Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

09 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

2.1. Kinzigite Formation

2.2. Mafic Complex

2.3. Ultramafic Massifs

3. Methods

4. Results

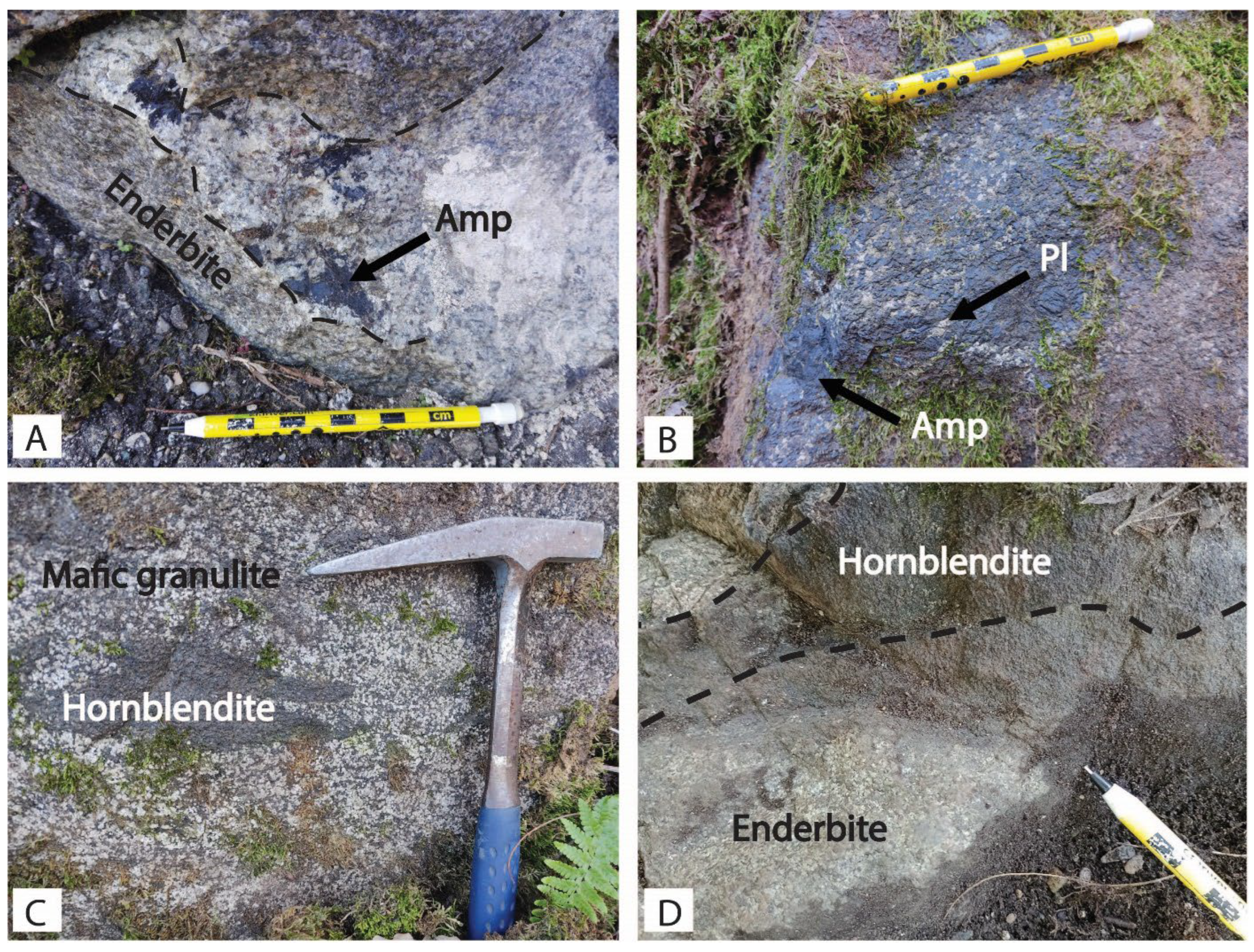

