1. Introduction

There is no consensus on the definition and purpose of student leadership, as well as how it should be encouraged and labeled. However, in the literature, expressions such as participation, active citizenship, democratic school, and giving students a voice are used in relation to student leadership (Black et al., 2014). In this context, it can be said that student leadership should be taught to all students with a sense of social responsibility (Gott et al., 2019). In this teaching process, learning leadership and developing leadership skills may require different learning methodologies than learning other subjects in a normal classroom environment, as it is different (Eich, 2008; Jenkins, 2013; Wren, 1995). In this context, according to Seemiller (2016), students' leadership competencies can be developed in two ways: through an on-the-job learning approach they learn through experience and a more intentional and developmental approach involving education, teaching, coaching, and feedback. In addition, implicit learning such as public awareness campaigns, political campaigns, informal learning, and socialization are also needed for the development of students' leadership skills (Hoffman et al., 2008).

The values, thoughts and behaviors that form the essence of leadership are social and interactive processes; therefore, they are culturally influenced. This fact causes leadership to be approached from different perspectives depending on cultural differences. For example; while leadership in Western societies is seen as based on a set of technical skills, in Chinese society leadership is more seen as a process of influencing relationships and modeling desired behaviors (Dimmock and Walker, 2005). There are many studies in the literature showing that leadership understanding differs in different cultures (Dorfman et al., 1997; Dwairy, 2019; Euwema, 2007; Jogulu, 2010; Shahin & Wright, 2004; Taleghani et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012).

Based on the research on the leadership-culture axis, it can be argued that the leadership profiles of students continuing their education in different cultures may also differ. Furthermore, the implementation of a school-centered management strategy, known as democratization, has been found to have beneficial impacts on leadership (Pont et al., 2008). inside this particular framework, it is posited that the augmentation of democratization levels inside nations could potentially impact the leadership characteristics of individuals, particularly students, residing within said country. The results of some globally applied exams can be used to test the reality of this claim. PISA, TIMSS, PIRLS, TALIS are among the exams applied globally (Gümüş et al., 2024; Nilsen & Teig, 2022; Sampaio Maia et al., 2022; Teig, 2022). PISA has emerged as a valid and reliable criterion for evaluating student performance, providing comparative data on educational outcomes among participating countries. It has gained significant influence on education policy and decision-making processes worldwide (AlKaabi et al., 2022). In the literature, there are studies focusing on the relation of PISA to countries' education policies (Araujo et al., 2017; Białecki et al., 2017; Carvalho et al., 2017; Dobbins & Martens, 2012; Niemann et al., 2017; Rautalin et al., 2019; Schleicher & Zoido, 2016; Sellar & Lingard, 2013; Tasaki, 2017; Waldow, 2009; Zoido, 2016) and students' competencies in certain areas (reading, scientific literacy, mathematical literacy, inquiry skill, financial literacy, etc.) (Amir et al., 2023; Hopfenbeck & Kjærnsli, 2016; Lavonen & Laaksonen, 2009; Jerrim et al., 2022; Jerrim & Moss, 2019; Stacey, 2011; Sadler & Zeidler, 2009; Teig et al., 2020; Zhang & Liu, 2016). However, no research examining the data on students' leadership profiles included in PISA has been encountered. In this context, in our research, it will be examined whether there is a difference in the leadership profiles of students living in different countries, based on PISA results. For this, first, the reflections of the relationship between leadership and culture on individuals are discussed.

2. Reflections of the Relationship between Leadership and Culture on Individuals

Although globalization has led to the convergence of many intercultural activities, cultural differences persist (Bayraktar et al., 2022). Societal culture has a major influence on the emergence of these differences. Societal culture imposes certain assumptions, ideas, traditions, and attitudes on the people living in that society, affecting their perceptions of reality and their behaviors within reality (Hofstede, 2001). In this way, societal culture shapes acceptable and unacceptable behaviors in a given situation. At the same time, societal culture limits the leadership behaviors and characteristics accepted in that culture (Resick et al., 2011). Summarizing the situation, Bass (1997) states that organizational and cultural factors influence the concept of leadership. Additionally, according to research, managers' leadership styles and organizational work practices differ depending on the cultures in which they are applied and have various consequences on employee work outcomes (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Fischer et al., 2014; Hong et al., 2016; Jogulu, 2010; Lok & Crawford, 2004).

The assumptions of Role Theory, defined by Biddle (1979) as "a science concerned with the study of the characteristic behaviours of people in contexts and the processes that produce, explain, or are influenced by these behaviours", can be used to demonstrate the relationship between leadership and culture. Role theory posits that expectations define roles (Polzer, 2015). According to this theory, leadership as a role is significantly influenced by certain ideals and leads to the preference of a particular leadership role in the workplace (Chong et al., 2018; Shivers-Blackwel, 2004). Additionally, Role Theory addresses the extent to which leadership behaviors are fixed or vary depending on values. The East-West dichotomy is one of the defined value categories (Oyserman et al., 2009). Based on the assumptions of Role Theory, it can be said that leaders can redefine their roles by considering culturally significant symbolic values in their behaviors (Arun and Gedik, 2020; Dorfman et al., 1997; Hayward et al., 2017; Kim & Park, 2020; Van de Vliert, 2008).

It is an undeniable reality that there are many similarities regarding management processes of organizations in a globalized world. The literature focuses more on these common points rather than how leadership roles, behaviors, and styles can differ across different cultural or work contexts (Gutierrez et al., 2012). On the other hand, cultural fit seems to be overlooked in leadership-related theories and practices. This situation highlights a mono-cultural understanding while causing alienation, isolation, and disadvantages for indigenous and ethnic groups (Collard, 2007).

The evolution in leadership approaches also reveals the importance of culture in this regard. Accordingly, Sanchez-Runde et al. (2011) analysed contemporary approaches in the context of global leadership models under three sub-headings. These are the Universal Approach, which argues that leadership is a universal characteristic, the Normative Approach, which focuses on the characteristics and skills of global leaders, and the Contingency Approach, which rejects universal principles for effective leadership and recommends that leaders change their behaviours according to local characteristics. This approach emphasises the role of situational variables and culture as contextual factors affecting leadership. In addition, this approach considers it necessary to consider the relationship between leader behaviour and the situational environment, including cultural differences, in understanding effective leadership (Ayman et al., 2007).

