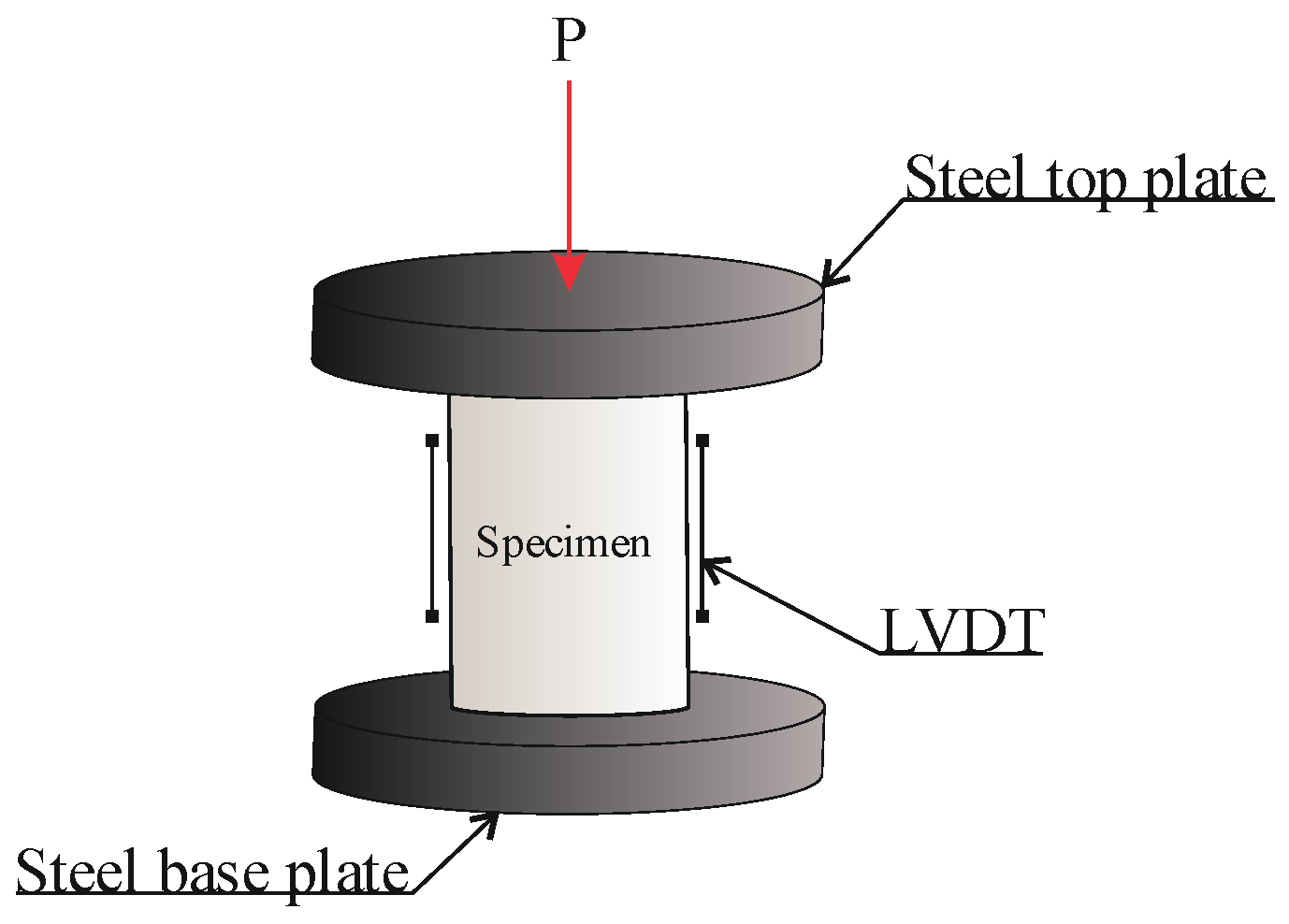

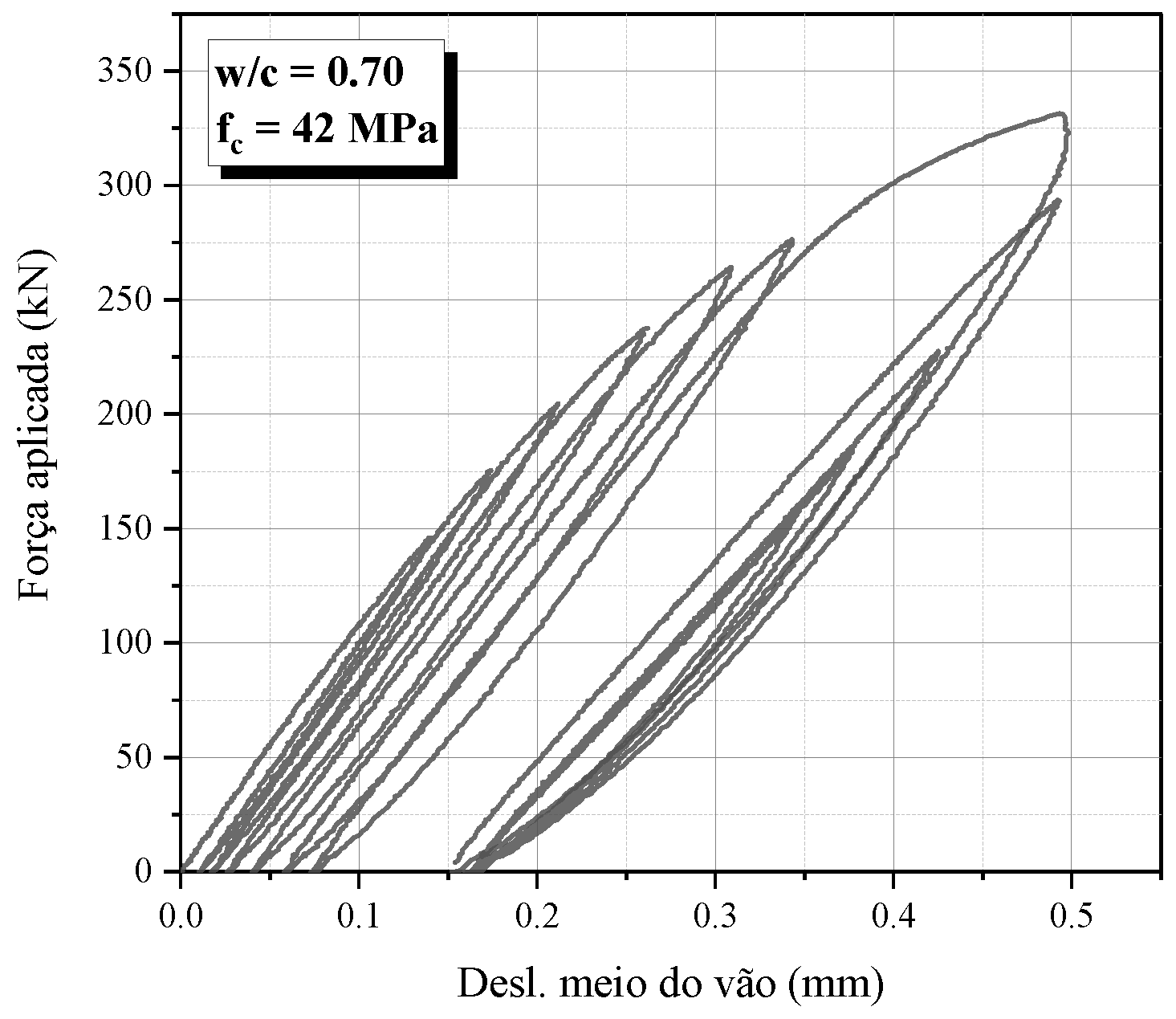

2.2. Cyclic Tests

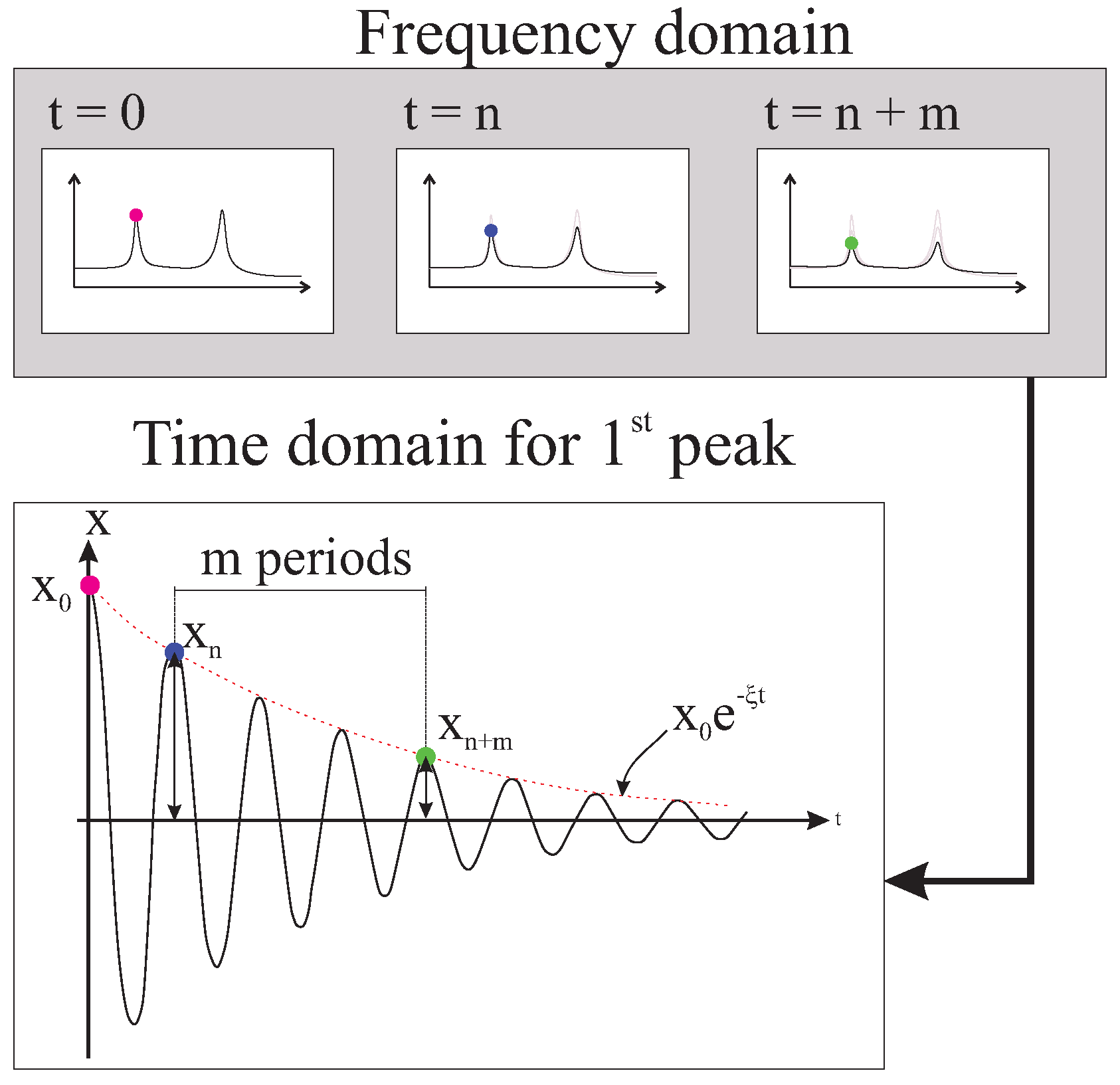

2.3. Acoustic Tests

3. Results

