Submitted:

03 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

A. Human Success Factors (HSFs) and Human Security Vulnerabilities (HSFs) in Secure Software Development

B. Aims of the Study

C. Significance of the Study

D. Organization of the Paper

II. Background and Related Work

A. Motivations Behind the Study

B. Software Security

C. People’s Maturity Toward Secure Software Development

1). Dimensions of People Maturity

- i.

- Technical Proficiency and Skill Development: The identification and confirmation that the members of the team have the required competencies is perhaps the most essential element of people's maturity. Enlisting a professional training and education program on the best practices, instruments, and techniques of contemporary securities is also crucial.

- ii.

- Experience: The professional members of the team need to be able to use their expertise and analyze the probable problem related to security and then implement the principles learned most appropriately.

- iii.

- Process Adherence and Standardization: Excellent teams operate with standard methodologies and guidelines that contain security since the beginning of the development stage, for instance, SSDLC models.

- iv.

- Compliance: Thus, following the best practices of the industry and the legally compliant acts guarantees that the security will be the best and most updated.

- v.

- Communication and Collaboration and Interdisciplinary Coordination: Communication is essential because it helps the developers, security specialists, and other related stakeholders to ensure that the security requirements are understood and reflected in the development process.

- vi.

- Feedback Mechanisms: The development of sound feedback mechanisms enables the development team to quickly note or report on security issues as the project progresses.

- vii.

- Proactive Security Culture and Security Awareness: It is compelling to make security a part of a team culture where everyone understands the organization’s threats and actively seeks to prevent them.

- viii.

- Responsibility and Accountability: This gives them ownership of security tasks; in the process, individuals feel responsible for the overall security tasks.

- ix.

- Problem-Solving and Analytical Skills: Most well-established teams employ very formal and rational strategies like threat modeling and risk analysis to analyze the weaknesses in security systems.

- x.

- Decision Frameworks: By applying decision-support tools like Fuzzy-AHP, the teams can calculate security measures considering various factors and the fuzziness of the decision-making environment.

2). Benefits of People's Maturity Toward Secure Software Development

- i.

- Enhanced Security Posture: Originally, higher people's maturity meant a better ability to understand and eliminate security threats, thus improving security maturity.

- ii.

- Reduced Risk: Consequently, the secure maturity level of the formative team means the ability to independently assess the threats and threats handling, which leads to a decrease in the number of and the impacts due to security breaches.

- iii.

- Improved Compliance: Compliance with security standards and meeting regulatory standards increases, meaning the software is legal and complies with industry standards.

- iv.

- Increased Efficiency: That way, the practices are standardized, and communication is efficient in establishing means of providing security without overloading developers for a long time.

- v.

- Continuous Improvement: By practicing open acknowledgment that is not confined to learning through experience but goes further to embrace proactivity, the teams remain informed on the current security trends and hence make constant enhancements to security.

3). Achieving People's Maturity Toward Secure Software Development

- i.

- Invest in Training: Develop and implement continuing formal training sessions and seminars about new means and protection methods.

- ii.

- Implement Standard Processes: First, implement and apply the set of requirements for security across the entire project, not just the separate ones.

- iii.

- Foster a Security Culture: Encourage the organization's personnel, teams, and departments to embrace security matters.

- iv.

- Facilitate Communication: Promoting the free flow of information and patronizing the establishment of rapport between all the participating stakeholders, especially in designing the software.

- v.

- Utilize Decision-Making Tools: Utilize well-formalized decision-making approaches like Fuzzy-AHP in security-related decision-making.

D. Related Work

1). Human Factors in Software Security

2). Secure Software Development Lifecycle

3). Maturity Models

4). Decision-Making Frameworks

5). Roles of Human Factors and Security in Integration

6). Gaps and Opportunities

7). Conclusion

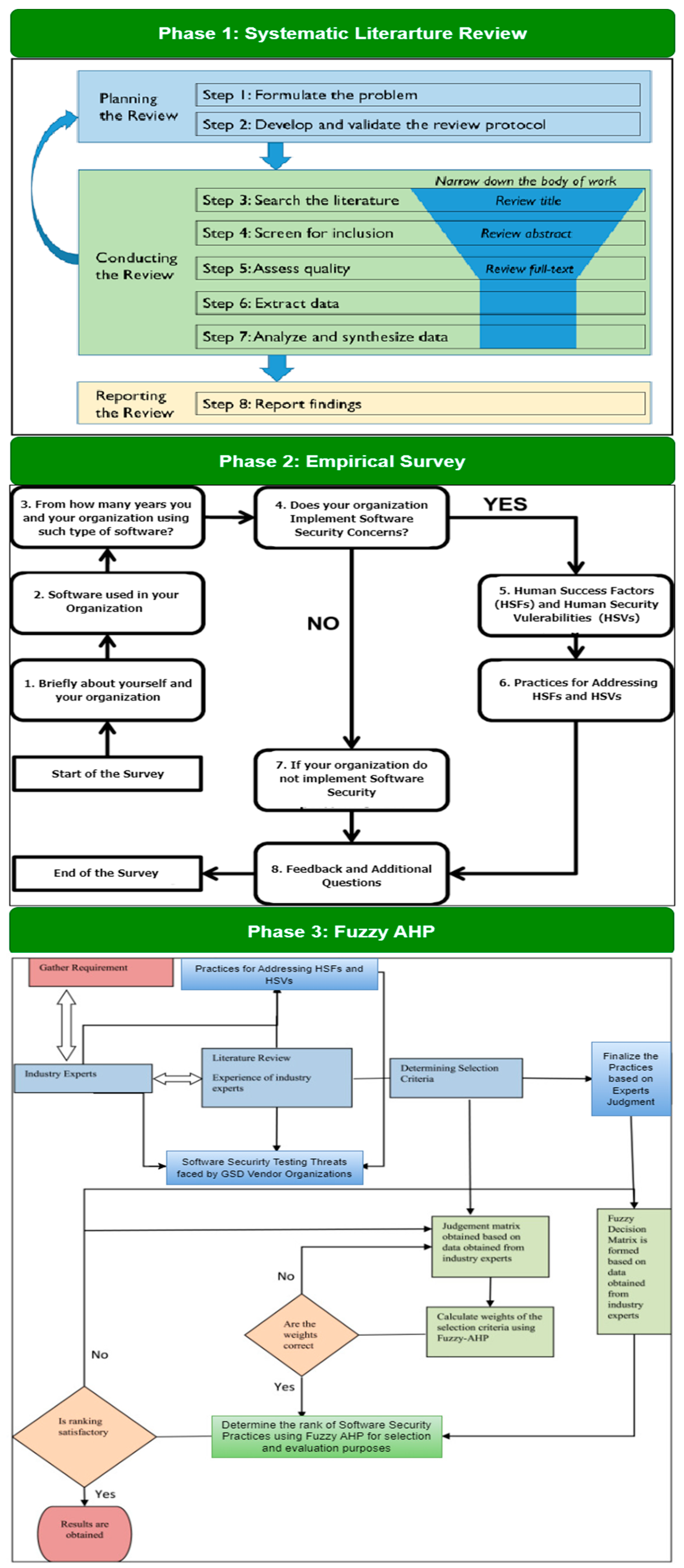

III. Research Methodology

A. Phase 1: Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

1). Step 1: Identification of Research Questions

- RQ1: What are the human factors (success factors and security vulnerabilities), as reported in the literature and real-world industry, that influence secure software development projects?

- RQ2: Are there any differences between the success factors and security vulnerabilities identified in the literature and real-world industry?

- RQ3: What are the best practices, as reported in the literature and real-world industry, that address the human factors (security vulnerabilities) in secure software development projects?

- RQ4: How can a decision-making framework be developed to identify the weights of human success factors and security vulnerability practices and evaluate the effectiveness of secure software development projects?

2). STEP 2: Reviewing or Drafting Review Protocol

- Search Strategy: Specified keywords, databases, and search engines will be used.

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Selection of literature.

- Data Extraction: The type of data that can be mined from each study.

- Quality Assessment: The quality of the studies included in the review is also considered.

