1. Introduction

Environmental pollutants are observed in various matrices stressing organisms at various ecological levels. Various studies have shown that human borne pollution can cause morbidity and death in organisms and destabilize physiological processes such as reproduction and development (Ahmed et al., 2012). A number of prominent environmental issues exist of which poor solid waste management is one (Christensen et al., 2001; Ikem et al., 2002; Alimba et al., 2006; Oshode et al., 2008). Waste disposal management are ecologically genuine issues because of the deleterious effects associated with contamination like heavy metals and its encompassing conditions (Bakare et al., 2012). Solid waste generation is on the increase due to fast paced development and rising population growth and waste disposal sites are capable of releasing large amounts of harmful pollutants such as heavy metals into water sources, air via leachate and landfill gas respectively (Christensen et al., 2001; Ikem et al., 2002; Alimba et al., 2006; Oshode et al., 2008). In spite of the fact that a few pollutants could later degrade, some such as heavy metals are exceptionally toxic and could accumulate in the environment over a long period of time. Heavy metals are an overall term that includes most prominent transition and post transition metals in the periodic table (Nkwunonwo et al., 2020), lanthanides and actinides (Adepoju-Bello et al., 2009) and metalloids (Igwe et al., 2005) with relatively high density (Tchounwou et al., 2012). Natural sources include metal bearing mineral or rocks while anthropogenic sources include agriculture (composts, fertilizer, pesticides applications), metallurgy (mining, smelting activities), energy production (power plant, leaded gasoline), airborne sources, wastes (solid wastes, mechanical wastes) and sewage disposal (Navratil and Minarik, 2005; Wuana and Okieimen, 2011; Odika et al., 2020).

Various studies have shown that some metals are essential nutrients for several physiological and biochemical functions in minute concentrations (WHO, 1996), while some are non-essential and some are toxic (Jarup, 2003; Ayeni, 2014). Heavy metals have certain characteristics that make them readily Available in environmental matrices. They are affected by pH, adsorption levels as well as soil type and could be toxic at minute or high concentrations inducing metabolically deleterious effects (Volesky, 1990; Ali et al., 2013; Sartoti and Vidrio, 2018; Lai et al., 2020). Other factors include speciation and temperature all of which influence their solubility, mobility, availability and accessibility. The fate and transport of heavy metals also depends on various routes or sources such as soil, water, rock and sediment. These heavy metals could affect ecological balance in biota through bioaccumulation and biomagnification in the food chain or trophic levels (Aycicek et al., 2018; Ali et al., 2019). They are non-biodegradable environmental contaminants that may accumulate in the higher levels of the food chains (Boncompagni et al., 2003) and are known to have high biomagnifying potential particularly to apex predators which are subject to the most deleterious exposure (Borga et al., 2001). They accumulate in living organisms when ingestion surpasses detoxification (Eagles-Smith et al., 2016). These metals are of specific concern for prominent avian species that bioaccumulate contaminants and are considered vital to ecotoxicological hazard assessment or monitoring (Heys et al., 2016).

Ecological studies are concerned on assessing the connection between the biotic and abiotic matrices (Saint-Beat et al., 2015). Contaminant concentrations in living organisms could be a reflection of the concentration in the environment. High concentrations could affect living organisms across trophic levels (Mackay et al., 2018). It is therefore important to assess the impacts of metal concentrations, their mixtures in biotic or abiotic matrices, their fate and transport, their bioaccumulative potential across trophic levels (Mussali-Galante et al., 2013), bioconcentration in regulatory frameworks, which are all important in contaminant exposure and risk assessment (Mackay et al., 2018). Two types of environmental monitoring strategies exist which include the biological (biomonitoring) and traditional monitoring. Traditional monitoring assesses the accumulation, possible changes in sources and factors linked with the general impacts in the environment. It aims to monitor and assess the actual state of the environment, and predict the vulnerability of future outcomes (Pyagay et al., 2020). It is usually carried out by chemical assessment of diverse environmental compartments like soil, air and water. However, the investigation of contaminants within the abiotic environment is in any case inadequate as it does not give sufficient data on the concentration of contaminants in biota and its impact on them (Swaileh and Sansur, 2006). The use of various of biological markers to assess environmental changes is known as bioindication or biomonitoring and it is one of the fundamental strategies utilized in environmental contamination (Rutkowska, 2018).

Species or ecological communities can be used as monitors of environmental pollution. Some characteristics that drive the utilization of biomonitors include: (a) assessment of ecological health (Martinez et al., 2012; Markowski et al., 2013) (b) responsiveness to anthropogenic stress (c) makes assessment of levels of environmental pollution easy (d) the assessment of contamination in the food and (e) to mirror the temporary and longer durational trend of contaminant exposure and environmental availability (Gomez-Ramirez et al., 2014; Pollack et al., 2017). Birds have largely been utilized as sentinels for environmental pollution Gomez-Ramirez et al., 2014; Smits and Fernie, 2013) and are exposed to contamination through contaminated rain, contaminate soil, wastes and water (Jasper et al., 2004). They have been used as bioindicators for various ecological contaminants (Gragniello et al., 2001) especially heavy metals (Mochizuki et al., 2002). This is because they are readily available, ubiquitous, sensitive to toxicants and tagged as sentinels of ecological concern (Furness, 1996). Estimating the accumulation of contaminants in birds was frequently done through invasive or destructive testing, where birds were discarded after tissue extraction and analysis (Acampora et al., 2017).

Pollution studies conducted using the internal tissues (liver, muscle, adipose tissues, kidney) of birds have however caused adverse effects in avian populations (Monclus et al., 2018). In general, fauna populations are affected due to ecological degradation, reduced function and stress. These has driven ecotoxicologists to using non-invasive assessments and methods to protect biodiversity (Adeogun et al., 2022). This pressure on the use of birds in research called for ethical and non-destructive (non-invasive) methods (Espin et al., 2010). Amongst biomonitoring choices, feather assessment stands out and offers many benefits (Garcia-Fernandez and Martinez-Lopez, 2018). The appraisal of environmental contaminants in feathers is a prominent method that has been progressively utilized in ecotoxicological considerations (Abbasi et al., 2016a; Pollack et al., 2017). Feathers can reflect the inner state of contamination, giving an important tool for biomonitoring pollution (Monclus et al., 2018) and contaminants in feathers also reflect that in organs or tissues (Jaspers et al., 2007a).

The use of feathers in assessment of accumulation particularly heavy metal accumulation has a number of advantages over other non-invasive matrices which include: removing the feather can occur irrespective of time, age (young or adult) or gender and collected feathers can be stored and later utilized in future studies (Rutkowska et al., 2018), it also provides important data on endangered and protected species in relation to the avian contaminant cycle (Kopec et al., 2018), reflect internal conditions in tissues or organs (Jaspers et al., 2011), reflect substantial concentration or accumulation which could be higher in feathers than in other tissues (Malik and Zeb, 2009; Zamani-Ahmad et al., 2010). Many bird species living in close proximity to anthropogenic activities are predisposed to ecological foreign substances and they may experience the deleterious effects of the subsequent harmful impacts of such substances (Malik and Zeb, 2009). Birds accumulate metals in feathers and the extent of physiological anomalies (like bilateral asymmetry and developmental instability etc. (Debat and David, 2001) in feathers is precise for each metal. A moderately high concentration specific to metals in relation to body weight is deposited in feathers (Burger, 1993), and there is a strong relationship between concentration of foreign substances in feeding habits of birds and concentration levels in feathers (Malik and Zeb, 2009; Zamani-Ahmad Mahmoodi et al., 2010). The aim of the study was to determine metals and toxic heavy metals (THMs) concentrations in avian feathers, thereby assessing bioaccumulation across avian trophic levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