At this point, the question of what should be the main issues to be considered in the leadership-culture relationship comes to mind. Miller (2017) argues that factors such as language, beliefs, values, religion and social organisations cause cultural differences in the international perspective. In addition, it is stated that the good governance of countries, in other words, the understanding of governance followed in meeting social needs and providing services, is also effective in the understanding of leadership in that country (Ahmed, 2021). In this context, it can be said that the management approaches of countries have a role in making the existence of different leadership practices more apparent. The existence in question can become dominant in the understanding of leadership as a cultural code. For example, while participatory and inclusive leadership practices are valued in a democratic management approach, organisational structures, discourses, speech and communication within the hierarchy are given great importance (Barthold et al., 2020). In addition, in such managements, responsibility is distributed among members, empowering group members and enabling them to take part in decision-making processes (Gastil, 1994; Hulpia & Devos, 2010; Quiroz-Niño & Blanco-Encomienda, 2019; Spreitzer, 2007; Woods, 2004). In addition, in environments where democratic leadership is dominant, women's leadership is supported for long-term socio-economic growth and great importance is attached to the diversification of the workforce and the empowerment of individuals (Maheshwari et al., 2021). These practices contribute to the positive development of individuals' culture of democracy and democratic leadership understanding (Bowler & Donovan, 2002; Cho, 2014; Garrison, 2003; Velarde & Ghani, 2019).

In societies where undemocratic leadership is dominant, situations such as concentration of power and authority in the hands of a few people, harsh decision-making, violation of democratic norms and principles, absolute domination of subordinates, and disregard of subordinates' contributions and suggestions are common (Adıguzel et al., 2020; Barański, 2020; Gao, 2021; Keenan & Zavala, 2021; Li & Wang, 2015; Taldykin, 2021). However, it is also seen that information manipulations are used to create a positive image instead of transparency and honesty in communication (Shan et al., 2022). In this context, absolute obedience and loyalty can be mentioned in conditions where undemocratic leadership is dominant (Sekulova et al., 2017; Woodward et al., 2008). In addition, the understanding of tolerating undemocratic behaviours is at a higher level in such environments (Frederiksen, 2022; Passini & Morselli, 2010; Simonovits et al., 2022). In addition, it is seen that women leaders face many problems in undemocratic leadership and are tried to be prevented from being in leadership positions (Rizzo et al., 2007; Stowers et al., 2019; Yadav & Fidalgo, 2021).

In addition to the theoretical context, existing studies in the literature show that culture and leadership are interrelated (Dastmalchian, 2001; Wong, 2001); management style and cultural elements affect educational outcomes (Luschei & Jeong, 2020). For example; in a study conducted in China (Bush & Haiyan, 2000), it was determined that students' leadership skills developed in the form of loyalty to authority, collectivism and respect for harmony. In a similar study conducted in Iran (Dastmalchian, et al., 2001), it was noted that leadership profiles are influenced by cultural factors. It is well known that leadership style or leadership perception is influenced by local and cultural elements (Oplatka & Arar, 2016). In the literature, there are many studies on school leadership (Bush & Glover, 2014; Day et al., 2020; Flessa et al., 2018) and instructional leadership (Hallinger, 2005; Horng, & Loeb, 2010). However, there is no study examining the effect of the form of government and local culture on students' leadership profiles. This has been the motivation for this study. Developing students' leadership skills helps them to become individuals who guide others correctly, take responsibility, work hard and make effective decisions in their business life or social roles in the following years (Kapur, 2019). Therefore, the leadership profiles of students are important indicators for the future of the society and the country in which they live. In addition to revealing the current situation of 15-year-old students at the international level, the PISA application also provides important information for the generation of countries that will soon be involved in business life. In this respect, the items related to leadership in the student questionnaires of the PISA 2022 application (items coded between ST305Q01JA- ST305Q10JA) are very important in terms of revealing whether students show different leadership profiles and examining whether these leadership profiles change according to the management style and cultural characteristics.

In order to examine the leadership profiles of students, the data of Guatemala, Cambodia, Peru and Paraguay of the PISA 2022 application were analysed using Latent Class Analysis (LCA). The reason why latent class analysis is preferred in examining students' leadership profiles is that it is an individual-based approach (Bergman & Wangby, 2014) and does not require assumptions such as sampling normality and homogeneity of variances (Kankaras, Vermunt & Moors, 2011). LCA is a statistical method used to identify subgroups of a large population through a set of indicators (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, 2018). In the selection of the countries included in the research sample, attention was paid to the fact that they represent different situations in terms of culture and management style variables that are expected to affect the distribution of student leadership profiles.

To summarize, the aim of this research is to examine the leadership profiles of students through the PISA 2022 data. In line with this aim, answers to the following questions are sought:

According to the PISA 2022 data, do students have different leadership profiles?

Do the leadership profiles exhibited by students vary between countries with different administrative styles and cultures?

3. Method

3.1. Sample

The PISA 2022 assessment formed the main data for this study. The analyses of the research were carried out on a total of 22,521 students from four countries, namely Guatemala, Cambodia, Paraguay, and Peru, which participated in the PISA 2022 assessment. In terms of their distribution in the sample, Guatemala accounts for 23% (5,190), Cambodia 23.4% (5,279), Paraguay 22.6% (5,084), and Peru 30.9% (6,968). A total of 81 countries from different continents of the world participated in the PISA 2022 assessment (OECD, 2023a). A two-stage sampling method was used in the sample selection for the countries participating in the PISA 2022 assessment (OECD, 2023b). Within the scope of this research, the countries of Guatemala, Cambodia, Paraguay, and Peru, which have different cultural and administrative understandings, were selected to determine the leadership profiles of students.

3.2. Data Collection Tools

The analyses of this research were carried out using the data from the student questionnaires of the PISA 2022 assessment. When examining the PISA 2022 reports, it was observed that the student questionnaires section included several items related to students' leadership characteristics (Educational Testing Service, 2021). The items included in the student questionnaires within the scope of the PISA 2022 assessment inquire about the students' degree of participation in relevant items that are indicators of the "leadership" characteristic. These items were graded with the options "Strongly disagree (1), Disagree (2), Neither agree nor disagree (3), Agree (4), Strongly agree (5)". Detailed information about the items included in the questionnaire is shown in

Table 1.