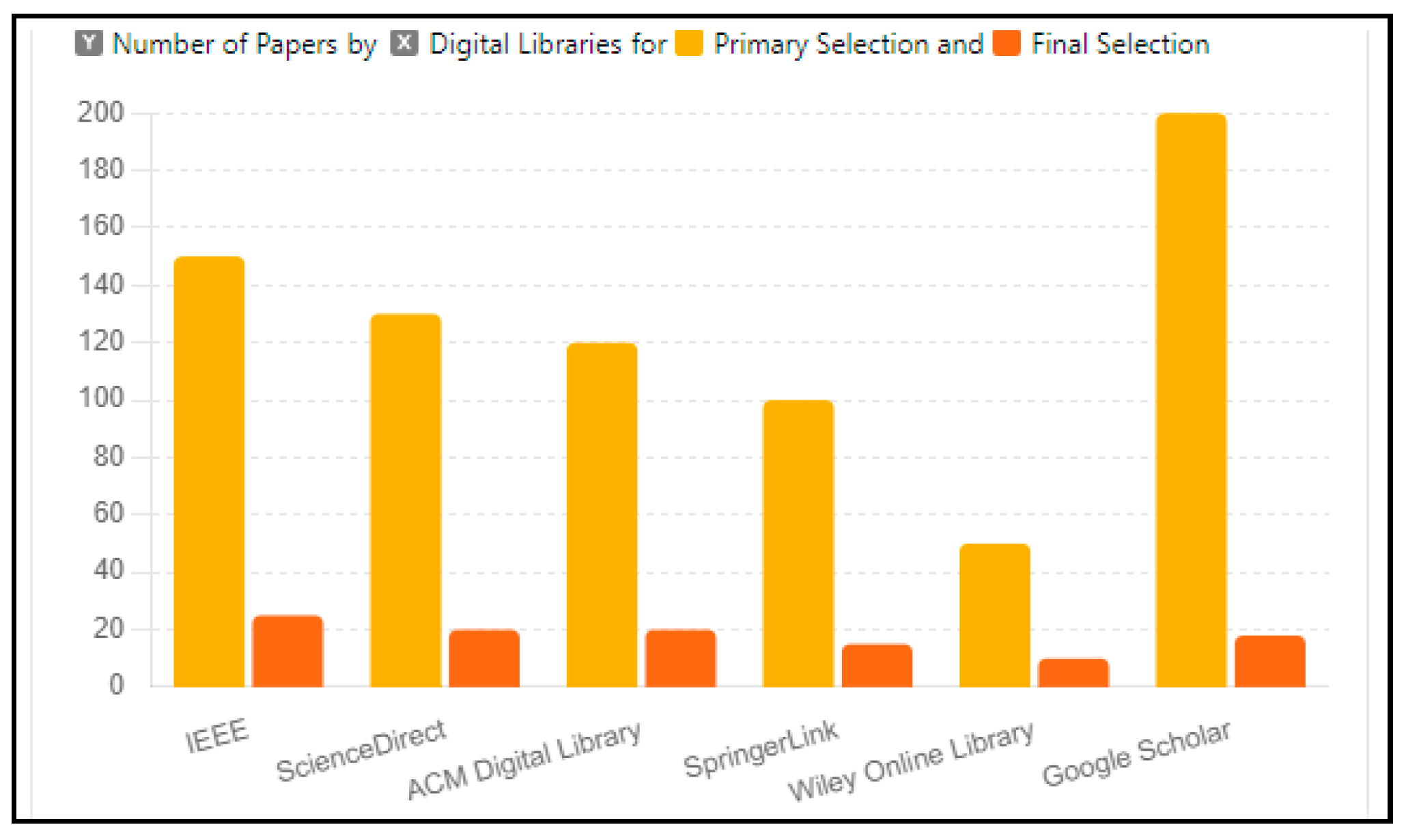

3). STEP 3: Search String Designing and Implementing

4). STEP 4: Screening and Selecting Studies

5). Step 5: Data Extraction

- Study Title

- Authors

- Publication Year

- Research Objectives

- Methodology

- Key Findings

- Limitations

- Recommendations for Future Research

6). STEP 6: Quality Assessment

- Clarity of research objectives

- The rigor of the methodology

- Internal and external validity of the research

- Contribution to the field

- Honesty regarding certain constraints and perspectives

7). STEP 7: Data Synthesis

8). STEP 8: The Findings

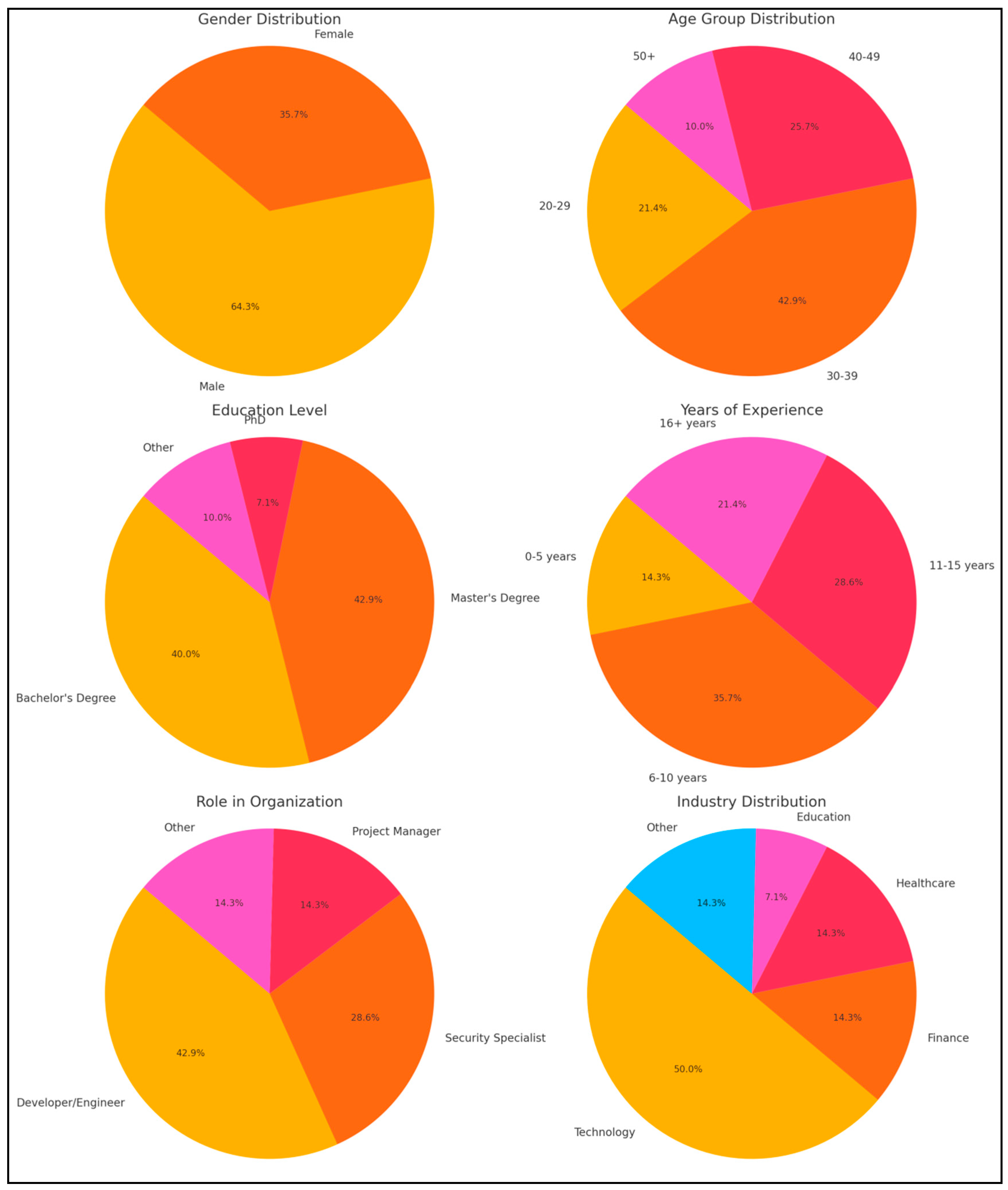

B. Phase 2: Empirical Study

- This method eliminated the necessity for scheduling meetings or global travel, allowing for efficient data collection from experts across continents.

- Utilizing online resources that are both cost-effective and accessible, such as Google Online Form, made the implementation process more practical.

1). Development of Questionnaire Survey

2). The Pilot of Questionnaire Survey

3). Data Collection Sources

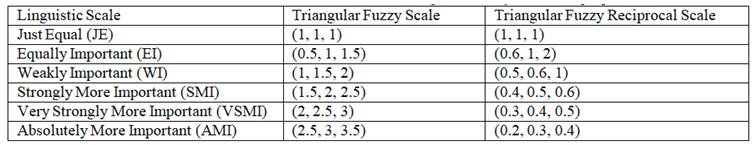

C. Phase 2: Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (Fuzzy-AHP)

- Anonymity: This strategy ensures that experts are not aware of what others say to avoid peer pressure or to conform to majority views.

- Iterative Process: This approach implements several rounds of elicitation in which experts can revise their assessments based on the group feedback, which can help in refining weights and minimizing bias. Such an iterative method makes the results more robust. Experts, who revised their initial weight assignments following group talks to minimize possible biases and reach agreement, carried out a two-round elicitation process.

- A sensitivity analysis was performed to determine the robustness of the decision-made framework to consider how changes in the weight assignment could potentially impact the ranking of success factors and variables in the overall sense. This enabled one to understand the contributing role of expert judgment on the outcomes better.

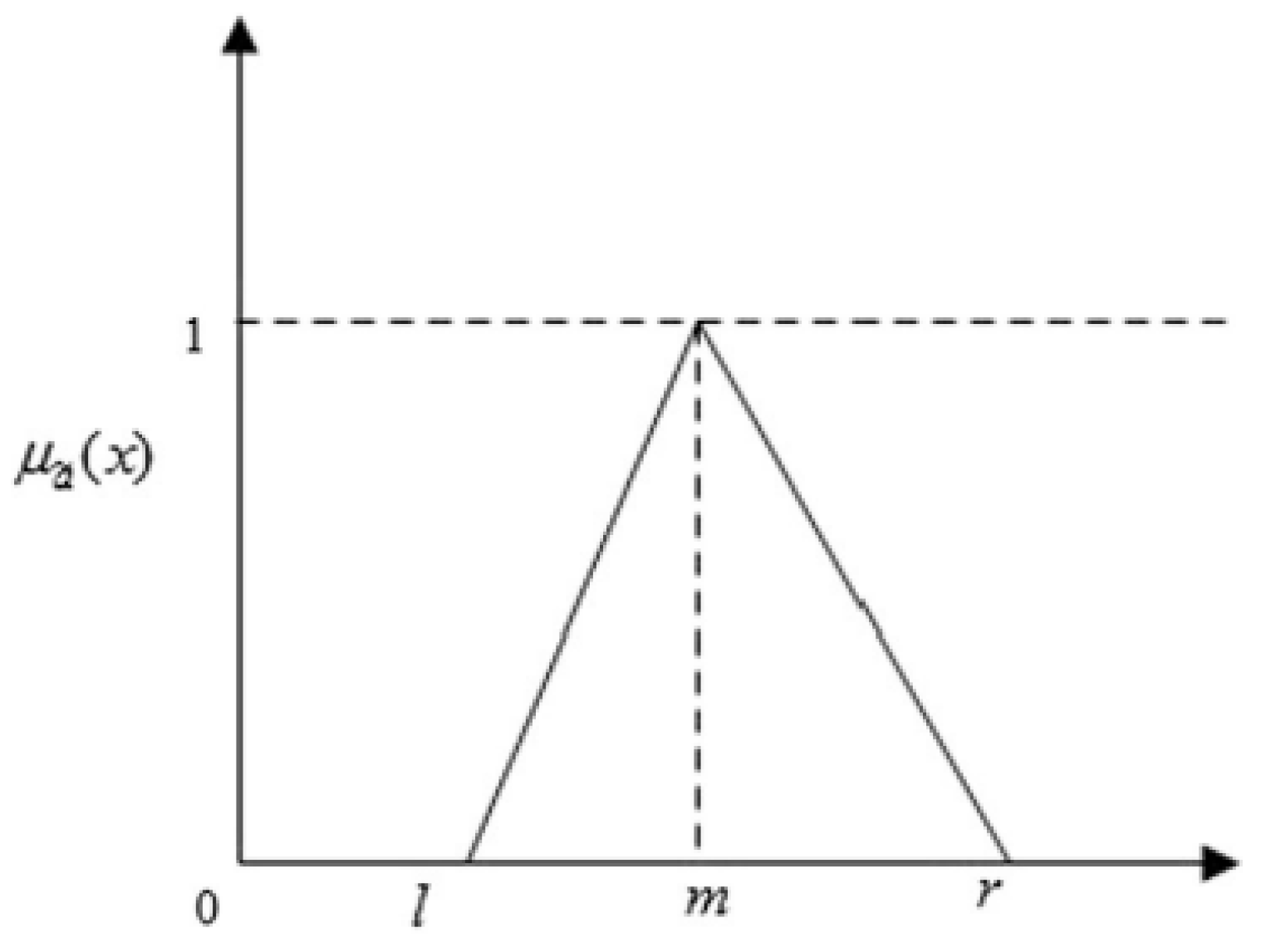

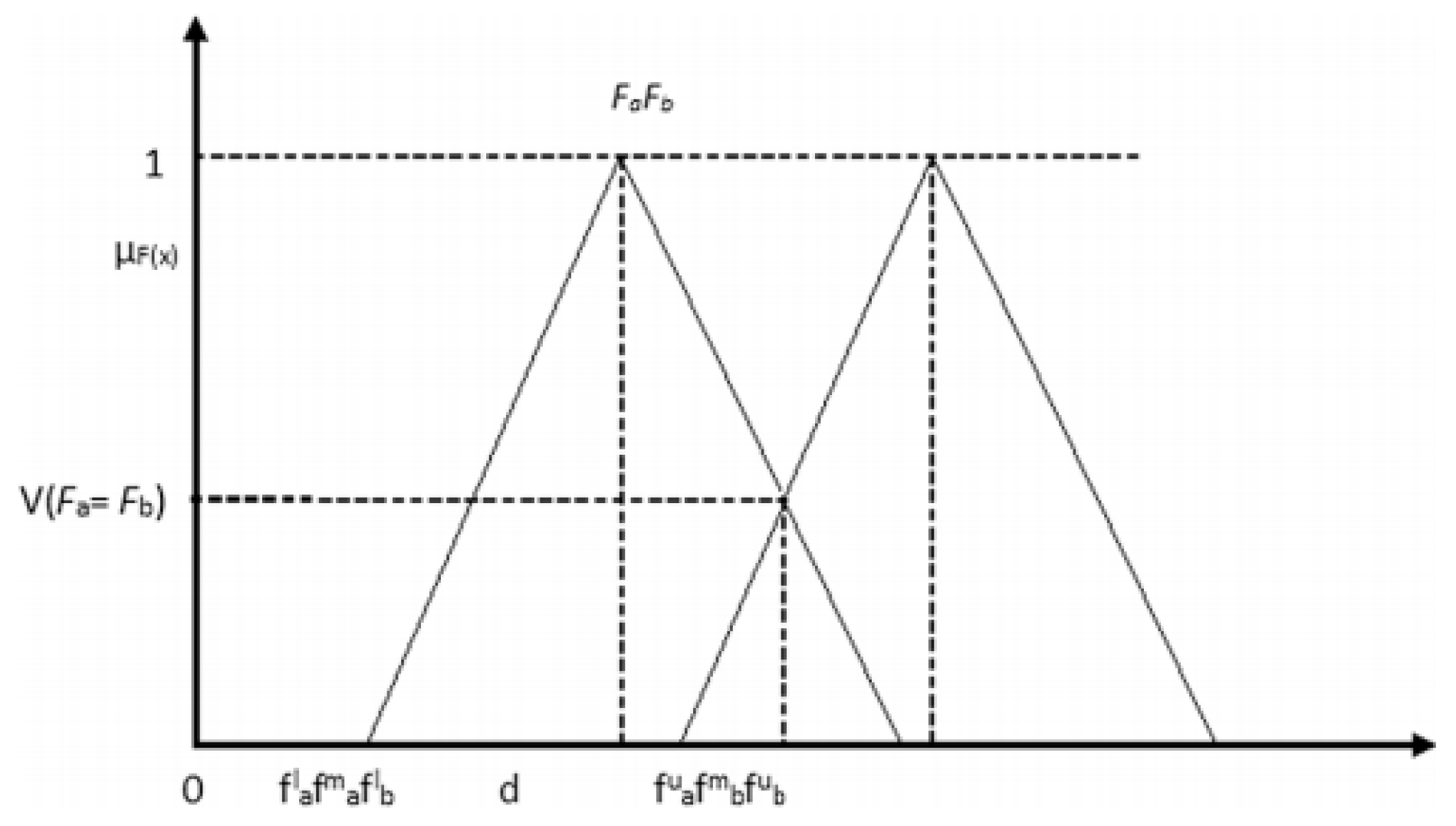

1). Fuzzy Set

2). Fuzzy-AHP

IV. Results and Data Analysis

A. RQ1: What Are the Human Factors (Success Factors and Security Vulnerabilities), as Reported in the Literature and Real-World Industry, That Influence Secure Software Development Projects?