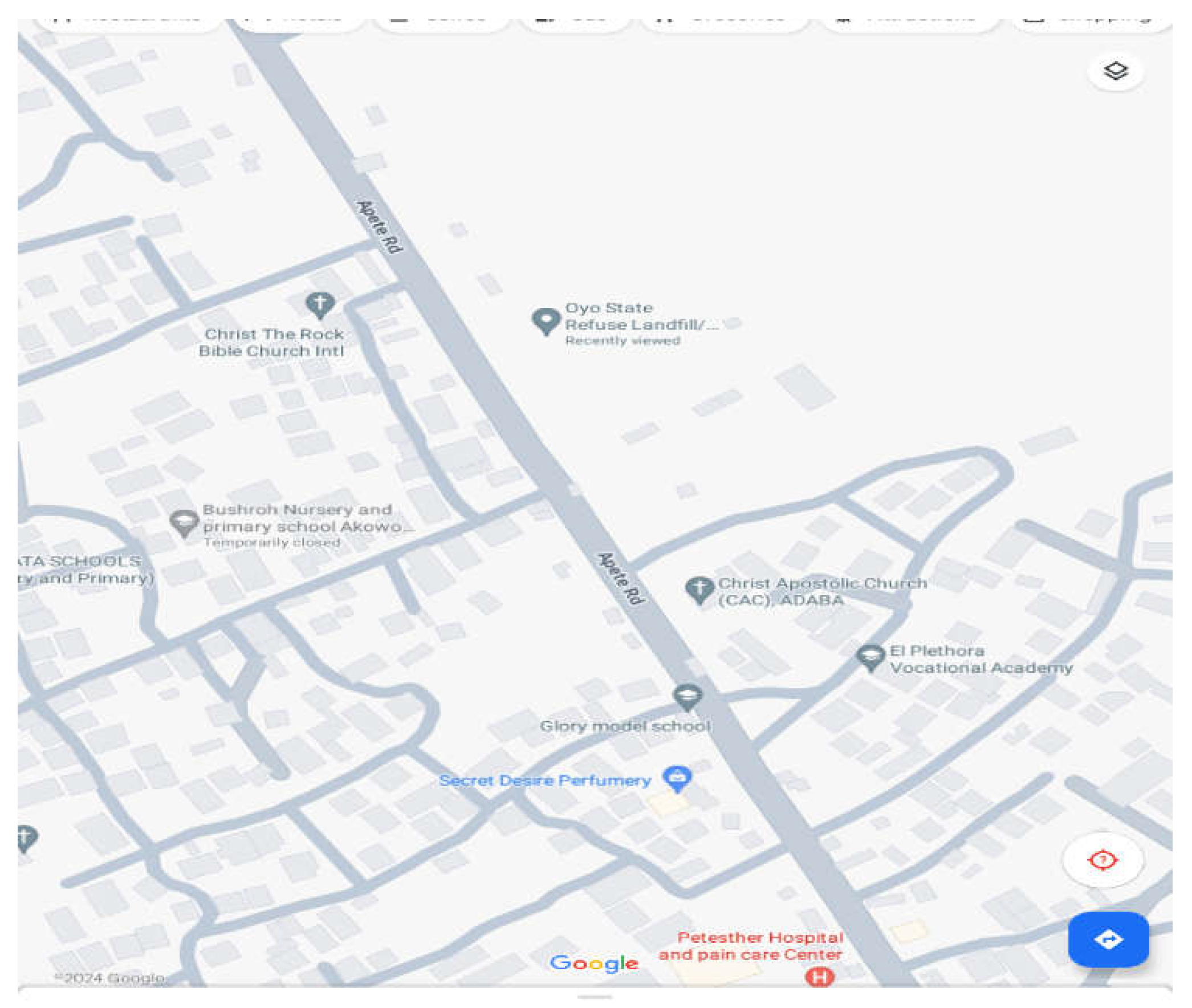

Ibadan, the Oyo state capital is estimated to be one of the largest cities in Nigeria with an approximate total area of 3,080 sq. kilometres and it generates over 996, 102 tons of solid waste annually (Amuda

et al., 2014). The landfill is located 200-250 metres above sea level and on latitude 07

027.59N and Longitude 03

050.93E, along Apete-Awotan-Akufo road, Apete, Ido local Government Area, Ibadan, Oyo state (Ipeaiyeda and Falusi, 2018). It receives municipal wastes from commercial, domestic, educational and industrial sources from many other locations around Ibadan metropolis (Ogunseiju

et al., 2015).

Figure 1

2.2. Sampling Stations and Sampling Procedure

2.2.1. Point Count Method and Species Identification

Following the guidelines and procedures laid down by Ralph et al. (1993), Bibby et al. (1992), Bibby et al. (2000), Sutherland et al. (2004) and Edegbene (2018), the birds of the Awotan landfill were assessed through area and point count methods once a week between the months of June and October 2021. Effective sampling was carried out 3 times in June and August, 4 times in July and once in September and October respectively. Area count was carried out for the general study area while point count was carried out for strategic sampling stations on the landfill (Ralph et al. 1993; Sutherland et al., 2004, 2005). Three sampling points were assessed and sampling points were spaced about 150 metres apart. The three points sampled were: Point A (an area where wastes were largely dumped), Point B (area with vegetation) and Point C (an area within the site devoid of human and scavenger activities). The Birds were observed for a duration of 5-20 minutes and thereafter identified to species level using keys provided by Nik and Demey (2014) and Sutherland et al. (2004). Sampling and point count were done between 6:30 hrs. to 11:00 hrs. in the morning between 13:00 hrs. to 16:00 hrs. in the afternoon and in the evening between 16:00 hrs. to 18:00 hrs. birds set out for their daily activities in the morning and were active throughout the day. Avian census was done by observing, moving through the landfill and standing at specific locations like high altitudes within the landfill for easy assessment (Ralph et al., 1993: Sutherland et al., 2005). The birds were identified using catalogues, identification and reference guides (Adeyanju et al., 2012: Borrow and Demey, 2014).

2.2.2. Mist Net Setup

Based on the procedure adopted by Adeyanju (2013), sampling points were surveyed and selected at random based on the characteristics and habits of the avian species and thereafter sampling was carried out. Mist net set up and procedure was carried out using modified methods of Ralph et al. (1993) and Sutherland et al. (2004). Sampling was done using mist nets, improvised wooden poles which were mounted firmly using support on the base from end to the other. The mist nets were arranged very early in the morning around 6:30 am and the nets were set up throughout the day. The mist nets and points were checked every 10-20 minutes for possible bird capture. Three mist nets of dimensions 20m by 10m, and 30m by 10m with respective mesh sizes of 25mm, 25mm and 45mm were placed to possible bird paths or where bird activities were high.

2.2.3. Diversity Indices Analysis for Point Count Data

Margalef index (d)

It was used to measure the number of species richness of Awotan landfill using the formula below:

Where d- Margalef index, S- total number of species, N- total number of individuals and Ln- Natural log.

Shannon Weiner diversity indices (H)

The point count data of the avian fauna encountered in Awotan was analyzed using the Shannon Weiner diversity indices state below:

H= -∑sPIlnpi

Where, PI- proportion of individual species, s- total number of species in the community, ln- natural logarithm, i- ith species and H- Shannon Weiner diversity

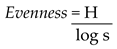

Pielou evenness index

It measures the evenness or equitability of the community and was determined using the formula below:

Where, H- Shannon Weiner index, s- number of species/taxa and Log- Naperian log

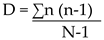

Simpson’s Diversity index (D)

It was used in comparing the diversity between avian fauna obtained from the point count data and takes into account species richness and evenness. It was calculated using the formula below:

Where, D-Dominance, n- total number of individuals per species and N- the total number of organisms of all species counted in a point or station.

2.2.4. Avian Sampling, Avian Tagging, Feather Collection and Storage

Birds were tagged using lightweight plastic avian leg rings to note the sampled birds and avoid capturing (Ralph et al., 1993; Sutherland et al., 2004; Bergan et al., 2011). The captured birds (n=50) were weighed using precision electronic weighing balance (electronic sf-400) and thereafter morphometric measurements were taken based on methods prescribed by Ralph et al. (1993). The total head length, beak/bill length, digit length, wing length, tail length and weight were taken on two individuals (n=2) of the Ethiopian swallow species (Hirundo aethiopica) to ascertain symmetry or asymmetry in relation to avian flight and morphometry. Two to four moulting flight feathers were carefully removed from both the right and left wings to avoid stressing or injuring the caught birds (Rutkowska et al., 2018). Specific factors such as: collection time, feather type, or the foraging pattern of birds was also noted (Garcia-Fernandez and Martinez-Lopez, 2018). The sampling process and intended analysis was non-invasive, so birds were released after sampling and feather gathering. The collected feather samples were stored in labelled Ziploc bags.

2.2.5. Sample Analysis: Feather Digestion and Metal Assay

Feathers were washed with distilled water thrice to remove dirt and particles, and then oven dried (using IHVP-16246927 model oven) at 800c. thereafter, feather samples were cut into small pieces, grinded (with a ceramic mortar and pestle) and weighed. 0.1mg of grounded feather sample was weighed using analytical electronic weighing balance (analytical balance, BA-T series). Weighed samples were treated with 2ml of 70% nitric acid and heated in a water bath at 1200C for 24hrs after which they were left to cool. The samples were then filtered using a 0.4 micrometer filter paper and then diluted to a final volume of 25ml in a volumetric flask with deionized water. Fast-Sequential Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (FAAS, Buck Scientific model 210).

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA was used in comparing the differences in the means of heavy metal concentrations in the feathers of birds across species and trophic levels at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

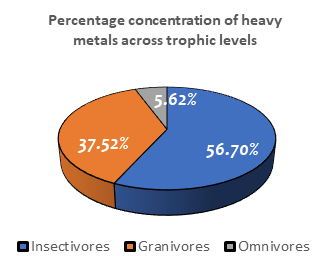

The biodiversity indices of bird species sampled in the Awotan landfill were the Margalef, Shannon Weiner, Simpson and Pieolou indices to assess the abundance and diversity on the landfill (Table 5a and 5b). The result for the heavy metal concentrations in feathers of birds encountered at the Awotan landfill were analyzed in the observed four avian species. 12 metals were observed which included Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu, Co, Cr, Cd, Ni, Al, B, Se and Hg while lead was not detected (Table 6 and 7; Figure 4a, Figure 4b, and Figure 4c.

A total number of 702 birds belonging to 4 families were observed at the Awotan landfill over the study period, of which 2 were resident-migrant, (

Turdus pelios and

Anthus leucophrys) and 2 were resident (

Hirundo aethiopica and

Streptoptelia senegalensis).

H. aethiopica was the most abundant resident species and the most abundant species (

Table 1a and

Table 1b). A total of 50 birds, belonging to 4 families and 4 species were trapped by the mist nets.

H. aethiopica (n=36, 74%) had the highest capture, followed by

S. senegalensis (n=12, 24%) while

T. pelios and A. leucophrys had the lowest capture (n=1, 2%) respectively (

Table 2). Bird species captured per point we’re also documented in

Table 3.

Morphometric measurements were taken for the total head length, beak length, full tarsus length, digit length, wing length and weight which were all taken in centimeters and grams. Bilateral symmetric morphometry was also taken for two representatives of the

H. aethiopica species. The asymmetric and symmetric measurements of the right and left wing, centrum, right and left outer tail feathers were all taken. The morphometric indices were specifically taken to assess symmetry by measuring and comparing the right and left wing lengths, right and left outer tail and the inner tail (centrum) (

Table 4aa and

Table 4bb).