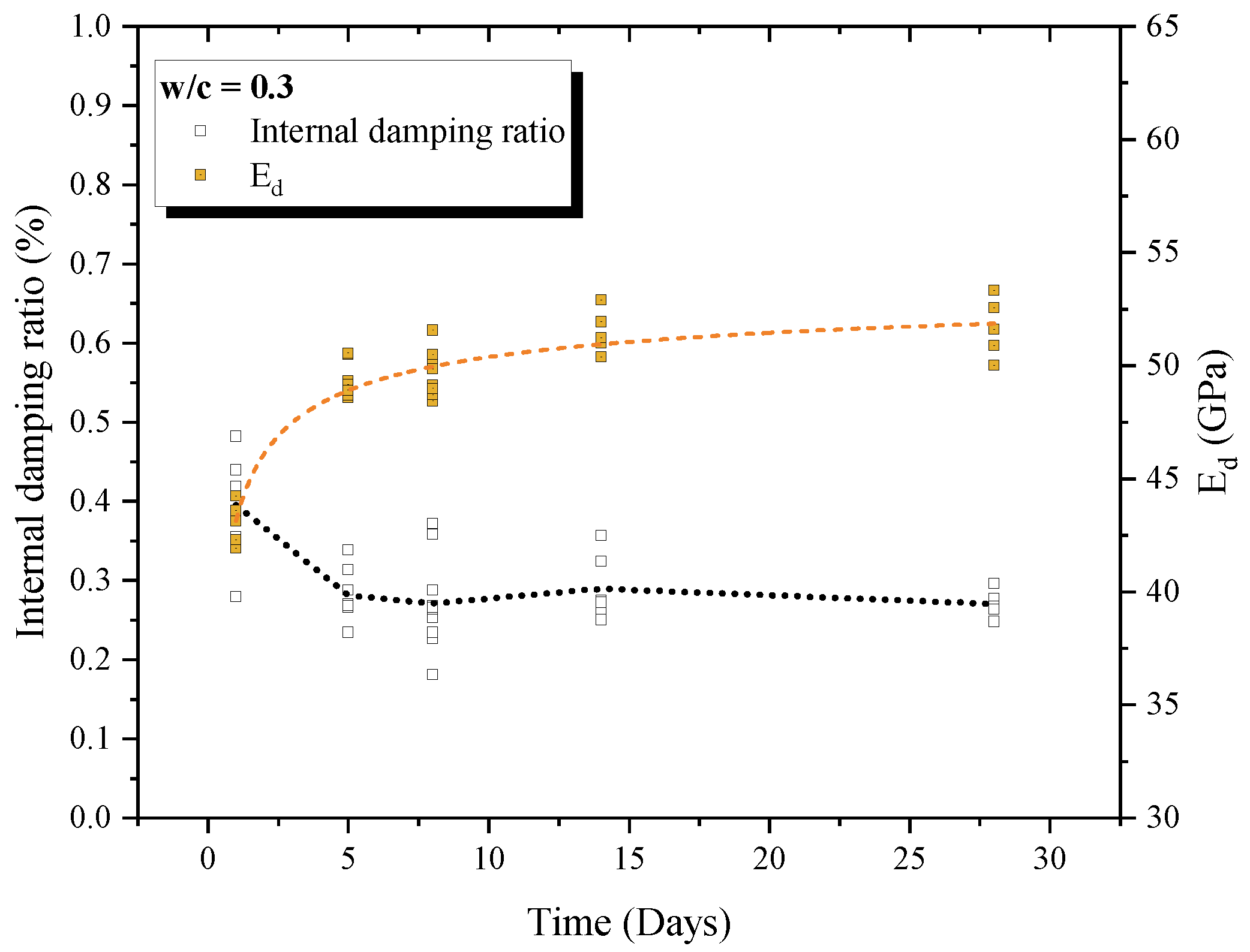

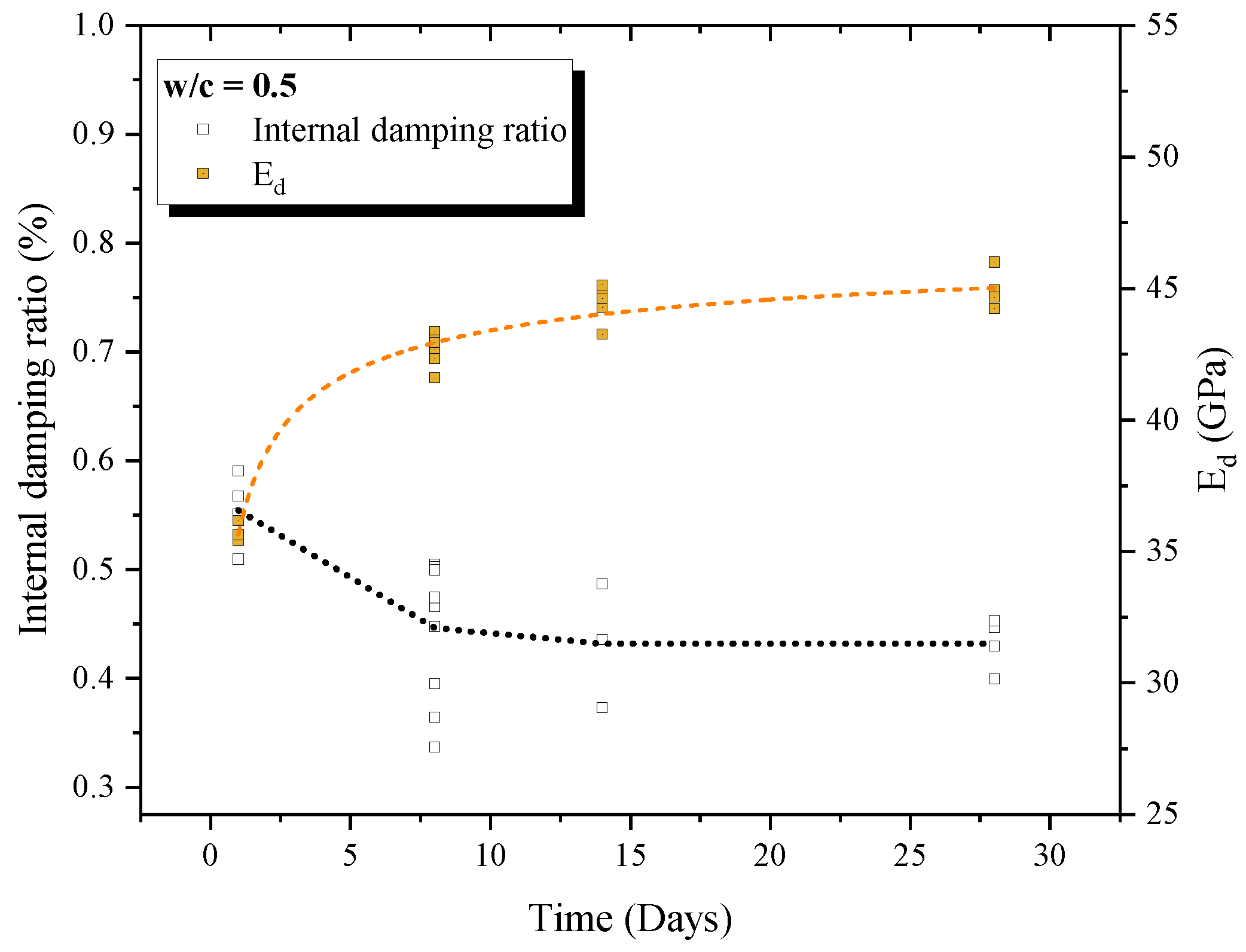

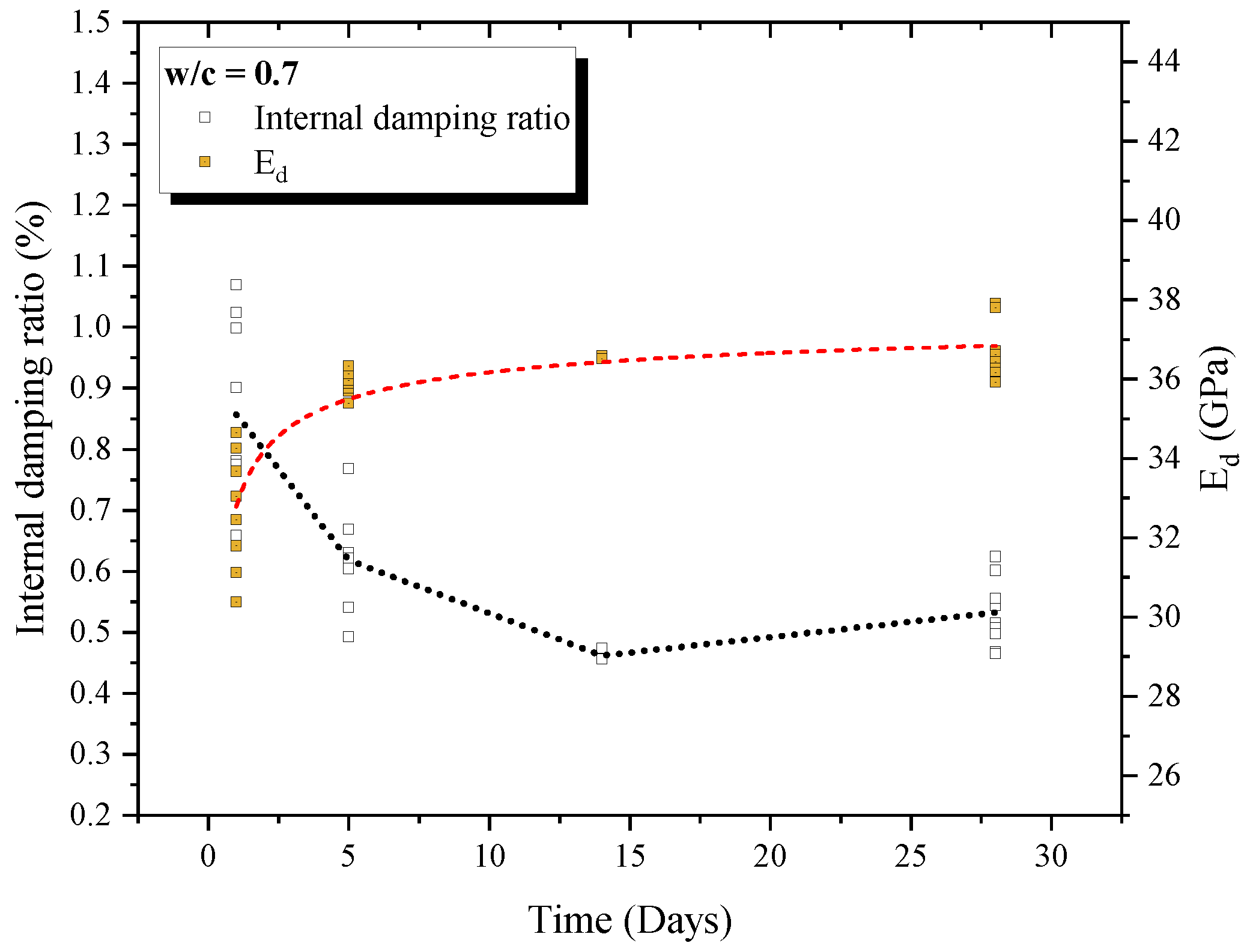

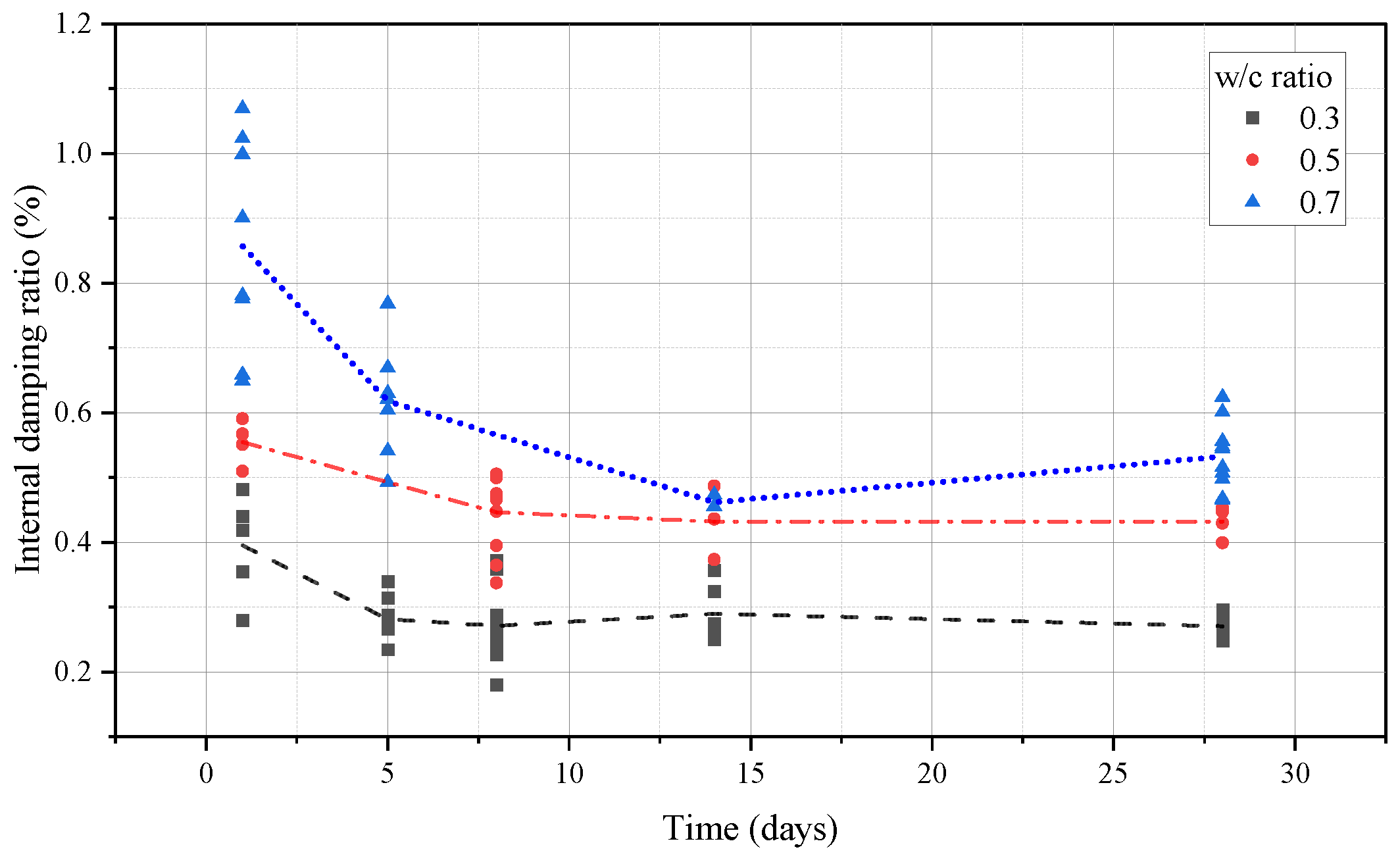