As seen in

Table 1, the first column shows the item codes, the second column shows the item content, and the third column shows the information about the item rating scales. The research data were downloaded from the official website (OECD, 2023c) where the PISA results are published.

4. Findings

Firstly, within the scope of the study, based on the research data formed by the samples of Guatemala, Cambodia, Paraguay, and Peru through the implementation of PISA 2022, whether students exhibit multiple leadership profiles was examined. This process was carried out in line with the research question formulated as "Are there different leadership profiles among students according to PISA 2022 data?" Latent Class Analysis (LCA) technique was employed to answer the research question. LCA is a technique commonly used to identify latent groups in large samples. This technique is based on grouping individuals with similar response patterns into the same class based on their response patterns to items. In this respect, the classes to which individuals belong are defined as latent variables and explained through observable variables (Hagenaars & McCutcheon, 2002). Generally, latent class analysis begins with a single-class model where individuals do not differ in response patterns, and the number of classes is increased until the most appropriate model is determined (Lanza et al., 2007). Accordingly, starting from a single-class latent model, parameter estimations were conducted by repeating LCA for models up to a six-class latent model. The model fit criteria for models up to a six-class latent model based on the research data are presented in

Table 2.

In

Table 2, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the number of parameters, classification error, and class sizes are compared for six different models. These pieces of information are crucial for determining the model that best fits the data. BIC, also known as the Schwarz Information Criterion, was introduced by Gideon E. Schwarz in a paper published in 1978. BIC is a criterion calculated based on the number of parameters in the model when evaluating model fit in LCA. It is preferred for making comparisons based on corrected probability according to the complexity of the model. Lower BIC values indicate a better fit of the model to the data (Schwarz, 1978). In this table, we can observe that as the number of models increases, BIC values generally decrease. This indicates that more classes improve the model's fit to the data, but the rate of decrease in BIC is also important. The number of parameters indicates the complexity of the model. The fundamental goal of data reduction methods such as LCA is to explain complex data structures with the simplest model consisting of fewer variables. Classification error is a measure of the model's ability to assign individuals to classes correctly. A lower classification error indicates better performance of the model. Class sizes indicate the relative magnitude of each latent class in the dataset. This shows how prevalent a particular class is.

In light of these considerations, when scrutinizing the model fit criteria presented in

Table 2, it is imperative to strike a balance among the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values, classification error, and the interpretability of the model when determining the most suitable model. Typically, preference is accorded to a model exhibiting low BIC values alongside a reasonable classification error. Nevertheless, one must also weigh the model's complexity and interpretability. In this instance, the 3-class model may be deemed a prudent selection owing to its notably low BIC value and relatively modest classification error. Moreover, it is discernible that the distribution of class sizes is reasonable. However, the ultimate decision-making authority lies within the domain of the social sciences (Green, 1952), contingent upon additional factors such as the research inquiry, dataset characteristics, and interpretative nuances (Schwarz, 1978). In light of these multifaceted considerations, it appears judicious to employ and report the 3-class latent model. However, in this study, both the 3-class and 2-class models are reported to scrutinize the variation in leadership attributes within the sample cohort vis-à-vis the number of classes. The 3-class model emerges as the most cogent option for the dataset. Thus, in comparison to the 3-class model, the 2-class model yields diminished differentiation among students and furnishes less substantive insights for the sample cohort. The rationale behind eschewing the selection of the 4-class model for comparative analysis predominantly stems from its markedly elevated classification error and the failure of all class sizes to confer meaningful proportions. Consequently, both the 2-class and 3-class models evince superior classification accuracy and evince a judicious distribution concerning class sizes. Profile plots depicting response probabilities for all latent models up to six classes are depicted in

