Submitted:

05 July 2024

Posted:

08 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection: Survey

2.2. Data Collection: Questionnaire

2.2.1. Background Information

2.2.2. Willingness to Pay (WTP) Questions

2.2.3. Protest Answers

2.2.4. Views on Sustainable Agricultural Practices Benefits

2.2.5. Views on How Concerned Participants are About Soil Quality Decline

2.2.6. Trust

2.2.7. Risk Attitudes

2.2.8. Time Preferences

2.2.9. Ambiguity Tolerance

2.2.10. Pro-Social Behavior

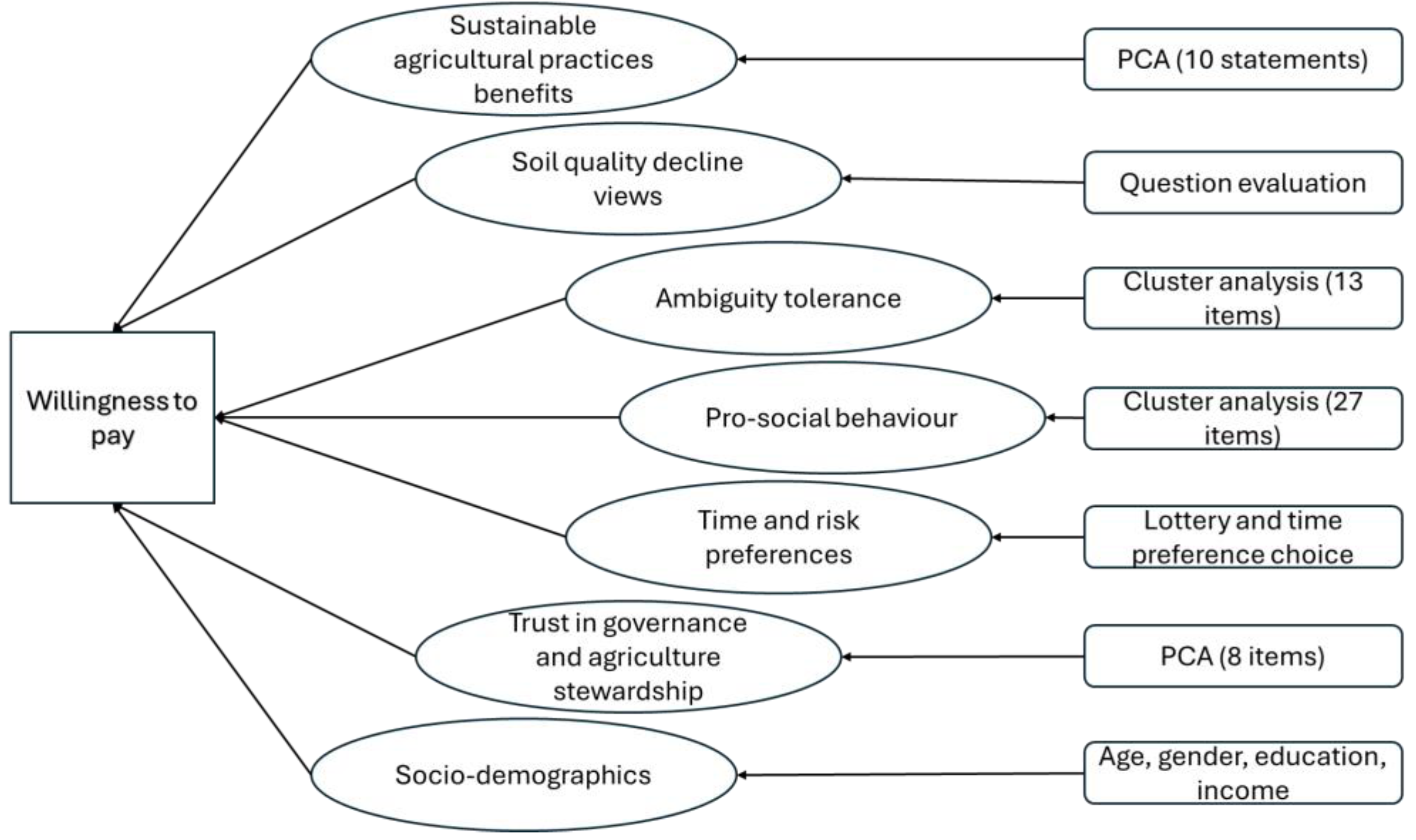

2.3. Conceptualisation of the Analysis

2.4. Data Analysis: Double Bounded Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation

2.5. Data analysis: Model Estimation

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Willingness to Pay: Control And Treatment Models