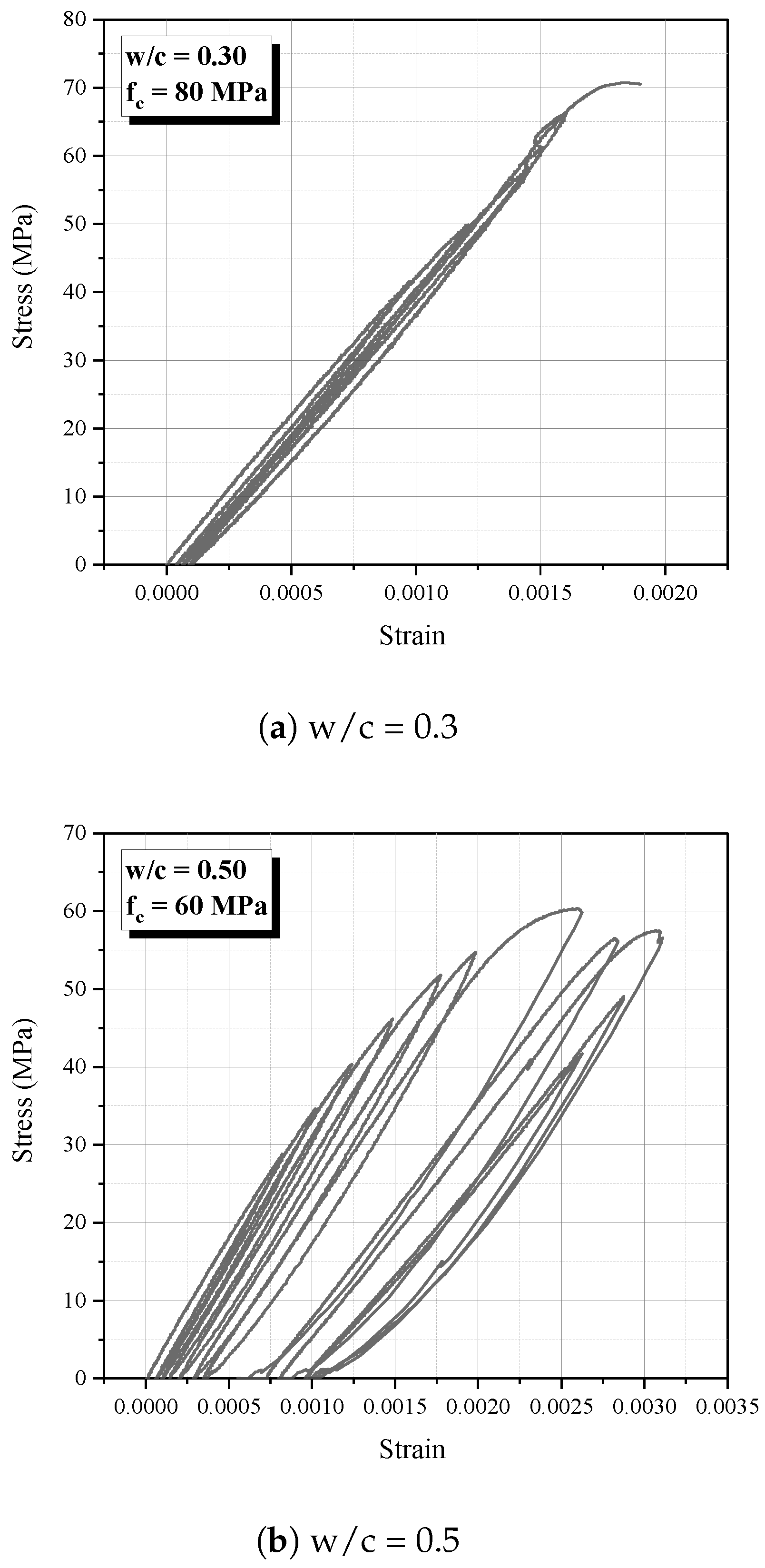

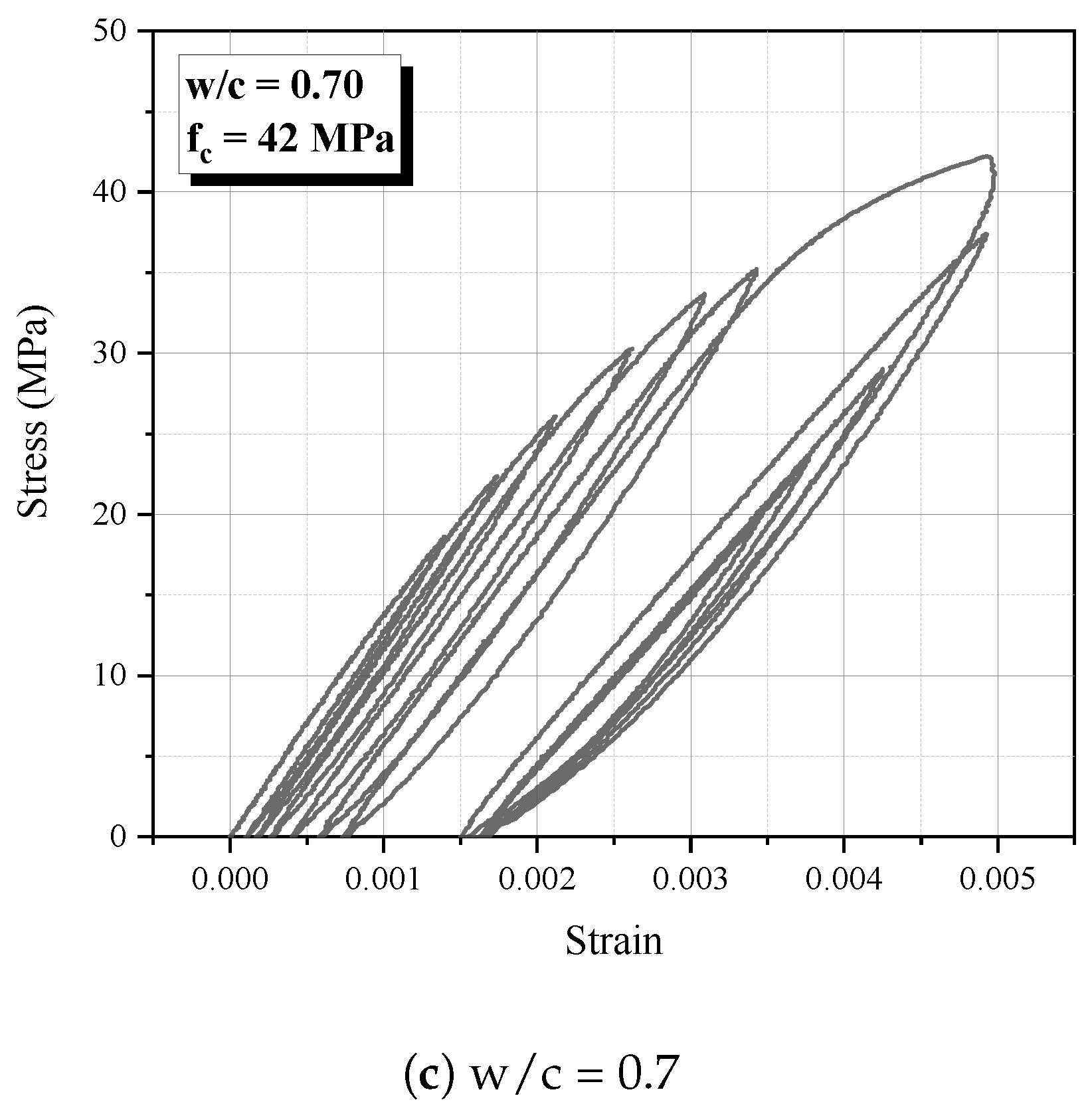

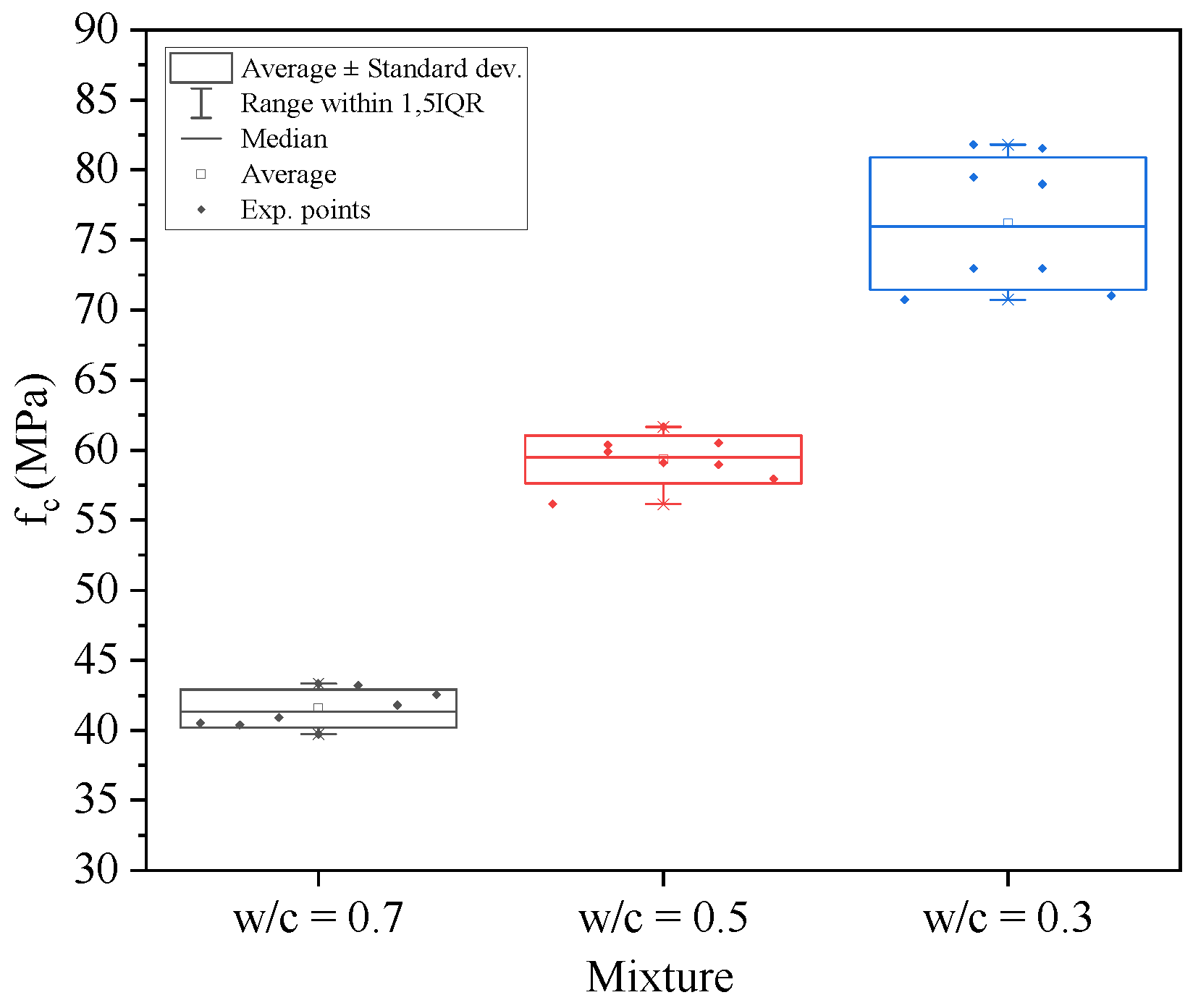

3.1. Undamaged Samples

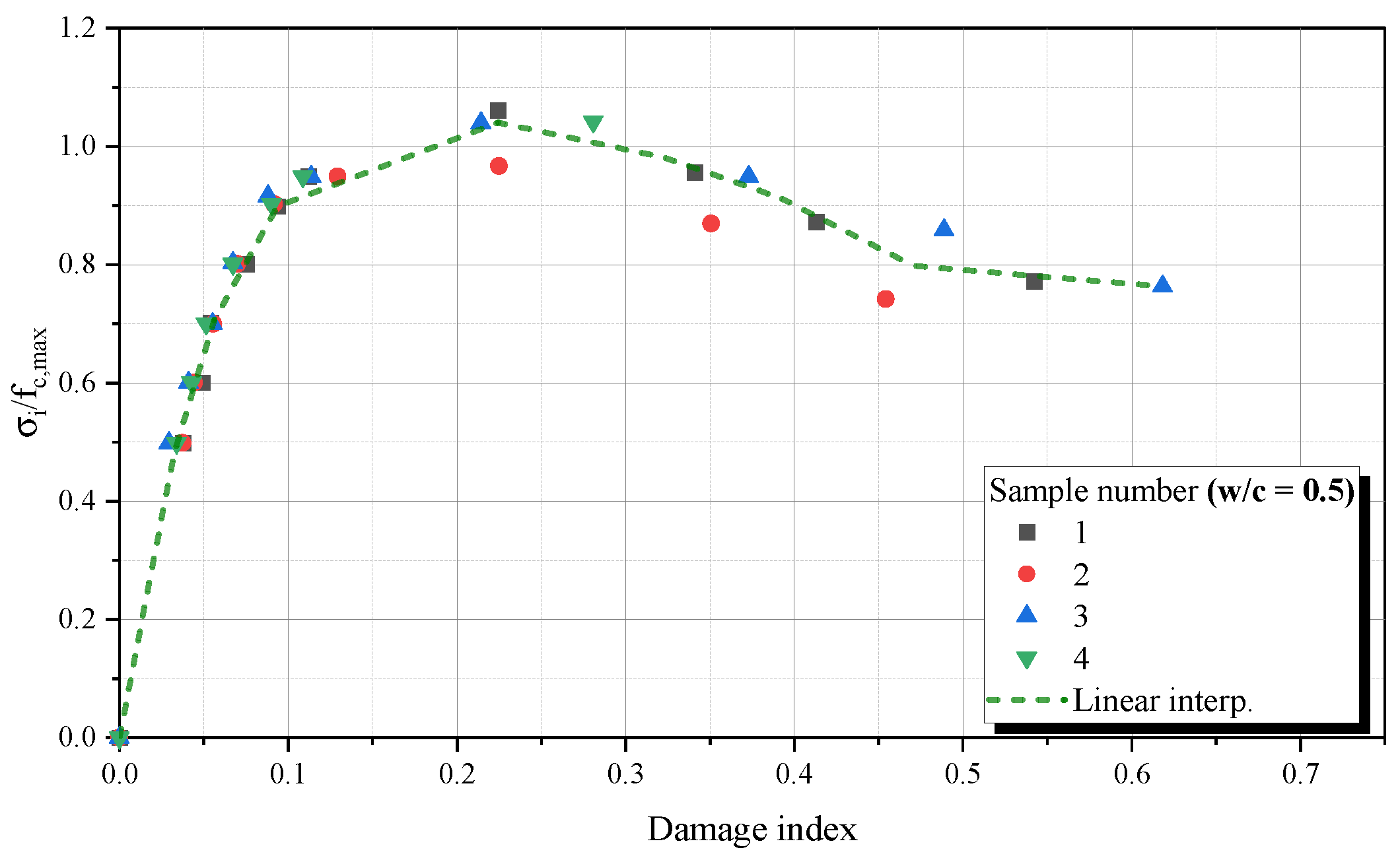