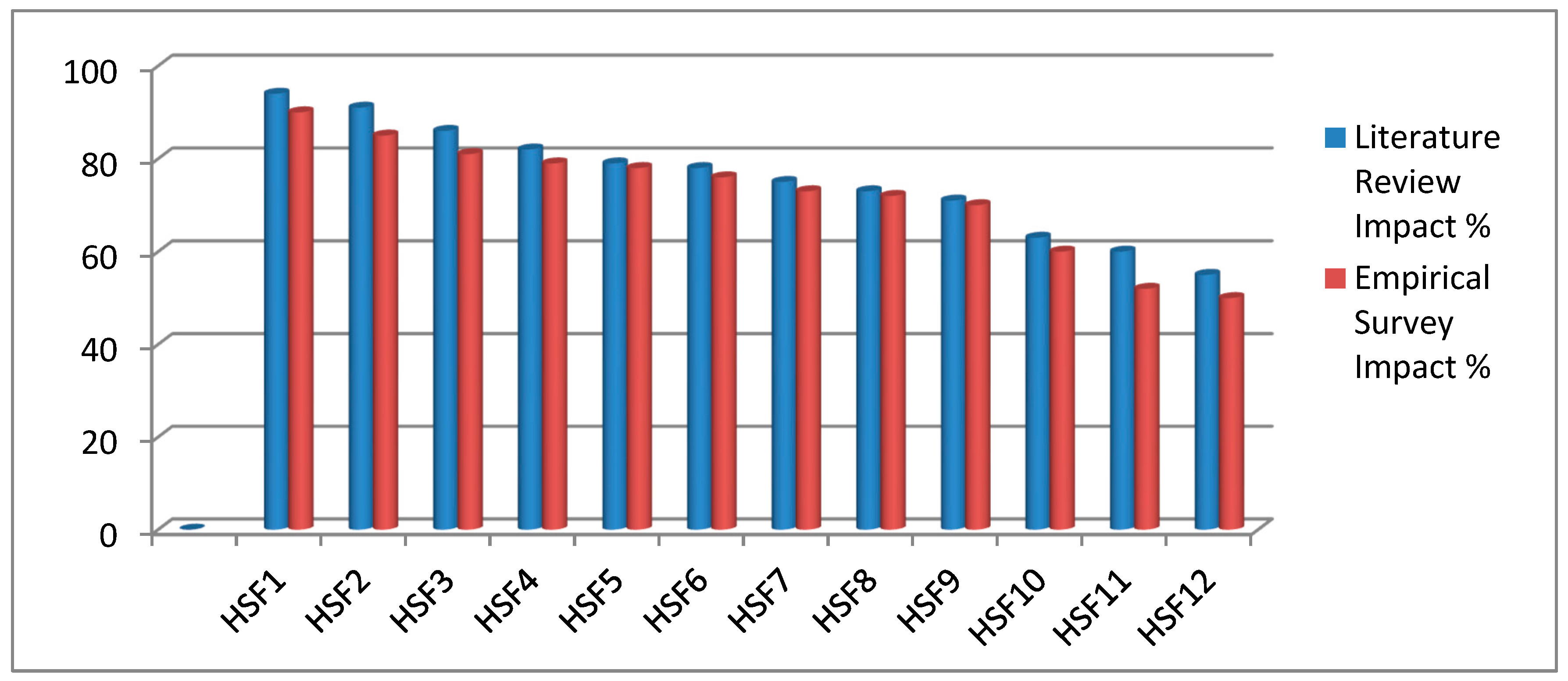

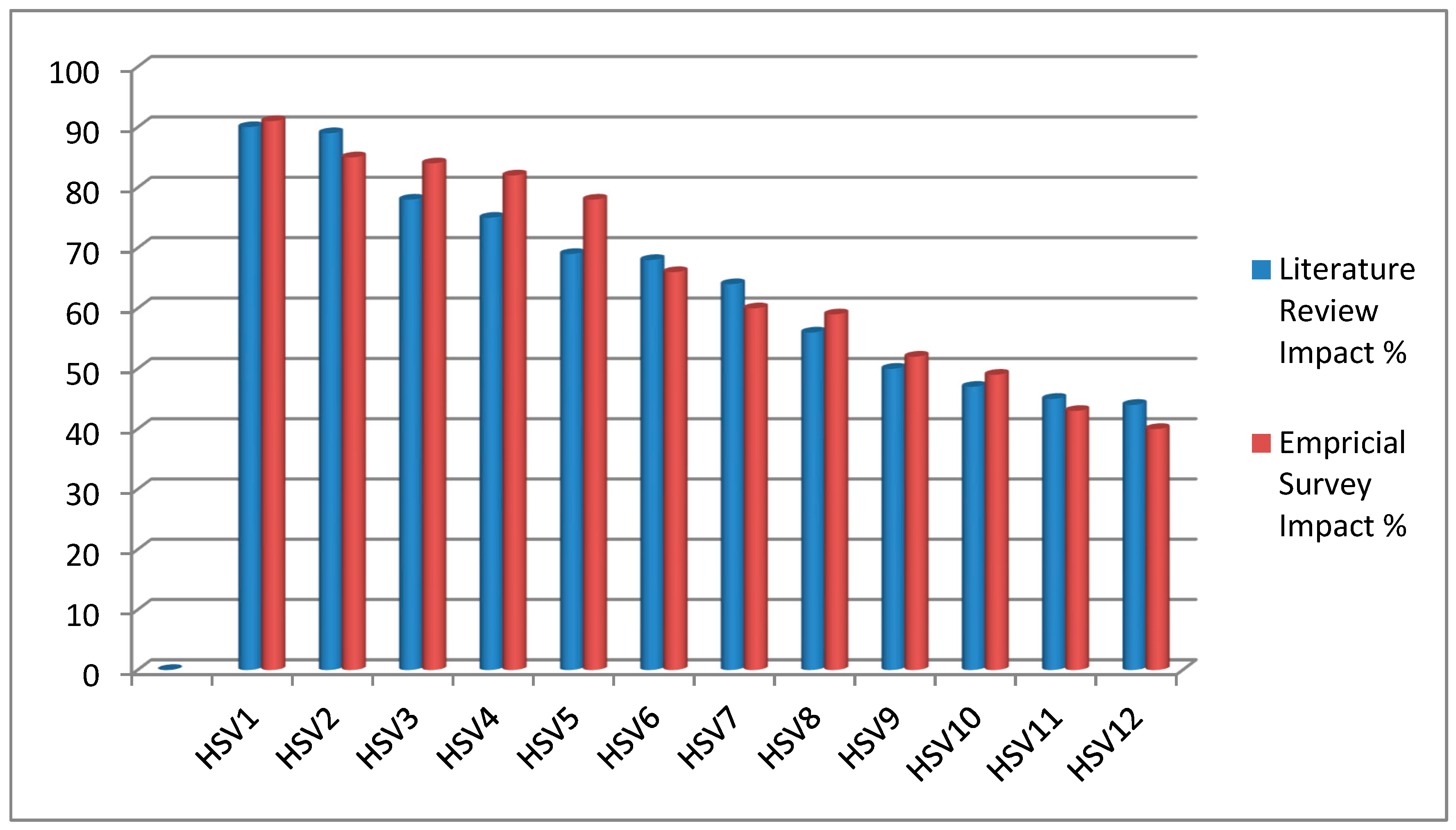

B. RQ2: What Are the Similarities and Differences Between HSFS and HSVS, as Identified Through Literature and Real-World Industries, That Influence SSD Projects?

- Top Success Factors: HSF1 (Skill and Expertise) and HSF2 (Awareness and Mindset) are rated highest in the literature review and empirical survey, indicating their critical importance in SSD projects.

- Consistency: Most factors show high consistency between literature and survey impacts, reflecting a general effect on their importance.

- Lower Impact Factors: HSF11 (Scalability and Flexibility) and HSF12 (Ethical and Cultural Sensitivity) are rated lower, suggesting these are less emphasized in practical settings than technical and managerial skills.

- Top Security Vulnerabilities: HSV1 (Lack of Security Awareness and Training) and HSV2 (Poor Communication and Collaboration) are consistently rated highest, highlighting their significant impact on security.

- Variability: There is more variability in the impact percentages of vulnerabilities than success factors, suggesting differences in perceptions of vulnerability impacts.

- Lower Impact Vulnerabilities: HSV10 (Cultural Issues), HSV11 (Insufficient Incident Response Preparedness), and HSV12 (Over-Reliance on Tools) are rated lower, indicating these are perceived as less critical compared to others.

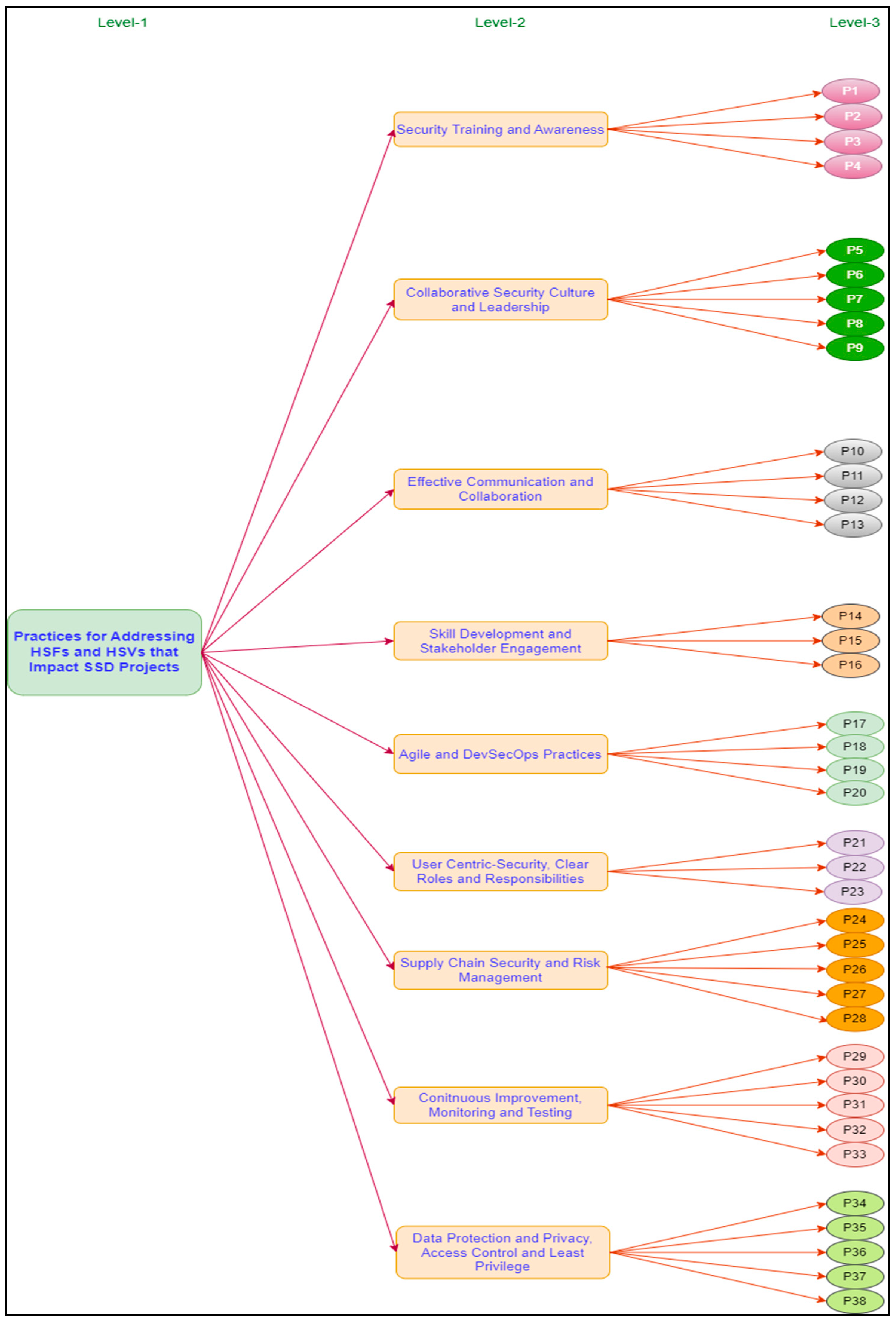

C. RQ3: What Are the Practices for Addressing HSFS and HSVS, as Identified Through Literature and Real-World Industries, That Influence SSD Projects?

D. RQ4: How Can a Decision-Making Framework Be Developed to Identify the Weights of HSFS and HSVS Practices That Impact SSD Projects?

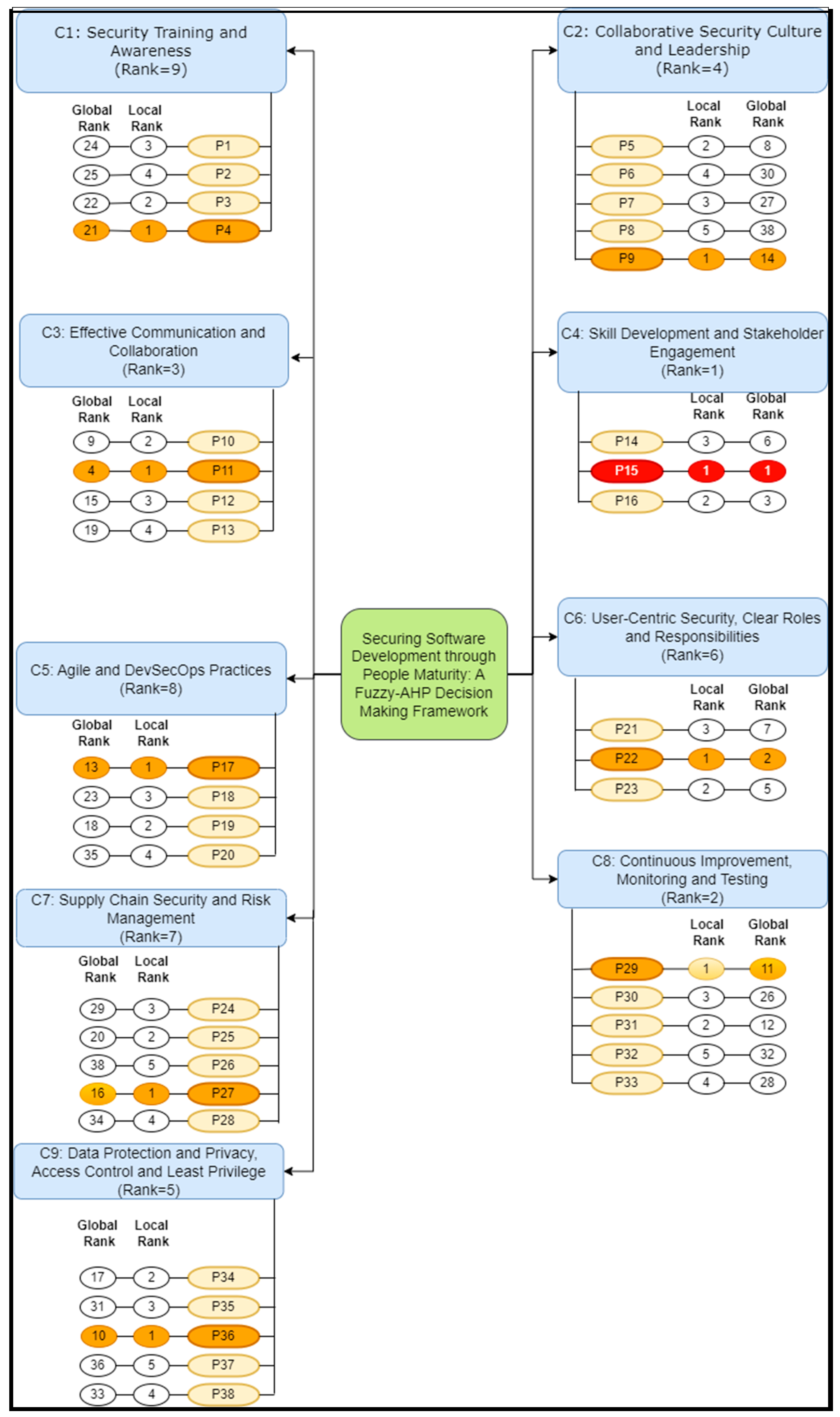

1). STEP 1: Sorting out a Problem's Components (HSFs and HSVs Practices) Using a Hierarchical Framework