3.2.1. UK—Willingness to Pay for Agricultural Soil Quality Improvement

3.2.1. Spain—Willingness to Pay for Agricultural Soil Quality Improvement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directorate General for Health and Food Safety, E.C., COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system, in COM(2020)381 final, E. Commission, Editor. 2020, European Commission: Brussels.

- Hessel, R., et al., Soil-Improving Cropping Systems for Sustainable and Profitable Farming in Europe. Land, 2022. 11(6): p. 780. [CrossRef]

- Veerman, C., et al., Caring for soil is caring for life – Ensure 75% of soils are healthy by 2030 for food,.

- people, nature and climate. 2020, European Commission: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4ebd2586-fc85-11ea-b44f-01aa75ed71a1/.

- Agarwal, S.K. and A.K. Srivastava, On probability limits in snowball sampling. Biometrical Journal, 1980. 22(1): p. 87-88. [CrossRef]

- Environment Agency, The state of the evironmnet: soil. 2019, Environment Agency.

- Potter, C. and P. Goodwin, Agricultural liberalization in the European union: an analysis of the implications for nature conservation. Journal of Rural Studies, 1998. 14(3): p. 287-298. [CrossRef]

- Mattison, E.H.A. and K. Norris, Bridging the gaps between agricultural policy, land-use and biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2005. 20(11): p. 610-616. [CrossRef]

- Donald, P.F., R. Green, and M. Heath, Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe's farmland bird populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 2001. 268(1462): p. 25-29. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.D., et al., A review of the abundance and diversity of invertebrate and plant foods of granivorous birds in northern Europe in relation to agricultural change. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 1999. 75(1): p. 13-30. [CrossRef]

- Gasso, V., et al., Controlled traffic farming: A review of the environmental impacts. European Journal of Agronomy, 2013. 48: p. 66-73. [CrossRef]

- Batey, T., Soil compaction and soil management – a review. Soil Use and Management, 2009. 25(4): p. 335-345. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.A. and W.K. Anderson, Soil compaction in cropping systems: A review of the nature, causes and possible solutions. Soil and Tillage Research, 2005. 82(2): p. 121-145. [CrossRef]

- Swinbank, A., Capping the CAP? Implementation of the Uruguay round agreement by the European union. Food Policy, 1996. 21(4): p. 393-407. [CrossRef]

- Hynes, S., et al., Modelling habitat conservation and participation in agri-environmental schemes: A spatial microsimulation approach. Ecological economics, 2008. 66(2-3): p. 258-269. [CrossRef]

- Kutter, T., et al., Policy measures for agricultural soil conservation in the European Union and its member states: Policy review and classification. Land Degradation & Development, 2011. 22(1): p. 18-31. [CrossRef]

- Commission, E., Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on Soil Monitoring and Resilience (Soil Monitoring Law) in COM(2023) 416 final.

- 2023/0232 (COD) 2023, European Commission.

- DEFRA, The Path to Sustainable Farming: An Agricultural Transition Plan 2021 to 2024 2020, DEFRA.

- Commission, E., Common agricultural policy for 2023-2027: 28 CAP strategic plans at a glance. 2022, European Commission.

- European Court of Auditors, EU efforts for sustainable soil management: Unambitious standards and limited targeting. 2023, European Court of Auditors.