4. Discussion

4.1. Abundance and Diversity

Point count method takes into consideration the relative abundance of birds available in a given area (Edegbene, 2018). Avian and point count assessment was carried out on the Awotan landfill (Ralph

et al., 1998; Sutherland

et al., 2004). From the study, the point count showed that the Ethiopian swallows (63.82%, n=448) were observed in most locations around the landfill, followed by the laughing Dove (35.47%, n=249), African Thrush (0.43%, n=3) and the least observations were the plain-backed –pipit (0.28%, n=2) (Table 1,

Table 2). There were changes in the monthly observation in the dynamics of the availability of the birds (Table 1). Landfills have been identified as good sources of food for bird species and species abundance, due to the waste food that is disposed continually and it could be a reason for the availability of bird species in the Awotan landfill (Oro

et al., 2013; Osterback

et al., 2015; Oka, 2016; Plaza and Lambertucci, 2017). Certain urban or landfill birds (such as the Ethiopian Swallow) are known to have omnivorous or scavenging tendencies (Marasinghe

et al., 2018). Also, anthropogenic activities (intense or liberal) like scavenging or landfill activities could determine the availability of bird species at various points. Where there is high stability, biotic (competition, dominance between one or two species, ecological succession) and physical environmental factors (Ward, 2001), it could affect diversity. These factors do not function differently but diversity reduces when there is depauperation, lack of resources, perturbation and reduced environmental heterogeneity. Similarly, resource abundance or its reduced availability stability, minimal perturbation and heterogeneity might not always create favourable grounds for increased diversity (Protasov

et al., 2009).

The study observed changes in abundance and diversity of species in the Awotan landfill. There was change in species diversity and abundance throughout the sampling period. In addition to the previously slated factors that could affect diversity and abundance in avian species (biota), urban development such as the conversion to landfill could be a factor for the change in the diversity and abundance in the study area (Issakson, 2018). A decline in sentinels in relation to indices of communities is directly linked to pollution of the environment (Alimov

et al., 2013; Barinova, 2017). The biological indices carried out on the sampled avian species and sampling areas of the Awotan landfill all varied for each point. They included the Margalef, Shannon Weiner, Simpson diversity and Pieolou (Evenness) indices. A total 50 birds from four families were trapped in the sampling site and three points A to C were assessed. Point A is an active dump on the landfill characterized with anthropogenic scavenging and landfill activities, point B is a vegetative area devoid of land fill and anthropogenic activities and point C is an inactive dump also devoid of anthropogenic scavenging and landfill activities. The Margalef diversity index assessed on the Awotan landfill had varied indices. Point B had the highest species richness index, followed by point C and point A which had the least index (

Table 5a and

Table 5b).

Maryam et al. (2010) suggests that the diversity index of a healthy ecological community increases with the population of species and the Awotan landfill was lacking in species diversity. The use of such indices is useful in showing pollution as diversity of communities decreases (Alimov

et al., 2013). The Shannon Weiner indices during the sampling period was observed in the month of June, followed by August and the least diverse was observed July. The highest sampling point index was observed in point B, followed by point A and the least sampling point index was observed in point C (

Table 5a and

Table 5b). Dominance is used in the assessment of pollution and an increase in dominance (D) brings about a decrease in diversity (Faiz and Fakhar, 2016). The Simpson dominance indices were computed for both month and sampling points. Point C was the most dominated during the sampling period, followed by point A and point B had the least dominance. The month of July was the most dominant, followed by the month of August and the month of June which had the least dominance index (

Table 5a and

Table 5b). When an ecological community is polluted, less resilient species are affected and resilient species eventually become the dominant species as well as the dominant population. A decline in the data and the resulting population of a species in a community could be linked to a change in the dominance of certain species that differ taxonomically (Desrochers and Anand, 2003). Hence when species are exposed to pollution stress, the population may act differently from the community (Khan, 2016) and dominating species present in large numbers in particular communities are taxonomically more distinct compared to smaller populations (Desrochers and Anand, 2003).

Pielou’s evenness is termed as the distribution of individuals over taxon, like species in their ecological habitat (Heip et al., 1998). The evenness of a community shows the even distribution of some species or living organisms in a community over a specific duration. Throughout the sampling period, the month of July had the highest even distribution, followed by the month of August, and the month of June had the least index. The evenness index was also computed for the various sampling points. Point B had the highest index. The evenness index was also computed for the various sampling points. Point B had the highest index, followed by point A and point C had the least evenness (5a and 5b). with increased environmental stress brings about variability in evenness (the lower the evenness, the higher the probabilistic perturbation from pollution) which could be used to study environmental degradation (Faiz and Fakhar, 2016)

4.2. Heavy Metal Concentrations in Species

Globally, various studies have been carried out on heavy metal toxicity and concentration, trophic level variations in toxicity, and landfills (Malik and Zeb, 2009; Hammed et al., 2017; Marasinghe et al., 2018; Kinuthia et al., 2020). These studies prove landfills are polluted, and toxic concentrations of heavy metals could go up trophic levels and food chains. Studies on the Awotan landfill have also shown that it is polluted leaving biota (like birds) vulnerable to contamination and biotoxicity (Ogunseiju et al., 2015; Hammed et al., 2017; Ipeaiyeda and Falusi, 2018; Olagunju et al., 2020; Oladejo et al., 2020; Adesogan and Omonigho, 2021).

A total of 10 birds were analyzed, belonging to four families respectively. The accumulation of metals varied in all species and there were significant differences at p < 0.05 across species and trophic levels. The analyzed species included the Ethiopian swallow (n=3), Laughing dove (n=3), Plain-Backed-Pipit (n=2) and African thrush (n=2). The concentration of heavy metals analyzed in Ethiopian swallows varied in the increasing array of Zn > Mn >Se > Al > Hg > B > Ni > Co (

Table 6). The laughing dove (granivore) had a high concentration for iron but below the level for the Plain-Backed-Pipit. They had zinc, manganese, chromium, cadmium, boron and nickel concentrations just below that of the Plain-Backed-Pipit and lead concentrations (0.000 µg/g) were not detected. They had the lowest concentrations for nickel, cobalt, chromium and cadmium. The metals analyzed in laughing doves varied in the order: Fe > Zn> Mn > Se> Al > Hg > B > Cu > Co > Cr/Cd/NI > Pb (

Table 6).

The African thrush (Omnivore) had the highest concentrations for aluminum, boron, selenium, nickel and mercury. The analyzed metals varied in the order: Zn > Se > Mn > Al > Hg > B > Co > Ni (

Table 6). The Plain-Backed-Pipit (insectivore) had the highest concentrations of zinc, iron, manganese and the lowest concentrations for mercury, cobalt, nickel, chromium, cadmium, cobalt also had low concentrations. Lead concentrations were not detectable (0.000µg/g). The heavy metal accumulation in the feathers of the Plain-Backed-Pipit varied in the reducing order of Fe > Zn > Mn > Se > Al > B > Hg > Cu > Cr/Cd/Co/Ni > Pb (not detected) (

Table 6). The observed differences in the large gap in metal contamination and accumulation among species from the landfill could be factor of variations in the interspecific food chain (Jayakumar and Muralidharam, 2011)

4.3. Heavy Metal Concentrations across Various Avian Trophic Levels

Iron

Iron was observed in high concentrations amongst the metals analyzed but it was low compared to levels (0.15-7.68ppm) observed by Einoder et al. (2018) but fell into the range observed. The insectivores (

Hirundo aethiopica and

Anthus leucophrys) accumulated the highest concentrations of iron in their feathers and the granivores (

Streptoptelia senegalensis) had a high a concentration just below the insectivores (

Table 7). There was significant difference in iron concentration across trophic levels at p< 0.05. The high iron accumulation in the feathers show the feeding and stored concentrations during feather development (Dauwe

et al., 2000; Rattner

et al., 2008). The granivores could have accumulated iron through ingestion of food, soil particles, from plant that have accumulated iron. The accumulation of iron could be due to the dumping of metal scraps, electronic, electrical and industrial wastes which could introduce iron to the soil of landfills. The concentrations observed in the birds were above the limits of 50-80ppm (Adesakin, 2021). Lethal accumulation of iron could induce hepatic storage in many vertebrates leading to haemosiderisis and physiological changes in reproduction and moulting (Tobias

et al., 1997).

Zinc

The presence of zinc in landfills is expected (Ngole and Ekosse, 2012). Sources of zinc in the landfill could be from deteriorated roofing sheets, packaging materials, paint, metal and steel materials and vehicular parts and food or cleaning materials (Alloway, 2005; Ngole and Ekosse, 2012). The zinc concentration observed was above the standard threshold at 1200 µg/g or 800-4000ppm (Abdullah

et al., 2015; Adesakin, 2021) which means that the birds have accumulated zinc above the safe limit and could be prone to harmful effects of zinc toxicity. The concentration was below the observed concentrations of Janaydeh

et al. (2015). There was significant difference in zinc concentration across trophic levels at p < 0.05. the insectivores had a higher accumulation of zinc and the omnivores had the least accumulation of zinc. The omnivores and granivores could have accumulated through the ingestion of contaminated soil particles, contaminated food or contaminated soil along with food which have absorbed or adsorbed zinc and leachates (

Table 7). Zinc is an essential metal in the metabolic activities organisms especially in birds and excess 6accumulated zinc could be deleterious.