2). STEP 2: Comparing Matrix Pairs

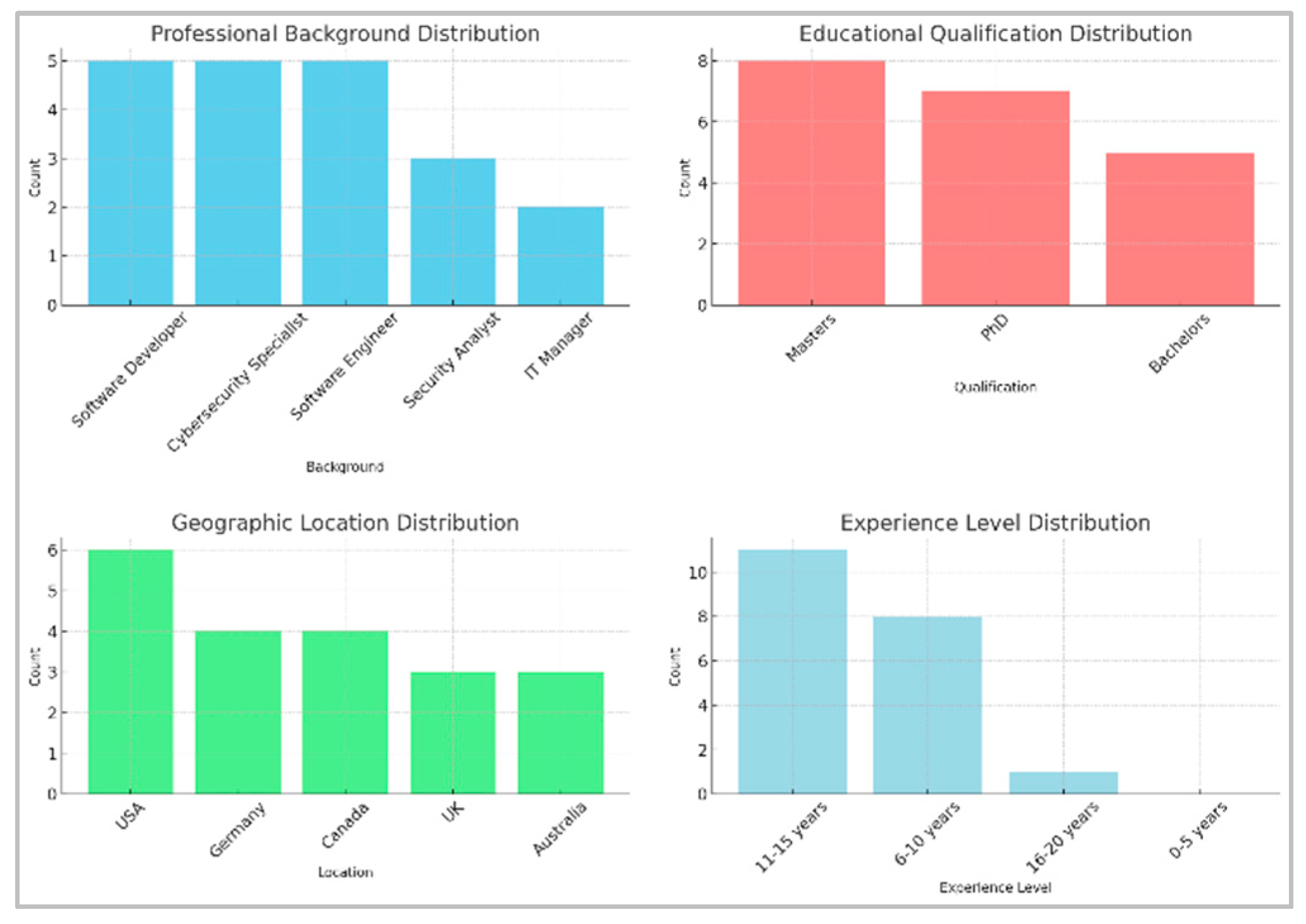

- Experts were chosen because of their extensive background in secure software development, cybersecurity, and decision-making frameworks. Their knowledge was directly applicable to the study’s goal of increasing security through people's maturity.

- Experts needed to have a minimum of [X] years of professional experience in secure software development, cybersecurity, or similar fields to guarantee that they had an in-depth knowledge of the issues at hand.

- The sample comprised professionals who were software developers, cybersecurity analysts, and IT managers, all of whom had contributed valuable knowledge from their domains.

- The professionals had high degrees in computer science, cybersecurity, software engineering, and other domains, some of them had security management certificates and project management certificates.

- Experts were picked from a varied array of geographic areas including North America, Europe, and Asia to ensure the framework include it involves a wide variety of security practices and people maturity models.

- The sample of 20 experts was chosen to create a balanced representation of professionals from different sectors and geographical areas to be representative of the relevant expertise for the fuzzy-AHP analysis.

- Although for the expert sample, we strictly selected people to have diversity and relevance of expertise, one needs to bear in mind that, nevertheless, there can exist some biases, especially associated with procedures typical for a certain industry or peculiarities of secure software development practices in different regions.

3). STEP 3: Consistency Evaluation

4). STEP 4: Identification of Local Priority Weights of HSFS and HSVS of Practice Categories

- a.

- A Numerical Example

5). STEP 5: Calculation of Local and Global Ranks of HSF and HSV Practices

V. Securing Software Development Through People Maturity: A Fuzzy-AHP Decision-Making Framework

VI. Implications of the Study

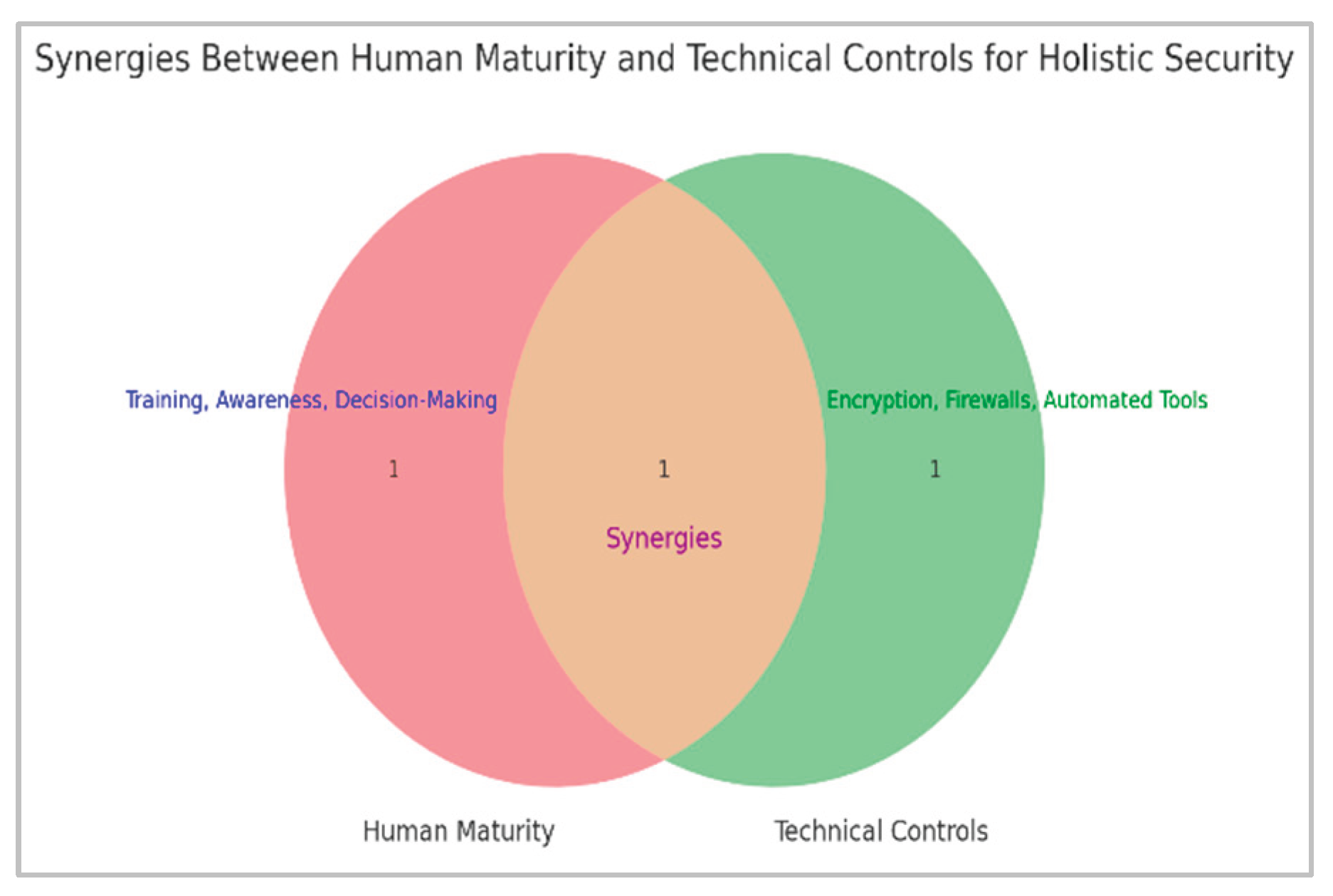

- Integration between technical controls and human factors: It meshes with the growth in human maturity, better decision-making, risk awareness, and adherence to security protocols, which could enhance automated security tools, encryption, and other technical measures' adoption and efficiency. For instance, the greater the level of human maturity in security practices, the more likely humans would use technical tools such as automated intrusion detection systems or encryption in their daily activities. The union of a maturing workforce and technical controls ensures a layered defense mechanism that enhances the general security posture. The framework can be stretched to address how technical measures, like real-time tracking or vulnerability scanning, are to be intertwined with human elements, like training and awareness of risk so that security is not only automated but also actively managed by a trained crew.

- Comprehensive Security Framework: “Securing Software Development through People Maturity: A Fuzzy-AHP Decision-Making Framework” offers a wider perspective on securing software development by incorporating people maturity and technical security controls. According to the framework, software security should not be dependent on one of the dimensions (human or technical) but rather it has to balance both of them. With the alignment of people maturity and technical security controls, like leveraging the use of automatic tools that need human intervention or training employees on how to make effective use of encryption, organizations will be able to bolster the level of security resilience."

- Illustrating Synergies between Human and Technical Factors:

- Enhanced Decision-Making in Security Investments: The allocation of security resources is therefore facilitated by the Fuzzy-AHP decision-making framework, which gives organizations a quantitative method of evaluating the maturity of their workforce and software about security as well as priority ranking of investment in security throughout the software development life cycle. This method assists firms in getting better value for the resources used by identifying areas that can offer improved security results.

- Integration of Human Factors in Security Protocols: The earlier approaches to modeling software security usually come with all the methodologies owning to resources-based technologies and have qualities neglecting the human aspects. This research calls for incorporating people's maturity into security to foster the right approach to secure software development. Thus, it can be described that the general improvement of the security situation in various companies can be achieved with the help of multiple programs, human development, training, and awareness.

- Improved Risk Management: By including people's maturity in a list of factors that can affect software security, the framework helps organizations minimize the problems related to the human factor. This takes a different perspective on risk management, where it protects certain technological lapses and people-related issues.

- Adaptability to Different Organizational Contexts: Since the Fuzzy-AHP model is created and designed to be scalable and adaptive, it can fit well in different organizational settings and across different organization sizes. This also means that it can be applied across multiple industries depending on the security needs, organizational readiness, and the company’s strategic and tactical aspirations and goals. Additionally, this flexibility places the framework in high-essential security areas like finance, healthcare, and government realms.

- Guidance for Policy and Standards Development: This study's people maturity and decision-making focus might inform the formation of new standards or policies to advance the secure software industry. This work may be helpful for policymakers and industry groups who wish to adjust security guidance based on the findings here, which could motivate organizations to consider human factors in their software security practices.