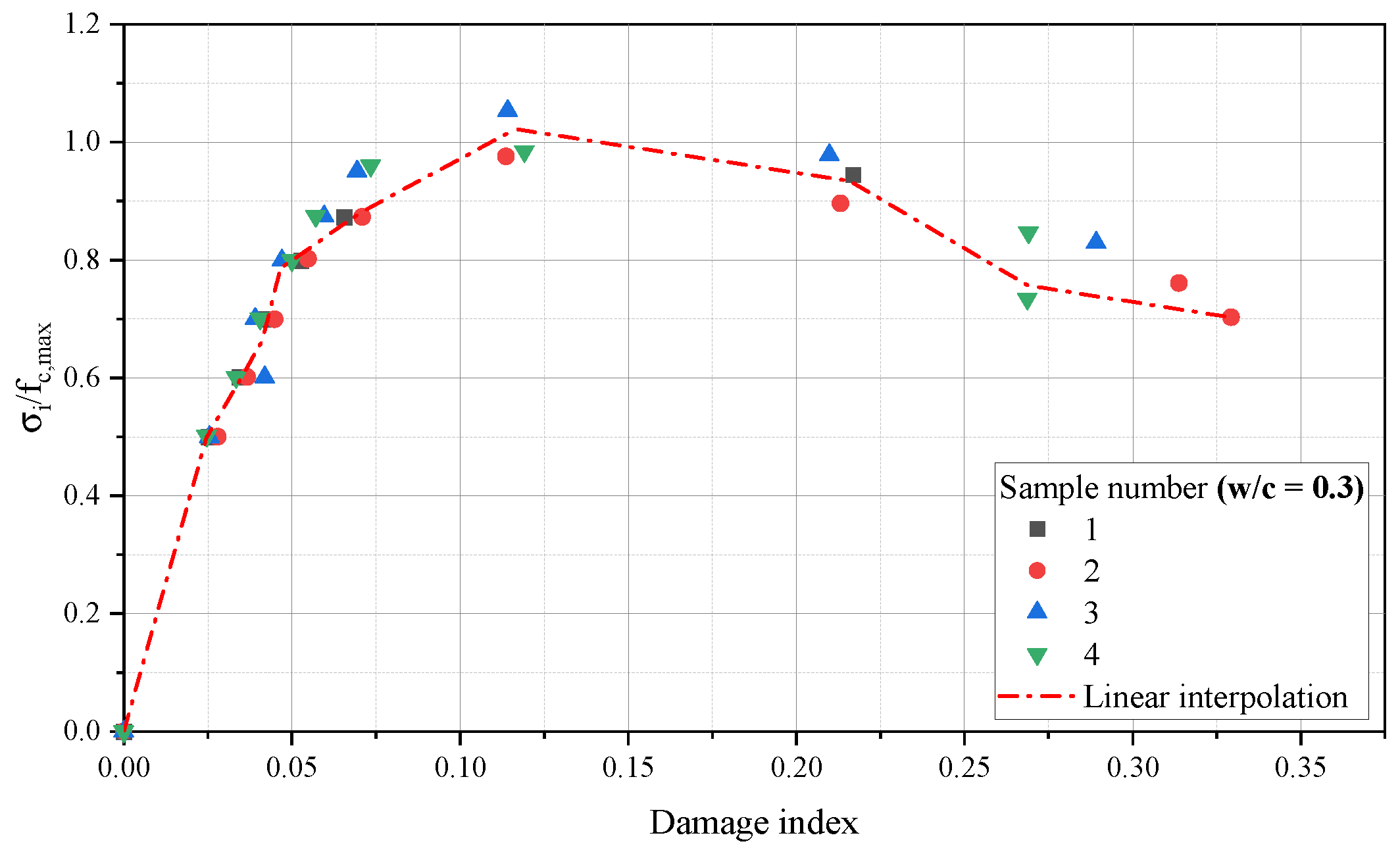

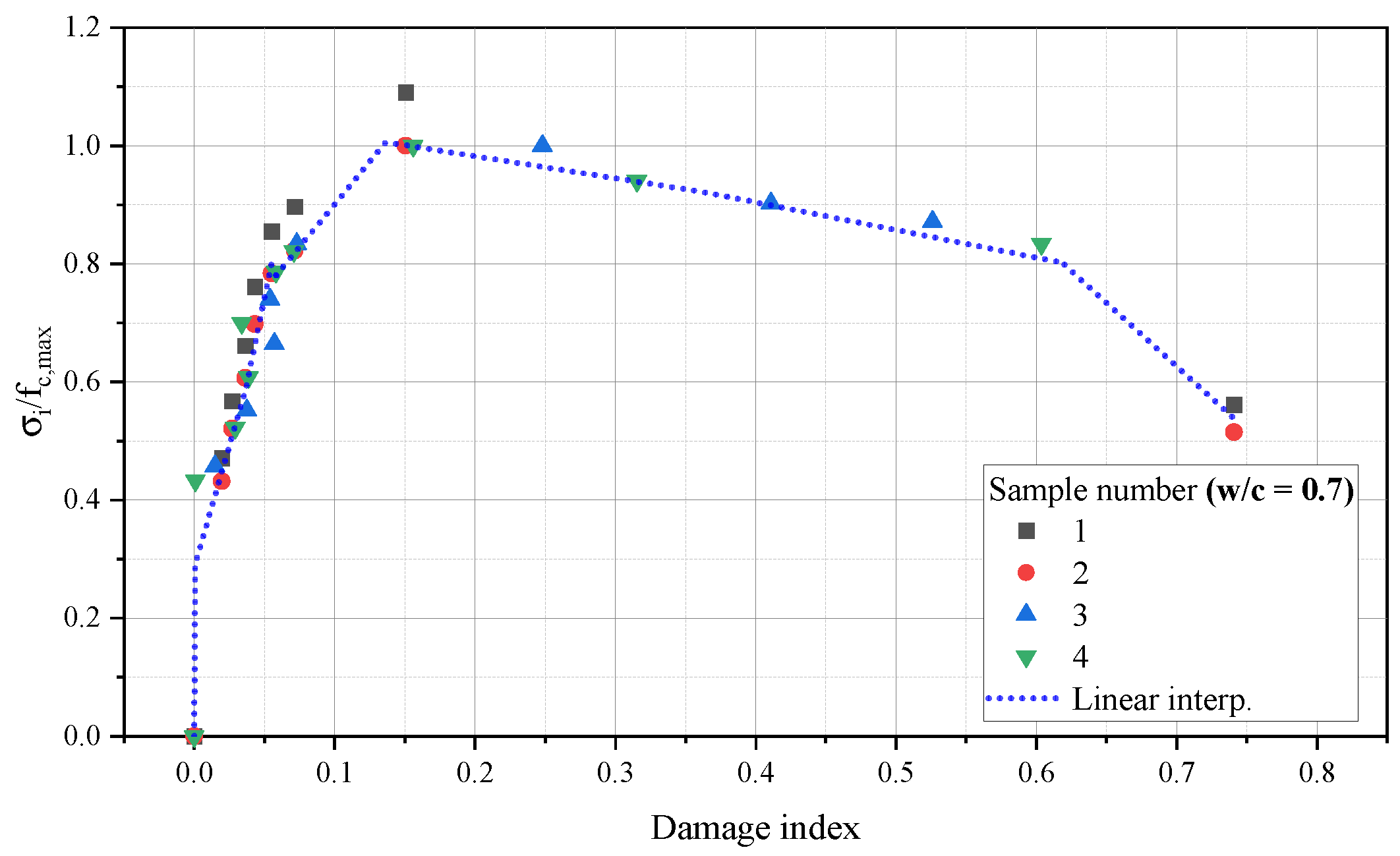

3.2. Damaged Samples

4. Conclusions

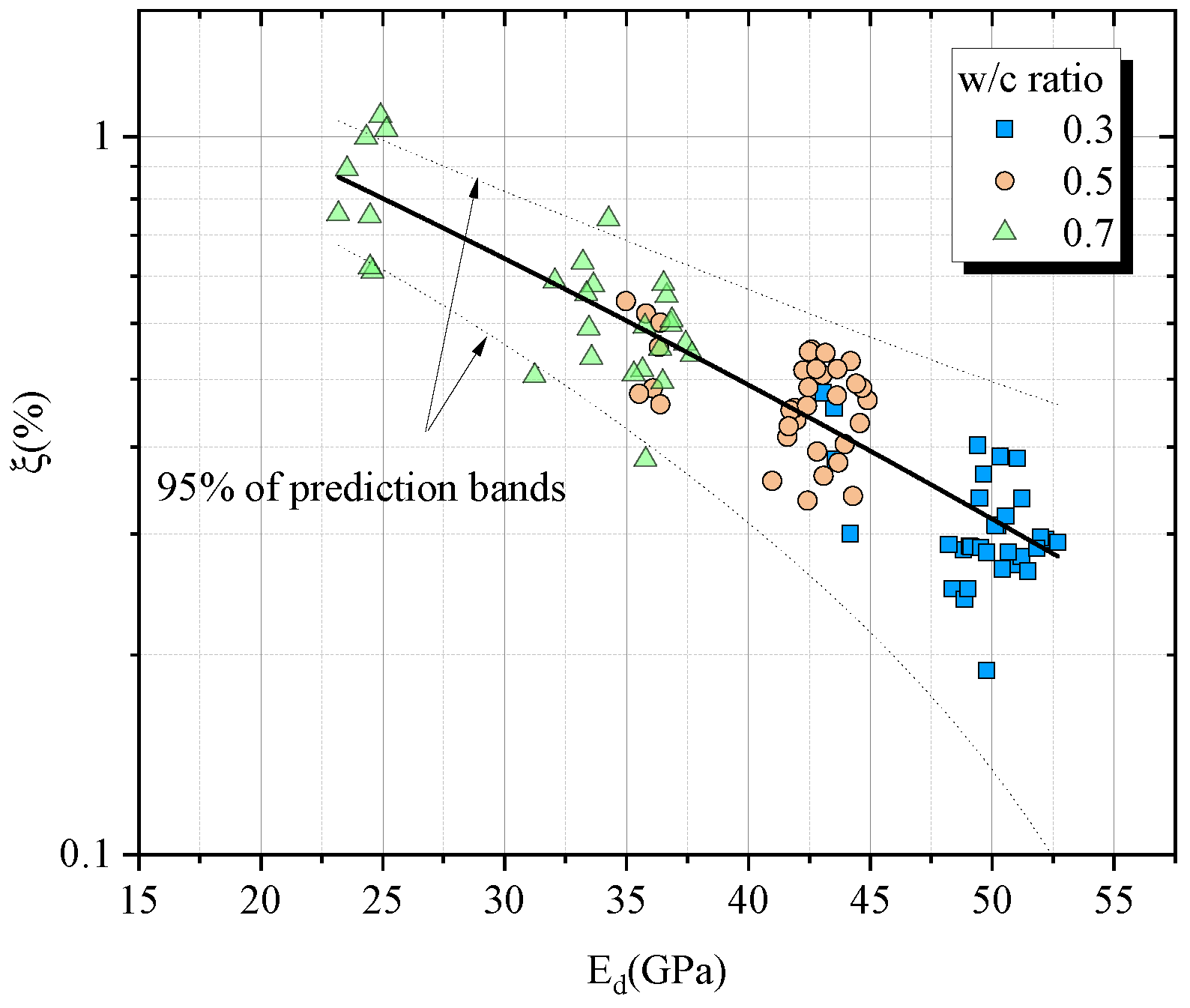