Mercury

Several studies carried out on heavy metal accumulation pointed to the fact that mercury increases with rise in trophic level (Burger and Gochfield, 1997; 2000a; Borga

et al., 2006). Mercury is a toxic metal found everywhere in the environment which induces lethal deformations in tissues and cause several health effects (Sarkar, 2005). Humans or animals alike are vulnerable to mercury contamination in the environment (Zahir, 2005). Accumulated mercury in feathers show the contamination of mercury in blood and tissues ( Bearhop

et al., 2000). Based on the trophic levels birds occupy, they are at high risk and are prone to hereditary and neurological effects from mercury contamination (Burger, 1993; Evers

et al., 2005). The insectivores (Ethiopian swallow and Plain-Backed-Pipit) had the highest level of mercury contamination and the granivores (Laughing dove) had the lowest concentration (

Table 6). The concentrations were below (0.09ppm-0.97ppm) observed in Keller

et al. (2014) and there was significant difference in mercury concentration across trophic levels at p < 0.05.

The presence of mercury in the landfill could be as a result of the waste and various sources into the environment. The utilization and source of mercury is numerous. It is used in electronic industries in the production of various electronic industries in the production of various electrical appliances, other industrial processes could find their way into the landfill. The granivores could have accumulated mercury through ingestion of contaminated soil particles, seeds or plants while the insectivores could have accumulated mercury from the ingestion of contaminated insects (Ab-Latif

et al., 2015). The concentration observed was low and below the standard threshold for some individuals while some the concentrations of some other individuals were close or above the threshold (

Evers et al., 2008) (

Table 7).

Cadmium

Cadmium is a non-essential toxic metal found in birds mostly of granivorous origin (Manjula

et al., 2015). Cadmium was observed in very low concentrations below the standard limit of 2 µg/g (Abdullah

et al., 2015). There was no significant difference in cadmium concentration across trophic levels at p < 0.05. the low concentrations observed shows that these metals are present in the environment in small concentrations but were below levels (0.021ppm-2.65ppm) observed by Boncompagni

et al. (2003). The insectivores accumulated above the granivores (

Table 7). Further accumulation in feathers could lead to lethal effects (Burger, 1993). Accumulation of cadmium (Cd) can induce retardation in growth, reduction in egg production (Burger, 2008), eggshell thinning, kidney damage (Furness and Greenwood, 1993). At sub-lethal toxicity, cadmium could induce: behavioural effects, endocrine disruption, haemoglobin anomalies, moulting anomalies, formation and growth anomalies (Burger and Gochfeld, 2009), damage, oviduct and testicular anomalies (Malik and Zeb, 2009; Birge

et al., 2000; Burger, 2008) and higher concentrations can induce physiological activities by replacing essential nutrients or causing nutrition anomalies (Furness, 1996). Cadmium is often used in several industrial processes which include the industrial use of cadmium in alloy production, pigments, And batteries (Mcdowell, 2003).

Cobalt and Chromium

Cobalt is an essential microelement (Plant, 2000; Vinodhini and Narayanan, 2009). It has bioaccumulative and radioactive tendencies. High concentrations of cobalt in biota could be lethal, inducing harmful effects such as pneumonia, thyroid damage, pulmonary anomalies, permanent disability and mortality (Atashi

et al., 2009). It could be found adsorbed to organic particles in soil (Plant, 2000). The concentrations observed were low, as the omnivore had a higher concentration than the granivores (

Table 7). The source of chromium in the environment is varied. It is used broadly in the plating of metals, paint manufacturing, preservatives, paper and pulp industries (Jaishanjar

et al., 2014), sewage and fertilizer application. Landfills could get polluted when chromium containing wastes get disposed. Toxic effects of Chromium (VI) can induce DNA damage or chromosomal anomalies (Patlolla

et al., 2008) and reproductive anomalies in avian species (Malik and Zeb, 2009). There was significant difference in cobalt and none was observed in chromium concentrations across trophic levels at p < 0.05. the concentration observed were lower than the standard limit of Cr at 2.8 µg/g (Abdullah

et al., 2015).

Nickel

Nickel is toxic non-essential metal that causes deleterious impacts to living organisms especially birds in which it is likely to affect metabolic activities relating to feathers (Eeva et al., 1998). At high concentrations, nickel affects feather moulting in avian species (Malik and Zeb, 2009) and reduces liver weight, induces liver damage, causes immunotoxicity, anaemia and protein degradation (Zivkov et al., 2017). Nickel was also observed in low concentrations below the standard threshold of 5 µg/g (ppm) (Abdullah et al., 2015). There was nos significant difference in nickel and the least concentration was observed in the granivores (Chiroma et al., 2014; Ayeni et al., 2016). It is utilized in the production of stainless steel, electronics, electroplating and coins (Ngole and Ekosse, 2012). Deposition of nickel into the environment ranges from about 150,000 to 180,000 metric tons annually (Kazprazak et al., 2003) and the presence of nickel in such materials detects its fate in the environment and in landfills.

Manganese

Manganese is abundant in the environment mostly found in the soil and adsorbed to acidic soils. Living organisms that are sensitive to manganese could be exposed to its toxicity via acidic soils polluted with manganese. The disposal of wastes containing manganese could also be a prominent source of manganese (Osuala

et al., 2020). There was significant difference in manganese concentration across trophic levels at p < 0.05. the insectivores had the highest accumulation of manganese and the omnivores had the least accumulation (

Table 7). Adverse effects of manganese could occur from both deficiency and overexposure which could cause harmful effects (Hubbs-Tait

et al., 2005). Accumulation of manganese could occur through ingestion of contaminated food and inhalation of manganese adsorbed dust (Qadir

et al., 2018). At toxic concentrations manganese could induce harmful effects such as anaemia, haemorrhage, micromelia, limb twisting, stunted growth and behavioural disorders (Summer

et al., 2011). Improperly disposed wastes and other industrial wastes and waste combustion also induce manganese stress in the environment and could be sources of manganese pollution (Zayed

et al., 1999) and diesel fuels (leaded gasoline) treated with manganese. Disposed wastes containing manganese treated lead gasoline and diesel fuels could also be a likely source of manganese in landfills (Qadir

et al., 2008).

Copper and Boron

Ngole and Ekosse (2012) who carried out a similar study on landfills mentioned the availability of metals such as copper in landfills and dumps. Copper is an essential metal which becomes toxic at high concentrations (McDowell, 2003; McDowell, 2013). It should be noted that the threshold for the effects of copper in the gastrointestinal tract still leaves some uncertainty regarding the long term effects of Cu on sensitive organisms (Nkwuninwo

et al., 2020). There was no significant difference in copper concentrations below standard threshold of Cu at 20 mg/g (Jaynadeeh

et al., 2016) (

Table 7). The accumulation route by which the granivores and insectivores accumulated copper would have been via ingestion of contaminated food or soil particles, and insects. Resulting Cu toxicity could induce growth anomalies, respiratory anomalies, carcinogenesis, haematolysis, endocrine disruption, reproductive disorders, gastro-intestinal and hepatic disorders (Stern, 2010, anaemia and poor feathering in birds (De, 2019). The insectivores had the highest concentration of boron while the omnivores had the lowest concentration (

Table 7). The accumulation of boron could be as a result of various industrial wastes like detergents their packaging, flame retardants and agricultural chemicals (WHO, 1998). Accumulation could have occurred through ingestion of contaminated soil particles and food particle that have adsorbed or absorbed boron. There was significant difference of boron across trophic levels at p < 0.05.

Aluminum

Aluminum is utilized in various industrial processes like pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, dyes and packaging for consumables, in construction and vehicle manufacturing. Aluminum could find its way to the landfill through wastes from various aluminum industries and utilizations. There was significant difference in aluminum concentration across trophic levels at p < 0.05. the omnivores had the highest concentration of aluminum and the granivores had the lowest concentrations (

Table 7). It can contaminate soils and bioaccumulate in birds through consumption of contaminated materials. The granivore could have ingested contaminated soil particles along with food while the insectivores could have ingested insects which have bioaccumulated aluminum. Al causes toxicity in living organisms by inducing cytological stress by reactive oxygen species (ROS), peroxidation of lipids and destabilization of antioxidant enzymatic functions (Slaninova

et al., 2014).

Selenium

The environmental sources of selenium are varied. It is utilized in electrical and electronics industries, paint industries, glass industries, mechanical and clinical applications (Mehdi

et al., 2013), ceramics (20%) for staining and pigmentation, used in metallurgy in metal treatment, vulcanization of rubber, pharmaceuticals and for the oxidation of some processes. Selenium could find its way into landfills by aerial deposition or by waste disposal originating from the prior listed sources. Selenium concentrations was highest in the omnivores and lowest in the insectivores (

Table 7). There was significant difference in selenium concentration across trophic levels at p < 0.05. The selenium concentrations observed was close to the standards set by the WHO at 5020ppm (Adesakin, 2021) with a few having below the threshold, close to the threshold and above the threshold limits. Concentrations were not in the range observed by Gushit

et al. (2016). The accumulation of selenium could have been as a result of ingestion of contaminated soil particles, plants and plant materials which bioaccumulated selenium or landfill leachates. Signs of selenium toxicity could include musculoskeletal anomalies, weak digits, fast growth and baldness (Meschy, 2010). Feather concentrations depicting selenium toxicity could reach 800 to 26,000 ppb which could cause mortality in species (Burger, 1993), and concentrations at 1,800 ppb could result in sub-lethal adverse effects (Heinz, 1996).