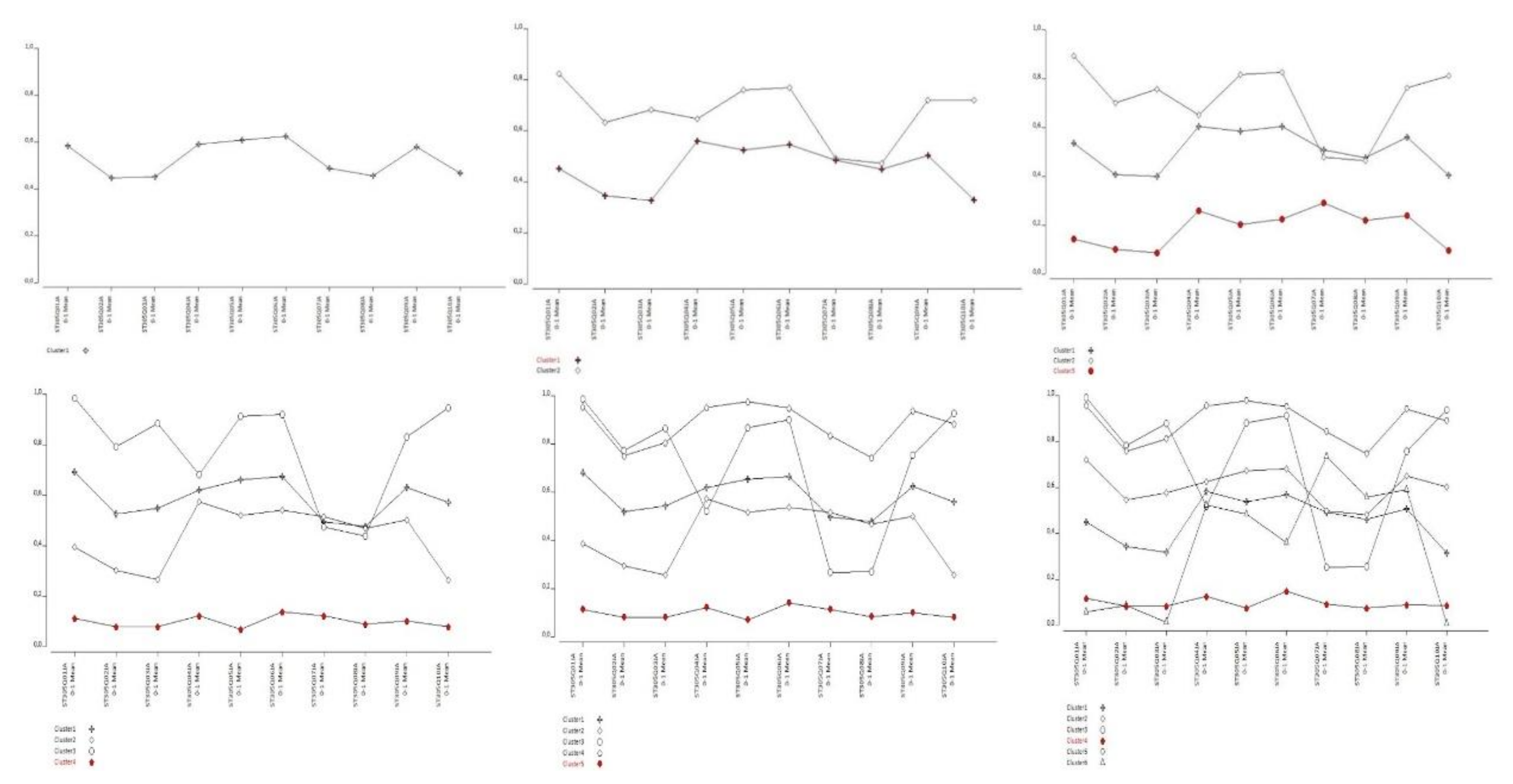

Figure 1.

The "Profile Plots of Response Probabilities for Latent Classes" seen in

Figure 1 is one of the significant outputs of Latent Class Analysis (LCA). Each line in these plots represents the characteristics of latent classes concerning different criteria, items, or, in other words, observable variables. Each point on the graph represents the mean response of classes for a specific criterion. In simpler terms, these plots illustrate profiles exhibited by individuals with similar response patterns in each graph. When observing

Figure 1, it can be noticed that individuals with different profiles in the four, five, and six-class models are intertwined to the extent that they are almost indistinguishable from each other. This situation is also evident from the classification error value interpreted in the preceding paragraph referring to

Table 2. As known, classification error is an indicator of the likelihood of errors in determining latent classes by the model. Accordingly, it can be inferred from

Figure 1 that four, five, and six-class latent models are more complex and entail more errors in distinguishing participant profiles. Conversely, it can be said that two and three-class latent models yield relatively better results. Interpretation of latent classes or participant profiles based on the graphs of latent models in

Figure 1 is possible. However, to enhance the transparency of research findings and enable more detailed examinations, conditional response probabilities of observable variables for two and three-class models are presented in

Table 3.

According to the information in

Table 3, for the two-class latent model, the first latent class (Cluster 1) encompasses individuals with low comfort with leadership roles and desire to lead, who tend to avoid sharing their opinions in group discussions. This group could be termed as "Reserved or Lack of Confidence Group". The second latent class of the two-class model (Cluster 2) includes individuals who prefer taking on leadership roles and influencing others, generally being active in group discussions and enjoying taking initiative. This group could be labeled as "Active Leader or Influencer Group".

For the three-class latent model, the first latent class (Cluster 1) may consist of individuals who respond neutrally or positively to leadership-related items but do not show a strong inclination towards leadership or influencing others. This group could be referred to as the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group". The second class of the three-class model (Cluster 2) encompasses individuals who strongly enjoy assuming leadership roles and influencing others, actively participating in such roles. This group could be named as the "Strong Leader or Influencer Group". The third class of the three-class model (Cluster 3) may include individuals who exhibit very low probabilities in leadership and influence-related aspects, often avoiding or feeling discomfort with such roles. This group could be designated as the "Avoidant or Discomfort with Leadership Group".

When comparing the two and three-class models, it is observed that the two-class model generally yields two broader groups representing specific behaviors or attitudes. On the other hand, in the three-class model, one or both of these general groups are further elaborated and subdivided into more specialized subgroups. This allows for the identification of more finely tuned groups with specific characteristics, aiding in a more detailed understanding of the behaviors or attitudes of these groups.

Secondly, within the scope of the research, using the PISA 2022 data, the distribution of students in the samples from Guatemala, Cambodia, Paraguay, and Peru was examined based on latent class analysis using both two and three-class latent models. This process was conducted in line with the research question, which was formulated as "Do leadership profiles exhibited by students vary across countries with different governance styles and cultures?" The results are presented in

Table 4.

When examining

Table 4, it can be observed that in the two-class model, Cambodia mostly falls into the "Shy or Lack of Confidence Group," whereas in the three-class model, it is more prevalent in the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group." This suggests that students in Cambodia tend to exhibit more reserved or moderate tendencies in leadership-related situations. The distributions for Guatemala and Paraguay, in both countries, there is approximately equal distribution in the two-class model, while in the three-class model, the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group" and "Strong Leader or Influential Group" are more pronounced. This indicates a more diverse range of tendencies among individuals regarding leadership and influence in these countries. Looking at the distributions for Peru, it is observed that almost all students are in the "Active Leader or Influential Group" in the two-class model and in the "Strong Leader or Influential Group" in the three-class model. This suggests that students in Peru tend to be very active and influential in leadership matters.

These interpretations of the research findings imply that latent classes may vary across countries and that certain cultural or societal factors may influence these tendencies.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

In the study, the first latent class (Cluster 1) identified within the two-class model comprises individuals characterized by a low comfort level and desire to take on leadership roles, often avoiding sharing their own opinions in group discussions. This group could be labeled as the "Reserved or Lack of Self-Confidence Group." The second latent class of the two-class model (Cluster 2) consists of individuals who prefer to assume leadership roles and influence others, typically actively participating in group discussions and enjoying taking initiative. This group could be termed the "Active Leaders or Influential Group." For the three-class model, the first latent class (Cluster 1) may include individuals who respond neutrally or positively to items related to leadership but do not exhibit a strong inclination towards leadership or influence. They could be referred to as the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group." The second class of the three-class model (Cluster 2) comprises individuals who strongly enjoy taking on leadership roles and influencing others, actively engaging in such roles. This group could be identified as the "Strong Leaders or Influential Group." Finally, the third class of the three-class model (Cluster 3) may include individuals who exhibit very low probabilities in leadership and influence-related items, often avoiding or feeling discomfort with leadership roles. They could be labeled as the "Avoidant or Leadership-Discomfort Group."