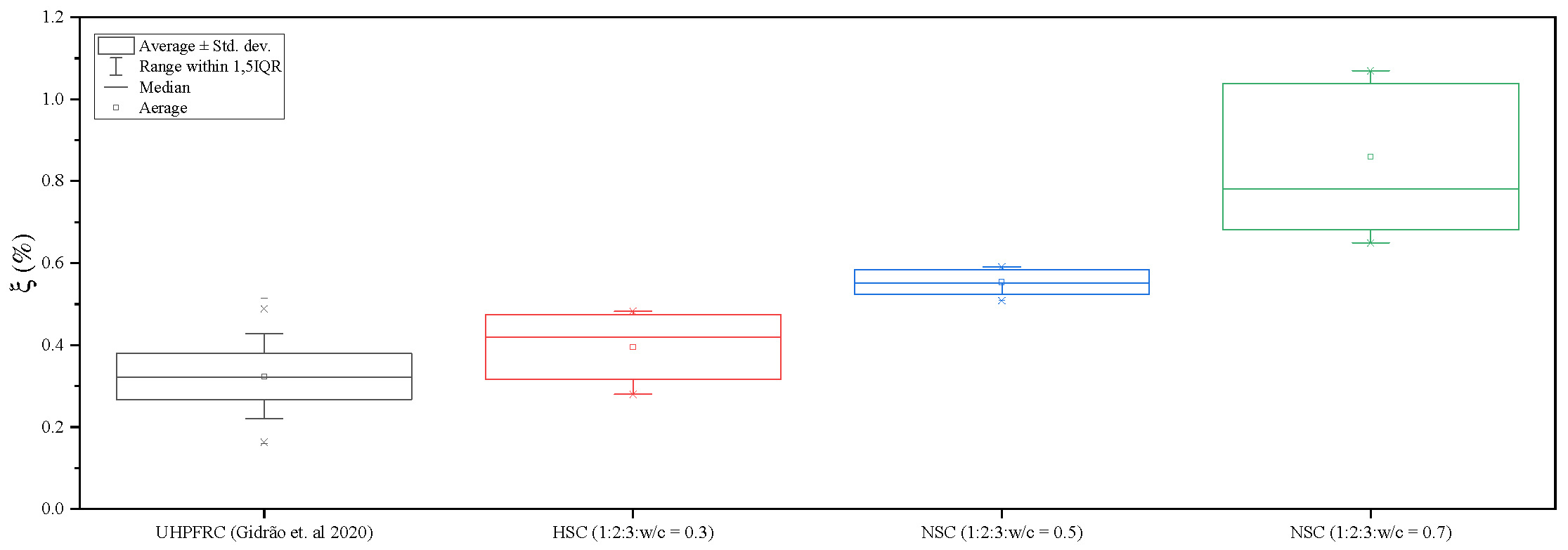

- Internal damping ratio was correlated with parameters as w/c ratio, maturity and dynamic elastic modulus. The pore closure over maturity decrease the viscous internal damping. Furthermore, C-S-H hydration reactions improves the material density and decreases the internal dissipation, decreasing the acoustic wave dissipation.