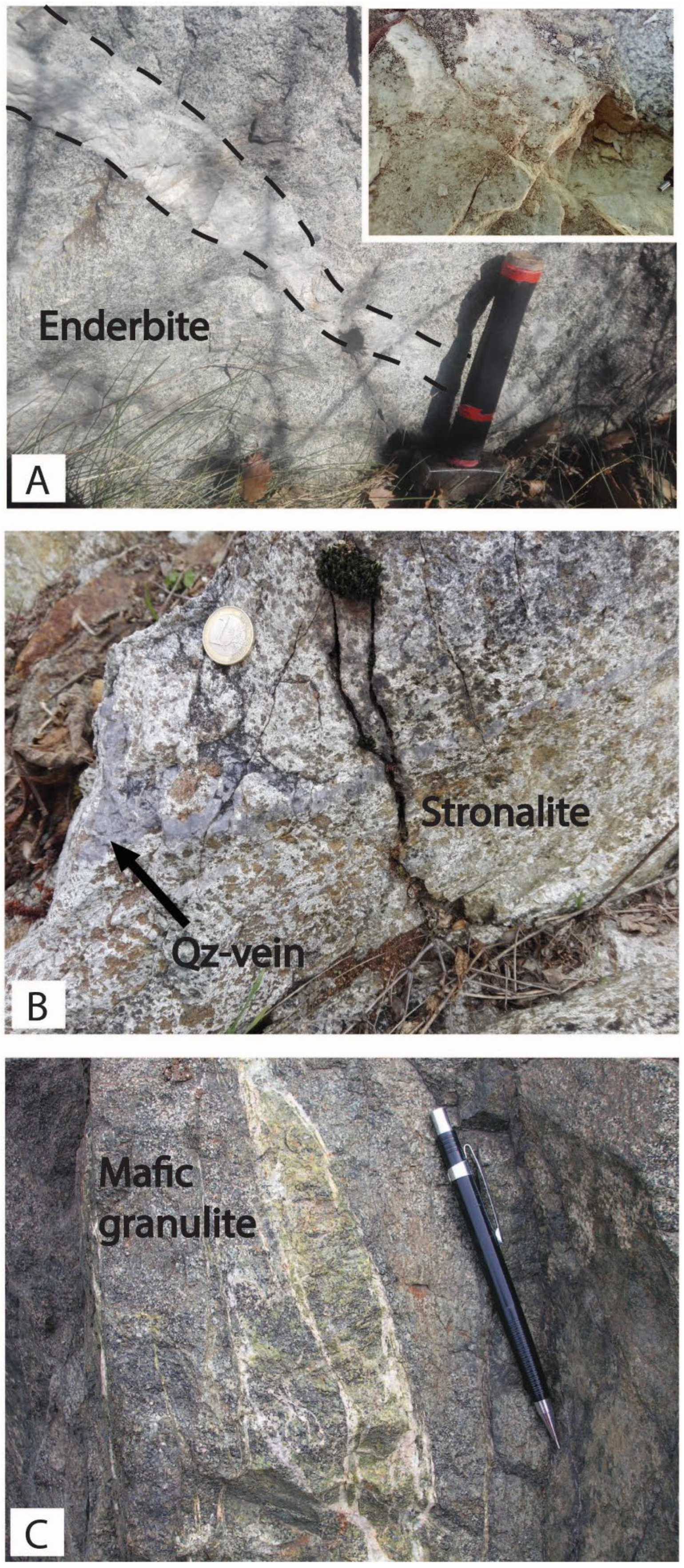

4.1. Field Evidence

4.1.1. Mafic Granulites

4.1.2. Enderbites

4.1.3. Amp-Rich Dykes, Pods, and Lenses

4.1.4. Quartz-Feldspathic Dykes

4.1.5. Stronalites

4.1.6. Alpine Overprint

4.2. Petrography, Mineral Chemistry and Thermobarometry