- Contribution to Future Research in Secure Software Development: The work provides directions for future research by presenting a new method incorporating human maturity, fuzzy logic, and AHP into the process. For the above reasons, future studies can extend this research to other decision-making techniques, develop a more detailed measure of people maturity integration, or test its applicability to other software development paradigms.

- Practical Applications in Security Training and Development: This work has shown how one may gain from putting resources into security training and development programs that are customized to suit the maturity of the development teams in an organization. Better training schemes and continuing staff development in organizations are possible to establish higher levels of security awareness and take the necessary actions to produce more secure software.

- Bridging the Gap Between Security and Development Teams: The framework will also enhance a closer working relationship between the security and development teams since people's aspects of security risks can now be effectively evaluated and addressed through a clear mechanism. This enhanced communication is essential to prevent the gaps and misinterpretations that are usually associated with the emergence of new security vulnerabilities as new software is developed.

VII. Summary and Limitations of the Study

- Limited Scope of Participants: While the findings from this study provide valuable insights within the context of secure software development organizations, Cybersecurity, and IT management, their applicability to other sectors or geographic areas may be limited. People's maturity in the study sample was evaluated on a limited and particular number of organizations and professionals. As this may not be a comprehensive list, practices and measures on security and the level of maturity exist in practice across different industries or other geographical locations.

- Subjective Nature of Fuzzy Logic: Despite the effort of the Fuzzy-AHP methods to reduce subjectivity in decision-making, the process of determining fuzzy numbers is still the expert's subjective judgment. Therefore, the measures and the findings depend on the skills and perceptions of the assessors, which may lead to variations in the results.

- Focus on Human Factors: This research mainly deals with the human factors in software development, including skill, knowledge awareness, and organizational culture. It is also an amalgamation of risk. However, other critical factors include technological tools, process maturity, and infrastructure, which significantly affect software security and are not captured in this framework.

- The Complexity of Implementation: Using the Fuzzy-AHP approach, the decision models are sophisticated, and incorporating software security techniques is quite challenging. As will be seen in the subsequent sections, applying the framework to organizations may be feasible but challenging, particularly for organizations with limited resources or peculiar domain knowledge.

- Dynamic Nature of Software Development: The overall landscape of software development is constantly changing, and there are frequent changes in the approach to security. It may need updating occasionally because the appreciation of some security practices and people's maturity factors may change with time.

- Absence of Longitudinal Analysis: The study gives a cross-section of people's maturity in software security at a particular time. However, it fails to depict the development of people's maturity and security effectiveness. As for the research that should be carried out in the future, it might be useful to evaluate the changes in the future outcomes of long-term software security if maturity is increased. The robustness of this framework can be further strengthened by future studies that involve longitudinal assessments in the determination of effectiveness over time. Such investigations would give us beneficial information about the mannerism in which the framework aligns itself to the new threats of security and shifting attitudes of humans in software development crews.

- Even though the current study offers interesting perspectives on the ability to secure a software development process with people's maturity, the sample used during the empirical validation was constrained by the diversity of industry and coverage geography. This weak spot could make the findings applicable to other sectors or regions with various security requisites and practices. To improve the generalisability of findings, future studies will focus on increasing a broad range of participants, not only industry-wise (healthcare, finance, or manufacturing) but also geographical-wise (different countries, regions) with the different regulatory frameworks and security practices. This extension will give a better understanding of how the framework, Fuzzy-AHP performs in different contexts and make the findings more applicable to a larger population.

VIII. Conclusion and Future Direction

- Future Work

- i.

- Leveraging AI for Automated Security: Generative AI has the most valuable application in automating security controls across the SDLC process. Future studies should explore the possibility of using AI to determine the weakness of a model, estimate the risks in the future development of the model, and produce far safer code. However, the issues of ethics and bias in Artificial Intelligence systems also need to be resolved to guarantee that security measures created with AI are ethical.

- ii.

- Enhancing People Maturity with AI-Driven Insights: People maturity models successfully target enhancing organizational enablers and a developer’s competency levels. Embedding generative AI could give instructions that advance human factors, such as decision-making, security consciousness, and teamwork. Possibilities of future work can be to investigate how AI powers feedback and training and how AI-based simulations can enhance people's maturity in decision-making, especially regarding security.

- iii.

- AI-Augmented Threat Intelligence: In today’s complex cybersecurity environment, AI is most valuable as a fast and proactive defense mechanism. As for future work, further opportunities should be examined regarding integrating AI-generated threat intelligence into secure software development, where the anti-phishing process shall be more adaptive to emerging security threats. This would require building AI systems that evolve with the new threats and patterns being adopted in the market and allow developers to quickly get the most current practices in security.

- iv.

- Collaboration between AI and Human Developers: Subsequent studies may consider the interaction of generative AI with human engineers and how to secure this cooperation. Nevertheless, the use of AI as an aid to creating secure code requires human supervision. Research could include environments in which the content is generated based on AI algorithms combined with professional knowledge to satisfy high security.

- v.

- Addressing AI-Generated Code Vulnerabilities: An essential direction for future work is to consider AI-generated code as the aspect that introduces specific code weaknesses. Since more developers rely on generative AI to generate code, the explicit security threats with AI-written code must be known. At the same time, future studies should look into how these are assessed, audited, and managed to have a safer result.

- vi.

- Ethical Considerations in AI for Security: Using AI in SSD considers many ethical issues while emerging and evolving. The deployment of AI in Secure Software Development, particularly AI software development models, raises numerous ethical questions. Insofar as multiple kinds of ethical frameworks and AI governance policies may be integrated into security-focused software development, there is room for future work to explore what it means to ensure that AI used in the process is not itself unethical – that is, does not reintroduce bias, obscurantism, or other unwanted elements.

Acknowledgment

References

- C. Del-Real, E. De Busser, and B. van den Berg, "Shielding software systems: A comparison of security by design and privacy by design based on a systematic literature review," Computer Law & Security Review, vol. 52, p. 105933, 2024/04/01/ 2024.

- M. Jørgensen and E. Escott, "Relative estimates of software development effort: Are they more accurate or less time-consuming to produce than absolute estimates, and to what extent are they person-independent?," Information and Software Technology, vol. 143, p. 106782, 2022/03/01/ 2022.

- R. A. Khan, M. A. Akbar, S. Rafi, A. O. Almagrabi, and M. Alzahrani, "Evaluation of requirement engineering best practices for secure software development in GSD: An ISM analysis," Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, vol. 36, p. e2594, 2024.

- L. Barros, C. Tam, and J. Varajão, "Agile software development projects–Unveiling the human-related critical success factors," Information and Software Technology, vol. 170, p. 107432, 2024/06/01/ 2024.

- A. Jadhav and S. K. Shandilya, "Reliable machine learning models for estimating effective software development efforts: A comparative analysis," Journal of Engineering Research, vol. 11, pp. 362-376, 2023/12/01/ 2023.

- A. Nurwidyantoro, M. Shahin, M. R. V. Chaudron, W. Hussain, R. Shams, H. Perera, et al., "Human values in software development artefacts: A case study on issue discussions in three Android applications," Information and Software Technology, vol. 141, p. 106731, 2022/01/01/ 2022.

- S. Adolph, P. Kruchten, and W. Hall, "Reconciling perspectives: A grounded theory of how people manage the process of software development," Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 85, pp. 1269-1286, 2012/06/01/ 2012.

- V. Anu, K. Z. Sultana, and B. K. Samanthula, "A Human Error Based Approach to Understanding Programmer-Induced Software Vulnerabilities," in 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSREW), 2020, pp. 49-54.

- J. Pottebaum, J. Rossel, J. Somorovsky, Y. Acar, R. Fahr, P. A. Cabarcos, et al., "Re-Envisioning Industrial Control Systems Security by Considering Human Factors as a Core Element of Defense-in-Depth," in 2023 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), 2023, pp. 379-385.

- R. Fujdiak, P. Mlynek, P. Mrnustik, M. Barabas, P. Blazek, F. Borcik, et al., "Managing the Secure Software Development," in 2019 10th IFIP International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security (NTMS), 2019, pp. 1-4.

- R. M. Fontana, I. M. Fontana, P. A. da Rosa Garbuio, S. Reinehr, and A. Malucelli, "Processes versus people: How should agile software development maturity be defined?," Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 97, pp. 140-155, 2014/11/01/ 2014.

- J. Martins, F. Branco, and H. Mamede, "Combining low-code development with ChatGPT to novel no-code approaches: A focus-group study," Intelligent Systems with Applications, vol. 20, p. 200289, 2023/11/01/ 2023.

- A. Averin and N. Zyulyarkina, "Characteristics of a Random Vector Obtained Using Human-Computer Interaction," in 2020 Global Smart Industry Conference (GloSIC), 2020, pp. 271-275.

- H. Zhanwei, H. Song, H. Bin, and Y. Yi, "Software security testing based on typical SSD:A case study," in 2010 3rd International Conference on Advanced Computer Theory and Engineering(ICACTE), 2010, pp. V2-312-V2-316.

- F. Alnaseef, M. Niazi, S. Mahmood, M. Alshayeb, and I. Ahmad, "Towards a successful secure software acquisition," Information and Software Technology, vol. 164, p. 107315, 2023/12/01/ 2023.

- R. van Solingen, E. Berghout, R. Kusters, and J. Trienekens, "From process improvement to people improvement: enabling learning in software development," Information and Software Technology, vol. 42, pp. 965-971, 2000/11/15/ 2000.

- V. Casola, A. De Benedictis, C. Mazzocca, and V. Orbinato, "Secure software development and testing: A model-based methodology," Computers & Security, vol. 137, p. 103639, 2024/02/01/ 2024.

- R. A. Khan, S. U. Khan, H. U. Khan, and M. Ilyas, "Systematic Literature Review on Security Risks and its Practices in Secure Software Development," IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 5456-5481, 2022.

- P. Wang, S. Liu, A. Liu, and W. Jiang, "Detecting security vulnerabilities with vulnerability nets," Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 208, p. 111902, 2024/02/01/ 2024.

- A. Alzahrani and R. A. Khan, "Secure software design evaluation and decision making model for ubiquitous computing: A two-stage ANN-Fuzzy AHP approach," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 153, p. 108109, 2024/04/01/ 2024.

- J. Harmening, "Chapter 24 - Information Security Essentials for IT Managers: Protecting Mission-Critical Systems," in Computer and Information Security Handbook (Fourth Edition), J. R. Vacca, Ed., ed: Morgan Kaufmann, 2025, pp. 423-432.

- S. K. Katsikas, "Chapter 35 - Risk Management," in Computer and Information Security Handbook (Fourth Edition), J. R. Vacca, Ed., ed: Morgan Kaufmann, 2025, pp. 583-599.

- A. S. A. Alghawli and T. Radivilova, "Resilient cloud cluster with DevSecOps security model, automates a data analysis, vulnerability search and risk calculation," Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 107, pp. 136-149, 2024/11/01/ 2024.

- R. A. Khan, S. U. Khan, M. A. Akbar, and M. Alzahrani, "Security risks of global software development life cycle: Industry practitioner's perspective," Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, vol. 36, p. e2521, 2024.

- O. O. Olusanya, R. G. Jimoh, S. Misra, and J. B. Awotunde, "A neuro-fuzzy security risk assessment system for software development life cycle," Heliyon, vol. 10, p. e33495, 2024/07/15/ 2024.

- I. Gershfeld and, A. Sturm, "Evaluating the effectiveness of a security flaws prevention tool," Information and Software Technology, vol. 170, p. 107427, 2024/06/01/ 2024.

- R. A. Khan, S. U. Khan, M. Ilyas, and M. Y. Idris, "The State of the Art on Secure Software Engineering: A Systematic Mapping Study," presented at the Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Trondheim, Norway, 2020.

- R. A. Khan, S. U. Khan, and M. Ilyas, "Exploring Security Procedures in Secure Software Engineering: A Systematic Mapping Study," presented at the Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2022.

- L. Hofmans, A. van der Stappen, and W. van den Bos, "Developmental structure of digital maturity," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 157, p. 108239, 2024/08/01/ 2024.

- T. Jukić, I. Pluchinotta, R. Hržica, and S. Vrbek, "Organizational maturity for co-creation: Towards a multi-attribute decision support model for public organizations," Government Information Quarterly, vol. 39, p. 101623, 2022/01/01/ 2022.

- C. Koolen, K. Wuyts, W. Joosen, and P. Valcke, "From insight to compliance: Appropriate technical and organisational security measures through the lens of cybersecurity maturity models," Computer Law & Security Review, vol. 52, p. 105914, 2024/04/01/ 2024.

- M. D. Kadenic, K. Koumaditis, and L. Junker-Jensen, "Mastering scrum with a focus on team maturity and key components of scrum," Information and Software Technology, vol. 153, p. 107079, 2023/01/01/ 2023.

- C. Glasauer, "The Prevent-Model: Human and Organizational Factors Fostering Engineering of Safe and Secure Robotic Systems," Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 195, p. 111548, 2023/01/01/ 2023.

- E. Abad-Segura, A. Infante-Moro, M.-D. González-Zamar, and E. López-Meneses, "Influential factors for a secure perception of accounting management with blockchain technology," Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, vol. 10, p. 100264, 2024/06/01/ 2024.

- B. De Win, R. Scandariato, K. Buyens, J. Grégoire, and W. Joosen, "On the secure software development process: CLASP, SDL and Touchpoints compared," Information and Software Technology, vol. 51, pp. 1152-1171, 2009/07/01/ 2009.