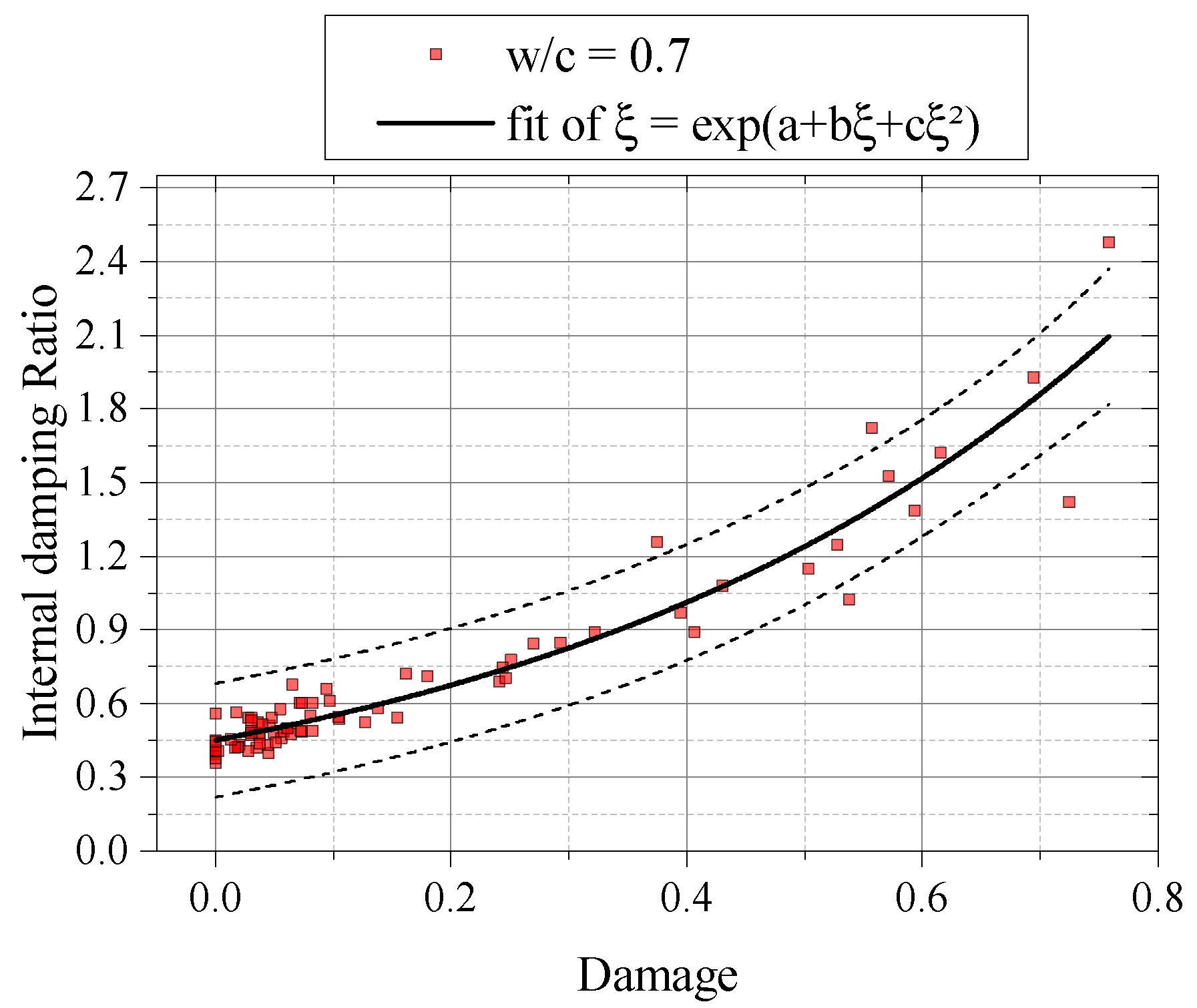

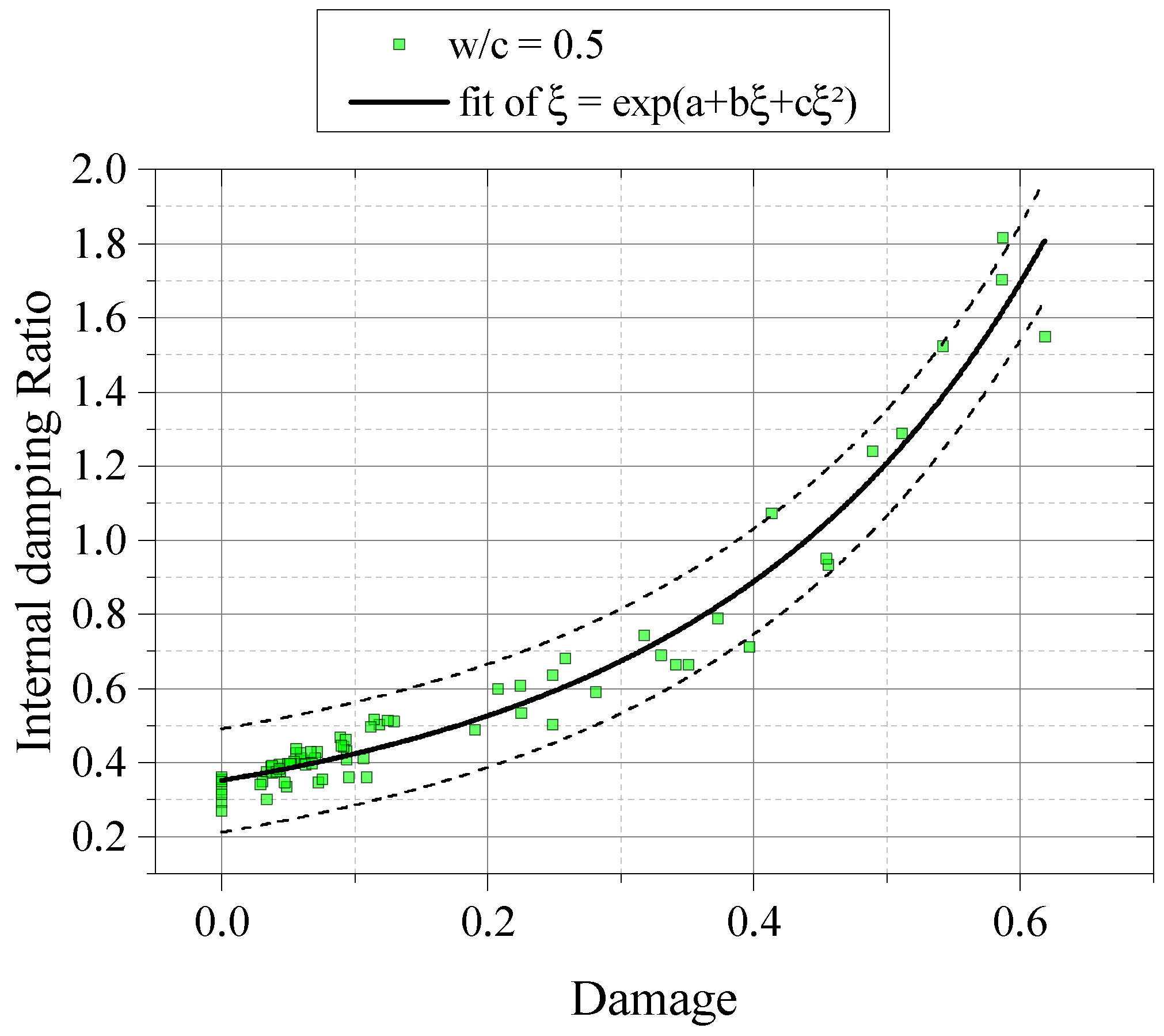

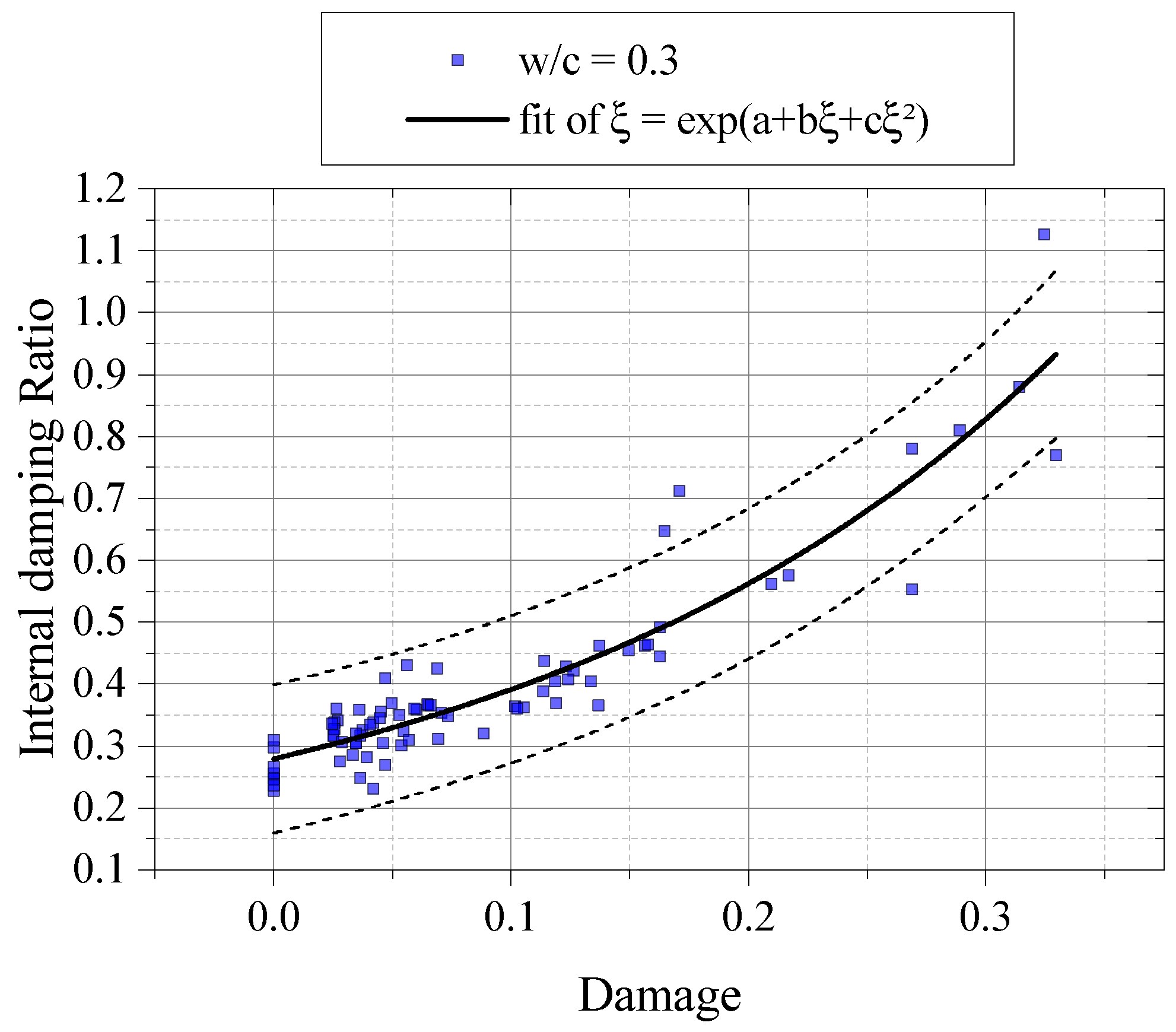

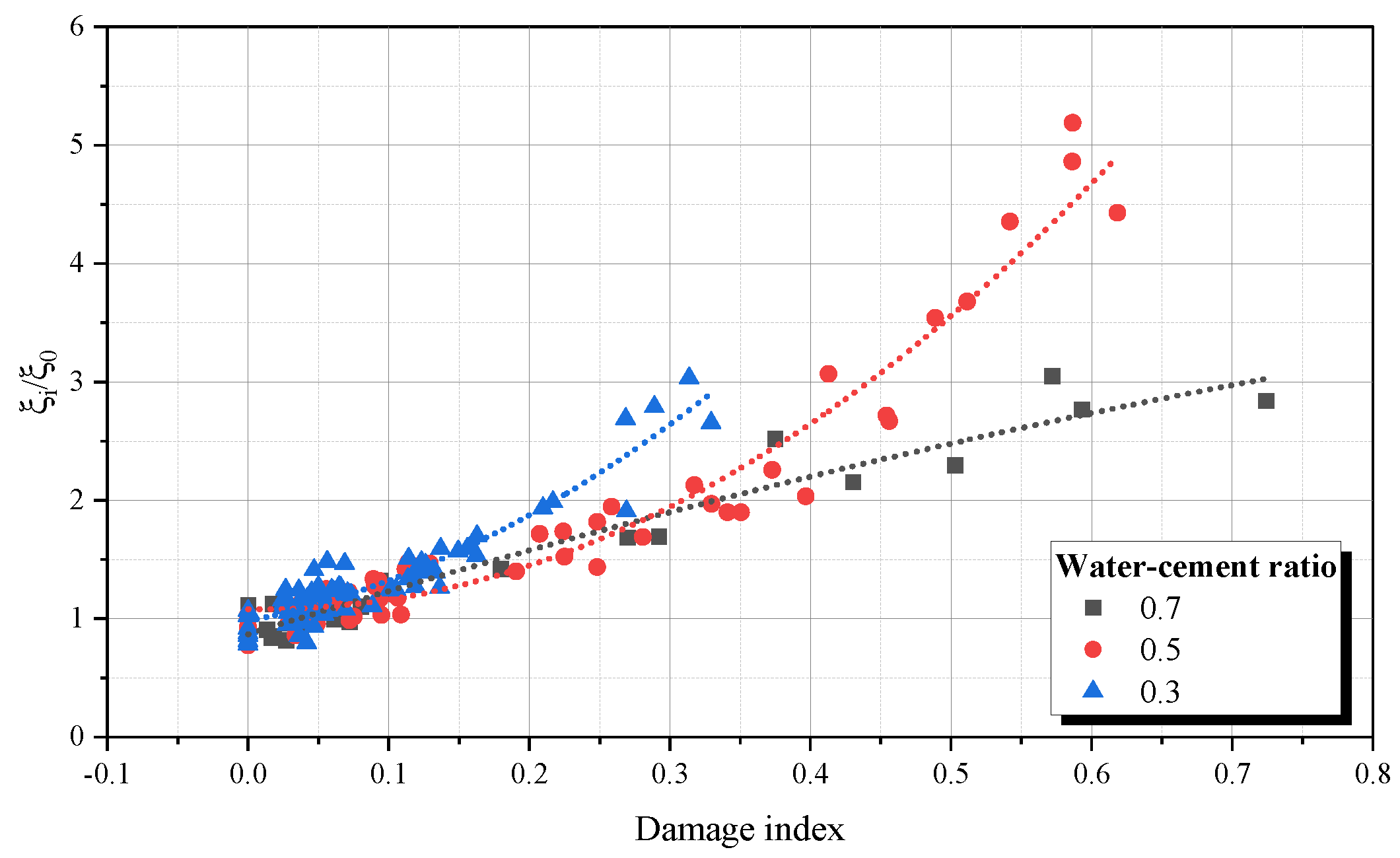

- An investigation of how the damage influences the damping ratio was accomplished. Our results appointed that a growth of damage generates a increase of Coulomb damping parcel, and its is accompanied of internal damping ratio improvement. It was determine the scale of this phenomenon, regarding mixtures of NSC and HSC.

- Microstructural conditions, like initial porosity, early micro-cracks and transition zone showed influential to response of damage and internal damping ratio evolution, once samples with higher water cement ratios showed more susceptible to increase of damage accompanied by high values of internal damping ratio and dissipation of acoustic wave.

- Internal damping ratio is a parameter sensitive to Microstructural modifications and its very linked to damage progression.

- There are few studies allowing the quantification and comprehension of internal damping ratio under damage cyclic loading and this approach will lead to improve the understanding of concrete under dynamical excitation, mainly impact situations.

References

- Paultre, P. Dynamics of Structures; ISTE ltd/Wiley: London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, H.; Ammann, W.J.; Eisenmann, J.; Floegl, I.; Hirsch, G.H.; Klein, G.K.; Lande, G.J.; Mahrenholtz, O.; Natke, H.G.; Nussbaumer, H.; et al. Vibration Problems in Structures - Practical Guidelines 1995.

- Boccaccini, D.N.; Romagnoli, M.; Kamseu, E.; Veronesi, P.; Leonelli, C.; Pellacani, G.C. Determination of thermal shock resistance in refractory materials by ultrasonic pulse velocity measurement. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 2007, 27, 1859–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.H.; Fortes, G.M.; Schickle, B.; Tonnesen, T.; Musolino, B.; Maciel, C.D.; Rodrigues, J.A. Correlation between changes in mechanical strength and damping of a high alumina refractory castable progressively damaged by thermal shock. Ceramica 2010, 56, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curadelli, R.O.; Riera, J.D.; Ambrosini, D.; Amani, M.G. Damage detection by means of structural damping identification. Engineering Structures 2008, 30, 3497–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angela Salzmann. DAMPING CHARACTERISTICS OF REINFORCED AND PRESTRESSED NORMAL- AND HIGH-STRENGTH CONCRETE BEAMS. Doctor of philosophy, GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY - GOLD COAST CAMPUS, 2002.

- Angela Salzmann, S. Fragomeni, Y.C.L. The Damping Analysis of Experimental Concrete Beams under Free-Vibration. Advances in Structural Engineering 2003, 6, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.W. The effect of stress, frequency, curing, mix and age upon the damping of concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research 1980, 32, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu, C.; Rhazi, J.E.; Labossiere, P. Impact resonance method for fatigue damage detection in reinforced concrete beams with carbon fibre reinforced polymer. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 2005, 32, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndambi, J.M.; Vantomme, J.; Harri, K. Damage assessment in reinforced concrete beams using eigenfrequencies and mode shape derivatives. Engineering Structures 2002, 24, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawa, N.; Graft-Johnson, J. Effect of Mix Proportion , Water-Cement Ratio , Age and Curing Conditions on the Dynamic Modulus of Elasticity of Concrete. Build. Sci. 1969, 3, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, R. Damping Mechanisms in Cementitious Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of a Conference on Dynamic waves in civil engineering, Swansea, 1970; pp. 521–542. [Google Scholar]