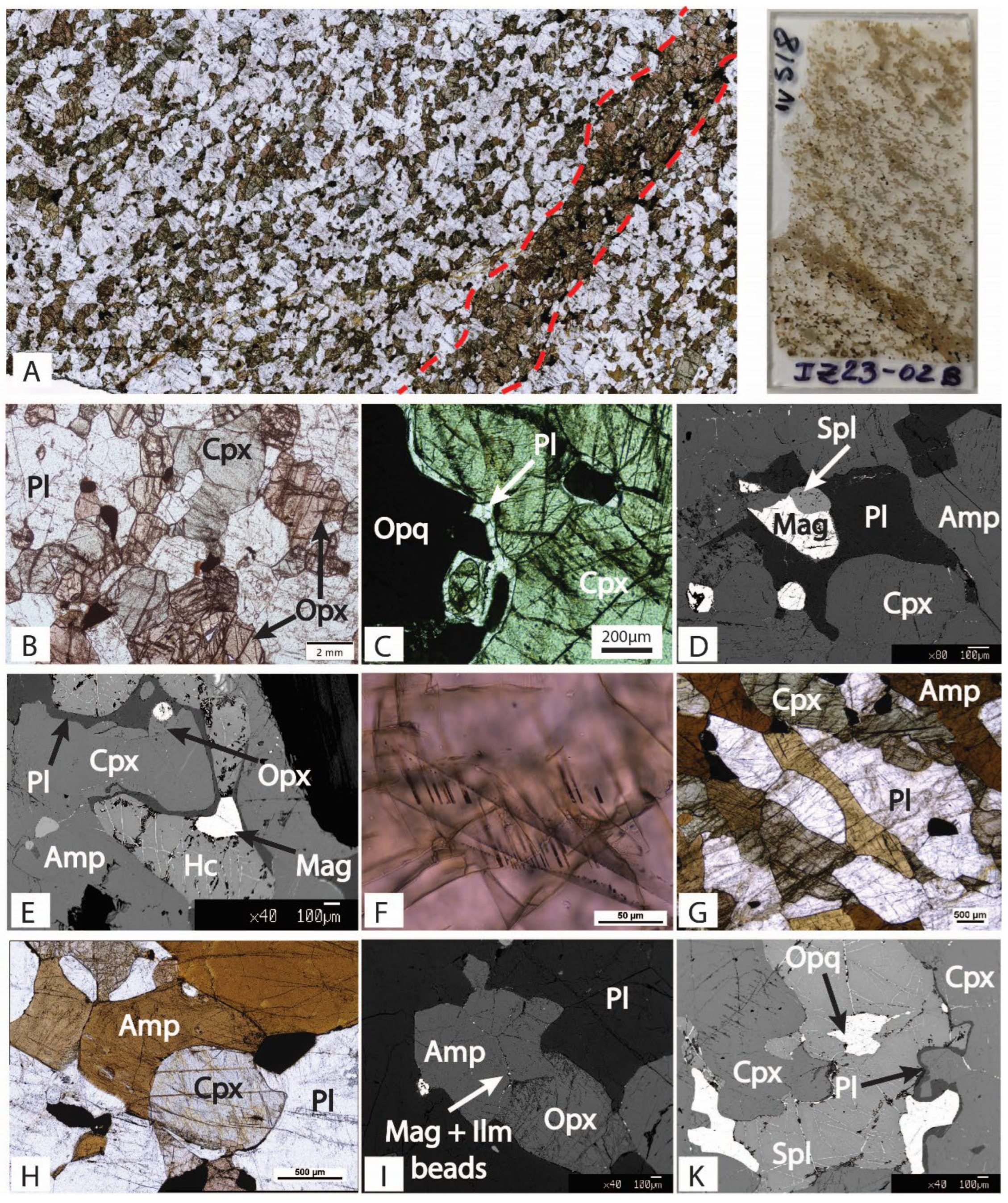

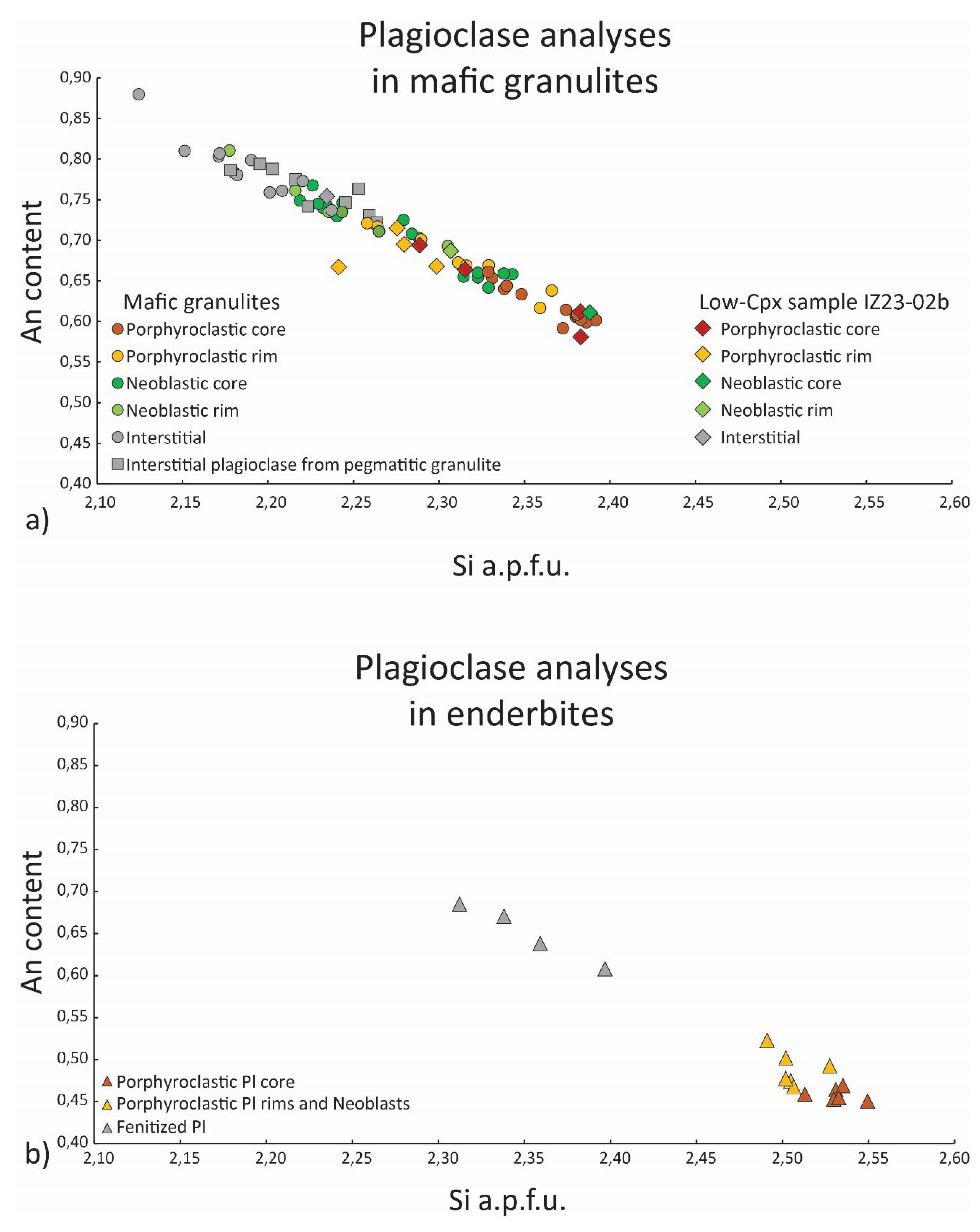

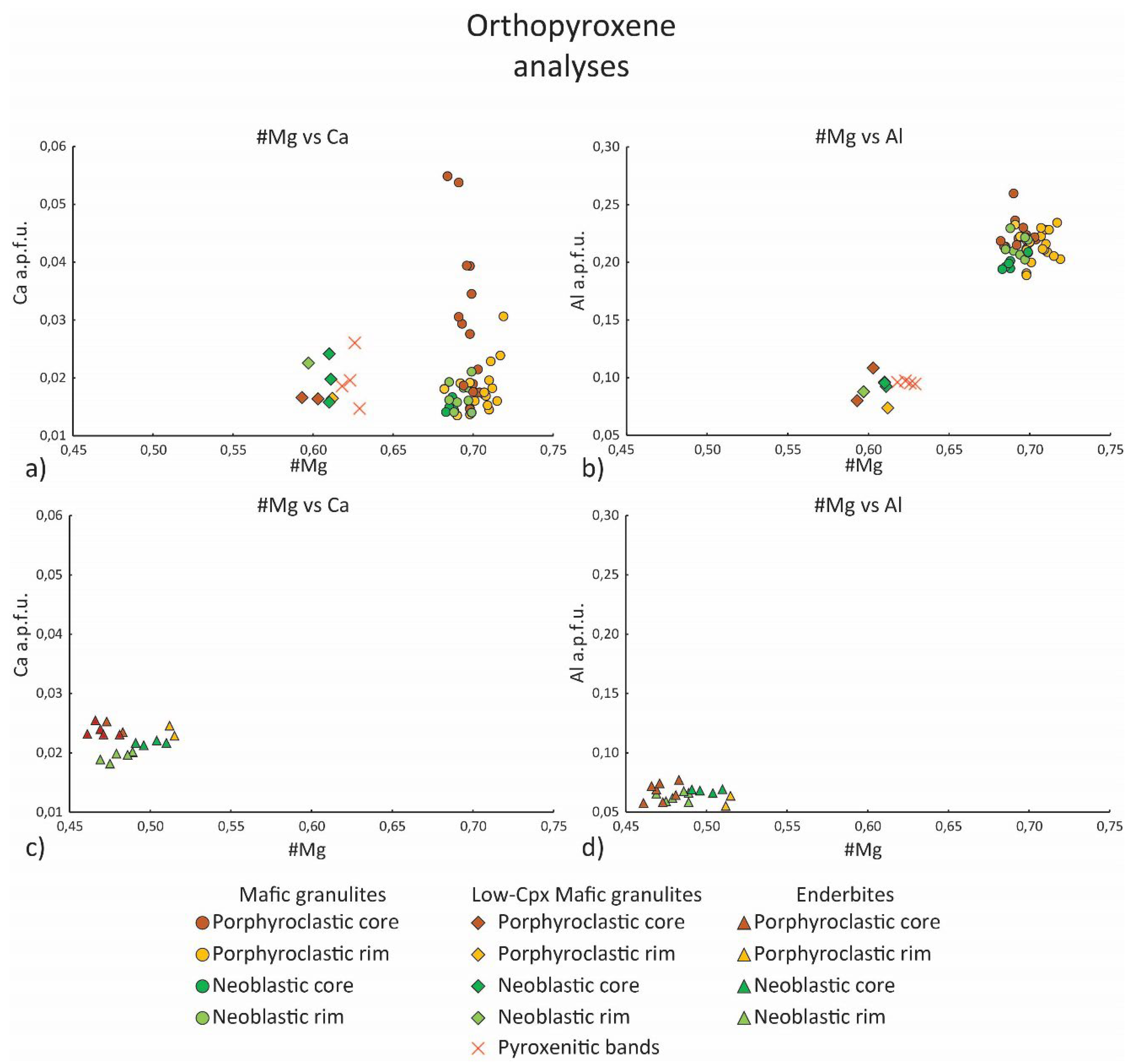

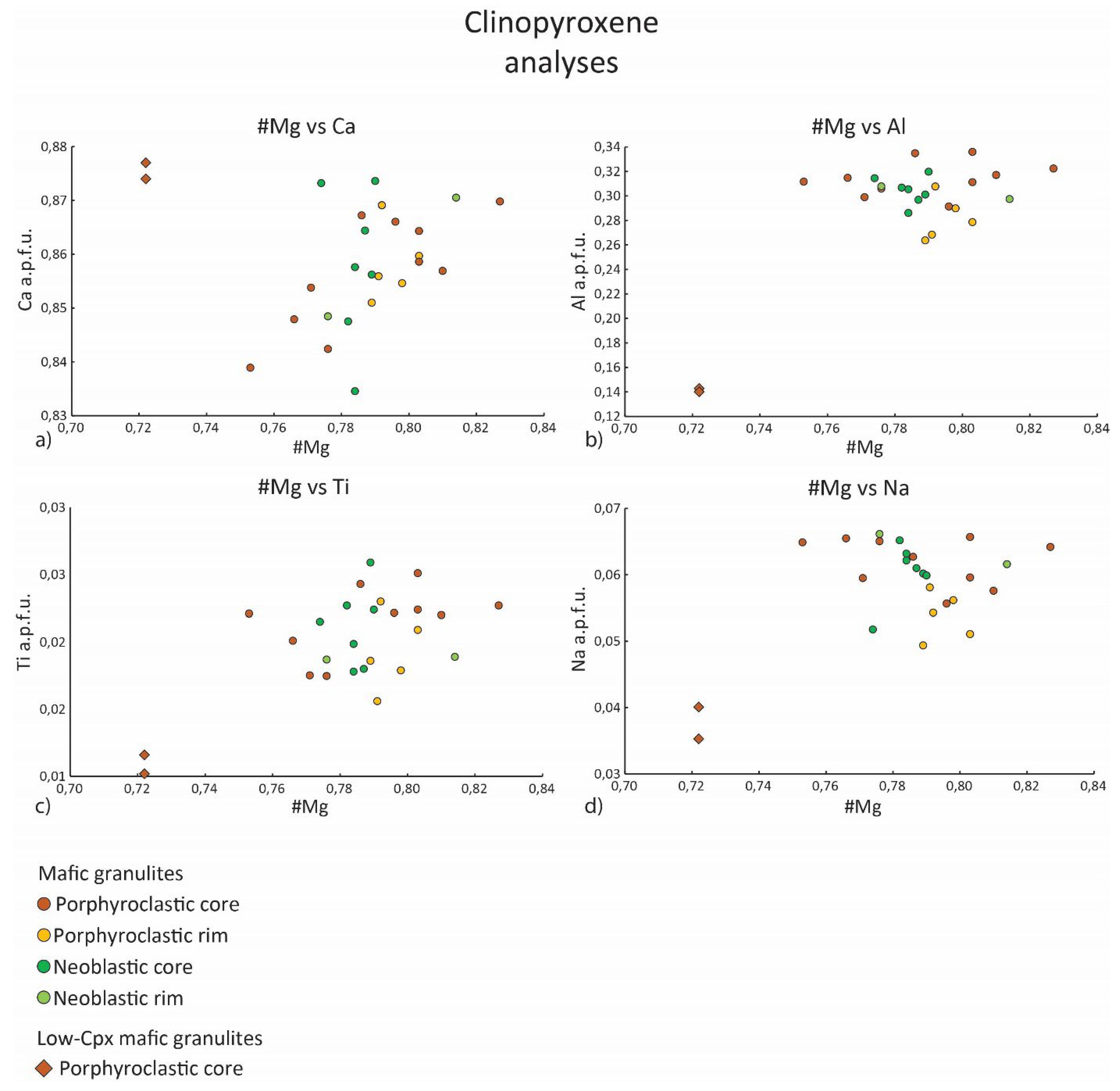

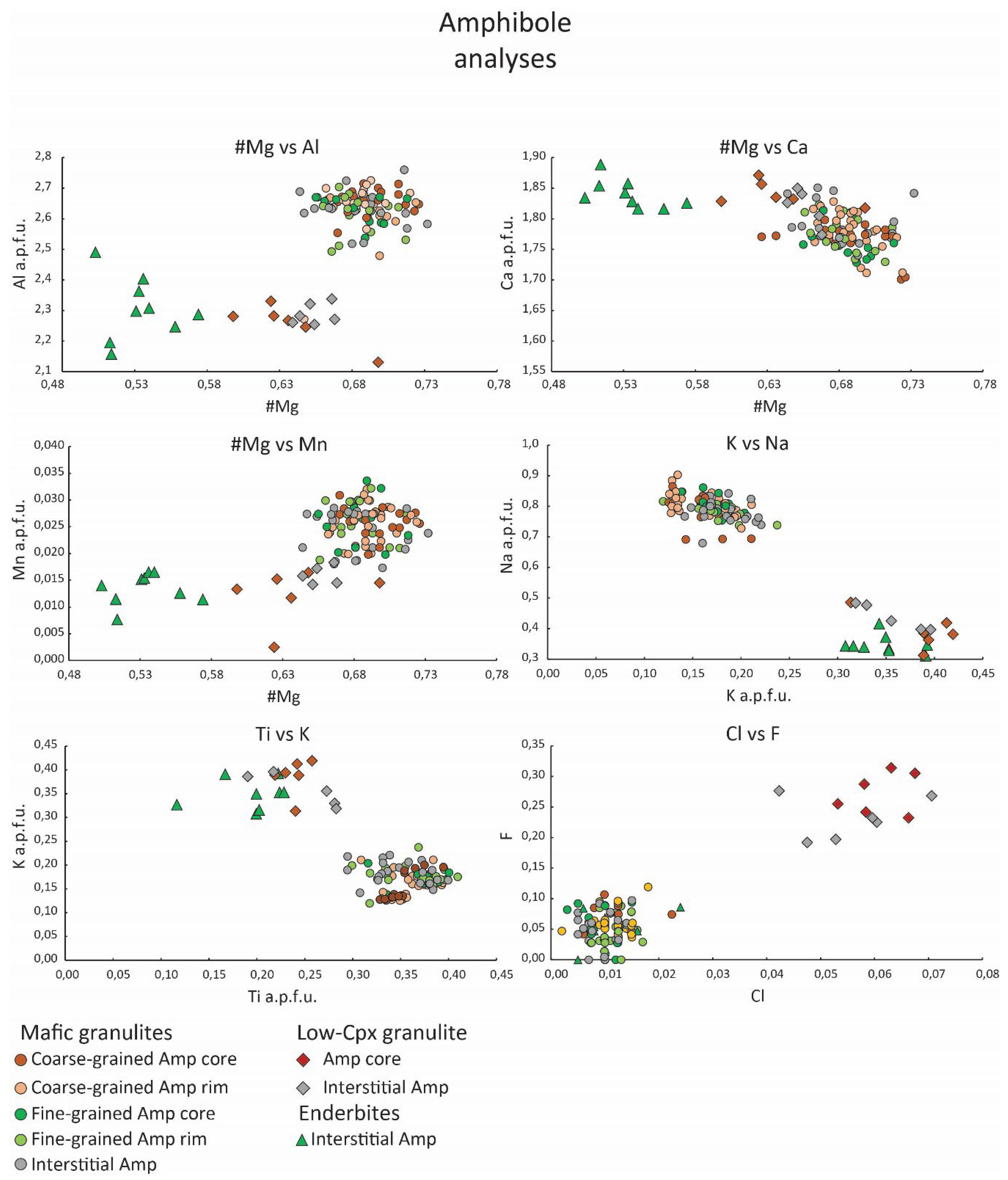

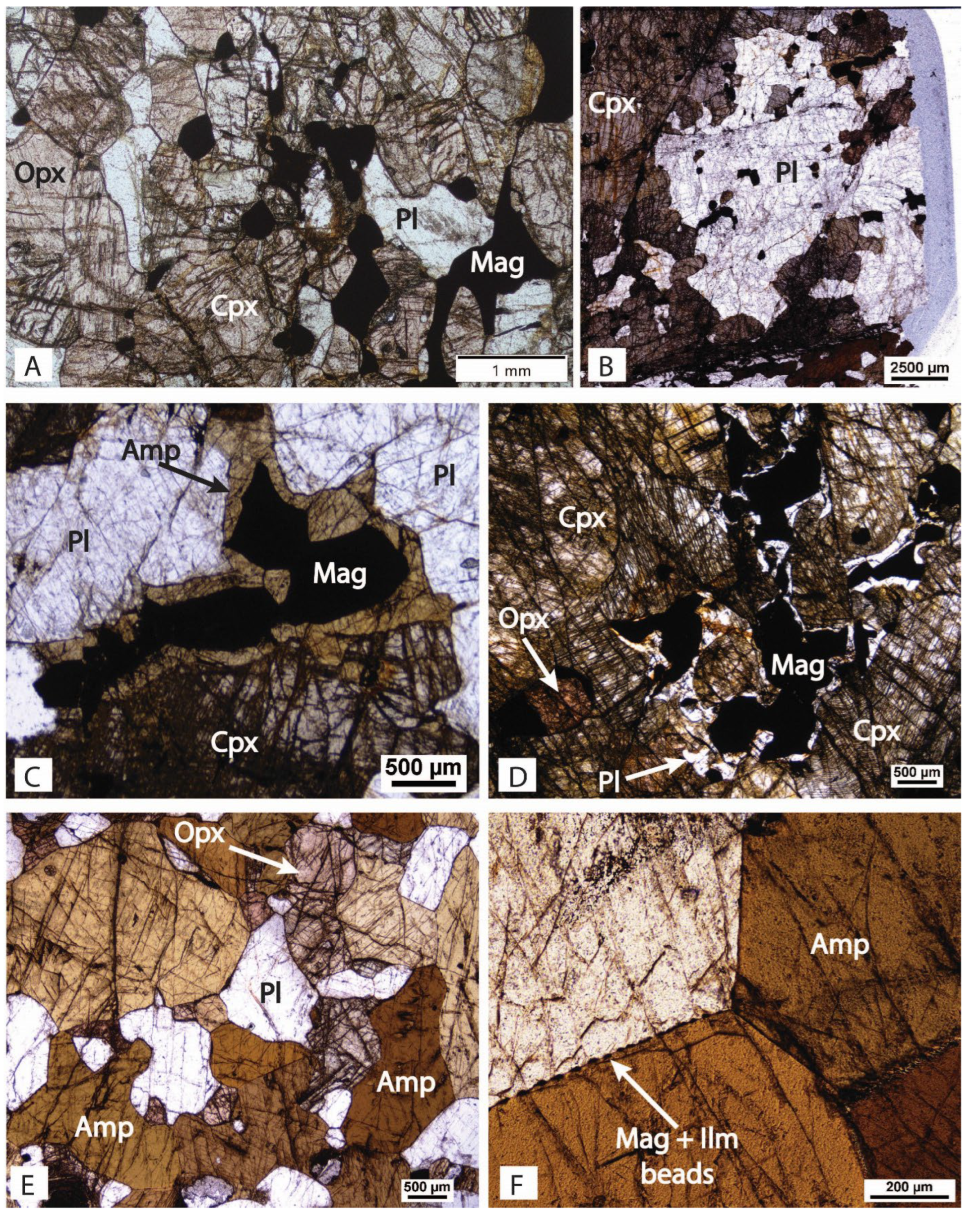