- Glenk, K. and S. Colombo, Designing policies to mitigate the agricultural contribution to climate change: an assessment of soil based carbon sequestration and its ancillary effects. Climatic Change, 2011. 105(1): p. 43-66. [CrossRef]

- Franceschinis, C., et al., Society's willingness to pay its way to soil security. Soil Security, 2023. 13: p. 100122. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H., J. Yang, and N. Hao, Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Rice from Remediated Soil: Potential from the Public in Sustainable Soil Pollution Treatment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022. 19(15): p. 8946. [CrossRef]

- Dimal, M.O.R. and V. Jetten, Analyzing preference heterogeneity for soil amenity improvements using discrete choice experiment. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 2020. 22(2): p. 1323-1351. [CrossRef]

- Eusse-Villa, L.F., et al., Attitudes and Preferences towards Soil-Based Ecosystem Services: How Do They Vary across Space? Sustainability, 2021. 13(16): p. 8722. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Entrena, M., et al., Evaluating the demand for carbon sequestration in olive grove soils as a strategy toward mitigating climate change. Journal of Environmental Management, 2012. 112: p. 368-376. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S., N. Hanley, and J. Calatrava-Requena, Designing Policy for Reducing the Off-farm Effects of Soil Erosion Using Choice Experiments. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 2005. 56(1): p. 81-95. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S., J. Calatrava-Requena, and N. Hanley, Analysing the social benefits of soil conservation measures using stated preference methods. Ecological Economics, 2006. 58(4): p. 850-861. [CrossRef]

- Almansa, C., J. Calatrava, and J.M. Martínez-Paz, Extending the framework of the economic evaluation of erosion control actions in Mediterranean basins. Land Use Policy, 2012. 29(2): p. 294-308. [CrossRef]

- Bartkowski, B., J.R. Massenberg, and N. Lienhoop, Investigating preferences for soil-based ecosystem services. Q Open, 2022. 2(2). [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.A. and S.K. Laury, Risk Aversion and Incentive Effects. The American Economic Review, 2002. 92(5): p. 1644-1655. [CrossRef]

- Rieger, M.O. and Y. He-Ulbricht, German and Chinese dataset on attitudes regarding COVID-19 policies, perception of the crisis, and belief in conspiracy theories. Data in Brief, 2020. 33: p. 106384. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., M.O. Rieger, and T. Hens, How time preferences differ: Evidence from 53 countries. Journal of Economic Psychology, 2016. 52: p. 115-135. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, F.P., E. Denny, and P.D. Lunn, Looking beyond time preference: Testing potential causes of low willingness to pay for fuel economy improvements. Resource and Energy Economics, 2023. 75: p. 101404. [CrossRef]

- Julia Ihli, H., et al., Risk and time preferences for participating in forest landscape restoration: The case of coffee farmers in Uganda. World Development, 2022. 150: p. 105713. [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, D., Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1961. 75(4): p. 643-669. [CrossRef]

- McLain, D.L., Evidence of the Properties of an Ambiguity Tolerance Measure: The Multiple Stimulus Types Ambiguity Tolerance Scale–II (MSTAT–II). Psychological Reports, 2009. 105(3): p. 975-988. [CrossRef]

- Jorge, E., E. Lopez-Valeiras, and M.B. Gonzalez-Sanchez, The role of attitudes and tolerance of ambiguity in explaining consumers’ willingness to pay for organic wine. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020. 257: p. 120601. [CrossRef]

- Rapert, M.I., A. Thyroff, and S.C. Grace, The generous consumer: Interpersonal generosity and pro-social dispositions as antecedents to cause-related purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 2021. 132: p. 838-847. [CrossRef]

- ONS, Population estimates for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland: mid2022. 2024, Office for National Statistics.

- INE. Estadística continua de Población (ECP). 2024 28/06/2024].

- Shee, A., C. Azzarri, and B. Haile Farmers’ Willingness to Pay for Improved Agricultural Technologies: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Tanzania. Sustainability, 2020. 12. [CrossRef]

- Farsi, M., Risk aversion and willingness to pay for energy efficient systems in rental apartments. Energy Policy, 2010. 38(6): p. 3078-3088. [CrossRef]

- Elabed, G. and M.R. Carter, Compound-risk aversion, ambiguity and the willingness to pay for microinsurance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2015. 118: p. 150-166. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S., et al., Does risk preference matter to consumers’ willingness to pay for functional food: Evidence from lab experiments using the eye-tracking technology. Food Quality and Preference, 2024. 119: p. 105197. [CrossRef]

| Soil improving cropping system component | Description |

|---|---|

| Cover crops, green manures & intercropping | Help keep ground covered over winter when rain and winds can cause erosion; can reduce need for fertilizer and supply organic N if leguminous; create habitat for insects and therefore food for birds. |