Lead

Lead was not detected in the feathers of the analyzed birds but the standard threshold for lead in feathers is 4 mg/kg or 4,000 ppm. At 4 ppm, lead concentrations can cause harmful effects in birds (Burger and Gochfeld, 2000). Exposure of birds to lead can occur through inhalation of lead adsorbed particles, aerosols or by ingestion of contaminated food or water (Ab-Latif et al., 2015: Kinuthia et al., 2020). Lead poisoning may induce haemoglobin synthesis, anemia, also accumulate in bone of living organisms (Plant, 2000), stunted growth, behavioural anomalies (Burger, 1993), decreased plasma calcium, reproductive anomalies, impaired thermoregulation, locomotion, depth perception, feeding behaviour, lowered chick survival (Burger and Gochfeld, 2000) and in some cases cause mortality in birds (Einoder et al., 2018). Sources of lead into the environment could be through mining activities, metal products, weapons and lead-acid batteries. It could also occur from cosmetics, paints, industrial sources, crystals and ceramic containers and food (Tchounwou et al., 2003). Constant disposal of lead containing wastes materials could increase the pollution and cause the potential contamination of avian species in landfills.

4.4. Asymmetry and Asymmetric Morphometry of Birds

Knowledge about the balance of the ecosystem and its matrices is akin to understanding the pernicious effects that could impact biota or the ecosystem, which helps in foreseeing environmental exacerbations (Lajus et al., 2015). The effects on biodiversity can be understood in various patterns, which depends on the aim of the study, the study itself, and the subject of study (Newman, 2014). Naturally, even in minute considerations, change in developmental stability (change in symmetry) affects the bilateral symmetry of organisms. These changes are called fluctual asymmetry and it occurs when an organism develops under extrinsic or intrinsic situations which are unfavourable (Daloso, 2014). Environmental stressors such as pollution can induce poor developmental stability in living organisms which may affect biological activities (Clarke 1995; Moller and Swiddle, 1997). Laith et al. (2020) demonstrated that persistent organic pollutants (POP) and toxic heavy metals (THM) have strong affinity with bilateral asymmetry (developmental instability).

Asymmetric assessment (also known as fluctual asymmetry) has become a famous tool and an area of debate presently utilized by ecologists in biomonitoring (Leung et al., 2003). It is termed a dynamic deviation from symmetry that occurs in specific parts of an organisms’ body which is a result of intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Nass et al., 2008). Developmental stability could be estimated by levels of asymmetry which occurs when the bilateral characteristics show differences in bilateral symmetry. The degree of asymmetry (fluctual asymmetry) could show the inability of living organisms like birds to carry out their biological or metabolic activities when faced with extrinsic and intrinsic factors (Almeida et al., 2007). Works relating to the effect of stress in fluctual asymmetry has been carried out on birds (Minias et al., 2013; Herring et al., 2016)

Amongst the popular avian structures utilized in symmetry are the wings and tail feathers. The feathers, tails and wings function in a coordinated manner providing lift and reduce drag. These shows the importance of both the wing and tail feathers in the maintenance, stability, maneuverability, agility and speed of flight in avian species. Birds vary in their morphology and in the morphology of their wings or tails. To a certain level, asymmetry is needed in the feathers of birds (primary wing feathers are asymmetrical and secondary are mostly symmetrical) to balance their aerodynamics (Thomas and Balmford, 1993).

Birds utilize feathers of the wings and tails for aerodynamic flight, any distortion in the orientation of their wings would cause imbalance or asymmetry which could affect the aerodynamics of their flight. When the feathers of the tails and wings of birds are disoriented or become negatively asymmetric (unlike natural asymmetry like that of primary feathers), the dynamics of the flight could be affected (Thomas and Balmford, 1993). While sampling birds on the study site, it was observed during feather sampling that flight of birds were distorted immediately birds were released after feather culling.

Specific morphometric measurements were taken to assess possible asymmetry in two individuals representing the

Hirundo aethiopica species from the study area. The estimated measurements were the right and left wing length, the right and left outer tail length, the centrum (innermost tail feathers) and the type of tail (

Table 4b). For Ethiopian swallow 1, no asymmetry was observed in the right and left wing length but asymmetry was observed between the left and right outer tail feather. For Ethiopian swallow 2, asymmetry was observed between the right and left wing length and between the left and right outer tail feather (

Table 4b.).

Asymmetry was observed in the feathers of the wings and tails of the representative Ethiopian swallows, although Ethiopian swallow 1 had symmetry in the length between its left and right wings. Based on previous studies carried out, increased morphological asymmetry could be as a result of environmental factors (contamination, parasitism, low food availability) or intrinsic factors like genetic stressors (hybridization, high inbreeding, small population size) and the combined effect of both extrinsic and intrinsic factors could be high (Parson, 1992).no matter the source of asymmetry, it is still important to environmental sustainability and developmental activities of biota affected could reflect the problem at community level (Callaway et al., 2003; Werner and Peacor, 2003). This means that degraded environments can affect developmental activities of living organisms thereby producing traits (different phenotypes) and consequently affecting interspecific and intraspecific links which impact the dynamics of communities (Cuervo and Retrespo, 2007).

Parra et al. (2010) suggested that changes in environmental stability affects avian species giving way to asymmetry. Increasing asymmetry in degraded environments like landfills are believed to reflect the effects at avian community level making the estimation of asymmetry a sensitive indicator of environmental degradation and also acting as flag for conservation measures (Clarke, 1995). Previous works point to toxic heavy metal contamination as causes of increased asymmetry in primary feathers of birds (Eeva et al., 2003). A good example of heavy metal prone asymmetry is the high bioaccumulation of mercury which could affect the asymmetry of the wing and tail feathers of birds as seen in wild birds of some studies carried out (Evers et al., 2008; Clarkson et al., 2012), which could affect flight by increasing the energy utilized (Hambly et al., 2004), affect long distance migration of birds, and prolong migratory stops.

Conclusion

The continuous pollution of the environment is gaining awareness globally and environmental degradation and pollution are not negligible in the strive for environmental sustainability. Landfills are prominent sources of biological and environmental contamination and from the study, it was observed that the Awotan landfill is polluted with heavy metals. The resident avian fauna has bioaccumulated considerable amounts of heavy metals in their tissues and feathers across observed trophic levels which could affect the aves and ecosystem balance. Birds serve as good sentinels due to their trophic positions and it is a red flag for what is yet to occur. Therefore, the assessment of biota such as birds, using non-invasive techniques like feather assessment is a relevant and guided path in the knowledge of contaminants’ fate and pattern of contamination in biota and the environment.

The use of feathers serves as an effective non-invasive biomonitoring approach for assessment of heavy metal concentrations in avian species and trophic levels. Observations of heavy metals in feathers of the granivores and insectivores especially, indicate that bioaccumulation occurred up the trophic levels. The ingestion of soil particles and contaminated food by granivores, insectivores and omnivores show that the landfill is polluted. From the study, the assessed Ethiopian Swallow species were found to have bioaccumulated heavy metals (HMs) and toxic heavy metals (THMs) concentrations. Hence, the representative species are also affected by stress and could reflect the effects in their phenotype (fluctual asymmetry or developmental instability), plumage and other physiological anomalies. These could depict intrinsic reactions to environmental pollution or stress.

The availability of any xenobiotic is deleterious to biota and ecosystem health, and so the research gives an insight to the availability of these contaminants in the lithosphere, hydrosphere and atmosphere, their toxicity or carcinogenicity and also their availability in biological matrices. Adeogun et al. (2022) did an extensive overall review on the researches done in relation to bioaccumulants and xenobiotics in the feathers of birds. This has shown a great deal of exposure to such research and the importance of feather assay and non invasive methods.

References

- Abdullah, M. , Fasola, M., Muhammad, A., Ahmad Malik, S., Bostan, N., Bokhari H., Aqeel Kamran, M., Nawaz Shafqat, M., A Alamdar, A., Khan, M., Ali, N., Ali Musstjab, S. and Shah Eqani, A. 2005. Avian feathers as a non-destructive bio-monitoring tool of trace metals signatures: A case study from severely contaminated areas. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Acampora, H. , White, P., Lyashevska, O., and O’Connor, I. 2017. Presence of Persistent organic pollutants in a breeding common tern (Sterna hirundo) population in Ireland. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 16933–16944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, J.T. , Eagles-Smith, C.A., Takekawa, J.Y., Bluso, J.D., Adelsbach, T.L. 2008 Mercury concentrations in blood and feathers of prebreeding Forster’s terns in relation to space use of San Francisco Bay, California, USA, habitats. Environ Toxicol Chem 27(4):897–908.

- Adesakin, T.A. 2021. Health hazards of toxic and essential heavy metals from thr poultry waste on human and aquatic organisms. IntechOpen.

- Adeyanju, T. E. and Adeyanju, T. A. (2013). Avifauna of University of Ibadan Environs Ibadan, Nigeria Proceedings of 3rd Annual Seminar of Nigerian Tropical Biological Association. pp. 27–34.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry 2005. Toxicologycal profile for Zinc. Nationwide Urban Runoff Program (NURP). www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/ip60-c6. Accessed 30th October 2021.

- Ahmed, S. , Ahsan, K. B., Kippler, M., Mily, A., Wagatsuma, Y., Hoque, A. W., Ngom, P. T., El Arifeen, S., Raqib, R. and Vahter, M. (2012), Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 129, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akporido, S.O. , and Onianwa, P.C. 2015. Heavy Metals and Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon Concentrations in Surface Water of ESI River, Western Niger Delta. Res. J. Environ. Sci.

- Alimba, C.G. , Bakare, A.A., and Latunji, C.A. 2006 Municipal landfill leachates induced chromosome aberration in rat bone marrow cells. Afr J Biotechnol, 2006; 5, 2053–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, B.J. 2005. Copper-deficient soils in Europe. International Copper association. New York 2005.

- Almeida, D. , Almovar, A., Nicola, G.G. and Elvra, B. 2008. Fluctuating asymmetry, abnormalities and parasitism as indicators of environmental stress in cultured stocks of goldfish and carp. Aquaculture; 279: 120-125.