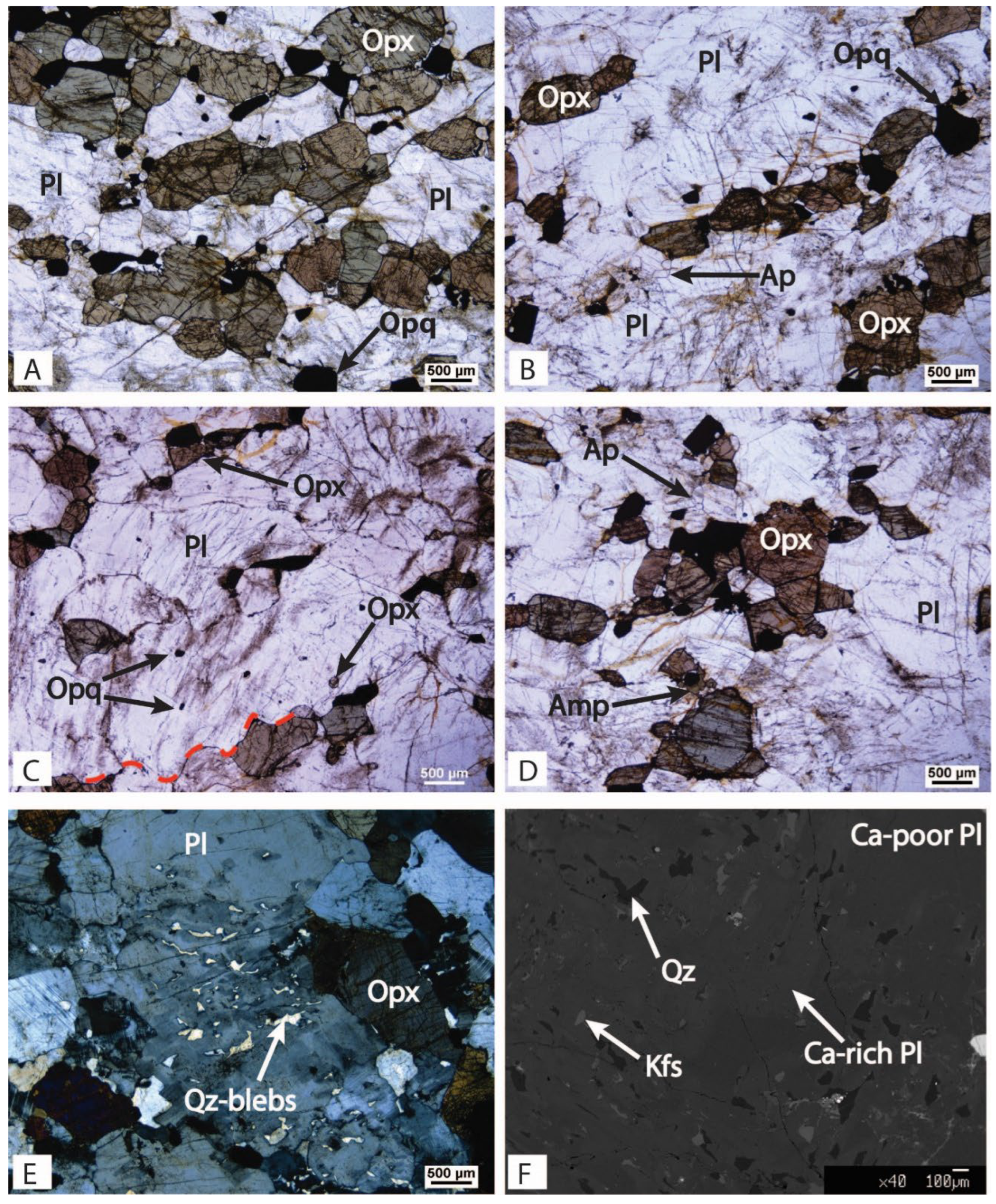

4.2.1. Mafic Lithologies

4.2.2. Enderbites

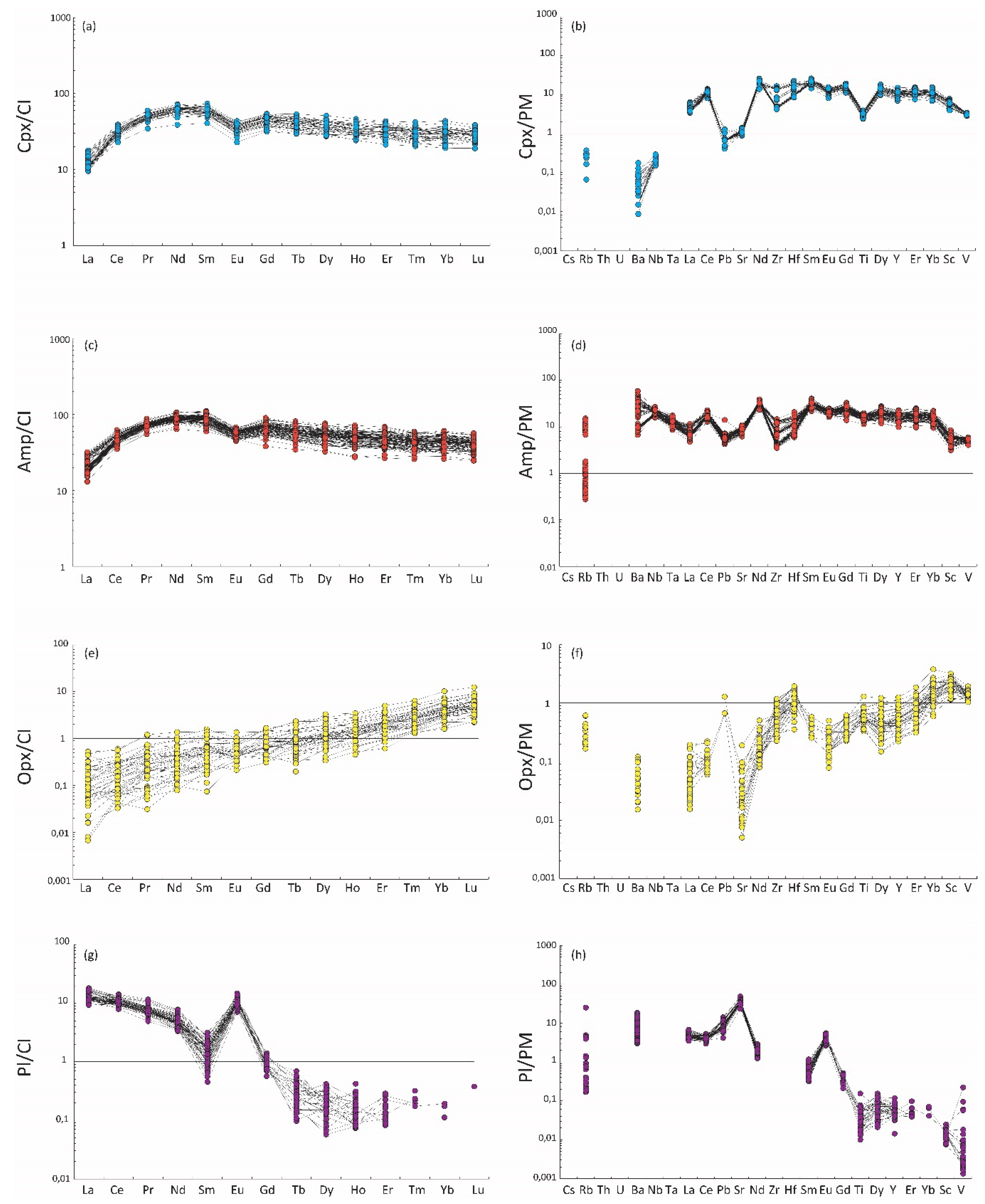

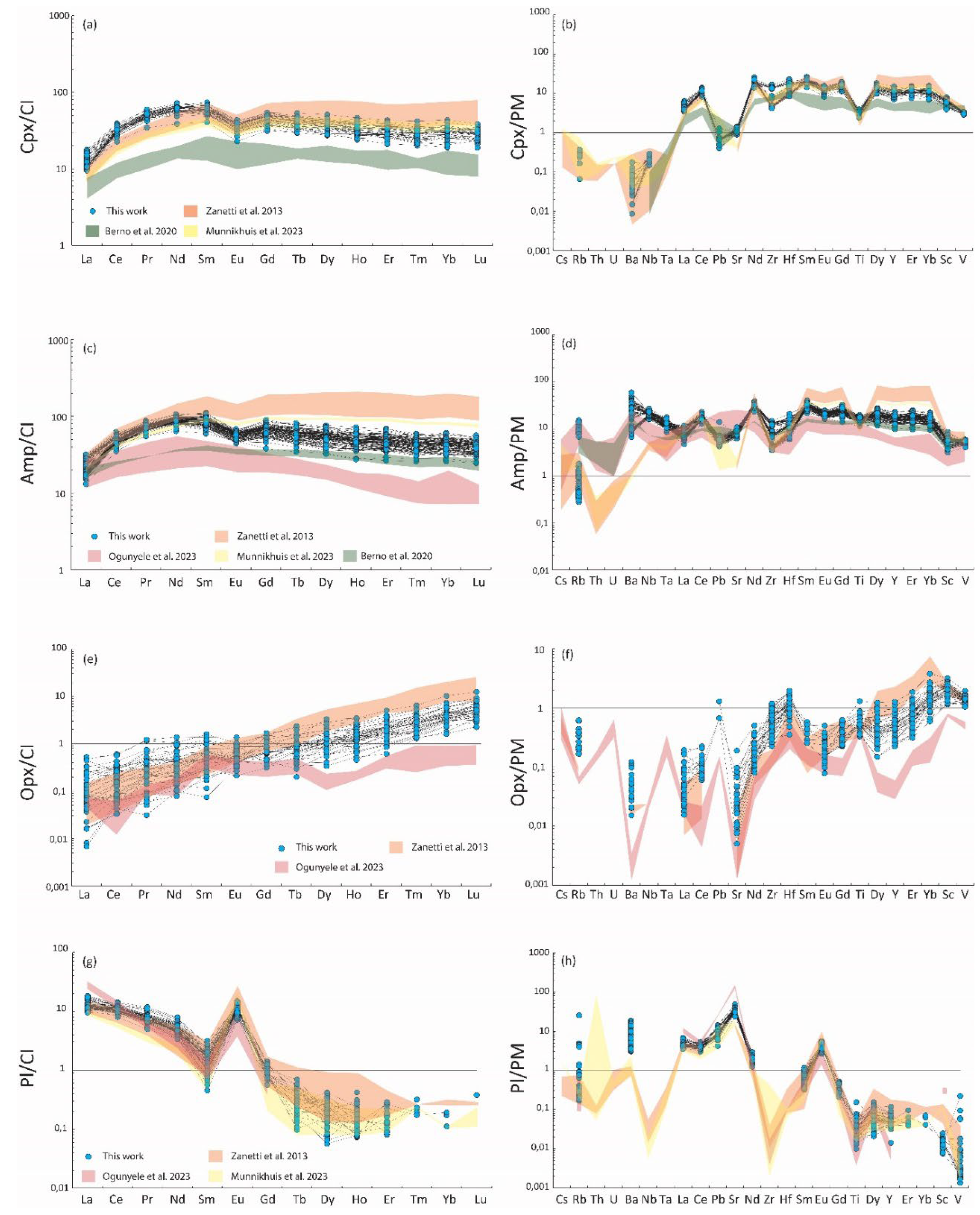

4.2.3. Mineral Trace Element Composition in Mafic Lithologies