The finding that in Cambodia, students mostly belong to the "Reserved or Lack of Self-Confidence Group" in the two-class model, and predominantly to the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group" in the three-class model suggests that Cambodian students tend to exhibit more reserved or moderate tendencies regarding leadership situations. Analyzing the distributions for Guatemala and Paraguay, while there is roughly equal distribution in the two-class model in both countries, the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group" and the "Strong Leaders or Influential Group" are more pronounced in the three-class model. This indicates a greater variety of tendencies in leadership and influence among individuals in these countries. Examining the distributions for Peru reveals that almost all students are part of the "Active Leaders or Influential Group" in the two-class model and the "Strong Leaders or Influential Group" in the three-class model. This suggests a tendency for students in Peru to be highly active and influential in leadership matters. These interpretations of research findings suggest that latent classes may vary across countries and that specific cultural or societal factors may influence these tendencies.

This finding aligns with the findings of the GLOBE project, which examined the relationship between culture and leadership across 25 different societies. The project revealed significant differences in leadership preferences across cultures (Cai et al., 2018). Additionally, the GLOBE project highlighted the emergence of different leadership styles in different cultures (Chhokar et al., 2008), a phenomenon supported by various studies (Atasoy & Çoban, 2021; Brand et al., 2022; Janićijević, 2019; Ly, 2020; Malmir et al., 2013). Moreover, these findings are consistent with the theoretical assumptions of Role Theory and Situational Approach (Cuaresma-Escobar, 2021; Jogulu, 2010; Warner, 2012).

In Guatemala, which has a long history of civil war and violence, the military held power for many years, and subsequently, the democratic governments that were established were also associated with incidents such as human rights violations and corruption. Despite democratically elected governments being in power today, the governance is characterized by a fragile structure due to the high likelihood of elites seizing control of the state administration (Congressional Research Service, 2023). In contrast, Cambodia is classified as a patrimonial or neo-patrimonial state, emphasizing the prevalence of patron-client relationships that extend from the top of the government in a complex pyramidal structure to distant villages. In other words, this country can be considered as a combination of dynastic governance and modern nation-states (Croissant, 2008). On the other hand, Peru, governed by a presidential system and possessing a democratic system (Miş et al., 2016), is observed to be attempting to adopt neo-positivist ideals such as modernization and innovation with the support of the United States (Palmer, 2019). Another country governed by a presidential system is Paraguay (Bağce, 2017). Despite stable growth in the country, there is a noticeable high level of inequality (Beittel, 2017).

The profiles outlined above regarding the countries provide some clues about the leadership profiles of students in the PISA results. Accordingly, individuals in the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group" in Cambodia, where dynastic rule still exists, may be associated with the country's governance structure. On the other hand, the unequal structure in Paraguay and Guatemala, where democracy has not been fully established, may influence the distribution of students' leadership profiles between the "Moderate or Passive Leader Group" and the "Strong Leader or Influential Group." Additionally, in Peru, which is progressing towards becoming a democratic country with the support of the United States, it is believed that students' placement in the "Active Leader or Influential Group" within their leadership profiles is not coincidental. In conclusion, it can be inferred that students in Cambodia, Guatemala, Paraguay, and Peru exhibit different leadership profiles, influenced by the diverse management styles and cultural structures of these countries.

In this study, we examined whether students exhibit different leadership profiles based on the PISA 2022 data and whether these profiles vary across countries with different governance styles and cultures. Regarding leadership profiles, we found that students in two-class models display different characteristics, such as "Shy or Lack of Confidence Group" and "Active Leader or Influential Group," while in three-class models, they exhibit traits such as "Moderate or Passive Leader Group," "Strong Leader or Influential Group," and "Avoidant or Discomfort with Leadership Group." Additionally, we identified variations in the leadership profiles of students in Guatemala, Cambodia, Paraguay, and Peru samples. These findings underscore the significance of the culture-leadership relationship and highlight the necessity of blending globally recognized leadership approaches with local characteristics on a global scale.

6. Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is the restriction of the sample to Guatemala, Cambodia, Paraguay, and Peru. The primary reason for selecting these countries is their similarity in various aspects such as population, level of development, and academic performance of students, while differing in terms of their management styles. However, when the study is replicated across the 81 countries included in the PISA sample, different variables may come into play, posing a risk to isolating student leadership profiles from these variables. Another limitation of the study is its reliance on PISA data. While researchers could have designed such a study by developing a new measurement tool or identifying variables directly, conducting such a study on an international scale might have been economically and logistically unfeasible in terms of time, cost, and access. Despite appearing as limitations, these two aspects are quite reasonable in terms of practical implementation. The information obtained in this research is considered valuable in laying the groundwork for more comprehensive studies or serving as a precursor to further research.

7. Practical Implications

Our findings can be used to develop a "universal student leadership" model for educational programs. Our research has revealed that students' leadership characteristics may vary depending on the community they are part of and the governance model of that community. Accordingly, while some students exhibit strong leadership qualities, it has been determined that others demonstrate hesitant or leadership-avoidant traits. However, students' leadership skills are critically important for their ability to assume responsibility in the future, take on specific tasks, and manage crises that may arise in their personal and professional lives. In this regard, developing students' leadership profiles in education systems aimed at fostering future generations to take responsibility and advance their countries is an important goal. Therefore, the results of our research can serve as a reference for the development of educational programs aimed at imparting universally applicable leadership skills beyond local leadership concepts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. D., and M.S.; Methodology, F. C..; Software, F.C.; Validation, F. C., and M.D..; Formal Analysis, F.C.; Investigation, D.G..; Resources, D.G.; Data Curation, M.D.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.S.; Visualization, F.C.; Supervision, M.S.; Project Administration, D.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Since this research was not conducted directly on humans or animals, ethics committee permission was not obtained. In the realization of the research, data were obtained from the PISA 2022 report.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adıgüzel, Z., Özçinar, M. F., & Karadal, H. (2020). Otoriter liderliğin üretim sektöründe bulunan çalışanlar üzerindeki etkisinin incelenmesi. Turkish Studies-Social Sciences, Volume 15 Issue 1(Volume 15 Issue 1), 15-35. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A. (2021). The impact of leadership on good governance in post civil war in Somalia. International Social Mentality and Researcher Thinkers Journal, 7(51), 2488-2494.

- AlKaabi, N. A., Al-Maadeed, N., Romanowski, M. H., & Sellami, A. (2022). Drawing lessons from PISA: Qatar’s use of PISA results. PROSPECTS, 1-20.