- Anyawu, B.O. , Ezejiofor, A.N., Igweze Z.N. and Orisakwe, O.E. (2018). Heavy Metal Mixture Exposure and Effects in Developing Nations: An Update. 2018; 6, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Arizaga,, J., Resano-Mayor, J., Villanúa, D., Alonso, D., Barbarin, J.M., Herrero, A., Lekuona, J.M. and Rodríguez, R., 2018. Importance of artificial stopover sites through avian migration flyways: a landfill-based assessment with the White Stork Ciconia ciconia. Ibis 160, 542 - 553.

- Bakare, A.A. , Adeogun, A.O., Efuntoye M.O., Sowunmi, A.A. and Oshode, O.A. 2008. Ecotoxicological Assessment using clarias gariepinus and microbial characterization of leachate from municipal solid waste landfill. International Journal of Environmental Research, 2008; 2, 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Bakare, A.A. , Patel, S., Pandey, A.K., Bajpayee, M., and Dhawan, A. 2011. DNA and oxidative damage induced in somatic organs and tissues of mouse by municipal sludge leachate. 6, 2012; 28, 614. [Google Scholar]

- Bakare, A.A. , Alimba, C.G. and Alabi, O.A. 2013. Genotoxicity and mutagenicity of solid waste leachates: A review. Vol. 12 (27), pp. 4206-4220.

- Balmford, A. , Jones, I.L. & Thomas, A.L.R. 1993. On avian asymmetry – evidence of natural selection for symmetrical tails and wings in birds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. B 252: 245–251.

- Behrooz, R.D. , Esmaili-Sari, A., Ghasempouri, S.M., Bahramifar, N. and Covaci, A. 2009. Organochlorine pesticide and polychlorinated biphenyl residues in feathers of birds from different trophic levels of South-West Iran, Environ. Int. 35 (2009) 285-290.

- Bell, A. , Marugán-Lobón, J., Navalón, G., Nebreda, S.M., DiGuildo, J. and Chiappe, L.M. 2021. Quantitative Analysis of Morphometric Data of Pre-modern Birds: Phylogenetic Versus Ecological Signal. Front. Earth Sci. 9:663342.

- Bergan, F. , Endal, T., Lambert, F.M., Acosta Roa, A.M., Snartland, S., Steen, S., Steifetten, O., Sødring, M. And Aarvak, T., 2011. Guidelines for the identification of birds in research. Norwegian School of Veterinary Science. Norecopa (2011).

- Bervoets, L. , Voets, J., Covaci, A., Chu, S.G., Qadah, D., and Smolders, R. et al. 2005. Use of transplanted zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) to assess the bioavailability of micro contaminants in Flemish surface waters. Environ Sci Technol, 1492; 39, 1492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Bibby, C.J. , Burgess, N.D., Hill, D.A. and Mustoe, S. 2000. Bird Census Techniques (2nd Edition ed.). London, UK: Academic Press. 1–302.

- Bibby, C.J. , Burgess N.D. and Hill, D.A. In Bird Census Techniques; Academic Press: London, UK, 67 84 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bohmann, K. , Evans, A., and Gilbert, M.T.P. et al. Environmental DNA for wildlife biology and biodiversity monitoring. Trends Ecol Evol, 2014; 29, 358–367. [Google Scholar]

- Boncompagni, E. , Muhammad, A., Jabeen, R., Orvini, E., Gandini, C., Sanpera, C., Ruiz, X. and Fasola, M., 2003. Egrets as monitors of trace-metal contamination in wetlands of Pakistan. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2003; 45, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnard, N. , Brondeau, M.T., Jargot, D., Pillière, F., Schneider, O., Serre, P. and Fiche. Sélénium et composés. Toxicologique.

- Borga, K. , Campbell, L., Gabrielsen, G.W., Norstrom, R.J., Muir, D.C.G.and Fisk, A.T. 2006. Regional and species specific bioaccumulation of major and trace elements in arctic seabirds. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2006; 25:2927–2936.

- Bostan, N. , Ashrif, M., Mumtaz, A.S. and Ahmad, I., 2007. Diagnosis of heavy metal contamination in agro-ecology of Gujranwala, Pakistan using cattle egret as bioindicator. Ecotoxicology, 6, 247–251.

- Brown, R.E. , Brain, J.D. and Wang, N., 1997. The avian respiratory system: a unique model for studies of respiratory toxicosis and for monitoring air quality. Environmental Health Perspectives, 105, 188–200.

- Burger, J. (1993). Metals in avian feathers: bioindicators of environmental pollution. Reviews in Environmental Toxicology, 5, 203–311.

- Burger, J. , Bowman, R., Glen, E. and Gochfeld, W.M., 2004. Metal and metalloid concentrations in the eggs of threatened Florida scrub-jays in suburban habitat from south-central Florida. Sci. Total Environ, 328, 185–193.

- Burger, J. and Gochfeld, M., 2007. Metals and radionuclide in birds and eggs from Amchitka and Kiska Islands in the Bering Sea/Pacific Ocean ecosystem. Environ. Monit. Assess. 127, 105–117.

- Burger, J. , & Gochfeld, M. 2009. Comparison of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, manganese, mercury and selenium in feathers in bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), and comparison with common eider (Somateria mollissima), glaucous-winged gull (Larus glaucescens), pigeon guillemot (Cepphus columba), and tufted puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) from the Aleutian Chain of Alaska. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 152, 357–367.

- Burgess, N.M. and Hobson, K.A. 2006. Bioaccumulation of mercury in yellow perch (Perca flavescens) and common loons (Gavia immer) in relation to lake chemistry in Atlantic Canada. Hydrobiologia, 567, 275–282.

- Cabaraux, J.F. , Dotreppe, O.. Hornick, J.L., Istasse, L. and Dufrasne, I. 2007. Les oligo-éléments dans l’alimentation des ruminants: État des lieux, formes et efficacité des apports avec une attention particulière pour le sélénium, 2007. CRA-W-Fourrages Actualités, 12ème journée, 2007; 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, R.M. , Pennings, S.C. and Richards, C.L. 2003. Phenotypic plasticity and interactions among plants. Ecology 84:1115–1128.

- Christensen, T. H. , Kjeidsen, P., Bjerg, P. L., Jensen, D. L., Christensen, J. B., Baun, A., Albrechtsen, H. and Heron, G. 2001. Biogeochemistry of landfill leachate plumes. Appl. Geochem., 16, 659–718.

- Clarke, G. M. 1995. Relationships between developmental stability and fitness: application for conservation biology. Conserv. Biol. 9, 18-24.

- Clarkson, C.E. , Erwin, R.M. and Riscassi, A. 2012. The use of novel biomarkers to determine dietary mercury accumulation in nestling waterbirds. Environ Toxicol Chem 31:1143–1148.

- Cuadra, SN. , Linderholm, L., Athanasiadou, M. and Jakobson, K. 2006. Persistent organochlorine pollutants in children working at a waste-disposal site and in young females with high fish consumption in Managua, Nicaragu. Ambio 35 (3): 109–116.

- Cuervo, A. and Restrepo, C. 2007. Assemblage and population-level consequences of forest fragmentation on bilateral asymmetry in tropical montane birds. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 92: 119–133.

- Dauwe, T. , Bervoets, L., Pinxten, R., Blust, R., & Eens, M. 2006. Variation of heavy metals within and among feathers of birds of prey: effects of molt and external contamination. Environmental Pollution, 124, 429–436.

- Debat, V. and David, P. 2001. Mapping phenotypes: canalization, plasticity and developmental stability. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16: 555–561.

- De Leon, S,, Halitschkem R,, Hames, R.S., Kessler, A., De Voogd, T.J. and Dhondt, A.A. 2013. The Effect of Polychlorinated Biphenyls on the Song of Two Passerine Species. PLoS ONE, 8.

- de Lapuente, J. , González-Linares, J., Pique, E. and Borràs, M., 2014. Ecotoxicological impact of MSW landfills: assessment of teratogenic effects by means of an adapted FETAX assay. Ecotoxicology, 23, 102–106.

- Desrochers, R. E. and Anand, M. 2003. The use of taxonomic diversity indices in the assessment of perturbed community recovery. Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, vol 63. ISSN 1743-3541.

- Djerdali, S. , Guerrero-Casado, J., Tortosa, F.S., 2016. Food from dumps increases the reproductive value of last laid eggs in the White Stork Ciconia ciconia. Bird Study, 1-8.

- Duda-Chodak A and Blaszczyk U (2008). Impact of nickel to public health. J Elem, 13, 685–696.

- Eagles-Smith, C.A. , Wiener, J.G., Eckley, C.S., Willacker, J.J., Evers, D.C., Marvin-Di Pasquale, M, Obrist, D., Fleck, J.A,, Aiken, G.R., Lepak, J.M., Jackson, A.K., Webster, J.P., Stewart, A.R., Davis, J.A., Alpers, C.N. and Ackerman, T. 2016. Mercury in western North America: a synthesis of environmental contamination, fluxes, bioaccumulation, and risk to fish and wildlife. Sci Tot Environ 568, 1213–1226.

- Edegbene, A.O. 2018. Invasive grass (Typha domingensis): A potential menace on the assemblage and abundance of migratory/water related birds in Hadeija-Nguru Wetlands, Yobe State, Nigeria. Trop. Fresh. Biol., 27(2):, 13–20.

- Eeva, T. , Lehikoinen, E., and Ronka, M. (1998). Air pollution fades the plumage of theGreat Tit. Functional Ecology, 12, 607–612.

- Eeva, T. , Lehikoinen, E. and Nikinmaa, M. 2003. Pollution-induced nutritional stress in birds: an experimental study of direct and indirect effects. Ecol Appl 13:1242–1249.