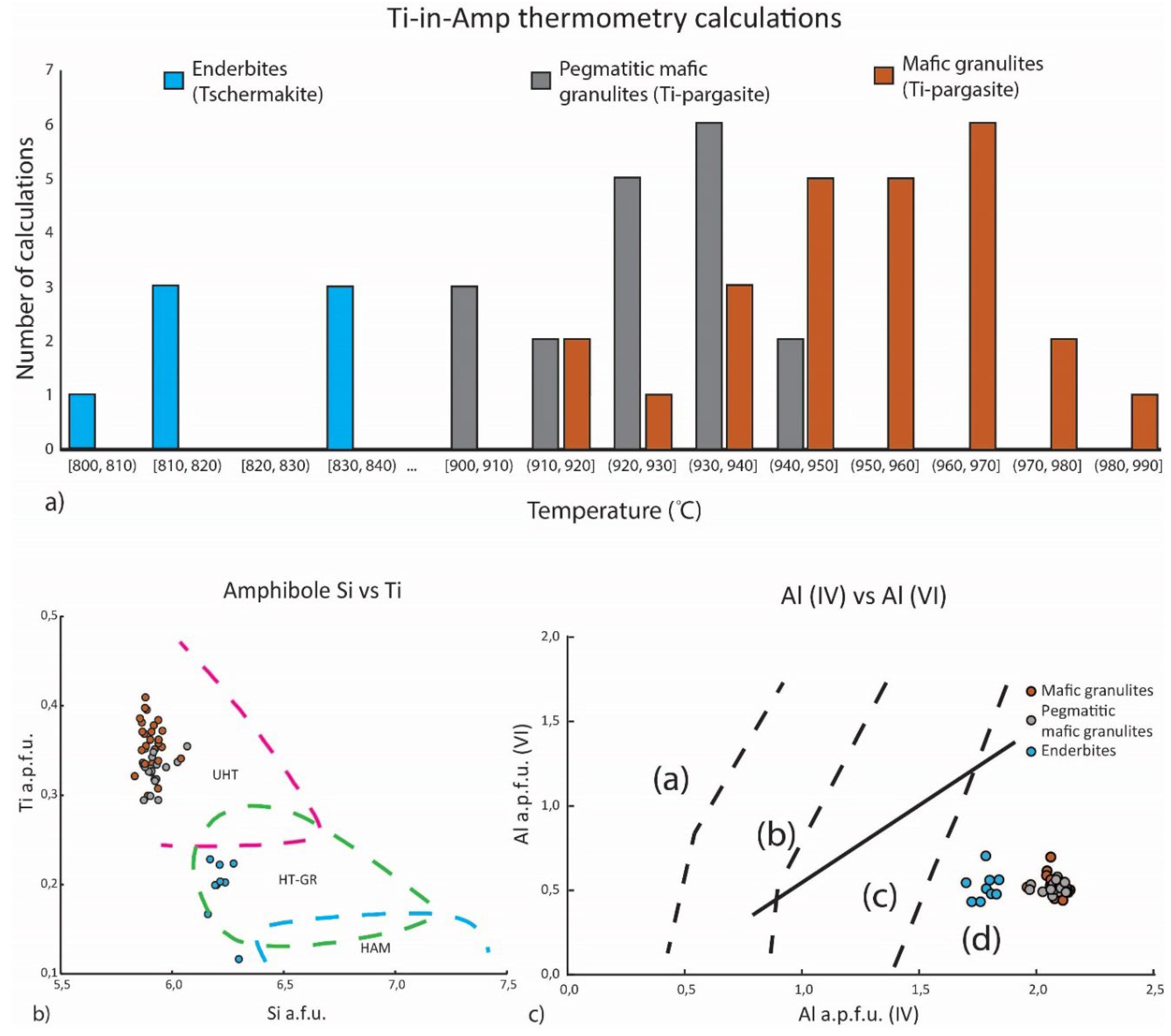

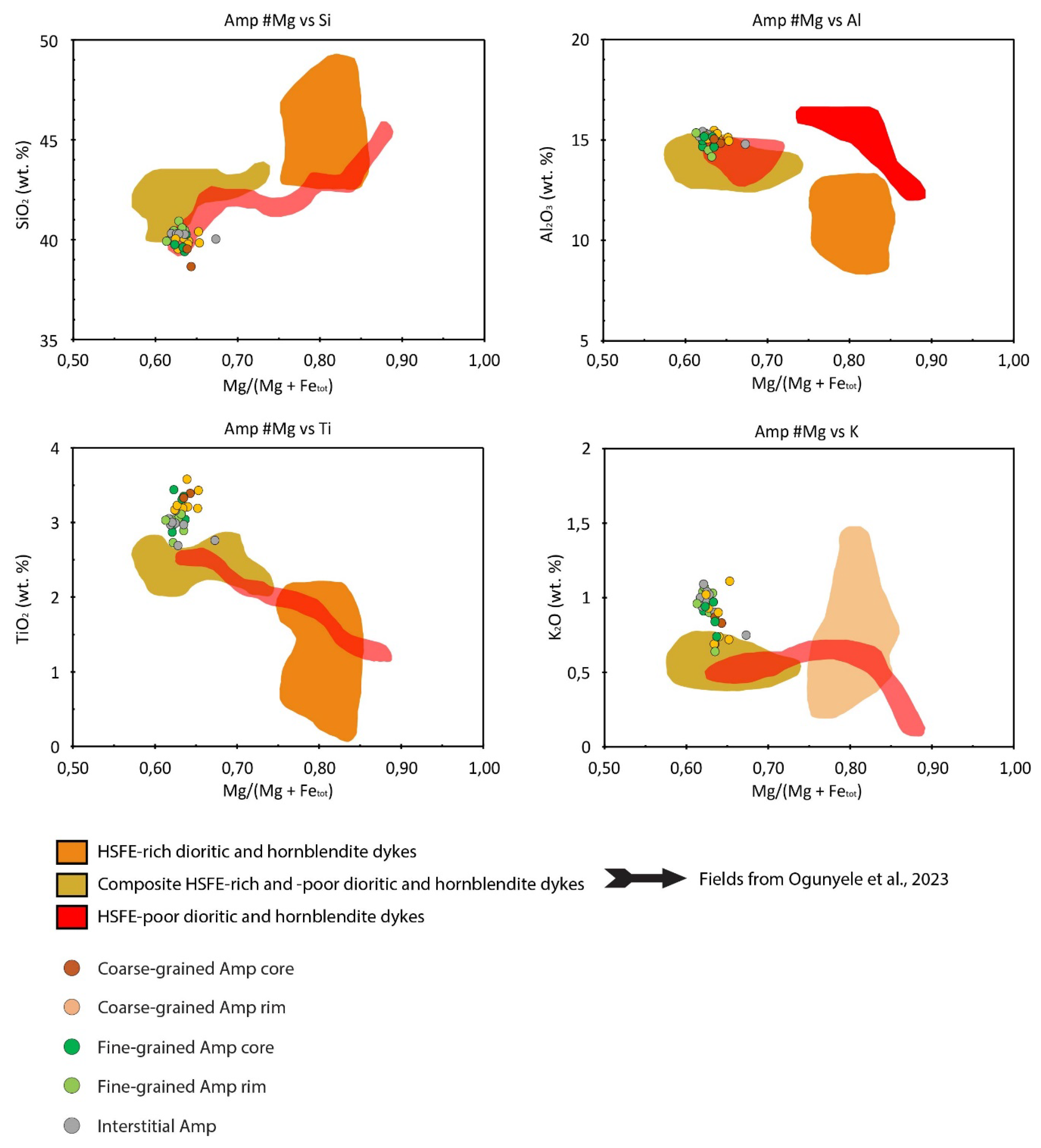

4.2.4. Thermobarometry

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison between the Ivrea Granulites and the Other Granulites of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone

5.2. The Stealth Metasomatism of the Mafic Complex in Ivrea

5.3. Nature of the Metasomatic Melt

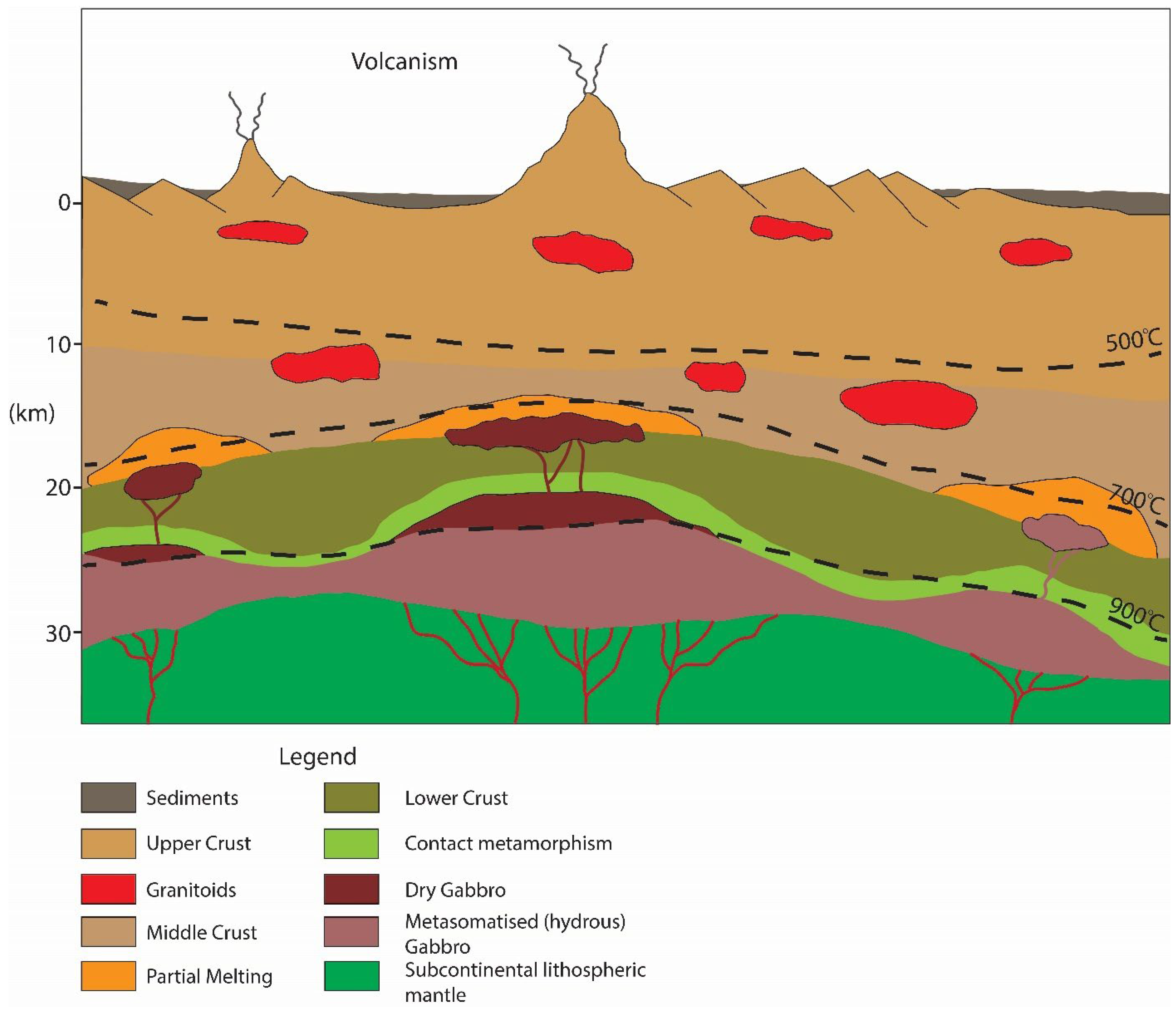

5.4. Permian Hydration of the Southalpine Lower Crust and Implications for Alpine Magma-Poor Rifting

6. Conclusions

- The granulites of the southern IVZ show many similarities with those belonging to the LMC of the central IVZ (Sessera Valley), and are supposed to be genetically similar to them, although with a possible lower degree of crustal contamination. The presence of stronalitic septa could indicate the proximity of a not-outcropping UMC to the south-east.

- The interstitial pargasitic amphibole and An-rich plagioclase in the mafic granulites have a metasomatic origin (stealth metasomatism) and were derived by the suprasolidus interactions between the former dry gabbro-norite with a more mafic hydrous-silicate melt infiltrated along channel (now hornblenditic dykes) and then percolated along grain boundaries.

- The metasomatic melt likely corresponds to the Early-Mesozoic post-collisional orogenic basaltic magmas, whose infiltration is well documented in the northern IVZ (Finero area).

- The metasomatic event is responsible for the hydration of large volumes of the thick hot lower crust, and for the changes in rheology of this crustal level.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daczko, N.R.; Piazolo, S.; Meek, U.; Stuart, C.A.; Elliott, V. Hornblendite delineates zones of mass transfer through the lower crust. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, C. A.; Meek, U.; Daczko, N. R.; Piazolo, S.; Huang, J. X. Chemical Signatures of Melt–Rock Interaction in the Root of a Magmatic Arc. J Petrol. 2018, 59, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.D.; Blundy, J.; Sparks, R.S.J. Chemical differentiation, cold storage and remobilization of magma in the Earth’s crust. Nature. 2018, 564, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, U.; Piazolo, S.; Daczko, N. R. The field and microstructural signatures of deformation-assisted melt transfer: Insights from magmatic arc lower crust, New Zealand. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2019, 37, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, M. R.; Franz, L.; Heller, F.; Janott, B.; Zurbriggen, R. Multistage accretion and exhumation of the continental crust (Ivrea crustal section, Italy and Switzerland). Tectonics. 1999, 18(6), 1154–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinigoi, S.; Quick, J.E.; Demarchi, G.; Peressini, G. The Sesia Magmatic System. Journal of the Virtual Explorer. 2010, 36, 4–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistone, M.; Ziberna, L.; Hetényi, G.; Scarponi, M.; Zanetti, A.; Müntener, O. Joint Geophysical-Petrological Modeling on the Ivrea Geophysical Body Beneath Valsesia, Italy: Constraints on the Continental Lower Crust. Geochem Geophys. 2020, 21, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrando, M.; Stockli, D. F.; Decarlis, A.; Manatschal, G. A crustal-scale view at rift localization along the fossil Adriatic margin of the Alpine Tethys preserved in NW Italy. Tectonics. 2015, 34, 1927–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decarlis, A.; Beltrando, M.; Manatschal, G.; Ferrando, S.; Carosi, R. Architecture of the Distal Piedmont-Ligurian Rifted Margin in NW Italy: Hints for a Flip of the Rift System Polarity. Tectonics. 2017, 36, 2388–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decarlis, A.; Zanetti, A.; Ogunyele, A.C.; Ceriani, A.; Tribuzio, R. The Ivrea-Verbano tectonic evolution: The role of the crust-mantle interactions in rifting localization. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 238, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, B.; Duretz, T.; Mohn, G.; Schmalholz, S.M.; Karner, G.D.; Müntener, O. Thinning mechanisms of heterogeneous continental lithosphere. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2019, 512, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, A.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Sinigoi, S.; Giovanardi, T.; Peressini, G.; Fanning, M. SHRIMP U-Pb Zircon Triassic Intrusion Age of the Finero Mafic Complex (Ivrea-Verbano Zone, Western Alps) and its Geodynamic Implications. J Petrol. 2013, 54, 2235–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnikhuis, J.K.; Daczko, N.R.; Langone, A. Open system reaction between hydrous melt and gabbroic rock in the Finero Mafic Complex. Lithos. 2023, 440-441, 107027. [CrossRef]

- Ogunyele, A.C.; Bonazzi, M.; Giovanardi, T.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Salters, V.J.M.; Decarlis, A.; Sanfilippo, A.; Zanetti, A. Transition from orogenic-like to anorogenic magmatism in the Southern Alps during the Early Mesozoic: Evidence from elemental and Nd-Sr-Hf-Pb isotope geochemistry of alkali-rich dykes from the Finero Phlogopite Peridotite, Ivrea–Verbano Zone. GR. 2023, 129, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthorn, R.G. The amphibole peridotite-metagabbro complex, Finero, northern Italy. J Geol. 1975, 83, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltorti, M.; Siena, F. Mantle tectonite and fractionate peridotite at Finero (Italian Western Alps). Neues Jahrbuch Für Mineralogie. Abhandlungen. 1984, 149, 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, G.; Hans Wedepohl, K. The composition of peridotite tectonites from the Ivrea Complex, northern Italy: Residues from melt extraction. GCA. 1993, 57, 1761–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Hofmann, A. W.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Rivalenti, G. The mafic-ultramafic complex near Finero (Ivrea-Verbano Zone), I. Chemistry of MORB-like magmas. Chem. Geol. 1997a, 140, 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Hofmann, A. W.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Rivalenti, G. The mafic-ultramafic complex near Finero (Ivrea-Verbano Zone), II. Geochronology and isotope geochemistry. Chem. Geol. 140, 223–235. [CrossRef]