| Crop rotation | Rotating crops with a diverse mix of crops as well as livestock, can increase soil health infiltration through different root lengths by adding a range of nutrients therefore reducing the need for chemical inputs, improving soil structure and reducing the need for chemical pest and weed control. |

| Fertilization / soil amendments | Adding compost, mulch, woodchip (fresh or composted) and animal manure reduce the need for chemical fertilizers |

| Soil cultivation | Reducing or eliminating the amount of ploughing or tillage of the soil can improve soil health by reducing organic matter decline, keeping soil microbiology intact and reduce compaction through less machine passes across fields as well as reducing fuel use and related emissions. |

| Compact alleviation | Sub-soiling can be used to alleviate compaction (increasing infiltration and soil health), as well as using diverse cover crops, (the roots of which can help aerate soil and improve structure), and reducing machinery passes across fields e.g. reducing tillage. |

| Controlled drainage | Re-use of water on farm; ditches etc to allow run-off; afforestation to reduce waterlogging. Improves crop productivity and resource use efficiency; minimizes the risk of waterlogging. |

| Integrated landscape management | Mixed farming and rotations across farms; hedgerows and corridors for wildlife and beneficial predators; water harvesting e.g. through dams, reservoirs. Improves biodiversity, pest management and cropping systems sustainability on a landscape-scale. |

| Statement | |

|---|---|

| 1 | I cannot pay. I do not have enough income |

| 2 | I will need to have more information about this policy |

| 3 | I am skeptical the money will go to farmers |

| 4 | I am already paying tax and I think the government has to use that money to support farmers |

| 5 | It is unfair for me to pay |

| 6 | I object to the way the question is asked |

| 7 | The money collected will not make a difference |

| 8 | My employment is temporary, uncertain; therefore my commitment cannot be long term |

| 9 | Other, please state |

| Statement | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Creating habitat for insects and therefore food for birds |

| 2 | Improving soil health and structure |

| 3 | Reducing the need for chemical pest and weed control |

| 4 | Reducing fuel use and related emissions |

| 5 | Improving water use efficiency |

| 6 | Minimizing risks of salinization and desertification |

| 7 | Improving crop productivity |

| 8 | Minimizing the risk of waterlogging |

| 9 | Improving biodiversity |

| 10 | Improving cropping system sustainability |

| Option A | Option B | Expected payoff difference |

|---|---|---|

| 10% chance wining £2.00 and 90% wining £1.60 | 10% chance wining £3.85 and 90% wining £0.10 | £/€1.17 |

| 20% chance wining £2.00 and 80% wining £1.60 | 20% chance wining £3.85 and 80% wining £0.10 | £/€0.83 |

| 30% chance wining £2.00 and 70% wining £1.60 | 30% chance wining £3.85 and 70% wining £0.10 | £/€0.50 |

| 40% chance wining £2.00 and 60% wining £1.60 | 40% chance wining £3.85 and 60% wining £0.10 | £/€0.16 |

| 50% chance wining £2.00 and 50% wining £1.60 | 50% chance wining £3.85 and 50% wining £0.10 | -£/€0.18 |

| 60% chance wining £2.00 and 40% wining £1.60 | 60% chance wining £3.85 and 40% wining £0.10 | -£/€0.51 |

| 70% chance wining £2.00 and 30% wining £1.60 | 70% chance wining £3.85 and 30% wining £0.10 | -£/€0.85 |

| 80% chance wining £2.00 and 20% wining £1.60 | 80% chance wining £3.85 and 20% wining £0.10 | -£/€1.18 |

| 90% chance wining £2.00 and 10% wining £1.60 | 90% chance wining £3.85 and 10% wining £0.10 | -£/€1.52 |

| 100% chance wining £2.00 and 0% wining £1.60 | 100% chance wining £3.85 and 0% wining £0.10 | -£/€1.85 |

| Statement | |

|---|---|

| 1 | I don't tolerate ambiguous situations well |

| 2 | I would rather avoid solving a problem that must be viewed from several different perspectives |

| 3 | I try to avoid situations that are ambiguous |

| 4 | I prefer familiar situations to new ones |

| 5 | Problems that cannot be considered from just one point of view are a little threatening |