- Evers, D.C. , Savoy, L.J., DeSorbo, C.R., Yates, D.E., Hanson, W., Taylor, K.M., Siegel, L.S., Cooley Jr, J.H., Bank, M.S. and Major, A. et al. 2008. Adverse effects from environmental mercury loads on breeding common loons. Ecotoxicology (2008) 17: 69-81.

- Eggen, T. , Moeder, M. and Arukwe, A., 2010. Municipal landfill leachates: A significant source for new and emerging pollutants. Science of the Total Environment, 408, 5147–5157.

- Eludoyin, A.O. and Oyeku, O.T. 2010. Heavy metal contamination of groundwater resources in a Nigerian urban settlement. Afri. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 4, 201–214.

- Enumeku, A.A. , Ezemonye, L.I. and Ainerua, M.O. 2014. Human health risk assessment of metal contain nation through consumption of Sesarma angolense and Macrobrachuim macrobrachuim from Benin river, Nigeria. European International Journal of Science and Technology, 3(4):.

- Erwin, M. and Custer, T.W., 2000. Herons as indicators. In: Kushlan, J.A., Hanfer, H. (Eds.), Heron Conservation. Academic Press, 310–330.

- Eulaers, I. , Covaci, A., Herzke, D., Eens, M., Sonne, C., Moum, T., Schnug, L., Hanssen, S.A., Johnsen, T.V., Bustnes, J.O. and Jaspers, V.L.B. 2011. A first evaluation of the usefulness of feathers of nestling predatory birds for non-destructive biomonitoring of persistent organic pollutants, Environ. Int. 37 (2011) 622-630.

- European Union, 1999. Council Directive 1999/31/EC of on the landfill of waste.

- Fairbrother, A. , Wenstel, R., Sappington, K. and Wood, W. Framework for metals risk assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2007; 68, 145–227. [Google Scholar]

- Fasola, M. , Movalli, P. and Gandini, C., 1998. Heavy metal, organochlorine pesticide, and PCB residues in eggs and feathers of herons breeding in northern Italy. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 34, 87–93.

- Fernie, K.J. , Chabot, D., Champoux, L., Brimble, S., Alaee, M., Marteinson, S., Chen, D., Palace, V., Bird, D.M. and Letcher, R.J. 2017. Spatiotemporal patterns and relationships among the diet, biochemistry, and exposure to flame retardants in an apex avian predator, the peregrine falcon. Environmental Research, 158, 43–53.

- Furness, R.W. 1993. Birds as monitors of pollutants. In: Furness RW, Greenwood JJD (eds) Birds as monitors of the environmental change. Chapman and Hall, London, 86–86.

- Furness, R.W. 1996; cadmium in birds. In: Beyer WN, Heinz GH, Redmon-Norword Aw (eds) Environmental contamination in Wldlife: interpreting tissue Concentrations CRC Press, Boca Raton, p 389.

- Garcia-Fernandez, A.J. , Espin, S., Martinez-Lopez, E. 2013. Feathers as a Biomonitoring Tool of Polyhalogenated Compounds: A Review. Environmental Science & Technology 47, 3028-3043.

- Giesy, J.P. , Feyk, L.A., Jones, P.D., Kannan, K., Sanderson, T., 2003. Review of the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in birds, Pure and Applied Chemistry, p. 2287.

- Gilbert, N.I. , Correia, R.A., Silva, J.P., Pacheco, C., Catry, I., Atkinson, P.W., Gill, J.A. and Franco, A.M. 2016. Are white storks addicted to junk food? Impacts of landfill use on the movement and behaviour of resident white storks (Ciconia ciconia) from a partially migratory population. Movement Ecology, 4, 7.

- Gruz, A. , Déri, J., Szemerédy, G., Szabó, K., Kormos, E., Bartha, A., Lehel, J. and Budai, P. 2018. Monitoring of heavy metal burden in wild birds at eastern/north-eastern part of Hungary. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 6378. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, R. , Eckhardt, S., Breivik, K., Jaward, F., Prieto, A., and Nizzetto, L. et al. 2011. Evidence for major emissions of PCBs in the West African Region. Environ Sci Technol, 2011; 45, 1349–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, F. , Fawell, J. and Bartram J 2010. Too much or too little? A review of the conundrum of selenium. Journal of Water and Health, 8, 405–416.

- Gragnaniello, S. , Fulgione, D., Milone, M., Soppelsa, O., Cacace, P. and Perrara, L. 2001. Sparrows as possible heavy metal biomonitors of polluted environments. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 66, 719–726.

- Guigueno, M.F. and Fernie, K.J., 2017. Birds and flame retardants: A review of the toxic effects on birds of historical and novel flame retardants. Environmental Research, 154, 398–424.

- Gushit, J.S. , Turshak, L.G., Chaskda, A.A., Abba, B.R. and Nwaeze, U.P. 2016. Avian feathers as bioindicator of heavy metal pollution in urban degraded woodland. Ew J Anal & Environ Chem, 2, 84–84.

- Hambly., C, Harper, E.J. and Speakman. J.R. 2004. The energetic cost of variations in wing span and wing asymmetry in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttate). J Exp Biol 207:3977–3984.

- Hamme, A.O. , Lukuman, A., Gbola, K.A., Mohammed, O.A. 2017. Heavy metal contents in soil and plants at dumpsites: A case study of Awotan and Ajakanga dumpsite Ibadan, Oyo State. Nigeria. J. Environ. Earth Sci, 11–24.

- Hallanger, I.G. , Warner, N.A., Ruus, A., Evenste, A., Christensen, G. and Herzke, D. et al. 2011. Seasonality in contaminant accumulation in Arctic marine pelagic food webs using trophic magnification factor as a measure of bioaccumulation. Environ Toxicol Chem, 2011; 30, 1026–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, M.Z. , Malik, R.N. and Shahbaz, M., 2013. Heavy metals in eggshells of cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis) and little egret (Egretta garzetta) from the Punjab province, Pakistan. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 89, 158–165.

- Hollamby, S. , Afema-Azikuru, J., Waigo, S., Cameron, K., Rae-Gandolf, A. and Norris, A. 2006. Suggested guidelines for use of avian species as biomonitors, Enviromental Monitoring and Assessment, 13-20.

- Hoornweg, D. , 2013. Waste production must peak this century. Nature 502, 615 - 617.

- Igbo, J.K. , Chukwu, L.O. and Oyewo, E.O. 2018. Assessment of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) in Water, Sediments and Biota from Ewaste Dumpsites in Lagos and Osun States, South-West, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. Vol. 22 (4) 459 – 464 April 2018.

- Igwe, J.C. , Nwokennaya E.C. and Abia, A. 2005. The role of pHin heavy metal detoxification by bio-sorptionfrom aqueous solutions containing chelating agents. 1: African Journal of Biotechnology 4(10); 1109–1112.

- Ikem, A. , Osibanjo, O., Sridhar, M. K. C. and Sobande, A. 2002. Evaluation of groundwater quality characteristics near two waste sites in Ibadan and Lagos, Nigeria. Water- Air-Soil Pollut., 140, 307–333.

- Ishmael, A.A. and Dorgham, M.M. 2002. Ecological indices as a toll for assessing pollution in El-Dekhaila harbor (Alexandria, Egypt). Oceanologia, 45, 121–131.

- Jaishankar, M. , Mathew, B.B., Shah, M.S., Murthy, K.T.P., Gowda, K.R.S. 2014. Biosorption of few heavy metal ions using agricultural wastes. J. Environ. Pollut. Hum. Health 2014, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jaksic, F.M. 2001. The conservation status of raptors in the metropolitan region, Chile. Journal of Raptor Research, 35, 151–158.

- Jan, A.T. , Ali, A. and Haq, Q.M.R. 2011. Glutathione as an Antioxidant in Inorganic Mercury Induced Nephrotoxicity. J. Postgrad. Med. 2011, 57, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, A.T. , Azam, M., Siddiqui, K., Ali, A., Choi, I. and Haq, Q.M.R. 2015. Heavy metals and human health: Mechanistic insight into toxicity and counter defense system of antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015; 16, 29592–29630. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.C. and Townsend, T.G. 2011. Leaching of lead from computer printed wire boards and cathode ray tubes by municipal solid waste landfill leachates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 4778–84.

- Jaspers, V. , Dauwe, T., Pinxten, R., Bervoets, L., Blust, R. and Eens, M. 2004. The importance of exogenous Contamination on heavy metal level in bird feathers. A field experiment with free-living great tits, Parus major Journal of Environmental Monitoring 6:356-360.

- Jaspers, V.L.B. , Voorspoels, S., Covaci, A., Lepoint, G. and Eens, M. 2007a. Evaluation of the usefulness of bird Feathers as a non-destructive biomonitoring tool for organic pollutants- a comparative and meta-analytical approach. Environ int APR; 33, 328–337.

- Jaspers, V.L.B. , Covaci, A., Deleu, P. and Eens, M. 2009. Concentrations in bird feathers reflect regional contamination with organic pollutants, Sci. Total Environ. 407 (2009) 1447-1451.

- Jaspers, V.L.B. , Rodriguez, F.S., Boertmann, D., Sonne, C., Dietz, R., Rasmussen, L.M., Eens, M. and Covaci, A. 2011. Body feathers as a potential new biomonitoring tool in raptors: a study on organohalogenated contaminants in different feather types and preen oil of West Greenland white-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla). Environ. Int. 2011; 37, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Janaydeh, M. , Ismail, A., & Zulkifli, S.Z., Bejo, M.H., Abd. Aziz, N.A. and Taneenah, A. 2016. The use of feather as an indicator for heavy metal contamination in house crow (Corvus splendens) in the Klang area, Selangor, Malaysia. Environ Sci Pollut Res (2016) 23: 22059–22071.