- Morishita, T.; Hattori, K. H.; Terada, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Takebe, M.; Ishida, Y.; Tamura, A.; Arai, S. Geochemistry of apatite-rich layers in the Finero phlogopite–peridotite massif (Italian Western Alps) and ion microprobe dating of apatite. Chem. Geol. 2008, 251, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siena, F.; Coltorti, M. The petrogenesis of a hydrated mafic-ultramafic complex and the role of amphibole fractionation at Finero (Italian Western Alps). Neues Jahrbuch Für Mineralogie Monatshefte. 1989, 6, 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolani, M. La petrografia della Valle Strona (Alpi Occidentali Italiane). Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen, 1968, 48, 695. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, B. B.; Bartoli, O.; Ferri, F.; Cesare, B.; Ferrero, S.; Remusat, L.; Capizzi, L. S.; Poli, S. Anatexis and fluid regime of the deep continental crust: New clues from melt and fluid inclusions in metapelitic migmatites from Ivrea Zone (NW Italy). J Metamorph. Geol. 2019, 37, 951–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, L.; Harlov, D. E. High-Grade K-Feldspar Veining in Granulites from the Ivrea-Verbano Zone, Northern Italy: Fluid Flow in the Lower Crust and Implications for Granulite Facies Genesis. J Geol. 1998, 106, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlov, D. E. Review of petrographic and mineralogical evidence for fluid induced dehydration of the mafic lower crust: Could there be a relationship between granitoids and granulite facies xenoliths in the Variscan belt? Z. geol. Wiss. 2002, 30, 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Henk, A.; Franz, L.; Teufel, S.; Oncken, O. Magmatic Underplating, Extension, and Crustal Reequilibration: Insights from a Cross-Section through the Ivrea Zone and Strona-Ceneri Zone, Northern Italy. J Geol. 1997, 105, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, B. E.; Johnson, T. E.; White, R. W.; Redler, C. Partial melting of metabasic rocks in Val Strona di Omegna, Ivrea Zone, northern Italy. Lithos. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berno, D.; Tribuzio, R.; Zanetti, A.; Hérmond, C. Evolution of mantle melts intruding the lowermost continental crust: Constraints from the Monte Capio–Alpe Cevia mafc–ultramafc sequences (Ivrea–Verbano Zone, northern Italy). CMP. 2020, 175, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. A.; Kelsey, D. E.; Rubatto, D. Thorium zoning in monazite: A case study from the Ivrea–Verbano zone, NW Italy. J Metamorph. Geol. 2022, 40, 1015–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, D. C.; Smye, A. J.; Garber, J. M.; Hacker, B. R. Assembly and Tectonic Evolution of Continental Lower Crust: Monazite Petrochronology of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone (Val Strona di Omegna). Tectonics. 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, S. A.; Bergantz, G. W.; Brown, M. Regional granulite facies metamorphism in the Ivrea zone: Is the Mafic Complex the smoking gun or a red herring? Geology. 1999, 27, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinigoi, S.; Quick, J. E.; Clemens-Knott, D.; Mayer, A.; Demarchi, G.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Negrini, L.; Rivalenti, G. Chemical evolution of a large mafic intrusion in the lower crust, Ivrea-Verbano Zone, northern Italy. J. Geophys. Res. 1994, 99, 21575–21590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinigoi, S.; Quick, J. E.; Demarchi, G.; Klötzli, U. The role of crustal fertility in the generation of large silicic magmatic systems triggered by intrusion of mantle magma in the deep crust. CMP. 2011, 162, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoke, A. W.; Kalakay, T. J.; Quick, J. E.; Sinigoi, S. Development of a deep-crustal shear zone in response to syntectonic intrusion of mafic magma into the lower crust, Ivrea-Verbano zone, Italy. EPSL. 1999, 166(1–2), 31–45. [CrossRef]

- Sinigoi, S.; Demarchi, G.; Longinelli, A.; Mazzucchelli, M.; Negrini, L.; Rivalenti, G. Intractions of mantle and crustal magmas in the southern part of the Ivrea Zone (Italy). CMP. 1991, 108, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinigoi, S.; Quick, J. E.; Mayer, A.; Budahn, J. Influence of stretching and density contrasts on the chemical evolution of continental magmas: An example from the Ivrea-Verbano Zone. CMP. 1996, 123(3), 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribuzio, R.; Renna, M. R.; Antonicelli, M.; Liu, T.; Wu, F. Y.; Langone, A. The peridotite-pyroxenite sequence of Rocca d’Argimonia (Ivrea-Verbano Zone, Italy): Evidence for reactive melt flow and slow cooling in the lowermost continental crust. Chem. Geol. 2023, 619, 121315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucchelli, M.; Zanetti, A.; Rivalenti, G.; Vannucci, R.; Teixeira Correia, C.; Gaeta Tassinari, C.C. Age and geochemistry of mantle peridotites and diorite dykes from the Baldissero body: Insights into the Paleozoic–Mesozoic evolution of the Southern Alps. Lithos. 2010, 119, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrando, M.; Rubatto, D.; Manatschal, G. From passive margins to orogens: The link between ocean-continent transition zones and (ultra)high-pressure metamorphism. Geology. 2010, 38(6), 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, M.; Langone, A.; Bonazzi, M.; Corvò, S.; Maino, M. Tectono-metamorphic evolution of a post-variscan mid-crustal shear zone in relation to the Tethyan rifting (Ivrea-Verbano Zone, Southern Alps). J. Struct. Geol. 2023, 173, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, K. H.; Rutter, E. H.; Evans, P. On the structure of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone (northern Italy) and its implications for present-day lower continental crust geometry. Terra Nova. 1992, 4, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, D. M. The Ivrea—Verbano and Strona-Ceneri Zones, Northern Italy: A cross-section of the continental crust—New evidence from seismic velocities of rock samples. Tectonophysics. 1976, 33, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnert, K. The Ivrea Zone, a model of the deep crust. N. Jb. Mineral. Abh. 1975, 125, 156–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, S.; Bernoulli, D.; Compagnoni, R. The Canavese zone (internal Western Alps): A distal margin of Adria. Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen. 2004, 84, 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- Brack, P.; Ulmer, P.; Schmid, S. M. A crustal-scale magmatic system from the Earth’s mantle to the Permian surface − Field trip to the area of lower Valsesia and Val d’Ossola (Massiccio dei Laghi, Southern Alps, Northern Italy). Swiss Bull. angew. Geol. 2010, 15, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, B. E.; White, R. W. Phase equilibrium modelling of the amphibolite to granulite facies transition in metabasic rocks (Ivrea Zone, NW Italy). J. Metamorph. Geol. 2019, 37, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redler, C.; Johnson, T. E.; White, R. W.; Kunz, B. E. Phase equilibrium constraints on a deep crustal metamorphic field gradient: Metapelitic rocks from the Ivrea Zone (NW Italy). J. Metamorph. Geol. 2012, 30, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, E. H.; Brodie, K. H.; Evans, P. J. Structural geometry, lower crustal magmatic underplating and lithospheric stretching in the Ivrea-Verbano zone, northern Italy. J. Struct. Geol. 1993, 15, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.; Wood, B. J. Phase relationships in granulitic metapelites from the Ivrea-Verbano zone (Northern Italy). CMP. 1976, 54, 255–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sills, J. D.; Tarney, J. Petrogenesis and tectonic significance of amphibolites interlayered with metasedimentary gneisses in the Ivrea Zone, Southern Alps, Northwest Italy. Tectonophysics. 1984, 107, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingg, A. Regional metamorphism in the Ivrea zone (Southern Alps, N-Italy): Field and microscopic investigations. Schweizerische Mineralogische und Petrographische Mitteilungen. 1980, 60, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnetger, B. Partial melting during the evolution of the amphibolite- to granulite-facies gneisses of the Ivrea Zone, northern Italy. Chem Geol. 1994, 113, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redler, C. White, R. W. Johnson, T. E. Migmatites in the Ivrea Zone (NW Italy): Constraints on partial melting and melt loss in metasedimentary rocks from Val Strona di Omegna. Lithos. 2013, 175–176, 40–53. [CrossRef]

- Quick, J. E.; Sinigoi, S.; Mayer, A. Emplacement dynamics of a large mafic intrusion in the lower crust, Ivrea-Verbano Zone, northern Italy. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1994, 99, 21559–21573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsch, D. Die Metabasite des Valle Strona (Ivrea Zone) (2. Teil). Neues Jahrbuch Mineralogische Abhandlungen. 1973, 119, 266–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, T. A.; Hermann, J.; Rubatto, D. The robustness of the Zr-in-rutile and Ti-in-zircon thermometers during high-temperature metamorphism (Ivrea-Verbano Zone, northern Italy). CMP. 2013, 165(4), 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivalenti, G.; Garuti, G.; Rossi, A.; Siena, F.; Sinigoi, S. Existence of Different Peridotite Types and of a Layered Igneous Complex in the Ivrea Zone of the Western Alps. J Petrol. 1981, 22, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sills, J. D. Granulite facies metamorphism in the Ivrea zone, N. W. Italy. Schweizerische Mineralogische Und Petrographische Mitteilungen. 1984, 64, 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- Peressini, G.; Quick, J. E.; Sinigoi, S.; Hofmann, A. W.; Fanning, M. Duration of a large mafic intrusion and heat transfer in the lower crust: A SHRIMP U–Pb zircon study in the Ivrea–Verbano Zone (Western Alps, Italy). J Petrol. 2007, 48, 1185–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, S. A.; Bergantz, G. W. Metamorphism and Anatexis in the Mafic Complex Contact Aureole, Ivrea Zone, Northern Italy. J Petrol. 2000, 41, 1307–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, J. E.; Sinigoi, S.; Negrini, L.; Demarchi, G.; Mayer, A. Synmagmatic deformation in the underplated igneous complex of the Ivrea-Verbano zone. Geology. 1992, 20, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivalenti, G. The origin of the Ivrea-Verbano basic formation (western Italian Alps)-whole rock geochemistry. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1975, 94, 1149–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Sinigoi, S.; Quick, J. E.; Mayer, A.; Demarchi, G. Density-controlled assimilation of underplated crust, Ivrea-Verbano zone, Italy. EPSL. 1995, 129, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, O.; Wotzlaw, J. F.; Guillong, M.; Ulmer, P.; Brack, P.; Economos, R.; Bergantz, G. W.; Sinigoi, S.; Bachmann, O. The pace of crustal-scale magma accretion and differentiation beneath silicic caldera volcanoes. Geology. 2019, 47(8), 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucchelli, M.; Rivalenti, G.; Brunelli, D.; Zanetti, A.; Boari, E. Formation of highly refractory dunite by focused percolation of pyroxenite-derived melt in the Balmuccia peridotite Massif (Italy). J Petrol. 2009, 50(7), 1205–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, J. E.; Sinigoi, S.; Snoke, A. W.; Kalakay, T. J.; Mayer, A.; Peressini, G. Geologic map of the southern Ivrea-Verbano Zone, northwestern Italy. USGS. 2003, 2776. [Google Scholar]

- Shervais, J. W. Ultramafic layers in the alpine-type lherzolite massif at Balmuccia, NW Italy. Memorie di Scienze Geologiche. Universita’di Padova. 1979, 33, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucchelli, M.; Quick, J. E.; Sinigoi, S.; Zanetti, A.; Giovanardi, T. Igneous evolutions across the Ivrea crustal section: The Permian Sesia Magmatic System and the Triassic Finero intrusion and mantle. GFT. 2014, 6, 1–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, P. NORM-Program for cation and oxygen mineral norms: Computer Library. Institute fûr Mineralogie und Petrographie, ETH-Zentrum, Zürich, Switzerland. 1986.