- B. Kitchenham, O. Pearl Brereton, D. Budgen, M. Turner, J. Bailey, and S. Linkman, "Systematic literature reviews in software engineering – A systematic literature review," Information and Software Technology, vol. 51, pp. 7-15, 2009/01/01/ 2009.

- B. Kitchenham and S. Charters, "Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering," 2007.

- N. Dissanayake, A. Jayatilaka, M. Zahedi, and M. A. Babar, "Software security patch management - A systematic literature review of challenges, approaches, tools and practices," Information and Software Technology, vol. 144, p. 106771, 2022/04/01/ 2022.

- A. Shukla, B. Katt, L. O. Nweke, P. K. Yeng, and G. K. Weldehawaryat, "System security assurance: A systematic literature review," Computer Science Review, vol. 45, p. 100496, 2022/08/01/ 2022.

- B. Kitchenham, "Procedures for performing systematic reviews," Keele, UK, Keele University, vol. 33, pp. 1-26, 2004.

- T. C. Lethbridge, S. E. Sim, and J. Singer, "Studying Software Engineers: Data Collection Techniques for Software Field Studies," Empirical Software Engineering, vol. 10, pp. 311-341, 2005/07/01 2005.

- J. W. Creswell, Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches, 3rd edition: Sage, London, 2009.

- S. Wagner, D. M. Fernández, M. Felderer, A. Vetrò, M. Kalinowski, R. Wieringa, et al., "Status Quo in Requirements Engineering: A Theory and a Global Family of Surveys," ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol., vol. 28, p. Article 9, 2019.

- M. Humayun, M. Niazi, M. Assiri, and M. Haoues, "Secure Global Software Development: A Practitioners’ Perspective," Applied Sciences, vol. 13, p. 2465, 2023.

- M. Ilyas, S. U. Khan, H. U. Khan, and N. Rashid, "Software integration model: An assessment tool for global software development vendors," Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, vol. n/a, p. e2540, 2023.

- B. Kitchenham and S. L. Pfleeger, "Principles of survey research part 6: data analysis," SIGSOFT Softw. Eng. Notes, vol. 28, pp. 24–27, 2003.

- M. A. Akbar, A. A. Khan, and S. Rafi, "A systematic decision-making framework for tackling quantum software engineering challenges," Automated Software Engineering, vol. 30, p. 22, 2023/07/26 2023.

- Rafiq, A. Khan, I. Keshta, Hussein A. Al Hashimi, Alaa O. Almagrabi, Hathal S. Alwageed, and M. Alzahrani, "A Fuzzy-AHP Decision-Making Framework for Optimizing Software Maintenance and Deployment in Information Security Systems," Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, vol. 37, p. e2758, 2025.

- W. Alhakami, "Enhancing Cybersecurity Competency in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Fuzzy Decision-Making Approach," Computers, Materials and Continua, vol. 79, pp. 3211-3237, 2024/05/15/ 2024.

- A. Alzahrani and R. A. Khan, "Secure software design evaluation and decision making model for ubiquitous computing: A two-stage ANN-Fuzzy AHP approach," Computers in Human Behavior, p. 108109, 2023/12/26/ 2023.

- L. A. Zadeh, "Fuzzy Sets, Fuzzy Logic, and Fuzzy Systems," Advances in Fuzzy Systems — Applications and Theory, vol. 6, pp. 1-840, 1996.

- F. Marimon, M. Casadesus, and I. Heras-Saizarbitoria, "ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 standards: An international diffusion model," International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 26, pp. 141-165, 02/01 2006.

- M. Ayhan, "A Fuzzy AHP Approach for Supplier Selection Problem: A Case Study in a Gear Motor Company," International Journal of Managing Value and Supply Chains, vol. 4, 10/09 2013.

- I. Chamodrakas, D. Batis, and D. Martakos, "Supplier selection in electronic marketplaces using satisficing and fuzzy AHP," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 37, pp. 490-498, 2010/01/01/ 2010.

- D.-Y. Chang, "Applications of the extent analysis method on fuzzy AHP," European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 95, pp. 649-655, 1996/12/20/ 1996.

- D. Stelzer and W. Mellis, "Success factors of organizational change in software process improvement," Software Process: Improvement and Practice, vol. 4, pp. 227-250, 1998.

- R. Kaur, T. Klobučar, and D. Gabrijelčič, "Harnessing the power of language models in cybersecurity: A comprehensive review," International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, vol. 5, p. 100315, 2025/06/01/ 2025.

- A. R. Khan, S. Khan, and M. Ilyas, Exploring Security Procedures in Secure Software Engineering: A Systematic Mapping Study, 2022.

- M. Aquino, J. Griffith, T. Vattaparambil, S. Munce, M. Hladunewich, and E. Seto, "Patients’ and Providers’ Perspectives on and Needs of Telemonitoring to Support Clinical Management and Self-care of People at High Risk for Preeclampsia: Qualitative Study," JMIR Human Factors, vol. 9, 2022/01/01/ 2022.

- M. Peixoto, D. Ferreira, M. Cavalcanti, C. Silva, J. Vilela, J. Araújo, et al., "The perspective of Brazilian software developers on data privacy," Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 195, p. 111523, 2023/01/01/ 2023.

- K. Petrenko, A. Mashatan, and F. Shirazi, "Assessing the quantum-resistant cryptographic agility of routing and switching IT network infrastructure in a large-size financial organization," Journal of Information Security and Applications, vol. 46, pp. 151-163, 2019/06/01/ 2019.

- C. D. Tupper, "9 - Data Organization Practices," in Data Architecture, C. D. Tupper, Ed., ed Boston: Morgan Kaufmann, 2011, pp. 175-190.

- A. Austin, C. Holmgreen, and L. Williams, "A comparison of the efficiency and effectiveness of vulnerability discovery techniques," Information and Software Technology, vol. 55, pp. 1279-1288, 2013/07/01/ 2013.

- M. Tanque and H. J. Foxwell, "Chapter Three - Cyber risks on IoT platforms and zero trust solutions," in Advances in Computers. vol. 131, A. R. Hurson, Ed., ed: Elsevier, 2023, pp. 79-148.

- Z. Almahmoud, P. D. Yoo, E. Damiani, K.-K. R. Choo, and C. Y. Yeun, "Forecasting Cyber Threats and Pertinent Mitigation Technologies," Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 210, p. 123836, 2025/01/01/ 2025.

- R. N. Rajapakse, M. Zahedi, M. A. Babar, and H. Shen, "Challenges and solutions when adopting DevSecOps: A systematic review," Information and Software Technology, vol. 141, p. 106700, 2022/01/01/ 2022.

- R. A. Khan, S. U. Khan, M. A. Akbar, and M. Alzahrani, "Security risks of global software development life cycle: Industry practitioner's perspective," Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, vol. 36, pp. 1-34, 2023.

- C. E. Budde, A. Karinsalo, S. Vidor, J. Salonen, and F. Massacci, "CSEC+ framework assessment dataset: Expert evaluations of cybersecurity skills for job profiles in Europe," Data in Brief, vol. 48, p. 109285, 2023/06/01/ 2023.

- T. Tam, A. Rao, and J. Hall, "The good, the bad and the missing: A Narrative review of cyber-security implications for australian small businesses," Computers & Security, vol. 109, p. 102385, 2021/10/01/ 2021.

- X. Liang, C. Konstantinou, S. Shetty, E. Bandara, and R. Sun, "Decentralizing Cyber Physical Systems for Resilience: An Innovative Case Study from A Cybersecurity Perspective," Computers & Security, vol. 124, p. 102953, 2023/01/01/ 2023.

- N. Medeiros, N. Ivaki, P. Costa, and M. Vieira, "Trustworthiness models to categorize and prioritize code for security improvement," Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 198, p. 111621, 2023/04/01/ 2023.

- J. M. Corbin and A. Strauss, "Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria," Qualitative sociology, vol. 13, pp. 3-21, 1990.

- A. A. Khan, M. Shameem, M. Nadeem, and M. A. Akbar, "Agile trends in Chinese global software development industry: Fuzzy AHP based conceptual mapping," Applied Soft Computing, vol. 102, p. 107090, 2021/04/01/ 2021.

- R. A. Khan, M. Y. Idris, S. U. Khan, M. Ilyas, S. Ali, A. U. Din, et al., "An Evaluation Framework for Communication and Coordination Processes in Offshore Software Development Outsourcing Relationship: Using Fuzzy Methods," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 112879-112906, 2019.

- T. Yaghoobi, "Prioritizing key success factors of software projects using fuzzy AHP," Journal of Software: Evolution and Process, vol. 30, p. e1891, 09/11 2017.

- A. K. Barbara, B. D. Budgen, and O. P. Brereton, "Using mapping studies as the basis for further researchA participant-observer case study," Information Software Technology, vol. 53, pp. 638-651, 2011.

- W. S. Admass, Y. Y. Munaye, and A. A. Diro, "Cyber security: State of the art, challenges and future directions," Cyber Security and Applications, vol. 2, p. 100031, 2024/01/01/ 2024.

- B. Li, Q. Zhou, Y. Cao, and X. Si, "Cognitively reconfigurable mimic-based heterogeneous password recovery system," Computers & Security, vol. 116, p. 102667, 2022/05/01/ 2022.

- A. Ding, G. Li, X. Yi, X. Lin, J. Li, and C. Zhang, "Generative Artificial Intelligence for Software Security Analysis: Fundamentals, Applications, and Challenges," IEEE Software, pp. 1-8, 2024.

- A. Gurtu and, D. Lim, "Chapter 101 - Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Cybersecurity," in Computer and Information Security Handbook (Fourth Edition), J. R. Vacca, Ed., ed: Morgan Kaufmann, 2025, pp. 1617-1624.

| Operation Laws | Expression |

| Addition (F1F2) | (1, 1, 1) (2, 2, 2) = (1 + 2, 1 + 2, 1 + 2) |

| Subtraction (F1F2) | (1, 1, 1) (2, 2, 2) = (1 - 2, 1 - 2, 1 - 2) |

| Multiplication (F1F2) | (1, 1, 1) (2, 2, 2) = (1 * 2, 1 * 2, 1 * 2) |

| Division (F1F2) | (1, 1, 1) (2, 2, 2) = (1 / 2, 1 / 2, 1 / 2) |

| Inverse (F1F2) | (1, 1, 1) -1 = (1, 1, 1) |

| For any real number k (Kf1) | k (1, 1, 1) = 1, 1, 1 |

| Matrix size | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| RI | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.49 |

| Human Success Factors (HSFs) | Description |

Human Security Vulnerabilities (HSVs) |

Description | ||

| HSF1: Skill and Expertise [57] | Technical Proficiency: The team must possess strong technical skills in software development, cybersecurity principles, and secure coding practices. Expertise in using security tools and technologies is also crucial. | Continuous Learning: Encourage constant learning and professional development to keep team members updated with the latest threats, vulnerabilities, and mitigation techniques. | HSV1: Lack of Security Awareness and Training [17] | Insufficient Knowledge: Developers and other team members who lack proper training in secure coding practice and Cybersecurity principles are more likely to introduce vulnerabilities into the software. | Outdated Knowledge: Not staying updated with the latest security threats, trends, and best practices can result in obsolete and insecure methods. |

| HSF2: Awareness and Mindset [17] | Security Awareness: Every team member, from developers to project managers, should know the importance of security in the SDLC. Regular training and awareness programs can help reinforce this mindset. | Security-First Mindset: Cultivating a security-first mindset means prioritizing security considerations in every phase of the SDLC. This involves integrating security practices into the development process rather than the team treating them as an afterthought. | HSV2: Poor Communication and Collaboration [58] | Miscommunication: Inadequate communication between team members, especially between developers and security experts, can lead to misunderstandings and overlooked security requirements. | Siloed Teams: Lack of collaboration between teams (development security, QA, operations) can result in incomplete security reviews and unaddressed vulnerabilities. |

| HSF3: Communication and Collaboration [58] | Effective Communication: Clear and open communication channels within the team and with stakeholders are essential. This ensures that security requirements, risks, and mitigation strategies are well understood and properly implemented. | Collaboration: Cross-functional collaboration between developers, security experts, quality assurance teams, and operations staff is crucial. Collaborative efforts help identify potential security issues early and address them efficiently. | HSV3: Inadequate Testing and Review [17] | Insufficient Security Testing: Failing to perform comprehensive security testing, such as static code analysis, dynamic testing, and penetration testing, can leave vulnerabilities undetected. | Lack of Peer Reviews: Skipping code reviews or conducting superficial reviews can allow security flaws to persist in the codebase. |

| HSF4: Leadership and Management [48] | Supportive Leadership: Leaders and managers should support and advocate for secure development practices. This includes allocating necessary resources, providing training opportunities, and emphasizing the importance of security in project goals. | Risk Management: Effective leadership involves identifying, assessing, and managing security risks throughout the project. Proactive risk management helps mitigate potential threats before they become critical issues. | HSV4: Pressure and Workload [59] | Time Constraints: Tight deadlines and high workload pressures can lead to cutting corners, skipping security checks, and hastily implementing code that may contain vulnerabilities. | Burnout: Overworked and fatigued developers are more prone to making mistakes and overlooking critical security. |