- Kalisinska, E. , Salicki, W., Myslek, P., Kavetska, K.M. and Jackowski, A., 2003. Using the mallard to biomonitor heavy metal contamination of wetlands in northwestern Poland. Sci. Total Environ. 320, 145–161.

- Karri, V. , Schuhmacher, M. and Kumar, V. 2016. Heavy metals (Pb, Cd, As and MeHg) as risk factors for cognitive dysfunction: A general review of metal mixture mechanism in brain. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 48, 203–213.

- Kasprzak, K.S. , Sunderman Jr, F.W. and Salnikow, K. 2003. Nickel carcinogenesis. Mutat Res, 533, 67–97.

- Khan, S.A. 2016. Tools for environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) using diversity indices. Ving Journal of Science, (2016) vol 12, No 1& 2.

- Keller, R.H. , Xie L., Buchwalter D.B., Franzreb K.E. and Simons T.R. 2013. Mercury bioaccumulation in Southern Appalachian birds, assessed through feather concentrations. Ecotoxicology, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, A. , Heysab, R.F., Shoreb, M., Pereirab, G., Kevin, C., Jonesa and Martin, F.L. Risk assessment of environmental mixture effects. Royal Society of Chemistry Advances 2016, 6, 47844. [Google Scholar]

- Knierim, U. , Van Dongen, S., Forkman, B., Tuyttens, F.A.M., Špinka, M., Campo, J.L., Weissengruber, G.E., 2007. Fluctuating asymmetry as an animal welfare indicator: a review of methodology and validity. Physiol. Behav. 92 (3), 398–421.

- Lauby-Secretan, B; et al. 2016. “Body Fatness and Cancer — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group,” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 375, (8), pp. 794-798p. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, G.a. and Bain, L.J. 1997. Chronic toxicity of environmental contaminants: Sentinels and biomarkers. Environmental Health Perspectives, 105, 65–80.

- Lens, L. , Van Dongen, S., Kark, S. & Matthysen, E. 2002. Fluctuating asymmetry as an indicator of fitness: can we bridge the gap between studies? Biol. Rev. 77: 27–38.

- Leung, B. , Knopper, L. & Mineau, P. 2003. A critical assessment of the utility of fluctuating asymmetry as a biomarker of anthropogenic stress. In Polak, M. (ed.) Developmental Instability. Causes and Consequences. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Lindsey, P. , Allan J., Brehony, P., Dickman, A., Robson, A., Begg, C, Bhammar, H., Blanken, L., Breur, T., Fitzgerald, K., Flyman, M., Gandiwa, P., Giva Nicia, Kado, D., Nampinda, S., Nyambe, N., Steiner, K., Parker, A., Roe, D., Thomson, P., Monble, M., Caron, A. and Tyrell, P. 20. Conserving Africa’s Wildlife and wildlans through the COVID—19 crisis and beyond. Nature, Ecology and Evolution., vol 4 1300-1310.

- Llacuna, S. , Gorriz, A., Sanpera, C., & Nadal, J. (1995). Metal accumulation in three species of passerine birds (Emberiza cia, Parus major and Turdus merula) subjected to air pollution from a coal-fired power plant. Archives Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 28, 298–303.

- Ma, Y. , Perez, C.R., Branfireun, B.A., Guglielmo, C.G. 2018a. Dietary exposure to methylmercury affects flight endurance in a migratory songbird. Environ Pollut 234:894–901.

- Ma, Y. , Branfireun, B.A., Hobson, K.A., Guglielmo, C.G. 2018b. Evidence of negative seasonal carry-over effects of breeding ground mercury exposure on survival of migratory songbirds. J Avian Biol.

- MacDonald, R.W. , Barrie, L.A., Bidleman, T.F., Diamond, M.L., Gregor, D.J. and Semkin, R.G. et al. 2000. Contaminants in the Canadian Arctic: 5 years of progress in understanding sources, occurrence and pathways. Sci Total Environ 2000; 254:93–234.

- Malik, R.N. and Zeb, N. 2009. Assessment of environmental contamination using feathers of Bubulcus ibis L., as a biomonitor of heavy metal pollution, Pakistan. Ecotoxicology, 18, 522–536.

- Malik, R.N. , Moeckel, C., Jones, K.C. and Hughes, D. 2011. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in feathers of colonial water-bird species from Pakistan, Environ. Pollut. 159 (2011) 3044–3050.

- Manjula, M. , Mohanraj, R. and Devi, M.P. 2015. Biomonitoring of heavy metals in feathers of eleven common bird species in urban and rural environments of Tiruchirappalli, India. Environ Monit Assess, 2015; 187, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Marasinghee, S. Perera, P. and Dayawansa, N. 2018. Putrescible waste landfills as bird habitats in urban cities: A case from an urban landfill in the Colombo district of Sri Lanka. Journal of Tropical of Forestry and Environment Vol. 8.

- Martens, D.A. and Suarez, D. L. 1996. Selenium speciation of soil/sediment determined with sequential extractions and hydride generation atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996, 31, 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Finley, E.J. , Chakraborty, S., Fretham, S.J. and Aschner, M. 2012. Cellular transport and homeostasis of essential and nonessential metals. Metallomics, 2012; 4, 593–605. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López, E. , Espín, S., Barbar, F., Lambertucci, S.A., Gómez-Ramírez, P., García- Fernández, A. 2015. Contaminants in the southern tip of South America: Analysis of organochlorine compounds in feathers of avian scavengers from Argentinean Patagonia, Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015; 115, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Masoner, J.R. , et al. 2015. Landfill leachate as a mirror of today’s disposable society: Pharmeceuticals and other contaminants of emerging concern in final leachate from landfills in the conterminous United States. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 35, 906–18.

- Mazumdar, S. , Ghose, D., Saha, G.K., 2016. Foraging strategies of black kites (Milvus migrans govinda) in urban garbage dumps. Journal of Ethology, 34, 243–247.

- Mehdi, Y. , Hornick, J-L., Istasse, L. and Dufrasne, I. 2013. Selenium in the Environment, Metabolism and Involvement in Body Functions. Molecules, 3292. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, S.P. , Mehra, S., Uddin, M., Verma, V., Sharma, H., Singh, T., Kaur, G. Rimung, T. and Kumhar, H.R. 2017. Waste as a Resource for Avifauna: Review and Survey of the Avifaunal Composition in and around Waste Dumping Sites and Sewage Water Collection Sites (India). International Journal of Waste Resources 7, 1-8.

- Meschy, F. Nutrition minérale des ruminants; Editions Quae: Versaille, France, 2010; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, L.S. , Citta, J.J. and Lair, K.P. et al. 2000. Estimating animal abundance using noninvasive DNA sampling: promise and pitfalls. Ecol Appl, 10, 283–294.

- Møller, A.P. 1996. Development of fluctuating asymmetry in tail feathers of the barn swallow Hirundo rustica. J. Evol. Biol. 9:677–694.

- Møller, A.P. & Swaddle, J.P. 1997. Asymmetry, Developmental Stability and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Monclús, L. , Lopez-Bejar, M., De la Puente, J., Covaci, A. and Jaspers, V.L.B., 2018. First evaluation of the use of down feathers for monitoring persistent organic pollutants and organophosphate ester flame retardants: A pilot study using nestlings of the endangered cinereous vulture (Aegypius monachus). Environmental Pollution 238, 413-420.

- Morales, L. , Martrat, M.G., Olmos, J., Parera, J., Vicente, J., Bertolero, A., Ábalos, M., Lacorte, S., Santos, F.J. and Abad, E. 2012. Persistent Organic Pollutants in gull eggs of two species (Larus michahellis and Larus audouinii) from the Ebro delta Natural Park. Chemosphere, 88, 1306–1316.

- Muller L and Kasper P (2000) Human biological relevance and the use of threshold arguments in regulatory genotoxicity assessment: Experience with pharmaceuticals. Mutat Res 464:19-34.

- Muralidharan, S. , Jayakumar, R. and Vishnu, G. 2004. Heavy metals in feathers of six Species of birds in the district Nilgiris, India. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol, 73, 285–291.

- Murugan, S.S. , Karuppasamy, R., Poongodi, K. and Puvaneswari, S. 2008. Bioaccumulation pattern of zinc in freshwater fish Channa punctatus after chronic exposur. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquaculture Sciences, 8: 55.

- Nääs, I.A. , Baracho, M.S., Salgado, D.D., Sonoda, L., Carvalho, V.C., Moura, D.J., Paz, I.C.L.A. Broilers’ toes asymmetry and walking ability assessment. Engenharia Agrícola 2009; 29:538-546.

- Nagajyoti, P.C. , Lee, K.D., Sreekanth, T.V.M. 2010. Heavy metals, occurrence and toxicity for plants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2010, 8, 199–216.

- Ngole, V.M. and Ekosse, G.I.E. 2012. Copper, nickel and zinc contamination in soils within the precincts of mining and landfilling environments. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol 2012, 9, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, P.A. 2016. The Unnoticed Benefits of City Dumpsites. Indian Journal of Applied Research, 6, 113–119.

- Oro, D. , Genovart, M., Tavecchia, G., Fowler, M.S. and Martínez-Abraín, A., 2013. Ecological and evolutionary implications of food subsidies from humans. Ecology Letters, 16, 1501–1514.

- Oshode, O. A. 1, Bakare, A. A., Adeogun, A. O., Efuntoye, M. O. and Sowunmi, A.A. 2008. Ecotoxicological Assessment Using Clarias Gariepinus and Microbial Characterization of Leachate from Municipal Solid Waste Landfill. Int. J. Environ. Res., 2(4): 391-400, Autumn 2008.