- Paton, C.; Hellstrom, J.; Paul, B.; Woodhead, J.; Hergt, J. Iolite: Freeware for the visualisation and processing of mass spectrometric data. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2011, 26, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, F. E.; O'Neill, H. S. C. Major and trace analysis of basaltic glasses by laser-ablation ICP-MS. Geochem Geophys. 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney D., L.; Evans B., W. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. Am. Min. 2010, 95, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Maitre, R. W.; Streckeisen, A.; Zanettin, B.; Le Bas, M. J.; Bonin, B.; Bateman, P. Igneous rocks: A classification and glossary of terms: Recommendations of the International Union of Geological Sciences Subcommission on the Systematics of Igneous Rocks. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005.

- McDonough, W. F.; Sun, S.S. The composition of the Earth. Chem Geol. 1995, 120(3–4), 223–253. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Wei, C.; Rehman, H.U. Titanium in calcium amphibole: Behavior and thermometry. Am. Mineral. 2021, 106, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, O.; Carvalho, B.B.; Farina, F. Effectiveness of Ti-in-amphibole thermometry and performance of different thermometers across lower continental crust up to UHT metamorphism. CMP. 2024, 179, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raase, P. Al and Ti contents of hornblende, indicators of pressure and temperature of regional metamorphism. CMP. 1974, 45, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrutkin, V.V. The evolution of amphiboles during metamorphism. Zapiski Vsesoyuznovo Mineralogicheskovo Obshchestva. 1968, 96, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon, R. H.; Collins, W. J.; Cook, N. D. J. Metamorphism and deformation of mafic and felsic rocks in a magma transfer zone, Stewart Island, New Zealand. J Metamorph. Geol. 2012, 30(5), 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, R. H. Microstructures of melt-bearing regional metamorphic rocks. In Origin and Evolution of Precambrian High-Grade Gneiss Terranes, with Special Emphasis on the Limpopo Complex of Southern Africa, Van Reenen, D.D., Kramers, J.D., McCourt, S., Perchuk, L.L., Eds.; The Geological Society of America: Colorado, USA, 2011, 207, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Holness, M. B.; Sawyer, E. W. On the pseudomorphing of melt-filled pores during the crystallization of migmatites. J. Petrol. 2008, 49(7), 1343–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holness, M. B.; Cesare, B.; Sawyer, E. W. Melted rocks under the microscope: Microstructures and their interpretation. Elements. 2011, 7, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Reilly, S. Y.; Griffin, W. L. Mantle Metasomatism. In Metasomatism and the Chemical Transformation of Rock, 1st ed.; Harlow, D. E., Austrheim, H., Eds.; Publisher: Springer-Verlag, Germany, 2013; pp. 471–534. [Google Scholar]

- Maierová, P.; Hasalová, P.; Schulmann, K.; Štípská, P. Souček, O. Porous melt flow in continental crust - A numerical modeling study. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2023, 128, e2023JB026523. [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, R. L. Making continental crust. Nature. 1995, 378, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, T. W.; Ratajeski, K.; Hankins, W. B.; Glazner, A. F. Voluminous granitic magmas from common basaltic sources. CMP. 2005, 148, 635–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, B. C.; Schoene, B.; Barbonu, M.; Samperton, K. M. Husson, J. M. Volcanic–plutonic parity and the differentiation of the continental crust. Nature. 2015, 523, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.; Liptai, N.; Koptev, A.; Cloetingh, A.S.P.L.; Lange, T.P.; Matenco, L.; Szakács, A.; Radulian, M.; Berkesi, M.; Patkó, L.; Molnár, G.; Novák, A.; Wesztergom, V.; Szabó, C.; Fancsik, T. The ‘pargasosphere’ hypothesis: Looking at global plate tectonics from a new perspective. Global Planet. Change. 2021, 204, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C. E. The influence of pressure on the properties and origins of hydrous silicate liquids in Earth's interior. In Magmas Under Pressure 2018, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; Osamura, K.; Takahashi, E. Effect of water saturation on the distribution of partial melt in the Olivine-Pyroxene-Plagioclase System. J. Geophys. Res. 1986, 91, 9253–9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, R.S.J.; Annen, C.; Blundy, J.D.; Cashman, K.V.; Rust, A.C.; Jackson, M.D. Formation and dynamics of magma reservoirs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 2019, 377, 20180019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müntener, O.; Hermann, J.; Trommsdorff, V. Cooling History and Exhumation of Lower-Crustal Granulite and Upper Mantle (Malenco, Eastern Central Alps). J Petrol. 2000, 41, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenin, P.; Manatschal, G.; Decarlis, A.; Schmalholz, S.M.; Duretz, T.; Beltrando, M. Emersion of Distal Domains in Advanced Stages of Continental Rifting Explained by Asynchronous Crust and Mantle Necking. Geochem Geophys. 2019, 20, 3821–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerc, C.; Ringenbach, J.C.; Jolivet, L.; Ballard, J.F. Rifted margins: Ductile deformation, boudinage, continentward-dipping normal faults and the role of the weak lower crust. GR. 2018, 53, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykins, R.W.; Jenkins, D.M. Experimental determination of pargasite stability relations in the presence of orthopyroxene. CMP. 1992, 112, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manatschal, G.; Chenin, P.; Ulrich, M.; Petri, B.; Morin, M.; Ballay, M. Tectono-magmatic evolution during the extensional phase of a Wilson Cycle: A review of the Alpine Tethys case and implications for Atlantic-type margins. Ital J Geosci. 2023, 142, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, B.; Wijbrans, J.; Mohn, G.; Manatchal, G.; Beltrando, M. Thermal evolution of Permian post-orogenic extension and Jurassic rifting recorded in the Austroalpine basement (SE Switzerland, N Italy). Lithos, 2023, 444-445, 107124. [CrossRef]

- Real, C.; Fassmer, K.; Carosi, R.; Froitzheim, N.; Rubatto, D.; Groppo, C.; Münker, C.; Ferrando, S. Carboniferous–Triassic tectonic and thermal evolution of the middle crust section of the Dervio–Olgiasca Zone (Southern Alps). J. Metamorph. Geol. 2023, 41, 685–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample name | Coordinates (N, E) | Specimen Decsription |

|---|---|---|

| IZ21-01 | 45° 26’ 47’’, 7° 52’ 48’’ | Medium-grained enderbite |

| IZ21-02 | 45° 26’ 47’’, 7° 52’ 47’’ | Coarse-grained enderbite |

| IZ21-03 | 45° 26’ 47’’, 7° 52’ 46’’ | Coarse-grained enderbite in contact with fine-grained enderbitic dyke |

| IZ21-04 | 45° 26’ 51’’, 7° 52’ 53’’ | Very coarse-grained enderbite |

| IZ21-06 | 45° 28’ 29’’, 7° 52’ 49’’ | Fine-grained stronalite |

| IZ21-07 | 45° 28’ 29’’, 7° 52’ 50’’ | Medium-grained stronalite |

| IZ21-13 | 45° 28’ 37’’, 7° 52’ 55’’ | Medium-grained stronalite with cm-sized garnet porphyroblasts |

| IZ21-14 | 45° 26’ 41’’, 7° 51’ 50’’ | Coarse-grained mafic granulite with pegmatoid coarse-grained lens |

| IZ21-15 | 45° 26’ 41’’, 7° 51’ 50’’ | Cpx-rich band in contact with sample IZ21-14 |

| IZ21-17 | 45° 26’ 41’’, 7° 51’ 50’’ | Coarse-grained amp-rich mafic granulite |

| IZ21-18 | 45° 26’ 40’’, 7° 51’ 49’’ | Coarse-grained mafic granulite |

| IZ21-19 | 45° 26’ 39’’, 7° 51’ 49’’ | Anhydrous coarse-grained mafic granulite |

| IZ21-20 | 45° 26’ 39’’, 7° 51’ 48’’ | Foliated coarse–grained mafic granulite |

| IZ21-21 | 45° 26’ 40’’, 7° 51’ 49’’ | Slightly foliated medium-grained mafic granulite with Cpx porphyroblasts |

| IZ21-22 | 45° 26’ 37’’, 7° 51’ 56’’ | Medium- to coarse-grained mafic granulite, rich in opaques |

| IZ21-23 | 45° 26’ 27’’, 7° 51’ 39’’ | Homogeneous medium- to coarse-grained mafic granulite |

| IZ23-02b | 45° 28’ 19’’, 7° 52’ 58’’ | Anhydrous, low-Cpx mafic granulite with pyroxenitic layer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).