- Amir, J., Dalle, A., Dj, S., & Irmawati, I. (2023). PISA Assessment on Reading Literacy Competency: Evidence from Students in Urban, Mountainous and Island Areas. Jurnal Kependidikan: Jurnal Hasil Penelitian dan Kajian Kepustakaan di Bidang Pendidikan, Pengajaran dan Pembelajaran, 9(1), 107-120.

- Araujo, L., Saltelli, A., & Schnepf, S. V. (2017). Do PISA data justify PISA-based education policy?. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 19(1), 20-34.

- Arun, K., & Kahraman Gedik, N. (2022). Impact of Asian cultural values upon leadership roles and styles. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 88(2), 428-448.

- Atasoy, R., & Çoban, Ö. (2021). Leadership map of seven countries according to TALIS 2018. International Journal of Eurasian Education and Culture, 6(14), 2166-2193.

- Ayman, R., Chemers, M. M., & Fiedler, F. (2007). The contingency model of leadership effectiveness: Its levels of analysis. In R. P. Vecchio (Ed.), Leadership: Understanding the dynamics of power and influence in organizations (2nd ed., pp. 335–360). University of Notre Dame Press. [CrossRef]

- Bağce, H.E. (2017). Parlamenter ve başkanlık sistemiyle yönetilen ülkelerde gelir dağılımı eşitsizliği ve yoksulluk. İnsan ve İnsan, 4(11), 5-39.

- Barański, M. (2020). The political party system in slovakia in the era of mečiarism. the experiences of the young democracies of central european countries. Eastern Review, 9, 33-48. [CrossRef]

- Barthold, C., Checchi, M., Imas, J. M., & Jones, O. S. (2020). Dissensual leadership: rethinking democratic leadership with jacques rancière. Organization, 29(4), 673-691. [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. (1997), “Does the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries?”, American Psychologist, Vol. 52 No. 2, pp. 130-139.

- Bayraktar, S., Karacay, G., Dastmalchian, A., & Kabasakal, H. (2022). Organizational culture and leadership in Egypt, Iran, and Turkey: The contextual constraints of society and industry. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, 39(4), 413-431.

- Beittel, J.S. (2017). Paraguay: In Brief. Congressional Research Service.

- Białecki, I., Jakubowski, M., & Wiśniewski, J. (2017). Education policy in Poland: The impact of PISA (and other international studies). European Journal of Education, 52(2), 167-174.

- Biddle, B. (1979). Role theory: Expectations, identities and behaviours. Academic Press.

- Black, R., Walsh, L., Magee, J., Hutchins, L., Berman, N., & Groundwater-Smith, S. (2014). Student leadership: a review of effective practice. Canberra: ARACY.

- Bowler, S., & Donovan, T. (2002). Democracy, institutions and attitudes about citizen influence on government. British Journal of Political Science, 32(2), 371-390.

- Brandt, T., Wanasika, I., & Laiho, M. (2022, November). Cultural differences in communication and leadership–A comparison of Finland, Indonesia and USA. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance ECMLG 2022. Academic publishing international.

- Bush, T., & Glover, D. (2014). School leadership models: What do we know?. School Leadership & Management, 34(5), 553-571.

- Cai, M., Humphrey, R. H., & Qian, S. (2018). A cross-cultural meta-analysis of how leader emotional intelligence influences subordinate task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of World Business, 53(4), 463-474. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L. M., Costa, E., & Gonçalves, C. (2017). Fifteen years looking at the mirror: On the presence of PISA in education policy processes (Portugal, 2000-2016). European Journal of Education, 52(2), 154-166.

- Chhokar, J., Brodbeck, F., & House, R. Culture And Leadership, Across The World: The Globe Book Of In-Depth Studies Of 25 Societies. Routledge.

- Cho, Y. (2014). To know democracy is to love it: A cross-national analysis of democratic understanding and political support for democracy. Political Research Quarterly, 67(3), 478-488.

- Chong, M. P., Shang, Y., Richards, M., & Zhu, X. (2018). Two sides of the same coin? Leadership and organizational culture. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39(8), 975-994.

- Collard, J. (2007). Constructing theory for leadership in intercultural contexts. Journal of Educational Administration, 45(6), 740-755.

- Congressional Research Service (2023, December 28). Congressional Research Service. In Focus. Available online: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF12340.pdf.

- Croissant, A. (2008). The perils and promises of democratization through united nations transitional authority – lessons from cambodia and east timor. Democratization, 15(3), 649-668. [CrossRef]

- Cuaresma-Escobar, K.J. (2021). Nailing the situational leadership theory by synthesizing the culture and nature of principals' leadership and roles in school. Linguistics and Culture Review, 5(S3), 319-328.

- Day, C., Sammons, P., & Gorgen, K. (2020). Successful school leadership. Education Development Trust.

- Dimmock, C., & Walker, A. (2005). A cultural approach to leadership: methodological issues. In Educational Leadership: Culture and Diversity (pp. 43-62). SAGE Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, M., & Martens, K. (2012). Towards an education approach à la finlandaise? French education policy after PISA. Journal of education policy, 27(1), 23-43.

- Dorfman, P. W., Howell, J. P., Hibino, S., Lee, J. K., Tate, U., & Bautista, A. (1997). Leadership in Western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. The Leadership Quarterly, 8(3), 233-274.

- Dwairy, M. (2019). Culture and leadership: Personal and alternating values within inconsistent cultures. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 22(4), 510-518.

- Educational Testing Service. (2021). Computer-Based Student Questionnaire for PISA 2022: Main Survey Version [PDF dosyası]. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2022database/CY8_202111_QST_MS_STQ_CBA_NoNotes.pdf.

- Eich, D. (2008). A grounded theory of high-quality leadership programs: Perspectives from student leadership programs in higher education. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 15(2), 176–187.

- Eisenberg, J., Pieczonka, A., Eisenring, M., & Mironski, J. (2015). Poland, a workforce in transition: Exploring leadership styles and effectiveness of Polish vs. Western expatriate managers. Journal of East European Management Studies, 435-451.

- Euwema, M. C., Wendt, H., & Van Emmerik, H. (2007). Leadership styles and group organizational citizenship behavior across cultures. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 28(8), 1035-1057.