- Eiras. ; Popovics.; Borrachero.; Monzó.; Payá. The effects of moisture and micro-strucutral modification in drying mortars on vibration-based NDT methods. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 94, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidrão, G.d.M.S.; Krahl, P.A.; Carrazedo, R. Internal damping ratio of Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforcement Concrete (UHPFRC) considering the effect of fiber content and damage evolution. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, N.; Rigby, G. Dynamic properties of hardened paste , mortar and concrete. Matériaux et constructions, 1971; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, R.N. DYNAMIC POISSON’S RATIO OF PORTLAND CEMENT PASTE, MORTAR AND CONCRETE. Cement and Concrete Research, 1971; Vol.I, pp. 559–583. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Lu, D.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z. Damping Property of Cement Mortar Incorporating Damping Aggregate Yaogang. materials, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Effect of the characteristics of lightweight aggregates presaturated polymer emulsion on the mechanical and damping properties of concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 253, 119154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Long, G.; Fu, Q.; Wang, X.; Ma, K.; Xie, Y. Effects of freeze and cyclic flexural load on mechanical evolution of filling layer self-compacting concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 200, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Shi, S.; Jia, K.; Hu, S. Mechanical and dynamic properties of high strength concrete modified with lightweight aggregates presaturated polymer emulsion. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 93, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. ASTM C150-04: Standard Specification for Portland Cement. American Society for Testing and Materials. 2011, 04, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABNT, A.B.d.N.T. ABNT NBR 7211 - Agregados para concreto - Especificação. 2009.

- ASTM C215-02, A.S.f.T.M. Standard Test Method for Fundamental Transverse, Longitudinal, and Torsional Resonant Frequencies of Concrete Specimens. 2003, pp. 1–7.

- ASTM E1876-01, A.S.f.T.M. Standard Test Method for Dynamic Young ’ s Modulus, Shear Modulus, and Poisson ’ s Ratio by Impulse Excitation of Vibration, 2001.

- Haach, V.G.; Carrazedo, R.; Oliveira, L.M.; Corrêa, M.R. Application of acoustic tests to mechanical characterization of masonry mortars. NDT & E International 2013, 59, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, G. Equations for Computing Elastic Constants from Flexural and Torsional Resonant Frequencies of Vibration of Prisms and Cylinders. Proceedings of the American Society for Testing Materials 1945, 45, 846–866. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.H.A.; Otani, L.B.; De Anchieta Rodrigues, J.; Traon, N.; Tonnesen, T.; Telle, R. The influence of nonlinear elasticity on the accuracy of thermal shock damage evaluation by the impulse excitation technique. InterCeram: International Ceramic Review, 2011; pp. 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira. ; Musolino.; Maciel.; Rodrigues. Algorithm to determine the damping of ceramic materials by the impulse excitation technique ceramic materials by the impulse excitation technique. Ceramica 2012, 58. [Google Scholar]

| ID | w/c | Cement | Sand | Aggregate | (mm) | SP. |

| 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9.5 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9.5 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 9.5 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).