| 6 | I avoid situations that are too complicated for me to easily understand |

| 7 | I am tolerant of ambiguous situations |

| 8 | I enjoy tackling problems that are complex enough to be ambiguous |

| 9 | I try to avoid problems that don’t seem to have only one “best” solution |

| 10 | I generally prefer novelty over familiarity |

| 11 | I dislike ambiguous situations |

| 12 | I find it hard to make a choice when the outcome is uncertain |

| 13 | I prefer a situation in which there is some ambiguity |

| Statement | |

|---|---|

| 1 | I would feel less bothered about leaving litter in a dirty park than in a clean one |

| 2 | Depending on what a person has done, there may be an excuse for taking advantage of them |

| 3 | With the pressure of grades and the widespread cheating in school nowadays, the individual who cheats occasionally is not really as much at fault |

| 4 | It doesn’t make much sense to be very concerned about how we act when we are sick and feeling miserable |

| 5 | If I broke a machine through mishandling, I would feel less guilty if it was already damaged before I used it |

| 6 | When you have a job to do, it is impossible to look out for everyone’s best interest |

| 7 | When I see someone being taken advantage of, I feel kind of protective towards them |

| 8 | Other people’s misfortunes usually disturb me a great deal |

| 9 | When I see someone being treated unfairly, I usually feel pity for them |

| 10 | I am often quite touched by things that I see happen |

| 11 | I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me |

| 12 | I often feel very sorry for other people when they are having problems |

| 13 | I would describe myself as a pretty soft-hearted person |

| 14 | My decisions are usually based on my concern for other people |

| 15 | I choose a course of action that maximizes the help other people receive |

| 16 | My decisions are usually based on concern for the welfare of others |

| 17 | I choose alternatives that minimize the negative consequences to other people |

| 18 | I have helped carry a stranger’s belongings (e.g., books, packages, groceries, etc.) |

| 19 | I have let a neighbor whom I didn’t know too well borrow an item of some value (e.g., tools, a dish, etc.) |

| 20 | I have, before being asked, voluntarily looked after a neighbour’s pet or children without being paid for it |

| 21 | I have offered to help a handicapped or elderly stranger (e.g., to cross a street, to lift something, etc.) |

| 22 | When one of my loved ones needs my attention, I really try to slow down and give them the time and help they need |

| 23 | I am known by family and friends as someone who makes time to pay attention to other’s problems |

| 24 | I'm the kind of person who is willing to go the “extra mile” to help take care of my friends, relatives, and acquaintances |

| 25 | When friends or family members experience something upsetting or discouraging, I make a special point of being kind to them |

| 26 | It makes me very happy to give to other people in ways that meet their needs |

| 27 | I make it a point to let my friends and family know how much I love and appreciate them |

| UK – control (n=449) | UK – treatment (n=433) |

ESP – control (n=462) | ESP – treatment (n=448) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (std dev) | Mean (std dev) | Mean (std dev) | Mean (std dev) |

| SAP benefits | 7.993 (1.530) | 8.031 (1.654) | 8.404 (1.381) | 8.375 (1.375) |

| Soil quality concern | 0.744 (0.437) | 0.736 (0.442) | 0.907 (0.291) | 0.920 (0.272) |

| Ambiguity tolerance | 0.492 (0.500) | 0.416 (0.493) | 0.444 (0.497) | 0.426 (0.495) |

| Pro-social behavior - high | 0.565 (0.497) | 0.515 (0.500) | 0.584 (0.493) | 0.581 (0.494) |

| Pro-social behavior - low | 0.437 (0.497) | 0.485 (0.500) | 0.419 (0.493) | 0.420 (0.494) |

| Risk aversion | 6.933 (2.305) | 6.952 (2.370) | 6.394 (2.487) | 6.469 (2.383) |

| Time preference | 0.759 (0.428) | 0.733 (0.443) | 0.571 (0.495) | 0.583 (0.494) |

| Trust in governance | 2.874 (2.030) | 3.145 (2.313) | 2.524 (2.010) | 2.641 (2.199) |

| Trust in stewardship | 4.606 (1.830) | 4.962 (1.873) | 5.124 (1.859) | 5.452 (2.030) |

| Age | 46.909 (15.816) | 45.951 (15.642) | 42.982 (13.619) | 42.728 (13.317) |

| Gender | 0.508 (0.500) | 0.494 (0.501) | 0.487 (0.500) | 0.520 (0.500) |

| Education level – Primary/Secondary | 0.256 (0.437) | 0.296 (0.457) | 0.297 (0.457) | 0.261 (0.440) |