- Fischer, R., Ferreira, M. C., Assmar, E. M. L., Baris, G., Berberoglu, G., Dalyan, F., … & Boer, D. (2014). Organizational practices across cultures: An exploration in six cultural contexts. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 14(1), 105-125.

- Flessa, J., Bramwell, D., Fernandez, M., & Weinstein, J. (2018). School leadership in Latin America 2000–2016. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(2), 182-206.

- Frederiksen, K.V.S. (2022). Does Competence Make Citizens Tolerate Undemocratic Behavior?. American Political Science Review, 116(3), 1147-1153.

- Gao, X. (2021). Staying in the Nationalist Bubble: Social Capital, Culture Wars, and the COVID-19 Pandemic. M/C Journal, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Garrison, W.H. (2003). Democracy, experience, and education: Promoting a continued capacity for growth. Phi Delta Kappan, 84(7), 525-529.

- Gastil, J. (1994). A definition and illustration of democratic leadership. Human relations, 47(8), 953-975.

- Gott, T., Bauer, T., & Long, K. (2019). Student leadership today, professional employment tomorrow. New directions for student leadership, 2019(162), 91-109.

- Green, B.F. (1952). Latent structure analysis and its relation to factor analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 47(257), 71-76.

- Gutierrez, B., Spencer, S. M., & Zhu, G. (2012). Thinking globally, leading locally: Chinese, Indian, and Western leadership. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 19(1), 67-89.

- Gümüş, S., Şükrü Bellibaş, M., Şen, S., & Hallinger, P. (2024). Finding the missing link: Do principal qualifications make a difference in student achievement?. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 52(1), 28-51.

- Hagenaars, J. A., & McCutcheon, A. L. (2002). Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 4(3), 221-239. [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S., Freeman, B., & Tickner, A. (2017). How Connected Leadership Helps to Create More Agile and Customer-Centric Organizations in Asia. The Palgrave Handbook of Leadership in Transforming Asia, 71-87.

- Hoffman, S. J., Rosenfield, D., Gilbert, J. H., & Oandasan, I. F. (2008). Student leadership in interprofessional education: benefits, challenges and implications for educators, researchers and policymakers. Medical Education, 42(7), 654-661.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hong, G., Cho, Y., Froese, F.J. and Shin, M. (2016), “The effect of leadership styles, rank, and seniority on affective organizational commitment: a comparative study of US and Korean employees”, Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 340-362.

- Hopfenbeck, T. N., & Kjærnsli, M. (2016). Students’ test motivation in PISA: The case of Norway. The Curriculum Journal, 27(3), 406-422.

- Horng, E., & Loeb, S. (2010). New thinking about instructional leadership. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(3), 66-69.

- Hulpia, H., & Devos, G. (2010). How distributed leadership can make a difference in teachers' organizational commitment? A qualitative study. Teaching and teacher education, 26(3), 565-575.

- Janićijević, N. (2019). The impact of national culture on leadesrhip in socety and organizations: why do serbs love authoritarian leaders. Proceedings of the 5th Arts & Humanities Conference, Copenhagen. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.M. (2013). Exploring instructional strategies in student leadership development programming. Journal of leadership studies, 6(4), 48-62.

- Jerrim, J., & Moss, G. (2019). The link between fiction and teenagers’ reading skills: International evidence from the OECD PISA study. British Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 181-200.

- Jerrim, J., Lopez-Agudo, L. A., & Marcenaro-Gutierrez, O. D. (2022). The impact of test language on PISA scores. New evidence from Wales. British Educational Research Journal, 48(3), 420-445.

- Jogulu, U.D. (2010). Culturally-linked leadership styles. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 31(8), 705-719.

- Keenan, O. and Zavala, A. G. D. (2021). Collective narcissism and the weakening of american democracy. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Y. and Park, J. H. (2020). South korean humanistic leadership. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 27(4), 589-605. [CrossRef]

- Lanza, S. T., Collins, L. M., Lemmon, D. R., & Schafer, J. L. (2007). PROC LCA: A SAS Procedure for Latent Class Analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 671-694.

- Lavonen, J., & Laaksonen, S. (2009). Context of teaching and learning school science in Finland: Reflections on PISA 2006 results. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 46(8), 922-944.

- Li, P. and Wang, H. (2015). Study on authoritarian leader-member relationship. Journal of US-China Public Administration, 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Lok, P., & Crawford, J. (2004). The effect of organisational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and organisational commitment: A cross-national comparison. Journal of management development, 23(4), 321-338.

- Ly, N.B. (2020). Cultural influences on leadership: Western-dominated leadership and non-Western conceptualizations of leadership. Sociology and Anthropology, 8(1), 1-12.

- Maheshwari, G., Nayak, R., & Ngyyen, T. (2021). Review of research for two decades for women leadership in higher education around the world and in vietnam: a comparative analysis. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 36(5), 640-658. [CrossRef]

- Malmir, M., Esfahani, M. J., & Emami, M. (2013). An investigation on leadership styles in different cultures. Management Science Letters, 1491-1496. [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. (2017). Cultures of Educational Leadership: Researching and Theorising Common Issues in Different World Contexts. In: Miller, P. (eds) Cultures of Educational Leadership. Intercultural Studies in Education. Palgrave Macmillan, London. [CrossRef]

- Miş, N., Aslan, A., Duran, H., & Ayvaz, M. E. (2016, April). Dünyada Başkanlık Sistemi Uygulamaları [2. Baskı]. Seta.

- Niemann, D., Martens, K., & Teltemann, J. (2017). PISA and its consequences: Shaping education policies through international comparisons. European Journal of Education, 52(2), 175-183.

- Nilsen, T., & Teig, N. (2022). A systematic review of studies investigating the relationships between school climate and student outcomes in TIMSS, PISA, and PIRLS. International Handbook of Comparative Large-Scale Studies in Education: Perspectives, Methods and Findings, 1-34.

- OECD (2023a), PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2023b), PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Learning During – and From – Disruption, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023c). PISA 2022 Database. OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2022database/ (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Oyserman, D., Sorensen, N., Reber, R., & Chen, S. X. (2009). Connecting and separating mind-sets: culture as situated cognition. Journal of personality and social psychology, 97(2), 217.