| HSF5: Process and Methodology [17] | Defined Processes: Establishing well-defined processes and methodologies for SSD, such as Secure Development Lifecycle (SDL) or DevSecOps, helps ensure that security practices are systematically followed. | Compliance and Standards: Adhering to industry standards and regulatory requirements, such as ISO/IEC 27001, NIST, or GDPR, ensures that security practices are aligned with best practices and legal obligations. | HSV5: Unclear Roles and Responsibilities [60] | Ambiguous Accountability: When security responsibilities are unclear, important security tasks may be neglected or assumed to be someone else’s responsibility. | Lack of Ownership: Without clear ownership of security tasks, there may be a lack of accountability and commitment to secure coding practices. |

| HSF6: Culture and Environment [60] | Security Culture: Building a security-centric culture within the organization promotes vigilance and accountability. A strong security culture encourages team members to identify and address security concerns proactively. | Psychological Safety: Creating an environment where team members feel safe to report security issues without fear of blame or retribution fosters openness and prompt resolution of potential vulnerabilities. | HSV6: Resistance to Change [61] | Inertia: Resistance to adopting new security tools, practices, or frameworks due to comfort with existing methods can hinder the implementation of more secure practices. | Fear of Disruption: Concerns about disrupting existing workflows or delaying projects can lead to resistance against integrating security measures into the development process. |

| HSF7: Accountability and Responsibility [62] | Clear Roles and Responsibilities: Clearly define responsibilities related to security within the team to ensure that everyone knows their part in maintaining and enhancing software security. | Ownership: Encouraging team members to take ownership of their work and its security implications leads to higher quality and more SSD outcomes. | HSV7: Insufficient Resources [63] | Limited Budget: Inadequate funding for security training, tools, and resources can prevent the adoption of necessary security measures. | Lack of Access to Expertise: Not having access to experienced security professionals for guidance and support can leave security gaps unaddressed. |

| HSF8: Resource Allocation [64] | Adequate Resources: Providing sufficient resources, including time, budget, and tools, is essential for implementing and maintaining SSD practices. | Access to Expertise: Ensuring access to security experts, whether in-house or through external consultants, helps address complex security challenges effectively. | HSV8: Human Error [65] | Coding Mistakes: Simple coding errors, such as improper input validation, hardcoded credentials, or incorrect configurations, can introduce significant vulnerabilities. | Configuration Errors: Misconfigurations in development environments, servers, and applications can create exploitable security gaps. |

| HSF9: Testing and Validation [66] | Comprehensive Testing: Regular and thorough security testing, including code reviews, penetrating testing, and vulnerability assessments, helps identify and rectify security weaknesses. | Feedback Loops: Establishing feedback loops for continuous improvement ensures that lessons learned from past projects are applied to future endeavors, enhancing overall security practices. | HSV9: Neglecting Secure Development Lifecycle [67] | Inconsistent Processes: Failing to adhere to a standardized, secure development lifecycle (SDL) can result in inconsistent application of security practices and unaddressed vulnerabilities. | Ignoring Best Practices: Not following established best practices for secure development can introduce common vulnerabilities. |

| HSF10: Incident Response and Recovery [68] | Preparedness: A well-defined incident response plan ensures the team can handle security breaches effectively. This includes identifying, responding to, and recovering from security incidents. | Learning from Incidents: Analyzing and learning from security incidents helps improve security measures and prevent future occurrences. |

HSV10: Cultural Issues [69] |

Lack of Security Culture: An organizational culture that does not prioritize security or view it as everyone’s responsibility can lead to neglect of security practices. | Blame Culture: A culture that penalizes individuals for reporting security issues can discourage team members from identifying and addressing vulnerabilities. |

|

HSF11: Scalability and Flexibility [70] |

Adaptable Integration: Ensuring that secure development practices can be integrated into various healthcare settings, from small clinics to large hospitals, and tailored to meet specific needs. | Scalable Solution: Develop solutions that can scale up to handle increased volumes of interactions and data while maintaining security standards. | HSV11: Insufficient Incident Response Preparedness [68] | Lack of Preparedness: Inadequate incident response planning and training can result in poor handling of security incidents, leading to prolonged exposure to vulnerabilities. | Failure to learn from Incident: Not analyzing and learning from past security incidents can result in recurring vulnerabilities and security breaches. |

| HSF12: Ethical and Cultural Sensitivity [69] | Ethical Considerations: Addressing ethical considerations comprehensively ensures patient confidentiality, informed consent, and equitable access to new interventions. | Cultural Sensitivity: Recognizing and respecting cultural differences in healthcare practices and patient expectations enhances acceptance and effectiveness of secure software. | HSV12: Over-Reliance and Tools [71] | Tool Dependency: Relying too heavily on automated security tools without human oversight can lead to missed vulnerabilities that require contextual understanding and manual intervention. | False Sense of Security: Assuming that using security tools alone is sufficient can lead to complacency and underestimation of the need for thorough security practices. |

| HSFs | Literature | Real-World Industries | Similarities | Differences |

| HSF1: Skill and Expertise | Emphasizes the need for technical proficiency and continuous learning | Highlights the importance of training and identifying skill gaps in practical scenarios | Both stress the importance of technical skills and ongoing education | The literature review focuses more on the ideal skill sets and continuous learning, while surveys highlight real-world skill deficiencies |

| HSF2: Awareness and Mindset | Stress the importance of security awareness and a security-first mindset throughout the SDLC. | Indicates a lack of security awareness as a common issue among practitioners | Both emphasize the critical role of awareness and mindset in ensuring security. | Literature review emphasizes theoretical importance, while surveys highlight practical shortcomings in awareness and mindset. |

| HSF3: Communication and Collaboration | Highlights the importance of clear communication and cross-functional collaboration | Identifies poor communication and collaboration as significant issues impacting security | Both recognize that effective communication and collaboration are essential for security. | The literature review discusses ideal communication strategies, while surveys focus on practical communication breakdowns. |

| HSF4: Leadership and Management | Discusses the role of supportive leadership and proactive risk management | Often highlights a lack of clear leadership and accountability in practice | Both agree on the importance of solid leadership and management in promoting security | The literature review provides theoretical frameworks for leadership, while surveys offer specific examples of leadership deficiencies |

| HSF5: Process and Methodology | Advocates for defined processes and adherence to secure development lifecycles | Points out the neglect of secure development lifecycles and methodologies in practice | Both stress the necessity of structured processes and methodologies for security. | The literature review focuses on ideal processes, while the survey highlights the practical neglect of these processes. |

| HSF6: Culture and Environment | Emphasizes the need for a security-centric culture and supportive environment | Identifies cultural issues and resistance to change as significant barriers to security | Both recognize the influence of organizational culture on security practices. | The literature review discusses theoretical and cultural frameworks, while surveys address specific organizational cultural challenges. |

| HSF7: Accountability and Responsibility | Stresses the importance of clear roles and responsibilities in maintaining security | Highlights the impact of unclear roles and responsibilities on security practices in real-world scenarios | Both emphasize the need for clear accountability to ensure security | A literature review may discuss theoretical role definition, while surveys highlight real-world ambiguities and their impact on security |

| HSF8: Resource Allocation | Discusses the need for adequate resources, including time, budget, and tools, for secure development | Identifies insufficient resources as a common issue affecting security efforts | Both stress the importance of resource allocation for maintaining security | The literature review focuses on ideal resource allocation, while surveys highlight practical |

| HSF9: Testing and Validation | Advocates for thorough security testing and validation processes throughout the development lifecycle | Points out inadequate testing and review as significant vulnerabilities in practice | Both agree on the importance of comprehensive testing and validation | Literature review details ideal testing methodologies, while surveys reveal practical deficiencies in testing and validation efforts |

| HSF10: Incident Response and Recovery | Emphasizes the need for preparedness and learning from security incidents to improve future responses | Highlights insufficient incident response preparedness and real-world challenges in handling incidents | Both stress the importance of having robust incident response and recovery plans. | The literature review discusses theoretical incident response plans, while surveys highlight practical gaps and challenges in preparedness. |

| HSF11: Scalability and Flexibility | Discuss the need for adaptable and scalable security solutions that can grow with the organization. | Often implied in resource allocation and process flexibility but not always explicitly addressed. | Both recognize the need for scalability and flexibility in security practices. | The literature review explicitly addresses scalability and flexibility, while the survey focuses more on immediate practical concerns. |

| HSF12: Ethical and Cultural Sensitivity | Highlights the importance of ethical considerations and cultural sensitivity in SSD | Often implied in broader cultural issues and security awareness but not always explicitly addressed. | Both touch upon the importance of considering ethical and cultural factors in security practices | Literature review explicitly addresses ethical and cultural frameworks, while surveys focus on immediate practical concerns. |

| HSVs | Literature | Real-World Industries | Similarities | Differences |

| HSV1: Lack of Security Awareness and Training | Emphasizes the importance of continuous education and awareness programs | Highlights frequent security breaches due to sufficient knowledge | Both stress the need for awareness and training in security practices | Literature focuses on theoretical frameworks, while the real world highlights practical training gaps |

| HSV2: Poor Communication and Collaboration | Academic studies underline the importance of clear communication and collaboration. | Industries experience issues where a lack of collaboration leads to security gaps | Both recognize the importance of effective communication and collaboration | Literature provides ideal communication strategies, while the real world highlights practical communication issues |

| HSV3: Inadequate Testing and Review | Security vulnerabilities often arise from inadequate testing and review processes. | Time constraints and resource limitations result in rushed or incomplete testing. | Both stress the importance of comprehensive testing and validation | Literature details ideal testing methodologies, while the real world highlights practical deficiencies of testing efforts |

| HSV4: Unclear Roles and Responsibilities | Research identifies the need for clearly defined roles and responsibilities to avoid security issues. | Unclear responsibilities can lead to essential security tasks being overlooked or improperly executed. | Both agree on the importance of clearly defined roles and responsibilities in promoting security. | Literature provides theoretical frameworks for roles, while the real world highlights practical issues related to unclear roles. |

| HSV5: Insufficient Resources | Emphasizes the need for adequate resources, including budget, tools, and personnel | Budget constraints often lead to prioritizing other operational needs over security investments. | Both stress the importance of resource allocation for security | Literature focuses on ideal resource allocation, while the real world highlights practical resource constraints |

| HSV6: Human Error | Academic work acknowledges human error as a critical factor in security breaches. | Human error is a common cause of security incidents in industry reports | Both agree on the importance of addressing human error in security practices | Literature provides theoretical approaches, while the real world highlights practical human error issues |

| HSV7: Pressure and Workload | Less commonly highlighted compared to other vulnerabilities | High pressure and workload are frequently cited as major contributors to security lapses | Both recognize the impact of workload on security practices | Literature rarely addresses this as a standalone factor, while the world highlights it as a significant practical issue |

| HSV8: Resistance to Change | They are often discussed in a more theoretical context. | They are frequently a barrier to implementing new security measures and protocols. | Both acknowledge that resistance to change can impede security improvements. | The literature discusses it theoretically, while the world focuses on practical resistance issues. |

| HSV9: Neglecting Secure Software Development Lifecycle | Stresses the importance of incorporating security throughout the development lifecycle | They are often neglected due to cost, time constraints, or lack of immediate perceived benefits. | Both emphasize the necessity of including security in every development lifecycle phase. | Literature focuses on ideal processes, while the world highlights the practical neglect of secure development practices. |

| HSV10: Cultural Issues | Emphasizes the importance of a security-centric culture within organizations | Struggles to integrate security into core values and daily practices | Both recognize the influence of organizational culture on security practices | Literature provides theoretical and cultural frameworks, while the real world addresses specific cultural challenge |

| HSV11: Over-Reliance on Tools | Advocates for a balanced approach combining tools with human oversight | Often places excessive reliance on automated tools, underestimating the need for human judgment | Both highlight the risks of relying solely on automated tools for security | Literature focuses on balanced approaches, while the world highlights practical issues due to over-reliance on tools |

| Human Success Factors (HSFs) | Literature Review Impact % |

Empirical Survey Impact % | Human Security Vulnerabilities (HSVs) | Literature Review Impact % |

Impact Percentage |

| HSF1 | 94 | 90 | HSV1 | 90 | 91 |

| HSF2 | 91 | 85 | HSV2 | 89 | 85 |

| HSF3 | 86 | 81 | HSV3 | 78 | 84 |

| HSF4 | 82 | 79 | HSV4 | 75 | 82 |

| HSF5 | 79 | 78 | HSV5 | 69 | 78 |

| HSF6 | 78 | 76 | HSV6 | 68 | 66 |

| HSF7 | 75 | 73 | HSV7 | 64 | 60 |

| HSF8 | 73 | 72 | HSV8 | 56 | 59 |

| HSF9 | 71 | 70 | HSV9 | 50 | 52 |

| HSF10 | 63 | 60 | HSV10 | 47 | 49 |

| HSF11 | 60 | 52 | HSV11 | 45 | 43 |

| HSF12 | 55 | 50 | HSV12 | 44 | 40 |

| Practices for Addressing Human Success Factors | Sub-Practices | ||

| Security Training and Awareness |

Regular Training: Provide ongoing security training to update the development team on the latest threats, secure coding practices, and regulatory requirements. |

Security Champions: Identify and empower security champions within the team to advocate for and enforce security best practices. |

Awareness Campaigns: Run regular security awareness campaigns to reinforce the importance of security in the development lifecycle. |

| Collaborative Culture |

Team Collaboration: Foster a culture of collaboration where security is a shared responsibility across all team members, including developers, testers, and operations. |

Cross-Functional Teams: Encourage forming cross-functional teams that include security experts to integrate security considerations into all stages of development. |