| Education level – University/Professional | 0.254 (0.436) | 0.233 (0.423) | 0.271 (0.445) | 0.277 (0.448) |

| Education level – Post-graduate degree | 0.490 (0.500) | 0.471 (0.500) | 0.433 (0.496) | 0.462 (0.499) |

| Income | 37,895 (23,262) | 40,471 (26,185) | 29,437 (20,535) | 29,218 (20,482) |

| UK – control | UK – treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coeff. (std dev) | p-value | Coeff. (std dev) | p-value |

| Constant | 12.686 (6.006) | 0.035 | 6.836 (6.735) | 0.310 |

| SAP benefits | 1.485 (0.545) | 0.006 | 1.570 (0.577) | 0.007 |

| Soil quality concern | 6.698 (1.778) | 0.000 | 3.524 (2.089) | 0.092 |

| Ambiguity tolerance | -3.331 (1.415) | 0.019 | -2.631 (1.609) | 0.102 |

| Pro-social behavior - high | 2.436 (1.565) | 0.120 | 0.067 (1.725) | 0.699 |

| Risk aversion | -0.284 (0.316) | 0.320 | -0.660 (0.348) | 0.058 |

| Time preference | -2.021 (1.566) | 0.197 | -4.615 (1.850) | 0.013 |

| Trust in governance | 0.397 (0.399) | 0.320 | 0.462 (0.466) | 0.322 |

| Trust in stewardship | 0.147 (0.472) | 0.755 | 0.794 (0.588) | 0.177 |

| Age | -0.149 (0.046) | 0.001 | -0.102 (0.055) | 0.064 |

| Gender | -2.076 (1.489) | 0.046 | -0.641 (1.651) | 0.698 |

| Education level – University/Professional | 0.691 (1.943) | 0.722 | 1.834 (2.194) | 0.403 |

| Education level – Post-graduate degree | 1.718 (1.759) | 0.329 | 2.557 (1.938) | 0.187 |

| Income | 9.3E-5 (3.2E-5) | 0.004 | 7.3E-5 (3.4E-5) | 0.030 |

| n | 449 | 433 | ||

| Log-likelihood | -631.628 | -682.096 | ||

| LR chi2 | 85.85 | 68.72 | ||

| Spain – control | Spain – treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coeff. (std dev) | p-value | Coeff. (std dev) | p-value |

| Constant | 9.887 (6.429) | 0.124 | -2.034 (6.899) | 0.768 |

| SAP benefits | 1.483 (0.695) | 0.033 | 1.898 (0.714) | 0.008 |

| Soil quality concern | 5.432 (3.054) | 0.075 | 3.571 (3.180) | 0.261 |

| Ambiguity tolerance | 0.340 (1.657) | 0.837 | 2.096 (1.639) | 0.201 |

| Pro-social behavior - high | 4.287 (1.779) | 0.016 | 1.732 (1.815) | 0.340 |

| Risk aversion | 0.185 (0.327) | 0.572 | -0.023 (0.346) | 0.947 |

| Time preference | -0.376 (1.637) | 0.818 | -0.661 (1.654) | 0.689 |

| Trust in governance | 1.075 (0.446) | 0.016 | 0.958 (0.414) | 0.021 |

| Trust in stewardship | 0.569 (0.485) | 0.209 | 0.617 (0.451) | 0.182 |

| Age | -0.235 (0.063) | 0.000 | -0.084 (0.063) | 0.182 |

| Gender | -2.124 (1.691) | 0.217 | -0.617 (1.708) | 0.720 |

| Education level – University/Professional | -0.628 (2.151) | 0.770 | -0.474 (2.218) | 0.831 |

| Education level – Post-graduate degree | -0.080 (2.019) | 0.968 | 2.083 (2.004) | 0.299 |

| Income | 5.5E-5 (4.4E-5) | 0.182 | 10E-5 (4.3E-5) | 0.013 |

| n | 462 | 433 | ||

| Log-likelihood | -619.963 | -586.911 | ||

| LR chi2 | 50.47 | 46.97 | ||

| Country and group | Monthly Average WTP | Monthly Median WTP | Annual Average WTP | Annual Median WTP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK – control (£) | 18.33 | 18.59 | 220 | 223 |

| UK- treatment (£) | 20.26 | 19.72 | 243 | 237 |

| Spain – control (€) | 24.37 | 24.40 | 292 | 293 |

| Spain – treatment (€) | 23.82 | 23.89 | 286 | 287 |

| SAP benefits | Soil quality concern | Pro-social behavior | Trust in governance | Average WTP control |