- Palmer, D.S. (2019). Peru: Democratic Forms, Authoritarian Practices. In Latin American Politics And Development, Fifth Edition (pp. 228-258). Routledge.

- Passini, S., & Morselli, D. (2010). Disobeying an illegitimate request in a democratic or authoritarian system. Political Psychology, 31(3), 341-355.

- Polzer, J.T. (2015). Role theory. Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, 1-1.

- Pont, B., Moorman, H., & Nusche, D. (2008). Improving school leadership (Vol. 1, p. 578). Paris: OECD.

- Quiroz-Niño, C., & Blanco-Encomienda, F. J. (2019). Participation in decision-making processes of community development agents: a study from Peru. Community Development Journal, 54(2), 329-351.

- Rautalin, M., Alasuutari, P., & Vento, E. (2019). Globalisation of education policies: Does PISA have an effect?. Journal of Education Policy, 34(4), 500-522.

- Resick, C. J., Martin, G. S., Keating, M. A., Dickson, M. W., Kwan, H. K., & Peng, C. (2011). What ethical leadership means to me: Asian, American, and European perspectives. Journal of business ethics, 101, 435-457.

- Rizzo, H., Abdel-Latif, A., & Meyer, K. (2007). The relationship between gender equality and democracy: a comparison of arab versus non-arab muslim societies. Sociology, 41(6), 1151-1170. [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T. D., & Zeidler, D. L. (2009). Scientific literacy, PISA, and socioscientific discourse: Assessment for progressive aims of science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 46(8), 909-921.

- Sampaio Maia, J., Rosa, V., Mascarenhas, D., & Duarte Teodoro, V. (2022). Comparative indices of the education quality from the opinions of teachers and principals in TALIS 2018. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2153418.

- Sanchez-Runde, C., Nardon, L., & Steers, R. M. (2011). Looking beyond Western leadership models: Implications for global managers. Organizational dynamics, 40(3), 207-213.

- Schleicher, A., & Zoido, P. (2016). The policies that shaped PISA, and the policies that PISA shaped. The handbook of global education policy, 374-384.

- Schwarz, G. E. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461-464.

- Seemiller, C. (2016). Assessing student leadership competency development. New directions for student leadership, 2016(151), 51-66.

- Sekulova, F., Anguelovski, I., Argüelles, L., & Conill, J. (2017). A ‘fertile soil’ for sustainability-related community initiatives: a new analytical framework. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(10), 2362-2382. [CrossRef]

- Sellar, S., & Lingard, B. (2013). Looking East: Shanghai, PISA 2009 and the reconstitution of reference societies in the global education policy field. Comparative Education, 49(4), 464-485.

- Shahin, A. I., & Wright, P. L. (2004). Leadership in the context of culture: An Egyptian perspective. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(6), 499-511.

- Shan, G., Wang, W., Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Guo, S., & Li, Y. (2022). Authoritarian leadership and nurse presenteeism: the role of workload and leader identification. [CrossRef]

- Shivers-Blackwell, S.L. (2004). Using role theory to examine determinants of transformational and transactional leader behavior. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 10(3), 41-50.

- Simonovits, G., McCoy, J., & Littvay, L. (2022). Democratic hypocrisy and out-group threat: explaining citizen support for democratic erosion. The Journal of Politics, 84(3), 1806-1811.

- Spreitzer, G. (2007). Giving peace a chance: Organizational leadership, empowerment, and peace. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 28(8), 1077-1095.

- Stacey, K. (2011). The PISA View of Mathematical Literacy in Indonesia. Indonesian Mathematical Society Journal on Mathematics Education, 2(2), 95-126.

- Stowers, K., Hancock, G. M., Neigel, A. R., Cha, J., Chong, I., Durso, F. T., … & Summers, B. I. (2019). Heforshe in hfe: strategies for enhancing equality in leadership for all allies. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 63(1), 622-624. [CrossRef]

- Taldykin, O. (2021). Atypical titles and ranks of heads of state as part of the personality cult. Naukovyy Visnyk Dnipropetrovs'kogo Derzhavnogo Universytetu Vnutrishnikh Sprav, 1(1), 89-98. [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, G., Salmani, D., & Taatian, A. (2010). Survey of leadership styles in different cultures. Iranian Journal of management studies, 3(3), 91-111.

- Tasaki, N. (2017). The impact of OECD-PISA results on Japanese educational policy. European Journal of Education, 52(2), 145-153.

- Teig, N., Scherer, R., & Kjærnsli, M. (2020). Identifying patterns of students' performance on simulated inquiry tasks using PISA 2015 log-file data. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(9), 1400-1429.

- Teig, N., Scherer, R., & Olsen, R. V. (2022). A systematic review of studies investigating science teaching and learning: over two decades of TIMSS and PISA. International Journal of Science Education, 44(12), 2035-2058.

- Van de Vliert, E. (2008). Climate, affluence, and culture. Cambridge University Press.

- Velarde, J. M. and Ghani, M. F. A. (2019). International school leadership in malaysia: exploring teachers’ perspectives on leading in a culturally diverse environment. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Management, 7(2), 27-45. [CrossRef]

- Waldow, F. (2009). What PISA did and did not do: Germany after the ‘PISA-shock’. European Educational Research Journal, 8(3), 476-483.

- Wang, H., Waldman, D. A., & Zhang, H. (2012). Strategic leadership across cultures: Current findings and future research directions. Journal of world business, 47(4), 571-580.

- Warner, M. (2012). Culture and leadership across the world: the globe book of in-depth studies of 25 societies. Asia Pacific Business Review, 18(1), 123-124. [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.A. (2004). Democratic leadership: drawing distinctions with distributed leadership. International journal of leadership in education, 7(1), 3-26.

- Woodward, S., Romera, Á. J., Beskow, W. B., & Lovatt, S. J. (2008). Better simulation modelling to support farming systems innovation: review and synthesis. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 51(3), 235-252. [CrossRef]

- Wren, J. T. (Ed.). (1995). Leader’s companion: Insights on leadership through the ages. The Free Press.

- Yadav, V. and Fidalgo, A. (2021). The face of the party: party leadership selection, and the role of family and faith. Political Research Quarterly, 75(2), 379-393. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., & Liu, L. (2016). How does ICT use influence students’ achievements in math and science over time? Evidence from PISA 2000 to 2012. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 12(9), 2431-2449.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).