Knowledge Sharing: Promote knowledge sharing through internal workshops, seminars, and collaborative tools. |

| Leadership and Management Support |

Executive Support: Ensure strong support from leadership to prioritize security and allocate necessary resources. |

Clear Vision: Communicate a clear vision and strategy for integrating security into the software development process. |

Empowerment: Empower team members to take ownership of security practices and make decisions that enhance security. |

| Effective Communication |

Open Channels: Establish open and effective communication channels to discuss security concerns and share updates. |

Regular Meetings: Hold regular security-focused meetings to review potential vulnerabilities, share best practices, and update the team on new security threats. |

Feedback Mechanisms: Implement feedback mechanisms to gather input from team members on security practices and improvement areas. |

| Skill Development |

Continuous Learning: Encourage continuous learning and professional development in security through certifications, courses, and conferences. |

Mentorship Programs: Implement mentorship programs where experienced security professionals guide less experienced team members. |

Hands-On Practice: Provide opportunities for hands-on practice with secure coding, threat modeling, and penetration testing. |

| User-Centric Security |

User Involvement: To understand their security concerns and expectations, involve end-users early in the development process. |

User Feedback: Collect and act on user feedback regarding security features and usability. |

Usability Testing: Conduct usability testing focusing on security features to ensure they are user-friendly and effective. |

| Agile and DevSecOps Practices |

Agile Security Integration: Integrate security practices into Agile workflows to ensure continuous attention to security. |

DevSecOps: Adopt DevSecOps practices to automate security testing and integrate security into the CI/CD pipeline. |

Security Retrospectives: Conduct regular security retrospectives to review security incidents, identify lessons learned, and plan improvements. |

| Clear Roles and Responsibilities |

Defined Roles: Clearly define roles and responsibilities related to security within the development team. |

Role Flexibility: Allow role flexibility to adapt to changing security needs and leverage team members’ strengths. |

Accountability: Ensure accountability for security practices and outcomes across all team members. |

| Stakeholder Engagement |

Stakeholder Communication: Maintain regular communication with stakeholders to inform them about security measures and risks. |

Expectation Management: Manage stakeholder expectations by being transparent about security risks and the measures in place to address them. |

Stakeholder Involvement: Involve stakeholders in security planning and decision-making processes. |

| Risk Management |

Risk Identification: Proactively identify potential security risks that could impact the project. |

Mitigation Strategies: Develop and implement risk mitigation strategies to address identified security risks. |

Incident Response Plans: Have incident response plans to address security breaches and quickly minimize impact. |

| Continuous Improvement |

Performance Metrics: Use security performance metrics to assess security practices' effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. |

Process Optimization: Continuously optimize security processes based on feedback and performance data. |

Innovation Encouragement: Encourage innovation in security practices and use new tools and techniques to enhance security. |

| Practices for Addressing Human Security Vulnerabilities | Sub-Practices | ||

| Comprehensive Security Training and Awareness |

Regular Training: Conduct regular training sessions to inform the development team about the latest security threats, secure coding practices, and compliance requirements. |

Phishing Simulations: Implement phishing simulations to educate employees on recognizing and responding to phishing attacks. |

Security Certifications: Encourage team members to obtain security certifications such as CISSP, CEH, or CSSLP. |

| Security Culture and Leadership |

Security Champions: Designate security champions within development teams to promote security best practices and act as liaisons with the security team. |

Leadership Commitment: Ensure that leadership demonstrates a commitment to security by prioritizing it in all aspects of the project. |

Reward and Recognition: Recognize and reward team members who contribute to improving security within the project. |

| Effective Communication and Collaboration |

Clear Communication Channels: Establish clear communication channels for reporting security issues and sharing security-related information |

Cross-Functional Teams: Create cross-functional teams with security experts to integrate security considerations throughout the development lifecycle. |

Regular Security Briefings: Hold regular security briefings to update the team on new threats and security incidents. |

| Access Control and Least Privilege |

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Implement RBAC to ensure that team members have access only to the resources they need to perform their jobs. |

Least Privilege Principle: Apply the principle of least privilege to minimize the potential impact of security breaches, |

Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): Use MFA to add extra security to critical systems and applications. |

| Secure Development Practices |

Secure Coding Standards: Adopt and enforce secure coding standards (e.g., OWASP Secure Coding Practices) to prevent common vulnerabilities. |

Code Review: Regular code reviews should focus on security to identify and address vulnerabilities early. |

Static and Dynamic Analysis: Use static and dynamic analysis tools to detect security issues in the code. |

| Incident Response and Management |

Incident Response Plan: Develop and maintain an incident response plan to quickly and effectively address security incidents. |

Simulation Drills: Conduct regular incident response drills to ensure the team is prepared to handle security breaches. |

Post-Incident Analysis: Perform post-incident analysis to learn from security incidents and improve future responses. |

| Continuous Monitoring and Testing |

Vulnerability Scanning: Implement regular vulnerability scanning to identify and address security weaknesses. |

Penetration Testing: Conduct penetration testing to simulate attacks and evaluate the effectiveness of security measures. |

Security Audits: Perform regular security audits to ensure compliance with security policies and standards. |

| Data Protection and Privacy |

Encryption: Use encryption to protect sensitive data both at rest and in transit. |

Data Minimization: Collect and retain only the data necessary for the project to reduce the risk of data breaches. |

Privacy by Design: Incorporate privacy considerations into the design and development of software to protect user data. |

| Supply Chain Security |

Third-Party Risk Management: Assess and manage the security risks associated with third-party vendors and partners. |

Secure Supply Chain: Implement security measures to protect the software supply chain, including code signing and verification. |

Contractual Security Requirement: Include security requirements in contracts with third-party vendors to ensure they adhere to security best practices. |

| User Education and Support |

Security Awareness for Users: Educate users about security best practices and how to recognize potential threats. |

User-Friendly Security Features: Design security features that are user-friendly and encourage proper security behaviors. |

Support Channels: Provide clear support channels for users to report security concerns and get help with security-related issues. |

| Regulatory Compliance and Standards |

Compliance Programs: Establish compliance programs to adhere to relevant security regulations and standards (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA). |

Regular Audits: Conduct regular audits to ensure ongoing compliance with security regulations and standards. |

Documentation: Maintain thorough documentation of security policies, procedures, and compliance efforts. |

| HSFs and HSVs: Practices Categories | HSFs and HSVs: Practices Subcategories |

| C1: Security Training and Awareness | P1: Regular Training and Phishing Simulations P2: Security and Awareness Campaigns P3: Security Certifications and Support Channels P4: User-Friendly Security Features |

| C2: Collaborative Security Culture and Leadership | P5: Team Collaboration and Cross-Functional Teams P6: Knowledge Sharing and Executive Support P7: Leadership Commitment P8: Reward and Recognition P9: Clear Vision and Empowerment |

| C3: Effective Communication and Collaboration | P10: Open Channels and Regular Meetings P11: Feedback Mechanisms P12: Clear Communication Channels P13: Regular Security Briefings |

| C4: Skill Development and Stakeholder Engagement | P14: Continuous Learning and Mentorship Programs P15: Hands-On Practice and Stakeholder Communication P16: Expectation Management and Stakeholder Involvement |

| C5: Agile and DevSecOps Practices | P17: Agile Security Integration and DevSecOps P18: Security Retrospectives P19: Secure Coding Standards P20: Code Review, Static and Dynamic Analysis |

| C6: User-Centric Security, Clear Roles and Responsibilities | P21: Defined Roles and Role Flexibility P22: Accountability and Usability Testing P23: User Involvement and User Feedback |

| C7: Supply Chain Security and Risk Management | P24: Risk Identification and Mitigation Strategies P25: Incident Response Plans and Post-Incident Analysis P26: Simulation Drills P27: Third-Party Risk Management P28: Secure Supply Chain and Contractual Security |

| C8: Continuous Improvement, Monitoring and Testing | P29: Performance Metrics and Process Optimization P30: Innovation Encouragement and Compliance Programs P31: Vulnerability Scanning and Penetration Testing P32: Security and Regular Audits P33: Documentation |

| C9: Data Protection and Privacy, Access Control and Least Privilege | P34: Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) P35: Least Privilege Principle P36: Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) P37: Encryption and Data Minimization P38: Privacy by Design |

|

| Categories | C-1 | C-2 | C-3 | C-4 | C-5 | C-6 | C-7 | C-8 | C-9 | Sum | Sum * Inverse of the total sum of the columns |

| C-1 | (1, 1, 1) | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (5.1, 7.7, 12.1) | (0.0392, 0.0893, 0.2008) |

| C-2 | (1.5, 2, 2.5) | (1, 1, 1) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (7.4, 9.7, 13.1) | (0.0569, 0.1125, 0.2174) |

| C-3 | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (1.5, 2, 2.5) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (1.5, 2, 2.5) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (7.8, 11.5, 17) | (0.0600, 0.1334, 0.2822) |

| C-4 | (0.6, 1, 2) | (1.5, 2, 2.5) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (1, 1, 1) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (1.5, 2, 2.5) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (7.1, 10.6, 15) | (0.0546, 0.1229, 0.2490) |

| C-5 | (1, 1.5, 2) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (1, 1, 1) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | (5.7, 8.1, 16.2) | (0.0438, 0.0939, 0.2689) |

| C-6 | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (1.5, 2, 2.5) | (7.1, 10.1, 14.6) | (0.0546, 0.1171, 0.2423) |

| C-7 | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (1, 1, 1) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (6.2, 8.8, 13.5) | (0.0477, 0.1020, 0.2241) |

| C-8 | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (6.5, 9.6, 13.6) | (0.0500, 0.1113, 0.2257) |

| C-9 | (1, 1.5, 2) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (0.5, 1, 1.5) | (0.6, 1, 2) | (1.5, 2, 2.5) | (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | (1, 1.5, 2) | (0.5, 0.6, 1) | (1, 1, 1) | (7, 9.7, 13.6) | (0.0539, 0.1125, 0.2257) |

| The total sum of the columns | (59.9, 85.8, 128.7) | ||||||||||

| The inverse of the total sum of the columns | (0.0077, 0.0116, 0.0166) | ||||||||||

| Categories | C-1 | C-2 | C-3 | C-4 | C-5 | C-6 | C-7 | C-8 | C-9 |

| C-1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.61 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.61 |

| C-2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 1.5 |

| C-3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.61 |

| C-4 | 1 | 2 | 0.61 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| C-5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.5 |

| C-6 | 1 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 |

| C-7 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.61 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.61 |

| C-8 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.61 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.5 |

| C-9 | 1.5 | 0.61 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.61 | 1 |

| Sum | 11 | 9.72 | 7.61 | 8.5 | 11.11 | 9.2 | 9.72 | 9.33 | 9.32 |

| Categories | Sum * Inverse of the total sum of the columns | C-1 | C-2 | C-3 | C-4 | C-5 | C-6 | C-7 | C-8 | C-9 | Priority Weight |

| V (C1≥…) | (0.0392, 0.0893, 0.2008) (l1, m1, u1) |

- | 0.6625 | 0.5991 | 0.6359 | 0.7416 | 0.6523 | 0.7091 | 0.6765 | 0.6671 | 0.5991 |

| V (C2≥…) | (0.0569, 0.1125, 0.2174) (l2, m2, u2) |

1 | - | 0.8827 | 0.9399 | 1 | 0.9725 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.8827 |

| V (C3≥…) | (0.0600, 0.1334, 0.2822) (l3, m3, u3) |

1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| V (C4≥…) | (0.0546, 0.1229, 0.2490) (l4, m4, u4) |

1 | 1 | 0.9473 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.9473 |

| V (C5≥…) | (0.0438, 0.0939, 0.2689) (l5, m5, u5) |

1 | 0.9193 | 0.8409 | 0.8808 | - | 0.9023 | 0.9646 | 0.9263 | 0.9203 | 0.8409 |

| V (C6≥…) | (0.0546, 0.1171, 0.2423) (l6, m6, u6) |

1 | 1 | 0.9179 | 0.9700 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.9179 |

| V (C7≥…) | (0.0477, 0.1020, 0.2241) (l7, m7, u7) |

1 | 0.9409 | 0.8393 | 0.8902 | 1 | 0.9182 | - | 0.9492 | 0.9418 | 0.8393 |

| V (C8≥…) | (0.0500, 0.1113, 0.2257) (l8, m8, u8) |

1 | 0.9929 | 0.8823 | 0.9365 | 1 | 0.9672 | 1 | - | 0.9930 | 0.8823 |

| V (C9≥…) | (0.0539, 0.1125, 0.2257) (l9, m9, u9) |

1 | 1 | 0.8879 | 0.9427 | 1 | 0.9738 | 1 | 1 | - | 0.8879 |

| Categories | C-1 | C-2 | C-3 | C-4 | C-5 | C-6 | C-7 | C-8 | C-9 | W |

| C-1 | 0.09090 | 0.05144 | 0.13140 | 0.11764 | 0.05490 | 0.10869 | 0.10288 | 0.10718 | 0.06545 | 0.09227 |

| C-2 | 0.18181 | 0.10288 | 0.13140 | 0.05882 | 0.09000 | 0.16304 | 0.06275 | 0.06538 | 0.16094 | 0.11300 |

| C-3 | 0.09090 | 0.10288 | 0.13140 | 0.05882 | 0.18001 | 0.10869 | 0.10288 | 0.21436 | 0.06545 | 0.11726 |