Average WTP treatment |

Diff. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5 | Low | 5 | 41.84 | 31.45 | -10.39 (-24.83) |

| 5 | 5 | High | 5 | 44.27 | 31.38 | -12.88 (-29.10) |

| 1 | 1 | Low | 1 | 7.52 | 9.38 | 1.86 (24.73) |

| 1 | 1 | Low | 10 | 11.09 | 13.70 | 2.61 (23.53) |

| 1 | 1 | High | 1 | 9.96 | 9.44 | -0.52 (-5.22) |

| 1 | 1 | High | 10 | 13.53 | 13.77 | 0.24 (1.77) |

| 1 | 10 | Low | 1 | 67.80 | 40.82 | -26.98 (-39.79) |

| 1 | 10 | Low | 10 | 71.37 | 45.15 | -26.22 (-36.74) |

| 1 | 10 | High | 1 | 70.24 | 40.89 | -29.35 (-41.79) |

| 1 | 10 | High | 10 | 73.81 | 45.22 | -28.59 (-38.73) |

| 10 | 1 | Low | 1 | 20.88 | 23.12 | 2.24 (10.73) |

| 10 | 1 | Low | 10 | 24.45 | 27.45 | 3.00 (12.27) |

| 10 | 1 | High | 1 | 23.32 | 23.19 | -0.13 (-0.56) |

| 10 | 1 | High | 10 | 26.89 | 27.51 | 0.62 (2.31) |

| 10 | 10 | Low | 1 | 81.16 | 54.57 | -26.59 (-32.76) |

| 10 | 10 | Low | 10 | 84.73 | 58.90 | -25.83 (-30.49) |

| 10 | 10 | High | 1 | 83.60 | 54.64 | -28.96 (-34.64) |

| 10 | 10 | High | 10 | 87.17 | 58.96 | -28.21 (-32.36) |

| SAP benefits | Soil quality concern | Pro-social behavior | Trust in governance | Average WTP control |

Average WTP treatment |

Diff. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5 | Low | 5 | 41.93 | 33.22 | -6.98 (-20.77) |

| 5 | 5 | High | 5 | 45.57 | 34.95 | -12.35 (-23.30) |

| 1 | 1 | Low | 1 | 9.60 | 7.51 | -2.09 (21.77) |

| 1 | 1 | Low | 10 | 19.50 | 16.13 | -3.37 (-17.28) |

| 1 | 1 | High | 1 | 13.23 | 9.25 | -3.98 (-30.08) |

| 1 | 1 | High | 10 | 23.15 | 17.86 | -5.29 (-22.85) |

| 1 | 10 | Low | 1 | 58.59 | 39.65 | -18.94 (-32.33) |

| 1 | 10 | Low | 10 | 68.50 | 48.27 | -20.23 (-29.53) |

| 1 | 10 | High | 1 | 62.23 | 41.39 | -20.84 (-33.49) |

| 1 | 10 | High | 10 | 72.14 | 50.01 | -22.13 (-30.68) |

| 10 | 1 | Low | 1 | 23.45 | 24.60 | 1.15 (4.90) |

| 10 | 1 | Low | 10 | 33.36 | 33.22 | -0.14 (-0.42) |

| 10 | 1 | High | 1 | 27.09 | 26.33 | -0.76 (-2.81) |

| 10 | 1 | High | 10 | 37.00 | 34.95 | -2.05 (-5.54) |

| 10 | 10 | Low | 1 | 72.44 | 56.74 | -15.70 (-21.67) |

| 10 | 10 | Low | 10 | 82.35 | 65.36 | -16.99 (-20.63) |

| 10 | 10 | High | 1 | 76.08 | 58.47 | -17.61 (-23.15) |

| 10 | 10 | High | 10 | 85.99 | 67.09 | -18.90 (-21.98) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).